Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate clinical characteristics, treatment and outcomes of patients with visual changes from giant cell arteritis (GCA) and, to examine trends over the last 5 decades.

Methods

We reviewed the medical records of a population-based cohort of GCA patients diagnosed between 1950 and 2004. The clinical, ophthalmological and laboratory features of patients with visual manifestations attributable to GCA were compared to patients without visual complications. Trends over time were examined using logistic regression modeling adjusted for age and sex.

Results

In a cohort of 204 cases of GCA (mean age 76.0 ± 8.2 years, 80% female), visual changes from GCA were observed in 47 patients (23%), 4.4% suffered complete vision loss. A higher proportion of patients with visual manifestations reported jaw claudication than patients without visual changes (55% versus 38%, p=0.04). Over a period of 55 years, we observed a significant decline in the incidence of visual symptoms due to GCA. There was a lower incidence of ischemic optic neuropathy in the 1980–2004 cohort vs 1950–1979 (6% vs 15%, p=0.03). Patients diagnosed in later decades were more likely to recover from visual symptoms (HR, 95% CI: 1.34 (1.06–1.71). Chances of recovery were poor in patients with anterior ischemic optic neuropathy or complete vision loss.

Conclusions

Incidence of visual symptoms has declined over the past 5 decades, and chances of recovery from visual symptoms have improved. However, complete loss of vision is essentially irreversible. Jaw claudication is associated with higher likelihood of development of visual symptoms.

Keywords: Giant Cell Arteritis, Vision loss, Visual manifestations, Vasculitis, Steroids, Blindness

Introduction

Giant cell arteritis (GCA) is a granulomatous large vessel vasculitis and is the most common vasculitis in western countries in the elderly age group (1). Since Horton's first description (2) of temporal arteritis in the United States, this form of systemic vasculitis has become more widely recognized, as has its potential for serious sequelae, such as blindness and death (3).

The annual incidence of GCA in a population-based cohort from Olmsted County, Minnesota, USA has been estimated around 18.9 per 100,000 people over the age of 50 years (4, 5). The highest incidence of GCA has been observed in Caucasians of North European descent (up to 30/100,000) (6). Women are affected two to three times more often than men (1, 7).

GCA affects medium and large-sized vessels with predisposition for cranial arteries (1). Cranial ischemic complications, particularly permanent visual loss due to vasculitic involvement of the posterior ciliary arteries, are the most feared aspect of giant cell arteritis (GCA)(8). Incidence of visual complications was particularly high before the introduction of corticosteroid use for GCA (35%–60%) (9–11).

Early initiation of empiric corticosteroids at onset of symptoms in patients with suspected GCA may decrease the risk of permanent vision loss (12); however it is unclear whether this strategy has modified the course of visual complications over time. We performed this population-based, historical cohort analysis evaluating visual complications in patients with GCA and examined trends over the last 5 decades.

Patients and Methods

Study design

This is a retrospective population-based cohort study performed using the resources of the Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP) medical records linkage system in Olmsted County, Minnesota (13). Population based epidemiologic research can be conducted in Olmsted County because medical care is virtually self-contained within the community, and complete (inpatient and outpatient) medical records for county residents are available for review. After approval by the Institutional Review Board, we used the resources of the REP to identify all Rochester, Minnesota, residents >18 years of age who fulfilled the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) 1990 criteria for GCA between January 1, 1950, and December 31, 2004.

Data Collection

Patient records were reviewed and details regarding demographics, clinical features at the time of GCA diagnosis, results of ophthalmological evaluation, laboratory parameters at the time of diagnosis and on subsequent visits were abstracted. Two groups of GCA patients were identified from the cohort: patients with visual manifestations attributed to GCA, and patients without visual manifestations or with vision changes deemed to be unrelated to GCA (cataract, age-related macular degeneration etc). Ophthalmologic examination records, when available, were reviewed to ascertain that the vision manifestations were related to GCA. When ophthalmic examination findings were not available, data was obtained from review of the treating physician records. Data on the entire treatment course and response to therapy were also collected. Patients were followed until migration, death or the end of the study (December 31, 2009).

We also analyzed the association between vision changes in GCA and risk of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality.

Statistical methods

Descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation, or median and interquartile range, or percentages, as appropriate) were used to describe the cohort. Baseline variables were compared in patients with GCA who developed visual manifestations to the remainder of the cohort using Chi-square tests for categorical variables and Wilcoxon rank sum tests for continuous variables. The cohort was divided into 2 time periods (those diagnosed with GCA in 1950–1979, and those diagnosed in 1980–2004), and comparison between time periods was performed using Chi-square and Wilcoxon rank sum tests.

Trends over time were analyzed using smoothing splines in logistic regression models adjusted for age and sex. Factors associated with time to resolution of visual symptoms were examined using Cox proportional hazard models. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SAS statistical software, version 9.3 (Cary, NC).

Results

Study Cohort

This study cohort included 204 patients with GCA (mean age 76.0 ± 8.2 years, 80% female), all of whom met the ACR 1990 criteria for classification of GCA. Temporal artery biopsy was positive in 92% of the 192 patients in whom it was performed. At diagnosis, 47 patients (23%) had visual manifestations attributable to GCA. Demographic characteristics and clinical features in those with visual manifestations are compared to those without visual manifestations in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical and laboratory features of patients with and without visual manifestations in a cohort of 204 patients with giant cell arteritis*

| Patients with Visual Manifestations (N=47) |

Patients without Visual Manifestations (N=157) |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age, years | 77.4 ±9.2 | 75.6 ±7.8 | 0.16 |

| Sex, females | 36 (77) | 127 (81) | 0.52 |

| Ever smoker | 17 (42) | 67 (46) | 0.62 |

| Clinical Features | |||

| Fever >100°F | 6 (13) | 33 (22) | 0.20 |

| Duration of symptoms, days, median (IQR) | 26 (7.8–44) | 24 (10–53) | 0.40 |

| Significant weight loss** | 6 (13) | 38 (24) | 0.09 |

| Fatigue | 9 (19) | 51 (33) | 0.07 |

| Headache | 29 (62) | 115 (74) | 0.10 |

| Jaw claudication | 26 (55) | 59 (38) | 0.036 |

| Scalp tenderness | 15 (33) | 62 (42) | 0.29 |

| Associated Polymyalgia Rheumatica | 10 (21) | 40 (26)8 | 0.53 |

| Neurologic Symptoms | 3 (6) | 2 (1) | 0.050 |

| Temporal tenderness on exam | 10 (28) | 42 (31) | 0.68 |

| Carotid/Subclavian bruit on exam | 1 (2) | 6 (4) | 0.54 |

| CAD before GCA diagnosis | 13 (28) | 28 (18) | 0.14 |

| Aspirin use before GCA diagnosis | 10 (24) | 5 (16) | 0.22 |

| Corticosteroid Use | |||

| Start dose CS, initial, mg | 59.6 ± 20 | 52 ± 14 | 0.030 |

| Cumulative CS dose on day 1, mg | 97.7 ± 275 | 58.3 ± 145 | 0.002 |

| Cumulative CS within 1st week, mg | 466.3 ± 534 | 398 ± 437 | 0.010 |

| Time to initiation of steroids (relative to GCA diagnosis), days | −2.0 ± 2.7 | 2.6 ± 44 | 0.010 |

| Laboratory Features | |||

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 11.9 ± 1.3 | 11.7 ± 1.4 | 0.16 |

| ESR, mm/hr | 77 ± 28 | 80 ± 31 | 0.45 |

| White blood cell count, ×103/µL | 5.4 ± 3.6 | 5.9 ± 4.4 | 0.63 |

| Hyperlipidemia before GCA diagnosis | 18 (38) | 91 (58) | 0.018 |

p-Values <0.05 shown in bold

Values in table are n (%) or mean ± SD, except where indicated

Defined as >10% body weight in 6 months

Key: IQR: Interquartile Range; CAD: Coronary Artery Disease; CS: Corticosteroids; ESR: Erythrocyte sedimentation rate

Visual Manifestations

Among the 47 patients with visual manifestations, the most common visual symptoms were blurred vision (31 patients, 66%) and diplopia (11 patients, 23%) (Table 2). Other visual manifestations included amaurosis fugax (7 patients, 15%) and partial visual field loss (9 patients, 19%). Nine patients (19%) had complete loss of vision, which was unilateral in 7 patients and bilateral in 2 patients. Ischemic optic neuropathy (ION) was the predominant ophthalmologic diagnosis (17 patients, 36%). Other diagnoses included central retinal artery occlusion (2 patients, 4%) and non-specific ophthalmologic findings such as venous congestion and retinal hemorrhages (Table 3).

Table 2.

Visual Manifestations in 204 patients with Giant Cell Arteritis in Olmsted County, MN diagnosed between 1950 and 2004 (n=47)

| Visual symptom | Number of patients (%), n=47* |

|---|---|

| Amaurosis fugax | 7 (15) |

| Diplopia | 11 (23) |

| Blurred vision | 31 (66) |

| Field loss | 9 (19) |

| Complete loss | |

| Unilateral | 7 (15) |

| Bilateral | 2 (4) |

Some patients had more than 1 symptom

Table 3.

Ophthalmologic examination findings in 47 patients with visual symptoms from Giant Cell Arteritis in Olmsted County, MN between 1950 and 2004

| Diagnosis | Number of patients (%) |

|---|---|

| Anterior ischemic optic neuropathy | |

| Unilateral | 12 (25) |

| Bilateral | 5 (11) |

| Central retinal artery occlusion | 2 (4) |

| Other unrelated findings* | 5 (11) |

| No ophthalmologic findings | 16 (34) |

| Eye exam not performed | 7 (15) |

Included venous congestion, retinal hemorrhages, choroidal sclerosis, arteriolar narrowing, external rectus weakness and 3rd nerve palsy

Treatment

The cumulative dose of corticosteroids administered on the 1st day of suspected GCA was significantly higher in patients presenting with vision changes, as compared with no vision changes (97.6 mg v. 58.3 mg, respectively; p<0.001). Steroids were also initiated earlier in this group when compared to those with no vision-related symptoms. Indeed, corticosteroids were started on an average 2 days prior to confirmed diagnosis of GCA in patients presenting with vision changes. However, in assessing time from 1st symptom suspicious for GCA to initiation of corticosteroids between the 2 groups, no significant difference was noted (Table 1). There was no difference in the cumulative dose of steroids at 1, 2 or 5 years after GCA diagnosis between those with and without vision loss (Table 4). We also did not observe an increased risk of steroid complications (including diabetes mellitus, cataracts, hip fractures, symptomatic vertebral fractures, Colles’ fracture of the wrist, avascular necrosis, bacteremia, pneumonitis, other infections, gastrointestinal bleeding, myopathy, hypertension and hyperlipidemia) among those with and without vision loss (p>0.45 for each steroid-related complication comparing patients with vision loss to those without vision loss, adjusting for age, sex and calendar year of GCA diagnosis).

Table 4.

Cumulative corticosteroid exposure in patients with GCA with and without vision manifestations

| Patients with visual manifestations (n=47) |

Patients without visual manifestations (n=157) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1-year cumulative corticosteroid dose | |||

| Mean (SD) (in gms) | 5.4 (2.7) | 5.5 (2.5) | 0.93 |

| Median (IQR) | 5.4 (3.4–6.9) | 5.4 (3.7–7.1) | |

| 2-year cumulative corticosteroid dose | |||

| Mean (SD) (in gms) | 7.0 (3.7) | 7.3 (3.8) | 0.69 |

| Median (IQR) | 7.1 (4.0–9.3) | 7.2 (4.2–10.0) | |

| 5-year cumulative corticosteroid dose | |||

| Mean (SD) (in gms) | 9.9 (6.3) | 9.3 (6.3) | 0.63 |

| Median (IQR) | 8.3 (4.8–14.3) | 8.1 (4.3–12.7) | |

Ten patients in the GCA cohort had been treated with other immunosuppressive agents, namely, methotrexate (5 patients), cyclophosphamide (2 patients) and azathioprine (5 patients); none of had visual manifestations attributable to GCA.

Prognosis

Among patients without complete loss of vision, 75% had full resolution of their symptoms within 3 months. Recovery from visual symptoms, however, was less likely in patients with complete vision loss [hazard ratio, 95% confidence interval [HR, 95% CI: 0.20 (0.06–0.63), p<0.01] when compared with blurred vision alone. Four of the 9 patients with complete loss of vision reported a slight improvement in vision after initiation of treatment, however, visual acuity testing failed to confirm an improvement except in one patient whose vision in the affected eye improved from absence of light perception to appreciation of hand movement after treatment. One patient, diagnosed in 1954, developed vision loss after the start of corticosteroids. In this patient, corticosteroids were started 7 days prior to the vision loss, at a dose of 60 mg/day. Patients with ophthalmologic diagnosis of anterior ION were less likely to have recovery of symptoms when compared to other ophthalmological diagnoses [HR, 95% CI: 0.27 (0.12–0.61), p=0.002].

In our cohort, during follow-up, 154 patients with GCA died and 26 developed acute coronary syndrome. There was no evidence of an association between vision loss and all-cause mortality (hazard ratio, 1.14; 95% CI, 0.77–1.68; p=0.53) or acute coronary syndrome (hazard ratio, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.16–1.87; p=0.34), after adjustment for age, sex and calendar year of GCA diagnosis.

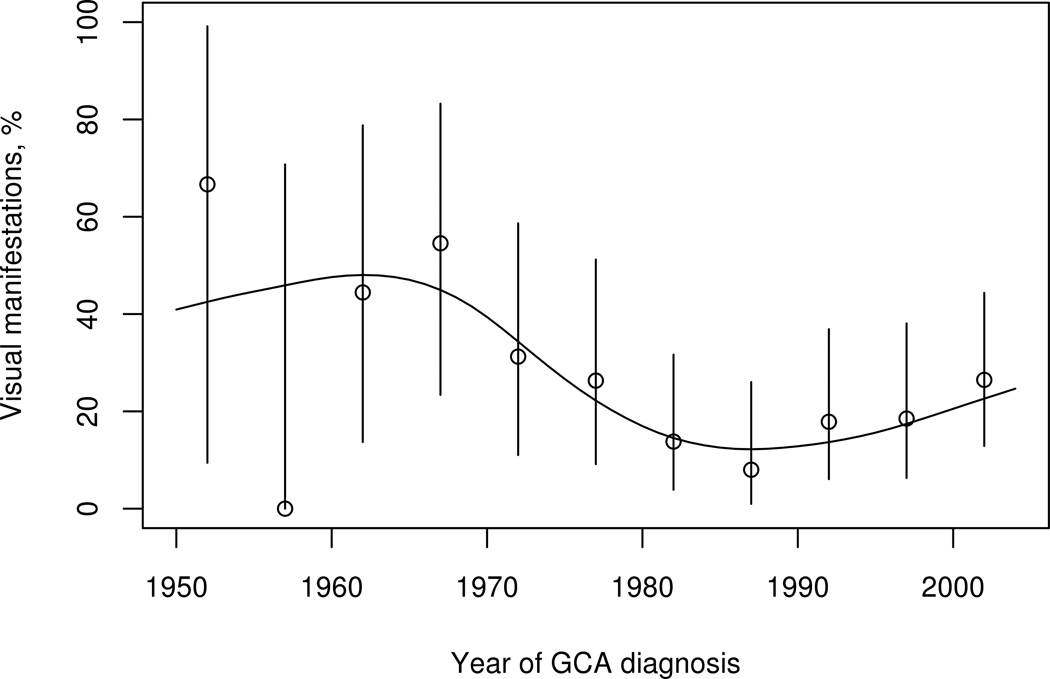

Time trends

Over the 55-year study period, a significant decline in the incidence of visual manifestations from GCA was observed (figure). Incidence of blurred vision decreased from 25% in patients diagnosed in 1950–1979 to 11% in 1980–2004 (p=0.015). Fewer patients diagnosed with GCA in 1980–2004 had complete vision loss (2%) compared to those diagnosed from 1950–1979 (9.8%), p=0.014. Incidence of ION was also less in patients diagnosed with GCA from 1980–2004 (8/143, 6%) compared to those between 1950 and 1979 (9/61, 15%), p=0.03.

Figure 1.

The incidence of visual manifestations (adjusted for age and sex) among 204 patients with giant cell arteritis, in Olmsted County, MN between 1950 and 2004, declined over time (p=0.02). Point estimate and 95% confidence interval for each 5 year time period are displayed.

Patients diagnosed with GCA in later decades were more likely to have recovery from visual symptoms [HR, 95% CI: 1.34 (1.06–1.71) per 10 year increase in calendar year, p=0.016]. In the cohort diagnosed with GCA in 1980–2004, 80% of patients with visual symptoms had resolution within 3 months of diagnosis, compared to 68% in patients diagnosed in earlier years (1950–1979).

Discussion

In 1950, Shick et al from Mayo Clinic reported the first use of corticosteroids in GCA (14). Much experience has been gained since then in the treatment of GCA with corticosteroids, but the potential impact of treatment on the course of vision loss in GCA, the most feared complication of this form of vasculitis, is not well explored.

This is the first report describing incidence and trends in visual manifestations in patients with GCA over a long period, spanning 55 years, beginning shortly after the introduction of corticosteroids for treatment of GCA (14) and extending to the current era. We found a decline in visual complications from GCA over the decades. The overall incidence of blurred vision decreased from 25% (1950–1979) to 11% (1980–2004), and only 2% of patients diagnosed with GCA in recent decades had complete vision loss, as compared to 9.8% patients diagnosed from 1950–1979. Moreover, patients diagnosed with GCA in later decades were more likely to have recovery from visual symptoms; in the cohort diagnosed with GCA in 1980–2004, 80% of patients with visual symptoms had resolution within 3 months of diagnosis, compared to 68% in patients diagnosed in earlier years (1950–1979). This may be due to increased awareness of the disease and its potential for causing permanent blindness, earlier diagnosis and timely initiation of treatment, reflected in the in early and higher dose corticosteroid use in patients with visual symptoms in this cohort. Recovery from some visual complications has become more likely in the recent decades.

Studies prior to corticosteroid use showed incidence of visual manifestations as high as 35–60% (9–11). There appears to be a decline in this complication of GCA (Table 5); since the initial use of corticosteroids for GCA in early 1950s, visual morbidity has decreased significantly (15, 16). In cohorts that have included patients after 1980, visual manifestations have been described in up to 22% patients, which is significantly less than that observed older reports (16–18). In the current study 23% of our patients had vision changes secondary to GCA. Further reduction in vision changes seems to have plateaued since the 1980s (figure), likely reflecting the widespread adoption of corticosteroid use by mid 1980s.

Table 5.

Summary of previous reports showing a declining trend in visual manifestations in patients with GCA over the years

| Study | Total number of patient in cohort |

Years studied | 1950–1969 | 1970–1990 | 1991–2005 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % of patients with visual manifestations (n/total)* | |||||

| Nesher (36) | 144 | 1960–1977, 1980–1992 | 47 (22/47) | 20 (19/97) | NR** |

| Gonzalez-Gay (17) | 255 | 1981–2005 | NR | 30 (17/57) | 20 (40/198) |

| Our study | 204 | 1950–2004 | 46 (12/26) | 18 (16/89) | 21 (19/89) |

Number of patients with vision changes due to GCA/Total number of patients with GCA in that cohort;

NR: Not reported

Presence of jaw claudication may be associated with an increased risk for developing vision changes in GCA (p=0.03), previous reports have been conflicting in this regard (6, 18). Gonzalez-Gay et al (6) reported a lower incidence of constitutional syndrome and higher hemoglobin values in those with visual manifestations; none of these were significantly different in the 2 groups in our patient population. Higher platelet count and lower inflammatory markers have been associated with a higher risk of irreversible visual ischemic complications by other authors (19–21). In a previous study, we had observed that up to 4% of patients with biopsy-proven GCA may have normal inflammatory markers (CRP and ESR) (22). Collectively, these findings suggest the possibility of a lower systemic inflammatory response in patients presenting with vision changes and one could argue that this lack of an inflammatory response may lead to a delay in presentation until the patient develops visual loss. It has also been suggested that acute-phase reactants like haptoglobin may promote neovascularization in patients with higher inflammatory response, hence the lower incidence of ischemic complications in this group (19). Hyperlipidemia was noted to be more frequent in patients without vision changes in our cohort (Table 1), this finding is of uncertain clinical significance. While hyperlipidemia can be associated with aortic aneurysm and/or dissection in patients with large vessel involvement (23), prior studies have shown no association between use of lipid-lowering agents and cranial complications from GCA (24, 25). We did not find any association between patients with visual changes and risk of acute coronary syndrome or all-cause mortality.

The duration of symptoms of GCA prior to diagnosis in the current study was no different in patients with and without visual manifestations, similar to other reports (19). Complete loss of vision was noted in 4% of our population with GCA compared to 7 to 16% in previous reports; this likely represents a referral bias in previous clinic-based studies (6, 16, 19, 26–28).

Interestingly, a higher dose of corticosteroids was often given to those presenting with vision changes in our cohort, and treatment was likely to be initiated earlier in this subgroup of patients than those without visual symptoms, sometimes even before temporal artery biopsy was performed, which generally reflects current clinical practice. Higher corticosteroid doses by intravenous route have been debated to be more efficacious in preventing loss of vision, studies have been contradicting in this regard; however, they may not be associated with an increased risk of drug-related ophthalmic complications (29–33).

Earlier initiation of corticosteroids is particularly important in those with vision changes since, if left untreated, GCA is associated with visual loss in the fellow eye within days in up to 50% of individuals (20). Addition of low-dose aspirin in these patients has been studied but remains contingent upon relative safety profile in individual patients (18, 34). Relative efficacy of aspirin in preventing visual complications from GCA could not be ascertained in our cohort. Endothelins have been implicated in the pathogenesis of vasculopathy associated with GCA and higher levels of endothelin receptors have been demonstrated in GCA afflicted vessels (35). It remains to be seen whether endothelin receptor blockers may have a potential role in acute management of vision changes in GCA.

Not only has the incidence of visual manifestations declined, we also noted a higher rate of recovery from visual symptoms in the more recent decades, an interesting and novel finding. In the years 1980–2004, 80% of visual symptoms resolved within 3 months compared to 68% in patients diagnosed in earlier years (1950–1979). Chances of recovery from complete loss of vision however, remain grim. Of the 9 patients with complete loss of vision in at least one eye, all were treated with systemic glucocorticoids, 4 reported a slight improvement but this could not be confirmed on objective ophthalmologic testing except marginal improvement in vision in 1 patient. Two patients diagnosed with GCA, in 1953 and 1974, had complete vision loss in both eyes. Notably, patients with a diagnosis of anterior ION were significantly less likely to recover compared to those with any other ophthalmologic diagnoses. Pathogenically, vision loss is a result of tissue ischemia due to luminal occlusion of inflamed blood vessel. The underlying pathomechanism is the formation of lumen-occlusive intimal hyperplasia, a neotissue that remains in place even in treated vasculitis. Data presented here confirm that vision loss is permanent once tissue ischemia has occurred. This finding may be of prognostic significance in counseling patients who present with changes in vision secondary to GCA and highlights the importance of an urgent ophthalmologic exam in suspected GCA.

Duration of this study and important new findings regarding factors associated with recovery in patients with GCA add significantly to our knowledge about this disease. According to the 2000 US census data, 90.3% of the Olmsted County population is white. GCA predominantly affects individuals of North European decent, but the results of this study would be generalizable to other Caucasian patients with GCA in the US. Population-based design and utilization of the REP, which allowed review of the entire individual medical record covering all inpatient and outpatient care from all of the local health care providers, add significantly to the comprehensiveness and reliability of our findings.

Primary limitation of our study is its retrospective design. In spite of very comprehensive medical records after presentation, baseline visual acuity prior to onset of visual symptoms was not available in all cases and hence, change in vision could not be objectively studied for many patients. The majority of patients with vision changes had a complete evaluation by an ophthalmologist (41/47). However, this evaluation varied over the course of this longitudinal study over 5 decades. The retrospective nature of the study also limited us in using strict objective criteria for improvement in vision after treatment initiation. For our study, we defined vision improvement based on a combination of patient self-report and physician assessment, as documented in medical records. We acknowledge that such subjective evaluation is not ideal, and propose that future prospective cohort studies on this topic utilize strictly defined objective criteria for vision changes. Additionally, while every attempt was made to confirm that vision changes were acute and clinically related to GCA, the possibility of misclassification bias cannot be completely excluded.

Implications for Clinical Practice

It is reassuring to find that the incidence of visual manifestations in GCA has significantly declined over the decades but there remains a 4% incidence of complete sight loss and 8% incidence of anterior ION in GCA, both of which signify permanence of vision loss with essentially no chance of recovery. Patients with vision changes are likely to receive earlier and higher dose of corticosteroids, which remains the most important treatment strategy. Although there has been progress over the years, clinicians must work towards avoiding loss of vision by patient education, prompt recognition of this disease and early institution of treatment. The potential psychosocioeconomic impact of vision loss in patients with GCA merits further review.

Acknowledgements

This study was made possible using the resources of the Rochester Epidemiology Project, which is supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01AG034676. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Disclosures: None of the authors had any conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Salvarani C, Cantini F, Hunder GG. Polymyalgia rheumatica and giant-cell arteritis. Lancet. 2008;372:234–245. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61077-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Horton BT, Magath TB, Brown GE. Undescribed Form of Arteritis of Temporal Vessels. Proc. Staff Meet. Mayo Clin. 1932;7:700–701. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paulley JW, Hughes JP. Giant-cell arteritis, or arteritis of the aged. Br Med J. 1960;2:1562–1567. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5212.1562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kermani TA, Schafer VS, Crowson CS, Hunder GG, Gabriel SE, Matteson EL, et al. Increase in age at onset of giant cell arteritis: a population-based study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:780–781. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.111005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salvarani C, Crowson CS, O'Fallon WM, Hunder GG, Gabriel SE. Reappraisal of the epidemiology of giant cell arteritis in Olmsted County, Minnesota, over a fifty-year period. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;51:264–268. doi: 10.1002/art.20227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gonzalez-Gay MA, Garcia-Porrua C, Llorca J, Hajeer AH, Brañas F, Dababneh A, et al. Visual manifestations of giant cell arteritis. Trends and clinical spectrum in 161 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2000;79:283–292. doi: 10.1097/00005792-200009000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Machado EB, Michet CJ, Ballard DJ, Hunder GG, Beard CM, Chu CP, et al. Trends in incidence and clinical presentation of temporal arteritis in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1950–1985. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:745–749. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Figus M, Talarico R, Posarelli C, d'Ascanio A, Elefante E, Bombardieri S. Ocular involvement in giant cell arteritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2013;31:S96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Birkhead NC, Wagener HP, Shick RM. Treatment of temporal arteritis with adrenal corticosteroids; results in fifty-five cases in which lesion was proved at biopsy. J Am Med Assoc. 1957;163:821–827. doi: 10.1001/jama.1957.02970450023007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bruce GM. Temporal arteritis as a cause of blindness; review of literature and report of a case. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1949;47:300–316. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cooke WT, Cloake PC, Govan AD, Colbeck JC. Temporal arteritis; a generalized vascular disease. Q J Med. 1946;15:47–75. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/15.57.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hayreh SS, Zimmerman B, Kardon RH. Visual improvement with corticosteroid therapy in giant cell arteritis. Report of a large study and review of literature. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2002;80:355–367. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0420.2002.800403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Melton LJ., 3rd History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Mayo Clin Proc. 1996;71:266–274. doi: 10.4065/71.3.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shick RM, Baggenstoss AH, Fuller BF, Polley HF. Effects of cortisone and ACTH on periarteritis nodosa and cranial arteritis. Proc Staff Meet Mayo Clin. 1950;25:492–494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Calamia KT, Hunder GG. Clinical manifestations of giant cell (temporal) arteritis. Clin Rheum Dis. 1980;6:389–403. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caselli RJ, Hunder GG, Whisnant JP. Neurologic disease in biopsy-proven giant cell (temporal) arteritis. Neurology. 1988;38:352–359. doi: 10.1212/wnl.38.3.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gonzalez-Gay MA, Miranda-Filloy JA, Lopez-Diaz MJ, Perez-Alvarez R, Gonzalez-Juanatey C, Sanchez-Andrade A, et al. Giant cell arteritis in northwestern Spain: a 25-year epidemiologic study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2007;86:61–68. doi: 10.1097/md.0b013e31803d1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nesher G, Berkun Y, Mates M, Baras M, Nesher R, Rubinow A, et al. Risk factors for cranial ischemic complications in giant cell arteritis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2004;83:114–122. doi: 10.1097/01.md.0000119761.27564.c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cid MC, Font C, Oristrell J, de la Sierra A, Coll-Vinent B, López-Soto A, et al. Association between strong inflammatory response and low risk of developing visual loss and other cranial ischemic complications in giant cell (temporal) arteritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:26–32. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199801)41:1<26::AID-ART4>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liozon E, Herrmann F, Ly K, Robert PY, Loustaud V, Soria P, et al. Risk factors for visual loss in giant cell (temporal) arteritis: a prospective study of 174 patients. Am J Med. 2001;111:211–217. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)00770-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salvarani C, Cimino L, Macchioni P, Consonni D, Cantini F, Bajocchi G, et al. Risk factors for visual loss in an Italian population-based cohort of patients with giant cell arteritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;53:293–297. doi: 10.1002/art.21075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kermani TA, Schmidt J, Crowson CS, Ytterberg SR, Hunder GG, Matteson EL, et al. Utility of erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein for the diagnosis of giant cell arteritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2012;41:866–871. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2011.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nuenninghoff DM, Hunder GG, Christianson TJ, McClelland RL, Matteson EL. Incidence and predictors of large-artery complication (aortic aneurysm, aortic dissection, and/or large-artery stenosis) in patients with giant cell arteritis: a population-based study over 50 years. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:3522–3531. doi: 10.1002/art.11353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmidt J, Kermani TA, Muratore F, Crowson CS, Matteson EL, Warrington KJ. Statin use in giant cell arteritis: a retrospective study. J Rheumatol. 2013;40:910–915. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.121150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Narvaez J, Bernad B, Nolla JM, Valverde J. Statin therapy does not seem to benefit giant cell arteritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2007;36:322–327. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aiello PD, Trautmann JC, McPhee TJ, Kunselman AR, Hunder GG. Visual prognosis in giant cell arteritis. Ophthalmology. 1993;100:550–555. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(93)31608-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bengtsson BA, Malmvall BE. The epidemiology of giant cell arteritis including temporal arteritis and polymyalgia rheumatica. Incidences of different clinical presentations and eye complications. Arthritis Rheum. 1981;24:899–904. doi: 10.1002/art.1780240706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Font C, Cid MC, Coll-Vinent B, López-Soto A, Grau JM. Clinical features in patients with permanent visual loss due to biopsy-proven giant cell arteritis. Br J Rheumatol. 1997;36:251–254. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/36.2.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kupersmith MJ, Langer R, Mitnick H, Spiera R, Spiera H, Richmond M, et al. Visual performance in giant cell arteritis (temporal arteritis) after 1 year of therapy. Br J Ophthalmol. 1999;83:796–801. doi: 10.1136/bjo.83.7.796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chan CC, Paine M, O'Day J. Steroid management in giant cell arteritis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85:1061–1064. doi: 10.1136/bjo.85.9.1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hayreh SS, Zimmerman B. Visual deterioration in giant cell arteritis patients while on high doses of corticosteroid therapy. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:1204–1215. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00228-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu GT, Glaser JS, Schatz NJ, Smith JL. Visual morbidity in giant cell arteritis. Clinical characteristics and prognosis for vision. Ophthalmology. 1994;101:1779–1785. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(94)31102-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hayreh SS, Biousse V. Treatment of acute visual loss in giant cell arteritis: should we prescribe high-dose intravenous steroids or just oral steroids? J Neuroophthalmol. 2012;32:278–287. doi: 10.1097/WNO.0b013e3182688218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee MS, Smith SD, Galor A, Hoffman GS. Antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy in patients with giant cell arteritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:3306–3309. doi: 10.1002/art.22141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lozano E, Segarra M, Corbera-Bellalta M, García-Martínez A, Espígol-Frigolhé G, Plà-Campo A, et al. Increased expression of the endothelin system in arterial lesions from patients with giant-cell arteritis: association between elevated plasma endothelin levels and the development of ischaemic events. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:434–442. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.105692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nesher G, Rubinow A, Sonnenblick M. Trends in the clinical presentation of temporal arteritis in Israel: reflection of increased physician awareness. Clin Rheumatol. 1996;15:483–485. doi: 10.1007/BF02229646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]