SUMMARY

Given the complexity of the nervous system and its capacity for change, it is remarkable that robust, reproducible neural function and animal behavior can be achieved. It is now apparent that homeostatic signaling systems have evolved to stabilize neural function [1-3]. At the neuromuscular junction (NMJ) of organisms ranging from Drosophila to human, inhibition of postsynaptic neurotransmitter receptor function causes a homeostatic increase in presynaptic release that precisely restores postsynaptic excitation [4]. Here we address what occurs within the presynaptic terminal to achieve homeostatic potentiation of release at the Drosophila NMJ. By imaging presynaptic Ca2+ transients evoked by single action potentials we reveal a retrograde, trans-synaptic modulation of presynaptic Ca2+ influx that is sufficient to account for the rapid induction and the sustained expression of the homeostatic change in vesicle release. We show that the homeostatic increase in Ca2+ influx and release is blocked by a point mutation in the presynaptic CaV2.1 channel, demonstrating that the modulation of presynaptic Ca2+ influx through this channel is causally required for homeostatic potentiation of release. Together with additional analyses we establish that retrograde, trans-synaptic modulation of presynaptic Ca2+ influx through CaV2.1 channels is a key factor underlying the homeostatic regulation of neurotransmitter release.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The homeostatic modulation of presynaptic neurotransmitter release has been observed in organisms ranging from Drosophila to human, at both central and neuromuscular synapses [4-6]. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying this form of synaptic plasticity are poorly understood. The Drosophila neuromuscular synapse has emerged as a powerful model system to dissect the cellular and molecular basis of this phenomenon. Forward genetic screens at this synapse have begun to identify loss of function mutations that prevent this form of neural plasticity [7-9]. Among the loss of function mutations that have been shown to block this process is a mutation in the presynaptic CaV2.1 Ca2+ channel [10]. However, these prior genetic data do not inform us regarding whether this calcium channel normally participates in homeostatic plasticity or how it might do so. It remains to be shown that a change in presynaptic Ca2+ influx through the CaV2.1 Ca2+ channel occurs during homeostatic plasticity. It is equally likely that a genetic disruption of the CaV2.1 Ca2+ channel simply occludes this form of plasticity by generally impairing calcium influx or synaptic transmission. Furthermore, if a change in Ca2+ influx occurs during homeostatic plasticity, can it be shown that this change is causally required for the observed homeostatic change in presynaptic release? Finally, if a change in presynaptic Ca2+ influx occurs, can it account for both the rapid induction of homeostatic plasticity as well as the long-term maintenance of homeostatic plasticity, which has been observed to persist for several days?

To address these outstanding questions, we probed Ca2+ influx during homeostatic plasticity by imaging presynaptic Ca2+ transients at the Drosophila NMJ. We did so by comparing wild-type controls with animals harboring a mutation in the GluRIIA subunit of the muscle-specific ionotropic glutamate receptor at the fly NMJ (GluRIIASP16; [11]). The GluRIIASP16 mutation causes a reduction in mEPSP amplitude, and induces a homeostatic increase in presynaptic release that precisely offsets the postsynaptic perturbation thereby restoring EPSP amplitudes toward wild-type levels. The GluRIIASP16 mutation is present throughout the life of the animal and, therefore, this assay reports the sustained expression of homeostatic plasticity.

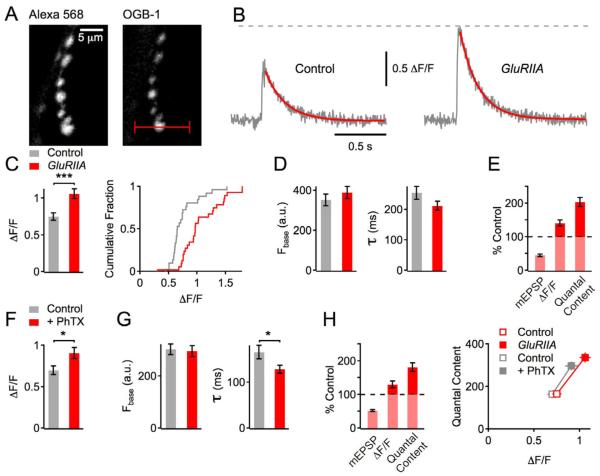

We recorded presynaptic spatially averaged Ca2+ transients by loading the presynaptic terminal with relatively low concentrations (~50 μM; see Experimental Procedures) of the Ca2+ indicator Oregon Green 488 BAPTA-1 (OGB-1, Figure 1A, right). Synapses were also filled with a red, Ca2+-insensitive reference dye to assist with the calibration of dye loading (Alexa 568; Figure 1A, left). Single action-potential evoked Ca2+ transients were measured using line scans across single type-1b boutons residing at muscle 6/7 in abdominal segments 2 or 3 (see Experimental Procedures).

Figure 1. Enhanced Presynaptic Ca2+ influx following acute or sustained disruption of postsynaptic glutamate receptor function.

(A) Confocal images of boutons filled with Alexa 568 (left) and Oregon Green 488 BAPTA-1 (OGB-1, right) synapsing onto muscle 6 of a Drosophila NMJ. The red line indicates the location of the line scan.

(B) Example traces of single AP-evoked, spatially-averaged Ca2+ transients measured by line scans of a wild-type control (left), and a GluRIIASP16 mutant synapse (right) (average of 10 scans each). The decays are fit with an exponential function (red).

(C) Average Ca2+ transient peak amplitudes of (ΔF/F, see Experimental Procedures; left), and cumulative frequency plot of ΔF/F peak amplitudes (right) of control (n=26 boutons, gray) and GluRIIASP16 (n=28 boutons, red). Note the significant (p<0.001) increase in Ca2+ transient amplitude in GluRIIASP16 mutants compared to control.

(D) Average baseline fluorescence (‘Fbase’) and decay time constant (‘τ’) of the groups introduced in (C).

(E) Average mEPSP amplitude (‘mEPSP’), Ca2+-transient peak amplitude of (‘ΔF/F’), and quantal content (EPSP amplitude/mEPSP amplitude; see Experimental Procedures) of GluRIIASP16 mutants normalized to w1118 controls. Electrophysiology data of control (av. mEPSP=0.9±0.08 mV; EPSP=52.3±1.4 mV; n=9) and GluRIIASP16 group (av. mEPSP=0.4±0.04 mV; EPSP=51.4±2.2 mV; n=7) is in part based on a separate set of experiments.

(F) Average ΔF/F peak amplitudes of control group (n=28 boutons; gray), and PhTX group (n=36 boutons, red). Note the significant (p=0.023) increase in Ca2+ transient amplitude after PhTX application.

(G) Average baseline fluorescence (‘Fbase’) and decay time constant (‘τ’) of the data set introduced in (F).

(H) Left: Average mEPSP amplitude, Ca2+-transient peak amplitude of (‘ΔF/F’), and quantal content after PhTX treatment normalized to controls. Electrophysiology data of control (av. mEPSP=0.9±0.1 mV; EPSP=48.3±1.7 mV; n=13) and PhTX group (av. mEPSP=0.47±0.03 mV; EPSP=51.2±2.6 mV; n=14) is in part based on a separate set of experiments. Right: Average quantal content (corrected for nonlinear summation; see Experimental Procedures) as a function of presynaptic Ca2+ transient peak amplitude (ΔF/F) of the indicated conditions and genotypes. Data are the same as in A – G. Data of experimental groups and control groups were collected side by side.

As exemplified in Figure 1B, the average peak amplitude of Ca2+ transients evoked by single action potentials in GluRIIASP16 mutant synapses (ΔF/F = 1.06 ± 0.06; Figure 1C, red data) was significantly larger than that observed in wild-type controls (ΔF/F = 0.75 ± 0.05; p < 0.001; Figure 1C, gray data). Throughout this study, average values are presented in figure format, and sample sizes are reported in figure legends. Averages and sample sizes of each Ca2+ imaging data set are also presented in Table S1. Data for experimental and control groups were interleaved. Baseline OGB-1 fluorescence before stimulus onset (Figure 1D, left), and fluorescence of the Ca2+-insensitive dye Alexa 568 (not shown) were not different between genotypes (OGB-1: p=0.4; Alexa 568: p=0.44), indicating similar OGB-1 loading across genotypes. Finally, the Ca2+ transient decay time constant was also not different comparing wild type and GluRIIASP16 (Figure 1D, right; p=0.19), suggesting that there are no significant differences in Ca2+ extrusion and/or Ca2+ buffering between control and GluRIIASP16 synapses.

Two additional controls were performed. There is some evidence for a functional heterogeneity between boutons of the Drosophila NMJ with distal boutons being more efficacious than proximal boutons [12, 13]. However, as shown in Figure 1C (right), we observed a relatively uniform rightward shift in the distribution of ΔF/F amplitudes indicating a uniform increase in Ca2+ influx across all boutons in GluRIIASP16 mutants. Furthermore, the increase in Ca2+ influx in GluRIIASP16 is similar regardless of whether one examines proximal versus distal boutons (Figure S1). Taken together, our data demonstrate that genetic perturbation of postsynaptic glutamate receptor function induces a sustained increase in the amplitude of presynaptic Ca2+ transients. Thus, our data provide evidence for an increase in presynaptic Ca2+ influx in response to a retrograde, trans-synaptic signal. Given the supralinear relationship between the extracellular Ca2+ concentration and release [14, 15], the magnitude of the increase in presynaptic Ca2+ influx observed here (~130% of control; Figure 1E) is expected to be a major factor underlying the observed homeostatic enhancement of transmitter release (~200% of control; Figure 1E).

Acute Perturbation of Postsynaptic Glutamate Receptor Function Increases Presynaptic Ca2+ Influx

Application of sub-blocking concentrations of the glutamate receptor antagonist Philanthotoxin-433 (PhTX, 10–20 μM) decreases mEPSP amplitudes and induces a homeostatic increase in quantal content in a time frame of minutes [10]. Therefore, we asked whether presynaptic Ca2+ influx is also modulated to account for this acute induction of synaptic homeostasis (Figure 1F – H). We find a significant increase in the amplitude of presynaptic Ca2+ transients after PhTX application for 10 min when compared to controls (Figure 1F; p=0.02). There were no apparent changes in baseline fluorescence between the two groups (Figure 1G; p=0.12), and Ca2+ transient decay kinetics were slightly, but significantly faster following PhTX treatment (Figure 1G; p=0.02), suggesting that PhTX application might also affect Ca2+ buffering and/or Ca2+ extrusion.

The magnitude of the increase in presynaptic Ca2+ influx after PhTX treatment (~123±5% of control; Figure 1H; left) is slightly less pronounced than that observed in the GluRIIASP16 mutant background (130±4% of control; Figure 1E). This is likely due to the fact that application of PhTX does not reduce mEPSP amplitudes to the same degree as the GluRIIASP16 mutation, thereby resulting in a different homeostatic pressure between the two groups (mEPSP amplitude reduction, PhTX: 52±3% of control; GluRIIASP16: 43±3% of control; Figure 1E and 1H, left). As shown in Figure 1H (right), the different degree of glutamate receptor perturbation correlates with the magnitude of the corresponding homeostatic increase in presynaptic Ca2+ influx and vesicle release, with GluRIIASP16 mutants showing a more pronounced homoeostatic increase in presynaptic Ca2+ influx and release (red) than PhTX-treated synapses (gray). In conclusion, both the sustained expression and the acute induction of synaptic homeostasis are correlated with an increase in presynaptic Ca2+ influx (Figure 1H, right). These data suggest that the modulation of presynaptic Ca2+ influx is a major target of the trans-synaptic signaling system controlling the homeostatic increase in transmitter release.

Modulation of Presynaptic Calcium Influx is Required for Synaptic Homeostasis

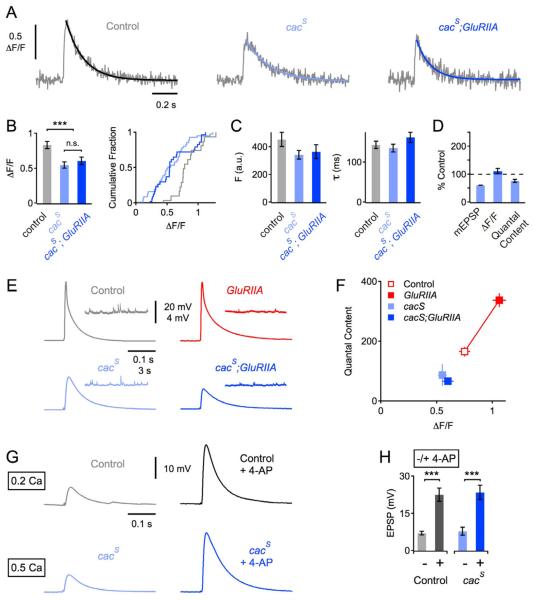

The Drosophila homologue of the CaV2.1 Ca2+ channel is the major source of presynaptic Ca2+ influx at the Drosophila NMJ [16, 17]. A point mutation (F1029I) in the sixth transmembrane domain of the third repeat of this channel, termed cacS [18], completely blocks the homeostatic modulation of neurotransmitter release when placed into the background of the GluRIIASP16 mutant [10]; see also Figure 2D – F). The blockade in synaptic homeostasis is independent of a reported change in synapse development (Reickhof et al., 2003) (Frank et al., 2006). Currently, it remains unknown whether the block in synaptic homeostasis in the cacS; GluRIIASP16 double mutant is caused by a general defect in synaptic transmission, or whether this reflects an inability to homeostatically modulate presynaptic Ca2+ influx. To distinguish between these possibilities, we examined presynaptic Ca2+ influx in cacS mutant animals and in cacS- GluRIIASP16 double mutants (Figure 2A). First, we find that the peak amplitude of Ca2+ transients measured in cacS mutants was significantly smaller than that observed in wild-type (Figure 2B, light blue and gray data; p<0.001). This is consistent with a defect in baseline transmission in the cacS mutant. Next, we show that there is no significant difference in Ca2+ transient peak amplitude between cacS mutants and cacS - GluRIIASP16 double mutant (Figure 2B, light blue and dark blue data, p=0.5), demonstrating that homeostatic modulation of presynaptic Ca2+ influx is blocked in the cacS - GluRIIASP16 double mutant. As shown in Figure 2C, there was no significant change in baseline fluorescence (p=0.69) and decay kinetics (p=0.09) between cacS and cacS- GluRIIASP16 double mutants. Importantly, defects in baseline transmission seen in cacS and altered homeostatic modulation of release are correlated with changes in presynaptic calcium influx (Figure 2D – F). In conclusion, the modulation of presynaptic Ca2+ influx through the CaV2.1 channel is necessary for the sustained expression of homeostatic plasticity in the GluRIIASP16 mutant background, because the homeostatic increase in Ca2+ influx and release (Figure 2D – F) are completely blocked by the cacS mutation.

Figure 2. A Mutation in cacophony Blocks the Homeostatic Increase in Presynaptic Ca2+ Influx and Release.

(A) Representative traces of spatially-averaged Ca2+ transients of the indicated genotypes (average of 8 – 12 scans each).

(B) ΔF/F Ca2+ transient peak amplitudes (average and cumulative frequency plot) of control (n=18 boutons; gray), cacS (n=42; light blue), and cacS; GluRIIASP16 (n=30; dark blue). The peak amplitude of cacS mutants, and cacS; GluRIIASP16 double mutants was smaller than in control (both p<0.001), and there was no significant difference in peak amplitude between cacS mutants, and cacS; GluRIIASP16 (p=0.5).

(C) Average baseline fluorescence (‘Fbase’) and decay time constant (‘τ’) of the groups introduced in (B).

(D) Average mEPSP amplitude (‘mEPSP’), Ca2+-transient peak amplitude of (‘ΔF/F’), and quantal content of cacS; GluRIIASP16 double mutants normalized to cacS.

(E) Example EPSP traces and mEPSP traces of the indicated genotypes.

(F) Average quantal content as a function of presynaptic Ca2+ transient peak amplitude (ΔF/F) of the indicated genotypes. All data were collected at an extracellular Ca2+ concentration of 1 mM. Ca2+ imaging data is the same as introduced in (A – C), and electrophysiology data is in part based on a separate set of experiments (control: n=9; cacS: mEPSP=0.63±0.07 mV; EPSP=29.9±3.4 mV, n=4; cacS; GluRIIASP16: mEPSP=0.39±0.01 mV; EPSP=19.5±1.9 mV, n=7; GluRIIASP16: n=7; control and GluRIIASP16 data are also shown in Figure 1H). Note the supralinear relationship between quantal content and presynaptic Ca2+. (A linear fit to the logarithmized data gave a slope of 2.2; not shown), and the complete block of the homeostatic increase in presynaptic Ca2+ influx and release in cacS; GluRIIASP16 double mutants (dark blue).

(G) Representative EPSPs of the indicated genotypes under control conditions (left), and in the continued presence of 50 mM of the K+-channel blocker 4-AP (right) at the indicated extracellular Ca2+ concentrations (in mM).

(H) Average peak EPSP amplitudes in the absence (−) and presence (+) of 4-AP. Wild-type (−): n=10, wild-type (+): n=9; cacS (−): n=15; cacS (+): n=13. Note the difference in extracellular Ca2+ concentration between cacS (0.5 mM) and wild type (0.2 mM). There was no significant difference in the 4-AP-induced increase in EPSP amplitude between cacS and control (p=0.66).

Evidence that the cacS Point Mutation Renders the CaV2.1 Channel Insensitive to Retrograde Homeostatic Signaling

We have shown that a single amino acid substitution within a transmembrane domain of CaV2.1 channel renders this channel unable to participate in homeostatic plasticity. What does the cacS point mutation in CaV2.1 do to prevent the homeostatic modulation of presynaptic Ca2+ influx? One possibility is that this mutation directly affects the Ca2+ channel, either by keeping individual channels from passing more Ca2+, or by affecting the number of channels that are opened by a presynaptic action potential. Alternatively, this mutation could render the channel unable to respond to the retrograde homeostatic signal. First, changing the extracellular Ca2+ concentration increases presynaptic transmitter release in the cacS mutant (Frank et al., 2006). Thus, a given number of cacS mutant channels can pass more Ca2+ in response to an increased driving force for Ca2+. Next, we explore whether the cacS mutation prevents the modulation of calcium influx in response to action-potential broadening. We demonstrate that presynaptic action potential broadening in the presence of the potassium channel blocker 4-amino-pyridine is able to potentiate release in cacS mutants to a degree that is similar to wild type (Figure 2G, H; p=0.66; note that extracellular calcium concentration is adjusted to normalize baseline release in this experiment). Thus, it appears possible to modulate the number and/or function of cacS mutant channels that open during an action potential. Since other forms of modulation, such as presynaptic action-potential broadening, can achieve an increase in release in cacS mutant channels, it appears that the cacS mutation might specifically render this channel insensitive to the homeostatic signaling system.

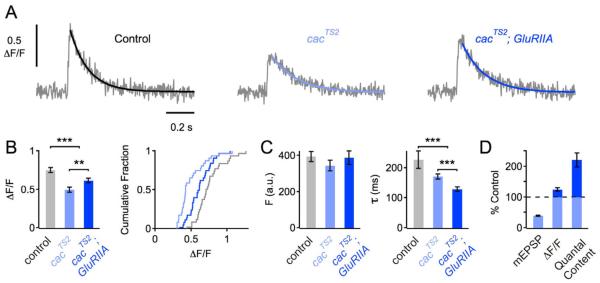

Voltage-gated Ca2+ channel function is regulated by changes in the intracellular Ca2+ concentration [19]. It remains possible that a decrease in Ca2+ influx itself prevents the capacity of the cacS mutant channel to undergo modulation. Therefore, we examined an independent point mutation in the CaV2.1 Ca2+ channel, the cacTS2 mutation (P1385S), which resides in the intracellular C-terminal domain [20, 21]. This mutation, at room temperature, causes a significant decrease in baseline synaptic transmission but does not block synaptic homeostasis when placed in the GluRIIASP16 mutant background (Frank et al., 2006). In agreement with a previous study, we show that the cacTS2 mutation diminishes presynaptic Ca2+ influx at room temperature (Figure 3A, B) [22] to an extent that is similar to that observed in cacS. Next, we demonstrate a statistically significant increase in presynaptic Ca2+ influx comparing cacTS2 with cacTS2 - GluRIIASP16 double mutants (Figure 3B; p=0.007). As shown in Figure 3C, there was no significant change in baseline fluorescence between cacTS2 mutants and cacTS2 - GluRIIASP16 double mutants (p=0.38). However, Ca2+ transients decayed significantly faster in cacTS2 - GluRIIASP16 double mutants compared to cacTS2 mutants (Figure 3C; p<0.001), indicating that Ca2+ buffering and/or extrusion might be changed in cacTS2 - GluRIIASP16 double mutants. The increase in presynaptic Ca2+ influx in cacTS2 - GluRIIASP16 compared to cacTS2 was paralleled with a corresponding increase in release (Figure 3D). Note that the increase in Ca2+ influx seen in cacTS2 - GluRIIASP16 mutants remains below wild-type levels, whereas the homeostatic increase in release is similar to wild type. This suggests that other mechanisms participate in the homeostatic potentiation of release (Figure S2). Together, these data demonstrate that a defect in baseline Ca2+ influx does not necessarily block the capacity for a homeostatic increase in Ca2+ influx. Regardless of how the cacS mutation ultimately blocks the homeostatic change in Ca2+ channel function and/or number, these data directly link the modulation of presynaptic Ca2+ influx through the presynaptic CaV2.1 Ca2+ channel to the homeostatic signaling system that controls presynaptic release.

Figure 3. Homeostatic Increase in Ca2+ Influx at cacTS2 Mutant Synapses.

(A) Representative traces of spatially-averaged Ca2+ transients of the indicated genotypes (average of 8–12 scans each).

(B) ΔF/F Ca2+ transient peak amplitudes (average and cumulative frequency plot) of control (n=31 boutons; gray), cacTS2 (n=32; light blue), and cacTS2; GluRIIASP16 (n=32; dark blue). All data were collected at room temperature. The peak amplitudes of cacTS2 mutants, and cacTS2; GluRIIASP16 double mutants were smaller than in control (both p<0.004), and there was a significant difference in peak amplitude between cacTS2 mutants, and cacTS2; GluRIIASP16 (p=0.007). Note that cacTS2; GluRIIASP16 double mutants display normal synaptic homeostasis at room temperature (see D) (Frank et al., 2006).

(C) Average baseline fluorescence (‘Fbase’) and decay time constant (‘τ’) of the groups introduced in (B).

(D) Average mEPSP amplitude (‘mEPSP’), Ca2+-transient peak amplitude of (‘ΔF/F’), and quantal content of cacTS2; GluRIIASP16 double mutants normalized to cacTS2. Electrophysiology data is based on a separate set of experiments (control: n=13; cacTS2: mEPSP=1.0±0.01 mV; EPSP=42.9±1.8 mV, n=15; cacTS2; GluRIIASP16: mEPSP=0.44±0.03 mV; EPSP=43.6±4.0 mV, n=8).

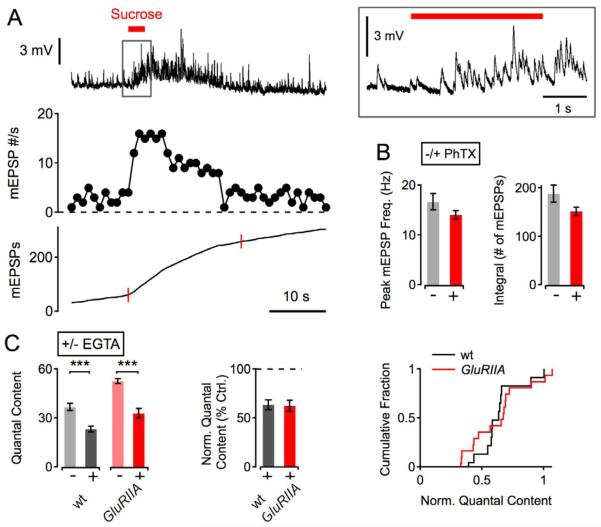

No Change in the Sucrose-Sensitive Vesicle Pool and EGTA-Sensitivity of Release During Synaptic Homeostasis

The homeostatic increase in transmitter release could involve changes in addition to increased Ca2+ influx. There is evidence that homeostatic enhancement of release at the Drosophila NMJ is not paralleled by changes in the Ca2+ cooperativity of release [10, 11]. However, in principle, a change in the primed/docked vesicle pool could contribute to the homeostatic increase in release. To probe the primed/docked vesicle pool during synaptic homeostasis, we investigated the vesicle pool that can be released by application of hypertonic saline [23, 24]. As shown in Figure 4A, application of hypertonic solution (420 mM sucrose for 3 s) elicited an increase in mEPSP rate that decayed exponentially. The sucrose challenge-induced increase in mEPSP frequency (Figure 4B, left), and the total number of vesicles released (Figure 4B, right) were similar comparing control synapses with synapses treated with PhTX (both p>0.05). Thus, the induction of synaptic homeostasis does not correlate with a measurable increase in the size of the sucrose-sensitive vesicle pool. This finding is in good agreement with previous data showing that homeostatic potentiation of release is not accompanied by major changes in the number of morphologically identified active zones quantified by immunostaining against the active zone component Bruchpilot [10, 25].

Figure 4. Sucrose-Sensitive Vesicle Pool and EGTA-Sensitivity of Release During Synaptic Homeostasis.

(A) Example mEPSP trace (top), mEPSP frequency (mEPSP #/s; middle), and mEPSP integral (bottom; red bar) of a wild-type synapse during a sucrose challenge (top; 420 mM sucrose for 3 s). A magnified version of the mEPSP trace around the time of sucrose application is shown on the right (gray box). The mEPSP integral that was considered for analysis (a 20 s interval beginning at the onset of sucrose application) is highlighted by red marks (bottom trace).

(B) Average peak mEPSP frequency (left) and mEPSP integral (right) of PhTX-treated synapses (n=15; red), and controls (n=8; gray). There was no significant difference in both parameters between PhTX-group and control group (both p>0.05).

(C) Average quantal content of wild-type (‘wt’) and GluRIIASP16 mutants under control conditions (‘− EGTA’), and after EGTA-AM incubation (25 mM EGTA-AM for 10 minutes; see Experimental Procedures; ‘+ EGTA’). Average quantal content after EGTA incubation normalized to control (‘Norm. Quantal Content’, middle), and cumulative frequency histogram of normalized quantal content (right) in the absence (−) and presence (+) of EGTA-AM. wt (−): n=13; wt (+): n=12; GluRIIASP16 (−): n=15; GluRIIASP16 (+): n=18. EGTA application induced a similar decrease in quantal content in GluRIIASP16 mutants and control (p=0.91).

Another possibility is that a decrease in the average distance between releasable vesicles and the Ca2+ channels could participate in the homeostatic potentiation of presynaptic release. To test this possibility, we assayed the effects of the slow Ca2+ buffer EGTA on release, comparing wild type with GluRIIASP16 mutant animals. Because of the relatively slow Ca2+-binding rate of EGTA [26], EGTA is expected to primarily affect the release of vesicles that are located at a significant distance from the sites of Ca2+ influx. Therefore, if the homeostatic enhancement of release is associated with increased coupling of vesicles closer to the Ca2+-channel, then this should be reflected by a decrease in the EGTA sensitivity of release. As shown in Figure 4C, the relative decrease in quantal content induced by EGTA-AM application (25 mM for 10 minutes) was similar between GluRIIASP16 mutants (62±5% of control; Figure 4C) and wild type (63±5% of control; Figure 4C; p=0.92). This implies that a change in Ca2+ sensitivity due to a decreased average distance between releasable vesicles and Ca2+ channels does not underlie the homeostatic increase in release.

If the homeostatic enhancement of release is solely due to a change in presynaptic Ca2+ influx without concomitant changes in the number of releasable vesicles, then repetitive stimulation of homeostatically-challenged synapses is expected to result in more pronounced vesicle depletion. Indeed, there is evidence for increased synaptic depression in GluRIIA mutants and following PhTX application [10, 25]. However, in agreement with a recent study [25], we observed that homeostatic potentiation is paralleled by an increased number of release-ready vesicles, as assayed by the method of back-extrapolation of cumulative EPSC amplitudes during stimulus trains [27] (Figure S2). The increase in the number of release-ready vesicles detected by this assay could be a direct or an indirect consequence of the homeostatic change in presynaptic Ca2+ influx, and might help the potentiated synapse to sustain release during ongoing activity.

Work from several laboratories has provided evidence that chronic manipulation of neural activity in cultured mammalian neurons is associated with a compensatory change in presynaptic neurotransmitter release and a change in presynaptic Ca2+ influx [28, 29]. However, it remains unknown whether these homeostatic changes in release are caused by altered pre- versus postsynaptic activity and it is unclear whether a change in presynaptic calcium influx is essential for this form of homeostatic plasticity in mammalian central neurons. Ultimately, it will be exciting to determine whether the molecular mechanisms identified in Drosophila, such as those described here, will translate to mammalian central synapses.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Fly Stocks and Genetics

Drosophila stocks were maintained at room temperature. Unless otherwise noted, all fly lines were obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (Bloomington, IN, USA). The w1118 strain was used as a wild-type control.

Ca2+ Imaging

Third instar larvae were dissected and the motor axons were cut near the neuromuscular junction. The dissected preparation was incubated in ice cold, Ca2+-free HL3 containing 5 mM Oregon-Green 488 BAPTA-1 (hexapotassium salt, Invitrogen) and 1 mM Alexa 568 (Invitrogen). After incubation for 10 minutes, the preparation was washed repeatedly with ice cold HL3 for 10 – 15 minutes. Single action-potential evoked spatially-averaged Ca2+ transients were measured in type-1b boutons synapsing onto muscle 6/7 of abdominal segments A2/A3 at an extracellular [Ca2+] of 1 mM using a confocal laser-scanning system (Ultima, Prairie Technologies) at room temperature. Excitation light (488 nm) from an air-cooled krypton-argon laser was focused onto the specimen using a 60 Xobjective (1.0 NA, Olympus), and emitted light was detected with a gallium arsenide phosphide-based photocathode photomultiplier tube (Hamamatsu). Line scans across single boutons were made at a frequency of 313 Hz. Fluorescence changes were quantified as ΔF/F = (F(t)-Fbaseline)/(Fbaseline-Fbackground), where F(t) is the fluorescence in a region of interest (ROI) containing a bouton at any given time, Fbaseline is the mean fluorescence from a 300-ms period preceding the stimulus, and Fbackground is the background fluorescence from an adjacent ROI without any indicator-containing cellular structures. One synapse (4 – 12 boutons) was imaged per preparation. The average Ca2+ transient of a single bouton is based on 8 – 12 line scans. Experiments in which the resting fluorescence decreased by >15 %, and/or which had a Fbaseline > 650 a.u. were excluded from analysis. Data of experimental and control groups were collected side by side. Assuming a similar diffusion between OGB-1 and Alexa 568, the intraterminal Ca2+ indicator concentration (47±18 μM, SD) was roughly approximated by comparing the intraterminal OGB-1 and Alexa 568 fluorescence intensity with a calibration curve obtained from measuring Alexa 568 fluorescence intensity of known Alexa 468 concentrations (dissolved in HL3) in small quartz glass cuvettes (VitroCom).

Electrophysiology

Sharp-electrode recordings were made from muscle 6 in abdominal segment 2 and 3 of third-instar larvae using an Axopatch 200B or 700B amplifier (Axon Instruments), as previously described [30]. The extracellular HL3 saline contained (in mM): 70 NaCl, 5 KCl, 10 MgCl2, 10 NaHCO3, 115 sucrose, 4.2 trehalose, 5 HEPES, and 1 (unless specified) CaCl2. For acute pharmacological homeostatic challenge, larvae were incubated in Philanthotoxin-433 (PhTX; 10, or 20 μM; Sigma-Aldrich) for 10 min (Frank et al., 2006). Sucrose was bath-applied (420 mM sucrose in sucrose for 3 s; Figure 4A, B) via a glass pipette that was placed in anterior-posterior orientation at the anterior end of the synapse at muscle 6/7, similar to [24]. EGTA-AM (25 mM in HL3; Invitrogen; Figure 4C) was applied to the dissected preparation for 10 minutes. After EGTA application, the preparation was washed with HL3 for 5 min. The average single AP-evoked EPSP amplitude of each recording is based on 30 EPSPs. For each recording, at least 100 mEPSPs were analyzed to obtain a mean mEPSP amplitude value. Quantal content was estimated for each recording by calculating the ratio of mean EPSP amplitude/ mean mEPSP amplitude, and then averaging recordings across all NMJs for a given genotype. Quantal content values in Figure 1 – 3 are corrected for non-linear summation [31].

Data Analysis

Ca2+ imaging data and evoked EPSPs were analyzed using custom-written routines in Igor Pro 5.0 and 6.22 (Wavemetrics), and spontaneous mEPSPs were analyzed using Mini Analysis 6.0.0.7 (Synaptosoft). Ca2+ imaging data was acquired with Prairie View. All results are reported as average ± SEM. Statistical significance was assessed by Student’s t test, and significance levels were indicated as follows: (*) p<0.05, (**) p<0.01, (***) p<0.001.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Retrograde homeostatic signaling induces an increase in presynaptic Ca2+ influx.

A point mutation in the CaV2.1 Ca2+ channel blocks homeostatic plasticity.

Homeostatic potentiation of release requires a change in presynaptic Ca2+ influx.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a fellowship from the Swiss National Science Foundation (PBSKP3-123456/1) to M.M., and a National Institute of Health grant (NS39313) to G.W.D. We thank the members of the Davis lab for comments and discussion.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bergquist S, Dickman DK, Davis GW. A Hierarchy of Cell Intrinsic and Target-Derived Homeostatic Signaling. Neuron. 2010;66:220–234. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marder E, Goaillard J-M. Variability, compensation and homeostasis in neuron and network function. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:563–574. doi: 10.1038/nrn1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turrigiano GG, Nelson SB. Homeostatic plasticity in the developing nervous system. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:97–107. doi: 10.1038/nrn1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis GW. Homeostatic control of neural activity: from phenomenology to molecular design. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2006;29:307–323. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.061604.135751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Plomp JJ, van Kempen GT, Molenaar PC. Adaptation of quantal content to decreased postsynaptic sensitivity at single endplates in alpha-bungarotoxin-treated rats. J Physiol (Lond) 1992;458:487–499. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis GW, Bezprozvanny I. Maintaining the stability of neural function: a homeostatic hypothesis. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2001;63:847–869. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.63.1.847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frank CA, Pielage J, Davis GW. A Presynaptic Homeostatic Signaling System Composed of the Eph Receptor, Ephexin, Cdc42, and CaV2.1 Calcium Channels. Neuron. 2009;61:556–569. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.12.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dickman DK, Davis GW. The schizophrenia susceptibility gene dysbindin controls synaptic homeostasis. Science. 2009;326:1127–1130. doi: 10.1126/science.1179685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Müller M, Pym ECG, Tong A, Davis GW. Rab3-GAP Controls the Progression of Synaptic Homeostasis at a Late Stage of Vesicle Release. Neuron. 2011;69:749–762. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frank CA, Kennedy MJ, Goold CP, Marek KW, Davis GW. Mechanisms underlying the rapid induction and sustained expression of synaptic homeostasis. Neuron. 2006;52:663–677. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petersen SA, Fetter RD, Noordermeer JN, Goodman CS, DiAntonio A. Genetic analysis of glutamate receptors in Drosophila reveals a retrograde signal regulating presynaptic transmitter release. Neuron. 1997;19:1237–1248. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80415-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peled ES, Isacoff EY. Optical quantal analysis of synaptic transmission in wild-type and rab3-mutant Drosophila motor axons. Nature Publishing Group; 2011. pp. 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guerrero G, Rieff DF, Agarwal G, Ball RW, Borst A, Goodman CS, Isacoff EY. Heterogeneity in synaptic transmission along a Drosophila larval motor axon. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1188–1196. doi: 10.1038/nn1526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dodge FA, Rahamimoff R. Co-operative action a calcium ions in transmitter release at the neuromuscular junction. J Physiol (Lond) 1967;193:419–432. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1967.sp008367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jan LY, Jan YN. Properties of the larval neuromuscular junction in Drosophila melanogaster. J Physiol (Lond) 1976;262:189–214. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1976.sp011592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith LA, Wang X, Peixoto AA, Neumann EK, Hall LM, Hall JC. A Drosophila calcium channel alpha1 subunit gene maps to a genetic locus associated with behavioral and visual defects. J. Neurosci. 1996;16:7868–7879. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-24-07868.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hou J, Tamura T, Kidokoro Y. Delayed synaptic transmission in Drosophila cacophonynull embryos. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2008;100:2833–2842. doi: 10.1152/jn.90342.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith LA, Peixoto AA, Kramer EM, Villella A, Hall JC. Courtship and visual defects of cacophony mutants reveal functional complexity of a calcium-channel alpha1 subunit in Drosophila. Genetics. 1998;149:1407–1426. doi: 10.1093/genetics/149.3.1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Catterall WA. Structure and regulation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2000;16:521–555. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.16.1.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brooks IM, Felling R, Kawasaki F, Ordway RW. Genetic analysis of a synaptic calcium channel in Drosophila: intragenic modifiers of a temperature-sensitive paralytic mutant of cacophony. Genetics. 2003;164:163–171. doi: 10.1093/genetics/164.1.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kawasaki F, Collins SC, Ordway RW. Synaptic calcium-channel function in Drosophila: analysis and transformation rescue of temperature-sensitive paralytic and lethal mutations of cacophony. Journal of Neuroscience. 2002;22:5856–5864. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-14-05856.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Macleod GT, Chen L, Karunanithi S, Peloquin JB, Atwood HL, Mcrory JE, Zamponi GW, Charlton MP. The Drosophila cacts2mutation reduces presynaptic Ca 2+entry and defines an important element in Ca v2.1 channel inactivation. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;23:3230–3244. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosenmund C, Stevens CF. Definition of the readily releasable pool of vesicles at hippocampal synapses. Neuron. 1996;16:1197–1207. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80146-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marek KW, Davis GW. Transgenically encoded protein photoinactivation (FlAsH-FALI): acute inactivation of synaptotagmin I. Neuron. 2002;36:805–813. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01068-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weyhersmuller A, Hallermann S, Wagner N, Eilers J. Rapid Active Zone Remodeling during Synaptic Plasticity. Journal of Neuroscience. 2011;31:6041–6052. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6698-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith PD, Liesegang GW, Berger RL, Czerlinski G, Podolsky RJ. A stopped-flow investigation of calcium ion binding by ethylene glycol bis(beta-aminoethyl ether)-N,N’-tetraacetic acid. Anal. Biochem. 1984;143:188–195. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(84)90575-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schneggenburger R, Meyer AC, Neher E. Released fraction and total size of a pool of immediately available transmitter quanta at a calyx synapse. Neuron. 1999;23:399–409. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80789-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao C, Dreosti E, Lagnado L. Homeostatic Synaptic Plasticity through Changes in Presynaptic Calcium Influx. Journal of Neuroscience. 2011;31:7492–7496. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6636-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim SH, Ryan TA. CDK5 Serves as a Major Control Point in Neurotransmitter Release. Neuron. 2010;67:797–809. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davis GW, Goodman CS. Synapse-specific control of synaptic efficacy at the terminals of a single neuron. Nature. 1998;392:82–86. doi: 10.1038/32176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martin AR. A further study of the statistical composition on the end-plate potential. J Physiol (Lond) 1955;130:114–122. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1955.sp005397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.