Abstract

The iron(IV)-oxo porphyrin π-cation radical known as Compound I is the primary oxidant within the cytochromes P450, allowing these enzymes to affect the substrate hydroxylation. In the course of this reaction, a hydrogen atom is abstracted from the substrate to generate hydroxyiron(IV) porphyrin and a substrate-centered radical. The hydroxy radical then rebounds from the iron to the substrate, yielding the hydroxylated product. While Compound I has succumbed to theoretical and spectroscopic characterization, the associated hydroxyiron species is elusive as a consequence of its very short lifetime, for which there are no quantitative estimates. To ascertain the physical mechanism underlying substrate hydroxylation and probe this timescale, ab initio molecular dynamics simulations and free energy calculations are performed for a model of Compound I catalysis. Semiclassical estimates based on these calculations reveal the hydrogen atom abstraction step to be extremely fast, kinetically comparable to enzymes such as carbonic anhydrase. Using an ensemble of ab initio simulations, the resultant hydroxyiron species is found to have a similarly short lifetime, ranging between 300 fs and 3600 fs, putatively depending on the enzyme active site architecture. The addition of tunneling corrections to these rates suggests a strong contribution from nuclear quantum effects, which should accelerate every step of substrate hydroxylation by an order of magnitude. These observations have strong implications for the detection of individual hydroxylation intermediates during P450 catalysis.

I. INTRODUCTION

Iron-oxo porphyrin π cation radicals, collectively known as Compound I (Cpd I), are among the most potent oxidizing agents employed in enzymatic catalysis. While present in numerous enzymes, including the catalases and peroxidases, Cpd I assumes its most reactive and chemically versatile form in the cytochromes P450 (P450s). In this case, Cpd I is coupled to the protein scaffold through a cysteine thiolate axial ligand, with the high reactivity of this species attributed to electron donation from the thiolate. The most representative P450 catalyzed reaction is C–H bond hydroxylation; however, the diverse capabilities of these enzymes extend as far as alkene epoxidation, dehalogenation, desaturation, and aromatic oxidation.1

P450-catalyzed alkyl hydroxylation is a two-stage process, initiated immediately upon formation of Cpd I within the enzyme active site.2 During the first step, a substrate C–H bond is activated and the hydrogen is abstracted by Cpd I to give a substrate-centered neutral radical and a hydroxyiron(IV) porphyrin species (FeOHPor). A hydroxy radical then “rebounds” to the substrate, affording the product and returning the enzyme to the ferric resting state (Figure 1). While Cpd I itself has been observed and characterized,3,4 the FeOHPor intermediate has escaped direct experimental detection under physiological conditions. Evidence for this second step, known as radical rebound, is nonetheless supported by a broad spectrum of indirect data including branching ratios of model reactions, kinetic isotopic effect studies, stereochemical retention measurements, radical clock experiments,2,5 and EPR spectroscopy of cryoisolated intermediates.6 Furthermore, a hydroxyiron(IV) species has been isolated in the less reactive chloroperoxidase from Caldariomyces fumago,7 and at high pH in CYP119 from Sulfolobus solfataricus and CYP158 from Streptomyces coelicolor.8

FIG. 1.

Cpd I-catalyzed substrate hydroxylation. Hydrogen atom abstraction by Cpd I (a) leads to formation of the hydroxyiron(IV) intermediate and a substrate-centered radical. This complex undergoes hydroxy-radical rebound to the substrate (b), yielding the hydroxylated product. The resultant species coordinates to the Fe(III) metal center until dissociation of the complex and release of product from the enzyme.

The primary factor preventing direct detection of FeOHPor in the P450s is the transient nature of this intermediate. Early investigations of ring-opening in highly strained substrates indicated an extremely short lifetime for FeOHPor.9 To quantify this, radical “clocks” were systematically developed, in which carefully calibrated rearrangements are used to bound the catalytic timescale through the distribution of hydroxylated products.10 A broad range of rate constants was obtained in these measurements, corresponding to lifetimes between 102 and 105 fs, with the least hindered radicals systematically possessing the shortest lifetimes.10–15 Since these lifetimes are comparable to the stretching frequency of a typical bond, the mechanistic foundation of this reaction remains controversial. Given the proximity of these times to the 170 fs limit for the lifetime of a semiclassical transition state at 300.0 K, it is possible that this may not correspond to a discrete, well-defined intermediate.

To resolve mechanistic ambiguity and guide experiment, ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulations of FeOHPor-facilitated substrate oxidation are used to estimate a reactive lifetime. In this context, conversion of propane to 2-propanol is employed as a model reaction for Cpd I chemistry. This corresponds to a simple substrate hydroxylation in which a radical intermediate is stabilized by alkyl branching, analogous to the prototypical oxidation of camphor to 9-exo-hydroxycamphor by P450cam from Pseudomonas putida (CYP101). The absence of alkene or aromatic functions in the chosen model eliminates the possibility of epoxidation or aromatic hydroxylation reactions which are mechanistically divergent from simple radical rebound.

AIMD, in particular the conjunction of Car–Parrinello dynamics and density functional theory (DFT), affords a means to simulate Cpd I/FeOHPor catalysis in a physically realistic manner at finite temperature16 while simultaneously providing potentials of mean force (PMF) for reactive processes through ensemble sampling. This method has proven highly efficacious for other heme proteins including the catalases and peroxides,17–22 and has been the subject of several excellent reviews.23,24 The thermodynamics of Cpd I and FeOHPor reactivity are thus characterized in a context that is more physically realistic than zero-temperature quantum chemical calculations, while simultaneously providing kinetic data including the lifetime for the highly reactive hydroxyiron species.

II. THEORETICAL METHODS

Models of the P450 active site were constructed using truncated representations of Cpd I, comprising iron(IV)-oxo porphine with an axial thiolate ligand and a propane substrate (Figure 1). The initial geometry of this Cpd I model was pruned from the crystallographic structure of cytochrome P450cam in complex with camphor (PDB code 1DZ9);25 however, no constraints from the protein scaffold were incorporated during later phases of calculation. Calculations were performed in the low-lying doublet and quartet configurations with the assumption that spin flip-interconversion does not occur along the reactive trajectory, following theoretical consensus.1 We have previously demonstrated that this system is sufficient to describe P450 Cpd I electronic structure using plane wave DFT at a level comparable to localized Gaussian basis set schemes.26,27 The combined Cpd I/propane system was assigned a net charge of zero.

Electronic structure calculations and ab initio dynamics were performed in the gas phase (ϵ = 1) using the CPMD 3.15.3 package.28 A cubic supercell measuring (17.5 Å)3 was employed, which is large enough to accommodate the catalytic center while permitting diffusion and reorientation of the ligand. Electronic states were converged to within 1 × 10−6 eV in both geometry optimizations and pure self-consistent field (SCF) calculations. Geometry optimizations were performed using the ODIIS algorithm29 until the force on each atom was less than 0.005 eV Å−1. The generalized gradient approximation (GGA) to DFT was utilized in the local spin density (LSD) approximation and electronic structure was treated using the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) density functional.30 In all cases, the gradient correction to the density was neglected when the electronic density was less than , where e is the fundamental unit of electronic charge and a0 is the Bohr radius. USPP calculations were executed using Vanderbilt pseudopotentials,31,32 a plane wave kinetic cutoff of 30 Ry, and a nonlinear core correction on the Fe atom.33 All physical quantities were evaluated at the Γ point due to the isolated nature of the system. Car-Parrinello simulations16 were performed using a fictitious electron mass of 700 a.u. and a 0.121 fs integration timestep. Nuclear dynamics were thermostatted at the initial velocity profile temperature of 300.0 K, with a thermostat frequency of 500 cm−1.34,35 PMFs for reactive trajectories was determined through Blue Moon Ensemble sampling (BME) in constrained simulations.36 Writing the mean constraint force 〈Fξ〉 as the gradient of the constraint potential V(ξ) so that , the PMF along the reaction coordinate ξ may be obtained through thermodynamic integration between endpoints ξ0 and ξ1 to give

| (1) |

Unless otherwise noted, free energy simulations were conducted for 1.2 ps post-equilibration to sample phase space distributions.

Atomic spin densities were determined using volumetric spin difference density profiles and Voronoi triangulation as implemented in the Bader 0.27 code.37–39 Volumetric data were calculated using a mesh with resolution equal to the finest Fourier grid employed in the corresponding PW calculations (180 × 180 × 180 real space mesh points). Spin contamination was found to be less than 10% using the total spin density as an estimator for 〈S2〉 via established methods.40

III. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

A. AIMD simulation and hydrogen atom abstraction

To explore all intermediates along the reactive pathway, AIMD simulations were performed in both high-temperature (T = 300.0 K) and low-temperature (T = 1.0 K) regimes. In this manner, the physiologically relevant reaction endpoint is accommodated along with any matrix-isolatable species that may be present during catalysis. As expected, the simulation temperature has a marked effect on the product distribution. During high-temperature simulations (T = 300.0 K) of Cpd I reactivity in the doublet state, the reaction is initiated through C–H bond activation and hydrogen atom abstraction, affording a neutral radical intermediate. The resultant hydroxyl radical then spontaneously rebounds to the substrate radical center to deliver the hydroxylated product (Figure 2). The effective free energy barrier for this process is calculated to be ΔAB (300.0 K) = 6.5 kcal mol−1, which is roughly ten-fold greater than kBT at 300 K (0.6 kcal mol−1). Using Eyring–Evans–Polanyi transition state theory as an approximation41–43 and employing the barrier PMF in place of the Gibbs free energy, the rate of this reaction

| (2) |

is found to be kS=1/2 (300.0 K) =1.24 × 108 reactions s−1, consistent with the high reactivity of Cpd I (adopting the usual convention for the inverse temperature β = 1/kBT). While this value is extremely large, exceeding that observed for ultrafast enzymes such as carbonic anhydrase,44 it should be noted that this does not account for conformational changes associated with substrate binding. The rate determining step(s) in catalytic turnover by the P450 are expected to be either the conformational changes associated with ligand entry and release or requisite processes such as gas migration and electron transfer from a redox partner. The large free energy change underlying hydroxylation ΔAX (300.0 K) = − 45.2 kcal mol−1 is on the order of 100 kBT, essentially ensuring irreversibility and steering the transformation to completion.

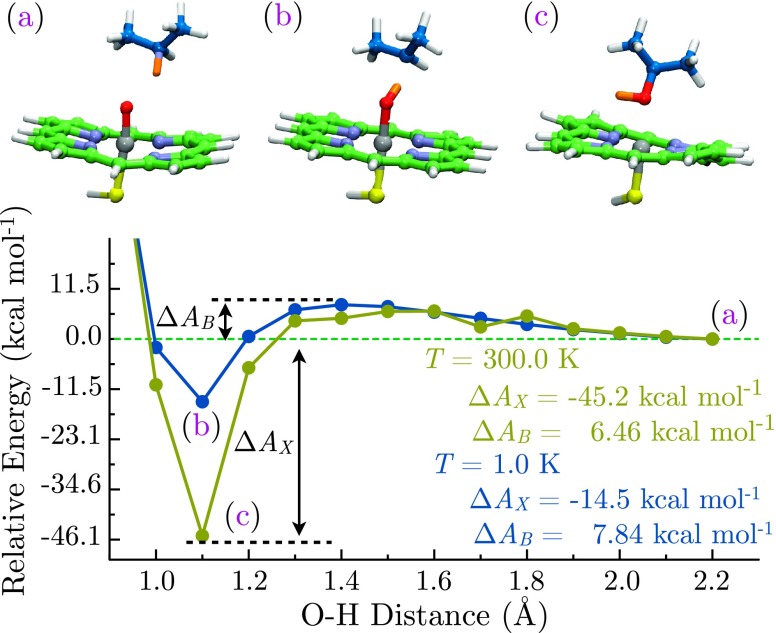

FIG. 2.

Free energy surface for Cpd I mediated propane hydroxylation in the S = 1/2 state at 300.0 K (gold) and 1.0 K (blue) as a function of FeO–H distance. Labeled points correspond to the reactant complex (a) and trapped hydroxyiron(IV) porphine (b), and the 2-propanol product state (c). Activation barriers ΔAB and exothermicities ΔAX are indicated at both simulation temperatures.

A different scenario is observed during low-temperature AIMD simulations (T = 1.0 K). The reaction is initiated in a manner identical to the high temperature limit, with hydrogen-atom abstraction from the substrate proceeding through an effective free energy barrier of ΔAB = 7.8 kcal mol−1. At this point, the low-temperature catalytic behavior is stymied, as the hydroxy radical does not spontaneously rebound. Instead, the system is trapped as the FeOHPor intermediate and a 2-propyl radical, corresponding to a free energy change of ΔAX = − 14.5 kcal mol−1. Appealing to transition state theory, a rate of kS=1/2 (1.0 K) = 6.13 × 10−1704 reactions s−1 is obtained at 1.0 K. FeOHPor is accordingly predicted to be cryoisolatable at 1.0 K in the limit of classical nuclei, as there will be no progression to products in the absence of tunneling or perturbation of this barrier by enzyme environmental effects. These observations are consistent with existing experimental data.4 Nonetheless, the calculated rebound barrier is smaller than kBT at 300.0 K, and the possibility of rebound through nuclear quantum effects at low temperature cannot be excluded. While tunneling may indeed play a role in hydrogen atom abstraction, as suggested by kinetic isotope effects4 and ab initio calculations,45 this remains unlikely for the hydroxyiron species due to the small de Broglie wavelength of the hydroxy radical (λH⋅ = 1.45 Å versus λHO⋅ = 0.35 Å, assuming a kinetic energy of (3/2) kT at T = 300.0 K).

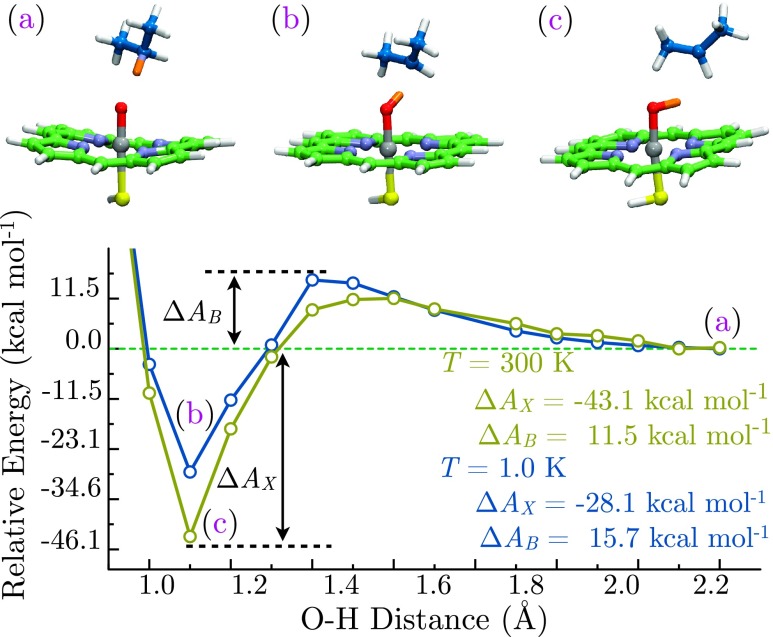

Reactivity patterns in the quartet state differ substantially from the doublet. In this case, AIMD simulations predict free energy barriers to be approximately twice those of the doublet in both high-temperature (ΔAX (300.0 K) = 11.5 kcal mol−1) and low-temperature regimes (ΔAX (300.0 K) = 15.7 kcalmol−1). Given that the doublet–quartet energy gap is expected to be 4.2 kcal mol−1 at the PBE/def2-TZVP level of theory and 2.8 kcal mol−1 in DFT + Ueff calculations (supplementary material46),26 the ratio of quartet to doublet occupancies should be at 300.0 K using DFT estimates (or 9.64 × 10−3 for DFT + Ueff; supplementary material46), and hence, the doublet state predominates. The contribution of the quartet to catalysis is further diminished by the sluggish high-temperature turnover rate for this state which is calculated to be kS=3/2 (300.0 K) = 2.49 × 104 reactions s−1, yielding a ratio kS=3/2 (300.0 K)/kS=1/2 (300.0 K) = 2.01 × 10−4 for a thermally driven mechanism. This is supported by the experimental determination of a doublet-predominant ground state via electron spin-resonance spectroscopies.4,47,48

The terminal point for quartet hydrogen atom abstraction likewise differs from the doublet. FeOHPor and the isopropyl radical remain on the lowest point of the free energy surface following hydrogen atom abstraction, irrespective of temperature, with no spontaneous radical rebound (Figure 3). A precipitous decrease in the terminal free energy ΔAX is nonetheless observed, with a magnitude comparable to (300.0 K) or greater than (1.0 K) the doublet case. This behavior is attributed to rapid dissociation of the isopropyl radical from the complex, occurring after less than 500 fs of simulation. This further underscores the importance of the doublet state for hydroxy radical rebound, with a relatively minor role played by the quartet. It should be noted that these observations are consistent with ground state PBE/def2-TZVP calculations, which predict a barrierless rebound for the doublet and a 2.5 kcal mol−1 barrier for quartet rebound (supplementary material46).

FIG. 3.

Free energy surface for Cpd I mediated propane hydroxylation in the S = 3/2 state at 300.0 K (gold) and 1.0 K (blue) as a function of FeO–H distance. Labeled points correspond to the reactant complex (a) and trapped hydroxyiron(IV) porphine (b), (c) on both surfaces. Activation barriers ΔAB and exothermicities ΔAX are indicated at both simulation temperatures.

The hybrid B3LYP49–51 functional is conventionally utilized for P450 chemistry. While the relative barrier magnitudes calculated using this method are highly instructive for prediction of product distributions, their absolute magnitudes are too large to give reasonable reaction rates. For instance, B3LYP calculations on an identical system, using a similarly sized localized basis, correspond to semiclassical rates of kS=1/2,B3LYP = 4.67 × 10−1 reactions s−1 and kS=3/2,B3LYP = 5.83 × 10−2 reactions s−1, with comparable values determined for other substrates.52 Our previous investigations demonstrated that the use of PBE affords decent agreement with its hybrid counterpart,26,27 while the experimentally consistent rate constants in this work indicate that this functional is a reasonable choice to treat reaction dynamics. Calculations on similar systems reveal the relative energetics of minima to be consistent within 2.6 kcal mol−1 between PBE and B3LYP, and hence, the thermodynamic endpoints herein are expected to be consistent with the literature at large.20

B. Spontaneous hydroxy radical rebound

The lifetime of many species, including Cpd I, peroxo, hydroperoxo, and FeOHPor, is poorly constrained by experiment despite the vast body of data delimiting the reactivity of these key intermediates in the P450 catalytic process. Mechanistic probes, including radical clock experiments, indicate that the hydroxyiron(IV) lifetime lies at the limit of transition state theory.10 To computationally estimate the lifetime of FeOHPor, simulations were performed in which the S = 1/2 configuration from simulations at T = 1.0 K was re-equilibrated at 300.0 K with the O–H distance restrained at the d(O–H) = 1.10 Å minimum obtained during free energy sampling. The constraint was then released and evolution of the resultant species was monitored.

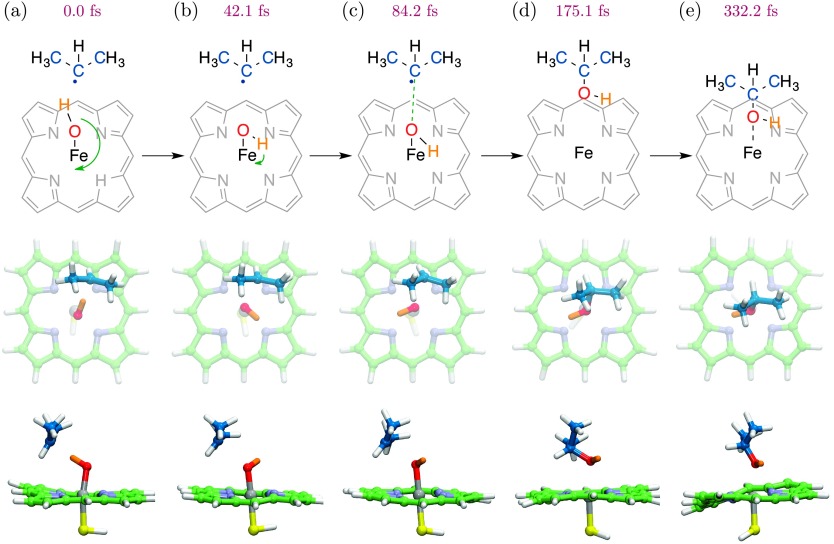

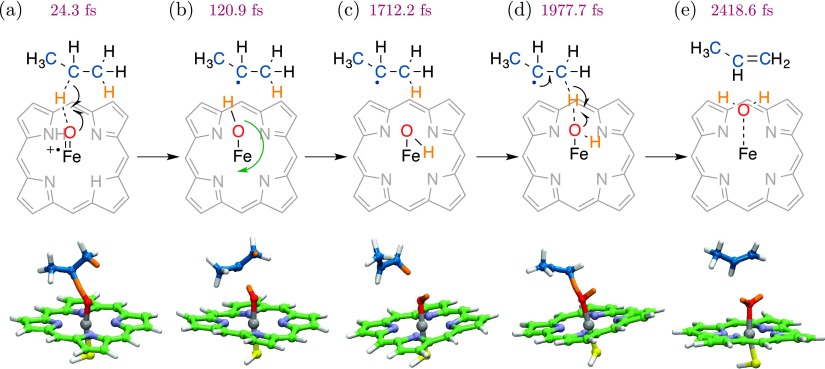

Hydroxy radical rebound begins through rotation of the Fe–OH moiety, as illustrated in a representative rebound trajectory (Figure 4). To initiate this process, the Fe–OH escapes a potential in which the hydroxy hydrogen atom is oriented toward the radical center of the substrate. A 180° rotation then occurs about the Fe–O axis, positioning the system for attack on the oxygen. Radical rebound follows, leaving the resulting 2-propanol coordinated to the Fe(III) center. This is the post-catalytic state of the enzyme, antecedent to product release.

FIG. 4.

Rebound trajectory for hydroxyiron(IV) porphine in the S = 1/2 state as initiated from the trapped geometry at d(O–H) = 1.10 Å (a). Initial rotation of the Fe–OH moiety (green arrow; (a) and (b)) prepares the system for hydroxylation by presenting electron density to the substrate. The radical center of propane approaches the bound OH, which proceeds to rebound as a hydroxy radical (c) and (d). The resultant 2-propanol coordinates to Fe(III) porphine.

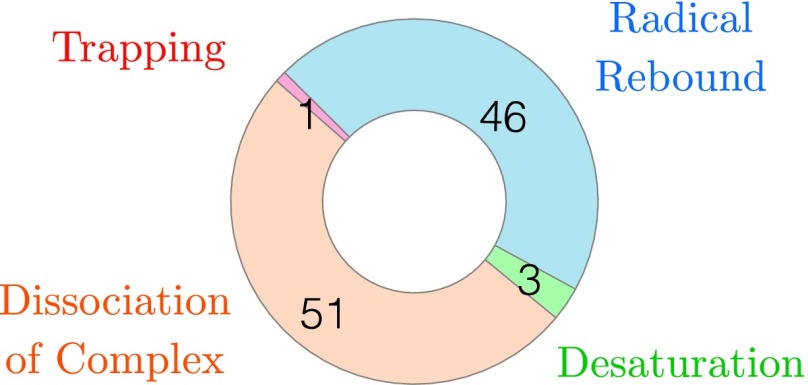

To estimate the lifetime for hydroxyiron(IV) porphyrin, the preceding calculations were repeated to generate an ensemble of 101 Car–Parrinello simulations. Divergent trajectories were generated by performing a minor randomization of the atomic coordinates (±0.1 Å) prior to simulation. Simulations were run for a total of 3600 fs, at which point the 2-propyl radical had undergone hydroxylation through radical rebound, had been desaturated to yield propene and water through the abstraction of a second substrate hydrogen atom, or had dissociated from the complex without reacting (Figure 5). Rebound was considered to have occurred at the first timestep where the substrate-oxygen distance was less than 1.44 Å, corresponding to the equilibrium distance for this bond in a ground state DFT calculation. In a single simulation, the Fe–OH rotor failed to escape the initial potential well, remaining oriented toward the radical center. An identical series of calculations was performed on the S = 3/2 surface. In this case, the complex uniformly dissociated, excepting a single instance of hydroxy radical rebound. While limited by sample size, this nonetheless suggests that only a few percent of quartet catalyzed hydrogen atom abstractions correspond to a productive reaction. During these calculations, the substrate is free to explore the simulation cell without external constraints, thereby sampling multiple rebound timescales.

FIG. 5.

Distribution of outcomes in the S = 1/2 state following 3.60 ps of simulation time for each trajectory of the 101 member ensemble. The number of instances observed for each reactive outcome is indicated numerically.

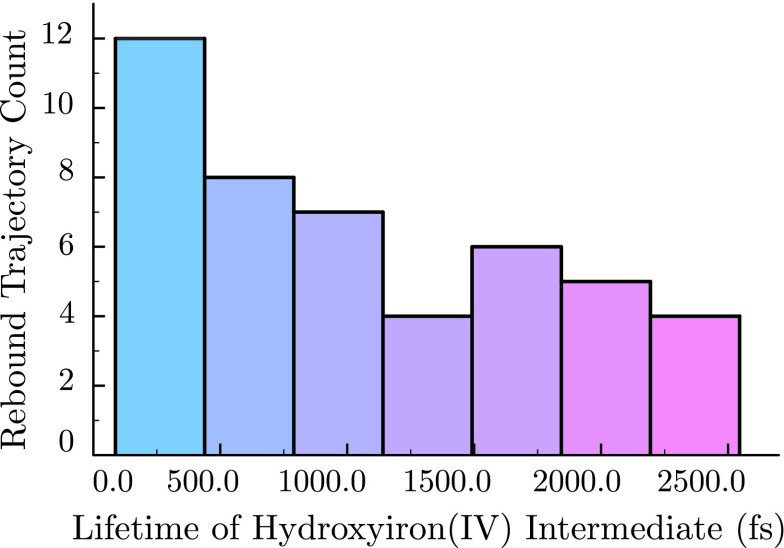

In a histogram of FeOHPor rebounds, the probability of observing a given lifetime decreases monotonically as a function of simulation time, with prominent occupation of the short-time reactivity bin (87.0 fs–438.2 fs) (Figure 6). If a given enzyme holds its substrate tightly in place, or if the ratio of substrate volume to active site volume approaches unity, the substrate will undergo little diffusion within the active site prior to reaction. The confined substrate then remains optimally oriented for rebound following the Fe–OH rotation step, promoting the fast reactivity represented by this portion of the histogram. Conversely, the slower rebounds observed in late time bins are representative of enzymes for which substrate diffusion readily occurs, such as those with weaker binding or very large active sites. It is generally accepted that substrates are held in a fixed orientation to permit formation of a very specific product. Under this assumption, the fast end of the histogram predicts a FeOHPor lifetime of approximately 300 fs, with the value increasing to ∼400 fs when including the second bin in a more conservative estimate. Even in the loosest binding enzymes, the lifetime of FeOHPor is not expected to surpass the 10 ps bound imposed on our simulations by computational limitations. Based on the high reactivity of the doublet, it is expected that longer simulations (tens of picoseconds) would afford either the hydroxylated or desaturated product once the substrate diffuses back to the FeOHPor center. It should be noted that the observed lifetimes are comparable to the 200 fs timescale obtained for hydroxy radical rebound in an earlier Born–Oppenheimer dynamics calculation.53 Nonetheless, this prior work comprised a single, unthermostatted trajectory initiated from a ground-state DFT transition state and hence cannot be interpreted as a representative distribution of reactive timescales.

FIG. 6.

Histogram of hydroxyiron(IV) porphine lifetimes, defined as the time from hydrogen atom abstraction to substrate hydroxylation in the S = 1/2 state following 3.60 ps of simulation time. A total 46 simulations within the ensemble exhibited this behavior.

Rebound dynamics indicate that rotation of the Fe–OH must occur before hydroxy radical rebound. The trapped substrate radical observed in the low temperature simulations (T = 1.0 K) of hydrogen atom abstraction may be attributed to the small kinetic energy of the Fe–OH rotor with respect to the radial rotation barrier about the porphyrin ring. Scanning this potential energy surface in absence of substrate at 1.0 K indicates a barrier of 58.6 kcal mol−1 (69.2 kcal mol−1) for the singlet (triplet) hydroxyiron(IV) species. This is substantially larger than kT = 2.0 × 10−3 kcal mol−1 at 1.0 K, and accordingly the energy present in a single thermal mode. This observation suggests a physical handle which may be exploited to facilitate detection of this intermediate using a combination of matrix isolation or time resolved spectroscopy.

C. FeOHPor thermodynamics

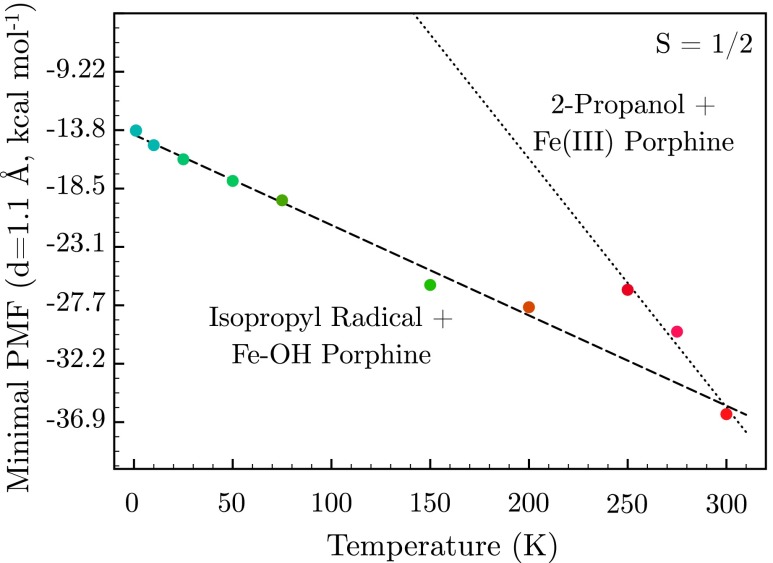

If FeOHPor is annealed from low temperatures, the system will proceed through a series of metastable states before rebounding to substrate. Provided that the residence timescale in each state is sufficiently long, it should be possible to perform a thermodynamic analysis for this rebound by calculating the PMF for hydrogen atom abstraction at a series of temperatures. Blue moon ensemble calculations were performed in the doublet state over 1.5 ps at temperatures spanning 1.0 K–300.0 K. As the temperature is increased, this affords a series of PMFs that exhibit a systematic decrease in the free energy barrier for hydrogen atom abstraction concomitant with broadening of the FeOHPor minimum (supplementary material, Figure S546). In the high temperature configurations obtained through this annealing protocol, the 2-propanol product did not coordinate to the Fe center. Thus, the terminal energy for the annealed product differs from that of the product complex analyzed in Sec. III A (Figure 2). The entropy ΔS is readily obtained from this PMF as

| (3) |

and the enthalpy follows immediately through the Gibbs relation ΔG = ΔH − TΔS. Using the free energy minimum on the hydrogen atom abstraction surfaces d(O–H) = 1.10 Å as a reference point, two distinct linear fits may be obtained. The fit predominating at low temperature (ΔH = − 14.3 kcal mol−1, ΔS = 7.2 × 10−2 kcal mol−1 K−1) corresponds to FeOHPor and the substrate radical (Figure 7). These thermodynamic parameters are consistent with a system undergoing exothermic hydroxy radical rebound to give the 2-propanol product once a sufficiently high temperature has been reached. This occurs concomitant with an increase in the vibrational density of states. Conversely, the high temperature fit (ΔH = 22.6 kcal mol−1, ΔS = 2.0 × 10−1 kcal mol−1 K−1) corresponds to a complex of Fe (III) porphine and the resultant 2-propanol, undergoing endothermic dissociation to liberate the free product. A crossover between these regimes is observed at 250.0 K. While these values are not expected to quantitatively reflect experimental observables, they corroborate the qualitative observations of Sec. III B and template a guide for further investigations.

FIG. 7.

Thermal scaling of the potential of mean force at d(O–H) = 1.10 Å on the hydrogen atom abstraction surface, as initiated from the S = 1/2 Cpd I doublet. Note the presence of two distinct fits corresponding to reactant (dashed line) and product states (dotted line).

D. Substrate desaturation

Propane was observed to undergo successive hydrogen atom abstractions during three simulations of substrate hydroxylation by a doublet Cpd I. These sequential reactions yield a water molecule, which remains coordinated to the porphyrin iron, and a desaturated product that diffuses away from the catalytic center. Desaturation follows a stepwise mechanism initiated through hydrogen atom abstraction by Cpd I, analogous to substrate hydroxylation. This is followed by rotation of the Fe–OH moiety by 180° away from the substrate (Figure 8). The substrate then translocates with respect to the catalytic center, moving the radical center further from the active site and positioning a second hydrogen atom adjacent to FeOHPor. This hydrogen is likewise abstracted, yielding water and propene. In simulated reactions, the mean time between the initial hydrogen abstraction and complete substrate desaturation was 1647 fs.

FIG. 8.

Representative trajectory for substrate desaturation by hydroxyiron(IV) porphine in the S = 1/2 spin state. The reaction is initiated through an initial hydrogen atom abstraction by Cpd I (a) and subsequent rotation of the Fe–OH moiety of hydroxyiron(IV) porphine (b). The substrate then translocates with respect to the catalytic center as opposed undergoing hydroxy radical rebound (c), leaving the complex poised for a second hydrogen atom abstraction (d). This yields the desaturated product and a water molecule coordinated to Fe(III) (e).

Desaturation has been experimentally observed for a number of P450 substrates including valproic acid,54–58 ezlopitant,59 sterols such as testosterone,60 and long chain fatty acids, including lauric acid.61 While two possible mechanisms may be devised for Cpd I-catalyzed desaturation, proceeding through either radical or carbocation intermediates, prior theoretical studies of trans-2-phenyl-iso-propylcyclopropane oxidation have suggested that a carbocation intermediate should dominate.62 To the contrary, our calculations indicate that neutral radical character is retained throughout the reaction during propane desaturation (supplementary material46). This does not necessarily contradict a carbocation mechanism for conjugated substrates or those with aromatic substituents, as these features should stabilize the formation of such an intermediate. Arguably, our determination of a neutral radical is biased by the inherent destabilization of charged species in the gas phase. While a condensed phase quantum mechanical/molecular mechanical (QM/MM) treatment improves the resolution and scope of computation, it is nonetheless generally accepted that gas-phase studies capture key aspects of P450 reactivity including desaturation62 with error well-bounded by numerous comparative studies.1 This is unsurprising as the active sites of these enzymes typically exclude solvent during catalysis and thus have low effective dielectric constants, making the gas phase approximation reasonable. By extension, QM/MM calculations have suggested that enzyme environmental effects may play a major role in determining the branching ratio between hydroxylation and desaturation.63 These studies have also indicated that tightly bound substrates are less likely to be desaturated as the intermediate radical is unable to reposition itself within the active site for the second hydrogen atom abstraction. Conversely, small or weakly bound substrates will diffuse freely and may more readily reorient themselves for desaturation. A consistent dependence of branching ratio on active site architecture and volume has been experimentally determined for valproic acid oxidation between P450 isoforms. These data support the simulations herein in which substantial substrate diffusion is required for desaturation.64

E. Nuclear quantum effects

The contribution of nuclear quantum effects to Cpd I and FeOHPor reactivity may be assessed using the semiclassical Wentzel–Kramers–Brillouin (WKB) approximation as a first-order approach. It is acknowledged from the outset that this formalism may underestimate contributions from tunneling during C–H activation as the de Broglie wavelength λH⋅ = 1.45 Å for the hydrogen atom is comparable to the width of the barrier region. Nonetheless, the WKB estimates may be considered a lower bound to determine if these effects contribute to Cpd I reactivity. The efficacy of this supposition is well established for hydrogen atom transfer with barriers of similar magnitude and width, supporting the merit of this approach.65–67 Within the scope of the WKB approximation, it can be shown that the semiclassical transmission coefficient γ through an arbitrary barrier region assumes the form (supplementary material46)

| (4) |

where the term is defined such that is the absolute value of the momentum for a particle with energy E traversing the potential V(x). The integral is taken over the classically forbidden domain bounded by the turning points x ∈ {a, b} such that V(x) − E = 0. Using this estimate for the transmission coefficient, the tunneling rate is given by k = fT, where f is the frequency of barrier crossing attempts. As a first order approximation, f is taken to be the zero point oscillator frequency f = 2954.25 cm−1 for a C–H stretch in propane.

Calculations performed between turning points at 300.0 K indicate that the tunneling rate for hydrogen atom abstraction on the doublet surface should be roughly one order of magnitude greater than the thermal rate (kS=1/2,therm (300.0 K) = 1.24 × 108 reactions s−1). (Table I) This drops by two orders of magnitude at low temperature; however, the predicted tunneling kinetics remain comparable to the fastest of enzymes. The quartet remains less reactive, with a rate nearly four orders of magnitude slower than the doublet. While these values are all quite large, they represent an extreme case in which the hydrogen atom enters the barrier at a point defined by its classical kinetic energy. In reality, the hydrogen is constrained by the C–H bond to lie a fixed distance from the barrier, particularly at low temperature, as the substrate is unlikely to move freely.

TABLE I.

Tunneling rates for hydrogen atom abstraction in doublet and quartet spin states as afforded by the semiclassical WKB approximation. Data are presented for the full interpolated potential from AIMD calculations, as well as for the case of a rectangular barrier with height equal to the maximum value of the potential. The domain of integration for the rectangular barrier is taken between the classical turning points (cp) or between the equilibrium extent of the substrate C–H bond and the exit turning point for the potential (long). All rates are given in reactions s−1.

| Spin state | Temperature (K) | AIMD, cp | AIMD, long | Rectangle, cp | Rectangle, long |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S = 1/2 | |||||

| 1.0 | 1.16 × 107 | 1.05 × 107 | 3.84 × 103 | 1.81 × 103 | |

| 300.0 | 4.45 × 109 | 8.31 × 108 | 1.19 × 108 | 7.96 × 105 | |

| S = 3/2 | |||||

| 1.0 | 9.39 × 104 | 9.40 × 104 | 2.18 × 10−4 | 2.18 × 10−4 | |

| 300.0 | 8.21 × 105 | 2.75 × 105 | 2.56 × 102 | 1.74 |

To further bound these approximations, calculations were performed in which the abstraction barrier was treated as (i) a rectangular potential between the turning points of the barrier derived from simulation and (ii) as a rectangular potential between the equilibrium position of hydrogen when bound to propane and the aforementioned turning point for barrier exit (Table I). These limiting cases further attenuate tunneling kinetics, particularly in (ii) where the barrier is longest. In this scenario, the tunneling rate for the doublet is approximately 1/100 of the thermally activated reaction rate as calculated using transition state theory at high-temperature (T = 300.0 K). The corresponding low-temperature (T = 1.0 K) tunneling rate is similarly attenuated, with a value two orders of magnitude slower than the high-temperature tunneling rate. It is notable that the quartet makes no meaningful through-barrier contribution in either temperature regimes for case (ii), underscoring earlier trends. Nonetheless, these observations suggest that doublet tunneling will nontrivially contribute to P450 catalysis even under conditions where it is suppressed.

It is notable that the doublet reaction is essentially barrierless after Fe–OH rebound has occurred. This process may proceed at low temperature through thermal activation alone; however, the large de Broglie wavelength for this species at T = 1.0 K suggests that this process could be accelerated through nuclear quantum effects. The only facet of hydroxylation left to consider is rotational motion of the Fe–OH moiety. In this regard, a similar worst-case estimate may be obtained by assuming that the hydrogen atom tunnels between the degenerate minima on the Fe–OH rotation surface in a straight-line path. Low-temperature scans indicate a free energy barrier of 3.3 kcal mol−1 at 1.0 K, with a distance of 1.06 Å between minima. Treating the barrier as a rectangular potential and applying the WKB approximation, a rate estimate of 7.20 × 105 reactions s−1 may be obtained, which is comparable to the rate for hydrogen atom abstraction. Taken together, these observations suggest that the entire hydroxylation reaction could proceed at low temperature through nuclear quantum effects alone.

IV. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

The calculations herein indicate that P450-catalyzed substrate hydroxylation is subject to a rich interplay between classical and quantum nuclear dynamics. From a classical standpoint, the entire hydroxylation reaction is expected to proceed extremely rapidly at 300.0 K. This is corroborated by the experimentally elusive nature of both Cpd I and FeOHPor intermediates. Conversely, at low temperature, the hydroxyiron(IV) species should be transiently isolatable though a cleverly designed cryoisolation scheme. The extreme reactivity predicted for P450 Cpd I initially appears at odds with the direct isolation of this species in CYP119 at 77.0 K in a cryogenic matrix.4 Nonetheless, the substrate was not present in these experiments, extending the residence time for Cpd I as this intermediate could only be eliminated through reaction with the protein scaffold. Enzyme environmental electrostatics have been demonstrated to tune P450 catalysis, alternately conferring and diminishing stability of a given species to afford the desired products.68–70 Given that this particular CYP119 is from a thermophilic organism, it could be argued that the enzyme active site architecture has evolved to facilitate P450 reactivity at high temperatures without damaging the host peptide. Hence, this enzyme may contain a more stable Cpd I than the other P450s.

The rebound reaction is also predicted to be very rapid, occurring during a 102 to 105 femtosecond period after hydrogen atom abstraction. The requisite rotation of the Fe–OH moiety about the Fe–O bond is essentially free diffusion in phase space at 300.0 K; however, this process is impeded at low temperature and thus may extend beyond 104 fs in the 1.0 K regime. Following rotation, the rebound timescale is dictated by substrate migration with respect to the catalytic center, explaining the disparate results obtained in radical clock experiments. In a tight binding enzyme, the substrate remains fixed in an optimal position to accept the hydroxy radical, corresponding to a short lifetime for the FeOHPor intermediate. Conversely, in a loose-binding enzyme, a longer lifetime is expected as the substrate may shift to an unfavorable conformation during the course of Fe–OH rotation, thus requiring reorientation prior to rebound. This process likewise defines a characteristic timescale for desaturation. During this reaction, the substrate translocates with respect to the catalytic center and a second hydrogen atom is abstracted to yield the desaturated product and water. In the case of an alkane reactant, this comprises proton-coupled electron transfer to a neutral radical substrate intermediate. At first glance, this observation seems to contradict an earlier theoretical study that predicts a carbocation intermediate during desaturation.62 This prior investigation nonetheless employed a substrate that intrinsically stabilizes a carbocation, and hence lies in a different context than our simple alkyl case. Accordingly, we believe the products expected from doublet Cpd I catalysis to be comprehensively accounted through the simulations herein. These experimental and theoretical data collectively indicate that the rate limiting step in P450 substrate hydroxylation is not related to the reaction with Cpd I but to some combination of substrate binding, product release, gas migration, and electron transfer.

The lifetime of hydroxyiron(IV) porphine is predicted to be hundreds to femtoseconds to picoseconds. A similar species was recently detected in CYP119 and CYP158 using Mossbauer spectroscopy at high pH, with a decay rate of 0.01 s−1.8 However, these enzymes were substrate free and possessed properties such as thermostability (CYP119) or a large active site (CYP158) which prevent the intermediate from reacting with the protein host. As such, the species is not captured in a reactive context. Under physiologically relevant conditions in a substrate loaded P450, the predictions of our simulations are expected to hold.

Quasiclassical rate estimates for hydrogen atom abstraction and Fe–OH rotation indicate that nuclear quantum effects should play a substantial role in P450 catalysis. The relative contribution of these effects in the condensed phase will likely depend on equilibrium details of the enzyme active site alongside the relative orientation between the substrate and catalytic center. Nonetheless, gas phase estimates comprise tunneling rates for hydrogen atom abstraction which range from ∼1/100 of the thermally activated rate at 300.0 K, up to the thermal rate itself. These tunneling kinetics are attenuated by approximately one order of magnitude at low temperature due to barrier reorganization and the reduced kinetic energy of a hydrogen atom incident on the barrier. The kinetics of Fe–OH rotation are predicted to occur at a similar rate, with the rebound reaction faster yet, attenuated only by low temperature nuances of the potential landscape as dictated by the protein scaffold. It is thus conceivable that nuclear quantum effects could drive the entire catalytic cycle at cryogenic temperatures, provided that the substrate and Cpd I are trapped within the enzyme active site. While prior variational transition state/multidimensional tunneling calculations have indicated that tunneling should play a significant role in P450 hydroxylation, this effect has not been addressed in other theoretical treatments.45 Nonetheless, large kinetic isotope effects are experimentally observed for C–H abstractions similar to our model system, including during testosterone 6β-hydroxylation,71 camphor hydroxylation,72 and norbornane oxidation.5 This suggests that quantum nuclear contributions should be relevant to this catalytic step.

The behavior of the quartet state is a notable point of divergence between our observations and the theoretical literature. Theoretical investigations of small alkene oxidation have underscored the so-called multistate reactivity hypothesis, in which different spin states of Cpd I preferentially catalyze distinct chemistry.73–78 Within this context, the doublet state has been associated with substrate hydroxylation, while the quartet has been associated with rearranged products, such as epoxides. These explorations nonetheless predict the quartet to be capable of catalyzing hydroxylation as a minority pathway. The simulations herein suggest that this scenario may be more sharply partitioned than previously assumed. The low occupation of the quartet relative to the doublet, in conjunction with its sluggish kinetics, diminishes the contribution of this state to the hydroxylation reaction during ab initio simulations. This is consistent with ground state DFT calculations which predict a barrierless rebound for the doublet and a 2.5 kcal mol−1 rebound barrier for the quartet (supplementary material46). In this case, the multistate reactivity hypothesis is not excluded but expected to be more divisive with respect to state-selective chemistry once finite temperature kinetic effects are taken into account.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Ohio Supercomputer Center and the VCU Center for Life Sciences for a generous allocation of computational resources. This work was supported by Grant No. R01GM092827 from the National Institutes of Health awarded to J.C.H.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shaik S., Kumar D., de Visser S. P., Altun A., and Thiel W., Chem. Rev. 105, 2279 (2005). 10.1021/cr030722j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Montellano P. R. O., Chem. Rev. 110, 932 (2010). 10.1021/cr9002193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kellner D. G., Hung S.-C., Weiss K. E., and Sligar S. G., J. Biol. Chem. 277, 9641 (2002). 10.1074/jbc.C100745200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rittle J. and Green M. T., Science 330, 933 (2010). 10.1126/science.1193478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Groves J. T., McClusky G. A., White R. E., and Coon M. J., Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 81, 154 (1978). 10.1016/0006-291X(78)91643-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davydov R., Makris T. M., Kofman V., Werst D. E., Sligar S. G., and Hoffman B. M., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 1403 (2001). 10.1021/ja003583l [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Green M. T., Dawson J. H., and Gray H., Science 304, 1653 (2004). 10.1126/science.1096897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yosca T. H., Rittle J., Krest C. M., Onderko E. L., Silakov A., Calixto J. C., Behan R. K., and Green M. T., Science 342, 825 (2013). 10.1126/science.1244373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Montellano P. R. O. and Stearns R. A., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 109, 3415 (1987). 10.1021/ja00245a037 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Newcomb M. and Toy P. H., Acc. Chem. Res. 33, 449 (2000). 10.1021/ar960058b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Atkinson J. K. and Ingold K. U., Biochemistry 32, 9209 (1993). 10.1021/bi00086a028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Newcomb M., Tadic M. H. L., Putt D. A., and Hollenberg P. F., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 117, 3312 (1995). 10.1021/ja00116a052 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Newcomb M., Shen R., Choi S.-Y., Toy P. T., Hollenberg P. F., Vaz A. D. N., and Coon M. J., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122, 2677 (2000). 10.1021/ja994106+ [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chandrasena R. E. P., Vatsis K. P., Coon M. J., Hollenberg P. F., and Newcomb M., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 115 (2004). 10.1021/ja038237t [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.He X. and de Montellano P. R. O., J. Biol. Chem. 279, 39479 (2004). 10.1074/jbc.M406838200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Car R. and Parrinello M., Phys. Rev. Lett. 55, 2471 (1986). 10.1103/PhysRevLett.55.2471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vidossich P., Alfonso-Prieto M., Carpena X., Loewen P. C., Fita I., and Rovira C., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 13436 (2007). 10.1021/ja072245i [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alfonso-Prieto M., Borovik A., Carpena X., Murshudov G., Melik-Adamyan W., Fita I., Rovira C., and Loewen P. C., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 4193 (2007). 10.1021/ja063660y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alfonso-Prieto M., Vidossich P., Rodriguez-Fortea A., Carpena X., Fita I., Loewen P. C., and Rovira C., J. Phys. Chem. A 112, 12842 (2008). 10.1021/jp801512h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alfonso-Prieto M., Biarnes X., Vidossich P., and Rovira C., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 11751 (2009). 10.1021/ja9018572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vidossich P., Fiorin G., Alfonso-Prieto M., Derat E., Shaik S., and Rovira C., J. Phys. Chem. B 114, 5161 (2010). 10.1021/jp911170b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alfonso-Prieto M., Oberhofer H., Klein M. L., Rovira C., and Blumberger J., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 4285 (2011). 10.1021/ja1110706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alfonso-Prieto M., Vidossich P., and Rovira C., Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 525, 37 (2012). 10.1016/j.abb.2012.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vidossich P. and Magistrato A., Biomolecules 4, 616 (2014). 10.3390/biom4030616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schlichting I., Berendzen J., Chu K., Stock A. M., Maves S. A., Benson D. E., Sweet R. M., Ringe D., Petsko G. A., and Sligar S. G., Science 287, 1615 (2000). 10.1126/science.287.5458.1615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elenewski J. E. and Hackett J. C., J. Chem. Phys. 137, 124311 (2012). 10.1063/1.4755290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elenewski J. E. and Hackett J. C., J. Comput. Chem. 34, 1647 (2013). 10.1002/jcc.23311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.CPMD, CPMD Program, Copyright IBM Corp. 1990–2008; Copyright MPI fur Festkorperforschung Stuttgart 1997–2001, http://www.cpmd.org.

- 29.Csaszar P. and Pulay P., J. Mol. Struct. 114, 31 (1984). 10.1016/S0022-2860(84)87198-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perdew J. P., Burke K., and Ernzerhof M., Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996). 10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.3865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vanderbilt D., Phys. Rev. B 41, 7892 (1990). 10.1103/PhysRevB.41.7892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laasonen K., Pasquarello A., Car R., Lee C., and Vanderbilt D., Phys. Rev. B 47, 10142 (1993). 10.1103/PhysRevB.47.10142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Louie S. G., Froyen S., and Cohen M. L., Phys. Rev. B 26, 1738 (1982). 10.1103/PhysRevB.26.1738 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tuckerman M. E. and Parrinello M., J. Chem. Phys. 101, 1302 (1994). 10.1063/1.467823 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tuckerman M. E. and Parrinello M., J. Chem. Phys. 101, 1316 (1994). 10.1063/1.467824 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sprik M. and Ciccotti G., J. Chem. Phys. 109, 7737 (1998). 10.1063/1.477419 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Henkelman G., Arnaldsson A., and Jonsson H., Comput. Mater. Sci. 36, 254 (2006). 10.1016/j.commatsci.2005.04.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sanville E., Kenney S. D., Smith R., and Henkelman G., J. Comput. Chem. 28, 899 (2007). 10.1002/jcc.20575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tang W., Sanville E., and Henkelman G., J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 21, 084204 (2009). 10.1088/0953-8984/21/8/084204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang J., Becke A. D., and V. H. Smith, Jr., J. Chem. Phys. 102, 3477 (1995). 10.1063/1.468585 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eyring H. and Polanyi M., Z. Phys. Chem. Abt. B 12, 279 (1931). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Evans M. G. and Polanyi M., Trans. Faraday Soc. 31, 875 (1935). 10.1039/TF9353100875 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eyring H., J. Chem. Phys. 3, 107 (1935). 10.1063/1.1749604 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lindskog S., Pharmacol. Ther. 74, 1 (1997). 10.1016/S0163-7258(96)00198-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang Y. and Lin H., J. Phys. Chem. A 113, 11501 (2009). 10.1021/jp901850c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.See supplementary material at http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.4907733E-JCPSA6-142-019507for DFT+Ueff calculations, localized basis potential energy surfaces, detailed thermodynamic analysis, semiclassical barrier transmission methods, spin densities, and geometries.

- 47.Rutter R., Hager L. P., Dhonau H., Hendrich M., Valentine M., and Debrunner P., Biochemistry 23, 6809 (1984). 10.1021/bi00321a082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim S. H., Perera R., Hager L. P., Dawson J. H., and Hoffman B. M., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 5598 (2006). 10.1021/ja060776l [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Becke A. D., Phys. Rev. A: At., Mol., Opt. Phys. 38, 3098 (1988). 10.1103/physreva.38.3098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee C., Yang W., and Parr R. G., Phys. Rev. B 37, 785 (1988). 10.1103/PhysRevB.37.785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Becke A. D., J. Chem. Phys. 98, 5648 (1993). 10.1063/1.464913 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kumar D., Altun A., Shaik S., and Thiel W., Faraday Discuss. 148, 373 (2011). 10.1039/c004950f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yoshizawa K., Kamachi T., and Shiota Y., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 9806 (2001). 10.1021/ja010593t [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rettie A. E., Rettenmeier A. W., Howald W. N., and Baillie T. A., Science 235, 890 (1987). 10.1126/science.3101178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rettie A. E., Boberg M., Rettenmeier A. W., and Baillie T. A., J. Biol. Chem. 263, 13733 (1988). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Porubeck D. J., Barnes H., Meier G. P., Theodore L. J., and Bailie T. A., Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2, 35 (1989). 10.1021/tx00007a006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kassahun K. and Baillie T. A., Drug. Metab. Dispos. 21, 242 (1993). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fisher M. B., Thompson S. J., Ribeiro V., Lechner M. C., and Rettie A. E., Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 356, 63 (1998). 10.1006/abbi.1998.0742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Obach R. S., Drug. Metab. Dispos. 29, 1599 (2001). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Korzekwa K. R., Trager W. F., Nagata K., Parkinson A., and Gillette J. R., Drug. Metab. Dispos. 18, 974 (1990). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Guan X., Fisher M. B., Lang D. H., Zheng Y.-M., Koop D. R., and Rettie A. E., Chem.-Biol. Interact. 110, 103 (1998). 10.1016/S0009-2797(97)00145-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kumar D., de Visser S. P., and Shaik S., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 5072 (2004). 10.1021/ja0318737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lai W., Chen H., Cohen S., and Shaik S., J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2, 2229 (2011). 10.1021/jz2007534 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rettie A. E., Sheffels P. R., Korzekwa K. R., Gonzalez F. J., Philpot R. M., and Baillie T. A., Biochemistry 34, 7889 (1994). 10.1021/bi00024a013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bell R. P., Proc. R. Soc. London, Ser. A 139, 466 (1933). 10.1098/rspa.1933.0031 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bell R. P., Proc. R. Soc. London, Ser. A 148, 241 (1935). 10.1098/rspa.1935.0016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bell R. P., Proc. R. Soc. London, Ser. A 154, 414 (1936). 10.1098/rspa.1936.0060 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sen K. and Hackett J. C., J. Phys. Chem. B. 113, 8170 (2009). 10.1021/jp902932p [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sen K. and Hackett J. C., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 10293 (2010). 10.1021/ja906192b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sen K. and Hackett J. C., Biochemistry 51, 3039 (2012). 10.1021/bi300017p [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Krauser J. A. and Guengerich P. F., J. Biol. Chem. 280, 19496 (2005). 10.1074/jbc.M501854200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Prasad B., Mah D. J., Lewis A. R., and Pletter E., PLoS One 8, e61897 (2013). 10.1371/journal.pone.0061897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.de Visser S. P., Ogliaro F., Harris N., and Shaik S., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 3037 (2001). 10.1021/ja003544+ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.de Visser S. P., Ogliaro F., and Shaik S., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 40, 2871 (2001). 10.1002/1521-3773(20010803)40:15%3C2871::AID-ANIE2871%3E3.0.CO;2-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.de Visser S. P., Ogliaro F., Sharma P. K., and Shaik S., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 11809 (2002). 10.1021/ja026872d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.de Visser S. P., Kumar D., and Shaik S., J. Inorg. Biochem. 98, 1183 (2004). 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2004.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hirao H., Kumar D., Thiel W., and Shaik S., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 13007 (2005). 10.1021/ja053847+ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kumar D., de Visser S. P., and Shaik S., Chem. - Eur. J. 11, 2825 (2005). 10.1002/chem.200401044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- See supplementary material at http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.4907733E-JCPSA6-142-019507for DFT+Ueff calculations, localized basis potential energy surfaces, detailed thermodynamic analysis, semiclassical barrier transmission methods, spin densities, and geometries.