Background: The serotonin transporter (SERT) mediates neuronal reuptake of serotonin and is inhibited by most antidepressants.

Results: A dualistic conformational response in SERT reveals a high affinity state in response to serotonin.

Conclusion: Membrane cholesterol modulates the dualistic conformational response to serotonin in SERT.

Significance: The interplay between the conformational responses in SERT and cholesterol is important for understanding an important pharmaceutical target in depression.

Keywords: Cholesterol, Membrane Protein, Monoamine Transporter, Neurotransmitter, Neurotransmitter Transport, Protein Conformation, Serotonin, Serotonin Transporter, Transport, LeuT

Abstract

Serotonergic neurotransmission is modulated by the membrane-embedded serotonin transporter (SERT). SERT mediates the reuptake of serotonin into the presynaptic neurons. Conformational changes in SERT occur upon binding of ions and substrate and are crucial for translocation of serotonin across the membrane. Our understanding of these conformational changes is mainly based on crystal structures of a bacterial homolog in various conformations, derived homology models of eukaryotic neurotransmitter transporters, and substituted cysteine accessibility method of SERT. However, the dynamic changes that occur in the human SERT upon binding of ions, the translocation of substrate, and the role of cholesterol in this interplay are not fully elucidated. Here we show that serotonin induces a dualistic conformational response in SERT. We exploited the substituted cysteine scanning method under conditions that were sensitized to detect a more outward-facing conformation of SERT. We found a novel high affinity outward-facing conformational state of the human SERT induced by serotonin. The ionic requirements for this new conformational response to serotonin mirror the ionic requirements for translocation. Furthermore, we found that membrane cholesterol plays a role in the dualistic conformational response in SERT induced by serotonin. Our results indicate the existence of a subpopulation of SERT responding differently to serotonin binding than hitherto believed and that membrane cholesterol plays a role in this subpopulation of SERT.

Introduction

Serotonergic neurotransmission in the central nervous system utilizes release of serotonin into the synaptic cleft in response to an action potential. This chemical signal relays the nerve impulse to the post-neuron via postsynaptic receptors or to achieve inhibition of serotonin release via presynaptic autoreceptors (1). Serotonin is taken up again by the presynaptic neuron via active transport by the membrane-embedded serotonin transporter (SERT),2 thereby modulating the duration and amplitude of the serotonergic signaling.

SERT belongs to a large family of the solute carrier superfamily 6 or neurotransmitter sodium symporters, which comprises a group of highly similar transporter proteins such as the dopamine transporter, the norepinephrine transporter, and the GABA transporter. SERT is a molecular target for antidepressant drugs such as tricyclic antidepressants (2–4), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (5–7), and psychostimulants such as cocaine (8) or 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA or “ecstasy”) (9).

Reuptake of released serotonin against its chemical gradient is mediated by SERT using the energetically favorable cotransport of Na+ and Cl− (10). Countertransport of intracellular K+ stimulates the reversal of the empty transporter from the cytoplasm-facing conformation to the outward-facing conformation (11, 12).

Different conformational states have been visualized in the various crystal structures of the prokaryotic leucine transporter, LeuT, a bacterial homologue of the mammalian neurotransmitter transporters (13–17). Substrate binding was observed in an outward-occluded (13) and inward-occluded conformation (52). An inward-facing conformation was seen without substrate (17). A more outward-facing conformation was only seen with a competitive inhibitor bound (14, 19).

Crystal structures of LeuT give a static three-dimensional picture of the transporter in a given conformational state, which provides a good framework for structure-based alignments and homology models for eukaryotic neurotransmitter transporters (20, 21). Structures of LeuT have led to models for the actual transport of substrate. In the “rocking bundle” model, the movement of the inverted transmembrane (TM) helices in relation to scaffold TM helices provides the dynamics leading to different conformations during substrate transport (22, 23). Using electron paramagnetic resonance it has been described how initial Na+ binding to LeuT opens the transporter to a more outward-facing conformation, whereas subsequent substrate binding results in a more inward-facing conformation (24). However, to further elucidate the dynamic changes that occur during binding of ligands and ions and translocation of substrate and ions, additional methods are required that address the human neurotransmitter transporters directly.

By exploiting the substituted cysteine accessibility method (25), various studies have shown several positions outside the binding site in the SERT to be sensitive to methanethiosulfonate (MTS) reagents (22, 26–31). Ser-277 in SERT is positioned in TM5 and is part of the cytoplasmic permeation pathway (32). Accessibility of S277C in the MTS-inert C5X background has earlier been shown to function as a good measure of conformational changes upon ligand and ion binding (31). Using this construct it has been shown that serotonin induces a more inward-facing conformation in SERT in the presence of both sodium and chloride ions (31). In contrast, a competitive inhibitor like cocaine induces a more outward-facing conformation in SERT in the presence of either sodium, chloride, or both ions (31), whereas the non-competitive inhibitor and substrate analog, ibogaine, induces a more inward-facing conformation (22, 33, 34).

In the present work we addressed the conformational changes that hSERT undergoes as a result of substrate binding by employing the substituted cysteine accessibility method (25) under conditions that are sensitized to detect a more outward-facing conformation. We observed a hitherto undescribed conformational state of hSERT induced by serotonin. This new conformational state is a more outward-facing conformation of SERT induced by serotonin binding, and it appears to reflect a state with higher affinity for serotonin than the state where serotonin induces an inward-facing conformation. The ionic requirements for this new conformational response to serotonin mirrors the ionic requirements for translocation and suggest that this high affinity outward-facing conformation is a new state in the transport cycle of serotonin, which has not been described earlier.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Mutagenesis

Site-directed mutagenesis of hSERT in the pCDNA3.1 vector was performed by PCR using the Phusion High-Fidelity DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs) and primers with appropriate nucleotide mismatches followed by DpnI digestion of the parent DNA. Escherichia coli XL10 Gold (Stratagene) were transformed with the mutated DNA and plated on LB agar plates with ampicillin selection. Mutant clones were cultured in LB medium, and plasmid DNA containing the mutated SERT cDNA was purified using either the GenElute Plasmid Miniprep kit (Sigma) or the PureYield Plasmid Midiprep System (Promega). Full-length sequencing using Big Dye 3.1 chemistry (Applied Biosystems) of the entire reading frame was used to verify introduction of the desired mutations and the absence of unwanted mutations.

Cell Culture and Expression of hSERT Constructs

Human embryonic kidney cells, HEK-293-MSR, (Invitrogen) were grown in monolayer in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Sigma) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Sigma), 1 units/ml penicillin, 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin (Sigma), 1× minimum essential medium non-essential amino acids (Gibco Life Technologies), and 0.6 mg/ml Geneticin at 95% humidity and 5% CO2 at 37 °C. HEK-293-MSR cells were detached with Versene (Invitrogen) and trypsin-EDTA (Sigma) and replated in cell culture dishes 24 h before transfection. A complex of 0.2 μg of plasmid and 0.5 μl of Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent (Invitrogen) in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium was used for transfection per cm2 of plating area and added to the adherent HEK-293-MSR cells in cell culture dishes 48 h before harvest.

Membrane Preparations

hSERT-transfected HEK-293-MSR cells were harvested by scraping 48 h after transfection. In brief, cells were harvested in 50 mm Tris-base buffer (150 mm NaCl, 20 mm EDTA, pH 7.4), centrifuged at 4,700 × g, washed, and homogenized in Tris-base buffer using a Ultra-turrax T25 (IKA Works, Wilmington, NC) before centrifugation at minimum 12,500 × g to sediment the membrane fraction. Homogenization and centrifugation at a minimum 12,500 × g and aspiration was performed twice. All steps were performed at 4 °C. The membrane preparations were resuspended and stored in 10 mm HEPES with 150 mm NaCl (adjusted to pH 8.0 with N-methyl-d-glucamine (NMDG+)) at −20 °C.

Cholesterol Extraction

Membrane cholesterol was removed by the addition of methyl-β-cyclodextrin to a final concentration of 2, 5, and 20 mg/ml membrane preparation in 10 mm HEPES with 150 mm NaCl (adjusted to pH 8.0 with NMDG+) and allowed to incubate at 37 °C for 30 min with gentle shaking followed by centrifugation at 12,000 × g at 4 °C for 15 min. The pellet containing hSERT in cholesterol-depleted membranes was resuspended in 10 mm HEPES (150 mm NaCl, pH 8.0, with NMDG+) and used immediately in the substituted cysteine accessibility method.

Substituted Cysteine Accessibility Method

Multiscreen HTS 96-well filtration plates (Millipore) treated with 0.1% PEI were used to capture homogenized membrane preparations of hSERT-transfected HEK-293-MSR cells. After membranes were bound to the filters in the filtration plates they were subjected to at least 6 washing steps with 10 mm HEPES buffer (supplemented with 150 mm NaCl, 150 mm sodium gluconate, or 150 mm NMDG-Cl, pH 8.0, adjusted with NMDG+). Incubation with the ligand proceeded for at least 25 min at room temperature before 2-aminoethyl MTS hydrobromide (MTSEA) (Apollo Scientific) was added in given concentrations and incubated with the hSERT-containing crude membranes for 15 min simultaneously with ligand. At least six washes with 10 mm HEPES buffer (150 mm NaCl, NMDG+-adjusted pH 8.0) terminated the MTS reaction with hSERT. To quantify residual unreacted hSERT, the membranes were then incubated with 0.1 nm 125I-RTI-55 for at least 60 min. At least 5 washes of the filters with ice-cold 10 mm HEPES (150 mm NaCl) were performed to remove unbound radioligand. The dry filters were then dissolved in Microscint20 (Packard), and bound 125I-RTI-55 was quantified on a Packard Topcounter NXT scintillation counter.

Data Calculations

EC50 data were fitted by nonlinear regression to a sigmoidal dose-response curve with variable slope and/or to a bell-shaped dose-response curve with the in-built tools in GraphPad Prism 5.0.

RESULTS

Generation of hSERT Mutant Constructs

Five endogenous cysteine residues previously shown to be sensitive to MTS reagents (27, 30) were replaced by alanine or isoleucine (C15A/C21A/C109A/C357I/C622A) and used as an MTS-insensitive background (C5X). Serine 277, in TM5, is located in the cytoplasmic permeation pathway (31). As a consequence, S277C becomes more accessible to the MTS reagent, MTSEA, when SERT shifts its conformational equilibrium from outward-facing to inward-facing. In the following, membranes from HEK-293-MSR cells expressing hSERT C5X, hSERT C5X_S277A, or hSERT C5X_S277C were used to address the conformational dynamics of SERT induced by serotonin. The membranes were preincubated with serotonin and ions in different combinations before simultaneous reaction with MTSEA in the stated concentrations.

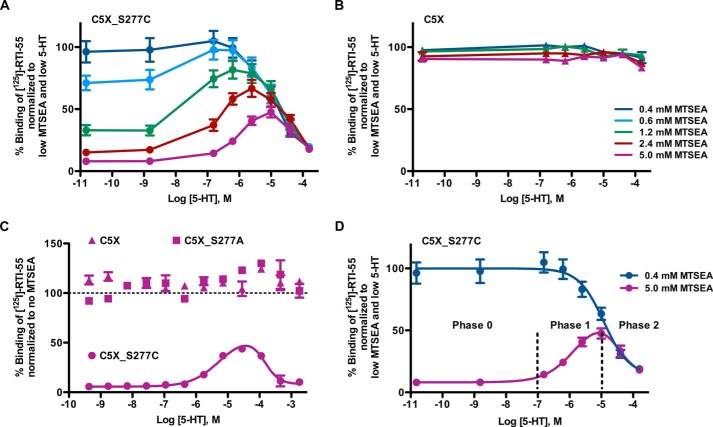

A Dualistic Conformational Response to Serotonin

SERT exhibits a biphasic conformational response to serotonin. We observed an increased inactivation of S277C at high concentrations of MTSEA as measured by a lowered RTI-55 binding compared with RTI-55 binding after MTSEA reaction at low concentrations (Fig. 1A, filled circles), consistent with a population of transporters with S277C sufficiently buried to withstand 0.4 mm MTSEA but not higher concentrations of MTSEA. Surprisingly, this subpopulation of SERT, only detectable at high MTSEA concentrations, appeared to become more resilient to MTSEA inactivation at concentrations of serotonin up to 10 μm in a dose-dependent manner demonstrating that serotonin induces a conformation in this subpopulation that more effectively shields S277C from MTSEA reaction, i.e. serotonin induces a conformation that closes the cytoplasmic permeation pathway. Closing of the cytoplasmic permeation pathway is consistent with the transporter being more open to the extracellular permeation pathway according to the rocking bundle mechanism proposed by Forrest et al. (22). Above 10 μm serotonin, the well described (27, 30, 31) effect of serotonin to induce a more inward-facing conformation became apparent both for the conformational subpopulation of hSERT sensitive to 0.4 mm MTSEA and the less cytoplasm-facing conformational subpopulation of hSERT that required higher concentrations of MTSEA for inactivation. This dualistic response to serotonin was undetectable at 0.4 mm MTSEA and was visualized most clearly at 5 mm MTSEA. The dualistic response was already noticeable at 0.6 mm MTSEA (Fig. 1A, light blue filled circles). Neither the sensitivity to high MTSEA concentrations nor the dualistic response to serotonin was observed in the MTS-insensitive C5X-background construct (Fig. 1B, open triangles) or the C5X_S277A control construct (Fig. 1C, filled squares), showing that the inactivation by both low and high concentrations of MTSEA was not an indirect effect of Ser-277 mutation but was indeed via reaction with S277C. Furthermore, the differential inactivation by MTS in response to serotonin was solely by a substrate-induced differential exposure of S277C.

FIGURE 1.

A new dualistic conformational response to serotonin can be monitored in the MTS-sensitive C5X_S277C mutant at high MTSEA concentrations. Membranes from HEK-293-MSR cells expressing hSERT C5X_S277C, C5X, and C5X_S277A were preincubated with serotonin ranging from nm to mm in binding buffer containing 150 mm NaCl for 25 min before simultaneous MTSEA reaction in varying concentrations: 0.4 mm (dark blue), 0.6 mm (light blue), 1.2 mm (green), 2.4 mm (red), and 5.0 mm (purple). The degree of inactivation was measured by determining the remaining binding of 125I-RTI-55. Normalized binding (mean ± S.E.) is plotted as a function of serotonin concentration. A, C5X_S277C is protected from inactivation by high concentrations of MTSEA by low micromolar concentrations of serotonin, whereas higher concentrations of serotonin expose S277C. Data are shown as a global fit of duplicate determinations from four independent experiments. B, the reference construct C5X is insensitive to different concentrations of MTSEA and does not exhibit serotonin-dependent changes in MTSEA sensitivity. Data are shown as a global fit of duplicate determinations from two independent experiments. C, neither C5X nor C5X_S277A was inactivated by MTSEA nor did either exhibit serotonin-dependent changes in MTSEA sensitivity, whereas C5X_S277C under identical conditions exhibit a bimodal conformational response to serotonin. Data are from a representative experiment. C5X_S277A was tested in duplicate in four independent experiments with similar results. D, the dualistic response can be fitted to a biphasic sigmoidal dose-response curve and is composed of three phases; Phase 0, A non-responding state; Phase 1, a high affinity serotonin-inducible outward-facing state; Phase 2, a low affinity serotonin-inducible inward-facing state. The dualistic response to serotonin is only detectable when a high concentration of MTSEA (5 mm: purple) is used compared with low concentration of MTSEA (0.4 mm: blue).

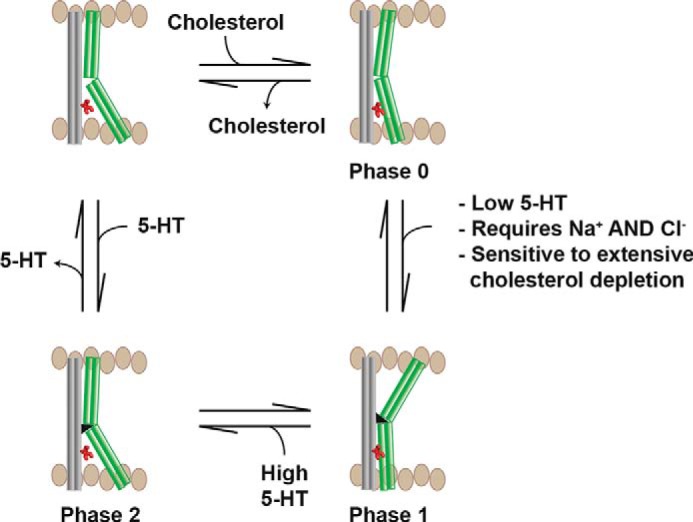

The dualistic conformational response to serotonin is composed of a, to our knowledge hitherto undescribed, more outward-facing phase and a previously described (27) inward-facing phase (Fig. 1D). Thus, the conformational response to serotonin consists of three phases. Phase 0 is a non-responding state (serotonin concentration up to 0.1 μm) likely reflecting an apo state. Phase 1 is the novel serotonin-induced outward-facing state (serotonin concentration 0.1–10 μm). Phase 2 is a serotonin-induced inward-facing conformation (serotonin concentrations 10–100 μm). The new serotonin-induced outward-facing conformation in Phase 1 is a high affinity state, whereas the serotonin-induced inward-facing conformation in Phase 2 represents a low affinity state.

The Inward-facing Conformation

When two opposite conformational responses to serotonin binding are detected it poses the question of whether these both could be relevant to the normal function of the transporter.

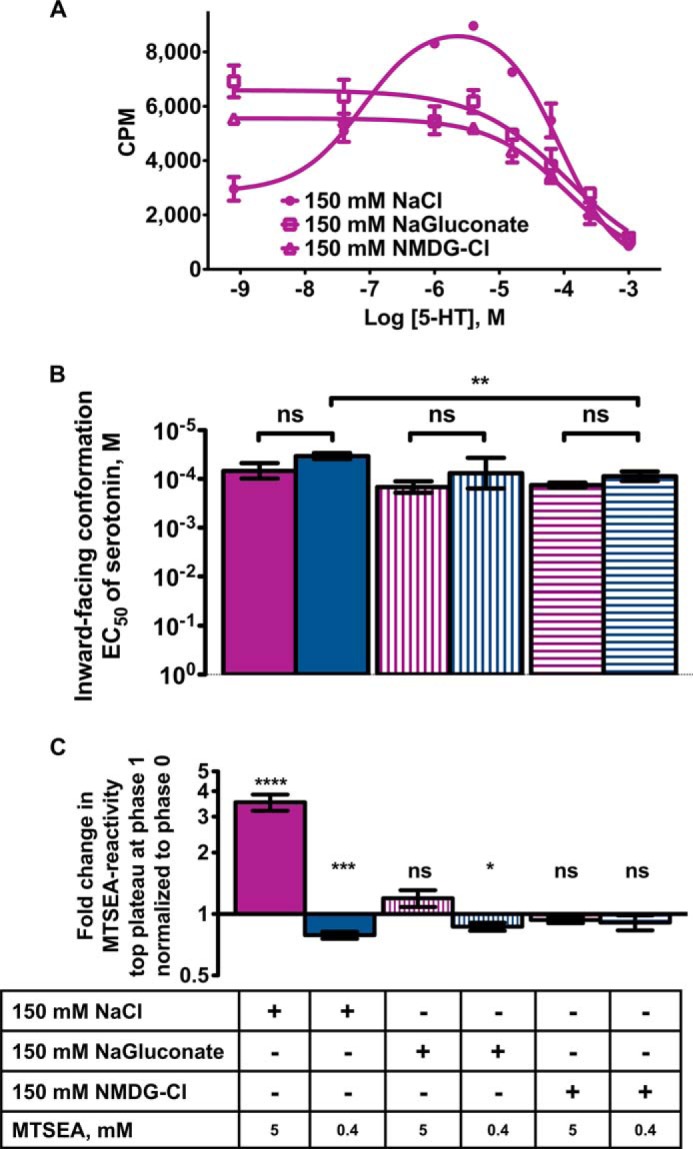

When comparing the effect of sodium and chloride ions on the cytoplasmic permeation pathway of SERT in response to serotonin, both sodium ions alone (150 mm sodium gluconate), chloride ions alone (150 mm NMDG-Cl), or both ions in combination (150 mm NaCl) were able to support the inward-facing conformational response to serotonin (Fig. 2A). The EC50 values of serotonin for inducing the inward-facing conformation (Phase 2) is independent of the concentration of MTS (Fig. 2B), indicating again that both high and low MTSEA concentrations target the same residue, S277C. However, in the conformational subpopulation of hSERT sensitive to 0.4 mm MTSEA (Fig. 2B, blue bars), the ability of serotonin to induce the inward-facing conformation required significantly less serotonin when both sodium and chloride ions (150 mm NaCl) were present simultaneously compared with chloride ions (150 mm NMDG-Cl) alone (EC50 (5-HT, NaCl) = 34 μm versus EC50 (5-HT, NMDG-Cl) = 88 μm, p = 0.0064, t test) (Fig. 2B).

FIGURE 2.

The dualistic response to serotonin has ionic requirements resembling conditions allowing translocation of serotonin across the membrane. A, the dualistic response to serotonin was only observed when the membranes were preincubated in both sodium and chloride (150 mm NaCl, filled circles). Preincubation of membranes with serotonin in combination with either sodium (150 mm sodium gluconate: open squares) or chloride (150 mm NMDG-Cl, open triangles) only show the inward-facing conformation. Shown are data from a representative experiment; the experiments were repeated at least three times. Error bars represent S.E. B, the ability of serotonin to induce the inward-facing conformation is independent of MTSEA concentration. The EC50 values of serotonin for inducing the inward-facing conformation is independent of high (5 mm, purple bars) and low (0.4 mm: blue bars) concentration of MTSEA (t test). The removal of sodium (150 mm NMDG-Cl) significantly increased the EC50 value of serotonin for inducing the inward-facing conformation compared with 150 mm NaCl as measured with 0.4 mm MTSEA (**, p = 0.0064, t test). The experiments were repeated at least 3 times. Bars show mean serotonin EC50 ± S.E. to induce inward-facing conformation (Phase 2). ns, not significant. C, the serotonin-induced outward-facing conformation in SERT is dependent on MTSEA concentration and has ionic requirements. The -fold change in MTS reactivity (top plateau at Phase 1) normalized to Phase 0 was only significantly above 1 at high concentration of MTSEA (5 mm, purple bar) when both sodium and chloride were present (150 mm NaCl, filled bar) (p < 0.0001, one-sample t test). The experiments were repeated at least three times. Bars show mean -fold change ± S.E. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; ****, p < 0.0001.

The High Affinity Outward-facing Conformation

The high affinity outward-facing conformation of SERT induced by serotonin has ionic requirements that resemble conditions that allow translocation of serotonin across the membrane (Fig. 2, A and C). The most profound outward-facing response to serotonin was seen at serotonin concentrations around 10 μm and visualized as the top plateau at Phase 1 (Fig. 1D, magenta curve). The -fold change in MTS reactivity (Fig. 2C) at top plateau in Phase 1 normalized to Phase 0 (no serotonin present) gave a measure of the minimum response to serotonin in Phase 1. This response may actually be larger than immediately evident if the top plateau of Phase 1 is lowered by overlapping with Phase 2. The outward-facing conformational response to serotonin binding is only seen in the conformational subpopulation of hSERT insensitive to low concentrations of MTSEA and has ionic requirements similar to those required for transport. The outward-facing response to serotonin was only exhibited when both sodium and chloride ions (150 mm NaCl) were present simultaneously with a high MTSEA concentration and serotonin (Fig. 2C, purple solid bar) with a mean EC50 value of serotonin at 0.4 μm. Although resulting in a initially less inward-facing conformation, this EC50 for Phase 1 is much more consistent with the apparent transport affinity of 0.7 μm serotonin measured earlier (35) than the 34 μm serotonin in Phase 2. This suggests that the rate-limiting conformational transition in serotonin translocation with regard to serotonin binding is the high affinity binding of serotonin (Phase 1) that initially results in a more outward-facing conformation.

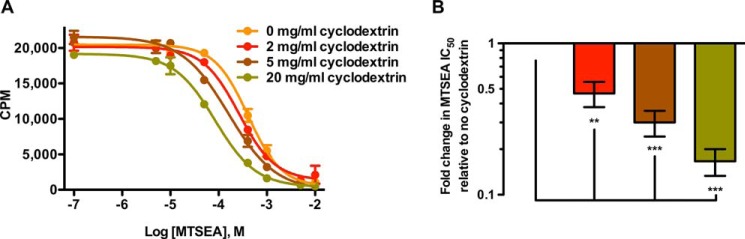

Cholesterol Depletion Changes the Conformational Equilibrium in SERT

Cholesterol depletion by treatment of membranes with methyl-β-cyclodextrin alters the accessibility of S277C to MTSEA (Fig. 3).3 The more methyl-β-cyclodextrin the membranes were treated with, the more sensitive S277C became to MTS reaction (Fig. 3A), i.e. the conformational equilibrium of SERT was shifted toward a more inward-facing conformation when membrane cholesterol content were decreased. We find that the IC50 values for MTSEA reaction were significantly 2-, 4-, and 6-fold lower for 2, 5, and 20 mg/ml methyl-β-cyclodextrin, respectively (p < 0.01, 0.001, and 0.001, respectively, repeated measures one-way ANOVA, Bonferroni's multiple comparisons test) (Fig. 3B). The top plateaus for the MTSEA inhibition curves were not significantly different (p = 0.096, one-way ANOVA, Bonferroni's multiple comparisons test) (Fig. 3A), indicating that the treatment with methyl-β-cyclodextrin does not influence the number of functional SERT capable of binding the cocaine analog RTI-55.

FIGURE 3.

Cholesterol alters the accessibility of S277C to MTSEA. To remove cholesterol, membranes from HEK-293-MSR cells expressing hSERT C5X_S277C were pretreated with methyl-β-cyclodextrin in different concentrations; 0 mg/ml (yellow), 2 mg/ml (red), 5 mg/ml (brown), and 20 mg/ml (green) for 30 min at 37 °C. MTSEA reaction in standard binding buffer containing 150 mm NaCl was performed for 15 min. A, representative plot of the reactivity of MTSEA to S277C against total binding of 125I-RTI-55 (mean cpm ± S.E.). The data were fitted to a sigmoidal dose-response curve with variable slope. Treatment with methyl-β-cyclodextrin increased the accessibility of S277C to MTSEA. The top plateaus were independent of treatment with methyl-β-cyclodextrin (p = 0.096, one-way ANOVA, Bonferroni's multiple comparisons test). B, -fold change in MTS reactivity (IC50 values for MTSEA at various methyl-β-cyclodextrin concentrations normalized to IC50 for untreated membranes) was significantly different for 2, 5, and 20 mg/ml methyl-β-cyclodextrin compared with untreated membranes (repeated measures one-way ANOVA, Bonferroni's multiple comparisons test) in a dose-dependent manner. The experiments were repeated three times in duplicate. Data are mean -fold change ± S.E. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; ****, p < 0.0001.

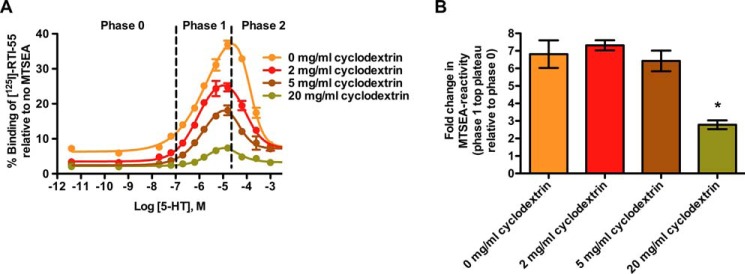

Membrane Cholesterol Influences the Conformational Response to Serotonin

Membrane protein conformation may be modulated by cell membrane components. SERT has been shown to exist in cholesterol-rich membrane domains (37), and these domains may influence ligand affinities (37, 38). Furthermore, cholesterol has been found to affect the conformation of the dopamine transporter (39), and in the recent structure of the Drosophila dopamine transporter a cholesterol molecule was co-crystallized in a groove in the transmembrane part of the transporter (40). We have described how cholesterol affects the conformational equilibrium of hSERT.3 The existence of two conformationally distinct subpopulations of SERT in the membrane begs the question of whether these could exist as a consequence of different localization to cholesterol-rich microdomains and/or as a result of different degrees of cholesterol binding.

The ability of serotonin to induce a high affinity outward-facing conformation in SERT is dependent on cholesterol. When comparing the effect of cholesterol depletion on the serotonin-induced high affinity outward-facing conformation, both untreated and methyl-β-cyclodextrin-treated membranes expressing hSERT were able to obtain the outward-facing conformation in response to serotonin (Fig. 4). However, cholesterol depletion induces a more inward-facing conformation (Fig. 3A) that shifted the equilibrium of SERT able to obtain the serotonin-induced outward-facing conformation. The top plateau (Phase 1) in membranes treated with 20 mg/ml methyl-β-cyclodextrin (Fig. 4, green curve) was significantly lower than top plateaus in untreated membranes and membranes treated with 2 and 5 mg/ml methyl-β-cyclodextrin (p = 0.0066, repeated measures one-way ANOVA, Bonferroni's multiple comparisons test), i.e. the number of SERTs in membranes treated with 20 mg/ml methyl-β-cyclodextrin that were able to obtain a serotonin-induced outward-facing conformation was relatively lower than the number of SERTs in untreated membranes and membranes treated with 2 and 5 mg/ml methyl-β-cyclodextrin that were able to obtain a high affinity outward-facing conformation induced by serotonin. The top plateaus (Phase 1) in membranes treated with 2 and 5 mg/ml methyl-β-cyclodextrin (Fig. 4, red and brown curves) were not significantly lower than top plateau in untreated membranes (Fig. 4, yellow) (p = 0.70, repeated one-way ANOVA, Bonferroni's Multiple comparisons test) indicating that moderate cholesterol depletion (2 and 5 mg/ml methyl-β-cyclodextrin) did not seem to affect the equilibrium of SERT able to obtain a serotonin-induced outward-facing conformation.

FIGURE 4.

Cholesterol influences the conformational response to serotonin. Membranes from HEK-293-MSR cells expressing hSERT C5X_S277C were pretreated with methyl-β-cyclodextrin in different concentrations; 0 mg/ml (yellow), 2 mg/ml (red), 5 mg/ml (brown), and 20 mg/ml (green) for 30 min at 37 °C. Preincubation was performed with serotonin ranging from nm to mm in standard binding buffer containing 150 mm NaCl for 25 min before simultaneous MTSEA reaction (5.0 mm) for 15 min. The experiments were repeated three times in duplicate. A, the serotonin-induced outward-facing conformation in SERT was dependent on cholesterol. A representative plot of the relative number of SERTs able to obtain an outward-facing conformation (top plateau at Phase 1) induced by serotonin was decreased in the membranes treated with 20 mg/ml methyl-β-cyclodextrin compared with untreated membranes and membranes treated with 2 and 5 mg/ml methyl-β-cyclodextrin, but the affinity for serotonin was independent of cholesterol depletion. The EC50 values of serotonin for inducing the outward-facing conformation (Phase 1) were independent of treatment with methyl-β-cyclodextrin (p = 0.57, repeated measures one-way ANOVA, Bonferroni's multiple comparisons test). The EC50 values of serotonin for inducing the inward-facing conformation (Phase 2) were independent of treatment with methyl-β-cyclodextrin (p = 0.74, repeated measures one-way ANOVA, Bonferroni's Multiple comparisons test). B, the number of SERTs able to obtain the serotonin-induced outward-facing conformation was unaffected by moderate cholesterol depletion and only decreased after extensive cholesterol depletion. -Fold change in MTS reactivity (top plateau at Phase 1 normalized to Phase 0 was significantly lower at 20 mg/ml methyl-β-cyclodextrin compared with 0, 2, and 5 mg/ml methyl-β-cyclodextrin (p = 0.007, repeated measures one-way ANOVA, Bonferroni's Multiple comparisons test). -Fold change in MTS reactivity in membranes treated with 20 mg/ml methyl-β-cyclodextrin was significantly different from 0 (p = 0.008, on-sample t test). Shown are the means and S.E. from three independent experiments.

Even though the equilibrium of SERT able to obtain the high affinity outward-facing conformation induced by serotonin was shifted in the comprehensively cholesterol-depleted membranes (20 mg/ml methyl-β-cyclodextrin), the top plateau (Phase 1) (Fig. 4, green) was significantly different from 0 (p = 0.008, one-sample t test), indicating that there still are a number of SERTs able to obtain a serotonin-induced outward-facing conformation despite extensive cholesterol depletion. Both untreated membranes and cholesterol-depleted membranes contain SERTs that respond in a similar manner to serotonin, showing a high affinity outward-facing conformational response to serotonin and a low affinity inward-facing conformational response to serotonin. The mean EC50 values of serotonin for inducing the outward-facing conformation (Phase 1) were not significantly different in untreated membranes compared with membranes treated with 2, 5, and 20 mg/ml (p = 0.57, repeated one-way ANOVA, Bonferroni's multiple comparisons test) (Fig. 4A). The mean EC50 values of serotonin for inducing the inward-facing conformation (Phase 2) were not significantly different in untreated membranes compared with membranes treated with 2, 5, and 20 mg/ml (p = 0.74, repeated one-way ANOVA, Bonferroni's multiple comparisons test) (Fig. 4A).

DISCUSSION

The substituted cysteine accessibility method (25) used here exploits that the binding of the high affinity cocaine analog RTI-55 to hSERT can be eliminated by reaction of MTSEA with S277C in TM5 and that this reaction is dependent on transporter conformation. The best location of the sensor cysteine depends on which conformational change is studied. In a transporter that transports substrate from the extracellular side of the membrane, this transporter is most likely waiting to bind substrate, especially in the presence of sodium (24). In a transporter where the ground state is most likely partially outward-facing the largest relative change in reactivity upon an even more outward-facing conformation would be on the intracellular side, whereas for most transporters the extracellular residues would still be highly exposed. Therefore, if a more outward-facing conformation is to be measured, this is done most sensitively at a position where the relative change is larger, i.e. at the intracellular side. However, it may require higher concentrations of MTSEA, as we show here.

The rat SERT C5X mutant, lacking all endogenous cysteine residues (C15A/C21A/C109A/C357I/C622A) previously shown to be insensitive to MTS reagents (27, 30), has been used earlier as an inert background to the S277C sensor mutant. This construct has been shown to exhibit reduced uptake that is mirrored by a similarly reduced surface expression, suggesting that this transporter operates with WT-like turnover rates (27). We confirm here that the inert background construct, hSERT C5X, indeed is insensitive to MTSEA reagents in the concentration span employed in the present study (Fig. 1B) and that the introduction of an alanine mutation at position 277 does not lead to the emergence of deleterious MTSEA reactivity for any of the remaining cysteines (Fig. 1C). Also, the radioligand affinity of C5X_S277C is found to be very similar to hSERT WT (KD = 1.928 and 0.709 nm, respectively). Therefore, we conclude that hSERT C5X_S277C is suited for the study of conformational changes in hSERT. Thus, conformational changes in SERT induced by serotonin in the presence of MTSEA were monitored by quantifying residual binding of the radiolabeled cocaine analog 125I-RTI-55 to C5X_S277C hSERT.

According to crystal structures of LeuT (13) and derived homology models (20, 21), Ser-277 in SERT is positioned in TM5 and is part of the cytoplasmic pathway (31, 32). Accessibility of S277C in the C5X template has been shown earlier to function as a good indicator for conformational changes upon ligand and ion binding (31). Although S277C is located in the intracellular permeation pathway, it has been shown to be a reliable reporter of a more outward-facing conformation; S277C is able to detect the more outward-facing conformation induced by cocaine (27, 33) and the antidepressants imipramine and fluoxetine (6). Furthermore, a more outward-facing conformation upon Na+ binding has been reported from EPR studies of the bacterial homologue LeuT (24), and we were able to reproduce this very same induction of a more outward-facing conformation by Na+ with the S277C sensor cysteine in the present study (Fig. 2C). Thus, our data show that we can detect both a more inward-facing conformation and a more outward-facing conformation with the S277C sensor cysteine.

Using higher concentrations of MTSEA, we discovered a novel conformational response to serotonin. We were surprised to find that the high affinity binding of serotonin results in a more-outward-facing conformation, whereas it requires higher concentrations of serotonin (>10 μm) to see the expected more inward-facing conformation. The curves can be fitted to a biphasic sigmoidal dose-response curve. When such bimodal relationships are studied they can be convoluted if the two phases are highly overlapping. In the present case we know the top plateau of Phase 2 (Fig. 1D) must be <100%, which allowed us to determine a minimum 5-HT EC50 for Phase 2, which we found was similar to the EC50 determined at conditions (0.4 mm MTSEA) where Phase 1 was absent (Fig. 2B). However, the underlying top plateau of Phase 1 may be depressed by Phase 2, which could lead to an underestimation of the EC50 for serotonin in Phase 1. With that in mind we make no attempt to determine it precisely but note that it appears to be in the low micromolar range, which is consistent with the Km value for serotonin determined in numerous laboratories. Therefore, the novel outward-facing conformational change in response to serotonin better reflects a critical and rate-determining step in the translocation process. The immediate implication is that the conformational response that we describe here is an integrated part of the translocation process and precedes the more expected induction of an inward-facing conformation.

Binding of ions to the serotonin transporter, their interplay with serotonin binding, and how it effects conformational change is important for the understanding of the transport mechanism. In the present study we use isolated membranes, which precludes the existence of transmembrane gradients. However, other studies have successfully used exactly the same methodology to extract knowledge about ionic requirements and the transport mechanism (22, 41). In these earlier studies, membranes from HeLa cells expressing rat SERT C5X_S277C showed increased reactivity toward MTSEA, when the membranes were preincubated with serotonin and MTSEA, but this serotonin-induced inward-facing conformation was dependent of the presence of both sodium and chloride ions (150 mm NaCl) (31). Our results show that the serotonin-induced inward-facing conformation is obtained with either sodium (150 mm sodium gluconate), chloride (150 mm NMDG-Cl), or both ions (150 mm NaCl) (Fig. 2, A and B). However, the serotonin-induced inward-facing conformation of hSERT obtained without the presence of sodium in our study did require more serotonin than when both sodium and chloride ions were present, consistent with cooperative binding of serotonin and sodium.

The ability of serotonin to induce the inward-facing conformation is independent of MTSEA concentration (Fig. 2B) and independent of ionic requirements. It has previously been shown that sodium from the Na2 site is most likely the first step required before serotonin can be released to the cytoplasm from an inward-facing transporter (42). In addition we see that SERT is able to obtain the inward-facing conformation independent of sodium (Fig. 2, A and B), but it is not possible to determine whether this more inward-facing SERT obtained independent of sodium might be inward-facing enough to release serotonin via the cytoplasmic permeation pathway.

The induction of the novel high affinity outward-facing conformation shows ionic dependence (Fig. 2, A and C) that mirrors the ionic requirements for translocation, i.e. the high affinity outward-facing conformation is only observable in the presence of both sodium and chloride ions (150 mm NaCl) compared with the presence of either sodium (150 mm sodium gluconate) or chloride (150 mm NMDG-chloride). Furthermore, it is only observable in the less inward-facing conformational subpopulation of hSERT that requires higher concentrations of MTSEA for inactivation.

The transport of serotonin through SERT is dependent on the presence of sodium ions or a combination of sodium and chloride ions (43, 44), whereas the binding of serotonin measured by displacement of a radioligand is not dependent on sodium ions (45). The high affinity outward-facing conformation can, therefore, be seen as a conformational step attained in the initial steps of the transport cycle of serotonin, as this conformational state has the same ionic requirements as translocation of serotonin through SERT. The purpose, if it exists, of such a conformational step that on the surface looks counterproductive in terms of obtaining the inward-facing conformation in order to translocate serotonin is not immediately obvious from our study. The dualistic conformational response to serotonin is only observable in a subpopulation of SERT. This subpopulation has S277C more buried requiring more MTSEA to be inactivated. One possible interpretation could be that there exist two subpopulations of hSERT in the membrane with differential conformational response to serotonin, possibly in a dynamic equilibrium, where one subpopulation would be more active than the other as has been suggested by the use of different methods (46). This would provide an extra pool of SERTs that could possibly be readily activated on demand. Cholesterol might play a role for this subpopulation, possibly by sequestering a subpopulation of hSERT in cholesterol-rich microdomains (37). The crystal structure of the dopamine transporter locked in an outward-facing conformation showed a cholesterol molecule in a small groove delimited by TMs 1a, 5, and 7 in the cytoplasmic part of the dopamine transporter (40). This cholesterol might play a role in stabilizing the outward-open state of the transporter. In our study we see that cholesterol depletion stabilizes a more inward-facing conformation of SERT (Figs. 3 and 5). This could probably be explained by the removal of the cholesterol molecule seen in the crystal structure of the dopamine transporter (40). Likewise, cholesterol might play a part in the subpopulation of SERTs in our study that is able to obtain a high affinity serotonin-induced outward-facing conformation. One could speculate that the mild to moderate cholesterol depletion in our study, which does not significantly affect the ability of hSERT to attain a high affinity outward-facing conformation and a low affinity inward-facing conformation in response to serotonin (Fig. 4, 2 and 5 mg/ml methyl-β-cyclodextrin), could correspond to drawing SERT out of cholesterol-rich microdomains. But the dramatic cholesterol depletion significantly shifts the equilibrium of SERT able to obtain the high affinity outward-facing conformation and a low affinity inward-facing conformation in response to serotonin (Fig. 4, 20 mg/ml methyl-β-cyclodextrin) could correspond to affecting the binding of cholesterol directly to SERT and not just depleting cholesterol surrounding SERT in the membrane (Fig. 5).

FIGURE 5.

Model for the effects of substrate, cotransported ions and cholesterol on hSERT conformation.

One could also envision that two serotonin molecules are required to bind in order to obtain transport similarly to what has been suggested for LeuT (47). This would suggest that one serotonin molecule binds first to give a more outward-facing conformation, which would better allow binding of a second serotonin molecule, which would then effect translocation. However, the low affinity nature (EC50 = 34 μm) of this secondary binding would argue against it being important for translocation, which have reproducibly been determined to be around one micromolar (18, 35, 36, 44, 48–51) unless the rate-limiting step of the transport cycle is the high affinity conformational response to serotonin (Phase 1).

Acknowledgments

We thank Bente Ladegaard for technical assistance and Professor Gary Rudnick for helping to establish the substituted cysteine accessibility method.

This work was supported by a grant from the Lundbeck Foundation.

K. Severinsen, L. Lauersen, K. B. Kristensen, P. F. Martens, and S. Sinning, submitted for publication.

- SERT

- serotonin transporter

- hSERT

- human SERT

- TM

- transmembrane

- NMDG+

- N-methyl-d-glucamine

- MTS

- methanethiosulfonate

- MTSEA

- 2-aminoethylmethanethiosulfonate

- 5-HT

- 5-hydroxytryptamine

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance.

REFERENCES

- 1. Cerrito F., Raiteri M. (1979) Serotonin release is modulated by presynaptic autoreceptors. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 57, 427–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Carlsson A., Fuxe K., Ungerstedt U. (1968) The effect of imipramine on central 5-hydroxytryptamine neurons. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 20, 150–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Marshall E. F., Stirling G. S., Tait A. C., Todrick A. (1960) The effect of iproniazid and imipramine on the blood platelet 5-hydroxytrptamine level in man. Br J. Pharmacol. Chemother. 15, 35–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sinning S., Musgaard M., Jensen M., Severinsen K., Celik L., Koldsø H., Meyer T., Bols M., Jensen H. H., Schiøtt B., Wiborg O. (2010) Binding and orientation of tricyclic antidepressants within the central substrate site of the human serotonin transporter. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 8363–8374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Koldsø H., Severinsen K., Tran T. T., Celik L., Jensen H. H., Wiborg O., Schiøtt B., Sinning S. (2010) The two enantiomers of citalopram bind to the human serotonin transporter in reversed orientations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 1311–1322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tavoulari S., Forrest L. R., Rudnick G. (2009) Fluoxetine (Prozac) binding to serotonin transporter is modulated by chloride and conformational changes. J. Neurosci. 29, 9635–9643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Siwers B., Ringberger V. A., Tuck J. R., Sjöqvist F. (1977) Initial clinical trial based on biochemical methodology of zimelidine (a serotonin uptake inhibitor) in depressed patients. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 21, 194–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stacey R. S. (1961) Uptake of 5-hydroxytryptamine by platelets. Br J. Pharmacol. Chemother. 16, 284–295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rudnick G., Wall S. C. (1992) The molecular mechanism of “ecstasy” [3,4-methylenedioxy- methamphetamine (MDMA)]: serotonin transporters are targets for MDMA- induced serotonin release. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89, 1817–1821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lingjaerde O. (1969) Uptake of serotonin in blood platelets: Dependence on sodium and chloride, and inhibition by choline. FEBS Lett. 3, 103–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rudnick G., Clark J. (1993) From synapse to vesicle: the reuptake and storage of biogenic amine neurotransmitters. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1144, 249–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rudnick G., Nelson P. J. (1978) Platelet 5-hydroxytryptamine transport, an electroneutral mechanism coupled to potassium. Biochemistry 17, 4739–4742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yamashita A., Singh S. K., Kawate T., Jin Y., Gouaux E. (2005) Crystal structure of a bacterial homologue of Na+/Cl−-dependent neurotransmitter transporters. Nature 437, 215–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Singh S. K., Yamashita A., Gouaux E. (2007) Antidepressant binding site in a bacterial homologue of neurotransmitter transporters. Nature 448, 952–956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhou Z., Zhen J., Karpowich N. K., Goetz R. M., Law C. J., Reith M. E., Wang D. N. (2007) LeuT-desipramine structure reveals how antidepressants block neurotransmitter reuptake. Science 317, 1390–1393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhou Z., Zhen J., Karpowich N. K., Law C. J., Reith M. E., Wang D. N. (2009) Antidepressant specificity of serotonin transporter suggested by three LeuT-SSRI structures. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 16, 652–657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Krishnamurthy H., Gouaux E. (2012) X-ray structures of LeuT in substrate-free outward-open and apo inward-open states. Nature 481, 469–474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Andersen J., Taboureau O., Hansen K. B., Olsen L., Egebjerg J., Strømgaard K., Kristensen A. S. (2009) Location of the antidepressant binding site in the serotonin transporter: importance of Ser-438 in recognition of citalopram and tricyclic antidepressants. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 10276–10284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wang H., Goehring A., Wang K. H., Penmatsa A., Ressler R., Gouaux E. (2013) Structural basis for action by diverse antidepressants on biogenic amine transporters. Nature 503, 141–145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Beuming T., Shi L., Javitch J. A., Weinstein H. (2006) A comprehensive structure-based alignment of prokaryotic and eukaryotic neurotransmitter/Na+ symporters (NSS) aids in the use of the LeuT structure to probe NSS structure and function. Mol. Pharmacol. 70, 1630–1642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Celik L., Sinning S., Severinsen K., Hansen C. G., Møller M. S., Bols M., Wiborg O., Schiøtt B. (2008) Binding of serotonin to the human serotonin transporter. Molecular modeling and experimental validation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 3853–3865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Forrest L. R., Zhang Y. W., Jacobs M. T., Gesmonde J., Xie L., Honig B. H., Rudnick G. (2008) Mechanism for alternating access in neurotransmitter transporters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 10338–10343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Forrest L. R., Rudnick G. (2009) The rocking bundle: a mechanism for ion-coupled solute flux by symmetrical transporters. Physiology 24, 377–386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Claxton D. P., Quick M., Shi L., de Carvalho F. D., Weinstein H., Javitch J. A., McHaourab H. S. (2010) Ion/substrate-dependent conformational dynamics of a bacterial homolog of neurotransmitter:sodium symporters. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 17, 822–829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Karlin A., Akabas M. H. (1998) Substituted-cysteine accessibility method. Methods Enzymol. 293, 123–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Androutsellis-Theotokis A., Ghassemi F., Rudnick G. (2001) A conformationally sensitive residue on the cytoplasmic surface of serotonin transporter. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 45933–45938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Androutsellis-Theotokis A., Rudnick G. (2002) Accessibility and conformational coupling in serotonin transporter predicted internal domains. J. Neurosci. 22, 8370–8378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ni Y. G., Chen J. G., Androutsellis-Theotokis A., Huang C. J., Moczydlowski E., Rudnick G. (2001) A lithium-induced conformational change in serotonin transporter alters cocaine binding, ion conductance, and reactivity of Cys-109. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 30942–30947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Keller P. C., 2nd, Stephan M., Glomska H., Rudnick G. (2004) Cysteine-scanning mutagenesis of the fifth external loop of serotonin transporter. Biochemistry 43, 8510–8516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sato Y., Zhang Y. W., Androutsellis-Theotokis A., Rudnick G. (2004) Analysis of transmembrane domain 2 of rat serotonin transporter by cysteine scanning mutagenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 22926–22933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhang Y. W., Rudnick G. (2006) The cytoplasmic substrate permeation pathway of serotonin transporter. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 36213–36220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zhang Y. W., Rudnick G. (2005) Cysteine-scanning mutagenesis of serotonin transporter intracellular loop 2 suggests an alpha-helical conformation. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 30807–30813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jacobs M. T., Zhang Y. W., Campbell S. D., Rudnick G. (2007) Ibogaine, a noncompetitive inhibitor of serotonin transport, acts by stabilizing the cytoplasm-facing state of the transporter. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 29441–29447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bulling S., Schicker K., Zhang Y. W., Steinkellner T., Stockner T., Gruber C. W., Boehm S., Freissmuth M., Rudnick G., Sitte H. H., Sandtner W. (2012) The mechanistic basis for noncompetitive ibogaine inhibition of serotonin and dopamine transporters. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 18524–18534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Severinsen K., Sinning S., Müller H. K., Wiborg O. (2008) Characterisation of the zebrafish serotonin transporter functionally links TM10 to the ligand binding site. J. Neurochem. 105, 1794–1805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kristensen A. S., Larsen M. B., Johnsen L. B., Wiborg O. (2004) Mutational scanning of the human serotonin transporter reveals fast translocating serotonin transporter mutants. Eur. J. Neurosci. 19, 1513–1523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Magnani F., Tate C. G., Wynne S., Williams C., Haase J. (2004) Partitioning of the serotonin transporter into lipid microdomains modulates transport of serotonin. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 38770–38778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Scanlon S. M., Williams D. C., Schloss P. (2001) Membrane cholesterol modulates serotonin transporter activity. Biochemistry 40, 10507–10513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hong W. C., Amara S. G. (2010) Membrane cholesterol modulates the outward facing conformation of the dopamine transporter and alters cocaine binding. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 32616–32626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Penmatsa A., Wang K. H., Gouaux E. (2013) X-ray structure of dopamine transporter elucidates antidepressant mechanism. Nature 503, 85–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Schicker K., Uzelac Z., Gesmonde J., Bulling S., Stockner T., Freissmuth M., Boehm S., Rudnick G., Sitte H. H., Sandtner W. (2012) Unifying concept of serotonin transporter-associated currents. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 438–445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Koldsø H., Noer P., Grouleff J., Autzen H. E., Sinning S., Schiøtt B. (2011) Unbiased simulations reveal the inward-facing conformation of the human serotonin transporter and Na+ ion release. PLoS Comput. Biol. 7, e1002246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rudnick G. (1977) Active transport of 5-hydroxytryptamine by plasma membrane vesicles isolated from human blood platelets. J. Biol. Chem. 252, 2170–2174 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ramamoorthy S., Bauman A. L., Moore K. R., Han H., Yang-Feng T., Chang A. S., Ganapathy V., Blakely R. D. (1993) Antidepressant- and cocaine-sensitive human serotonin transporter: molecular cloning, expression, and chromosomal localization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 2542–2546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Humphreys C. J., Wall S. C., Rudnick G. (1994) Ligand binding to the serotonin transporter: equilibria, kinetics, and ion dependence. Biochemistry 33, 9118–9125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chang J. C., Tomlinson I. D., Warnement M. R., Ustione A., Carneiro A. M., Piston D. W., Blakely R. D., Rosenthal S. J. (2012) Single molecule analysis of serotonin transporter regulation using antagonist-conjugated quantum dots reveals restricted, p38 MAPK-dependent mobilization underlying uptake activation. J. Neurosci. 32, 8919–8929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Shi L., Quick M., Zhao Y., Weinstein H., Javitch J. A. (2008) The mechanism of a neurotransmitter:sodium symporter-inward release of Na+ and substrate is triggered by substrate in a second binding site. Mol. Cell 30, 667–677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Blakely R. D., Berson H. E., Fremeau R. T., Jr., Caron M. G., Peek M. M., Prince H. K., Bradley C. C. (1991) Cloning and expression of a functional serotonin transporter from rat brain. Nature 354, 66–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hoffman B. J., Mezey E., Brownstein M. J. (1991) Cloning of a serotonin transporter affected by antidepressants. Science 254, 579–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Gu H., Wall S. C., Rudnick G. (1994) Stable expression of biogenic amine transporters reveals differences in inhibitor sensitivity, kinetics, and ion dependence. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 7124–7130 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Chang A. S., Chang S. M., Starnes D. M., Schroeter S., Bauman A. L., Blakely R. D. (1996) Cloning and expression of the mouse serotonin transporter. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 43, 185–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Malinauskaite L., Quick M., Reinhard L., Lyons J. A., Yano H., Javitch J. A., Nissen P. (2014) A mechanism for intracellular release of Na+ by neurotransmitter/sodium symporters. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 21, 1006–1012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]