Abstract

Background

In the testis, thyroid hormone (T3) regulates the number of gametes produced through its action on Sertoli cell proliferation. However, the role of T3 in the regulation of steroidogenesis is still controversial.

Methods

The TRαAMI knock-in allele allows the generation of transgenic mice expressing a dominant-negative TRα1 (thyroid receptor α1) isoform restricted to specific target cells after Cre-loxP recombination. Here, we introduced this mutant allele in both Sertoli and Leydig cells using a novel aromatase-iCre (ARO-iCre) line that expresses Cre recombinase under control of the human Cyp19(IIa)/aromatase promoter.

Findings

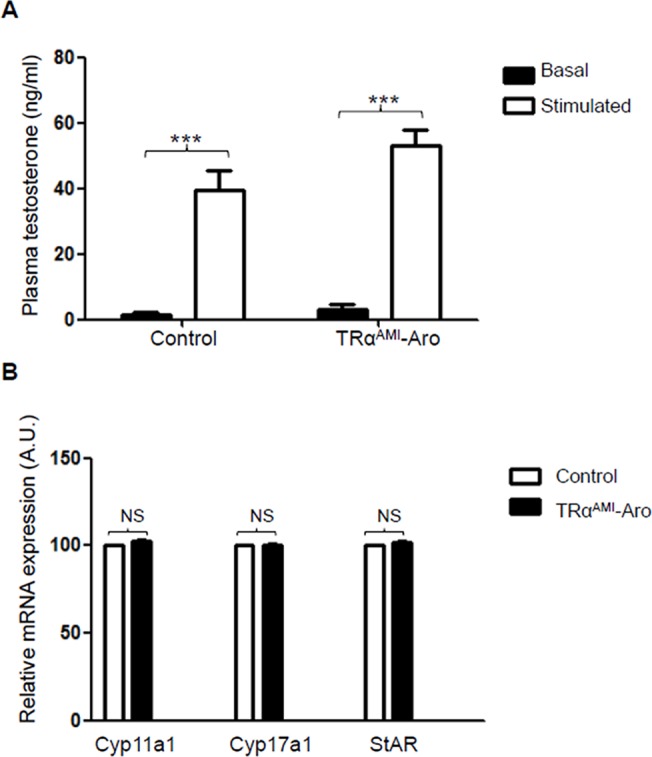

We showed that loxP recombination induced by this ARO-iCre is restricted to male and female gonads, and is effective in Sertoli and Leydig cells, but not in germ cells. We compared this model with the previous introduction of TRαAMI specifically in Sertoli cells in order to investigate T3 regulation of steroidogenesis. We demonstrated that TRαAMI-ARO males exhibited increased testis weight, increased sperm reserve in adulthood correlated to an increased proliferative index at P3 in vivo, and a loss of T3-response in vitro. Nevertheless, TRαAMI-ARO males showed normal fertility. This phenotype is similar to TRαAMI-SC males. Importantly, plasma testosterone and luteinizing hormone levels, as well as mRNA levels of steroidogenesis enzymes StAR, Cyp11a1 and Cyp17a1 were not affected in TRαAMI-ARO.

Conclusions/Significance

We concluded that the presence of a mutant TRαAMI allele in both Leydig and Sertoli cells does not accentuate the phenotype in comparison with its presence in Sertoli cells only. This suggests that direct T3 regulation of steroidogenesis through TRα1 is moderate in Leydig cells, and that Sertoli cells are the main target of T3 action in the testis.

Introduction

Thyroid hormones, mainly represented by triiodothyronine (T3), and their nuclear receptors play important roles in the development, differentiation and function of various organs, including the male reproductive system [1,2]. The THRA/NR1A1 and THRB/NR1A2 genes encode the T3 nuclear receptors (TRs): TRα1 (thyroid hormone receptor α1) for THRA, and TRβ1 and TRβ2 for THRB. TRα1 and TRβ1 are expressed ubiquitously. In the testes, T3 is of particular importance as it regulates the number of gametes produced and the size of the gonad [3]. It has been proposed that T3 regulates both Sertoli cells (SC), which are specialized supporting cells for germ cells, and Leydig cells (LC) that produce testosterone. The T3 effect related to SC is well-known. Indeed, pharmacological approaches [4–6] led to the conclusion that T3 controls post-natal SC proliferation in vivo. Thereafter, the functional study with homozygous mice bearing a null deletion of the THRA gene (TRαNull/Null mice) showed that TRα1 mediates this control [7]. More recently, we demonstrated, using mice with SC-specific TRα1 receptor dominant-negative expression (TRαAMI-SC mice) [8,9], that T3 exerts this regulation in a direct cell-autonomous manner. Adult LC are the primary source of androgens in mature mammalian testes, but controversy exists regarding T3-regulation of steroidogenesis. LC arise from pluripotent mesenchymal precursors (for review see [10,11]), and start to differentiate at post-natal day 14 (P14) in rats [12] and P10 in mice [13], and gradually mature to adult LC just before puberty. The effect of T3 on LC has been mostly investigated in rat species, using in vitro and in vivo pharmacological studies. It is established that T3 is important for mesenchymal stem cell proliferation and differentiation into LC. Indeed, in vivo, exogenous T3 in neonate rats leads to an increase in differentiated LC numbers and influences their proliferation [14]. The overall impact on steroidogenesis at adulthood is still a matter of debate. In vitro studies using LC cultures suggest that T3 directly increases steroidogenesis [15]. In rats with pharmacologically induced hypothyroidism during post-natal development, it has been observed that peripheral testosterone concentrations were unchanged [4,16,17]. However, studies on neonatal hypothyroid rats showed a decrease in blood testosterone levels at adulthood [18,19]. Thus, there is a debate about possible T3 regulation of steroidogenesis. Unfortunately, no genetic evidence supports this matter. In the two previously cited transgenic mouse models (TRαNull/Null and TRαAMI-SC), we showed that testosterone levels were unchanged. Nevertheless, as the modification was restricted to SC in TRαAMI-SC mice and ubiquitously present in TRαNull/Null mice, these two transgenic lines were not well suited to investigate direct T3 regulation of steroidogenesis by this receptor.

The ubiquitous TRα1 receptor is present in rat LC [20], but no data are yet available in mice. Following our functional study in TRαAMI-SC mice [8], we aimed to investigate the role of the TRα1 receptor in the regulation of steroidogenic activity using a novel functional Cre transgenic mouse, the aromatase-iCre (ARO-iCre), that we generated in our laboratory and characterized for this study. After demonstrating the pertinence of this line for Cre-loxP recombination in both SC and LC, we produced TRαAMI-ARO mice expressing dominant negative TRαAMI selectively in SC and LC and compared their phenotypes with the previously established TRαAMI-SC line at cellular and endocrine levels. The present study confirms our findings, namely that T3 influences Sertoli cell proliferation through its TRα1 receptor. Moreover, we showed that the expression of dominant-negative TRαAMI in LC does not influence testosterone production in adulthood.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Mice were maintained under standard conditions of light (12 h light, 12 h darkness) and temperature (21–23°C) with ad libitum access to food and water. All animal studies were conducted in accordance with the guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals issued by the French Ministry of Agriculture and with the approval of a local ethical review committee, under project number 2011-09-10 (Comité d’Ethique en Expérimentation Animale Val de Loire- n°19). The TRαAMI-ARO line was produced and investigations were performed at the same time as the TRαAMI-SC, except for steroidogenic enzyme determination. Mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation under anesthesia with ketamine (87 μg/g body weight) and xylazine (13 μg/g body weight) by intraperitoneal injection. All efforts were made to minimize animal stress and suffering.

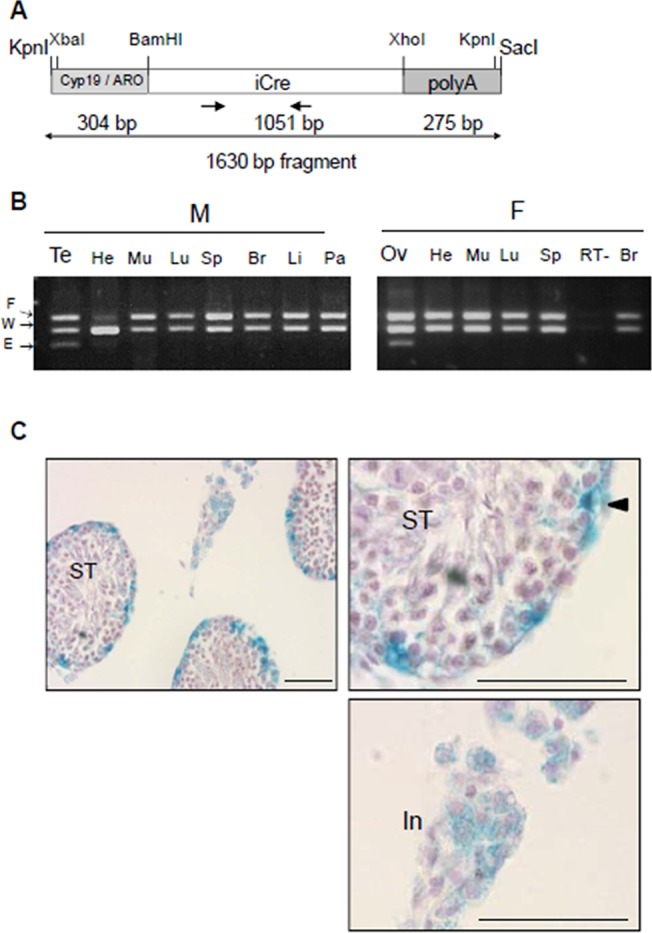

Production of aromatase-iCre (ARO-iCre) line

The aromatase-iCre transgene was generated by placing the cDNA encoding a mammalian codon-improved Cre recombinase (iCre: [21,22]) followed by an SV40 poly(A) signal under control of the human Cyp19/aromatase(IIa)-278 promoter cloned by Hinshelwood et al. This promoter is sufficient to mediate restrictive transgenic expression in the ovary and the testis [23]. This region contains two response elements, a steroidogenic factor 1-(SF1)-site and a CRE-like sequence binding CREB protein, critical for cAMP induction of human Cyp19/aromatase promoter activity.

To obtain a Cyp19/aromatase-iCre plasmid, the pUChGX plasmid containing the Cyp19/aromatase(IIa)-278 promoter (a 304 bp fragment stretching between position -278 of 5’-flanking DNA and +26 of untranslated exon IIa) was HindIII digested, blunted and BamHI digested. The fragment was cloned into the blunted XbaI and BamHI sites of the pBlue-iCre vector. Next, a fragment containing the SV40 poly(A) signal was obtained by HindIII digestion, end blunting and KpnI digestion of the pGEM3Zf-polyA (SV40) plasmid and inserted into the blunted XhoI and KpnI sites of the Cyp19/aromatase-iCre vector. All DNA constructs were confirmed by sequencing. The 1,630 bp purified fragment containing the Cyp19/aromatase-iCre-polyA(SV40) construction was obtained through KpnI and SacI digestion (Fig. 1A). The transgene was injected into the pronuclei of fertilized eggs from mice with a hybrid DBA/B6 genetic background. Three founder animals (two males and one female) with genomic transgene integration were detected by PCR as described [24]. Specificity of ARO-iCre loxP excision was investigated at tissue level by genomic PCR and at cellular level using Cre-loxP reporter mice. Offspring of all 3 founders targeted Cre specifically to somatic cells of the gonads, without producing excision in germ cells. We chose the strain that transmitted the transgene with highest efficiency to the descendants. This line was called ARO-iCre.

Fig 1. Production and characterization of ARO-iCre transgenic mouse line.

(a) Schematic diagram of the DNA construct used for producing ARO-iCre mice. The mammalian codon-improved Cre recombinase (iCre, 1051 bp; white box) followed by an SV40 poly(A) signal cassette (right grey box) is controlled by 304 bp of the human Cyp19/aromatase(IIa)-278 promoter (left grey box). Arrows indicate position and direction of primers. Oligonucleotide sequences are in Table 1. (b) Cre excision is restricted to ovaries (Ov) and testes (Te) of iCre+/0;IGF1Rflox/WT mice. The excision was only observed in gonads, not in other tissues (He, heart; Mu, muscle; Lu, lung; Sp, spleen; Br, brain; Li, liver; Pa, pancreas) from males (M) and females (F). RT-, negative control (testis cDNA without RT). PCR detected wild-type (W, 256 bp) and floxed (F, 312 bp) alleles in all tissues, and the excised allele (E, 204 bp) exclusively in gonads. (c) Cre recombinase activity detected in somatic cells of testes in adult ARO-iCre males. After crossing the ARO-iCre mice with a ROSA26 Cre reporter mouse, β-galactosidase activity was detected in both SC and LC. No activity was present in germ cells. Right micrograph, low magnification; left micrographs, details in higher magnification. ST, seminiferous tubules. In, interstitium. Arrow head points to SC. Bar represents 50 μm.

Generation of TRαAMI-ARO and control mice

The TRαAMI allele generated by Quignodon et al. [25] encodes a TRα1 receptor with a point mutation changing a leucine to an arginine in the AF-2 domain of the receptor (L400R). This mutation prevents the recruitment of histone acetyltransferase coactivators, while interaction with histone deacetylase corepressors is preserved, resulting in dominant-negative activity. The advantage of this mutation is that repression of transcription is maintained even in the presence of T3, with heterozygosity being sufficient to achieve the dominant-negative effect. This mutation is activated by Cre-loxP recombination [25]. According to the procedure we used to establish TRαAMI-SC from AMH-Cre and TRαAMI/AMI lines [8], we crossed homozygous TRαAMI/AMI mice (B6/129Sv genetic background) with hemizygous ARO-iCre mice to obtain TRαAMI/WT;ARO-iCre+/0 mice, hereafter called TRαAMI-ARO. These double transgenic mice efficiently express the targeted dominant-negative TRα1 isoform in SC and in LC. TRαAMI/WT littermates that tested negative for ARO-iCre were used as control mice throughout this study. Genotyping of the mice was performed using the primers for iCre and TRαAMI alleles listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Primers for PCR genotyping of TRαAMI-ARO line and for RT-PCR of TRα1 [27] and actin genes.

| Gene | Forward PCR primer (5’-3’) | Reverse PCR primer (5’-3’) | Temp. | Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TRαAMI | GGTTGGTCCAAGGAAAGACA | GCTTCTTGCCGTTTGAAGAC | 60°C | 520 bp |

| iCre | CCTGGAAGATGCTCCTGTCTG | AGGGTGTTGTAGGCAATGCC | 58°C | 391 bp |

| Actin | TACGACCAGAGGCATACAGG | TGACCCAGATCATGTTTGAGA | 55°C | 411 bp |

| TRα1 | TGCCTTTAACCTGGATGACAC | TCGACTTTCATGTGGAGGAAG | 60°C | 720 bp |

Fertility, testis weight and sperm reserve

TRαAMI-ARO mice and their controls were sacrificed and one testis weighed and frozen for sperm reserve determination as described for TRαAMI-SC [8]. Briefly, testes were disrupted in 3 ml of L15 medium (Gibco-Invitrogen) and sonicated for 30 s. Remaining sperm nuclei were counted using a hemocytometer method. These nuclei contain spermatozoa and stage II-VII elongating spermatid nuclei, and their number defines the testicular sperm reserve [3]. Each male (n = 10 per genotype) was mated with two primiparous Swiss female mice. The birth dates were noted to detect a putative delay in mating, and pups were counted at birth.

Histology

Testes were fixed in Bouin’s solution and embedded in paraffin. Sections 4 μm thick were stained with hematoxylin for microscopic observation of seminiferous tubule organization.

Determination of SC proliferation index in vivo and in vitro

Procedures were previously described for TRαAMI-SC [8]. Briefly, TRαAMI-ARO mice at P3 were injected with 50 μg per gram of body weight of 5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine (BrdU, Sigma) 3 h before sacrifice. After fixation in Bouin’s solution and embedding in paraffin, BrdU immunodetection was performed (monoclonal antibody from Roche; 1:200). A total of 1000 proliferating (BrdU-stained) and non-replicating (BrdU-negative) SC were counted per animal using Histolab analysis software (GT Vision). For organotypic cultures, TRαAMI-ARO testes at P3 were cut into small pieces. Culture conditions were as described previously [26], except that T3 (0.2 μM) or a vehicle (1X PBS with 0.025 N NaOH) was added to the medium. Explants were cultured for 72 h and BrdU was added at a final concentration of 0.01 mg/ml after 69 h (i.e. 3 h prior to fixation, exactly as in vivo). The explants were then fixed in Bouin’s fixative and processed for BrdU staining.

RNA extraction, reverse transcription and PCR for TRα1 detection

Total RNA was isolated from whole testes at post-natal day 0 (P0), 3 (P3), 10 (P10), 22 (P22) or adulthood (pool of 3 animals per age) and from Sertoli and Leydig cell-enriched fractions obtained at P10 and prepared as described previously [8]. RNA (1 μg) was reverse transcribed using the RNeasy kit (with DNAse I) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Qiagen). A sample with RNA but without reverse transcriptase (RT-) served as a negative control. TRα1 mRNA was detected as described [27] by classical PCR using primers and hybridization temperatures as described in Table 1. The β-actin gene was used to control RNA quality.

Quantitative real-time PCR for analysis of testicular steroidogenesis

Three key steroidogenic genes were analyzed using the TaqMan assay, with primers and probes inventoried by Applied Biosystems: StAR (Steroidogenic acute regulatory protein), Mm00441558_m1; Cyp11a1/P450scc (cytochrome P450 side-chain cleavage enzyme), Mm00490735_m1; Cyp17a1/P450c17 (steroid 17 α hydroxylase/17,20 lyase cytochrome P450c17), Mm00484040_m1. PCR reagents were purchased from Applied Biosystems and real-time PCR carried out in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions, in a final volume of 25 μl. Samples were analyzed in triplicate. Fluorescence was detected on an iCycler BioRad apparatus. Negative controls (RT- and H20) were included for every primer/probe combination. Normalization was performed using two internal standards, β-actin (Mm00607939_s1) and Gapdh (m99999915_g1) from the same sample. The normalized cDNA was compared between the two genotypes.

Blood collection and hormone assays

Around 500 μl of blood were obtained by retro-orbital sampling in anesthetized mice (with ketamine 87 μg/g body weight and xylazine 13 μg/g body weight; intraperitoneal injection) and collected in a tube containing EDTA (0.13 M). For plasma testosterone determinations, adult mice were treated with an intraperitoneal injection of 15 IU of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) (Chorulon). Blood was collected before (basal level) and 2 h after injection (stimulated level). Plasma was stored at -20°C until tritium-based testosterone competitive radioimmunoassays. RIA are carried out regularly in the lab and were performed as described [8]. The sensitivity of the assay was 0.125 ng/ml. The intra-assay coefficient of variation was 7.5%. Briefly, samples (two different dilutions per sample) or testosterone dilutions (to determine the range) were incubated for 1 h at 40°C (0.1 M phosphate buffer, 0.1% gelatin) with tritiated testosterone plus the anti-testosterone antibody. A secondary antibody was added and the mixtures incubated overnight at 4°C. Subsequent immuno-precipitation was performed with PEG (polyethylene glycol) 4000 and the radioactivity was counted (Packard C2900 TriCarb). Plasma LH (luteinizing hormone) levels were determined in a volume of 50 μl using the immuno-enzymatic LH-DETECTkit for rodents from ReprodPharm, according to manufacturer’s instructions, except that the antibody was used at 4°C overnight, with tetramethylbenzidine as the substrate.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as mean ± SEM. To compare means between two groups, Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney U test, in case of differences in variance (Fisher’s exact test), was used. Other comparisons were performed using a two-way ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni post-hoc test. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Generation of an ARO-iCre transgenic strain

ARO-iCre transgenic mice were generated as indicated in materials and methods (Fig. 1A). We characterized the ARO-iCre line first by crossing iCre positive animals with mice carrying a floxed conditional gene. Monitoring Cre excision with the TRαAMI allele is technically challenging because it only diverges from the wild-type TRα1 by a single amino acid mutation [25]. Therefore, we used the floxed allele of the insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor (IGF1R) gene [28–30] for characterization. IGF1R excision was analyzed in various organs of iCre+/0;IGF1Rflox/WT pups using triplex PCR on genomic DNA [24]. We found the excised allele exclusively in samples from male and female gonads (Fig. 1B), confirming the promoter characterization of Hinshelwood et al. [23] and demonstrating the usefulness of the transgenic line for functional gonad investigation. In particular, we did not observe any excision in the brain (Fig. 1B), nor in the pituitary (not shown). To characterize the ARO-iCre transgenic line at cellular level, we crossed it to mice containing the ROSA26 Cre reporter (R26R) allele [31]. β-galactosidase (β-gal) activity resulting from loxP recombination at the R26R locus by ARO-iCre recombinase was observed at the periphery of the seminiferous tubules in SC and in the interstitium containing LC (Fig. 1C). In contrast, no activity was present in germ cells. β-galactosidase (β-gal) activity was also observed in most interstitial cells and seminiferous tubules at P3 (S1 Fig.), in accordance with Cyp19/aromatase expression in testes.

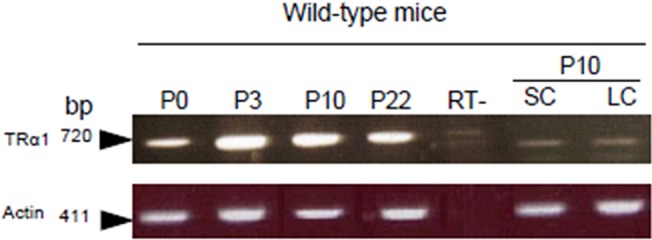

Next we demonstrated that the TRα1 gene was expressed in mice by LC and SC during post-natal development (Fig. 2).

Fig 2. RT-PCR detection of TRα1 mRNA in testes during post-natal development in wild-type mice.

TRα1 mRNA (720 pb) was present in whole testes from birth (P0) to P22, and in SC- and LC-enriched fractions prepared from testes of wild-type mice at P10. TRα1-specific primers were described previously [27] (Table 1). Actin mRNA (411 pb) was detected to check RNA quality. RT-, control without RT.

We then aimed to produce transgenic mice with impaired function of this receptor in both cell types to compare these mice with the previously established TRαAMI-SC [8]. After having checked that ARO-iCre was useful for Cre-loxP excision in both SC and LC cells (Fig. 1C), we produced TRαAMI-ARO double transgenic mice as described in materials and methods. Littermates with the unrecombined TRαAMI allele and negative for ARO-iCre served as control mice. Testicular function was then studied at physiological, cellular and hormonal levels. A summary of the results is presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Physiological, endocrine and cellular characteristics in TRαAMI-ARO (present study), TRαAMI-SC and TRαNull/Null transgenic lines.

| Mutant strain | TRαNull/Null | TRαAMI-SC | TRαAMI-ARO |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mutation | Gene knockout [27] | Dominant negative knock-in [25] | Dominant negative knock-in [25] |

| References (phenotype) | [7, 8] | [8] | Present study |

| Target cells | ubiquitous | Sertoli | Sertoli & Leydig |

| Adult testis weight (% change) | +26.7% *** | +14.2% *** | +16.5% *** |

| Testicular sperm reserve | increased *** | increased ** | increased *** |

| SC proliferation index (P3) | increased *** | increased *** | increased *** |

| Histology of seminiferous tubules | unchanged [7] | unchanged | unchanged |

| Blood testosterone level (basal and stimulated) | normal | normal | normal |

| Blood LH level | ND | ND | normal |

**P < 0.01;

***P < 0.001;

ND, not determined.

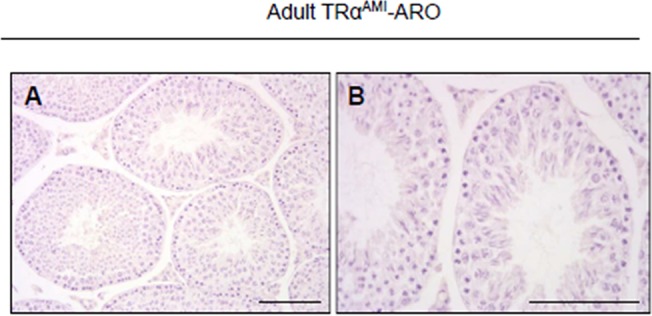

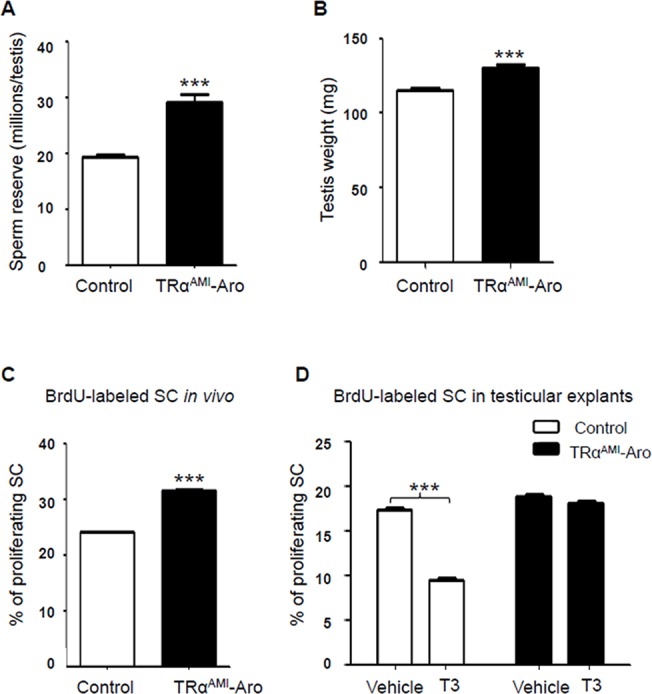

TRαAMI-ARO males present increased sperm reserve and normal fertility

We were particularly interested to find out whether the presence of the TRαAMI allele in both SC and LC has the same consequences in adults as in TRαAMI-SC males, in which testis weight was high due to an increase in sperm reserve. Adult TRαAMI-ARO males were normally fertile (TRαAMI-ARO, 12.6 ± 1.2 pups per male; control, 12.0 ± 1.6 pups per male; n = 10 males per genotype). Histological analyses revealed no visible alteration of the seminiferous tubule epithelium (Fig. 3). In TRαAMI-ARO males we observed a significant increase (P < 0.001) in the total testicular sperm reserve (Fig. 4A) and in testis weight (Fig. 4B) in comparison with the control.

Fig 3. Histological sections of adult TRαAMI-ARO testes at low (a) and high (b) magnification.

Seminiferous tubules were fully developed in TRαAMI-ARO. Their epithelium exhibited normal structure and organization. Hematoxylin staining. Bar represents 100 μm.

Fig 4. Whole testicular sperm reserve and testis weight in adult TRαAMI-ARO, and percentage of proliferating SC in TRαAMI-ARO at P3 in vivo and in testicular explants using organotypic in vitro cultures with or without exogenous T3.

We observed a significant increase in whole testicular sperm reserve (a) and in testis weight (b) (***P < 0.001; n = 15 for controls and n = 16 for TRαAMI-ARO group). Data are shown as mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses were performed using Student’s t-test. White bars, control; black bars, TRαAMI-ARO (a, b). After BrdU immunohistochemical labeling, BrdU negative and BrdU positive SC were counted and the SC proliferation index was calculated. (c) When BrdU was injected in vivo 3 h before sacrifice, proliferation of Sertoli cells increased in P3 testes of TRαAMI-ARO mice in comparison with the control (***P < 0.001; n = 5 animals for each genotype). (d) When BrdU was added in vitro 3 h before the end of the organotypic cultures of P3 testicular explants, the SC proliferation index significantly decreased in the control in presence of T3 compared with vehicle (***P < 0.001, n = 6). In contrast, T3 had no effect on SC proliferative index in TRαAMI-ARO mice (P > 0.05, n = 5). Data are shown as mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses: two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post-hoc test. White bars, control; black bars, TRαAMI-ARO.

SC proliferation index increased in TRαAMI-ARO just as TRαAMI-SC mice

In TRαAMI-SC males, we previously observed that the increase in sperm reserve resulted from an augmentation in the SC proliferation rate during post-natal development. The next step was to ask if the TRαAMI allele in both SC and LC accentuate these cellular changes. To reach this aim, we investigated the percentage of SC incorporating BrdU within 3 hours at P3, in vivo and in vitro. In vivo, we found the SC proliferation index was significantly higher (P < 0.001) in TRαAMI-ARO testes than in control testes at P3 (Fig. 4C). We then wanted to know if the regulation exerted by TRα1 on the SC proliferation index described above was modulated in the presence of T3. To do so, we used organotypic cultures in which SC proliferation was measured in testes explanted at P3, in the presence or absence of exogenous T3. In organotypic cultures, SC proliferation without T3 (vehicle) was similar for TRαAMI-ARO and control testes, indicating that the TRα1 dominant-negative did not alter SC proliferation in the absence of T3 in vitro (Fig. 4D). As expected, addition of T3 significantly (P < 0.001) decreased (approximately two-fold) SC proliferation in the controls, whereas this response was fully abolished in TRαAMI-ARO.

Testosterone and LH levels are unchanged in adult TRαAMI-ARO mice

We then tried to find out whether the TRαAMI allele present in LC affects their steroidogenic activity, compared with the TRαAMI-SC phenotype, where plasma testosterone levels were unchanged. For this, we measured basal and hCG-stimulated testosterone levels. Both basal and hCG-stimulated testosterone levels were similar in adult TRαAMI-ARO and the controls, with significant effects of hCG stimulation in both lines, as could be expected (Fig. 5A).

Fig 5. Plasma testosterone levels in adult TRαAMI-ARO males, in basal conditions and after hCG stimulation, compared with control mice and mRNA levels of Cyp11a1/P450ssc, Cyp17a1/P450c17 and StAR in TRαAMI-ARO testes.

(a) In both TRαAMI-ARO (11 males) and controls (9 males), hCG induced a significant increase (***P < 0.001) in testosterone secretion, as expected. Plasma testosterone levels were unchanged in TRαAMI-ARO compared with the control. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. Two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post-hoc test. Black bars, basal levels; white bars, hCG stimulated. (b) The amount of cDNA of 3 steroidogenic genes (Cyp11a1/P450ssc, Cyp17a1/P450c17 and StAR) was compared in TRαAMI-ARO (black bars) and control males (white bars). For each genotype, 6 mice were tested in triplicate using TaqMan quantitative real-time PCR, as described in materials and methods. Normalization was performed with two housekeeping genes, β-actin and GAPDH, that both exhibited similar expression among samples. mRNA expression is presented as percent of mean control level. A non-parametric test (Mann-Whitney) was used for statistical analysis. NS: not significant.

To consolidate the androgenic status of TRαAMI-ARO, we investigated mRNA levels of steroidogenesis enzymes P450c17 (Cyp17a1), P450scc (Cyp11a1) and StAR per testis, which were all unaffected (Fig. 5B). Moreover, as expected, LH levels were similar in TRαAMI-ARO males and control males (0.85 ng/ml ± 0.4 in TRαAMI-ARO versus 0.63 ng/ml ± 0.2 in control, n = 6 for each genotype).

Discussion

A new genetic mouse model to study testicular somatic cells

We previously used the TRαAMI allele that induces constitutive T3-regulated gene repression by preventing interaction with coactivators [25,32]. We used the TRαAMI allele to demonstrate that T3 controls post-natal SC proliferation through TRα1 in a direct and cell-autonomous manner during early post-natal development [8]. Here, we present the introduction of this conditional dominant-negative allele in post-natal testes in both LC and SC compartments using the novel ARO-iCre transgenic mouse strain generated in our lab.

We showed that Cre activity of the ARO-iCre line was restricted to male and female gonads, confirming the highly specific Cyp19/aromatase(IIa)-278 promoter expression profile [23]. In contrast, other available gonad-specific Cre transgenic lines driving recombinase expression in steroidogeneic cells, are also active in cells from others tissues, namely adrenal tissue and hindbrain for the Cyp11a-GC (GFP-Cre) line [33], and male adrenal tissue for the Cyp17-iCre line [34]. In the literature, the anti-Müllerian hormone type 2 receptor (AMHR2)-Cre line [35] was mostly used to target conditional gene mutation in LC, for instance for the genes coding for SF1 [36], androgen receptors [37] or ALK3 [38], but also in SC, for example to impact WNT/beta-catenin signaling [39].

We characterized testicular iCre activity using a ROSA26 Cre reporter mouse. We detected loxP recombination in both SC and LC at P3, an age when SC are highly proliferative. This result is fully coherent with the aromatase expression profile observed in post-natal testes. Aromatase activity corresponds to the irreversible conversion of androgens into estrogens [40]. In LC, this activity increases progressively from birth to puberty as the testis matures [41,42]. In SC, which only express aromatase during post-natal development, activity decreased 2-fold from birth to 2 weeks of age. Consequently, estrogens are almost exclusively produced by LC during adulthood [43].

In our model, we observed a phenotype similar to TRαAMI-SC obtained with AMH-Cre which is known to target all SC, suggesting that the ARO-iCre is rapidly active in the majority of post-natal SC. The absence of ARO-iCre activity in male germ cells, evidenced by a lack of β-galactosidase staining and no transmission of the deleted allele to offspring (data not shown), is in full agreement with Hinshelwood et al. [23], who showed that the Cyp19/aromatase(IIa)-278 promoter did not target Cre in oocytes.

Phenotype of TRαAMI-ARO males and parallel with TRαAMI-SC

We compared the TRαAMI-ARO line, which presents a constitutive repression of the T3/TRα1 pathway in LC and SC—a kind of local hypothyroidism—with the TRαAMI-SC and TRαNull/Null lines (summarized in Table 2). In early post-natal TRαAMI-ARO testes, the SC proliferation rate was similar to the rate observed in TRαAMI-SC of the same age, which explains why the increase in sperm reserve and in testis weight are of similar magnitude in adulthood in both lines. These results are not surprising since the KO of THRA (TRαNull/Null line) led to similar effects.

In adult TRαAMI-ARO males compared with their controls, we did not observe any change in plasma testosterone and LH levels, nor in steroidogenesis enzyme expression in testes. These converging observations support that local hypothyroidism induced before puberty by a dominant-negative TRα1 receptor does not influence LC steroidogenic activity, directly or indirectly, through putative SC-pathways. In the literature, on experiments in rats and humans, and despite abundant documentation of T3-dependent regulation of LC precursor cell differentiation [44,45], this point was controversial, depending on the model and the experimental approach used. In rats made hypothyroid with propil-thiouracil treatment during post-natal development or adulthood, it was observed that peripheral testosterone concentrations were unchanged [4,16,17,46,47]. In contrast, more recent studies on neonatal rats made hypothyroid using methimazole showed a different result, concluding that T3 increases testosterone production [18,19]. Yet another study, using thyroidectomy and thyroid hormone supplementation, showed a negative influence of T3 on testosterone production, along with decreased LH and FSH levels [48]. The degree of hypothyroidism could influence the impact on steroidogenesis and discrepancies may be due to the various molecules used to develop hypothyroidism, and/or by the timing of the pharmacological treatment. In humans as well, the impact of T3 deregulation varies from case to case (for review [49]), with decreased [50,51] or unchanged [52] blood testosterone levels in hypothyroid men. Our results suggest that the testosterone and LH endocrine disturbances observed in various hypothyroid animals (including humans) are probably more related to a disturbance at central level of the hypothalamo-pituitary axis than at gonadal level. Moreover, the discrepancies between pharmacological and functional models suggest that such perturbations may be the result of cumulative effects of T3 via TRα1 and possibly TRβ1, as we discussed in our previous work [8]. Indeed, whereas TRβ2 appears to be restricted to the nervous system, TRβ1 is expressed in various testis cells. Therefore, this receptor may directly transduce certain T3 functions in LC and/or SC, in addition to TRα1 (for review see [53,54]). It is possible that TRβ1 may palliate TRα1 in case of loss of receptor function. As discussed in our previous work, the systematic analysis of mice expressing the TRαAMI allele in various tissues suggests that most TRβ functions are preserved in this model [25,55], explaining the fact that the TRαNull/Null testis phenotype does not fully recapitulate post-natal hypothyroidism. In particular, in the present TRαAMI-ARO, TRβ1 could have significant function in Leydig cells, equilibrating testosterone levels.

A final point is the role of SC paracrine factors in the regulation of LC, with some of them putatively regulated by T3 during post-natal development, such as insulin-like growth factor-1 [54,56]. However, the TRαAMI-ARO phenotype suggests that such regulation through TRα1 is negligible, and this result is concordant with our previous study in which TRαAMI in SC alone did not affect testosterone levels.

Conclusion

Our work has confirmed the role of TRα1 in SC during post-natal life and pointed out that T3 does not, or only moderately, regulate steroidogenic activity through this receptor, whether in a direct LC-autonomous manner, or indirectly through SC paracrine regulation. This study also brings forward an additional genetic tool (i.e. the ARO-iCre line) to investigate LC function. Further characterizations of this model should define precisely the timing of Cre activity and its localization in the ovary.

Supporting Information

Cre recombinase activity detected in somatic cells of testes in ARO-iCre males at P3. After crossing with a ROSA26 Cre reporter mouse, β-galactosidase activity was detected in both ST (seminiferous tubules) and In (interstitium). Bar represents 50 μm.

(TIF)

Acknowledgments

The authors are very grateful to Drs Celine Viglietta, Carol Mendelson, Michel Cohen-Tannoudji, Fréderic Flamant, Michel Binoux and Philippe Soriano, as well as Helen Lamprell (HSB Traductions). We also thank Claude Cahier, Christophe Gauthier, Peggy Jarrier, Isabelle Gibert and Marie-Françoise Pinault.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by grant: TimeOfLife2, Agence Nationale pour la Recherche (http://www.agence-nationale-recherche.fr)—SF; Région Centre, France—BF (fellowship); Institut National Recherche Agronomique—PF, PM, SF; Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale—MH GL; Université Paris Diderot, Sorbonne Paris Cité—GL.

References

- 1. Jannini EA, Ulisse S, D'Armiento M (1995) Thyroid hormone and male gonadal function. Endocr Rev 16: 443–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Choksi NY, Jahnke GD, St Hilaire C, Shelby M (2003) Role of thyroid hormones in human and laboratory animal reproductive health. Birth Defects Res B Dev Reprod Toxicol 68: 479–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Joyce KL, Porcelli J, Cooke PS (1993) Neonatal goitrogen treatment increases adult testis size and sperm production in the mouse. J Androl 14: 448–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cooke PS, Meisami E (1991) Early hypothyroidism in rats causes increased adult testis and reproductive organ size but does not change testosterone levels. Endocrinology 129: 237–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. van Haaster LH, de Jong FH, Docter R, de Rooij DG (1993) High neonatal triiodothyronine levels reduce the period of Sertoli cell proliferation and accelerate tubular lumen formation in the rat testis, and increase serum inhibin levels. Endocrinology 133: 755–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Palmero S, Prati M, Bolla F, Fugassa E (1995) Tri-iodothyronine directly affects rat Sertoli cell proliferation and differentiation. J Endocrinol 145: 355–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Holsberger DR, Kiesewetter SE, Cooke PS (2005) Regulation of neonatal Sertoli cell development by thyroid hormone receptor alpha1. Biol Reprod 73: 396–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fumel B, Guerquin MJ, Livera G, Staub C, Magistrini M, Gauthier C, et al. (2012) Thyroid hormone limits postnatal Sertoli cell proliferation in vivo by activation of its alpha1 isoform receptor (TRalpha1) present in these cells and by regulation of Cdk4/JunD/c-myc mRNA levels in mice. Biol Reprod 87: 16, 11–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chatonnet F, Livera G, Fumel B, Fouchécourt S, Flamant F (2014) Direct and indirect consequences on gene expression of a thyroid hormone receptor alpha 1 mutation restricted to sertoli cells. Mol Reprod Dev. 10.1002/mrd.22437 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10. Mendis-Handagama SM, Ariyaratne HB (2001) Differentiation of the adult Leydig cell population in the postnatal testis. Biol Reprod 65: 660–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wu X, Wan S, Lee MM (2007) Key factors in the regulation of fetal and postnatal Leydig cell development. J Cell Physiol 213: 429–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ariyaratne HB, Chamindrani Mendis-Handagama S (2000) Changes in the testis interstitium of Sprague Dawley rats from birth to sexual maturity. Biol Reprod 62: 680–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wu X, Arumugam R, Zhang N, Lee MM (2010) Androgen profiles during pubertal Leydig cell development in mice. Reproduction 140: 113–121. 10.1530/REP-09-0349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mendis-Handagama SM, Ariyaratne HB (2004) Effects of thyroid hormones on Leydig cells in the postnatal testis. Histol Histopathol 19: 985–997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Manna PR, Tena-Sempere M, Huhtaniemi IT (1999) Molecular mechanisms of thyroid hormone-stimulated steroidogenesis in mouse leydig tumor cells. Involvement of the steroidogenic acute regulatory (StAR) protein. J Biol Chem 274: 5909–5918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kirby JD, Jetton AE, Cooke PS, Hess RA, Bunick D, Ackland JF, et al. (1992) Developmental hormonal profiles accompanying the neonatal hypothyroidism-induced increase in adult testicular size and sperm production in the rat. Endocrinology 131: 559–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cooke PS (1991) Thyroid hormones and testis development: a model system for increasing testis growth and sperm production. Ann N Y Acad Sci 637: 122–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Maran RR, Arunakaran J, Jeyaraj DA, Ravichandran K, Ravisankar B, Aruldhas MM. (2000) Transient neonatal hypothyroidism alters plasma and testicular sex steroid concentration in puberal rats. Endocr Res 26: 411–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Maran RR, Ravichandran K, Arunakaran J, Aruldhas MM (2001) Impact of neonatal hypothyroidism on Leydig cell number, plasma, and testicular interstitial fluid sex steroids concentration. Endocr Res 27: 119–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tagami T, Nakamura H, Sasaki S, Mori T, Yoshioka H, Yoshida H, et al. (1990) Immunohistochemical localization of nuclear 3,5,3'-triiodothyronine receptor proteins in rat tissues studied with antiserum against C-ERB A/T3 receptor. Endocrinology 127: 1727–1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shimshek DR, Kim J, Hubner MR, Spergel DJ, Buchholz F, Casanova E, et al. (2002) Codon-improved Cre recombinase (iCre) expression in the mouse. Genesis 32: 19–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vandormael-Pournin S, Guigon CJ, Ishaq M, Coudouel N, Ave P, Huerre M, et al. (2015) Oocyte-specific inactivation of Omcg1 leads to DNA damage and c-Abl/TAp63-dependent oocyte death associated with dramatic remodeling of ovarian somatic cells. Cell Death Differ 22: 108–117. 10.1038/cdd.2014.122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hinshelwood MM, Smith ME, Murry BA, Mendelson CR (2000) A 278 bp region just upstream of the human CYP19 (aromatase) gene mediates ovary-specific expression in transgenic mice. Endocrinology 141: 2050–2053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Leneuve P, Zaoui R, Monget P, Le Bouc Y, Holzenberger M (2001) Genotyping of Cre-lox mice and detection of tissue-specific recombination by multiplex PCR. Biotechniques 31: 1156–1160, 1162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Quignodon L, Vincent S, Winter H, Samarut J, Flamant F (2007) A point mutation in the activation function 2 domain of thyroid hormone receptor alpha1 expressed after CRE-mediated recombination partially recapitulates hypothyroidism. Mol Endocrinol 21: 2350–2360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Livera G, Delbes G, Pairault C, Rouiller-Fabre V, Habert R (2006) Organotypic culture, a powerful model for studying rat and mouse fetal testis development. Cell Tissue Res 324: 507–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gauthier K, Plateroti M, Harvey CB, Williams GR, Weiss RE, Refetoff S, et al. (2001) Genetic analysis reveals different functions for the products of the thyroid hormone receptor alpha locus. Mol Cell Biol 21: 4748–4760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Holzenberger M, Leneuve P, Hamard G, Ducos B, Perin L, Binoux M, et al. (2000) A targeted partial invalidation of the insulin-like growth factor I receptor gene in mice causes a postnatal growth deficit. Endocrinology 141: 2557–2566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Holzenberger M, Lenzner C, Leneuve P, Zaoui R, Hamard G, Vaulont S, et al. (2000) Cre-mediated germline mosaicism: a method allowing rapid generation of several alleles of a target gene. Nucleic Acids Res 28: E92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cadoret A, Desbois-Mouthon C, Wendum D, Leneuve P, Perret C, Tronche F, et al. (2005) c-myc-induced hepatocarcinogenesis in the absence of IGF-I receptor. Int J Cancer 114: 668–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Soriano P (1999) Generalized lacZ expression with the ROSA26 Cre reporter strain. Nat Genet 21: 70–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Picou F, Fauquier T, Chatonnet F, Richard S, Flamant F (2014) Deciphering direct and indirect influence of thyroid hormone with mouse genetics. Mol Endocrinol 28: 429–441. 10.1210/me.2013-1414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. O'Hara L, York JP, Zhang P, Smith LB (2014) Targeting of GFP-Cre to the mouse Cyp11a1 locus both drives cre recombinase expression in steroidogenic cells and permits generation of Cyp11a1 knock out mice. PLoS One 9: e84541 10.1371/journal.pone.0084541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bridges PJ, Koo Y, Kang DW, Hudgins-Spivey S, Lan ZJ, Xu X, et al. (2008) Generation of Cyp17iCre transgenic mice and their application to conditionally delete estrogen receptor alpha (Esr1) from the ovary and testis. Genesis 46: 499–505. 10.1002/dvg.20428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jamin SP, Arango NA, Mishina Y, Hanks MC, Behringer RR (2002) Requirement of Bmpr1a for Mullerian duct regression during male sexual development. Nat Genet 32: 408–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jeyasuria P, Ikeda Y, Jamin SP, Zhao L, De Rooij DG, Themmen AP, et al. (2004) Cell-specific knockout of steroidogenic factor 1 reveals its essential roles in gonadal function. Mol Endocrinol 18: 1610–1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Xu Q, Lin HY, Yeh SD, Yu IC, Wang RS, Chen YT, et al. (2007) Infertility with defective spermatogenesis and steroidogenesis in male mice lacking androgen receptor in Leydig cells. Endocrine 32: 96–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wu X, Zhang N, Lee MM (2012) Mullerian inhibiting substance recruits ALK3 to regulate Leydig cell differentiation. Endocrinology 153: 4929–4937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tanwar PS, Kaneko-Tarui T, Zhang L, Rani P, Taketo MM, Teixeira J. (2010) Constitutive WNT/beta-catenin signaling in murine Sertoli cells disrupts their differentiation and ability to support spermatogenesis. Biol Reprod 82: 422–432. 10.1095/biolreprod.109.079335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Simpson ER, Clyne C, Rubin G, Boon WC, Robertson K, Britt K, et al. (2002) Aromatase—a brief overview. Annu Rev Physiol 64: 93–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tsai-Morris CH, Aquilano DR, Dufau ML (1985) Cellular localization of rat testicular aromatase activity during development. Endocrinology 116: 38–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Papadopoulos V, Carreau S, Szerman-Joly E, Drosdowsky MA, Dehennin L, Scholler R. (1986) Rat testis 17 beta-estradiol: identification by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry and age related cellular distribution. J Steroid Biochem 24: 1211–1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Levallet J, Bilinska B, Mittre H, Genissel C, Fresnel J, Carreau S. (1998) Expression and immunolocalization of functional cytochrome P450 aromatase in mature rat testicular cells. Biol Reprod 58: 919–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ariyaratne HB, Mills N, Mason JI, Mendis-Handagama SM (2000) Effects of thyroid hormone on Leydig cell regeneration in the adult rat following ethane dimethane sulphonate treatment. Biol Reprod 63: 1115–1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wagner MS, Wajner SM, Maia AL (2008) The role of thyroid hormone in testicular development and function. J Endocrinol 199: 351–365. 10.1677/JOE-08-0218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hardy MP, Kirby JD, Hess RA, Cooke PS (1993) Leydig cells increase their numbers but decline in steroidogenic function in the adult rat after neonatal hypothyroidism. Endocrinology 132: 2417–2420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Valenti S, Guido R, Fazzuoli L, Barreca A, Giusti M, Giordano G. (1997) Decreased steroidogenesis and cAMP production in vitro by leydig cells isolated from rats made hypothyroid during adulthood. Int J Androl 20: 279–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Antony FF, Aruldhas MM, Udhayakumar RC, Maran RR, Govindarajulu P (1995) Inhibition of Leydig cell activity in vivo and in vitro in hypothyroid rats. J Endocrinol 144: 293–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kumar A, Shekhar S, Dhole B (2014) Thyroid and male reproduction. Indian J Endocrinol Metab 18: 23–31. 10.4103/2230-8210.126523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Donnelly P, White C (2000) Testicular dysfunction in men with primary hypothyroidism; reversal of hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism with replacement thyroxine. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 52: 197–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kumar A, Mohanty BP, Rani L (2007) Secretion of testicular steroids and gonadotrophins in hypothyroidism. Andrologia 39: 253–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Velazquez EM, Bellabarba Arata G (1997) Effects of thyroid status on pituitary gonadotropin and testicular reserve in men. Arch Androl 38: 85–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Holsberger DR, Cooke PS (2005) Understanding the role of thyroid hormone in Sertoli cell development: a mechanistic hypothesis. Cell Tissue Res 322: 133–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Maran RR (2003) Thyroid hormones: their role in testicular steroidogenesis. Arch Androl 49: 375–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Fauquier T, Romero E, Picou F, Chatonnet F, Nguyen XN, Quignodon L, et al. (2011) Severe impairment of cerebellum development in mice expressing a dominant-negative mutation inactivating thyroid hormone receptor alpha1 isoform. Dev Biol 356: 350–358. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.05.657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Palmero S, Prati M, Barreca A, Minuto F, Giordano G, Fugassa E. (1990) Thyroid hormone stimulates the production of insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) by immature rat Sertoli cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol 68: 61–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Cre recombinase activity detected in somatic cells of testes in ARO-iCre males at P3. After crossing with a ROSA26 Cre reporter mouse, β-galactosidase activity was detected in both ST (seminiferous tubules) and In (interstitium). Bar represents 50 μm.

(TIF)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.