Abstract

Introduction and objectives

Drug-related problems (DRPs) constitute a frequent safety issue among hospitalised patients leading to patient harm and increased healthcare costs. Because many DRPs are preventable, the specific risk factors that facilitate their occurrence are of considerable interest. The objective of our study was to assess risk factors for the occurrence of DRPs with the intention to identify patients at risk for DRPs to guide and target preventive measures where they are needed most in patients.

Design

Triangulation process using a mixed methods approach.

Methods

We conducted an expert panel, using the nominal group technique (NGT) and a qualitative analysis, to gather risk factors for DRPs. The expert panel consisted of two consultant hospital physicians (internal medicine and geriatrics), one emergency physician, one independent general practitioner, one clinical pharmacologist, one clinical pharmacist, one registered nurse, one home care nurse and two independent community pharmacists. The literature was searched for additional risk factors. Gathered factors from the literature search and the NGT were assembled and validated in a two-round Delphi questionnaire.

Results

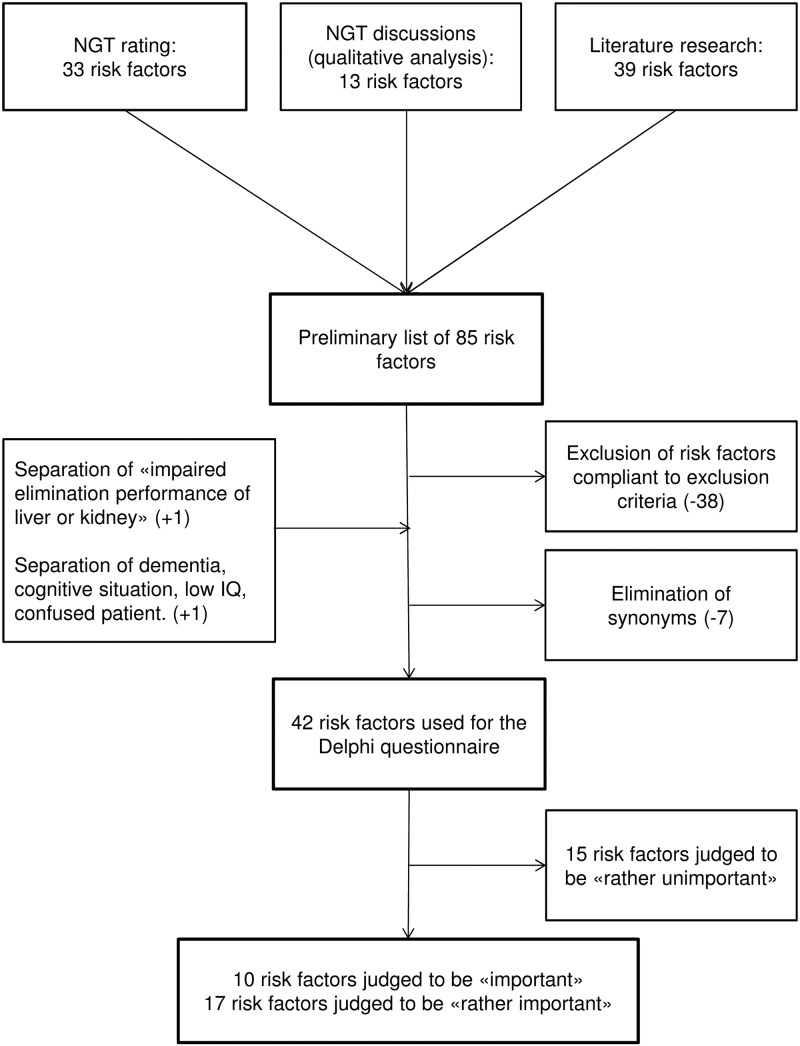

The NGT resulted in the identification of 33 items with 13 additional risk factors from the qualitative analysis of the discussion. The literature search delivered another 39 risk factors. The 85 risk factors were refined to produce 42 statements for the Delphi online questionnaire. Of these, 27 risk factors were judged to be ‘important’ or ‘rather important’.

Conclusions

The gathered risk factors may help to characterise and identify patients at risk for DRPs and may enable clinical pharmacists to guide and target preventive measures in order to limit the occurrence of DRPs. As a further step, these risk factors will serve as the basis for a screening tool to identify patients at risk for DRPs.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This research project followed a comprehensive triangulation method to gather risk factors for drug-related problems (DRPs), integrating expert opinion and literature data, which represents—to the best of our knowledge, a new approach in this topic.

Participating experts represented a wide variety of settings of patient care and steps in the medication process. This allowed a broad view on the topic of DRPs.

Inviting actively practising healthcare professionals as experts ensures the practical relevance of gathered risk factors.

The restricted number of participants in the nominal group technique may have limited the diversity of risk factors.

Introduction

Drug-related problems (DRPs), defined as ‘an event or circumstance involving drug therapy that actually or potentially interferes with desired health outcomes’,1 constitute a frequent safety issue among hospitalised patients leading to patient harm and increased healthcare costs. The term DRP embraces medication errors (MEs), adverse drug events (ADEs) and adverse drug reactions (ADRs). An ME is ‘any preventable event that may cause or lead to inappropriate medication use or patient harm while the medication is in the control of the healthcare professional, patient or consumer’.2 An ADE can be defined as ‘an injury—whether or not causally related to the use of a drug’.3 ADRs include ‘any response to a drug which is noxious and unintended, and which occurs at doses normally used in humans for prophylaxis, diagnosis or therapy of diseases, or for the modification of physiological functions’.4 In a systematic review of the years from 1991 to 2001, Krähenbühl-Melcher et al5 found that approximately 8% of hospitalised patients experience an ADE, and 5–10% of all drug prescriptions or drug applications are erroneous. In general internal medicine, about 15% of hospitalised patients and 12–17% of patients after discharge experience ADEs.6 7 In a group of 435 patients with discharge prescriptions from six different European countries, Paulino et al8 found a DRP in at least 63% of cases. In a Swiss study, 89 of 264 (34%) discharge prescriptions contained qualitative deficiencies and 72 (27%) showed DRPs.9 Thus, unplanned medication-related readmissions within a short time after discharge are frequent. In a multicentre observational study with a prospective follow-up, 5.6% of 12 793 unplanned admissions were medication related and of these 46.5% were potentially preventable.10

Because DRPs are an important problem and many of them are preventable, the specific risk factors that facilitate the occurrence of DRPs are of considerable interest. Previous studies have determined numerous risk factors for DRPs. In a literature review, female sex, polypharmacy, administration of drugs with a narrow therapeutic range or renal elimination, age over 65 years, and the use of oral anticoagulants and diuretics, were identified as relevant risk factors for ADEs and ADRs.5 Leendertse and colleagues considered risk factors, such as four or more comorbidities, polypharmacy, dependent living situation, impaired cognition, impaired renal function and non-adherence to medication regimen, as independent and significant risk factors potentially responsible for preventable hospital admission.10

These publications mostly rely on retrospective data and often focus on specific points in the whole care process of a patient, for example, hospital admission or discharge. Thus, data from the literature might not fully reflect the current problems of practising healthcare providers, especially when the information comes from another country with a completely different healthcare system. Few studies used a qualitative approach and attempted to reflect real-life situations by interviewing patients and healthcare providers. Risk factors reported in such studies differed from those found in quantitative studies. Howard et al11 conducted qualitative interviews with patients, general practitioners and community pharmacists, and concluded that communication failures and knowledge gaps at multiple stages in the medication process are important risk factors for preventable drug-related admissions. A combination of a qualitative as well as quantitative approach in gathering risk factors for DRPs has not been very prevalent in the current literature.

The aim of our study was to determine the individual risk factors for DRPs by combining current evidence from the literature with the professional experience of healthcare providers throughout the entire medication process. A triangulation process with quantitative and qualitative research methods in combination with consensus techniques served as a comprehensive approach to bridge the gap between research results and professional experience. It is hoped that this will lead to a list of risk factors for DRPs that accurately reflects the reality of daily practice. Risk factors collected will help to characterise and identify patients at risk for DRPs and will enable clinical pharmacists to guide and target preventive measures in order to minimise the occurrence of DRPs.

Methods

Nominal group technique

We used the nominal group technique (NGT) as a method for eliciting risk factors.12–14 We set up an expert panel consisting of two consultant hospital physicians (internal medicine and geriatrics), one emergency physician, one independent general practitioner, one clinical pharmacologist, one clinical pharmacist, one registered nurse, one home care nurse and two independent community pharmacists. The selection was based on the desirability of including a wide variety of experts from different settings, who are all involved in the patients’ medication management. Every expert had at least 5 years of professional experience, held a senior/executive position and was involved in daily patient care.

We set the duration of the NGT to 2 h. The moderator (CK) started the NGT meeting with a short introduction to the topic, with the aim of communicating the goal of the meeting and bringing the entire panel's knowledge about DRPs up to the same level. The participants were then asked to write down as many risk factors for DRPs as they could spontaneously think of. To avoid double-nominations, synonyms and very closely related terms (eg, ‘dementia’ and ‘cognitive impairment’), two clinical pharmacists (MLL and DS) and a community pharmacist (KEH) grouped the gathered risk factors while retaining each individual factor in the list. This work was done during the NGT. Subsequently, we presented the collected risk factors to the participants and invited them to rank each risk factor by its relevance. Each expert allocated 50 points (1.5 times the number of risk factors (=33)). We determined the amount of points by ourselves. Experts should be able to rank every risk factor, instead of choosing a defined number of most important factors. However, we limited the amount of points to force a consensus finding. Experts could assign as many points to as many of the risk factors as they wanted until all points were used. After the first ranking, we collected the ranking sheets and summarised the points to create a first ranking list. We discussed the ranking list with the expert panel, paying special attention to high and low scoring and discrepancies in the ranking among participants. In the second round of the ranking process, panellists had only as many points as the number of available risk factors, forcing them to fine-tune their previous ranking and to reach a consensus. We collected the rerated lists, created the new ranking, and then returned the resulting ranking list to all participants for final comments. Because we worked neither with patient data nor with patients themselves, we did not need ethical approval.

We audiotaped the entire discussion session of the expert panel and transcribed it into written text for qualitative analysis. One of the authors (DS) split the transcript into fragments and a second author (CPK) checked the splitting. Later the two authors (DS and CPK) together rearranged the fragments into groups treating related subjects. The whole grouping was then discussed by three authors (CPK, DS and MLL). Disagreements were discussed until the three authors reached consensus. We labelled every fragment with a unique index number to assure transparency.

Literature search

We conducted a non-systematic literature search to supplement the findings of the expert panel. Our goal was to gain an impression of the current state of research in the field of risk factors leading to DRPs. We wanted to know which risk factors for DRPs were described in the current literature and which were most mentioned. We conducted our search in PubMed and EMBASE. Language was restricted to German and English. The following search terms were used in EMBASE: ‘drug related problems’ AND ‘risk’/exp AND factors AND [systematic review]/lim AND ([english]/lim OR [german]/lim) AND [humans]/lim.; ‘Triage’/exp OR ‘triage’/syn AND (‘risk’/exp OR ‘risk’/syn) AND assessment AND ([child]/lim OR [adolescent]/lim OR [adult]/lim OR [aged]/lim) AND [humans]/lim AND [english]/lim AND ([meta-analysis]/lim OR [systematic review]/lim) AND ([article]/lim OR [review]/lim).; ‘Adverse drug reaction’/exp AND ‘screening’/exp AND ‘high risk patient’/exp AND [humans]/lim AND [english]/lim

The following search terms were used in PubMed:

“Triage/methods”[MAJR] AND “Risk Assessment/methods”[MeSH Terms]; “Drug Toxicity”[MAJR] AND “Risk Assessment/methods”[MeSH Terms]; ((“Drug Toxicity”[Mesh]) OR “Medication Errors”[Mesh]) AND “Triage/methods”[MAJR] AND “Risk Assessment/methods”[MeSH Terms]; “Medication Errors”[Mesh] AND “Triage/methods”[MAJR] AND “Risk Assessment/methods”[MeSH Terms]; (“Risk Factors”[MeSH Terms]) AND “Hospitalization/statistics and numerical data” [MAJR]

“Risk Assessment/methods”[MeSH Terms] AND “Medication Errors”[Mesh]

Titles and abstracts were screened for relevance. Abstracts needed to mention the terms ‘risk factors’, ‘predictors’ or ‘high risk’ in combination with ‘drug related problems’ or subterms of its definition.

We checked the reference list of each paper selected for further possible hits. Besides this literature search, we reviewed different tools focusing on the assessment of inappropriate prescribing, which we identified in a previous systematic review.15 Inappropriate prescribing is a known source of DRPs, ADEs and ADRs. Original publications of these tools were screened for risk factors associated with inappropriate prescribing that are connected with negative outcomes, for example, DRPs, ADEs, ADRs and rehospitalisation. PubMed and EMBASE were searched for validation studies using the name of the tool and, if necessary, ‘outcome’ or ‘assessment’ as MeSH terms or by checking publications that cited the original paper.

Delphi process

We validated the risk factors collected from the literature search and the NGT by using the Delphi technique.16 Before integrating the risk factors in the questionnaire, we condensed them by using the following exclusion criteria:

The risk factor is mentioned in only one of the relevant publications.

The risk factor set in the lowermost quartile of our NGTs ranking list is not mentioned anywhere else.

The risk factor is categorised as an issue of seamless care (eg, lack of communication between healthcare professionals, patient information and discharge management).

The risk factor represents a barely predictable event or circumstance (eg, unscheduled discharge, confusion of drug names by professionals).

We excluded seamless care issues, because they are not individual risk factors but instead reflect system failures; they are, therefore, not assessable for an individual patient. In addition, we combined synonyms in one term. Any ambiguous risk factors were discussed by experts to decide about their inclusion or exclusion on a case-by-case basis.

In a two-round online Delphi survey (Flexi Form, In 2.0 ed), following 2 months after the NGT, the NGT participants rated each risk factor on a four-item Likert scale (1=‘unimportant’, 2=‘rather unimportant’, 3=‘rather important’, 4=‘important’) according to its potential to cause DRPs.

The questionnaire for the second rating started 2 weeks after the end of the first rating and included the same questions as the first one, but the sequence represented the ranking list of the first round. We presented the median score and the IQR of each question to the participants to give them the possibility to consider the group's rating for their own re-rating. Below the Likert scale of each question, the number of participants who rated for the respective relevance was shown. After the second rating, the median scores and IQRs were calculated and a final ranking list of risk factors collected was established.

Results

NGT rating and literature search

The ranking process of the NGT resulted in 33 items (figure 1). The qualitative analysis of the discussion not only confirmed risk factors identified in the rating process but also revealed 13 additional risk factors. Main topics were high-risk drugs, communication issues between healthcare professionals, patient education and questions of responsibility. The literature search resulted in 39 additional factors that were not mentioned in the NGT.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of eliciting risk factors possibly leading to DRPs (NGT, nominal group technique; DRPs, drug-related problems).

Delphi questionnaire

In total, we gathered a preliminary list of 85 risk factors. Of these, we excluded 38 risk factors because they fulfilled our exclusion criteria (see table 1). Twice, we split a risk factor into two parts, and we eliminated seven synonyms. Ultimately, we used 42 risk factors in the Delphi questionnaire.

Table 1.

Risk factors excluded from the Delphi questionnaire, including information to their origin

| Excluded risk factors | |

|---|---|

| Mentioned in only one of the selected publications | Heart failure (L); liver disease (not hepatic impairment) (L); problems with ‘water works’ (L); antidepressant (L); drugs with positive inotrope effects (L), potassium channel activators (L); antibacterial drugs (L); laxatives (L); corticosteroids for inhalation (L), loperamide (L); statins (L); cephalosporins (L); compound analgesics (with opioids) (L); low-molecular-weight heparins (L); macrolide antibiotics (L); penicillin (L); aspirin (L); salbutamol (L); antihypertensives (L); bladder antimuscarinic drugs (L); cerebral vasodilators (L); nitroglycerine (L); ranitidine (L); 1st generation antihistamines (L) |

| Lowermost quartile of the NGT ranking list and not mentioned elsewhere | Money (N); Morbus Parkinson (N); xerostomia (N); oral bisphosphonate (N) |

| Seamless care issue or intervention to improve seamless care OR unpredictable event or circumstance | Unclear prescription/unclear or non-available dosage regimen at discharge (N); multiple treating physicians (L,N); missing instruction of relatives (N); medication-taking gap (N); briefing of the patient (L,Q); confusion of drug names (N); new medication/lots of changes/alternating dosages (N); changes in therapy: stop due to hospitalisation/discharge/generic medication (N,Q); unscheduled discharge (N) |

| Synonyms | |

| |

ADR, adverse drug reaction; L, literature search; N, NGT ranking list; NGT, nominal group technique; Q, qualitative analysis of the NGT.

The results of the Delphi technique are shown in tables 2 and 3. They are arranged by median score of the second round. In the second round, 10 risk factors were judged as ‘important’ (Likert scale: 4) concerning their contribution to the occurrence of DRPs, 17 risk factors were judged as ‘rather important’ (Likert scale: 3), 15 risk factors were judged as ‘rather unimportant’ (Likert scale: 2) and no risk factor was considered as ‘unimportant’ (Likert scale: 1). The sum of the IQRs changed from 30 in the first round to 20 in the second round, representing a stronger consensus between the participants. Finally, we created a list of 27 risk factors rated as important or rather important for the occurrence of DRPs.

Table 2.

Final ranking list of the 27 risk factors contributing to the occurrence of DRPs rated by the expert panel as ‘important’ (Likert scale: 4) or ‘rather important’ (Likert scale: 3)

| Risk factor | Delphi |

NGT |

Literature | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | IQR | Ranking list | Qualitative analysis | ||

| Dementia, cognitive situation, low IQ, confused patient | 4 | 4.00–4.00 | Yes | 10, 17, 18, 19, 20 | |

| Polypharmacy (number of drugs >5) | 4 | 4.00–4.00 | Yes | Yes | 10, 17, 18, 21, 22, 5 |

| Antiepileptics | 4 | 4.00–4.00 | Yes | 23, 24, 20, 25 | |

| Anticoagulants | 4 | 4.00–4.00 | Yes | 10, 21, 23, 26, 5 | |

| Combinations of NSAID and oral anticoagulants | 4 | 4.00–4.00 | Yes | 20 | |

| Insulin | 4 | 4.00–4.00 | Yes | 10, 23, 24 | |

| Missing information, half-knowledge of the patient, the patient does not understand the goal of the therapy | 4 | 4.00–3.25 | Yes | 11 | |

| Medication with a narrow therapeutic window | 4 | 4.00–3.25 | Yes | Yes | 5 |

| Non-adherence | 4 | 4.00–3.00 | Yes | 10 | |

| Polymorbidity | 3.5 | 4.00–3.00 | Yes | Yes | 10, 22 |

| Digoxin | 3 | 4.00–3.00 | 24, 20, 27 | ||

| Renal impairment (eGFR <30 mL/min) | 3 | 4.00–3.00 | Yes | 10, 22, 20 | |

| NSAIDs | 3 | 4.00–3.00 | Yes | 5, 10, 21, 23, 24, 25 | |

| Experience of ADR | 3 | 3.75–3.00 | Yes | Yes | 22 |

| Medication that is difficult to handle | 3 | 3.75–3.00 | Yes | ||

| Language issues (ie, non-native speakers) | 3 | 3.00–3.00 | Yes | Yes | |

| Diuretics | 3 | 3.00–3.00 | Yes | 5, 10, 19, 23, 24, 26, 25 | |

| Tricyclic antidepressants | 3 | 3.00–3.00 | 21, 20 | ||

| Hepatic impairment | 3 | 3.00–3.00 | Yes | 22, 20 | |

| Self-medication with non-prescribed medicines | 3 | 3.00–3.00 | Yes | Yes | |

| Impaired manual skills (causing handling difficulties) | 3 | 3.00–3.00 | Yes | ||

| Visual impairment | 3 | 3.00–3.00 | Yes | Yes | 17 |

| Anticholinergic drugs | 3 | 3.00–3.00 | 28 | ||

| Benzodiazepines | 3 | 3.00–3.00 | 21, 20, 28, 25, 29 | ||

| Opiates/opioids | 3 | 3.00–3.00 | 10, 23, 26, 20, 25 | ||

| Corticosteroids | 3 | 3.00–2.00 | 10, 23, 24 | ||

| Oral antidiabetics | 3 | 3.00–2.00 | 10, 23, 24 | ||

The sequence represents the ratings of the Delphi survey indicating median ratings and IQR, and appearance in the NGT ranking list, the qualitative analysis of the NGT and in the literature. Factors with no reference in the literature section were only mentioned by the experts.

ADR, adverse drug reaction; DRP, drug-related problem; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; NGT, nominal group technique; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Table 3.

Risk factors contributing to the occurrence of DRPs rated from the expert panel as ‘rather unimportant’ (Likert scale: 2) or ‘unimportant’ (Likert scale: 1) and therefore not included in the final list of risk factors

| Risk factor | Delphi |

NGT |

Literature | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | IQR | Ranking list | Qualitative analysis | ||

| Age | 2.5 | 3.75–2.00 | Yes | 30, 5 | |

| Extreme body weight (too high or too low) | 2 | 3.00–2.00 | Yes | ||

| Antiplatelet drugs | 2 | 3.00–2.00 | 10, 23, 24 | ||

| Drugs affecting the RAAS | 2 | 3.00–2.00 | 10, 23 | ||

| Patient living alone | 2 | 3.00–2.00 | Yes | 18, 19, 31 | |

| Calcium antagonists | 2 | 3.00–2.00 | 10, 23, 20 | ||

| Nitrates | 2 | 3.00–2.00 | 23, 24 | ||

| Patient's education about his therapy | 2 | 2.75–2.00 | Yes | 11 | |

| β-blockers | 2 | 2.00–2.00 | 10, 20, 23, 24, 25 | ||

| Antacids | 2 | 2.00–2.00 | |||

| High risk of falls, motion insecurity | 2 | 2.00–2.00 | Yes | Yes | 18, 19, 20, 25, 28, 29, 31 |

| Previous hospitalisation in the last 30 days | 2 | 2.00–2.00 | 17, 18, 30 | ||

| Need for caregiver at home | 2 | 2.00–2.00 | Yes | 10 | |

| Calcium containing drugs | 2 | 2.00–1.00 | 27 | ||

| Respiratory drugs | 2 | 3.00–1.00 | 10, 23, 26 | ||

The sequence represents the ratings of the Delphi survey indicating median ratings and IQR, and appearance in the NGT ranking list, the qualitative analysis of the NGT and in the literature. Factors with no reference in the literature section were only mentioned by the experts.

DRP, drug-related problem; NGT, nominal group technique; RAAS, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system.

Discussion

We were able to determine 27 risk factors that appear to contribute substantially to the occurrence of DRPs. The triangulation, for which we used the NGT with its rating process, the expert panel and a literature search, enhanced the accuracy of our findings and ensured their practical relevance. In agreement with previous quantitative studies, we identified expected and well-known risk factors in our literature search. The inclusion of an expert panel gave us valuable insight into problems healthcare professionals are confronted with and the risk factors they judge as important or not. As we expected, risk factors that were prevalent in the literature were mentioned by the experts as well, for example, some high-risk drugs (such as anticoagulants and insulin), polypharmacy and renal impairment. Apart from that, the expert panellists showed us valuable risk factors often seen in their daily practice and less described in the literature. Insufficient information transfer between the primary and secondary care setting was considered an important handicap in daily practice. Problems are considered to have already begun at hospital admission, where patients often arrive without being able to give information about their current long-term medication. During the hospital stay, the medication of the patient undergoes significant changes. Lack of communication among the different healthcare providers leads to confusion.

Community pharmacists reported about having insufficient access to patients’ medical records, which hinders them in advising the patient in a comprehensive way. Panellists from every healthcare area emphasised the importance of patient information. They were aware that patients’ knowledge about their medication is often incomplete. Self-medication is rarely mentioned in the dialogue with the healthcare professionals because the patient does not regard their vitamin pills and herbal supplements as real medication.

An increasing amount of patients speak a foreign language, which complicates communication. To improve the education of patients and to guarantee the transfer of information about patients’ medication, panellists acknowledged the benefit of appointing an individual who would be responsible for the medication management and education of the patient.

The experts stated that the medication manager would ideally be someone who could walk across all floors of the hospital, meeting with newly admitted patients, compiling a complete medication history and checking for DRPs. This medication manager would monitor the patient throughout the hospital stay and, at the patient's discharge, he or she would perform the final medication check to identify potential DRPs, and ensure that the patient understands the prescribed therapy and knows how to take the medication. After discharge, the medication manager would ensure that the correct information is shared with the community pharmacy and the general practitioner in order to guarantee seamless care. The medication manager would serve as a consultant and not as a replacement for the prescribing physician. The panellists considered clinical pharmacists or pharmacologists the most appropriate professionals for this task, due to their broad knowledge about medication.

The risk factor ‘age’ does not belong to the final list of most important risk factors. The experts stated clearly that an 80-year-old patient could be in a much healthier condition than one who is a 60 years old. When talking about geriatric patients, we are aware of risk factors such as polypharmacy, renal impairment, dementia and many more. The expert panel rated these risk factors as more important than the ‘age’ factor itself.

The composition of the expert panel was multidisciplinary by choice, because we aimed to bring together all stakeholders in the medication process of a patient. By performing an NGT instead of interviews, we gave the panellists the possibility not only to answer our questions, but to discuss their different views with other healthcare professionals. The panellists were highly motivated and discussed in an engaged and informative way. Despite their different professional backgrounds, they agreed on many discussion points. They appreciated the interdisciplinary exchange and found that it would be worthwhile to conduct such discussion rounds more frequently.

The ensuing Delphi process enabled the desired consensus-forming. By conducting the Delphi process with online questionnaires, where the participants were anonymous, we avoided any psychosocial biases. In the first round, the total number of IQRs was 30, whereas it was 20 in the second round. This means that the degree of consensus increased among the participants.

Study limitations

There are some general concerns about the validity and generalisability of information created by qualitative research methods. The Delphi and NGT approaches are both often criticised for showing a lack of research-based evidence concerning diverse feedback methods, and their influence on the validity and reproducibility of the decisions reached by the panel members.14 Other influences on the whole group dynamic are psychosocial biases, which were described by Pagliari et al.32 We addressed this by assigning each panellist a place in the NGT in order to avoid grouping of friends or panellists from the same profession. We decided to use a small expert panel with 10 panellists. Although larger groups would provide a more extensive representation, they may be difficult to lead, which may only be resolved by introducing more structure and role definition into the process.32

A limitation of our Delphi technique after employing NGT is the restricted number of participants. We chose the very same motivated experts for the Delphi and the NGT, because they were already familiar with the topic.

In conclusion, the gathered risk factors may help to characterise and identify patients at risk for DRPs, and may enable clinical pharmacists to guide and target preventive measures in order to limit the occurrence of DRPs. In a further step, these risk factors will serve as the basis for a screening tool to identify patients at risk for DRPs.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the members of the expert panel who contributed to our findings.

Footnotes

Contributors: CPK contributed to the study design, the analysis and interpretation of the data, manuscript writing, final approval of the version to be published, and was substantially involved in the literature search, and conduction of the nominal group technique (NGT) and the Delphi questionnaire. DS contributed to the study design, the analysis and interpretation of the data, the literature search, and conduction of the NGT and the Delphi questionnaire. KEH contributed to manuscript review and final approval of the version to be published. MLL contributed to the study design and the analysis and interpretation of the data, conduction of the NGT and Delphi survey, and also contributed to the manuscript review and final approval of the version to be published.

Funding: The study is financially supported by an unrestricted research grant from the Swiss Society of Public Health Administration and Hospital Pharmacists (GSASA).

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Pharmaceutical Care Network Europe (PCNE). The definition of drug-related problems 2009. http://www.pcne.org/sig/drp/drug-related-problems.php (accessed 22 Jun 2013).

- 2.National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention (NCC MERP) About Medication Errors 2013. http://www.nccmerp.org/aboutMedErrors.html (accessed 22 Jun 2013).

- 3.van den Bemt PM, Egberts TC, de Jong-van den Berg LT et al. Drug-related problems in hospitalised patients. Drug Saf 2000;22:321–33. 10.2165/00002018-200022040-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.No authors listed]. International drug monitoring: the role of national centres. Report of a WHO meeting. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 1972;498:1–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krähenbühl-Melcher A, Schlienger R, Lampert M et al. Drug-related problems in hospitals: a review of the recent literature. Drug Saf 2007;30:379–407. 10.2165/00002018-200730050-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schlienger RG, Luscher TF, Schoenenberger RA et al. Academic detailing improves identification and reporting of adverse drug events. Pharm World Sci 1999;21:110–15. 10.1023/A:1008631926100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF et al. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med 2003;138:161–7. 10.7326/0003-4819-138-3-200302040-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paulino EI, Bouvy ML, Gastelurrutia MA et al. Drug related problems identified by European community pharmacists in patients discharged from hospital. Pharm World Sci 2004;26:353–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eichenberger PM, Lampert ML, Kahmann IV et al. Classification of drug-related problems with new prescriptions using a modified PCNE classification system. Pharm World Sci 2010;32:362–72. 10.1007/s11096-010-9377-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leendertse AJ, Egberts AC, Stoker LJ et al. Frequency of and risk factors for preventable medication-related hospital admissions in the Netherlands. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:1890–6. 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Howard R, Avery A, Bissell P. Causes of preventable drug-related hospital admissions: a qualitative study. Qual Saf Health Care 2008;17:109–16. 10.1136/qshc.2007.022681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fink A, Kosecoff J, Chassin M et al. Consensus methods: characteristics and guidelines for use. Am J Public Health 1984;74:979–83. 10.2105/AJPH.74.9.979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Campbell SM, Cantrill JA. Consensus methods in prescribing research. J Clin Pharm Ther 2001;26:5–14. 10.1046/j.1365-2710.2001.00331.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cantrill JA, Sibbald B, Buetow S. The Delphi and nominal group techniques in health services research. Int J Pharm Pract 1996;4:67–74. 10.1111/j.2042-7174.1996.tb00844.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaufmann CP, Tremp R, Hersberger KE et al. Inappropriate prescribing: a systematic overview of published assessment tools. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2014;70:1–11. 10.1007/s00228-013-1575-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith F. Research methods in pharmacy practice. 1st edn Pharmaceutical Press, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCusker J, Bellavance F, Cardin S et al. Detection of older people at increased risk of adverse health outcomes after an emergency visit: the ISAR screening tool. J Am Geriatr Soc 1999;47:1229–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meldon SW, Mion LC, Palmer RM et al. A brief risk-stratification tool to predict repeat emergency department visits and hospitalizations in older patients discharged from the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med 2003;10:224–32. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2003.tb01996.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Runciman P, Currie CT, Nicol M et al. Discharge of elderly people from an accident and emergency department: evaluation of health visitor follow-up. J Adv Nurs 1996;24:711–18. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1996.02479.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gallagher P, O'Mahony D. STOPP (Screening Tool of Older Persons’ potentially inappropriate Prescriptions): application to acutely ill elderly patients and comparison with Beers’ criteria. Age Ageing 2008;37:673–9. 10.1093/ageing/afn197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hanlon JT, Pieper CF, Hajjar ER et al. Incidence and predictors of all and preventable adverse drug reactions in frail elderly persons after hospital stay. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2006;61:511–15. 10.1093/gerona/61.5.511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Onder G, Petrovic M, Tangiisuran B et al. Development and validation of a score to assess risk of adverse drug reactions among in-hospital patients 65 years or older: the GerontoNet ADR risk score. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:1142–8. 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Howard RL, Avery AJ, Slavenburg S et al. Which drugs cause preventable admissions to hospital? A systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2007;63:136–47. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02698.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Howard RL, Avery AJ, Howard PD et al. Investigation into the reasons for preventable drug related admissions to a medical admissions unit: observational study. Qual Saf Health Care 2003;12:280–5. 10.1136/qhc.12.4.280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamilton H, Gallagher P, Ryan C et al. Potentially inappropriate medications defined by STOPP criteria and the risk of adverse drug events in older hospitalized patients. Arch Intern Med 2011;171:1013–19. 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davies EC, Green CF, Taylor S et al. Adverse drug reactions in hospital in-patients: a prospective analysis of 3695 patient-episodes. PLoS ONE 2009;4:e4439 10.1371/journal.pone.0004439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lipton HL, Bero LA, Bird JA et al. The impact of clinical pharmacists’ consultations on physicians’ geriatric drug prescribing. A randomized controlled trial. Med Care 1992;30:646–58. 10.1097/00005650-199207000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laroche ML, Charmes JP, Nouaille Y et al. Is inappropriate medication use a major cause of adverse drug reactions in the elderly? Br J Clin Pharmacol 2007;63:177–86. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02831.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berdot S, Bertrand M, Dartigues JF et al. Inappropriate medication use and risk of falls—a prospective study in a large community-dwelling elderly cohort. BMC Geriatr 2009;9:30 10.1186/1471-2318-9-30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marcantonio ER, McKean S, Goldfinger M et al. Factors associated with unplanned hospital readmission among patients 65 years of age and older in a Medicare managed care plan. Am J Med 1999;107:13–17. 10.1016/S0002-9343(99)00159-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rowland K, Maitra AK, Richardson DA et al. The discharge of elderly patients from an accident and emergency department: functional changes and risk of readmission. Age Ageing 1990;19:415–18. 10.1093/ageing/19.6.415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pagliari C, Grimshaw J, Eccles M. The potential influence of small group processes on guideline development. J Eval Clin Pract 2001;7:165–73. 10.1046/j.1365-2753.2001.00272.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]