Abstract

Vascular derivatives of human embryonic stem cells (hESC) are being developed as sources of tissue-specific cells for organ regeneration. However, identity of developmental pathways that modulate the specification of endothelial cells is not known yet. We studied phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)-Forkhead box O transcription factor 1A (FOXO1A) pathways during differentiation of hESC toward endothelial lineage and on proliferation, maturation, and cell death of hESC-derived endothelial cells (hESC-EC). During differentiation of hESC, expression of FOXO1A transcription factor was linked to the expression of a cluster of angiogenesis- and vascular remodeling-related genes. PI3K inhibitor LY294002 activated FOXO1A and induced formation of CD31+ hESC-EC. In contrast, differentiating hESC with silenced FOXO1A by small interfering RNA (siRNA) showed lower mRNA levels of CD31 and angiopoietin2. LY294002 decreased proliferative activity of purified hESC-EC, while FOXO1A siRNA increased their proliferation. LY294002 inhibits migration and tube formation of hESC-EC; in contrast, FOXO1A siRNA increased in vitro tube formation activity of hESC-EC. After in vivo conditioning of cells in athymic nude rats, cells retain their low FOXO1A expression levels. PI3K/FOXO1A pathway is important for function and survival of hESC-EC and in the regulation of endothelial cell fate. Understanding these properties of hESC-EC may help in future applications for treatment of injured organs.

Introduction

Vascularisation of ischemic or engineered tissues is indispensable for cell viability, survival, and good functional integration of cells following transplantation therapies [1]. Therapeutic angiogenesis or vasculogenesis with autologous cell transplantation using bone marrow-derived or circulating blood-derived progenitor cells was shown to have beneficial effects in clinical trials [2]. However, the number and function of these cells might limit the efficiency of autologous stem cell therapy. Human pluripotent stem cells such as embryonic stem cells (hESC) could serve as future therapeutic source for vascular cell therapies replacing damaged tissues because of their major proliferative and differentiation potential. These cells are able to give rise to several cell types of the cardiovascular system such as cardiomyocytes, smooth muscle cells, or endothelial cells [3,4]. Since the first generation of hESC-derived endothelial cells (hESC-EC), several studies demonstrated the ability of hESC lines to differentiate toward endothelial lineage [5,6]. However, key signals regulating differentiation, function, and survival of hESC-derived cells still need to be explored.

Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), a lipid kinase, has been shown to play an important role in regulating cell proliferation, adhesion, DNA repair, senescence, and stemness [7]. PI3K is highly suited for pharmacologic intervention, which makes PI3K pathway one of the most attractive therapeutic targets in cancer and diabetes [8,9]. The effect of PI3K in the therapy of cardiovascular diseases has not been tested yet. The members of the Forkhead box O (FOXO) transcription factor family are one of the main downstream components of PI3K pathway [10]. FOXO transcription factors are critical proteins in the regulation of pluripotency of hESC and in modulation of cardiovascular development [11–13]. FOXO transcription factors are involved in response to oxidative stress, in cell survival, cell cycle, and angiogenesis [14–16]. Forkhead box O transcription factor 1A (FOXO1A)-deficient embryos die around embryonic day 11 because of their inefficient vascular and cardiac systems [17]. FOXO1A is also important in regulation of endothelial cell fate. Indeed, it has been found that mouse embryonic stem cell-derived endothelial cells lacking FOXO1A are unable to respond to vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), an important angiogenic growth factor for normal vascular development [16].

The aim of our study was to examine the changes of genes related to PI3K-FOXO1A pathways, investigate the role of FOXO1A during differentiation of hESC toward endothelial lineage, and describe the impact of modulation of FOXO1A on proliferation, maturation, and cell death of hESC-EC. A better understanding of PI3K-FOXO1A-related signaling control of specification of human endothelial cells can provide a therapeutic advantage in cell transplantation and tissue engineering.

Materials and Methods

hESC culture and differentiation toward endothelial cells

hESC (H7; Wicell Bank) were maintained in feeder-free conditions as described previously [18]. Undifferentiated cells were plated onto Matrigel (BD Sciences)-coated six-well plates and fed with mouse embryonic fibroblast-conditioned medium supplemented with 8 ng/mL of recombinant human basic fibroblast growth factor (Invitrogen). Before induction of differentiation, spontaneously differentiated cells were removed by treatment with dispase at 37°C for up to 7 min. Differentiation of hESC-EC were carried out as described previously [19]. Human ESC colonies were mechanically broken with a 5 mL pipette tip and were placed into low-attachment six-well plates in medium containing 2% fetal calf serum [endothelial growth medium-2 (EGM2); Lonza] for 4 days to form embryoid bodies (EB). EGM2 media was prepared by addition of SingleQuot supplements and growth factors to EBM2 basal medium. Supplements included human epidermal growth factor, gentamicin-amphotericin-B 100, R3- insulin growth factor-1, ascorbic acid, VEGF, human fibroblast growth factor-B, heparin, and hydrocortisone. EBs were seeded on gelatine-coated flasks. CD31+ cells were sorted by a cell sorter (BD FACSAria; BD Biosciences) from cultures 13 days after differentiation [20] and expanded in EGM2. For antibody titration, IgG1K-APC isotype control (IC002a; R&D Systems) was used. The medium was changed in every 2 days. Passages between 4 and 9 were used for experiments. Human umbilical cord vein cells (HUVEC), used as control endothelial cells, were a gift from Caroline Wheeler-Jones (Royal Veterinary College, London) and were maintained in EGM2 and used between passages 3 and 11. Human coronary arterial endothelial cells (HCAEC) were purchased from Lonza.

Cell treatments with PI3K inhibitor, FOXO1A small interfering RNA, and FOXO1A plasmid

Human ESC were treated with LY294002 (10 μM, medium changed every 24 h; Sigma) during endothelial differentiation. Dimethyl sulfoxide was used as control in the same concentration. Human ESC-EC were plated onto 0.5% gelatinized 96-well plates at a density of 10,000 cells/well and grown to confluence. The CD31+ cells were treated with LY294002 (10 μM) for 24 h. H2O2 was used as a stable reactive oxygen species for induction of cell death in three different concentrations (high dose, 900 μM; medium dose, 300 μM; low dose, 100 μM) for 12 h. For FOXO1A small interfering RNA (siRNA) knockdown on differentiating hESC and purified hESC-EC cultures, FOXO1A Flexitube siRNA Premix (10 nM, 6 and 24 h; Qiagen) was performed as per manufacturer's instruction. Scrambled nontargeting (NT) siRNA (10 nM; Qiagen) was used as negative control. Differentiating hESC cultures were retransfected every 48 h to maintain the effects of siRNA.

Transfection of hESC-EC with plasmids encoding FOXO1A-eGFP [21] or pmaxGFP (Lonza) used as DNA control was carried out by electroporation. Briefly, 106 hESC-EC were resuspended in 400 μL of EGM2 medium (Lonza) containing 5 μg plasmid DNA, electroporated on a Gene Pulser Xcell Total modular electroporation apparatus (BioRad) using time constant program (200 v, 25 ms). Assessment of overexpression efficiency by TaqMan real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and experiments were performed 48 h later.

Matrigel tube-formation assay

Matrigel (BD Biosciences) was thawed on ice overnight and 24-well plates were coated with 200 μL Matrigel per well and then allowed to solidify at 37°C for 30 min. Control, LY294002, NT, or FOXO siRNA-pretreated hESC-EC (50,000 cells/well) were plated onto Matrigel and cultures were photographed and quantitated after 24 h of incubation.

Angiogenesis and soluble receptor proteome profiling

Angiogenesis proteome profiling was carried out with Proteome Profiler Human Angiogenesis Array Kit (ARY007; R&D Systems). The human soluble receptor proteome profiling array was performed with Human Soluble Receptor Array Kit Hematopoietic Panel (ARY011; R&D Systems). The sample preparation and experimental setup followed the product catalogue guide. Proteome profile of hESC-ECs was compared with control HCAEC. Pixel densities of the X-ray films were analyzed by ImageJ software.

Colony formation assay

Cultures of hESC-EC were dissected into single cells, filtered through a 40-μm cell strainer (BD Falcon), and 5,000 isolated cells were plated on gelatin into each well of 96-well plates. Cells were treated with LY294002 or FOXO1A siRNA or overexpressed with FOXO1A-eGFP. Plates were stained for Hoechst at day 0, 1, 2, and 3. The colony formation activity and the number of nuclei per colony were assessed by using a Colony Formation BioApplication on Cellomics platform.

In vivo transplantation by Matrigel plug assay

Human ESC-EC and HUVEC were cultured in vitro and 106 cells/plug were subcutaneously injected into 3-month-old athymic nude rats (Crl:NIH-Foxn1rnu; Charles River) in a suspension of Matrigel (250 μL), heparin (64 U/mL), recombinant murine basic FGF (80 ng/mL; R&D Systems), and EGM2 (70 μL). Matrigel suspension without cells was used as control. The injection sites were four parts of the abdominal subcutaneous region. After 3 weeks, rats were sacrificed; plugs were harvested and stored at −80°C for immunohistochemistry or RNA isolation. The experimental protocols were approved by the Animal Use and Care Committee of Semmelweis University, Budapest. The investigation conforms to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the U.S. National Institutes of Health.

Immunocytochemistry and ac-LDL-uptake

Endothelial cells were plated into 96-well plates and after treatments cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature (RT), permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 10 min, and blocked with 4% fetal bovine serum in phosphate-buffered saline for 1 h at RT. Cells were stained for immunocytochemistry for CD31 (1:100; Santa Cruz), FOXO1A (1:200; Millipore), ve-cadherin (1:100; Abcam), CD45 (1:100; Abcam), and Ki67 (1:100; Abcam) using rabbit anti-human polyclonal antibodies for 1 h at RT. Primary antibodies were detected with Alexa 488- and Alexa 546-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:400; Life Technologies) for 45 min at RT. Hoechst 33342 (1:1,000; Life Technologies) was used for staining nucleus. For confirmation of ve-cadherin, cells were transfected with ve-cadherin-driven eGFP construct [22] and visualized using confocal microscopy after 2 days.

For further identifying endothelial phenotype, cells were incubated with 10 μg/mL DiI-labeled acetylated low-density lipoprotein (DiI-Ac-LDL; Invitrogen) contained EGM-2 medium for 4 h at 37°C, then washed twice with EGM-2 medium, and observed by fluorescent microscope (Zeiss Axio Observer Z1).

For the measurement of cytoplasm to nuclear translocation of FOXO1A [23], hESC were stained with anti-FOXO1A antibody and plates were scanned using automated high content screening reader Cellomics VTi HCS ArrayScanner (Thermo Scientific). The arrayscanner is an automated fluorescence microscope that provides comprehensive data on the spatial and temporal distribution of fluorescence intensities in culture plates. Hoechst staining was used to define the nucleus [24]. Binary image masks were created also for FOXO1A staining to define regions of interest for analysis. Mean nuclear-cytosolic intensities of FOXO1A were measured and calculated using Compartmental Analysis Bioapplication in at least 1,000 cells/well across up to 49 fields/well of a 96-well plate. Hoechst and FOXO1A fluorescence were captured using sequential acquisition to give separate image files for each. Some wells were treated with secondary antibody to establish background autofluorescence. Representative images are shown in Supplementary Fig. S1 (Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd).

For live imaging for measuring parameters of cell death, supernatant was removed, and hESC-EC and HUVEC were stained with TOTO-1 or TO-PRO3 (1:1,000; Life Technologies) and Hoechst 33342 (1:1,000; Life Technologies) for 10 min in EGM2 medium. Fresh serum-free medium was added after 1 h. Change in nuclear morphology is a hallmark of the final stage in cell death. Nuclear events were recorded as additional toxicity readouts regardless of the cell death pathway involved.

Real-time PCR

Cells were lysed in TriReagent (Invitrogen) and total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen). To generate single-stranded cDNA, High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems) was used and for quantifying Oct4, FOXO1A, CD31, Tie2, and angiopoietin2 (Ang2) real-time PCR analyses were performed with TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (Oct4: Hs00999634_gH; FOXO1A: Hs00231106_m1, CD31: Hs00169777_m1; Ang2: Hs01048043_m1, Tie2: Hs00945142_m1; Applied Biosystems). Human GAPDH Endogenous Control (FAM/MGB probe; Applied Biosystems) was used as a housekeeping control. The PCR was performed with Rotor-Gene 3000 (Corbett Research) and StepOnePlus (Applied Biosystems) real-time PCR instruments and the relative expression was determined by ΔΔCt method in which fold increase=2−ΔΔCt.

For the PCR array (Human PI3K-AKT Signaling RT2 Profiler PCR Array Kit, PAHS-058; SA Biosciences), cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA and then hybridized in a 96-well format. PCR array data intensity values were normalized by gene-centered z score transformation. A modified z-score threshold of 3.5 was used as criteria defining outliers, and these samples were excluded from a rerun of the z-statistics. By calculating the gene expression stability measure M, which is the mean pairwise variation for a gene from all other tested genes, ACTB and RPL13A were accepted as being the most stable housekeeping ones. Normalized ΔCT values were derived as ΔCT (gene)−ΔCT (averaged geometric mean between above housekeeping controls). Correlation plots and heatmaps were plotted for all samples and technical replicates were averaged. To reveal biologically relevant interactions for activated kinases, pathway analysis was performed by Ingenuity Pathways Analysis software (https://analysis.ingenuity.com). Ingenuity Pathways are based on a curated database of published literature on gene functions and interactions. As one of the outputs Ingenuity identifies hub genes based on high degree of links to other genes in known pathways.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean±SEM. Experiments were carried out in triplicates. Statistical analyses were performed by Student's t-test or analysis of variance with Tukey post hoc test. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

PI3K/Akt/FOXO1A pathway during endothelial differentiation of hESC

We differentiated hESC toward endothelial lineage and used FACS to isolate CD31+ cells at day 13 after initiation of differentiation. We found that mRNA levels of OCT4, an embryonic stem cell marker, were gradually decreased in differentiating hESC and in differentiated hESC-derived CD31+ cells (Fig. 1A). Expression of CD31 and key angiogenic factor angiopoietin2 showed marked upregulation during differentiation of hESC toward endothelial cells; however, it did not bring expression levels to those of HUVEC used as control endothelial cell (Fig. 1A). Levels of the angiopoietin1 receptor Tie2 showed only modest increase during the differentiation (Fig. 1A). To investigate the changes of genes related to PI3K pathway during endothelial differentiation of hESC, we analyzed the expressions of main PI3K genes using a quantitative PCR array. Undifferentiated and differentiating hESC (EB, at day 4), and sorted CD31+ hESC-EC showed different expression levels of most genes tested in this pathway (Fig. 1B). Undifferentiated hESC expressed high mRNA levels of FOXO1A transcription factor; this critical downstream element of PI3K pathway was strongly downregulated during differentiation. When compared to HUVEC, we found matching expression levels of most of the PI3K pathway elements in hESC-EC (Fig. 1B, bar graph). We also found that mRNA levels of PI3K-partners such as BTK and CD14 were higher, whereas PIK3R1 and PDGFRA were lower in hESC-EC than those in HUVEC (Fig. 1B, C). To infer gene networks from expression profile of hESC-EC, Ingenuity pathway network analysis was performed. It suggested that FOXO1A expression is specifically linked to an indispensable cluster of angiogenesis- and vascular remodeling-related genes, including VEGF2 and PDK1, cdc42, and PRKCB1 (Fig. 1D). Furthermore, analysis suggests that VEGF may signal through a PTEN/PDGFRA pathway and modulate FOXO1A (Fig. 1D).

FIG. 1.

PI3K/FOXO1A signaling-related gene expression during human embryonic stem cells (hESC) differentiation. hESC were differentiated via embryoid body (EB) formation toward hESC-derived endothelial cells (hESC-EC). HUVEC were used as control endothelial cells. (A) Changes in mRNA levels of embryonic stem cell marker OCT4, CD31, angiogenesis markers angiopoietin2, and Tie2 at different steps of endothelial differentiation. Heat map with agglomerative clustering (B) and bar graphs (C) showing changes in mRNA levels of PI3K/FOXO elements during different steps of endothelial differentiation. Bar graphs in (B) showing differences in gene expression in HUVEC versus those in hESC-EC as a baseline. Data are expressed as fold changes versus mRNA levels in undifferentiated hESC; mean±SEM. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.01, from three biological replicates, one-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test. (D) Schematic diagram of Ingenuity Pathway Analysis-mapped mechanistic interactions of VEGF, PTEN, FOXO1A, and various angiogenic modulator elements. Arrows between nodes represent direct (solid lines) and indirect (dashed lines) interactions between molecules as supported by information in the Ingenuity pathway knowledge base. ANOVA, analysis of variance; FOXO1A, Forkhead box O transcription factor 1A; HUVEC, human umbilical cord vein cells; ITGB1, integrin beta-1; PDGFRA, platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; PIK3R2, phosphoinositide-3-kinase, regulatory subunit 2 beta; PRKCA, protein kinase C alpha; PRKCB, protein kinase C beta; PRKCZ, protein kinase C zeta; PTEN, phosphatase and tensin homolog; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

PI3K/FOXO1A pathway modulates endothelial differentiation of hESC

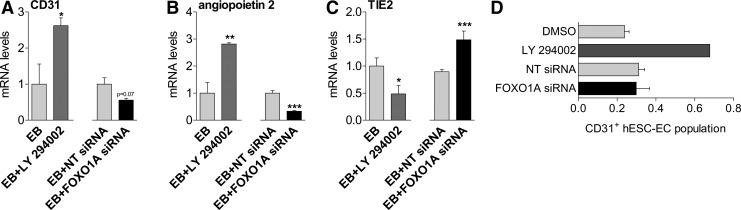

Next, we targeted PI3K/FOXO1A pathway to directly assess its role in endothelial differentiation. Administration of LY294002 during differentiation increased mRNA levels of CD31 and angiopoietin2 in differentiating hESC (Fig. 2A, B). Tie2 mRNA levels were downregulated in response to LY294002 (Fig. 2C). Cells treated with FOXO siRNA, however, showed lower mRNA levels of CD31 (P=0.07) and angiopoietin2 (P<0.001) as compared with NT siRNA group (Fig. 2A, B). Treatment with FOXO siRNA resulted in increased mRNA levels of Tie2 (Fig. 2C). FOXO1A mRNA levels were lower after siRNA treatment on hESC (Supplementary Fig. S2B). Use of PI3K inhibitor/FOXO1A activator LY294002 tended to increase the percentage of newly formed CD31+ hESC-EC in the presence of EGM2 medium, containing endothelial growth factors (LY294002: 0.62%±0.04% vs. 0.24%±0.1% of control differentiating hESC culture; Fig. 2D). LY294002 resulted in higher FOXO1A mRNA levels of differentiating hESC (Supplementary Fig. S2A). By contrast, silencing of FOXO1A by siRNA during differentiation had no influence on the percentage of CD31+ cells (Fig. 2D).

FIG. 2.

PI3K/FOXO1A signaling modulates endothelial differentiation of hESC. Bar graphs showing mRNA levels of CD31 (A), angiopoietin2 (B), and Tie2 (C) in differentiating hESC (EB) with LY294002 and FOXO1A siRNA. (D) Bar graph showing CD31+ hESC-EC population in the presence of FOXO1A siRNA or LY294002 (10 μM). mean±SEM, *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 versus control group, three biological replicates, Student's t-test. siRNA, small interfering RNA.

Modulation of PI3K/FOXO1A signaling pathway in sorted hESC-EC

Cultures of differentiated CD31+ hESC-EC were highly proliferative and showed specific endothelial characteristics such as cobblestone morphology, evidence of DiI-labeled acetylated LDL uptake, and positive expression ve-cadherin-eGFP and staining for ve-cadherin (Supplementary Fig. S3A–D). As assessed by proteome profiler, protein levels of angiogenic and endothelial factors showed similarities in hESC-EC and control adult HCAEC (Supplementary Fig. S4E). Human ESC-EC had low or not detectable levels of hematopoietic markers (Supplementary Fig. S4F). As shown by high content microscopy, hESC-EC did not express the hematopoietic progenitor cell marker CD45 (Supplementary Fig. S4G).

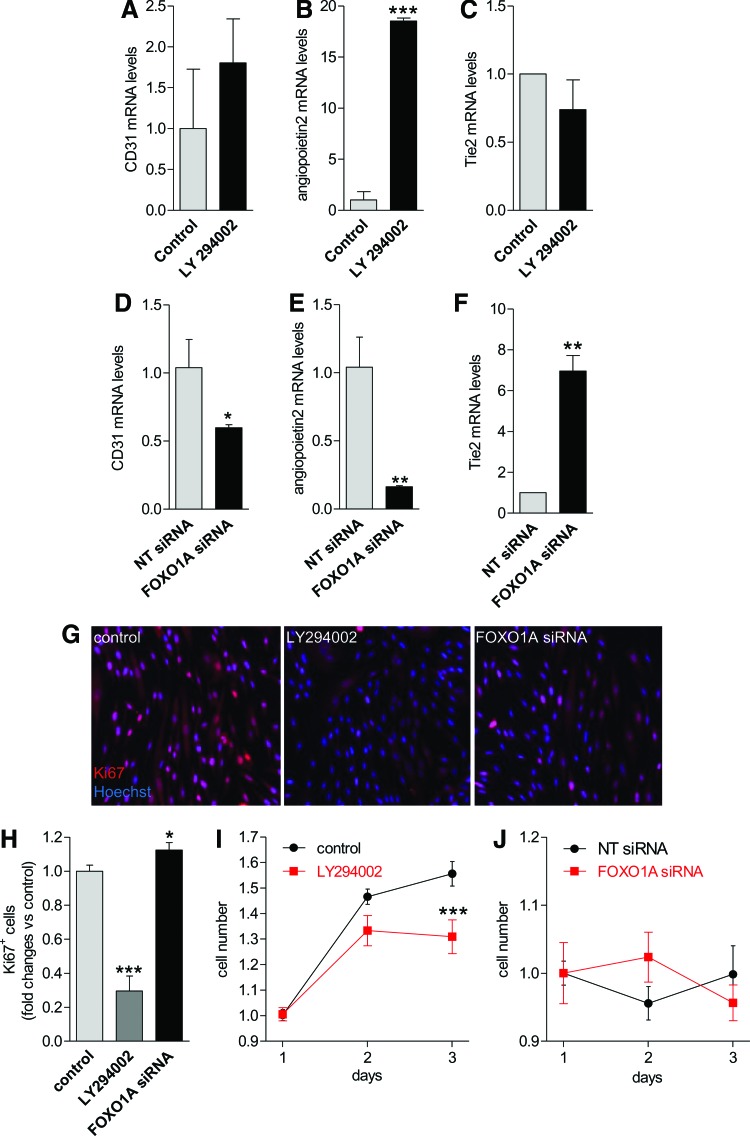

To test the effects of PI3K/FOXO1A modulation in hESC-EC, we treated cells with LY294002 or FOXO1A siRNA. Nuclear translocation and mRNA levels of FOXO1A were markedly increased in hESC-EC in response to LY294002 (Supplementary Fig. S2C, D). In contrast, silencing of FOXO1A with siRNA decreased both mRNA and nuclear translocation levels of FOXO1A as early as after 6 h treatment in hESC-EC (Supplementary Fig. S2E, F). Similar to differentiating hESC, mRNA levels of CD31 tended to increase in response to LY294002 and decreased in cells with FOXO siRNA (Fig. 3A, D). Angiopoietin2 mRNA were also increased in response to LY294002 in hESC-EC; on the other hand, FOXO siRNA resulted in lower mRNA levels of angiopoietin2 (Fig. 3B, E). The mRNA levels of the Tie2 were inversely regulated compared with angiopoietin2 (Fig. 3C, F).

FIG. 3.

PI3K/FOXO1A signaling modulates proliferative activity of hESC-EC. Bar graphs showing changes in mRNA levels of CD31, angiopoietin2, and Tie2 in differentiated hESC-EC in response to 24 h treatment with LY294002 (A–C) or FOXO1A siRNA (D–F). (G) Representative picture of Ki67+ cells in hESC-EC population (magnification: 20×). Changes in proliferation rate of the hESC-EC population (Ki67+ cells) after 24 h (H) and in colony formation activity (I, J) in response to LY294002 or FOXO1A siRNA treatments for 3 days. Data are expressed as fold changes versus percentage of Ki67+ cells in control hESC-EC group, mean±SEM. Fold changes in mRNA levels are shown versus hESC. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 versus control, n=3 biological replicates. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

Proliferative activity of sorted hESC-EC cultures were assessed by Ki67 marker and colony formation. Percentage of Ki67+ cells and colony formation activity after 3 days were significantly decreased in response to LY294002 (Fig. 3G–I); in contrast, further downregulation of FOXO1A expression by siRNA treatment resulted in a modest increase in the ratio of Ki67+ cells (P<0.05) with no effect on cell number (Fig. 3G, H, J). Overexpression of FOXO1A alone did not change the ratio of Ki67-positive cells and colony formation in hESC-EC population (Supplementary Fig. S4A, B). This may suggest distinct role of PI3K/FOXO1A pathway in cell generation during hESC differentiation compared with those in a later stage in sorted hESC-EC.

Targeting PI3K/FOXO1A pathway alters hESC-EC viability

Next, we tested the role of PI3K/FOXO1A pathway on viability and cell survival of hESC-EC. As assessed by high content microscopy, oxidative stress induced by H2O2 activated FOXO1A as shown by its increased nuclear density (Supplementary Fig. S5A, B). Using H2O2 as a danger signal caused necrosis and nuclear remodeling (expressed as decreased nuclear size) in a dose-dependent manner in hESC-EC (Supplementary Fig. S5C, D). Silencing of FOXO1A by siRNA had no effect on levels of necrosis marker TOTO1 or nuclear remodeling in hESC-EC (P<0.05, Supplementary Fig. S5C, D). Pretreatment with LY294002 increased the pro-necrotic effects of H2O2 (at a dose of 600 μM, P<0.001) in hESC-EC. Overexpression of FOXO1A resulted in higher levels of necrosis compared with those in control plasmid-transfected hESC-EC (Supplementary Fig. S4C–E). The level of necrosis in response to H2O2 was not modulated by FOXO1A overexpression. Using LY294002 without external danger signal (such as H2O2) had no effect on viability of hESC-EC (Supplementary Fig. S5C, D).

PI3K/FOXO1A pathway modulates angiogenic activity of hESC-EC

In vitro tube formation assay revealed that LY294002 inhibits hESC-EC migration and formation of tubes (Fig. 4A–D). On the other hand, silencing of FOXO1A by siRNA markedly increased in vitro tube formation activity of hESC-EC as shown by total tube length and node count (P<0.001, Fig. 4A, E–G). Overexpression of FOXO1A did not alter tube formation activity of hESC-EC (Supplementary Fig. S4F–H). To test the viability and maturation of hESC-EC with low FOXO1A levels also in vivo, cell were transplanted into athymic nude rats. Human ESC-EC showed engraftment (Fig. 4H); after 21 days conditioning of cells, angiopoietin2 and Tie2 mRNA levels were markedly increased in hESC-EC similar to those in control HUVEC (Fig. 4J, K). However, hESC-EC retain their low FOXO1A expression levels during the incubation period (Fig. 4I), whereas FOXO1A mRNA levels are further increased in HUVEC.

FIG. 4.

In vitro angiogenesis and in vivo conditioning of hESC-EC. (A) Representative Matrigel tube formation images of hESC-EC pretreated with LY294002 or FOXO1A siRNA. Cells were stained with vital dye TMRM (red). Bar graph showing average and total tube lengths and number of formed nodes after LY294002 (B–D) 24 h FOXO1A or nontargeting scrambled (NT) siRNA (E–G). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 versus control, n=3 biological replicates. (H) Representative image of histological section stained with hematoxylin-eosin showing subcutaneously engrafted hESC-EC. (I–K) Bar graphs showing FOXO1A, angiopoietin2 and Tie2 mRNA levels before and after in vivo conditioning of hESC-EC in Matrigel plugs transplanted into athymic nude rats. Data are mean±SEM [n=3–10 per group from two independent experiments (12 rats per group)]. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

Discussion

The underlying intracellular signaling mechanisms in the generation and function of human pluripotent stem cell-derived endothelial cells have not been described in detail. In this study we showed that PI3K pathway is one of the key intracellular signaling mechanisms that have wide-ranging effects on endothelial differentiation of hESC in addition to cell death, proliferation, and angiogenic activity of generated hESC-EC partially through FOXO1A transcription factor (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Mechanism of action and effects of modulation of PI3K-FOXO1A signaling pathway. Schematic summary shows that activation of FOXO1A with PI3K inhibitor LY294002 resulted in increased yield of endothelial differentiation (labeled as red panels). Proliferative and tube formation capacity decreased (labeled as blue panels) in the differentiated endothelial cells. Modulation of PI3K-FOXO1A signaling also altered angiopoietin2-Tie2 system in the differentiating culture. Low FOXO1A levels increased proliferative activity and tube formation of the developed hESC-EC. FOXO siRNA had no effect (gray panels) on differentiation and cell death profile. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

The role of PI3K in generating new endothelial cells was supported by our observation that hESC differentiation toward endothelial lineage is accompanied by marked changes in expression of most of the genes related to PI3K/FOXO1A pathways. FOXO1A was shown to be the most abundant FOXO member at mRNA levels in undifferentiated hESC colonies and alteration of FOXO1A causes different expression of pluripotency genes in hESC indicating FOXO1A has a critical role in the regulation of hESC fate [11]. Indeed, here we showed that high FOXO1A expression was significantly downregulated during EB formation and further differentiation into endothelial cells. Changes in expression also correlated with loss of pluripotency markers.

By using a gene expression array of PI3K pathway elements, Ingenuity pathway analysis with a curated database and subsequent clustering as an exploratory tool, we identified connections between FOXO1A and VEGF in addition to various angiogenic factors. Time development during differentiation modulated the expression of angiogenic factors clustered with FOXO1A such as PDK1, which play a role in vascular remodeling and endothelial differentiation [25]; cdc42, known to mediate tubulogenesis [26]; protein kinase C beta, being a stimulus for endothelial proliferation [27]; and activation of Rheb/mTOR for endothelial cell transformation [28]. As a potential result of these interactions, we found that inhibition of PI3K and consequent reactivation of FOXO1A by LY294002 resulted in an increased number of newly formed endothelial cells. Higher FOXO1A levels were accompanied by increasing CD31 and angiopoietin2 expression levels in addition to an inverse downregulation in Tie2 levels in the differentiating culture. This suggests an indirect link between FOXO1A levels and the propensity of differentiating hESC toward endothelial lineage. The fact, however, that the control endothelial HUVEC expressed FOXO1A at a higher level than hESC-EC suggests that post-transcriptional control of FOXO1A is more important in HUVEC than those in hESC-EC.

The role of FOXO1A in endothelial development was further evidenced by siRNA silencing experiments. Directly targeting FOXO1A factor decreased expression of endothelial cell markers and angiogenesis genes. This also suggests that culture medium containing VEGF and other endothelial cytokines may be a potent stimulus for endothelial differentiation where PI3K/FOXO1A pathway, at least in part, mediates these signals. This is similar to other studies, where VEGF was shown to increase the yield of adult endothelial cells in differentiated hESC culture [29] and can also favor endothelial cell survival, proliferation, and cell cycle progression via the PI3K/Akt pathway during tissue regeneration and disease [30,31].

Intact PI3K signaling and low but detectable FOXO1A levels may be prerequisites for endothelial differentiation. However, our data suggest a different regulatory role for PI3K/FOXO1A in differentiating ESC and ESC-derived endothelial cells where FOXO1A has a mainly inhibitory feedback signal. We characterized the temporal expression of FOXO1A and angiopoietin2, one of the FOXO1A target genes [32–34] and related to angiogenesis and vascular remodeling, during in vivo differentiation and maturation of hESC-EC. Three weeks after transplantation of hESC-EC into athymic nude rats, cells showed engraftment and were detectable with histology. As opposed to HUVEC, we detected high angiopoietin2 and Tie2 expressions, with no significant change in FOXO1A levels in hESC-EC. In vitro differentiation of hESC generated a unique endothelial cell type, where FOXO1A levels are significantly lower than those in control HUVEC, endothelial cells derived from human umbilical cord vein. This may suggest that these cells retain low FOXO1A levels and a controllable angiogenic activity even after in vivo conditioning. On contrary, we found that activation of FOXO1A by LY294002 blocked tube formation in culture. This activity may be further modulated by the component that inhibition of PI3K and consequent activation of FOXO1A by LY294002 was also found to block cell proliferation of hESC-EC.

FOXO proteins were shown to be involved in response to oxidative stress, in regulation of apoptosis and cell survival [14–16]. In line with these reports, here we showed that FOXO1A mediates danger signals such as oxidative stress by H2O2 in hESC-EC. Indeed, activation of FOXO1A nuclear translocation by H2O2 was accompanied by cell loss, necrosis, and nuclear remodeling in a dose-dependent manner. Furthermore, overexpression of FOXO1A construct showed direct pronecrotic effects and cell loss in hESC-EC cultures. This may suggest that FOXO1A can act as one of the downstream pathways for oxidative stress in hESC-EC. The fact that FOXO1A expression levels stayed low during cell transplantation may suggest that these cells have lower responsiveness to in vivo danger signals. On the other hand, we found that silencing of FOXO1A had no protective effect on stress responsiveness of hESC-EC in vitro, which altogether suggests the presence of a broader regulation involving other, FOXO1A-independent pathways in stress-responsiveness in hESC-EC. LY294002 is one of the potent and specific cell-permeable inhibitor of PI3K [35]. We have found that inhibition of PI3K pathway by LY294002 further increased loss of hESC-EC in oxidative stress. This observation may be in line with earlier animal studies where development of dermal toxicity was an in vivo side effect of LY294002 in murine model [36]; together with low solubility and bioavailability prevented its use in clinical trials. However, several further compounds are being developed to inhibit different nodes of the PI3K pathway. These mainly PI3K/AKT/mTOR inhibitors showed no unexpected toxic effects [8]. However, no clear correlation between endothelial function and vascular damage, and responsiveness to PI3K/AKT/mTOR inhibitors has emerged from early clinical trials. It is also still unclear whether downregulation of PI3K signaling will be sufficient to produce a clinical response.

In conclusion, hESC-EC represent a unique endothelial population, with controllable proliferative and angiogenic activities. PI3K/FOXO1A pathway is one of the particular key signaling elements for function and survival of hESC-EC but also in regulation of endothelial cell fate. We found that activated FOXO1A has various effects in hESC-EC: it mediates endothelial generation; on the other hand, FOXO1A, at least partly, inhibits proliferation and angiogenic activity, and plays a role in response to oxidative stress. To test whether using of cells along with direct pharmacological inhibition of FOXO to release negative feedback may be advantageous in cell therapy still need to be determined.

Acknowledgments

Project was supported by the British Heart Foundation, the Hungarian Scientific Research Fund (MB08A 81237, 105555), and the National Development Agency (TÁMOP-4.2.2/B-10/1-2010-0013).

Supplementary Material

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Levenberg S. (2005). Engineering blood vessels from stem cells: recent advances and applications. Curr Opin Biotechnol 16:516–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leeper NJ, Hunter AL. and Cooke JP. (2010). Stem cell therapy for vascular regeneration: adult, embryonic, and induced pluripotent stem cells. Circulation 122:517–526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kehat I, Kenyagin-Karsenti D, Snir M, Segev H, Amit M, Gepstein A, Livne E, Binah O, Itskovitz-Eldor J. and Gepstein L. (2001). Human embryonic stem cells can differentiate into myocytes with structural and functional properties of cardiomyocytes. J Clin Invest 108:407–414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferreira LS, Gerecht S, Shieh HF, Watson N, Rupnick MA, Dallabrida SM, Vunjak-Novakovic G. and Langer R. (2007). Vascular progenitor cells isolated from human embryonic stem cells give rise to endothelial and smooth muscle like cells and form vascular networks in vivo. Circ Res 101:286–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levenberg S, Zoldan J, Basevitch Y. and Langer R. (2007). Endothelial potential of human embryonic stem cells. Blood 110:806–814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Howard L, Mackenzie RM, Pchelintsev NA, McBryan T, McClure JD, McBride MW, Kane NM, Adams PD, Milligan G. and Baker AH. (2013). Profiling of transcriptional and epigenetic changes during directed endothelial differentiation of human embryonic stem cells identifies FOXA2 as a marker of early mesoderm commitment. Stem Cell Res Ther 4:36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Engelman JA, Luo J. and Cantley LC. (2006). The evolution of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases as regulators of growth and metabolism. Nat Rev Genet 7:606–619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rodon J, Dienstmann R, Serra V. and Tabernero J. (2013). Development of PI3K inhibitors: lessons learned from early clinical trials. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 10:143–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Furman RR, Sharman JP, Coutre SE, Cheson BD, Pagel JM, Hillmen P, Barrientos JC, Zelenetz AD, Kipps TJ, et al. (2014). Idelalisib and rituximab in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med 370:997–1007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brunet A, Bonni A, Zigmond MJ, Lin MZ, Juo P, Hu LS, Anderson MJ, Arden KC, Blenis J. and Greenberg ME. (1999). Akt promotes cell survival by phosphorylating and inhibiting a Forkhead transcription factor. Cell 96:857–868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang X, Yalcin S, Lee DF, Yeh TY, Lee SM, Su J, Mungamuri SK, Rimmele P, Kennedy M, et al. (2011). FOXO1 is an essential regulator of pluripotency in human embryonic stem cells. Nat Cell Biol 13:1092–1099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ronnebaum SM. and Patterson C. (2010). The FoxO family in cardiac function and dysfunction. Annu Rev Physiol 72:81–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maiese K, Chong ZZ, Shang YC. and Hou J. (2009). FoxO proteins: cunning concepts and considerations for the cardiovascular system. Clin Sci (Lond) 116:191–203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kops GJ, Dansen TB, Polderman PE, Saarloos I, Wirtz KW, Coffer PJ, Huang TT, Bos JL, Medema RH. and Burgering BM. (2002). Forkhead transcription factor FOXO3a protects quiescent cells from oxidative stress. Nature 419:316–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakamura T. and Sakamoto K. (2008). Forkhead transcription factor FOXO subfamily is essential for reactive oxygen species-induced apoptosis. Mol Cell Endocrinol 281:47–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Potente M, Urbich C, Sasaki K, Hofmann WK, Heeschen C, Aicher A, Kollipara R, DePinho RA, Zeiher AM. and Dimmeler S. (2005). Involvement of Foxo transcription factors in angiogenesis and postnatal neovascularization. J Clin Invest 115:2382–2392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Furuyama T, Kitayama K, Shimoda Y, Ogawa M, Sone K, Yoshida-Araki K, Hisatsune H, Nishikawa S, Nakayama K, et al. (2004). Abnormal angiogenesis in Foxo1 (Fkhr)-deficient mice. J Biol Chem 279:34741–34749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brito-Martins M, Harding SE. and Ali NN. (2008). beta(1)- and beta(2)-adrenoceptor responses in cardiomyocytes derived from human embryonic stem cells: comparison with failing and non-failing adult human heart. Br J Pharmacol 153:751–759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foldes G, Liu A, Badiger R, Paul-Clark M, Moreno L, Lendvai Z, Wright JS, Ali NN, Harding SE. and Mitchell JA. (2010). Innate immunity in human embryonic stem cells: comparison with adult human endothelial cells. PLoS One 5:e10501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levenberg S, Golub JS, Amit M, Itskovitz-Eldor J. and Langer R. (2002). Endothelial cells derived from human embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99:4391–4396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lara-Pezzi E, Winn N, Paul A, McCullagh K, Slominsky E, Santini MP, Mourkioti F, Sarathchandra P, Fukushima S, Suzuki K. and Rosenthal N. (2007). A naturally occurring calcineurin variant inhibits FoxO activity and enhances skeletal muscle regeneration. J Cell Biol 179:1205–1218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.James D, Nam HS, Seandel M, Nolan D, Janovitz T, Tomishima M, Studer L, Lee G, Lyden D, et al. (2010). Expansion and maintenance of human embryonic stem cell-derived endothelial cells by TGFbeta inhibition is Id1 dependent. Nat Biotechnol 28:161–166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Der Heide LP, Hoekman MF. and Smidt MP. (2004). The ins and outs of FoxO shuttling: mechanisms of FoxO translocation and transcriptional regulation. Biochem J 380:297–309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ding GJ, Fischer PA, Boltz RC, Schmidt JA, Colaianne JJ, Gough A, Rubin RA. and Miller DK. (1998). Characterization and quantitation of NF-kappaB nuclear translocation induced by interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Development and use of a high capacity fluorescence cytometric system. J Biol Chem 273:28897–28905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feng Q, Di R, Tao F, Chang Z, Lu S, Fan W, Shan C, Li X. and Yang Z. (2010). PDK1 regulates vascular remodeling and promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition in cardiac development. Mol Cell Biol 30:3711–3721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kesavan G, Sand FW, Greiner TU, Johansson JK, Kobberup S, Wu X, Brakebusch C. and Semb H. (2009). Cdc42-mediated tubulogenesis controls cell specification. Cell 139:791–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meier R, Alessi DR, Cron P, Andjelkovic M. and Hemmings BA. (1997). Mitogenic activation, phosphorylation, and nuclear translocation of protein kinase Bbeta. J Biol Chem 272:30491–30497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sodhi A, Chaisuparat R, Hu J, Ramsdell AK, Manning BD, Sausville EA, Sawai ET, Molinolo A, Gutkind JS. and Montaner S. (2006). The TSC2/mTOR pathway drives endothelial cell transformation induced by the Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus G protein-coupled receptor. Cancer Cell 10:133–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nourse MB, Halpin DE, Scatena M, Mortisen DJ, Tulloch NL, Hauch KD, Torok-Storb B, Ratner BD, Pabon L. and Murry CE. (2010). VEGF induces differentiation of functional endothelium from human embryonic stem cells: implications for tissue engineering. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 30:80–89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abid MR, Guo S, Minami T, Spokes KC, Ueki K, Skurk C, Walsh K. and Aird WC. (2004). Vascular endothelial growth factor activates PI3K/Akt/forkhead signaling in endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 24:294–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ball SG, Shuttleworth CA. and Kielty CM. (2007). Vascular endothelial growth factor can signal through platelet-derived growth factor receptors. J Cell Biol 177:489–500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Daly C, Pasnikowski E, Burova E, Wong V, Aldrich TH, Griffiths J, Ioffe E, Daly TJ, Fandl JP, et al. (2006). Angiopoietin-2 functions as an autocrine protective factor in stressed endothelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:15491–15496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van der Vos KE. and Coffer PJ. (2011). The extending network of FOXO transcriptional target genes. Antioxid Redox Signal 14:579–592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hurley D, Araki H, Tamada Y, Dunmore B, Sanders D, Humphreys S, Affara M, Imoto S, Yasuda K, et al. (2012). Gene network inference and visualization tools for biologists: application to new human transcriptome datasets. Nucleic Acids Res 40:2377–2398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arcaro A. and Wymann MP. (1993). Wortmannin is a potent phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitor: the role of phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate in neutrophil responses. Biochem J 296 (Pt 2):297–301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hu L, Zaloudek C, Mills GB, Gray J. and Jaffe RB. (2000). In vivo and in vitro ovarian carcinoma growth inhibition by a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitor (LY294002). Clin Cancer Res 6:880–886 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.