Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Tumor size is a known prognostic factor for early stage non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), but its significance in node-positive and locally invasive NSCLC has not been extensively characterized. We queried the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database to evaluate the prognostic value of tumor size for early stage as well as node-positive and locally invasive NSCLC.

METHODS

Patients in SEER registry with NSCLC diagnosed between 1998 and 2003 were analyzed. Tumor size was analyzed as a continuous variable. Other demographic variables included age, gender, race, histology, primary tumor extension, node status and primary treatment modality (surgery vs radiation). The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate overall survival (OS). Cox proportional hazard model was used to evaluate whether tumor size was an independent prognostic factor.

RESULTS

52,287 eligible patients were subgrouped based on tumor extension and node status. Tumor size had a significant effect on OS in all subgroups defined by tumor extension or node status. In addition, tumor size also had statistically significant effect on OS in 15 of 16 subgroups defined by tumor extension and nodal status after adjustment for other clinical variables. Our model incorporating tumor size had significantly better predictive accuracy than our alternative model without tumor size.

CONCLUSIONS

Tumor size is an independent prognostic factor, for early stage as well as node positive and locally invasive disease. Prediction tools, such as nomograms, incorporating more detailed information not captured in detail by the routine TNM classification, may improve prediction accuracy of OS in NSCLC.

Keywords: Non-small cell lung cancer, Tumor Size, Survival, SEER

Introduction

Tumor size is a known prognostic factor for many cancers including non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with larger tumors predicting a worse prognosis in most cases.1 This is true especially for node-negative tumors, where tumor size is often the main determinant of stage and treatment. In the most recent 7th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system for lung cancer, tumor size is emphasized, especially for early stage NSCLC.2–7 In this updated classification system, additional size cutoffs were introduced, with T1 and T2 tumors divided into subcategories T1a, T1b, T2a, and T2b (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 1, size-based changes of tumor classification between 6th and 7th TNM). In addition, larger (>7cm) tumors were upgraded from T2 in the 6th edition TNM system to T3 in the 7th TNM system. Overall staging was changed as well. In the prior staging system, any node negative cancer that was greater than 3 cm in diameter was considered stage IB (T2N0M0). Now, tumors between 3 cm and 5 cm (T2a) are still considered stage IB, but node-negative tumors between 5 and 7 cm (T2b) are stage IIA and above 7 cm (T3) are stage IIB (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 2, changes of staging in 7th TNM system due to tumor size changes). These changes in staging emphasize the poorer prognosis for patients presenting with larger primary tumors.

Although the prognostic significance of tumor size for early stage NSCLCs was recognized, its significance in node positive and locally invasive NSCLC has not been as well validated. Our hypothesis is that tumor size is useful for prognostication even in patients with locally invasive tumors or with lymph node involvement. To test this hypothesis, we performed an analysis to determine the relationship between the tumor size and survival using SEER database, and created an easy-to-use, readily applicable nomogram to predict overall survival in routine clinical practice, incorporating tumor size as a continuous variable.

Methods

This was a retrospective, population-based study using cases registered in the SEER database made publicly available through online access. Data was retrieved using the Surveillance Research Program, National Cancer Institute SEER*Stat software (seer.cancer.gov/seerstat) version 6.3.6. Informed consent from the study population was not deemed necessary, as the authors had no access to the identities of the patients.

Data collection

The following database was used for selection of cases: Incidence – SEER 17 Regs Public-Use, Nov 2005 Sub (1973–2003 varying) – Linked to County Attributes – Total U.S., 1969–2003 Counties, National Cancer Institute, Cancer Control and Population Sciences (DCCPS), Surveillance Research Porgram, Cancer Statistics Branch, released April 2006, based on the November 2005 submission. Cases classified as tumors of the lung and bronchus, diagnosed between 1998 and 2003, with age 18 to 115 at diagnosis were included in the analysis. Only patients with the following histologies (based on International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, 3rd Edition [ICD-O-3] codes) were included: large cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, bronchioalveolar carcinoma, and carcinoma not otherwise specified. Cases identified by means of a death certificate only or autopsy only were excluded. Additionally, cases were required to have sufficient information on the size and the extension of the primary tumor as well as involved lymph nodes. Individual data for each case was retrieved from the database regarding gender, age at diagnosis, race, tumor size, extension, nodal status, the primary treatment modality (surgery and/or radiotherapy), survival time, and vital status at last follow-up.

Subgroup definitions

Primary tumor size in the SEER database is recorded according to the following rank order: 1) tumor size from the pathology report is used if it is available and when the patient has not received radiation or systemic treatment prior to surgery; 2) if the patient receives pre-operative systemic therapy (chemotherapy, hormone therapy, immunotherapy) or radiation therapy, the largest tumor size is used, whether prior to or following treatment; 3) information on tumor size from imaging/radiographic techniques is used when there is no more specific size information from a pathology or operative report. If there is a difference in reported tumor size among imaging and radiographic techniques, the largest tumor size reported in the record is used.8

Record of lymph node status is recorded in the following rank order: 1) the farthest specific regional lymph node chain that is involved either clinically or pathologically is used; 2) involved regional lymph nodes from the pathology report is used, if it is available, when the patient receives no radiation or systemic treatment prior to surgery; 3) if there is a discrepancy between clinical information and pathologic information about the same lymph nodes, the pathologic information takes precedence; 4) if the patient receives preoperative systemic therapy (chemotherapy, hormone therapy, immunotherapy) or radiation therapy, the farthest involved regional lymph nodes are used, whether this is based on information prior to surgery or following treatment.9 Based on the nodal status, patients were grouped into N0 (no lymph node involvement, EOD 10 nodal code 0), N1 (involvement of ipsilateral intrapulmonary, hilar, or peribronchial nodes, nodal code 1), N2 (involvement of ipsilateral subcarinal, carinal, mediastinal, peri/paratracheal, pre/retro-tracheal, peri/paraesophageal, aortic, pulmonary ligament, or pericardial lymph nodes, nodal code 2), or N3 (involvement of contralateral hilar or medistinal lymph nodes, supraclavicular lymph nodes, or scalene lymph nodes, nodal code 3) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Grouping by tumor extension and nodal involvement (N=number of patients)

| Node Group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| N0 | N1 | N2 | N3 | ||

| Extension Group | E1 | 1 (N=21930) | 5 (N=2642) | 9 (N=5410) | 13 (N=694) |

| E2 | 2 (N=6853) | 6 (N=1702) | 10 (N=2873) | 14 (N=295) | |

| E3 | 3 (N=2265) | 7 (N=557) | 11 (N=1636) | 15 (N=213) | |

| E4 | 4 (N=1340) | 8 (N=409) | 12 (N=3002) | 16 (N=466) | |

Abbreviations:

E1: tumor confined to one lung (extension code 10)

E2: tumor involving pleura or main stem bronchus ≥ 2 cm from carina (extension codes 20/40)

E3: tumor involving chest wall or main stem bronchus < 2 cm from carina (extension codes 50/60/73)

E4: tumor invading mediastinum (extension code 70)

N0: no evidence of regional lymph node metastasis

N1: metastasis to ipsilateral peribronchial and/or ipsilateral hilar lymph nodes

N2: metastasis to ipsilateral mediastinal and/or subcarinal lymph nodes

N3: metastasis to contralateral mediastinal, contralateral hilar, or ipsilateral and/or contralateral supraclavicular or scalene lymph nodes

Definition of disease extension was based on the SEER Extension of Disease coding system (EOD 10). Extension was classified as confined to one lung (EOD 10 extension code 10), involving the mainstem bronchus > 2 cm from the carina (extension code 20), involving the visceral pleura (extension code 40), involving the bronchus < 2cm from carina (extension code 50), involving the chest wall, pericardium, or parietal pleura (extension code 60), extension to a rib (extension code 73), or mediastinal extension (extension code 70). Patients were further grouped into four groups based on the extension: E1 (extension code = 10), E2 (extension codes =20/40), E3 (extension codes = 50/60/73) and E4 (extension code = 70) (Table 1).

Patients with satellite nodules in the same lobe (EOD 10 extension code 65) or in a different ipsilateral lobe (EOD 10 extension code 77), extra-pulmonary metastases (extension code 85), patients with distant lymph node metastases (nodal code 7) and patients with tumor size greater than 40 cm were excluded from the analysis. Patients were then divided into 16 subgroups based on extension and nodal status (Table 1).

Statistical analysis

The distribution of OS, defined as the time from diagnosis of lung cancer to death of any cause, was estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method. For each of the 16 subgroups, we analyzed OS as a function of tumor size. Tumor size was analyzed as a continuous variable in the transformation of logarithm to the base 2. Other demographic variables included age, gender, race, histology, primary tumor extension, node status and primary treatment modality (surgery vs radiation vs both vs neither). Log-rank test was performed to assess for differences in survival between subgroups. Cox proportional hazard model was used to evaluate the effects of multiple variables on survival. P-values less than 0.05 for main effects and interaction effects were considered statistically significant. All tests were two-sided.

The predictive accuracy of various Cox regression models was quantified by C-index, which provides the area under the receiver operating characteristics curve for censored data.10,11 A C-index of 0.5 indicates that outcomes are completely random, whereas a C-index of 1 indicates that the model is a perfect predictor. To protect against overfitting during stepwise regression, we used a bootstrap procedure as implemented in the “validate” function of the Design library,11 which allows for computation of an unbiased estimate of the C-index. We used 100 bootstrap samples. To study whether tumor size added predictive information above and beyond other important clinical/pathological covariates, we used the rcorrp.cens function in the Design library in R to test whether the difference in statistical predictive accuracy between Cox regression models was significant.10 This function computes U-statistics for testing whether the predictions of one model are more concordant than those of another model.

Nomogram development

A nomogram of the final multivariate model was constructed as a visualizing aid to obtain predicted values manually from a Cox model. Calibration was carried out for the constructed nomogram. To adjust for the bias associated with evaluating the performance of the nomogram on the same group of patients that was used to build the nomogram, the assessment of calibration was repeated for 5000 bootstrapped samples.

Results

Patient characteristics

Based on the patient selection criteria described above, 52,287 patients with NSCLC were identified from the SEER database and analyzed. Among these patients, 49% were treated with surgery alone, 24% were treated with radiation alone, 10% were treated with surgery and radiation, 15% patients did not receive surgery or radiation, and treatment was unknown in 3% patients. Please see Table 1 and Table 2 for patient characteristics.

Table 2.

Patient demographics/characteristics and multivariate analysis for OS

| Category | Percentage* (N=52,287) | Multivariate Analysis

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard Ratio (95% confidence interval) | P value | ||

| Age (year): Median (range) | 70 (20–103) | 1.032 (1.031–1.034) | |

| Per year increase | |||

| Sex | |||

| Female | 46 | Reference | Reference |

| Male | 54 | 1.199 (1.165–1.234) | <0.001 |

| Race | |||

| White | 85 | Reference | Reference |

| Black | 9 | 1.131 (1.081–1.184) | <.0001 |

| Asian | 5 | 0.872 (0.817–0.930) | <.0001 |

| Other/Unknown | 1 | 1.004 (0.840–1.201) | 0.963 |

| Histology | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 38 | Reference | Reference |

| Bronchioalveolar carcinoma | 8 | 0.569 (0.523–0.618) | <.0001 |

| Large cell carcinoma | 6 | 1.382 (1.306–1.463) | <.0001 |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 31 | 1.224 (1.182–1.268) | <.0001 |

| NOS | 18 | 1.650 (1.587–1.715) | <.0001 |

| Extension of primary tumor | |||

| E1 | 59 | Reference | Reference |

| E2 | 22 | 1.075 (1.037–1.115) | <.0001 |

| E3 | 9 | 1.506 (1.439–1.575) | <.0001 |

| E4 | 10 | 1.504 (1.440–1.572) | <.0001 |

| N stage | |||

| N0 | 61 | Reference | Reference |

| N1 | 10 | 1.353 (1.290–1.419) | <.0001 |

| N2 | 25 | 2.089 (2.022–2.159) | <.0001 |

| N3 | 3 | 2.548 (2.387–2.720) | <.0001 |

| Primary tumor size (cm) | |||

| Median (range) | 3.2 (0.3–38) | 1.352 (1.326–1.378) | <.0001 |

| Per one-fold increase | |||

|

| |||

| Alive | |||

| Yes | 47 | NA | NA |

| No | 53 | NA | NA |

Percentages are rounded and may not add up to 100%.

Survival outcomes

On multivariate analysis, younger age, female gender, adenocarcinoma histology (vs squamous or large cell), Asian race (vs white), N0 (vs N1, N2, or N3), smaller tumors, and lower extension subgroups were associated with improved OS (Table 2).

Tumor size effect on OS

To further determine the prognostic value of primary tumor size in patients with NSCLC, we first investigated the relationship between OS and tumor size within each of the subgroups defined by primary tumor extension (i.e., E1, E2, E3, E4). The multivariable models demonstrated a statistically significant association between larger size and survival in all subgroups, with hazard ratios [HR] (95% confidence interval [CI]) of 1.377 (1.34–1.415), 1.37 (1.314–1.429), 1.331 (1.257–1.41), and 1.201 (1.145–1.261) for E1, E2, E3, and E4, respectively. Figure 1A demonstrates the survival curves according to tumor size quartile within each of the E subgroups.

Figure 1.

The effect of tumor size on OS according to tumor extension groups (A) and N stages (B). Patients in each nodal or extension group were separated into 4 subgroups based on the tumor size ≤ 2 cm; 2–5 cm; 5–7 cm; and > 7cm. OS was analyzed in each subgroup as a function of tumor size.

Next, we investigated the relationship between OS and the tumor size in patients with N0, N1, N2 and N3 status respectively. The multivariable models demonstrated a statistically significant association between larger size and survival in all subgroups, with HR (95% CI) of 1.453 (1.413–1.494), 1.332 (1.251–1.417), 1.219 (1.181–1.258), and 1.191 (1.093–1.297), for N0, N1, N2, and N3, respectively. Figure 1B demonstrates the survival curves according to tumor size quartile within each of the N subgroups. As expected, the association between tumor size and survival is strong and statistically significant in the group with node negative tumors. Interestingly, this statistically significant association is also seen in patients with N1, N2, and N3 disease.

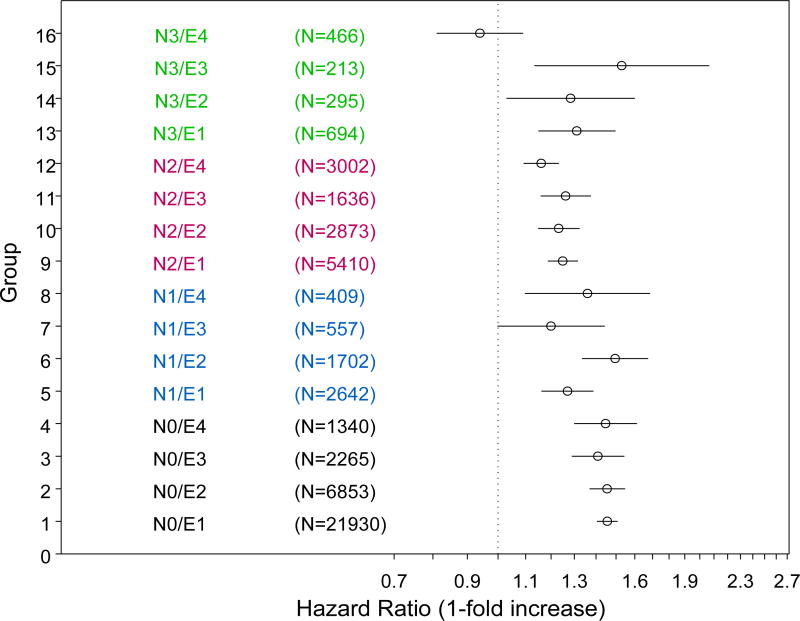

We then analyzed the effect of tumor size on OS using multivariate Cox proportional hazards model on each subgroup defined by tumor extension and nodal involvement (Table 2). As shown in Figure 2, tumor size had a statistically significant effect on OS in 15 of the 16 subgroups after adjustment for age, sex, race, and histology. The only exception is the E4 N3 subgroup.

Figure 2.

Hazard ratio of death per one-fold increase in tumor size in 16 subgroups based on tumor extension and nodal status. The circles represent the point estimates of hazard ratios of death and the bars show the 95% confidence intervals. It indicates increased risks of death if hazard ratio >1 while decreased risks of death if hazard ratio <1. For example, for subgroup 1 (N0E1), one-fold increase in tumor size is associated with 1.456 (1.406–1.508) fold risks of death.

Risk Models

To further refine the analyses on the prognostic value of tumor size, we created two Cox models to predict survival incorporating age, sex, race, histology, N stage, and tumor extension with and without adding tumor size. The predictive ability of the two models was quantified by the C-index, which is the area under the receiver operating characteristics curve adapted for survival data. The model incorporating tumor size has superior predictive accuracy (C-Index = 0.7136) compared to the model that incorporated all other factors but did not include tumor size (C-Index = 0.7042). Although the C-index allows various models to be ranked according to accuracy, it cannot be used for hypothesis testing. Therefore, we performed a test for concordance to test the hypothesis that the model containing size information outperformed the model without size information. The performance improvement of the model incorporating tumor size over the model without tumor size was statistically significant by two methods (p<0.0001, Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of two Cox models with or without incorporating tumor size using the rcorrp.cens function

| Model 1 vs. Model 2 | Model 2 vs. Model 1 | U-Statistic p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Method 1 | 57.7 | 42.3 | <.0001 |

| Method 2 | 4.90 | 3.96 | <.0001 |

Model 1: Parameters include age, sex, race, histology, nodal stage, tumor extension and tumor size.

Model 2: Parameters include age, sex, race, histology, nodal stage, and tumor extension without tumor size.

Method 1: Estimate the fraction of pairs for which the model 1 difference is more impressive than the model 2 difference.

Method 2: Estimate the fraction of pairs for which model 1 is concordant with survival data but model 2 is not.

We then constructed an easy-to-use nomogram based on the model with tumor size to increase its clinical usefulness (Figure 3A). Calibration of our nomogram showed the predicted 2-year OS was almost identical to the actual observed 2-year OS with slim estimation bias (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

A. Nomogram for predicting OS. Instructions: for each parameter (tumor size, age, gender, race, histology, node status, and tumor extension), read the points assigned on a 0 to 100 scale and add these points. Read the results on the ‘Total Points’ scale and then read the corresponding predictions below it. Example: an African American 60 year-old male patient with an N1, 8cm adenocarcinoma involving the chest wall, would score a total of 161 points: 9 (black) + 7 (male) + 44 (age) + 21 (adenocarcinoma) + 15 (extension 60, chest wall invasion) + 11 (N1) + 54 (8 cm size). His predicted 2-year survival rate and median survival time would be about 35% and about 15 months, respectively. Extension codes: 10 (tumor confined to one lung), 20/40 (tumor involving pleura or main stem bronchus ≥ 2 cm from carina), 50/60/73 (tumor involving chest wall or main stem bronchus < 2 cm from carina), 70 (tumor invading mediastinum).

B. Calibration plot for the nomogram. The dashed line indicates the ideal reference line where predicted probabilities would match the observed survival rates. The dots are calculated from subcohorts of our data and represent the performance of the nomogram based on the Cox model. The X marks indicate bootstrap based, bias-corrected predictions, representing the performance of the nomogram on future new data. The closer the solid line is to the dashed line, the more accurately the model predicts OS.

Discussion

Here we present our comprehensive analysis of the effect of tumor size on OS of NSCLC patients using the SEER database. As expected, in node-negative tumors, there was a predictable relationship between tumor size and OS, with increasing size correlating with a decrease in survival. A similar relationship was also observed in locally invasive tumors and in tumors with extensive lymph node involvement. In our Cox model, tumor size added significant additional predictive information for survival beyond all other clinical parameters including age, sex, race, histology, N stage, and tumor extension indicating that tumor size is an independent prognostic factor. We developed a nomogram for survival prediction including the aforementioned variables, which allows our model to be easily applied in clinical practice.

The NCI SEER database is the only comprehensive source of population-based information in the United States that includes stage of cancer at the time of diagnosis and patient survival data. The SEER Program covers approximately 28 percent of the US population,12 thus encompassing a much larger sample size than would otherwise be possible with any single institution and most multi-institutional experiences. In addition, SEER provides information on patients from across the country in many different treatment settings, both community and academic practices, which makes our analysis more representative of the general US patient populations. The robustness of the SEER database to identify clinical predictors of outcomes has been recently underscored by the revisions to the NSCLC AJCC TNM classification project undertaken by the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC).3,13,14 In this effort, an international database was created to identify novel prognostic markers in lung cancers, leading to modification of the T classification and TNM stage grouping.3,14 Importantly, the findings from this prospectively, independently collected database were validated using the SEER data, illustrating the accuracy of clinical information and survival outcomes collected within the context of the SEER program. These observations increase the confidence in our results, indicating the importance of tumor size in determining survival in patients with early stage NSCLC, locally invasive NSCLC, or NSCLC with extensive nodal involvement.

Despite the large sample size, one limitation of the SEER database, and consequently of our analysis, is the lack of information regarding the use of systemic therapy, performance status, smoking status, and patterns of failure (i.e., development of locoregional and/or distant recurrence). Moreover, the optimal definition of adenocarcinoma tumor size has recently been readdressed, as appreciated by observations of possible higher prognostic accuracy conferred by determining the size of the invasive components of the tumor, measured either pathologically (in invasive tumors with lepidic areas), or radiologically (by measuring the solid component of part-solid nodules).15 Unfortunately, these data are not captured in the SEER database. Nonetheless, even without the information on these other prognostic factors and outcome parameters, our data strongly suggest that primary tumor size should be more comprehensively integrated into the next iteration of the TNM classification / AJCC staging system.

While tumor size has been recognized previously as an important factor for prognosis of patients with NSCLC and has been taken into consideration in the TNM Staging System,1,6,7 a comprehensive analysis of its impact within the subgroups of patients with locally invasive disease and extensive nodal disease has not been performed. For example, early efforts evaluating tumor size and survival focused mainly on early stage NSCLC, particularly node-negative NSCLC, and showed clear evidence that tumor size impacts survival in node-negative disease.6,16–28 Other studies included patients with node-positive disease, mainly stage II, but the sample size was limited and the proportion of patients with node-positive diseases was small.29,30 Recent studies have shown that tumor size or volume impacts the survival of patients with locally advanced NSCLC treated with radiation or chemoradiotherapy.13,31–33 However, these analyses were again limited by the small sample size and treatment modalities were restricted to radiation or chemoradiation. Two recent SEER database-based studies with a larger number of patients have attempted to investigate the prognostic significance of tumor size in patients with locally advanced NSCLC and both showed tumor size to be an independent prognostic factor.34,35 However, both studies were focused on stage III disease, while node-positive stage IIA and IIB disease were not included. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first comprehensive population-based study with the largest sample size including node-negative and node-positive NSCLC, evaluating the impact of primary tumor size on survival according to both nodal involvement and extent / invasiveness of primary tumor.

In previous studies, including the two SEER-based studies on stage III NSCLCs,34,35 tumor size was subclassified into categorical variables, thus potentially resulting in underestimation of the extent of variation in survival among groups and concealing nonlinearity in the relation between tumor size and survival. In contrast, to best utilize the information on tumor size, we looked at tumor size as a continuous variable in the multivariate models, potentially improving prediction accuracy.

Our data also corroborate the importance of development of other tools that can evaluate multiple variables not encompassed by the current staging system, such as the nomogram presented herein. We have demonstrated that the multivariate model integrating tumor size (as a continuous variable), age, gender, race, histology, nodal involvement, and primary tumor extension is superior to the AJCC 7th edition in predicting OS. We envision that, in the future, collection of these, and other potential candidate prognostic factors, in a more detailed way, using multi-institutional, international, large data repositories will allow for the development of more accurate methods to predict clinical outcomes, thus assisting clinicians in selecting more appropriate therapies tailored to each individual patient’s risk. Toward this end, the IASLC has expanded their database/staging project to include other variables such as performance status, histologic cell type, gender, age, some routine lab tests, etc.36 Additionally, as biomarker analysis become more common in clinical practice, it is likely that this information will also contribute to determine prognosis. As an example, the presence of EGFR activating mutations in both metastatic37 and earlier stage38–40 NSCLC not treated with EGFR inhibitors is associated with improved survival. Likewise, we have recently demonstrated that complex intra-tumor heterogeneity assessed by multi-region whole exome sequencing may also be associated with a higher risk of postsurgical recurrence, and consequently mortality, in localized NSCLCs, in a preliminary set of samples.41 We speculate that integration of such data to the current prognostic models will increase their accuracy, underscoring the importance of creating nomograms and/or electronic tools that can incorporate multiple variables and novel prognostic factors beyond the scope of the current AJCC staging system.

In summary, we have demonstrated that larger primary tumor size is associated with inferior survival in patients with early stage NSCLC, locally advanced disease, and in patients with extensive nodal involvement. These data corroborate integration of primary tumor size in a more comprehensive way into the next iteration of the TNM/AJCC classification system. Risk models and nomograms incorporating multiple variables such as primary tumor size (as a continuous variable), age, gender, race, histology, nodal involvement, and primary tumor extension are more accurate in predicting OS in non-metastatic NSCLCs. Our findings may provide a framework to refine prognostication methods for clinical practice, as more detailed, large-scale data become available through (multi) national efforts, including information on demographics, clinical characteristics and, potentially, biomarkers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work is supported in part by the National Institutes of Health through M. D. Anderson’s Cancer Center Support Grant CA 016672 - Lung Program, and the Mayberry Foundation.

Footnotes

Where and when the study has been presented in part elsewhere

Part of the study was presented in 2012 ASCO annual meeting in Chicago, IL.

References

- 1.Motta G, Carbone E, Spinelli E, et al. Considerations about tumor size as a factor of prognosis in NSCLC. Ann Ital Chir. 1999;70:893–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldstraw P, Crowley J, Chansky K, et al. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: proposals for the revision of the TNM stage groupings in the forthcoming (seventh) edition of the TNM Classification of malignant tumours. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2:706–14. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31812f3c1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Groome PA, Bolejack V, Crowley JJ, et al. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: validation of the proposals for revision of the T, N, and M descriptors and consequent stage groupings in the forthcoming (seventh) edition of the TNM classification of malignant tumours. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2:694–705. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31812d05d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Postmus PE, Brambilla E, Chansky K, et al. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: proposals for revision of the M descriptors in the forthcoming (seventh) edition of the TNM classification of lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2:686–93. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31811f4703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rami-Porta R, Ball D, Crowley J, et al. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: proposals for the revision of the T descriptors in the forthcoming (seventh) edition of the TNM classification for lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2:593–602. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31807a2f81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rusch VW, Crowley J, Giroux DJ, et al. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: proposals for the revision of the N descriptors in the forthcoming seventh edition of the TNM classification for lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2:603–12. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31807ec803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al., editors. American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Manual. 7. New York: Springer; 2010. Lung; pp. 311–328. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Surveillance E, and End Results Program. http://training.seer.cancer.gov/collaborative/system/tnm/t/size/

- 9.Surveillance E, and End Results Program. http://training.seer.cancer.gov/collaborative/system/tnm/n/rules.html.

- 10.Hanley JA, McNeil BJ. The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology. 1982;143:29–36. doi: 10.1148/radiology.143.1.7063747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harrell FE. Regression modeling strategies : with applications to linear models, logistic regression, and survival analysis. New York: Springer; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program: Overview of the SEER Program. http://seer.cancer.gov/about/overview.html.

- 13.Ball D, Mitchell A, Giroux D, et al. Effect of tumor size on prognosis in patients treated with radical radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy for non-small cell lung cancer. An analysis of the staging project database of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8:315–21. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31827dc74d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Detterbeck FC, Boffa DJ, Tanoue LT. The new lung cancer staging system. Chest. 2009;136:260–71. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Travis WD, Brambilla E, Noguchi M, et al. International association for the study of lung cancer/american thoracic society/european respiratory society international multidisciplinary classification of lung adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:244–85. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318206a221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Black WC. Unexpected observations on tumor size and survival in stage IA non-small cell lung cancer. Chest. 2000;117:1532–4. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.6.1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Campione A, Ligabue T, Luzzi L, et al. Impact of size, histology, and gender on stage IA non-small cell lung cancer. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2004;12:149–53. doi: 10.1177/021849230401200214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carr SR, Schuchert MJ, Pennathur A, et al. Impact of tumor size on outcomes after anatomic lung resection for stage 1A non-small cell lung cancer based on the current staging system. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;143:390–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Christian C, Erica S, Morandi U. The prognostic impact of tumor size in resected stage I non-small cell lung cancer: evidence for a two thresholds tumor diameters classification. Lung Cancer. 2006;54:185–91. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flieder DB, Port JL, Korst RJ, et al. Tumor size is a determinant of stage distribution in t1 non-small cell lung cancer. Chest. 2005;128:2304–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.4.2304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gajra A, Newman N, Gamble GP, et al. Impact of tumor size on survival in stage IA non-small cell lung cancer: a case for subdividing stage IA disease. Lung Cancer. 2003;42:51–7. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(03)00285-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kates M, Swanson S, Wisnivesky JP. Survival following lobectomy and limited resection for the treatment of stage I non-small cell lung cancer<=1 cm in size: a review of SEER data. Chest. 2011;139:491–6. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-2547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee PC, Korst RJ, Port JL, et al. Long-term survival and recurrence in patients with resected non-small cell lung cancer 1 cm or less in size. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;132:1382–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.08.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu S, Xu S, Liu Z, et al. Impact of tumor size on survival in stage I A non-small cell lung cancer. Zhongguo Fei Ai Za Zhi. 2006;9:68–70. doi: 10.3779/j.issn.1009-3419.2006.01.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patz EF, Jr, Rossi S, Harpole DH, Jr, et al. Correlation of tumor size and survival in patients with stage IA non-small cell lung cancer. Chest. 2000;117:1568–71. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.6.1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Port JL, Kent MS, Korst RJ, et al. Tumor size predicts survival within stage IA non-small cell lung cancer. Chest. 2003;124:1828–33. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.5.1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takeda S, Fukai S, Komatsu H, et al. Impact of large tumor size on survival after resection of pathologically node negative (pN0) non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;79:1142–6. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.09.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ye C, Masterman JR, Huberman MS, et al. Subdivision of the T1 size descriptor for stage I non-small cell lung cancer has prognostic value: a single institution experience. Chest. 2009;136:710–5. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-0823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cangir AK, Kutlay H, Akal M, et al. Prognostic value of tumor size in non-small cell lung cancer larger than five centimeters in diameter. Lung Cancer. 2004;46:325–31. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2004.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Agarwal M, Brahmanday G, Chmielewski GW, et al. Age, tumor size, type of surgery, and gender predict survival in early stage (stage I and II) non-small cell lung cancer after surgical resection. Lung Cancer. 2010;68:398–402. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Basaki K, Abe Y, Aoki M, et al. Prognostic factors for survival in stage III non-small-cell lung cancer treated with definitive radiation therapy: impact of tumor volume. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;64:449–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.07.967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.De Petris L, Lax I, Sirzen F, et al. Role of gross tumor volume on outcome and of dose parameters on toxicity of patients undergoing chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Med Oncol. 2005;22:375–81. doi: 10.1385/MO:22:4:375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alexander BM, Othus M, Caglar HB, et al. Tumor volume is a prognostic factor in non-small-cell lung cancer treated with chemoradiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;79:1381–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.12.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maximus S, Nguyen DV, Mu Y, et al. Size of Stage IIIA primary lung cancers and survival: a surveillance, epidemiology and end results database analysis. Am Surg. 2012;78:1232–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morgensztern D, Waqar S, Subramanian J, et al. Prognostic significance of tumor size in patients with stage III non-small-cell lung cancer: a surveillance, epidemiology, and end results (SEER) survey from 1998 to 2003. J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7:1479–84. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318267d032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sculier JP, Chansky K, Crowley JJ, et al. The impact of additional prognostic factors on survival and their relationship with the anatomical extent of disease expressed by the 6th Edition of the TNM Classification of Malignant Tumors and the proposals for the 7th Edition. J Thorac Oncol. 2008;3:457–66. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31816de2b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eberhard DA, Johnson BE, Amler LC, et al. Mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor and in KRAS are predictive and prognostic indicators in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer treated with chemotherapy alone and in combination with erlotinib. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5900–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Izar B, Sequist L, Lee M, et al. The impact of EGFR mutation status on outcomes in patients with resected stage I non-small cell lung cancers. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;96:962–8. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.05.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sonobe M, Nakagawa M, Takenaka K, et al. Influence of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) gene mutations on the expression of EGFR, phosphoryl-Akt, and phosphoryl-MAPK, and on the prognosis of patients with non-small cell lung cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2007;95:63–9. doi: 10.1002/jso.20547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.D’Angelo SP, Janjigian YY, Ahye N, et al. Distinct clinical course of EGFR-mutant resected lung cancers: results of testing of 1118 surgical specimens and effects of adjuvant gefitinib and erlotinib. J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7:1815–22. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31826bb7b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang J, Fujimoto J, Zhang J, et al. Intra-tumor Heterogeneity in Localized Lung Adenocarcinomas Delineated by Multi-region Sequencing. Science. 2014;346:256–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1256930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.