Abstract

Background

Red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) have recently been recognized as potential reservoirs of several vector-borne pathogens and a source of infection for domestic dogs and humans, mostly due to their close vicinity to urban areas and frequent exposure to different arthropod vectors. The aim of this study was to investigate the presence and distribution of Babesia spp., Hepatozoon canis, Anaplasma spp., Bartonella spp., ‘Candidatus Neoehrlichia mikurensis’, Ehrlichia canis, Rickettsia spp. and blood filaroid nematodes in free-ranging red foxes from Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Methods

Spleen samples from a total of 119 red foxes, shot during the hunting season between October 2013 and April 2014 throughout Bosnia and Herzegovina, were examined for the presence of blood vector-borne pathogens by conventional PCRs and sequencing.

Results

In the present study, three species of apicomplexan parasites were molecularly identified in 73 red foxes from the entire sample area, with an overall prevalence of 60.8%. The DNA of B. canis, B. cf. microti and H. canis was found in 1 (0.8%), 38 (31.9%) and 46 (38.6%) spleen samples, respectively. In 11 samples (9.2%) co-infections with B. cf. microti and H. canis were detected and one fox harboured all three parasites (0.8%). There were no statistically significant differences between geographical region, sex or age of the host in the infection prevalence of B. cf. microti, although females (52.9%; 18/34) were significantly more infected with H. canis than males (32.9%; 28/85). The presence of vector-borne bacteria and filaroid nematodes was not detected in our study.

Conclusion

This is the first report of B. canis, B. cf. microti and H. canis parasites in foxes from Bosnia and Herzegovina and the data presented here provide a first insight into the distribution of these pathogens among the red fox population. Moreover, the relatively high prevalence of B. cf. microti and H. canis reinforces the assumption that this wild canid species might be a possible reservoir and source of infection for domestic dogs.

Keywords: Babesia cf. microti, Hepatozoon canis, Babesia canis, Red fox, Vulpes vulpes, Bosnia and Herzegovina, PCR

Background

Vector-borne diseases (VBDs) are caused by many protozoan, helminthic, bacterial and viral pathogens, which are transmitted to animals and humans by blood-sucking arthropods, such as ticks, mosquitos, fleas and phlebotomine sand flies [1]. The majority of VBDs are classified as emerging infectious diseases and anthropogenic changes, such as global warming, deforestation, globalization and pollution, may have an impact on their prevalence and distribution [1,2]. However, despite intensive clinical and epidemiological research in the recent past, especially in domestic dogs and cats, the information on the occurrence and prevalence of vector-borne pathogens in wild canids is still scarce [3-7]. Red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) are the most abundant wild canid species in Europe [8] and recently they have been recognized as a potential reservoir for blood vector-borne pathogens, such as Babesia spp. [6,9], Hepatozoon canis [4,10,11], Anaplasma phagocytophilum [12-15], Bartonella spp. [16,17], Ehrlichia canis [18] and filaroid nematodes [19-21]. They represent an excellent sentinel species and a possible source of several VBDs to domestic animals and humans, mostly due to their close proximity to urban or agricultural areas and frequent exposure to different arthropod vectors [2,6,15,22,23].

Tick-borne parasitic hematozoa of the genus Babesia (order Piroplasmida) infect erythrocytes of a wide range of domestic and wild animals [6,9,24]. In the past, it was assumed that only B. canis and B. gibsoni can cause diseases in dogs [9]. However, a piroplasm closely related to zoonotic B. microti (denominated as B. cf. microti, B. microti-like, B. annae or Theileria annae) was detected from dogs with clinical signs of hemolytic anemia, azotemia and renal failure [25-28]. Recently, B. cf. microti parasites were also molecularly confirmed in red foxes from Austria [29], Croatia [3], Germany [9], Italy [7], Poland [4], Portugal [6] and Spain [30]. Furthermore, B. canis and B. gibsoni were described in foxes based on morphological characteristics [24], and the first molecular report of B. canis was described in a single fox from Portugal [6].

Hepatozoon canis (order Eucoccidiorida) is an apicomplexan protozoan parasite infecting domestic dogs and wild canids worldwide [10,31]. The main vector of H. canis is the brown dog tick, Rhipicephalus sanguineus, and the pathogen occurrence is mostly related to the geographical distribution of the tick host [32]. Transmission to the vertebrate host typically takes place by ingestion of a tick containing mature oocysts [33], although vertical transmission of the parasite from female foxes to the progeny might also occur [34]. The infection in dogs is often subclinical, but it could be manifested as a severe life-threatening disease with fever, cachexia, lethargy and anemia [35]. In foxes, H. canis is highly prevalent and it has been recorded in Austria [29], Croatia [3], Germany [36], Hungary [31], Poland [4], Portugal [10], Romania [11], Slovakia [37] and Spain [38].

In recent years, the interest of the scientific community in vector-borne bacteria from the genera Anaplasma, Bartonella, Ehrlichia, Rickettsia and the recently described cluster ‘Candidatus Neoehrlichia’ is growing worldwide since they were recognized as important human and animal pathogens. Thus A. phagocytophilum, A. ovis, A. bovis, B. rochalimae and E. canis were molecularly identified in foxes from many European countries [12,13,15-17,23,39]. Moreover, ‘Candidatus N. mikurensis’ and Rickettsia spp. were found in humans, domestic and wild animals, and arthropods collected from foxes [13,23,40-42], but they have never been molecularly confirmed in that wild canid species itself.

Canine dirofilariosis, caused by Dirofilaria immitis and D. repens, was diagnosed in Bosnia and Herzegovina for the first time in 2009, with the prevalence of 3.1% and 1.9% in dogs, respectively [43]. These nematodes infect mainly dogs, but also wild carnivores, cats and humans [20]. Several studies have shown that foxes represent an important wild reservoir for filaroid nematodes (e.g., Dirofilaria, Acanthocheilonema) and in fact they support the circulation and transmission of microfilariae to companion animals and humans [20,21,44].

To the best of our knowledge, there is no information on vector-borne pathogens in the red fox population from Bosnia and Herzegovina. Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the presence and distribution of Babesia spp., Hepatozoon canis, Anaplasma spp., Bartonella spp., ‘Candidatus N. mikurensis’, Ehrlichia canis, Rickettsia spp. and blood filaroid nematodes in free-ranging red foxes from Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Methods

Collection of samples

The present study was conducted in Bosnia and Herzegovina, which covers 51,209 km2 and is located in the western part of the Balkan Peninsula (43° 52’ N, 18° 25’ E). A total of 119 red foxes (85 males, 34 females; 7 juveniles <1 yr., 112 adults >1 yr.) from 29 municipalities of six different regions were shot during the hunting season between October 2013 and April 2014. All animals were immediately delivered to the Department of Pathology at the Veterinary Faculty in Sarajevo and stored at 4°C for no more than 72 h. Data on sex, age and area of origin was recorded for each individual animal. During necropsy, small pieces of spleen tissue were collected, stored at −20°C and sent to the Institute of Parasitology at the University of Veterinary Medicine in Vienna, Austria for further analysis. Additionally, hearts, pulmonary arteries and lungs were dissected and examined visually for the presence of D. immitis.

DNA extraction, PCR amplification and sequencing

Total DNA was extracted from up to 20 mg of spleen tissue using the High Pure PCR Template Preparation Kit (Roche Diagnostics, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The PCR primers (Table 1) and amplification conditions for molecular detection of Babesia spp., Anaplasma spp., Bartonella spp., ‘Candidatus N. mikurensis’, E. canis and Rickettsia spp. have been published elsewhere [45-48]. PCR products were separated by electrophoresis in 2% agarose gels stained with Midori Green Advance DNA stain (Nippon Genetics Europe, Germany). All positive samples were purified and directly sequenced by a commercial company (LGC Genomics, Germany). Obtained sequences were edited using the software BioEdit (www.mbio.ncsu.edu/BioEdit/bioedit.html) and compared for similarity to sequences available in GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST).

Table 1.

Primers used for the amplification of DNA of Babesia spp., Hepatozoon spp., Anaplasma spp., Bartonella spp ., ‘ Candidatus Neoehrlichia mikurensis’, Ehrlichia canis , Rickettsia spp. and filaroid nematodes

| Specifity | Genetic marker | Sequences of primers (5’-3’) | Lenght of amplicons (bp) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apicomplexa | 18S rRNA | BTH-1 F: CCT GAG AAA CGG CTA CCA CAT CT | 561 | [45] |

| BTH-1R: TTG CGA CCA TAC TCC CCC CA | ||||

| Babesia spp. | Nested PCR: | |||

| Theileria spp. | GF2: GTC TTG TAA TTG GAA TGA TGG | |||

| GR2: CCA AAG ACT TTG ATT TCT CTC | ||||

| Hepatozoon canis | 18S rRNA | H14Hepa18SFw: GAA ATA ACA ATA CAA GGC AGT TAA AAT GCT | 620 | present study |

| H14Hepa18SRv: GTG CTG AAG GAG TCG TTT ATA AAG A | ||||

| Anaplasmataceae | 16S rRNA | EHR16SD: GGT ACC YAC AGA AGA AGT CC | 345 | [46] |

| EHR16SR: TAG CAC TCA TCG TTT ACA GC | ||||

| Bartonella spp. | 16S-23S rRNA | bartg_for: GAT GAT GAT CCC AAG CCT TC | 134 - 315 | modified [47] |

| B1623_rev: AAC CAA CTG AGC TAC AAG CC | ||||

| Rickettssia spp. | 23S/5S rRNA | ITS-F: GAT AGG TCG GGT GTG GAA G | 342 - 533 | [48] |

| ITS-R: TCG GGA TGG GAT CGT GTG | ||||

| Filaroid nematodes | COI | H14FilaCOIFw: GCC TAT TTT GAT TGG TGG TTT TGG | 724 | present study |

| H14FilaCOIRv: AGC AAT AAT CAT AGT AGC AGC ACT AA |

In order to detect apicomplexan parasites of the genera Babesia and Hepatozoon, the primer pair BTH-1 F and BTH-1R [45] was used. In those cases where the electropherograms showed superimposed signals, indicating mixed infections with different apicomplexan parasites, additional PCR reactions were performed with the specific primer pairs. The nested primers GF2 and GR2 [45] were used to detect Babesia spp., whereas new primers were designed for screening of Hepatozoon spp.: H14Hepa18SFw (5’- GAA ATA ACA ATA CAA GGC AGT TAA AAT GCT −3’) and H14Hepa18SRv (5A’- GTG CTG AAG GAG TCG TTT ATA AAG A −3’).

For PCR screening of spleens on the blood filaroid nematodes (e.g. Dirofilaria, Acanthocheilonema) another primer set, H14FilaCOIFw (5’- GCC TAT TTT GAT TGG TGG TTT TGG −3’) and H14FilaCOIRv (5’- AGC AAT AAT CAT AGT AGC AGC ACT AA −3’), was designed and used to amplify a 724 bp fragment of the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI) gene (Table 1). The PCR mixture for the newly designed primer pairs was as follows: 1 μl of extracted DNA was added to 24 μl of reaction mixture containing 5 μl of 5X Green Reaction Buffer (7.5 mM MgCl2; pH 8.5), 0.5 μl of dNTPs (10 mM), 0.125 μl of Taq polymerase (5 u/μl), 2 μl of each primer (10 pmol/μl), and made up to a final volume of 25 μl with PCR grade water. Amplifications were conducted in a Mastercycler Pro (Eppendorf, Germany) under the following conditions: 95°C for 2 min followed by 35 cycles of 95°C for 60 s, 58°C (H14Hepa18S)/53°C (H14FilaCOI) for 60 s, 72°C for 60 s. Final extension was performed at 72°C for 5 min then held at 15°C.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 20.0 statistical software. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to test for normal distribution of the data. The Kruskal-Wallis test was chosen to compare proportions of positivity by geographical region, and the Mann–Whitney-U test was used to test pathogen distribution according to sex and age. Differences were considered significant at p < 0.05.

Ethical statement

The study was conducted under the frame of Project ID: BIH-PSD-G-EC 30, Sub project ID: CRIS Number: 2010/022-259, for the improvement of animal health control through the vaccination against rabies and in accordance with the Veterinary law of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Results

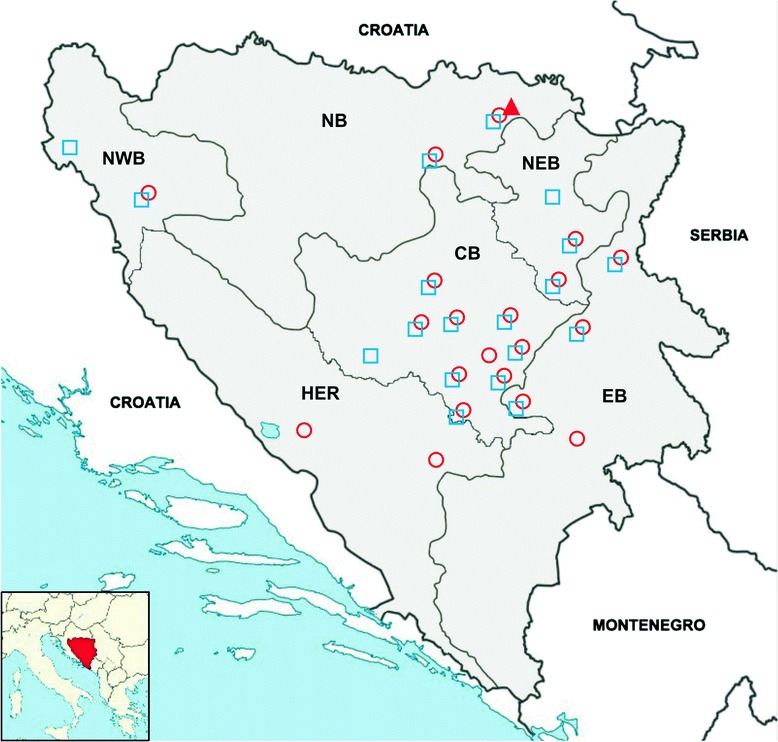

In the present study, three species of apicomplexan parasites, B. canis, B. cf. microti and H. canis, were identified in 73 red foxes by using molecular methods, with an overall prevalence of 60.8%. All infected foxes were in a good body condition and came from 23 municipalities of all six surveyed regions. The highest prevalence was detected in the region of North West Bosnia (Figure 1, Table 2). DNA of B. canis, B. cf. microti and H. canis was detected in 1 (0.8%; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.8–2.4%), 38 (31.9%; 95% CI: 23–40%) and 46 (38.6%; 95% CI: 30–48%) spleen samples, respectively. The geographical distribution of these pathogens overlap in many sampled areas (Figure 1) and co-infections with B. cf. microti and H. canis were confirmed in 11 animals (9.2%), while a single fox harboured all three pathogens (0.8%). There were no statistically significant differences in the prevalence of B. cf. microti infections between geographical regions, sex or age of the host. However, females (52.9%; 18/34) were significantly more infected with H. canis (p = 0.044) than males (32.9%; 28/85) (Table 3). Also, there was no statistically significant differences between the age and sex groups (p = 0.085).

Figure 1.

Map of Bosnia and Herzegovina showing geographical locations of

Babesia canis

,

Babesia

cf.

microti

,

Babesia

cf.

microti

and

Hepatozoon canis

and

Hepatozoon canis

infected foxes.

infected foxes.

Table 2.

The prevalence and geographical distribution of B. canis , Babesia cf. microti , and Hepatozoon canis infected foxes in Bosnia and Herzegovina

| Region | No. of examined foxes | Babesia canis | Babesia cf. microti | Hepatozoon canis | Total infection A | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| East Bosnia (EB) | 32 | 0 | 0.0 | 13 | 40.6 | 10 | 31.2 | 23 | 71.8 |

| Central Bosnia (CB) | 53 | 0 | 0.0 | 12 | 22.6 | 23 | 43.4 | 35 | 66.0 |

| North Bosnia (NB) | 9 | 1 | 11.1 | 2 | 22.2 | 3 | 33.3 | 6 | 66.6 |

| Herzegovina (HER) | 6 | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 66.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 66.6 |

| North East Bosnia (NEB) | 15 | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 40.0 | 7 | 46.6 | 13 | 86.6 |

| North West Bosnia (NWB) | 4 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 25.0 | 3 | 75.0 | 4 | 100 |

| Total | 119 | 1 | 0.8 | 38 | 31.9 | 46 | 38.3 | 85 | 70.8 |

ARefers to total number of infections, not total number of infected animals.

Table 3.

Number of foxes infected with Babesia canis , Babesia cf. microti and Hepatozoon canis in Bosnia and Herzegovina categorized by sex and age

| Region | Babesia canis | Babesia cf. microti | Hepatozoon canis | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | >1 yr. | <1 yr. | Male | Female | >1 yr. | <1 yr. | Male | Female | >1 yr. | <1 yr. | |

| East Bosnia (EB) | - | - | - | - | 6 | 7 | 13 | - | 5 | 5 | 10 | - |

| Central Bosnia (CB) | - | - | - | - | 8 | 4 | 10 | 2 | 14 | 9 | 22 | 1 |

| North Bosnia (NB) | 1 | - | 1 | - | 2 | - | 2 | - | 2 | 1 | 3 | - |

| Herzegovina (HER) | - | - | - | - | 4 | - | 2 | 2 | - | - | - | - |

| North East Bosnia (NEB) | - | - | - | - | 6 | - | 6 | - | 6 | 1 | 7 | - |

| North West Bosnia (NWB) | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | 1 | 2 | 3 | - |

| Positive/Total sampled | 1/85 | 0/34 | 1/112 | 0/7 | 27/85 | 11/34 | 34/112 | 4/7 | 28/85 | 18*/34 | 45/112 | 1/7 |

*(p < 0.05).

A total of 90 PCR-positive samples were sequenced. Of these, 38 samples showed 99–100% similarity to 18S sequences attributed to Theileria annae [GenBank accession no. HM212628.1] found in foxes from Croatia [3] and Babesia sp. ‘Spanish dog’ [GenBank accession no. AY457974.1] isolated from dogs in Spain [27]. A sequence of one sample showed 100% identity with sequences of B. canis canis [GenBank accession no. FJ209024.1] reported from dogs in Croatia [49].

PCRs performed with the Apicomplexa-specific 18S primers BTH-1 F and BTH-1R detected H. canis in 41 (89.1%) out of a total of 46 positive samples confirmed by Hepatozoon-specific PCR and sequencing. Moreover, five PCR products were positive on gel, but the occurrence of pathogens could not be confirmed by sequencing and all were noted as false positive.

Out of 46 18S sequences of H. canis, 38 were 100% identical to a sequence from a Spanish fox [GenBank accession no. AY150067.2] [38], while all others showed up to 99% similarity to sequences from foxes and dogs from all over the world (East Asia, India, Europe, North Africa and South America). All sequences are deposited in GenBank and are available under accession numbers KP216410–KP216494. The presence of Anaplasma spp., Bartonella spp., ‘Candidatus N. mikurensis’, E. canis, Rickettsia spp. and blood filaroid nematodes was not detected in our samples.

Discussion

This study for the first time reports the occurrence of B. canis, B. cf. microti and H. canis parasites in red foxes from Bosnia and Herzegovina. The piroplasm B. cf. microti was molecularly confirmed in 38/119 (31.9%) animals from all six surveyed regions, with the highest prevalence (66.6%) detected in Herzegovina. The observed prevalence of infection was higher than that previously found in Croatia (5%; [3]), Italy (0.98%; [7]), Poland (0.7%; [4]) and Spain (14%; [30]). Higher prevalence was reported in foxes from Austria (50%; [29]), Germany (46.4%; [9]) and Portugal (69.2%; [6]). Differences between prevalence levels reported among studies may occur due to different tissues sampled or assay used, but also due to geographical distributions of the tick vectors [6]. Ixodes hexagonus was suspected to be the main vector responsible for transmission of B. cf. microti [50], but recently it was molecularly detected in I. ricinus, I. canisuga and R. sanguineus as well [9,51]. However, the vector competence of these tick species is not confirmed yet and the presence of the piroplasm DNA in the ticks may represent blood engorged from an infected animal host [6,9]. The fact that infected foxes were discovered in all studied areas, and that the occurrence of I. hexagonus was observed only in the western part of Bosnia [52], supports the hypothesis about the existence of another vector species other than I. hexagonus. Moreover, B. canis was detected in one fox (0.8%) originating from North Bosnia. This finding was completely unexpected, since B. canis has been molecularly confirmed only in a single fox from Portugal so far [6], suggesting that foxes are not suitable hosts for these canine blood parasites; they were probably transmitted accidentally by ticks which fed on infected dogs.

In this study, H. canis was the most frequently detected parasite, with a prevalence of 38.6% (46/119). Infected foxes were present in almost all sampled regions, except in the region of Herzegovina. This finding is intriguing because R. sanguineus is present in Herzegovina [52] and very small sample size obtained from this area (n = 6) may be the reason for the absence of H. canis. However, H. canis was also observed in areas lacking R. sanguineus [29,37,53]. Among studies using DNA from spleen or blood samples for PCRs, the prevalence of infections with H. canis in red foxes ranged from 8% in Hungary to 75.6% in Portugal [3,4,10,11,29-31,36,37]. The fact that there was no significant difference in the prevalence between the age groups of the host in our study might indicate that foxes were infected at a young age by vertical intrauterine transmission or by vectors as already suggested [10]. Since we had only 7 juveniles in our dataset, we cannot clearly confirm or reject the hypothesis of intrauterine transmission. But even though the age and sex groups were not statistically different, the samples represent not confounding data. Interestingly, the infection rate of females was significantly higher, which suggests that females have an important role in the maintaining and spreading of infection. It has been suggested that there is a difference in parasite burden between males and females and between parasitic taxa due to differences such as hormone level or innate immune response [54,55]. However, for H. canis the differences of the parasite load between females and males has not been explained, yet.

In dogs, infections with B. cf. microti and H. canis usually cause disorders that affect spleen, lymph nodes, bone marrow and kidneys, resulting in anemia, azotemia, fever, lethargy, cachexia or even death [25-28,35]. During necropsies it was noticed that all examined foxes, except for seven with sarcoptic mange (5.8%), were in a good body condition. This might indicate a low pathogenicity of these pathogens in this wild canid species, as already suggested [9]. All sequences obtained from red foxes in this study had a high homology to the ones previously reported from different canid species and different locations, which indicates a wide circulation of these pathogens without obvious geographical and host-related division patterns [31].

Although several studies suggest that red foxes can serve as reservoir hosts for various vector-borne bacteria [12-18], their presence could not be confirmed in this study. Regarding filaroid nematodes, D. immitis and D. repens were reported in dogs from Bosnia and Herzegovina [43], confirming that this area is suitable for the transmission of these parasites, but they also were not detected in foxes by PCR or necropsy. Since the present data does not allow the occurrence of bacteria and filaroid nematodes in foxes from Bosnia and Herzegovina to be completely excluded, monitoring and further analysis are necessary to elucidate the potential role of red foxes in their epidemiology.

Conclusion

The relatively high prevalence and widespread distribution of B. cf. microti and H. canis among the red fox population of Bosnia and Herzegovina support the existence of a sylvatic cycle and reinforce the assumption that foxes might be a possible reservoir and vector of infection to dogs and other canids. Moreover, data presented in this study should improve awareness among veterinarians and alert them to include infections caused by these two pathogens in the differential diagnosis of canine babesiosis.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Samir Bogunić (Department of Pathology, Veterinary Faculty in Sarajevo) for his technical support and assistance in sample collection, as well as all hunting societies that participated in this study. The work of Adnan Hodžić, Hans-Peter Fuehrer and Georg G. Duscher was conducted under the frame of EurNegVec COST Action TD1303.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

AH and GGD conceived and designed the study; AH performed PCRs and drafted the manuscript; AA collected the samples; HPF performed sequence analyses; JH designed the primers and performed sequence analyses; WWP provided assistance in the lab and performed PCRs; GGD performed the statistical analysis and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Adnan Hodžić, Email: adnan.hodzic@vetmeduni.ac.at.

Amer Alić, Email: amer.alic@vfs.unsa.ba.

Hans-Peter Fuehrer, Email: hans-peter.fuehrer@vetmeduni.ac.at.

Josef Harl, Email: josef.harl@vetmeduni.ac.at.

Walpurga Wille-Piazzai, Email: walpurga.wille-piazzai@vetmeduni.ac.at.

Georg Gerhard Duscher, Email: georg.duscher@vetmeduni.ac.at.

References

- 1.Otranto D, Dantas-Torres F. Canine and feline vector-borne diseases in Italy: current situation and perspectives. Parasit Vectors. 2010;3:2. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-3-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aguirre AA. Wild canids as sentinels of ecological health: a conservation medicine perspective. Parasit Vectors. 2009;2(Suppl 1):S7. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-2-S1-S7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deždek D, Vojta L, Ćurković S, Lipej Z, Mihaljević Z, Cvetnić Z, et al. Molecular detection of Theileria annae and Hepatozoon canis in foxes (Vulpes vulpes) in Croatia. Vet Parasitol. 2010;172:333–6. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karbowiak G, Majláthová V, Hapunik J, Petko B, Wita I. Apicomplexan parasites of red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) in northeastern Poland. Acta Parasitol. 2010;55:210–4. doi: 10.2478/s11686-010-0030-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hamel D, Silaghi C, Lescai D, Pfister K. Epidemiological aspects on vector-borne infections in stray and pet dogs from Romania and Hungary with focus on Babesia spp. Parasitol Res. 2012;110:1537–45. doi: 10.1007/s00436-011-2659-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cardoso L, Cortes HCE, Reis A, Rodrigues P, Simões M, Lopes AP, et al. Prevalence of Babesia microti-like infection in red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) from Portugal. Vet Parasitol. 2013;196:90–5. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2012.12.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zanet S, Trisciuoglio A, Bottero E, de Mera IGF, Gortazar C, Carpignano MG, et al. Piroplasmosis in wildlife: Babesia and Theileria affecting free-ranging ungulates and carnivores in the Italian Alps. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:70. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sobrino R, Dubey JP, Pabón M, Linarez N, Kwok OC, Millán J, et al. Neospora caninum antibodies in wild carnivores from Spain. Vet Parasitol. 2008;155:190–7. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Najm NA, Meyer-Kayser E, Hoffmann L, Herb I, Fensterer V, Pfister K, et al. A molecular survey of Babesia spp. and Theileria spp. in red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) and their ticks from Thuringia, Germany. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2014;5:386–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2014.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cardoso L, Cortes HCE, Eyal O, Reis A, Lopes AP, Vila-Viçosa MJ, et al. Molecular and histopathological detection of Hepatozoon canis in red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) from Portugal. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:113. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ilie M, Imre M, Imre K, Hotea I, Morariu S, Sorescu D, et al. Occurrence of Hepatozoon spp. in red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) in Romania. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7(Suppl 1):O33. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-S1-O33. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karbowiak G, Víchová B, Majláthová V, Hapunik J, Petko B. Anaplasma phagocytophilum infection of red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) Ann Agric Environ Med. 2009;16:71–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beck R, Čubrić Čurik V, Ivana R, Nikica Š, Anja V. Identification of “Candidatus Neoehrlichia mikurensis” and Anaplasma species in wildlife from Croatia. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7(Suppl 1):O28. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-S1-O28. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jahfari S, Coipan EC, Fonville M, van Leeuwen AD, Hengeveld P, Heylen D, et al. Circulation of four Anaplasma phagocytophilum ecotypes in Europe. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:365. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Härtwig V, von Loewenich FD, Schulze C, Straubinger RK, Daugschies A, Dyachenko V. Detection of Anaplasma phagocytophilum in red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) and raccoon dogs (Nyctereutes procyonoides) from Brandenburg, Germany. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2014;5:277–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henn JB, Chomel BB, Boulouis HJ, Kasten RW, Murray WJ, Bar-Gal GK, et al. Bartonella rochalimae in raccoons, coyotes, and red foxes. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1984–7. doi: 10.3201/eid1512.081692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gerrikagoitia X, Gil H, García-Esteban C, Anda P, Juste RA, Barral M. Presence of Bartonella species in wild carnivores of northern Spain. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:885–8. doi: 10.1128/AEM.05938-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pusterla N, Deplazes P, Braun U, Lutz H. Serological evidence of infection with Ehrlichia spp. in red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) in Switzerland. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1168–70. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.4.1168-1169.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gortázar G, Villafuerte R, Lucientes J, Fernández de Luco D. Habitat related differences in helminth parasites of red foxes in Ebro valley. Vet Parasitol. 1998;80:75–81. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4017(98)00192-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Magi M, Calderini P, Gabrielli S, Dell’Omodarme M, Macchioni F, Prati MC, et al. Vulpes vulpes: a possible wild reservoir for zoonotic filariae. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2008;8:249–52. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2007.0207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tolnai Z, Széll Z, Sproch Á, Szeredi L, Sréter T. Dirofilaria immitis: An emerging parasite in dogs, red foxes and golden jackals in Hungary. Vet Parasitol. 2014;203:339–42. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2014.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hodžić A, Latrofa MS, Annoscia G, Alić A, Beck R, Lia RP, et al. The spread of zoonotic Thelazia callipaeda in the Balkan area. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:352. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Torina A, Blanda V, Antoci F, Scimeca S, D’Agostino R, Scariano E, et al. A Molecular survey of Anaplasma spp., Rickettsia spp., Ehrlichia canis and Babesia microti in foxes and fleas from Sicily. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2013;60(Suppl 2):125–30. doi: 10.1111/tbed.12137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Penzhorn BL. Babesiosis of wild carnivores and ungulates. Vet Parasitol. 2006;138:11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zahler M, Rinder H, Schein E, Gothe R. Detection of a new pathogenic Babesia microti -like species in dogs. Vet Parasitol. 2000;89:241–8. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4017(00)00202-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Camacho AT, Pallas E, Gestal JJ, Guitián FJ, Olmeda AS, Goethert HK, et al. Infection of dogs in north-west Spain with Babesia microti-like agent. Vet Rec. 2001;149:552–5. doi: 10.1136/vr.149.18.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Camacho AT, Guitian EJ, Pallas E, Gestal JJ, Olmeda AS, Goethert HK, et al. Azotemia and mortality among Babesia microti-like infected dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2004;18:141–6. doi: 10.1892/0891-6640(2004)18<141:aamabm>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Camacho AT, Guitian FJ, Pallas E, Gestal JJ, Olmeda S, Goethert H, et al. Serum protein response and renal failure in canine Babesia annae infection. Vet Res. 2005;36:713–22. doi: 10.1051/vetres:2005026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Duscher GG, Fuehrer HP, Kübber-Heiss A. Fox on the run - molecular surveillance of fox blood and tissue for the occurrence of tick-borne pathogens in Austria. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:521. doi: 10.1186/s13071-014-0521-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gimenez C, Casado N, Criado-Fornelio A, de Miguel FA, Dominguez-Peñafiel G. A molecular survey of Piroplasmida and Hepatozoon isolated from domestic and wild animals in Burgos (northern Spain) Vet Parasitol. 2009;162:147–50. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2009.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Farkas R, Solymosi N, Takács N, Hornyák Á, Hornok S, Nachum-Biala Y, et al. First molecular evidence of Hepatozoon canis infection in red foxes and golden jackals from Hungary. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:303. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baneth G. Perspectives on canine and feline hepatozoonosis. Vet Parasitol. 2011;181:3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baneth G, Samish M, Shkap V. Life cycle of Hepatozoon canis (Apicomplexa: Adeleorina: Hepatozoidae) in the tick Rhipicephalus sanguineus and domestic dog (Canis familiaris) J Parasitol. 2007;93:283–99. doi: 10.1645/GE-494R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murata T, Inoue M, Tateyama S, Taura Y, Nakama S. Vertical transmission of Hepatozoon canis in dogs. J Vet Med Sci. 1993;55:867–8. doi: 10.1292/jvms.55.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baneth G, Weigler B. Retrospective Case–control Study of Hepatozoonosis in Dogs in Israel. J Vet Intern Med. 1997;11:365–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.1997.tb00482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Najm NA, Meyer-Kayser E, Hoffmann L, Pfister K, Silaghi C. Hepatozoon canis in German red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) and their ticks: molecular characterization and the phylogenetic relationship to other Hepatozoon spp. Parasitol Res. 2014;113:2697–85. doi: 10.1007/s00436-014-3923-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Majláthová V, Hurníková Z, Majláth I, Petko B. Hepatozoon canis infection in Slovakia: imported or autochthonous? Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2007;7:199–202. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2006.0598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Criado-Fornelio AA, Ruas JL, Casado N, Farias NA, Soares MP, Müller G, et al. New molecular data on mammalian Hepatozoon species (Apicomplexa: Adeleorina) from Brazil and Spain. J Parasitol. 2006;92:93–9. doi: 10.1645/GE-464R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ebani VV, Verin R, Fratini F, Poli A, Cerri D. Molecular survey of Anaplasma phagocytophilum and Ehrlichia canis in red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) from central Italy. J Wildl Dis. 2011;47:699–703. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-47.3.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Márquez FJ, Millán J, Rodríguez-Liébana JJ, García-Egea I, Muniain MA. Detection and identification of Bartonella sp. in fleas from carnivorous mammals in Andalusia, Spain. Med Vet Entomol. 2009;23:393–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.2009.00830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Diniz PPVP, Schulz BS, Hartmann K, Breitschwerdt EB. “Candidatus Neoehrlichia mikurensis” infection in a dog from Germany. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:2059–62. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02327-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marié JL, Davoust B, Socolovschia C, Mediannikova O, Roqueplo C, Beaucournu JC, et al. Rickettsiae in arthropods collected from red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) in France. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;35:59–62. doi: 10.1016/j.cimid.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Otašević S, Tasić A, Gabrielli S, Trenkić Božinović M, Cancrini G. Canine and human Dirofilaria infections: What is new in the Balkan Peninsula. In Proceedings of the IV European Dirofilaria and Angiostrongylus Days. Budapest, Hungary; 2014

- 44.Penezić A, Selaković S, Pavlović I, Ćirović D. First findings and prevalence of adult heartworms (Dirofilaria immitis) in wild carnivores from Serbia. Parasitol Res. 2014;113:3281–5. doi: 10.1007/s00436-014-3991-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zintl A, Finnerty EJ, Murphy TM, de Waal T, Gray JS. Babesias of red deer (Cervus elaphus) in Ireland. Vet Res. 2011;42:7. doi: 10.1186/1297-9716-42-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brown GK, Martin AR, Roberts TK, Aitken RJ. Detection of of Ehrlichia platys in dogs in Australia. Aust Vet J. 2001;79:554–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.2001.tb10747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jensen WA, Fall MZ, Rooney J, Kordick DL, Breitschwerdt EB. Rapid Identification and Differentiation of Bartonella Species Using a Single-Step PCR Assay. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:1717–22. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.5.1717-1722.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vitorino L, Zé-zé L, Sousa A, Bacellar F, Tenreiro R. rRNA Intergenic Spacer Regions for Phylogenetic Analysis of Rickettsia Species. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2003;990:726–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Beck R, Vojta L, Mrljak V, Marinculić A, Beck A, Živičnjak T, et al. Diversity of Babesia and Theileria species in symptomatic and asymptomatic dogs in Croatia. Int J Parasitol. 2009;39:843–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Camacho AT, Pallas E, Gestal JJ, Guitián FJ, Olmeda AS, Telford SR, III, et al. Ixodes hexagonus is the main candidate as vector of Theileria annae in northwest Spain. Vet Parasitol. 2003;112:157–63. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4017(02)00417-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Iori A, Gabrielli S, Calderini P, Moretti A, Pietrobelli M, Tampieri MP, et al. Tick reservoirs for piroplasms in central and northern Italy. Vet Parasitol. 2010;170:291–6. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Omeragić J. Ixodid ticks in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Exp Appl Acarol. 2011;53:301–9. doi: 10.1007/s10493-010-9402-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hornok S, Tánczos B, de Fernández de Mera IG, de la Fuente J, Hofmann-Lehmann R, Farkas R. High prevalence of Hepatozoon-infection among shepherd dogs in a region considered to be free of Rhipicephalus sanguineus. Vet Parasitol. 2013;196:189–93. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2013.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Klein SL. Hormonal and immunological mechanisms mediating sex differences in parasite infection. Parasite Immunol. 2004;26:247–64. doi: 10.1111/j.0141-9838.2004.00710.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Krasnov BR, Matthee S. Spatial variation in gender-biased parasitism: host-related, parasite-related and environment-related effects. Parasitology. 2010;137:1527–36. doi: 10.1017/S0031182010000454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]