Abstract

BACKGROUND

Epidemiological data for cardiac abnormality predating decreased kidney function are sparse. We investigated the associations of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T (hs-cTnT) and N-terminal pro–brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) risk in a community-based cohort.

STUDY DESIGN

A prospective cohort study.

SETTING & PARTICIPANTS

10,749 white and black participants at the fourth visit (1996–1998) of the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study with follow-up through 2010.

PREDICTOR

hs-cTnT (3, 6, 9, and 14 ng/L) and NT-proBNP (41.6, 81.0, 142.5, and 272.5 pg/mL) levels were divided into five categories at the same percentiles (32th, 57th, 77th, and 91th; corresponding to ordinary thresholds of hs-cTnT), with the lowest category as a reference.

OUTCOMES

Incident ESRD defined as initiation of dialysis, transplantation, or death due to kidney disease.

MEASUREMENTS

Relative risk and risk prediction of ESRD according to hs-cTnT and NT-proBNP based on Cox proportional hazards models.

RESULTS

During a median follow-up of 13.1 years, 235 participants developed ESRD (1.8 cases per 1,000 person-years). hs-cTnT and NT-proBNP were associated with ESRD risk independently of each other and of potential confounders including kidney function and albuminuria (adjusted HR for highest category, 4.43 [95% CI, 2.43–8.09] and 2.28 [95% CI, 1.44–3.60], respectively). For hs-cTnT, the association was significant even at the third category (HR for 6–8 ng/L hs-cTnT, 2.74 [95% CI, 1.54–4.88]). Their associations were largely consistent even among persons without decreased kidney function or history of cardiovascular disease. hs-cTnT and NT-proBNP both significantly improved ESRD prediction (c-statistic differences of 0.0084 [95% CI, 0.0005–0.0164] and 0.0045 [95% CI, 0.0004–0.0087], respectively, from 0.884 with conventional risk factors).

LIMITATIONS

Relatively small number of ESRD cases and single measurement of hs-cTnT and NT-proBNP.

CONCLUSIONS

hs-cTnT and NT-proBNP independently predicted ESRD risk in the general population, with more evident results for hs-cTnT. These results suggest the involvement of cardiac abnormality, particularly cardiac injury, in the progression of reduced kidney function and/or may reflect the useful property of hs-cTnT as an end-organ damage marker.

INDEX WORDS: high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T (hs-cTnT), N-terminal pro–brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), cardiac injury, cardiac marker, risk factor, risk prediction, incident end-stage renal disease (ESRD), kidney disease progression, Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study

A close pathophysiological relationship between the kidney and heart is well known.1–4 There are several mechanisms by which decreased kidney function might lead to cardiovascular disease (CVD) such as imbalance of salt and fluid, activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) and sympathetic nervous system, endothelial dysfunction, and oxidative stress.1, 5–7 Indeed, numerous epidemiological studies have reported a higher CVD risk among those with kidney disease as compared to those without.8–14

In contrast, epidemiological data as to whether cardiac abnormality predates kidney disease progression are sparse. A few small studies have demonstrated that cardiac abnormality (e.g., left ventricular hypertrophy and reduced systolic function) are predictors for kidney disease progression.12, 15 However, these studies investigated patients with advanced kidney disease, and those cardiac manifestations may merely reflect long-standing or severe decreases in kidney function. A higher risk of kidney disease progression was observed among those with history of CVD as compared to those without.16 However, treatment or clinical examinations in those with CVD (e.g., diuretics or iodinated contrast) may have confounded this association.

In this context, a recent study using a subsample (n ~1,000) from TREAT (Trial to Reduce Cardiovascular Events With Aranesp Therapy) demonstrated that the markers indicating cardiac injury and overload, troponin T and N-terminal pro–brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), were independently associated with risk for end-stage renal disease (ESRD).17 However, every participant in this study had diabetic nephropathy and anemia, and a majority of patients had a history of CVD, leaving uncertainty in an etiological association of cardiac markers with ESRD, particularly in the general population. Therefore, the objective of this study was to investigate the associations of troponin T measured by a high-sensitivity assay (high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T [hs-cTnT]) and NT-proBNP with ESRD risk in a community-based cohort.

METHODS

Study Population

The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study is a prospective cohort of 15,792 individuals aged 45–64 years at visit 1 (1987–1989) from 4 US communities (Forsyth County, NC; Jackson, MS; suburban Minneapolis, MN; and Washington County, MD). There were three short-term follow-up examinations in 1990–1992 (visit 2), 1993–1995 (visit 3) and 1996–1998 (visit 4). Out of 15,792 participants, 11,656 individuals (74%) attended visit 4, at which hs-cTnT and NT-proBNP were measured. For this study, we excluded individuals who were neither white nor black (n=31) or who had missing data of hs-cTnT or NT-proBNP (n=406), covariates (n=406) and incident ESRD (n=42). Individuals with prevalent ESRD and chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage 5 (kidney failure) at visit 4 were also excluded (n=22), leaving 10,749 individuals for this study. All individuals provided written informed consent.

Cardiac Markers

Plasma hs-cTnT was measured using a novel highly sensitive assay with a lower measurable limit of 3 ng/L (Elecsys Troponin T; Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). The NT-proBNP was measured by an electrochemiluminescent immunoassay on an automated Cobas e411 analyzer (Roche Diagnostics) with a lower measurable limit of 5 pg/mL. The coefficient of variation of these cardiac markers was <7%.18 We assigned half of the lower limit of each marker for participants with unmeasurable levels.

Covariates

Information on demographics, lifestyle, and medical history was collected at visit 4 by trained interviewers using standardized questionnaires. Body mass index (BMI) was defined as weight in kilograms divided by height (in meters) squared. Blood pressure was measured twice by certified technicians using a sphygmomanometer, and the average was recorded. Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg, or use of antihypertensive medications. We defined diabetes mellitus as fasting serum glucose ≥126 mg/dL, non-fasting glucose ≥200 mg/dL, self-reported diagnosis of diabetes, or antidiabetic medications usage. Medication use was verified by the inspection of medication bottles. Prevalent CVD included history of coronary heart disease, stroke, and heart failure. Coronary disease and stroke were defined as self-reported history before visit 1, or adjudicated cases between visits 1 and 4. Prevalent heart failure was defined as self-reported treatment or the Gothenburg19 stage 3 at visit 1 or hospitalization for heart failure between visits 1 and 4. Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using the CKD-EPI (CKD Epidemiology Collaboration) creatinine equation.20 Albuminuria was ascertained as urinary albumin-creatinine ratio (ACR).21

Outcome Assessment

Incident ESRD was defined as initiation of dialysis, transplantation, or death due to kidney disease.22 Cases with dialysis and transplantation were identified by linkage to the US Renal Data System (USRDS), which captures information about all Americans who receive renal replacement therapy or are awaiting kidney transplantation.23 Participants who were free of ESRD by December 31, 2010 were administratively censored.

Statistical Analysis

As previously done,18 hs-cTnT was divided into five categories mainly based on the assay limit of measurement (3 ng/L), limit for reliable detection (5 ng/L), and a clinical threshold corresponding to the 99th percentile in healthy individuals specified by the manufacturer (14 ng/L), i.e., <3 (unmeasurable), 3–5, 6–8, 9–13, and ≥14 ng/L. These thresholds corresponded to 32th, 57th, 77th, and 91st percentiles in our study sample. To compare the two cardiac markers, NT-proBNP was also divided into five categories based on these percentiles corresponding to 41.6, 81.0, 142.5, and 272.5 pg/mL. It was also evaluated as an ordinal variable using quintiles and as a dichotomous variable using the clinical cutpoint (< vs. ≥400 pg/mL).24 Baseline characteristics were summarized according to the five categories of hs-cTnT and NT-proBNP, and the differences across the categories were assessed by the chi-square test and the ANOVA, as appropriate. We also evaluated the correlation between these cardiac markers and kidney measures (eGFR and ACR).

To visualize the potentially non-linear association with ESRD, incidence rate adjusted for age, gender and race was estimated using a Poisson regression model with linear splines (four knots corresponding to the five categories of cardiac markers). Subsequently, we quantified the association of five categories of hs-cTnT and NT-proBNP with incident ESRD using Cox proportional hazards models. We implemented several models to evaluate the impact of potential confounders. Model 1 was unadjusted, and model 2 was adjusted for age, gender, and race. Model 3 was further adjusted for systolic blood pressure, antihypertensive medication, smoking, alcohol intake, education level, BMI, total and HDL cholesterols, diabetes, and history of CVD. Model 4 was additionally adjusted for eGFR and ACR.25 Model 5 was further adjusted for the other cardiac marker (i.e., hs-cTnT in the analysis of NT-proBNP, and NT-proBNP in the analysis of hs-cTnT).

We conducted several sensitivity analyses to evaluate the robustness of our findings. First, we assessed potential interactions by stratifying the study sample by age (< vs. ≥65 years), gender, race (white vs. black), smoking (former/never vs. current), BMI (< vs. ≥30 kg/m2) and presence/absence of diabetes, hypertension, reduced eGFR (< vs. ≥60 ml/min/1.73m2), high albuminuria (ACR < vs. ≥30 mg/g), and history of CVD. Due to sparse data in some categories of cardiac markers within subgroups, we estimated hazard ratio (HR) for 2-fold increment of each cardiac marker for these stratified analyses. Interactions were tested by likelihood ratio test comparing models with and without product terms of interest. Second, among those without prevalent CVD, we examined whether the association between cardiac markers and ESRD was independent of CVD outcomes that occurred during follow-up by treating these cases as time-varying covariates. Finally, we conducted competing risk analysis with death as a competing endpoint of ESRD.26

To assess the incremental value of hs-cTnT and NT-proBNP in risk prediction, C statistic, categorical and continuous net reclassification improvement (NRI), and integrated discrimination improvement for the time frame of 10 years were computed from two models incorporating Model 4 variables with and without continuous hs-cTnT or NT-proBNP (both were log-transformed). Based on previous literature,25 10-year risks of 10% and 30% were used as thresholds for categorical NRI. All analyses were carried out with Stata version 12.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX), and a P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

As compared to those with lower hs-cTnT, individuals with higher hs-cTnT levels were more likely to be older, male, and black and have generally higher cardiovascular risk profile (e.g., higher BMI and blood pressure, higher levels of ACR and NT-proBNP, more prevalent diabetes and history of CVD, and lower levels of HDL cholesterol and eGFR) (Table 1). Similar patterns were observed among individuals with higher NT-proBNP levels (Table S1, available as online supplementary material). A few exceptions were the U-shaped patterns observed for the proportion of blacks, males, and diabetes and BMI levels across NT-proBNP categories. Both hs-cTnT and NT-proBNP were mildly correlated with each other (ρ=0.20), eGFR (ρ=−0.22 and −0.24, respectively), and ACR (ρ=0.19 and 0.26) (Table S2).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics by high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T categories

| Variable | Category 1: <3 ng/L |

Category 2: 3–5 ng/L |

Category 3: 6–8 ng/L |

Category 4: 9–13 ng/L |

Category 5: ≥14 ng/L |

P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of participants | 3,417 (31.8) | 2,696 (25.1) | 2,197 (20.4) | 1,467 (13.7) | 972 (9.0) | |

| Age (y) | 60.7 (5.1) | 62.4 (5.5) | 63.7 (5.5) | 65.1 (5.6) | 65.5 (5.6) | <0.001 |

| African American | 739 (21.6) | 525 (19.5) | 477 (21.7) | 338 (23.0) | 265 (27.3) | <0.001 |

| Male sex | 748 (21.9) | 1069 (39.6) | 1203 (54.8) | 958 (65.3) | 754 (77.6) | <0.001 |

| Education level | <0.001 | |||||

| Basic level | 531 (15.5) | 488 (18.1) | 423 (19.3) | 339 (23.1) | 265 (27.3) | |

| Intermediate | 1553 (45.5) | 1158 (43.0) | 902 (41.1) | 557 (38.0) | 361 (37.1) | |

| Advanced | 1333 (39.0) | 1050 (38.9) | 872 (39.7) | 571 (38.9) | 346 (35.6) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.2 (5.6) | 28.6 (5.5) | 29.1 (5.6) | 29.6 (5.6) | 29.7 (5.6) | <0.001 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 124.5 (17.9) | 126.5 (18.2) | 128.6 (18.9) | 131.4 (19.8) | 132.3 (21.1) | <0.001 |

| Diastolic BP(mmHg) | 70.6 (9.9) | 70.9 (10.0) | 71.3 (10.3) | 71.5 (10.9) | 71.2 (11.8) | 0.02 |

| Antihypertensive use | 1171 (34.3) | 1048 (38.9) | 1014 (46.2) | 764 (52.1) | 661 (68.0) | <0.001 |

| Current smoking | 728 (21.3) | 349 (12.9) | 235 (10.7) | 153 (10.4) | 126 (13.0) | <0.001 |

| Current drinker | 1781 (52.1) | 1397 (51.8) | 1076 (49.0) | 660 (45.0) | 412 (42.4) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 355 (10.4) | 330 (12.2) | 376 (17.1) | 330 (22.5) | 385 (39.6) | <0.001 |

| Prevalent CVDb | 307 (9.0) | 330 (12.2) | 358 (16.3) | 307 (20.9) | 371 (38.2) | <0.001 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 5.3 (0.9) | 5.2 (0.9) | 5.1 (1.0) | 5.1 (1.0) | 5.0 (1.1) | <0.001 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.4 (0.4) | 1.3 (0.4) | 1.2 (0.4) | 1.2 (0.4) | 1.1 (0.4) | 0.01 |

| eGFR, (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 87.5 (13.9) | 85.6 (13.8) | 83.2 (14.7) | 81.4 (15.7) | 76.4 (19.6) | <0.001 |

| eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 | 95 (2.8) | 108 (4.0) | 145 (6.6) | 140 (9.5) | 197 (20.3) | <0.001 |

| Urine ACR (mg/g) | 3.4 [1.7–6.5] | 3.5 [1.7–6.8] | 3.6 [1.7–7.5] | 4.3 [1.9–10.9] | 6.4 [2.5–30.5] | <0.001 |

| Urine ACR ≥30 mg/g | 152 (4.5) | 131 (4.9) | 181 (8.2) | 173 (11.8) | 245 (25.2) | <0.001 |

| NT-proBNP (pg/mL) | 60.5 [30.4–110.0] | 63.4 [32.1–119.1] | 67.3 [31.9–131.8] | 79.2 [38.5–170.6] | 126.6 [54.2–354.8] | <0.001 |

Note: Values for categorical variables are given as number (percentage); values for continuous variables are given as mean ± standard deviation or median [interquartile range].

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; ACR, albumin-creatinine ratio; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro–brain natriuretic peptide.

Includes coronary vascular disease, stroke, and heart failure.

Associations of Cardiac Markers With ESRD

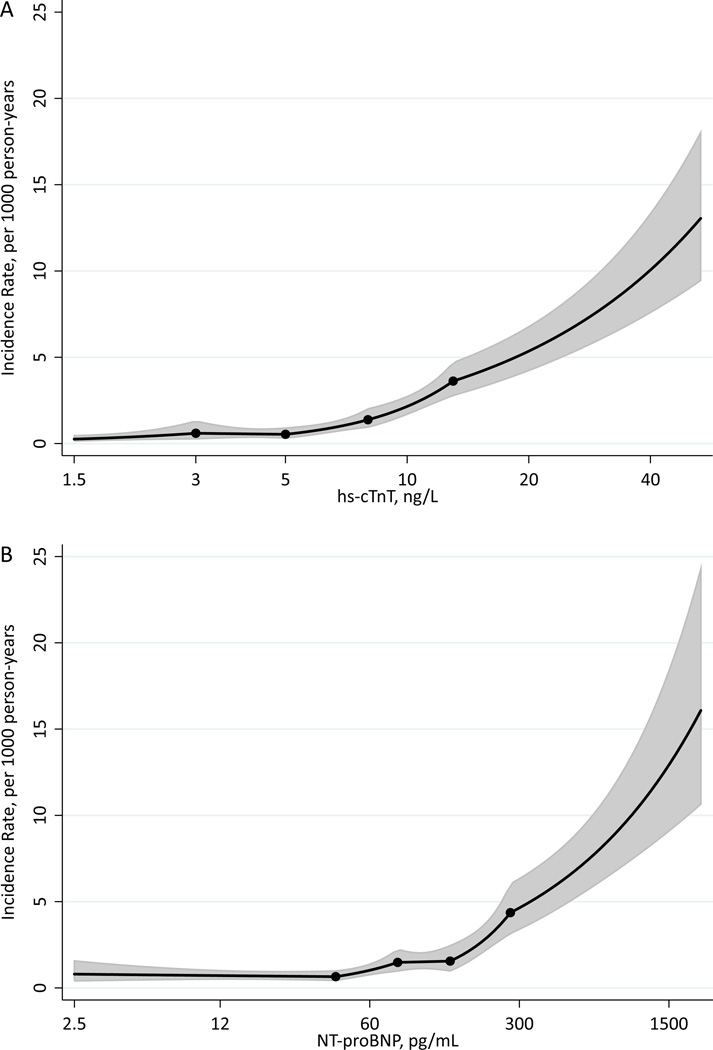

A total of 235 ESRD cases occurred during a median follow-up of 13.1 years (crude incidence rate, 1.8 per 1,000 person-years). Crude incidence rate was higher in categories with higher hs-cTnT and NT-proBNP, with a risk gradient between the highest and lowest categories of ~30-fold for hs-cTnT and ~10-fold for NT-proBNP (Table S3). The demographically adjusted incidence rate of ESRD steadily increased with hs-cTnT level above the reliably detectable limit, 5 ng/L (Figure 1A). In contrast, the adjusted incidence rate of ESRD was largely flat for NT-proBNP levels below ~150 pg/mL but sharply increased above that level (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

A. B. Adjusted incidence rates of ESRD by hs-cTnT (A) and NT-proBNP (B) Incidence rate per 1,000 person-year adjusted for age, race and gender; trimmed at 0.5% and 99.5%

The associations of hs-cTnT and NT-proBNP with incident ESRD remained significant after further adjustment for each other and potent predictors of ESRD such as diabetes, blood pressure, eGFR, and ACR (HRs of 4.43 [95% CI, 2.43–8.09] and 2.28 [1.44–3.60] in category 5 compared to category 1 , respectively, in model 5) (Table 2). The HRs for corresponding categories were consistently larger for hs-cTnT than NT-proBNP. Indeed, participants in hs-cTnT categories 3 and 4 (with subclinical hs-cTnT levels [6–13 ng/L]) had also significantly higher risk of ESRD compared to those with unmeasurable levels (HRs of 2.74 [95% CI, 1.54–4.88] and 3.04 [1.68–5.49], respectively, in model 5), whereas category 3 of NT-proBNP did not reach statistical significance. The independent associations of hs-cTnT and NT-proBNP with ESRD were confirmed in their cross-categories (Table S4). Similar associations with ESRD were observed for NT-proBNP using its quintiles (Table S5) or clinical cutpoint of 400 pg/mL (Table S6). Competing risk analysis provided largely similar results for two cardiac markers (Table S7).

Table 2.

Hazard Ratio of Incident End-Stage Renal Disease for Categories of hs-cTnT and NT-pro-BNP

| Category 2 | Category 3 | Category 4 | Category 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hs-cTnT | ||||||||

| 3–5 ng/L | 6–8 ng/L | 9–13 ng/L | ≥ 14 ng/L | |||||

| No. | 2,696 | 2,197 | 1,467 | 972 | ||||

| Model 1 | 2.00‡ (1.08–3.68) | 4.59* (2.64–8.00) | 7.53* (4.33–13.10) | 28.76* (17.17–48.18) | ||||

| Model 2 | 2.03‡ | (1.10–3.77) | 4.57* | (2.60–8.05) | 7.45* | (4.20–13.24) | 28.55* | (16.46–49.52) |

| Model 3 | 1.91‡ | (1.03–3.53) | 3.65* | (2.06–6.45) | 4.93* | (2.75–8.83) | 13.12* | (7.41–23.21) |

| Model 4 | 1.82 | (0.98–3.37) | 2.74† | (1.54–4.88) | 3.04* | (1.68–5.49) | 4.44* | (2.43–8.09) |

| Model 5 | 1.82 | (0.98–3.37) | 2.74† | (1.54–4.88) | 3.04* | (1.68–5.49) | 4.43* | (2.43–8.09) |

| NT-proBNP | ||||||||

| 41.6–<81.0 pg/mL | 81.0–<142.5 pg/mL | 142.5–<272.5 pg/mL | ≥272.5 pg/mL | |||||

| No. | 2,699 | 2,195 | 1,469 | 973 | ||||

| Model 1 | 1.29 | (0.83–2.01) | 1.57‡ | (1.01–2.46) | 2.78* | (1.80–4.29) | 9.33* | (6.34–13.74) |

| Model 2 | 1.63‡ | (1.04–2.55) | 2.17† | (1.37–3.44) | 3.80* | (2.42–5.98) | 11.48* | (7.63–17.27) |

| Model 3 | 1.53 | (0.98–2.41) | 2.05† | (1.29–3.25) | 3.17* | (2.00–5.02) | 6.84* | (4.43–10.57) |

| Model 4 | 1.04 | (0.66–1.64) | 1.35 | (0.85–2.15) | 1.92† | (1.21–3.05) | 2.34* | (1.48–3.05) |

| Model 5 | 1.04 | (0.66–1.64) | 1.34 | (0.84–2.14) | 1.91† | (1.20–3.04) | 2.28* | (1.44–3.60) |

P<0.001

P<0.01

P<0.05

Note: Values are given as hazard ratio (95% confidence interval). Category 1 is reference group for hs-cTnT (<3 ng/L; n=3,417) and NT-proBNP (<41.6 pg/mL; n=3,413). Model 1 was unadjusted; model 2 was adjusted for age, gender, and race; model 3 was further adjusted for known cardiovascular and kidney risk factors( i.e., systolic blood pressure, antihypertensive medication, smoking, alcohol intake, level of education, body mass index, total and high-density lipoprotein cholesterols, diabetes, history of cardiovascular disease); model 4 was additionally adjusted for kidney disease measures, estimated glomerular filtration rate and albuminuria (albumin-creatinine ratio) at baseline; and model 5 was further adjusted for NTproBNP or hs-cTnT, as appropriate.

Abbreviations: hs-cTnT, high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro–brain natriuretic peptide

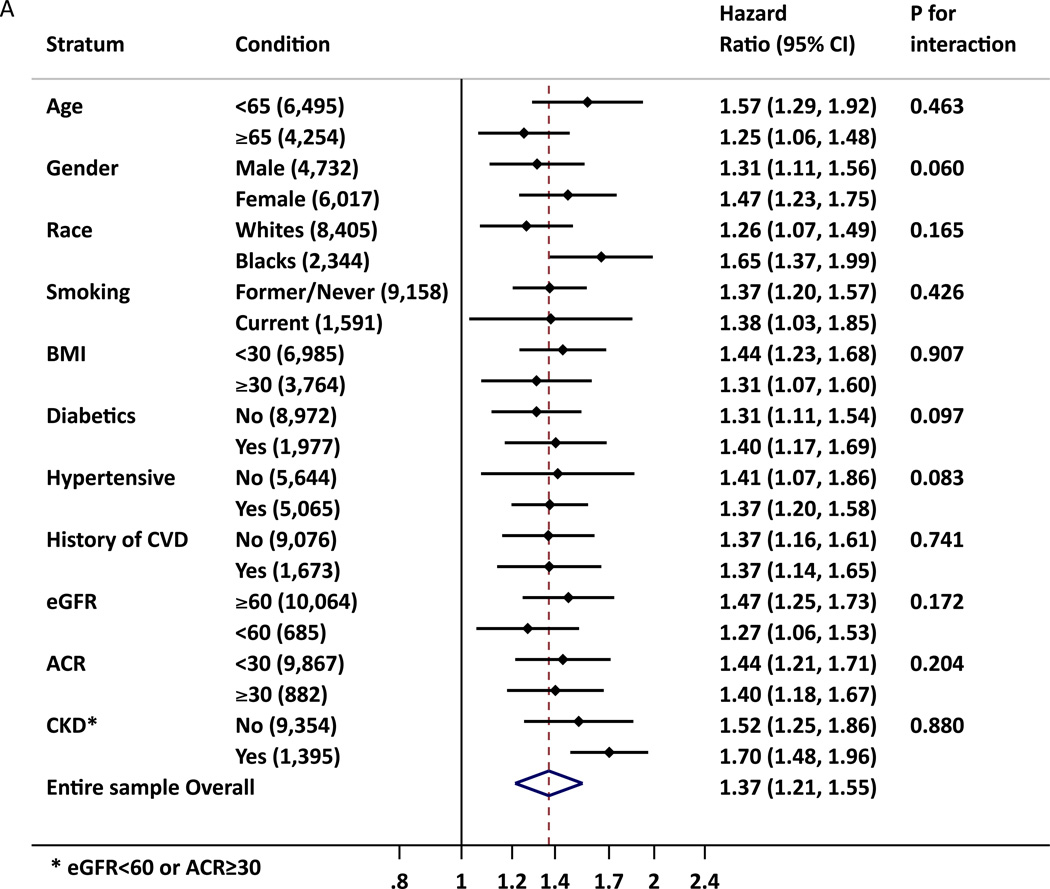

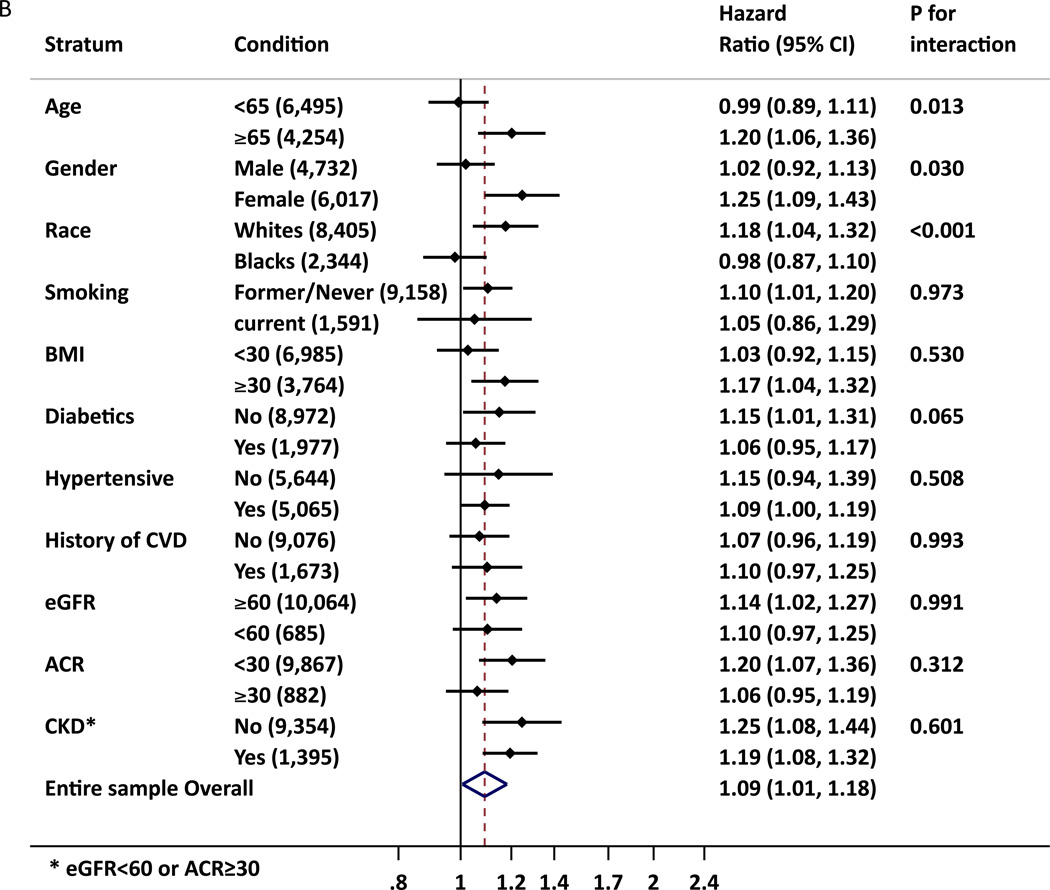

hs-cTnT was significantly associated with incident ESRD in all subgroups tested including those without CKD or CVD at baseline, whereas some subgroups did not reach significance for NT-proBNP (Figure 2). Nevertheless, out of 22 potential interactions tested, statistical significance was observed in age, race and gender groups for NT-proBNP, with higher relative risk of ESRD in older, female and whites than in their counterpart groups. We also observed borderline significant interaction for gender for hs-cTnT. Among those without a history of CVD, when incident CVD was accounted for as a time-varying covariate, the associations remained significant (Table S8).

Figure 2.

A. B. Adjusted Hazard Ratio of ESRD for 2-fold increment of hs-cTnT (A) and NT-proBNP (B) in demographic and clinical subgroups. The adjustment was based on model 5 (age, gender, race, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, total and HDL cholesterols, history of cardiovascular disease, smoking, alcohol intake, education level, BMI, eGFR, albuminuria(ACR), and hs-cTnT or NT-proBNP, as appropriate)

* CKD was defined as eGFR < 60 mL/min or ACR ≥ 30mg/g

ESRD Prediction With hs-cTnT and NT-proBNP

The C-statistic for the prediction of ESRD risk was already high with model 4 variables (0.884 [95% CI, 0.858–0.909]) but was significantly improved by adding hs-cTnT and NT-proBNP as continuous variables (c-statistic differences of 0.0084 [95% CI, 0.0005–0.0164; p=0.04] and 0.0045 [95% CI, 0.0004–0.0087; p=0.03], respectively) (Table 3). The addition of hs-cTnT to model 4 resulted in significantly increased continuous NRI and integrated discrimination improvements, while NT-proBNP showed significantly increased continuous NRI.

Table 3.

Model performance measures with the addition of continuous hs-cTnT or NT-proBNP to Model 4 variables.

| C-statistic | NRI, categorical** | NRI, continuous | IDI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 4 | 0.884 (0.858 to 0.909) | |||

| hs-cTnT | 0.892‡ (0.869 to 0.916) | 0.001 (−0.037 to 0.040) | 0.195† (0.067 to 0.322) | 0.010† (0.003 to 0.018) |

| NT-proBNP | 0.888‡ (0.864 to 0.913) | 0.005 (−0.024 to 0.034) | 0.148‡ (0.020 to 0.276) | 0.004 (−0.001 to 0.009) |

| hs-cTnT and NT-proBNP | 0.894‡ (0.871 to 0.917) | 0.005 (−0.036 to 0.046) | 0.176† (0.048 to 0.303) | 0.012† (0.003 to 0.020) |

P<0.001

P<0.01

P<0.05

10-year risks of 10% and 30% were used as thresholds for categorical NRI.

Note: Data are given as value (95% confidence interval). All prediction statistics were based on 10-year predicted risk. Model 4 variables included: age, gender, race, systolic blood pressure, antihypertensive medication, smoking, alcohol intake, level of education, body mass index, total and high-density lipoprotein cholesterols, diabetes, history of cardiovascular disease, estimated glomerular filtration rate and albuminuria (albumin-creatinine ratio) at baseline

Abbreviations: hs-cTnT, high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro–brain natriuretic peptide; net reclassification improvement (NRI), integrated discrimination improvement (IDI)

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated that higher levels of hs-cTnT and NT-proBNP were independently associated with incident ESRD in the general population. Our results are generally consistent with the previous report from TREAT in which all patients had diabetic nephropathy and anemia.17 We extended the results from TREAT in various aspects. First, we confirmed the associations of hs-cTnT and NT-proBNP with ESRD in a population with preserved kidney function, minimizing the concern for reverse causation. Second, with a more sensitive assay, we revealed significant associations between elevated hs-cTnT and ESRD even in the subclinical range associated with myocardial necrosis (i.e., 6–13 ng/L). Similarly, a risk gradient below the current clinical threshold was illustrated for NT-proBNP. Third, the significant associations among those without a history of CVD, even controlling for incident CVD during follow-up, are novel and have etiological implications.17, 27 Fourth, improved risk prediction of ESRD was confirmed for each cardiac maker. Finally, in the general population, hs-cTnT appeared to be more strongly and consistently associated with ESRD as compared to NT-proBNP.

Despite wide recognition of cardiorenal syndrome, the actual mechanisms linking cardiac abnormalities to reduced kidney function are not clearly established. Altered hemodynamics (e.g., decreased cardiac output or increased renal venous pressure) has been thought to play a pivotal role.1, 4 However, a recent study reported that hemodynamic parameters such as cardiac index and right atrial pressure did not predict worsening of kidney function in patients with heart failure.28 The RAAS is activated among those with decreased cardiac function and may play a major role in precipitating reduction in kidney function.29–31 Indeed, several trials showed that RAAS inhibitors attenuate the progression of reduced kidney function in patients with decreased cardiac function.32 The chronic activation of the sympathetic nervous system seen in heart disease also results in vasoconstriction.4 Also, treatment or procedures for those with cardiac disease such as diuretics and contrast media may contribute to reduced kidney function.1

Regarding the stronger associations of ESRD with hs-cTnT compared with NT-proBNP in our study, hs-cTnT may simply be a better marker for cardiac abnormality. However, the associations remained significant even at the subclinical level or even among those without prior CVD. cTnT is a regulatory protein in cardiac muscle and is released when cardiomyocytes are damaged.33, 34 Thus, our findings may suggest that cardiac damage (rather than cardiac overload) plays an important role in the progression of decreased kidney function. This may occur through the substances released along with cardiac damage,35 such as myoglobin, which can worsen kidney function.36 On the other hand, these findings may reflect the property of hs-cTnT as a marker of end-organ damage or systemic pathophysiological processes such as microvascular disease or endothelial dysfunction.35, 37–39 Indeed, a recent study has reported the link between high hs-cTnT and white matter lesion in the brain.38 The borderline significant interaction with gender in our study may be in line with this concept, as microvascular disease is considered to play a more key role in the pathophysiology of coronary disease in women than in men. 40–42 Nevertheless, it is not fully clear why hs-cTnT is elevated among apparently healthy individuals without cardiac manifestation, and some mechanisms other than cell damage, e.g., increased permeability, have been suggested.43 Further investigations are, therefore, warranted to elucidate mechanisms for hs-cTnT release in apparently healthy individuals and their involvement in the progression of decreased function.

The relationship between NT-proBNP and ESRD risk was not necessarily consistent across demographic groups in our study. Specifically, the relationship was significant in older individuals, females, and whites but not in their counterpart groups. This may somewhat reflect a complex property of NT-proBNP not only as a marker of cardiac overload or dysfunction44, 45 but also as an obligatory companion to BNP, a neurohormone with various beneficial effects on cardiovascular system (e.g., diuresis and inhibition of RAAS)46 and glucose metabolism (upregulation of mitochondrial biogenesis and fat oxidation and stimulation of insulin secretion).47–49 The race interaction in our study is consistent with the correlation of NT-proBNP and decreased cardiac diastolic function previously reported only in whites but not in blacks.48 Nevertheless, we need to bear in mind that, as we tested various potential interactions, our findings are rather hypothesis generating and require further investigations.

A prediction tool for ESRD has recently attracted the attention of clinicians and researchers.25 Given the medical expenditure for ESRD in developed countries,49 identification of high risk individuals and interventions (lifestyle and/or pharmacological) to slow the progression of reduced kidney function are critical. We noted that hs-cTnT and NT-proBNP improved ESRD prediction beyond known risk factors including eGFR and albuminuria. In our data, known risk factors themselves demonstrated high discrimination (C-statistic=0.884). Thus, particularly given the measurement cost, the assessment of these cardiac markers may not be recommended primarily for ESRD risk prediction. However, there would be clinical scenarios in which these cardiac markers were already measured for cardiovascular risk assessment. In these circumstances, our data suggest considering incorporation of these cardiac markers for even better ESRD prediction. Also, these cardiac markers may be useful in specific populations, among whom kidney disease measures are in a normal range or would not reflect kidney function well (e.g., glomerular hyperfiltration or heart failure). Nonetheless, future studies are needed to assess whether or how to implement these cardiac markers in ESRD risk prediction.

This study has some limitations. The number of ESRD cases was relatively small, restricting statistical power, particularly in some stratified analyses. Similarly, the number of participants with CKD was limited, and most of them were at mild stage of low eGFR and/or high albuminuria. Thus, generalization of our findings to more advanced stages needs to be done carefully. We had only single measurements of hs-cTnT and NT-proBNP, potentially resulting in some degree of misclassification due to short-term variability. However, this type of misclassification usually provides conservative estimates. We should be careful in generalizing our findings to age or racial groups not investigated in our study, particularly individuals older than 75 years, since age can impact the decision making for the initiation of kidney replacement therapy.50 Lastly, we were not able to rule out the possibility of residual confounding.

In summary, hs-cTnT and NT-proBNP levels were independently associated with incident ESRD in a general population cohort, with more evident associations for hs-cTnT than for NT-proBNP. The associations were consistent even among those with preserved kidney function and those without a history of CVD, particularly for hs-cTnT. These cardiac markers slightly improved ESRD risk prediction beyond established predictors for ESRD. These findings suggest the involvement of cardiac abnormality, particularly cardiac damage, in the progression to ESRD and/or may reflect the useful property of hs-cTnT as an end-organ damage marker.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the staff and participants of the ARIC Study for their important contributions.

Some of the data reported here have been supplied by the US Renal Data System (USRDS). The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the authors and in no way should be seen as an official policy or interpretation of the US government.

Support: The ARC Study is carried out as a collaborative study supported by National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute contracts (HHSN268201100005C, HHSN268201100006C, HHSN268201100007C, HHSN268201100008C, HHSN268201100009C, HHSN268201100010C, HHSN268201100011C, and HHSN268201100012C). Roche Diagnostics provided reagents and loan of an instrument to conduct the hs-cTnT and NT-proBNP assays and had no role in design, analysis, or manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF .le of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial Disclosure: The authors declare that they have no other relevant financial interests.

Contributions: Research idea and study design: YK, KM; data acquisition: KM, MG, RCH, CMB, JC; data analysis/interpretation: YK, KM, YS, MG, HS, AMS, RCH, SDS, CMB, JC; statistical analysis: YK, YS; supervision or mentorship: KM. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and accepts accountability for the overall work by ensuring that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. KM takes responsibility that this study has been reported honestly, accurately, and transparently; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained.

Supplementary Material

Table S1: Baseline characteristics by NT-proBNP categories.

Table S2: Correlation between hs-cTnT, NT-proBNP, eGFR, and ACR.

Table S3: Crude incidence rates of ESRD and death by hs-cTnT and NT-proBNP.

Table S4: Adjusted HR of incident ESRD using cross-categories of hs-cTnT and NT-proBNP.

Table S5: Adjusted HR of incident ESRD according to quintiles of NT-proBNP.

Table S6:. Adjusted HR of incident ESRD associated with NT-proBNP with cutoff value of 400 pg/mL.

Table S7: Adjusted HR of incident ESRD in competing-risk model.

Table S8: Adjusted HR of incident ESRD using CVD as time-varying variable without prevalent CVD at baseline.

Note: The supplementary material accompanying this article (doi:_______) is available at www.ajkd.org

REFERENCES

- 1.Ronco C, Haapio M, House AA, Anavekar N, Bellomo R. Cardiorenal syndrome. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2008 Nov 4;52(19):1527–1539. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ronco C, House AA, Haapio M. Cardiorenal and renocardiac syndromes: the need for a comprehensive classification and consensus. Nature clinical practice. Nephrology. 2008 Jun;4(6):310–311. doi: 10.1038/ncpneph0803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berl T, Henrich W. Kidney-heart interactions: epidemiology, pathogenesis, and treatment. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2006 Jan;1(1):8–18. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00730805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bock JS, Gottlieb SS. Cardiorenal syndrome: new perspectives. Circulation. 2010 Jun 15;121(23):2592–2600. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.886473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whaley-Connell A, Sowers JR. Oxidative stress in the cardiorenal metabolic syndrome. Current hypertension reports. 2012 Aug;14(4):360–365. doi: 10.1007/s11906-012-0279-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colombo PC, Ganda A, Lin J, et al. Inflammatory activation: cardiac, renal, and cardio-renal interactions in patients with the cardiorenal syndrome. Heart failure reviews. 2012 Mar;17(2):177–190. doi: 10.1007/s10741-011-9261-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muhlberger I, Monks K, Fechete R, et al. Molecular pathways and crosstalk characterizing the cardiorenal syndrome. Omics : a journal of integrative biology. 2012 Mar;16(3):105–112. doi: 10.1089/omi.2011.0121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, McCulloch CE, Hsu CY. Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. The New England journal of medicine. 2004 Sep 23;351(13):1296–1305. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harnett JD, Foley RN, Kent GM, Barre PE, Murray D, Parfrey PS. Congestive heart failure in dialysis patients: prevalence, incidence, prognosis and risk factors. Kidney international. 1995 Mar;47(3):884–890. doi: 10.1038/ki.1995.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsushita K, van der Velde M, Astor BC, et al. Association of estimated glomerular filtration rate and albuminuria with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in general population cohorts: a collaborative meta-analysis. Lancet. 2010 Jun 12;375(9731):2073–2081. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60674-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McAlister FA, Ezekowitz J, Tonelli M, Armstrong PW. Renal insufficiency and heart failure: prognostic and therapeutic implications from a prospective cohort study. Circulation. 2004 Mar 2;109(8):1004–1009. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000116764.53225.A9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paoletti E, Bellino D, Gallina AM, Amidone M, Cassottana P, Cannella G. Is left ventricular hypertrophy a powerful predictor of progression to dialysis in chronic kidney disease? Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2011 Feb;26(2):670–677. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sarnak MJ, Levey AS, Schoolwerth AC, et al. Kidney disease as a risk factor for development of cardiovascular disease: a statement from the American Heart Association Councils on Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease, High Blood Pressure Research, Clinical Cardiology, and Epidemiology and Prevention. Circulation. 2003 Oct 28;108(17):2154–2169. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000095676.90936.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weiner DE, Tighiouart H, Amin MG, et al. Chronic kidney disease as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality: a pooled analysis of community-based studies. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2004 May;15(5):1307–1315. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000123691.46138.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen SC, Su HM, Hung CC, et al. Echocardiographic parameters are independently associated with rate of renal function decline and progression to dialysis in patients with chronic kidney disease. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2011 Dec;6(12):2750–2758. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04660511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elsayed EF, Tighiouart H, Griffith J, et al. Cardiovascular disease and subsequent kidney disease. Archives of internal medicine. 2007 Jun 11;167(11):1130–1136. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.11.1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Desai AS, Toto R, Jarolim P, et al. Association between cardiac biomarkers and the development of ESRD in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, anemia, and CKD. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2011 Nov;58(5):717–728. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saunders JT, Nambi V, de Lemos JA, et al. Cardiac troponin T measured by a highly sensitive assay predicts coronary heart disease, heart failure, and mortality in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Circulation. 2011 Apr 5;123(13):1367–1376. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.005264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eriksson H, Caidahl K, Larsson B, et al. Cardiac and pulmonary causes of dyspnoea--validation of a scoring test for clinical-epidemiological use: the Study of Men Born in 1913. European heart journal. 1987 Sep;8(9):1007–1014. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a062365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Annals of internal medicine. 2009 May 5;150(9):604–612. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nephrology Iso. KDIGO 2012 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney international. 2013 Jan;3(1) doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.243. 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matsushita K, Mahmoodi BK, Woodward M, et al. Comparison of risk prediction using the CKDEPI equation and the MDRD study equation for estimated glomerular filtration rate. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2012 May 9;307(18):1941–1951. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.3954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Walraven C, Manuel DG, Knoll G. Survival trends in ESRD patients compared with the general population in the United States. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2014 Mar;63(3):491–499. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dickstein K, Cohen-Solal A, Filippatos G, et al. ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2008: the Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2008 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association of the ESC (HFA) and endorsed by the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM) European journal of heart failure. 2008 Oct;10(10):933–989. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tangri N, Stevens LA, Griffith J, et al. A predictive model for progression of chronic kidney disease to kidney failure. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2011 Apr 20;305(15):1553–1559. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fine JGR. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94:496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pfeffer MA, Burdmann EA, Chen CY, et al. A trial of darbepoetin alfa in type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease. The New England journal of medicine. 2009 Nov 19;361(21):2019–2032. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nohria A, Hasselblad V, Stebbins A, et al. Cardiorenal interactions: insights from the ESCAPE trial. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2008 Apr 1;51(13):1268–1274. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.08.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Remuzzi G, Perico N, Macia M, Ruggenenti P. The role of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in the progression of chronic kidney disease. Kidney international. Supplement. 2005 Dec;(99):S57–S65. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.09911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mezzano S, Droguett A, Burgos ME, et al. Renin-angiotensin system activation and interstitial inflammation in human diabetic nephropathy. Kidney international. Supplement. 2003 Oct;(86):S64–S70. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.64.s86.12.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Griendling KK, Minieri CA, Ollerenshaw JD, Alexander RW. Angiotensin II stimulates NADH and NADPH oxidase activity in cultured vascular smooth muscle cells. Circulation research. 1994 Jun;74(6):1141–1148. doi: 10.1161/01.res.74.6.1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stojiljkovic L, Behnia R. Role of renin angiotensin system inhibitors in cardiovascular and renal protection: a lesson from clinical trials. Current pharmaceutical design. 2007;13(13):1335–1345. doi: 10.2174/138161207780618768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Iwanaga Y, Miyazaki S. Heart failure, chronic kidney disease, and biomarkers--an integrated viewpoint. Circulation journal : official journal of the Japanese Circulation Society. 2010 Jul;74(7):1274–1282. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-10-0444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O'Brien PJ, Dameron GW, Beck ML, et al. Cardiac troponin T is a sensitive, specific biomarker of cardiac injury in laboratory animals. Laboratory animal science. 1997 Oct;47(5):486–495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peek SF, Apple FS, Murakami MA, Crump PM, Semrad SD. Cardiac isoenzymes in healthy Holstein calves and calves with experimentally induced endotoxemia. Canadian journal of veterinary research = Revue canadienne de recherche veterinaire. 2008 Jul;72(4):356–361. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bosch X, Poch E, Grau JM. Rhabdomyolysis and acute kidney injury. The New England journal of medicine. 2009 Jul 2;361(1):62–72. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0801327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Edwards MS, Wilson DB, Craven TE, et al. Associations between retinal microvascular abnormalities and declining renal function in the elderly population: the Cardiovascular Health Study. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2005 Aug;46(2):214–224. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dadu RT, Fornage M, Virani SS, et al. Cardiovascular Biomarkers and Subclinical Brain Disease in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Stroke a journal of cerebral circulation. 2013 May 9; doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.001128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rubin J, Matsushita K, Ballantyne CM, Hoogeveen R, Coresh J, Selvin E. Chronic hyperglycemia and subclinical myocardial injury. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2012 Jan 31;59(5):484–489. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.10.875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kaski JC. Overview of gender aspects of cardiac syndrome X. Cardiovascular research. 2002 Feb 15;53(3):620–626. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00460-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reis SE, Holubkov R, Conrad Smith AJ, et al. Coronary microvascular dysfunction is highly prevalent in women with chest pain in the absence of coronary artery disease: results from the NHLBI WISE study. American heart journal. 2001 May;141(5):735–741. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2001.114198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Arthur HM, Campbell P, Harvey PJ, et al. Women, cardiac syndrome X, microvascular heart disease. The Canadian journal of cardiology. 2012 Mar-Apr;28(2 Suppl):S42–S49. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kociol RD, Pang PS, Gheorghiade M, Fonarow GC, O'Connor CM, Felker GM. Troponin elevation in heart failure prevalence, mechanisms, and clinical implications. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2010 Sep 28;56(14):1071–1078. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dadu RT, Nambi V, Ballantyne CM. Developing and assessing cardiovascular biomarkers. Translational research : the journal of laboratory and clinical medicine. 2012 Apr;159(4):265–276. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2012.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nishikimi T, Maeda N, Matsuoka H. The role of natriuretic peptides in cardioprotection. Cardiovascular research. 2006 Feb 1;69(2):318–328. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nigwekar SU, Navaneethan SD, Parikh CR, Hix JK. Atrial natriuretic peptide for management of acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2009 Feb;4(2):261–272. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03780808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ropero AB, Soriano S, Tuduri E, et al. The atrial natriuretic peptide and guanylyl cyclase-A system modulates pancreatic beta-cell function. Endocrinology. 2010 Aug;151(8):3665–3674. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kapuku GK, Davis HC, Thomas P, Januzzi J, Harshfield GA. Does the relationship between natriuretic hormones and diastolic function differ by race? The American journal of the medical sciences. 2012 Aug;344(2):96–99. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e31823673fd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Services CfMaM. National Health Expenditures 2011 Highlights. 2012 http://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/Downloads/highlights.pdf.

- 50.Hemmelgarn BR, James MT, Manns BJ, et al. Rates of treated and untreated kidney failure in older vs younger adults. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2012 Jun 20;307(23):2507–2515. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.6455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.