Abstract

Colorectal cancer, a type of malignant neoplasm originating from the epithelial cells lining the colon and/or rectum, has been the third most frequent malignancy and one of the leading causes of cancer-related deaths in the US. As a bioflavonoid with high anticancer potential, quercetin (Qu) has been proved to have a prospective applicability in chemotherapy for a series of cancers. However, quercetin is a hydrophobic drug, the poor hydrophilicity of which hinders its clinical usage in cancer therapy. Therefore, a strategy to improve the solubility of quercetin in water and/or enhance the bioavailability is desired. Encapsulating the poorly water-soluble, hydrophobic agents into polymer micelles could facilitate the dissolution of drugs in water. In our study, nanotechnology was employed, and quercetin was encapsulated into the biodegradable nanosized amphiphilic block copolymers of monomethoxy poly(ethylene glycol)–poly(ε-caprolactone) (MPEG–PCL), attempting to present positive evidences that this drug delivery system of polymeric micelles is effective. The quercetin-loaded MPEG–PCL nanomicelles (Qu-M), with a high drug loading of 6.85% and a minor particle size of 34.8 nm, completely dispersed in the water and released quercetin in a prolonged period in vitro and in vivo. At the same time, compared with free quercetin, Qu-M exhibited improved apoptosis induction and cell growth inhibition effects in CT26 cells in vitro. Moreover, the mice subcutaneous CT26 colon cancer model was established to evaluate the therapy efficiency of Qu-M in detail, in which enhanced anti-colon cancer effect was proved in vivo: Qu-M were more efficacious in repressing the growth of colon tumor than free quercetin. In addition, better effects of Qu-M on inducing cell apoptosis, inhibiting tumor angiogenesis, and restraining cell proliferation were observed by immunofluorescence analysis. Our study indicated that Qu-M were a novel nanoagent of quercetin with an enhanced antitumor activity, which could serve as a promising potential candidate for colon cancer chemotherapy.

Keywords: quercetin, nanoformulation, colon cancer, cell apoptosis, angiogenesis

Introduction

Colorectal cancer developing in the large intestine1 has been the third leading cause of cancer-related death paralleling its high incidence in the US, where one-fourth deaths is due to cancer.2 The estimated number of new individuals diagnosed with colorectal tumor, including both men and women, will reach 136,830 in the US in 2014, and 50,310 patients will be killed by this carcinoma,2,3 in part because of the risk factors, which include diet, obesity, sedentariness, lack of physical activity, smoking, alcohol intake, and so forth.4–8 Although the pathogenesis and diagnostic techniques of colon tumor has been best understood,9–11 a considerable percentage of this cancer is advanced carcinoma, typically metastasized and difficult to fully eradicate through surgery, when they are found. Consequently, plenty of chemotherapeutic agents are employed in the therapy of a variety of terminal cancers.

Quercetin, with the scientific name of 3,3′,4′,5,7-pentahydroxyflavone, is a type of widespread natural bioflavonoid compound that originates from multifarious edible fruits, vegetables, seeds, and tea.12 Recent studies have showed that quercetin has multiple pharmacological activities, and its anticancer activity has been extensively investigated in many cancer cell lines, whereby it could induce tumor cell apoptosis, modulate tumor cell proliferation and tumor angiogenesis, and inhibit so many important targets of the signaling pathway.13–21 Nevertheless, the therapeutic efficacy of quercetin is hampered by its low water solubility, and the effect of quercetin on curing colon cancer has been seldom documented. Thus, it is intriguing to explore the antineoplastic effects and mechanisms of quercetin on colon tumor in vitro and in vivo by employing a high-performance delivery system with an efficient solubilization of quercetin in an aqueous solution.

In the interest of unraveling the problem of quercetin as mentioned earlier and providing longer cycle times and tolerable metabolic processes, in this study, we made monomethoxy poly(ethylene glycol)–poly(ε-caprolactone) (MPEG–PCL) nanomicelles carrying quercetin on the basis of previous reports,21,22 and describe its characteristics. The obtained quercetin-loaded MPEG–PCL nanomicelles were tested for antitumor effects on colon cancer in vitro, as well as in vivo. Cytotoxicity profile and apoptosis-inducing property of Qu-M on CT26 cells were analyzed, and the in vivo antiangiogenesis and antiproliferation effects were investigated in the mice subcutaneous CT26 colon cancer model. Moreover, we tested drug release behavior in vitro and analyzed the pharmacokinetics. The results demonstrated that the antitumor properties of quercetin might be significantly enhanced by delivering in an MPEG–PCL nanomicellar system in the CT26 tumor model, indicating a promising potential application of Qu-M in colorectal tumor chemotherapy.

Materials and methods

Materials

Quercetin, Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM), and 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)2,5-diphenyltetrazo-lium bromide (MTT) were provided by Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co (St Louis, MO, USA). Acetone, ethanol, methanol, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), methylene chloride, and HPLC (high-performance liquid chromatography)-grade acetic acid were obtained from Kelong Chemical Co (Liaoyang, Liaoning, People’s Republic of China). MPEG (Mn=2,000) and ε-caprolactone (ε-CL) were obtained from Sigma-Al-drich Chemical Co. MPEG–PCL (Mn=4,000) was prepared by ring-opening of ε-CL initiated by MPEG, as reported previously by our laboratory. Briefly, a certain amount of ε-CL and MPEG were added into a dry glass ampoule under nitrogen atmosphere. Then, several drops of Sn(Oct)2 was added. The ampoule was kept at 130°C. During polymerization, the system was stirred slowly, and the viscosity increased with time. About 6 hours later, the temperature of the system was rapidly elevated to 180°C under vacuum for another 20 minutes. After cooling to room temperature under nitrogen atmosphere, the MPEG–PCL copolymer was first dissolved in methylene chloride and reprecipitated from the filtrate using excess cold petroleum ether. Then the mixture was filtered and vacuum-dried to constant weight. The purified MPEG–PCL copolymers were kept in air-tight bags in desiccator before use.

Female BALB/c mice aged 6–8 weeks, as well as Sprague Dawley rats weighing 180–200 g, were acquired from the Laboratory Animal Center of Sichuan University (People’s Republic of China). All mice used in our work were approved by the animal care and use committee of the institute and were maintained on humane treatment throughout the study.

Self-assembly and characterization of the Qu-M

Qu-M were synthesized through the self-assembly method, as reported previously.23 In brief, a 100 mg mixture of quercetin and MPEG–PCL diblock copolymer at a 7:93 ratio was dissolved in an organic solvent composed of methanol (2 mL) and dichloromethane (DCM; 4 mL), and then the mixed solution was evaporated under reduced pressure on a rotary evaporator at 55°C. Consequently, in this step of evaporation, quercetin dispersed in the MPEG–PCL copolymer as an amorphous matter. Next, physiological saline was poured into the coevaporation product, triggering the self-assembly of quercetin and MPEG–PCL to produce Qu-M with a core–shell structure. Finally, the obtained Qu-M were lyophilized and stored at 4°C. The empty MPEG–PCL nanomicelles were prepared using the same method without quercetin as described above.

The particle size of Qu-M was analyzed using dynamic light scattering (DLS; Zetasizer Nano Series-ZS90, Malvern Instruments, Malvern, UK) at 25°C, as was the zeta potential. Meanwhile, in order to observe the morphology of Qu-M, the samples diluted in distilled water were put on a nitrocellulose-coated copper grid and then air-dried, negatively stained with phosphotungstic acid, and examined under a transmission electron microscope (TEM) (H-6009IV, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan).

High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was employed to determine the drug loading (DL) and encapsulation efficiency (EE) of QU-M. Simply put, 10 mg of lyophilized Qu-M was dissolved in 0.1 mL dichloromethane and diluted with methanol, and then the content of quercetin in the mixed liquor was measured by HPLC. The DL and EE of Qu-M were calculated using the following equations:

| (1) |

| (2) |

In vitro release

To determine the release kinetics of quercetin from the Qu-M in vitro, a dialysis method was used: 0.5 mL of the freshly prepared Qu-M was introduced into a dialysis bag, and then the bag was gently shaken at 37°C in 30 mL of incubation medium, 0.5% Tween-80 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH=7.4), which was replaced with fresh medium at predefined intervals. The amount of quercetin released in the incubation medium was detected by HPLC using 421 nm absorbance.

Pharmacokinetics study

The Sprague Dawley rats were randomly divided into two treated groups: Qu-M and free quercetin (free-Qu). Qu-M and free-Qu were respectively dissolved in the physiological saline and the mixed solution of Tween-80 and dehydrated alcohol with the volume ratio of 1:1. The rats of the Qu-M and free-Qu treatment groups were starved overnight before receiving a dose of 100 mg/kg (quercetin) administered intravenously, following which their eyeballs were removed to collect the blood at different predefined intervals (five mice each time point). Then, the blood specimens were extracted with ethyl acetate to obtain the liquid supernatants, which were then evaporated and analyzed by HPLC after dissolving in methanol.

In vitro cell viability assay

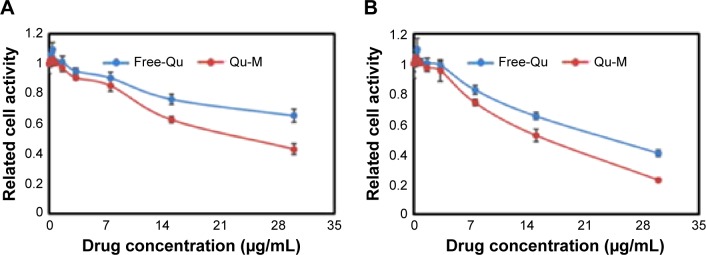

The cytotoxic effects of Qu-M and free-Qu on CT26 cells in vitro were evaluated by the cell viability assay. The CT26 cells at a density of 5×103 per well were seeded onto 96-well culture plates with DMEM for 24 hours. Whereafter, after washing once with DMEM, the cells were coincubated with Qu-M and free-Qu at different concentrations, as shown in Figure 4, for 24 or 48 hours, and then the viability of drug-treated cells was measured using the MTT assay. Briefly, the viable cells could metabolize MTT to formazan salt, with a blue-purple color in DMSO, and the absorbance of the colored solution was quantified using a plate reader (OPTImax, Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) at the wavelength of 570 nm. All results were compared with the untreated cells as 100% survival, and the cell viability was expressed in percentage.

Figure 4.

Cytotoxicity of Qu-M and Free-Qu on CT26 cells in vitro.

Notes: Free-Qu as well as Qu-M could efficiently inhibit the viability of C26 cells in a dose-dependent manner after 24 hours (A) and 48 hours (B). Also, Qu-M could enhance the cytotoxic activity of quercetin on C26 cells in vitro.

Abbreviations: Qu-M, quercetin-loaded MPEG–PCL nanomicelles; free-Qu, free quercetin; MPEG–PCL, monomethoxy poly(ethylene glycol)–poly(ε-caprolactone).

In vitro cell apoptosis assay

To assess the effects of Qu-M and free-Qu on apoptosis of CT26 cells in vitro, flow cytometry (ESP Elite, Beckman-Coulter, Miami, FL, USA) was employed with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled Annexin-V/propidium iodide (PI) double staining assay, following the manufacturer’s instructions. The CT26 cells were incubated with Qu-M, free-Qu, normal saline (NS), and empty MPEG–PCL nano-micelles (EM) for 48 hours. The proportion of Annexin-V-positive cells representing early apoptosis, as well as the percentage of PI-positive cells indicating late apoptosis, were added up to express the apoptosis rates.

In vivo cancer model

In order to establish the animal model of colon cancer, female BALB/c mice aged 6–8 weeks under standard conditions in top filtered cages were employed, consuming a normal diet and acidified water without antibiotics. All the mice were inoculated subcutaneously in the right flank with suspensions of CT26 colon carcinoma cells. The tumor-bearing mice were stochastically divided into four treatment groups (five mice per group): NS group, EM group, and free-Qu and Qu-M groups with a dose of 50 mg/kg (quercetin). When the tumor attained a mean diameter of 6 mm approximately, the mice in each group were administrated accordingly once daily for nine consecutive days via tail vein injection. When the control animals began to die, the mice were sacrificed by cervical spine dislocation, and the tumors of all mice were harvested and examined immediately.

TUNEL assay

The apoptosis-inducing properties of Qu-M and free-Qu in vivo were determined by TUNEL analysis, compared with the NS and EM groups. In general, the tumor tissues harvested from the animal models were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for a minimum of 1 day; then they were immersed in 70% ethanol for 1 night and embedded in paraffin wax. Subsequently, sequential sections were cut by a microtome at a thickness of 3–5 μm and wet-mounted on slides, preparing for the TUNEL assay according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Finally, fluorescence microscopy was employed to analyze the apoptotic cells with green color.

CD31 assay

The immunofluorescence analysis of neovascularization was used to detect the antiangiogenesis activities of Qu-M and free-Qu in the tumor tissues of animal models. Briefly, the tumor tissues obtained from the animal models were frozen immediately and dissected into 3–5 μm sections. Then, after fixation with acetone, the frozen sections were immunostained with the rat anti-mouse CD31 polyclonal antibodies and rhodamine-conjugated secondary antibodies sequentially following the manufacturer’s instructions. The microvessel densities of the tumors were expressed as the microvessel counts, which were quantified by fluorescence microscopy in high-power (×400) microscopic fields.

Ki-67 assay

For the purpose of evaluating the antiproliferation effects of Qu-M and free-Qu in mice models of colon cancer, immunofluorescence technology was employed to determine the cell proliferation by examining Ki-67 protein in the tumor tissues. In brief, the fixed frozen sections of the tumor tissues obtained from the tumor models were incubated with the primary and secondary anti-mouse antibodies Ki-67 polyclonal antibodies and rhodamine-labeled secondary antibodies sequentially in accordance with the manufacturer’s guidelines. Then the Ki-67-positive proliferating cells with green fluorescent nuclei were detected by fluorescence microscopy in high-power (×400) microscopic fields, as described previously, and the results were expressed as percentages of the Ki-67-positive cells and total cells.

Statistical analysis

Where appropriate, all the results were obtained from triplicate experiments performed in a parallel manner, and depicted as the mean ± standard deviation. The tumor volumes and weights of each group were compared by one-way ANOVA (analysis of variance), and the survival curves were estimated according to the Kaplan–Meier method. The levels of P-values for comparison between all groups were determined by 2-tailed Mann–Whitney test, and a probability value of ≤0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed with the statistical software system of SPSS v19.0 for windows (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Synthesis and characterization of the Qu-M

Self-assembly of the Qu-M

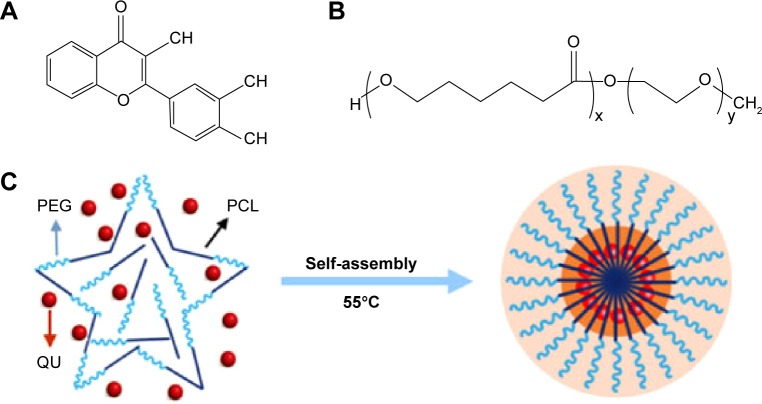

In the interest of improving the solubility of quercetin in water and enhancing the bioavailability, in our study, quercetin was encapsulated into the biodegradable nanosized amphiphilic block copolymers of MPEG–PCL via a self-assembly method mentioned earlier. In brief, quercetin (Figure 1A) and MPEG–PCL (Figure 1B) were codissolved in methanol–dichloromethane mixture for evaporating at 55°C, and in the process of which they began to assemble automatically. As shown in Figure 1C, the product of Qu-M had a core–shell structure, which was composed of a hydrophobic inner core of PCL and a hydrophilic outer shell of PEG, and quercetin was enwrapped in the PCL core.

Figure 1.

Preparation scheme of the Qu-M via a self-assembly method.

Notes: First, quercetin (A) and MPEG–PCL (B) were codissolved in the acetone solution. In this process, quercetin and MPEG–PCL were assembled automatically into the Qu-M (C).

Abbreviations: PCL, poly(ε-caprolactone); PEG, poly(ethylene glycol); QU, quercetin; Qu-M, quercetin-loaded MPEG–PCL nanomicelles; MPEG–PCL, monomethoxy poly(ethylene glycol)–poly(ε-caprolactone).

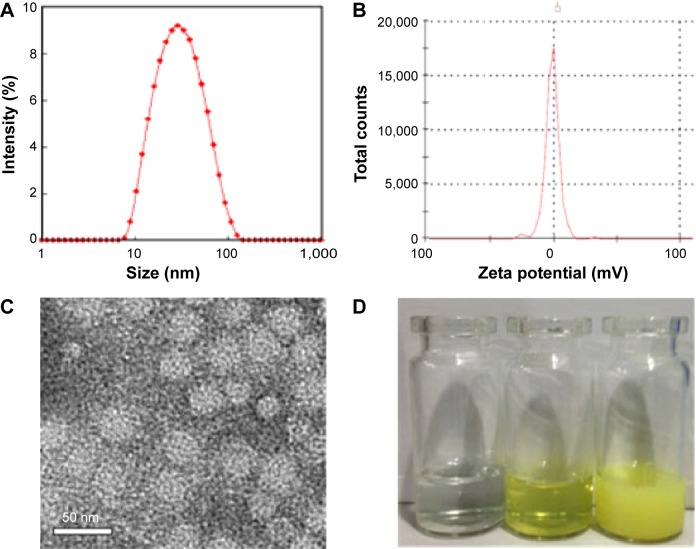

Particle size, zeta potential, DL, and EE of the Qu-M

The particle size and zeta potential of Qu-M, shown in Figure 2, were measured in detail using DLS and TEM. As shown in Figure 2A, the particle size of Qu-M in water was 34.8±3.2 nm, with a polydispersity index (PDI) of 0.14±0.08, showing that Qu-M had a narrow particle size distribution. Meanwhile, TEM was used to observe the morphology of dry Qu-M. As can be seen in Figure 2C, the Qu-M had a spherical structure, the mean diameter of which was about 23 nm. The results from DLS and TEM revealed that the size of Qu-M in water was slightly larger than dry Qu-M, because the amphiphilic block polymeric micelles had a relatively loose structure in aqueous solution. Moreover, the zeta potential of Qu-M was quantified by DLS, which was −1.56±0.15 mV (Figure 2B). In the interest of improving the solubility of quercetin in water, biodegradable polymeric micelles of MPEG–PCL were used to encapsulate quercetin, and the efficacy of this drug delivery system (DDS) can be seen in Figure 2D: the solution of Qu-M was homogeneous in appearance, enunciating Qu-M was completely dissolved in the aqueous solution.

Figure 2.

Characterizations of the Qu-M.

Notes: (A) Size distribution of Qu-M, (B) zeta potential of Qu-M, (C) TEM image of Qu-M, (D) PBS solution, Qu-M in PBS solution, and free quercetin in PBS solution (from left to right).

Abbreviations: Qu-M, quercetin-loaded MPEG–PCL nanomicelles; TEM, transmission electron microscope; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; MPEG–PCL, monomethoxy poly(ethylene glycol)–poly(ε-caprolactone).

Additionally, determined by HPLC and calculated using the equations mentioned earlier, the DL and EE of Qu-M were 6.85% and 97.8%, respectively.

In vitro drug release

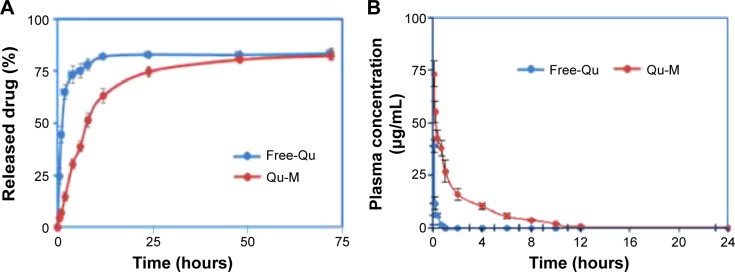

To evaluate the release kinetics of quercetin from the Qu-M in vitro, a dialysis method was used in incubation medium at 37°C, and the release amount of quercetin was detected by HPLC using 421 nm absorbance. As shown in Figure 3A, quercetin was released from Qu-M over a prolonged period compared with free-Qu, which increased sharply to the peak value of 81.9% in 12 hours, indicating that the quercetin encapsulated by MPEG–PCL could be slowly released from Qu-M in a sustained manner in vitro to prolong the effect directly.

Figure 3.

In vitro release study (A) and in vivo pharmacokinetics assay (B) of Qu-M and free-Qu.

Notes: The in vitro release profiles of the Qu-M and free-Qu were examined using a dialysis method, and the in vivo pharmacokinetics was analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography.

Abbreviations: Qu-M, quercetin-loaded MPEG–PCL nanomicelles; free-Qu, free quercetin; MPEG–PCL, monomethoxy poly(ethylene glycol)–poly(ε-caprolactone).

In vivo pharmacokinetics analysis

To confirm whether Qu-M could improve the pharmacokinetics of quercetin in vivo, Sprague Dawley rats were employed to study the pharmacokinetics of Qu-M and free-Qu by HPLC. The rats were randomly divided into two treatment groups – Qu-M and free-Qu – and received a dose of 100 mg/kg, administered intravenously; then, blood specimens were collected and extracted at different predefined intervals. The results obtained by HPLC could be seen in Figure 3B. Tmax (time when the maximum plasma concentration is reached), T1/2, and Cmax of Qu-M were 5 minutes, 0.87 hour, and 73.458 mg/L, respectively, which for free-Qu were 5 minutes, 0.17 hour, and 39.7 mg/L, suggesting that encapsulation of quercetin by MPEG–PCL could enhance the T1/2 and Cmax of quercetin in vivo.

In vitro antitumor activity

Qu-M inhibited colon cancer cell growth in vitro more effectively

The cytotoxic effects of Qu-M and free-Qu on CT26 cells in vitro were evaluated by the cell viability assay. As shown in Figure 4A and B, Qu-M and free-Qu could observably inhibit the growth of CT26 cells in a dose-dependent and time-dependent manner, and the half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of Qu-M at 48 hours was 15.67 μg/mL, which was lower than that of free-Qu (24.87 μg/mL), indicating that the encapsulation of quer-cetin by MPEG–PCL could enhance the cytotoxic activity of quercetin.

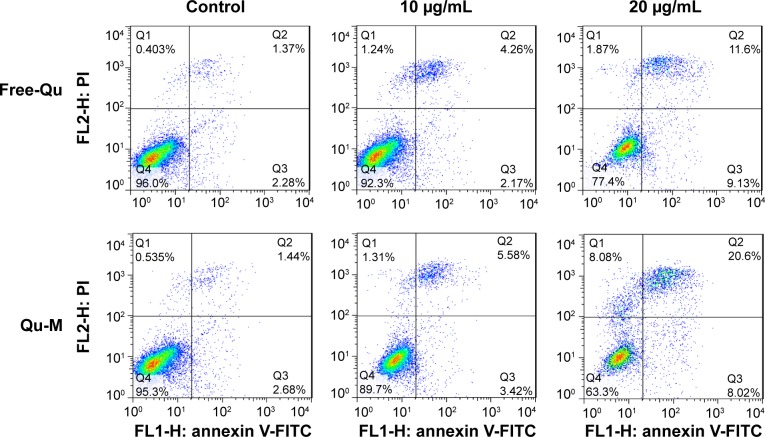

Qu-M induced more colon cancer cell apoptosis

To investigate apoptosis-inducing effects of Qu-M and free-Qu on CT26 cells in vitro, flow cytometry analysis was employed with FITC-labeled Annexin-V/PI double staining assay. According to Figure 5, the proportions of positive cells at different drug concentrations – 10 and 20 μg/mL – were 9%±1.97% and 28.62%±3.35%, respectively, in the Qu-M-treated groups, versus 6.43%±1.62% and 20.73%±2.66% in the free-Qu-treated groups (P<0.01), and 3.65%±0.71% and 4.12%±1.04% in the NS and EM control groups (P<0.01). The results showed that the Qu-M could induce CT26 cell apoptosis more efficiently in vitro than free-Qu.

Figure 5.

The apoptosis-inducing effects of Qu-M and free-Qu in a dose-dependent manner on CT26 cells in vitro.

Notes: The CT26 cells were incubated with Qu-M, free-Qu, NS, and EM for 48 hours, and Annexin-V- and PI-stained cells were determined by flow cytometry.

Abbreviations: Qu-M, quercetin-loaded MPEG–PCL nanomicelles; free-Qu, free quercetin; NS, normal saline; EM, empty MPEG–PCL nanomicelles; MPEG–PCL, monomethoxy poly(ethylene glycol)–poly(ε-caprolactone); PI, propidium iodide; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate.

In vivo antitumor activity

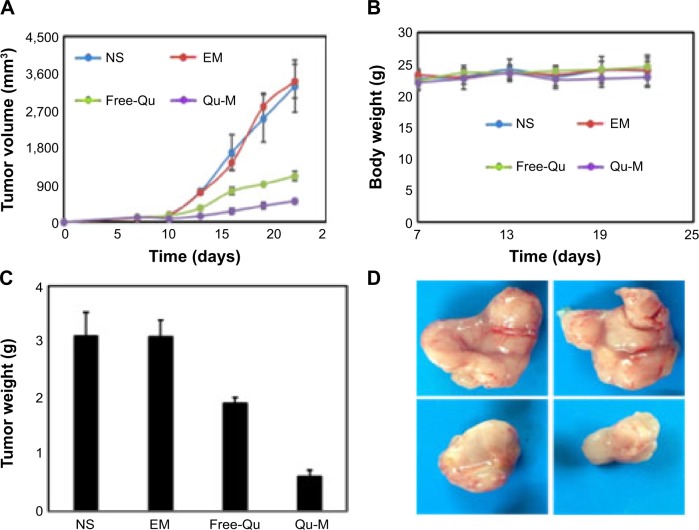

Qu-M inhibited colon tumors more effectively in vivo

In order to evaluate the therapy efficiencies of Qu-M and free-Qu on colon cancer in vivo, the mice subcutaneous CT26 colon cancer model was established. Female BALB/c mice were inoculated subcutaneously in the right flank with suspensions of CT26 colon carcinoma cells; then, the tumor-bearing mice were stochastically divided into four treatment groups: NS, EM, and free-Qu and Qu-M with a dose of 50 mg/kg. The results are shown in Figure 6. The tumor volumes and weights of Qu-M-treated group (Figure 6A and C) were markedly smaller than those of the other groups: NS-treated group (P<0.01), EM-treated group (P<0.01), and free-Qu-treated group (P<0.05). Meanwhile, as observed in Figure 6D, the size of the Qu-M-treated tumor was smallest among the representative images of gross specimens of all groups. What is more, quercetin treatment was well tolerated without significant effect on the body weight, as shown in Figure 6B. All results shown in Figure 6 indicated that Qu-M were more efficacious in repressing the growth of colon tumor than free-Qu in vivo.

Figure 6.

The therapy efficiency of Qu-M and free-Qu on the mice subcutaneous CT26 colon cancer model in vivo.

Notes: Female BALB/c mice were divided into four treatment groups: NS, EM, and free-Qu and Qu-M with a dose of 50 mg/kg. (A) The tumor volumes measured on the indicated days. (B) The body weights of the mice measured on the indicated days. (C) The tumor weights measured on the indicated days. (D) Representative images of tumor gross specimens in each treated group, indicating that Qu-M were more efficacious in repressing the growth of colon tumor in vivo.

Abbreviations: Qu-M, quercetin-loaded MPEG–PCL nanomicelles; free-Qu, free quercetin; NS, normal saline; EM, empty MPEG–PCL nanomicelles; MPEG–PCL, monomethoxy poly(ethylene glycol)–poly(ε-caprolactone).

Induction of tumor cell apoptosis in vivo

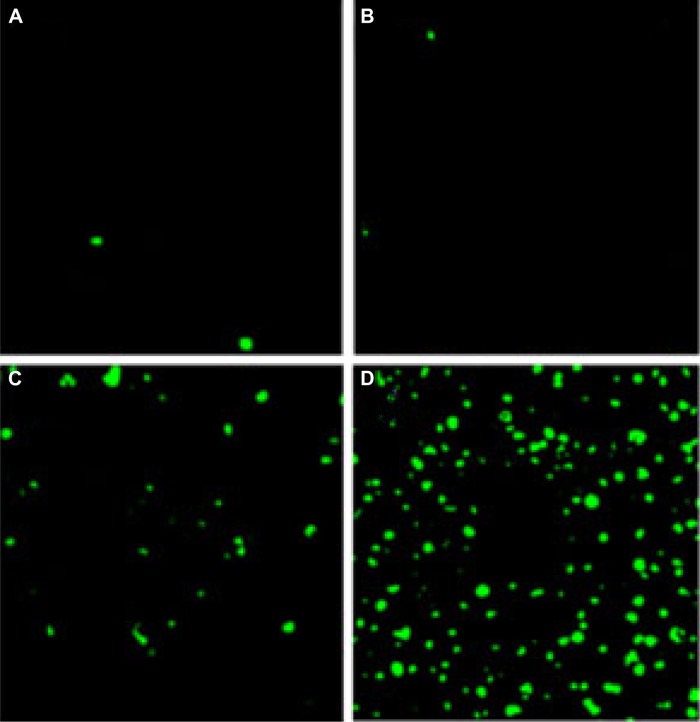

To study the potential mechanisms related to the anti-colon cancer activity of Qu-M and free-Qu in vivo, the TUNEL analysis was employed. A great deal of apoptotic cells with green color could be seen in tumor tissue sections of Qu-M-treated groups (Figure 7A–D), whereas positive cells were less in the other groups. The apoptotic index in Qu-M-treated group was 62.7%, versus 28.23% in free-Qu-treated group (P<0.01), 2.14% in EM-treated group (P<0.01), and 1.31% in NS-treated group (P<0.01), which indicated that inducing apoptosis may be one of the antitumor mechanisms of Qu-M and free-Qu in vivo.

Figure 7.

TUNEL assay.

Notes: Tumor tissue sections of NS-treated group (A), EM-treated group (B), free-Qu-treated group (C), and Qu-M-treated group (D) were stained with TUNEL for the cell apoptosis assay. The results indicate that inducing apoptosis may be one of the antitumor mechanisms of Qu-M and free-Qu in vivo.

Abbreviations: NS, normal saline; EM, empty MPEG–PCL nanomicelles; MPEG–PCL, monomethoxy poly(ethylene glycol)–poly(ε-caprolactone); free-Qu, free quercetin; Qu-M, quercetin-loaded MPEG–PCL nanomicelles.

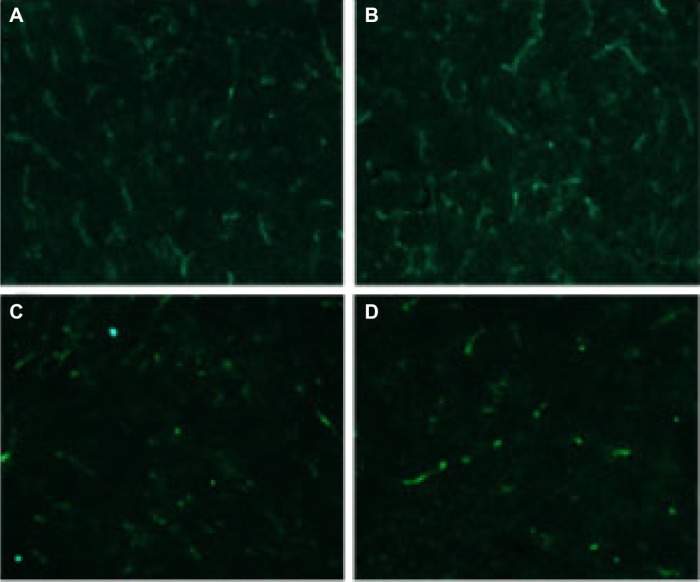

Antiangiogenesis in vivo

Immunofluorescence analysis of neovascularization was used to detect the antiangiogenesis activities of Qu-M and free-Qu in the tumor tissues of animal models. The tumor tissue sections were immunostained with the rat anti-mouse CD31 polyclonal antibodies and rhodamine-conjugated secondary antibodies sequentially to evaluate the microvessel density. As can be seen in Figure 8A–D, the microvessel density in Qu-M-treated group was 23.7, which was observably less than those in free-Qu-treated group (43.8, P<0.01), EM-treated group (97.5, P<0.01), and NS-treated group (92.3, P<0.01), implying that antiangiogenesis may be another antitumor mechanism of Qu-M and free-Qu in vivo.

Figure 8.

CD31 assay.

Notes: Tumor tissue sections of NS-treated group (A), EM-treated group (B), free-Qu-treated group (C), and Qu-M-treated group (D) were immunostained with CD31 for evaluating the microvessel density. The results imply that antiangiogenesis may be another antitumor mechanism of Qu-M and free-Qu in vivo.

Abbreviations: NS, normal saline; EM, empty MPEG–PCL nanomicelles; MPEG–PCL, monomethoxy poly(ethylene glycol)–poly(ε-caprolactone); free-Qu, free quercetin; Qu-M, quercetin-loaded MPEG–PCL nanomicelles.

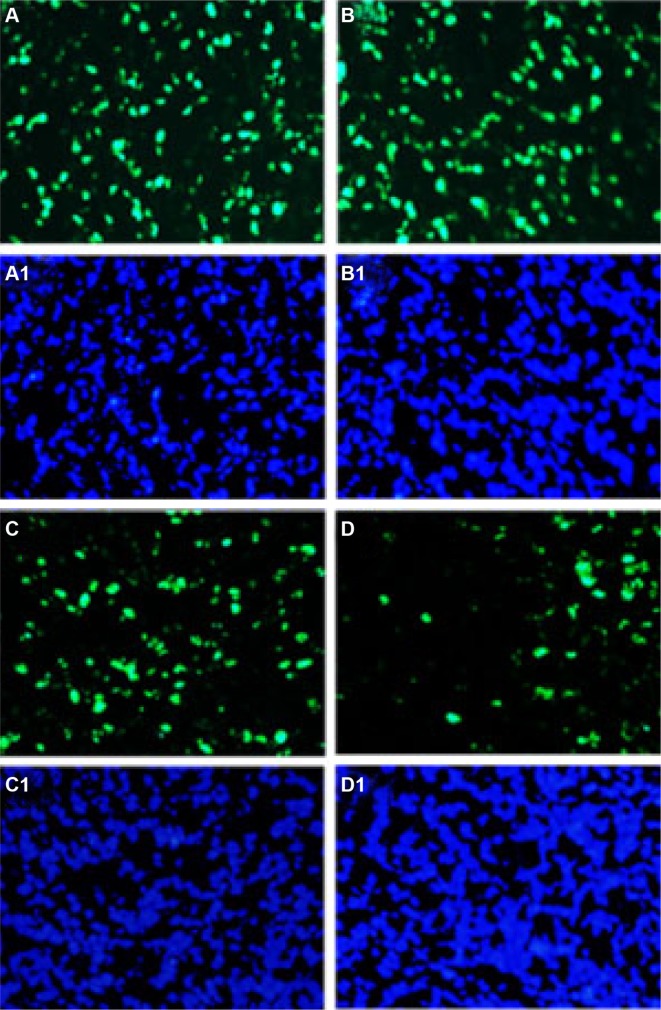

Antiproliferation in vivo

To evaluate the antiproliferation effects of QU-M and free-Qu in mice models of colon cancer, immunofluorescence technology was employed. The tumor tissue sections were immunostained with Ki67 polyclonal antibodies and rhodamine-labeled secondary antibodies sequentially to measure the cell proliferation in vivo (Figure 9A–D1). A few Ki-67-positive cells with green fluorescent nuclei were observed in the tumor tissue sections of Qu-M-treated groups, whereas the positive cells were more in the other groups. The Ki-67 proliferation index in Qu-M-treated group was 17.45%±4.64%, versus 46.3%±9.63% in free-Qu-treated group (P<0.01), 90.3%±11.67% in EM-treated group (P<0.01), and 88.3%±15.63% in NS-treated group (P<0.01), indicating that antiproliferation may be the other antitumor mechanism of Qu-M and free-Qu in vivo.

Figure 9.

Ki-67 assay.

Notes: Tumor tissue sections of NS-treated group (A, A1), EM-treated group (B, B1), free-Qu-treated group (C, C1), and Qu-M-treated group (D, D1) were immunostained with Ki-67 for evaluating the cell proliferation. The results indicate that antiproliferation may be the other antitumor mechanism of Qu-M and free-Qu in vivo. The green fluorescence indicates the Ki-67 protein (A–D) and the blue fluorescence indicates the total cell nuclei (A1–D1).

Abbreviations: NS, normal saline; EM, empty MPEG–PCL nanomicelles; MPEG–PCL, monomethoxy poly(ethylene glycol)–poly(ε-caprolactone); free-Qu, free quercetin; Qu-M, quercetin-loaded MPEG–PCL nanomicelles.

Discussion

Chemotherapy is one of the cardinal means for tumor therapy; however, it always has a lot of relatively serious or minor side effects to normal organs. Therefore, it is imperative to improve the therapeutic modalities with no or minimal side effects. To address this requirement, the applications of natural dietary phytochemicals for tumor treatment has been studied.24,25 Multifarious plant polyphenolic compounds have aroused more attention owing to their multiple pharmacological activities. Flavonoids have the potential antiproliferation, antitumor, and antioxidant activities, and have been suggested in the treatment of a variety of illnesses, including tumors.26,27 Quercetin, as a type of widespread natural bioflavonoids, has a potential application in tumor chemotherapy.

Despite the tantalizing prospects of quercetin in tumor chemotherapy, its applications were hampered due to the low hydrophilicity. Furthermore, after the drug administration, the fast metabolization and cleaning-up exacerbates the poor bioavailability of quercetin. Thus, a strategy to improve the solubility of quercetin in water and/or enhance the bioavailability is desired, and fortunately, nanotechnology provides an attractive platform to address this need.28–30 The rapid development of nanotechnology has provided a significant path for water-soluble preparation of hydrophobic drugs and has attracted a growing attention in drug delivery and cancer treatment.31–35 Since the biodegradable polymeric micelles are extensively employed in the DDSs,36,37 many antitumor drugs delivered by this DDS are already in clinical study or marketed. Polymeric micelles are assembled by amphiphilic copolymers to form nanomicelles, where the hydrophobic domains aggregate together (core) to form an effective hydrophobic drug nanoparticle container, and the hydrophilic segments (shell) are the stable interface of self-assembly particles.38 The hydrophobic compounds encapsulated in the polymeric micelles could completely dissolve in the aqueous solution and form a stable and homogeneous solvent for intravenous infusion.39 In addition, the tiny size and the stable hydrophilic interface of the micelles can prolong the quercetin release and circulation in vivo, and consequently increase cellular intake. More importantly, the polymeric micelles could passively target the tumor through their enhanced permeability and retention effect, thereby enhancing the antitumor effects.40 Thus, because of the sustained drug effect of the biodegradable polymer nanoparticle on the injury site, fewer side effects, increased penetration of the drug into the tumor, better passage through physiological barriers, and controllable targeting drug delivery, it is now administrated to be widely used.41,42 The biodegradable nanosized amphiphilic block copolymers of poly(ethylene glycol)–poly(ε-caprolactone) (PEG-PCL) are easily produced, demonstrating tantalizing prospects in DDSs.43–45 Recently, improvement of the water solubility of hydrophobic drugs through their encapsulation by PEG-PCL has attracted great attention.

In the interest of improving the solubility of quercetin in water and enhancing its bioavailability, in our study, quercetin was encapsulated into the biodegradable nanosized amphiphilic block copolymers of MPEG–PCL via a self-assembly method. The characteristics of Qu-M were small size, high capacity, and high drug EE. In vitro, drug release demonstrated that the quercetin encapsulated by MPEG–PCL could be slowly released from Qu-M. In vivo, pharmacokinetics analysis showed that encapsulation of quercetin by MPEG–PCL could enhance the T1/2 and Cmax of quercetin.

In addition, experiments on CT26 cells in vitro demonstrated that QU-M could improve the cytotoxicity of quercetin and also induce more colon tumor cell apoptosis efficiently than free-Qu.

In order to evaluate the therapy efficiencies of Qu-M and free-Qu on colon cancer in vivo, the mice subcutaneous CT26 colon cancer model was established. The results indicated that Qu-M were more efficacious in repressing the growth of colon tumor than was free-Qu in vivo. TUNEL assay, and CD31 and K-i67 examinations showed that QU-M could induce more colon tumor cell apoptosis efficiently, and inhibit the tumor angiogenesis and cell proliferation more effectively in vivo, which, as a whole, indicate that promoting apoptosis, antiangiogenesis, and antiproliferation may be the essential anti-colon cancer mechanisms of quercetin.

Compared with free-Qu, Qu-M could suppress the tumor growth more strikingly in vitro and in vivo. These advantages of Qu-M could be explained by better quercetin uptake from Qu-M by the tumor cells, as the nanomicelles enhance the biocompatibility and bioavailability of quercetin. These results suggest that Qu-M may have a promising potential application in colorectal tumor chemotherapy.

Conclusion

Biodegradable nanosized Qu-M with good water solubility could be prepared by a self-assembly method for the therapy of colon cancer in vitro and in vivo. The Qu-M showed an enhanced anti-colon cancer activity than did free-Qu by inducing more colon tumor cell apoptosis and inhibiting tumor angiogenesis and cell proliferation effectively in vitro and in vivo, indicating a tantalizing application prospect in colon cancer chemotherapy.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC81101603 and NSFC81101604).

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Zauber AG, Winawer SJ, O’Brien MJ, et al. Colonoscopic polypectomy and long-term prevention of colorectal-cancer deaths. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(8):687–696. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1100370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rebecca S, Jiemin M, Zhaohui Z, et al. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:9–29. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rebecca S, Carol DS, Ahmedin J. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:104–117. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turati F, Edefonti V, Bravi F, et al. Adherence to the European food safety authority’s dietary recommendations and colorectal cancer risk. J Clin Nutr. 2012;66:517–522. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2011.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Key TJ, Appleby PN, Masset G, et al. Vitamins, minerals, essential fatty acids and colorectal cancer risk in the United Kingdom Dietary Cohort Consortium. J Cancer. 2012;131:320–325. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boffetta P, Hazelton WD, Chen Y. Body mass, tobacco smoking, alcohol drinking and risk of cancer of the small intestine – a pooled analysis of over 500,000 subjects in the Asia Cohort Consortium. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:1894–1898. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joshu CE, Parmigiani G, Colditz GA, Platz EA. Opportunities for the primary prevention of colorectal cancer in the United States. Cancer Prev Res. 2012;5:138–145. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Kruijsdijk RC, van der Graaf Y, Peeters PH, Visseren FL. Cancer risk in patients with manifest vascular disease: effects of smoking, obesity, and metabolic syndrome. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22:1267–1277. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-0090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saleh M, Trinchieri G. Innate immune mechanisms of colitis and colitis-associated colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:9–20. doi: 10.1038/nri2891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seshagiri S, Stawiski EW, Durinck S, et al. Recurrent R-spondin fusions in colon cancer. Nature. 2012;488:660–664. doi: 10.1038/nature11282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prahallad A, Sun C, Huang S, et al. Unresponsiveness of colon cancer to BRAF(V600E) inhibition through feedback activation of EGFR. Nature. 2012;483:100–103. doi: 10.1038/nature10868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qinjie W, Senyi D, Ling L, et al. Biodegradable polymeric micelle-encapsulated quercetin suppresses tumor growth and metastasis in both transgenic zebrafish and mouse models. Nanoscale. 2013;5:12480–12493. doi: 10.1039/c3nr04651f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gupta SC, Kim JH, Prasad S, et al. Regulation of survival, proliferation, invasion, angiogenesis, and metastasis of tumor cells through modulation of inflammatory pathways by nutraceuticals. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2010;29(3):405–434. doi: 10.1007/s10555-010-9235-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Slusarz A, Shenouda NS, Sakla MS, et al. Common botanical compounds inhibit the Hedgehog signaling pathway in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2010;70:3382–3391. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng S, Gao N, Zhang Z, et al. Quercetin induces tumor selective apoptosis through down regulation of Mcl-1 and activation of bax. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:5679–5692. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sahoulia F, Drosopoulos K, Doubravska L, et al. Quercetin enhances TRAIL-mediated apoptosis in colon cancer cells by inducing the accumulation of death receptors in lipid rafts. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:2591–2599. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones D, Lamb JH, Verschoyle RD, et al. Characterisation of metabolites of the putative cancer chemopreventive agent quercetin and their effect on cyclooxygenase activity. Br J Cancer. 2004;91:1213–1219. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tottey S, Waldron KJ, Firbank SJ. Protein-folding location can regulate manganese-binding versus copper- or zinc-binding. Nature. 2008;455:1138–1142. doi: 10.1038/nature07340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Voelkel JC. TRAIL-mediated signaling in prostate, bladder and renal cancer. Nat Rev Urol. 2011;8:417–427. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2011.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coleman DT, Bigelow R, Cardelli JA. Inhibition of fatty acid synthase by luteolin post-transcriptionally down-regulates c-Met expression independent of proteosomal/lysosomal degradation. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:214–224. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xiang G, Bilan W, Xiawei W, et al. Anticancer effect and mechanism of polymer micelle-encapsulated quercetin on ovarian cancer. Nanoscale. 2012;4:7021–7030. doi: 10.1039/c2nr32181e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xiang G, Fengjin Z, Gang G, et al. Improving the anti-colon cancer activity of curcumin with biodegradable nano-micelles. J Mater Chem B. 2013;1:5778–5790. doi: 10.1039/c3tb21091j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang BL, Gao X, Men K, et al. Treating acute cystitis with biodegradable micelle-encapsulated quercetin. Int J Nanomed. 2012;7:2239–2247. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S29416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen A, Xu J, Johnson AC. Curcumin inhibits human colon cancer cell growth by suppressing gene expression of epidermal growth factor receptor through reducing the activity of the transcription factor Egr-1. Oncogene. 2006;25:278–287. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O’Sullivan-Coyne G, O’Sullivan GC, O’Donovan TR, et al. Curcumin induces apoptosis-independent death in oesophageal cancer cells. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:1585–1595. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wei YQ, Zhao X, Kariya Y, et al. Induction of apoptosis by quercetin: involvement of heat shock protein. Cancer Res. 1994;54:4952–4957. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yuan ZP, Chen LJ, Fan LY, et al. Liposomal quercetin efficiently suppresses growth of solid tumors in murine models. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:3193–3199. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li X, Zhang Z, Li J, et al. Diclofenac/biodegradable polymer micelles for ocular applications. Nanoscale. 2012;4:4667–4673. doi: 10.1039/c2nr30924f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parrott MC, DeSimone JM. Drug delivery: relieving PEGylation. Nat Chem. 2012;4:13–14. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guo G, Fu SZ, Zhou LX, et al. Preparation of curcumin loaded poly(ε-caprolactone)-poly(ethylene glycol)-poly(ε-caprolactone) nanofibers and their in vitro antitumor activity against Glioma 9L cells. Nanoscale. 2011;3:3825–3832. doi: 10.1039/c1nr10484e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Srikanth M, Kessler JA. Nanotechnology-novel therapeutics for CNS disorders. Nat Rev Neurol. 2012;8:307–318. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2012.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zubarev ER. Nanoparticle synthesis: any way you want it. Nat Nanotechnol. 2013;8:396–397. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2013.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang Q, Zhuang X, Mu J, et al. Delivery of therapeutic agents by nanoparticles made of grapefruit-derived lipids. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1867. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brinker CJ. Nanoparticle immunotherapy: Combo combat. Nat Mater. 2012;11:831–832. doi: 10.1038/nmat3434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bee-Jen T, Yuanjie L, Kai-Lun C, et al. Perorally active nanomicellar formulation of quercetin in the treatment of lung cancer. Int J Nanomed. 2012;7:651–661. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S26538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gao X, Wang B, Wei X, et al. Anticancer effect and mechanism of polymer micelle-encapsulated quercetin on ovarian cancer. Nanoscale. 2012;4:7021–7030. doi: 10.1039/c2nr32181e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cabral H, Matsumoto Y, Mizuno K, et al. Accumulation of sub-100 nm polymeric micelles in poorly permeable tumours depends on size. Nat Nanotechnol. 2011;6:815–823. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2011.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.MacKay JA, Chen M, McDaniel JR, et al. Self-assembling chimeric polypeptide-doxorubicin conjugate nanoparticles that abolish tumours after a single injection. Nat Mater. 2009;8:993–999. doi: 10.1038/nmat2569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gong C, Xie Y, Wu Q, et al. Improving anti-tumor activity with polymeric micelles entrapping paclitaxel in pulmonary carcinoma. Nanoscale. 2012;4:6004–6017. doi: 10.1039/c2nr31517c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gong C, Wang C, Wang Y, et al. Efficient inhibition of colorectal peritoneal carcinomatosis by drug loaded micelles in thermosensitive hydrogel composites. Nanoscale. 2012;4:3095–3104. doi: 10.1039/c2nr30278k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gao X, Wang B, Wei X, et al. Preparation, characterization and application of star-shaped PCL/PEG micelles for the delivery of doxorubicin in the treatment of colon cancer. Int J Nanomed. 2013;8:971–982. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S39532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kataoka K, Harada A, Nagasaki Y. Block copolymer micelles for drug delivery: design, characterization and biological significance. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;47:113–131. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00124-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gou ML, Men K, Shi HS, et al. Curcumin loaded biodegradable polymeric micelle for colon cancer therapy in vitro and in vivo. Nanoscale. 2011;3:1558–1567. doi: 10.1039/c0nr00758g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gou M, Wei X, Men K, et al. PCL/PEG copolymeric nanoparticles: potential nanoplatforms for anticancer agent delivery. Curr Drug Targets. 2011;12:1131–1150. doi: 10.2174/138945011795906642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chakraborty S, Stalin S, Das N, et al. The use of nanoquercetin to arrest mitochondrial damage and MMP-9 up regulation during prevention of gastric inflammation induced by ethanol in rat. Biomaterials. 2012;33:2991–3001. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]