Abstract

Aim

To examine the phylogeography of Ficus insipida subsp. insipida in order to investigate patterns of spatial genetic structure across the Neotropics and within Amazonia.

Location

Neotropics.

Methods

Plastid DNA (trnH–psbA; 410 individuals from 54 populations) and nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS; 85 individuals from 27 populations) sequences were sampled from Mexico to Bolivia, representing the full extent of the taxon's distribution. Divergence of plastid lineages was dated using a Bayesian coalescent approach. Genetic diversity was assessed with indices of haplotype and nucleotide diversities, and genetic structure was examined using spatial analysis of molecular variance (SAMOVA) and haplotype networks. Population expansion within Amazonia was tested using neutrality and mismatch distribution tests.

Results

trnH–psbA sequences yielded 19 haplotypes restricted to either Mesoamerica or Amazonia; six haplotypes were found among ITS sequences. Diversification of the plastid DNA haplotypes began c. 14.6 Ma. Haplotype diversity for trnH–psbA was higher in Amazonia. Seven genetically differentiated SAMOVA groups were described for trnH–psbA, of which two were also supported by the presence of unique ITS sequences. Population expansion was suggested for both markers for the SAMOVA group that contains most Amazonian populations.

Main conclusions

Our results show marked population genetic structure in F. insipida between Mesoamerica and Amazonia, implying that the Andes and seasonally dry areas of northern South America are eco-climatic barriers to its migration. This pattern is shared with other widespread pioneer species affiliated to wet habitats, indicating that the ecological characteristics of species may impact upon large-scale phylogeography. Ficus insipida also shows genetic structure in north-western Amazonia potentially related to pre-Pleistocene historical events. In contrast, evident population expansion elsewhere in Amazonia, in particular the presence of genetically uniform populations across the south-west, indicate recent colonization. Our findings are consistent with palaeoecological data that suggest recent post-glacial expansion of Amazonian forests in the south.

Keywords: Amazonia, Andes, genetic diversity, lineage divergence, Mesoamerica, phylogeographical structure, pioneer species, pollen dispersal, seasonally dry vegetation, seed dispersal

Introduction

Phylogeographical studies can give insights into past changes in species distributions that can be related to environmental change and the history of landscapes (Avise, 2000). Phylogeography therefore has much to offer in understanding past vegetation dynamics in areas where macro- and microfossil records are rare. For this reason, there have been an increasing number of phylogeographical studies of trees in the Neotropics (reviewed by Cavers & Dick, 2013). While these studies have given insights into large-scale geographical relationships of populations, their results have not always been consistent. Given the massive geographical scale of Neotropical forests, especially Amazonia, which contain the most species-rich forests in the world (Gentry, 1988), much work remains to be done.

At a broad-scale, low genetic structure has been inferred from nuclear markers of pioneer species across the Neotropics indicating high gene flow for pollen and/or seeds and/or recent colonization over large areas (Dick et al., 2007; Turchetto-Zolet et al., 2012; Rymer et al., 2013; Scotti-Saintagne et al., 2013a). However, the genetic structure inferred from the plastid genome is not consistent across study species. Given that the plastid genome is inherited maternally in most angiosperms, this pattern implies that the seed dispersal history of these species varies.

Ecological characteristics of species may contribute to this variation in phylogeographical patterns. For example, studies of Ceiba pentandra (Dick et al., 2007), Cordia alliodora (Rymer et al., 2013) and Jacaranda copaia (Scotti-Saintagne et al., 2013a) indicate that these long-lived pioneer trees with wind-dispersed seeds and tolerance to drought can overcome two potential barriers between Amazonia and Mesoamerica: the Andean Cordillera and seasonally dry areas of northern South America. These studies show weak phylogeographical structure for plastid markers across the Neotropics, suggesting recent seed dispersal across these barriers. In contrast, other pioneer species with wind-dispersed seeds, notably Schizolobium parahyba (Turchetto-Zolet et al., 2012) and Ochroma pyramidale (Dick et al., 2013), both intolerant to drought, show genetic evidence for restricted seed dispersal between populations located at either side of these barriers. These contrasting patterns may imply that whether or not Neotropical rain forest tree species are drought-tolerant may have a strong impact on their phylogeography.

Within Amazonia, prior phylogeographical studies of trees have used intense sampling in a restricted geographical location (e.g. a 250-km transect; Dexter et al., 2012), in a region representing just part of a species' range (1500- to 2500-km transect; Lemes et al., 2010; Turchetto-Zolet et al., 2012), or sparse population sampling across a wide geographical range (Dick et al., 2007; Dick & Heuertz, 2008). Only a few studies have moderate, range-wide sample densities in Amazonia (e.g. Rymer et al., 2013; Scotti-Saintagne et al., 2013a,b). Collectively, this work has demonstrated contrasting phylogeographical patterns across the Amazon Basin inferred from the plastid genome. For example, plastid genetic differentiation measured in multiple species of Inga (Fabaceae) in south-eastern Peru suggests a zone of secondary contact between two historically isolated populations (Dexter et al., 2012). High genetic differentiation was also reported among populations of Swietenia macrophylla in the Brazilian Amazon using chloroplast microsatellite data (Lemes et al., 2010). In contrast, Ceiba pentandra (Dick et al., 2007) and Symphonia globulifera (Dick & Heuertz, 2008) have low genetic structure for plastid DNA markers across Amazonia.

Strong genetic structure in areas of Amazonia that are currently covered in continuous rain forest and without evident barriers to migration may reflect the effects of historical events in generating isolation among populations (Dexter et al., 2012). These historical events could include large fluvial rearrangements during the late Miocene (Hoorn et al., 1995), high frequency of fluvial dynamics of lateral erosion and deposition during the Pliocene–Pleistocene (Salo et al., 1986), or Quaternary climatic fluctuations (Haffer, 1969). Low genetic structure across the vast Amazon Basin in other species is consistent with recent population expansion (Dick & Heuertz, 2008). Nevertheless, comprehensive evaluation of population genetic structure across the range of widely distributed Amazon species is a demanding task.

Here, we examine the phylogeography of Ficus insipida Willd. subsp. insipida (Moraceae) at a broad-scale across the Neotropics and at a regional-scale within Amazonia. This subspecies is a key element of early successional Neotropical rain forest communities. It is a good exemplar taxon for widespread Neotropical rain forest trees because it is distributed across the Andes and into Mesoamerica, is a long-lived pioneer tree confined to humid environments, and, like the majority of rain forest trees, has animal-dispersed seeds. We used an intensive range-wide geographical sampling scheme and worked with both plastid and nuclear DNA markers. Our specific objectives were: (1) to estimate divergence time among lineages; (2) to compare genetic diversity within and among populations and between Mesoamerica and Amazonia; (3) to test population genetic structure and the spatial location of genetic breaks; (4) to establish where populations of F. insipida subsp. insipida show genetic uniformity or distinctiveness in Amazonia; and (5) to establish if the regional patterns we find might reflect Quaternary climate changes or the legacies of more ancient geological events.

Materials and methods

The study species and population sampling

The pantropical genus Ficus L. comprises c. 750 species (Berg, 2001). Ficus insipida is the most morphologically distinct and widespread Neotropical species of the section Pharmacosycea, a group of c. 20 tree species (Berg, 2001). In this study, we focus on F. insipida subsp. insipida, which is distributed from Mexico through the Andean region to the lowland rain forest of western Amazonia. This taxon is easily identified by its oblong to elliptic, bright and shiny leaves with yellow secondary veins and 5–12.5 cm long terminal stipules (Berg et al., 1984). Ficus insipida subsp. scabra C.C. Berg from eastern Brazil, the Guianas and north-eastern Venezuela, and Ficus adhatodifolia Schott from southern Bolivia, southern Brazil (including the Atlantic rain forest) and Paraguay have similar leaf morphology to F. insipida subsp. insipida but have smaller stipules (1–4 cm long), different coloration in the mature fruits, and non-overlapping geographical ranges (Berg et al., 1984). We did not find these taxa in our sampling areas, and consider that problems of misidentification in our sampling are minimal.

Our study is based principally on leaf samples collected from the field for 410 individual trees of F. insipida subsp. insipida. A total of 54 populations from Mexico, Belize, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Panama, Ecuador, Peru and Bolivia were visited, covering the breadth of the taxon's distribution across Mesoamerica (n = 31 sites) and Amazonia (n = 23 sites). At least eight individuals were collected at each site, although fewer samples were sourced from several sites where the species was rare. In some cases our sampling was supplemented using herbarium specimens. Leaf samples were dried and stored in silica gel and the locations of individuals were recorded using a handheld GPS. For Amazonian populations, at least one herbarium voucher was collected from each population (see Appendix S1 in Supporting Information).

DNA extraction, sequencing and editing

Total genomic DNA was extracted using the CTAB method (Doyle & Doyle, 1987). Seven plastid markers were tested for amplification and sequence variation: rpl32–trnL, trnQ–5′-rps16, 3′trnV–ndHC, atpI–atpH, trnD–trnT, trnH–psbA and trnL–trnF (Shaw et al., 2007). The non-coding marker trnH–psbA was chosen for the full-scale study because of its high amplification success and variability within and among populations of F. insipida subsp. insipida. In addition, the internal transcribed spacer region (ITS) of the nuclear ribosomal DNA was amplified and sequenced for 77 samples from Amazonia using the ITS1 and ITS4 primers (White et al., 1990). Eight additional ITS sequences from other regions (one from Mexico, one from Costa Rica, five from Panama and one from Brazil) were contributed by collaborators (see Acknowledgements). Reaction conditions varied slightly between Mesoamerican and Amazonian samples, because amplifications were performed in different laboratories. Mesoamerican PCR reactions were performed in 10 μL volume, and contained 1 μL of template DNA, 1× Sigma PCR buffer, 3.0 mm MgCl2, 200 μm of each dNTP, 0.4 μL 10 mg/mL bovine serum albumin (BSA), 0.2 μm of each primer and 1 U JumpStartTM Taq polymerase (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) (see Poelchau & Hamrick, 2013). PCR for the Amazonian samples was performed in 20 μL solutions containing 2 μL of template DNA, 2 μL of PCR Buffer 10×, 2 μL of 10 mm total dNTP, 1 μL of 50 mm MgCl2, 1 μL of each primer, 4 μL of combinatorial enhancer solution (CES), 0.2 μL of Taq polymerase (Bioline, UK) and 6.8 μL of distilled H2O. However, identical cycling programs were used for samples of both geographical regions. The thermal cycle for trnH–psbA (and ITS) was 94 °C for 5 min (3 min), followed by 35 (30) cycles at 94 °C for 30 s (1 min), 55 °C (56 °C) for 30 s (1 min) and 72 °C for 1 min (90 s), and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min (5 min). Mesoamerican PCR products were sequenced as in Poelchau & Hamrick (2013); Amazonian PCR products were visualized via 1% agarose gel electrophoresis, and products were purified using ExoSAP-IT (Affymetrix UK Ltdn, High Wycombe, UK). Cycle sequencing was conducted in 10 μL solutions containing 3 μL PCR product, 0.5 μL of BigDye (Applied Biosystems, Paisley, UK), 2 μL sequencing reaction buffer 5×, 0.32 μL of primer and 4.18 μL of distilled H2O.

All forward and reverse strands were edited in Sequencher 5.0 (Gene Codes Corporation, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) and nucleotide substitutions, indels (i.e. insertions or deletions) and inversions were visually checked against the original electropherograms. The alignment was created manually in Mesquite 2.74 (Maddison & Maddison, 2001). Mononucleotide repeat polymorphisms were excluded from all subsequent analyses.

Statistical analyses

Divergence of plastid lineages

Bayesian inference was used to estimate divergence time among plastid DNA haplotypes. The ingroup comprised all plastid haplotypes of F. insipida subsp. insipida. Sequences downloaded from GenBank representing nine Ficus species of sections Pharmacosycea (GQ982221, GQ982222, GQ982225GQ982227), Americana (GQ982218, GQ982219 and GQ982224), Sycomorus (EU213825) and Galoglychia (EU213821) and Poulsenia armata (tribe Castilleae) were used as multiple outgroups. Inversions and indels were excluded from the analysis.

Phylogenetic reconstruction of the plastid sequences was performed in beast 1.6.2 (Drummond & Rambaut, 2007) using the uncorrelated lognormal relaxed molecular clock and the HKY nucleotide substitution model that was the closest model suggested by jModelTest 0.0.1 (Posada, 2008). The tree prior model was set using a coalescent approach assuming constant population size. A normal distribution was used for the prior on tree root age with a mean value of 73.9 Ma and a standard deviation including the age estimates for the divergence between Ficus and Poulsenia (49.6–88.2 Ma; Zerega et al., 2005). Three replicate runs were performed using a chain of 100,000,000 states sampling every 10,000 generations. All trees were combined after the exclusion of the first 1000 trees of each run as burn-in to avoid including trees sampled before convergence of the Markov chains. The posterior probabilities and ages of nodes were thus derived from a posterior distribution of 27,000 total trees.

Genetic diversity and population structure

The phylogenetic analysis suggested that three outgroup taxa, Ficus maxima, Ficus tonduzii and Ficus yoponensis, are nested within F. insipida subsp. insipida (Fig.1). These species are highly distinctive morphologically from F. insipida subsp. insipida, which we consider to be a reproductively isolated biological species, and we therefore conducted all population genetic analyses on populations of this taxon alone. The pattern of phylogenetic nesting may simply be due to the origin of one or more of these species from populations of F. insipida subsp. insipida, although the possibility that F. maxima, F. tonduzii and F. yoponensis are more distantly related and sharing haplotypes by occasional hybridization requires consideration (see Results and Discussion).

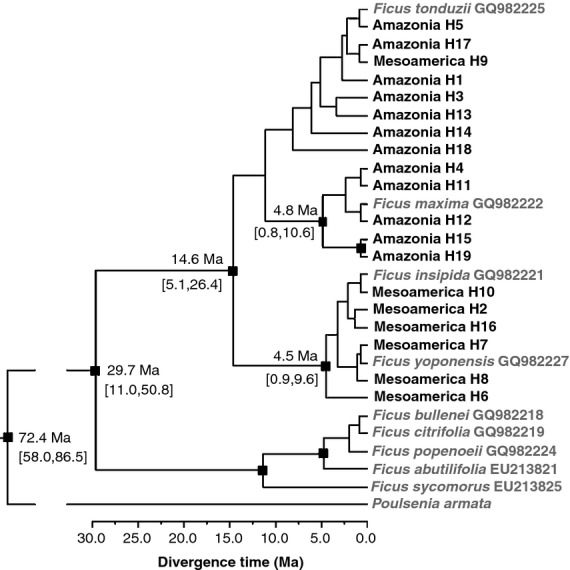

Figure 1.

Lineage divergence dating for all plastid DNA haplotypes (H1–H19) of Ficus insipida subsp. insipida occurring in Mesoamerica and Amazonia. Mean divergence dates are given with 95% highest posterior density values in brackets. Nodes with posterior probabilities above 0.95 are indicated with a black square. Sequences downloaded from GenBank are indicated in grey.

The genealogical relationships of haplotypes were estimated independently for trnH–psbA and ITS sequences using statistical parsimony in tcs 1.21 (Clement et al., 2000), with a 95% parsimony connection limit. Individual indels and inversions were treated as single mutation events.

Because of highly uneven sampling of ITS sequences between Mesoamerica and Amazonia, all subsequent analyses were performed only for trnH–psbA sequences, while the ITS data were used for comparison of general patterns. Haplotype and nucleotide diversities were calculated for each population in Arlequin 3.5 (Excoffier & Lischer, 2010). We compared genetic diversity between Mesoamerica and Amazonia using a rarefaction procedure set to 100 runs that standardized each region to the same number of sequences (n = 182 individuals) using the packages ape (Paradis et al., 2004) and pegas (Paradis, 2010) in R Statistical Software, version 2.15.2. A pattern of isolation by distance for the plastid marker (Wright, 1943), which can indicate restricted seed dispersal, was assessed using a Mantel test in R Statistical Software. Specifically, we compared Nei's pairwise genetic distance among populations and the logarithm of the Euclidean geographical distances. The significance of the relationship was tested with 10,000 permutations.

Genetic differentiation among populations was estimated by computing a distance matrix based on the number of mutational steps between haplotypes (NST) and by using haplotype frequencies (GST). The presence of a phylogenetic component to the phylogeographical structure was assessed by testing whether NST is significantly higher than GST based on 10,000 permutations in PermutCpSSR 2.0 (Pons & Petit, 1996). A spatial analysis of molecular variance (SAMOVA) was performed to determine the position of genetic breaks among populations using samova 1.0 (Dupanloup et al., 2002). Several runs were performed using increasing numbers of groups (K = 1–20) and 100 annealing simulations for each K. In each run, populations were clustered into genetically and geographically homogenous groups (Dupanloup et al., 2002). The number of groups was chosen so as to maximize genetic differentiation among the groups (ΦCT). Genetic structure among groups of populations defined by geographical region and by SAMOVA was further examined by analysis of molecular variance computing a distance matrix in Arlequin 3.5. Significance of genetic structure indices was tested using a nonparametric randomization procedure.

Demographic history

Within Amazonia, the population expansion hypothesis was tested for plastid and nuclear DNA sequences in Arlequin 3.5. We used Fu's FS neutrality test, based on the number of pairwise differences, because this statistic shows large negative values under population expansion (Fu, 1997). In addition, we used a mismatch distribution test to assess whether the observed distribution of pairwise differences matches the expectations under a model of population expansion (Schneider & Excoffier, 1999). We also estimated the parameter tau of demographic expansion (τ) using a generalized nonlinear least squares approach. If a demographic expansion model is not rejected (P > 0.05), time since the expansion (t) can be calculated as τ =2μt, where μ is the mutation rate for the total length of each DNA marker. A mean mutation rate of 1.64 × 10−9 substitutions site−1 year−1 (s s−1 yr−1) for ITS was taken from Dick et al. (2013), while a mean value for the plastid marker was taken from the divergence time analysis. These tests were performed for each SAMOVA group in Amazonia.

Results

Non-monophyly of F. insipida subsp. insipida

The phylogenetic analysis showed that F. insipida subsp. insipida is not monophyletic; other Ficus species of section Pharmacosycea, F. maxima, F. tonduzii and F. yoponensis, are nested within it (Fig.1). These three taxa are readily morphologically distinguished from F. insipida subsp. insipida, and have similarly wide ranges spanning both Central and South America (see http://www.tropicos.org/). The single accessions representing each of these three species come from Barro Colorado Island, Panama (Mesoamerica), but F. tonduzii and F. maxima have sequences related to Amazonian haplotypes of F. insipida and therefore do not cluster geographically with Mesoamerican F. insipida haplotypes. Finally, a GenBank accession of F. insipida subsp. insipida (GQ982221) also collected in Barro Colorado Island is nested within Mesoamerican F. insipida haplotypes (Fig.1).

Divergence time

Diversification of plastid DNA haplotypes in F. insipida subsp. insipida appears to have begun in the Miocene with a split into Mesoamerican and Amazonian lineages estimated at 14.6 Ma (95% highest posterior density, HPD: 5.1–26.4 Ma; Fig.1; see phylogram in Appendix S2a). Pliocene ages were estimated for the main diversification of Mesoamerican haplotypes (4.5 Ma; 95% HPD: 0.9–9.6 Ma; Fig.1) and for the haplotypes H4, H11, H12, H15 and H19 of northern Amazonia (4.8 Ma; 95% HPD: 0.8–10.6 Ma). A second Mesoamerican lineage corresponding to haplotype H9 was nested within the most diverse clade of Amazonian lineages (Fig.1). The mean substitution rate obtained using the relaxed molecular clock was 4.40 × 10−10 s s−1 yr−1 (95% HPD: 2.41 × 10−10 to 6.62 × 10−10 s s−1 yr−1).

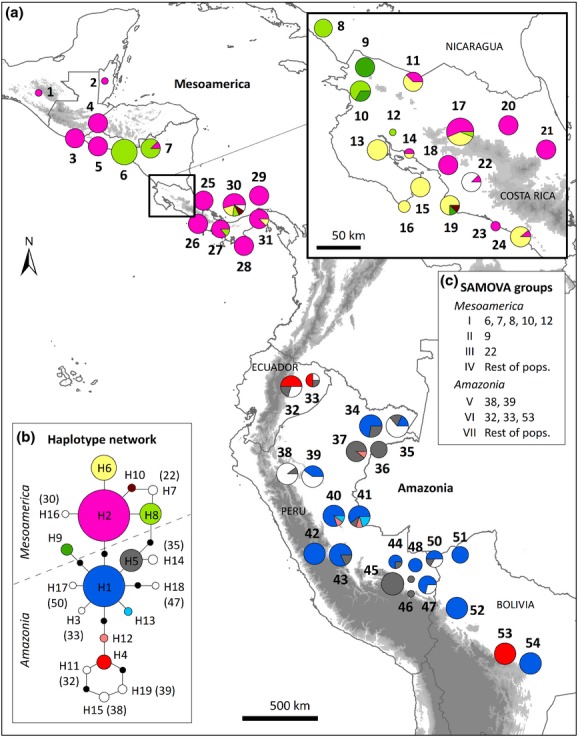

Plastid DNA

For the plastid trnH–psbA marker, a total of 410 individuals collected in 54 populations were successfully sequenced (Table1): 228 samples from Mesoamerica (n = 31 sites) and 182 from Amazonia (n = 23 sites). After the exclusion of two variable mononucleotide repeats, 340 bp of aligned sequences remained. A total of 19 polymorphic sites were detected including 14 substitutions, four indels and one inversion (see Appendix S3); these mutations defined a total of 19 haplotypes (Fig.2a). The haplotypes were geographically restricted; seven were confined to Mesoamerica and twelve to Amazonia (Fig.2b). The analysis at the population level indicates values of haplotype diversity above 0.70 in populations 30, 33 and 50, and of nucleotide diversity above 0.70% in populations 10, 33 and 39 (Table1). In addition, rarefied haplotype diversity was higher in Amazonia (95% confidence interval, CI: 0.694–0.703) than Mesoamerica (95% CI: 0.646–0.654), while rarefied nucleotide diversity was higher, but not significantly so in Amazonia (95% CI: Amazonia 0.328%–0.404%; Mesoamerica 0.281%–0.348%).

Table 1.

Haplotype diversity and nucleotide diversity (mean ± SD for both indices) for the plastid trnH–psbA marker in 54 Ficus insipida subsp. insipida populations in Mesoamerica and Amazonia. The metrics were not applicable for populations with less than three individuals sampled. The number of sequences is provided for each population. Regional genetic diversity was estimated using rarefaction procedure.

| No. | Code | Country | Ind. | Hapl. div. | Nucl. div. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | MEX | Mexico | 1 | n.a. | n.a. |

| 2 | BEL | Belize | 1 | n.a. | n.a. |

| 3 | ElI | El Salvador | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | Dei | El Salvador | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | Nan | El Salvador | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | VoC | Nicaragua | 14 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | Mir | Nicaragua | 8 | 0.25 ± 0.18 | 0.07 ± 0.11 |

| 8 | ElO | Nicaragua | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | HLI | Costa Rica | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| 10 | RiT | Costa Rica | 9 | 0.50 ± 0.13 | 0.74 ± 0.50 |

| 11 | CaN | Costa Rica | 8 | 0.54 ± 0.12 | 0.16 ± 0.17 |

| 12 | RiB | Costa Rica | 1 | n.a. | n.a. |

| 13 | RiN | Costa Rica | 9 | 0 | 0 |

| 14 | LaE | Costa Rica | 2 | n.a. | n.a. |

| 15 | Cur | Costa Rica | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| 16 | CaB | Costa Rica | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 17 | RSC | Costa Rica | 16 | 0.58 ± 0.08 | 0.19 ± 0.17 |

| 18 | Esp | Costa Rica | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| 19 | Jac | Costa Rica | 8 | 0.46 ± 0.20 | 0.50 ± 0.37 |

| 20 | LaS | Costa Rica | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| 21 | EaU | Costa Rica | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| 22 | Car | Costa Rica | 8 | 0.25 ± 0.18 | 0.15 ± 0.16 |

| 23 | MaA | Costa Rica | 2 | n.a. | n.a. |

| 24 | HaB | Costa Rica | 9 | 0.22 ± 0.17 | 0.07 ± 0.10 |

| 25 | Cah | Costa Rica | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| 26 | PiB | Costa Rica | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| 27 | CeB | Panama | 7 | 0.29 ± 0.20 | 0.09 ± 0.12 |

| 28 | LaT | Panama | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| 29 | FtS | Panama | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| 30 | PLR | Panama | 11 | 0.71 ± 0.14 | 0.26 ± 0.22 |

| 31 | PNM | Panama | 8 | 0.25 ± 0.18 | 0.07 ± 0.11 |

| 32 | JaS | Ecuador | 10 | 0.69 ± 0.10 | 0.48 ± 0.35 |

| 33 | Bog | Ecuador | 4 | 0.83 ± 0.22 | 0.89 ± 0.69 |

| 34 | Yan | Peru | 11 | 0.44 ± 0.13 | 0.13 ± 0.14 |

| 35 | Mad | Peru | 11 | 0.58 ± 0.14 | 0.25 ± 0.22 |

| 36 | SaJ | Peru | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| 37 | JeH | Peru | 9 | 0.22 ± 0.17 | 0.20 ± 0.19 |

| 38 | Mar | Peru | 10 | 0.20 ± 0.15 | 0.30 ± 0.25 |

| 39 | Ura | Peru | 10 | 0.53 ± 0.09 | 0.79 ± 0.52 |

| 40 | vHu | Peru | 10 | 0.38 ± 0.18 | 0.18 ± 0.17 |

| 41 | Mac | Peru | 10 | 0.64 ± 0.15 | 0.28 ± 0.24 |

| 42 | LaG | Peru | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| 43 | SaT | Peru | 11 | 0.33 ± 0.15 | 0.10 ± 0.12 |

| 44 | CoC | Peru | 4 | 0.50 ± 0.27 | 0.15 ± 0.18 |

| 45 | Qon | Peru | 11 | 0 | 0 |

| 46 | SaG | Peru | 1 | n.a. | n.a. |

| 47 | Tam | Peru | 7 | 0.48 ± 0.17 | 0.28 ± 0.25 |

| 48 | LoA | Peru | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| 49 | LaP | Peru | 1 | n.a. | n.a. |

| 50 | Tah | Bolivia | 6 | 0.73 ± 0.16 | 0.26 ± 0.24 |

| 51 | Aba | Bolivia | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| 52 | Mai | Bolivia | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| 53 | Sac | Bolivia | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| 54 | LaEn | Bolivia | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| MESOAMERICA | 228 | 0.65 ± 0.03 | 0.31 ± 0.23 | ||

| AMAZONIA | 182 | 0.70 ± 0.03 | 0.37 ± 0.26 | ||

n.a., not applicable.

Figure 2.

(a) Haplotype distribution, (b) haplotype network, and (c) SAMOVA groups of trnH–psbA sequences for Ficus insipida subsp. insipida populations sampled from 54 sites in Mesoamerica and Amazonia. Haplotype distributions at the border between Costa Rica and Nicaragua are shown separately. Pie charts are labelled with population numbers as shown in Table1. Colours represent the haplotypes (H1–H19). In the haplotype network (b), haplotypes unique to a single population are shown in white with population number given in brackets. Circle size is proportional to sample size for each population (n = 1–16 individuals) and for each haplotype (n = 1–119 individuals). Missing haplotypes in the network are shown as black dots, and a dashed line separates haplotypes of each region. The Andean Cordillera and other mountains are shown in shaded grey.

Population structure

The Mantel test between genetic and geographical distance showed significant isolation by distance for the plastid marker (r = 0.47, P < 0.001), with higher mean genetic distance between populations in different regions (0.18) than within each region (Amazonia = 0.06 and Mesoamerica = 0.05). Genetic differentiation among populations was significantly higher when computed using a distance matrix (NST = 0.81) than when using haplotype frequencies (GST = 0.72, P < 0.05), indicating some significant phylogeographical structuring. The SAMOVA analysis showed increasing values of differentiation among groups up to a K value of 7 (ΦCT = 0.8). Four groups were defined in Mesoamerica, primarily segregating populations containing haplotypes H8 (group I), H9 (group II) and H7 (group III) from the rest of the Mesoamerican populations (group IV; Fig.2c). Three groups were found in Amazonia: group V containing two populations from north-eastern Peru and mainly haplotypes H15 and H19; group VI containing two populations from Ecuador and one from central Bolivia with mainly haplotype H4; and group VII containing the remaining Amazonian populations (Fig.2c). SAMOVA groups IV and VII contain most of the populations and are dominated by a few widespread haplotypes: H2 in Mesoamerica and H1 and H5 in Amazonia. Mesoamerican haplotype H9 is more related to Amazonian haplotypes, while haplotype H4 shows a disjunct distribution, occurring in Ecuador and in one population in Bolivia (Fig.2a). Grouping of populations by SAMOVA groups explained more of the genetic variation (75.1%) than grouping by the two overall geographical regions (56.2%; Table2).

Table 2.

Analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) based on pairwise differences of the plastid trnH–psbA marker for Ficus insipida subsp. insipida. The analysis was run independently using populations grouped by geographical regions (Mesoamerica and Amazonia) and by SAMOVA groups.

| Group level | Source of variation | d.f. | Sum of squares | Variance components | Percentage of variation | Fixation indices (P < 0.001) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geographical regions | Among groups | 1 | 203 | 0.98 | 56.21 | ΦCT = 0.56 |

| Among pops within groups | 52 | 218 | 0.53 | 30.18 | ΦSC = 0.69 | |

| Within populations | 356 | 84 | 0.24 | 13.61 | ΦST = 0.86 | |

| SAMOVA groups | Among groups | 6 | 353 | 1.21 | 75.14 | ΦCT = 0.75 |

| Among pops within groups | 47 | 68 | 0.16 | 10.13 | ΦSC = 0.41 | |

| Within populations | 356 | 84 | 0.24 | 14.73 | ΦST = 0.85 |

ΦCT, genetic differentiation among groups.

ΦSC, genetic differentiation among populations within groups.

ΦST, genetic differentiation among populations.

Demographic analysis

Demographic analyses for the plastid and ribosomal nuclear DNA markers tentatively suggest range expansion in Amazonia mainly for SAMOVA group VII, which includes 18 of the 23 Amazonian populations. This group had negative values of Fu's FS and low but non-significant P-values for both markers (Table3). In addition, the mismatch distribution for group VII was unimodal, with no significant deviation from the sudden demographic expansion model. Time since expansion was estimated as 2.69 Ma (95% CI: 1.85–4.12 Ma) for the trnH–psbA and as 1.44 Ma (95% CI: 0.23–1.68 Ma) for ITS (Table3).

Table 3.

Demographic expansion tests performed for SAMOVA groups of Ficus insipida subsp. insipida in Amazonia. Time since the expansion was estimated using the mutation rate for the total length of each DNA marker (μtrnH–psbA = 4.40 × 10−10 s s−1 yr−1 × 340 bp, and μITS = 1.64 × 10−9 s s−1 yr−1 × 635 bp). Note that P-values for Fu's FS are only considered significant at the 95% level if the P-value is lower than 0.02 (Excoffier & Lischer, 2010).

| DNA marker | SAMOVA groups | Sample size | Neutrality test |

Mismatch distribution |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fu's FS | P-value | τ | P-value | Time [95% CI] | |||

| trnH–psbA | V | 20 | 2.51 | 0.89 | 6.99 | 0.16 | |

| VI | 24 | 0.92 | 0.71 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||

| VII | 138 | −1.90 | 0.21 | 0.81 | 0.29 | 2.69 Ma [1.85–4.12] | |

| ITS | V | 9 | 0.00 | n.a. | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| VI | 10 | 0.59 | 0.04 | 3.00 | 0.06 | ||

| VII | 58 | −2.21 | 0.03 | 3.00 | 0.14 | 1.44 Ma [0.23–1.68] | |

τ, parameter tau of demographic expansion; n.a., not applicable.

Nuclear ribosomal DNA

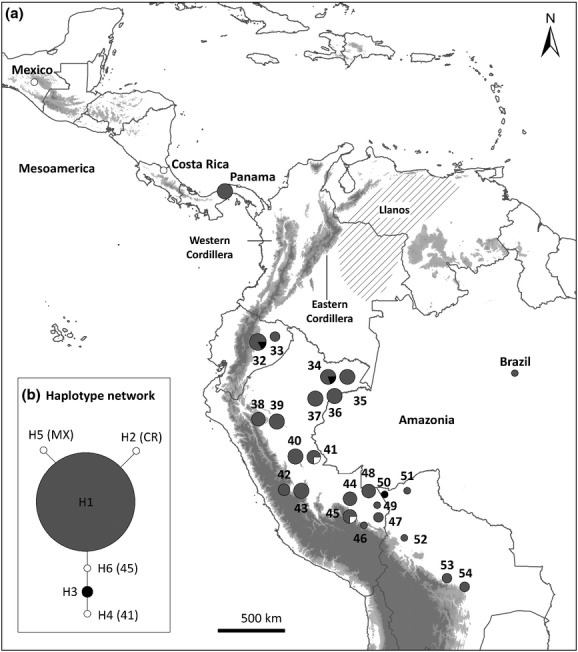

A total of 85 samples were sequenced for ITS, covering the entire study range, but focusing predominantly on Amazonia. Five polymorphic sites, three substitutions and two indels (Appendix S3) were found in the 635 bp of aligned sequences. These mutations defined six haplotypes of which haplotype H1 is widespread across Amazonia and extends to Panama in Central America. Haplotype H3 occurs in three localities in Amazonia and the remaining four haplotypes each occur in single populations in Amazonia and Mesoamerica (Fig.3).

Figure 3.

(a) Haplotype distribution and (b) haplotype network of ITS sequences for Ficus insipida subsp. insipida populations sampled from 27 sites in Mesoamerica and Amazonia. Pie charts are labelled with population numbers as shown in Table1. Colours represent the haplotypes (H1–H6). In the haplotype network (b), haplotypes unique to a single population are shown in white with population number given in brackets. Circle size is proportional to sample size for each population (n = 1–6 individuals) and for each haplotype (n = 1–76 individuals). The Andean Cordillera and other mountains are shown in shaded grey, and the dashed area represents the Llanos. Additional ITS sequences obtained from collaborators are indicated as Mexico (MX), Costa Rica (CR), Panama and Brazil (see Acknowledgements).

Discussion

Non-monophyly of Ficus insipida subsp. insipida

Our phylogenetic analysis showed that three of the outgroup taxa, F. maxima, F. tonduzii and F. yoponensis, were nested within F. insipida subsp. insipida (Fig.1). The lack of monophyly is not unexpected given that F. insipida subsp. insipida and the related species are widespread, and may share ancestor–descendant relationships (cf. Gonzalez et al., 2009; Dexter et al., 2010). If species originate from within widespread species, it would take a long period of time for both to become reciprocally monophyletic in a gene tree (Avise, 2000) in the face of very large effective population size such as that of F. insipida subsp. insipida, which has a huge geographical range and is relatively common. We cannot definitively exclude the possibility that F. maxima, F. tonduzii and F. yoponensis are more distantly related to F. insipida subsp. insipida and that the pattern of shared haplotypes (Appendix S2b) is the result of hybridization with F. insipida subsp. insipida. However, we can at least conclude that hybridization is not frequent given that the species are morphologically distinct from other Ficus species, and intermediates have not been observed in the field (although this does not in itself exclude chloroplast capture). However, the accessions of F. tonduzii and F. maxima from Barro Colorado Island, Panama, share haplotypes with Amazonian accessions of F. insipida subsp. insipida (see Appendix S2b), and if the phylogeographical patterns we observe are due to hybridization we would expect to see geographical sharing of haplotypes. More fundamentally, the key patterns of the population genetic analyses of F. insipida subsp. insipida we observe and discuss below are robust regardless of concerns about species monophyly or the origin of haplotypes. These are a clear divide in chloroplast lineages between geographical areas, which can only be explained via lack of seed flow, and the presence of widespread haplotypes, which suggests recent population expansion.

Genetic structure between Mesoamerica and Amazonia

We found clear population genetic structure in the plastid DNA data of F. insipida subsp. insipida, with differentiation between Mesoamerican and Amazonian haplotypes demonstrated by the haplotype network (Fig.2b) and AMOVA analysis (Table2). Moreover, there is a significant increase of genetic distance with geographical distance among populations, in particular for populations compared between geographical regions. Our phylogenetic analysis of the plastid DNA data is consistent with a split between Amazonian and Mesoamerican lineages of F. insipida subsp. insipida at 14.6 Ma (5.1–26.4 Ma) with subsequent dispersal from Amazonia to Mesoamerica only in the case of haplotype H9 (Fig.1). The early split of F. insipida subsp. insipida lineages implies that there has been limited genetic exchange via seeds and consequently very rare successful dispersal events between the regions. We discuss below at least two potential present-day barriers which can be invoked to explain limitation of seed dispersal between Mesoamerica and Amazonia.

The first and most obvious barrier is the Andes cordillera, which stretches along the entire western edge of South America with elevations (> 4000 m) greatly exceeding the current elevational limits of lowland rain forest trees. Ficus insipida subsp. insipida grows mainly in lowland rain forest and in pre-montane environments reaching elevations of 1500 m a.s.l. and with rare records at 1800–2000 m a.s.l. (see http://www.tropicos.org/). Therefore, the Andes are a significant potential dispersal barrier and must have been since 3 Ma when the most recent uplift of the Eastern Cordillera caused it to reach 2500 m a.s.l. (Gregory-Wodzicki, 2000). A second barrier for wet-adapted species is seasonally dry vegetation: extensive savannas in Colombia and Venezuela (the Llanos) and seasonally dry tropical forests along the Caribbean coast of northern South America (Pennington et al., 2006). Ficus insipida subsp. insipida cannot tolerate seasonal drought (Berg, 2001). Thus, the extensive seasonally dry areas in northern South America may prevent dispersal between Mesoamerica and Amazonia for rain forest trees such as F. insipida subsp. insipida.

Studies from other Neotropical tree species support the generalized interpretation that taxa which are unable to tolerate seasonally dry habitats have also been unable to use the northern seasonally dry tropical forest and savannas as a migration route. Limited seed flow via this route would explain their strong population differentiation between Mesoamerica and Amazonia. For example, Schizolobium parahyba (Turchetto-Zolet et al., 2012) and Ochroma pyramidale (Dick et al., 2013) are pioneer species restricted to wet environments, and show restricted seed dispersal between Mesoamerica and Amazonia (Table4). Moreover, shade-tolerant rain forest-confined species such as Symphonia globulifera (Dick & Heuertz, 2008), Poulsenia armata and Garcinia madruno (Dick et al., 2013) have distinct plastid DNA haplotypes in these regions. In contrast, weak population genetic structure with identical or closely related plastid DNA haplotypes spanning Mesoamerica and Amazonia have been reported for other pioneer trees such as Ceiba pentandra (Dick et al., 2007), Cordia alliodora (Rymer et al., 2013), Jacaranda copaia (Scotti-Saintagne et al., 2013a) and Trema micrantha (Dick et al., 2013). Although seed dispersal syndrome differs among these species, they have a broad ecological range and are tolerant to drought (Table4). In particular, Ceiba pentandra, Cordia alliodora and Trema micrantha are recorded in inventories of seasonally dry tropical forests on the Caribbean coast of Colombia (see herbarium collections at http://www.biovirtual.unal.edu.co/ICN/; Linares-Palomino et al., 2011). This apparent association between drought tolerance and levels of phylogeographical structure remains tentative until further detailed studies are available for comparison.

Table 4.

Summary of phylogeographical studies of Neotropical pioneer tree species. Genetic markers used in each study including nuclear ribosomal DNA (nrDNA), chloroplast DNA (cpDNA), and nuclear and chloroplast simple sequence repeats (nuSSR and cpSSR, respectively) are indicated. Low genetic structure indicates similar nuclear or plastid DNA haplotypes between Mesoamerica and Amazonia while high structure indicates distinct haplotypes between these regions.

| Species and family | Habitat | Genetic marker | Pollen dispersal | Seed dispersal | Genetic structure | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nrDNA | cpDNA | ||||||

| Ceiba pentandra MALVACEAE | Wet to dry | nrDNA (ITS), cpDNA (psbB–psbF) | Vertebrates (bats) Insects (moths) | Wind and water | Low | Low | Dick et al. (2007) |

| Cordia alliodora BORAGINACEAE | Wet to dry | nrDNA (ITS), cpDNA (trnH–psbA), cpSSR | Insects (moths) | Wind | Low | Low | Rymer et al. (2013) |

| Jacaranda copaia BIGNONIACEAE | Wet to dry | cpDNA (trnH–psbA, trnC–ycf6), nuSSR, cpSSR | Insects (large bees) | Wind | N.A. | Low | Scotti-Saintagne et al. (2013a) |

|

Ochroma pyramidale* MALVACEAE |

Wet | nrDNA (ITS), cpDNA (trnH–psbA, psbB–psbF, rbcL) | Vertebrates (bats) | Wind | High | High | Dick et al. (2013) |

|

Schizolobium parahyba FABACEAE |

Wet | nrDNA (ITS), cpDNA (trnH–psbA, trnL–trnF, matK) | Insects (bees) | Wind | Low | High | Turchetto-Zolet et al. (2012) |

|

Trema micrantha ULMACEAE |

Wet to dry | nrDNA (ITS), cpDNA (trnH–psbA, psbB–psbF, rbcL) | Small insects | Vertebrates (birds) | Low | Low | Dick et al. (2013) |

|

Ficus insipida subsp. insipida MORACEAE |

Wet | nrDNA (ITS), cpDNA (trnH–psbA) | Insects (wasps) | Vertebrates (fish, bats, others) | Low | High | This study |

Reduced sampling of species' distribution range; N.A., not available.

Genetic structure within Amazonia

Ficus insipida subsp. insipida shows strong genetic differentiation in the northern part of the Amazon Basin where SAMOVA groups V and VI containing the populations from north-eastern Peru (codes 38 and 39), Ecuador (32 and 33) and Bolivia (53), are separated from SAMOVA group VII containing the remaining populations. The plastid haplotype found at Sacta (population 53 in Bolivia) may represent an extreme case of ancestral polymorphism, or alternatively, it may reflect a recent long-distance dispersal event from Ecuador, the only other area where we observed its presence. Despite the extensive sampling carried out in this study, it is also possible that this haplotype is present in the intervening area in unsampled trees. While the three SAMOVA groups have widespread haplotypes (e.g. H1 and H5), they additionally contain a haplotype set which is restricted to this area and belongs to a phylogenetically distinct clade that diversified approximately 4.8 Ma (e.g. H4 and H11 of Ecuador, H15 and H19 of north-eastern Peru, and H12 of north-western and central Peru; Fig.2). Our results support the notion that pre-Pleistocene events underlie the initiation of genetic diversification in north-western Amazonia (Rull, 2008; Hoorn et al., 2010) because Amazonian lineages date from c. 12 Ma. The regional genetic differentiation found is likely to have been promoted by this long-residence time of F. insipida subsp. insipida in Amazonia, which means it was impacted upon by Andean uplift during the Miocene (c. 12 Ma) and early Pliocene (c. 4.5 Ma) (Hoorn et al., 1995, 2010) and the drying of Lake Pebas around 7 Ma (Hoorn et al., 2010).

Demographic history in Amazonia

Despite the genetic differentiation of some F. insipida subsp. insipida populations in Amazonia, there are widespread haplotypes in both plastid and ITS markers. In particular, the lower variation found in ITS and the presence of a single widespread haplotype in Amazonia (Fig.3) are suggestive of effective nuclear gene flow via pollen. Pollen of F. insipida is dispersed by tiny aganoid wasps of the genus Tetrapus (Machado et al., 2001). Wasps that pollinate monoecious fig species such as F. insipida have been reported to travel over distances of up to 14 km in the Neotropics (Nason et al., 1998) and up to more than 150 km in riparian vegetation of the Namib Desert, Namibia (Ahmed et al., 2009), indicating that pollen dispersal may succeed even among geographically distant individuals. Effective gene flow via pollen has often been reported in pioneer tree species, indicating that diverse organisms including small vertebrates and insects are able to pollinate over long distances (Table4).

The population differentiation of F. insipida subsp. insipida shown by the plastid DNA data in north-western Amazonia suggests that seed flow must in some cases have been more restricted. Nevertheless, negative values of Fu's FS and the results of mismatch distribution tests for both plastid and nuclear markers tentatively suggest that the SAMOVA group that contains most Amazonian populations (group VII) has experienced recent demographic expansion, most likely during the Pleistocene (Table3). Moreover, an interesting pattern of no genetic diversity is observed within the Bolivian populations for both markers. This uniformity, which is also present at the northernmost range in Mesoamerica for the plastid marker, probably reflects recent colonization events. This is consistent with palaeoecological data suggesting that the Amazon rain forest expanded south in the last 3000 years and that the current vegetation in the region (near population 54) may represent the southernmost distribution of rain forest over the last 50,000 years (Mayle et al., 2000). This southern margin of Amazonia has a marked dry season where monthly rainfall can be less than 100 mm for 4–6 months (Sombroek, 2001). If even drier conditions occurred during the Pleistocene, F. insipida subsp. insipida (and other rain forest trees) may have experienced range contraction at the southern end of its range and a reduction in effective population size. By contrast, the presence of populations containing high haplotype and nucleotide diversity (e.g. population 33 in Ecuador) for the plastid marker suggest that F. insipida subsp. insipida may have persisted in ‘refugia’ in wetter forest of north-western Amazonia.

The occurrence of widespread plastid haplotypes in some areas of the range of F. insipida subsp. insipida is consistent with episodes of effective seed dispersal. Fig fruits are important for frugivores in the Neotropics, and fish and bats are the primary seed dispersers of F. insipida (Banack et al., 2002). The mobility of these dispersal agents could help explain wide-scale dispersal. In particular, fish contribute significantly to the upstream dispersal of riparian plants (Reys et al., 2009), and fruit-eating bats are known to travel long distances from fruiting trees (Janzen, 1978; Pennington & de Lima, 1995). Successful establishment after dispersal is also favoured by the ecology of F. insipida, which is a light-demanding species that grows in riparian and disturbed areas (Berg, 2001; Banack et al., 2002).

Conclusions

Our phylogeographical study of F. insipida subsp. insipida showed marked genetic differentiation between Amazonian and Mesoamerican populations in the plastid DNA marker trnH–psbA. This contrasts with previous studies of other Neotropical trees – for example Cordia alliodora, Ceiba pentandra, Jacaranda copaia, Trema micrantha – that have little differentiation between these areas. Although all these species are pioneers, only F. insipida subsp. insipida is confined to ever-wet habitats. This suggests that the ecological characteristics of species, in this case a requirement of moist conditions for regeneration and survival, seem to be important drivers of phylogeographical patterns in Neotropical trees. The tolerance of seasonally dry climates in the other species suggests that seasonally dry tropical forest and savannas in northern South America did not represent long-term barriers to their migration. In contrast, areas with seasonally dry climates may have significantly restricted seed dispersal of F. insipida subsp. insipida. Further phylogeographical studies of widespread species will be needed to determine the extent to which ecological characteristics have determined historical migration patterns of other Neotropical tree species.

Within Amazonia, the plastid marker of F. insipida subsp. insipida also shows genetic differentiation among populations of the northern basin. Pre-Pleistocene events related to the changes of the landscape caused by the uplift of the Andes may be responsible for the initiation of population differentiation there. In contrast, the tentative evidence for demographic expansion in the rest of the basin, in particular the presence of genetically uniform populations across southern Amazonia, may indicate more recent colonization events, a scenario consistent with the palaeoecological data that indicates post-glacial rain forest expansion close to the southern margins of the forest.

Acknowledgments

This work was developed as part of a PhD based at the University of Leeds, and supported by a FINCyT studentship to the lead author, as well as by the School of Geography of the University of Leeds, Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh and the Davis Expedition Fund. We are grateful to Pablo Alvez, Aniceto Daza, Julio Irarica, Miguel Luza, Antonio Peña, Diego Rojas, Hugo Vasquez, Meison Vega and J. Yalder for assistance in the field; Alejandro Araujo, Luzmila Arroyo, Stephan Beck, Roel Brienen, Abel Monteagudo, Carlos Reynel and Guido Vasquez for helpful information in planning the field trips; and Alan Forrest, Michelle Hollingsworth and Ruth Hollands from the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh for training and assistance during the molecular lab work. We are also thankful to Otilene dos Anjos and Chris Dick for kindly sharing ITS sequences from Mexico, Costa Rica, Panama and Brazil. We thank Christine Niezgoda from the Field Museum in Chicago for providing access to herbarium material from Belize and Mexico. Research permits were provided by the Ministerio de Medio Ambiente y Agua in Bolivia (SERNAP-DMA-CAR-1232/10) and the Direccion General Forestal y de Fauna Silvestre in Peru (Resolucion Directorial No. 281-2010-AG-DGFFS-DGEFFS and No. 009-2014-MINAGRI-DGFFS-DGEFFS). K.G.D. and R.T.P. are supported by the National Environmental Research Council (grant number NE/I028122/1), and O.L.P. is supported by an ERC Advanced Grant and is a Royal Society-Wolfson Research Merit Award holder. We also thank the field stations and their station managers for logistical support. We thank Tim Baker, Dorothee Ehrich, the editor and three anonymous referees for helpful comments on earlier versions of this manuscript.

Biosketch

Eurídice Honorio is a researcher at the Instituto de Investigaciones de la Amazonia Peruana, and has recently obtained her PhD at the University of Leeds, UK. Her research focuses on tropical ecology and she is interested in understanding the ecological and historical processes determining tree species distribution in Amazonia.

Author contributions: E.H., T.P. and O.P. conceived the idea; E.H., M.P. and K.D. collected the samples; E.H. and M.P. carried out the DNA lab work; E.H. performed statistical analyses; E.H. and T.P. wrote the paper; and K.D., M.P, P.H. and O.P. contributed to the writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Appendix S1List of sampled sites for fresh and herbarium material of Ficus insipida subsp. insipida

Appendix S2 (a) Phylogram and (b) haplotype network for all plastid DNA haplotypes (H1–H19) of Ficus insipida subsp. insipida occurring in Mesoamerica and Amazonia.

Appendix S3 Haplotypes and detected polymorphic sites for trnH–psbA and ITS of Ficus insipida subsp. insipida.

References

- Ahmed S, Compton SG, Butlin RK. Gilmartin PM. Wind-borne insects mediate directional pollen transfer between desert fig trees 160 kilometers apart. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 2009;106:20342–20347. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902213106. &. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avise JC. Phylogeography: the history and formation of species. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Banack SA, Horn MH. Gawlicka A. Disperser- vs. establishment-limited distribution of a riparian fig tree (Ficus insipida) in a Costa Rican tropical rain forest. Biotropica. 2002;34:232–243. &. [Google Scholar]

- Berg CC. Moreae, Artocarpeae, and Dorstenia (Moraceae), with introductions to the family and Ficus and with additions and corrections to Flora Neotropica Monograph 7. Flora Neotropica. 2001;83:1–346. [Google Scholar]

- Berg CC, Avila MV. Kooy F. Ficus species of Brazilian Amazonia and the Guianas. Acta Amazonica. 1984;14(supplement):159–194. &. [Google Scholar]

- Cavers S. Dick CW. Phylogeography of Neotropical trees. Journal of Biogeography. 2013;40:615–617. &. [Google Scholar]

- Clement M, Posada D. Crandall KA. TCS: a computer program to estimate gene genealogies. Molecular Ecology. 2000;9:1657–1659. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2000.01020.x. &. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dexter KG, Pennington TD. Cunningham CW. Using DNA to assess errors in tropical tree identifications: how often are ecologists wrong and when does it matter? Ecological Monographs. 2010;80:267–286. &. [Google Scholar]

- Dexter KG, Terborgh JW. Cunningham CW. Historical effects on beta diversity and community assembly in Amazonian trees. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 2012;109:7787–7792. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203523109. &. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick CW. Heuertz M. The complex biogeographic history of a widespread tropical tree species. Evolution. 2008;62:2760–2774. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00506.x. &. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick CW, Bermingham E, Lemes MR. Gribel R. Extreme long-distance dispersal of the lowland tropical rainforest tree Ceiba pentandra L. (Malvaceae) in Africa and the Neotropics. Molecular Ecology. 2007;16:3039–3049. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03341.x. &. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick CW, Lewis SL, Maslin M. Bermingham E. Neogene origins and implied warmth tolerance of Amazon tree species. Ecology and Evolution. 2013;3:162–169. doi: 10.1002/ece3.441. &. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle JJ. Doyle JL. A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochemical Bulletin. 1987;19:11–15. &. [Google Scholar]

- Drummond A. Rambaut A. BEAST: Bayesian evolutionary analysis by sampling trees. BMC Evolutionary Biology. 2007;7:214–222. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-7-214. &. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupanloup I, Schneider S. Excoffier L. A simulated annealing approach to define the genetic structure of populations. Molecular Ecology. 2002;11:2571–2581. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2002.01650.x. &. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Excoffier L. Lischer HEL. Arlequin suite ver 3.5: a new series of programs to perform population genetics analyses under Linux and Windows. Molecular Ecology Resources. 2010;10:564–567. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2010.02847.x. &. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y-X. Statistical tests of neutrality of mutations against population growth, hitchhiking and background selection. Genetics. 1997;147:915–925. doi: 10.1093/genetics/147.2.915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentry AH. Tree species richness of upper Amazonian forests. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 1988;85:156–159. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.1.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez MA, Baraloto C, Engel J, Mori SA, Pétronelli P, Riéra B, Roger A, Thébaud C. Chave J. Identification of Amazonian trees with DNA barcodes. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e7483. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007483. &. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory-Wodzicki KM. Uplift history of the Central and Northern Andes: a review. Geological Society of America Bulletin. 2000;112:1091–1105. [Google Scholar]

- Haffer J. Speciation in Amazonian forest birds. Science. 1969;165:131–137. doi: 10.1126/science.165.3889.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoorn C, Guerrero J, Sarmiento GA. Lorente MA. Andean tectonics as a cause for changing drainage patterns in Miocene northern South America. Geology. 1995;23:237–240. &. [Google Scholar]

- Hoorn C, Wesselingh FP, ter Steege H, Bermudez MA, Mora A, Sevink J, Sanmartín I, Sanchez-Meseguer A, Anderson CL, Figueiredo JP, Jaramillo C, Riff D, Negri FR, Hooghiemstra H, Lundberg J, Stadler T, Särkinen T. Antonelli A. Amazonia through time: Andean uplift, climate change, landscape evolution, and biodiversity. Science. 2010;330:927–931. doi: 10.1126/science.1194585. &. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janzen DH. A bat-generated fig seed shadow in rainforest. Biotropica. 1978;10:121. [Google Scholar]

- Lemes M, Dick C, Navarro C, Lowe A, Cavers S. Gribel R. Chloroplast DNA microsatellites reveal contrasting phylogeographic structure in mahogany (Swietenia macrophylla King, Meliaceae) from Amazonia and Central America. Tropical Plant Biology. 2010;3:40–49. &. [Google Scholar]

- Linares-Palomino R, Oliveira-Filho AT. Pennington RT. Neotropical seasonally dry forests: diversity, endemism, and biogeography of woody plants. In: Dirzo R, Young HS, Mooney HA, Ceballos G, editors; Seasonally dry tropical forests: ecology and conservation. Washington, DC: Island Press/Center for Resource Economics; 2011. pp. 3–21. (ed. by ) &. [Google Scholar]

- Machado CA, Jousselin E, Kjellberg F, Compton SG. Herre EA. Phylogenetic relationships, historical biogeography and character evolution of fig-pollinating wasps. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2001;268:685–694. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2000.1418. &. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddison WP. Maddison DR. Mesquite: a modular system for evolutionary analysis. 2001. &. Version 2.74. Available at: http://mesquiteproject.org. [Google Scholar]

- Mayle FE, Burbridge R. Killeen TJ. Millennial-scale dynamics of southern Amazonian rain forests. Science. 2000;290:2291–2294. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5500.2291. &. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nason JD, Herre EA. Hamrick JL. The breeding structure of a tropical keystone plant resource. Nature. 1998;391:685–687. &. [Google Scholar]

- Paradis E. pegas: an R package for population genetics with an integrated-modular approach. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:419–420. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradis E, Claude J. Strimmer K. APE: analyses of phylogenetics and evolution in R language. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:289–290. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg412. &. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennington RT. de Lima HC. Two new species of Andira (Leguminosae) from Brazil and the influence of dispersal in determining their distributions. Kew Bulletin. 1995;50:557–566. &. [Google Scholar]

- Pennington RT, Ratter JA. Lewis GP. An overview of the plant diversity, biogeography and conservation of Neotropical savannas and seasonally dry forests. In: Pennington RT, Lewis GP, Ratter JA, editors; Neotropical savannas and seasonally dry forests: plant biodiversity, biogeography and conservation. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2006. pp. 1–29. (ed. by ) &. The Systematics Association special volume, No. 69. [Google Scholar]

- Poelchau MF. Hamrick JL. Comparative phylogeography of three common Neotropical tree species. Journal of Biogeography. 2013;40:618–631. &. [Google Scholar]

- Pons O. Petit RJ. Measuring and testing genetic differentiation with ordered versus unordered alleles. Genetics. 1996;144:1237–1245. doi: 10.1093/genetics/144.3.1237. &. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posada D. jModelTest: phylogenetic model averaging. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2008;25:1253–1256. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msn083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reys P, Sabino J. Galetti M. Frugivory by the fish Brycon hilarii (Characidae) in western Brazil. Acta Oecologica. 2009;35:136–141. &. [Google Scholar]

- Rull V. Speciation timing and neotropical biodiversity: the Tertiary–Quaternary debate in the light of molecular phylogenetic evidence. Molecular Ecology. 2008;17:2722–2729. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.03789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rymer PD, Dick CW, Vendramin GG, Buonamici A. Boshier D. Recent phylogeographic structure in a widespread ‘weedy’ Neotropical tree species, Cordia alliodora (Boraginaceae) Journal of Biogeography. 2013;40:693–706. &. [Google Scholar]

- Salo J, Kalliola R, Hakkinen I, Makinen Y, Niemela P, Puhakka M. Coley PD. River dynamics and the diversity of Amazon lowland forests. Nature. 1986;322:254–258. &. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider S. Excoffier L. Estimation of past demographic parameters from the distribution of pairwise differences when the mutation rates vary among sites: application to human mitochondrial DNA. Genetics. 1999;152:1079–1089. doi: 10.1093/genetics/152.3.1079. &. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scotti-Saintagne C, Dick CW, Caron H, Vendramin GG, Troispoux V, Sire P, Casalis M, Buonamici A, Valencia R, Lemes MR, Gribel R. Scotti I. Amazon diversification and cross-Andean dispersal of the widespread Neotropical tree species Jacaranda copaia (Bignoniaceae) Journal of Biogeography. 2013a;40:707–719. &. [Google Scholar]

- Scotti-Saintagne C, Dick CW, Caron H, Vendramin GG, Guichoux E, Buonamici A, Duret C, Sire P, Valencia R, Lemes MR, Gribel R. Scotti I. Phylogeography of a species complex of lowland Neotropical rain forest trees (Carapa, Meliaceae) Journal of Biogeography. 2013b;40:676–692. &. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw J, Lickey EB, Schilling EE. Small RL. Comparison of whole chloroplast genome sequences to choose noncoding regions for phylogenetic studies in angiosperms: the tortoise and the hare III. American Journal of Botany. 2007;94:275–288. doi: 10.3732/ajb.94.3.275. &. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sombroek W. Spatial and temporal patterns of Amazon rainfall: consequences for the planning of agricultural occupation and the protection of primary forests. Ambio. 2001;30:388–396. doi: 10.1579/0044-7447-30.7.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turchetto-Zolet AC, Cruz F, Vendramin GG, Simon MF, Salgueiro F, Margis-Pinheiro M. Margis R. Large-scale phylogeography of the disjunct Neotropical tree species Schizolobium parahyba (Fabaceae–Caesalpinioideae) Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 2012;65:174–182. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2012.06.012. &. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White TJ, Bruns T, Lee S. Taylor J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In: Innis MA, Gelfand DH, Shinsky JJ, White TJ, editors; PCR protocols: a guide to methods and applications. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1990. pp. 315–322. (ed. by ) &. [Google Scholar]

- Wright S. Isolation by distance. Genetics. 1943;28:114–138. doi: 10.1093/genetics/28.2.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerega NJC, Clement WL, Datwyler SL. Weiblen GD. Biogeography and divergence times in the mulberry family (Moraceae) Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 2005;37:402–416. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2005.07.004. &. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1List of sampled sites for fresh and herbarium material of Ficus insipida subsp. insipida

Appendix S2 (a) Phylogram and (b) haplotype network for all plastid DNA haplotypes (H1–H19) of Ficus insipida subsp. insipida occurring in Mesoamerica and Amazonia.

Appendix S3 Haplotypes and detected polymorphic sites for trnH–psbA and ITS of Ficus insipida subsp. insipida.