Abstract

Tendons and ligaments exhibit limited regenerative capacity following injury, with damaged tissue being replaced by a fibrotic scar. The physiological role of scar tissue is complex and has been studied extensively. In this study, we demonstrate that rat tendons contain a unique subpopulation of cells exhibiting stem cell characteristics, including clonogenicity, multipotency, and self-renewal capacity. Additionally, these putative stem cells expressed markers consistent with neural crest stem cells (NCSCs). Using immunofluorescent labeling, we identified P75+ (p75 neurotrophin receptor) cells in the perivascular regions of the native rat tendon. Importantly, P75+ cells were frequently localized near vascular cells and increased in number within the peritenon after injury. Ultrastructural analysis showed that perivascular cells detached from vessels in response to injury, migrated into the interstitial space, and deposited extracellular matrix. Characterization of P75+ cells isolated from the scar tissue indicated that this population also expressed the NCSC markers, Vimentin, Sox10, and Snail. In conclusion, our results suggest that neural crest-like stem cells of perivascular origin reside within the rat peritenon and give rise to scar-forming stromal cells following tendon injury.

Introduction

Tendons and ligaments comprise highly organized, dense fibrous connective tissue and are critical for proper joint movement and stability. More than 32 million tendon and ligament injuries occur in the United States annually [1], and the healing of these injuries is complicated by the generation of an intervening layer of fibrotic scar tissue [2,3], which is morphologically, biochemically, and biomechanically inferior to healthy tendon tissue. Although current treatments for tendon/ligament injures, including autografts, allografts, xenografts, and prosthetic devices, have been highly successful, there remains a need for additional less invasive therapies. To develop better alternative treatments for tendon repair, it is imperative to better understand the process of natural repair in the injured tendon.

Recent breakthroughs in the study of tendon stem/progenitor cells indicate that stem cells can be isolated from the tendon and cultured in vitro [4–7]. These stem cells have been shown to be effective in promoting tendon healing in vivo [8–11]. Moreover, studies have found that perivascular cells/pericytes exist within vascularized regions of tendons, sites considered to be a potential niche for tendon stem cells [12–14]. Studies also revealed that neural crest cells inhabit in a perivascular niche in multiple tissues [15–18]. However, due to the lack of a specific marker for tendon stem cells, few studies have investigated the precise location of the tendon stem/progenitor cells and their role in response to injury in vivo.

In this study, we hypothesized that tendons contain a subpopulation of stem-like cells, and that the stem cell niche lies in close proximity to the tendon vasculature. Furthermore, we hypothesized that this stem cell population is capable of contributing to tendon scar formation following injury.

Materials and Methods

Animals and experimental protocol

Animal experiments were carried out in accordance with protocols approved by Chongqing University and the Third Military Medical University Animal Care and Use Committee. Female Sprague-Dawley rats weighing 200–250 g were used in all experiments. We employed a well-established window defect model to create the injury in the rat patellar tendon as described previously [19]. Briefly, using the aseptic technique, animals under anesthesia were shaved off fur on both hind limbs, and the skin, soft tissue, and peritenon were dissected using a ventral longitudinal incision to expose the patellar tendon. Subsequently, a standardized full-thickness window defect (1×4 mm) was created in the central portion of the tendon. Following injury, the peritenon was either scraped or sutured, and the skin of both hind limbs was sutured. Rats were not immobilized postoperatively, being permitted to move freely within cages.

Cell culture

Rat patellar tendon cells were cultured as follows: under aseptic conditions, the peritenon were removed, then the tendon tissue was minced into small pieces and digested with 3 mg/mL collagenase type I (Sigma-Aldrich) in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Invitrogen) for 2 h at 37°C. The digested tissue homogenate was passed through a 70-μm pore size cell filter and single-cell suspensions were plated onto CELLstart™ (Invitrogen)-coated dishes and cultured with the neural crest stem cell (NCSC) medium at 37°C in a humidified chamber containing 5% CO2. NCSC medium comprised DMEM supplemented with 1% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Invitrogen), 2% chick embryo extract (MP Biomedical), 1% N2 supplement (Invitrogen), 2% B27 supplement (Invitrogen), 100 nM retinoic acid (Sigma-Aldrich), 50 nM 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich), 1% penicillin/streptomycin (P/S), and 20 ng/mL basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF; R&D Systems). The medium was refreshed every 3 days; cells were expanded by trypsinization and replating.

Cell cloning and sphere formation assay

To assess colony-forming efficiency, we cultured single-cell suspensions of tendon-derived cells at low density (20 cells/cm2) in 100-mm Petri dishes. After 7–10 days in culture, tendon-derived cells formed colonies that could be visualized using an inverted light microscope (BX51; Olympus). After 2 weeks, colonies were stained with 1% methyl violet (Sigma-Aldrich) and counted. For calculating colony-forming efficiency, cells at passages 2 and 5 were cultured in vitro for 14 days and quantified by counting colonies that contained more than 25 cells. The percent colony-forming efficiency was calculated as follows: number of colonies/number of cells plated×100.

For the sphere formation assay, single-cell suspensions of tendon-derived cells were plated onto Ultra-Low attachment dishes (Corning) at 5×103 cells/mL and cultured in the presence of the NCSC medium for 14 days. The resultant neural sphere-like aggregates were visualized using an inverted light microscope (BX51; Olympus).

Multipotent differentiation

The in vitro multidifferentiation potential of tendon-derived cells to undergo osteogenesis, adipogenesis, chondrogenesis, neurogenesis, and smooth muscle cytogenesis was performed as described previously [20,21].

Immunostaining

For immunostaining, cells or tissue sections were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich), and blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma-Aldrich). Samples were incubated with primary antibodies (Table 1) or nonimmune antiserum as a negative control at 4°C overnight, then with Alexa Fluor 488 and/or Alexa Fluor 546-conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen) for 1 h, and counterstained with 1 μg/mL DAPI (Roche) for 10 min at room temperature. Fluorescence and bright-field images were obtained using fluorescence microscopy (BX51; Olympus) or confocal microscopy (SP5; Leica). Image acquisition parameters for each channel were kept consistent between individual sections.

Table 1.

Antibodies Used in This Study

| Antibody | Company | Catalog no. | Dilution/application |

|---|---|---|---|

| P75 | Abcam | ab8874 | 1:500/IF |

| Vimentin | ZSGB-BIO | ZM-0260 | 1:100/IF |

| Snail | Santa Cruz | sc-28199 | 1:50/IF |

| Sox10 | R&D Systems | MAB2864 | 1:50/IF |

| α-smooth muscle actin | ZSGB-BIO | ZM-0003 | 1:100/IF |

| PE anti-mouse CD146 | Biolegend | 134704 | 1:50/IF |

| NG2 | Invitrogen | 37-2700 | 1:500/IF |

| Decorin | Abcam | ab54728 | 1:1,000/IF |

| Neuron-specific class III beta-tubulin (Tuj 1) | Covance | MMS-435P | 1:1,000/IF |

| PE anti-rat CD34 | Biolegend | 119307 | 1:50/FC |

| PE anti-rat CD54 | Biolegend | 202405 | 1:50/FC |

| FITC anti-mouse/rat CD29 | Biolegend | 102205 | 1:50/FC |

| Alexa Fluor® 488 anti-rat CD90 | Biolegend | 202505 | 1:50/FC |

| PE mouse IgG1, κ isotype control | Biolegend | 400111 | 1:50/FC |

| FITC mouse IgG2a, κ isotype control | Biolegend | 400207 | 1:50/FC |

| Alexa Fluor® 647 anti-CD45 | Biolegend | 202212 | 1:50/FC |

| PE/Cy7 anti-P75 | Biolegend | 345110 | 1:50/FC |

| PE/Cy7 mouse IgG1, κ isotype control | Biolegend | 400125 | 1:50/FC |

| Alexa Fluor® 647 mouse IgG1, κ isotype control | Biolegend | 400130 | 1:50/FC |

Flow cytometry

For the cell surface antigen analysis, cells were dissociated with 0.2% EDTA for 20 min at room temperature. Nonspecific sites were blocked with 1% BSA, and cells were incubated with fluorescein-labeled antibodies (Table 1). Negative control samples were incubated with a nonspecific antibody of the same isotype as the primary antibody. Finally, cells were washed twice with 1 M PBS, and a minimum of 50,000 events were acquired on a BD FACSVerse™ flow cytometer and analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star).

For cell sorting, single-cell suspensions obtained from the injured area in repaired tendons at 7 days postinjury (dpi) were collected as described above. Approximately 1×107 cells were incubated with a combination of anti-CD45-AF647 and anti-P75-PE/Cy7 in 1 mL of DMEM containing 10% FBS and 1% P/S at 4°C for 30 min in the dark. Cells were then incubated for 10 min with 7-amino-actinomycin D (7-AAD; BD Biosciences) for exclusion of nonviable cells and analyzed on a BD FACSAria™ II flow cytometer. After sorting, cells were plated onto CELLstart-coated dishes and cultured in the NCSC medium at 37°C/5% CO2.

Transmission electron microscopy

Tissue samples of the native tendon and injured tendon were fixed according to standard protocols for transmission electron microscopy (TEM) [22].

In vitro angiogenesis assay

To test the potential angiogenesis ability of sorted P75+ cells, endothelial tube formation was performed in Matrigel cultures in vitro. Briefly, 1.5×104 cells were seeded onto 48-well plates coated with Matrigel (BD Biosciences) and were cultured in Medium 131 (Invitrogen) for 24 h. The tubular structures were observed and imaged with a microscope (BX51; Olympus).

Quantitative analysis

To quantify the α-smooth muscle actin (SMA)+ cells in the native tendon, coronal frozen sections of 7 μm thickness were immunostained for SMA. The number of SMA+ cells was counted in six sections per sample. A total of three samples were used for counting; results are presented as the total number of SMA+ cells per section.

To quantitate changes in the number of SMA+ cells and p75 neurotrophin receptor (P75)+ cells in response to injury, injured tendons were collected at the indicated time points and were cut coronally in a cryostat at a thickness of 7 μm. Sections were immunostained for SMA, P75, or both. Since the SMA+ and P75+ cells were too abundant to count individually, we calculated the area of positive staining for each antigen using Image-Pro Plus software (Media Cybernetics, Inc.). Briefly, images were converted to gray scale and contrast was uniformly enhanced; positive areas were quantitated using Count/Size tools. Areas of positivity were counted in six sections per sample. Values were first averaged per sample, and then averaged per time point for three samples. The results are presented as the total area of SMA+ or P75+ cells per section. The standard deviation was calculated based on the average value per time point.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using a t test for comparisons between two groups and by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni post hoc test for comparisons between more than two groups (Prism; GraphPad Software). Differences were considered significant when P<0.05.

Results

Isolation and characterization of neural crest-like stem cells from the rat tendon

To characterize the clonogenic potential of tendon-derived cells, we isolated single-cell suspensions from rat patellar tendons, plated them at low density, and cultured them with the NCSC medium, a modified medium optimized for in vitro culture of NCSCs. After 5–7 days of quiescence, cells rapidly divided to form colonies of five different morphologies (Fig. 1A–E). After 2 weeks, colonies were visualized using methyl violet staining (Fig. 1F). We also evaluated the colony formation of tendon-derived cells after several passages in culture, which resulted in a reduction in colony-forming efficiency (Fig. 1G). After passaging, the cells appeared morphologically homogeneous and fibroblastis (Fig. 1H, I). In addition, the cells formed spheres on Ultra-Low attachment dishes (Fig. 1J). Taken together, these results suggest that tendon-derived cells have clonogenic potential.

FIG. 1.

Isolation and characterization of neural crest cell-like tendon stem cells. (A–E) Morphology of clonal types of rat patellar tendon-derived cells. (F) Colony formation of tendon-derived cells visualized by methyl violet staining. (G) Colony-forming efficiency of tendon-derived cells at passage 2 and passage 5. (H) Morphology of passaged cells, magnified in (I). (J) Sphere formation of tendon-derived cells cultured on Ultra-Low attachment plates, the inset shows a larger scale of visual field. Multidifferentiation potential (K–O): Alizarin Red S staining for mineralization (osteogenesis); Oil red O staining (adipogenesis); Alcian blue staining (chondrogenesis); SMA immunostaining (smooth muscle cell differentiation); Tuj1 immunostaining (peripheral neurogenesis). (P–T) Immunostaining of tendon-derived cells using antibodies against Decorin, P75, Vimentin, Snail, and Sox10. Arrows in (T) indicate the heterogeneity of tendon-derived cells. (U) Flow cytometric analysis of the expression of cell surface markers related to mesenchymal stem cells and hematopoietic stem cells. SMA, α-smooth muscle actin. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

To determine the multipotency of the tendon-derived cells, we cultured cells with specific differentiation media for 1–4 weeks. Alizarin Red staining of cells cultured in the osteogenic differentiation medium for 3 weeks indicated that the isolated cells were capable of differentiating toward the osteoblast lineage (Fig. 1K). Induction of adipogenesis for 1 week was confirmed by Oil red O staining (Fig. 1L), and chondrogenic differentiation after induction in the chondrogenic medium for 4 weeks was assessed in the pellet culture by Alcian blue staining (Fig. 1M). SMA immunostaining confirmed that tendon-derived cells could differentiate into smooth muscle cells (Fig. 1N). To test whether the isolated cells possessed multipotency as NCSCs, the cells were induced with the neurogenic medium. Subsequent immunostaining indicated differentiation into Tuj1+ peripheral neuron-like cells (Fig. 1O). These results suggest that tendon-derived cells exhibit multidifferentiation potential.

The tendon-derived cells also expressed a comprehensive set of markers that are considered to define NCSCs, including P75, Vimentin, Snail, and Sox10 (Fig. 1Q–T). They also expressed the tendon-related marker Decorin (Fig. 1P), suggesting that these cells simultaneously maintained tenocyte properties. The tendon-derived cells also expressed general mesenchymal stem cell markers, CD29 and CD90, and were negative for hematopoietic stem cell markers, CD45, CD34, and CD54, as evidenced by flow cytometric analysis (Fig. 1U).

In summary, tendon-derived cells could not only differentiate into mesenchymal lineages, including osteoblasts, chondrocytes, adipocytes, and smooth muscle cells, as previously reported [4] but also into peripheral neuron-like cells, similar to NCSCs. Moreover, these cells express a panel of neural crest cell markers; therefore, we defined this type of cell as a neural crest cell-like tendon stem cell (NCCL-TSC).

Vascular cells in adult rat patellar tendon and peritenon

Since blood vessels have been reported to represent a rich supply of stem/progenitor cells in both tendon and other tissues [12,23,24], we examined vascular distribution in the adult rat patellar tendon. Immunofluorescent staining showed that tendons abundantly contained SMA+ vascular cells (Fig. 2A–F); however, vascular cells were markedly enriched in peritenon compared with the midsubstance tendon (49.5 cells/section vs. 13 cells/section, respectively; P<0.01) (Fig. 2G), in which the SMA+ cells localized to the endotenon (Fig. 2C). Taken together, these data suggest the enhanced vascularity in the peritenon compared with the midsubstance tendon.

FIG. 2.

Vascular cells in the native tendon. Coronal section of a rat native patellar tendon (A) and immunostaining for SMA (B). (C, D) Magnification of the dashed areas in (B), arrows indicate SMA+ cells in endotenon; dashed lines indicate the boundary between midsubstance and peritenon. Sagittal section showing SMA+ cells in the midsubstance (E) and peritenon (F) of a rat native patellar tendon; dashed line demarcates the boundary between midsubstance and peritenon. (G) Quantitation SMA+ vascular cells per section in the midsubstance and peritenon. **P<0.01. M, midsubstance; P, peritenon. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

P75+ cells in adult rat patellar tendon and peritenon

Following isolation and characterization of the NCCL-TSCs in vitro, we investigated the in vivo location of the stem cell niche based on the expression of P75, a commonly used marker for NCSCs [25,26]. P75+ cells were rare in the native tendon, except for the peritenon region, in which P75+ cells surrounded SMA+ vascular cells (Fig. 3), suggesting that P75+ cells localized in a perivascular niche. However, we could not detect the expression of Sox10 and Snail, the other two markers for NCSCs, both in the native tendon and injured tendon (data not shown). This could be due to the activation of these stem cells after they are isolated and cultured, which are similar to other investigations [27,28].

FIG. 3.

Location of P75+ cells in the native tendon. Immunostaining for DAPI (A), SMA (B), P75 (C) in coronal sections of native patellar tendon. (D) Merge of (A–C). Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

Peritenon vascular cells participate in tendon scar formation after injury

To investigate the role of peritenon vascular cells in tendon repair, we induced tendon injury followed by either suturing or scraping the peritenon. At an early time point after injury (<7 dpi), macroscopic observation indicated that the peritenon-sutured group repairs faster than the peritenon-scraped group (Fig. 4), suggesting that constituents of the peritenon may promote tendon repair. Furthermore, by cross-sectional analysis, we observed a marked increase in the thickness of the peritenon in the peritenon-sutured tendons compared with the peritenon-scraped tendons (Fig. 5A). The thickness change was accompanied by an increase in the number of SMA+ vascular cells distributed within the peritenon (Fig. 5A, B). The cross-sectional area of vascular cells was increased at early times (<7 dpi) and decreased at late times (7–28 dpi) in both groups; however, the cross-sectional area of vascular cells was significantly larger in the peritenon-sutured group at all time points except 28 dpi (Fig. 5B).

FIG. 4.

The contribution of peritenon to tendon healing. Macroscopic observation of the knee, and the obverse and reverse sides of repaired tendons in peritenon-sutured and peritenon-scraped animals at 2, 4, 7, and 21 dpi. dpi, days postinjury. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

FIG. 5.

Distribution and quantification of SMA+ cells in repaired tendons. Distribution (A) and quantification (B) of SMA+ cells in peritenon-sutured and peritenon-scraped tendons at 2, 4, 7, and 28 dpi. #P<0.05, ##P<0.01, compared between the two groups at each time point; *P<0.05, **P<0.01, compared between time points (2, 4, 7, 28 dpi) in each group. NT, native tendon. The dashed yellow lines indicate the boundary of the native tendon and other tissues. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

Perivascular P75+ cells form the core of the scar in the injured tendon

To explore the role of P75+ cells in tendon repair, we performed immunostaining for P75 in the peritenon-sutured group. Results indicated that tendon injury induced an increase in the P75+ cell number (Fig. 6A), which peaked at 7 dpi and then decreased progressively as the scar condensed (Fig. 6B); however, this response was restricted to the peritenon and the injured midsubstance tendon (Fig. 6A).

FIG. 6.

Distribution and quantification of P75+ cells in repaired tendons. Distribution (A) and quantification (B) of P75+ cells in peritenon-sutured tendons at 2, 7, 14, and 28 dpi. ** P<0.01. The dashed yellow lines indicate the boundary of the native tendon and other tissues. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

High magnification images indicated that some P75+ cells were localized to the periphery of regions containing SMA+ vascular cells (Fig. 7A, B). Despite the dramatic decrease in the P75+ cell number at later stages of repair (week 4), many of the remaining cells were located in the perivascular region (Fig. 7C). In addition, most P75+ cells were not colocalized with CD146+ cells (Fig. 7D) or NG2+ cells (Fig. 7E), which were mainly expressed at the vascular features in the tendon.

FIG. 7.

Contribution of perivascular P75+ cells to tendon repair. Immunostaining for SMA and P75 in coronal (A) and sagittal (B) sections of repaired tendons at 7 dpi (A, B) and in coronal sections at 28 dpi (C). Colocalization of P75+ cells with CD146+ cells (D) and NG2+ cells (E) in repaired tendons at 7 dpi, respectively. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

To gain insight into the roles of perivascular P75+ cells in early tendon scar formation, we examined native tendon vascular cells as well as the early events of perivascular cells at 2 dpi by TEM. Ultrastructural analysis showed that some capillaries existed in native tendon, primarily in the peritenon (Fig. 8A), surrounded by perivascular cells (Fig. 8B, C), which were in direct contact with intact basal lamina (Fig. 8D). In response to injury, these perivascular cells formed contacts with endothelial cells in the peg and socket arrangement (Fig. 8E, F), then detached from the basal lamina encasement (Fig. 8G, H), and deposited abundant extracellular matrix (ECM) (Fig. 8I, J).

FIG. 8.

Ultrastructural analysis of perivascular cells involved in tendon repair. Electron micrograph showing a sagittally cut blood vessel (A) with a perivascular cell and two endothelial cells (B) in the native tendon. (B) A higher magnification image of the dashed area in (A). (C) A coronally cut blood vessel with a perivascular cell within intact basal lamina (arrowheads in D, higher magnification of the dashed area in C) in the native tendon. At 2 dpi, electron micrograph showing a perivascular cell (E) interacting with an endothelial cell, in the peg and socket formation (arrowheads in F, higher magnification of the dashed area in E). (G) A perivascular cell detaching from the blood vessel with an intact basal lamina at the luminal side (arrowheads in H and I, higher magnification of dashed areas in G) and damaged basal lamina at the abluminal side. (J) Production of abundant fibrous ECM by a perivascular cell. p, perivascular cell; bv, blood vessels; e, endothelial cell; ECM, extracellular matrix; RBC, red blood cell; bl, basal lamina.

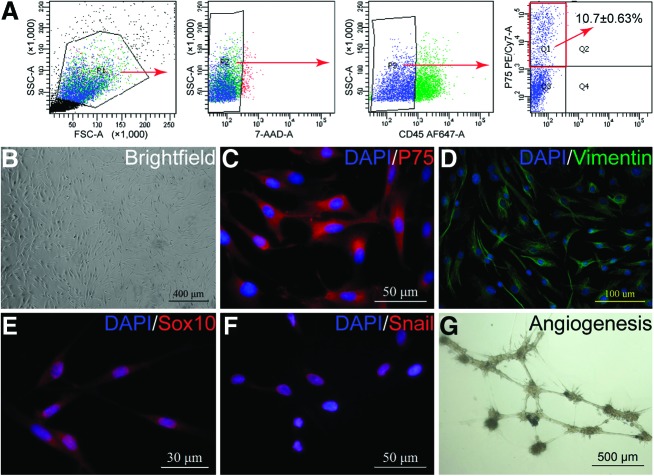

Perivascular P75+ cells are neural crest-like stem cells and have the ability of angiogenesis

To better define the characteristics of P75+ cells in tendon repair, scar-derived cells were sorted for expression of P75 after gating out dead (7-AAD+) cells and hematopoietic (CD45+) cells (Fig. 9A). P75+/CD45− cells represented ∼10% of the sorted cells. Using a panel of NCSC markers, immunofluorescent analysis indicated that the sorted P75+ cells were also positive for Vimentin, Sox10, and Snail (Fig. 9). In addition, the formation of endothelial tubular structures suggested that the sorted P75+ cells have the ability of angiogenesis, which could play a mechanistic role in tendon repair.

FIG. 9.

Sorting and characterization of P75+ cells from the injured tendon. (A) Cell sorting of P75+ cells by fluorescence-activated cell sorter from injured tendons at 7 dpi. Cells were sorted for expression of P75 after gating out dead cells (7-AAD+) and hematopoietic cells (CD45+). Immunostaining of P75+ cells (B) for NCSC-related markers P75 (C), Vimentin (D), Sox10 (E), and Snail (F). (G) In vitro angiogenesis of P75+ cells. 7-AAD, 7-amino-actinomycin D; NCSC, neural crest stem cell. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

Discussion

In the present study, we cultured neural crest-like stem cells from the tendon and defined their in vivo location. The majority of P75+ cells were detected in the peritenon, a highly vascularized region of tendon. Moreover, concomitant with the emergence of SMA+ vascular cells, perivascular P75+ cells were activated in response to tendon injury, depositing abundant ECM, thus contributing to scar formation.

The identity of the cell population responsible for normal tendon healing remains to be elucidated. According to the extrinsic hypothesis of tendon healing, cells migrate from surrounding tissues to the site of injury [29,30], while the intrinsic hypothesis suggests that a subpopulation of fibroblasts within the tendon itself contributes to tendon healing [31,32]. These hypotheses need not be mutually exclusive; indeed, recent studies suggest that both healing mechanisms may coexist [33,34]. In this study, we observed an infiltration of peritenon into the injury site, accompanied by the emergence of SMA+ vascular cells and P75+ perivascular cells, providing evidence to support the extrinsic tendon healing hypothesis.

The neural crest is an embryonic structure characterized in vertebrates, and contains multipotent progenitor cells capable of differentiating into multiple lineages for proper development of bones, cartilage, and vascular smooth muscle cells of the musculoskeletal system, neurons, and glial cells of the peripheral nervous system, connective tissue, endocrine cells, and melanocytes [35]. In this study, the isolated population of tendon-derived cells expressed a panel of neural crest cell markers and could be differentiated into both mesenchymal and neural lineages. The multipotency of these cells meets the commonly used criteria for defining an NCSC; however, since this study did not investigate the precise developmental origin of the tendon stem cells by genetic-based lineage tracing, we denoted this type of tendon stem cell as NCCL-TSC. In addition, in this study, we employed the NCSC medium to culture tendon-derived stem cells, which could create some selection pressure on cells and change their fate commitment subsequently. More experiments should be performed to test this effect in our future studies.

Pericytes have been verified as one source of adult pluripotent stem cells for the maintenance of tissue homeostasis and are known to contribute to tissue healing after injury [36,37]. Using genetic-based lineage tracing, the developmental origin of pericytes in multiple tissues, including neck and shoulder [15], thymus [16], spinal cord [17], muscle, and dermis [18], was recently identified as the neural crest. In the tendon, Tempfer et al. reported that some perivascular cells express both tendon- and stem cell-related markers [13]. Matsumoto et al. suggested that vascular-related stem cells reside in the anterior cruciate ligament and could contribute to primary ligament healing [12]. By the label-retaining method, Tan et al. also demonstrated that some tendon stem cells are identified at the perivascular niche and participate in tendon repair after injury [28]. In the present study, we showed that the P75+ cells inhabit the perivascular niche and increase markedly after injury. Ultrastructural analysis illustrated deposition of perivascular cell-derived ECM in the resulting fibrotic scar. However, P75 expression did not colocalize with CD146 and NG2 expressions in the tendon, which are commonly used markers for pericytes in many tissues. Further investigation would be performed in our future studies.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Song Li (University of California, Berkeley, USA) and Zhenyu Tang (Shanghai Advanced Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Science, People's Republic of China) for their helpful comments and suggestions on the manuscript. This work was supported by grants from the Innovation and Attracting Talents Program for College and University (“111” Project) (B06023), National Natural Science Foundation of China (11032012, 10902130, and 30870608), Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (CQDXWL-2014-007), Visiting Scholar Foundation of Key Laboratory of Biorheological Science and Technology (Chongqing University), Ministry of Education (CQKLBST-2014-003), and NIH grants RO1 AR 47364 and AR 60306 (for C.M.C.).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Butler DL, Juncosa-Melvin N, Boivin GP, Galloway MT, Shearn JT, Gooch C. and Awad H. (2008). Functional tissue engineering for tendon repair: a multidisciplinary strategy using mesenchymal stem cells, bioscaffolds, and mechanical stimulation. J Orthop Res 26:1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Butler DL, Juncosa N. and Dressler MR. (2004). Functional efficacy of tendon repair processes. Annu Rev Biomed Eng 6:303–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hildebrand KA. and Frank CB. (1998). Scar formation and ligament healing. Can J Surg 41:425–429 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bi Y, Ehirchiou D, Kilts TM, Inkson CA, Embree MC, Sonoyama W, Li L, Leet AI, Seo BM, et al. (2007). Identification of tendon stem/progenitor cells and the role of the extracellular matrix in their niche. Nat Med 13:1219–1227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang J. and Wang J. (2010). Characterization of differential properties of rabbit tendon stem cells and tenocytes. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 11:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rui YF, Lui PP, Li G, Fu SC, Lee YW. and Chan KM. (2010). Isolation and characterization of multipotent rat tendon-derived stem cells. Tissue Eng 16:1549–1558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lovati AB, Corradetti B, Lange Consiglio A, Recordati C, Bonacina E, Bizzaro D. and Cremonesi F. (2011). Characterization and differentiation of equine tendon-derived progenitor cells. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents 25:S75–S84 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ni M, Lui PP, Rui YF, Lee YW, Tan Q, Wong YM, Kong SK, Lau PM, Li G. and Chan KM. (2012). Tendon-derived stem cells (TDSCs) promote tendon repair in a rat patellar tendon window defect model. J Orthop Res 30:613–619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ni M, Rui YF, Tan Q, Liu Y, Xu LL, Chan KM, Wang Y. and Li G. (2013). Engineered scaffold-free tendon tissue produced by tendon-derived stem cells. Biomaterials 34:2024–2037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shen W, Chen J, Yina Z, Chen X, Liua H, Heng BC, Chen W. and Ouyang HW. (2012). Allogenous tendon stem/progenitor cells in silk scaffold for functional shoulder repair. Cell Transplant 21:943–958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yin Z, Chen X, Chen JL, Shen WL, Hieu Nguyen TM, Gao L. and Ouyang HW. (2009). The regulation of tendon stem cell differentiation by the alignment of nanofibers. Biomaterials 31:2163–2175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matsumoto T, Ingham SM, Mifune Y, Osawa A, Logar A, Usas A, Kuroda R, Kurosaka M, Fu FH. and Huard J. (2011). Isolation and characterization of human anterior cruciate ligament-derived vascular stem cells. Stem Cells Dev 21:859–872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tempfer H, Wagner A, Gehwolf R, Lehner C, Tauber M, Resch H. and Bauer HC. (2009). Perivascular cells of the supraspinatus tendon express both tendon- and stem cell-related markers. Histochem Cell Biol 131:733–741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mienaltowski MJ, Adams SM. and Birk DE. (2013). Regional differences in stem cell/progenitor cell populations from the mouse Achilles tendon. Tissue Eng Part A 19:199–210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsuoka T, Ahlberg PE, Kessaris N, Iannarelli P, Dennehy U, Richardson WD, McMahon AP. and Koentges G. (2005). Neural crest origins of the neck and shoulder. Nature 436:347–355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muller SM, Stolt CC, Terszowski G, Blum C, Amagai T, Kessaris N, Iannarelli P, Richardson WD, Wegner M. and Rodewald HR. (2008). Neural crest origin of perivascular mesenchyme in the adult thymus. J Immunol 180:5344–5351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goritz C, Dias DO, Tomilin N, Barbacid M, Shupliakov O. and Frisen J. (2011). A pericyte origin of spinal cord scar tissue. Science 333:238–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dulauroy S, Di Carlo SE, Langa F, Eberl G. and Peduto L. (2012). Lineage tracing and genetic ablation of ADAM12(+) perivascular cells identify a major source of profibrotic cells during acute tissue injury. Nat Med 18:1262–1270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu W, Wang Y, Liu E, Sun Y, Luo Z, Xu Z, Liu W, Zhong L, Lv Y, et al. (2013). Human iPSC-derived neural crest stem cells promote tendon repair in a rat patellar tendon window defect model. Tissue Eng Part A 19:2439–2451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tang Z, Wang A, Yuan F, Yan Z, Liu B, Chu JS, Helms JA. and Li S. (2012). Differentiation of multipotent vascular stem cells contributes to vascular diseases. Nat Commun 3:875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee BL, Tang Z, Wang A, Huang F, Yan Z, Wang D, Chu JS, Dixit N, Yang L. and Li S. (2013). Synovial stem cells and their responses to the porosity of microfibrous scaffold. Acta Biomater 9:7264–7275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen X, Song XH, Yin Z, Zou XH, Wang LL, Hu H, Cao T, Zheng MH. and Ouyang HW. (2009). Stepwise differentiation of human embryonic stem cells promotes tendon regeneration by secreting fetal tendon matrix and differentiation factors. Stem Cells 27:1276–1287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tavian M, Zheng B, Oberlin E, Crisan M, Sun B, Huard J. and Peault B. (2005). The vascular wall as a source of stem cells. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1044:41–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crisan M, Yap S, Casteilla L, Chen CW, Corselli M, Park TS, Andriolo G, Sun B, Zheng B, et al. (2008). A perivascular origin for mesenchymal stem cells in multiple human organs. Cell Stem Cell 3:301–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stemple DL. and Anderson DJ. (1992). Isolation of a stem cell for neurons and glia from the mammalian neural crest. Cell 71:973–985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee G, Kim H, Elkabetz Y, Al Shamy G, Panagiotakos G, Barberi T, Tabar V. and Studer L. (2007). Isolation and directed differentiation of neural crest stem cells derived from human embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotechnol 25:1468–1475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnston AP, Naska S, Jones K, Jinno H, Kaplan DR. and Miller FD. (2013). Sox2-mediated regulation of adult neural crest precursors and skin repair. Stem Cell Rep 1:38–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tan Q, Lui PP. and Lee YW. (2013). In vivo identity of tendon stem cells and the roles of stem cells in tendon healing. Stem Cells Dev 22:3128–3140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Potenza AD. (1963). Critical evaluation of flexor-tendon healing and adhesion formation within artificial digital sheaths. J Bone Joint Surg 45:1217–1233 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones ME, Mudera V, Brown RA, Cambrey AD, Grobbelaar AO. and McGrouther DA. (2003). The early surface cell response to flexor tendon injury. J Hand Surg Am 28:221–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lundborg G. (1976). Experimental flexor tendon healing without adhesion formation—a new concept of tendon nutrition and intrinsic healing mechanisms. A preliminary report. Hand 8:235–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manske PR, Gelberman RH, Vande Berg JS. and Lesker PA. (1984). Intrinsic flexor-tendon repair. A morphological study in vitro. J Bone Joint Surg Am 66:385–396 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kajikawa Y, Morihara T, Watanabe N, Sakamoto H, Matsuda K, Kobayashi M, Oshima Y, Yoshida A, Kawata M. and Kubo T. (2007). GFP chimeric models exhibited a biphasic pattern of mesenchymal cell invasion in tendon healing. J Cell Physiol 210:684–691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gelberman RH, Vande Berg JS, Lundborg GN. and Akeson WH. (1983). Flexor tendon healing and restoration of the gliding surface. An ultrastructural study in dogs. J Bone Joint Surg Am 65:70–80 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dupin E. and Coelho-Aguiar JM. (2013). Isolation and differentiation properties of neural crest stem cells. Cytometry A 83:38–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rouget C-MB. (1874). Note sur le developpement de la tunique contractile des vaisseaux. Compt Rend Acad Sci 59:559–562 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dore-Duffy P. and Cleary K. (2011). Morphology and properties of pericytes. Methods Mol Biol 686:49–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]