Abstract

Objective

Unmet dental need in children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is common. We tested hypotheses that lacking a medical home or having characteristics of more severe ASD is positively associated with having unmet dental need among children with ASD.

Methods

Using data from the 2009–2010 National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs, we analyzed 2,772 children 5–17 years old with ASD. We theorized unmet dental need would be positively associated with not having a medical home and having characteristics of more severe ASD (e.g. parent reported severe ASD, an intellectual disability, communication or behavior difficulties). Prevalence of unmet dental need was estimated, and unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios (ORs), 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and p-values were computed using survey methods for logistic regression.

Results

Nationally, 15.1% of children with ASD had unmet dental need. Among children with ASD, those without a medical home were more apt to have unmet dental need than those with a medical home (adjusted OR 4.46, 95% CI: 2.59, 7.69). Children with ASD with intellectual disability or greater communication or behavioral difficulties had greater odds of unmet dental need than those with ASD without these characteristics. Parent reported ASD severity was not associated with unmet dental need.

Conclusions

Children with ASD without a medical home and with characteristics suggestive of increased ASD-related difficulties are more apt to have unmet dental need. Pediatricians may use these findings to aid in identifying children with ASD who may not receive all needed dental care.

Keywords: Autism, austim spectrum disorder, autistic disorder, dental, oral health, unmet need, medical home

INTRODUCTION

Dental care is the leading unmet health care need among children,1 and is particularly problematic for children with special health care needs (CSHCN).2 Nationally, over three quarters of a million CSHCN (10.4% of all CSHCN) are unable to obtain needed dental care each year.3 Comparatively, 6.6% of all American children have unmet dental needs.4 In addition to unmet need, CSHCN generally experience a higher prevalence of dental disease and greater difficulty accessing dental care compared to peers without special health care needs.4–6 Children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) make up a significant portion of the U.S. population of CSHCN. ASD affects between 1 in 50 and 1 in 88 American children, and over 700,000 U.S. children have ASD.7–9 Recent estimates suggest that approximately 12% of children with ASD have unmet dental care needs,10,11 National studies have examined predictors of unmet dental need in all CSHCN2,3,11, but none have examined predictors of unmet dental need in children with ASD.

Although a heterogeneous group, children with ASD typically have sensory and behavioral limitations that may affect their ability to obtain dental care in a manner which differs from other CSHCN. The dental appointment is among the most challenging types of healthcare children with ASD receive due to sensory inputs such as loud or unusual sounds, strange smells, bright lights, and having instruments in the mouth.12 Social and behavioral deficits may impair the ability of a child with ASD to cope with a dental visit.12–14 Regional studies of children with ASD have shown that children with behavioral difficulties have more unmet dental need compared to children with ASD who do not display behavioral issues,15,16 Financial barriers to dental care and lack of dental insurance coverage are also commonly cited reasons for unmet dental need in the ASD population.15–17 Yet the existing evidence regarding unmet dental need in children with ASD is inconclusive, largely due to methodological weaknesses that include: relatively small samples of children with ASD10,16,17, low response rates15,16, using a convenience sample,12,13 or combining ASD with other conditions (Down Syndrome, developmental delay).17

Pediatricians and other primary care providers (PCPs) play a key role in linking patients with ASD to other health care services, including dental care. Most studies in children with ASD suggest coordination and delivery of certain preventive and treatment services, including dental care, may be dependent on having a reliable PCP in an established medical home.11,18–20 Understanding factors that influence receipt of needed dental care may aid pediatricians in identifying high-risk patients and referring patients to dentists with the appropriate level of expertise.

We conducted a secondary analysis of a national population-based cross-sectional survey to estimate the prevalence of unmet dental needs in all CSHCN, in children with ASD, and to examine health care, behavioral, and condition-related variables associated with unmet dental need among children with ASD. Based on prior literature, we anticipated that children with ASD without a medical home, with a gap in insurance coverage, with impairments in cognitive function, communication, behavior, physical function, making or keeping friends, or the inability to attend school and organized activities would be more likely to have unmet dental need relative to ASD counterparts without these characteristics. The number of screener criteria for being a CSHCN may be an objective marker of the severity of special needs in children with ASD.2 Therefore, we postulated that those with greater parent reported ASD severity or with more screener criteria qualifying them as a CSHCN would be more likely than their ASD counterparts without these characteristics to have unmet dental need. Finally, parent reported barriers to dental care among children with ASD who reported unmet dental need were quantified.

METHODS

Survey

The NS-CSHCN is a national telephone survey administered by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Health Statistics, State and Local Area Integrated Telephone Survey program, which uses random digit dialing to identify households with children under 18 years old.21,22 We used the 2009 to 2010 National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs (NS-CSHCN). A parent or guardian with potentially eligible children answered a series of 5 screening questions to determine if a child in the household met the definition of a CSHCN.21 If 2 or more CSHCN were identified in a household, one was selected at random.23 The screening questions are derived from a validated screening tool,24 which operationalizes the definition of CSHCN as children ‘who have or are at increased risk for a chronic physical, developmental, behavioral, or emotional condition and who also require health and related services of a type or amount beyond that required by children generally.’25 Children must meet one of the 5 following criteria for at least 12 months to be classified as a CSHCN: 1) ‘currently needs or uses medicine prescribed by a doctor, other than vitamins’; 2) ‘uses more medical care, mental health or educational services than is usual for most children of the same age’; 3) ‘is limited or prevented in any way in his/her ability to do the things most children of the same age can do’; 4) ‘needs or gets special therapy such as physical, occupational, or speech therapy’; and 5) ‘has any kind of emotional, development or behavioral problem for which he/she needs treatment or counseling’.26

Of 372,698 children less than 18 years of age screened nationally, 40,242 CSHCN were identified and a parent then interviewed for the NS-CSHCN. The interview asked about the child’s health and functional status, access to care, care coordination, health insurance, adequacy of insurance coverage, and demographics.26 At least 750 interviews were conducted in each of the 50 states and the District of Columbia. The survey was administered in English, Spanish, Mandarin, Cantonese, Vietnamese and Korean.22

Study Population

We estimated the prevalence of unmet dental need among all 40,242 CSHCN. For all other analyses, we limited our sample to children 5 to 17 years old with a current diagnosis of ASD, as reported by a parent. The question used to identify ASD asked: ‘whether a doctor or other health care provider had ever told them the child had Autism, Asperger’s Disorder, pervasive development disorder, or other autism spectrum disorder,’ followed by a question about whether the child currently had one of these conditions. We excluded children less than 5 years old in this study because US children on average are not diagnosed with ASD before age 427, the majority of children have not seen a dentist until after age 528,29, and data on several predictors of interest were not collected on children under 5 in this survey. There were 2,772 children who met criteria for current ASD, were 5 through 17 years of age, and whose parent responded to the question of unmet dental care need. These children comprised our primary analytic sample.

Outcome Measure

Our outcome was any type of unmet dental need, which was based on the child not receiving the following during the past 12 months: 1) all of the preventive dental care needed; and/or 2) all other dental care needed. Those who reported receiving all needed dental care (preventive and other) were classified as not having unmet dental need.

Covariates

We extracted demographic covariates including child age and race/ethnicity, household poverty level, primary language in the home, and type of insurance and categorized these variables as presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics of children with ASD stratified by unmet dental need

| Dental Needs are Met (N = 2396) |

Has Unmet Dental Need (N = 376) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |

| Demographics | ||||

| Gender of the child | ||||

| Male | 1926 | 80.8 | 307 | 78.5 |

| Female | 467 | 19.2 | 69 | 21.5 |

| Age of the child (in years) | ||||

| 5–9 | 967 | 42.5 | 144 | 38.3 |

| 10–12 | 645 | 27.1 | 95 | 31.5 |

| 13–17 | 784 | 30.4 | 137 | 30.2 |

| Race and ethnicity of the child | ||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 1761 | 65.5 | 267 | 58.3 |

| Hispanic, any race | 246 | 14.1 | 45 | 16.4 |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 155 | 10.5 | 30 | 9.3 |

| Other, non-Hispanic | 234 | 9.9 | 34 | 15.9 |

| Household federal poverty level (FPL)1 | ||||

| ≤100% FPL | 310 | 17.4 | 76 | 22.2 |

| 101–200% FPL | 430 | 19.7 | 95 | 27.7 |

| 201–400% FPL | 727 | 32.5 | 112 | 35.6 |

| >400% FPL | 717 | 30.4 | 59 | 14.5 |

| Primary language in home | ||||

| English | 2317 | 94.7 | 358 | 95.4 |

| Other | 58 | 5.3 | 15 | 4.6 |

| Insurance type | ||||

| Private | 1254 | 47.2 | 150 | 41.1 |

| Public | 631 | 31.0 | 128 | 39.4 |

| Private and public | 386 | 19.5 | 54 | 12.7 |

| Uninsured | 48 | 2.3 | 29 | 6.8 |

NOTE: All percentages are sample weighted estimates. Counts are raw counts not adjusted for sampling weights. All variables missing <5% unless otherwise noted.

Missing data 9%

We examined health care and condition-related factors as potential predictors of unmet dental need, including having a medical home or gap in insurance coverage in the past 12 months, parent reported ASD severity, number of screener criteria met for being a CSHCN, having co-morbid conditions including intellectual disability, anxiety, or attention deficit disorder/attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADD/ADHD), and receipt of services from a special education program defined as ‘any kind of special school, class, or tutoring’.30 Having a medical home was based on an established methodology with responses to 21 survey items corresponding to 5 medical home domains: 1) a relationship with a specific care provider; and whether the care was: 2) family-centered 3) comprehensive; 4) coordinated; and 5) culturally effective.31,32 The 2009–2010 NS-CSHCN uses the same methods to define medical home as the 2005–2006 NS-CSHCN, which is explained in detail elsewhere.31 Severity of the child’s ASD (mild, moderate, severe) was based on the parent’s perception and self-report. Because number of positive CSHCN screener criteria is associated with greater unmet dental need2, we examined number of positive screener criteria as a measure of severity of special needs in children with ASD. Screener criteria score ranged from 1 up to 5 based on the criteria described in the Survey section above.

We also examined behavior and activity related factors. A series of questions compared the parental perception of difficulty a child had compared to his or her same aged peers with regard to communication (e.g. understanding, paying attention, speaking, being understood), behavior (e.g. feeling anxious, depressed, acting out, arguing), physical function (e.g. eating, dressing, bathing, coordination), and making and keeping friends (no more difficulty, a little more, or a lot more). Ability to attend school and participate in organized activities was measured by asking if the child’s ASD interfered with 1) the ‘ability to attend school on a regular basis’ and/or 2) the ‘ability to participate in sports, clubs or other organized activities’. The child was categorized as having neither, one, or both of these abilities affected.

Statistical analysis

We estimated the prevalence of unmet dental need among all CSHCN and children with ASD, and for those 5 to 17 years old. Descriptive statistics (counts and percentages) were calculated for all variables of interest stratified on unmet dental need. Raw counts are presented to inform on the number of observations in various strata. Unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression models were used to estimate odds ratios, 95% confidence intervals, and p-values to determine associations between predictors of interest and unmet dental need. We made an a priori decision to adjust for all demographic variables listed in Table 1 in our logistic models based on the theoretical basis that each of these could be confounders associated with unmet dental need and our predictors of interest. Sampling weights were used to account for probability sampling and to generate accurate standard errors in all analyses using the survey commands in Stata 12.0 (College Station, TX). Because we analyzed a de-identified public use dataset, this research was deemed exempt from human subjects review by the University of Washington IRB.

RESULTS

The prevalence of unmet dental need among all CSHCN and CSHCN 5 to 17 years old was 12.0% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 11.4%, 12.7%) and 12.9% (95% CI: 12.2%, 13.6%), respectively. The prevalence of unmet dental need among all children with ASD and those 5 to 17 years of age was 15.1% (95% CI 12.5%, 18.2) and 15.1% (95% CI: 12.3%, 18.4%), respectively. Those with unmet dental need were similar to those with no unmet dental need with regard to the child’s gender and age and the primary language spoken in the home. Consistent with reports that ASD is more than 4 times as common in boys, approximately 80% of our sample was male.8 A disproportionate amount of those with unmet dental need were below or near the federal poverty level (<200%), on public insurance, or uninsured (Table 1).

The strongest predictor of unmet dental need was not having a medical home (Adjusted OR [aOR] 4.46, 95% CI 2.59, 7.69) (Table 2). Having a gap in insurance coverage was positively associated with unmet need in unadjusted analysis but after adjustment analysis, this estimate lacked statistical significance (aOR 1.66, 95% CI 0.81, 3.41). Contrary to the proposed hypothesis, parent reported ASD severity was not associated with having unmet dental need, but a greater number of positive CSHCN screener criteria was associated with an increased odds of unmet dental need in both unadjusted and adjusted analyses (p=0.02 and 0.003, respectively). Intellectual disability was the only comorbid cognitive condition positively associated with unmet dental need (aOR 2.61, 95% CI: 1.60, 4.24). Anxiety, ADD/ADHD, and special education services were not associated with unmet dental need (Table 2).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics on healthcare and condition related risk factors, and unadjusted and adjusted associations for any unmet dental need in children with Autism Spectrum Disorder

| Dental Needs are Met |

Has Unmet Dental Need |

Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | OR | (95% CI) | p-value | OR | (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Child received coordinated, ongoing, comprehensive care within a medical home? | ||||||||||

| No | 1649 | 72.5 | 317 | 92.0 | 4.36 | (2.63 – 7.23) | <0.001 | 4.46 | (2.59 – 7.69) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 674 | 27.5 | 42 | 8.0 | ref | ref | ||||

| Has gaps in insurance in past year? | ||||||||||

| No | 2250 | 92.9 | 315 | 85.7 | ref | <0.001 | ref | 0.17 | ||

| Yes | 140 | 7.1 | 61 | 14.3 | 2.19 | (1.31 – 3.65) | 1.66 | (0.81 – 3.41) | ||

| Autism severity by parent report | ||||||||||

| Mild | 1278 | 49.5 | 145 | 45.7 | ref | 0.82 | ref | 0.92 | ||

| Moderate | 831 | 35.2 | 164 | 38.4 | 1.18 | (0.71 – 1.98) | 1.11 | (0.62 – 1.99) | ||

| Severe | 272 | 15.3 | 65 | 15.8 | 1.12 | (0.61 – 2.06) | 1.12 | (0.58 – 2.15) | ||

| Number of screener criteria met for being a CSHCN | ||||||||||

| 1 | 145 | 7.0 | 17 | 6.4 | ref | 0.02 | ref | 0.003 | ||

| 2 | 325 | 13.2 | 35 | 7.3 | 0.60 | (0.21 – 1.72) | 0.59 | (0.18 – 1.96) | ||

| 3 | 500 | 20.4 | 54 | 11.5 | 0.61 | (0.24 – 1.54) | 0.59 | (0.20 – 1.76) | ||

| 4 | 793 | 32.4 | 142 | 37.0 | 1.24 | (0.52 – 2.96) | 1.25 | (0.44 – 3.55) | ||

| 5 | 633 | 27.0 | 128 | 37.7 | 1.51 | (0.58 – 3.95) | 1.80 | (0.61 – 5.25) | ||

| Has current Intellectual Disability? | ||||||||||

| No | 1910 | 78.4 | 274 | 61.8 | ref | <0.001 | ref | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 486 | 21.6 | 102 | 38.3 | 2.24 | (1.28 – 3.93) | 2.61 | (1.60 – 4.24) | ||

| Has current Anxiety? | ||||||||||

| No | 1371 | 56.8 | 171 | 51.1 | ref | 0.33 | ref | 0.22 | ||

| Yes | 1025 | 43.2 | 205 | 48.9 | 1.26 | (0.79 – 2.00) | 1.32 | (0.84 – 2.07) | ||

| Has current ADD/ADHD? | ||||||||||

| No | 1366 | 56.0 | 212 | 47.6 | ref | 0.15 | ref | 0.10 | ||

| Yes | 1030 | 44.1 | 164 | 52.4 | 1.40 | (0.89 – 2.21) | 1.41 | (0.94 – 2.12) | ||

| Child receives special educational services? | ||||||||||

| No | 447 | 18.7 | 67 | 19.3 | ref | 0.87 | ref | 0.94 | ||

| Yes | 1939 | 81.3 | 308 | 80.7 | 0.96 | (0.58 – 1.59) | 1.02 | (0.59 – 1.78) | ||

NOTE: All percentages are sample weighted estimates. Counts are raw counts not adjusted for sampling weights. All variables missing <5%. All adjusted models accounted for the child's gender, age, race/ethnicity, poverty level, primary language spoken in the home, and type of insurance. Ref=Reference.

Based on the parent’s perception, children with ASD with more behavioral difficulties had an increased odds of unmet dental need compared to those with ASD who had behavior similar to same aged peers (aOR 3.35, 95% CI 1.69, 6.67) (Table 3). In adjusted analyses, children with ASD and more communication (or physical function) difficulties were also more apt to have unmet dental need compared to others with ASD whose communication (or physical function) was similar to children their age (p=0.05). Children whose ASD interfered with their ability to attend school and organized activities were at greater odds of unmet dental need compared to those whose ASD did not interfere with these activities (aOR 4.36, 95% CI 2.16, 8.78) (Table 3). Making or keeping friends was not associated with unmet dental need.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics on behavioral and activity related risk factors, and unadjusted and adjusted associations for any unmet dental need in children with Autism Spectrum Disorder

| Dental Needs are Met |

Has Unmet Dental Need |

Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | OR | (95% CI) | p-value | OR | (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Communication difficulties | ||||||||||

| None | 72 | 3.4 | 7 | 1.9 | ref | 0.09 | ref | 0.05 | ||

| A little | 693 | 26.7 | 74 | 18.9 | 1.24 | (0.46 – 3.38) | 1.94 | (0.60 – 6.26) | ||

| A lot | 1631 | 69.9 | 294 | 79.2 | 2.00 | (0.78 – 5.13) | 3.05 | (0.98 – 9.44) | ||

| Behavioral difficulties | ||||||||||

| None | 273 | 13.1 | 25 | 5.8 | ref | 0.001 | ref | <0.001 | ||

| A little | 955 | 35.8 | 110 | 26.4 | 1.67 | (0.91 – 3.06) | 1.81 | (0.90 – 3.62) | ||

| A lot | 1168 | 51.1 | 241 | 67.8 | 3.00 | (1.59 – 5.64) | 3.35 | (1.69 – 6.67) | ||

| Physical function difficulties | ||||||||||

| None | 969 | 41.4 | 139 | 33.3 | ref | 0.24 | ref | 0.05 | ||

| A little | 1047 | 40.2 | 154 | 39.7 | 1.23 | (0.82 – 1.84) | 1.36 | (0.87 – 2.12) | ||

| A lot | 380 | 18.4 | 83 | 27.1 | 1.83 | (0.87 – 3.82) | 2.03 | (1.14 – 3.65) | ||

| Difficulty making and keeping friends | ||||||||||

| None | 390 | 18.8 | 45 | 14.1 | ref | 0.52 | ref | 0.51 | ||

| A little | 766 | 30.8 | 103 | 33.0 | 1.42 | (0.65 – 3.12) | 1.46 | (0.71 – 3.00) | ||

| A lot | 1232 | 50.4 | 225 | 52.9 | 1.40 | (0.78 – 2.51) | 1.42 | (0.77 – 2.61) | ||

| ASD interfered with school or organized activities | ||||||||||

| No interference | 823 | 34.6 | 67 | 14.8 | ref | <0.001 | ref | <0.001 | ||

| Interfered with ability to attend school | 58 | 2.9 | 13 | 2.6 | 2.09 | (0.81 – 5.43) | 2.88 | (1.04 – 7.97) | ||

| Interfered with participation in organized activities | 1136 | 45.1 | 191 | 50.2 | 2.61 | (1.63 – 4.18) | 3.14 | (1.87 – 5.30) | ||

| Interfered with school and organized activities | 362 | 17.4 | 102 | 32.4 | 4.38 | (2.16 – 8.87) | 4.36 | (2.16 – 8.78) | ||

NOTE: All percentages are sample weighted estimates. Counts are raw counts not adjusted for sampling weights. All variables missing <5%. All adjusted models accounted for the child's gender, age, race/ethnicity, poverty level, primary language spoken in the home, and type of insurance. Ref=Reference.

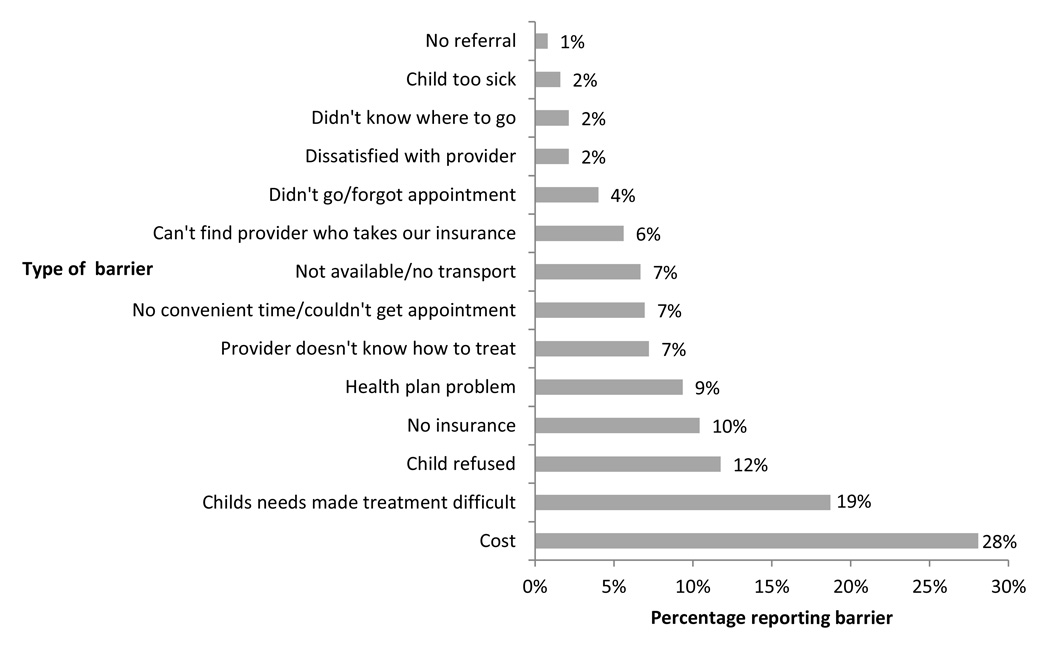

Among children with ASD who had unmet dental need, the top parent reported barriers to dental care were related to cost, the condition or behavioral characteristics of the child, insurance issues and difficulty finding a dental provider (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Barriers to receiving all needed dental care among children 5 years of age or older with ASD who reported any unmet dental need

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to estimate the prevalence of unmet dental need and identify factors associated with unmet dental need in a national sample of children with ASD. We found that those who did not have a medical home, met a greater number of screening criteria for being a CSHCN, have an intellectual disability, or have more difficulty with communication, behavior, physical function, attending school, or participating in organized activities, were more likely to Page 11 have unmet dental need than their ASD counterparts without these characteristics. Contrary to our hypothesis, parental report of ASD severity was not associated with unmet dental need.

Consistent with other findings, our data suggest that a greater proportion of children with ASD have unmet dental need compared to all CSHCN.11 The prevalence of unmet dental need in all CSHCN increased from 10.4% to 12% between 2001 and 2010 and for children with ASD increased from 12% to 15.1% between 2003 and 2010.3,10,11 These figures suggest unmet dental needs may be rising.

Children with ASD who did not have a medical home had a 4-fold increase in unmet dental need. Our findings are consistent with those from C. Lewis, Strickland, et al, and others who found that among all CSHCN, those without a regular doctor or nurse or a lacking a medical home were also more likely to have unmet dental care need.3,11,18 This evidence underscores the importance of ensuring that children with ASD and all CSHCN have a medical home. The strength of our association suggests a medical home may be particularly relevant for children with ASD. It also highlights the important role a pediatrician or other PCP can have in promoting oral health and access to dental care. Although many young children have not have seen a dentist, most see physicians and other non-dental healthcare providers on a regular basis. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD) now recommend that a child’s dental home is established by age one.33,34 Not only do pediatricians play a role in referral, they may also decrease unmet dental need by providing basic oral health services such as screenings, examinations and fluoride varnish.35–37 Currently, over 40 states and Page 12 the District of Columbia have Medicaid programs that reimburse medical providers for these types of preventive dental care.37

We are the first to report that among children with ASD, those with an intellectual disability are more apt to have difficulty obtaining needed dental treatment. This finding is consistent with other reports that children with ASD and comorbidities such as a speech and language disorder have more unmet dental need.14 Seemingly contradictory, our results suggest receiving special education services did not increase the risk of unmet need. Based on post-hoc analysis using our study sample described in the Methods, we found the composition of these groups is very different, with 80.8% of children with ASD receiving special education services, but less than a quarter (24.1%) having an intellectual disability. Our findings that those with more behavior or communication difficulties are predisposed to having unmet dental need are consistent with other reports that suggest these difficulties impede dental treatment in children with ASD.13,15,16

For CSHCN, severity of a child’s health condition is a recognized barrier to accessing health care services.2,17,38 However, parent reported severity of ASD was not associated with unmet dental need in our analysis. This finding is consistent with another study that found parent report of ASD severity was not associated with unmet dental need.15 In contrast, children with ASD who had a greater number of screening criteria for being a CSHCN had higher odds of unmet dental need. It may be that the subjective nature of parent reported ASD severity does not reliably capture factors that predispose a child to unmet dental need. Screening questions and other measures (e.g. behavioral, communication, physical function, school, organized activities) may be markers for children with ASD who may have a severe form of ASD or other conditions Page 13 representing greater special needs. Consistent with our findings on having a medical home, a greater number of screening criteria for being a CSHCN is related to unmet dental need both in children with ASD and all CSHCN.2 Predictors of unmet dental need may be similar for children with ASD and all CSHCN. Socioeconomic factors such as poverty are unlikely to explain our findings since we adjusted for them in our multivariable models.

These findings have clinical relevance for pediatricians and other PCPs and dentists. When assessing a child, clinicians can consider whether the child has predictors of unmet need identified here and use this information to tailor dental care to meet the unique and specific needs of the child. For example, we found having a greater number of CSHCN screener criteria was predictive of unmet dental need. It may be helpful to take into account whether the child takes prescription medications, participates in physical or occupational therapy, receives counseling, or uses more medical care than similar aged peers. Children with intellectual disability may also not receive dental treatment because of difficulty tolerating the varied and intense sensory inputs related to receiving dental care. When inquiring about linkages to dental care, it may be helpful to discuss these factors with families when determining the type of dental provider best suited for the child.

PCPs are often the nexus that connects patients with dental providers. Those who have an interest in caring for children with ASD should seek out like-minded dental providers and establish strong relationships to help ensure dental needs of these patients are adequately met. The skill set and equipment needed to provide dental treatment for children with ASD may vary according to that age of the child and severity of his or her disorder. This factor can be jointly Page 14 considered by dentist and PCP. Some university-based pediatric dentistry practices, for example, offer care for complex patients that may include behavior guidance with intense pre-visit preparation, special accommodations such as quiet privacy rooms, and access to specialized services such as sedation and general anesthesia.39 On the other hand, children with fewer predictors for unmet dental need may do well being treated by private practice and community-based dentists.

This study was limited due to the nature of the cross-sectional survey. It did not ask parents directly whether or not their child would have or has had difficulty tolerating dental care. We were not able to assess utilization of services, a more objective measure of experience than parental self-report. We were also unable to analyze by type of ASD (autism, Asperger syndrome, PDD-NOS) because this data was not available in the survey. While this could conceivably have provided more descriptive information about our population, it may not have added a great deal of insight about unmet dental need. Lai et al. looked at type of ASD using a large survey and did not detect any differences in having unmet dental needs by type of ASD.15 It may be that the behavioral characteristics of a child with ASD are more important than the label applied to the child when predicting unmet dental care need. Future research may benefit from tools that better capture the severity of ASD, such as the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), which emphasizes identifying symptoms of autism earlier in childhood.40

CONCLUSION

This study contributes to a growing body of evidence that shows children with ASD experience greater unmet dental need than their peers. Factors such as not having a medical home, having an intellectual disability, or having behavioral or communication difficulties may be used to identify children with ASD with unmet dental need. Our finding that children without a medical home had more unmet dental need highlights the importance of access to a regular source of health care for maintenance of general and oral health. By establishing strong relationships with dental colleagues, pediatricians and PCPs facilitate children with ASD receiving needed dental care and help optimize oral health outcomes for this population.

WHAT’S NEW.

A medical home seems to help children with ASD receive needed dental care. Certain children with ASD with intellectual disability, communication, or behavioral difficulties are more apt to have unmet dental need and require a dentist with expertise in ASD.

Acknolwedgements

Dr. McKinney’s time was funded under NIH/NCATS grant 2 KL2 TR000421-06. Dr. Heaton’s time was funded by NIH/NIDCR grant 5K23DE019202.

Abbreviations

- ADD/ADHD

attention deficit disorder/attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

- ASD

Autism Spectrum Disorder

- CI

confidence interval

- CSHCN

Children with Special Healthcare Needs

- NS-CSHCN

National Survey of Children with Special Healthcare Needs

- OR

odds ratio

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Potential Conflicts of Interest / Corporate Sponsors: None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yu SM, Bellamy HA, Kogan MD, Dunbar JL, Schwalberg RH, Schuster MA. Factors that influence receipt of recommended preventive pediatric health and dental care. Pediatrics. 2002 Dec;110(6):e73. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.6.e73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iida H, Lewis CW. Utility of a summative scale based on the Children with Special Health Care Needs (CSHCN) Screener to identify CSHCN with special dental care needs. Maternal and child health journal. 2012 Aug;16(6):1164–1172. doi: 10.1007/s10995-011-0894-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lewis C, Robertson AS, Phelps S. Unmet dental care needs among children with special health care needs: implications for the medical home. Pediatrics. 2005 Sep;116(3):e426–e431. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bloom B, Cohen RA, Freeman G. Summary health statistics for U.S. children: National Health Interview Survey, 2010. Vital and health statistics. Series 10, Data from the National Health Survey. 2011 Dec;(250):1–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Surgeon General. Oral Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: United States Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Improving Access to Oral Health Care for Vulnerable and Underserved Populations. THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS; 2011. Committee on Oral Health Access to Services, Institute of Medicine, National Research Council. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence of the Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASDs) in Multiple Areas of the United States, 2004 and 2006: Community Report from the Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring (ADDM) Network. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorders — Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 14 Sites, United States, 2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012 Mar 30;61(3):1–19. 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blumberg SJ, Bramlett MD, Kogan MD, Schieve LA, Jones JR, Lu MC. Changes in Prevalence of Parent-reported Autism Spectrum Disorder in School-aged U.S. Children: 2007 to 2011–2012. 2013 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kopycka-Kedzierawski DT, Auinger P. Dental needs and status of autistic children: results from the National Survey of Children's Health. Pediatric dentistry. 2008 Jan-Feb;30(1):54–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lewis CW. Dental care and children with special health care needs: a population-based perspective. Academic pediatrics. 2009 Nov-Dec;9(6):420–426. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stein LI, Polido JC, Cermak SA. Oral care and sensory over-responsivity in children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatric dentistry. 2013;35(3):230–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stein LI, Polido JC, Najera SO, Cermak SA. Oral care experiences and challenges in children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatric dentistry. 2012 Sep-Oct;34(5):387–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stein LI, Polido JC, Mailloux Z, Coleman GG, Cermak SA. Oral care and sensory sensitivities in children with autism spectrum disorders. Special care in dentistry : official publication of the American Association of Hospital Dentists, the Academy of Dentistry for the Handicapped, and the American Society for Geriatric Dentistry. 2011 May-Jun;31(3):102–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.2011.00187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lai B, Milano M, Roberts MW, Hooper SR. Unmet dental needs and barriers to dental care among children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of autism and developmental disorders. 2012 Jul;42(7):1294–1303. doi: 10.1007/s10803-011-1362-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brickhouse TH, Farrington FH, Best AM, Ellsworth CW. Barriers to dental care for children in Virginia with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of dentistry for children (Chicago, Ill.) 2009 Sep-Dec;76(3):188–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nelson LP, Getzin A, Graham D, et al. Unmet dental needs and barriers to care for children with significant special health care needs. Pediatric dentistry. 2011 Jan-Feb;33(1):29–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strickland BB, Jones JR, Ghandour RM, Kogan MD, Newacheck PW. The medical home: health care access and impact for children and youth in the United States. Pediatrics. 2011 Apr;127(4):604–611. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin AB, Crawford S, Probst JC, et al. Medical homes for children with special health care needs: a program evaluation. Journal of health care for the poor and underserved. 2007 Nov;18(4):916–930. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2007.0099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Homer CJ, Klatka K, Romm D, et al. A review of the evidence for the medical home for children with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2008 Oct;122(4):e922–e937. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative (CAHMI) 2009–2010 NS-CSHCN Indicator and Outcome Variables SAS Codebook, Version 1. Data Resource Center for Child and Adolescent Health. 2012 www.childhealthdata.org. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative (CAHMI) National Survey of Children with Special Healthcare Needs (2009/10 NS-CSHCN): Fast Facts. [Accessed July 1, 2013]; http://www.childhealthdata.org/learn/facts. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Data Resource Center for Child & Adolescent Health. 2009/10 National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs (2009/10 NS-CSHCN) - Sampling and Survey Administration Process. [Accessed 21 November, 2013]; http://childhealthdata.org/docs/default-document-library/2009-nscshcn-survey-sampling-administration.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bethell CD, Read D, Stein RE, Blumberg SJ, Wells N, Newacheck PW. Identifying children with special health care needs: development and evaluation of a short screening instrument. Ambulatory pediatrics : the official journal of the Ambulatory Pediatric Association. 2002 Jan-Feb;2(1):38–48. doi: 10.1367/1539-4409(2002)002<0038:icwshc>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McPherson M, Arango P, Fox H, et al. A new definition of children with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 1998 Jul;102(1 Pt 1):137–140. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.1.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative (CAHMI) National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs (NS-CSHCN), 2009 – 2010: Guide to Topics & Questions Asked. Data Resource Center for Child and Adolescent Health. 2012 www.childhealthdata.org. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) [Accessed 22 May, 2014];2014 http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/data.html.

- 28.Savage MF, Lee JY, Kotch JB, Vann WF., Jr Early preventive dental visits: effects on subsequent utilization and costs. Pediatrics. 2004 Oct;114(4):e418–e423. doi: 10.1542/peds.2003-0469-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Health and Human Services. Visits to a dentist during the past year among those aged 2 years and older. [Accessed May 28, 2014];2014 http://drc.hhs.gov/report/dqs_tables/pdf/4.pdf. 2014.

- 30.Data Resource Center for Child & Adolescent Health. 2009–2010 National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs. [Accessed May 21, 2014];2011 http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/slaits/NS_CSHCN_Questionnaire_09_10.pdf.

- 31.CAHMI - The Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative. Measuring Medical Home for Children and Youth: Methods and Findings from the National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs and the National Survey of Children’s Health. Oregon Health Sciences University; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Policy statement: organizational principles to guide and define the child health care system and/or improve the health of all children. Pediatrics. 2004 May;113(5 Suppl):1545–1547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Policy on the dental home. Pediatric dentistry. 2008;30(7 Suppl):22–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hale KJ. Oral health risk assessment timing and establishment of the dental home. Pediatrics. 2003 May;111(5 Pt 1):1113–1116. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.5.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.dela Cruz GG, Rozier RG, Slade G. Dental screening and referral of young children by pediatric primary care providers. Pediatrics. 2004 Nov;114(5):e642–e652. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rozier RG, Stearns SC, Pahel BT, Quinonez RB, Park J. How a North Carolina program boosted preventive oral health services for low-income children. Health affairs (Project Hope) 2010 Dec;29(12):2278–2285. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.PEW Charitable Trusts. Reimbursing Physicians for Fluoride Varnish. [Accessed 23 February, 2014]; http://www.pewstates.org/research/analysis/reimbursing-physicians-for-fluoride-varnish-85899377335. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Al Agili DE, Bronstein JM, Greene-McIntyre M. Access and utilization of dental services by Alabama Medicaid-enrolled children: a parent perspective. Pediatric dentistry. 2005 Sep-Oct;27(5):414–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Raposa KA. Behavioral management for patients with intellectual and developmental disorders. Dental clinics of North America. 2009 Apr;53(2):359–373. xi. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2008.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]