Abstract

Importance

Common single nucleotide polymorphisms in the SORL1 gene have been associated with late onset Alzheimer’s disease (LOAD) but causal variants have not been fully characterized nor has the mechanism been established.

Objective

To identify functional SORL1 mutations in patients with LOAD.

Design and Participants

This was a family- and cohort-based genetic association study. Caribbean Hispanics with familial and sporadic LOAD and similarly aged controls recruited from the United States and the Dominican Republic, and patients with sporadic disease of Northern European origin recruited from Canada.

Main Outcome Measure(s)

Prioritized coding variants in SORL1 detected by targeted re-sequencing and validated by genotyping in additional family members and unrelated healthy controls. Variants transfected into human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK) cell lines were tested for Aβ40 and Aβ42 secretion and the amount of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) secreted at the cell surface was determined.

Results

17 coding exonic variants were significantly associated with disease. Two rare variants (rs117260922-E270K and rs143571823-T947M) with MAF<1% and one common variant (rs2298813-A528T) with MAF=14.9% segregated within families and were deemed deleterious to the coding protein. Transfected cell lines showed increased Aβ40 and Aβ42 secretion for the rare variants (E270K and T947M) and increased Aβ42 secretion for the common variant (A528T). All mutants increased the amount of APP at the cell surface, though in slightly different ways, thereby failing to direct full-length APP into the retromer-recycling endosome pathway.

Conclusions and Relevance

Common and rare variants in SORL1 elevate the risk of LOAD by directly affecting APP processing which, in turn can result in increased Aβ40 and Aβ42 secretion.

Keywords: SORL1, common and rare variants, amyloid β, Alzheimer’s disease

INTRODUCTION

The sortilin-related receptor, L(DLR class) A-type repeats containing (SORL1) is a member of the vacuolar protein sorting-10 domain-containing receptor family, and participates in the intracellular vesicular sorting of APP after re-internalization from the cell surface1, 2. SORL1 determines whether APP is sorted in the retromer recycling-endosome pathway or allowed to drift into the endosome-lysosome pathway where it is cleaved to generate Aβ. Variants in the SORL1 gene might alter this activity, leading to an increase in Aβ that, in turn, contributes to the pathogenesis of late onset Alzheimer’s disease (LOAD)3. To date, despite compelling evidence from case-control, family-based and genome-wide association studies (GWAS)3–11, clearly pathogenic variants have not been identified making it difficult to investigate the functional consequences of specific SORL1 mutations.

METHODS

Targeted re-sequencing and analysis methods

Sample Selection and Preparation. We sequenced one affected individual with LOAD, usually the proband, from 151 families with multiple affected family members. The mean age at onset for affecteds was 77.03 years (SD=8.93), ranging from 45 to 98 years. 69.5% of the family members were women and the mean years of education was 4.3 years (SD=4.61). We extracted genomic DNA from whole blood with 0.16% samples from saliva. Blood samples were extracted using the Qiagen method and saliva samples were extracted using the Oragene method. The DNA was then quantified using the PicoGreen detection method, following the manufacturer specifications (InVitrogen, Carlsbad CA).

We validated the prioritized variants by genotyping the sequenced probands and their 464 relatives, of whom 350 were affected and 114 were unaffected. For the sequencing experiment we pooled DNA samples using 235 samples across 24 pools with each pool comprising 10 unrelated samples (5 samples failed sequencing).

Targeted Re-sequencing. We performed the RainDance (http://raindancetech.com/targeted-dna-sequencing) for capture and then followed with pooled sequencing using the Illumina GAII platform (http://www.illumina.com). In total, we sequenced 201,510 bp including both exons and introns of the SORL1 gene as well as the flanking region, covering from 121,312,961bp to 121,514,471bp.

Variant Calling and post-processing. We aligned the reads obtained from the pooled sequencing to the human reference genome build 37 using the Burrows Wheeler Aligner12 (http://bio-bwa.sourceforge.net/). Quality control of the sequencing data was done using established methods, including base alignment quality calibration and refinement of local alignment around putative indels using the Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK)13. We used SAMTOOLS14 mpileup to call variants in the pooled dataset and validated calls by an independent calling algorithm called CRISP (Comprehensive Read analysis for Identification of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) from Pooled sequencing)15. Variant calls were filtered using mpileup filters for base quality (baseQ bias), mapping quality (mapQ bias), strand bias, tail distance bias and number of non-reference reads to obtain high quality variants. Reliably called variants were annotated by ANNOVAR16 including in-silico functional prediction using POLYPHEN17 software extent of cross-species conservation using PHYLOP18.

Genotyping. To validate novel variants discovered in probands, we genotyped the probands, and their family members. To investigate whether the allele frequencies for novel variants differed from unaffected persons in the general Caribbean Hispanic population, we genotyped 498 unaffected persons who were unrelated to any of the family members. These 498 individuals underwent the same phenotypic and diagnostic protocols. Genotyping was conducted on the Sequenom platform. When the Sequenom platform failed to generate genotype due to difficulties with primers, we performed Sanger sequencing.

Statistical Analysis. To assess whether a set of rare and common variants in SORL1 increases the risk of LOAD, we performed a gene-wise analysis using in the SNP-set Kernel Association test (SKAT)19 for heterozygous variants in exons and introns with and without adjustments for covariates such as age, sex and APOE genotype. We also used statically estimated haplotypes coupled with generalized estimating equations (GEE) to establish joint burden of 17 SNVs by accurately adjusting for the correlation between samples. To assess the individual effects of SNPs, we performed joint linkage and association analysis with PSEUDOMARKER20 using all family members and unrelated controls. This analytical method allows us to analyze family data, unrelated subjects, or both to determine whether a variant is associated with disease. For constructing haplotypes, we used the R based haplo.stats package21 (http://mayoresearch.mayo.edu/mayo/research/schaid_lab/software.cfm).

Functional studies

Site directed mutagenesis. SORL1 E270K, A528T and T947M mutations were generated by site directed mutagenesis using human SORL1-MYC pcDNA3.1 as a backbone according to manufacturer's instructions1, 2. All mutant constructs were verified by sequencing.

Cell culture and transfection. HEK293 cells stably expressing the Swedish APP mutant (APPsw)22 were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, Gibco) with 10% fetal bovine serum and Geneticin (200 μg/ml). Wild-type SORL1-MYC pcDNA3.1 and three generated SORL1 mutant constructs (SORL1 E270K -MYC pcDNA3.1, SORL1 A528T -MYC pcDNA3.1, SORL1 T947M -MYC pcDNA3.1) were transfected transiently into HEK293 APPsw cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Stable clones were selected using Hygromycin (200 μg/ml) and Geneticin (400 μg/ml) to generate stable cell lines overexpressing either wild-type or mutant SORL1.

Aβ assays. Measurement of secreted Aβ40, Aβ42 and sAPPβ from culture medium in HEK293 APPsw cells23, wild-type SORL1 and mutant SORL1 stable HEK293 APPsw cells by sandwich ELISA according to manufacturer's protocol.

Antibodies and Western Blot. Antibodies were used as follows: rabbit antibody to the C-terminus of SORL1 (S9200, Sigma); rabbit polyclonal antibody to PS1-NTF (A4, from our lab); mouse monoclonal anti-c-MYC (Invitrogen); rabbit polyclonal antibody to the C terminus of APP (Ab365, Sigma); mouse monoclonal anti-Aβ (6E10, Covance).

Culture medium from HEK293 APPsw cells, wild-type SORL1 and mutant SORL1 stable cell lines were harvested and subjected to immunoblotting. Secreted sAPPα levels were analyzed by western blot using anti-Aβ (6E10); samples were normalized to the protein concentration of the collected cell lysates, which were measured by BCA protein assay (Biorad). The cell lysates were analyzed in a Western blot with FL-APP (full-length APP), PS1-NTF (Presenilin 1), APP-CTFs (APP-β-CTF(C83) and APP-α-CTF(C99)). Band intensities were quantified using NIH Image J software and relative expression levels of FL-APP, total APP-CTFs, PS1 were normalized to β-actin. Bar graphs were normalized to wild-type SORL1 control.

Cell surface biotinylation: Cells were washed with Buffer A (PBS with 1 mM MgCl2, pH 8.0) and incubated with 1 mg/ml Sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotin (Sigma) in buffer A for 20 min at 4°C to prevent internalization. Cells were then washed with ice-cold 20 mM glycine in Buffer A, lysed, and biotinylated proteins precipitated with Neutravidin beads (Thermo Sci).

Protein lysates were immunoblotted with Anti-C-terminal APP antibody (Ab365, Sigma) and Anti-C-terminal SORL1 antibody (S9200, Sigma). Immunoprecipitated cell surface APP (IP) was normalized to total APP (Input). Western blot bands intensities were measured with NIH Image J software. Bar graphs were normalized to wild-type control.

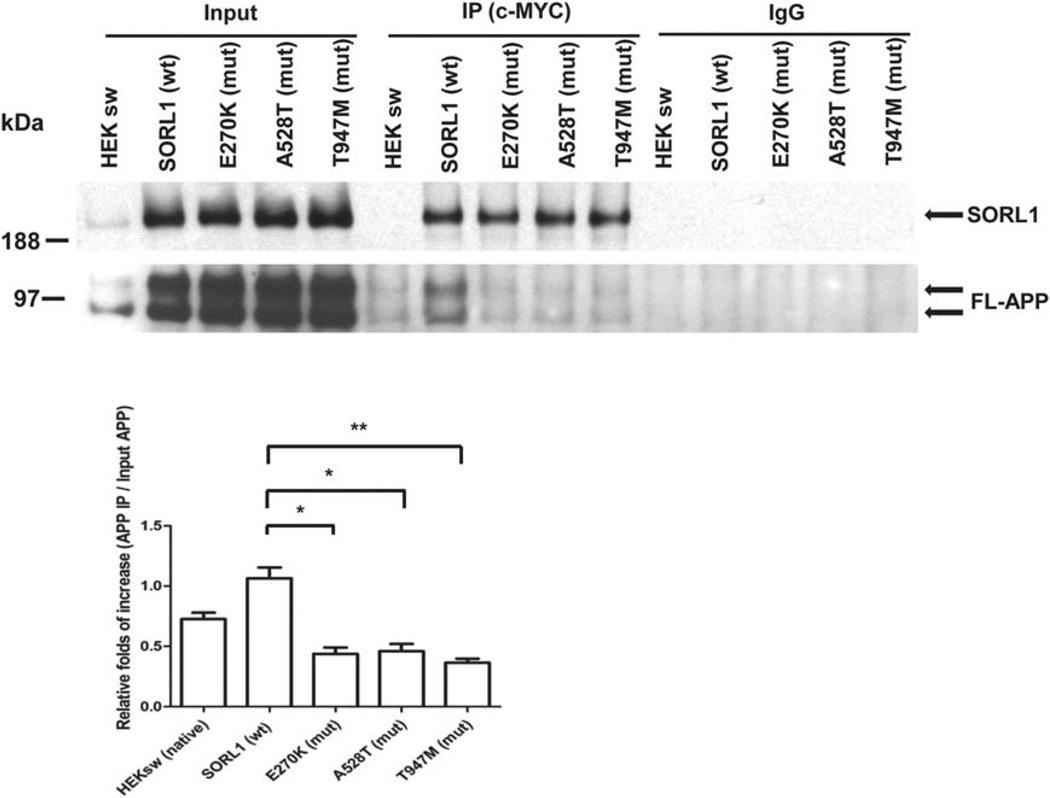

Co-Immunoprecipitation. Cells were lysed in 1% CHAPSO buffer24, immunoprecipitated using G Plus beads with 2 µg mouse monoclonal anti-c-MYC antibody (for immunoprecipitation of SORL1-myc), immunoblotted with Anti-C-terminal APP antibody (Ab365), and Anti-C-terminal SORL1 (S9200). Full-length APP co-precipitated with c-MYC antibody was quantified and normalized to the amount of immunoprecipated SORL1.

Statistical analysis. Graphpad Statistical software (GraphPad Prism 5) was used to generate Bar Charts and Anova with t-test was used to analyze statistical difference, followed by Bonferroni correction. One asterisk represents p<0.05; two asterisks represent p<0.01; and three asterisks represent p<0.001.

RESULTS

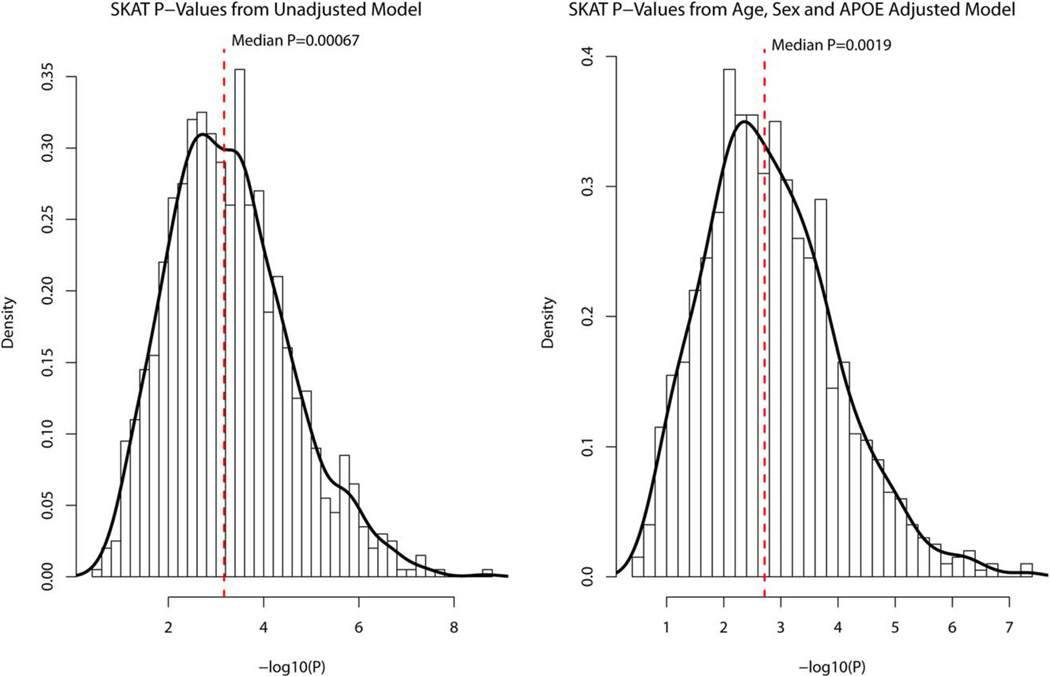

Genetic Analyses. Analysis of the sequence data allowed prioritization of 17 exonic coding variants including 13 non-synonymous mutations three frame-shift deletions and one synonymous mutation (Table 1). We validated variant calls by Sequenom genotyping in the sequenced probands, additional family members from 87 families that contained at least one heterozygous carrier (464 total familial subjects-350 affecteds and 114 unaffecteds) and 498 unrelated, age-matched Caribbean Hispanic controls. The combined gene burden SKAT19 analysis confirmed that the joint burden of 17 heterozygous variants were significantly associated with LOAD (punadjusted = 0.0009; padjusted for age and gender covariates = 0.0079). The SKAT test assumes independence of observations but does not adjust for familial correlation. Thus, we conducted SKAT analysis on unrelateds creating a dataset by randomly selecting one member from each of the 87 families, and combined them with the 498 controls to create a “case-control” set. We repeated this process 1000 times to create 1000 case-control datasets and conducted SKAT analysis using unadjusted and age, sex and APOE adjusted models. 961 out of 1000 (96%) of the unadjusted model datasets and 909 out of 1000 (91%) adjusted model datasets produced significant p-values (p<0.05) for and respectively. We observed median p-values of p=0.00067 for the unadjusted model and p=0.002 for the adjusted model respectively (Fig. 5a and 5b). These observations are consistent with the SKAT analysis using all family members. In case of a null association we would have expected 5% of the datasets to produce nominally significant p-values. The significant deviation from the expectation provides further evidence of the joint burden of 17 SNVs in modifying LOAD risk.

Table 1.

List of variants prioritized for follow-up genotyping and p-values using linkage and association test implemented in Pseudomarker.

| CARIBBEAN HISPANIC FREQUENCY |

ADNI OMNI CHIP FREQUENCY |

ADNI WGS FREQUENCY |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNP | BP (HG19) | P (LD+Link) |

A1* | A2 | Controls (n=498) |

AFFECTED (n=87 fams, 462) |

AD+MCI (n=531) |

CONTROL (n=82) |

AD+MCI (n=531) |

CONTROL (n=281) |

Function+ | AA Change |

ESP Frequency |

Polyphen++ | Conservation^ |

| rs117260922 | 121367627 | 7.68E-07 | 1 | 3 | 0.010040 | 0.01166 | NS | E270K | 0.007529 | D | C | ||||

| rs2298813 | 121393684 | 6.09E-07 | 1 | 3 | 0.091370 | 0.15598 | 0.05849 | 0.047 | 0.05039 | 0.04029 | NS | A528T | 0.061536 | P | C |

| 11-121428111 | 121428111 | 1.49E-03 | 3 | 1 | 0.001004 | 0.00146 | NS | E887G | B | C | |||||

| rs143571823 | 121429476 | 7.00E-06 | 4 | 2 | 0.007028 | 0.00729 | 0.00000 | 0.00183 | NS | T947M | 0.004927 | P | C | ||

| 11-121437722 | 121437722 | 5.00E-05 | 2 | 3 | 0.002008 | 0.00583 | NS | R1041S | B | C | |||||

| rs1699107 | 121437819 | 1.41E-10 | 2 | 3 | 0.019080 | 0.02770 | 0.00194 | 0.00183 | S | Q1074Q | |||||

| rs146903951 | 121440937 | 6.00E-06 | 2 | 4 | 0.007042 | 0.01020 | 0.01453 | 0.01648 | NS | F1099L | 0.007436 | B | C | ||

| rs62617129 | 121444958 | 2.00E-03 | 3 | 1 | 0.003012 | 0.00583 | 0.00484 | 0.00366 | NS | I1116V | 0.006228 | B | N | ||

| rs114830255 | 121454206 | 4.00E-06 | 1 | 3 | 0.001004 | 0.00875 | 0.00097 | 0.00183 | NS | R1207Q | 0.005298 | B | N | ||

| 11-121458818 | 121458818 | 1.16E-04 | 0** | 4 | 0.000000 | 0.00292 | FSD | C1302fs | |||||||

| rs146353234 | 121461799 | 8.96E-07 | 4 | 1 | 0.002008 | 0.00583 | 0.00000 | 0.00366 | NS | T1435S | 0.000744 | B | C | ||

| 11-121474914 | 121474914 | 2.70E-03 | 4 | 2 | 0.002008 | 0.00292 | NS | T1511I | B | C | |||||

| 11-121476260 | 121476260 | 8.86E-04 | 0 | 2 | 0.000000 | 0.00437 | FSD | T1643fs | |||||||

| rs62622819 | 121485599 | 1.50E-04 | 1 | 4 | 0.003012 | 0.00875 | 0.00969 | 0.00916 | NS | H1813Q | 0.006042 | P | N | ||

| rs1792120 | 121491782 | 7.42E-10 | 3 | 1 | 0.013050 | 0.03353 | 0.00194 | 0.00183 | NS | V1967I | 0.0002 | B | N | ||

| rs74811057 | 121495870 | 1.74E-03 | 3 | 1 | 0.014060 | 0.00583 | 0.00000 | 0.00183 | NS | K2083R | 0.013664 | B | C | ||

| 11-121498387 | 121498387 | 9.82E-04 | 0 | 3 | 0.000000 | 0.00437 | FSD | R2163fs | |||||||

Minor allele

Homozygous wild type

SNV Function: NS= Non-synonymous SNV, S= Synonymous SNV, FSD= Frame-shift Deletion

Polyphen Prediction: D=Damaging, P=Possibly Damaging, B=Benign

Phylop Conservation Prediction: C=Conserved, N=Not Conserved

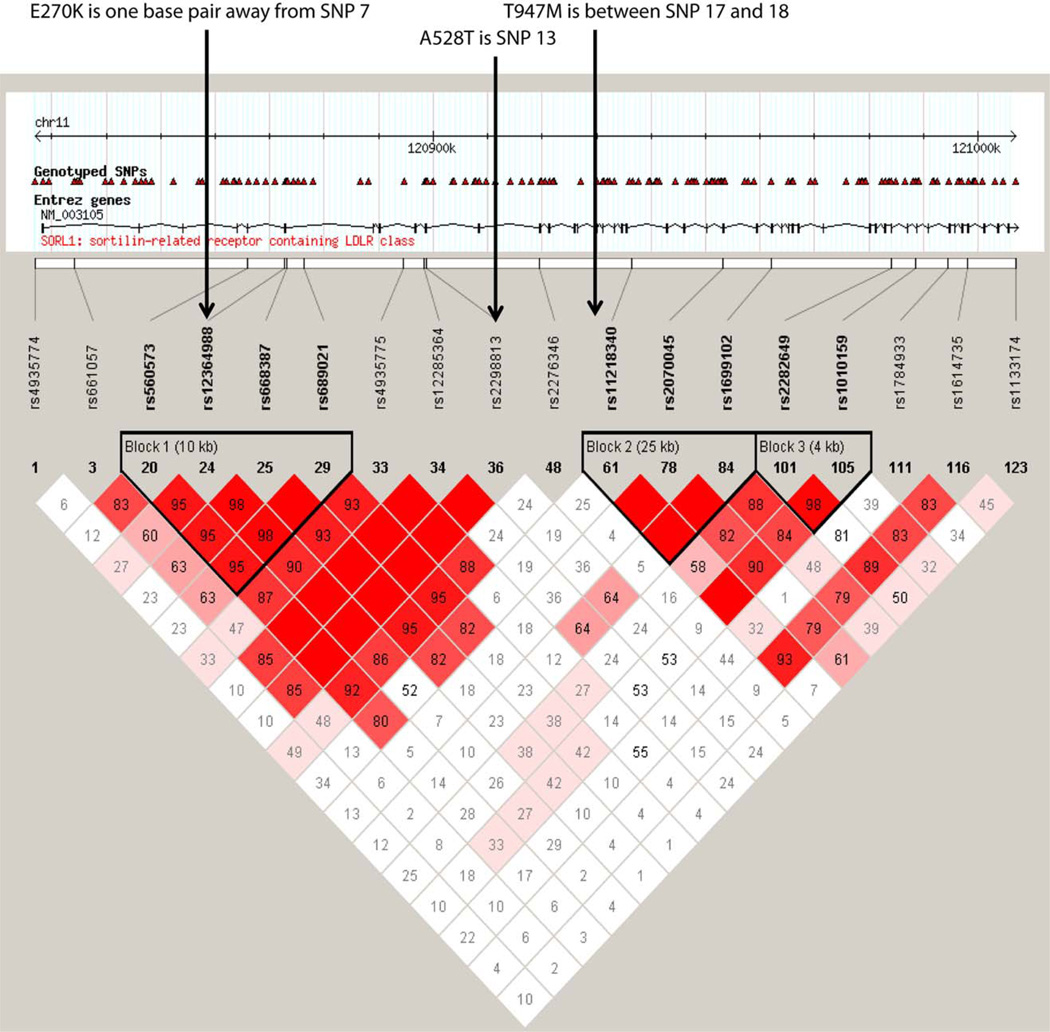

FIGURE 5.

Position of the coding mutations relative to the single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) significantly associated with Alzheimer disease (Rogaeva et al3).

Because of lack of appropriate methods for gene- or region-based burden methods for dichotomous traits that adjust for familial correlations, we performed additional haplotype analyses to assess the joint association of the 17 SNPs with LOAD and related traits. Defining the major allele as most frequent haplotype observed in 78% of the samples (Table 4a) and combining the remaining haplotypes into the minor allele, we computed association with LOAD using GEE. We included 933 (out of 962) subjects in the association analysis with haplotype pairs estimated at a posterior probability of p=1. The rare haplotypes increased disease risk and were strongly associated with LOAD (OR=1.9, p=6.9e-05) (Table 4b). This observation is consistent with the increased frequency of the minor alleles of several of the 17 SNPs in LOAD vs controls (Table 1).

Table 4.

| a): Haplotype Analysis SORL1 coding mutations: A) Frequency of haplotype combinations of the 17 SNPs (Haplo Stats) | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haplotype | SNP1 | SNP2 | SNP3 | SNP4 | SNP5 | SNP6 | SNP7 | SNP8 | SNP9 | SNP10 | SNP11 | SNP12 | SNP13 | SNP14 | SNP15 | SNP16 | SNP17 | hap.freq |

| 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0.00028 |

| 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0.01065 |

| 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0 |

| 4 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0.00161 |

| 5 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.00156 |

| 6 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0.11336 |

| 7 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 0.00001 |

| 8 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0.00156 |

| 9 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0.00416 |

| 10 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0.00156 |

| 11 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0.00092 |

| 12 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0.01759 |

| 13 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 0.00093 |

| 14 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0.00938 |

| 15 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0.00469 |

| 16 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0.00103 |

| 17 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0.00104 |

| 18 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0.00533 |

| 19 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0.78103 |

| 20 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 0.00481 |

| 21 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 0.02184 |

| 22 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0.00157 |

| 23 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0.00364 |

| 24 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0.00468 |

| 25 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0.00052 |

| 26 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 0.00416 |

| 27 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 0.00052 |

| 28 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0.00105 |

| 29 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 0.00051 |

| 4b) Association test of Haplotype 19 using Generalized Estimation Equations (GEE) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BETA | SE | Z | P | |

| h19haplotype | 0.643541 | 0.16 | 15.83 | 6.91E-05 |

(subjects were coded based on haplotype copies of haplotype 19 (0=2 copies of 19, 1= 1copy of 19 and 2=0 copies of 19 Subjects with haplotype pairs estimated with posterior probability=1 used for the association analysis)

To assess individual significance of the single nucleotide variants (SNVs), we conducted joint linkage and association of the 17 variants with LOAD in the subset of 87 families and the unrelated controls. The analysis revealed that all 17 SNVs were significantly associated with disease at a Bonferroni corrected p-value p<0.0029. However, three of the variants showed significant segregation with disease under a dominant affecteds only model: rs2298813 (A528T; p=6.09E-7), rs117260922 (E270K; p=7.68E-7) and rs143571823 (T947M; p=7.0E-6). Variant rs2298813 was most frequent being present in 54 families, in contrast to variant rs117260922 detected in seven families, and variant rs143571823 detected in four families.

To assess whether these findings were applicable to ethnic groups other than Caribbean Hispanics, we also re-sequenced SORL1 in 211 patients of Northern European ancestry (Table 2). We detected 13 rare missense variations and a 3 base-pair deletion eliminating a highly conserved residue p.N174 (Table 3). Seven of these variations are predicted to be damaging, including three novel variations. Of the 14 rare variations identified, seven overlapped with the mutations detected in the Caribbean Hispanic patients including two of the coding mutations rs2298813 and rs117260922. Their frequencies were higher than or comparable to Caucasian population in the 1000 genomes database, but much lower than observed in the Caribbean Hispanics.

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of sequenced individuals

| Characteristics | Caribbean Hispanic Affecteds (n=154) |

Caribbean Hispanic Unaffecteds (n=80) |

N. European Caucasian Affecteds (n=211) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Age at Onset or last examination: years ± SD | 77.0 ± 8.9 | 83.9 ± 3.8 | 73.0 ± 7.8 |

| Mean years of Education ± SD | 4.3 ± 4.6 | 7.0 ± 4.0 | not available |

| Women: n (%) | 107 (69.5) | 57 (71.3) | 107 (50.7) |

| APOE ε4: % | 22.8 | 11.9 | 38.0 |

Table 3.

Coding SORL1 variations detected in 211 cases of N. European ancestry

| SNP | BP (HG19) | A1** | A2 | # cases |

MAF | 1000g-CEU Frequency | ESP Frequency |

Function+ | AA Change |

Polyphen++ | Conservation^ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11-121348942 | del 121348942-121348944 | del | ACA | 2 | 0.005 | NA | NA | deletion | 173_174del | NA | C |

| rs117260922* | 121367627 | A | G | 14 | 0.033 | 0.0059 | 0.007459 | NS | E270K | D | C |

| rs150609294 | 121384931 | C | A | 1 | 0.002 | 0 | 0.001 | NS | N371T | D | C |

| rs2298813* | 121393684 | A | G | 18 | 0.045 | 0.0471 | 0.060366 | NS | A528T | P | C |

| rs146903951* | 121440937 | C | T | 3 | 0.007 | 0.0059 | 0.007921 | NS | F1099L | B | C |

| rs62617129* | 121444958 | G | A | 3 | 0.007 | 0.0059 | 0.006075 | NS | I1116V | B | N |

| 11-121458817 | 121458817 | T | G | 1 | 0.002 | NA | NA | NS | Q1301H | B | C |

| 11-121460792 | 121460792 | G | T | 1 | 0.002 | NA | NA | NS | F1374L | D | C |

| rs199717181 | 121474988 | A | G | 1 | 0.002 | 0 | 0.000231 | NS | G1536S | D | C |

| rs138580875 | 121475859 | C | G | 1 | 0.002 | NA | 0.000615 | NS | W1563C | D | C |

| rs62622819* | 121485599 | A | T | 5 | 0.012 | 0.0235 | 0.005999 | NS | H1813Q | P | N |

| rs1792120* | 121491782 | G | A | 1 | 0.002 | 0 | 0.01669 | NS | V1967I | B | N |

| rs140327834 | 121495816 | T | A | 2 | 0.005 | 0 | 0.00423 | NS | D2065V | D | C |

| rs74811057* | 121495870 | G | A | 1 | 0.002 | 0 | 0.013229 | NS | K2083R | B | C |

Found in Caribbean Hispanics

Minor allele

SNV Function: NS= Non-synonymous SNV

Polyphen Prediction: D=Damaging, P=Possibly Damaging, B=Benign

Phylop Conservation Prediction: C=Conserved, N=Not Conserved

We also compared the minor allele frequencies of the 17 coding-SORL1 SNVs discovered in the Hispanics with those observed in the whole-genome sequencing (WGS) and the exome-chip data from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) dataset25 (https://ida.loni.usc.edu/login.jsp?project=ADNI&page=HOME). We used baseline phenotypes from ADNI samples to compute frequencies of LOAD and mild cognitive impairment compared to controls. The frequency of the common SNP rs2298813 (A528T) (Table 1) was concordant with the observations in the Hispanic cohort, but the allele frequencies were much lower than in the Caribbean Hispanics. The rare SNP rs143571823 (T947M) was heterozygous in one ADNI control and was not found in any case. SNP rs117260922 (E270K) was not observed in the entire ADNI dataset. Differences in allele frequencies between Caribbean Hispanics and the Caucasians in the ADNI study could be conferred by differences in sequencing technologies, capture platforms, sequencing depth and variant calling algorithms in the two experiments. We evaluated the effects of the 45 rare SORL1 missense mutations observed in the ADNI dataset at a sample MAF<0.01 using the SKAT test. The SKAT test of rare missense mutations in demented versus healthy controls in the ADNI samples was significant (p=0.037).

Caribbean Hispanics are known to be an admixed population, therefore we also investigated the association of the rs2298813 in a meta-analyses LOAD study African Americans26. The SNP was significant in African Americans at P=0.01 and is observed with a higher frequency in cases compared with controls.

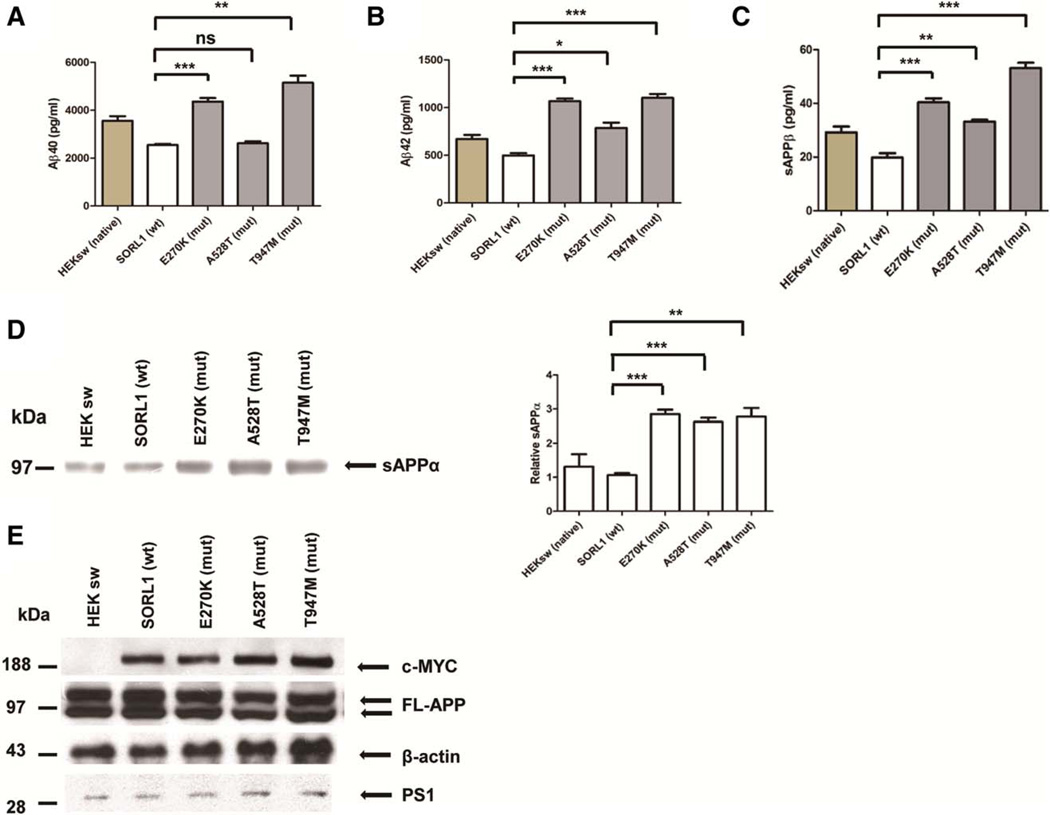

Functional Analyses. We tested the impact of three most significant SORL1 mutations on Aβ production. Clonal HEK293sw cell lines stably overexpressing similar quantities of wild-type and mutant SORL1 were generated. Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels were then measured in conditioned media from the cells. Wild-type and mutant SORL1 were expressed at the same levels, yet the E270K and T947M mutants both resulted in a significant increase in Aβ40 secretion (E270K, 171 ± 5.6% of control value, p <0.001; T947M, 202 ± 11.6% of control value, p <0.01; n=3 independent replications, Fig. 1a) and Aβ42 secretion (E270K, 214 ± 5.7% of control value, p <0.001; T947M, 221 ± 8.4% of control value, p <0.001; n=3 independent replications, Fig. 1b). The A528T mutant increased Aβ42 secretion moderately (158 ± 11.1% of control value, p <0.01; n=3 replications, Fig. 1b), but did not change the Aβ40 secretion (103 ± 3.3% of control value, p >0.05; n=3 independent replications, Fig. 1a).

FIGURE 1.

Histogram of −log10 of the probability values obtained from SNP-set Kernel Association Test (SKAT) analysis of 1,000 data sets created by randomly choosing 1 subject from each of the 87 families and 498 controls. The SKAT analysis was conducted assuming for the unadjusted model: Alzheimer disease (AD) ~ single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) burden; and for the model with age, sex, and apolipoprotein E (APOE) ε4 status as covariates: AD ~ SNP burden + age + sex + APOE ε4 yes/no. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.annalsofneurology.org.]

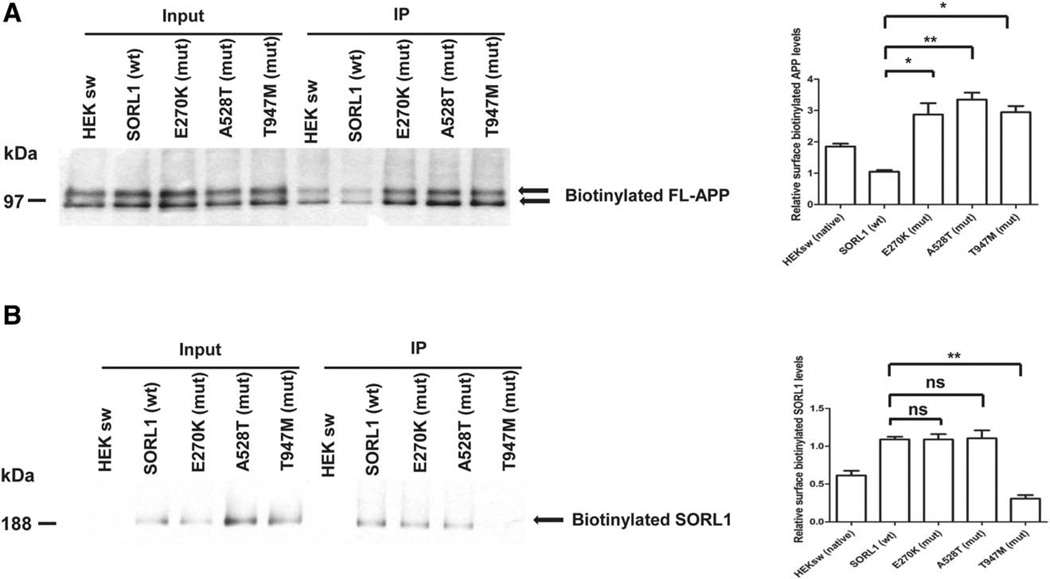

All three mutations caused significant increases in sAPPα and sAPPβ secretion compared to wild-type SORL1. Thus, for sAPPα: (E270K, 266 ± 13.0% of control value, p <0.001; A528T, 246 ± 12.0% of control value, p <0.001; T947M, 259 ± 25.2% of control value, p <0.01; n=3 independent replications, Fig. 1d); and for sAPPβ: (E270K, 204 ± 7.2% of control value, p <0.001; A528T, 167 ± 3.5% of control value, p <0.01; T947M, 268 ± 10.3% of control value, p <0.001; n=3 independent replications, Fig. 1c). The SORL1 mutants did not alter the levels of either total cellular APP holoprotein or PS1 (Fig. 1e). All the three mutants did increase the amounts of biotinylatable cell-surface APP (E270K, 286 ± 36.2% of control value, p <0.05; A528T, 365 ± 7.8% of control value, p <0.01, T947M, 294 ± 20.1% of control value, p <0.05; n=3 independent replications, Fig. 2a).

FIGURE 2.

Overexpression of SORL1 mutants leads to elevated Aβ secretion. (A–C) Measurement of secreted Aβ40, Aβ42 and sAPPβ from culture medium in stable HEK293 cells expressing the APP Swedish mutant (HEKsw) together with either wild-type (wt) SORL1 or mutant (mut) SORL1. Aβ levels were normalized to the protein levels of the cell lysates. Error bars = standard error of the mean. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ns = not significant after Bonferroni correction; n = 3 independent replications. (D) Cultured media from cells were collected and subjected to Western blot and probed with 6E10 antibody to detect sAPPα. Bar graphs were normalized to control. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, after Bonferroni correction; n = 3 independent replications. (E) Cell lysates were harvested to perform Western blot of full-length amyloid precursor protein (FL-APP) and PS1. β-Actin was used as loading control; n = 3 independent replications.

To understand how these mutants altered APP processing, we assessed the physical interaction of the mutants with APP. Co-immunoprecipitation experiments showed that all three mutations bound APP less well (E270K, ~41 ± 5.1% of control value, p <0.05; A528T, ~43 ± 5.9% of control value, p <0.05; T947M, ~34 ± 3.5% of control value, p <0.01; n=3 independent replications, Fig. 3). However, the mechanism by which this reduced APP:SORL1 interaction occurred, differed significantly. The E270K and A528T mutants displayed normal levels of SORL1 at the cell surface (E270K, 101 ± 7.0% of control value, p >0.05; A528T, 105 ± 10.1% of control value, n=3 replications, Fig. 2b), but failed to physically interact with APP on the cell surface, presumably due to the effect of the mutant on SORL1 conformation. In sharp contrast, the T947M mutant showed decreased amounts of SORL1 at the cell surface (~27 ± 4.5% of control value, *p <0.05; n=3 independent replications, Fig. 2b). The reduced abundance of this mutant at the cell surface clearly accounts for its failure to interact with APP at the cell surface.

FIGURE 3.

The expression of SORL1 mutants (mut) leads to changes of cell surface amyloid precursor protein (APP) and SORL1 levels. Cell surface proteins were biotinylated and precipitated. Surface levels of APP and SORL1 were analyzed by Western blot. (A) APP levels at the cell surface are elevated in all 3 mutants. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, after Bonferroni correction, n = 3 replications. (B) SORL1 surface levels are decreased in the T947M mutant. **p < 0.01, ns = not significant, after Bonferroni correction, n = 3 replications. FL = full length; IP = immunoprecipitated; wt = wild type.

DISCUSSION

Our results indicate that there may be both common and rare variants in SORL1 in some population groups that increase the risk of LOAD. The association with SORL1 has been confirmed in genetic studies of autopsy confirmed LOAD6 and in two meta-analyses involving several thousand patients and controls4, 9. Although, three rare putative variants were identified in European patients with an early onset, autosomal dominant form of Alzheimer’s disease, no confirmatory functional assessment was performed27 and those variants were not detected in the present study. This suggests that the association between SORL1 and LOAD may be related the presence of multiple rare coding mutations, some of which may be population specific.

We based our conclusions about the pathogenic nature of the mutations identified here on two levels of evidence as suggested here28. At the gene level, we demonstrated statistical evidence of an excess of multiple rare, damaging mutations that segregated significantly among cases compared to controls. Previously, we found reduced expression of SORL1 increased the processing of APP into Aβ-generating compartments3. At the variant level, the evidence for pathogenesis of these variants was based on statistical association and segregation within affected families among Caribbean Hispanics, bioinformatics information indicating evolutionary conservation consistent with the deleterious mutations and functional studies in HEK293 cell lines indicating the effects of these mutations on APP processing.

The functional mutations investigated in the current study were either absent or much less frequent in patients of Northern European ancestry and in the ADNI dataset. While the frequency of rs2298813, the most common variant was still increased in cases compared with controls, the difference was not at the level observed in the Caribbean Hispanics and did not reach statistical significance. This may have resulted from the low frequency of this SNP or the small sample size. In contrast, among African Americans the allele frequency was similar to that among Caribbean Hispanics and the variant rs2298813 was found to be significantly associated with LOAD.

It is possible that within the Caribbean Hispanic population this mutation, rs2298812, and the other rare mutations increase risk of disease because they are more penetrant and because there is a strong pattern of inbreeding29 compared to the other populations investigated. Similar observations have been made with in persons with BRCA1 and LRRK2 mutations. BRCA1 mutations are more penetrant among large families of Ashkenazi ancestry with many cases, than in the general population30, and the penetrance of the LRRK2 G2019S mutation can vary by ethnic group among patients with Parkinson disease31.

The three variants in SORL1 identified in the present study show increased secretion of Aβ when transfected into HEK293 cell lines. Interestingly, the rs2298813 (A528T) variant was the most common among the Hispanics and present in 9% of unaffected healthy controls, but 15.6% in familial cases. Intriguingly, all three of these variants map onto or close to SNPs that were associated with LOAD in the original report by Rogaeva et al3. Thus, rs117260922 (E270K) is one nucleotide from SNP7 (rs12364988), rs2298813 (A528T) is SNP13, and rs143571823 (T947M) is located within 3KB region between SNP17 (rs55634) and SNP18 (rs11218340) and is in tight linkage disequilibrium with both SNPs (Fig. 4).

FIGURE 4.

All 3 SORL1 mutants (mut) have a reduced binding affinity to amyloid precursor protein (APP). SORL1 was pulled down from cell lysates with a c-MYC antibody and the amount of coprecipitated full-length APP (FL-APP) was measured. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, after Bonferroni correction, n = 3 replications. IgG = immunoglobulin G; IP = immunoprecipitated; wt = wild type.

The molecular mechanisms underlying this apparently consistent effect of mutants on disease risk appears different between the three mutations. The E270K and the A528T mutants have similar levels of SORL1 at the cell surface as wild-type SORL1-expressing cells. This result suggests that these two mutations do not affect the maturation and trafficking of SORL1 to the cell surface. In contrast, the T947M mutant appears to reach the cell surface less well than wild-type SORL1 or the other SORL1 mutants. This suggests that the T947M mutant may act by causing misfolding of SORL1 in the endoplasmic reticulum and its destruction by quality control mechanisms before the SORL1 protein can reach the cell surface.

Taken together, these data indicate that inherited mutants impair interaction of SORL1 with full-length APP, and thereby fail to direct full-length APP into the retromer-recycling endosome pathway. As a result, in cells expressing mutant SORL1, more of the full-length APP is able to drift into the early and then late endosomes where it is sequentially cleaved by β-secretase and then by γ-secretase to generate increased amounts of Aβ as demonstrated here. Coding SORL1 mutations associated with LOAD in this study likely account in part for the GWAS signals. We demonstrated that a common effect of such mutations is to alter Aβ production via changes in APP processing. However, it is conceivable that other rare mutations may alter different aspects of APP/Aβ metabolism. Indeed, a recently described27 rare mutation (G511R) seemingly alters Aβ binding to SORL1 and may affect the ability of SORL1 to direct lysosomal targeting of nascent Aβ peptides32. When available, the first line of mechanism-based, disease-modifying therapies for carriers of SORL1 mutations should likely be focused on modulating APP processing and Aβ production.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by federal grants from the National Institutes of Health, specifically P50AG08702, R37AG15473, RO1AG037212 and the Marilyn and Henry Taub Foundation (to RM).

The Canadian Institutes of Health Research, National Institute of Health, Wellcome Trust, Medical Research Council, National Institute of Health Research, Ontario Research Fund and Alzheimer Society of Ontario (to PSG-H).

References

- 1.Bohm C, Seibel NM, Henkel B, Steiner H, Haass C, Hampe W. SorLA signaling by regulated intramembrane proteolysis. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006 May 26;281(21):14547–14553. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601660200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lintzel J, Franke I, Riedel IB, Schaller HC, Hampe W. Characterization of the VPS10 domain of SorLA/LR11 as binding site for the neuropeptide HA. Biological chemistry. 2002 Nov;383(11):1727–1733. doi: 10.1515/BC.2002.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rogaeva E, Meng Y, Lee JH, et al. The neuronal sortilin-related receptor SORL1 is genetically associated with Alzheimer disease. Nature genetics. 2007 Feb;39(2):168–177. doi: 10.1038/ng1943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lambert JC, Ibrahim-Verbaas CA, Harold D, et al. Meta-analysis of 74,046 individuals identifies 11 new susceptibility loci for Alzheimer's disease. Nature genetics. 2013 Dec;45(12):1452–1458. doi: 10.1038/ng.2802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee JH, Barral S, Reitz C. The neuronal sortilin-related receptor gene SORL1 and late-onset Alzheimer's disease. Current neurology and neuroscience reports. 2008 Sep;8(5):384–391. doi: 10.1007/s11910-008-0060-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee JH, Cheng R, Honig LS, Vonsattel JP, Clark L, Mayeux R. Association between genetic variants in SORL1 and autopsy-confirmed Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2008 Mar 11;70(11):887–889. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000280581.39755.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee JH, Cheng R, Schupf N, et al. The association between genetic variants in SORL1 and Alzheimer disease in an urban, multiethnic, community-based cohort. Archives of neurology. 2007 Apr;64(4):501–506. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.4.501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meng Y, Lee JH, Cheng R, St George-Hyslop P, Mayeux R, Farrer LA. Association between SORL1 and Alzheimer's disease in a genome-wide study. Neuroreport. 2007 Nov 19;18(17):1761–1764. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3282f13e7a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miyashita A, Koike A, Jun G, et al. SORL1 is genetically associated with late-onset Alzheimer's disease in Japanese, Koreans and Caucasians. PloS one. 2013;8(4):e58618. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reitz C, Cheng R, Rogaeva E, et al. Meta-analysis of the association between variants in SORL1 and Alzheimer disease. Archives of neurology. 2011 Jan;68(1):99–106. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tan EK, Lee J, Chen CP, Teo YY, Zhao Y, Lee WL. SORL1 haplotypes modulate risk of Alzheimer's disease in Chinese. Neurobiology of aging. 2009 Jul;30(7):1048–1051. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009 Jul 15;25(14):1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome research. 2010 Sep;20(9):1297–1303. doi: 10.1101/gr.107524.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009 Aug 15;25(16):2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bansal V. A statistical method for the detection of variants from next-generation resequencing of DNA pools. Bioinformatics. 2010 Jun 15;26(12):i318–i324. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic acids research. 2010 Sep;38(16):e164. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adzhubei I, Jordan DM, Sunyaev SR. Predicting functional effect of human missense mutations using PolyPhen-2. Current protocols in human genetics / editorial board, Jonathan L Haines [et al] 2013 Jan; doi: 10.1002/0471142905.hg0720s76. Chapter 7:Unit7 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pollard KS, Hubisz MJ, Rosenbloom KR, Siepel A. Detection of nonneutral substitution rates on mammalian phylogenies. Genome research. 2010 Jan;20(1):110–121. doi: 10.1101/gr.097857.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu MC, Lee S, Cai T, Li Y, Boehnke M, Lin X. Rare-variant association testing for sequencing data with the sequence kernel association test. American journal of human genetics. 2011 Jul 15;89(1):82–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.05.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hiekkalinna T, Schaffer AA, Lambert B, Norrgrann P, Goring HH, Terwilliger JD. PSEUDOMARKER: a powerful program for joint linkage and/or linkage disequilibrium analysis on mixtures of singletons and related individuals. Human heredity. 2011;71(4):256–266. doi: 10.1159/000329467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schaid DJ, Rowland CM, Tines DE, Jacobson RM, Poland GA. Score tests for association between traits and haplotypes when linkage phase is ambiguous. American journal of human genetics. 2002 Feb;70(2):425–434. doi: 10.1086/338688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu G, Nishimura M, Arawaka S, et al. Nicastrin modulates presenilin-mediated notch/glp-1 signal transduction and betaAPP processing. Nature. 2000 Sep 7;407(6800):48–54. doi: 10.1038/35024009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hasegawa H, Sanjo N, Chen F, et al. Both the sequence and length of the C terminus of PEN-2 are critical for intermolecular interactions and function of presenilin complexes. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2004 Nov 5;279(45):46455–46463. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406289200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen F, Hasegawa H, Schmitt-Ulms G, et al. TMP21 is a presenilin complex component that modulates gamma-secretase but not epsilon-secretase activity. Nature. 2006 Apr 27;440(7088):1208–1212. doi: 10.1038/nature04667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saykin AJ, Shen L, Foroud TM, et al. Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative biomarkers as quantitative phenotypes: Genetics core aims, progress, and plans. Alzheimer's & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer's Association. 2010 May;6(3):265–273. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2010.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reitz C, Jun G, Naj A, et al. Variants in the ATP-binding cassette transporter (ABCA7), apolipoprotein E 4,and the risk of late-onset Alzheimer disease in African Americans. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2013 Apr 10;309(14):1483–1492. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.2973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pottier C, Hannequin D, Coutant S, et al. High frequency of potentially pathogenic SORL1 mutations in autosomal dominant early-onset Alzheimer disease. Molecular psychiatry. 2012 Sep;17(9):875–879. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.MacArthur DG, Manolio TA, Dimmock DP, et al. Guidelines for investigating causality of sequence variants in human disease. Nature. 2014 Apr 24;508(7497):469–476. doi: 10.1038/nature13127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vardarajan BN, Schaid D, Reitz C, et al. Inbreeding among Caribbean Hispanics from the Dominican Republic and the Effects on the Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease. Genetics in medicine : official journal of the American College of Medical Genetics. 2014 doi: 10.1038/gim.2014.161. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Petrucelli N, Daly MB, Feldman GL. Hereditary breast and ovarian cancer due to mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2. Genetics in medicine : official journal of the American College of Medical Genetics. 2010 May;12(5):245–259. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181d38f2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sierra M, Gonzalez-Aramburu I, Sanchez-Juan P, et al. High frequency and reduced penetrance of LRRK2 G2019S mutation among Parkinson's disease patients in Cantabria (Spain) Movement disorders : official journal of the Movement Disorder Society. 2011 Nov;26(13):2343–2346. doi: 10.1002/mds.23965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Caglayan S, Takagi-Niidome S, Liao F, et al. Lysosomal Sorting of Amyloid-β by the SORLA Receptor Is Impaired by a Familial Alzheimer’s Disease Mutation. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(223):223ra20. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]