Abstract

Objectives

The aim of the present study was to assess the appropriate administration dose of non-steroidal anti-inflammation drugs to prevent pancreatitis after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). Importantly, the 100 mg dose of diclofenac recommended in Western countries has not been permitted in Japan.

Design

A retrospective study.

Settings

A single centre in Japan.

Participants

This study enrolled patients who underwent ERCP at the Department of Gastroenterology, Osaka Saiseikai Senri Hospital, from April 2011 through June 2013, and who received either a 25 or a 50 mg dose of rectal diclofenac after ERCP.

Primary outcome measure

The occurrence of post-ERCP pancreatitis (PEP). A multivariate regression model was used to assess the effect of the 50 mg dose (the 50 mg group) of rectal diclofenac and to compare it to the occurrence of PEP referring to the 25 mg group.

Results

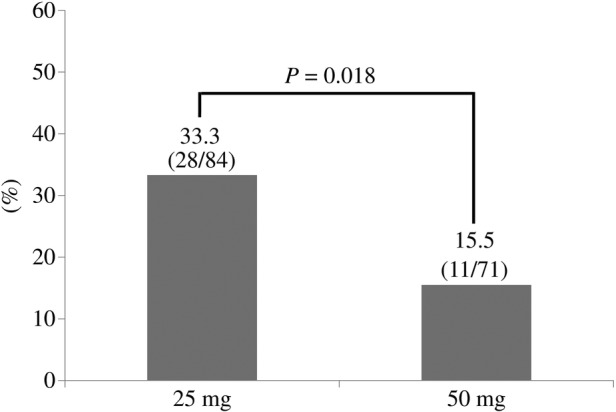

A total of 155 eligible patients received either 25 mg (84 patients) or 50 mg (71 patients) doses of rectal diclofenac after ERCP to prevent PEP. The proportion of PEP was significantly lower in the 50 mg group than in the 25 mg group (15.5% (11/71) vs 33.3% (28/84), p=0.018). In a multivariate analysis, the occurrence of PEP was significantly lower in the 50 mg group than in the 25 mg group even after adjusting potential confounding factors (adjusted OR=0.27, 95% CI 0.11 to 0.70).

Conclusions

From this observation, the occurrence of PEP was significantly lower among ERCP patients with the 50 mg dose of rectal diclofenac than among those with the 25 mg dose.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study showed that the occurrence of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) pancreatitis was significantly lower among ERCP patients with the 50 mg dose of rectal diclofenac than among those with the 25 mg dose.

This study was a retrospective study, so there was the potential of selection bias.

This study did not assess the effect of non-steroidal anti-inflammation drugs other than diclofenac for prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis.

Introduction

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is widely conducted as a therapeutic and diagnostic procedure for hepatobiliary-pancreatic diseases.1–6 However, the prevalence of ERCP adverse events has become high, and post-ERCP pancreatitis (PEP) has occurred in 1–30% of patients who have undergone ERCP. PEP can become severe and lead to death among these patients.1–6 Therefore, many studies on risk factors, preventive manoeuvres and drug administrations for PEP have been conducted worldwide.1–11

Recently, numerous reports have been published on the effectiveness of rectal administration of non-steroidal anti-inflammation drugs (NSAIDs) to prevent PEP.11–15 Several randomised controlled trials revealed that the 100 mg dose of rectal diclofenac/indomethacin after ERCP significantly reduced PEP occurrence compared with non-administration,11–15 and the rectal administration of NSAIDs after ERCP has been widely accepted worldwide, including in Japan.16 A meta-analysis demonstrated that NSAID administration for PEP prevention was effective compared with non-administration, and its effectiveness is currently being established.11 However, little is known about the appropriate NSAID dose to prevent PEP.17 In addition, the 100 mg dose of diclofenac recommended in Western countries has not been legally permitted in Japan.16–18

The aim of this study was to compare a 25 mg dose of diclofenac to the 50 mg dose for the prevention of PEP among ERCP patients. Our hypothesis is that the occurrence of PEP would be lower in the 50 mg group than in the 25 mg group.

Methods

Study design

This observation was a single-centre, retrospective study. We enrolled patients who underwent ERCP at the Department of Gastroenterological Medicine, Osaka Saiseikai Senri Hospital, from April 2011 through June 2013, who then received either a 25 or 50 mg dose of rectal diclofenac.

Settings and data collection

Osaka Saiseikai Senri Hospital, located in the northern area of Suita City, Osaka, Japan, has 343 beds, seven attending doctors and four residents in its Department of Gastroenterology (50 beds). Approximately 250 patients with gastroenterological diseases annually undergo ERCP in this hospital. The side-viewing endoscopes used for ERCP were either TJF-260V or JF-260V (Olympus Corporation), and the appliance for cannulation was Tandem XL TAPERED TIP and Jagwire (0.035 inch; Boston Scientific Corporation).

Among patients undergoing ERCP, either a 25 or 50 mg dose of rectal diclofenac was administered within 10 min immediately after ERCP for those more likely to develop PEP, based on the judgment of a main ERCP operator, and the dose (25 or 50 mg) of rectal diclofenac was decided comprehensively based on patient age, body mass index (BMI) and serum creatinine. In our hospital, during the study period, both sulbactam sodium/cefoperazone sodium 3.0 g/day and gabexate mesilate 0.3 g/day were administered to all patients for at least 2 days after ERCP, and blood tests such as serum pancreatic-type amylase and creatinine were also conducted the day after ERCP. In addition, when a doctor in charge diagnosed or suspected PEP in a patient who underwent ERCP, contrast-enhanced CT scanning and blood tests were conducted.17

Information on characteristics and outcomes of ERCP patients was retrospectively extracted from medical records, and the following data were included: gender, age, height, body weight, BMI, serum creatinine concentration; history of hepatobiliary, pancreatic, or gastrointestinal cancers; history of pancreatitis, first conducted ERCP, type of operator (resident or not), duration of ERCP examination, difficult cannulation and ERCP individual procedures (wire insertion into pancreatic duct, cytology of pancreas duct, pancreatography, cytology of bile duct), endoscopic sphincterotomy, endoscopic papillary balloon dilation, choledocholithotomy and stenting to pancreatic duct. Duration of ERCP examination was defined as the time interval from the side-viewing endoscope insertion to its removal,19 and the difficulty of cannulation was determined by a main operator or an attending doctor. The procedure for pancreatic duct was defined as any one of wire insertions into the pancreatic duct, its cytology or pancreatography.

Study end point

The primary outcome measure was the occurrence of PEP, defined as the development of both new or worsened abdominal pain and hyperamylasaemia based on the Cotton criteria.1 6 The secondary outcome measure was the occurrence of post-ERCP hyperamylasaemia, defined as a rise in the serum pancreatic-type amylase concentration to more than three times the upper limit of the normal laboratory value (>123 IU/mL) within 24 h after ERCP.1 6 In addition, death, severe acute pancreatitis, acute renal failure and gastrointestinal bleeding were defined as severe adverse events after rectal diclofenac administration.1 6 Severe acute pancreatitis was defined based on the Japanese guideline.17 Acute renal failure was defined as an increase of the serum creatinine ≥3 times over that before ERCP.20

Statistical analyses

Patient characteristics and outcomes between the two groups with 25 and 50 mg doses of rectal diclofenac were compared after ERCP. Continuous data were presented as the median (interquartile), differences were analysed by Mann-Whitney test, categorical data were expressed in percentages (n/N) and differences were analysed by χ2 test or Fischer's exact test. The multivariate logistic regression was used to assess the effect of 50 mg of rectal diclofenac (the 50 mg group) and to compare it to the occurrence of PEP and hyperamylasaemia referring to the 25 mg group. The ORs and their CIs were calculated. Potential confounding factors based on biological plausibility and previous studies were included in the multivariate analysis.5 6 21 These variables were gender (male, female), age (<65, ≥65 years old), BMI (<22, ≥22 kg/m2), type of operator (resident or not), difficult cannulation (yes, no), and procedure in pancreatic duct (yes, no). All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS V.22.0J (IBM Corp, Armonk, New York). All tests were two tailed, and p values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

During the study period, a total of 166 patients received either a 25 or 50 mg dose of rectal diclofenac after ERCP to prevent PEP and hyperamylasaemia. Excluding three patients who had pancreatitis and eight who were given NSAIDs before ERCP, 155 patients (84 in the 25 mg group and 71 in the 50 mg group) were eligible for our analysis.

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics and ERCP-related procedures of eligible patients with the 25 vs 50 mg of rectal diclofenac after ERCP. The proportion of males was significantly higher in the 50 mg group than in the 25 mg group (64.8% vs 46.4%, p=0.022), whereas median age was significantly lower in the 50 mg group than in the 25 mg group (67.0% vs 73.5%, p<0.001). The 50 mg group had significantly lower BMI than the 25 mg group (21.9 vs 23.2, p=0.019). The proportion of ERCP conducted by a resident as main operator was significantly lower in the 50 mg group than in the 25 mg group (54.9% vs 71.4%, p=0.022). Other factors did not differ between the groups.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients administered a 25 versus 50 mg dose of rectal diclofenac after ERCP

| Rectal diclofenac |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total |

25 mg |

50 mg |

p Value | ||||

| Men, % (n/N) | 54.8 | (85/155) | 46.4 | (39/84) | 64.8 | (46/71) | 0.022 |

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 71.0 (63.0–76.0) | 73.5 (68.0–80.0) | 67.0 (57.0–74.0) | <0.001 | |||

| Elderly aged ≥65, % (n/N) | 71.0 | (110/155) | 82.1 | (69/84) | 57.7 | (41/71) | 0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2), median (IQR) | 22.5 (19.5–25.3) | 23.2 (21.2–25.6) | 21.9 (19.2–24.4) | 0.019 | |||

| BMI <22 | 59.6 | (90/151) | 50.0 | (40/80) | 70.4 | (50/71) | 0.011 |

| Cancer, % (n/N) | 32.9 | (50/155) | 34.1 | (28/82) | 31.4 | (22/70) | 0.722 |

| History of pancreatitis, % (n/N) | 16.2 | (25/154) | 13.3 | (11/83) | 19.7 | (14/71) | 0.278 |

| First conducted ERCP, % (n/N) | 34.8 | (54/155) | 33.3 | (28/84) | 36.6 | (26/71) | 0.669 |

| Resident as a main operator, % (n/N) | 63.9 | (99/155) | 71.4 | (60/84) | 54.9 | (39/71) | 0.033 |

| Serum creatinine before ERCP (mg/dL) | 0.80 (0.70–0.90) | 0.80 (0.70–0.90) | 0.80 (0.70–1.00) | 0.642 | |||

| Duration of examination, median (IQR) | 36.5 (26.0–51.3) | 37.0 (28.0–50.0) | 35.0 (23.0–53.0) | 0.568 | |||

| Duration of examination >30 min, % (n/N) | 63.6 | (98/154) | 66.3 | (55/83) | 60.6 | (43/71) | 0.463 |

| Difficult cannulation, % (n/N) | 28.4 | (44/155) | 27.4 | (23/84) | 29.6 | (21/71) | 0.763 |

| Procedures for pancreatic duct, % (n/N) | 68.4 | (106/155) | 69.0 | (58/84) | 67.6 | (48/71) | 0.847 |

| Pancreatic duct wire, % (n/N) | 65.2 | (101/155) | 65.5 | (55/84) | 64.8 | (46/71) | 0.929 |

| Cytology of pancreas duct, % (n/N) | 19.4 | (30/155) | 17.9 | (15/84) | 21.1 | (15/71) | 0.608 |

| Pancreatography, % (n/N) | 31.6 | (49/155) | 34.5 | (29/84) | 28.2 | (20/71) | 0.397 |

| Cytology of bile duct, % (n/N) | 18.7 | (29/155) | 20.2 | (17/84) | 16.9 | (12/71) | 0.596 |

| EST, % (n/N) | 26.5 | (41/155) | 23.8 | (20/84) | 29.6 | (21/71) | 0.417 |

| EPBD, % (n/N) | 5.8 | (9/155) | 6.0 | (5/84) | 5.6 | (4/71) | 0.605 |

| Choledocholithotomy, % (n/N) | 38.1 | (59/155) | 41.7 | (35/84) | 33.8 | (24/71) | 0.315 |

| Stenting to pancreatic duct, % (n/N) | 2.6 | (4/155) | 2.4 | (2/84) | 2.8 | (2/71) | 0.624 |

BMI, body mass index; EPBD, endoscopic papillary balloon dilation; ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; EST, endoscopic sphincterotomy.

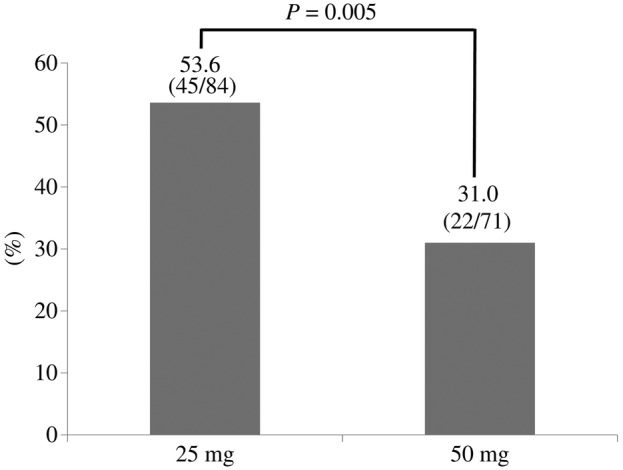

Among eligible patients receiving rectal diclofenac after ERCP, 25.2% (39/155) had PEP and 43.2% (67/155) had post-ERCP hyperamylasaemia. The proportion of PEP was significantly lower in the 50 mg group than in the 25 mg group (15.5% (11/71) vs 33.3% (28/84), p=0.018, figure 1), and the proportion of post-ERCP hyperamylasaemia was also significantly lower in the 50 mg group than in the 25 mg group (31.0% (22/71) vs 53.6% (45/84), p=0.005, figure 2). The concentration of serum pancreatic-type amylase after ERCP was significantly lower in the 50 mg group than in the 25 mg group (54.0 (30.8–189.3) vs 148.0 (40.0–502.0) IU/mL, p=0.006). As for severe events after ERCP, there were no deaths, acute renal failures or gastrointestinal bleeding in either group, but one patient in the 25 mg group had severe acute pancreatitis.

Figure 1.

Proportion of PEP occurrence among ERCP patients with a 25 vs 50 mg dose of rectal diclofenac administration. ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; PEP, post-ERCP pancreatitis.

Figure 2.

Proportion of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) hyperamylasaemia occurrence among ERCP patients with a 25 mg vs 50 mg dose of rectal diclofenac administration.

In a multivariate analysis, the occurrence of PEP was significantly lower in the 50 mg group than in the 25 mg group even after adjusting for potential confounding factors such as sex, age, BMI, the type of operator, difficult cannulation and procedures for pancreatic duct (adjusted OR=0.27, 95% CI 0.11 to 0.70, table 2). The occurrence of post-ERCP hyperamylasaemia was also significantly lower in the 50 mg group than in the 25 mg group (adjusted OR=0.35, 95% CI 0.15 to 0.84, table 3).

Table 2.

Association between 25 and 50 mg dose of rectal diclofenac and post-ERCP pancreatitis

| OR | (95% CI) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Post-ERCP pancreatitis | |||

| Univariate | 0.37 | (0.17 to 0.80) | 0.018 |

| Multivariate | |||

| Model 1 | 0.31 | (0.13 to 0.75) | 0.009 |

| Model 2 | 0.27 | (0.11 to 0.70) | 0.007 |

ORs were calculated for the 50 mg group referring to the 25 mg group.

Model 1: Adjusted for sex, age and BMI.

Model 2: Adjusted for sex, age, BMI, type of operator, difficult cannulation and procedures for pancreatic duct.

BMI, body mass index; ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

Table 3.

Association between 25 and 50 mg dose of rectal diclofenac and post-ERCP hyperamylasaemia

| OR | (95% CI) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Post-ERCP hyperamylasaemia | |||

| Univariate | 0.39 | (0.20 to 0.75) | 0.005 |

| Multivariate | |||

| Model 1 | 0.44 | (0.21 to 0.92) | 0.028 |

| Model 2 | 0.35 | (0.15 to 0.84) | 0.018 |

ORs were calculated for the 50 mg group referring to the 25 mg group.

Model 1: Adjusted for sex, age and BMI.

Model 2: Adjusted for sex, age, BMI, type of operator, difficult cannulation and procedures for pancreatic duct.

BMI, body mass index; ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

Discussion

From a single-centre observational study, we demonstrated that the occurrence of PEP and post-ERCP hyperamylasaemia was significantly lower among ERCP patients on the 50 mg dose of rectal diclofenac than among those on the 25 mg dose, which suggested that the effectiveness of diclofenac for PEP was dose dependent. Importantly, the dose of diclofenac administration for patients was limited to a single maximum of 50 mg in Japan,16 17 but the preceding studies could not sufficiently compare the effects of 25 and 50 mg doses of rectal diclofenac for the prevention of PEP among ERCP patients. Therefore, our study provides helpful new clues for actual prevention of PEP at gastroenterological clinical settings in Japan.

The present study showed that the prevention of PEP among ERCP patients by diclofenac was dose-dependently effective. Previous randomised trials and meta-analyses indicated that 100 mg (not 50 mg) rectal NSAID administration was more effective for PEP prevention than non-administration.11–13 In a randomised control trial in Japan, the authors showed that low doses (either 25 or 50 mg) of rectal diclofenac were more effective in preventing PEP compared with the placebo group.16 From a subanalysis of the trial, the occurrence of PEP among patients administered 50 mg of rectal diclofenac tended to be lower than among those given 25 mg, although it was statistically insignificant (0% (0/29) vs 9% (2/22), p=0.101). This result was almost consistent with ours. No randomised trials directly compared a 25 mg of rectal diclofenac to a 50 mg dose for the prevention of PEP, but conducting randomised trials to determine the appropriate dose of NSAID administration for the prevention of PEP is important in Japan.

Why does the administration of NSAIDs for ERCP patients prevent PEP? Although much of its preventive mechanism is unclear, it is suggested that the activation of trypsin/trypsinogen in acinar cells of the pancreas causes acute pancreatic inflammation by factors such as mechanical stimulus of the pancreatic duct, intestinal fluid flow into the pancreatic duct, increase in pancreatic duct internal pressure or pancreatic tissue pressure by pancreatography and pancreatic fluid congestion by Vater papilla oedema.11 22 23 In particular, phospholipase A2 synthesised in the pancreas regulates inflammation mediators such as prostaglandins, leukotrienes and thromboxanes by arachidonic acid cascade24 and NSAIDs, the cyclo-oxigenase inhibitors, prevent PEP by inhibiting its cascade.12 22–25 The efficacy of NSAIDs including diclofenac is reportedly dose dependent.26–28 This study, showing the dose-dependent effect of diclofenac for PEP prevention, suggested that sufficient doses of NSAIDs are needed to inhibit arachidonic acid cascades for PEP prevention.

Gastrointestinal bleeding and acute renal failure were among the severe adverse events after NSAID administration.15 Preceding studies underscored the very low occurrence of severe adverse events such as gastrointestinal bleeding and acute renal failure after NSAID administration for PEP prevention.13 15 16 Even in the present study, there was no gastrointestinal bleeding or acute renal failure regardless of the dose of diclofenac, and diclofenac administration would thus be acceptable for PEP prevention. However, gastroenterologists in Japan tend to hesitate to use the 50 mg dose of rectal diclofenac for PEP prevention16 17 29 because of concerns such as gastrointestinal adverse events, acute renal failure, and decrease in blood pressure after NSAID administration.27–29 However, administering the 50 mg dose of rectal diclofenac for patients without problems such as renal dysfunction before ERCP should be recommended.

NSAID administration for PEP prevention is given a grade A recommendation by the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guideline, grade C1 by the Japanese guideline, and a moderate rating by the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) guideline, respectively.17 30 31 Recently, the number of patients with acute pancreatitis has been excessively increasing,17 32 and its medical cost has also been climbing. Considering the limited medical resources in Japan, the 50 mg dose of rectal diclofenac for PEP prevention will surely become an established method to be administered without hesitation, because NSAIDs including diclofenac are inexpensive and have few adverse effects, and their administration method is also simple and easy. However, large-scale prospective multicentre observational or randomised trials are warranted to confirm our results.

There are several limitations to this study. First, it was conducted retrospectively, and there was the potential of selection bias. For example, the proportion of PEP occurrence in this study was higher than that in previous studies,13 16 because either a 25 or 50 mg dose of diclofenac was selectively administered to ERCP patients who were more likely to develop PEP based on the judgment of a main ERCP operator. Second, our study did not assess the effect of NSAIDs other than diclofenac for PEP prevention. Third, unmeasured confounding factors may have influenced the association between the occurrence of PEP and rectal diclofenac administration among ERCP patients.

Conclusion

From a single-centre observation in Osaka, this study demonstrated that the occurrence of PEP and post-ERCP hyperamylasaemia was significantly lower among ERCP patients with the 50 mg dose of rectal diclofenac than among those with the 25 mg dose. Further large-scale prospective multicentre observational or randomised controlled trials are warranted to confirm our results.

Acknowledgments

The authors are deeply indebted to the staff and physicians of Osaka Saiseikai Senri Hospital.

Footnotes

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the institutional review board of Osaka Saiseikai Senri Hospital.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Cotton PB, Eisen GM, Aabakken L et al. A lexicon for endoscopic adverse events: report of an ASGE workshop. Gastrointest Endosc 2010;71:446–54. 10.1016/j.gie.2009.10.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freeman ML, Nelson DB, Sherman S et al. Complications of endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy. N Engl J Med 1996;335:909–18. 10.1056/NEJM199609263351301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rabenstein T, Hahn EG. Post-ERCP pancreatitis: new momentum. Endoscopy 2002;34:325–9. 10.1055/s-2002-23651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vandervoort J, Soetikno RM, Tham TC et al. Risk factors for complications after performance of ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc 2002;56:652–6. 10.1016/S0016-5107(02)70112-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freeman ML, DiSario JA, Nelson DB et al. Risk factors for post-ERCP pancreatitis: a prospective, multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc 2001;54:425–34. 10.1067/mge.2001.117550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kubiliun NM, Adams MA, Akshintala VS et al. Evaluation of Pharmacologic Prevention of Pancreatitis Following Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography: a Systematic Review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015. Published Online 8 Jan 2015. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2014.11.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fazel A, Quadri A, Catalano MF et al. Does a pancreatic duct stent prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis? A prospective randomized study. Gastrointest Endosc 2003;57:291–4. 10.1067/mge.2003.124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andriulli A, Leandro G, Federici T et al. Prophylactic administration of somatostatin or gabexate does not prevent pancreatitis after ERCP: an updated meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc 2007;65:624–32. 10.1016/j.gie.2006.10.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tarnasky PR, Palesch YY, Cunningham JT et al. Pancreatic stenting prevents pancreatitis after biliary sphincterotomy in patients with sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. Gastroenterology 1998;115:1518–24. 10.1016/S0016-5085(98)70031-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh P, Das A, Isenberg G et al. Does prophylactic pancreatic stent placement reduce the risk of post-ERCP acute pancreatitis? A meta-analysis of controlled trials. Gastrointest Endosc 2004;60:544–50. 10.1016/S0016-5107(04)02013-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akbar A, Abu Dayyeh BK, Baron TH et al. Rectal nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are superior to pancreatic duct stents in preventing pancreatitis after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: a network meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013;11:778–83. 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.12.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murray B, Carter R, Imrie C et al. Diclofenac reduces the incidence of acute pancreatitis after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Gastroenterology 2003;124:1786–91. 10.1016/S0016-5085(03)00384-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elmunzer BJ, Waljee AK, Elta GH et al. A meta-analysis of rectal NSAIDs in the prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis. Gut 2008;57:1262–7. 10.1136/gut.2007.140756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zheng MH, Xia HH, Chen YP. Rectal administration of NSAIDs in the prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis: a complementary meta-analysis. Gut 2008;57:1632–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elmunzer BJ, Scheiman JM, Lehman GA et al. A randomized trial of rectal indomethacin to prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis. N Engl J Med 2012;366:1414–22. 10.1056/NEJMoa1111103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Otsuka T, Kawazoe S, Nakashita S et al. Low-dose cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis: a randomized controlled trial. J Gastroenterol 2012;47:912–17. 10.1007/s00535-012-0554-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arata S, Takada T, Hirata K et al. Post-ERCP pancreatitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2010;17:70–8. 10.1007/s00534-009-0220-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Summary of product characteristics of Voltaren® at Novartis company homepage. http://product.novartis.co.jp/vol/pi/VS1402.pdf (accessed 13 Jun 2014) (In Japanese).

- 19.Mehta PP, Sanaka MR, Parsi MA et al. Association of procedure length on outcomes and adverse events of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Gastroenterol Rep 2014;2:140–4. 10.1093/gastro/gou009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Acute Kidney Injury Work Group. KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for acute kidney injury. Kidney Int Suppl 2012;2:19–36. 10.1038/kisup.2011.32 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Day LW, Lin L, Somsouk M. Adverse events in older patients undergoing ERCP: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Endoscopy Int Open 2014;02:E28–36. 10.1055/s-0034-1365281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pezzilli R, Romboli E, Campana D et al. Mechanisms involved in the onset of post-ERCP pancreatitis. JOP 2002;3:162–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsujino T, Kawabe T, Omata M. Antiproteases in preventing post-ERCP acute pancreatitis. JOP 2007;8:509–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mäkelä A, Kuusi T, Schröder T. Inhibition of serum phospholipase-A2 in acute pancreatitis by pharmacological agents in vitro. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 1997;57:401–7. 10.3109/00365519709084587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gross V, Leser HG, Heinisch A et al. Inflammatory mediators and cytokines—new aspects of the pathophysiology and assessment of severity of acute pancreatitis? Hepatogastroenterology 1993;40:522–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Giagoudakis G, Markantonis SL. Relationships between the concentrations of prostaglandins and the nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs indomethacin, diclofenac, and ibuprofen. Pharmacotherapy 2005;25:18–25. 10.1592/phco.25.1.18.55618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Richy F, Bruyere O, Ethgen O et al. Time dependent risk of gastrointestinal complications induced by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use: a consensus statement using a meta-analytic approach. Ann Rheum Dis 2004;63: 759–66. 10.1136/ard.2003.015925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rostom A, Goldkind L, Laine L. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and hepatic toxicity: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials in arthritis patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2005;3:489–98. 10.1016/S1542-3565(04)00777-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Warning and precautions of Voltaren® at Novartis company homepage. http://www.voltaren.jp/m_kinki/kinki_a11.html (accessed 13 Jun 2014) (In Japanese).

- 30.Dumonceau JM, Andriulli A, Deviere J et al. European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline: prophylaxis of post-ERCP pancreatitis. Endoscopy 2010;42:503–15. 10.1055/s-0029-1244208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tenner S, Baillie J, DeWitt J et al. American College of Gastroenterology guideline: management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108:1400–15. 10.1038/ajg.2013.218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute on “Management of Acute Pancreatits” Clinical Practice and Economics Committee; AGA Institute Governing Board. AGA Institute Medical Position Statement on Acute Pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 2007;132:2019–21. 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]