Abstract

Tryptophan-2,3-dioxygenase (TDO) physiologically regulates systemic tryptophan levels in the liver. However, numerous studies have linked cancer with activation of local and systemic tryptophan metabolism. Indeed, similar to other heme dioxygenases TDO is constitutively expressed in many cancers. In the present study, we detected the presence of both CD8+ and CD4+ T-cell reactivity toward TDO in peripheral blood of patients with malignant melanoma (MM) or breast cancer (BC) as well as healthy subjects. However, TDO-reactive CD4+ T cells constituted distinct functional phenotypes in health and disease. In healthy subjects these cells predominately comprised interferon (IFN)γ and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α producing Th1 cells, while in cancer patients TDO-reactive CD4+ T-cells were more differentiated with release of not only IFNγ and TNFα, but also interleukin (IL)-17 and IL-10 in response to TDO-derived MHC-class II restricted peptides. Hence, in healthy donors (HD) a Th1 helper response was predominant, whereas in cancer patients CD4+ T-cell responses were skewed toward a regulatory T cell (Treg) response. Furthermore, MM patients hosting a TDO-specific IL-17 response showed a trend toward an improved overall survival (OS) compared to MM patients with IL-10 producing, TDO-reactive CD4+ T cells. For further characterization, we isolated and expanded both CD8+ and CD4+ TDO-reactive T cells in vitro. TDO-reactive CD8+ T cells were able to kill HLA-matched tumor cells of different origin. Interestingly, the processed and presented TDO-derived epitopes varied between different cancer cells. With respect to CD4+ TDO-reactive T cells, in vitro expanded T-cell cultures comprised a Th1 and/or a Treg phenotype. In summary, our data demonstrate that the immune modulating enzyme TDO is a target for CD8+ and CD4+ T cell responses both in healthy subjects as well as patients with cancer; notably, however, the functional phenotype of these T-cell responses differ depending on the respective conditions of the host.

Keywords: immune regulation, T cells, TDO, Th17, Tregs

Introduction

The immune system is tightly controlled to avoid the occurrence of autoimmunity when responding to various pathogens. This enantiostasis, allowing at the same time destruction of infected or transformed cells and self-tolerance, is guarded by several feedback mechanisms. Unfortunately, some of the mechanisms preventing autoimmunity are hijacked by cancers to attain immune escape. This evasion of immune destruction is based on several mechanisms including depletion of essential nutrients as well as accumulation of immunosuppressive metabolites. Thus, metabolic changes within the tumor microenvironment help to evade antigenic specific immune responses. In this respect, aberrations of the metabolism of the essential amino acid L-tryptophan have been described in various cancers. Notably, controlling the level of tryptophan is an important part of the host defense against invading pathogens as microbes need high concentrations of available tryptophan for optimal growth.1

The degradation of L- (and D-) tryptophan to N-formylkynurenine is catalyzed by the heme dioxygenases TDO and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO).2 TDO and IDO do not share sequence homology although there is a high degree of structural similarity in the area around the heme-binding motif and the catalytic site.3 Although by distinct mechanisms, both TDO and IDO catalyze the first and rate-limiting step of tryptophan oxidation yielding kynurenine.4 Moreover, as IDO is upregulated by inflammatory cytokines such as type I and II interferon's, it is thought to be an important counter-regulatory enzyme, which controls disproportionate immune responses.5

The impact of tryptophan metabolism on immune responses is well established. T cells sense low levels of tryptophan via the serine/threonine-protein kinase GCN2, which is then triggering proliferative arrest.6 Moreover, the tryptophan degradation product kynurenine binds the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR); activation of AHR signaling induces formation of Tregs.7

Indeed, IDO expression has been repeatedly reported in cancer 5,8 and it has been demonstrated that tumor cells transfected with IDO become resistant to immune eradication 8-10; thus, IDO has been the focus of much attention.11 Several clinical trials with IDO inhibitors such as INCB024360 alone or in combination with other immune modulatory therapeutics are currently actively recruiting patients to treat different forms of cancer (http://clinicaltrials.gov). Furthermore, in a phase I clinical trial long-lasting disease stabilization was observed in lung cancer patients vaccinated with an HLA-A2-restricted epitope derived from IDO.12 Less is known about the function of TDO in cancer. Under physiologic conditions TDO is almost exclusively expressed at high amounts in the liver and – in lower levels – in the brain. Recently, it was described that tumors of different origin express TDO, especially melanoma, bladder cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma and glioblastoma.7,13 It still remains to be established, however, to which extent TDO and/or IDO contribute to tumor-associated immune suppression: in a series of 104 human tumor cell lines of various histological types, 20 tumors expressed only TDO, 17 only IDO and 16 both enzymes.13 Moreover, in a preclinical model, TDO expression by tumors prevented their rejection by mice immunized against the respective TDO-negative tumor.13

Based on our previous detection of adaptive immune responses against IDO – as well as other immune regulatory elements – in cancer patients together with the observation that targeting immune suppressive IDO+ dendritic cells (DC) by such IDO-reactive T cells boosts immunity,14–16 we proposed the concept of supporter T cells15 or regulatory self-reactive T cells.17,18 Here, we extent this concept by demonstrating that the immune modulating enzyme TDO is a target for CD8+ and CD4+ T cell responses; notably, the functional phenotype of these T-cell responses differed depending whether present in healthy subjects or cancer patients. Thus, under physiologic conditions TDO-specific effector T cells may contribute to immune-regulatory networks by subjugating the immune suppressive actions, which are a consequence of the TDO-expression in the target cells. In contrast, in patients with cancer TDO-specific Tregs may enhance TDO-mediated immune suppression.

Results

Presence of TDO-reactive CD8+ T cell in peripheral blood of healthy donors and cancer patients

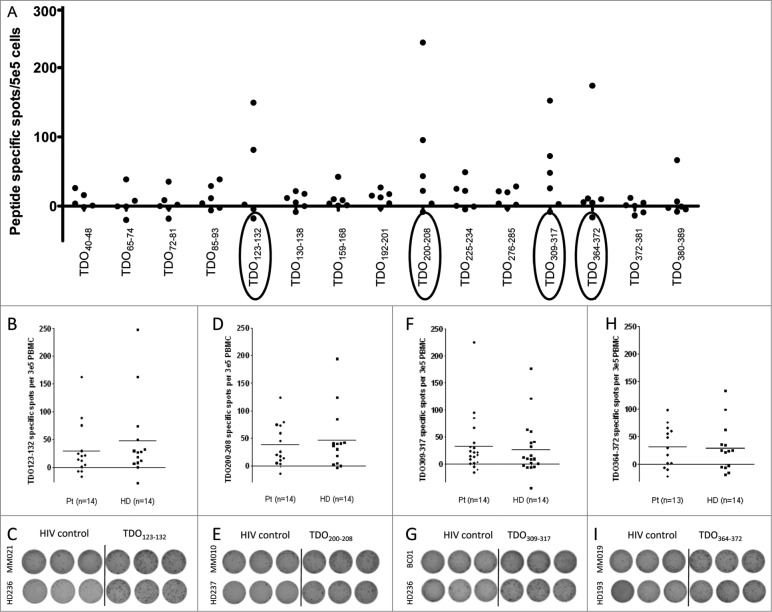

Potential HLA-A2-restricted T-cell epitopes derived from the TDO amino acid sequence were identified based on the well-defined HLA-binding motif (16). The fifteen 9- to 10-mer peptides with the highest predicted binding affinity were synthesized and subsequently used to screen PBMC from six MM patients for the presence of spontaneous T-cell responses by means of the ELISPOT assay. This analysis revealed the presence of IFNγ producing T-cell in response to the peptides TDO123-132 (KLLVQQFSIL), TDO200-208, (TLLELVEAWL), TDO309-317 (QLLTSLMDI), and TDO364-372 (DLFNLSTYL) after one round of in vitro stimulation (Fig. 1A). Notably, for several of these peptides T-cell responses were detected in more than one patient. Prompted by these encouraging observations, we used four TDO-derived HLA-A2-restricted T-cell epitopes to analyze PBMCs obtained from 13 additional MM patients as well as a BC patient in addition to PBMCs from 14 HD for the presence of TDO-reactive T cells; again analyses were performed after one round of in vitro stimulation. As depicted in Fig. 1, we detected T-cell responses against all four peptides both in MM and BC patients as well as in HD. Surprisingly, the magnitude and frequency of responses were similar in both groups. The non-parametric distribution free resampling (DFR) method allows statistical comparison of antigen-stimulated wells and negative control. Examples of significant responses are given in Fig. S1. Moreover, we were also able to detect TDO-reactive T cells directly ex vivo (Fig. S2).

Figure 1.

Natural T-cell responses against TDO. (A) In order to detect TDO-specific CD8+ T-cell responses, 15 predicted HLA-A2 restricted T-cell epitopes were synthesized to examine peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from 6 HLA-A2+ MM patients. PBMC samples were stimulated once in vitro with peptide and IL-2 for one week before being plated in an IFNγ ELISPOT assay at 5 × 105 cells per well in triplicates with or without a relevant TDO peptide. The average number of TDO-specific, IFNγ-releasing cells was calculated per 5 × 105 PBMC. IFNγ ELISPOT responses against TDO123-132 (KLLVQQFSIL) in 13 MM patients, 1 BC patient and 14 healthy donors. T cells were stimulated once with peptide before being plated in an IFNγ ELISPOT assay at 3 × 105 cells per well in triplicates with the TDO123-132 (B), TDO200-208 (D), TDO309-317 (F), TDO364-372 (H), or a negative control peptide (HIVpol476-484 (ILKEPVHGV)). The dot plots designate mean spot count of triplicate positive wells with subtraction of background. Examples of ELISPOT experiments against TDO123-132 (C), TDO200-208 (E), TDO309-317 (G), TDO364-372 (I),and HIVpol476-484 in PBMC from different cancer patients or healthy donors.

Generation and functional characterization of TDO-specific CD8+ T-cell lines

The detection and characterization of specific CD8+ T cells was revolutionized by the introduction of soluble peptide/MHC complexes.19 However, in order to stabilize such soluble peptide/MHC complexes, peptides have to bind with a sufficient high affinity to the respective MHC molecule. Thus, we next examined the binding affinity of TDO to HLA-A2 in comparison to the well-characterized high affinity HLA-A2 binding peptides HIV pol468-476 (ILKEPVHGV) and CMV pp65495-503 (NLVPMVATV) using the HLA peptide exchange/ELISA technology.20 TDO200-208 and TDO309-317 peptides bound with the same high affinity as the control peptides, whereas TDO123-132 and TDO364-372 displayed an lower binding affinity to HLA-A2 (Fig. S3). For all TDO peptides, however, the respective binding affinity was sufficient for generation of soluble peptide/MHC complexes for further detailed analyses of TDO-reactive CD8+ T cells.

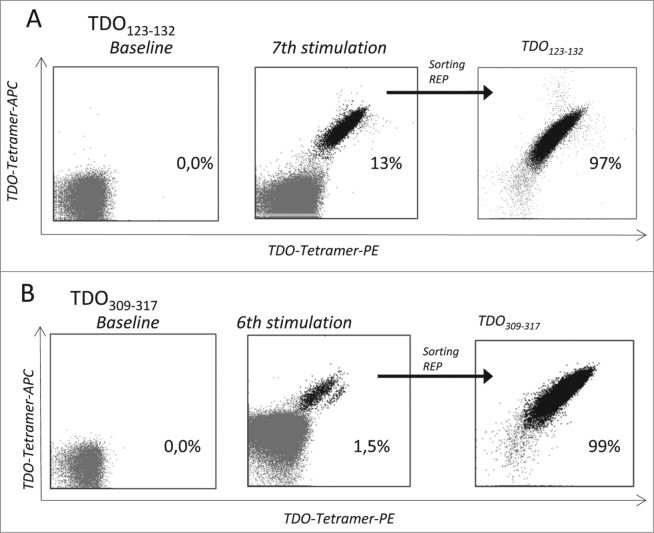

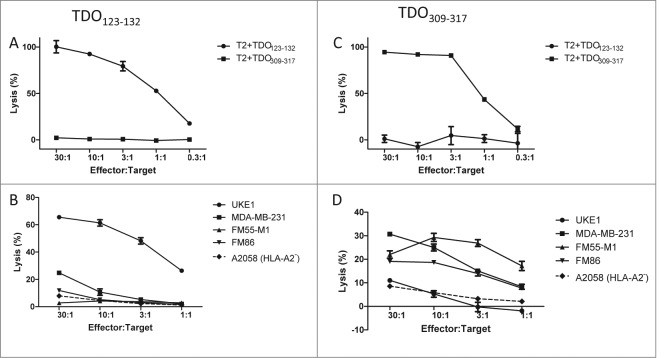

To establish such TDO-specific CD8+ T cell lines, we repeatedly stimulated PBMCs from a BC patient with autologous DC loaded with the TDO peptides TDO123-132 or TDO309-317 5- or 4- times respectively. These in vitro stimulations dramatically increased the frequency of TDO-specific CD8+ T cells as measured by two color tetramer staining (Fig. 2). For further expansion by means of the rapid expansion protocol (REP) TDO123-132 and TDO309-317 reactive T cells were enriched by fluorescence-activated cell sorting. After applying REP the specificity of the resulting T-cell lines was confirmed by tetramer staining demonstrating 97.1% and 99.6% purity (Fig. 2). These T-cell lines were tested for their capabilities to lyse either TAP-deficient peptide-pulsed T2 cells or HLA-matched TDO-expressing tumor cells. As depicted in Figs. 3A and B, TDO-specific T-cell cultures effectively lysed T2 cells when these had been pulsed with the same TDO peptide used for expansion, but not T2 cells pulsed with an irrelevant different TDO-derived peptide. Most important, TDO-specific T cells efficiently lysed HLA-A2+ cancer cell lines of different tissue origin, but not HLA-A2− cancer cells (Figs. 3C and D). The lysis of TDO-expressing cancer cell lines was not uniform. Specifically, the breast cancer cell line MDA-MB 231 was killed by both TDO123-132 and TDO309-317 specific T-cell lines; the latter T-cell line demonstrating more efficient killing. On the other hand, the HLA-A2+ leukemia cell line UKE-1 was very effectively lysed by TDO123-132 specific T cells, but only scarcely by TDO309-317 specific T cells. TDO123-132 specific T cells did not lyse HLA-A2+ melanoma cell lines FM-55M1 and FM-86, which were efficiently lysed by TDO309-317 specific T cells. Finally, the HLA-A2−TDO+ melanoma cell line A2058 was not lysed by either T-cell line.

Figure 2.

Expansion of TDO-specific CD8+ T cells. Tetramer analysis of TDO-specific T-cells; Examples of TDO123-132 (A) or TDO309-317 (B) -specific CD8+ T-cells among PBMC from a BC patient (BC1) as visualized by flow cytometry staining using the tetramers HLA-A2/ TDO123-132-PE, HLA-A2/ TDO123-132-APC. The stainings were performed directly ex vivo (left), after peptide stimulations in vitro (middle), and after sorting and expansion of tetramer-positive cells by FACS (right).

Figure 3.

Cytolytic capacity of TDO-specific T cells. (A) The lysis of T2-cells pulsed with either relevant TDO123-132 peptide (black squares) or an irrelevant TDO peptide TDO309-317 (gray squares) by the TDO123-132-specific T-cell culture as examined by 51Cr-release assay. X-axis designate effector:target ratio. (B) Lysis by TDO123-132-specific T cells of the HLA-A2+ melanoma cell lines FM-55M1 and FM-86, the breast cancer cell line MDA-MB 231, and the AML cell line UKE-1 at different effector to target ratios as assayed by 51Cr-release. In addition the melanoma cell line A2058 (HLA-A2 negative) was examined as negative control. (C) The lysis of T2-cells pulsed with either relevant TDO309-317 peptide (black squares) or an irrelevant TDO peptide TDO123-132 (gray squares) by the TDO309-317-specific T-cell culture as examined by 51Cr-release assay. (D) Lysis by TDO309-317 -specific T cells of the HLA-A2+ melanoma cell lines FM-55M1 and FM-86, the breast cancer cell line MDA-MB 231, and the AML cell line UKE-1 at different effector to target ratios as assayed by 51Cr-release. In addition the melanoma cell line A2058 (HLA-A2 negative) was examined as negative control.

TDO-reactive CD4+ T cells are present in peripheral blood of healthy donors and cancer patients

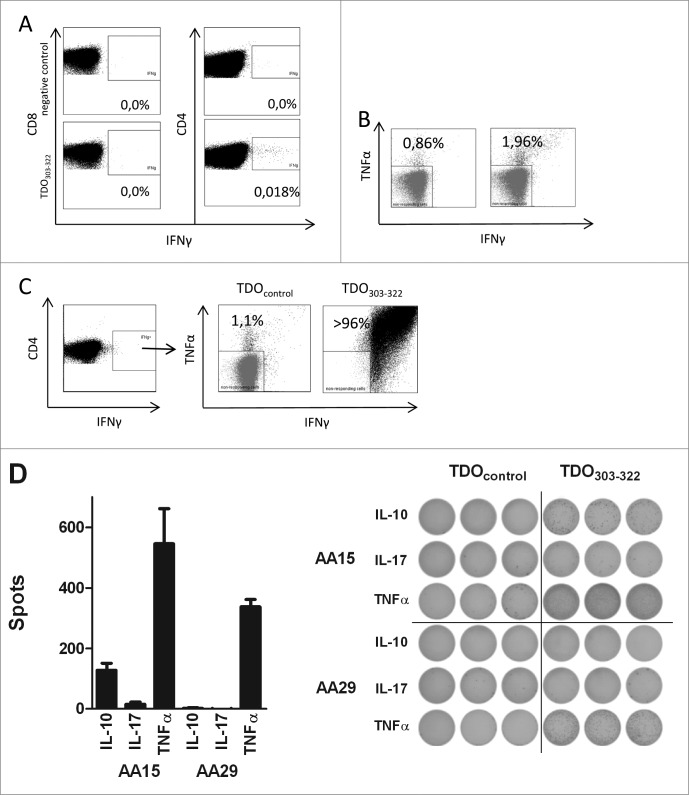

CD4+ T cells not only contribute to efficient activation of CD8+ T cells, but they exert major regulatory functions ensuring the homeostasis of the immune system.21 Consequently, we investigated the immunogenicity of TDO with respect to CD4+ T-cell responses. For this we utilized a long TDO-derived peptide, i.e. TDO303-322 (RFQ VPF QLL TSL MDI DSL MT), which includes the HLA-A2 restricted CD8+ T-cell epitope TDO309-317 (QLLTSLMDI). Intracellular cytokine staining (ICS) for IFNγ production in response to TDO303-322 revealed that the respective stimulation of PBMCs obtained from MM patients induced IFNγ production in CD4+ T cells, but not in the CD8+ T-cells (Fig. 4A). To confirm that the IFNγ production in response to TDO303-322 was indeed due to CD4+ T cells, we enriched CD4+ cells by magnetic beads using negative selection, which resulted in pure CD4+ populations (Fig. S4A). The CD4+ enriched cells were compared to the original PBMC samples with respect to the frequency of peptide-reactive cells in an IFNγ ELISPOT assay. The numbers of CD4+ cells in the enriched and bulk cultures were adjusted to employ identical numbers of CD4+ T cells in each well. The results from these experiments clearly confirmed that release of IFNγ in response to the long TDO-derived peptide was from CD4+ T cells (Fig. S4B).

Figure 4.

CD4+ T-cell responses against TDO. (A) PBMC from a MM patient (MM020) were stimulated once with either an irrelevant HIV peptide (top) or the long TDO303-322 peptide (bottom) before being analyzed by intracellular IFNγ staining. FACS plots were gated on living CD8+ T cells (left) or CD4+ T cells (right). (B) PBMC from a MM patient (MM020) peptide were stimulated four times with DC pulsed with TDO303-322. The resulting T-cell culture was stimulated once with either an irrelevant long TDO peptide (TDO118-137 (left) or the long TDO303-322 peptide (right) before being analyzed by intracellular TNFα and IFNγ staining. (C) PBMC from a MM patient (MM020) peptide were stimulated with TDO303-322 (left). The IFNγ+CD4+ T cells were sorted by FACS and expanded by REP. The resulting T-cell culture was stimulated once with either an irrelevant long TDO peptide (TDO118-137 (left) or the long TDO303-322 peptide (right) before being analyzed by intracellular TNFα and IFNγ staining. The T-cell culture was highly TDO303-322 specific. (D) ELISPOT analysis of reactivity toward TDO303-322 in two highly specific T-cell lines from two MM patients (MM014 and MM020). 10,000 T cells were analyzed with or without TDO303-322. The bars in the panel depict mean value of triplicate experiments, background subtracted (left). The well images are depicted for both T-cell cultures (right).

To scrutinize TDO-specific CD4+ T-cell responses in more detail, we generated T-cell lines specific for TDO303-322 from two MM patients by repeated stimulation with autologous, peptide loaded DCs. After four rounds of in vitro stimulation a clear CD4+ T-cell TDO303-322 reactive population were evident in the cultures as measured by ICS (Fig. 4B). Next, we directly sorted the IFNγ producing CD4+ T cells by capturing newly released IFNγ on the surface of the cells, labeling the captured IFNγ with a specific antibody coupled to the fluorochrome Phycoerythrin (PE) (Fig. 4C). PE-positive CD4+ T cells were isolated by fluorescence-activated cell sorting and expanded using the REP as described. The resulting CD4+ T-cell cultures were highly specific for TDO303-322 as measured by ICS for TNFα and IFNγ production in response to the relevant peptide (Fig. 4C).

The ICS data already demonstrated that the TDO-reactive CD4+ T-cell line produce more than IFNγ. Thus, we assessed the cytokine profile of the T-cell lines by means of TNFα, IL-17A, and IL-10 ELISPOT assays. This analyses demonstrated not only the high frequency of TNFα producing cells, but also IL-10 producing TDO-reactive T cells (Fig. 4D). IL-17A production, however, was not detected in these experiments.

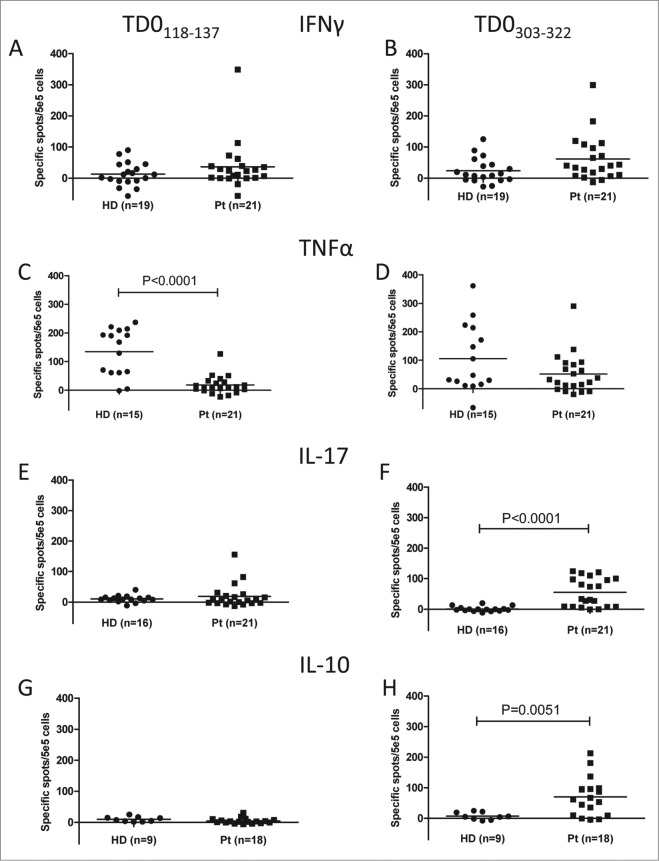

Phenotype of TDO-specific CD4+ T-cell responses differ in health and cancer

Prompted by the mixed cytokine production patterns of the TDO-reactive CD4+ T-cell cultures, i.e., corresponding to a Th1 or a Treg phenotype, we expanded the characterization of TDO-specific CD4+ T cell responses to a larger series of both HD and MM patients in addition to a BC patient. For this purpose we used two long peptides TDO-derived peptides. In addition to TDO303-322, we utilized TDO118-137 (VSV ILK LLV QQF SIL ETM TA), which includes the HLA-A2-restricted CD8+ T-cell epitope TDO123-132 (KLLVQQFSIL), in ELISPOT assays for IFNγ, TNFα, IL-10, and IL-17A (Fig. 5). Peptide-specific CD4+ T-cell responses were present in both MM and BC patients and in HD. With respect to IFNγ producing CD4+ T cells there was no difference between the two cohorts. However, cells producing TNFα in response to long TDO peptides were more frequent in HD; for TDO118-137 this difference was highly significant (P < 0.0001). IL-10 and IL-17 production in response to peptide stimulation was restricted to cancer patients. Notably, for TDO303-322 these differences were statistically significant (P = 0.0051 and P < 0.0001, respectively).

Figure 5.

Natural CD4+ T-cell responses against TDO in healthy and cancer patients. T-cell responses against TDO118-137 (A, C, E, and G), or TDO303-322 (B, D, F, and H) was measured by IFNγ (A and B), TNFα (C and D), IL-17 (E and F) or IL-10 (G and H) ELISPOT. The average number of TDO-specific cells from triplicate experiments (after subtraction of background) was calculated per 5 × 105 PBMC for each patient. PBMC from 19 healthy individuals (HD), 21 cancer patients (Pt) (20 patients with MM and one BC) were analyzed. Only p-values (P < 0.05) by a Mann–Whitney test are revealed.

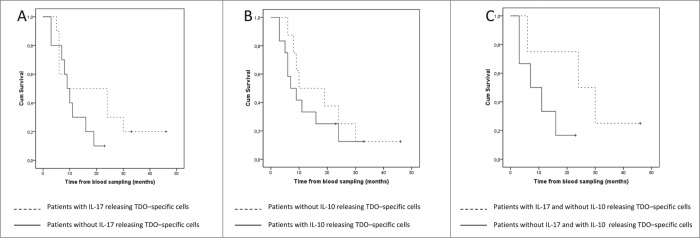

IL-17 and IL-10, which were only released in response to long TDO peptides by PBMCs obtained from cancer patients, exert profound immune modulating functions and have been implicated with the clinical course of cancer patients.22-24 Consequently, we correlated the frequency of CD4+ T cells producing IL-17A and IL-10 in response to the long TDO303-322 peptides with the clinical course of the MM patients, which revealed a clear impact of the presence of IL-17 and IL-10 producing cells on the OS: MM patients characterized by CD4+ cells releasing IL-17A had a trend toward an improved OS compared to the non-IL-17A responders (Fig. 6A); whereas MM patients with IL-10 releasing CD4+ T cell in response to the TDO peptides have an impaired OS (Fig. 6B). These OS difference was even more pronounced when MM patients harboring either IL-17+/IL-10- or IL-17-/IL-10+ producing T cells were compared. MM patients with the presence of cells producing 17+/IL-10- in response to TDO303-322 peptides had a much better survival, however, due to the limited patient number analyzed this difference was not significant (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6.

Clinical course of the examined MM patients. (A) Kaplan Meier estimate of OS defined as date of blood sample to date of death for MM patients with TDO303-322-specific IL-17-releasing T cells (dotted line) and for MM patients without TDO303-322-specific IL-17 T cells (solid line) (P = 0.178, log Rank). (B) Kaplan Meier estimate of OS defined as date of blood sample to date of death for MM patients with TDO303-322-specific IL-10-releasing T cells (solid line) and for MM patients without TDO303-322-specific IL-10 T cells (dotted line) (P = 0.423, log Rank). (C) Kaplan Meier estimate of OS defined as date of blood sample to date of death for MM patients with TDO303-322-specific IL-17-releasing T cells without IL-10 releasing cells (dotted line) and for MM patients with TDO303-322-specific IL-10 T cells without IL-17 releasing cells (solid line) (P = 0.124, log Rank).

The number, clinical course and treatment history of the MM patients included in the OS curves are given in supplementary Table S2. The IFNγ, TNFα, IL-10, and IL-17A responses are depicted for each individual patient in supplementary Fig. S5.

Discussion

We recently provided evidence for the concept of regulatory self-reactive T cells, which specifically recognize HLA-restricted epitopes derived from immune regulatory molecules such as IDO, hemo-oxygenase-1, or Foxp3.15,17 Here, we extend these observations to TDO as a target for natural T-cell responses, which were readily detectable both in cancer patients as well as in HD. Notably, TDO-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses were present in health and disease in the same frequency. Thus, HD apparently harbor strong immune responses against the self-protein TDO. Interestingly, however, TDO-specific CD4+ T cells differed in their functional characteristics in health and cancer. In HD TDO-specific CD4+ T cells released TNFα and IFNγ, but not the regulatory cytokines IL-17 or IL-10. In fact, TDO-specific CD4+ T cells producing TNFα were significantly more frequent in HD as compared to cancer patients.

CD8+ and CD4+ T cells are likely to exert immune regulatory functions by release of cytokines – or even by cytolysis – in response to epitopes derived from the immunosuppressive molecule TDO. Hence, both TDO-specific CD8+ and CD4+ T cells may play a role in the fine-tuning of the immune response by suppression of the immune permissive state induced by TDO-expressing cells. In cancer patients, however, the phenotype of the CD4+ TDO-reactive T cells was more complex: In addition to IFNγ and TNFα the cells also produced IL-17 and IL-10 in response to TDO epitopes. Production of IL-17 defines a subset of CD4+ T-helper cells (Th17 cells) involved in many pathologic situations including autoimmunity and cancer.25 Notably, Th17 cells have been attributed a protective role against cancer by promoting antitumor immunity.26 Tumor-infiltrating Th17 cells express other cytokines in addition to IL-17 such as IFNγ, IL-2, and TNF. Notably, some TDO-specific Th17 cells exhibit a similar effector T-cell cytokine profile. Moreover, we observed that MM patients hosting a TDO-specific IL-17 response showed a trend toward an improved OS.

On the other hand, we likewise observed in cancer patients the release of IL-10 in response to the TDO epitopes. IL-10 is an immunosuppressive cytokine, which is produced among other cells by Tregs. Tregs are important to maintain immune homeostasis and to insure tolerance to self-antigens.27 Thus, TDO-specific Tregs might enhance the TDO-mediated immune suppression and thereby boost cancer cells immune escape. Accordingly, MM patients with IL-10 producing, TDO-reactive CD4+ T cells showed a trend toward an impaired OS. The OS difference of MM patients harboring IL-17+/IL-10- or IL-17-/IL-10+ producing T cells in response to TDO peptides was highly pronounced, however due to the limited number of patients included in this comprehensive study this difference was not statistically significant.

The shift from Th1 toward a regulatory phenotype of TDO-specific T cells between healthy individuals and cancer patients may be caused by a conversion of Th1 T cells or an expansion of novel T-cell subsets in cancer patients. In some patients we were only detected IL-10 but not IFNγ or TNFα, in others patients, we observed Th1-like responses without release of IL-17 or IL-10 similar as to the HD. For most patients however, the response was mixed, hence, arguing toward an activation of different T cells or T cell plasticity, i.e. the ability to release both pro-inflammatory as well as regulatory cytokines.28 For further characterization, we expanded both CD4+ TDO-reactive T cells from cancer cells; these bulk cultures were either characterized by a Th1 or a Th1 and regulatory phenotype – an observation supporting the earlier notion.

Functional characterization of in vitro expanded CD8+ TDO-reactive T cells revealed that these killed HLA-matched tumor cells of different origin. However, not all T-cell lines killed the different cancer cell lines with variable efficacy. Hence, the processed and presented TDO-derived epitopes varied between cancers.

Cells expressing TCRs of low affinity toward HLA/peptide undergo positive selection in the thymus and develop into ‘normal’ CD4+ or CD8+ T cells. However, in recent years several distinct subpopulations of self-reactive lymphocytes have been described, which are not removed in the thymus.29 These cells are increasingly apportioned to immune regulation and immune homeostasis. Such, regulatory self-reactive lymphocytes include natural Tregs (nTregs) and natural Th17 (nTh17) cells. The fact that TDO-reactive T cells recognizing several different TDO epitopes are present in healthy individuals suggest that such self-reactive T cells may similarly avoid deletion in the thymus. This is supported by our previous observation of IDO-reactive T cells in peripheral blood of both cancer patients and healthy individuals. These IDO-specific T cells were able to recognize and kill tumor cells as well as IDO-expressing immune cells.15 An important difference between IDO- and TDO-specific immunity, however, is that the latter much more frequent in HD whereas IDO-specific T cells are rare in healthy individuals.15,30 Moreover, the TDO-specific T cell responses have different functional phenotypes in health and disease. Taken together, the here presented data add important new aspects to the concept of regulatory self-reactive T cells.15,17,18

Materials and Methods

Patients

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were collected from patients with MM, BC, and HD. For cancer patients there was an at least 4 week interval between blood draws and any kind of anticancer therapy. In Table S1, the characteristics of the included patients are depicted. PBMCs were isolated using Lymphoprep separation, HLA-typed (Department of Clinical Immunology, University Hospital, Copenhagen, Denmark), and frozen in fetal calf serum (FCS) (Gibco, Naerum, Denmark) with 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (Sigma-Aldrich, Brøndby, Denmark). Written informed consent from the patients was obtained before any of these measures. The protocol was approved by the scientific ethics committee for the Capital Region of Denmark and conducted in accordance with the provisions of the declaration of Helsinki. HD PBMCs were obtained from the State Hospital blood bank.

Tumor cell lines

Cell lines FM-55M1 and FM-86 were provided from EST-DAB (http://www.medizin.uni-tuebingen.de/estdab/), A2058 and MDA-MB 231 were obtained from ATCC (www.ATCC.org), UKE-1 31 was a kind gift from W. Fiedler (University Hospital of Eppedorf, Hamburg, Germany). All cell lines were maintained in RPMI 1640 (Gibco) supplied with 10% FCS (Gibco).

Peptides

The TDO amino acid sequence was screened by the use of possible epitopes restricted to HLA-A2. Fifteen peptides were selected, synthesized by TAG Copenhagen (Copenhagen, Denmark). Once lyophilized peptides were dissolved in water or DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich) according to the recommendation of the manufacturer, they were stored at ˗20ºC in aliquots avoiding freeze-thaw cycles. The peptides were TDO40-48 (LIYGNYLHL), TDO65-74 (KIHDEHLFII), TDO72-81 (FIITHQAYEL), TDO85-93 (QILWELDSV), TDO123-132 (KLLVQQFSIL), TDO130-138 (SILETMTAL), TDO159-168 (RLLENKIGVL), TDO192-201 (LLKSEQEKTL), TDO200-208 (TLLELVEAWL), TDO225-234 (KLEKNITRGL), TDO276-284 (LLSKGERRL), TDO309-317 (QLLTSLMDI), TDO364-372 (DLFNLSTYL), TDO372-381 (LIPRHWIPKM), and TDO380-389 (KMNPTIHKFL). For negative and positive controls, the HIV derived peptide HIVpol468-476 (ILKEPVHGV) and the CMV pp65495-503 (NLVPMVATV) were used, respectively. Additionally, longer peptides (20 amino acids) comprising TDO123-132 and TDO309-317, respectively, were synthesized. These were named TDO118-137 (VSVILKLLVQQFSILETMTA) and TDO303-322 (RFQVPFQLLTSLMDIDSLMT) and both included several potential class II-restricted epitopes as suggested by the predictive algorithm SYFPEITHI.32

HLA peptide exchange technology and MHC ELISA

The HLA-peptide affinity was measured by a UV exchange method in combination with a sandwich ELISA as previously described.20 In short, HLA-A2 light and heavy chains were produced in E. coli and refolded with a UV-sensitive ligand. This conditional ligand was cleaved upon 1 h of UV light exposure and substituted with the peptide of interest. After adding the HLA-A2-peptide complex to an ELISA, the affinity of the complex was measured as the absorbance. Two peptides with well described high affinity toward HLA-A2 (HIVpol468-476 and CMV pp65495-503) were used as positive control peptides, while a sample without substitution peptide was used as a negative control. Positive controls were made in quadruplicates and TDO peptides in triplicates.

ELISPOT assay

In the present study the ELISPOT was performed according to the guidelines provided by CIP (http://cimt.eu/cimt/files/dl/cip_guidelines.pdf). The ELISPOT assay was used to quantify peptide epitope specific effector cells that release cytokines (IFNγ, TNFα, IL-17A or IL-10) as described previously.15,33 In some experiments, PBMCs were stimulated once in vitro with peptide prior to analysis. In some experiments, 104 autologous DCs were added to the wells as antigen presenting cells. The spots were counted using the ImmunoSpot Series 2.0 Analyzer (C.T.L.-Europe, Bonn, Germany). In some experiments, CD4+ cells were isolated by EasySep human CD4+ T cell enrichment kit (Stem Cell technologies, Grenoble, France) following manufacturers’ instructions. This yielded highly pure cultures (>97% CD4+), which was confirmed by staining with surface antibodies as described below for ICS and flow cytometry (FCM).

Definition of an ELISPOT response was based on the guidelines provided by the CIP panel as well as Moodie et al. 34 using either an empirical or statistical approach. The empirical approach is based on the ‘signal-to-noise’ ratio and suggests that the threshold for response definition should be defined as >6 specific spots per 105 PBMCs. In the Fig. 6 we have increased this to >40 specific spots per 5 × 105 PBMCs. The non-parametric DFR method allows statistical comparison of antigen-stimulated wells and negative control wells as exemplified in Fig. S2. The release of a given cytokine in response to TDO118-137 or TDO303-322 was compared between patient and healthy donor groups by a Mann–Whitney test. P-values <0.05 were considered significant.

Generation of TDO specific T cell lines

DC were generated by adherence of PBMCs to the plastic surface of a well for 1 h in RPMI 1640 (Gibco) before removal of non-adherent cells. The adherent cells were treated with 1,000 U/mL GM-CSF (PeproTech, London, UK) and 250 U/mL IL-4 (Peprotech) in ex-vivo 15 (Lonza, Copenhagen, Denmark) supplied with 5% human AB serum (Sigma-Aldrich) and placed in a 37°C, 5% CO2 and humidified environment. On day six, maturation cocktail consisting of 1,000 U/mL of each TNFα, IL-1β and IL-6 and 1 μg/mL PGE2 (Peprotech) was added to the cells. On day eight, mature DCs were harvested, loaded with 100 μM TDO peptide in ex-vivo 15 (Lonza) for 4 h in the incubator. After washing, peptide-loaded DCs were mixed with autologous PBLs in ex-vivo 15 (Lonza) supplied with 5% human AB serum (Sigma-Aldrich). The next day, IL-12 and IL-7 (Peprotech) were added to final concentrations of 20 and 40 U/mL, respectively. Cultures were stimulated this way twice 7 d apart. Further stimulations were performed using autologous, irradiated (25 Gy) PBLs loaded with 100 μM TDO peptide. The day after stimulation with PBLs the cultures were supplied with IL-2 (Proleukin; Novartis, Copenhagen, Denmark) to a final concentration of 40 U/mL.

FCM and cell sorting

Peptide loaded MHC tetramers were produced as described elsewhere.35 No more than 2 × 106 T cells were stained with 2.5 μL of each phycoerytrhin (PE) and allophycocyanin (APC) conjugated tetramers loaded with either a TDO peptide or the HIVpol468-476 peptide as a negative control. The stainings were performed in 50 μL PBS (Lonza) supplied with 2% FCS (Gibco) for 15 min in the incubator. Then an antibody mix consisting of αCD3-AmCyan, αCD4-Fitc (BD Bioscience, Albertslund, Denmark), αCD8-Pacific Blue (DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark) and the near IR Dead Cell Stain Kit (Life technologies, Naerum, Denmark) was added directly and the cells placed at 4°C in the dark for 30 min. After washing in PBS (Lonza) supplied with 2% FCS (Gibco), tetramer positive CD8+ cells were sorted by FACS Aria (BD Biosciences).

TDO-specific CD4+ T cells were stimulated with 5 μM TDO303-322 in ex-vivo 15 medium (Lonza) and IFNγ secreting cells were detected using MACS IFNγ secretion assay-detection kit (PE) (Miltenyi Biotec, Lund, Sweden). PE positive cells were subsequently sorted into 104 autologous, irradiated (30 Gy) PBMC by a FACS Aria (BD Biosciences).

Rapid expansion protocol (REP)

The rapid expansion of sorted specific T cells was performed as follows: Cells were rested in ex-vivo 15 (Lonza) supplemented with 5% human serum (Sigma-Aldrich) and 6,000 U/mL IL-2 (proleukin; Novartis) over night at 5% CO2 at 37°C. The next day, feeder cells were prepared: a total of 20 × 106 PBLs from three HD were irradiated (25 Gy), washed and mixed in a ratio of 1:1:1 in 2 mL ex-vivo 15 (Lonza) containing 5% human serum (Sigma-Aldrich). After 2 h, sample cells were mixed with the feeder cells and IL-2 (Novartis) was added to a final concentration of 6,000 U/mL along with αCD3 ab OKT3 (ebioscience, Frankfurt, Germany) to a final concentration of 30 ng/mL in 20 mL medium. Every 3–4 d, cell numbers were adjusted to a maximum of 5 × 105 cells/mL and fresh IL-2 (Novartis) was added to 6,000 U/mL.

Cytokine stainings by FCM

PBMCs were stimulated with 5 μM relevant peptide or control peptide in the presence of GolgiPlug (diluted 1:1,000, BD Biosciences) for 5 h in the incubator. Then, cells were washed twice in PBS (Lonza) supplied with 2% FCS (Gibco) and stained with surface antibodies as described for cell sorting. After washing of cells in PBS (Lonza) with of 2% FCS (Gibco), cells were fixed and permeabilized with fixation/permebilization buffer (ebioscience) for at least 30 min, washed twice and then stained with antibodies specific for IFNγ-PE (BD Biosciences) and TNFα-APC (ebioscience). At least 50,000 CD4+ T cells were recorded on a FACS Canto II flow cytometer and data were analyzed with the Diva software package (BD Biosciences).

Cytotoxicity assay

Assessment of the cytotoxic capability of the generated T-cell lines was evaluated using a conventional chromium release assay as described.36 Briefly, target tumor cell lines were labeled with 100 μCi 51Cr (Perkin Elmer, Skovlunde, Denmark) in 100 μL RPMI 1640 (Gibco) supplied with 10% FCS (Gibco) for 1 h at 37°C. After washing of target cells, they were incubated with effector cells at different effector:target (E:T) ratios for 4 h in the incubator. Subsequently, the amount of radioactivity in the supernatant was measured using a gamma cell counter (Perkin Elmer Wallac Wizard 1470 Automatic gamma counter).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank Merete Jonassen and Tina Seremet for excellent technical assistance. Likewise, Tobias Wirenfeldt Klausen provided valuable assistance in regards to statistics.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Funding

The study was supported by Herlev Hospital, and Danish Cancer Society. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher's website.

References

- 1. Muller A, Heseler K, Schmidt SK, Spekker K, Mackenzie CR, Daubener W. The missing link between indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase mediated antibacterial and immunoregulatory effects. J Cell Mol Med 2009; 13:1125-35; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00542.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Prendergast GC, Smith C, Thomas S, Mandik-Nayak L, Laury-Kleintop L, Metz R, Muller AJ. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase pathways of pathogenic inflammation and immune escape in cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2014; 63:721-35; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00262-014-1549-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhang Y, Kang SA, Mukherjee T, Bale S, Crane BR, Begley TP, Ealick SE. Crystal structure and mechanism of tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase, a heme enzyme involved in tryptophan catabolism and in quinolinate biosynthesis. Biochemistry 2007; 46:145-55; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1021/bi0620095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Batabyal D, Yeh SR. Human tryptophan dioxygenase: a comparison to indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. J Am Chem Soc 2007; 19:15690-701; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1021/ja076186k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Munn DH, Mellor AL. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase and tumor-induced tolerance. J Clin Invest 2007; 117:1147-54; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1172/JCI31178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Munn DH, Sharma MD, Baban B, Harding HP, Zhang Y, Ron D, Mellor AL. GCN2 kinase in T cells mediates proliferative arrest and anergy induction in response to indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. Immunity 2005; 22:633-42; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Opitz CA, Litzenburger UM, Sahm F, Ott M, Tritschler I, Trump S, Schumacher T, Jestaedt L, Schrenk D, Weller M, et al. An endogenous tumour-promoting ligand of the human aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Nature 2011; 478:197-203; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature10491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Prendergast GC. Immune escape as a fundamental trait of cancer: focus on IDO. Oncogene 2008; 27:3889-900; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/onc.2008.35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Prendergast GC, Metz R, Muller AJ. IDO recruits Tregs in melanoma. Cell Cycle 2009; 8:1818-9; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/cc.8.12.8887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Uyttenhove C, Pilotte L, Theate I, Stroobant V, Colau D, Parmentier N, Boon T, Van den Eynde BJ. Evidence for a tumoral immune resistance mechanism based on tryptophan degradation by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. Nat Med 2003; 9:1269-74; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nm934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Metz R, DuHadaway JB, Rust S, Munn DH, Muller AJ, Mautino M, Prendergast GC. Zinc protoporphyrin IX stimulates tumor immunity by disrupting the immunosuppressive enzyme indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. Mol Cancer Ther 2010; 9:1864-71; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Iversen TZ, Engell-Noerregaard L, Ellebaek E, Andersen R, Larsen SK, Bjoern J, Zeyher C, Gouttefangeas C, Thomsen BM, Holm B, et al. Long-lasting disease stabilization in the absence of toxicity in metastatic lung cancer patients vaccinated with an epitope derived from indoleamine 2,3 dioxygenase. Clin Cancer Res 2014; 20:221-32; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-1560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pilotte L, Larrieu P, Stroobant V, Colau D, Dolusic E, Frederick R, De Plaen E, Uyttenhove C, Wouters J, Masereel B, et al. Reversal of tumoral immune resistance by inhibition of tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012; 109:2497-502; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1113873109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sorensen RB, Berge-Hansen L, Junker N, Hansen CA, Hadrup SR, Schumacher TN, De Plaen E, Uyttenhove C, Wouters J, Masereel B, et al. The immune system strikes back: cellular immune responses against indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. PLoS One 2009; 4:e6910; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0006910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sorensen RB, Hadrup SR, Svane IM, Hjortso MC, thor Straten P, Andersen MH. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase specific, cytotoxic T cells as immune regulators. Blood 2011; 117:2200-10; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1182/blood-2010-06-288498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sorensen RB, Kollgaard T, Andersen RS, van den Berg JH, Svane IM, thor Straten P, Andersen MH. Spontaneous cytotoxic T-Cell reactivity against indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase-2. Cancer Res 2011; 71:2038-44; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Becker JC, Thor SP, Andersen MH. Self-reactive T cells: suppressing the suppressors. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2014; 63:313-9; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00262-013-1512-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Andersen MH. The targeting of immunosuppressive mechanisms in hematological malignancies. Leukemia 2014; 28:1784-92; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/leu.2014.108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Altman JD, Moss PA, Goulder PJR, Barouch DH, McHeyzer Williams MG, Bell JI, McMichael AJ, Davis MM. Phenotypic analysis of antigen-specific T lymphocytes. Science 1996; 274:94-6; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.274.5284.94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Toebes M, Coccoris M, Bins A, Rodenko B, Gomez R, Nieuwkoop NJ, van de Kasteele W, Rimmelzwaan GF, Haanen JB, Ovaa H, et al. Design and use of conditional MHC class I ligands. Nat Med 2006; 12:246-51; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nm1360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bennett SR, Carbone FR, Karamalis F, Flavell RA, Miller JF, Heath WR. Help for cytotoxic-T-cell responses is mediated by CD40 signalling. Nature 1998; 393:478-80; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/30996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Stewart CA, Metheny H, Iida N, Smith L, Hanson M, Steinhagen F, Leighty RM, Roers A, Karp CL, Müller W, et al. Interferon-dependent IL-10 production by Tregs limits tumor Th17 inflammation. J Clin Invest 2013; 123:4859-74; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1172/JCI65180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Grivennikov SI, Wang K, Mucida D, Stewart CA, Schnabl B, Jauch D, Taniguchi K, Yu GY, Osterreicher CH, Hung KE, et al. Adenoma-linked barrier defects and microbial products drive IL-23IL-17-mediated tumour growth. Nature 2012; 491:254-8; PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sung WW, Wang YC, Lin PL, Cheng YW, Chen CY, Wu TC, Lee H. IL-10 promotes tumor aggressiveness via upregulation of CIP2A transcription in lung adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2013; 19:4092-103; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chen Z, O’Shea JJ. Th17 cells: a new fate for differentiating helper T cells. Immunol Res 2008; 41:87-102; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s12026-007-8014-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zou W, Restifo NP. T(H)17 cells in tumour immunity and immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol 2010; 10:248-56; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nri2742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sakaguchi S. Regulatory T cells. Springer Semin Immunopathol 2006; 28:1-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sundrud MS, Trivigno C. Identity crisis of Th17 cells: many forms, many functions, many questions. Semin Immunol 2013; 25:263-72; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.smim.2013.10.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Stritesky GL, Jameson SC, Hogquist KA. Selection of self-reactive T cells in the thymus. Annu Rev Immunol 2012; 30:95-114; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Munir S, Larsen SK, Iversen TZ, Donia M, Klausen TW, Svane IM, Straten PT, Andersen MH. Natural CD4(+) T-cell responses against indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. PLoS One 2012; 7:e34568; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0034568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Quentmeier H, MacLeod RA, Zaborski M, Drexler HG. JAK2 V617F tyrosine kinase mutation in cell lines derived from myeloproliferative disorders. Leukemia 2006; 20:471-6; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.leu.2404081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rammensee HG, Falk K, Roetzschke O. MHC molecules as peptide receptors. Curr Biol 1995; 5:35-44; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0960-9822(95)00011-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Andersen MH, Pedersen LO, Becker JC, thor Straten P. Identification of a cytotoxic T lymphocyte response to the apoptose inhibitor protein surviving in cancer patients. Cancer Res 2001; 61:869-72; PMID: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Moodie Z, Price L, Janetzki S, Britten CM. Response determination criteria for ELISPOT: toward a standard that can be applied across laboratories. Methods Mol Biol 2012; 792:185-96; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/978-1-61779-325-7_15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hadrup SR, Bakker AH, Shu CJ, Andersen RS, van Veluw J, Hombrink P, Castermans E, Thor Straten P, Blank C, Haanen JB, et al. Parallel detection of antigen-specific T-cell responses by multidimensional encoding of MHC multimers. Nat Methods 2009; 6:520-6; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nmeth.1345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Andersen MH, Sorensen RB, Brimnes MK, Svane IM, Becker JC, thor Straten P. Identification of heme oxygenase-1-specific regulatory CD8+ T cells in cancer patients. J Clin Invest 2009; 119:2245-56; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1172/JCI38739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.