Abstract

Mathematical models to describe dose-dependent cellular responses to drug combinations are an essential component of computational simulations for predicting therapeutic responses. Here, a new model, the additive damage model, is introduced and tested in cases where varying concentrations of two drugs are applied with a fixed exposure schedule. In the model, cell survival is determined by whether cellular damage, which depends on the concentrations of the drugs, exceeds a lethal threshold, which varies randomly in the cell population with a prescribed statistical distribution. Cellular damage is assumed to be additive, and is expressed as a sum of separate terms for each drug. Each term has a saturable dependence on drug concentration. The model has appropriate behavior over the entire range of drug concentrations, and is predictive, given single-agent dose-response data for each drug. The proposed model is compared with several other models, by testing their ability to fit 24 data sets for platinum-taxane combinations and 21 data sets for various other combinations. The Akaike Information Criterion is used to assess goodness of fit, taking into account the number of unknown parameters in each model. Overall, the additive damage model provides a better fit to the data sets than any previous model. The proposed model provides a basis for computational simulations of therapeutic responses. It predicts responses to drug combinations based on data for each drug acting as a single agent, and can be used as an improved null reference model for assessing synergy in the action of drug combinations.

Keywords: dose-response, cytotoxicity, chemotherapy, cellular pharmacodynamics, computational simulations, drug synergy

INTRODUCTION

Theoretical simulations are increasingly accepted as an approach for investigating and predicting tumor responses to treatments including chemotherapy. For many types of cancer, available single chemotherapies have limited efficacy and drug combinations are used. The simulation of such therapies requires mathematical models to describe dose-dependent cellular responses to drug combinations. Models for drug responses provide a rational basis for predicting and optimizing therapeutic outcomes and thus have the potential to reduce the time and costs involved in drug development.

To be useful, such a model should satisfy several requirements. Firstly, the model should be able to predict the response (S, survival fraction of cells relative to controls) to any combination of drug doses, based on experimental data for a limited number of cases. This should ideally include the ability to predict responses to combinations based only on dose-response data for the drugs when used as single agents. Secondly, the model should behave appropriately when extrapolated beyond the range of available experimental data. Models involving polynomial data fits, for example, should be avoided as such functions may change sign outside the range of the fitted data, yielding unrealistic responses (1). Thirdly, the model should reduce to appropriate dose-response characteristics in the case of each drug acting as a single agent. This requirement is not satisfied by the Chou-Talalay multiple inhibitor model (2), for example. Fourthly, the model should not be over-parameterized: the number of unknown parameters should not be too large, so that the parameters can be identified based on the amount of data that is typically collected during in vitro combination cytotoxicity studies.

Cellular responses to single and multiple agents under a range of doses and dosing schedules involve many complexities and interactions. Any theoretical model represents a simplification of the actual situation. Moreover, the experimental data are always limited in number and subject to experimental error. Therefore, the predictions of any model must be regarded as approximations whose validity depends on the size and quality of the data sets on which they are based. Despite these limitations, theoretical models for responses to multiple drugs provide a valuable framework for integrating available experimental data and for developing predictive simulations.

Previous analyses of responses to drug combinations have frequently utilized the concept of 'synergy,' which is considered to occur when the response to a drug combination exceeds what would be expected based on the separate effects of the drugs. Any test for synergy must compare the observed survival with the prediction of a null reference model that gives the expected survival based on responses to each drug acting as a single agent. Greco et al. (3) observed that null reference models based on plausible cellular mechanisms can give widely varying predictions for responses to combinations, and therefore result in very different conclusions regarding synergy. Therefore, the choice of a null model is a fundamental difficulty in testing for synergy. One way to address this problem is to choose as the null reference a model that is based on biologically reasonable assumptions and that represents as closely as possible a wide range of available data on responses to combinations. Systematic deviations from such a model are therefore more likely to represent genuine synergy and not merely an artifact of the chosen null model.

Several predictive models for responses to drug combinations have been proposed. Those considered here are the fractional product method of Webb (4), the Syracuse and Greco (5, 6) model and the White et al. (1) mixture model. In addition, several authors have developed theories for testing synergy of drug combinations. Here, the null reference models derived from the synergy theories of Steel and Peckham (7) and Chou and Talalay (2) are considered. The details of these models are discussed below (Methods) and their mathematical forms are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Previous and present models for responses to combinations of two drugs. S is the survival relative to controls, C1 and C2 are the concentrations of the drugs, and and denote the concentrations at 50% survival for each drug acting as a single agent.

| Model | Equations | Explicit / implicit | Number of parameters | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Webb or fractional product method (4) with Hill equation, with saturation | Explicit | 6 | ||

| Webb or fractional product method (4) with Hill equation, without saturation | Explicit | 4 | ||

| Isobologram method (7) with Hill equation | Implicit | 4 | ||

| Chou-Talalay multiple inhibitor model (2) | Explicit | 3 | ||

| Chou-Talalay multiple inhibitor model with interaction (2) | Explicit | 3 | ||

| Syracuse-Greco model (5, 6) | Implicit | 5 | ||

| Syracuse-Greco model with interaction (5) | Implicit | 6 | ||

| White et al. model (1) |

where , , B = δ210x + δ220y, log10D50 = xy(δ310x + δ320y + δ3120xy). |

Explicit | 9 | |

| Present model, with saturation | where | Explicit | 8 | |

| Present model without saturation | where | Explicit | 6 |

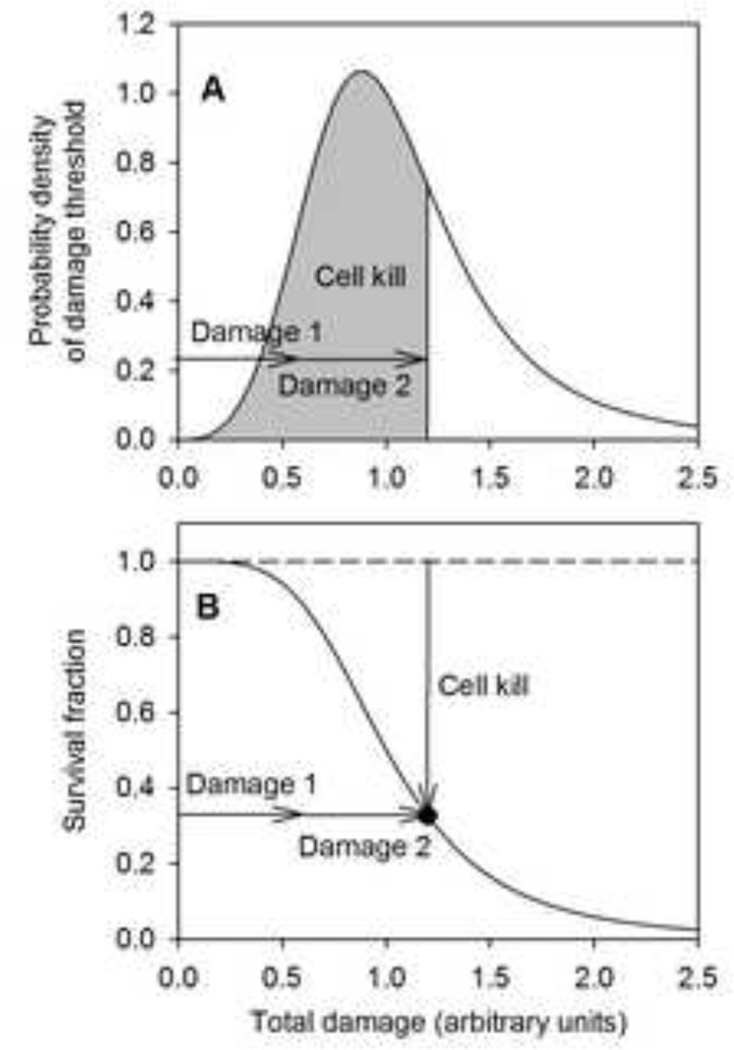

An approach for developing pharmacodynamic models was introduced by El-Kareh and Secomb (8) based on the concept of 'cellular damage.' In this approach, any given treatment is assumed to result in a certain amount of damage to all treated cells. Each cell is assumed to survive unless the damage exceeds a threshold, which has a random distribution within the cell population (Figure 1A). As a consequence, survival fraction S (relative to controls) is a decreasing, generally sigmoidal function of damage (Figure 1B). This approach can be extended naturally to the case of multiple mechanisms of cell kill, by expressing the damage as the sum of terms representing the damage resulting from each separate mechanism. The resulting model for cell kill was termed the 'additive damage' model (9) and was applied to describe the cellular response to drugs (doxorubicin and paclitaxel) for which two mechanisms contributed to cell kill. The concept of cumulative damage resulting in cell death when a threshold is reached has previously been applied in multi-hit models of radiobiological target theory (10, 11); the generalization of Rai and van Ryzin (12) allowed the number of ‘hits’ (the measure analogous to cellular damage) to be a continuous variable.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of additive damage model. A. The threshold of total damage required to kill a cell is distributed in the cell population according to a probability density function. Total damage is the sum of the damages resulting from each treatment. The area under the curve corresponding to the total damage represents the fractional cell kill. B. Survival fraction (relative to controls) as a function of total damage is given by one minus the cumulative frequency distribution of cell damage.

The goal of this study is to develop a new additive damage model for cellular responses to anticancer drug combinations and to compare it with existing models using literature data sets for such responses. The comparison is made based on the ability of each model to describe a panel of dose-response data sets obtained from the literature for a variety of drug combinations. The quantitative measure of model performance used is the Akaike Information Criterion, a statistical tool for model selection that balances the benefit of reducing the deviation from data against the disadvantage of an increased number of parameters (1). Data obtained with fixed dosing schedules are considered, and effects of alterations in schedule are not represented in the models. Most published dose-response data sets for drug combinations are for a fixed schedule, as are most previous mathematical models.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Formulation of the additive damage model

The additive damage model (8, 9) is based on the following key assumptions. (i) Survival of a cell drug exposure depends on whether the 'cellular damage' exceeds a threshold value for that cell. (ii) The threshold value of damage for cells in a population follows a statistical distribution, reflecting variations in individual cellular responses. (iii) Cellular damage can be expressed as a sum of terms, each depending on the dose of one drug.

According to assumptions (i) and (ii), the survival fraction S in a population is given as a function of damage D by one minus the cumulative probability distribution of damage thresholds, as illustrated in Figure 1. Equivalently, the negative derivative of S with respect to D is the probability density function for the threshold. This decreasing function typically has a sigmoidal shape and is represented in the present study by a Hill function

| (1) |

where n is a parameter describing the steepness of the cell line’s response. As this exponent increases, the survival curve as a function of damage becomes steeper, corresponding to a narrower distribution of the threshold for cell kill.

The Hill equation provides a good fit to most observed dose-response behavior (13) and is therefore a natural choice for this function. It has the advantage that its inverse function can be represented by a simple algebraic function, which facilitates computations. A disadvantage, however, is that its derivative (the probability density) becomes unbounded as damage goes to zero if the Hill exponent n is less than one, as can occur in some cases.

An alternative choice for the distribution of thresholds is the lognormal distribution (9). In this version of the model, the Hill function, Equation 1, is replaced with a cumulative log-normal function:

| (2) |

Here, erfc is the complementary error function and h is a parameter describing the steepness of the response. This distribution avoids the disadvantage noted above. Any lognormal function can be closely approximated numerically by a Hill function, and vice versa. However, the cumulative lognormal distribution function cannot be explicitly inverted and involves a special function; computations using this distribution are more difficult and time-consuming as a result. Both forms were considered, but results are presented only for the Hill form.

The cellular damage resulting from each drug is assumed to have a power-law dependence on the concentration of a critical intracellular target-bound species formed from the drug, through processes such as cellular uptake, binding, metabolism and transport to compartments within the cell. These critical species are the drug species leading to cell kill. Thus, for exposure to two drugs at extracellular concentrations C1 and C2, with a fixed schedule of administration, cellular damage is defined by:

| (3) |

where and are proportional to the concentrations of the target-bound species formed from drugs 1 and 2, respectively. A multiplicative constant in each term is omitted here, to avoid redundancy in the final equations. It is assumed that each drug has one dominant species contributing to cell kill; in the event that there is a second species, an additional analogous term can be added (8, 9). The exponents m1 and m2 reflect the possibly nonlinear kinetics of intracellular transport, reaction and target binding for the species that dominate cell kill.

The concentration of the target-bound species is assumed to depend on extracellular concentration C1 according to , and similarly for . The additive damage model then gives

| (4) |

The parameters a1 and a2 represent the sensitivity of the total damage to each drug dose. This equation allows for the possibility of saturation of cellular uptake, binding, or metabolism. The target-bound concentrations approach finite limits at high drug doses: as C1 → ∞ and as C2 → ∞. Equations 1 and 4 define a 7-parameter model. For some drugs and experimental conditions, saturation effects are negligible, and a reduced model can be used. For example, if neither drug shows saturation, cellular damage is given by:

| (5) |

Equations 1 and 5 define a 5-parameter model. If data with varying exposure times are available, it may be possible to derive more specific kinetic equations for the formation of and from C1 and C2, but such data are rarely available for drug combinations. All data sets considered in this study have fixed exposure times, and the generic approach described above was used.

The additive damage model can readily be generalized to more than two drugs or drug action mechanisms. For exposure to drugs 1,2,…,M at constant extracellular concentrations C1, C2, …, CM and for a fixed schedule of administration, cellular damage is given by:

| (6) |

where the parameters ai represent the sensitivity of cell damage to the concentration of drug i and the parameters mi allow the model to represent variations in the heterogeneity of cellular responses to each drug. The parameters si represent the level at which the damage Di in response to drug i saturates. For some drugs, saturation effects are negligible and cellular damage is given by:

| (7) |

Whether it is warranted to include saturation effects depends on the extent of the data set. All drugs show saturation effects when a sufficiently wide range of concentration values is considered, but this may occur beyond the range of clinical significance, as for the platinum drugs (9). Using a reduced model without saturation parameters gives a poorer fit in general but reduces the number of parameters. The AIC can be used to determine whether a data set justifies use of the model with saturation.

Testing model fit to data

To compare the performance of this and other models when applied to experimental data sets, the corrected Akaike Information Criterion (14) is used:

| (8) |

where N is the number of points in the data set, p is the number of model parameters, and and are the survival fractions for the nth data point as observed and as predicted by the model under consideration. A model with higher AICc is considered superior. The AIC is a widely used quantitative tool for model selection. AICc improves on the original AIC for small data sets, and gives essentially the same result as the original AIC for large data sets.

Testing for drug interaction

A combination index CIn is defined for each data point n:

| (9) |

where is the survival fraction predicted based on the additive damage model fitted to the data set. Here CIn < 1 indicates a synergistic interaction, CIn > 1 indicates antagonism, and CIn = 1 is neutral.

Previous models

The additive damage model was compared with previous models with regard to its ability to fit available data on cellular responses to drug combinations. The mathematical forms of all the models considered are given in Table 1. The models are described as explicit if survival can be written as a mathematically explicit function of the drug concentrations. In the fractional product method of Webb (4), cell survival for a drug combination is assumed to be the product of the survivals for the individual treatments. This model does not assume a specific form for the cytotoxicity relation for each drug acting as a single agent. To obtain a predictive model, the dependence of survival fraction on the concentration of each drug acting alone is here assumed to be given by a Hill function (15), which gives a good fit to most dose-response curves for single agents. This results in a 4-parameter model. The inclusion of saturable responses to each drug results in an alternative, 6-parameter model. Two versions of the Syracuse and Greco (5, 6) model are considered. In the first version, their 'additive' model, the parameter α is set to zero, giving a 5-parameter model. In the second version, their model 'with interaction,' α is allowed to vary as a sixth parameter. In these models, survival is defined implicitly as the solution of a nonlinear equation. The 9-parameter model of White et al. (1) gives survival as an explicit function of the drug concentrations.

Theoretical analyses of drug synergy must include or imply 'null' models, i.e. models of response in the absence of synergy. In the null model of the isobologram method (7), the pairs of doses for a given survival fraction are assumed to lie on a straight line in the c1–c2 plane. As in the case of the Webb (4) model, this model does not assume a particular cytotoxicity relationship for each drug, and a Hill function is assumed here, resulting in an implicit 4-parameter model. This model is identical to the Syracuse-Greco (5, 6) model if the parameters Scon and B are set to their nominal values Scon = 1 and B = 0, representing complete survival at zero dose and zero survival in the high-dose limit. Chou and Talalay (2) proposed two 'multiple inhibitor' models, one of which includes an 'interaction' term. Both are explicit 3-parameter models. The combination index method proposed by Chou and Talalay (16) reduces to the Steel-Peckham isobologram model (7) when the combination index is set to 1, corresponding to the case of 'additivity.'

The Chou-Talalay constant-ratio combination index model (17), another widely-used synergy test, could not be used in this comparison study because it requires a data set where multiple points are taken with the two drugs at the same ratio. Only one of the literature data sets used here satisfies that requirement. Conceptually, the Chou-Talalay constant-ratio combination index model is not different from the standard Chou-Talalay combination index model, but mathematically it can be shown that the two lead to somewhat different equations.

Several of the models contain terms involving (S−1 −1) raised to a non-integer power, and cannot be used for data sets where some values of S are greater than or equal to 1. In such cases, all values of S ≥ 1 were replaced by S = 0.999999.

Collection of experimental data

Online searches were performed with key words including “cell line” + “dose response” + “combination” + “drug,” and variants where “dose response” was replaced by “survival” and “drug” was replaced by names of widely-used chemotherapeutic agents. These searches were performed using the search service Google Images (Google Inc., Menlo Park CA), allowing rapid identification of graphical data for dose-response data for drug combinations. Such data have a distinctive visual appearance: a set of non-intersecting decreasing sigmoidal curves, each successive one having a lower y-intercept. These searches identified a number of data sets for platinum-taxane combinations and combinations of other anticancer drugs (Table 2), some in extensive clinical use and some investigational. Data sets selected had a minimum of 12 data point triples (C1, C2, S), and sampled at least three different concentrations for each drug. Each data set was for a single cell line. Twenty-four suitable data sets were identified for platinum-taxane drug combinations. These included data for cisplatin/paclitaxel (18–21), cisplatin/docetaxel (18), carboplatin/paclitaxel and carboplatin/docetaxel (22). An additional 21 data sets for a variety of drug combinations were collected: 5-fluorouracil/aclarubicin hydrochloride (23); 5-fluorouracil/fleroxacin (24); 5-fluorouracil/mitomycin-C (23); acivicin/asparaginase (25); aclarubicin hydrochloride/mitomycin-C (23); cyclophosphamide and thiotepa (26); erlotinib/rapamycin (27); gemcitabine/TRA-8 (28); imatinib/rapamycin (29); trastuzumab/ZD1839 (30) (31); gemcitabine/OBP-301(32). Cell lines used for these data cells were: A549 (human lung adenocarcinoma); B2-2 (biliary tract); Ba/F-BCR/ABLWT and Ba/F-BCR/ABL T315I (variants of the Ba/F3 murine hematopoietic cell line); BT-474 (human mammary); EMT6 (mouse mammary); MBT-2 (mouse bladder carcinoma); MCF-7 (human mammary); MIA-PaCa-2 (pancreatic); NCI-H23 (lung); PK-1 and PK-8 (human pancreatic); S2-VP10 (subline of a human pancreatic SUIT-2), SK-Br-3 (human mammary); T-24 (human bladder carcinoma); TE-671 (human medulloblastoma); H322 (human lung cancer).

Table 2.

Data sets used for model comparison.

| Data set |

Cell Line | Cell type | Drug 1 | Drug 2 | Data points |

Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | A2780/CP3 | human ovarian | cisplatin | paclitaxel | 265 | (20) |

| 2 | J82 | human bladder carcinoma | cisplatin | paclitaxel | 32 | (21) |

| 3 | RT4 | human bladder carcinoma | cisplatin | paclitaxel | 32 | (21) |

| 4 | UT-OC-3 | human ovarian carcinoma | carboplatin | docetaxel | 20 | (22) |

| 5 | UT-OC-3 | human ovarian carcinoma | carboplatin | paclitaxel | 20 | (22) |

| 6 | UT-OC-4 | human ovarian carcinoma | carboplatin | paclitaxel | 20 | (22) |

| 7 | CAOV-3 | human ovarian carcinoma | cisplatin | docetaxel | 20 | (18) |

| 8 | SK-OV-3 | human ovarian carcinoma | cisplatin | paclitaxel | 20 | (18) |

| 9 | UT-OC-1 | human ovarian carcinoma | cisplatin | paclitaxel | 20 | (18) |

| 10 | SK-OV-3 | human ovarian carcinoma | carboplatin | docetaxel | 19 | (22) |

| 11 | UT-OC-4 | human ovarian carcinoma | carboplatin | docetaxel | 19 | (22) |

| 12 | UT-OC-5 | human ovarian carcinoma | carboplatin | docetaxel | 19 | (22) |

| 13 | UT-OC-5 | human ovarian carcinoma | carboplatin | paclitaxel | 19 | (22) |

| 14 | UT-OC-4 | human ovarian carcinoma | cisplatin | docetaxel | 19 | (18) |

| 15 | UT-OC-5 | human ovarian carcinoma | cisplatin | docetaxel | 19 | (18) |

| 16 | UM-SCV-1A | human vulvar carcinoma | cisplatin | paclitaxel | 19 | (19) |

| 17 | UM-SCV-2 | human vulvar carcinoma | cisplatin | paclitaxel | 19 | (19) |

| 18 | UM-SCV-4 | human vulvar carcinoma | cisplatin | paclitaxel | 19 | (19) |

| 19 | UM-SCV-7 | human vulvar carcinoma | cisplatin | paclitaxel | 19 | (19) |

| 20 | UT-OC-4 | human ovarian carcinoma | cisplatin | paclitaxel | 19 | (18) |

| 21 | UT-OC-5 | human ovarian carcinoma | cisplatin | paclitaxel | 19 | (18) |

| 22 | UT-SCV-3 | human vulvar carcinoma | cisplatin | paclitaxel | 19 | (18) |

| 23 | UT-OC-1 | human ovarian carcinoma | cisplatin | docetaxel | 18 | (18) |

| 24 | SK-OV-3 | human ovarian carcinoma | carboplatin | paclitaxel | 17 | (22) |

| 25 | H322 | human lung cancer | Gemcitabine | OBP-301 | 40 | (32) |

| 26 | B2-2 | human biliary tract cancer | Rapamycin | Erlotinib | 36 | (27) |

| 27 | MCF-7 | human mammary carcinoma | ThioTEPA | Cyclophosphamide (4-HC) | 31 | (26) |

| 28 | MBT-2 | mouse bladder carcinoma | 5-fluorouracil (5FU) | Fleroxacin | 28 | (24) |

| 29 | T-24 | human bladder carcinoma | 5-fluorouracil (5FU) | Fleroxacin | 27 | (24) |

| 30 | MIA-PaCa-2 | human pancreatic carcinoma | TRA-8 antibody | Gemcitabine | 24 | (28) |

| 31 | S2-VP10 | human pancreatic carcinoma | TRA-8 antibody | Gemcitabine | 24 | (28) |

| 32 | EMT6 | mouse mammary carcinoma | ThioTEPA | Cyclophosphamide (4-HC) | 22 | (26) |

| 33 | TE-671 | human medullobl astoma | Acivicin | Asparaginase | 17 | (25) |

| 34 | Ba/F-BCR/ABL WT | mouse hematopoietic | Imatinib | Rapamycin | 16 | (29) |

| 35 | A549 | human lung carcinoma | ZD1839 (iressa) | trastuzumab (TRA) | 16 | (37) |

| 36 | NCI-H23 | human lung adenocarcinoma | ZD1839 (iressa) | trastuzumab (TRA) | 16 | (37) |

| 37 | BT-474 | human mammary carcinoma | ZD1839 (iressa) | trastuzumab (TRA) | 15 | (31) |

| 38 | SK-Br-3 | human mammary carcinoma | ZD1839 (iressa) | trastuzumab (TRA) | 15 | (31) |

| 39 | PK-1 | human pancreatic carcinoma | 5-fluorouracil (5FU) | aclarubicin hydrochloride (ACR) | 14 | (23) |

| 40 | PK-8 | human pancreatic carcinoma | 5-fluorouracil (5FU) | aclarubicin hydrochloride (ACR) | 14 | (23) |

| 41 | PK-1 | human pancreatic carcinoma | aclarubicin hydrochloride (ACR) | mytomycin C (MMC) | 14 | (23) |

| 42 | PK-8 | human pancreatic carcinoma | aclarubicin hydrochloride (ACR) | mytomycin C (MMC) | 14 | (23) |

| 43 | PK-8 | human pancreatic carcinoma | mytomycin C (MMC) | 5-fluorouracil (5FU) | 14 | (23) |

| 44 | PK-1 | human pancreatic carcinoma | mytomycin C (MMC) | 5-fluorouracil (5FU) | 13 | (23) |

| 45 | Ba/F-BCR/ABL T315I | mouse hematopoietic | Imatinib | Rapamycin | 12 | (29) |

Model fitting to experimental data

Data points were extracted from graphs in the source publications using the freely available PlotDigitizer software. Parameter estimation for model fits was performed using the NMinimize and FindMinimum nonlinear regression functions of the Mathematica package (Wolfram Research Inc., Champaign, IL), and in some cases were crosschecked with the fminsearch and fmincon routines of the MATLAB package (The MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA). For the explicit models, the difference between experimental and predicted survival was minimized. For the implicit models, which are formulated as a nonlinear function of S that must equal 1, the deviation of this function value from 1 when S was set equal to experimental values was minimized. For models with more than 4 parameters, careful choice of initial guesses was found to improve the chance of finding a global minimum. This was particularly noticeable for the White et al. (1) and additive damage models, which have 9 and 7 parameters, respectively, in their complete forms. In many cases with the models having more than 4 parameters, fits were initially obtained using reduced forms with some parameters omitted. These fits were then used as initial guesses and additional parameters were added incrementally. Various orders of adding parameters were explored. Often, a lower residual was found by adding parameters in a specific order. Fits were scored according to the corrected Akaike Information Criterion (AICc), Eq. 8. This criterion gives higher scores for models that result in reduced deviations between observed data and model fits, but imposes a penalty for increasing the number of parameters.

As indicated in Eq. 8, the fitting was carried out without using variable weighting coefficients on the deviations between experimental and predicted values. This method implicitly assumes that the expected errors in the fitted variable are independent of the value of the variable. To test whether the results were sensitive to this assumption, the fitting procedures were repeated for three models (Webb, Chou-Talalay multiple inhibitor and the present model) and all of the data sets, using deviations in ln(S) rather than S to define the objective function. This is mathematically equivalent to using a weighting coefficient on the squared deviations that is inversely proportional to the square of the variable. The ranking of the three models according to summed AIC was unchanged when this approach was used. For the data sets where ln(S) fits with the White et al. model were tested, the AIC was, overall, less than additive damage and the Webb model, but greater than the multiple inhibitor. However, it was noted that some of the White et al. model fits gave a non-monotonic behavior of the survival that was not shown in the original data set. This alternative fitting procedure with ln(S) could not be tested for the remaining models, because they are implicit in S (isobologram and Syracuse-Greco).

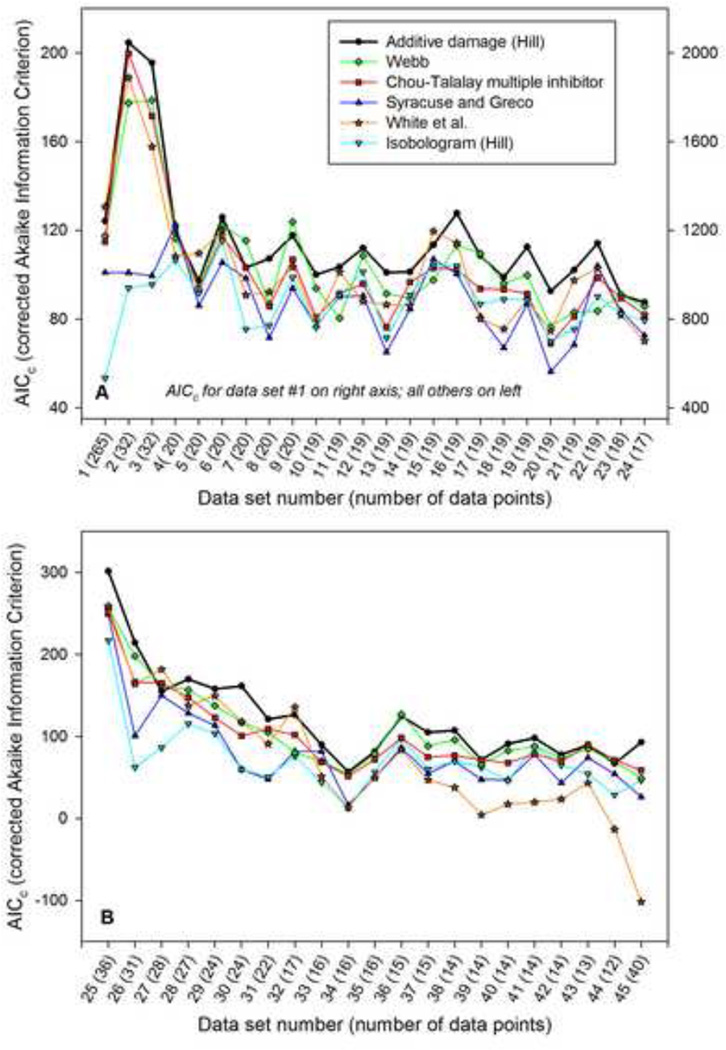

Four of the models considered (additive damage model, Syracuse-Greco, Chou-Talalay multiple-inhibitor, and Webb) have reduced forms with some parameters set to default values, resulting in fewer fitted parameters. In the Webb model, one or both of the saturation parameters s1 or s2 can be set to zero, giving three reduced forms. The Chou-Talalay multiple-inhibitor and Syracuse-Greco models each have one reduced form, without interaction (α = 0). The additive damage model allows for reduced forms by neglecting saturation in one or both drugs (s1 = 0, s2 = 0), and/or by assuming linearity of the damage term dependence on either or both of the intracellular species concentrations (i.e., m1 = 1, m2 = 1). When reduced models were considered, the value of p (number of free parameters) used in the formula for AICc was reduced accordingly. Reduced models may be appropriate in cases where the data set covers a narrow range in concentration, or when the intracellular processes leading to cell kill for a particular cell line have linear dependence on drug concentration. Therefore, the following approach was used consistently: for each cell line, the fits and AICc scores were determined for the full model and all reduced forms, and the highest AICc score among these was reported in Figure 2 and Table 3.

Figure 2.

Comparison of AICc values for candidate models, when applied to 45 data sets from the literature. The cell lines, drugs and data source are given in Table 2. Data sets are ordered from highest to lowest number of data points. A. Results for 24 in-vitro data sets for platinum-taxane drug combinations acting on cancer cell lines. Right axis is for data set number 1 only. B. Results for 21 in vitro data sets for various drug combinations (other than platinum-taxane) acting on cancer cell lines.

Table 3.

Summed AIC scores for each model considered. High numbers represent better overall model performance. The additive damage, Webb, and Syracuse-Greco models contain optional parameters that may be needed for some data sets but not others. The Chou-Talalay model has two forms, with and without interaction. In each case, the fits and AIC scores were computed for each form of the model, and the best AIC score was used.

| Platinum-taxane combinations (n = 24) |

Other drug combinations (n = 21) |

All combinations (n = 45) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Additive damage (Hill) | 3877 | 2562 | 6439 |

| Webb | 3630 | 2238 | 5868 |

| Chou-Talalay multiple inhibitor | 3540 | 2112 | 5652 |

| White et al. | 3621 | 1509 | 5130 |

| Syracuse and Greco | 3021 | 1658 | 4679 |

| Isobologram (Hill) | 2588 | 1500 | 4088 |

Prediction of responses to drug combinations based on single-agent data

The additive damage model can be used to predict dose-response for combinations, given data for dose-response of the individual drugs acting as single agents. Of the previously proposed models considered, the Webb model, the isobologram-Hill model, and the Syracuse-Greco model without interaction also have this ability. When the model is applied to cases in which each drug acts as a single agent, the results depend on n, m1 and m2 only as m1 · n and m2 · n. Therefore, in the absence of additional information on how the drug interacts with the cell, single-agent data cannot be used to estimate separately the exponents m1 (or m2), which relates cellular damage to the extracellular concentration, and n, which reflects the distribution of lethal damage thresholds. In this case, a reduced form of the model is obtained by imposing the constraint m1 · m2 = 1. The rationale for this is as follows. The exponents m1 and m2 arise from the kinetics of cellular uptake, metabolism and binding of the drug. In the absence of information suggesting nonlinear kinetics, the simplest assumption is that these exponents are close to 1, representing linear dependence on concentration. Note that any nonlinearity arising from saturation effects is accounted for separately, as in Eq. 4, rather than by the exponents m1 or m2. To ensure that m1 and m2 are as close to 1 as possible while allowing fits to the single-agent data, n is assumed equal to the geometric mean of the single-agent Hill exponents (m1 · n and m2 · n), implying that m1 · m2 = 1. When 3 or more drugs are considered, this constraint generalizes to m1 · m2 · …· mM = 1. The model with m1 · m2 = 1 is referred to as the “single-agent-based” model. It can be used to predict combination responses when sufficient single-agent data are available; generally this necessitates a minimum of five data points for each drug, distributed so that they cover the steepest part of the dose-response curve. Of the data sets considered here, only that of Liu et al. (32) met this criterion.

RESULTS

Figure 2 shows the AICc (corrected Akaike Information Criterion) values for the models considered, based on 24 data sets for platinum-taxane and 21 data sets for other drug combinations. A higher value of AIC means that the model performed better. In most cases, the model with highest AIC also had the lowest root-mean-square deviation of predictions from the data. However, this is not necessarily the case, and in some cases a better fit was offset by the penalty for additional parameters. The AIC and the AICc are derived as approximations to the Kullback-Leibler information (14). The Kullback-Leibler information is additive for multiple independent data sets (34), and AIC and AICc are therefore also additive. The sum of AICc scores for multiple data sets thus provides an overall assessment of each models’ performance, as shown in Table 3. For the additive damage model, the parameters for best fit to each data set are included in Table 4. For each data set, the form of the additive damage model with the highest AICc score, that is, either the full form or one of the reduced forms, is shown in Table 4. These values correspond to the AICc scores shown in Figure 2 and summed in Table 3. This approach avoids the inclusion of superfluous parameters that are not meaningful and identifiable.

Table 4.

Parameter values for additive damage model, for best fit to experimental data sets. RMS is the root-mean-square deviation of the model from the experimental data; a1 and a2 measure the sensitivities to drugs 1 and 2 (or, equivalently, their IC50) respectively; m1 and m2 measure each individual drug’s heterogeneity of response across the cell population for the cell line used in generating the data; n is the overall Hill exponent, a measure of average heterogeneity of response for the cell population; s1 and s2 are saturation concentrations for drugs 1 and 2, respectively.

| Data set |

RMS | a1 | m1 | a2 | m2 | n | s1 | s2 | Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.0939035 | 0.0306823 | 1 | 0.404367 | 5.50104 | 0.497627 | 0 | 0.194965 | 5 |

| 2 | 0.0337205 | 0.241045 | 1 | 0.00881996 | 1 | 0.89463 | 0.03893 | 0 | 4 |

| 3 | 0.0370858 | 0.122462 | 1 | 0.136868 | 10 | 0.97626 | 0 | 0.135656 | 5 |

| 4 | 0.0391248 | 1.24113 | 1 | 0.874593 | 1 | 1.74659 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 5 | 0.0616397 | 1.32678 | 1 | 0.863067 | 2.21264 | 2.07597 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| 6 | 0.0271318 | 0.531824 | 1.79347 | 0.804848 | 1.36196 | 1.65679 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| 7 | 0.0580907 | 3.12663 | 1 | 2.31275 | 1 | 2.43521 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 8 | 0.0479347 | 1.7255 | 1 | 0.295676 | 2.73736 | 2.73023 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| 9 | 0.0369444 | 8.27854 | 1 | 0.843256 | 2.49092 | 1.6991 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| 10 | 0.0436316 | 0.549153 | 2.4738 | 0.923266 | 1.70925 | 2.11544 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| 11 | 0.0447423 | 0.546907 | 1 | 2.15786 | 2.02631 | 2.8448 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| 12 | 0.0357231 | 0.788194 | 1.84563 | 1.36475 | 1 | 1.77856 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| 13 | 0.0426114 | 0.843847 | 1.77522 | 0.908486 | 2.94752 | 2.4289 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| 14 | 0.0473765 | 1.33867 | 1 | 2.04435 | 1.61947 | 2.31827 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| 15 | 0.0344388 | 2.24013 | 1.57072 | 0.980252 | 1 | 2.11839 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| 16 | 0.0210626 | 3.83759 | 1.66164 | 0.551775 | 2.14883 | 2.0565 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| 17 | 0.0349202 | 1.48475 | 1.5753 | 1.11362 | 3.07263 | 1.60152 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| 18 | 0.0505604 | 5.09454 | 2.56674 | 0.534194 | 1 | 1.72549 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| 19 | 0.0314221 | 5.09214 | 1.47278 | 0.805647 | 2.37472 | 2.25515 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| 20 | 0.0530275 | 2.36442 | 1 | 1.20339 | 4.43546 | 3.39939 | 1.10893 | 0 | 5 |

| 21 | 0.0413177 | 2.51718 | 1.46926 | 0.916413 | 2.42336 | 2.86128 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| 22 | 0.0301244 | 4.5273 | 1.44148 | 0.699026 | 1.91385 | 3.1443 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| 23 | 0.0529019 | 8.5315 | 1 | 1.01321 | 1.86385 | 1.97171 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| 24 | 0.0418318 | 0.546473 | 1.56097 | 0.257554 | 1.7426 | 2.11301 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| 25 | 0.0178651 | 0.0080393 | 1.3559 | 0.101857 | 5.84166 | 2.10427 | 0.00329495 | 0.0837992 | 7 |

| 26 | 0.0398241 | 0.0293868 | 0.0291344 | 0.00243049 | 0.24681 | 9.98453 | 0.462392 | 0 | 6 |

| 27 | 0.0703229 | 0.044228 | 1 | 0.283426 | 1 | 1.16133 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 28 | 0.0385312 | 4.57767 | 1 | 0.00275743 | 1 | 0.88504 | 4.2057 | 0 | 4 |

| 29 | 0.0398284 | 124.64 | 10 | 0.00242897 | 1 | 1.04053 | 123.306 | 0 | 5 |

| 30 | 0.0244091 | 0.206865 | 1 | 0.0347403 | 1 | 3.47283 | 0.12841 | 0.0407321 | 5 |

| 31 | 0.0566099 | 3.27575E-05 | 0.0392621 | 0.0908906 | 1 | 10 | 0 | 0.156966 | 5 |

| 32 | 0.0381175 | 0.00511181 | 0.400133 | 0.179293 | 1 | 5.77342 | 0 | 0.085392 | 5 |

| 33 | 0.0391946 | 171.061 | 1 | 10.8481 | 1 | 2.74961 | 137.402 | 6.67214 | 5 |

| 34 | 0.0874504 | 4.26563 | 1 | 11.1476 | 1 | 2.63706 | 2.06039 | 9.15804 | 5 |

| 35 | 0.0354854 | 0.279805 | 0.245391 | 0.00010922 | 0.204566 | 3.07004 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| 36 | 0.010497 | 0.000450903 | 0.300472 | 0.0205066 | 1 | 1.12266 | 0 | 0.0986472 | 5 |

| 37 | 0.0143339 | 8.35732 | 1 | 0.0166512 | 0.310411 | 1.42372 | 6.13938 | 0 | 5 |

| 38 | 0.0132726 | 0.413553 | 0.662962 | 0.3142 | 1 | 1.27856 | 0 | 0.442473 | 5 |

| 39 | 0.0500705 | 0.0868612 | 1 | 148.341 | 1 | 0.958445 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 40 | 0.0164673 | 0.0153225 | 0.34897 | 200.183 | 1 | 1.59512 | 0 | 63.6129 | 5 |

| 41 | 0.0162202 | 342.719 | 0.579113 | 11.8759 | 1 | 1.26834 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| 42 | 0.0334106 | 97.2493 | 0.532957 | 7.96999 | 1 | 1.50279 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| 43 | 0.0261508 | 7.3117 | 1 | 0.0353925 | 1 | 1.23017 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 44 | 0.0373971 | 15.2013 | 0.677339 | 0.0514551 | 1 | 1.38357 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| 45 | 0.00628888 | 0.00482147 | 0.351651 | 2.62618 | 0.0288747 | 7.18926 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

Overall, Figure 2 and Table 3 show that the additive damage model performs better than all the previous models considered, based on the Akaike Information Criterion. Interestingly, the Webb fractional product model is the second best performer. This model was the first drug combination model proposed, and is conceptually the simplest. The more widely accepted Chou-Talalay multiple-inhibitor model is less successful in fitting the available data sets. The White et al. (1) model performs well with the larger data sets, but its performance deteriorates rapidly as the number of data points decreases, probably due to its relatively large number of parameters. The Syracuse and Greco model (5, 6) and the isobologram model show significantly worse ability to represent the experimental data sets in almost all cases.

The additive damage model with the lognormal form for survival was compared with the version using the Hill equation (data not shown). In all cases, lognormal fits were very close to Hill fits, as expected given that the difference between the two forms is slight. For the data sets with the largest number of data points, the lognormal model showed slightly superior performance, whereas the Hill model performed slightly better for data sets with fewer data points. The available data sets are not sufficiently comprehensive and precise to determine which model is more accurate overall. The Hill form was used for the results presented here. An analogous situation arises with respect to the choice of statistical distribution to describe regression of a binary variable on a continuous variable, where two alternative models (probit and logit functions) generally provide equally good fits to the data (35).

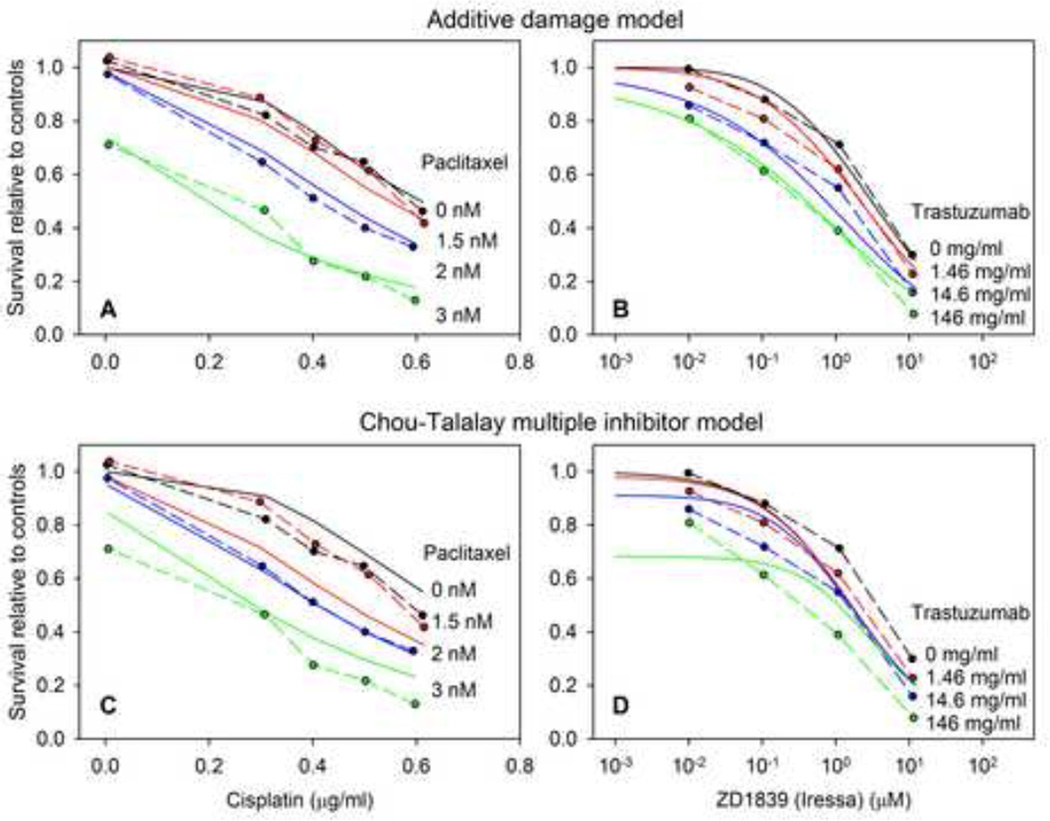

In Figure 3, best-fit model predictions of the additive damage model and one other model, the Chou-Talalay multiple inhibitor model (36), are compared with experimental data. Results are shown for two data sets (numbers 24 and 35 in Figure 2): those of Engblom et al. (22) for cisplatin and paclitaxel acting on SK-OV-3 ovarian carcinoma cells and those of Nakamura et al. (37) for the trastuzumab (Herceptin®) – ZD1839 (Iressa®) combination acting on A549 small cell lung carcinoma cells. These examples are chosen to illustrate typical differences between models in their ability to fit experimental data sets.

Figure 3.

Comparison of model predictions with experimental data for the additive damage model (A,B) and the Chou-Talalay multiple inhibitor model (C,D), for a paclitaxel-cisplatin combination data set Engblom et al. (22) (A,C), and the ZD1839-trastuzumab combination data of Nakamura et al. (30) (B,D). In each plot, dashed lines indicate experimental data and solid lines indicate best-fit model predictions.

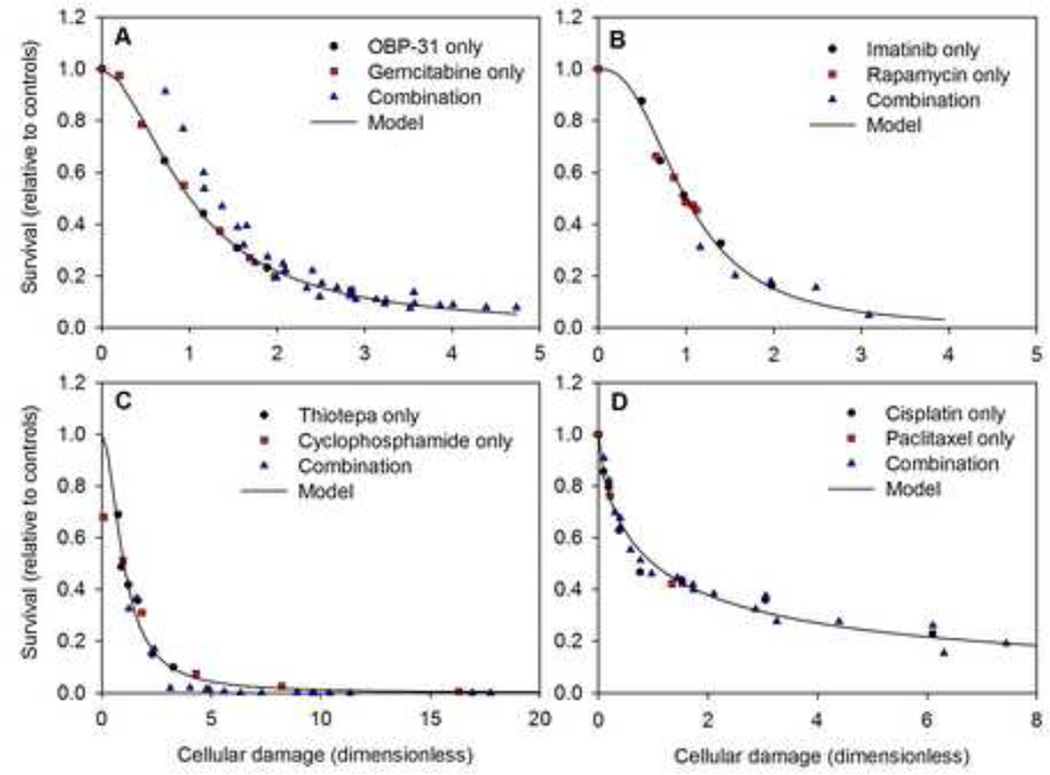

Figure 4 shows the dependence of survival on cellular damage for several of the drug combinations considered. These figures illustrate the basic concept of the model, in which survival is expressed as a sigmoidal function of a single variable (cellular damage) that depends on the concentrations of both drugs. They provide a method for visualizing the model fit to survival data for drug combinations. Since the same value of cellular damage can be achieved through many possible combinations of drug concentrations, it is possible for experimental data points to have the same value of damage but different values of survival. The extent to which the data points collapse to a single curve reflects the degree to which the additive damage model represents that particular data set.

Figure 4.

Survival as a function of cellular damage. A. Data of Liu et al 2009 (32); H322 human lung cancer cells; gemcitabine and OBP-31 (data set #45 of Table 2). Predicted values are based on model fits to the data for each drug acting as a single agent, without using the combination data. B. Data of Mohi et al 2004 (29); Ba/F-BCR/ABL WT cells; imatinib and rapamycin (data set #44 of Table 2). C. Data of Teicher et al (26); MCF-7 cells; thiotepa and cyclophosphamide (data set #31 of Table 2). D. Data of Hadaschik et al(21); J82 bladder cancer cells; cisplatin and paclitaxel (data set # 3 of Table 2). In B, C and D, model fits are based on all available data for single agents and combinations.

In one case (32), sufficient single-agent data are available to estimate the model parameters, independent of the combination data, using the single-agent-based model. The curve in Figure 4A shows the resulting model predictions. The combination data show a systematic deviation from the model, suggesting a significant interactive effect. The fact that the combination points lie above the predicted curve suggests that the combination is antagonistic. This case is considered further below in the discussion of synergy.

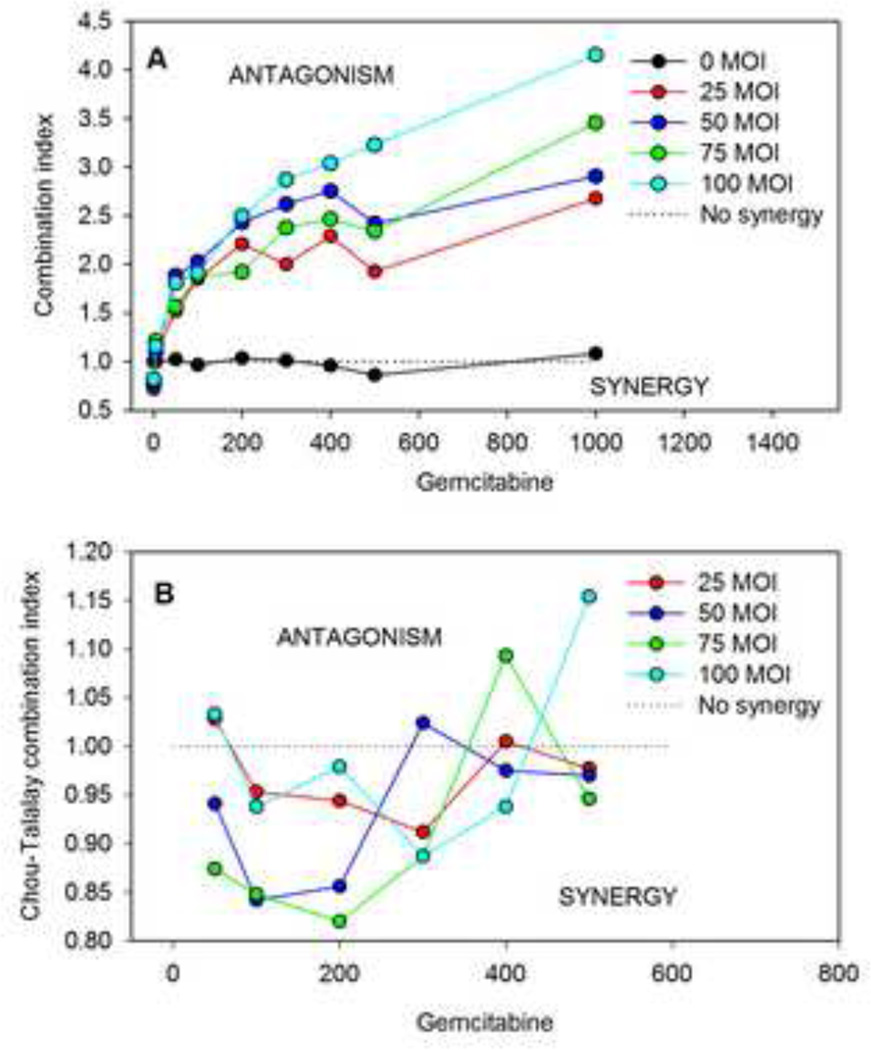

In the present approach, the level of synergy is quantified by a defining combination index CIn for data point n according to Equation 9, with predicted values obtained using the single-agent-based model. The values of this combination index are shown in Figure 5A for the data of Liu et al. (32) for OBP-301 virotherapy combined with gemcitabine. Figure 5B shows the results of the widely-used pointwise combination index of Chou and Talalay (38) as calculated by the Calcusyn program (39), for the same data set. The Calcusyn-generated combination index values were obtained directly from Liu et al. (32). Documentation on the vendor website (39) indicates that the equation used by Calcusyn is based on the combination index presented by Chou and Talalay (38), which corresponds to the isobologram-Hill (Chou-Talalay) combination index (Table 1). The present approach (Figure 5A) indicates an antagonistic interaction for most of the combinations considered, whereas the Chou and Talalay index (Figure 5B) suggests a synergistic interaction in most cases. The fact that these two approaches for testing synergy lead to different results emphasizes the importance of the choice of null model for synergy testing. As already mentioned, no a priori basis exists for defining the null model. It is proposed here that the null model that best fits a wide range of combination data sets should be used.

Figure 5.

Estimates of combination index based on data for combination of OBP-301 virotherapy with gemcitabine (32). “MOI” = multiplicity of infection. A. Combination index from present additive damage model. B. Combination index from Calcusyn program (38).

DISCUSSION

This study represents the first systematic comparison of multiple mathematical models for dose-responses of drug combinations, based on their ability to represent in vitro cytotoxicity data for many drug combinations and cell lines. The proposed additive damage model was found to be superior to previous models. The reasons for this were not definitely established, but some factors can be suggested. The additive damage model is based on a set of biologically reasonable assumptions, as stated in the Methods, with a minimum of ad hoc mathematical assumptions. Previous studies showed that a model based on mechanistic considerations generally outperforms models based on purely mathematical constructs (8, 9, 33). Consequently, this model is perhaps more likely than others to reflect realistic pharmacodynamic responses of cells. Inclusion of saturation effects allows the model to describe cases where survival approaches a non-zero level at high concentration. Several previous models (Table 1) also accommodate such a non-zero plateau, where it is interpreted as a “background” parameter (40). The present model shows how such an effect can arise from saturability of drug effects. Furthermore, the model satisfies the four conditions stated in the Introduction, ensuring that it is well behaved over the full range of drug concentrations and can match the best-fitting Hill equation for each drug acting as a single agent. The 45 data sets considered here include a wide range of cell types and exposure to drugs with varying mechanisms of action. This suggests that the additive damage model may provide a generally applicable approach for predicting the cytotoxic effects of drug combinations.

Models for drug interaction have been discussed in terms of the “additivity” or “Loewe additivity” property {Greco, 1996 424 /id, meaning that the model predicts the same response for a single drug considered as two agents with concentrations C1 and C2 as for the same drug with concentration C1 + C2. The additive damage model without saturation satisfies this additivity property. When applied to such sham combination data, it fits with m1 = m2 = 1, so that the survival depends on a linear combination of the concentrations. However, the model is not restricted to the case m1 = m2 = 1, and for true drug combinations these parameters often take values other than 1 (see Table 4). This fact that the model allows for the addition of nonlinear functions of concentration is central to the “additive damage” approach and another likely reason that the model is better able to fit available data. In this respect, the additive damage model represents a departure from the null reference models most often using in synergy testing, which are constrained to satisfy Loewe additivity for all drug combinations. Such models include the isobologram method and the basic forms of the Chou-Talalay, Syracuse-Greco and White models. The additive damage model with saturation does not satisfy the “additivity” test, because the saturation effects of the two agents are assumed to be independent, as would generally be the case for drugs with different modes of action, whereas saturation effects are additive for combinations of the same drug.

The proposed additive damage model can be extended in a number of ways. As mentioned earlier, it can be applied for any number of drugs in combination. Drugs with two or more mechanisms of action can be accommodated by including damage terms corresponding to each mechanism. By including separate terms in the model for each cellular drug species, the model can be extended to simulate interactions between drugs at the cellular level, such as the effect of one drug on target expression or cellular uptake of the other. The model provides a framework for analyzing the effects of varying exposure time, by including kinetics of cell uptake, binding and metabolism in the calculation of cellular damage. This approach was previously used for cisplatin, paclitaxel and doxorubicin acting as single agents (8, 9, 33).

The additive damage can also be used as a null reference model for testing of synergy. As already noted, the choice of the null model is not unique, and different null models lead to different assessments of synergy. An analogous situation exists in genetics, where interaction between genes is termed “epistasis.” Noting that two widely-accepted yet mathematically distinct definitions of epistasis have emerged in population genetics and in quantitative genetics, Wade et al. (41) proposed that epistasis is absent or averages out in a sufficiently large natural population. Similarly, we suggest that instances of synergy or antagonism tend to average out when a large data set is considered, and that a statistical approach that uses a large sample of different drugs and cell lines is the most appropriate method for choosing the null model for synergy testing. This represents a new approach to the choice of null model. Among the available models, the additive damage model best fits the 45 data sets considered here. It therefore represents a good estimate of behavior in the absence of synergy, and is appropriate for use as a null reference model. For this application, the parameters of the model should be deduced from single-agent data, and the predictions then compared with experimental data for combinations. This necessitates the use of the single-agent-based model, which is subject to the condition m1 · m2 = 1.Imposing this constraint slightly reduces the ability of the model to fit combination data, but the single-agent-based model still outperforms the other models considered, based on the total AICc obtained from the 45 data sets analyzed. In the future, availability of more extensive data sets or new theories for drug interaction may lead to development of alternative null models. The approach proposed here provides a rational basis for choosing among such models.

The additive damage model is applied here to the in-vitro responses of cells to combinations of two drugs applied with a fixed schedule. It neglects many factors that may play a role in determining the clinical response to combination therapies. For example, limitations of extracellular transport are not considered, the time-course of cellular exposure may differ from experimental conditions, overlapping drug toxicities may limit the combinations that can be used clinically, and in-vitro survival fraction of tumor cells may not be a direct indicator of tumor control. As already discussed, the present model can potentially be extended to address some of these limitations.

In summary, the present study introduces a new model for describing cellular responses to anticancer drug combinations, which performs better than previous models for a wide range of in-vitro data for different drugs and cell lines, according to the Akaike Information Criterion. The model provides an advantageous null reference model for synergy testing, a framework for analyzing and interpreting cellular dose-response data, and a potential basis for more realistic and reliable computational simulations of responses to combination drug therapies.

Highlights.

A new mathematical model (“additive damage”) for drug combinations is proposed.

The model relates cell kill to total damage, a sum of separate terms for each drug.

When tested on 45 independent data sets, the model outperformed previous models.

The additive damage model predicts combination response from single-agent response.

The additive damage model is an improved null reference model for assessing synergy.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH/NCI grant CA040355 and a Better Than Ever Grant from the University of Arizona Cancer Center.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.White DB, Slocum HK, Brun Y, Wrzosek C, Greco WR. A new nonlinear mixture response surface paradigm for the study of synergism: A three drug example. Current Drug Metabolism. 2003;4:399–409. doi: 10.2174/1389200033489316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chou TC, Talalay P. Generalized Equations for the Analysis of Inhibitions of Michaelis-Menten and Higher-Order Kinetic Systems with 2 Or More Mutually Exclusive and Non-Exclusive Inhibitors. European Journal of Biochemistry. 1981;115:207–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1981.tb06218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greco WR, Faessel H, Levasseur L. The search for cytotoxic synergy between anticancer agents: A case of Dorothy and the ruby slippers? Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1996;88:699–700. doi: 10.1093/jnci/88.11.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Webb JL. Effect of more than one inhibitor. Vol. 66. New York: Academic Press; 1963. p. 487. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greco WR, Park HS, Rustum YM. Application of a new approach for the quantitation of drug synergism to the combination of cis-diamminedichloroplatinum and 1-beta-D-arabinofuranosylcytosine. Cancer Res. 1990;50:5318–5327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Syracuse KC, Greco WR. Comparison between the method of Chou and Talalay and a new method for the assessment of the combined effects of drugs: A Monte-Carlo simulation study. Proceedings of the Biopharmaceutical Section of the American Statistical Association. 1986:127–132. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steel GG, Peckham MJ. Exploitable Mechanisms in Combined Radiotherapy-Chemotherapy - Concept of Additivity. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1979;5:85–91. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(79)90044-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El-Kareh AW, Secomb TW. Two-mechanism peak concentration model for cellular pharmacodynamics of doxorubicin. Neoplasia. 2005;7:705–713. doi: 10.1593/neo.05118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.El-Kareh AW, Labes RE, Secomb TW. Cell cycle checkpoint models for cellular pharmacology of paclitaxel and platinum drugs. Aaps Journal. 2008;10:15–34. doi: 10.1208/s12248-007-9003-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zimmer KG. Studies on quantitative radiation biology. 1961 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fowler JF. Differences in Survival Curve Shapes for Formal Multi-Target + Multi-Models. Physics in Medicine and Biology. 1964;9 177-&. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rai K, Van RJ. A generalized multihit dose-response model for low-dose extrapolation. Biometrics. 1981;37:341–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goutelle S, Maurin M, Rougier F, Barbaut X, Bourguignon L, Ducher M, et al. The Hill equation: a review of its capabilities in pharmacological modelling. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2008;22:633–648. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.2008.00633.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hurvich CM, Tsai CL. Regression and Time-Series Model Selection in Small Samples. Biometrika. 1989;76:297–307. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wagner JG. Kinetics of Pharmacologic Response. I. Proposed Relationships Between Response and Drug Concentration in Intact Aminal and Man. Journal of Theoretical Biology. 1968;20 doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(68)90188-4. 173-&. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chou TC. Preclinical versus clinical drug combination studies. Leuk Lymphoma. 2008;49:2059–2080. doi: 10.1080/10428190802353591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chou TC. Drug combination studies and their synergy quantification using the Chou-Talalay method. Cancer Res. 2010;70:440–446. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Engblom P, Rantanen V, Kulmala J, Helenius H, Grenman S. Additive and supra-additive cytotoxicity of cisplatin-taxane combinations in ovarian carcinoma cell lines. Br J Cancer. 1999;79:286–292. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raitanen M, Rantanen V, Kulmala J, Helenius H, Grenman R, Grenman S. Supra-additive effect with concurrent paclitaxel and cisplatin in vulvar squamous cell carcinoma in vitro. International Journal of Cancer. 2002;100:238–243. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levasseur LM, Greco WR, Rustum YM, Slocum HK. Combined action of paclitaxel and cisplatin against wildtype and resistant human ovarian carcinoma cells. Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology. 1997;40:495–505. doi: 10.1007/s002800050693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hadaschik BA, ter Borg MG, Jackson J, Sowery RD, So AI, Burt HM, et al. Paclitaxel and cisplatin as intravesical agents against non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Bju International. 2008;101:1347–1355. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Engblom P, Rantanen V, Kulmala J, Grenman S. Carboplatin-paclitaxel- and carboplatin-docetaxel-induced cytotoxic effect in epithelial ovarian carcinoma in vitro. Cancer. 1999;86:2066–2073. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19991115)86:10<2066::aid-cncr26>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsuno S, Hisano H, Kobari M, Akaishi S. Growth-Inhibitory Effects of Combination Chemotherapy for Human Pancreatic-Cancer Cell-Lines. Cancer. 1990;66:2369–2374. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19901201)66:11<2369::aid-cncr2820661120>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nishikawa T, Kohjimoto Y, Nishihata M, Ebisuno S, Hara I. Synergistic Antitumor Effects of Fleroxacin With 5-fluorouracil In Vitro and In Vivo for Bladder Cancer Cell Lines. Urology. 2009;74:1370–1376. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dranoff G, Elion GB, Friedman HS, Bigner DD. Combination chemotherapy in vitro exploiting glutamine metabolism of human glioma and medulloblastoma. Cancer Res. 1985;45:4082–4086. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Teicher BA, Holden SA, Cucchi CA, Cathcart KN, Korbut TT, Flatow JL, et al. Combination of N,N',N"-triethylenethiophosphoramide and cyclophosphamide in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res. 1988;48:94–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Herberger B, Berger W, Puhalla H, Schmid K, Novak S, Brandstetter A, et al. Simultaneous blockade of the epidermal growth factor receptor/mammalian target of rapamycin pathway by epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors and rapamycin results in reduced cell growth and survival in biliary tract cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:1547–1556. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Derosier LC, Vickers SM, Zinn KR, Huang Z, Wang W, Grizzle WE, et al. TRA-8 anti-DR5 monoclonal antibody and gemcitabine induce apoptosis and inhibit radiologically validated orthotopic pancreatic tumor growth. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:3198–3207. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mohi MG, Boulton C, Gu TL, Sternberg DW, Neuberg D, Griffin JD, et al. Combination of rapamycin and protein tyrosine kinase (PTK) inhibitors for the treatment of leukemias caused by oncogenic PTKs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:3130–3135. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400063101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakamura H, Takamori S, Fujii T, Ono M, Yamana H, Kuwano M, et al. Cooperative cell-growth inhibition by combination treatment with ZD1839 (Iressa) and trastuzumab (Herceptin) in non-small-cell lung cancer. Cancer Lett. 2005;230:33–46. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Normanno N, Campiglio M, De Luca A, Somenzi G, Maiello M, Ciardiello F, et al. Cooperative inhibitory effect of ZD1839 (Iressa) in combination with trastuzumab (Herceptin) on human breast cancer cell growth. Annals of Oncology. 2002;13:65–72. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu D, Kojima T, Ouchi M, Kuroda S, Watanabe Y, Hashimoto Y, et al. Preclinical evaluation of synergistic effect of telomerase-specific oncolytic virotherapy and gemcitabine for human lung cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:980–987. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.El-Kareh AW, Secomb TW. A mathematical model for cisplatin cellular pharmacodynamics. Neoplasia. 2003;5:161–169. doi: 10.1016/s1476-5586(03)80008-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Torgersen EN. Comparison of statistical experiments. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hamilton MA, Russo RC, Thurston RV. Trimmed Spearman-Karber Method for Estimating Median Lethal Concentrations in Toxicity Bioassays. Environmental Science and Technology. 1977;11:714–719. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chou TC, Talalay P. Quantitative-Analysis of Dose-Effect Relationships - the Combined Effects of Multiple-Drugs Or Enzyme-Inhibitors. Advances in Enzyme Regulation. 1984;22:27–55. doi: 10.1016/0065-2571(84)90007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nakamura H, Takamori S, Fujii T, Ono M, Yamana H, Kuwano M, et al. Cooperative cell-growth inhibition by combination treatment with ZD1839 (Iressa) and trastuzumab (Herceptin) in non-small-cell lung cancer. Cancer Letters. 2005;230:33–46. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chou TC, Talalay P. Analysis of Combined Drug Effects - A New Look at A Very Old Problem. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 1983;4:450–454. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Biosoft. Calcusyn: Dose-Effect Analyzer for Single and Multiple Drugs. 2012 2-21-2012. Ref Type: Online Source. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khinkis L, Krzyzanski W, Jusko WJ, Greco WR. D-optimal designs for parameter estimation for indirect pharmacodynamic response models. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2003;73:23. doi: 10.1007/s10928-009-9135-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wade MJ, Winther RG, Agrawal AF, Goodnight CJ. Alternative definitions of epistasis: dependence and interaction. Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 2001;16:498–504. [Google Scholar]