Abstract

Study Design Retrospective cohort study.

Objective To compare the clinical and radiographic outcomes of transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (TLIF) and posterolateral lumbar fusion (PLF) in the treatment of degenerative spondylolisthesis.

Methods This study compared 24 patients undergoing TLIF and 32 patients undergoing PLF with instrumentation. The clinical outcomes were assessed by visual analog scale (VAS) for low back pain and leg pain, physical component summary (PCS) of the 12-item Short-Form Health Survey, and the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI). Radiographic parameters included slippage of the vertebra, local disk lordosis, the anterior and posterior disk height, lumbar lordosis, and pelvic parameters.

Results The improvement of VAS of leg pain was significantly greater in TLIF than in PLF unilaterally (3.4 versus 1.0; p = 0.02). The improvement of VAS of low back pain was significantly greater in TLIF than in PLF (3.8 versus 2.2; p = 0.02). However, there was no significant difference in improvement of ODI or PCS between TLIF and PLF. Reduction of slippage and the postoperative disk height was significantly greater in TLIF than in PLF. There was no significant difference in local disk lordosis, lumbar lordosis, or pelvic parameters. The fusion rate was 96% in TLIF and 84% in PLF (p = 0.3). There was no significant difference in fusion rate, estimated blood loss, adjacent segmental degeneration, or complication rate.

Conclusions TLIF was superior to PLF in reduction of slippage and restoring disk height and might provide better improvement of leg pain. However, the health-related outcomes were not significantly different between the two procedures.

Keywords: TLIF, PLF, outcome, disk height, lordosis, pelvic parameters

Introduction

Spinal fusion is an effective treatment for degenerative spondylolisthesis.1 Two of the most common surgical procedures to address this condition are posterolateral lumbar fusion (PLF) with instrumentation and transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (TLIF) with instrumentation.2 Several prior studies have compared these two procedures.2 3 4 5 Although some studies reported that interbody fusion was superior to PLF in the improvement of back pain,6 7 many other studies demonstrated that both procedures provided nearly equivalent outcomes.2 4 5

An advantage of PLF would be a simpler procedure with fewer complications. On the other hand, TLIF may provide anterior support and restore the disk height, which would lead to indirect decompression of the foraminal stenosis. There is increasing recognition of the importance of lumbar lordosis and pelvic parameters (and their restoration) in restoring the global spine balance.8 Although TLIF is believed to restore lumbar lordosis, there have been conflicting results about the effect of TLIF on the restoration of lordosis.9 10 The influence of TLIF and PLF on the pelvic parameters has rarely been compared. The purpose of this study was to compare TLIF with PLF in the treatment of degenerative spondylolisthesis using clinical and radiographic outcomes.

Methods

Objective

This was a retrospective study of patients with degenerative spondylolisthesis treated by three spine surgeons in a single spine center during the years from 2006 to 2011. The choice of surgical technique (TLIF or PLF) was based on the surgeon's preference. The inclusion criteria were: (1) diagnosis of degenerative spondylolisthesis refractory to conservative management; (2) planned one- or two-level instrumented fusion; (3) pre- and postoperative visual analog scale; (4) radiographs; (5) pre- and postoperative 12-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-12); and (6) a minimum follow-up period of 1 year. All the outcomes were measured at the final follow-up period. The visual analog scale of leg pain was measured on the right and left side, regardless of the surgical side. We excluded patients who had had prior fusion surgery. Our institutional review board approved this study.

Operative Techniques

Patients were positioned prone on a Jackson table. The posterior spinal elements were exposed using a standard subperiosteal dissection. A laminectomy was performed bilaterally for PLF. Bone grafts were harvested from iliac crest and/or local bone and supplemented with fresh frozen allograft. The pedicle screw fixation was performed with bone grafting. In cases of TLIF, only a unilateral facetectomy for the symptomatic side was generally performed. A diskectomy was then performed using a curette and rongeurs, and an interbody cage with bone graft was inserted. The pedicle screw fixation was performed with bone grafting to the residual posterior elements. Bone grafts were harvested from iliac crest and/or local bone and supplemented with fresh frozen allograft.

Radiographic Parameters

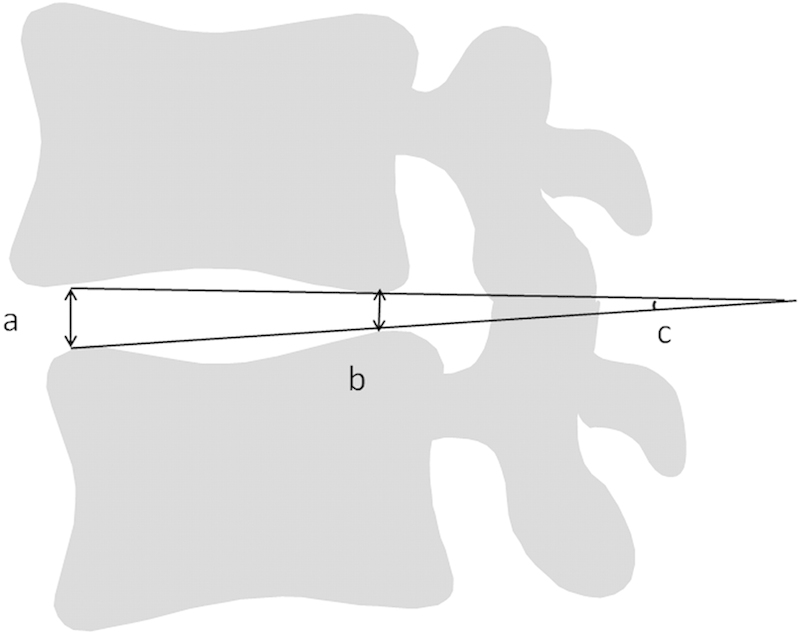

Radiographic parameters of interest included (1) slippage of the vertebra; (2) local disk lordosis; (3) anterior and posterior disk height; (4) lumbar lordosis: T12–S1 angle; (5) pelvic parameters: sacral slope, pelvic tilt, and pelvic incidence (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Radiographic parameters: (a) anterior disk height, (b) posterior disk height, (c) local disk lordosis.

Local disk lordosis and the disk height were measured at L4/L5 level if two levels were included in the fusion area. Adjacent segmental degeneration (ASD) was evaluated at the proximal segment next to the upper instrumented vertebra. ASD was graded into four categories based on the University of California, Los Angeles grading scale for intervertebral space degeneration (Table 1).11

Table 1. Grading scale for intervertebral disk degeneration11 .

| Disk space narrowing | Osteophytes | End plate sclerosis | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | − | − | − |

| 2 | + | − | − |

| 3 | +/− | +/− | − |

| 4 | +/− | +/− | + |

Note: Grade is based on the most severe radiographic finding. Patients were graded based on the worst category satisfied.

Radiographic fusion was determined by the posteroanterior and lateral radiographs (Fig. 2). PLF fusion was defined as a solid, large fusion mass, at least unilaterally, with a smaller fusion mass on the contralateral side on the posteroanterior radiograph without loosening of the pedicle screws on the lateral radiograph.12 TLIF fusion was defined as cases that met the PLF fusion criteria and had osseous continuity between the graft bone and the vertebra on the posteroanterior radiograph without loosening of the pedicle screws on the lateral radiograph.13 Pseudarthrosis was defined as those cases that did not meet the fusion criteria. Assessment was performed at the final visit using radiographs.

Fig. 2.

(Left) Posterolateral fusion. (Right) Transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion.

All radiographic parameters were assessed by a digital viewer, Surgimap Spine (Nemaris, Inc., New York, New York, United States; http://www.surgimapspine.com/).

Statistical Analysis

The t test was used to compare clinical and radiographic parameters between the two groups. The chi-square test was used to compare the categorical data. A p value less than 0.05 with the two-tailed test was considered statistically significant. A logistic regression analysis was performed defining fusion status as the dependent variable. The independent variables included type of bone graft, number of fusion levels, type of surgery, radiographic loosening of pedicle screws, and age. The statistical analysis was performed with SPSS Statistics (version 20; IBM, Armonk, New York, United States).

Results

Patient Demographics

The patient demographics are shown in Table 2. The TLIF group was comprised of 6 men and 18 women with a mean age of 59 ± 14 years. The mean follow-up period was 1.8 ± 1.3 years, and there were 29 total fusion levels. In the PLF group, there were 11 men and 21 women with a mean age of 61 ± 11 years. The mean follow-up period was 2.0 ± 1.0 years, and there were 51 total fusion levels. There were no significant differences in age, gender, follow-up period, body mass index, diabetes, or smoking status between the PLF and TLIF groups.

Table 2. Demographics and operative data.

| Demographic data | TLIF (n = 24) | PLF (n = 32) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 59 ± 14 | 61 ± 11 | 0.5 |

| Gender (male/female) | 6/18 | 11/21 | 0.6 |

| Follow-up (y) | 1.8 ± 1.3 | 2.0 ± 1.0 | 0.5 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.3 ± 5.8 | 25.8 ± 6.3 | 0.6 |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 8.3 | 9.4 | 0.9 |

| Smoking (%) | 12.5 | 9.4 | 0.7 |

| 1 level/2 levels | 19/5 | 13/19 | |

| Fusion level | |||

| L3/L4 | 4 | 8 | |

| L4/L5 | 19 | 30 | |

| L5/S1 | 6 | 13 | |

| Bone graft (iliac/local) | 7/17 | 16/16 | 0.2 |

| Estimated blood loss (mL) | 368 ± 225 | 368 ± 156 | >0.99 |

| Surgical time (min) | 165 ± 62 | 151 ± 57 | 0.8 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; PLF, posterolateral lumbar fusion; TLIF, transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion.

Note: Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

Clinical Outcomes

Visual Analog Scale

There were no significant differences in preoperative leg pain or low back pain between the TLIF and PLF groups (Table 3). The improvement in the low back pain was significantly greater in the TLIF group compared with the PLF group (TLIF 38 ± 27 versus PLF 22 ± 31; p = 0.03). The improvement in the left leg pain was significantly greater in the TLIF group than in the PLF group (TLIF 34 ± 42 versus PLF 10 ± 35; p = 0.03).There was no significant difference in the improvement in the right leg pain between the TLIF group and the PLF group (TLIF 31 ± 48 versus PLF 22 ± 42; p = 0.4). . The leg pain was improved on the decompression side.

Table 3. Comparison of clinical outcomes.

| TLIF (n = 24) | PLF (n = 32) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| VAS low back pain | |||

| Pre | 69 ± 28 | 63 ± 25 | 0.4 |

| Post | 31 ± 23 | 41 ± 27 | 0.2 |

| Change | −38 ± 27 | −22 ± 31 | 0.03a |

| VAS left leg pain | |||

| Pre | 45 ± 40 | 31 ± 32 | 0.2 |

| Post | 12 ± 25 | 21 ± 28 | 0.1 |

| Change | −34 ± 42 | −10 ± 35 | 0.03a |

| VAS right leg pain | |||

| Pre | 58 ± 35 | 43 ± 33 | 0.1 |

| Post | 27 ± 35 | 22 ± 29 | 0.8 |

| Change | −31 ± 48 | −22 ± 42 | 0.4 |

| ODI | |||

| Pre | 49 ± 15 | 48 ± 13 | 0.9 |

| Post | 34 ± 22 | 34 ± 18 | 0.7 |

| Change | −15 ± 19 | −14 ± 15 | 0.8 |

| SF-12 PCS | |||

| Pre | 33 ± 6 | 28 ± 9 | 0.03a |

| Post | 39 ± 10 | 34 ± 10 | 0.06 |

| Change | 6 ± 9 | 7 ± 9 | 0.7 |

| SF-12 MCS | |||

| Pre | 41 ± 17 | 40 ± 14 | 0.8 |

| Post | 46 ± 14 | 47 ± 14 | 0.9 |

| Change | 6 ± 18 | 5 ± 16 | 0.6 |

Abbreviations: ODI, Oswestry Disability Index; MCS, mental component summary; PCS, physical component summary; PLF, posterolateral lumbar fusion; Pre, preoperative; Post, postoperative; SF-12, Short Form-12; TLIF, transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion; VAS, visual analog scale.

p < 0.05.

Health-Related Outcomes

The preoperative Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) was 49 ± 15 in the TLIF group and 48 ± 13 in the PLF group (p = 0.9). The postoperative ODI was 34 ± 22 in the TLIF group and 34 ± 18 in the PLF group (p = 0.7). There was no significant difference in the ODI improvement between the groups (TLIF: 15 ± 19 versus PLF: 14 ± 15; p = 0.8).

The preoperative physical component summary (PCS) of the SF-12 was 33 ± 6 in the TLIF group and 28 ± 9 in the PLF group (p = 0.03). The postoperative PCS was 39 ± 10 in TLIF group and 34 ± 10 in PLF group (p = 0.06). There was no significant difference in PCS improvement between the groups (TLIF: 6 ± 9 versus PLF: 7 ± 9; p = 0.7).

Radiographic Parameters

Local Measurement

The radiographic parameters are shown in Table 4. The preoperative slippage was 5.3 ± 2.9 mm in the TLIF group and 5.2 ± 3.5 mm in the PLF group (p = 0.9). The postoperative slippage was 1.7 ± 2.3 mm in the TLIF group and 4.1 ± 3.1 mm in the PLF group (p = 0.003). The reduction in slippage was significantly greater in the TLIF group (−3.6 ± 3.0 mm) compared with the PLF group (−1.1 ± 2.9 mm; p = 0.006).

Table 4. Comparison of radiographic parameters.

| TLIF (n = 24) | PLF (n = 32) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Slippage (mm) | |||

| Pre | 5.3 ± 2.9 | 5.2 ± 3.5 | 0.9 |

| Post | 1.7 ± 2.3 | 4.1 ± 3.1 | 0.003a |

| Change | −3.6 ± 3.0 | −1.1 ± 2.9 | 0.006a |

| Local disk lordosis (degrees) | |||

| Pre | 6.0 ± 4.3 | 4.2 ± 3.5 | 0.2 |

| Post | 6.0 ± 3.9 | 4.5 ± 2.6 | 0.2 |

| Change | 0.1 ± 3.3 | 0.3 ± 2.9 | 0.9 |

| Anterior disk height (mm) | |||

| Pre | 10 ± 2.9 | 8.7 ± 2.5 | 0.1 |

| Post | 11 ± 2.2 | 8.6 ± 2.7 | 0.001a |

| Change | 1.4 ± 1.8 | 0.0 ± 1.7 | 0.008a |

| Posterior disk height (mm) | |||

| Pre | 6.0 ± 1.6 | 5.8 ± 1.5 | 0.7 |

| Post | 7.3 ± 1.3 | 5.7 ± 1.4 | 0.001a |

| Change | 1.2 ± 1.5 | 0 ± 1.5 | 0.01a |

| Lumbar lordosis (degrees) | |||

| Pre | 50 ± 14 | 51 ± 13 | 0.6 |

| Post | 52 ± 12 | 52 ± 12 | 0.9 |

| Change | 1 ± 10 | 1 ± 8 | 0.7 |

| Sacral slope (degrees) | |||

| Pre | 33 ± 10 | 36 ± 7 | 0.2 |

| Post | 35 ± 8 | 35 ± 7 | 0.9 |

| Change | 2 ± 6 | −1 ± 6 | 0.2 |

| Pelvic tilt (degrees) | |||

| Pre | 20 ± 9 | 19 ± 6 | 0.6 |

| Post | 19 ± 10 | 18 ± 7 | 0.9 |

| Change | −1 ± 8 | 0 ± 5 | 0.3 |

| Pelvic incidence (degrees) | |||

| Pre | 53 ± 9 | 54 ± 8 | 0.4 |

Abbreviations: PLF, posterolateral lumbar fusion; Pre, preoperative; Post, postoperative; TLIF, transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion.

Note: Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

p < 0.05.

The preoperative local disk lordosis was 6.0 ± 4.3 degrees in the TLIF group and 4.2 ± 3.5 degrees in the PLF group (p = 0.2). The postoperative local disk lordosis was 6.0 ± 3.9 degrees in the TLIF group and 4.5 ± 2.6 degrees in the PLF group (p = 0.2). There was no significant difference in the change of local disk lordosis between the groups (TLIF: 0.1 ± 3.3 degrees versus PLF: 0.3 ± 2.9 degrees; p = 0.9). The change in anterior and posterior disk height was significantly greater in the TLIF group (anterior: 1.4 ± 1.8 mm and posterior: 1.2 ± 1.5 mm) compared with the PLF group (anterior: 0 ± 1.7 mm and posterior: 0 ± 1.5 mm; p < 0.01).

Lumbar Lordosis and Pelvic Parameters

The preoperative lumbar lordosis was 50 ± 14 degrees in the TLIF group and 51 ± 13 degrees in the PLF group (p = 0.6). The postoperative lumbar lordosis was 52 ± 12 degrees in both groups (p = 0.9). There was no significant difference in the change in lumbar lordosis (TLIF: 1 ± 10 degrees versus PLF: 1 ± 8 degrees; p = 0.9).

The preoperative sacral slope was 33 ± 10 degrees in the TLIF group and 36 ± 7 degrees in the PLF group (p = 0.2). The postoperative sacral slope was 35 ± 8 degrees in the TLIF group and 35 ± 7 degrees in the PLF group (p = 0.9). There was no significant difference in the change in sacral slope between the groups (TLIF: 2 ± 6 degrees versus PLF: −1 ± 6 degrees; p = 0.9).

The preoperative pelvic tilt was 20 ± 9 degrees in the TLIF group and 19 ± 6 degrees in the PLF group (p = 0.6). The postoperative pelvic tilt was 19 ± 10 degrees in the TLIF group and18 ± 7 degrees in the PLF group (p = 0.9). There was no significant differences in the change in pelvic tilt between the groups (TLIF: −1 ± 8 degrees versus PLF: 0 ± 5 degrees; p = 0.3).

There was no significant difference in pelvic incidence between the groups (TLIF: 53 ± 9 degrees versus PLF: 54 ± 8 degrees; p = 0.4).

Union Rate and Adjacent Segmental Degeneration

There were 5 patients with pseudarthrosis in the PLF group and 1 patient with pseudarthrosis in the TLIF group (Table 5). Thus, the fusion rate was 84% in the PLF group and 96% in the TLIF group (p = 0.3).

Table 5. Complications.

| TLIF (n = 24) | PLF (n = 32) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fusion rate (%) | 96 | 84 | 0.2 |

| Adjacent segmental degeneration | 1.1 ± 0.4 | 1.3 ± 0.8 | 0.3 |

| Dural tear (case/%) | 1/4 | 4/12.5 | 0.3 |

| Infection | 0 | 0 | >0.99 |

Abbreviations: PLF, posterolateral lumbar fusion; TLIF, transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion.

The adjacent segmental degeneration grading score was 1.3 in the PLF group and 1.1 in the TLIF group (p = 0.3). The logistic regression analysis demonstrated that loosening of the pedicle screw was significantly associated with the fusion status (p < 0.01). However, the other parameters were not significantly associated with the fusion status.

Complications

The estimated blood loss was nearly equivalent for both procedures (TLIF: 368 ± 194 mL versus PLF: 368 ± 131 mL; p > 0.99). There were 1 case (4%) with dural tear in the TLIF group and 4 cases (12.5%) with dural tear in the PLF group (p = 0.3). One case in the PLF group underwent revision surgery due to contralateral leg pain.

Discussion

In the present study, the TLIF group had significantly greater improvement in the left leg pain and in low back pain compared with the PLF group. However, the other health-related outcomes demonstrated nearly equivalent improvement, and the right leg pain scale was not significantly different. The radiographic parameters of reduction of slippage, postoperative disk height, and change in the disk height were significantly greater in the TLIF group. Other radiographic parameters, including local disk lordosis, lumbar lordosis, and pelvic parameters, showed similar results between the study groups.

Only one randomized study has reported that the use of additional interbody fusion (circumferential fusion) in the treatment of various lumbar degenerative diseases showed significantly greater improvement in the health-related outcomes (Table 6).6 Although this interbody fusion was combined with PLF and anterior lumbar interbody fusion (ALIF), Videbaek et al reported that circumstantial fusion had significantly greater improvement in ODI, PCS, and low back pain scale.6

Table 6. Review of previous studies.

| Author | Design | Diagnosis | Comparison | Leg pain | Low back pain | ODI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fritzell et al4 | RCT | Chronic LBP | PLF versus circumferential fusion (PLF + ALIF or TLIF) | NS | NS | NS |

| Videbaek et al6 | RCT | Heterogeneous population with chronic LBP | PLF versus circumferential fusion (PLF + ALIF) | NS | Significantly better in circumferential fusion | Significantly better in circumferential fusion |

| Abdu et al2 | Retrospective | Degenerative spondylolisthesis | PLF versus circumferential fusion (PLF + ALIF or TLIF) | NA | NA | NS |

| Høy et al5 | RCT | Heterogeneous population with chronic LBP | PLF versus TLIF | NS | NS | NS |

| Present study | Retrospective | Degenerative spondylolisthesis | PLF versus TLIF | Significantly better in TLIF | Significantly better in TLIF | NS |

Abbreviations: ALIF, anterior lumbar interbody fusion; LBP, low back pain; NA, not available; NS, no significant difference; ODI, Oswestry Disability Index; PLF, posterolateral fusion, RCT, randomized control study; TLIF, transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion.

Other studies reported nearly equivalent outcomes between TLIF and PLF. The Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial reported that surgical treatment for degenerative spondylolisthesis provided substantially greater improvement in pain and function than conservative therapy alone.1 However, the choice of fusion procedure (which included PLF with or without pedicle screws and PLF with interbody fusion) did not change the outcome.2 A randomized study from the Swedish Lumbar Spine Group concerning degenerative low back pain compared PLF, PLF with pedicle screws, and PLF with interbody fusion.4 In their study, the clinical outcomes were similar between the three groups. More recently, Høy et al performed a randomized controlled study comparing TLIF with instrumented PLF for various degenerative lumbar disorders.5 They found no difference in improvement of low back pain, leg pain, ODI, or Short Form-36 score between TLIF and instrumented PLF. However, Høy et al mentioned that their patients were a heterogeneous population and this may have blurred their results. Kim et al randomly compared PLF, PLIF, and PLIF with PLF for various degenerative lumbar diseases.14 They found no significant differences in the clinical results and union rates between the three fusion methods. However, they did report that PLIF without iliac bone graft had the advantage of elimination of the donor site pain.

Slippage reduction and postoperative local disk height were significantly greater in the TLIF group. The necessity of reducing slippage for spondylolisthesis has been a controversial issue.15 16 However, many studies have reported that a reduction in slippage was not associated with a better outcome, especially for degenerative spondylolisthesis.17 18

Several groups have reported on the effect of interbody fusion on the lumbar lordosis.9 19 20 21 Hsieh et al reported a limited increase in lumbar lordosis treated by TLIF compared with ALIF.9 They reported that TLIF decreased local disk lordosis by 0.1 degrees and lumbar lordosis by 2.1 degrees. Dorward et al compared TLIF with ALIF for the treatment of long deformity constructs.21 They reported that TLIF decreased local disk lordosis by 1.7 degrees at L4/L5 and by 1.4 degrees at L5/S1. However, both studies mentioned that facetectomy was performed only unilaterally for TLIF. On the other hand, Yson et al reported that TLIF with bilateral facetectomy increased local disk lordosis by 7.2 degrees.22 Jagannathan et al reported that TLIF with bilateral facetectomy increased local disk lordosis by 20 degrees.10

Biomechanically, the anterior placement of the interbody cage away from the instant axis of rotation has the advantage of maximizing local disk lordosis if it acts as a fulcrum.22 However, the anterior placement of the interbody cage to maximize lordosis requires the compression of the posterior elements. Faundez et al reported that the anterior placement of the cage alone could not increase local disk lordosis.23 Compression across the posterior elements potentially decreases the posterior disk height at the fusion site and may lead to foraminal stenosis. Actually, no study has demonstrated a simultaneous increase in both local disk lordosis as well as posterior disk height. If posterior compression is performed to maximize local disk lordosis, surgeons need to prevent the caudal nerve root impingement from the residual superior articular process. Jagannathan et al reported that they performed pedicle-to-pedicle decompression with complete bilateral facetectomies to achieve the maximum lordosis.10 In the present study, we generally used box-shaped cages and performed unilateral facetectomy. Thus, the disk height increased anteriorly and posteriorly, but the increases in local disk lordosis and lumbar lordosis were limited. However, it is technically demanding to insert a wedged high cage into a narrowed disk space. A newly invented expandable TLIF cage might be a future option to simultaneously gain lordosis and disk height.24

Few studies have reported the influence of TLIF and PLF on pelvic parameters. Ould-Slimane et al reported that single-level TLIF increased lumbar lordosis by 9.3 degrees and decreased pelvic tilt by 5.8 degrees.25 In the present study, the pelvic parameters showed little change due to a limited increase in lumbar lordosis.

Our study had several limitations including its retrospective, nonrandomized design. In addition, there was a possibility of selection bias as the surgeons tended to choose TLIF for patients who were likely to have foraminal stenosis.

Our results correlated with many previous studies in that postoperative health-related outcomes did not differ significantly between TLIF and PLF groups. However, the visual analog scale in the left leg was significantly improved in the PLF group compared with the TLIF group. This might be due to the indirect decompression effect of the caudal nerve root by restoration of the disk height at the surgical site.26

The proposed advantages of TLIF over PLF, including the reduction in slippage, restoration of disk height, greater lumbar lordosis, and higher union rate, might be expected to result in the improved pain scores. However, such improvement failed to demonstrate significant differences in health-related outcomes.

Conclusion

The TLIF group demonstrated significantly greater improvement in low back pain and unilateral leg pain compared with the PLF group. However, no differences in improvement in either ODI or PCS were noted between the groups. The postoperative slippage and disk height were significantly greater in the TLIF group, but local disk lordosis, lumbar lordosis, and pelvic parameters were similar between the groups.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Linda Racine, CCRP, for helping with data collection and Takenori Oda for their critical advice.

Footnotes

Disclosures Takahito Fujimori, none Hai Le, none William W. Schairer, none Sigurd H. Berven, Board membership: Globus; Consultant: Medtronic; Royalties: Medtronic; Stock/stock options: Co-Align, Simpirica, Providence Medical Erion Qamirani, none Serena S. Hu, Consultant: Medtronic, NuVasive

References

- 1.Weinstein J N, Lurie J D, Tosteson T D. et al. Surgical versus nonsurgical treatment for lumbar degenerative spondylolisthesis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(22):2257–2270. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abdu W A, Lurie J D, Spratt K F. et al. Degenerative spondylolisthesis: does fusion method influence outcome? Four-year results of the spine patient outcomes research trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2009;34(21):2351–2360. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181b8a829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Faundez A A, Schwender J D, Safriel Y. et al. Clinical and radiological outcome of anterior-posterior fusion versus transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion for symptomatic disc degeneration: a retrospective comparative study of 133 patients. Eur Spine J. 2009;18(2):203–211. doi: 10.1007/s00586-008-0845-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fritzell P Hägg O Wessberg P Nordwall A; Swedish Lumbar Spine Study Group. Chronic low back pain and fusion: a comparison of three surgical techniques: a prospective multicenter randomized study from the Swedish lumbar spine study group Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 200227111131–1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Høy K, Bünger C, Niederman B. et al. Transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (TLIF) versus posterolateral instrumented fusion (PLF) in degenerative lumbar disorders: a randomized clinical trial with 2-year follow-up. Eur Spine J. 2013;22(9):2022–2029. doi: 10.1007/s00586-013-2760-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Videbaek T S, Christensen F B, Soegaard R. et al. Circumferential fusion improves outcome in comparison with instrumented posterolateral fusion: long-term results of a randomized clinical trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2006;31(25):2875–2880. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000247793.99827.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christensen F B, Hansen E S, Eiskjaer S P. et al. Circumferential lumbar spinal fusion with Brantigan cage versus posterolateral fusion with titanium Cotrel-Dubousset instrumentation: a prospective, randomized clinical study of 146 patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2002;27(23):2674–2683. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200212010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glassman S D, Bridwell K, Dimar J R, Horton W, Berven S, Schwab F. The impact of positive sagittal balance in adult spinal deformity. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005;30(18):2024–2029. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000179086.30449.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hsieh P C, Koski T R, O'Shaughnessy B A. et al. Anterior lumbar interbody fusion in comparison with transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion: implications for the restoration of foraminal height, local disc angle, lumbar lordosis, and sagittal balance. J Neurosurg Spine. 2007;7(4):379–386. doi: 10.3171/SPI-07/10/379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jagannathan J, Sansur C A, Oskouian R J Jr, Fu K M, Shaffrey C I. Radiographic restoration of lumbar alignment after transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion. Neurosurgery. 2009;64(5):955–963, discussion 963–964. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000343544.77456.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghiselli G, Wang J C, Hsu W K, Dawson E G. L5–S1 segment survivorship and clinical outcome analysis after L4–L5 isolated fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2003;28(12):1275–1280, discussion 1280. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000065566.24152.D3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lenke L G, Bridwell K H, Bullis D, Betz R R, Baldus C, Schoenecker P L. Results of in situ fusion for isthmic spondylolisthesis. J Spinal Disord. 1992;5(4):433–442. doi: 10.1097/00002517-199212000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bridwell K H, Lenke L G, McEnery K W, Baldus C, Blanke K. Anterior fresh frozen structural allografts in the thoracic and lumbar spine. Do they work if combined with posterior fusion and instrumentation in adult patients with kyphosis or anterior column defects? Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1995;20(12):1410–1418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim K T, Lee S H, Lee Y H, Bae S C, Suk K S. Clinical outcomes of 3 fusion methods through the posterior approach in the lumbar spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2006;31(12):1351–1357, discussion 1358. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000218635.14571.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Longo U G, Loppini M, Romeo G, Maffulli N, Denaro V. Evidence-based surgical management of spondylolisthesis: reduction or arthrodesis in situ. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(1):53–58. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.01012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacobs W C, Vreeling A, De Kleuver M. Fusion for low-grade adult isthmic spondylolisthesis: a systematic review of the literature. Eur Spine J. 2006;15(4):391–402. doi: 10.1007/s00586-005-1021-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lian X F, Hou T S, Xu J G. et al. Posterior lumbar interbody fusion for aged patients with degenerative spondylolisthesis: is intentional surgical reduction essential? Spine J. 2013;13(10):1183–1189. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2013.07.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Audat Z M, Darwish F T, Al Barbarawi M M. et al. Surgical management of low grade isthmic spondylolisthesis; a randomized controlled study of the surgical fixation with and without reduction. Scoliosis. 2011;6(1):14. doi: 10.1186/1748-7161-6-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Diedrich O, Perlick L, Schmitt O, Kraft C N. Radiographic spinal profile changes induced by cage design after posterior lumbar interbody fusion preliminary report of a study with wedged implants. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2001;26(12):E274–E280. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200106150-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gödde S, Fritsch E, Dienst M, Kohn D. Influence of cage geometry on sagittal alignment in instrumented posterior lumbar interbody fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2003;28(15):1693–1699. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000083167.78853.D5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dorward I G, Lenke L G, Bridwell K H. et al. Transforaminal versus anterior lumbar interbody fusion in long deformity constructs: a matched cohort analysis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2013;38(12):E755–E762. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31828d6ca3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yson S C, Santos E R, Sembrano J N, Polly D W Jr. Segmental lumbar sagittal correction after bilateral transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion. J Neurosurg Spine. 2012;17(1):37–42. doi: 10.3171/2012.4.SPINE111013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Faundez A A, Mehbod A A, Wu C, Wu W, Ploumis A, Transfeldt E E. Position of interbody spacer in transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion: effect on 3-dimensional stability and sagittal lumbar contour. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2008;21(3):175–180. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0b013e318074bb7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qandah N Klocke N Synkowski J et al. Additional Sagittal Correction Can be Obtained When Using an Expandable Titanium Interbody Device in Lumbar Smith-Peterson Osteotomies: A Biomechanical Study Spine J 2014; October 11 (Epub ahead of print); doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2014.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ould-Slimane M, Lenoir T, Dauzac C. et al. Influence of transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion procedures on spinal and pelvic parameters of sagittal balance. Eur Spine J. 2012;21(6):1200–1206. doi: 10.1007/s00586-011-2124-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McAfee P C DeVine J G Chaput C D et al. The indications for interbody fusion cages in the treatment of spondylolisthesis: analysis of 120 cases Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 200530(6, Suppl):S60–S65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]