Abstract

Background and Purpose

Hydrogen sulphide (H2S) is a gaseous mediator strongly involved in cardiovascular homeostasis, where it provokes vasodilatation. Having previously shown that H2S contributes to testosterone-induced vasorelaxation, here we aim to uncover the mechanisms underlying this effect.

Experimental Approach

H2S biosynthesis was evaluated in rat isolated aortic rings following androgen receptor (NR3C4) stimulation. Co-immunoprecipitation and surface plasmon resonance analysis were performed to investigate mechanisms involved in NR3C4 activation.

Key Results

Pretreatment with NR3C4 antagonist nilutamide prevented testosterone-induced increase in H2S and reduced its vasodilator effect. Androgen agonist mesterolone also increased H2S and induced vasodilatation; effects attenuated by the selective cystathionine-γ lyase (CSE) inhibitor propargylglycine. The NR3C4-multicomplex-derived heat shock protein 90 (hsp90) was also involved in this effect; its specific inhibitor geldanamycin strongly reduced testosterone-induced H2S production. Neither progesterone nor 17-β-oestradiol induced H2S release. Furthermore, we demonstrated that CSE, the main vascular H2S-synthesizing enzyme, is physically associated with the NR3C4/hsp90 complex and the generation of such a ternary system represents a key event leading to CSE activation. Finally, H2S levels in human blood collected from male healthy volunteers were higher than those in female samples.

Conclusions and Implications

We demonstrated that selective activation of the NR3C4 is essential for H2S biosynthesis within vascular tissue, and this event is based on the formation of a ternary complex between cystathionine-γ lyase, NR3C4and hsp90. This novel molecular mechanism operating in the vasculature, corroborated by higher H2S levels in males, suggests that the L-cysteine/CSE/H2S pathway may be preferentially activated in males leading to gender-specific H2S biosynthesis.

Linked Articles

This article is part of a themed section on Pharmacology of the Gasotransmitters. To view the other articles in this section visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/bph.2015.172.issue-6

Keywords: androgen receptor, heat shock protein 90, hydrogen sulphide, testosterone, vascular function

Introduction

Since the 1980s, epidemiological and clinical studies have demonstrated a distinct sexual dimorphism in cardiovascular function, which appears more evident in the presence of pathological conditions. Several studies have shown that males are more susceptible to coronary artery disease and hypertension (Levy and Kannel, 1988; Adams et al., 1995) than age-matched premenopausal women. This has led to a dogmatic view of the androgen hormone testosterone as a risk factor affecting cardiovascular system homeostasis (Herman et al., 1997; Reckelhoff et al., 1998). Recently, this view has been amended. In fact, both clinical (Hu et al., 2012; Papierska et al., 2012; Soisson et al., 2012) and experimental studies (Liu et al., 2003; Wu and von Eckardstein, 2003; Deenadayalu et al., 2012) have demonstrated acute and chronic protective effects of androgens on both cardiovascular and metabolic functions; these include their crucial role in anabolic processes and sexual development, which occur through genome-based mechanisms (Mooradian et al., 1987; Bhasin et al., 1996). Nevertheless, testosterone has also been shown to trigger rapid non-genomic events such as vasodilatation; this has been shown to occur in a variety of large vessels (aorta, coronary arteries) as well as in small resistance arteries (mesenteric, prostatic, pulmonary) both in humans and various animal species (Deenadayalu et al., 2001; Malkin et al., 2006; Perusquia et al., 2007; Yang et al., 2008; Bucci et al., 2009; Nettleship et al., 2009; Traish et al., 2009). We have recently demonstrated that hydrogen sulphide (H2S) contributes to testosterone-induced vasodilatation in aortic tissue, highlighting a link between H2S release and the non-genomic vasodilator effect of testosterone (Bucci et al., 2009). H2S is endogenously formed in mammalian cells from L-cysteine through the action of cystathionine-β synthase and cystathionine-γ lyase (CSE), both pyridoxal-5′-phosphate hydrate (PP)- dependent enzymes. Alternatively, these enzymes can also utilize L-methionine and/or homocysteine as substrates to produce H2S (Stipanuk, 2004). In addition, 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase represents another source of H2S production (Shibuya et al., 2009). Within the cardiovascular network, H2S is mainly produced from L-cysteine by CSE (Lu et al., 1992; Levonen et al., 2000; Fusco et al., 2012) and, given its vasorelaxant properties, it is involved in the control of blood pressure, although this is still debatable (Yang et al., 2008; Ishii et al., 2010).

Up-to-date literature regarding the effects of androgen hormones in the vascular system is, at present, sparse compared to the much more consistent data on the beneficial effects of oestrogens, as reviewed in Arnal et al. (2010) and Leung et al. (2007). These beneficial effects of oestrogens result from different mechanisms that range from their favourable modulation of serum lipoprotein profile (Stampfer et al., 1991; Ettinger et al., 1996; Farish et al., 1996) to their antioxidant properties (Keaney et al., 1994; Huang et al., 1999), and also include a direct action on the vasculature. Although oestrogen-induced endothelial NO release is a well-established concept, much less is known about the molecular mechanism through which testosterone triggers H2S biosynthesis (Haynes et al., 2000; Bucci et al., 2002; 2009; Perusquia et al., 2007; Cutini et al., 2009). The aim of this study was to gain further insights into the molecular mechanism of H2S release induced by testosterone in the vasculature.

Methods

Animals

Male Wistar rats (8 weeks of age) were purchased from Harlan (Udine, Italy) and kept in animal care facility under controlled temperature, humidity and light/dark cycle and with food and water ad libitum. All animal procedures were performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki (European Union guidelines on use of animals in scientific experiments), followed ARRIVE guidelines and were approved by our local animal care office (Centro Servizi Veterinari Università degli Studi di Napoli ‘Federico II’). All studies involving animals are reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals (Kilkenny et al., 2010; McGrath et al., 2010).

Tissue preparation

Male Wistar rats (Harlan) weighing 300–350 g were anaesthetized with enflurane (5%) and then killed in CO2 chamber (70%); the thoracic aorta was rapidly isolated, dissected and adherent connective and fat tissues were removed. Rings of 2–3 mm in length were cut and placed in organ baths (3.0 mL) filled with oxygenated (95% O2–5% CO2) Krebs solution and kept at 37°C. The rings were connected to an isometric transducer (type 7006; Ugo Basile, Comerio, Italy), and changes in tension were continuously recorded with a computerized system (DataCapsule-17400; UgoBasile). The composition of the Krebs solution was as follows (mM): NaCl 118, KCl 4.7, MgCl2 1.2, KH2PO4 1.2, CaCl2 2.5, NaHCO3 25 and glucose 10.1. The rings were initially stretched until a resting tension of 0.5 g was reached and allowed to equilibrate for at least 30 min; during this period tension was adjusted, when necessary, to 0.5 g and bathing solution was periodically changed.

Experimental protocol

In each set of experiments, rings were firstly challenged with phenylephrine (PE; 1 μM) until the responses were reproducible. In order to verify the integrity of the endothelium, a cumulative concentration–response curve to ACh (10 nM–30 μM) was performed on PE pre-contracted rings. Tissues were then washed and contracted with PE (1 μM) and, once the plateau was reached, a cumulative concentration–response curve for the following drugs was performed: testosterone (T; 10 nM–30 μM), stanozolol (ST; 10 nM–30 μM), mesterolone (Mes; 10 nM–30 μM), progesterone (Prog; 10 nM–300 μM) and 17-β-oestradiol (E2; 10 nM–30 μM). All androgen and oestrogen hormones described above were used at pharmacological (low micromolar range), rather than endogenous (low nanomolar range) concentrations, as used previously in isolated organ bath procedures (Crews and Khalil, 1999; Tep-areenan et al., 2002).

Drug treatments

Nilutamide (Nil; 10 μM) or geldanamycin (GA; 20 μM), androgen receptor (NR3C4; for receptor nomenclature see Alexander et al., 2013) and heat shock protein 90 (hsp90) antagonists, respectively, were added in the organ baths. After 15 min rings were contracted with PE (1 μM) and a testosterone cumulative concentration–response curve performed. In another set of experiments, CSE inhibitor propargylglycine (PAG; 10 mM) was added in the organ baths and after 15 min rings were contracted with PE (1 μM); Mes, Prog or E2 were administered to obtain a cumulative concentration–response curves, which gave maximal relaxant effect within 30 min. Drug addition and incubation times selected did not affect PE-induced contraction (data not shown).

H2S assay

H2S determination was performed using a methylene blue-based assay (Stipanuk and Beck, 1982; Fusco et al., 2012). Briefly, the thoracic aorta was dissected, placed in sterile PBS and cleaned of fat and connective tissue. Rings, of the same size as described above, were cut and placed in 24-well plates pre-filled with 990 μL Krebs solution and equilibration was allowed at 37°C (Incubator mod. BB6220; Heraeus Instruments, Hanau, Germany) with humidified air (5% CO2/95% O2). After the equilibration period, T (10 μM), ST (100 μM), Mes (10 μM), Prog (100 μM), E2 (10 μM) or vehicle were added to aorta segments and incubated for 15, 30 or 60 min, accordingly. In parallel experiments, aortic rings were exposed to Nil (10 μM) or GA (20 μM) for 15 min and then T (10 μM) or vehicle were incubated for 30 and 60 min. At the end of the treatment, aortic rings were homogenized in a lysis buffer containing potassium phosphate, 100 mM (pH = 7.4), sodium orthovanadate 10 mM and protease inhibitors, and the protein concentration was determined using the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Milan, Italy). The lysates were added in a reaction mixture (total volume 500 μL) containing PP (2 mM, 20 μL), L-cysteine (10 mM, 20 μL) and saline (30 μL). The reaction was performed in parafilm-sealed Eppendorf tubes and initiated by transferring tubes from ice to a 37°C water bath. After 40 min incubation, zinc acetate 1% (ZnAc; 250 μL) was added to trap any H2S emitted followed by trichloroacetic acid 10% (TCA; 250 μL). Subsequently, N,N-dimethylphenylendiammine sulphate 20 μM (DPD; 133 μL) in 7.2 M HCl and FeCl3 (30 μM, 133 μL) in 1.2 M HCl were added. After 20 min, absorbance values were measured at a wavelength of 650 nm. All samples were assayed in duplicate, and H2S concentration was calculated against a calibration curve of NaHS (3.12–250 μM). Results are expressed as nmol mg−1 protein min−1.

H2S determination in plasma samples was performed as follows: samples (200 μL) were added to Eppendorf tubes containing TCA (10%, 300 μL), in order to allow protein precipitation. Supernatant was collected after centrifugation and ZnAc (1%, 150 μL) was then added. Subsequently, DPD (20 mM, 100 μL) in 7.2 M HCl and FeCl3 (30 mM, 133 μL) in 1.2 M HCl were added to the reaction mixture, and absorbance was measured after 20 min at a wavelength of 650 nm. All samples were assayed in duplicate and H2S concentration was calculated against a calibration curve of NaHS (3.12–250 μM).

Western blotting and immunoprecipitation assay

Aortic tissue of rats stimulated with T (10 μM; 30 min) or vehicle (polyethylene glycol, PEG) were homogenized in modified RIPA buffer (Tris HCl 50 mM, pH 7.4, triton 1%, Na-deoxycholate 0.25%, NaCl 150 mM, EDTA 1 mM, PMSF 1 mM, aprotinin 10 μg·mL−1, leupeptin 20 mM, NaF 50 mM) using a polytron homogenizer (two cycles of 10 s at maximum speed). After centrifugation of homogenates at 8000× g for 15 min, protein concentration was determined by the Bradford assay using BSA as standard (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Protein from aortic tissue lysates was subjected to 10% (v v−1) SDS-PAGE and transferred to a PVDF membrane (Millipore, Temecula, CA, USA). The membrane was blocked with 5% (w v−1) skimmed milk and incubated with primary antibody, followed by incubation with an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody. Proteins were visualized with an ECL detection system (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI, USA). Anti-NR3C4 antibody was purchased from Millipore (Bellerica, MA, USA). Anti-hsp90 antibody was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Segrate, Italy). Anti-CSE antibodies were purchased from Abnova (Taipei, Taiwan).

Protein immunoprecipitations were carried out on 800 μg of total extracts. Lysates were pre-cleared by incubating samples with protein A/G-Agarose (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 1 h at 4°C and then incubated under stirring conditions for 18 h at 4°C with the antibodies. Subsequently, samples were further incubated for 1 h at 4°C with fresh protein A/G-Agarose beads. Beads were then collected by centrifugation and washed several times in lysis buffer. Negative control was performed adding beads to the cleared lysate only. Protein immunoprecipitation was also carried out on human immortalized prostatic cell line PNT1A (ATCC, Rockville, MD, USA) on 1 mg of total extracts as described above.

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) analysis

SPR studies were performed using an optical biosensor Biacore 3000 (GE Healthcare, Milan, Italy) as reported elsewhere (Dal Piaz et al., 2010). Briefly, SPR analyses were performed using a Biacore 3000 optical biosensor equipped with research grade CM5 sensor chips (GE Healthcare). Using this platform, two separate recombinant hsp90 (Vinci-Biochem, Florence, Italy) surfaces, a BSA surface and an unmodified reference surface were prepared for simultaneous analyses. Proteins (100 μg·mL−1 in 10 mM sodium acetate, pH 5.0) were immobilized on individual sensor chip surfaces at a flow rate of 5 μL·min−1 using standard amine-coupling protocols to obtain densities of 8–12 kRU. The exceeding active groups were inactivated with ethanolamine 1 M. To evaluate the affinity of CSE towards hsp90 in the presence of different concentrations of CSE, the protein was dissolved in 0.1% DMSO in PBS at five different concentrations (5, 10, 20, 50 nM and 0.1 μM), and triplicate aliquots of each compound concentration were dispensed into single-use vials. Binding experiments were performed at 25°C, using a flow rate of 5 μL·min−1, with 60 s monitoring of association and 300 s monitoring of dissociation, using PBS as a running buffer. Simple interactions were adequately fit to a single-site bimolecular interaction model, yielding a single KD. Sensorgram elaborations were performed using the BIAevaluation software provided by GE Healthcare.

Human blood experiments

Male (n = 7) and female (n = 7) healthy human volunteers were selected according to the age range of 25–50 years old; blood samples were withdrawn in fasting state, after informed consent was given, in accordance with approval from the Local Ethical Committee (Prot. n. IM.1-4/13, 23 April 2013, Azienda Ospedaliera di Rilievo Nazionale Antonio Cardarelli, Naples, Italy). T plasma levels were measured using a testosterone-specific EIA kit (Oxford Biomedical Research, Rochester Hills, MI, USA). H2S determination was performed as describe above.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way anova followed by Dunnett's post test, two-way anova followed by Bonferroni's post test or Student's unpaired t-test where appropriate. Differences were considered statistically significant when P was less than 0.05.

Chemicals

ACh, L-PE, T, E2, Mes, Prog, ST, Nil, GA, PAG, PEG, DMSO, DPD, PP, iron chloride (FeCl3), ZnAc, NaHS and L-cysteine were all purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (Milan, Italy). TCA was purchased from Carlo Erba (Arese, Milan, Italy). Testosterone was dissolved in PEG, while Nil, ST and Mes were dissolved in DMSO. GA was dissolved in H2O/PEG 1:1 mixture. Other drugs were dissolved in distilled water.

Results

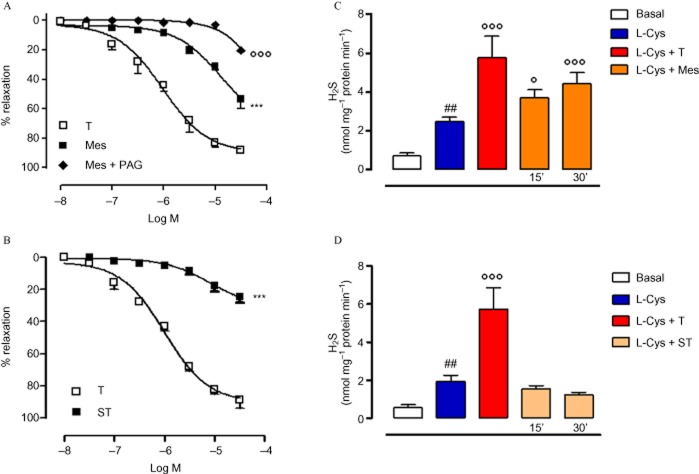

Testosterone-induced vasodilatation is mediated by H2S production following interaction with NR3C4

Recently, we demonstrated that H2S is involved in T-induced vasodilatation and that it occurs through an increase in the enzymatic conversion of L-cysteine to H2S (Bucci et al., 2009). As shown in Figure 1A, Nil, a pure NR3C4 antagonist, significantly reduced T-induced vasodilatation confirming the involvement of NR3C4 in this effect. The increase in H2S biosynthesis, observed following incubation of aortic tissues with T, was completely prevented by Nil pretreatment (Figure 1B), thus confirming that T-induced H2S release is a receptor-mediated event. Nil alone did not affect H2S production (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Vasodilatation induced by T in isolated aortic rings incubated with the androgen antagonist Nil (10 μM, 15 min) or its vehicle (DMSO, 3 μL) (A). Statistical analysis was by two-way anova with a Bonferroni post hoc test (***P < 0.001 vs. vehicle; n = 6). H2S production was evaluated after incubation of aortic tissues with T in the presence of the androgen antagonist Nil (10 μM) or vehicle (B). Statistical analysis was by one-way anova with a Dunnett's post hoc test [###P < 0.001 vs. basal; °°P < 0.01 vs. L-cysteine (L-Cys); *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 vs. L-Cys + T; n = 6].

Synthetic androgen agonist-induced vasodilatation also involves H2S biosynthesis

In order to assess the importance of NR3C4 activation in H2S release within the vascular region, a cumulative concentration–response curve using a synthetic-specific androgen agonist Mes was performed on isolated aortic rings. As shown in Figure 2A, Mes elicited a concentration-dependent vasodilator effect, which was significantly blocked by pre-incubation with the selective CSE inhibitor PAG (Asimakopoulou et al., 2013). Conversely, the anabolic agent ST, which is devoid of any androgenic activity, did not induce any appreciable effect (Figure 2B). To further confirm the essential role of NR3C4 in H2S biosynthesis, an H2S activity assay was performed in aortic rings incubated with Mes or ST (10 μM). As shown in Figure 2C, Mes acutely increased H2S production following 15 or 30 min incubation, while ST was unable to produce any similar effect (Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

Effect of the androgen agonist Mes on H2S biosynthesis in isolated aortic rings. In a separate set of experiments aortic rings were incubated with PAG (10 mM, 15 min), then a cumulative concentration–response curve to Mes was performed (A). Relaxant effect of anabolic agent ST was also tested on isolated aortic rings (B). Statistical analysis was by two-way anova with a Bonferroni post hoc test (***P < 0.001 vs. T; °°°P < 0.001 vs. Mes; n = 6). Aortic tissues were incubated with Mes (10 μM) for 15 or 30 min, and H2S was determined as described in the Methods section (C). The same experimental protocol was followed using ST (10 μM) to stimulate H2S biosynthesis in aortic tissues (D). Statistical analysis was by one-way anova with Dunnett's post hoc test [##P < 0.01 vs. basal; °P < 0.05 and °°°P < 0.001 vs. L-cysteine (L-Cys); n = 6].

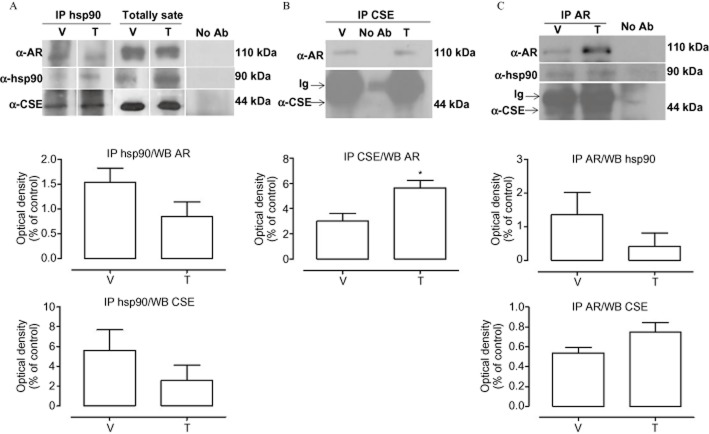

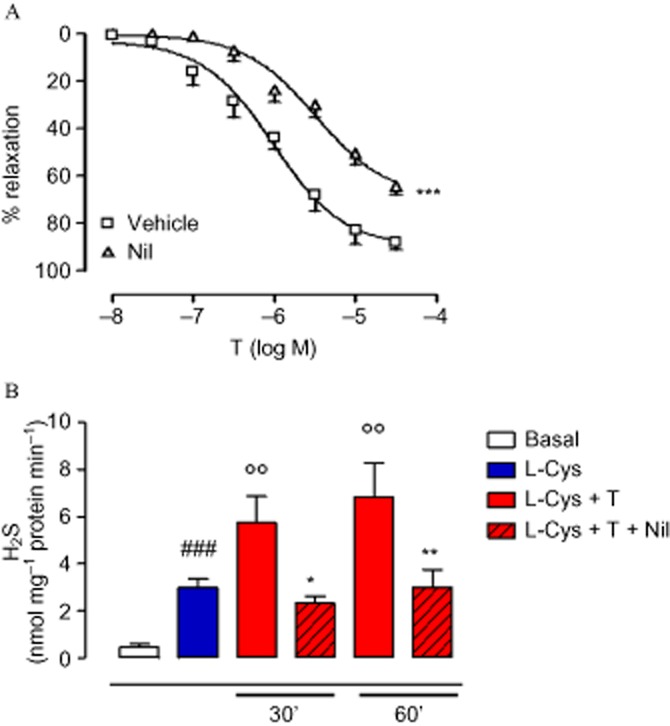

Testosterone-induced H2S biosynthesis involves hsp90

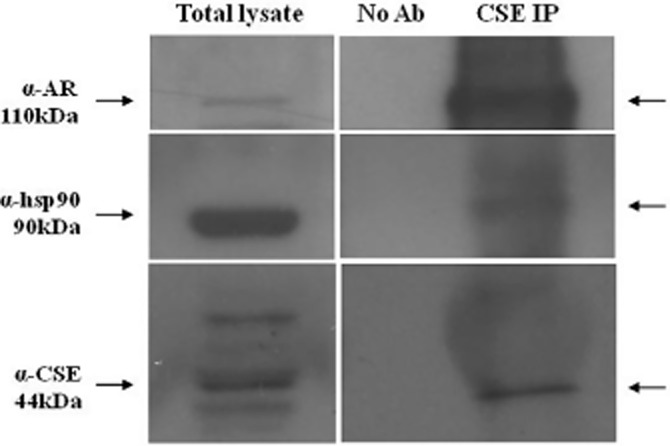

The NR3C4, as well as other steroid receptors, is present as an inactive multicomplex with several chaperone proteins in the cytoplasm (Defranco, 2000). Following hormone binding, two molecules of hsp90 dissociate from the complex, leading to receptor translocation into the nucleus (Pratt and Toft, 1997). In order to evaluate whether hsp90 could be involved in the acute vasodilator effect of T, we performed cumulative concentration–response curves to T in the presence of GA, a specific hsp90 inhibitor (Garcia-Cardena et al., 1998; Workman et al., 2007). As shown in Figure 3A, GA significantly inhibited T-induced vasodilatation, indicating the involvement of hsp90 in the vasodilator effect of T. The activity assay performed on aortic tissue confirmed these functional data, as GA markedly reduced H2S production following T administration, without affecting H2S biosynthesis per se (Figure 3B). From these results, we speculated that hsp90 contributes to T-induced H2S biosynthesis by interacting with CSE, the main enzyme accounting for H2S biosynthesis in the vasculature. Therefore, a physical interaction between CSE and hsp90 was assessed using recombinant protein in a SPR analysis. SPR data indicated a thermodynamic KD of 6.9 ± 1.1 nM for the hsp90/CSE complex, suggesting a high affinity of CSE for immobilized hsp90. The selectivity of this interaction was confirmed by the observed absence of interaction when CSE was injected on a BSA-coated surface or on the unmodified reference chip. In order to verify whether the hsp90/CSE interaction, observed in cell-free assay, also occurred in vascular tissue and that NR3C4 was also involved in this molecular mechanism, co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) analysis on homogenated aorta samples was performed. As shown in Figure 4, we found that hsp90, NR3C4 and CSE all interact. Interestingly, this interaction is constitutively present as it appeared in control conditions of all three co-IP, that is, with no addition of T (Figure 4). As expected, T treatment decreased hsp90–NR3C4 binding, as shown in co-IP lysates upon hormone stimulation. However, the resolution obtained from co-IP experiments did not allow us to quantitatively evaluate the possible regulatory effect of T on ternary complex interactions. Nevertheless, in order to confirm this result, we performed the same co-IP assay experiment with the human-immortalized prostatic cell line PNT1A, where NR3C4 is abundantly expressed. Data obtained showed a similar outcome compared with aorta tissue (Figure 5), still demonstrating that CSE is bound to both hsp90 and NR3C4 and further strengthens our findings.

Figure 3.

Involvement of hsp90 in T-induced H2S biosynthesis, evaluated in rat isolated aortic rings incubated with the hsp90 inhibitor GA (20 μM, 15 min) or its vehicle (A). Statistical analysis was by two-way anova with a Bonferroni post hoc test (***P < 0.001 vs. vehicle; n = 6). H2S was determined in aortic tissues treated with T in the presence of GA (20 μM, 15 min) (B). Statistical analysis was by one-way anova with Dunnett's post hoc test [##P < 0.01 vs. basal; °°P < 0.01 vs. L-cysteine (L-Cys); **P < 0.01 vs. L-Cys + T; n = 6].

Figure 4.

Interaction of NR3C4 (AR), hsp90 and CSE forming a multimolecular complex in aortic tissue of rats challenged with T or vehicle (V). Stimulated tissues were homogenized in modified RIPA buffer and 800 μg of total extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti- NR3C4 (AR), anti-hsp90 or anti-CSE antibodies as described in the Methods section. Samples were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred onto a PVDF membrane and immunoblotted with anti- NR3C4, anti-hsp90 or anti-CSE, as indicated. Representative blots for NR3C4/hsp90 (A), NR3C4/CSE (B) and NR3C4/hsp90/CSE (C) interaction are shown. Statistical analysis was by Student's t-test (*P < 0.05 vs. V; n = 3). No Ab, total cellular extracts incubated with A/G plus agarose beads without antibody; IP, immunoprecipitation with the corresponding antibodies. The experiments were independently performed five times with similar results (n = 5).

Figure 5.

Protein immunoprecipitation on human immortalized prostatic cell line PNT1A (ATCC, Rockville, MD, USA) were carried out on 1 mg of total extracts. No Ab, total cellular extracts incubated with A/G plus agarose beads without antibody; IP, immunoprecipitation with the corresponding antibodies. The experiments were independently performed three times with similar results (n = 3). AR represents NR3C4.

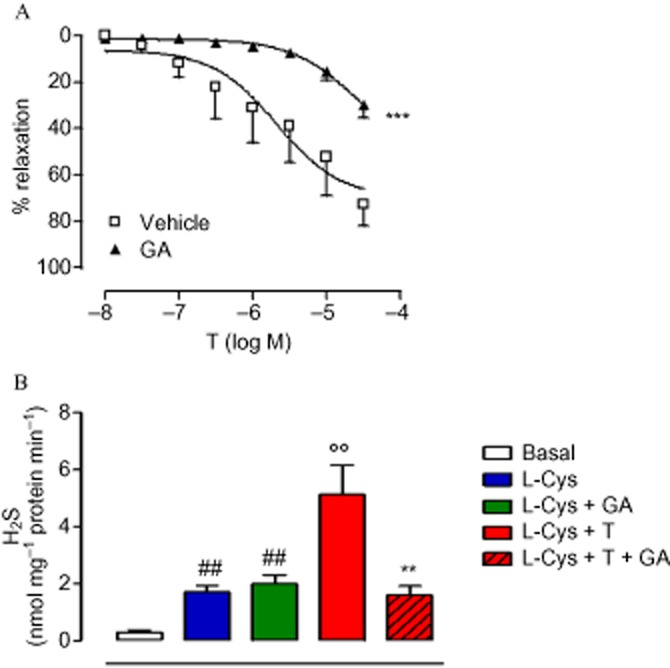

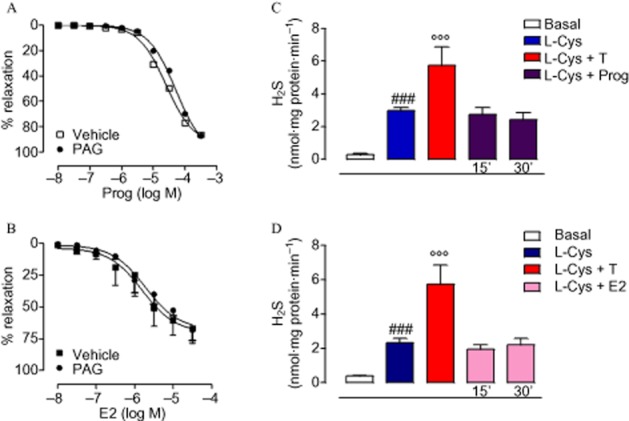

H2S as a male-specific mediator of vasodilatation: more than a clue

Next, we investigated possible gender differences in hormone-induced H2S biosynthesis, evaluating the effect of the CSE inhibitor PAG on the vasodilator effects of the female hormones Prog and E2(Bucci et al., 2002; Cutini et al., 2009). The vasodilator effects induced by either Prog or E2 were not affected by PAG pretreatment (Figure 6A,B). The lack of H2S involvement in both Prog- or E2-dependent vasorelaxation was also confirmed by the absence of an increase in H2S levels following challenge with either Prog (Figure 6C) or E2 (Figure 6D). Therefore, in contrast to T and Mes, the cysteine/H2S pathway is not involved in the vasodilator effects of either Prog or E2. Thus, H2S levels seem to be closely associated with androgenic rather than oestrogenic hormones. In order to obtain more evidence to support our findings, we measured H2S levels, as released from acid-labile sulphur (Ishigami et al., 2009), in plasma samples collected from healthy male and female volunteers. The results show that males display a significantly higher level of plasma H2S compared with females (Figure 7). Quantification of circulating levels of T in human plasma collected from both male and female donors showed that T levels were higher in male than female individuals, and these were associated with increased circulating levels of H2S (Figure 7).

Figure 6.

H2S biosynthesis involvement in E2- and Prog-induced vasodilator effect on isolated aortic rings pre-contracted with PE (1 μM). Cumulative concentration–response curve to Prog (10 nM–300 μM) was performed in the presence or absence of CSE inhibitor PAG (10 mM, 15 min) (A). The same approach was used to investigate the role of H2S production in the E2-induced vasodilator effect (10 nM–30 μM) (B). Statistical analysis was by two-way anova with a Bonferroni post hoc test. H2S was determined in aortic tissues incubated with Prog (100 μM) for 15 or 30 min (C). The same analysis was carried out in isolated aortic tissues challenged with E2 (10 μM) for 15 or 30 min (D). Statistical analysis was by one-way anova with Dunnett's post hoc test [###P < 0.001 vs. basal; °°°P < 0.001 vs. L-cysteine (L-Cys); n = 6].

Figure 7.

Quantification of human H2S plasma levels, as released from acid-labile sulfur, in male and female healthy donors (age range 25–50 years). H2S and testosterone plasma levels were detected as described in the Methods section. T levels in male subjects were higher compared with females and H2S values followed the same profile, being higher in males compared with females. Statistical analysis was by Student's t-test (***P < 0.001, *P < 0.05; n = 7).

Discussion and conclusions

The gender difference in cardiovascular function is a well-established concept that has been extensively supported by experimental and clinical studies. In particular androgens and oestrogens have been shown to play different and specific gender-related functions through both genomic and non-genomic mechanisms. It is widely known that the interaction of T with the NR3C4 (affinity 0.66 nM) (Saartok et al., 1984) is a key triggering event. Recently, we demonstrated that testosterone-induced vasodilatation is a non-genomic effect involving the H2S pathway (Bucci et al., 2009). At that stage, it was not clear whether this non-genomic vascular effect of T involved its interaction with NR3C4. Here, data obtained from functional experiments showed that the pure NR3C4 antagonist Nil significantly inhibits T-induced vasodilatation. Furthermore, in homogenized aorta samples, Nil pretreatment abolished T-stimulated H2S production. These data clearly indicate that H2S biosynthesis occurs upon interaction between T and NR3C4. Nevertheless, it is noteworthy to underline that Nil abolishes H2S biosynthesis but partially reduces T-induced vasodilatation. This apparent discrepancy is probably because the T-dependent H2S biosynthesis, driven by the interaction of T with NR3C4, only partly accounts for the vasodilator action of T. Indeed, this T-induced vasodilator effect also results from activation of other mediators, including NO, as shown here (Supporting Information Fig. S1) and in line with current literature (Campelo et al., 2012; Lu et al., 2012; Puttabyatappa et al., 2013).

Therefore, it appears that NR3C4 activation is the key trigger for H2S biosynthesis. In order to confirm that the interaction of the androgens with NR3C4 is the key common event triggering the H2S biosynthesis, we used the synthetic androgen agonist Mes (affinity for NR3C4 0.27 nM) (Saartok et al., 1984), which is used in male hypogonadism therapy (Jockenhovel et al., 1999; Schubert et al., 2003). Similarly to T, Mes caused a concentration-dependent vasodilatation as well as increased H2S biosynthesis. In addition, its vasorelaxant effect was inhibited by the selective CSE inhibitor PAG. Therefore, Mes replicated the testosterone effect supporting the hypothesis that NR3C4 activation is essential for the induction of H2S biosynthesis. To further confirm our hypothesis, we performed the same study but using ST. ST is a 17α-alkylated androgen used as anabolic agent (Fernandez et al., 1994) whose biological actions are mediated by steroid-binding molecules instead of NR3C4 activation (Fernandez et al., 1994; Boada et al., 1996). The inability of ST to relax aorta tissue and to stimulate H2S biosynthesis endorsed our conclusion that NR3C4 activation is a crucial requirement to trigger H2S production.

All steroid receptors share the same mechanism of activation, where a key role is played by hsp90; in particular, hsp90 has been shown to maintain steroid receptors in a transcriptionally inactive state within the target cells (Falkenstein et al., 2000). Following hormone binding, hsp90 dissociates from the receptor (Pratt and Toft, 1997). Thus, the ligand-receptor complex changes its conformation, initiating a cascade of events leading to the activation of a specific DNA sequence and regulating gene transcription (Kumar et al., 1987; Gallo and Kaufman, 1997). In order to verify whether NR3C4-derived hsp90 is involved in H2S biosynthesis, we used the specific hsp90 inhibitor GA. Blockade of hsp90 inhibited testosterone-induced vasodilatation and attenuated H2S biosynthesis, mimicking the effect of the NR3C4 antagonist Nil. Therefore, NR3C4 and hsp90 seemed to be crucial in driving H2S biosynthesis by CSE in vasculature. At this stage, we hypothesized that hsp90 could directly interact with CSE. We first tested this hypothesis in a cell-free assay using the SPR technique. This experimental approach confirmed a strong physical interaction between hsp90 and CSE. Based on this, we next performed co-IP in aortic tissue, a step forward to determine whether this interaction takes place also at the tissue level, a more complex environment than a cell-free assay. The co-IP study confirmed the existence of a multiprotein complex formed by an interaction between hsp90, CSE and NR3C4. Furthermore, in line with the current literature, T decreased hsp90/NR3C4 binding (Falkenstein et al., 2000; Smith et al., 2008). These results provide novel information about the intracellular localization of CSE and its interaction with hsp90 and NR3C4, which is an essential requirement for testosterone-induced increase in H2S production. Indeed CSE appears to be physically associated with NR3C4 and hsp90, even in resting conditions.

In parallel experiments performed with female hormones, we found that the L-cysteine/CSE/H2S pathway was not involved in vascular effects evoked by E2 or Prog. This finding indicates that H2S biosynthesis is a hormone-specific process initiated by the interaction between T and NR3C4, which clearly involves hsp90 and CSE. Therefore, it is feasible that NR3C4 may activate CSE through hsp90, in turn, stimulating H2S production. Thus, our data suggest that the L-cysteine/CSE/H2S pathway is more susceptible to control by androgen hormones than by oestrogens. This hypothesis implied that a difference in H2S biosynthesis between male and female subjects may exist. Determination of H2S in human blood samples collected from male and female healthy volunteers supported this hypothesis. It is noteworthy that the higher testosterone plasma levels found in males compared with females paralleled H2S levels. Considering that testosterone levels are known to be higher in male individuals (Southren et al., 1965), as also found in the present study, these data provide, for the first time to our knowledge, evidence that H2S is preferentially abundant in plasma of male individuals. These preliminary findings allow us to speculate that in male subjects, constant low-level increases in H2S values, due to a higher circulating testosterone concentration, provide a vasoprotective function, rather than acute, profound vasodilatation.

In conclusion, our results shed light on a novel molecular mechanism operating in the vascular network. Thus, following interaction between androgen and NR3C4, H2S biosynthesis is triggered. This process involves hsp90 and CSE, as demonstrated by molecular and functional data. Indeed, H2S biosynthesis can be blocked by either deleting hsp90 or by inhibiting CSE. The existence of an association among hsp90, CSE and NR3C4 has been shown in basal as well as stimulated conditions. Therefore, H2S biosynthesis in the rat aorta is modulated by androgen hormones, but is not triggered by female hormones E2 or Prog. These findings further consolidate the view that androgens can exert protective actions on cardiovascular and metabolic functions (Deenadayalu et al., 2012; Papierska et al., 2012; Soisson et al., 2012) by triggering a variety of beneficial effects mediated by H2S (Zanardo et al., 2006; Zhao et al., 2008).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Professor Nunziatina De Tommasi and Dr Antonio Vassallo, Department of Pharmacy, University of Salerno for surface plasmon resonance analysis; Dr Antonio Mancini, Azienda Ospedaliera di Rilievo Nazionale Antonio Cardarelli, Naples, Italy, for availability of human blood samples. This work has been supported by Italian Government programme PRIN2012, P.O.R. Campania FSE 2007–2013, Progetto CREMe, CUP B25B09000050007 and COST Action BM1005 (ENOG: European network on gasotransmitters).

Glossary

- NR3C4

androgen receptor

- co-IP

co-immunoprecipitation

- CSE

cystathionine-γ lyase

- DPD

N,N-dimethylphenylendiammine sulphate

- E2

17-β-oestradiol

- GA

geldanamycin

- H2S

hydrogen sulphide

- hsp90

heat shock protein 90

- Mes

mesterolone

- NaHS

sodium hydrosulphide

- Nil

nilutamide

- PAG

propargylglycine

- PE

phenylephrine

- PEG

polyethylene glycol 400

- PP

pyridoxal-5′-phosphate hydrate

- Prog

progesterone

- SPR

surface plasmon resonance

- ST

stanozolol

- T

testosterone

- TCA

trichloroacetic acid

- ZnAc

zinc acetate

Author contributions

V. B. and V. V. performed the experiments and data interpretation. D. M. performed immunoprecipitation experiments and analysed the data. R. D. and A. I. performed the experiments. R. S. performed the statistical analysis. M. B. conceived and coordinated the experiments. F. E. revised the manuscript and wrote the experimental part of molecular biology. G. C. planned and coordinated the project, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

None.

Supporting Information

Figure S1 Relaxation induced by testosterone in aortic rings is reduced by endothelium removal (a) or NOS inhibitor L-NAME (100 μM) pretreatment (b). Statistical analyses were made using two-way anova with a Bonferroni post hoc test [***P < 0.001 vs. +endothelium (a) or control (b); n = 6].

References

- Adams MR, Williams JK, Kaplan JR. Effects of androgens on coronary artery atherosclerosis and atherosclerosis-related impairment of vascular responsiveness. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1995;15:562–570. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.15.5.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Spedding M, Peters JA, Harmar AJ CGTP Collaborators. The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14: Nuclear hormone receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;170:1652–1675. doi: 10.1111/bph.12448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnal JF, Fontaine C, Billon-Gales A, Favre J, Laurell H, Lenfant F, et al. Estrogen receptors and endothelium. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:1506–1512. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.191221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asimakopoulou A, Panopoulos P, Chasapis CT, Coletta C, Zhou Z, Cirino G, et al. Selectivity of commonly used pharmacological inhibitors for cystathionine beta synthase (CBS) and cystathionine gamma lyase (CSE) Br J Pharmacol. 2013;169:922–932. doi: 10.1111/bph.12171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhasin S, Storer TW, Berman N, Callegari C, Clevenger B, Phillips J, et al. The effects of supraphysiologic doses of testosterone on muscle size and strength in normal men. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199607043350101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boada LD, Fernandez L, Zumbado M, Luzardo OP, Chirino R, Diaz-Chico BN. Identification of a specific binding site for the anabolic steroid stanozolol in male rat liver microsomes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;279:1123–1129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucci M, Roviezzo F, Cicala C, Pinto A, Cirino G. 17-beta-oestradiol-induced vasorelaxation in vitro is mediated by eNOS through hsp90 and akt/pkb dependent mechanism. Br J Pharmacol. 2002;135:1695–1700. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucci M, Mirone V, Di Lorenzo A, Vellecco V, Roviezzo F, Brancaleone V, et al. Hydrogen sulphide is involved in testosterone vascular effect. Eur Urol. 2009;56:378–383. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campelo AE, Cutini PH, Massheimer VL. Cellular actions of testosterone in vascular cells: mechanism independent of aromatization to estradiol. Steroids. 2012;77:1033–1040. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2012.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crews JK, Khalil RA. Antagonistic effects of 17 beta-estradiol, progesterone, and testosterone on Ca2+ entry mechanisms of coronary vasoconstriction. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19:1034–1040. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.4.1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutini P, Selles J, Massheimer V. Cross-talk between rapid and long term effects of progesterone on vascular tissue. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2009;115:36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2009.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dal Piaz F, Tosco A, Eletto D, Piccinelli AL, Moltedo O, Franceschelli S, et al. The identification of a novel natural activator of p300 histone acetyltranferase provides new insights into the modulation mechanism of this enzyme. Chembiochem. 2010;11:818–827. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200900721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deenadayalu V, Puttabyatappa Y, Liu AT, Stallone JN, White RE. Testosterone-induced relaxation of coronary arteries: activation of BKCa channels via the cGMP-dependent protein kinase. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;302:H115–H123. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00046.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deenadayalu VP, White RE, Stallone JN, Gao X, Garcia AJ. Testosterone relaxes coronary arteries by opening the large-conductance, calcium-activated potassium channel. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;281:H1720–H1727. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.4.H1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Defranco DB. Role of molecular chaperones in subnuclear trafficking of glucocorticoid receptors. Kidney Int. 2000;57:1241–1249. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00957.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ettinger B, Friedman GD, Bush T, Quesenberry CP., Jr Reduced mortality associated with long-term postmenopausal estrogen therapy. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87:6–12. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00358-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falkenstein E, Tillmann HC, Christ M, Feuring M, Wehling M. Multiple actions of steroid hormones – a focus on rapid, nongenomic effects. Pharmacol Rev. 2000;52:513–556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farish E, Spowart K, Barnes JF, Fletcher CD, Calder A, Brown A, et al. Effects of postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy on lipoproteins including lipoprotein(a) and LDL subfractions. Atherosclerosis. 1996;126:77–84. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(96)05895-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez L, Chirino R, Boada LD, Navarro D, Cabrera N, del Rio I, et al. Stanozolol and danazol, unlike natural androgens, interact with the low affinity glucocorticoid-binding sites from male rat liver microsomes. Endocrinology. 1994;134:1401–1408. doi: 10.1210/endo.134.3.8119180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fusco F, di Villa Bianca R, Mitidieri E, Cirino G, Sorrentino R, Mirone V. Sildenafil effect on the human bladder involves the L-cysteine/hydrogen sulfide pathway: a novel mechanism of action of phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors. Eur Urol. 2012;62:1174–1180. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo MA, Kaufman D. Antagonistic and agonistic effects of tamoxifen: significance in human cancer. Semin Oncol. 1997;24(1 Suppl. 1):S1–71–S1–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Cardena G, Fan R, Shah V, Sorrentino R, Cirino G, Papapetropoulos A, et al. Dynamic activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase by Hsp90. Nature. 1998;392:821–824. doi: 10.1038/33934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes MP, Sinha D, Russell KS, Collinge M, Fulton D, Morales-Ruiz M, et al. Membrane estrogen receptor engagement activates endothelial nitric oxide synthase via the PI3-kinase-Akt pathway in human endothelial cells. Circ Res. 2000;87:677–682. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.8.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman SM, Robinson JT, McCredie RJ, Adams MR, Boyer MJ, Celermajer DS. Androgen deprivation is associated with enhanced endothelium-dependent dilatation in adult men. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17:2004–2009. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.10.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu JC, Williams SB, O'Malley AJ, Smith MR, Nguyen PL, Keating NL. Androgen-deprivation therapy for nonmetastatic prostate cancer is associated with an increased risk of peripheral arterial disease and venous thromboembolism. Eur Urol. 2012;61:1119–1128. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.01.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang M, Li J, Teoh H, Man RY. Low concentrations of 17beta-estradiol reduce oxidative modification of low-density lipoproteins in the presence of vitamin C and vitamin E. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;27:438–441. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(99)00086-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishigami M, Hiraki K, Umemura K, Ogasawara Y, Ishii K, Kimura H. A source of hydrogen sulfide and a mechanism of its release in the brain. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11:205–214. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii I, Akahoshi N, Yamada H, Nakano S, Izumi T, Suematsu M. Cystathionine gamma-lyase-deficient mice require dietary cysteine to protect against acute lethal myopathy and oxidative injury. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:26358–26368. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.147439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jockenhovel F, Bullmann C, Schubert M, Vogel E, Reinhardt W, Reinwein D, et al. Influence of various modes of androgen substitution on serum lipids and lipoproteins in hypogonadal men. Metabolism. 1999;48:590–596. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(99)90056-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keaney JF, Jr, Shwaery GT, Xu A, Nicolosi RJ, Loscalzo J, Foxall TL, et al. 17 beta-estradiol preserves endothelial vasodilator function and limits low-density lipoprotein oxidation in hypercholesterolemic swine. Circulation. 1994;89:2251–2259. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.5.2251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilkenny C, Browne W, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG. Animal research: reporting in vivo experiments: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1577–1579. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00872.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V, Green S, Stack G, Berry M, Jin JR, Chambon P. Functional domains of the human estrogen receptor. Cell. 1987;51:941–951. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90581-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung SW, Teoh H, Keung W, Man RY. Non-genomic vascular actions of female sex hormones: physiological implications and signalling pathways. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2007;34:822–826. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2007.04686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levonen AL, Lapatto R, Saksela M, Raivio KO. Human cystathionine gamma-lyase: developmental and in vitro expression of two isoforms. Biochem J. 2000;347(Pt 1):291–295. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy D, Kannel WB. Cardiovascular risks: new insights from Framingham. Am Heart J. 1988;116(1 Pt 2):266–272. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(88)90099-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu PY, Death AK, Handelsman DJ. Androgens and cardiovascular disease. Endocr Rev. 2003;24:313–340. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y, O'Dowd BF, Orrego H, Israel Y. Cloning and nucleotide sequence of human liver cDNA encoding for cystathionine gamma-lyase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;189:749–758. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)92265-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y, Fu Y, Ge Y, Juncos LA, Reckelhoff JF, Liu R. The vasodilatory effect of testosterone on renal afferent arterioles. Gend Med. 2012;9:103–111. doi: 10.1016/j.genm.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malkin CJ, Jones RD, Jones TH, Channer KS. Effect of testosterone on ex vivo vascular reactivity in man. Clin Sci (Lond) 2006;111:265–274. doi: 10.1042/CS20050354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath J, Drummond G, McLachlan E, Kilkenny C, Wainwright C. Guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1573–1576. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00873.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mooradian AD, Morley JE, Korenman SG. Biological actions of androgens. Endocr Rev. 1987;8:1–28. doi: 10.1210/edrv-8-1-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nettleship JE, Jones RD, Channer KS, Jones TH. Testosterone and coronary artery disease. Front Horm Res. 2009;37:91–107. doi: 10.1159/000176047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papierska L, Rabijewski M, Kasperlik-Zaluska A, Zgliczynski W. Effect of DHEA supplementation on serum IGF-1, osteocalcin, and bone mineral density in postmenopausal, glucocorticoid-treated women. Adv Med Sci. 2012;57:51–57. doi: 10.2478/v10039-011-0060-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perusquia M, Navarrete E, Gonzalez L, Villalon CM. The modulatory role of androgens and progestins in the induction of vasorelaxation in human umbilical artery. Life Sci. 2007;81:993–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2007.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt WB, Toft DO. Steroid receptor interactions with heat shock protein and immunophilin chaperones. Endocr Rev. 1997;18:306–360. doi: 10.1210/edrv.18.3.0303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puttabyatappa Y, Stallone JN, Ergul A, El-Remessy AB, Kumar S, Black S, et al. Peroxynitrite mediates testosterone-induced vasodilation of microvascular resistance vessels. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2013;345:7–14. doi: 10.1124/jpet.112.201947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reckelhoff JF, Zhang H, Granger JP. Testosterone exacerbates hypertension and reduces pressure-natriuresis in male spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 1998;31(1 Pt 2):435–439. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.31.1.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saartok T, Dahlberg E, Gustafsson JA. Relative binding affinity of anabolic-androgenic steroids: comparison of the binding to the androgen receptors in skeletal muscle and in prostate, as well as to sex hormone-binding globulin. Endocrinology. 1984;114:2100–2106. doi: 10.1210/endo-114-6-2100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert M, Bullmann C, Minnemann T, Reiners C, Krone W, Jockenhovel F. Osteoporosis in male hypogonadism: responses to androgen substitution differ among men with primary and secondary hypogonadism. Horm Res. 2003;60:21–28. doi: 10.1159/000070823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibuya N, Mikami Y, Kimura Y, Nagahara N, Kimura H. Vascular endothelium expresses 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase and produces hydrogen sulfide. J Biochem. 2009;146:623–626. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvp111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AM, Bennett RT, Jones TH, Cowen ME, Channer KS, Jones RD. Characterization of the vasodilatory action of testosterone in the human pulmonary circulation. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2008;4:1459–1466. doi: 10.2147/vhrm.s3995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soisson V, Brailly-Tabard S, Empana JP, Feart C, Ryan J, Bertrand M, et al. Low plasma testosterone and elevated carotid intima-media thickness: importance of low-grade inflammation in elderly men. Atherosclerosis. 2012;223:244–249. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2012.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southren AL, Tochimoto S, Carmody NC, Isurugi K. Plasma production rates of testosterone in normal adult men and women and in patients with the syndrome of feminizing testes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1965;25:1441–1450. doi: 10.1210/jcem-25-11-1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Willett WC, Manson JE, Rosner B, Speizer FE, et al. Postmenopausal estrogen therapy and cardiovascular disease. Ten-year follow-up from the nurses' health study. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:756–762. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199109123251102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stipanuk MH. Sulfur amino acid metabolism: pathways for production and removal of homocysteine and cysteine. Annu Rev Nutr. 2004;24:539–577. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.24.012003.132418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stipanuk MH, Beck PW. Characterization of the enzymic capacity for cysteine desulphhydration in liver and kidney of the rat. Biochem J. 1982;206:267–277. doi: 10.1042/bj2060267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tep-areenan P, Kendall DA, Randall MD. Testosterone-induced vasorelaxation in the rat mesenteric arterial bed is mediated predominantly via potassium channels. Br J Pharmacol. 2002;135:735–740. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traish AM, Guay A, Feeley R, Saad F. The dark side of testosterone deficiency: I. Metabolic syndrome and erectile dysfunction. J Androl. 2009;30:10–22. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.108.005215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Workman P, Burrows F, Neckers L, Rosen N. Drugging the cancer chaperone HSP90: combinatorial therapeutic exploitation of oncogene addiction and tumor stress. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1113:202–216. doi: 10.1196/annals.1391.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu FC, von Eckardstein A. Androgens and coronary artery disease. Endocr Rev. 2003;24:183–217. doi: 10.1210/er.2001-0025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang G, Wu L, Jiang B, Yang W, Qi J, Cao K, et al. H2S as a physiologic vasorelaxant: hypertension in mice with deletion of cystathionine gamma-lyase. Science. 2008;322:587–590. doi: 10.1126/science.1162667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanardo RC, Brancaleone V, Distrutti E, Fiorucci S, Cirino G, Wallace JL. Hydrogen sulfide is an endogenous modulator of leukocyte-mediated inflammation. FASEB J. 2006;20:2118–2120. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6270fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Zhang LK, Zhang CY, Zeng XJ, Yan H, Jin HF, et al. Regulatory effect of hydrogen sulfide on vascular collagen content in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertens Res. 2008;31:1619–1630. doi: 10.1291/hypres.31.1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1 Relaxation induced by testosterone in aortic rings is reduced by endothelium removal (a) or NOS inhibitor L-NAME (100 μM) pretreatment (b). Statistical analyses were made using two-way anova with a Bonferroni post hoc test [***P < 0.001 vs. +endothelium (a) or control (b); n = 6].