Summary

Gene expression during early stages of fiber cell development and in allopolyploid crops is poorly understood. Here we report computational and expression analyses of 32,789 high-quality ESTs derived from Gossypium hirsutum L. Texas Marker-1 (TM1) immature ovules (GH_TMO). The ESTs were assembled into 8,540 unique sequences including 4,036 tentative consensus sequences (TCs) and 4,504 singletons, representing ~15% unique sequences in the cotton EST collection. Compared to ~178,000 existing ESTs derived from elongating fibers and non-fiber tissues, GH_TMO ESTs showed a significant increase in the percentage of the genes encoding putative transcription factors such as MYB and WRKY and the genes encoding predicted proteins involved in auxin, brassinosteroid (BR), gibberellic acid (GA), abscisic acid (ABA) and ethylene signaling pathways. Cotton homologues related to MIXTA, MYB5, GL2 and eight genes in auxin, BR, GA and ethylene pathways were induced during fiber cell initiation but repressed in the naked seed mutant (N1N1) that is impaired in fiber formation. The data agree with the known roles of MYB and WRKY transcription factors in Arabidopsis leaf trichome development and the well-documented phytohormonal effects on fiber cell development in immature cotton ovules cultured in vitro. Moreover, the phytohormone-related genes were induced prior to the activation of MYB-like genes, suggesting an important role of phytohormones in cell fate determination. Significantly, AA subgenome ESTs of all functional classifications including cell cycle control and transcription factor activity were selectively enriched in G. hirsutum L., an allotetraploid derived from polyploidization between AA and DD genome species, a result consistent with the production of long lint fibers in AA genome species. These results suggest general roles for genome-specific, phytohormonal and transcriptional gene regulation during early stages of fiber cell development in cotton allopolyploids.

Keywords: cotton, expressed sequence tags, fiber, gene expression, phytohormone, polyploidy

Introduction

The most extensively cultivated cotton species are allotetraploid Gossypium hirsutum L. (upland or American cotton) and G. barbadense L. (“Egyptian” cotton). Both allotetraploids originated in the New World from interspecific hybridization between species closely related to G. herbaceum L. (A1) or G. arboreum L. (A2) and an American diploid, G. raimondii L. (D5) or G. gossypioides (Ulbrich) Standley (D6) (Beasley, 1940). This polyploidization event is estimated to have occurred 1–2 million years ago (Wendel and Cronn, 2003; Wendel et al., 1995) and gave rise to a disomic allopolyploid consisting of five extant allotetraploid species (Percival et al., 1999). The AA progenitor species produce both lint (long) fibers that are spinnable into yarn and shorter fibers called fuzz. Note that lint fibers usually initiate on the day of anthesis, and fuzz fibers develop at a later stage. In contrast, the DD genome progenitor species produce very few lint fibers that are initiated pre-anthesis, but are much shorter in length than the lint fibers of the AA genome progenitor (Applequist et al., 2001). Compared to the AA and DD genome progenitors, the fiber traits in the allotetraploids are dramatically enhanced, suggesting that intergenomic interactions induce tissue-specific expression of homoeologous genes in cotton allotetraploids (Adams et al., 2003).

Cotton fibers are seed trichomes. During cotton fiber development, protodermal cells of ovules undergo several distinctive but overlapping steps including fiber initiation, elongation, secondary cell wall biosynthesis, and maturation, leading to mature fibers (Basra and Malik, 1984; Kim and Triplett, 2001; Tiwari and Wilkins, 1995; Wilkins and Jernstedt, 1999). In G. hirsutum, lint fibers develop prior to or on the day of anthesis, and the process is quasi-synchronized in each developing ovule and among ovules within each ovary (boll). Fuzz fiber development usually occurs in a later stage but varies among genotypes.

Transcription factors such as WD40 protein (TTG1), MYB (GL1 or WER), and basic helix-loop-helix protein (GL3 or EGL3) play a role in determining epidermal trichome cell patterning in Arabidopsis leaves (Glover, 2000; Hülskamp, 2004; Ramsay and Glover, 2005). This complex is thought to activate a homeodomain leucine-zipper protein (GL2) and a small family of single repeat MYB proteins without transcription activation domains (TRY, CPC, and ETC1). Interestingly, GL2 is an activator of downstream trichome-specific differentiation genes, whereas TRY (CPC or ETC1) is a negative regulator that represses trichome differentiation by competing with the MYB factors for the initiation complex.

Similar genes and pathways may be involved during seed trichome development in cotton, although cotton fibers are unicellular and never branch. GhMYB109, a putative ortholog of AtMYBGL1, is specifically expressed in cotton fiber initials and elongating fibers (Suo et al., 2003). GaMYB2, another R2R3 MYB transcription factor related to AtMYBGL1, complements the Arabidopsis glabrous1 (gl1) mutant. Moreover, ectopic expression of GaMYB2 induces a single trichome from the epidermis of Arabidopsis seed (Wang et al., 2004), and two cotton genes containing WD40 domains complement the Arabidopsis ttg1 mutant (Humphries et al., 2005). GhMYB25, a homolog of AmMIXTA/AmMYBML1 that control conical cell and trichome differentiation in Antirrhinum petals (Noda et al., 1994; Perez-Rodriguez et al., 2005), is predominately expressed in ovules and in fiber cell initials (Wu et al., 2006).

A recent study using microarray and quantitative gene expression analyses indicates that ethylene is involved in fiber cell elongation (Shi et al., 2006). Moreover, BR promotes fiber cell development on cultured cotton ovules (Sun et al., 2005) in a manner reminiscent of the well established requirement for plant hormones (GA and auxin) (Beasley and Ting, 1974). Collectively these data suggest critical roles for phytohormones in fiber cell development.

Obviously, cotton fiber cell initiation is a complex biological process that requires orchestrated changes in gene expression in developmental and physiological pathways (Arpat et al., 2004; Ji et al., 2003; Kim and Triplett, 2001; Lee et al., 2006; Li et al., 2002; Wilkins and Arpat, 2005). Many candidate genes that are expressed in fiber cells have been cloned and characterized (Delmer et al., 1995; John and Keller, 1995; Kim and Triplett, 2004; Orford and Timmis, 1997; Reinhart et al., 1996; Suo et al., 2003). For example, the expression of some genes is associated with the fiber elongation stage of development (John and Crow, 1992; Kim and Triplett, 2004; Ma et al., 1997; Orford and Timmis, 1997; Smart et al., 1998; Suo et al., 2003), whereas others are preferentially expressed during secondary cell wall thickening (Haigler et al., 2005; John and Keller, 1995; Reinhart et al., 1996; Wilkins and Jernstedt, 1999), or constitutively expressed throughout fiber development (Whittaker and Triplett, 1999).

The molecular events during fiber cell initiation are poorly understood. As of April 2006, the cotton EST collection in the public database (http://www.tigr.org/tigr-scripts/tgi/T_index.cgi?species=cotton) contained about 211,028 ESTs largely derived from G. arboreum L. (Arpat et al., 2004), G. hirsutum L. (Haigler et al., 2005; Li et al., 2002)B. Burr et al. http://www.biology.bnl.gov/plantbio/burr.html), and G. raimondii Ulbrich (Udall et al., 2006)J. Wendel et al., http://genome.arizona.edu/genome/cotton.html). The majority of fiber ESTs are derived from fibers in the early elongation stage (Arpat et al., 2004) or from the secondary wall synthesis stage of fiber development (Haigler et al., 2005). Therefore, new cotton EST sequences derived from tissues in the earlier stages of development from 3 days pre-anthesis (-3 DPA) to 3 days post-anthesis (+3DPA)1 are essential for uncovering additional genes involved in the complex biological networks leading to fiber cell differentiation. Here we report characterization of 32,798 ESTs derived from immature and fiber-bearing ovules in comparison with ~178,000 other cotton ESTs in the database. The data indicate that 1) a large number of ESTs are differentially represented in fibers and non-fiber tissues, 2) GH_TMO ESTs are highly enriched with genes encoding putative transcription factors and phytohormonal regulators, and 3) many AA subgenome ESTs are selectively enriched in G. hirsutum L. TM-1. A subset of genes encoding putative MYB transcription factors, auxin, BA, GA and ethylene regulators is induced during early stages of fiber cell development in TM-1 but repressed in the N1N1 mutant that produces very few lint fibers and no fuzz fibers. These results suggest important roles for transcription factors, phytohormonal regulators, and genome-specific gene regulation in the early stages of fiber cell development.

Materials and Methods

A full-length cDNA library of Gossypium hirsutum L. Texas Marker-1 (TM1) ovules (GH_TMO)

We grew G. hirsutum L. Texas Marker-1 (TM1) in a greenhouse at Texas A&M University and in the field at the USDA-ARS, New Orleans. Ovules were harvested at 3 days before anthesis (-3 DPA), the day of anthesis (0 DPA), and 3 days post-anthesis (3DPA) from a pool of 10–150 plants. Total RNA was extracted from immature ovules using a published method (Chang et al., 1993). An equal amount of RNA was pooled from three samples of each stage and sent to Invitrogen Corp. (Carlsbad, CA) for full-length cDNA library construction. Briefly, mRNA was isolated from the total RNA using a filter syringe containing oligo (dT). The first-strand cDNA was synthesized from 15 μg mRNA using SuperScript™III reverse transcriptase, and the second-strand cDNA was synthesized using E. coli RNase H, DNA polymerase I, and DNA ligase. The double-stranded cDNA was blunt-ended using T4 DNA polymerase, digested with NotI, size-selected using agarose gel electrophoresis, and directionally cloned into the NotI-EcoRV sites of pCMV•SPORT6.1. The ligated products were transformed using ELECTROMAX™DH10BT1 cells. After the library was plated, 23 clones were randomly selected for quality control. The colonies were arrayed in 384-well plates (51,072 clones in 133 384-well plates) in duplicate sets. One set was sent to TIGR for sequencing, and the other set was stored in a -70°C freezer.

EST sequencing and data analysis

Approximately 40,000 cDNA clones were single-pass sequenced primarily from the 5′ end at The Institute for Genomic Research (http://www.tigr.org) using the SP6 primer. Plasmid DNA was prepared using a modified alkaline lysis procedure and sequenced using Big Dye™ Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction reagents and ABI 3730xl Genetic Analyzers (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Following electrophoresis and fluorescence detection, quality values were assigned to each base call by TraceTuner software (Paracel, Inc., Pasadena, CA, USA), and Lucy (Chou and Holmes, 2001) was used to automatically process the raw sequence data, including trimming of low quality bases, vector and E. coli sequences, and those sequences less than 100 base pairs. The procedure for EST cleaning, assembly into tentative consensus (TC) groups, and annotation have been described previously (Quackenbush, 2001) (http://www.tigr.org/tdb/tgi/gifaq.shtml). ESTs were grouped into clusters by sequence similarity and clone links using the TGICL clustering utilities (Pertea et al., 2003). Each cluster was assembled at high stringency using the Paracel Transcript Assembler (Paracel, Inc.), to produce tentative consensus sequences (TCs). Those ESTs that did not assemble into a TC were termed “singletons”.

The Gene Ontology (GO) molecular functional class for each cotton sequence generated was assigned based on Arabidopsis GO SLIM (ftp://ftp.arabidopsis.org/home/tair/Ontologies/Gene_Ontology/ATH_GO_GOSLIM.20050723.txt). The cotton unique sequences were compared with the Arabidopsis proteome using BLASTX with an E-value of ≤-10. The GO functional class for the top Arabidopsis hit was assigned to each cotton sequence.

In silico analysis of gene expression in 5 different cotton EST libraries was performed using the method of Steckel et al. (2000). An expression profile matrix was built representing the frequency of EST within each TC in each library and imported into the IDEG6 software (Romualdi et al., 2003; Romualdi et al., 2001) to calculate R statistics (Stekel et al., 2000). Differentially expressed TCs were identified using a P-value of 0.001 and those with at least 5 ESTs were imported into MultiExperiment Viewer (MEV, TIGR) for hierarchical cluster analysis (Eisen et al., 1998).

To identify the presence of putative cotton candidate genes, the amino acid sequences of Arabidopsis genes involved in various biological pathways were downloaded from GenBank and compared with cotton EST sequences using TBLASTN with an E-value of ≤-10. Phylogenetic and molecular evolutionary analyses were conducted using MEGA version 3.0 (Kumar et al., 2004).

Analysis of Genome-Specific Polymorphisms (GSPs) and Simple Sequence Repeats (SSRs)

The most extensively cultivated cotton species, G. hirsutum and G. barbadense, are allotetraploids derived by combining two genomes probably from G. arboreum L. and G. ramondii L. ancestral species. Interestingly, if both genomes are transcriptionally active in the allopolyploid, the GH_TMO library was expected to contain ESTs derived from two homoeologous genomes. To estimate the relative abundance of the A- and D-genome ESTs in the library, we examined the presence of genome-specific polymorphisms (GSPs) among TCs with at least 5 ESTs in the Cotton Gene Index version 7 (CGI7). To avoid scoring sequencing errors as GSPs, we required that polymorphic nucleotides be present in at least two different libraries. AA- or DD-specific GSPs that could be consistently (100%) linked to the AA- or DD-genotype were identified. The criteria for classifying AA- or DD-GSPs were as follows: 1) more than one AA-EST carrying one GSP, 2) more than one DD-EST carrying the alternative GSP, 3) more than one AADD-EST carrying either the AA- or DD-GSP, and 4) each GSP from AADD-genotype must be 100% consistent with the AA-, or DD-GSP. Using these criteria, we inferred the origins of ESTs from either the AA or DD genome in GH_TMO library.

CGI7 sequences were analyzed for the presence of SSRs using MISA (Thiel et al., 2003). The minimum numbers of repeats specified were 20 for mononucleotide, 10 for dinucleotide, 7 for trinucleotide, and 5 for tetra- to hexanucleotide. A maximum length of interruption allowed between two repeats for compound repeats was 100-bp. Primers spanning each SSR were also designed automatically by piping the MISA output into Primer3 (http://www-genome.wi.mit.edu/genome_software/) using Perl script provided by MISA (http://pgrc.ipk-gatersleben.de/misa/primer3.html). The parameters for SSR detection and primer design were previously described (Kuhl et al., 2004).

A total of 3,977 SSRs were identified among 2,931 sequences, representing ~5.3% of the total unique sequences (55,673) in CGI7. The estimated frequency of SSRs among expressed sequences was one SSR per 11-kb, a value more frequent than one SSR per 20-kb observed in a previous report (Cardle et al., 2000). Mono-, di-, tri-, tetra-, penta-, and hexanucleotide repeats comprised about 70.4%, 9.6%, 13.3%, 3.8%, 1%, and 1.9% of the SSRs in CGI7.

Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNAs were subjected to treatment with RNase-free DNase I (Ambion Inc. Austin, TX) to remove residual DNA. The first strand cDNAs for each sample were made using random hexamers and Taqman Reverse Transcription Reagents (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Gene-specific primers were designed based on sequences from the CGI7 database using Primer Express v.2.0 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Samples and standards were run in duplicate on each plate. The quantitative PCR was repeated on at least two plates using an ABI7500 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Real-time RT-PCR was performed in a 20 μL reaction containing 7 μL ddH2O, 10 μL 2x PCR mix, 1 μL forward primer (1 μM), 1 μL reverse primer (1 μM), and 1 μL of template cDNA (10 ng/μL). The PCR conditions were two minutes of pre-incubation at 50°C, 10 minutes of pre-denaturation at 94 °C, 40 cycles of 15 seconds at 95 °C and one min at 60 °C, followed by steps for dissociation curve generation (30 seconds at 95 °C, 60 seconds at 60 °C and 30 seconds at 95 °C). The 7500 System SDS software v.1.2.2. was used for data collection and analysis. Dissociation curves for each amplicon were carefully examined to confirm the specificity of the primer pair used. Relative transcript levels for each sample were obtained using the “comparative CT method” (Litvak and Schmittgen, 2001). The threshold cycle (CT) value obtained after each reaction was normalized to the CT value of 18S rRNA. The relative expression level was obtained by calibrating the ΔΔCT values for other samples using a normalized CT value (ΔΔCT) for the TM-1 (3 DPA).

The primer pairs are 18S-forward AAGACGGACCACTGCGAAAG and 18S-reverse ATCCCTGGTCGGCATCGT; TC76794-forward GCCTCCTGCGCCTCAA and TC76794-reverse GAGGCAGTGAGGGTCTTGCA; DT565265-forward GCATAACACGACTCAAAGTGATCAG and DT565265-reverse TTTCAGAAATGATGAAGGCACATT; TC69611-forward ACCCTTGGCTGGAAAAAGTTC and TC69611-reverse GGCAAGTGTTGCCAGATCATC; TC65017-forward GGCTTGAGGCAATACGGTAATT and TC65017-reverse AGGCGGCTAGCACATCGTT; TC77907-forward CTTAAGACGCTTGATCTCAGCTACA and TC77907-reverse CGGCAAGGTTCCGATTGA; TC70523-forward GCGGCTTCCAGGCTTGA and TC70523-reverse ACTGCCACCGATTCTTTTGG; TC66418-forward CCAAGTTCCGACAATGTTATGC and TC66418-reverse CCAACAGCTCGTCCGACAA; DT553497-forward TTGCACAACACTTGCCTGGA and DT553497-reverse GCTGTTTCGCCTGTTTTTGG; DT559244-forward CAACCGGTAACCCCAAGGAT and DT559244-reverse GCCTGGCTTCGGCTTCTAAC; TC67212-forward CCTAAAACCGATGCACTCGG and TC67212-reverse ACTCTCCCATTGAGCCATGTG; DT556361-forward AGAGACGTTATGGATTGCGGA and DT556361-reverse TCGTGAAAGGTCGGAGGAAT; TC64087-forward CGATGTTGGCAAGCTGAACA and TC64087-reverse GTCACTGCCTAGCGGGAAGT; and TC67135-forward TGTATCAACAAGACCCCAGGC and TC67135-reverse CGCATTACTTGCTCTTGGGC (for SSCP analysis, see below).

Single-Strand Conformation Polymorphism (SSCP) analysis

SSCP gel electrophoresis was performed in a 12% polyacrylamide gel, 1xTBE, 10% ammonium persulfate, and 0.05% (v/v) TEMED. Each PCR product (~200-bp) was pre-examined in a 1% agarose gel, mixed with an equal volume of 2 x SSCP gel loading dye (0.05% bromophenol blue, 0.05% xylene cyanol, 95% formamide, 20 mM EDTA), denatured at 94 °C for 5 min, and cooled on ice prior to loading. Electrophoresis was performed in 0.5xTBE at 200V for ~16 hrs at room temperature. The gel was fixed in 10% acetic acid for 30 min, washed with deionized H2O three times at 5 minutes each, incubated in silver staining solution (0.1% silver nitrate and 0.15% formaldehyde) for 30 minutes, briefly washed in H2O for 5 seconds, and incubated in pre-cooled developing solution (3% Na2CO3, 0.15% formaldehyde, 0.024% Na2S2O3). When clear bands appeared, the developing solution was decanted, and 10% acetic acid was added to stop development. Gel images were taken using a CCD camera.

Results

The GH_TMO full-length cDNA library contained 4.2×106 cfu with ~99% colony recovery and >60% full-length cDNA inserts with an average insert size of 1.53-kb. A total of 32,789 high-quality EST sequences were obtained after removal of vector, poly-A, and contaminating microbial sequences. The average EST length was 763-bp, and ~78% were >700-bp. The average length of GH_TMO ESTs was ~120-bp longer than those of other cotton ESTs in the database.

EST sequence assembly, annotation, and cluster analysis

The ESTs were assembled into 8,540 unique sequences, consisting of 4,036 tentative consensus sequences (TCs) and 4,504 singletons. The average length was 881-bp for all unique sequences, 1,050-bp for TCs, and 730-bp for singletons. The Cotton Gene Index 6 (CGI6, http://www.tigr.org/tigr-scripts/tgi/T_index.cgi?species=cotton) as of April 2006 contained 40,348 unique sequences. We revised CGI6 using all EST (211,028) sequences downloaded from NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) including those generated in this study. The CGI7 contained 55,673 unique sequences, of which 21,900 were TCs and 33,773 singletons. The average length was 834-bp for unique sequences, 1,077-bp for TCs, and 590-bp for singletons.

Approximately 15% of the total unique sequences in CGI7 were derived exclusively from the GH_TMO library, of which 2,686 (~4.8%) including 654 TCs and 2,032 singletons were GH_TMO-specific transcripts that were enriched in ovules during the earliest stage of fiber development (from -3 to 3 DPA) compared to other ESTs (Supplementary Table 1).

The putative functions for all unique sequences were assigned using BLAST searches against the non-redundant (NR) protein database. About 26% of the sequences in CGI7 were putative cotton-specific sequences (no hits). Table 1 indicates the 30 most abundantly expressed TCs encoding predicted proteins such as protodermal factors (TC1 and TC2), peroxidase (TC4), mitochondrial carrier protein (TC23), alpha-expansin (TC12), and E6-fiber protein (TC47). Many of these abundant transcripts were found only in the GH_TMO library.

Table 1.

The top 30 most abundant transcripts in GH_TMO

| * TC # | **# of ESTs | Putative Function |

|---|---|---|

| TC1 | 502 | Protodermal factor 1 |

| TC4 | 303 | Peroxidase precursor |

| TC2 | 268 | Protodermal factor 1 |

| TC23 | 172 | Mitochondrial carrier protein family |

| TC12 | 158 | Alpha-expansin precursor |

| TC2034 | 151 | Pentameric polyubiquitin |

| TC6 | 147 | Alpha-tubulin |

| TC10 | 130 | Adenosylhomocysteinase |

| TC24 | 129 | Cytochrome P450 like_TBP thylakoid binding protein |

| TC2026 | 129 | S-adenosylmethionine synthetase 2 |

| TC2050 | 123 | Flavonoid 3′,5′-hydroxylase |

| TC2047 | 119 | Expressed protein (At5g12010) |

| TC2041 | 115 | Chalcone synthase 1 |

| TC2044 | 111 | Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase |

| TC2052 | 110 | Flavanone 3-hydroxylase |

| TC25 | 109 | Heavy-metal-associated domain-containing protein |

| TC34 | 108 | Phi-1 protein |

| TC11 | 94 | Adenosylhomocysteinase |

| TC38 | 90 | Expressed protein (At1g09750) |

| TC7 | 85 | Tubulin alpha-4 chain |

| TC2035 | 83 | Polyubiquitin |

| TC2055 | 82 | Tuber-specific and sucrose-responsive element binding factor |

| TC2042 | 82 | Chalcone synthase 1 |

| TC2039 | 80 | Histone H1 |

| TC2053 | 78 | 60S acidic ribosomal protein P0 |

| TC42 | 74 | Inositol-3-phosphate synthase |

| TC2070 | 72 | Cytochrome P450 |

| TC18 | 72 | Elongation factor 1-alpha |

| TC2071 | 70 | 60S ribosomal protein L4 |

| TC47 | 70 | E6 |

TC numbers are from the GH_TMO unique sequence set (Supplementary Data 2)

The number of ESTs present in each TC

To determine functional distributions of ESTs, we analyzed the percentage of Gene Ontology (GO) molecular function classes for the GH_TMO ESTs, CGI6 and CGI7 gene indices, and the Arabidopsis proteome database. Compared to the number of annotated genes in each GO functional class in the Arabidopsis genome and CG16, GH_TMO ESTs showed a significant increase (P≤0.01, χ2-test) in the percentage of predicted genes in the classes of transcription factor activity, DNA or RNA binding, nucleic acid binding, and nucleotide binding (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Gene Ontology (GO) molecular functional classifications of GH_TMO, CGI6, CGI7, and the Arabidopsis proteome. The GO functional class was assigned to cotton unique sequences using Arabidopsis GO SLIM (ftp://ftp.arabidopsis.org/home/tair/Ontologies/Gene_Ontology/ATH_GO_GOSLIM.20050723.txt). Arrows indicate the GO functional classes that contained ESTs that were significantly overrepresented in the GH_TMO library using χ2-tests.

Enrichment of transcription factors in the GH_TMO ESTs

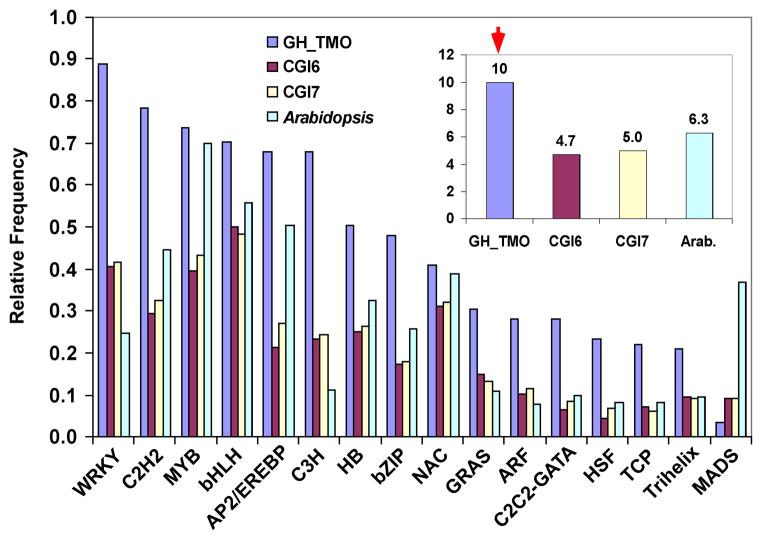

To determine relative abundance of putative transcription factors in the cotton EST collection, we compared 1,827 protein sequences consisting of 56 transcription factor families from the Arabidopsis transcription factor database (http://datf.cbi.pku.edu.cn/index.php) with the cotton EST sequences using TBLASTN (E ≤ -10). Notably, the frequency of putative transcription factors in the GH_TMO library (~10%) was significantly higher than those in CGI6 (~4.7%), CGI7 (~5.0 %), and the Arabidopsis proteome (~6.3%) (P≤0.01; χ2-test) (Figure 2), a result consistent with the GO functional classification data described above.

Figure 2.

Relative frequencies of 16 putative transcription factor families present in GH_TMO, CGI6, CGI7, and the Arabidopsis proteome. Inset box shows percentage of all putative transcription factors present in GH_TMO, CGI6, CGI7, and the Arabidopsis (Arab.) proteome, respectively. Arrow indicates 10% of putative transcription factors present in the GH_TMO library.

Among the putative transcription factor sequences identified in CGI7 (Supplementary Table 2), GH_TMO ESTs contained a total of 251 unique sequences, including 94 TCs and 157 singletons. Almost every putative transcription factor family (with an exception of MADS) was overrepresented in the GH_TMO library (Figure 2). Many ESTs encoding putative transcription factors including MYB, WRKY, AP2/EREBP, C2H2, and bHLH families were exclusively present in the GH_TMO library.

CGI7 contained a total of 242 putative MYB-coding sequences, 21 of which (~8.7%) are specific to the GH_TMO library (Supplementary Table 2). The cotton MYB-like genes are distributed among various clades and subgroups in the neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree, and some are located in the clades specific to cotton (Figure 3). Several putative cotton MYB orthologs matched PhMYB1 (Z13996) and AmMIXTA (X79108) that play a role in leaf trichome development (Noda et al., 1994; Perez-Rodriguez et al., 2005). A total of 197 unique sequences encoding putative WRKY factors were identified in CGI7, 32 of which (~16%) were present only in the GH_TMO library.

Figure 3.

A phylogenetic tree indicating relationships of 21 GH_TMO-specific unique sequences encoding putative MYB factors and 24 genes encoding putative MYB factors in other plant species. TCs and singletons (DTs) were based on CGI7 (Supplementary Data 3). Sequences other than those for the Arabidopsis MYB genes are shown with the gene name and GenBank accession number. Subgroups are designated according to the previously described method (Kranz et al., 1998).

To determine relative enrichment of ESTs in different tissues, we analyzed EST data generated in five EST libraries using R-statistics (Stekel et al., 2000) with a P-value of 0.001 (Supplementary Table 1). The libraries were derived from GH_TMO: G. hirsutum TM-1 ovules, GH_BNL: G. hirsutum six-day cotton fibers, GA_Ea: G. arboreum developing fibers (7–10 DPA), GR_Ea: G. raimondii whole seedlings with the first true leaves, and GR_Eb: G. raimondii bolls (-3 DPA flower buds to +3 DPA bolls). A total of 648 genes showed differential representation in the five libraries. Using hierarchical cluster analysis (Eisen et al., 1998), we found that many differentially enriched genes were library-specific (Figure 4), suggesting a relative enrichment of these genes in different tissues. Notably, ESTs related to several clusters of transcription factors were more abundant in the GH_TMO library, but not in other libraries. In addition to MYBs, ESTs encoding many other putative transcription factors, including MADS, C2H2, C3H, bHLH and WRKY, were highly represented in the GH_TMO library (Figure 4a).

Figure 4.

Hierarchical cluster analyses for cotton ESTs encoding putative transcription factors (a) and phytohormone-related proteins (b) that were differentially expressed in five cotton EST libraries derived from tissues in different developmental stages using the method of Stekel et al. (2000) and a P-value of 0.001. The frequencies of ESTs from each library in each TC were represented by increasing intensities of red (black represented a frequency of zero). Gene identities in the parentheses correspond to transcription factor gene families in Arabidopsis (a) and homologous phytohormonal regulators in Arabidopsis and other species (b), respectively. The libraries were made from GH_TMO, G. hirsutum TM-1 ovule; GH_BNL, G. hirsutum six-day cotton fibers; GA_Ea, G. arboreum developing fibers (7–10 DPA); GR_Ea, G. raimondii whole seedlings with the first true leaves; and GR_Eb, G. raimondii flower buds and bolls (buds -3 DPA to +3 DPA).

Using quantitative RT-PCR analysis, we confirmed transcript abundance of selected ESTs encoding transcription factors in ovules at early stages of fiber development (-3 to +3 DPA) (Figure 5). DT559244 and TC67212 are putative cotton orthologs of AmMIXTA/AmMYBML1. The expression of these two genes was rapidly induced at 0 to +3 DPA and declined at 5 DPA (Figure 5a and 5b). DT556361, a putative cotton ortholog of AtGL2, was expressed at high levels in fiber-bearing ovules but at significantly reduced levels in non-fiber tissues (Figure 5c). DT553497, a putative cotton ortholog of CpMYB5, was highly expressed at -3 and 0 DPA but dramatically down-regulated after +3 DPA (Figure 5d). Interestingly, the expression of all four genes was significantly down-regulated in the N1N1 mutant compared to TM-1. The N1N1 mutation leads to a naked seed phenotype due to delayed fiber initiation, decreased number of fiber initials, a reduced rate of fiber elongation, and the absence of long lint fibers (Endrizzi et al., 1984; Lee et al., 2006).

Figure 5.

Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) analyses of selected genes encoding putative GH_TMO-specific transcription factors and phytohormonal regulators. (a) DT559244, a putative AmMIXTA homolog. (b) TC67212, a putative AmMIXTA homolog. (c) DT556361, an AtGL2 homolog. (d) DT553497, a putative CpMYB5 homolog. (e) TC77097, a brassinosteroid (BR) receptor 1-like gene (BRI1). (f) TC65017, a BR signaling positive regulator-like gene (BES1). (g) TC66418, an ethylene response factor 1-like gene (ERF1). (h) TC69611, an auxin signaling-related gene (TIR1), (i) TC76794, an auxin-response factor 1-like gene (ARF1). (j) DT565265, an ARF8-like gene. (k) TC64087, an ARF12-like gene. (l) TC70523, a GA negative regulator (GAI)-related gene. TM-1: Texas Marker-1 (wild type); N1: N1N1 fiberless mutant; -3: 3 days before anthesis; 0: the day of anthesis; +3: 3 days post anthesis (DPA); +5: 5 DPA; L: leaves; and P: petals.

Enrichment of phytohormonal regulators in the GH_TMO ESTs

To test the role of hormonal signaling in early stages of ovule and fiber development, we analyzed cotton EST sequences using TBLASTN (E≤-10) against the amino acid sequences of Arabidopsis gene families involved in phytohormone biosynthesis and signal transduction pathways. We identified 230 putative ABA-, BR-, GA-, ethylene-, and auxin-related sequences in the GH_TMO library (Figure 4b and Supplementary Table 3). Moreover, the hierarchical cluster analysis indicated that several subsets of putative phytohormonal-pathway genes were differentially enriched in five cotton-EST libraries, many of which accumulated only in ovules from -3 to +3 DPA (Figure 4b). The GH_TMO library was enriched with the ESTs encoding putative cotton BR-associated genes in the biosynthetic (SMT1, SMT2s, and BR6OX) and signaling (BRI1s, BAK1s, BES1s, and CPD) pathways (Figure 4b and Supplementary Table 3). Two putative cotton BES1 orthologs, a positive regulator in the downstream BR signaling pathway (Yin et al., 2002), were present only in the GH_TMO library, suggesting a role for BR in fiber cell differentiation. Calcium-dependant protein kinases (CDPKs) are implicated in GA- and BR-signaling in rice (Abo-el-Saad and Wu, 1995; Yang and Komatsu, 2000). Several CDPKs (DT569356, TC64112, DT572262, TC74526, and TC63968) were found in the GH_TMO library, whereas others (TC66333 and TC66335) were present in the cDNA libraries derived from elongating fibers (GH_BNL and GA_Ea).

Many GH_TMO ESTs encode putative regulators in the GA biosynthetic (GA20OX, GA2OX, POTH1, and KO) and signaling (GAI, RGL2, RGL1, DDF1, PHOR1, RSG, PKL, GL1, GAMYB, AGAMOUS, and LUE1) pathways (Figure 4b and Supplementary Table 3). For example, putative cotton homologs of POTH1 (Hedden and Kamiya, 1997) and GA2-oxidase gene (Rosin et al., 2003) were present only in the GH_TMO library. The GH_TMO library contained seven putative DELLA-like genes (four RGL2s, two GAIs, and one RGL1), six putative homologues of ubiquitin E3 ligases (PHOR1s), and several GA-responsive genes including GL1, GAMYB, AGAMOUS, and LUE1. Moreover, ESTs encoding putative cotton homologues in the auxin biosynthetic (YUCCAs, CYP83B1s, and NIT2), signaling (ARFs, AUX1, TIR1, and PIN1), and transport (AUX1 and PIN1) pathways (Weijers and Jurgens, 2005; Woodward and Bartel, 2005) were enriched in the GH_TMO library (Figure 5b and Supplementary Table 3).

In addition to the enrichment of positive phytohormonal regulators, putative negative modulators such as IAA26, PKS3, ROP2, ROP6, ABI1 and ABI2 in the auxin and ABA response pathways were also enriched in the libraries constructed from young ovules (GH_GH_TMO) or elongating fibers (GH_BNL and GA_Ea) (Figure 4b and Supplementary Table 3).

Quantitative RT-PCR analysis confirmed transcript abundance of selected ESTs encoding putative phytohormonal regulators in ovules at early stages of fiber development (-3 to +3 DPA) (Figure 5e–l). A subset of eight genes encoding putative phytohormonal regulators was up-regulated in the immature and fiber-bearing ovules but down-regulated in leaves and petals and in the N1N1 naked seed mutant. These genes encode a putative BR receptor, BRI1 (TC77907), a BR positive regulator, BES1 (TC65017), an auxin receptor, TIR1 (TC69611), three auxin response factors, ARF1 (TC76794), ARF8 (DT565265) and ARF12 (TC64087), an ethylene response factor (ERF1, TC66418), and a negative regulator of GA (GAI, TC70523). It is notable that all eight phytohormonal-related genes were expressed at least one stage earlier than three of four MYB-related genes with an exception of DT553497 (Figure 5). Moreover, the expression of phytohormonal-related genes declined at a later stage (5 DPA).

Enrichment of genome-specific transcripts in the GH_TMO ESTs

The cultivated allotetraploid cotton species, G. hirsutum L. and G. barbadense L. (AADD), were formed by allopolyploidization between two diploid cotton species, G. arboreum L. (or G. herbaceum L.) (AA) and G. raimondii Ulbrich (DD) (Beasley, 1940; Wendel and Cronn, 2003). Notably, the AA genome donor produces long lint fibers, whereas the DD genome donor produces very few short fibers, suggesting a role for genome-specific gene expression in fiber cell development.

To determine transcript origin in G. hirsutum L, we analyzed TCs in CGI7 with at least 5 ESTs for the presence of GSP. A total of 32,229 GSPs were identified (Supplementary Table 4); ~64% of the GSPs were transitions (A/G and T/C) and ~36% transversions (G/T, A/C, C/G, and A/T). Among the GSPs identified, 10,066 GSPs (~31%) were consistently linked (100% out of > 5 ESTs examined) to the AA or DD genotype in all AA, DD, and AADD ESTs within each TC (Figure 6a and Supplementary Table 5). The numbers of ESTs derived from the AA or DD genomes were equally distributed in the CGI7 assembly. In contrast, many transcripts present in TM-1 allotetraploid cotton were derived from only one diploid genotype (Figure 6a and Supplementary Table 6). Among 2,605 TCs examined, 2,233 TCs were derived exclusively from the AA subgenome and 372 TCs from the DD subgenome. For example, TC67135, a putative cotton cyclin D3, contained 3 ESTs with a “T” and 3 ESTs with a “C” at position 638 in AA and DD genome cotton, respectively (Figure 6b). Allotetraploid (AADD) cotton contained 10 ESTs with the “T” and 1 EST with the “C” at the same position, suggesting preferential expression of this gene from the AA subgenome in TM-1. TC66418, a putative cotton ERF1, a gene involved in ethylene signaling, had 2 ESTs with a “A” and 16 ESTs with a “G” at position 376 in AA and DD genome cotton, respectively. In allotetraploid (AADD) cotton, all 50 ESTs for the putative ERF1 were derived from the AA subgenome because there was an “A” at position 376 (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Genome-specific gene regulation in cotton allotetraploids. (a) A scatter plot representing the AA- vs. DD- transcript ratio among allotetraploid cotton ESTs that contained AA- or DD-specific GSPs. For each TC, the log2(AA/DD) value was plotted against the log2(AA+DD) value. The AADD-transcripts that were preferentially accumulated with AA- or DD-origins are located above or below, respectively, the zero horizontal line. AA/DD, the number of AA-ESTs divided by that of DD-ESTs in AADD-cotton in each TC and AA+DD, the sum of AA-ESTs and DD-ESTs in AADD-cotton in each TC. (b) An example of AA-, DD-EST (TC67135 encoding putative cotton cyclin D) distributions in G. arboreum (AA), G. ranmondii, and G. hirsutum (AADD). A T/C GSP was detected between AA and DD-ESTs. An equal number of ESTs were present in AA- and DD-genotypes, whereas nine of ten ESTs in the AADD-genotype were AA-specific (boxed). (c) SSCP analysis confirmed genotype-specific expression patterns of TC67135 (cyclin D). Lanes 1–10 indicate PCR products amplified from genomic DNA of AA (lane 1), DD (2), and AADD (3), cDNAs from ovules harvested at -3 DPA (4), 0 DPA (5). +3 DPA (6), +5 DPA (7), and +7 DPA (8), leaves (9), and petals (10), all from AADD genotype. Note that the transcripts were AA-specific and expressed at high levels in immature and fiber-bearing ovules. (d) GO functional classifications of ESTs derived from AA and DD subgenomes. The frequency of AA subgenome ESTs (purple) is significantly higher than that of DD subgenome ESTs (yellow). The total number of ESTs is shown in blue column.

We confirmed the preferential expression patterns of a few genes using SSCP analysis (TC67135, Figure 6c). The differentially accumulated transcripts in the AA subgenome in cotton allopolyploids included the ESTs encoding putative transcription factors such as MYB, WRKY, and bZIP families and regulators involved in phytohormone signal transduction pathways. Furthermore, AA subgenome transcripts were significantly overrepresented in every molecular function class (Figure 6d). Thus, our data documented sequential activation (Lee et al., 2006) of genome-wide AA subgenome-specific transcriptional and phytohormonal genes involved in biological processes important for early stages of fiber cell development.

Discussion

Polyploidy effects of gene regulation in cotton allotetraploids

Results from ovular EST analysis indicate preferential accumulation of AA subgenome ESTs encoding putative transcription factors and phytohormonal regulators in the cotton allotetraploids containing AADD genomes. The AA genome species produce both fuzz and long lint fibers, whereas the DD genome species produce very short lint fibers (Applequist et al., 2001), although the DD genome contributes to other agronomic traits. The data suggest that the expression of genes from the fiber-bearing AA genome donor contributes to early stages of fiber and seed development. Alternatively, the DD subgenome may contain trans-activating factors that stimulate the expression of genes in the AA subgenome. Using computational, RT-PCR, and SSCP analyses, we identified and verified progenitor-dependent (or genome-specific) gene regulation in allotetraploid cotton (Figure 6), which is reminiscent of genome-wide transcriptome dominance (A. arenosa over A. thaliana) discovered in Arabidopsis allotetraploids (Wang et al., 2006). Therefore, genome-specific gene regulation may be a general consequence of polyploidization in Arabidopsis and cotton allopolyploids and presumably in many other allopolyploid plants.

Duplicate genes in cotton allopolyploids may diverge their expression via tissue-specific regulation or subfunctionalization (Adams et al., 2003; Adams et al., 2004). Among 40 genes examined in G. hirsutum ovules, ten displayed silencing or unequal expression of homoeologous loci. Although silencing is reciprocal and developmentally regulated, there is no bias towards either the AA or DD subgenome. This is probably because many genes reported in that study are randomly selected and examined in non-fiber tissues. It is likely that genome-dependent transcript accumulation is specific to a particular developmental stage (e.g., fiber cell initiation). Indeed, the genes encoding putative MYB transcription factors and phytohormonal regulators in ovules were expressed at high levels in the early stages but their expression levels declined in later stages of fiber development (Figure 5). Accumulation of AA genome-specific transcripts in the allotetraploid cotton may facilitate fiber-specific gene regulation that has been selected after polyploidization and during domestication of cotton allotetraploids. The data also suggest a mechanism for how cultivated cotton has a fiber cell phenotype that is similar to the AA genome progenitor. The low expression levels of the genes encoding putative transcription factors and phytohormonal regulators in the N1N1 mutant (Figure 5) suggest that these genes contribute to the development of long lint fibers that are significantly reduced in number in the N1N1 mutant.

A previous study indicated that the majority of fiber QTLs are located in the DD subgenome (Jiang et al., 1998) probably because some genes associated with fiber development are suppressed in the DD genome diploid but de-repressed after combining the AA and DD subgenomes in the allotetraploids. The combination of AA and DD homoeologous genomes stimulates production of superior fibers compared to the AA genome donor. Fiberless mutations in the G. hirsutum allotetraploid are thought to be located in similar positions relative to the centromeres of AA and DD homoeologous chromosomes in the allotetraploid (Samora et al., 1994), suggesting that novel gene expression is activated after combining homoeologous chromosomes. The expression of genes in the AA subgenome is enhanced because of interactions between the homoeologous chromosomes, a finding in agreement with the many QTLs identified in the AA subgenome (Frelichowski et al., 2006; Lacape et al., 2005; Mei et al., 2004; Ulloa et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2003).

Upregulation of transcription factors during early stages of fiber and ovule development

Compared to other libraries, GH_TMO ESTs represent >15% of the TCs and singletons in CGI7 and contain ~4.8% fiber- and ovule-specific transcripts. Note that the GH_TMO ESTs contain different profiles of ESTs encoding putative transcription factors and phytohromonal regulators than those derived from ovules at 5–10 DPA (Shi et al., 2006). The genes encoding these ESTs may play important roles in the differentiation of fiber cell initials in the protodermal layer of immature ovules. For example, GhPDF1, a gene encoding a putative protodermal factor 1 in cotton, is highly expressed in immature ovules (-3 DPA) and in fiber-bearing ovules (+5 DPA) (Table 1) (Lee et al., 2006). In Arabidopsis, PDF1 is specifically expressed in the L1 layer of vegetative and floral meristems, in organ primordia, and in protodermal cells during embryogenesis, suggesting a role in cell fate determination (Abe et al., 2001).

We found that almost every category of transcription factor is over-represented in the GH_TMO ESTs that were generated from tissues undergoing rapid cellular and developmental transitions during early seed development and fiber cell initiation. Among them, GL1, a R2R3-MYB transcription factor, plays a role in leaf trichome differentiation in Arabidopsis (Glover, 2000; Hülskamp, 2004; Ramsay and Glover, 2005). AtGL2 (At1g79840) is a homeodomain leucine-zipper protein and activates downstream trichome-specific differentiation genes during leaf trichome development in Arabidopsis (Rerie et al., 1994). The role of cotton MYB transcription factors in cotton fiber development has also been documented (Loguercio et al., 1999; Suo et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2004). Over-expressing GaMYB2 complements the gl1 mutant phenotype and promotes the development of a single seed trichome in Arabidopsis (Wang et al., 2004). GhMYB25 is expressed in fiber cell initials (Wu et al., 2006).

We confirmed that four genes encoding three putative MYB transcription factors (AmMIXTA and CpMYB5) and a putative homeodomain leucine-zipper protein (GL2) were expressed at high levels during early stages (-3 to +5 DPA) of fiber development, and all of them were repressed in the N1N1 mutant. AtGL2 is involved in trichome cell patterning in Arabidopsis leaves (Glover, 2000; Hülskamp, 2004; Ramsay and Glover, 2005), and AmMIXTAs control trichome differentiation in Antirrhinum petals (Noda et al., 1994; Perez-Rodriguez et al., 2005). Notably, several putative cotton MYBs form their own clades (Figure 3), many of which are present only in the GH_TMO library (Figure 4a). Enrichment of these putative MYB factors supports their roles in fiber cell differentiation and seed development.

TTG2/AtWRKY44 (TRANSPARENT TESTA GLABRA2), the first WRKY gene to be functionally characterized, controls trichome development in leaves and production of mucilage and tannin in Arabidopsis seed coats (Johnson et al., 2002). The trichomes in the ttg2 mutants are unbranched and reduced in number compared to the wild type. WRKY transcription factors were in the most abundant transcription factor family in CGI7. The WRKY families participate in various hormonal signaling pathways (Ülker and Somssich, 2004). Some WRKYs are positive regulators of the abscisic acid (ABA) signaling pathway, whereas others such as those in rice aleurone cells are negative regulators of the GA pathway (Xie et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2004). The data may suggest cross-interactions between transcriptional and phytohormonal regulation during fiber cell development.

The role of phytohormone regulators in early stages of fiber development

Fibers can be induced from the protodermal cells of unfertilized ovules by the addition of auxin and gibberellic acid (GA) (Beasley and Ting, 1974; Gialvalis and Seagull, 2001; Kim and Triplett, 2001). Either hormone promotes fiber initiation, and the effect is additive, implying a significant role for the two phytohormones in fiber cell initiation. Moreover, exogenous application of IAA and GA3 to flower buds in planta and unfertilized ovules in vitro resulted in an increased number of fibers (Gialvalis and Seagull, 2001). Brassinosteroid brassinolide (BL) promotes fiber cell elongation as well as fiber cell initiation (Sun et al., 2005).

The GH_TMO library contained seven putative DELLA-like genes (four RGL2s, two GAIs, and one RGL1), six putative homologues of ubiquitin E3 ligases (PHOR1s), and several GA-responsive genes including GL1, GAMYB, AGAMOUS, and LUE1. ESTs encoding putative cotton homologues in the auxin biosynthetic (YUCCAs, CYP83B1s, SIR1, and NIT2), signaling (ARFs, AUX1, TIR1, and PIN1), and transport (AUX1 and PIN1) pathways (Weijers and Jurgens, 2005; Woodward and Bartel, 2005) were enriched in the GH_TMO library (Figure 5b and Supplementary Table 3).

Quantitative RT-PCR results confirmed up-regulation of a DELLA-like gene (GAI, TC70523), an auxin receptor (TC69611), and three auxin responsive-like factors (TC64087, TC76794 and DT565265) in the immature and fiber-bearing ovules (-3 to +5 DPA) compared to non-fiber tissues such as leaves and petals. These genes were significantly down-regulated in the N1N1 naked seed mutant that lacks long lint fibers (Figure 5). Members of the DELLA family repress the GA signaling pathway in the absence of GA and are rapidly degraded by the ubiquitin-26S-proteasome pathway (Fleet and Sun, 2005). Similar to GA, the auxin signal transduction pathway is activated through a de-repression mechanism (Berleth et al., 2004; Weijers and Jurgens, 2005; Woodward and Bartel, 2005). Auxin plays a pivotal role in the establishment of embryonic cell fate along the apical-basal axis during Arabidopsis embryogenesis by localized rearrangement of auxin transporters and responsive factors (Kepinski and Leyser, 2002). Furthermore, cotton genes encoding putative brassinosteroid (BR) receptor 1 (BRI1), BR signaling positive regulator (BES1), and ethylene response factor 1 (ERF1) were up-regulated in the fiber-bearing ovules (Figure 5), suggesting a role of BR signaling and ethylene response genes in fiber cell development (Shi et al., 2006; Sun et al., 2005). Interestingly, all eight phytohormone-related genes examined were induced prior to the activation of MYB-related genes (Figure 5), indicating that phytohormonal pathways potentate transcriptional regulation for cell fate determination. The spatial and temporal regulation of gene expression during fiber cell development is genome-specific, which is reminiscent of long lint fibers produced in AA genome species. The GH_TMO ESTs will be valuable for transcriptome analysis of these genes in the immature ovules and young fibers produced in vitro and in vivo. This will lead us to the understanding of how AA diploid progenitors maintain and promote genome-specific gene expression patterns and how gene regulation between homoeologous AA and DD subgenomes contributes to enhanced fiber morphology in the cultivated cotton allopolyploids.

Acknowledgments

We thank Andrew Woodward for critical suggestions on improving the manuscript. This work is supported by a grant from the National Science Foundation Plant Genome Research Program (DBI0624077). Work in the Chen laboratory is supported in part by the Cotton Incorporated (04-5555) and the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board Advanced Technology Program (000517-0218-2001).

Footnotes

The stages of ovule development are referenced relative to anthesis, also called 0 day post-anthesis. The number of days pre-anthesis is designated with a negative value and the number of days post-anthesis is designated as a positive value.

References

- Abe M, Takahashi T, Komeda Y. Identification of a cis-regulatory element for L1 layer-specific gene expression, which is targeted by an L1-specific homeodomain protein. Plant J. 2001;26:487–494. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2001.01047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abo-el-Saad M, Wu R. A rice membrane calcium-dependent protein kinase is induced by gibberellin. Plant Physiol. 1995;108:787–793. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.2.787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams KL, Cronn R, Percifield R, Wendel JF. Genes duplicated by polyploidy show unequal contributions to the transcriptome and organ-specific reciprocal silencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:4649–4654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0630618100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams KL, Percifield R, Wendel JF. Organ-specific silencing of duplicated genes in a newly synthesized cotton allotetraploid. Genetics. 2004;168:2217–2226. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.033522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Applequist WL, Cronn R, Wendel JF. Comparative development of fiber in wild and cultivated cotton. Evol Dev. 2001;3:3–17. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-142x.2001.00079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arpat AB, Waugh M, Sullivan JP, Gonzales M, Frisch D, Main D, Wood T, Leslie A, Wing RA, Wilkins TA. Functional genomics of cell elongation in developing cotton fibers. Plant Mol Biol. 2004;54:911–929. doi: 10.1007/s11103-004-0392-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basra A, Malik CP. Development of the cotton fiber. Int Rev Cytol. 1984;89:65–113. [Google Scholar]

- Beasley CA, Ting IP. The effects of plant growth substances on in vitro fiber development from unfertilized cotton ovules. Amer J Bot. 1974;61:188–194. [Google Scholar]

- Beasley JO. The origin of American tetraploid Gossypium species. Amer Naturalist. 1940;74:285–286. [Google Scholar]

- Berleth T, Krogan NT, Scarpella E. Auxin signals--turning genes on and turning cells around. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2004;7:553–563. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2004.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardle L, Ramsay L, Milbourne D, Macaulay M, Marshall D, Waugh R. Computational and experimental characterization of physically clustered simple sequence repeats in plants. Genetics. 2000;156:847–854. doi: 10.1093/genetics/156.2.847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang S, Puryear J, Cairney J. A simple and efficient method for isolating RNA from pine trees. Plant Mol Biol Reporter. 1993;11:113–116. [Google Scholar]

- Chou HH, Holmes MH. DNA sequence quality trimming and vector removal. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:1093–1104. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.12.1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delmer DP, Pear J, Andrawis A, Stalker D. Genes encoding small GTP-binding proteins analogous to mammalian RAC are preferentially expressed in developing cotton fibers. Mol Gen Genet. 1995;248:43–51. doi: 10.1007/BF02456612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen MB, Spellman PT, Brown PO, Botstein D. Cluster analysis and display of genome-wide expression patterns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:14863–14868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endrizzi JE, Turcotte EL, Kohel RJ. Qualitative genetics, cytology and cytogenetics. In: Kohel RJ, Lewis DF, editors. Agronomy: Cotton. Madison, WI: American Society of Agronomy, Inc; 1984. pp. 59–80. [Google Scholar]

- Fleet CM, Sun TP. A DELLAcate balance: the role of gibberellin in plant morphogenesis. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2005;8:77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2004.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frelichowski JE, Jr, Palmer MB, Main D, Tomkins JP, Cantrell RG, Stelly DM, Yu J, Kohel RJ, Ulloa M. Cotton genome mapping with new microsatellites from Acala ‘Maxxa’ BAC-ends. Mol Genet Genomics. 2006 doi: 10.1007/s00438-006-0106-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gialvalis S, Seagull RW. Plant hormones alter fiber initiation in unfertilized cultured ovules of Gossypium hirsutum. J Cotton Sci. 2001;5:252–258. [Google Scholar]

- Glover BJ. Differentiation in plant epidermal cells. J Exp Bot. 2000;51:497–505. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/51.344.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haigler CH, Zhang DH, Wilkerson CG. Biotechnological improvement of cotton fibre maturity. Physiologia Plantarum. 2005;124:285–294. [Google Scholar]

- Hedden P, Kamiya Y. GIBBERELLIN BIOSYNTHESIS: Enzymes, Genes and Their Regulation. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1997;48:431–460. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.48.1.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphries JA, Walker AR, Timmis JN, Orford SJ. Two WD-repeat genes from cotton are functional homologues of the Arabidopsis thaliana TRANSPARENT TESTA GLABRA1 (TTG1) gene. Plant Mol Biol. 2005;57:67–81. doi: 10.1007/s11103-004-6768-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hülskamp M. Plant trichomes: a model for cell differentiation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:471–480. doi: 10.1038/nrm1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji SJ, Lu YC, Feng JX, Wei G, Li J, Shi YH, Fu Q, Liu D, Luo JC, Zhu YX. Isolation and analyses of gene preferentially expressed during early cotton fiber development by subtractive PCR and cDNA array. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:2534–2543. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang C, Wright RJ, El-Zik KM, Paterson AH. Polyploid formation created unique avenues for response to selection in Gossypium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:4419–4424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John ME, Crow LJ. Gene expression in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) fiber: cloning of the mRNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:5769–5773. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.13.5769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John ME, Keller G. Characterization of mRNA for a proline-rich protein of cotton fiber. Plant Physiol. 1995;108:669–676. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.2.669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson CS, Kolevski B, Smyth DR. TRANSPARENT TESTA GLABRA2, a trichome and seed coat development gene of Arabidopsis, encodes a WRKY transcription factor. Plant Cell. 2002;14:1359–1375. doi: 10.1105/tpc.001404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kepinski S, Leyser O. Ubiquitination and auxin signaling: a degrading story. Plant Cell. 2002;14(Suppl):S81–95. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HJ, Triplett BA. Cotton fiber growth in planta and in vitro. Models for plant cell elongation and cell wall biogenesis. Plant Physiol. 2001;127:1361–1366. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HJ, Triplett BA. Cotton fiber germin-like protein. I. Molecular cloning and gene expression. Planta. 2004;218:516–524. doi: 10.1007/s00425-003-1133-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranz HD, Denekamp M, Greco R, Jin H, Leyva A, Meissner RC, Petroni K, Urzainqui A, Bevan M, Martin C, Smeekens S, Tonelli C, Paz-Ares J, Weisshaar B. Towards functional characterisation of the members of the R2R3-MYB gene family from Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1998;16:263–276. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhl JC, Cheung F, Yuan Q, Martin W, Zewdie Y, McCallum J, Catanach A, Rutherford P, Sink KC, Jenderek M, Prince JP, Town CD, Havey MJ. A unique set of 11,008 onion expressed sequence tags reveals expressed sequence and genomic differences between the monocot orders Asparagales and Poales. Plant Cell. 2004;16:114–125. doi: 10.1105/tpc.017202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Tamura K, Nei M. MEGA3: Integrated software for Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis and sequence alignment. Brief Bioinform. 2004;5:150–163. doi: 10.1093/bib/5.2.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacape JM, Nguyen TB, Courtois B, Belot JL, Giband M, Gourlot JP, Gawryziak G, Roques S, Hau B. QTL analysis of cotton fiber quality using multiple Gossypium hirsutum x Gossypium barbadense backcross generations. Crop Science. 2005;45:123–140. [Google Scholar]

- Lee JJ, Hassan OSS, Gao W, Wang J, Wei EN, Russel JK, Chen XY, Payton P, Sze SH, Stelly DM, Chen ZJ. Developmental and gene expression analyses of a cotton naked seed mutant. Planta. 2006;223:418–432. doi: 10.1007/s00425-005-0098-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li CH, Zhu YQ, Meng YL, Wang JW, Xu KX, Zhang TZ, Chen XY. Isolation of genes preferentially expressed in cotton fibers by cDNA filter arrays and RT-PCR. Plant Sci. 2002;163:1113–1120. [Google Scholar]

- Loguercio LL, Zhang JQ, Wilkins TA. Differential regulation of six novel MYB-domian genes defines two distinct expression patterns in allotetraploid cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) Mol Gen Genet. 1999;261:660–671. doi: 10.1007/s004380050009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma DP, Liu HC, Tan H, Creech RG, Jenkins JN, Chang YF. Cloning and characterization of a cotton lipid transfer protein gene specifically expressed in fiber cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1344:111–114. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2760(96)00166-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mei M, Syed NH, Gao W, Thaxton PM, Smith CW, Stelly DM, Chen ZJ. Genetic mapping and QTL analysis of fiber-related traits in cotton (Gossypium) Theor Appl Genet. 2004;108:280–291. doi: 10.1007/s00122-003-1433-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noda K, Glover BJ, Linstead P, Martin C. Flower colour intensity depends on specialized cell shape controlled by a Myb-related transcription factor. Nature. 1994;369:661–664. doi: 10.1038/369661a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orford SJ, Timmis JM. Abundant mRNAs specific to the developing cotton fibre. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 1997;94:909–918. [Google Scholar]

- Percival AE, Wendel JF, Stewart JM. Taxonomy and germplasm resources. In: Smith CW, Cothren JT, editors. Cotton: Origin, History, Technology, and Production. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 1999. pp. 33–63. [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Rodriguez M, Jaffe FW, Butelli E, Glover BJ, Martin C. Development of three different cell types is associated with the activity of a specific MYB transcription factor in the ventral petal of Antirrhinum majus flowers. Development. 2005;132:359–370. doi: 10.1242/dev.01584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pertea G, Huang X, Liang F, Antonescu V, Sultana R, Karamycheva S, Lee Y, White J, Cheung F, Parvizi B, Tsai J, Quackenbush J. TIGR Gene Indices clustering tools (TGICL): a software system for fast clustering of large EST datasets. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:651–652. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quackenbush J. Computational analysis of microarray data. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2:418–427. doi: 10.1038/35076576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay NA, Glover BJ. MYB-bHLH-WD40 protein complex and the evolution of cellular diversity. Trends Plant Sci. 2005;10:63–70. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2004.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhart JA, Petersen MW, John ME. Tissue-specific and developmental regulation of cotton gene fbl2a: Demonstration of promoter activity in transgenic plants. Plant Physiol. 1996;112:1331–1341. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.3.1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rerie WG, Feldmann KA, Marks MD. The GLABRA2 gene encodes a homeo domain protein required for normal trichome development in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1388–1399. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.12.1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romualdi C, Bortoluzzi S, D’Alessi F, Danieli GA. IDEG6: a web tool for detection of differentially expressed genes in multiple tag sampling experiments. Physiol Genomics. 2003;12:159–162. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00096.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romualdi C, Bortoluzzi S, Danieli GA. Detecting differentially expressed genes in multiple tag sampling experiments: comparative evaluation of statistical tests. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:2133–2141. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.19.2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosin FM, Hart JK, Horner HT, Davies PJ, Hannapel DJ. Overexpression of a knotted-like homeobox gene of potato alters vegetative development by decreasing gibberellin accumulation. Plant Physiol. 2003;132:106–117. doi: 10.1104/pp.102.015560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samora PJ, Stelly DM, Kohel RJ. Localization and mapping of the Le1 and Gl2 of cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) J Hered. 1994;85:152–157. [Google Scholar]

- Shi YH, Zhu SW, Mao XZ, Feng JX, Qin YM, Zhang L, Cheng J, Wei LP, Wang ZY, Zhu YX. Transcriptome profiling, molecular biological, and physiological studies reveal a major role for ethylene in cotton fiber cell elongation. Plant Cell. 2006;18:651–664. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.040303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smart LB, Vojdani F, Maeshima M, Wilkins TA. Genes involved in osmoregulation during turgor-driven cell expansion of developing cotton fibers are differentially regulated. Plant Physiol. 1998;116:1539–1549. doi: 10.1104/pp.116.4.1539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stekel DJ, Git Y, Falciani F. The comparison of gene expression from multiple cDNA libraries. Genome Res. 2000;10:2055–2061. doi: 10.1101/gr.gr-1325rr. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Veerabomma S, Abdel-Mageed HA, Fokar M, Asami T, Yoshida S, Allen RD. Brassinosteroid regulates fiber development on cultured cotton ovules. Plant Cell Physiol. 2005;46:1384–1391. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pci150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suo J, Liang X, Pu L, Zhang Y, Xue Y. Identification of GhMYB109 encoding a R2R3 MYB transcription factor that expressed specifically in fiber initials and elongating fibers of cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1630:25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.bbaexp.2003.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiel T, Michalek W, Varshney RK, Graner A. Exploiting EST databases for the development and characterization of gene-derived SSR-markers in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2003;106:411–422. doi: 10.1007/s00122-002-1031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari SC, Wilkins TA. Cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) seed trichomes expand via diffuse growing mechanism. Can J Bot. 1995;73:746–757. [Google Scholar]

- Udall JA, Swanson JM, Haller K, Rapp RA, Sparks ME, Hatfield J, Yu Y, Wu Y, Dowd C, Arpat AB, Sickler BA, Wilkins TA, Guo JY, Chen XY, Scheffler J, Taliercio E, Turley R, McFadden H, Payton P, Klueva N, Allen R, Zhang D, Haigler C, Wilkerson C, Suo J, Schulze SR, Pierce ML, Essenberg M, Kim H, Llewellyn DJ, Dennis ES, Kudrna D, Wing R, Paterson AH, Soderlund C, Wendel JF. A global assembly of cotton ESTs. Genome Res. 2006;16:441–450. doi: 10.1101/gr.4602906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulloa M, Saha S, Jenkins JN, Meredith WR, Jr, McCarty JC, Jr, Stelly DM. Chromosomal assignment of RFLP linkage groups harboring important QTLs on an intraspecific cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) Joinmap. J Hered. 2005;96:132–144. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esi020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Tian L, Lee HS, Wei NE, Jiang H, Watson B, Madlung A, Osborn TC, Doerge RW, Comai L, Chen ZJ. Genomewide nonadditive gene regulation in Arabidopsis allotetraploids. Genetics. 2006;172:507–517. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.047894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Wang JW, Yu N, Li CH, Luo B, Gou JY, Wang LJ, Chen XY. Control of plant trichome development by a cotton fiber MYB gene. Plant Cell. 2004;16:2323–2334. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.024844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weijers D, Jurgens G. Auxin and embryo axis formation: the ends in sight? Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2005;8:32–37. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendel JF, Cronn RC. Polyploidy and the evolutionary history of cotton. Advances in Agronomy. 2003;78:139–186. [Google Scholar]

- Wendel JF, Schnabel A, Seelanan T. An unusual ribosomal DNA sequence from Gossypium gossypioides reveals ancient, cryptic, intergenomic introgression. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 1995;4:298–313. doi: 10.1006/mpev.1995.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins Ta, Arpat AB. The cotton fiber transcriptome. Physiologia Plantarum. 2005;124:295–300. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins TA, Jernstedt JA. Chapter 9. Molecular genetics of developing cotton fibers. In: Basra AM, editor. Cotton Fibers. New York: Hawthorne Press; 1999. pp. 231–267. [Google Scholar]

- Woodward AW, Bartel B. Auxin: regulation, action, and interaction. Ann Bot (Lond) 2005;95:707–735. doi: 10.1093/aob/mci083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Machado AC, White RG, Llewellyn DJ, Dennis ES. Expression profiling identifies genes expressed early during lint fibre initiation in cotton. Plant Cell Physiol. 2006;47:107–127. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pci228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Z, Zhang ZL, Zou X, Huang J, Ruas P, Thompson D, Shen QJ. Annotations and functional analyses of the rice WRKY gene superfamily reveal positive and negative regulators of abscisic acid signaling in aleurone cells. Plant Physiol. 2005;137:176–189. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.054312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang G, Komatsu S. Involvement of calcium-dependent protein kinase in rice (Oryza sativa L.) lamina inclination caused by brassinolide. Plant Cell Physiol. 2000;41:1243–1250. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcd050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Y, Wang ZY, Mora-Garcia S, Li J, Yoshida S, Asami T, Chory J. BES1 accumulates in the nucleus in response to brassinosteroids to regulate gene expression and promote stem elongation. Cell. 2002;109:181–191. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00721-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T, Yuan Y, Yu J, Guo W, Kohel RJ. Molecular tagging of a major QTL for fiber strength in Upland cotton and its marker-assisted selection. Theor Appl Genet. 2003;106:262–268. doi: 10.1007/s00122-002-1101-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang ZL, Xie Z, Zou X, Casaretto J, Ho TH, Shen QJ. A rice WRKY gene encodes a transcriptional repressor of the gibberellin signaling pathway in aleurone cells. Plant Physiol. 2004;134:1500–1513. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.034967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ülker B, Somssich IE. WRKY transcription factors: from DNA binding towards biological function. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2004;7:491–498. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2004.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]