Abstract

Background

Bone stress injuries are common in track and field athletes. Knowledge of risk factors and correlation of these to magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) grading could be helpful in determining recovery time.

Purpose

To examine the relationships between MRI grading of bone stress injury with clinical risk factors and time to return to sport in collegiate track and field athletes.

Study Design

Prospective cohort over 5 years.

Methods

Two hundred and eleven male and female collegiate track and field and cross-country athletes were followed prospectively through their competitive seasons. All athletes had a pre-participation history, physical exam, and anthropometric measurements obtained annually. An additional questionnaire was completed regarding nutritional behaviors, menstrual patterns and prior injuries, as well as a 3-day diet record. Dual energy X-ray absorptiometry was obtained at baseline and each year of participation in the study. Athletes with clinical evidence of bone stress injuries had plain radiographs. If radiographs were negative, MRI was obtained. Bone stress injuries were evaluated by two independent radiologists utilizing an MRI grading system. MRI grading and risk factors were evaluated to identify predictors of time to return to sport.

Results

Thirty-four (12 males, 22 females) of the 211 collegiate athletes sustained 61 bone stress injuries during the 5-year study period. The average prospective assessment for participants was 2.1 years. MRI grade and total body bone mineral density (BMD) emerged as significant and independent predictors of time to return to sport in the multiple regression model. Specifically, the higher the MRI grade, the longer the recovery time (p<0.002). Location of bone injury at predominantly trabecular sites of the femoral neck, pubic bone and sacrum (p<0.001), and lower total body BMD (p<0.029) independently predicted prolonged time to return to sport.

Conclusions

Higher MRI grade, lower BMD, and skeletal sites of predominant trabecular bone structure were independently associated with delayed recovery of bone stress injuries in track and field athletes. Knowledge of these risk factors, as well as nutritional and menstrual factors, can be clinically useful in determining time to return to sport.

Key Terms: Female athlete triad, MRI grading, bone stress injury, stress fracture

BACKGROUND

Bone stress injuries result from chronic repetitive training and can range from a stress reaction to a cortical fracture. These injuries, more common in certain populations of athletes, account for up to 10% of all injuries seen in sports medicine clinics 26, 38, 48. Prospective studies suggest an incidence of up to 21% in track and field athletes 9 and 31% in military recruits 39. Bone stress injuries are an important issue for which the diagnosis and management evolve as our understanding of the multifactorial processes and diagnostic tools develop.

According to Wolff's law, external mechanical forces induce adaptive changes in the internal and external architecture of bone 50. When the balance between formation and resorption is disturbed, bone weakens and becomes increasingly susceptible to injury. The development of a cortical fracture can occur with consistent stress 3, 28. Johnson and colleagues in their histological analysis of bone stress injuries by bone biopsies found that early discontinuation of repetitive stress prevented the progression to a fracture 28. Current understanding suggests that bone stress injuries not identified and managed appropriately can progress to a more serious fracture 18, 22, 23, 30, 31, 42, and preventive strategies, including identification and modification of risk factors, may help prevent the progression to a frank fracture 22, 31.

Historically, radiographs and radionuclide bone scans have been the standard diagnostic tools used to assess and diagnose bone stress injuries. Although standard radiographs may reveal bony changes associated with stress injuries, they often remain normal 10, 17, 45, 54. In addition to being affected by the time of onset of symptoms, radiographic abnormalities are also affected by the skeletal location of the bone stress injury 17. While radiographs are usually the first diagnostic test ordered, their sensitivity is only approximately 10% in the early stages of injury 34. If standard radiographs are negative in the presence of concerning clinical findings, they should be supplemented with diagnostic studies that have greater sensitivity for bone stress injury. Radionuclide bones scans can detect bone stress injuries as soon as two to eight days after symptoms are first noted 45. Roub and colleagues 45 and subsequently Chisin 14 and Zwas 54 developed a grading system of progressive stress injury using radioisotope findings, with a cortical fracture displaying more intense uptake. The use of bone scans as an independent diagnostic tool is, however, limited by low specificity and lack of visualization of a potential fracture line 19. Computed tomography (CT) is useful and specific when a fracture line exists, but this occurs at the late stage of a bone stress injury 18. Ultrasound has been used to assess bone stress injuries in track and field athletes with reported sensitivity of 81.9% and specificity of 66.6% compared to MRI 43, but further studies are needed to assess the use of ultrasound as a method of screening.

The application of magnetic resonance imaging 24 for the diagnosis of bone stress injuries allows for sensitivity comparable to, or greater than, scintigraphy and a non-ionizing method of detecting and localizing fracture lines 16. MRI is also highly specific and provides useful information about the extent of bone injury and damage to surrounding tissue 47. Even at early onset, MRI has the best combined specificity and sensitivity for bone stress injuries and is the recommended diagnostic imaging test to assess the spectrum of bone stress injury among symptomatic patients 10, 17, 21, 51.

The full spectrum of bone stress injury by MRI can be depicted as a periosteal or bone marrow edema pattern of high signal on T2-weighted and short-term inversion recovery (STIR) sequences, and low signal on T1-weighted sequences, with further injury progression demonstrated as a frank cortical fracture 4,17,18. Fredericson et al. described early bone stress injury on MRI often beginning with periosteal edema and, with worsening of the injury, progressing to include marrow edema. If untreated, the injury can further progress to an identifiable stress fracture 18. Knowledge of the clinical setting is imperative to the interpretation of the MR findings. Using fat-suppressed T2-weighted MRI sequences, Fredericson and colleagues clinically correlated this progression in a retrospective review of 33 tibial bone stress injuries and developed an MRI grading system based on the pattern of periosteal and marrow edema 18. Fredericson et al., in their retrospective study, found that their grading scale correlated with both the extent of clinical findings and time to full return to activity 18. In a retrospective review of 74 track and field athletes with bone stress injuries, Arendt et al. reported similar findings using a modified MRI grading scale that replaced fat-suppressed T2 sequences with short T1 inversion recovery (STIR) sequences 2. Yao and colleagues 51 in their retrospective study examining the prognostic value of MRI grading of stress injuries of bone in 24 patients concluded that the findings of a cortical signal intensity abnormality or a fracture line was of prognostic value, leading to a longer recovery time. However, there was otherwise no prognostic correlation with the bone stress injuries receiving lower MRI grades with recovery time 51. Beck and colleagues in their analysis of tibial bone stress injuries, in male and female active subjects 18–50 years of age, found a trend toward higher MRI grade and a longer recovery time, but this did not reach statistical significance. In this same study, radiographic, bone scan and CT severity of tibial stress injury were not related to time to healing7. MRI grading therefore provides a potentially standardized approach to the diagnosis and management of bone stress injuries and appears superior to other imaging modalities7.

To our knowledge, no prospective studies have correlated MRI grading of bone stress injuries at multiple skeletal sites with risk factors and time to return to full sport participation. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to prospectively assess MRI grading of bone stress injuries at various skeletal sites, and assess a correlation with risk factors and time to return to sport among male and female collegiate track and field athletes. The author’s hypothesis was that the higher grade bone stress injuries as assessed prospectively by MRI would be associated with prolonged recovery. It was also hypothesized that risk factors associated with the female athlete triad would be associated with prolonged recovery in female athletes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

There was a total of 211 male and female collegiate track and field and cross country athletes from a major Division I university that participated in the prospective study over a 5 year period between the fall of 1996 to the spring of 2001. Athletes on the cross country and track and field teams were asked to participate in the study each year at their pre-participation physical exam prior to the start of their season and were followed during the duration of the study period. There were 83 athletes on the roster year 1, 89 year 2, 103 year 3, 98 year 4 and 88 year 5. Athlete volunteers consented following appropriate IRB approval for human subject research. A self-reported questionnaire on demographic information and general background information (including previous bone injury history, detailed current and past menstrual history, history of disordered eating/eating disorders, exercise history, general health information and medications including oral contraceptive pill use) was administered annually by the athlete participant alone at the start of the cross-country and/or track and field season, in addition to the standard annual pre-participation physical exam questionnaire that is required at this institution. The questionnaire had not been previously validated. Three-day food diaries were obtained for each athlete participant. For assessment of disordered eating behaviors, data was used that was completed on the questionnaire and food diary by the athlete, and a physician interview along with a multidisciplinary assessment including evaluations by the team dietitian and a psychologist utilizing DSM IV criteria for eating disorders, and eating disorder not otherwise specified. Dual energy X-ray absorptiometry studies (DXA) were administered at baseline and annually for each subject.

Imaging Studies for Suspected Bone Stress Injuries

Athletes on the cross country and track and field teams were followed prospectively for occurrence of bone stress injury throughout their season and until the end of the study period. If an athlete presented with pain, he/she was initially evaluated by a certified athletic trainer and then referred to a team physician if a bone stress injury was suspected. Initial plain radiographs were obtained for the majority of suspected bone stress injuries and, if negative, an MRI was ordered or, in few instances, bone scintigraphy (Figure 1). Some athletes bypassed standard radiographs and underwent MRI as their initial study.

Figure 1.

Number of bone stress injuries incurred, diagnostic imaging utilized- and the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) grade results. §Three MRI images were not graded due to incomplete time to return to sport data.

Grading by MRI for a suspected bone stress injury in this study was performed independently by 2 fellowship-trained musculoskeletal radiologists (Table 1) using modified versions of the MRI grading scale described by Fredericson and colleagues for tibial bone stress injuries in 199518, and by Arendt et al. for bone stress injuries in athletes at all skeletal sites2, 4. In defining a Grade 1 injury, our grading scale used the presence of mild marrow edema on fat suppressed T2-weighted images (but not T1-weighted images) or periosteal edema. For Grade 2 bone stress injuries at our institution, moderate marrow edema on T2-weighted images (but not T1) or periosteal edema was used, and differed from Grade 1 in the degree of marrow or periosteal edema. Grade 3 bone stress injuries included the presence of severe marrow edema or periosteal edema on both T2-weighted images and T-1 weighted images (in the same location), but without a fracture line. Grade 4 bone stress injury was similar to Grade 3 in severity of marrow or periosteal edema, but included the presence of a fracture line on either T-1 or T-2 weighted images. Examples of the MRI imaging grading used for our study are illustrated in Figures 2–5. On few occasions only, there was disagreement in the MRI grading. In these instances, a consensus was reached between the two independent radiologists.

Table 1.

MRI grading scales for bone stress injuries

| MRI Grade | Fredericson et al. | Arendt et al. | Nattiv et al. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mild to moderate periosteal edema on T2; normal marrow on T1 and T2 | Positive signal change on STIR | Mild marrow or periosteal edema on T2*, T1 normal** |

| 2 | Moderate to severe periosteal edema on T2; marrow edema on T2 not T1 | Positive STIR plus positive T2 | Moderate marrow or periosteal edema plus positive T2; T1 normal |

| 3 | Moderate to severe periosteal edema on T2; marrow edema on T2 and T1 | Positive STIR plus positive T2 and T1 | Severe marrow or periosteal edema on T2 and T1 |

| 4 | Moderate to severe periosteal edema on T2; marrow edema on T2 and T1; Fracture line present | Positive injury line (fracture) on T1 or T2; injury | Severe marrow or periosteal edema on T2 and T1 plus fracture line on Tl or T2 |

Adapted from Table 1 of Fredericson AJSM 1995; Table 3 of the Arendt 2003 AJSM

Nattiv et al – Note that periosteal edema is not a necessary criteria for grade 1 or any MRI grade bone stress injury;

Radiographs often negative at all grades – may be normal or periosteal reaction may be evident; grade 4 may or may not have evidence of bone injury on radiographs

Figure 2.

MRI grade 1 bone stress injury of tibia. Arrow points to mild periosteal edema depicted in this axial image of the posteromedial tibia. MRI grade 1 includes mild marrow or periosteal edema on T2-weighted images (but not T1).

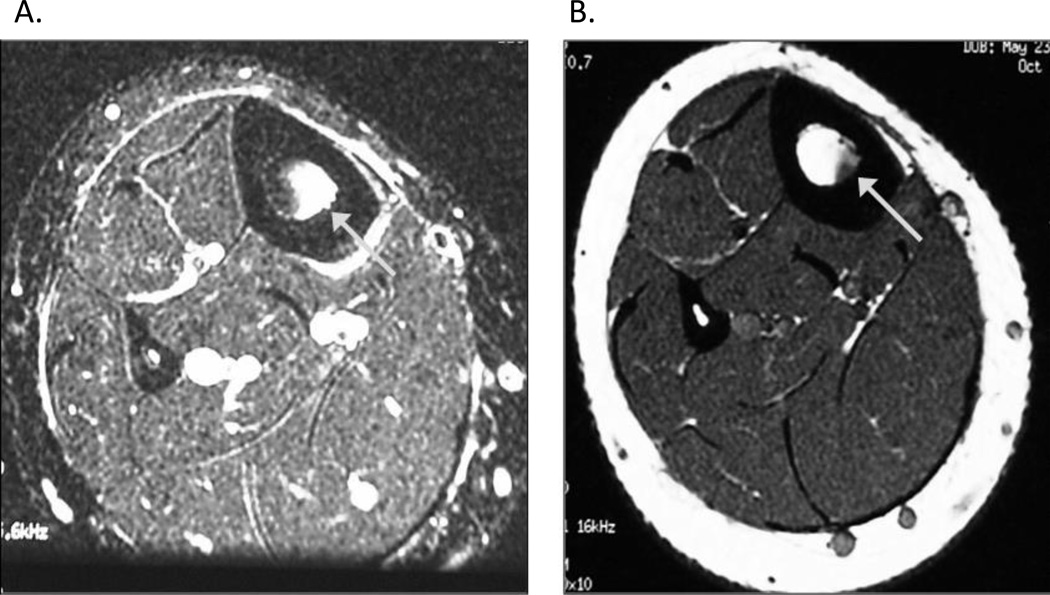

Figure 5.

A and B MRI grade 4 bone stress injury of femoral neck Arrow in 5A points to severe marrow edema on T2-weighted image plus a fracture line. Arrow in 5B points to severe marrow edema on corresponding T1-weighted image. MRI grade 4 bone stress injury includes severe marrow or periosteal edema on T2 and T1-weighted images plus a fracture line.

Anthropometric Measurements

The athletes’ height and weight were measured and BMI calculated at baseline and annually.

Bone Density Measurements

Dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) studies were obtained to measure bone mineral density (BMD) using a Hologic QDR 4500A scanner. Baseline and follow up testing was obtained on the same DXA scanner by a single certified densitometry technician. The following skeletal sites were measured on each subject scanned: Lumbar spine L1-L4, non-dominant total hip and femoral neck, total body, non-dominant forearm (1/3 radius) and tibia. Percent body fat and body composition was also obtained on each subject by DXA.

Weight-bearing and Full Return to Sport

For each athlete with a bone stress injury, the details of days and/or weeks of non-weight-bearing, partial weight-bearing, full weight bearing and full return to sport were documented in the athlete’s chart by the team physician in the athletic training room, and supplemented by the certified athletic trainer when needed. For athletes sustaining concurrent bone stress injuries in the same skeletal site (same side or opposite side), the higher MRI grade injury was used for time to return to sport. The same team physician evaluated each athlete participant in the study when a bone stress injury was suspected and/or identified, and for the majority of the athlete’s follow up visits. The average follow up visit interval was every 2 weeks from diagnosis of bone stress injury to full return to sport.

Site of Injury

The skeletal site of injury was identified. Bone stress injuries occurring in trabecular vs cortical bone sites were assessed for time to return to sport and MRI grade. Trabecular bone sites included the femoral neck, sacrum and pubic bones. Cortical bone sites included tibia, fibula, metatarsals, navicular and great toe sesamoids. Bone stress injuries at more than one site concurrently were recorded.

Statistical Analysis

Frequencies and means (mean ± SEM) were calculated to identify characteristics and sample distribution (e.g. gender, ethnicity, track & field event, height, weight, menstrual status, MRI grade) at baseline and time of injury. ANOVA and ANCOVA with Bonferroni correction assessed differences in descriptive traits, bone mass, and time to full return to sport among groups based on MRI grade and fracture location (trabecular vs cortical sites). Chi-square analyses evaluated differences in proportions between groups. Pearson correlations were run to identify factors significantly associated with time to full return to sport. Multiple linear regression assessed variables that significantly contributed to the prediction of time to full return to sport. All analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 16.0.

A power analysis was performed prior to the initiation of the study (using PASS60 by Dr. Jerry L. Hintz, 1996, Kaysville, Utah 84037) and based on a sample size of 80 or 40 athlete participants depending on the possible need to stratify data by gender. It was found that for a linear regression analysis with 80 subjects, the power would be at least 84% for detecting covariates that improve the R-square by 0.10 or more. For an analysis based on 40 participants, the power would be at least 74% for detecting increases in the R-square of 0.15 or more.

RESULTS

Thirty-four (12 males, 22 females) of the 211 NCAA track and field and cross-country athletes sustained 61 bone stress injuries during the 5-year study period. Mean age at time of injury was 20.5 ± 0.2 years. All athlete participants with bone stress injuries continued their participation from diagnosis through full return to sport. Mean years of athlete’s prospective participation in the study was 2.1 years. Fifty-six percent of the athletes were Caucasian, 29% African American, and 12% Hispanic. Over half (59%) of the athletes that sustained a bone stress injury were cross-country runners who trained and competed in mid-distance and/or long-distance events. Twenty-three percent of the female athletes reported oligomenorrhea and/or amenorrhea during the 5-year study period. Physical and descriptive characteristics of the 34 athletes who sustained bone stress injuries are reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Physical and descriptive characteristics of athletes that sustained a bone stress injury during the 5-year prospective study

| Female (N=22) | Male (N= 12) | |

|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | ||

| White | 12 (55%) | 7 (58%) |

| Black | 8 (36%) | 2 (17%) |

| Hispanic | 2 (9%) | 2 (17%) |

| Asian | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Event | ||

| Distance | 13 (59%) | 7 (58%) |

| Sprints | 5 (23%) | 2 (17%) |

| Jumps | 4 (18%) | 3 (25%) |

| Height (cm) | 166.9 ± 1.3 | 178.4 ± 1.9 |

| Weight (kg) | 57.7 ± 1.6 | 67.5 ± 2.0 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 20.5 ± 0.3 | 21.1 ± 0.4 |

| Lean mass (kg) | 44.3 ± 0.8 | 58.5 ± 1.2 |

| Body fat (%) | 17.2 ± 0.8 | 12.1 ± 1.1 |

| Menstrual Status | ||

| Regular | 8 (36%) | --- |

| Regular/O/A | 6 (27%) | --- |

| O/A | 5 (23%) | --- |

| DE History (%) | 4 (18%) | 0 (0%) |

| Fracture History (%) | 12 (55%) | 4 (36%) |

Skeletal site of bone stress injury and frequency of injuries are reported in Table 3. The tibia (51% of injuries) and metatarsals (21% of injuries) were the most frequent sites injured. Seventeen athletes (50%) sustained multiple bone stress injuries (11, 2, and 4 athletes had two, three, and four fractures, respectively) during the study period. Of the athletes with multiple bone stress injuries, 11 (65%) had more than one concurrently.

Table 3.

Frequency of injury site and MRI grade among male and female athletes

| Frequency |

Total | Percent | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female (N=22) | Male (N= 11) | |||

| Injury site | ||||

| Tibia | ||||

| Anterior | 2 | 1 | 3 | |

| Posteromedial | 18 | 10 | 28 | |

| Total | 20 | 11 | 31 | 51 |

| Metatarsal | ||||

| 2nd | 2 | 1 | 3 | |

| 3rd | 3 | 3 | 6 | |

| 4th | 2 | 1 | 3 | |

| 5th | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Total | 7 | 6 | 13 | 21 |

| Femur | ||||

| Femoral neck | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| Femoral shaft | 2 | 0 | 2 | |

| Total | 3 | 1 | 4 | 7 |

| Sacrum | 3 | 0 | 3 | 5 |

| Sesamoid | ||||

| Medial | 2 | 1 | 3 | |

| Lateral | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | 2 | 1 | 3 | 5 |

| Fibula | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| Pubic | 0 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| Navicular | 2 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| Total | 61 | 100 | ||

| MRI Grade | ||||

| Grade 1 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 9 |

| Grade 2 | 13 | 8 | 21 | 49 |

| Grade 3 | 10 | 2 | 12 | 28 |

| Grade 4 | 6 | 0 | 6 | 14 |

| Total | 43 | 100 | ||

Figure 1 outlines the number of injuries incurred, imaging modality used, and MRI grade distribution. Fifty-six athletes with symptoms consistent with a bone stress injury underwent standard radiographs of the injured site, while five were directed to MRI without radiographs. The majority of athletes with bone stress injuries, 44 of 56 (78.6%), had normal plain radiographs at the time of initial assessment, with twelve of the 56 (21.4%) injuries diagnosed with plain radiographs alone (Table 4). The skeletal sites in which bone stress injuries were most commonly seen on plain radiographs were in the tibia (47.6%) and metatarsal bones (46.2%). Of the remaining injuries that required a further diagnostic test, 3 (6.8%) underwent bone scintigraphy, and 41 (93.2%) MRI (Figure 1). Of the 46 injuries evaluated by MRI, the frequency of each grade was: Grade 1= 4; Grade 2= 21; Grade 3= 12; Grade 4= 6. Three MRI images were not graded because of missing return to sport data. The frequency of each grade according to gender is reported in Table 3. Females compared to males trended toward a higher MRI grade 2.6 ± 0.1 vs. 2.1 ± 0.3, p= 0.09. Over half (58.1%) of all MRI images were evaluated as Grade 1 or Grade 2 bone stress injuries. Only 14.0% of all injuries evaluated by MRI were Grade 4 (exhibiting a visible fracture line).

Table 4.

Bone stress injuries diagnosed by plain radiographs

| N | Percent | |

|---|---|---|

| Injury Site | ||

| Tibia | 10/21 | 47.6 |

| Metatarsals | 6/13 | 46.2 |

| Sesamoid | 1/3 | 33.3 |

| Fibula | 1/3 | 33.3 |

| Femur1 | 0/4 | 0 |

| Sacrum1 | 0/3 | 0 |

| Pubic1 | 0/2 | 0 |

| Navicular | 0/2 | 0 |

Sites high in trabecular bone

Characteristics among athletes with a lower (Grade 1 or 2) compared to higher (Grade 3 or 4) MRI grade injury are presented in Table 5. Athletes with a higher MRI grade injury exhibited a lower BMD at the total hip (p<0.050) and radius (p<0.047). Among the female athletes, MRI grade was significantly higher among those classified with oligo/amenorrhea (OA) compared to eumenorrhea (RR), 3.5 ± 0.3 vs. 2.5 ± 0.2, p= 0.009.

Table 5.

Characteristics among athletes with lower (Grade 1 & 2) compared to higher (Grade 3 & 4) grade bone stress injuries

| Grade 1 & 2 (N = 25) |

Grade 3 & 4 (N= 18) |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Differences | |||

| Age (y) | 20.7 ± 0.3 | 20.2 ± 0.3 | NS |

| Height (cm)§ | 168.9 ± 1.0 | 169.8 ± 1.2 | NS |

| Weight (kg)§ | 60.2 ± 1.1 | 59.0 ± 1.4 | NS |

| BMI (kg/m2)§ | 21.1 ± 0.3 | 20.2 ± 0.3 | 0.068 |

| Body fat (%)§ | 14.5 ± 0.9 | 17.4 ± 1.2 | 0.067 |

| Lean mass (kg)§ | 48.6 ± 0.9 | 46.9 ± 1.1 | NS |

| Bone mass (g/cm2)§ | |||

| Spine | 1.049 ± 0.032 | 0.969 ± 0.037 | NS |

| Femoral neck | 0.922 ± 0.023 | 0.882 ± 0.027 | NS |

| Total hip | 1.104 ± 0.029 | 1.015 ± 0.033 | 0.050 |

| Radius | 0.450 ± 0.011 | 0.413 ± 0.014 | 0.047 |

| Tibia | 1.013 ± 0.017 | 1.038 ± 0.022 | NS |

| Total body | 1.236 ± 0.022 | 1.184 ± 0.028 | NS |

| Percent | |||

| Female (%) | 64.0% | 88.9% | 0.065 |

| Caucasian (%) | 56% | 83% | 0.059 |

| Distance Event (%) | 60.0% | 72.2% | NS |

| Oligo/Amenorrhea (%) | 0% | 40.0% | 0.010 |

| Disordered Eating (%) | 12.0% | 22.2% | NS |

| Fracture Hx (%) | 64.0% | 55.6% | NS |

Adjusted for gender

Mean differences assessed by ANOVA/ANCOVA. Chi-Square tests assessed percentages between groups. α= 0.05

A significantly higher percent of athletes with trabecular bone injuries (those in the femoral neck, pubic bone or sacrum) compared to cortical bone sites ran middle and/or long-distance, exhibited disordered eating, and oligo/amenorrhea (p=0.005, p=0.04, p=0.005 respectively) (Table 6). Those with bone stress injuries at trabecular sites had significantly lower bone mass at the lumbar spine, femoral neck, and total hip (p<0.001) (Table 6). Time to full return to sport was significantly longer for those with a bone stress injury at trabecular vs cortical site (p<0.001), even after adjusting for MRI grade (p=0.01) (Table 6).

Table 6.

Descriptive characteristics. MRI grade, and time to return to sport among athletes with bone stress injuries at the cortical and trabecular sites

| Cortical (N=36) |

Trabecular (N= 7) |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SEM | |||

| Age | 20.5 ± 0.2 | 20.4 ± 0.5 | NS |

| BMI | 20.8 ± 0.2 | 20.1 ± 0.9 | NS |

| MRI Grade | 2.3 ± 0.1 | 3.1 ± 0.4 | 0.02 |

| BMD | |||

| Lumbar Spine | 1.058 ± 0.021 | 0.828 ± 0.048 | <0.001 |

| Femoral Neck | 0.933 ± 0.015 | 0.785 ± 0.042 | <0.001 |

| Total Hip | 1.101 ± 0.021 | 0.913 ± 0.040 | <0.001 |

| Radius | 0.442 ± 0.009 | 0.399 ± 0.033 | 0.10 |

| Tibia | 1.018 ± 0.018 | 1.049 ± 0.018 | NS |

| Total Body | 1.223 ± 0.017 | 1.147 ± 0.054 | 0.09 |

| Return to sport (weeks) | 14.9 ± 1.6 | 31.1 ± 6.4 | <0.001 |

| Adj. MRI grade | 15.8 ± 1.5 | 26.7 ± 3.8 | 0.01 |

| Percent | |||

| Female (%) | 77.8% | 57.1% | NS |

| Caucasian (%) | 61.1% | 100.0% | 0.045 |

| Distance Event (%) | 58.3% | 100.0% | 0.005 |

| Oligo/Amenorrhea (%) (females) | 12.5% | 75.0% | 0.005 |

| Disordered Eating (%) | 11.1% | 42.9% | 0.04 |

| Fracture Hx (%) | 69.4% | 14.3% | 0.006 |

Data presented are for those athletes with MRI data

Trabecular fractures include those of the sacrum, pubic, and femoral neck

Mean differences assessed by Independent t-test and ANCOVA. Chi- Square tests assessed percentages between groups. α= 0.05

Weeks to full return to sport for Grade 4 bone stress injuries (31.7 ± 3.7 weeks) were significantly higher compared to Grade 3 (18.8 ± 2.9 weeks, p=0.055), Grade 2 (13.5 ± 2.1 weeks, p=0.001) and Grade 1 injuries (11.4 ± 4.5 weeks, p=0.008). Weeks for full return to sport for Grade 3 and 4 bone stress injuries were significantly higher than Grade 1 and 2 injuries (23.6 ± 2.4 weeks vs 13.1 ± 2.0 weeks respectively, p=0.002) (Figure 6). Among grade 3 & 4 injuries, time to return to sport was significantly longer for those at bone sites high in trabecular vs. cortical bone (38.1 ± 6.4 vs. 18.8 ± 2.1 weeks, p= 0.005). Among Grades 1 & 2 injuries, there was no difference in time to return to sport between injuries at bone sites high in trabecular vs. cortical bone (17.1 ± 9.1 vs. 12.7 ± 1.6, p= 0.75).

Figure 6.

Time to full return to sport (weeks) for injuries evaluated using MRI (N= 43), comparison between grades 1 & 2 (N= 25) vs. grades 3 & 4 (N= 18). aGrades 3 & 4 significantly longer than grade 1 & 2, (23.6 ± 2.4 vs. 13.1 ± 2.0 weeks, respectively, p= 0.002, Independent t-tests).

Time to full return to sport was longer for athletes who were Caucasian (20.7 ± 2.0, vs. 11.6 ± 2.7 weeks, p<0.05), ran mid/long-distance (20.0 ± 2.2 vs. 13.4 ± 2.7 weeks, p= 0.07), and were categorized with disordered eating (31.3 ± 4.3 vs. 15.4 ± 1.7 weeks, p<0.005). Fracture history, menstrual status, age at menarche, and gender were not significantly associated with time to return to sport. Pearson correlations identified factors that were positively (MRI grade, r= 0.57; muscle edema, r= 0.43; presence of a fracture line, r= 0.56; p<0.05) and negatively (lumbar spine BMD, r= −0.54; femoral neck BMD, r= −0.54; total hip BMD, r= −0.59; radius BMD, r= −0.51; total body BMD, r= −0.51; BMI, r= −0.51; age at menarche, r= 0.48; p<0.05) correlated with time to full return to sport.

The multiple linear regression analysis indicated that MRI grade and total body BMD emerged as significant independent predictors of time to full return to sport among the collegiate athletes (Table 7). The trabecular vs cortical bone site was also an independent predictor that trended toward significance (p=0.063). The model including these three factors and body mass index accounted for 68% (adj. R2= 0.68) of the variation in time to return to sport (Table 7). MRI grade and trabecular bone sites were positive predictors, indicating that injuries classified with a higher MRI grade or in the femoral neck, sacrum or pubic bone significantly increase time to return to sport. Total body BMD emerged as a significant negative predictor, indicating a protective effect of BMD on time to full return to sport.

Table 7.

Multiple regression model of variables contributing to the prediction of time to full return to sport among bone stress injuries with MRI grade (N=43)1

| Un-Stand B (Error) | Stand B | 95% CI | P-value | R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 0.68 | ||||

| MRI grade | 6.8 (2.1) | 0.44 | (2.5, 11.1) | 0.004 | |

| Trabecular vs. Cortical | 8.5 (4.3) | 0.26 | (−0.5, 17.5) | 0.063 | |

| Total body BMD (g/cm2) | −40.7 (17.4) | −0.35 | (−77.0, −4.3) | 0.030 | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | −0.90 (1.2) | −0.10 | (−3.5, 1.7) | 0.476 |

For injuries evaluated using MRI and with complete time to return to sport data

DISCUSSION

Although retrospective studies have supported the importance of MRI evaluation and grading of bone stress injuries 2, 18, this study serves as the first large, prospective analysis of MRI grading, its correlation with risk factors, and association with time to return to sport. Our primary finding was that MRI grade and total body bone density emerged as significant and independent predictors of time to full return to sport. This clinically relevant observation and evidence-based model can potentially be used to help physicians guide athletes in their recovery and rehabilitation. In addition, these findings suggest that optimizing bone mass may not only reduce risk of sustaining a stress injury to bone, but also contribute to improved healing potential and reduced recovery time. Further studies would be needed however to assess this hypothesis.

Early diagnosis of bone stress injuries can aid in their effective management and treatment, particularly with use of MR imaging. In a recent prospective comparison of imaging modalities in 42 athletes with a clinically suspected tibial stress injury and negative radiographs, the sensitivity of MRI, CT and radionuclide bone scan were 88%, 42%, and 74%, respectively. 21 MRI was also highly specific, equaling CT at 100% 21. In the current study, 49% (21/43) of the MRI graded bone stress injuries were Grade 2 and only 14% (6/43) were actual stress fractures (Grade 4, with visible fracture line) (Figure 1), indicating that with use of MRI, bone stress injuries can be identified before a fracture occurs and, thus, facilitate treatment and recovery.

Fredericson and colleagues previously identified an MRI grading scale for tibial bone stress injuries based on a pattern of bone marrow and periosteal edema 18. Fredericson’s grading scale correlated with both the extent of clinical findings and time to full return to activity for bone stress injuries of the tibia 18. Arendt et al. also performed a retrospective study using a similar grading scale and further confirmed correlation between MRI grade and full return to sport 2. Our MRI grading scale differed from Fredericson’s 18 in that periosteal edema was often, but not always, present and therefore not a necessary feature in the diagnosis of a bone stress injury. Muscle edema was often associated with higher MRI grade injuries, but was also not a necessary criteria. A comparison of the MRI grading scales can be found in Table 1. Yao and colleagues in their retrospective study of MRI grading and recovery time, also found that periosteal edema was not always present, and found no association with periosteal edema and a quicker return to sport 51

Of note is that in our study, radiographs were negative the majority of the time (78.6%) in initial assessment of bone stress injury, regardless of the injury grade. Contrary to Arendt’s description of a periosteal reaction present on plain radiographs in bone injuries receiving MRI Grades 3 and 4 2, we found that although a periosteal reaction may be present, the plain radiographs are usually negative even at the higher MRI grades.

Using our grading scale prospectively, time to full return to sport was positively correlated with MRI grade (r= 0.6, p<0.05). From the multiple regression model for every one unit increase in MRI grade, time to full return to sport increased by approximately 48 days (p = 0.002). Also, with a mean recovery time of approximately 8 months, time to full return to sport for Grade 4 injuries was significantly longer compared to all other grades (Figure 6). Therefore, when a bone stress injury has progressed to the point where there is cortical disruption (fracture) noted on the MRI (Grade 4 bone stress injury), it considerably disrupts the athletes’ ability to train and compete and return to sport is significantly delayed. These findings are consistent with retrospective studies by Arendt et al. 2 and Fredericson et al 18. Among collegiate athletes, prolonged injury and limited training contributes to an array of consequences, including muscle loss, aerobic deconditioning, and significant psychological distress 46 that may continue to affect their remaining athletic career. Therefore, it appears prudent to employ methods for diagnosing bone stress injury at earliest onset. These findings provide support for the utility of MRI and the MRI grading scale to identify the earliest signs of stress injury to bone and, thus, allow for improved treatment outcomes.

In addition to MRI grade, total body BMD and bone stress injuries of trabecular bone structure (specifically in the femoral neck, pubic bone and sacrum) were the most important independent predictors of return to sport in our study. These findings suggest that when a bone stress injury is suspected and/or identified, management of the injury can be more accurately determined when the clinician is provided with information about the severity of injury as determined by MRI grading of the bone stress injury, as well as the location of the injury (trabecular vs cortical sites). Obtaining a DXA provides valuable prognostic information that can help predict recovery time. When these independent predictors were combined with BMI, we were able to account for more than 68% of the variation in time to return to sport. Other prospective studies in female track and field and cross-country athletes have found that lower BMD is associated with an increased risk for stress fracture 9, 32, but to our knowledge, it has not been previously reported that lower BMD is predictive of return to sport outcomes (longer recovery time) in athletes with bone stress injuries. With future research, this type of a model can be further developed and used as a tool to guide clinicians in their management of patients’ return to sport activities.

Similar to prior reports, the most frequent skeletal sites for bone stress injuries were the tibia (51%) and metatarsals (21%) 2, 9, 29, 38, 40 (Table 3). Distance runners sustained a higher percentage (59%) of injuries compared to athletes participating in other sprint and field events. It has been previously noted that distance runners exhibit high rates of stress injury to bone 2, 12, 40. Arendt et al. reported that cross-country runners compared to all track and field athletes had the highest yearly incidence of bone stress injury over a 10-year period (6.4% vs. 1.6% and 3.9% vs. 0.8% incidence rates, among male and female participants, respectively) 2. Matheson and colleagues, in their evaluation of 320 stress injuries in a sports medicine clinic, reported the highest number of injuries among long-distance runners 38. Additionally, stress fracture incidence has been associated with an increase in long-distance running training among female military recruits 1, 44. However, in contrast to the current study, Bennell et. al 9 who prospectively evaluated male and female track and field athletes for 1-year did not report a higher prevalence of bone stress injury among athletes running long distance events, although the distance runners sustained more long bone and pelvic fractures 9. The difference in the study duration and diagnostic imaging used (CT vs. MRI) to define bone stress injury between Bennell et al. and the current study may account for the discordant results 9. Long-distance runners are at higher risk of sustaining stress injury to bone as a result of their high training volume (and thus increased exposure of bone to repeated stress), potential biomechanical imbalances (such as pes planus, leg-length discrepancy, or increased Q-angle) 19, 52, and risk of under-nutrition 5, 6, 20, 36.

Of the 34 athletes with bone stress injuries in this study, 22 (65%) were female (Table 2), suggesting that women in the study were at higher risk. Multiple prior studies have reported similar findings 2, 13, 29, 53. In a larger study of 914 athletes, Johnson et al. reported an overall incidence of stress fractures of 2% per year in men compared to 7% per year in women 29. Furthermore, females incurred higher-grade bone stress injuries than their male counterparts (Table 3). Approximately half of female bone stress injuries were Grade 3 and all of the Grade 4 injuries were sustained by women (Table 3). This greater severity of injury among women may be due to anatomic factors, such as smaller body size in women, physiologic differences in women compared to men, psychological or social factors, and/or factors associated with the female athlete triad 8, 9, 32, 41.

The inverse association found between total body bone mass and recovery, are consistent with previous reports of post-menopausal osteoporotic women and estrogen-depleted osteoporotic animals exhibiting delayed bone healing. Additionally, a study that utilized in vivo micro-CT analysis to evaluate bone healing, reported impaired neurovascularization, bone formation, bone remodeling, and a lower restoration of mechanical properties in OVX-induced osteoporotic mice compared to Sham-operated controls 25. It is also important to note that athletes with higher MRI grade injuries had significantly lower bone mass at the total hip and radius, suggesting that lower bone mass may be associated with the development of more advanced stress injuries to bone. Together, these findings underscore the importance of optimizing bone mass to facilitate the processes of healing from a stress injury to bone. While genetic factors significantly influence bone mass and strength, regular bone-building exercise and adequate nutrition maximize the genetic potential to accrue and mineralize bone.

It is established that functional hypothalamic amenorrhea (FHA) in athletes results from insufficient energy intake in comparison to the calories expended from exercise activity 41. A chronic period of under-nutrition leads to the suppression of metabolic processes and a reduction in various hormone levels that affect bone turnover 27, 49. Lower estradiol levels, as seen in FHA, negatively affect bone mass through a variety of mechanisms, including reduced calcium absorption, increased processes of bone resorption, and suppressed bone formation. Among the women in the current study, oligo/amenorrhea was associated with sustaining a higher-grade bone stress injury. This was not an unexpected finding, particularly since the oligo/amenorrheic athletes in the study had significantly lower bone mass. Furthermore, oligo/amenorrhea did not emerge as a significant predictor of time to return to sport in the multiple regression analysis. Though not significant in the regression model, oligo/amenorrhea may have indirectly influenced athlete’s recovery time and healing potential due to its 1) relationship with the development of a higher MRI grade injury and 2) association with lower bone mass. Furthermore, menstrual irregularity was noted to be present in 75% of all females with injuries at trabecular bone sites and only 12.5% of the cortical bone sites (Table 6). Thus, functional hypothalamic menstrual disturbances may predispose females to higher MRI grade bone stress injuries at skeletal sites of predominant trabecular bone.

The important clinical finding that trabecular bone stress injuries (including femoral neck, sacral and pubic bone stress injuries) were associated with a significantly longer time to full return to sport participation than cortical bone stress injuries, should help guide clinicians to utilize a more gradual progression of activity and cross training in athletes with injuries in these skeletal sites, while addressing important nutritional, hormonal and bone health preventive measures. Marx and colleagues in their retrospective, cross-sectional study found that female athletes with stress fractures in regions of mostly trabecular bone had lower bone density than those with stress injuries of cortical bone sites 37. In a biomechanical laboratory study assessing the fatigue properties of trabecular and cortical bone tissue of the human tibia, Choi and colleagues 15 found that trabecular specimens had significantly lower moduli and lower fatigue strength than cortical specimens. Different fracture and damage patterns were identified between these two types of bone based on mechanical and qualitative analyses. These findings reinforce the important role that optimal bone health plays in the prevention and management of bone stress injuries and has significant clinical implications.

High risk stress fractures as defined by Boden and colleagues 11 represent a subset of bone stress injuries that have a propensity to progress to complete fracture, delayed union or nonunion. Specific sites for these type of stress injuries include the femoral neck (tension-side), anterior tibia, medial malleolus, navicular, 5th metatarsal (proximal diaphysis, distal to tuberosity), talus, patella, and great toe sesamoids11. In our study, there were no statistically significant differences with regard to MRI grading patterns or time to return to sport with these specific high risk injuries grouped together, although this was likely due to too few bone stress injuries at these sites in this population of athletes. Progression of bone stress injury into a complete fracture at these higher risk skeletal sites can have a devastating outcome (e.g. a complete hip fracture), can be career ending, and/or result in surgical fixation if not managed and treated appropriately.

All of the collegiate athletes assessed in this study had clinical symptoms that correlated with their bone stress injuries on MRI. However, it should be noted that asymptomatic Grade 1 bone stress injuries have been found to be common in elite military recruits 33, and asymptomatic bone stress injuries have been documented in runners, with no known clinical significance 10, 35. These studies emphasize the importance of correlating MRI findings with clinical symptoms before making diagnostic and treatment decisions.

This study was limited by the relatively small sample size of athletes with injuries. Additionally, self-reporting of certain data such as demographic information and general background information (previous bone injury history, detailed menstrual history of current and past menstrual patterns, nutritional history, history of disordered eating/eating disorders, exercise history, general health history, medications including oral contraceptive pill use) was in some instances, subject to participants’ memory, and therefore may be limiting due to potentially inadequate or inaccurate reporting. Lastly, baseline BMI and BMD was used for the statistical analyses, rather than at the time of an identified injury.

The protocol for the study did not include use of high resolution CT, in addition to MRI, for assessment of the bone stress injuries receiving MRI Grades 1–3, to further assess if a fracture was present. This would have added additional cost and radiation exposure, and was not felt to be clinically indicated. In addition, other than for femoral neck and tarsal navicular bone stress fractures (higher grade injuries at higher risk sites), and additional trabecular bone sites of the sacrum and pubic bone, MRI scans were generally not repeated during healing if the athlete was pain free and improving clinically. Of the MRI studies that were repeated prior to full return to sport, there was no evidence of a higher MRI grade bone injury or progression of a fracture line. Although the study took place over a decade ago, it should be noted that MRI technology has not significantly advanced for musculoskeletal imaging with regard to assessment of bone stress injuries.

CONCLUSIONS

In this prospective study, we found that MRI grading severity, total body BMD, and location of bone injury (trabecular vs. cortical bone) independently predicted time to full return to sport. A notable difference in our MRI grading scale from that of Fredericson’s 18 is that periosteal edema was not a necessary criteria for any grade injury and was not associated with return to sport. We also identified nutritional and menstrual status as important factors affecting MRI grading severity, location of bone stress injury, as well as the athlete’s BMD. These results support the important contribution of the female athlete triad risk factors 41 and relationship to bone stress injury and recovery.

In conclusion, when a bone stress injury is suspected and/or identified, we recommend utilizing MR imaging and an evidence-based grading scale, measuring BMD, identifying the injury site as trabecular or cortical bone, and obtaining a careful history of nutritional and menstrual status. With this information, a clinician can better predict time to return to sport participation and ultimately improve management of bone stress injuries. Further research is warranted to develop clinical algorithms of risk and/or risk stratification scores that may help clinicians with decisions involving athlete clearance and return to play that may lead to improved bone health and decrease the incidence of bone stress injuries, especially in the high risk athlete.

Figure 3.

MRI grade 2 bone stress injury of tibia. Arrow points to moderate marrow edema on T2-weighted image. MRI grade 2 includes moderate marrow or periosteal edema on T2-weighted image (but not T1).

Figure 4.

A and B MRI grade 3 bone stress injury of tibia. Arrow in 4A points to severe marrow edema on T2-weighted image, and arrow on 4B illustrates corresponding marrow edema on the T1-weighted image. MRI grade 3 bone stress injury includes severe marrow edema or periosteal edema on T2 and T1-weighted images.

Figure 7.

Time to full return to sport (weeks) for injuries evaluated using MRI (N=43), comparison between grades 1 & 2 (N=25) vs. grades 3 & 4 (N=18) for injuries occurring at the cortical (N= 36) and trabecular (N= 7) bone sites. aGrades 3 & 4 trabecular bone stress injuries significantly longer than grades 3 & 4 cortical bone stress injuries (38.1 ± 6.4 vs. 18.8 ± 2.1 weeks. p= 0.005). No differences observed between grades 1 & 2 trabecular bone stress injuries vs. grades 1 & 2 cortical bone stress injuries, p=0.75. Independent t-tests).

What is known about the subject

Retrospective studies have supported the importance and use of MRI evaluation in the grading of bone stress injuries in athletes and association with return to sport. However, MRI grading and correlation with important clinical risk factors and time to return to sport have not been evaluated prospectively in the athlete population.

What this study adds to existing knowledge

This study serves as the first large, prospective analysis of MRI grading, its correlation with risk factors, and association with time to return to sport. Our primary finding was that severity of bone stress injury as defined by MRI grade, as well as lower total body bone density served as significant and independent predictors associated with prolonged time to full return to sport in collegiate track and field athletes. This clinically-relevant observation and evidence-based model can potentially be used to help physicians guide athletes in their recovery and rehabilitation. In addition, these findings provide novel evidence to suggest that optimizing bone mass may not only reduce risk of sustaining a stress injury to bone, but also contribute to improved healing potential and reduced recovery time.

Acknowledgments

General Clinical Research Center (grant #UL1RR033176) and a grant from the United States Olympic Committee Sport Science and Technology, in conjunction with USA Track and Field.

Footnotes

Investigation performed at the University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California

One or more of the authors has declared the following potential conflict of interest or source of funding: The funding for the study was from the UCLA

REFERENCES

- 1.Almeida SA, Trone DW, Leone DM, Shaffer RA, Patheal SL, Long K. Gender differences in musculoskeletal injury rates: a function of symptom reporting? Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1999 Dec;31(12):1807–1812. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199912000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arendt E, Agel J, Heikes C, Griffiths H. Stress injuries to bone in college athletes: a retrospective review of experience at a single institution. Am J Sports Med. 2003 Nov-Dec;31(6):959–968. doi: 10.1177/03635465030310063601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arendt EA. Stress fractures and the female athlete. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000 Mar;(372):131–138. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200003000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arendt EA, Griffiths HJ. The use of MR imaging in the assessment and clinical management of stress reactions of bone in high-performance athletes. Clin Sports Med. 1997 Apr;16(2):291–306. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5919(05)70023-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barrack MT, Rauh MJ, Nichols JF. Cross-sectional evidence of suppressed bone mineral accrual among female adolescent runners. J Bone Miner Res. 2010 Aug;25(8):1850–1857. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barrack MT, Van Loan MD, Rauh MJ, Nichols JF. Physiologic and behavioral indicators of energy deficiency in female adolescent runners with elevated bone turnover. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010 Sep;92(3):652–659. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beck BR, Bergman AG, Miner M, et al. Tibial Stress Injury: Relationship of Radiographic, Nuclear Medicine Bone Scanning, MR Imaging, and CT Severity Grades to Clinical Severity and Time to Healing. Radiology. 2012 Jun;263(3):811–818. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12102426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bennell K, Matheson G, Meeuwisse W, Brukner P. Risk factors for stress fractures. Sports Med. 1999 Aug;28(2):91–122. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199928020-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bennell KL, Malcolm SA, Thomas SA, et al. Risk factors for stress fractures in track and field athletes. A twelve-month prospective study. Am J Sports Med. 1996 Nov-Dec;24(6):810–818. doi: 10.1177/036354659602400617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bergman AG, Fredericson M, Ho C, Matheson GO. Asymptomatic tibial stress reactions: MRI detection and clinical follow-up in distance runners. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004 Sep;183(3):635–638. doi: 10.2214/ajr.183.3.1830635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boden BP, Osbahr DC. High-risk stress fractures: evaluation and treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2000 Nov-Dec;8(6):344–353. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200011000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brukner P, Bradshaw C, Khan KM, White S, Crossley K. Stress fractures: a review of 180 cases. Clin J Sport Med. 1996 Apr;6(2):85–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brunet ME, Cook SD, Brinker MR, Dickinson JA. A survey of running injuries in 1505 competitive and recreational runners. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 1990 Sep;30(3):307–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chisin R, Milgrom C, Giladi M, Stein M, Margulies J, Kashtan H. Clinical significance of nonfocal scintigraphic findings in suspected tibial stress fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987 Jul;(220):200–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choi K, Goldstein SA. A comparison of the fatigue behavior of human trabecular and cortical bone tissue. J Biomech. 1992 Dec;25(12):1371–1381. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(92)90051-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Datir AP. Stress-related bone injuries with emphasis on MRI. Clin Radiol. 2007 Sep;62(9):828–836. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2007.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deutsch AL, Coel MN, Mink JH. Imaging of stress injuries to bone. Radiography, scintigraphy, and MR imaging. Clin Sports Med. 1997 Apr;16(2):275–290. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5919(05)70022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fredericson M, Bergman AG, Hoffman KL, Dillingham MS. Tibial stress reaction in runners. Correlation of clinical symptoms and scintigraphy with a new magnetic resonance imaging grading system. Am J Sports Med. 1995 Jul-Aug;23(4):472–481. doi: 10.1177/036354659502300418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fredericson M, Jennings F, Beaulieu C, Matheson GO. Stress fractures in athletes. Top Magn Reson Imaging. 2006 Oct;17(5):309–325. doi: 10.1097/RMR.0b013e3180421c8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fudge BW, Westerterp KR, Kiplamai FK, et al. Evidence of negative energy balance using doubly labelled water in elite Kenyan endurance runners prior to competition. Br J Nutr. 2006 Jan;95(1):59–66. doi: 10.1079/bjn20051608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gaeta M, Minutoli F, Scribano E, et al. CT and MR imaging findings in athletes with early tibial stress injuries: comparison with bone scintigraphy findings and emphasis on cortical abnormalities. Radiology. 2005 May;235(2):553–561. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2352040406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goolsby MABM, Nattiv A. A Displaced Femoral Neck Stress Fracture in an Amenorrheic Adolescent Female Runner. Sports Health. 2012 Jul;4(4):352–356. doi: 10.1177/1941738111429929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haddad FS, Bann S, Hill RA, Jones DH. Displaced stress fracture of the femoral neck in an active amenorrhoeic adolescent. Br J Sports Med. 1997 Mar;31(1):70–72. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.31.1.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hamrick MW, Ding KH, Pennington C, et al. Age-related loss of muscle mass and bone strength in mice is associated with a decline in physical activity and serum leptin. Bone. 2006 Oct;39(4):845–853. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.He YX, Zhang G, Pan XH, et al. Impaired bone healing pattern in mice with ovariectomy-induced osteoporosis: A drill-hole defect model. Bone. 2011 Jun;48(6):1388–1400. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2011.03.720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hulkko A, Orava S. Stress fractures in athletes. Int J Sports Med. 1987 Jun;8(3):221–226. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1025659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ihle R, Loucks AB. Dose-response relationships between energy availability and bone turnover in young exercising women. J Bone Miner Res. 2004 Aug;19(8):1231–1240. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.040410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnon LCSH, Geits RW, et al. Histogenesis of stress fractures (abstract) J Bone Joint Surg. 1963;4(5A):1542. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson AW, Weiss CB, Jr, Wheeler DL. Stress fractures of the femoral shaft in athletes--more common than expected. A new clinical test. Am J Sports Med. 1994 Mar-Apr;22(2):248–256. doi: 10.1177/036354659402200216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones BH, Harris JM, Vinh TN, Rubin C. Exercise-induced stress fractures and stress reactions of bone: epidemiology, etiology, and classification. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 1989;17:379–422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jones BH, Thacker SB, Gilchrist J, Kimsey CD, Jr, Sosin DM. Prevention of lower extremity stress fractures in athletes and soldiers: a systematic review. Epidemiol Rev. 2002;24(2):228–247. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxf011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kelsey JL, Bachrach LK, Procter-Gray E, et al. Risk factors for stress fracture among young female cross-country runners. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007 Sep;39(9):1457–1463. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e318074e54b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kiuru MJ, Niva M, Reponen A, Pihlajamaki HK. Bone stress injuries in asymptomatic elite recruits: a clinical and magnetic resonance imaging study. Am J Sports Med. 2005 Feb;33(2):272–276. doi: 10.1177/0363546504267153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kiuru MJ, Pihlajamaki HK, Ahovuo JA. Bone stress injuries. Acta Radiol. 2004 May;45(3):317–326. doi: 10.1080/02841850410004724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lazzarini KM, Troiano RN, Smith RC. Can running cause the appearance of marrow edema on MR images of the foot and ankle? Radiology. 1997 Feb;202(2):540–542. doi: 10.1148/radiology.202.2.9015087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ludrook CCD. Energy expenditure and nutrient intake in long-distance runners. Nutrition Research. 1992;12(6):689–699. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marx RG, Saint-Phard D, Callahan LR, Chu J, Hannafin JA. Stress fracture sites related to underlying bone health in athletic females. Clin J Sport Med. 2001 Apr;11(2):73–76. doi: 10.1097/00042752-200104000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matheson GO, Clement DB, McKenzie DC, Taunton JE, Lloyd-Smith DR, MacIntyre JG. Stress fractures in athletes. A study of 320 cases. Am J Sports Med. 1987 Jan-Feb;15(1):46–58. doi: 10.1177/036354658701500107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Milgrom C, Giladi M, Stein M, et al. Stress fractures in military recruits. A prospective study showing an unusually high incidence. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1985 Nov;67(5):732–735. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.67B5.4055871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nattiv A. Stress fractures and bone health in track and field athletes. J Sci Med Sport. 2000 Sep;3(3):268–279. doi: 10.1016/s1440-2440(00)80036-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nattiv A, Loucks AB, Manore MM, Sanborn CF, Sundgot-Borgen J, Warren MP. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. The female athlete triad. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007 Oct;39(10):1867–1882. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e318149f111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Okamoto S, Arai Y, Hara K, Tsuzihara T, Kubo T. A displaced stress fracture of the femoral neck in an adolescent female distance runner with female athlete triad: A case report. Sports Med Arthrosc Rehabil Ther Technol. 2010;2:6. doi: 10.1186/1758-2555-2-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Papalada AMN, Tsitas K, Kiritsi O, Padhiar N, Del Buono, Maffulli N. Ultrasound as a primary evluation tool of bone stress injuries in elite track and field athletes. Am. J Sports Med. 2012;40(4):915–919. doi: 10.1177/0363546512437334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rauh MJ, Macera CA, Trone DW, Shaffer RA, Brodine SK. Epidemiology of stress fracture and lower-extremity overuse injury in female recruits. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006 Sep;38(9):1571–1577. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000227543.51293.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roub LW, Gumerman LW, Hanley EN, Jr, Clark MW, Goodman M, Herbert DL. Bone stress: a radionuclide imaging perspective. Radiology. 1979 Aug;132(2):431–438. doi: 10.1148/132.2.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shuer ML, Dietrich MS. Psychological effects of chronic injury in elite athletes. West J Med. 1997 Feb;166(2):104–109. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spitz DJ, Newberg AH. Imaging of stress fractures in the athlete. Radiol Clin North Am. 2002 Mar;40(2):313–331. doi: 10.1016/s0033-8389(02)00010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sullivan D, Warren RF, Pavlov H, Kelman G. Stress fractures in 51 runners. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1984 Jul-Aug;(187):188–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Williams NI, Helmreich DL, Parfitt DB, Caston-Balderrama A, Cameron JL. Evidence for a causal role of low energy availability in the induction of menstrual cycle disturbances during strenuous exercise training. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001 Nov;86(11):5184–5193. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.11.8024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wolf JH. [Julis Wolff and his "law of bone remodeling"] Orthopade. 1995 Sep;24(5):378–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yao L, Johnson C, Gentili A, Lee JK, Seeger LL. Stress injuries of bone: analysis of MR imaging staging criteria. Acad Radiol. 1998 Jan;5(1):34–40. doi: 10.1016/s1076-6332(98)80009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zeni AI, Street CC, Dempsey RL, Staton M. Stress injury to the bone among women athletes. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2000 Nov;11(4):929–947. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zernicke RM-GJ, Otis, et al. Stress fracture risk assessment among elite collegiate women runners. International Society of Biomechanics XIV Congress. 1993:1506–1507. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zwas ST, Elkanovitch R, Frank G. Interpretation and classification of bone scintigraphic findings in stress fractures. J Nucl Med. 1987 Apr;28(4):452–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]