Abstract

Background

Optic neuritis is an inflammatory disease of the optic nerve. It occurs more commonly in women than in men. Usually presenting with an abrupt loss of vision, recovery of vision is almost never complete. Closely linked in pathogenesis to multiple sclerosis, it may be the initial manifestation for this condition. In certain patients, no underlying cause can be found.

Objectives

To assess the effects of corticosteroids on visual recovery of patients with acute optic neuritis.

Search strategy

We searched the Cochrane Controlled Trials Register (CENTRAL) (which contains the Cochrane Eyes and Vision Group Trials Register) (issue 4, 2005), MEDLINE (1966 to December 2005), EMBASE (1980 to January 2006), NNR (issue 4, 2006), LILACS and reference lists of identified trial reports.

Selection criteria

We included randomized trials that evaluated corticosteroids, in any form, dose or route of administration, in people with acute optic neuritis.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently extracted the data on methodological quality and outcomes for analysis.

Main results

We included five randomized trials which included a total of 729 participants. Two trials evaluated low dose oral corticosteroids and two trials evaluated a higher dose of intravenous corticosteroids. One three-arm trial evaluated low-dose oral corticosteroids and high-dose intravenous corticosteroids against placebo. Trials evaluating oral corticosteroids compared varying doses of corticosteroids with placebo. Hence, we did not conduct a meta-analysis of such trials. In a meta-analysis of trials evaluating corticosteroids with total dose greater than 3000 mg administered intravenously, the relative risk of normal visual acuity with intravenous corticosteroids compared with placebo was 1.06 (95% CI 0.89 to 1.27) at six months and 1.06 (95% CI 0.92 to 1.22) at one year. The risk ratio of normal contrast sensitivity for the same comparison was 1.10 (95% CI 0.92 to 1.32) at six months follow up. We did not conduct a meta-analysis for this outcome at one year follow up since there was substantial statistical heterogeneity. The risk ratio of normal visual field for this comparison was 1.08 (95% CI 0.96 to 1.22) at six months and 1.02 (95% CI 0.86 to 1.20) at one year. Quality of life was assessed and reported in one trial.

Authors' conclusions

There is no conclusive evidence of benefit in terms of recovery to normal visual acuity, visual field or contrast sensitivity with either intravenous or oral corticosteroids at the doses evaluated in trials included in this review.

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH): Adrenal Cortex Hormones [*therapeutic use], Contrast Sensitivity [drug effects], Optic Neuritis [*drug therapy], Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Visual Acuity [drug effects]

MeSH check words: Humans

Background

Description of the condition

Optic neuritis is an inflammatory disease of the optic nerve. It is second only to glaucoma as the most common acquired optic nerve disorder in persons under 50 years. The majority of patients with optic neuritis are between the ages of 20 and 50 years, with a mean age around 30 to 35 years. In population-based studies the annual incidence of optic neuritis in the US has been estimated to be between 1 and 5/100,000 (Beck 1998). Koch-Henriksen and Hyllested reported an annual incidence of 4 to 5/100,000 for new onset optic neuritis cases in Denmark in 1948 to 1964 (Koch-Henriksen 1988). In Olmstead County, Minnesota, USA the prevalence rate of optic neuritis was estimated as 115/100,000 (Rodriguez 1995). Women are more likely to be affected than men. Optic neuritis is closely linked to multiple sclerosis (MS) and in most cases has a similar pathogenesis. It may be the first manifestation of multiple sclerosis or occur later in its course (Ebers 1985).

The presenting symptom is usually abrupt visual loss in one eye over several hours or days, accompanied by mild pain. Symptoms can also occur in both eyes either simultaneously or sequentially. A clinical diagnosis of optic neuritis may be made based on the following: age between 18 and 45 years, sudden visual loss with progression for less than one week, pain on eye movement, no inflammation in the vitreous or anterior chamber, and improvement in vision that begins within three to four weeks. The prognosis for visual recovery after acute optic neuritis is generally good. However, most patients have some lasting visual impairment. Even when a patient's visual acuity does return to normal, abnormalities frequently remain in other measures such as contrast sensitivity, color vision, and visual field (Fleishman 1987; Sanders 1986).

Description of the intervention

Although corticosteroids have been used since the early 1950s to treat acute optic neuritis because of their anti-inflammatory effects, studies to demonstrate their effectiveness have not been satisfactory. Some experts advocated treatment with oral prednisone while others recommended no or other treatment. In the 1980s, anecdotal reports suggested that high-dose intravenous corticosteroids might be effective (Spoor 1988). In 1992, the National Eye Institute of the US National Institutes of Health funded a randomized controlled trial to test the efficacy of corticosteroids in the treatment of optic neuritis (ONTT 1992-2004). Based on results of this trial the current guidelines in the United States suggest either administration of high-dose intravenous methylprednisolone to hasten recovery of vision or no treatment. There are no other treatments with regard to recovery of vision in acute optic neuritis. Beta-interferons have been recently assessed for their value in reducing the progression rate to multiple sclerosis but that is outside of the scope of this review (Jacobs 2000).

Rationale for a systematic review

Prior to the Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial (ONTT) (ONTT 1992-2004) well-established guidelines for treating optic neuritis did not exist. Brusaferri and Candelise (Brusaferri 2000) published a meta-analysis of steroids for multiple sclerosis and optic neuritis with inclusion criteria for participants and treatment type different from those specified for this review. We systematically reviewed the evidence for the use of corticosteroid therapy in any form or dosage with the intention to treat or reduce the symptoms in patients with acute optic neuritis, compared with placebo or no treatment.

Objectives

The objective of this review was to assess the effects of corticosteroids on visual recovery of patients with acute optic neuritis.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

This review included only randomized controlled trials.

Types of participants

We included trials in which the participants had acute optic neuritis. There were no age limitations.

Types of interventions

We included trials in which the administration of corticosteroid therapy in any form or dosage with the intention to treat or reduce the symptoms of acute optic neuritis were compared to placebo, no treatment or other treatment. We did not limit inclusion of trials in this review based on the duration of treatment.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

The primary outcomes for this review were visual outcomes measured as

Proportion of people with normal visual acuity at six months or more;

Proportion of people with normal contrast sensitivity at six months or more;

Proportion of people with normal visual field at six months or more.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes were immediate response (rate of recovery) measured as

Proportion of people with normal visual acuity at one month;

Proportion of people with normal contrast sensitivity at one month;

Proportion of people with normal visual field at one month. Adverse outcomes related to treatment with corticosteroids were summarized. When available, we planned to summarize data on quality of life.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (which contains the Cochrane Eyes and Vision Group Trials Register) in The Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, EMBASE and Latin American and Caribbean Literature on Health Sciences (LILACS). The databases were last searched on 9 January 2006.

See: Appendices for details of search strategies for each database.

Searching other resources

We searched the reference lists of identified trial reports to find additional trials. The Science Citation Index was used to find studies that have cited the identified trials. We contacted investigators to identify additional published and unpublished studies. We did not conduct manual searches of conference proceeding abstracts specifically for this review.

There were no language restrictions in the searches for trials.

Data collection and analysis

Assessment of search results

Two review authors independently assessed the titles and abstracts of all reports identified by the electronic and other searches. We retrieved the full articles of potentially or definitely relevant studies and reviewed these according to the definitions in the ‘Criteria for considering studies for this review’. For non-English trials identified as potentially relevant, the methods and results sections were translated and assessed for inclusion. We categorized the reports as exclude, or unclear, or include. We excluded trial reports identified by both review authors as ‘exclude’ and documented the reasons for exclusion for trials excluded after full-text review in the ‘Characteristics of excluded studies’ table. A third review author resolved any disagreements.

Assessment of methodological quality

Papers identified to be eligible for inclusion were assessed for methodological quality and sources of systematic bias according to methods set out in Section 6 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2005b) by two review authors. Review authors were unmasked to the trialists, in-stitutions and trial results during the assessment. The following parameters were considered: method of allocation and allocation concealment (selection bias), masking of outcome assessment (detection bias), and completeness of follow up (attrition bias). All trials were assessed on intention to treat analysis. Two review authors independently graded each of the parameters as: A (adequate); B (unclear); or C (inadequate). A third review author resolved any disagreements.

As stated in our protocol we excluded trials graded C on randomization or allocation concealment. We contacted the investigators of trials categorized as B for further information. If the investigators did not respond or if we were not able to communicate with them, we assigned a grade to the trial based on the information available.

Assessment of study characteristics

In addition to the parameters described above, we extracted data on the study characteristics, such as details of participants, the interventions, the outcomes, cost and quality of life data if available, and other relevant information.

Data collection and synthesis

Two review authors independently extracted the data for the primary and secondary outcomes onto paper data collection forms and one review author double-entered the data into RevMan 4.2. After data were extracted and entered into RevMan, a chi-square test for statistical heterogeneity was performed and the I-square value was evaluated. If no statistical heterogeneity was detected and there was no clinical heterogeneity within the trials we summarized the results of the studies using risk ratios with 95% confidence intervals. We used a random-effects model or if there was no substantial heterogeneity (I-square > 50%). We used a fixed-effect model if there was no heterogeneity or there were fewer than three trials in the comparison.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses to determine the impact of exclusion of lower quality methodological studies, exclusion of unpublished studies, and exclusion of industry-funded studies were not conducted because there were not enough studies.

Results

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies.

The electronic searches found 430 titles and abstracts. We screened the titles and abstracts according to the criteria outlined above and identified 51 potential trial reports. We obtained the full copies of these for further assessment. Twenty-nine were reports on different aspects of the included trials. One was a duplicate citation. We excluded 18 studies after a detailed review of the full text. Reasons for exclusion are listed in the ‘Characteristics of excluded studies’. Three studies are awaiting further assessment.

Included studies

We included five trials which randomized a total of 729 participants. Detailed characteristics of the included studies are presented in the ‘Characteristics of Included Studies’ table. A brief comment on variability between different trial characteristics is presented here.

Types of participants

Three trials (Kapoor 1998; ONTT 1992-2004; Tubingen 1993) restricted inclusion to only those participants with no history of prior attacks of optic neuritis in the affected eye. Kapoor 1998 included only patients with confirmed multiple sclerosis, while the remaining trials included people with optic neuritis of unknown and demyelinating etiologies. Most trials included participants with a short duration of onset of visual symptoms. Participants had visual symptoms for less than two weeks in ONMRG 1999, less than eight days in ONTT 1992-2004, less than four weeks in Sellebjerg 1999 and less than three weeks in Tubingen 1993. Kapoor 1998 and ONTT 1992-2004 specifically reported exclusion of participants with past history of optic neuritis in the same eye. Participants with a history of treatment with corticosteroids were excluded in ONMRG 1999, ONTT 1992-2004, Sellebjerg 1999 and Tubingen 1993.

Types of interventions

The trials varied in the interventions compared, both in route of administration and dose administered. Intravenous methylprednisone was compared with placebo in Kapoor 1998. Intravenous methylprednisone followed by tapering with oral prednisone was compared with placebo in ONTT 1992-2004 and ONMRG 1999. One of the three treatment arms in ONTT 1992-2004 administered oral prednisone while Sellebjerg 1999 and Tubingen 1993 compared oral methylprednisolone with placebo. Description of doses of corticosteroids evaluated in each of the trials in the text of the review refers to the total dose administered over the course of the entire regimens. The regimens in the individual trials are described in the table of included studies in greater detail.

The total dose of corticosteroid administered to patients in the treatment arms in the included trials varied from 1035 mg in Tubingen 1993 to more than 3770 mg in the intravenous corticosteroid arm of the ONTT 1992-2004.

The control intervention was intravenous mecobalamin (B12) in ONMRG 1999 and oral thiamine (B1) in Tubingen 1993. Because of systemic treatment administration, randomization was by patient.

Types of outcomes

All trials examined and reported visual acuity as an outcome. Sellebjerg 1999 did not assess visual field in a systematic manner (personal communication with Dr. Sellebjerg and contrast sensitivity was not reported in Tubingen 1993. There was also variability in the method employed to assess different outcomes as noted in the ‘Characteristics of Included Studies’ table.

Normal visual acuity was defined as 20/20 in all studies. Normal visual field was defined as greater than -3.00 db in all included trials. Measurement of contrast sensitivity was variable. Normal contrast sensitivity was defined as greater than 1.65 log units in ONTT 1992-2004 and ONMRG 1999. Sellebjerg 1999 measured contrast sensitivity using Arden gratings and defined normal as less than or equal to 80 points. Kapoor 1998 considered normal contrast sensitivity to be greater than 1.35 db.

Risk of bias in included studies

The methodological quality of included studies was assessed on the following parameters: (1) the method of allocation; (2) allocation concealment; (3) masking of outcome assessment; (4) completeness of follow up; and (5) intention to treat analysis. The results of the quality assessment are presented in detail in the ‘Characteristics of Included Studies’ table.

All trials were randomized, but only three of the trials reported the method of randomization (ONMRG 1999; ONTT 1992-2004; Tubingen 1993). Of the five trials, two reported the method of allocation concealment in the published manuscript (ONTT 1992-2004; Sellebjerg 1999) and three trialists were contacted for more information. Data on allocation concealment were obtained for Kapoor 1998, ONMRG 1999 and Tubingen 1993 and assessed to meet the quality parameter.

Outcome assessment in all included trials was conducted in a masked fashion except for one of the three arms in the ONTT (ONTT 1992-2004); the outcome assessors for the intravenous corticosteroid group were not masked, though they were for the placebo and oral steroid groups.

Completeness of follow up was reported by all trials and at 12 months varied from0% loss to follow up (ONMRG 1999) to 19% (Tubingen 1993). Only the ONTT study (ONTT 1992-2004) reported an intention-to-treat analysis for the primary outcomes.

Effects of interventions

After examining the included studies we determined that analysis of all included trials in one meta-analysis was not clinically meaningful because the corticosteroids were administered in different doses and routes, constituting clinical heterogeneity.

Studies evaluating oral administration of corticosteroids for optic neuritis were clinically heterogeneous since widely varied doses were evaluated in each trial. The total dose of oral corticosteroids administered was 355 mg, 3676 mg, and 1200 mg in Tubingen 1993, Sellebjerg 1999 and oral arm of ONTT 1992-2004, respectively.

For the purposes of this review, we conducted meta-analyses of trials with a total intravenous dose of 3000 mg corticosteroids or more including the IV arm of ONTT 1992-2004 (3770 mg), ONMRG 1999 (> 3000 mg) and Kapoor 1998 (3000 mg). These trials varied in the outcomes reported at different time points and thus data from all three trials were not available for all analyses.

Intravenous corticosteroids (total dose ≥ 3000 mg) versus placebo

Visual acuity

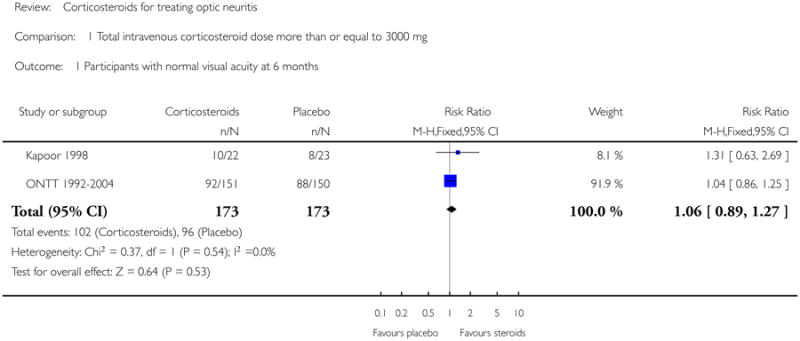

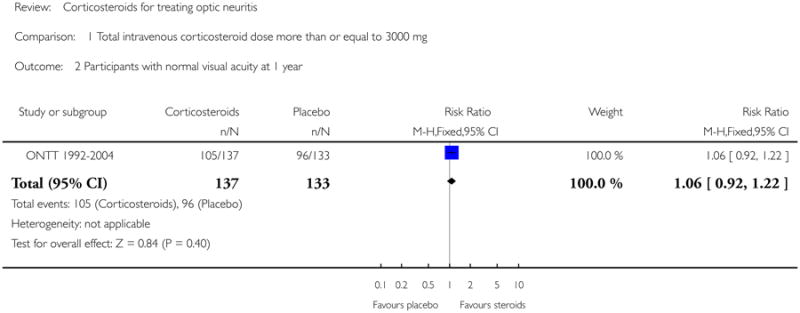

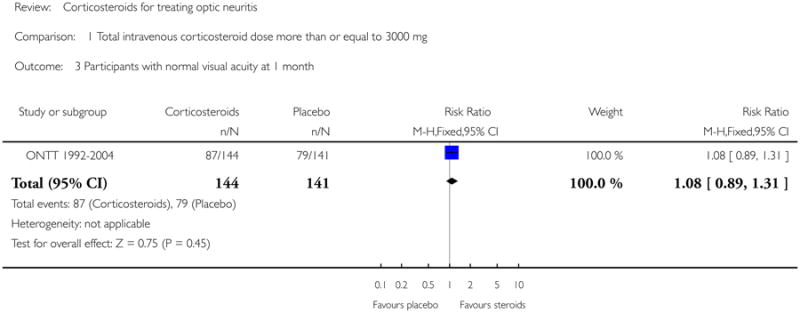

In a meta-analysis of trials evaluating corticosteroids of dose greater than 3000 mg administered intravenously, the risk ratio of normal visual acuity at six months follow up was 1.06 (95% CI 0.89 to 1.27) (see Figure 1). The meta-analysis for this outcome included Kapoor 1998 and ONTT 1992-2004. There was no substantial statistical heterogeneity at any of the time-points for this outcome. The risk ratio of normal visual acuity was 1.06 (95% CI 0.92 to 1.22) at one year (see Figure 2), 1.08 (95% CI 0.89 to 1.31) at one month (see Figure 3), and included data from only ONTT (ONTT 1992-2004).

Contrast sensitivity

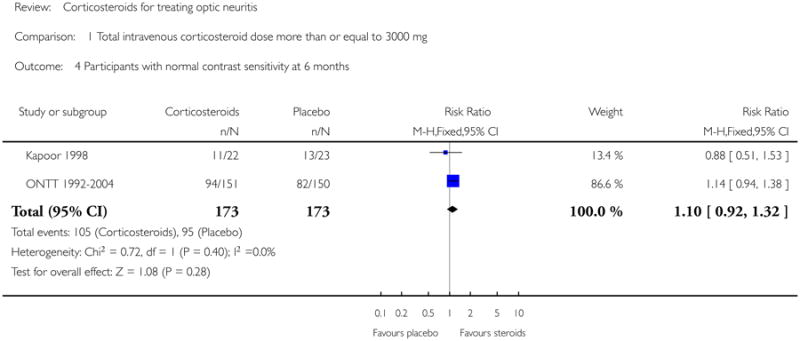

In a meta-analysis of Kapoor 1998 and ONTT 1992-2004, the risk ratio of normal contrast sensitivity was 1.10 (95% CI 0.92 to 1.32) at six months follow up (see Figure 4). There was no substantial statistical heterogeneity. At one year, data on normal contrast sensitivity was available only from ONMRG 1999 and ONTT 1992-2004.

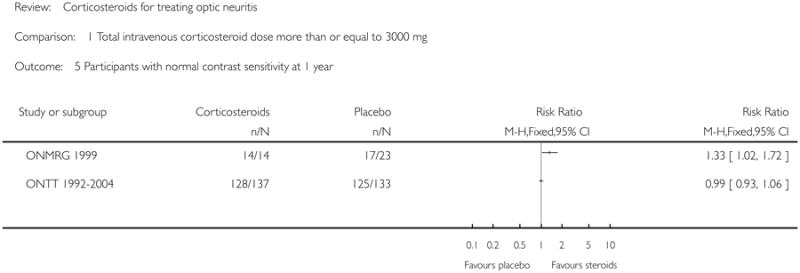

We do not report a meta-analysis for this outcome at one year since there was substantial statistical heterogeneity as evident from the I-square value of 83.4% and a P value of 0.01 for the chi-square test for heterogeneity. The risk ratio of normal contrast sensitivity at one year follow up was 1.35 (95% CI1.06 to1.72) in ONMRG 1999 and 0.99 (95% CI 0.93 to 1.06) in ONTT 1992-2004 (see Figure 5).

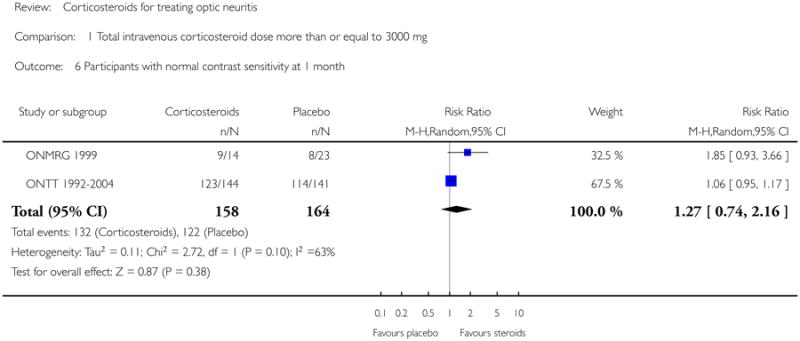

Similarly, we found substantial heterogeneity on this outcome at one month with data from ONMRG 1999 and ONTT 1992-2004 (I-square = 63.3% and P value for chi-square test = 0.10). Though the P value for the chi-square test is greater than 0.05, the test has low power with fewer studies and since the I-square value and the point estimates indicate presence of heterogeneity, we prefer not to report the meta-analysis. The risk ratio of normal contrast sensitivity at one month was 1.85 (95% CI 0.93 to 3.66) in ONMRG 1999 and 1.06 (95% CI 0.95 to 1.17) in ONTT 1992-2004 (see Figure 6).

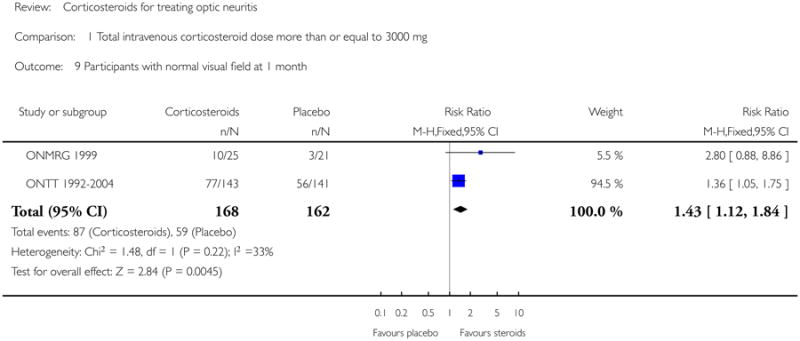

Visual field

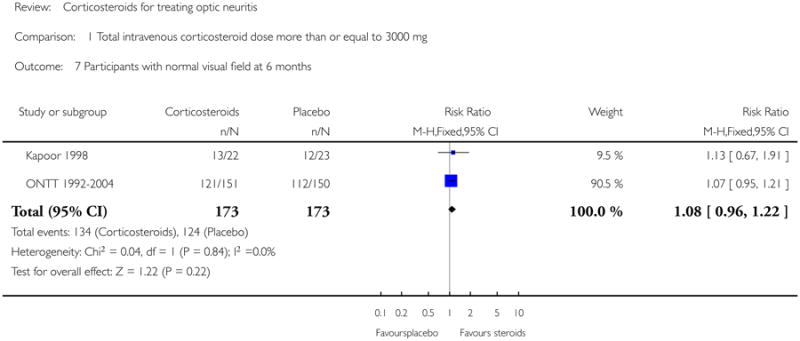

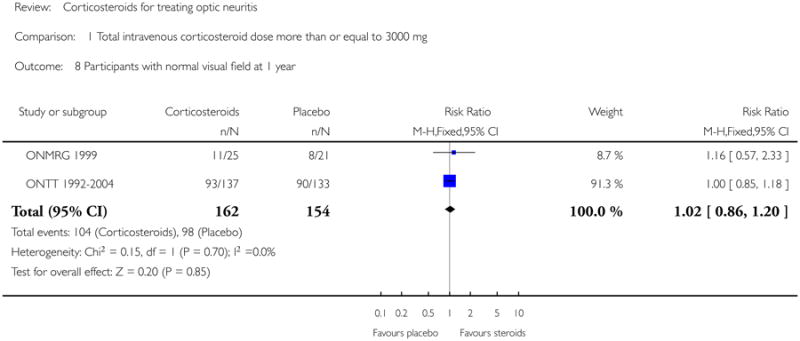

Data on visual field at six months was available from Kapoor 1998 and ONTT 1992-2004. The pooled risk ratio of normal visual field at six months follow up was 1.08 (95% CI 0.96 to 1.22) (see Figure 7). The P value for chi-square test for heterogeneity was 0.84 and the I-square value was 0%. For analyses at one year and one month data were available from ONMRG 1999 and ONTT 1992-2004. At one year the pooled risk ratio of normal visual field was 1.02 (95% CI 0.86 to 1.20) (see Figure 8). The pooled relative risk was 1.43 and statistically significant in favor of intravenous corticosteroids (95% CI 1.12 to 1.84) at one month follow up (see Figure 9). There was no statistical heterogeneity in these analyses.

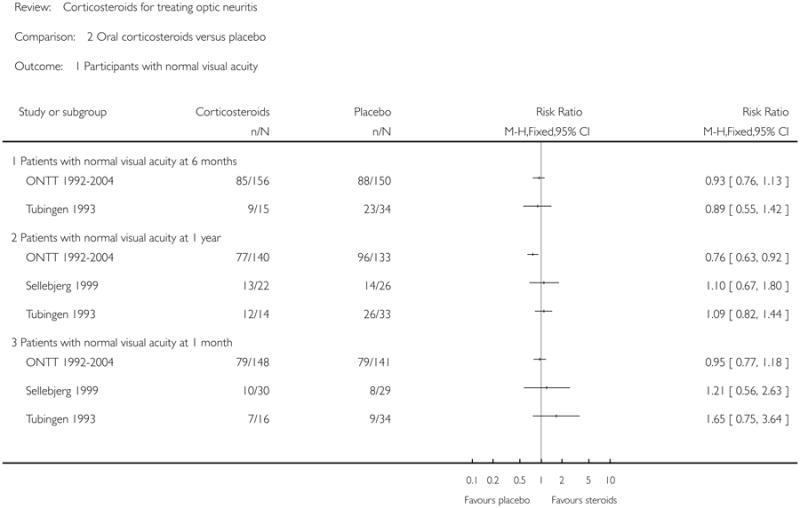

Oral corticosteroids versus placebo

Visual acuity

No meta-analysis was done. The relative risk for normal visual acuity at 6 months was 0.93 (95% CI = 0.76 to 1.13) in ONTT 1992-2004 and 0.89 (95% CI = 0.55 to 1.42) in Tubingen 1993. Relative risk of normal visual acuity at 1 year in ONTT 1992-2004 was 0.76 and was statistically significant in favor of placebo (95% CI = 0.63 to 0.92). Relative risk of normal visual acuity at one year was 1.09 (95% CI = 0.82 to 1.44) in Tubingen 1993 and 1.10 (95% CI = 0.67 to 1.80) in Sellebjerg 1999. Relative risk of normal visual acuity at one month did not achieve statistical significance in any of the three trials. The relative risk was 0.95 (95% CI = 0.77 to 1.18) in ONTT 1992-2004, 1.65 (95% CI = 0.75 to 3.64) in Tubingen 1993 and 1.21 (95% CI = 0.56 to 2.63) in Sellebjerg 1999.

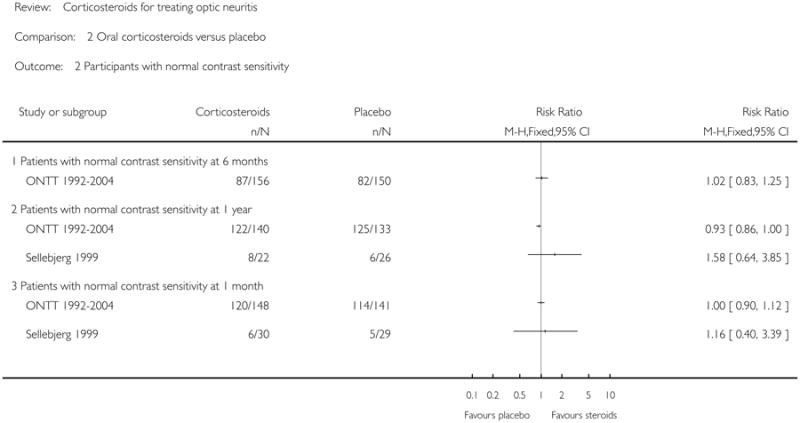

Contrast sensitivity

ONTT 1992-2004 was the only trial that reported this outcome at six months. The relative risk for normal contrast sensitivity at six months was 1.02 (95% CI = 0.83 to 1.25) in this trial. Relative risk of normal contrast sensitivity at one year was 0.93 (95% CI = 0.86 to 1.00) in ONTT 1992-2004 and 1.58 (95% CI = 0.64 to 3.85) in Sellebjerg 1999. Relative risk of normal contrast sensitivity at one month was 1.00 (95% CI = 0.90 to 1.12) in ONTT 1992-2004 and 1.16 (95% CI = 0.40 to 3.39) in Sellebjerg 1999.

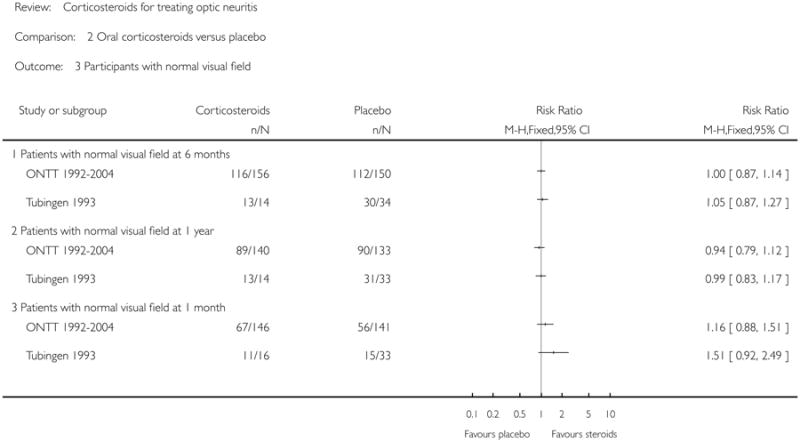

Visual field

None of the trials achieved statistical significance for this outcome. The relative risk for normal visual field at six months was 1.00 (95% CI = 0.87 to 1.14) in ONTT 1992-2004 and 1.05 (95% CI = 0.87 to 1.27) in Tubingen 1993. Relative risk of normal visual field at one year was 0.94 (95% CI = 0.79 to 1.12) in ONTT 1992-2004 and 0.99 (95% CI = 0.83 to 1.17) in Tubingen 1993. Relative risk of normal visual field at one month was 1.16 (95% CI = 0.88 to 1.51) in ONTT 1992-2004 and 1.51 (95% CI = 0.92 to 2.49) in Tubingen 1993.

Adverse effects

Adverse effects were reported in four of the five included trials. Kapoor 1998 did not report adverse effects. Sellebjerg 1999 reported no serious adverse effects and Tubingen 1993 reported only acne. The ONMRG 1999 reported hyperglycemia, constipation, diarrhea, acneiform eruption, hyperlipidemia, headache, and fever. The ONTT 1992-2004 reported depression, acute pancreatitis, weight gain, sleep disturbance, mild mood change, stomach upset, and facial flushing. The proportion of participants experiencing adverse effects of corticosteroid therapy was not consistently reported by all trials precluding any comparison.

Quality of life

Quality of life was assessed and reported only in ONTT 1992-2004 using patient-reported responses to the National Eye Institute Visual Functioning Questionnaire (NEI-VFQ) (Mangione 1998). However, no comparative quality of life data by assigned treatment arm were available.

Discussion

Acute demyelinating optic neuritis is a common form of optic neuritis, with inflammation of the optic nerve that may be associated with multiple sclerosis. Optic neuritis may be the initial manifestation of multiple sclerosis in some patients (Kurtzke 1985). In this systematic review evaluating the effects of corticosteroid therapy in patients with optic neuritis, we included five randomized placebo-controlled trials. We did not conduct a meta-analysis including all trials because of clinical heterogeneity resulting from variations in doses and routes of administration of corticosteroids. However, we conducted a meta-analysis of trials evaluating similar doses of corticosteroids (3000 mg or more) administered by the intravenous route. The ONTT (ONTT 1992-2004) was the largest of the included studies and contributed to most of the weight in all the meta-analyses. While none of the other included trials reported an evidence of benefit with intravenous corticosteroids, the results of their analyses were consistent with those in the ONTT (ONTT 1992-2004). Due to inverse variance weighting adopted in our meta-analyses, the smaller trials received much less weight compared with ONTT (ONTT 1992-2004).

The 95% confidence intervals for the pooled risk ratios of normal visual acuity, normal contrast sensitivity, and normal visual field at six months for intravenous corticosteroids arm in ONTT (ONTT 1992-2004) include the null value. This suggests no evidence of benefit with either oral or intravenous corticosteroids compared to placebo for the outcomes described above. This observation is consistent with the adjusted analyses for the ONTT (ONTT 1992-2004) when adjusted for baseline visual acuity (ONTT 1992-2004). However, a life-table analysis reported in the same paper found that the rate of return of vision to normal was higher with intravenous corticosteroids compared with placebo (P = 0.09 for visual acuity, 0.02 for contrast sensitivity and 0.0001 for visual field). No statistically significant difference was found for the same outcomes for oral corticosteroids compared with placebo in a life-table analysis in the trial report. Further, patients treated with oral corticosteroids in the same trial had a higher rate of new episode of optic neuritis compared with those in the placebo arm. A statistically significant benefit in terms of pooled relative risk of normal visual field at one month was observed in patients treated with intravenous corticosteroids (see Figure 9).

The trials evaluating oral corticosteroids were very heterogeneous in the dose of the medication. There was no evidence of benefit with oral corticosteroids for all outcomes considered. The 95% confidence intervals for the relative risk of normal visual acuity, contrast sensitivity and visual field included the null value. Oral corticosteroids, however, resulted in fewer patients achieving normal visual acuity compared with the placebo group at 1 year in ONTT 1992-2004 (see Figure 10). This difference was statistically significant.

Authors' Conclusions

Implications for practice

There is no conclusive evidence of benefit in terms of return to normal visual acuity, visual field or contrast sensitivity with either intravenous or oral corticosteroids at the doses evaluated by trials included in this review. Either no treatment or treatment with intravenous corticosteroid therapy followed by oral corticosteroids is appropriate; intravenous corticosteroids may benefit the patient in terms of faster recovery to normal vision. As suggested by analyses reported in the ONTT (ONTT 1992-2004), oral corticosteroid therapy may be associated with an increase in rate of new episodes of optic neuritis.

Implications for research

Among patient cohorts evaluated as part of this review, there was no conclusive treatment benefit with return to normal visual function measures as the outcome of interest. Future research efforts could focus on the identification of patient subgroups who might be predisposed to have permanent visual deficits and would benefit from some type of pharmacologic therapy which could reduce neural damage.

While neurological outcome was not the outcome of interest in this review, there are related areas, which may warrant future exploration. Future research to evaluate the role of high dose oral corticosteroids as a treatment option for optic neuritis may be warranted.

Plain Language Summary.

Corticosteroids for treating optic neuritis

Optic neuritis is an acute demyelinating disease of the optic nerve, which typically presents with sudden loss of vision. Visual deficit varies in severity and generally improves spontaneously over several months. This review included five trials evaluating corticosteroids given either orally or by intravenous route in patients with optic neuritis. There is no evidence of benefit with either oral or intravenous corticosteroids in terms of improvement of vision. However, one trial reported quicker recovery of vision with intravenous corticosteroid therapy.

Acknowledgments

Kay Dickersin, PhD, was instrumental in conception of this review. We are grateful to Graziella Filippini for peer review comments on the protocol for this review. Karen Blackhall at the editorial base of the Cochrane Eyes and Vision Group prepared and executed the electronic searches and Anupa Shah provided comments, guidance and support. We acknowledge assistance provided by Fabio Brusaferri and Livia Candelise in developing the protocol for this review. We thank Richard Wormald, Roberta Scherer, Kate Henshaw, Barbara Hawkins and Catey Bunce for their comments and input on earlier versions of this review. We acknowledge assistance and coordination provided by Stephen Gichuhi and others at the Cochrane Eyes and Vision Group (CEVG) Editorial Base and CEVG US Project.

Sources of Support: Internal sources

Brown University, USA.

Johns Hopkins University, USA.

External sources

Contract N-01-EY-2-1003, National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health, USA.

Characteristics of Studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Kapoor 1998.

| Methods | Method of randomization: “Randomized” (method not specified) Number randomized: 66 Exclusions after randomization: None Losses to follow up: 2 at last follow up (6 months) Method of allocation concealment: “Randomization was coordinated by the Hospital pharmacy and the coding was not accessible to clinicians or patients taking part in the study until the data came to analysis” (Personal communication) Participant masking: Yes Provider masking: Yes Outcome assessor masking: Yes Intention to treat analysis: No |

|

| Participants | Country and period of study: United Kingdom (March 1991 to June 1994) Age: 18 to 50 Sex: Short lesions: Overall, 74% were female |

|

| Interventions | Treatment: Intravenous methylprednisolone (1 g/day given as a single bolus) for 3 days Control: Intravenous saline for 3 days |

|

| Outcomes | Visual acuity Contrast sensitivity (measured using circular patches of luminance modulated vertical sinewave gratings) Visual field (Humphrey automatic perimetry using 30-2 protocol) |

|

| Notes | Follow up at 4, 8 weeks and 6 months | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors' judgement | Description |

| Allocation concealment? | Yes | A-Adequate |

ONMRG 1999.

| Methods | Method of randomization: “Randomly assigned by the envelope method” Number randomized: 102. Exclusions after randomization (total and per group): 32 dismissed after start of study due to different reasons including misdiagnosis and lost data. 2 patients excluded before treatment, 2 more during treatment due to waiver of consent by the patients. (Final: 66 - 33 Treatment, 33 Control groups). Exclusions per group not explicitly stated Losses to follow up: No loss to follow up Method of allocation concealment: Serially numbered in sealed opaque envelopes Participant masking: Yes Provider masking: No (attending physician was informed of the intervention) Outcome assessor masking: Yes Intention to treat analysis: No |

|

| Participants | Country and period of study: 22 centers in Japan (March 1991 to December 1996) Age: 14 to 58 (Mean 36.3 years) Sex: Overall, 69% were female |

|

| Interventions | Treatment: Intravenous methylprednisolone (1 g/d) for 3 days followed by oral corticosteroid for 7 to 10 days. Intravenous administration was carried out over 45 to 60 minutes once a day in the morning Control: Intravenous mecobalamin (500 ug/d) for 3 days, followed by oral mecobalamin for at least 7 days. Intravenous administration was carried out over 45 to 60 minutes once a day in the morning |

|

| Outcomes | Visual acuity (Measured using Landolt rings at 5 m after full refractive correction. Results expressed as decimal activity) Visual field (Humphrey 30-2 for central 30 degress of visual field and Goldmann perimetry for peripheral field if HFA unsuitable) Contrast sensitivity (Visual Contrast Test System at a testing distance of 1 m) |

|

| Notes | Data provided by Masato Wakakura about allocation concealment and outcomes Follow up at 1, 3, 4, 12 weeks and 12 months Four patients had definite or probable multiple sclerosis |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors' judgement | Description |

| Allocation concealment? | Yes | A-Adequate |

ONTT 1992-2004.

| Methods | Method of randomization: Randomized using permuted block design, stratified by clinical center Number randomized: 457 Exclusions after randomization: 2 patients found ineligible after randomization were excluded Losses to follow up: 17 at 6 months Method of allocation concealment: Bottles with pills prepared at a central location with a numbered envelope-type sealed label. Intact label was verified on return of the same to the central area Participant masking: Yes except for IV group Provider masking: Yes except for IV group Outcome assessor masking: Not for IV group. Only 6 % of testing in both the oral treatment arms at 6 months was performed by an individual who randomized the patient. Intention to treat analysis: Yes |

|

| Participants | Country and period of study: 15 centers in USA (July 1988 to June 1991) Age: 18 to 46, (mean 32 years) Sex: Overall, 77% were female |

|

| Interventions | Treatment 1: Intravenous methylprednisolone 250 mg every 6 hrs for 3 days followed by 1 mg/kg body weight of oral prednisone for 11 days Treatment 2: Oral prednisone 1mg/kg/day for 14 days, tapered with administration of 20 mg on day 15 and 10 mg on days 16 and 18 Control: Oral placebo 1 mg/kg/day for 14 days with similar treatment as oral corticosteroid group on days 15, 16 and 18 Adherence: All but 14 patients (3%) completed their course of treatment. Compliance was evaluated via comparison of the number of pills in each bottle returned to study headquarters, with the number expected from that participant. |

|

| Outcomes | Visual acuity (Retro illuminated Snellen ETDRS chart) Visual field (Humphrey Visual Field Analyzer and Goldmann perimeter) Contrast sensitivity (Pelli-Robson chart) Quality of life: Assessed using National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire (NEI-VFQ) - administered 5 to 8 years after acute optic neuritis, and again at 10 to 12 years after acute optic neuritis |

|

| Notes | Data provided by the Jaeb Center for Health Research in personal communication Follow up at days 4, 15; weeks 7, 13, 19; months 1, 6, 12; 2 and yearly thereafter |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors' judgement | Description |

| Allocation concealment? | Yes | A-Adequate |

Sellebjerg 1999.

| Methods | Method of randomization: Random number table; randomized in blocks of 10 using random numbers table and stratified as visual acuity < 0.1 and visual acuity of at least 0.1 Number randomized: 60, 30 to treatment; 30 to control Exclusions after randomization: No exclusions Losses to follow up: 5 in treatment group (1 patient after eight weeks and 4 after one year); 4 in control group at one year Method of allocation concealment: Numbered sealed envelopes, unopened by investigators until all patients completed the trial Participant masking: Yes Provider masking: Yes Outcome assessor masking: Yes Intention to treat analysis: No |

|

| Participants | Country and period of study: Denmark (August 1993 to January 1997) Age: 18 to 55 (median 32 years) Sex: 60% were female in treatment group and 63% were female in control group |

|

| Interventions | Treatment: Methylprednisolone tablets 500 mg once daily for 5 days, followed by 400, 300, 200, 100, 64, 48, 32, 16, 8 and 8 mg on each of the 10 following days Control: Identical looking tablets for 15 days (not explicitly stated) |

|

| Outcomes | Visual acuity (Snellen) Visual field not measured systematically (personal communication) Contrast sensitivity (Arden gratings. Normal defined as 80 points or less) |

|

| Notes | Dr. Sellebjerg provided 12 month data in personal communication We used 3 week data for 1 month outcome because data not collected at 1 month Follow up at weeks 1, 3, 8 and 12 months |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors' judgement | Description |

| Allocation concealment? | Yes | A-Adequate |

Tubingen 1993.

| Methods | Method of randomization: “Randomization list was made by the pharmaceutical company” (personal communication with Dr. Trauzettel-Klosinski) Number randomized: 44 of planned 100 patients were admitted and randomized to the study in 7 years Exclusions after randomization: 6 excluded after randomization due to poor adherence (3 in treatment and 3 in control group) Losses to follow up: 6 months: 1 treatment, 2 control; 12 months: 3 treatment, 3 control Method of allocation concealment: The randomization list, prepared by the pharmaceutical company and placed in a closed envelope was kept by a third person of the research group. It was not seen by the investigators before and during the evaluation of the data (personal communication) Participant masking: Yes except for 12 that were unmasked and chose the intervention they would receive (2 treatment, 10 control) Provider masking: Yes except for 12 that were unmasked and chose the intervention they would receive (2 treatment, 10 control) Outcome assessor masking: Yes Intention to treat analysis: No Unusual study design: 12 refused to participate under double-masked conditions and treated in unmasked manner but all were combined for data analysis |

|

| Participants | Country and period of study: Germany (1980 to 1986) Age: Mean age was 30.5 years and 29 years in treatment and control groups respectively Sex: 69% were female in treatment group and 74% were female in control group |

|

| Interventions | Treatment: Oral methylprednisolone for 24 days: 100, 80, 60, 40, 30, 20, 10, 5 mg for 3 days each Control: Oral Vitamin B1 for 24 days (100 mg/d) |

|

| Outcomes | Visual acuity (Snellen) Visual Field (Tubingen manual perimetry: profile perimetry and kinetic perimetry) Contrast sensitivity not reported |

|

| Notes | Dr. Trauzettel-Klosinski provided data for 1 month and 6 months in personal communication Criteria for diagnosis of optic neuritis employed for this study: Unilateral reduction of vision occurring over hours or days, at least two objective impairments on visual function including reduced and uncorrectable visual acuity, central scotoma, and pathological result of Aulhorn flicker test in patients with atypical scotoma, afferent pupil defect, normal or swollen optic disc Patients in treatment and control groups were given prophylactic aluminium-magnesium-silicate-hydrate, 550 mg three times a day Follow up at 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8 weeks and 3, 4, 5, 6, 9, 12 months |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors' judgement | Description |

| Allocation concealment? | Yes | A-Adequate |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Alejandro 1994 | This article was translated and reviewed. It describes a study that examined two routes of administration of corticosteriods and hence is outside the scope of this review. |

| Beran 1973 | This article is a retrospective comparison of those treated by glucocorticosteroids and foreign protein therapy. |

| Bhatti 2005 | This article is a review with no additional trials. |

| Bird 1976 | This article is a review and describes studies that were already reviewed by the authors of this study. |

| Bowden 1974 | Evaluated adrenocorticotropic hormone, a precursor of corticosteroids. |

| Brusa 1999 | This article examines a convenience sample from an RCT and hence does not satisfy the inclusion criteria for this review. |

| Brusaferri 2000 | This article is a meta-analysis of RCT on steroid treatment for optic neuritis. The articles included in this paper have already been reviewed by the authors of this review and determined not to contain additional data. |

| Chuman 2004 | This article reports a discussion on one of the included trials |

| Gould 1977 | This trial was originally selected for the included trials, but after detailed assessment of the methodological quality it was decided to exclude it because of inadequate randomization method. This trial included a single injection of triamcinolone into the orbit versus no injection. |

| Hallermann 1983 | This study is not an RCT and hence does not satisfy the inclusion criteria for this review. |

| Hickman 2002 | Trial was not initiated as per personal communication with Dr. Hickman. |

| Katz 1994 | This is a critical appraisal and comment on an included trial. |

| Kott 1997 | The intervention ‘copaxone’ is an amino acid polymer, not a corticosteroid and hence outside the scope of this review. |

| Pirko 2004 | This is not a trial and discusses natural history of optic neuritis. |

| Rawson (1966-69) | Evaluated adrenocorticotropic hormone, a precursor of corticosteroids. |

| Roed 2005 | Compares interventions not eligible for inclusion in this review. |

| Toczolowski 1995 | This article was translated and was determined not to be an RCT. |

| Trobe 1996 | The articles examines vision tests in optic neuritis and hence is not within the scope of this review. |

Data and Analyses

Comparison 1. Total intravenous corticosteroid dose more than or equal to 3000 mg.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Participants with normal visual acuity at 6 months | 2 | 346 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.06 [0.89, 1.27] |

| 2 Participants with normal visual acuity at 1 year | 1 | 270 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.06 [0.92, 1.22] |

| 3 Participants with normal visual acuity at 1 month | 1 | 285 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.08 [0.89, 1.31] |

| 4 Participants with normal contrast sensitivity at 6 months | 2 | 346 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.10 [0.92, 1.32] |

| 5 Participants with normal contrast sensitivity at 1 year | 2 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 6 Participants with normal contrast sensitivity at 1 month | 2 | 322 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.27 [0.74, 2.16] |

| 7 Participants with normal visual field at 6 months | 2 | 346 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.08 [0.96, 1.22] |

| 8 Participants with normal visual field at 1 year | 2 | 316 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.02 [0.86, 1.20] |

| 9 Participants with normal visual field at 1 month | 2 | 330 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.43 [1.12, 1.84] |

Comparison 2. Oral corticosteroids versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Participants with normal visual acuity | 3 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.1 Patients with normal visual acuity at 6 months | 2 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Not estimable | |

| 1.2 Patients with normal visual acuity at 1 year | 3 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Not estimable | |

| 1.3 Patients with normal visual acuity at 1 month | 3 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Not estimable | |

| 2 Participants with normal contrast sensitivity | 2 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2.1 Patients with normal contrast sensitivity at 6 months | 1 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Not estimable | |

| 2.2 Patients with normal contrast sensitivity at 1 year | 2 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Not estimable | |

| 2.3 Patients with normal contrast sensitivity at 1 month | 2 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Not estimable | |

| 3 Participants with normal visual field | 2 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3.1 Patients with normal visual field at 6 months | 2 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Not estimable | |

| 3.2 Patients with normal visual field at 1 year | 2 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Not estimable | |

| 3.3 Patients with normal visual field at 1 month | 2 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Not estimable |

Analysis 1.1. Comparison 1 Total intravenous corticosteroid dose more than or equal to 3000 mg, Outcome 1 Participants with normal visual acuity at 6 months.

|

Analysis 1.2. Comparison 1 Total intravenous corticosteroid dose more than or equal to 3000 mg, Outcome 2 Participants with normal visual acuity at 1 year.

|

Analysis 1.3. Comparison 1 Total intravenous corticosteroid dose more than or equal to 3000 mg, Outcome 3 Participants with normal visual acuity at 1 month.

|

Analysis 1.4. Comparison 1 Total intravenous corticosteroid dose more than or equal to 3000 mg, Outcome 4 Participants with normal contrast sensitivity at 6 months.

|

Analysis 1.5. Comparison 1 Total intravenous corticosteroid dose more than or equal to 3000 mg, Outcome 5 Participants with normal contrast sensitivity at 1 year.

|

Analysis 1.6. Comparison 1 Total intravenous corticosteroid dose more than or equal to 3000 mg, Outcome 6 Participants with normal contrast sensitivity at 1 month.

|

Analysis 1.7. Comparison 1 Total intravenous corticosteroid dose more than or equal to 3000 mg, Outcome 7 Participants with normal visual field at 6 months.

|

Analysis 1.8. Comparison 1 Total intravenous corticosteroid dose more than or equal to 3000 mg, Outcome 8 Participants with normal visual field at 1 year.

|

Analysis 1.9. Comparison 1 Total intravenous corticosteroid dose more than or equal to 3000 mg, Outcome 9 Participants with normal visual field at 1 month.

|

Analysis 2.1. Comparison 2 Oral corticosteroids versus placebo, Outcome 1 Participants with normal visual acuity.

|

Analysis 2.2. Comparison 2 Oral corticosteroids versus placebo, Outcome 2 Participants with normal contrast sensitivity.

|

Analysis 2.3. Comparison 2 Oral corticosteroids versus placebo, Outcome 3 Participants with normal visual field.

|

Appendix 1. Search strategy used for CENTRAL Issue 4, 2005 and National Research Register Issue 4, 2005

#1 CORTICOSTEROID/dt [Drug Therapy]

#2 GLUCOCORTICOID/dt [Drug Therapy]

#3 (corticosteroid$ or glucocorticoid$ or prednisone or prednisolone or methylprednisolone or triamcinolone).ab,ti.

#4 #1 or #2 or #3

#5 exp Optic Nerve Disease/

#6 ((optic$ or retrobul$) adj3 neuritis).ab,ti.

#7 #5 or #6

#8 #4 and #7

Appendix 2. MEDLINE search strategy used up to December 2005

#1 explode “Optic-Neuritis” / all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME,PT

#2 (((optic* next neuritis) or (retrobul* next neuritis)) in AB) or (((optic* next neuritis)or (retrobul* next neuritis)) in TI)

#3 #1 or #2

#4 ((corti?costeroid* or gluco?corticoid* or prednisone or triamcinolone or prednisone or methyl?prednisolone or prednisolone) in AB)or((corti?costeroid* or gluco?corticoid* or prednisone or triamcinolone or prednisone or methyl?prednisolone or prednisolone) in TI)

#5 explode “Adrenal-Cortex-Hormones” / all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME,PT

#6 explode “Glucocorticoids-” / all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME,PT

#7 #4 or #5 or #6

#8 #3 and #7

To identify randomized controlled trials, we combined this strategy with the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy phases one and two as contained in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2005a).

Appendix 3. EMBASE search strategy used up to January 2006

#1 explode “Optic-Neuritis” / all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME,PT

#2 optic* next neuritis

#3 retrobul* next neuritis

#4 #1 or #2 or #3

#5 corticosteroid* or glucocorticoid* or prednisone or triamcinolone or methylprednisolone or prednisolone

#6 explode “Adrenal-Cortex-Hormones” / all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME,PT

#7 explode “Glucocorticoids-” / all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME,PT

#8 #5 or #6 or #7

#9 #4 and #8

To identify randomized controlled trials, we combined this strategy with the following one:

#1 Randomized Controlled Trial/

#2 exp Randomization/

#3 Double Blind Procedure/

#4 Single Blind Procedure/

#5 random$.ab,ti.

#6 #1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5

#7 (animal or animal experiment).sh.

#8 human.sh.

#9 #7 and #8

#10 #7 not #9

#11 #6 not #10

#12 Clinical Trial/

#13 (clin$ adj3 trial$).ab,ti.

#14 ((singl$ or doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj3 (blind$ or mask$)).ab,ti.

#15 exp PLACEBO/

#16 placebo$.ab,ti.

#17 random$.ab,ti.

#18 experimental design/

#19 Crossover Procedure/

#20 exp Control Group/

#21 exp LATIN SQUARE DESIGN/

#22 #12 or #13 or #14 or #15 or #16 or #17 or #18 or #19 or #20 or #21

#23 #22 not #10

#24 #23 not #11

#25 exp Comparative Study/

#26 exp Evaluation/

#27 exp Prospective Study/

#28 (control$ or prospectiv$ or volunteer$).ab,ti.

#29 #25 or #26 or #27 or #28

#30 #29 not #10

#31 #30 not (#11 or #23)

#32 #11 or #24 or #31

Appendix 4. LILACS search terms used

(optic or retrobul$) and neuritis

Footnotes

Indicates the major publication for the study

Contributions of Authors: Conceiving the review SBF

Designing the review RB, RG, SBF

Coordinating the review SBF, SSV

Data collection for the review RG, SBF

Screening search results SBF, RG

Organizing retrieval of papers SBF, RG

Screening retrieved papers against inclusion criteria SBF, RG

Appraising quality of papers SBF, RG, SSV

Abstracting data from papers SBF, RG

Writing to authors of papers for additional information SBF, SSV

Obtaining and screening data on unpublished studies RG, SBF

Data management for the review SBF, SSV, RG

Entering data into RevMan SBF, SSV

Analysis of data SBF, SSV, RG, RB

Interpretation of data SBF, RG, SSV, RB

Providing a clinical perspective RB

Writing the review SBF, SSV, RG, RB

Securing funding for the review SBF, RB, RG, SSV

Declarations of Interest: Roy Beck is the primary investigator for the Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial.

References to studies included in this review

- Hickman SJ, Kapoor R, Jones SJ, Altmann DR, Plant GT, Miller DH. Corticosteroids do not prevent optic nerve atrophy following optic neuritis. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 2003;74(8):1139–41. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.8.1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones SJ, Miller DH, Kapoor R, Brusa A, Plant G. Double-blind controlled trial of methylprednisolone treatment for acute optic neuritis: 6-month follow-up with visual evoked potential measurement. Multiple Sclerosis. 1996;2 Suppl:32–3. [Google Scholar]

- *.Kapoor R, Miller DH, Jones SJ, Plant GT, Brusa A, Gass A, et al. Effects of intravenous methylprednisolone on outcome in MRI-based prognostic subgroups in acute optic neuritis. Neurology. 1998;50(1):230–7. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.1.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabuchi A, Kimura H, Inoue M. Optic neuritis treatment trial: Contrast sensitivity; assessment and results. Neuro-Ophthalmology Japan. 1998;15(1):30–6. [Google Scholar]

- *.Wakakura M, Mashimo K, Oono S, Matsui Y, Tabuchi A, Kani K, et al. Multicenter clinical trial for evaluating methylprednisolone pulse treatment of idiopathic optic neuritis in Japan. Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial Multicenter Cooperative Research Group (ONMRG) Japanese Journal of Ophthalmology. 1999;43(2):133–8. doi: 10.1016/s0021-5155(98)00071-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakakura M, Minei Higa R, Oono S, Matsui Y, Tabuchi A, Kani K, et al. Baseline features of idiopathic optic neuritis as determined by a multicenter treatment trial in Japan. Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial Multicenter Cooperative Research Group (ONMRG) Japanese Journal of Ophthalmology. 1999;43(2):127–32. doi: 10.1016/s0021-5155(98)00072-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck R. The optic neuritis treatment trial: three-year follow-up results. Archives of Ophthalmology. 1995;113(2):136–7. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1995.01100020014004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck RW, Cleary PA. Optic neuritis treatment trial. One year follow-up results. Archives of Ophthalmology. 1993;111(6):773–5. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1993.01090060061023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Beck RW, Cleary PA, Andersen MMJ, Keltner JL, Shults WT, Kaufman DI, et al. A randomized controlled trial of corticosteroids in the treatment of acute optic neuritis. The Optic Neuritis Study Group. New England Journal Of Medicine. 1992;326(9):581–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199202273260901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck RW, Cleary PA, Backlund JC. The course of visual recovery after optic neuritis. Experience of the Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial. Ophthalmology. 1994;101(11):1771–8. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(94)31103-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck RW, Cleary PA, Trobe JD, Kaufman DI, Kupersmith MJ, Paty DW, et al. The effect of corticosteroids for acute optic neuritis on the subsequent development of multiple sclerosis. New England Journal of Medicine. 1993;24:1764–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312093292403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck RW, Gal RL, Bhatti MT, Brodsky MC, Buckley EG, Chrousos GA, et al. Visual function more than 10 years after optic neuritis: experience of the optic neuritis treatment trial. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 2004;137(1):77–83. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(03)00862-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrousos GA, Kattah JC, Beck RW, Cleary PA. Side effects of glucocorticoid treatment. Experience of the Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial. JAMA. 1993;269(16):2110–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleary PA, Beck RW, Anderson MMJ, Kenny DJ, Backlund JY, Gilbert PR. Design, methods, and conduct of the Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial. Controlled Clinical Trials. 1993;14(2):123–42. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(93)90015-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole SR, Beck RW, Moke PS, Gal RL, Long DT. The National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire: Experience of the ONTT. The Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial. Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science. 2000;41:1017–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keltner JL, Johnson CA, Spurr JO, Beck RW. Visual field profile of optic neuritis. One year follow-up in the Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial. Archives of Ophthalmology. 1994;112(7):946–53. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1994.01090190094027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noseworthy J. Corticosteroids for optic neuritis ans subsequent development of multiple sclerosis. Annals of Neurology. 1994;120(Suppl 3):61. [Google Scholar]

- The Optic Neuritis Study Group. The 5-year risk of MS after optic neuritis: Experience of the optic neuritis treatment trial. Neurology. 1997;49(5):1404–13. doi: 10.1212/wnl.49.5.1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Optic Neuritis Study Group. Visual function 5 years after optic neuritis: Experience of the Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial. Archives of Ophthalmology. 1997;115(12):1545–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trobe JD, Arbor A The Optic Neuritis Study Group. One-year results in the optic neuritis treatment trial. Neurology. 1993;43:A280. [Google Scholar]

- Frederiksen JL. A double-blind randomized study of oral prednisolone versus placebo in patients with acute optic neuritis. Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences. 1993;20(Suppl 4) Abstract no. 7-18-15. [Google Scholar]

- Sellbjerg F, Jensen CV, Larsson HB, Frederiksen JL. Gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging predicts response to methylprednisolone in multiple sclerosis. Multiple Sclerosis. 2003;9(1):102–7. doi: 10.1191/1352458503ms880sr. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellebjerg F, Christiansen M, Jensen J, Frederiksen J. Immunological effects of oral high-dose methylprednisolone in acute optic neuritis and multiple sclerosis. European Journal of Neurology. 2000;7(3):281–89. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1331.2000.00074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Sellebjerg F, Nielsen HS, Frederiksen JL, Olesen J. A randomized, controlled trial of oral high-dose methylprednisolone in acute optic neuritis. Neurology. 1999;52(7):1479–84. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.7.1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellebjerg F, Schaldemose Nielsen H, Frederiksen JL, Olesen J. A placebo-controlled treatment trial of oral high-dose methylprednisolone in acute optic neuritis. Multiple Sclerosis. 1998;4:381. [Google Scholar]

- Trauzettel-Klosinski S. The Aulhorn flicker test: possibilities and limits. Its use in optic neuritis for diagnosis, differential diagnosis, monitoring the course of the disease, and assessing the effect of oral prednisolone. German Journal of Ophthalmology. 1992;1(6):415–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trauzettel-Klosinski S, Aulhorn E, Diener HC, Minder C, Pfluger D. The influence of prednisolone on the course of optic neuritis. Results of a double-blind study [Der einfluss von prednisolon auf den verlauf der neuritis nervi optici. Ergebnisse einer doppelblindstudie] Fortschritte Der Ophthalmologie. 1991;88(5):490–501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Trauzettel-Klosinski S, Axmann D, Diener HC. The Tubingen study on optic neuritis treatment - A prospective, randomized and controlled trial. Clinical Vision Sciences. 1993;8(4):385–94. [Google Scholar]

- Trauzettel-Klosinski S, Diener HC, Dietz K, Zrenner E. The effect of oral prednisolone on visual evoked potential latencies in acute optic neuritis monitored in a prospective, randomized, controlled study. Documenta Ophthalmologica. 1996;91(2):165–79. doi: 10.1007/BF01203696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

- Alejandro PM, Castanon Gonzalez JA, Miranda Ruiz R, Edgar Echeverria R, Adriana Montano M. Comparative treatment of acute optic neuritis with “boluses” of intravenous methylprednisolone or oral prednisone [Tratamiento comparativo de la neuritis optica aguda con “bolos” de metilprednisolona endovenosa o prednisona oral] Gaceta Medica de Mexico. 1994;130(4):227–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beran V, Hradecka V, Kohoutova O. Comparison of stimulation therapy with glucocorticoid therapy in optic nerve inflammation [Porovnani popudove terapie s lecbou glukokortikoidy u zanetu zrakoveho nervu] Ceskoslovenska Oftalmologie. 1973;29(5):372–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatti MT, Schmitt NJ, Beatty RL. Acute inflammatory demyelinating optic neuritis: current concepts in diagnosis and management. Optometry. 2005;76(9):526–35. doi: 10.1016/j.optm.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird AC. Treatment of acute optic neuritis. Transactions of the Ophthalmological Societies of the United Kingdom. 1976;96(3):412–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowden AN, Bowden PMA, Friedman AI, Perkin GD, Rose FC. A trial of conticotrophin gelatin injection in acute optic neuritis. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 1974;37:869–73. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.37.8.869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brusa A, Jones SJ, Kapoor R, Miller DH, Plant GT. Long-term recovery and fellow eye deterioration after optic neuritis, determined by serial visual evoked potentials. Journal of Neurology. 1999;246(9):776–82. doi: 10.1007/s004150050454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brusaferri F, Candelise L. Steroids for multiple sclerosis and optic neuritis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. Journal of Neurology. 2000;247(6):435–42. doi: 10.1007/s004150070172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuman H. 41st Annual Meeting of the Japanese Neuro-Ophthalmology Society, Kyoto, Japan, December 12-13, 2003. Journal of Neuro-Ophthalmology. 2004;24(2):170–74. doi: 10.1097/00041327-200406000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould ES, Bird AC, Leaver PK, McDonald WI. Treatmenf of optic neuritis by retrobulbar injection of triamcinolone. British Medical Journal. 1977;1(6075):1495–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6075.1495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallermann W, Haller P, Kruger C, et al. Progress of optic neuritis with and without corticosteroid treatment. Fortschritte der Ophthalmologie. 1983;80(1):30–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hick Man S. NOON Nitric oxide in optic neuritis: A phase I randomised double-blind study of rapid corticosteroid treatment of optic neuritis. National Research Register; UK: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Katz B. The Tubingen Study on Optic Neuritis Treatment - a prospective, randomized and controlled trial. Survey of Ophthalmology. 1994;39(3):262–3. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(94)90201-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kott E, Kessler A, Biran S. Optic neuritis in multiple sclerosis patients treated with copaxone. Journal of Neurology. 1997;244:S23–S24. [Google Scholar]

- Pirko I, Blauwet LK, Lesnick TG, Weinshenker BG. The natural history of recurrent optic neuritis. Archives of Neurology. 2004;61(9):1401–05. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.9.1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawson M, Liversedge LA, Goldfarb G. Treatment of acute retrobulbar neuritis with corticotrophin. Lancet. 1966;2:1044–6. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(66)92025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawson MD, Liversedge LA. Treatment of retrobulbar neuritis with corticotropin. Lancet. 1969;2:222. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(69)91469-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roed HG, Langkilde A, Sellebjerg F, Lauritzen M, Bang P, Morup A, Frederiksen JL. A double-blind randomized trial of IV immunoglobulin treatment in acute optic neuritis. Neurology. 2005;64(5):804–10. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000152873.82631.B3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toczolowski J, Lewandowska-Furmanik M, Stelmasiak Z, Wozniak D, Chmiel M. Treatment of acute optic neuritis with large doses of corticosteroids [Leczenie ostrego zapalenia nerwu wzrokowego za pomoca duzych dawek kortykosterydow] Klinika Oczna. 1995;97(5):122–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trobe JD, Beck RW, Moke PS, Cleary PA. Contrast sensitivity and other vision tests in the optic neuritis treatment trial. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 1996;121:547–53. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)75429-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies awaiting assessment

- Kommerell G. Treatment of optic neuritis with corticosteroids. Discussion at the 10th Meeting of the International Neuro-ophthalmological Society (Freiburg 5 to 9 June 1994) [Die Behandlung der Neuritis nervi optici mit Kortikosteroiden. Diskussion bei der 10. Tagung der International Neuro–ophthalmological Society (Freiburg, 5. bis 9.Juni 1994)] Klinische Monatsblatter Fur Augenheilkunde. 1994;205(3):126–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midgard R, Seland JH, Hovdal H, Celius EG, Eriksen K, Jensen D, Heger H, Mellgren SI, Wexler A, Beiske AG, Myhr KM. Optic neuritis: Diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Tidsskrift for Den Norske Laegeforening. 2005;125(4):425–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderstrom M. Corticosteroids and acute optic nerve neuritis. A therapeutic method requiring further studies [Kortikosteroider och akut opticusneurit Behandlingsmetod kräver ytterligare studier] Lakartidningen. 1995;92(5):387–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

- Beck RW. Optic Neuritis. In: Miller NR, Newman NJ, editors. Walsh and Hoyt's Neuro-ophthalmology. 5th. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins; 1998. pp. 599–647. [Google Scholar]

- Brusaferri F, Candelise L. Steroids for multiple sclerosis and optic neuritis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. Journal of Neurology. 2000;247(6):435–42. doi: 10.1007/s004150070172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebers GC. Optic neuritis and multiple sclerosis. Archives of Neurology. 1985;42(7):702–4. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1985.04060070096025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleishman JA, Beck RW, Linares OA, Klein JW. Deficits in visual function after resolution of optic neuritis. Ophthalmology. 1987;94(8):1029–35. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(87)33349-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. The Cochrane Library, Issue 3, 2005. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2005. Locating and selecting studies. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions 4.2.5. updated May 200, Section 55. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. The Cochrane Library, Issue 3, 2005. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2005. Assessment of study quality. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions 4.2.5. updated May 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs LD, Beck RW, SImon JH, Kinkel RP, Brownscheidle CM, Murray TJ, Simonian NA, Slasor PJ, Sandrock AW. Intramuscular interferon beta-1a therapy initiated during a first demyelinating event in multiple sclerosis. CHAMPS Study Group. New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;343(13):898–904. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200009283431301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch-Henriksen N, Hyllested K. Epidemiology of multiple sclerosis: incidence and prevalence rates in Denmark 1948-64 based on the Danish Multiple Sclerosis Registry. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica. 1988;78(5):369–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1988.tb03672.x. MEDLINE: 89115750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtzke JF. Optic neuritis or multiple sclerosis. Archives of Neurology. 1985;42(7):704–10. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1985.04060070098026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangione CM, Lee PP, Pitts J, Gutierrez P, Berry S, Hays RD. Psychometric properties of the National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire (NEI-VFQ). NEI-VFQ Field Test Investigators. Archives of Ophthalmology. 1998;116(11):1496–504. doi: 10.1001/archopht.116.11.1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez M, Siva A, Cross SA, O'Brien PC, Kurland LT. Optic neuritis: a population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Neurology. 1995;45(2):244–50. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.2.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders EA, Volkers AC, van der Poel JC, van Lith GH. Estimation of visual function after optic neuritis: a comparison of clinical tests. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 1986;70(12):918–24. doi: 10.1136/bjo.70.12.918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoor TC, Rockwell DL. Treatment of optic neuritis with intravenous megadose corticosteroids. A consecutive series. Ophthalmology. 1988;95(1):131–4. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(88)33220-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]