Abstract

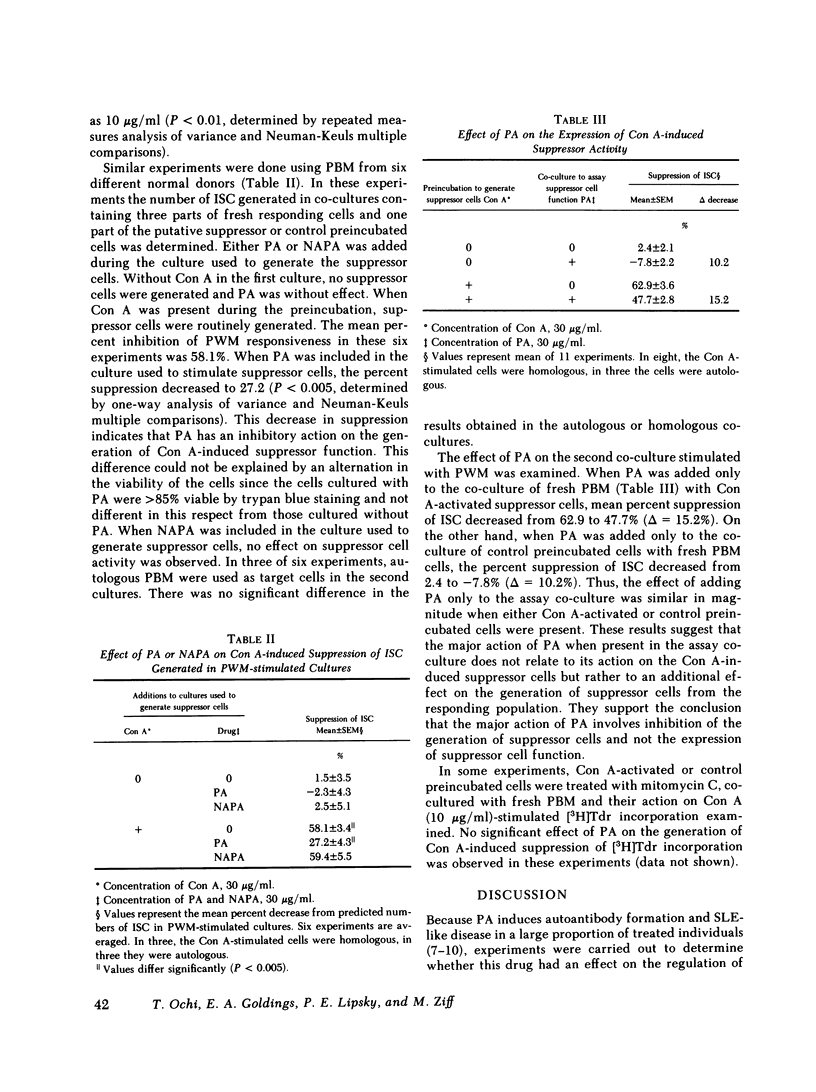

Procainamide (PA) induces the production of a number of autoantibodies in a high proportion of treated individuals and in some a syndrome closely resembling systemic lupus erythematosus. The mechanism underlying this action of PA is unclear. To examine the possibility that PA might induce autoantibody formation by altering normal immunoregulatory mechanisms, the action of this drug on an in vitro model of antibody formation in man was examined. PA was found to augment the generation of immunoglobulin-secreting cells (ISC) from human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBM) in response to pokeweed mitogen but had no effect on pokeweed mitogen-induced tritiated thymidine incorporation. When purified populations of B and T cells were used, PA enhanced the generation of ISC in B-cell cultures supported by untreated T cells but not by T cells treated with mitomycin C. These results indicate that PA augmented B-cell responses by inhibiting suppressor T-cell activity and not by augmenting helper T-cell or B-cell function. N-Acetyl-procainamide had no effect on the generation of ISC in this system. The effect of PA on concanavalin A (Con A)-induced suppressor cell activity was also examined to determine whether PA altered the generation or expression of suppressor T-cell function. PBM were cultured with 30 microgram/ml of Con A for 48 h to generate suppressor cells. When these were co-cultured with fresh PBM, the number of ISC generated was decreased by 58.1 +/- 3.4% (mean +/- SEM, n = 6). Cells that had been similarly incubated without Con A were not inhibitory. The addition of PA to the Con A-stimulated cultures inhibited the generation of suppressor cells as indicated by the fact that the response of fresh cells co-cultured with the Con A-stimulated cells was diminished by only 27.2 +/- 4.3%. In this system too, N-acetyl-procaimamide had no effect. By contrast, adding PA only to the co-culture of Con A-stimulated cells with fresh PBM had a less marked effect on suppressor cell function. These results indicate that the major action of PA is to inhibit the generation of suppressor T-cell activity. Such an effect may explain the capacity of this agent to induce autoantibody formation in treated individuals.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Batchelor J. R., Welsh K. I., Tinoco R. M., Dollery C. T., Hughes G. R., Bernstein R., Ryan P., Naish P. F., Aber G. M., Bing R. F. Hydralazine-induced systemic lupus erythematosus: influence of HLA-DR and sex on susceptibility. Lancet. 1980 May 24;1(8178):1107–1109. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(80)91554-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blomgren S. E., Condemi J. J., Bignall M. C., Vaughan J. H. Antinuclear antibody induced by procainamide. A prospective study. N Engl J Med. 1969 Jul 10;281(2):64–66. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196907102810203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blomgren S. E., Condemi J. J., Vaughan J. H. Procainamide-induced lupus erythematosus. Clinical and laboratory observations. Am J Med. 1972 Mar;52(3):338–348. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(72)90021-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bluestein H. G., Redelman D., Zvaifler N. J. Procainamide-lymphocyte reactions. A possible explanation for drug-induced autoimmunity. Arthritis Rheum. 1981 Aug;24(8):1019–1023. doi: 10.1002/art.1780240807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bluestein H. G., Zvaifler N. J., Weisman M. H., Shapiro R. F. Lymphocyte alteration by procainamide: relation to drug-induced lupus erythematosus syndrome. Lancet. 1979 Oct 20;2(8147):816–819. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(79)92174-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritzler M. J., Tan E. M. Antibodies to histones in drug-induced and idiopathic lupus erythematosus. J Clin Invest. 1978 Sep;62(3):560–567. doi: 10.1172/JCI109161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galili U., Schlesinger M. The formation of stable E rosettes after neuraminidase treatment of either human peripheral blood lymphocytes or of sheep red blood cells. J Immunol. 1974 May;112(5):1628–1634. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giardina E. G., Heissenbuttel R. H., Bigger J. T., Jr Intermittent intravenous procaine amide to treat ventricular arrhythmias. Correlation of plasma concentration with effect on arrhythmia, electrocardiogram, and blood pressure. Ann Intern Med. 1973 Feb;78(2):183–193. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-78-2-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsburg W. W., Finkelman F. D., Lipsky P. E. Circulating and mitogen-induced immunoglobulin-secreting cells in human peripheral blood: evaluation by a modified reverse hemolytic plaque assay. J Immunol. 1978 Jan;120(1):33–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold E. F., Ben-Efraim S., Faivisewitz A., Steiner Z., Klajman A. Experimental studies on the mechanism of induction of anti-nuclear antibodies by procainamide. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1977 Mar;7(2):176–186. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(77)90046-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenspan A. M., Horowitz L. N., Spielman S. R., Josephson M. E. Large dose procainamide therapy for ventricular tachyarrhythmia. Am J Cardiol. 1980 Sep;46(3):453–462. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(80)90015-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henningsen N. C., Cederberg A., Hanson A., Johansson B. W. Effects of long-term treatment with procaine amide. A prospective study with special regard to ANF and SLE in fast and slow acetylators. Acta Med Scand. 1975 Dec;198(6):475–482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirtland H. H., 3rd, Mohler D. N., Horwitz D. A. Methyldopa inhibition of suppressor-lymphocyte function: a proposed cause of autoimmune hemolytic anemia. N Engl J Med. 1980 Apr 10;302(15):825–832. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198004103021502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kluger J., Drayer D. E., Reidenberg M. M., Lahita R. Acetylprocainamide therapy in patients with previous procainamide-induced lupus syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1981 Jul;95(1):18–23. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-95-1-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosowsky B. D., Taylor J., Lown B., Ritchie R. F. Long-term use of procaine amide following acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1973 Jun;47(6):1204–1210. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.47.6.1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsky P. E. Staphylococcal protein A, a T cell-regulated polyclonal activator of human B cells. J Immunol. 1980 Jul;125(1):155–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsky P. E., Ziff M. Inhibition of antigen- and mitogen-induced human lymphocyte proliferation by gold compounds. J Clin Invest. 1977 Mar;59(3):455–466. doi: 10.1172/JCI108660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsky P. E., Ziff M. Inhibition of human helper T cell function in vitro by D-penicillamine and CuSO4. J Clin Invest. 1980 May;65(5):1069–1076. doi: 10.1172/JCI109759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina J., Dubois E. L., Bilitch M., Bland S. L., Friou G. J. Procainamide-induced serologic changes in asymptomatic patients. Arthritis Rheum. 1969 Dec;12(6):608–614. doi: 10.1002/art.1780120608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry H. M., Jr, Chaplin H., Jr, Carmody S., Haynes C., Frei C. Immunologic findings in patients receiving methyldopa: a prospective study. J Lab Clin Med. 1971 Dec;78(6):905–917. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich R. R., Pierce C. W. Biological expressions of lymphocyte activation. II. Generation of a population of thymus-derived suppressor lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1973 Mar 1;137(3):649–659. doi: 10.1084/jem.137.3.649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg S. A., Lipsky P. E. Monocyte dependence of pokeweed mitogen-induced differentiation of immunoglobulin-secreting cells from human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Immunol. 1979 Mar;122(3):926–931. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoen R. T., Trentham D. E. Drug-induced lupus: an adjuvant disease? Am J Med. 1981 Jul;71(1):5–8. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(81)90250-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegal F. P., Siegal M. Enhancement by irradiated T cells of human plasma cell production: dissection of helper and suppressor functions in vitro. J Immunol. 1977 Feb;118(2):642–647. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan E. M. Drug-induced autoimmune disease. Fed Proc. 1974 Aug;33(8):1894–1897. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tannen R. H., Weber W. W. Antinuclear antibodies related to acetylator phenotype in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1980 Jun;213(3):485–490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittingham S., Mackay I. R., Whitworth J. A., Sloman G. Antinuclear antibody response to procainamide in man and laboratory animals. Am Heart J. 1972 Aug;84(2):228–234. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(72)90337-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winfield J. B., Koffler D., Kunkel H. G. Development of antibodies to ribonucleoprotein following short-term therapy with procainamide. Arthritis Rheum. 1975 Nov-Dec;18(6):531–534. doi: 10.1002/art.1780180601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woosley R. L., Drayer D. E., Reidenberg M. M., Nies A. S., Carr K., Oates J. A. Effect of acetylator phenotype on the rate at which procainamide induces antinuclear antibodies and the lupus syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1978 May 25;298(21):1157–1159. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197805252982101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]