Abstract

The ability to study live cells as they progress through the stages of cancer provides the opportunity to discover dynamic networks underlying pathology, markers of early stages, and ways to assess therapeutics. Genetically engineered animal models of cancer, where it is possible to study the consequences of temporal-specific induction of oncogenes or deletion of tumor suppressors, have yielded major insights into cancer progression. Yet differences exist between animal and human cancers, such as in markers of progression and response to therapeutics. Thus, there is a need for human cell models of cancer progression. Most human cell models of cancer are based on tumor cell lines and xenografts of primary tumor cells that resemble the advanced tumor state, from which the cells were derived, and thus do not recapitulate disease progression. Yet a subset of cancer types have been reprogrammed to pluripotency or near-pluripotency by blastocyst injection, by somatic cell nuclear transfer and by induced pluripotent stem cell (iPS) technology. The reprogrammed cancer cells show that pluripotency can transiently dominate over the cancer phenotype. Diverse studies show that reprogrammed cancer cells can, in some cases, exhibit early-stage phenotypes reflective of only partial expression of the cancer genome. In one case, reprogrammed human pancreatic cancer cells have been shown to recapitulate stages of cancer progression, from early to late stages, thus providing a model for studying pancreatic cancer development in human cells where previously such could only be discerned from mouse models. We discuss these findings, the challenges in developing such models and their current limitations, and ways that iPS reprogramming may be enhanced to develop human cell models of cancer progression.

Keywords: cancer, iPS, pluripotency, progression

Introduction

Over the past two decades, diverse cellular models of cancer, in combination with biochemical and imaging tools, have greatly improved the early diagnosis and treatment of various cancers. Tests exist for the early detection of cervical, colon, and breast cancers and mortality has been steadily declining (Arteaga et al, 2014). Despite these advances, cancers such as pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) retain a dismal prognosis due to a paucity of clinical symptoms and biomarkers for early-stage disease (Cantley et al, 2012). The failure to detect early disease prevents the application and testing of therapeutics that could be used to inhibit disease progression. Genetically engineered animal models in mouse and zebrafish have been developed for diverse cancers (Tuveson & Jacks, 2002; Liu & Leach, 2011; Ablain & Zon, 2013). Such models can provide insights into the basis of cancer development that have helped generate treatments, such as for acute promyelocytic leukemia (Wang & Chen, 2008; Nardella et al, 2011). Yet there are cross-species differences between animal and human cancers with regard to the size of tumors, cancer susceptibility, spectrum of age-related cancers, and telomere lengths (DePinho, 2000; Rangarajan & Weinberg, 2003). Cancer therapeutics that work in mouse models can fail in clinical human trials (Ledford, 2011; Begley & Ellis, 2012). To complement these limitations, human solid tumors, organoid cultures thereof (Gao et al, 2014; Li et al, 2014), and cell lines (Sharma et al, 2010) have been engrafted into immunocompromised mice either as tumor fragments (Tentler et al, 2012), dispersed cells, or cells sorted for tumor initiating cells/cancer stem cells (CSC) (Ishizawa et al, 2010; Nguyen et al, 2012). In these contexts, tumors inevitably arise that resemble the parental tumor state from which the cells were derived and do not undergo early-stage progression (Tentler et al, 2012). Primary human mammary epithelial cells can undergo cancer progression in mouse xenografts, but require prior transformation with oncogenes rather than employing endogenous genetic changes found in tumors (Wu et al, 2009). Currently, there are few human cell models of cancer progression that are dependent upon naturally occurring genetic mutations.

Here, we describe the use of somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) on mouse cancer cells and induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cell technology to model human cancer progression. Cancer progression by the SCNT or iPS reprogrammed cells can help reveal new networks for early-stage disease, potential early-stage biomarkers, and human cell models in which therapeutics can be assessed. We first discuss the history of reprogramming of cancer cells to pluripotency, as initiated with blastocyst injection and somatic nuclear transfer. We also describe mechanisms that may underlie a temporary dominance of pluripotency over the cancer genome and the use of iPS technology to elicit such dominance. We then review the advances and challenges associated with iPS-based approaches, along with the future prospects for developing new human cell models of cancer progression.

Early examples of cancer cell reprogramming to pluripotency

Several lines of evidence show that cancer progression can be elicited by reversible epigenetic changes as well as by irreversible mutations in oncogenic and tumor suppressor genes (Esteller, 2007). The first experimental evidence of tumor reversibility was described in crown-gall tumors in plants over a half century ago (Braun, 1959). Braun had hypothesized that the individual pluripotent teratoma cells of crown-gall tumors might be recovered from the cancer in grafting experiments. To test his idea, he grafted the shoots from crown-gall teratoma cells serially to the cut stem ends of the healthy tobacco plants. The grafted teratoma tissue gradually developed more normal appearing shoots, which eventually flowered and developed seeds. He concluded that ‘the cellular alteration in crown gall did not involve a somatic mutation at the nuclear gene level and rather some yet uncharacterized cytoplasmic entity is responsible for the cellular changes that underlie the tumorous state in the crown-gall disease.'

In mammalian development, the fertilized egg, or zygote, undergoes cell divisions to reach the blastocyst stage. The blastocyst contains the first differentiated structures, consisting of an outer layer of trophectoderm and an inner cell mass (ICM) that develops into the embryo and yolk sac. Many cells within the inner cell mass are considered pluripotent, because they give rise to all three germ layers (endoderm, ectoderm, and mesoderm) and derived tissues in the embryo. The most stringent test of whether exogenous mammalian cells are pluripotent is to inject them into a blastocyst and determine whether they contribute to the embryo and, ultimately, the animal proper (Lin, 1966). Individual malignant stem cells of murine embryonal teratomas (embryonic carcinoma, EC) injected into 280 blastocysts yielded 45 apparently normal embryos or fetuses, and such cells injected into 183 blastocysts yielded 48 apparently normal live mice (Mintz & Illmensee, 1975). All of three fetuses analyzed were mosaic, with substantial tissue contributions from teratoma cells, indicating the cells' pluripotency. Notably, many genes that had been silent or undetectable in the tumor, such as immunoglobulin, hemoglobin, MUP, agouti genes, were expressed in the appropriate tissues. The authors concluded that ‘conversion to neoplasia did not involve structural changes in the genome, but rather a change in gene expression.’

The developmental pluripotency of somatic cell nucleus can be tested by implanting them into enucleated oocytes, that is, somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) (Gurdon et al, 1958). By SCNT, a subset of cancer cells such as certain renal tumor cells, medulloblastoma cells, RAS-induced melanoma cells, and EC cells were able to be reprogrammed to pluripotency (McKinnell et al, 1969; Blelloch et al, 2004; Hochedlinger et al, 2004). Donor nuclei from triploid frog renal tumors were reprogrammed by injection into enucleated frog eggs, developed into blastulas with a higher efficiency than diploid nuclei (23% versus 7.7%). Yet only 21% of the triploid, tumor-derived blastulas developed into swimming embryos compared to 100% of the blastulas from normal diploid nuclei (McKinnell et al, 1969). The living triploid tadpoles differentiated into functional embryonic tissues of many types and the descendant tail fins regenerated appropriately, demonstrating pluripotency of the reprogrammed tumor genome (McKinnell et al, 1969).

Hochedlinger et al (2004) attempted the reprogramming by SCNT of diverse mouse cancer cells, including a p53−/− lymphoma, moloney murine leukemia virus-induced leukemia, PML-RAR transgene-induced leukemia, hypomethylated Chip/c lymphoma, p53−/− breast cancer cell line, and an ink4a/Arf−/−, RAS-inducible melanoma cell line. All SCNT-reprogrammed cancer cell lines, but no primary tumor cells, were able to develop normal appearing blastocysts, with much greater efficiency in cancer cell lines harboring mutant tumor suppressors. SCNT-derived blastocysts whose zona pellucida was removed were placed onto irradiated murine embryonic fibroblast to derive embryonic stem (ES) cells. However, such SCNT-ES cell lines were only made from an Ink4a/Arf−/−, RAS-inducible melanoma cell line, suggesting that only certain cancer genomes or cell types are amenable to the manipulation.

To assess their autonomous developmental potential, melanoma SCNT-ES cells were injected into tetraploid blastocysts, where transplanted wild-type ES cells can exclusively give rise to the embryo and tetraploid cells become the placenta (Wang et al, 1997). The resulting embryos developed up to day 9.5 of mouse gestation (E9.5) with a beating heart, closed neural tube, and developing limb and tail buds. Yet at later stages, embryos were not recovered, presumably because of the reactivation of irreversible genetic alterations of the melanoma.

However, in a chimeric blastocyst assay, where normal and donor cells can contribute to the embryo, the SCNT-ES cells, despite having major severe chromosomal changes from the original cancer, showed remarkable differentiation by contributing to skin, intestine, heart, kidney, lungs, thymus, and liver in newborn chimeric mice and to adult lineages such as the lymphoid compartment in Rag2-deficient chimeric mice (Hochedlinger et al, 2004). These findings show that the oocyte cytoplasm can reprogram the epigenetic state of the donor cancer cell nucleus into a pluripotent state that supports differentiation into multiple somatic cell types.

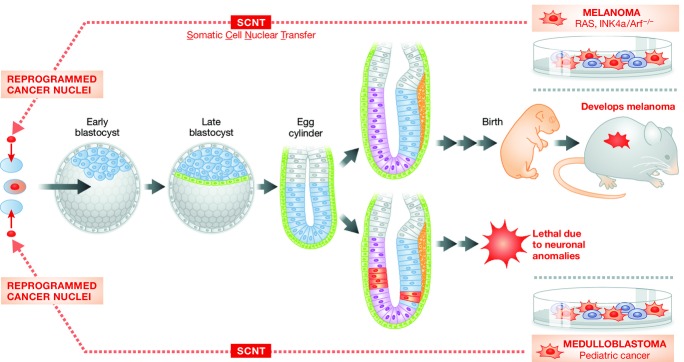

The SCNT-ES-derived adult chimeric mice developed multiple primary melanoma lesions with an average latency of 19 days, comparable to the latency required for the development of recurrent tumors or the emergence of tumors derived from transplanted melanoma cells (Chin et al, 1999). Interestingly, 33% of the chimeras from melanoma SCNT-ES cells developed rhabdomyosarcoma, which has an overlapping pathway with melanoma, showing the consequence of the ‘melanoma genome’ expressed in a different tissue (Hochedlinger et al, 2004) (Fig1, top).

Figure 1.

Cancer cell reprogramming by somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT). Somatic cell nuclear transfer from medulloblastoma (left) or melanoma (right) cells leads to reprogramming of the cancer cell nucleus. When the resulting reprogrammed cells are injected into blastocysts, dominance of the early pluripotent state apparently suppresses the cancer phenotype and allows partial embryonic development. From medulloblastoma cells, lethality results shortly after gastrulation, whereas from melanoma cells in chimeric blastocysts, the cancer genome cells contribute to many tissues but melanoma ultimately ensues.

Li et al (2003) tested the epigenetic reprogramming of medulloblastoma, a pediatric brain tumor, originating from the granule neuron precursors of the developing cerebellum. The medulloblastoma cells were isolated from Ptc+/− mice and used for SCNT. Although transferred SCNT cells developed into blastocysts that were morphologically indistinguishable from those derived nuclei of spleen control cells, no viable embryos were identified after E8.5 in the transplanted pseudo-pregnant mice. Intriguingly, while the embryos at E7.5 days appeared grossly normal and contained all three germ layers as well as an ectoplacental cone, a chorion, an amnion, a Reichert's membrane, a yolk sac cavity, and an amniotic cavity, embryos at E8.5 showed more extensive differentiation of the cephalic vesicles and neural tubes, implying that the lack of viable embryos after E8.5 could be attributed to dysregulated neuronal lineages. Thus, this report demonstrates the mutation(s) underlying medulloblastoma was suppressed during pre-implantation and early germ layer stages, and became activated within the context of the cerebellar granule cell lineage, ultimately leading to embryonic lethality (Fig1, bottom).

In summary, the cancer genome can be suppressed during the pre-implantation blastocyst stage when certain cancer cells are first reprogrammed to pluripotency by nuclear transfer (SCNT-ES). The resultant pluripotent cells can then differentiate into multiple early developmental cell types of the embryo. Yet, later in organogenesis, the cancer genome becomes activated, particularly in the cell lineage in which the original cancer occurred. This leads to the question of how the pluripotency network can suppress the cancer phenotype sufficiently to allow early tissue differentiation and development.

Expression of proto-oncogenes during development and suppression by pluripotency

The expression of proto-oncogenes is spatially and temporally regulated during embryogenesis, with certain proto-oncogenes being transiently activated in only certain tissues and in late lineage specification (Pfeifer-Ohlsson et al, 1984, 1985; Slamon & Cline, 1984; Adamson, 1987; Wilkinson et al, 1987; Pachnis et al, 1993). For examples, tyrosine kinase c-Src mRNA is transiently expressed between days E8–10 of mouse gestation and gradually decreases thereafter (Slamon & Cline, 1984). In human cancers, Src tyrosine activity is correlated with Src protein expression (Verbeek et al, 1996).

Proto-oncogene expression during development can be modulated by epigenetic states. For instance, the repressive histone mark H3K27me3 and active histone mark H3K4me3 both are enriched at the promoter of proto-oncogenes c-SRC, AKT1, and MYB in human ES cells, but only the active histone mark H3K4me3 is enriched in the K562 cancer cell line (ENCODE). (Ram et al, 2011). While inactivation of tumor suppressor genes such as CDKN2A and TP53 is observed in many human cancers, including PDAC (Nigro et al, 1989; Caldas et al, 1994), genes encoding histone modifying enzymes are often mutated in cancer (Dawson & Kouzarides, 2012; Kadoch et al, 2013) and such enzymes can bind to and repress the CDKN2A locus (Bracken et al, 2007). Moreover, the conformation status of p53 can be changed in the pluripotent state. Undifferentiated ES cells express high levels of p53 in a wild-type conformation, but there is a shift in the conformational status of p53 to a mutant form upon RA-induced differentiation (Sabapathy et al, 1997). Mouse ES cells harboring oncogenic mutant alleles of p53 maintain pluripotency and are benign, with normal karyotypes compared to ES cells, when the p53 gene is knocked out (Rivlin et al, 2014).

The embryonic stem cell microenvironment, presumably mimicking that in the blastocyst, can contribute to the suppression of uncontrolled cell growth in the pluripotent state; this helps to keep the balance between self-renewal and differentiation. Aggressive melanoma cells were reprogrammed into melanocyte-like cells and invasiveness was reduced, at least in part, by culturing the cells on Matrigel that was conditioned by human ES cells, suggesting suppressive, anti-invasive cues associated with the huES microenvironment (Postovit et al, 2006). The aggressive melanoma and breast carcinoma cells express Nodal, which is essential for human ES cell pluripotency, yet these cancers did not express Lefty, an inhibitor of Nodal, which is expressed in human ES cells. Exposure of the cancer cell lines to ES-conditioned Matrigel resulted in a decrease in tumorigenesis accompanied by a reduction in clonogenicity and an increase in apoptosis, directly associated with secretion of Lefty from huES cells (Postovit et al, 2008).

In conclusion, early developmental signals naturally regulate proto-oncogenes so that their expression can be suppressed until an appropriate developmental stage where the genes function. Concordantly, the changing early embryonic environment and the mimic of such environments during ES cell culture can suppress oncogenic phenotypes of cancer-derived cells.

Reprogramming of somatic cells to pluripotency by OSKM

Human and mouse somatic cells (such as fibroblasts, blood cells, etc.) can be reprogrammed into a pluripotent ES-like cells, called induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells, by the ectopic expression of transcription factors such as Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc (OSKM) (Takahashi & Yamanaka, 2006). As this method does not need oocytes or blastocysts that are used for SCNT, it is a much more accessible technique and it side-steps ethical issues associated with using early human embryos. The pluripotency of human iPS cells can be validated by cell markers, genomic RNA expression profiles, epigenetic profiles, and teratoma assays; the latter being when (e.g., human) iPS cells are injected subcutaneously into mice that are genetically deficient in innate and acquired immunity (e.g., NOD-SCID (Shultz et al, 2005)). Details of iPS cell generation and use are discussed elsewhere in this issue.

Reprogramming of cancer cells to pluripotency or near-pluripotency by OSKM

In the first experiments on cancer reprogramming by SCNT described above, only a subset of cancer cell types could be reprogrammed to pluripotency. Despite the remarkable demonstration of the potential dominance of the pluripotent state over cancer, major questions remained. Are there particular cancer mutations that allow or block the ability of a cancer cells to be reprogrammed to pluripotency? Does such ability to be reprogrammed relate to the tissue type of the cancer? At what stage of using re-differentiation of the reprogrammed cancer cells does the cancer genome regain dominance over the cell phenotype? Can understanding the transition between pluripotency and cancer provide new insight into how to control the growth of cancer cells? Now that the relatively simple iPS technology can be applied to reprogram cancer cells, independent of oocytes and blastocysts, these questions have been revisited.

Reprogramming of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML)

The initial chronic phase of CML, which originates from hematopoietic stem cells of the bone marrow, is caused by a BCR-ABL fusion mutation that drives cell expansion, while the CML clones retain differentiation potential (Melo & Barnes, 2007). The chronic phase of CML progresses into an accelerated phase, followed by the blast crisis, terminal phase of CML upon acquisition of a second lesion. Once CML reaches the blast crisis stage, the cells lose the ability to differentiate and immature leukemia cells overgrow. Based upon the dependency of CML on BCR-ABL activated tyrosine kinase, tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as imatinib improved the long-term survival rate of CML patients. However, the inhibitor cannot completely eradicate CML cells and often lead to the recurrence of CML clones after its discontinuation (Melo & Barnes, 2007). Can CML in the terminal blast crisis stage be reprogrammed into iPS cells? If so, can CML-iPS cells recapitulate the initial chronic phase of CML, which has differentiation potential? Can be the dependency of CML on BCR-ABL signaling be altered?

Carette et al (2010) reprogrammed a cell line derived from blast crisis stage CML by infecting with a retrovirus expressing OSKM. Subcutaneous injection of the resulting CML-iPS cells into NOD-SCID mice revealed teratomas which contained cells of three germ layers, indicating pluripotency. During in vitro differentiation, the CML-iPS cells were able to differentiate into cells expressing the pan-T cell marker CD43+ and the hematopoietic lineage marker CD45+, as well as the stem cell marker CD34+, demonstrating a restoration of differentiation potential into hematopoietic lineages. The loss of the CML phenotype in CML-iPS cells and the recovery of differentiation can be viewed as a recapitulation of the chronic phase of CML, despite starting with blast crisis stage CML-iPS cells.

Interestingly, whereas parental CML cell lines were dependent on the BCR-ABL pathway, the CML-iPS cell lines were independent of BCR-ABL signaling and showed resistance to imatinib, an inhibitor of BCR-ABL signaling (Carette et al, 2010). The loss of BCR-ABL dependency was also observed in cells differentiated in vitro into neuronal or fibroblast-like cells. Yet when the cells were differentiated in vitro to hematopoietic lineage cells, they became sensitive to imatinib, suggesting that the recovery of oncogenic dependency as the CML-iPS cells underwent hematopoietic differentiation. Thus, oncogenic mutations can be dynamically expressed when cancer cells are converted to pluripotency and then re-differentiated.

Similar observations were seen by another group that generated iPS cells from primary CD34+ cells which were isolated from bone marrow mononuclear cells of a CML chronic phase patient, by retroviral infection with OSKM (Kumano et al, 2012). The CML-iPS cells underwent normal hematopoiesis during in vitro differentiation. The differentiated hematopoietic progenitors (CD34+CD45+) from CML-iPS cells produced colonies of mature erythroid cells, granulocyte–macrophage cells, or mix lineages with a distribution of colony size, morphologies, and kinetics of growth and maturation that was similar to non-cancer iPS cells. The CML-iPS-derived hematopoietic progenitors did not show a CML phenotype in vivo, when intravenously engrafted into NSG mice receiving minimal irradiation. Whereas the parental CD34+ cells responded to imatinib, the CML-iPS derivatives and immature CD34+CD38−CD45+CD90+ cells derived from the CML-iPS cells were not sensitive to imatinib. Yet mature hematopoietic cells (CD34−CD45+) derived from the CML-iPS cells restored their sensitivity to imatinib. Given that the expression of the proto-oncogene C-ABL is high at mouse embryonic day 10 when the first definitive hematopoietic stem cells are generated (Muller et al, 1982; Sanchez et al, 1996), the CML-iPS cells, corresponding to mouse blastocyst cells at embryonic day 3–5, may express regulatory factors that suppress C-ABL signaling. Thus, understanding the underlying mechanisms that counteract BCR-ABL signaling in CML-iPS cells and their immature, newly differentiated progeny could provide insight into the resistant to imatinib. Furthermore, it may be possible to screen new drugs that can inhibit CML clones at this stage and then treat CML patients with such drugs in combination with classical inhibitors. Taken together, these studies show how reprogramming to pluripotency can modulate oncogene expression and recapitulate the initial chronic phase of CML.

Reprogramming of gastrointestinal cancer cell lines

Miyoshi et al (2010) hypothesized that reprogramming of gastrointestinal cancer cell lines into iPS would allow the cells to undergo differentiation and enhanced sensitivity to therapeutics. The iPS cells arising in their experiments were capable of differentiation into cells of the three germ layers in vitro. Interestingly, while the parental gastrointestinal cancer cell lines generated tumors within four months of injection into NOD/SCID mice, such tumorigenesis was not seen with the differentiated cells arising from the iPS cells derived from the cell lines. In accord with these observations, the gastrointestinal cancer-derived iPS cells, upon differentiation, expressed higher levels of the tumor suppressor genes p16 Ink4α and p53, slower proliferation and were sensitive to differentiation-inducing treatment (Miyoshi et al, 2010). These findings show that the pluripotency state imposed by the OSKM factors can partially suppress the cancer phenotype in the gastrointestinal cell lines.

Reprogramming of glioblastoma (GBM) neural stem cells and human sarcoma

To determine whether cancer-specific epigenetic changes can be altered or erased by reprogramming and how such might correlate with transcriptional changes and suppression of malignancy, primary GBM-derived neural stem cells (GNS) were reprogrammed using piggyBac transposon vectors expressing OCT4 and KLF4 (Stricker et al, 2013). Widespread resetting of epigenetic methylation occurred in the GNS-iPS cells in cancer-specific methylation variable positions (cMVPs) and also at the GBM tumor suppressor genes CDKN1C (cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1C) and TES and was associated with the genes' derepression. Interestingly, teratomas from the GNS-iPS cells generated compact and non-infiltrative cells of all three germ layers. The majority of cells in the teratomas developed into highly proliferating neural progenitors, showing epigenetic memory of the cell type used to generate iPS cells.

Primary GBM develops rapidly from neural precursors, apparently without clinical or histopathological evidence of less malignant precursor lesions (Ohgaki & Kleihues, 2013). In accordance with the human cancer, neural progenitor cells that were differentiated from iPS-GNS recapitulated aggressive glioblastoma when transplanted into the adult mouse brain (Stricker et al, 2013). In contrast, non-neural mesodermal progenitors, differentiated from two independent GNS-iPS clones in vitro, sustained the expression of TES and CDKN1C formed benign tumors and failed to infiltrate the surrounding brain (Stricker et al, 2013).

To determine whether human cancer cells can be reprogrammed to pluripotency and then terminally differentiated with concomitant loss of tumorigenicity, human sarcoma cell lines were reprogrammed by infecting with human OSKM along with NANOG and LIN28 (Zhang et al, 2013). In xenograft assays in non-immune mice, the reprogrammed sarcoma cells formed tumors at slower rates than their parental cell lines. The sarcoma-iPS-derived tumors were of lower grade, exhibited more necrosis, reduced staining for a marker of proliferation, and reduced expression of the vimentin mesenchymal marker than tumors from the sarcoma parental cell lines. Thus, reprogramming decreased the aggressiveness of the cancer compared to the cells' parental counterparts. All 32 oncogenes and 82 tumor suppressor genes whose promoter DNA was initially methylated, were demethylated as a result of reprogramming, indicating that the reprogramming process was accompanied by major epigenetic changes in growth- and cancer-related genes. By ANOVA of gene expression profiles and principal component analysis, the reprogrammed sarcoma cells, though only partially reprogrammed, were more like embryonic stem cells compared to mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and partially reprogrammed fibroblasts, demonstrating that the sarcoma cell line was de-differentiated into a pre-MSC state (Zhang et al, 2013).

The above studies with cancer cell lines showed that the pluripotency factors and the pluripotency state can suppress features of the cancer phenotype, restore differentiation potential, perturb epigenetics via DNA methylation, and alter cancer-related gene expression.

Reprogramming of human primary pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

Taking together the principles learned from SCNT and iPS studies of cancer cell lines, it seemed possible that generating iPS cells from primary human cancer cells would allow the cells to be propagated indefinitely in the pluripotent state and that, upon differentiation, a subset of the cells would undergo early developmental stages of the human cancer, thereby providing a live cell human model to study cancer progression (Kim et al, 2013). However, generating iPS had not been achieved with cancer epithelial cells from primary human adenocarcinomas. To test this idea, primary pancreatic epithelial cells isolated from pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) cells and normal cells at the margin of the tumors were reprogrammed by introducing OSKM. Colonies came up frequently from the margin epithelial cultures and very rarely from the cancer epithelial cultures. Once OSKM factors were suppressed, all ES-like colonies differentiated or died; therefore, low level of OSKM expression was retained and the ES-like colonies that arose were called ‘iPS-like', as they were apparently unable to completely sustain a pluripotency program.

One cancer iPS-like line, designated 10–22 cells, harbored classical PDAC mutations, including an activated KRAS allele, a CDKN2A heterozygous deletion, and decreased SMAD4 gene copy levels, as well as retained the gross chromosomal alterations seen in the parental, primary cancer epithelial cells, demonstrating that the PDAC-iPS line was derived from advanced PDAC cells (Kim et al, 2013). The 10-22, PDAC-iPS-like line differentiated into all three germ layer descendants during in vitro embryoid body differentiation, though neuronal lineages were under-represented. In vivo teratoma assays in non-immune mice showed that the 10–22 cells generated multiple germ layer tissues, but preferred to generate endodermal ductal structures. Notably, the ductal structures at 3 months resembled pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasias (PanIN), regarded as a potential precursor to PDAC, and by 9 months the cells progressed to the invasive stage. By contrast, an isogenic line of iPS-like cells derived from the tumor margin gave rise to ductal teratomas, but not PanINs or invasive ductal features. Thus, reprogramming of the PDAC created an experimental model in which human PDAC progression could be studied in live cells.

A major cause for the lethality of PDAC is that there are no reliable biomarkers or clinical phenotypes of the early stages of the disease. To discover potential biomarkers for early PDAC progression, PanIN lesions at 3 months were isolated from non-immune mouse teratomas and cultured in serum-free medium as organoids (Kim et al, 2013). After 6 days of culture, the medium was harvested and subjected to mass spectroscopic analysis, in order to discover protein markers that are secreted or released from early-stage human PDAC. By subtracting the secreted and released proteins of the organoids from such proteins of contralateral control tissue and of the 10–22 cells grown under pluripotency conditions, 107 proteins specific to the PanIN-stage samples were discovered. Of these, 64% of released or secreted proteins were seen in databases of genes, proteins, and networks expressed within human PanIN and PDAC cells, further validating the PanIN status of the organoids derived from the 10–22 cell teratomas.

The proteins released or secreted from the PanIN organoids fell into three major networks, including interconnected networks for TGF-β and integrin signaling, and for the transcription factor HNF4α. Notably, HNF4a is not or barely expressed in normal pancreatic ductal cells, poorly expressed in the PanIN1 stage, but is activated in PanIN2 and PanIN3 stages, invasive stages, and in early, well-differentiated human pancreatic cancer (Kim et al, 2013). HNF4a then decreases markedly and becomes undetectable in advanced or undifferentiated PDAC. Thus, being able to reconstitute PDAC progression with 10–22 cells revealed the activation of an HNF4a network distinctive for the late PanIN stages and well-differentiated PDAC; this network activated during PDAC progression would have been missed in studies of late-stage tumor cells.

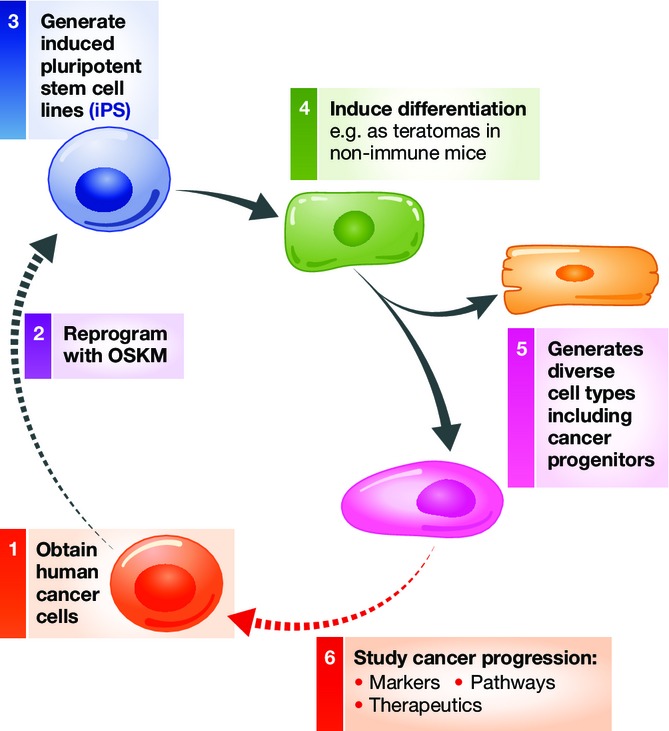

In conclusion, although handful of reports have demonstrated the reprogramming of cancer by iPS technology and only a subset of cancer cells are amenable to the process, common lessons can be drawn. (1) The differentiation potential of the cancer cells can be restored, at least in part. (2) Epigenetic states are altered markedly during reprogramming to pluripotency or near-pluripotency. (3) The reprogrammed cells exhibit a reduced aggressive cancer phenotype in teratoma assays, which may be concomitant with suppression of oncogenes from the original cancer and activation of tumor suppressor genes. (4) The reprogrammed cells can re-acquire the cancer phenotype when they differentiate into the lineage from which the iPS line was derived. Indeed, the iPS or iPS-like reprogrammed cancer cells retain a propensity to do so, compared to other lineages. (5) The iPS-like reprogrammed cancer cells can be used to study the progression of the cancer phenotype (Fig2).

Figure 2.

Cancer cell reprogramming by iPS and recapitulation of cancer progression. Scenario for developing iPS lines from human cancer cells (1–3), inducing their differentiation to generate cancer progenitors (4–5), and using the cancer progenitors to study features of cancer progression (6). By this means, late-stage human cancers can be reprogrammed to recapitulate early-stage disease and progression for discovering markers, pathways, and therapeutics.

Questions for the future

Many questions remain. How do the pluripotency factors and reprogramming process partially suppress the cancer phenotype? How might such suppression be restricted to the lineage from which the cancer iPS cells were derived? During the differentiation of cancer iPS cells, how do the cells harboring the late-stage cancer genome undergo disease progression, as opposed to immediately developing the late-stage, parental cancer phenotype? What is the basis by which cancer iPS lines are so difficult to generate? How can the process be improved, to create more models for human cancer progression? While definitive answers to these questions are not in hand, hints about underlying mechanisms are arising in different areas, as discussed next.

Control of cancer versus pluripotency

As for SCNT, iPS technology was able to reprogram a subset of cancer cells to the pluripotent or near-pluripotent state and restore differentiation potential to the cells. Pluripotent ES cells and iPS cells have epigenetic features that may be reciprocal to those in cancer cells (Suva et al, 2013). For instance, comprehensive high-throughput relative methylation analysis demonstrated the existence of two independent epigenetic mechanisms for cell reprogramming and tumorigenesis. Hypomethylated, ‘differentially methylated regions’ (DMRs) that can occur in iPS reprogramming were hypermethylated DMRs in colon cancer (Doi et al, 2009). Seventy-seven percent of cancer-specific methylation variable positions (cMVPs) were hypermethylated and 23% were hypomethylated in GBM neural stem cell (GNS) (Stricker et al, 2013). More than 44% of these cMVPs were reset during reprogramming of GNS to GNS-iPS along with a majority of targets of the Polycomb complex (Stricker et al, 2013). Furthermore, oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes can become demethylated as a result of iPS reprogramming, which is the opposite of the methylation of tumor suppressor genes seen during cancer progression (Zhang et al, 2013). ATP-dependent SWI/SNF complexes are considered to be tumor suppressors, since recurrent mutations of Brg1 subunits of the complex have been observed in various human cancers (Wilson & Roberts, 2011), including pancreatic cancer (Jones et al, 2008; Shain et al, 2012). The loss of the Brg1 BAF complex promoted the formation of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms and PDAC (von Figura et al, 2014). By contrast, overexpression of Brg1 and Baf155 components of the BAF complex, along with OSKM, enhances reprogramming to iPS (Singhal et al, 2010). Together, these findings show that common factors and epigenetic features can differentially elicit tumor formation or reprogramming to pluripotency.

While the coordinate, ectopic expression of OSKM induces reprogramming of somatic cells pluripotency (Takahashi & Yamanaka, 2006), activation of individual pluripotency factors can contribute to tumorigenesis. For instance, the inducible expression of OCT4 in mice initiated dysplasia by preventing the differentiation of multipotent lineages (Hochedlinger et al, 2005). The ectopic expression of OCT4 in human melanoma cells produced a more aggressive, cancer stem cell-like melanoma (Kumar et al, 2012). Furthermore, whereas reprogramming to pluripotency in the mouse can produce well-differentiated teratomas (Abad et al, 2013), partial reprogramming in mice yields tumors (Ohnishi et al, 2014). These findings indicate that the pluripotency transcription factors are integrated into networks that govern cancer phenotypes.

An unexplained feature of the use of cancer-derived iPS cells is that the cells harbor the mutations of the late-stage cancer from which the iPS cells were derived, but, as described above, the cancer iPS cells can exhibit disease progression; that is, not simply return to the late-stage phenotype from which they were derived. It follows that the disease progression exhibited by the models may not reflect that seen during the sequential accumulation of cancer driver mutations as might occur in natural tumor development. Yet in human PDAC progression, PanIN2 cells can harbor somatic mutations required for PDAC development, but it can take years for the cells to acquire metastatic activity (Yachida et al, 2010; Murphy et al, 2013). Thus, even during natural PDAC tumor development, epigenetic or extrinsic factors may be crucial for progression. The attenuation of such factors may occur transiently during reprogramming to pluripotency, and the release from pluripotency can thus mirror the progression to the cancer phenotype seen in vivo.

Low efficiency of reprogramming cancer cells to pluripotency

Cancer cells are reprogrammed very inefficiently and only subset of cancers are amenable to reprogramming. Certain mutations might make cancer cells refractory to reprogramming; that is, ‘non-suppressible’ by pluripotency. One iPS line out of 8 derived from PDAC contained the primary PDAC driver allele KRASG12D, even though 78% of starting primary cancer epithelial cells contained KRASG12D (Kim et al, 2013). Conceivably, secondary mutations arising during iPS formation allowed the KRASG12D cells to be reprogrammed. Furthermore, aneuploidy in cancer could cause the cellular stress responses such as activation of p53 through the stress kinase p38 (Thompson & Compton, 2010), thus possibly impeding reprogramming. PDAC epithelial cells from patients pre-treated with radiation did not produce any iPS colonies, perhaps due to senescence induced by irradiation and DNA damage (J.K. and K.S.Z, unpublished observations). Given that many cancer patients are treated with chemotherapy and irradiation prior to surgical resection, such treatments may prevent the creation of iPS lines.

The apparent preference for pluripotent cells to regenerate the cancer type from which they were derived reflects the tendency of iPS cell lines to preferentially differentiate into their lineages of origin (Bar-Nur et al, 2011; Kim et al, 2011). This ‘deficiency’ in exhibiting equal pluripotency for all cell lineages can be an advantage in developing human cell models of cancer progression, whereby the cancer iPS lines preferentially recapitulate stages of the cancer type of interest. Thus, despite the difficulties and caveats in generating human cancer iPS models, the examples covered in this review provide new insights into disease progression. It is hoped that a better understanding of how to create iPS cells from human cancers, and epithelial cancers in particular, will provide more opportunities to model and understand other types of solid tumors.

Acknowledgments

Research on the project is supported by NIH grant R37GM36477 and funding from the Abramson Cancer Center with Penn Medicine to K.S.Z.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Abad M, Mosteiro L, Pantoja C, Canamero M, Rayon T, Ors I, Grana O, Megias D, Dominguez O, Martinez D, Manzanares M, Ortega S, Serrano M. Reprogramming in vivo produces teratomas and iPS cells with totipotency features. Nature. 2013;502:340–345. doi: 10.1038/nature12586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ablain J, Zon LI. Of fish and men: using zebrafish to fight human diseases. Trends Cell Biol. 2013;23:584–586. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2013.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamson ED. Oncogenes in development. Development. 1987;99:449–471. doi: 10.1242/dev.99.4.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arteaga CL, Adamson PC, Engelman JA, Foti M, Gaynor RB, Hilsenbeck SG, Limburg PJ, Lowe SW, Mardis ER, Ramsey S, Rebbeck TR, Richardson AL, Rubin EH, Weiner GJ, Sweeney SM, Honey K, Bachen J, Driscoll P, Hobin J, Ingram J, et al. AACR cancer progress report 2014. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:S1–S112. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Nur O, Russ HA, Efrat S, Benvenisty N. Epigenetic memory and preferential lineage-specific differentiation in induced pluripotent stem cells derived from human pancreatic islet Beta cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;9:17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begley CG, Ellis LM. Drug development: raise standards for preclinical cancer research. Nature. 2012;483:531–533. doi: 10.1038/483531a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blelloch RH, Hochedlinger K, Yamada Y, Brennan C, Kim M, Mintz B, Chin L, Jaenisch R. Nuclear cloning of embryonal carcinoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:13985–13990. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405015101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bracken AP, Kleine-Kohlbrecher D, Dietrich N, Pasini D, Gargiulo G, Beekman C, Theilgaard-Monch K, Minucci S, Porse BT, Marine JC, Hansen KH, Helin K. The Polycomb group proteins bind throughout the INK4A-ARF locus and are disassociated in senescent cells. Genes Dev. 2007;21:525–530. doi: 10.1101/gad.415507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun AC. A demonstration of the recovery of the crown-gall tumor cell with the use of complex tumors of single-cell origin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1959;45:932–938. doi: 10.1073/pnas.45.7.932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldas C, Hahn SA, da Costa LT, Redston MS, Schutte M, Seymour AB, Weinstein CL, Hruban RH, Yeo CJ, Kern SE. Frequent somatic mutations and homozygous deletions of the p16 (MTS1) gene in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Nat Genet. 1994;8:27–32. doi: 10.1038/ng0994-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantley LC, Dalton WS, DuBois RN, Finn OJ, Futreal PA, Golub TR, Hait WN, Lozano G, Maris JM, Nelson WG, Sawyers CL, Schreiber SL, Spitz MR, Steeg PS. AACR cancer progress report 2012. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:S1–S100. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carette JE, Pruszak J, Varadarajan M, Blomen VA, Gokhale S, Camargo FD, Wernig M, Jaenisch R, Brummelkamp TR. Generation of iPSCs from cultured human malignant cells. Blood. 2010;115:4039–4042. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-231845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin L, Tam A, Pomerantz J, Wong M, Holash J, Bardeesy N, Shen Q, O'Hagan R, Pantginis J, Zhou H, Horner JW, 2nd, Cordon-Cardo C, Yancopoulos GD, DePinho RA. Essential role for oncogenic RAS in tumour maintenance. Nature. 1999;400:468–472. doi: 10.1038/22788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson MA, Kouzarides T. Cancer epigenetics: from mechanism to therapy. Cell. 2012;150:12–27. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DePinho RA. The age of cancer. Nature. 2000;408:248–254. doi: 10.1038/35041694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doi A, Park IH, Wen B, Murakami P, Aryee MJ, Irizarry R, Herb B, Ladd-Acosta C, Rho J, Loewer S, Miller J, Schlaeger T, Daley GQ, Feinberg AP. Differential methylation of tissue- and cancer-specific CpG island shores distinguishes human induced pluripotent stem cells, embryonic stem cells and fibroblasts. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1350–1353. doi: 10.1038/ng.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteller M. Cancer epigenomics: DNA methylomes and histone-modification maps. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:286–298. doi: 10.1038/nrg2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Figura G, Fukuda A, Roy N, Liku ME, Morris Iv JP, Kim GE, Russ HA, Firpo MA, Mulvihill SJ, Dawson DW, Ferrer J, Mueller WF, Busch A, Hertel KJ, Hebrok M. The chromatin regulator Brg1 suppresses formation of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16:255–267. doi: 10.1038/ncb2916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao D, Vela I, Sboner A, Iaquinta PJ, Karthaus WR, Gopalan A, Dowling C, Wanjala JN, Undvall EA, Arora VK, Wongvipat J, Kossai M, Ramazanoglu S, Barboza LP, Di W, Cao Z, Zhang QF, Sirota I, Ran L, MacDonald TY, et al. Organoid cultures derived from patients with advanced prostate cancer. Cell. 2014;159:176–187. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurdon JB, Elsdale TR, Fischberg M. Sexually mature individuals of Xenopus laevis from the transplantation of single somatic nuclei. Nature. 1958;182:64–65. doi: 10.1038/182064a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochedlinger K, Blelloch R, Brennan C, Yamada Y, Kim M, Chin L, Jaenisch R. Reprogramming of a melanoma genome by nuclear transplantation. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1875–1885. doi: 10.1101/gad.1213504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochedlinger K, Yamada Y, Beard C, Jaenisch R. Ectopic expression of Oct-4 blocks progenitor-cell differentiation and causes dysplasia in epithelial tissues. Cell. 2005;121:465–477. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishizawa K, Rasheed ZA, Karisch R, Wang Q, Kowalski J, Susky E, Pereira K, Karamboulas C, Moghal N, Rajeshkumar NV, Hidalgo M, Tsao M, Ailles L, Waddell TK, Maitra A, Neel BG, Matsui W. Tumor-initiating cells are rare in many human tumors. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:279–282. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones S, Zhang X, Parsons DW, Lin JC, Leary RJ, Angenendt P, Mankoo P, Carter H, Kamiyama H, Jimeno A, Hong SM, Fu B, Lin MT, Calhoun ES, Kamiyama M, Walter K, Nikolskaya T, Nikolsky Y, Hartigan J, Smith DR, et al. Core signaling pathways in human pancreatic cancers revealed by global genomic analyses. Science. 2008;321:1801–1806. doi: 10.1126/science.1164368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadoch C, Hargreaves DC, Hodges C, Elias L, Ho L, Ranish J, Crabtree GR. Proteomic and bioinformatic analysis of mammalian SWI/SNF complexes identifies extensive roles in human malignancy. Nat Genet. 2013;45:592–601. doi: 10.1038/ng.2628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Hoffman JP, Alpaugh RK, Rhim AD, Reichert M, Stanger BZ, Furth EE, Sepulveda AR, Yuan CX, Won KJ, Donahue G, Sands J, Gumbs AA, Zaret KS. An iPSC line from human pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma undergoes early to invasive stages of pancreatic cancer progression. Cell Rep. 2013;3:2088–2099. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.05.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K, Zhao R, Doi A, Ng K, Unternaehrer J, Cahan P, Huo H, Loh YH, Aryee MJ, Lensch MW, Li H, Collins JJ, Feinberg AP, Daley GQ. Donor cell type can influence the epigenome and differentiation potential of human induced pluripotent stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:1117–1119. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumano K, Arai S, Hosoi M, Taoka K, Takayama N, Otsu M, Nagae G, Ueda K, Nakazaki K, Kamikubo Y, Eto K, Aburatani H, Nakauchi H, Kurokawa M. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells from primary chronic myelogenous leukemia patient samples. Blood. 2012;119:6234–6242. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-07-367441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar SM, Liu S, Lu H, Zhang H, Zhang PJ, Gimotty PA, Guerra M, Guo W, Xu X. Acquired cancer stem cell phenotypes through Oct4-mediated dedifferentiation. Oncogene. 2012;31:4898–4911. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledford H. Translational research: 4 ways to fix the clinical trial. Nature. 2011;477:526–528. doi: 10.1038/477526a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Connelly MC, Wetmore C, Curran T, Morgan JI. Mouse embryos cloned from brain tumors. Cancer Res. 2003;63:2733–2736. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Nadauld L, Ootani A, Corney DC, Pai RK, Gevaert O, Cantrell MA, Rack PG, Neal JT, Chan CW, Yeung T, Gong X, Yuan J, Wilhelmy J, Robine S, Attardi LD, Plevritis SK, Hung KE, Chen CZ, Ji HP, et al. Oncogenic transformation of diverse gastrointestinal tissues in primary organoid culture. Nat Med. 2014;20:769–777. doi: 10.1038/nm.3585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin TP. Microinjection of mouse eggs. Science. 1966;151:333–337. doi: 10.1126/science.151.3708.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Leach SD. Zebrafish models for cancer. Annu Rev Pathol. 2011;6:71–93. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinnell RG, Deggins BA, Labat DD. Transplantation of pluripotential nuclei from triploid frog tumors. Science. 1969;165:394–396. doi: 10.1126/science.165.3891.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melo JV, Barnes DJ. Chronic myeloid leukaemia as a model of disease evolution in human cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:441–453. doi: 10.1038/nrc2147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mintz B, Illmensee K. Normal genetically mosaic mice produced from malignant teratocarcinoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1975;72:3585–3589. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.9.3585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyoshi N, Ishii H, Nagai K, Hoshino H, Mimori K, Tanaka F, Nagano H, Sekimoto M, Doki Y, Mori M. Defined factors induce reprogramming of gastrointestinal cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:40–45. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912407107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller R, Slamon DJ, Tremblay JM, Cline MJ, Verma IM. Differential expression of cellular oncogenes during pre- and postnatal development of the mouse. Nature. 1982;299:640–644. doi: 10.1038/299640a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy SJ, Hart SN, Lima JF, Kipp BR, Klebig M, Winters JL, Szabo C, Zhang L, Eckloff BW, Petersen GM, Scherer SE, Gibbs RA, McWilliams RR, Vasmatzis G, Couch FJ. Genetic alterations associated with progression from pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia to invasive pancreatic tumor. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:1098–1109. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.07.049. e1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nardella C, Lunardi A, Patnaik A, Cantley LC, Pandolfi PP. The APL paradigm and the “co-clinical trial” project. Cancer Discov. 2011;1:108–116. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen LV, Vanner R, Dirks P, Eaves CJ. Cancer stem cells: an evolving concept. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:133–143. doi: 10.1038/nrc3184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigro JM, Baker SJ, Preisinger AC, Jessup JM, Hostetter R, Cleary K, Bigner SH, Davidson N, Baylin S, Devilee P, Glover T, Collins FS, Weslon A, Modali R, Harris CC, Vogelstein B. Mutations in the p53 gene occur in diverse human tumour types. Nature. 1989;342:705–708. doi: 10.1038/342705a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohgaki H, Kleihues P. The definition of primary and secondary glioblastoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:764–772. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohnishi K, Semi K, Yamamoto T, Shimizu M, Tanaka A, Mitsunaga K, Okita K, Osafune K, Arioka Y, Maeda T, Soejima H, Moriwaki H, Yamanaka S, Woltjen K, Yamada Y. Premature termination of reprogramming in vivo leads to cancer development through altered epigenetic regulation. Cell. 2014;156:663–677. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachnis V, Mankoo B, Costantini F. Expression of the c-ret proto-oncogene during mouse embryogenesis. Development. 1993;119:1005–1017. doi: 10.1242/dev.119.4.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeifer-Ohlsson S, Goustin AS, Rydnert J, Wahlstrom T, Bjersing L, Stehelin D, Ohlsson R. Spatial and temporal pattern of cellular myc oncogene expression in developing human placenta: implications for embryonic cell proliferation. Cell. 1984;38:585–596. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90513-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeifer-Ohlsson S, Rydnert J, Goustin AS, Larsson E, Betsholtz C, Ohlsson R. Cell-type-specific pattern of myc protooncogene expression in developing human embryos. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:5050–5054. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.15.5050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postovit LM, Seftor EA, Seftor RE, Hendrix MJ. A three-dimensional model to study the epigenetic effects induced by the microenvironment of human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2006;24:501–505. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postovit LM, Margaryan NV, Seftor EA, Kirschmann DA, Lipavsky A, Wheaton WW, Abbott DE, Seftor RE, Hendrix MJ. Human embryonic stem cell microenvironment suppresses the tumorigenic phenotype of aggressive cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:4329–4334. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800467105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ram O, Goren A, Amit I, Shoresh N, Yosef N, Ernst J, Kellis M, Gymrek M, Issner R, Coyne M, Durham T, Zhang X, Donaghey J, Epstein CB, Regev A, Bernstein BE. Combinatorial patterning of chromatin regulators uncovered by genome-wide location analysis in human cells. Cell. 2011;147:1628–1639. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rangarajan A, Weinberg RA. Opinion: comparative biology of mouse versus human cells: modelling human cancer in mice. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:952–959. doi: 10.1038/nrc1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivlin N, Katz S, Doody M, Sheffer M, Horesh S, Molchadsky A, Koifman G, Shetzer Y, Goldfinger N, Rotter V, Geiger T. Rescue of embryonic stem cells from cellular transformation by proteomic stabilization of mutant p53 and conversion into WT conformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:7006–7011. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1320428111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabapathy K, Klemm M, Jaenisch R, Wagner EF. Regulation of ES cell differentiation by functional and conformational modulation of p53. EMBO J. 1997;16:6217–6229. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.20.6217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez MJ, Holmes A, Miles C, Dzierzak E. Characterization of the first definitive hematopoietic stem cells in the AGM and liver of the mouse embryo. Immunity. 1996;5:513–525. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80267-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shain AH, Giacomini CP, Matsukuma K, Karikari CA, Bashyam MD, Hidalgo M, Maitra A, Pollack JR. Convergent structural alterations define SWItch/Sucrose NonFermentable (SWI/SNF) chromatin remodeler as a central tumor suppressive complex in pancreatic cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:E252–E259. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114817109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma SV, Haber DA, Settleman J. Cell line-based platforms to evaluate the therapeutic efficacy of candidate anticancer agents. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:241–253. doi: 10.1038/nrc2820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shultz LD, Lyons BL, Burzenski LM, Gott B, Chen X, Chaleff S, Kotb M, Gillies SD, King M, Mangada J, Greiner DL, Handgretinger R. Human lymphoid and myeloid cell development in NOD/LtSz-scid IL2R gamma null mice engrafted with mobilized human hemopoietic stem cells. J Immunol. 2005;174:6477–6489. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.10.6477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singhal N, Graumann J, Wu G, Arauzo-Bravo MJ, Han DW, Greber B, Gentile L, Mann M, Scholer HR. Chromatin-remodeling components of the BAF complex facilitate reprogramming. Cell. 2010;141:943–955. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slamon DJ, Cline MJ. Expression of cellular oncogenes during embryonic and fetal development of the mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:7141–7145. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.22.7141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stricker SH, Feber A, Engstrom PG, Caren H, Kurian KM, Takashima Y, Watts C, Way M, Dirks P, Bertone P, Smith A, Beck S, Pollard SM. Widespread resetting of DNA methylation in glioblastoma-initiating cells suppresses malignant cellular behavior in a lineage-dependent manner. Genes Dev. 2013;27:654–669. doi: 10.1101/gad.212662.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suva ML, Riggi N, Bernstein BE. Epigenetic reprogramming in cancer. Science. 2013;339:1567–1570. doi: 10.1126/science.1230184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tentler JJ, Tan AC, Weekes CD, Jimeno A, Leong S, Pitts TM, Arcaroli JJ, Messersmith WA, Eckhardt SG. Patient-derived tumour xenografts as models for oncology drug development. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2012;9:338–350. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2012.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson SL, Compton DA. Proliferation of aneuploid human cells is limited by a p53-dependent mechanism. J Cell Biol. 2010;188:369–381. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200905057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuveson DA, Jacks T. Technologically advanced cancer modeling in mice. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2002;12:105–110. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(01)00272-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbeek BS, Vroom TM, Adriaansen-Slot SS, Ottenhoff-Kalff AE, Geertzema JG, Hennipman A, Rijksen G. c-Src protein expression is increased in human breast cancer. An immunohistochemical and biochemical analysis. J Pathol. 1996;180:383–388. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199612)180:4<383::AID-PATH686>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ZQ, Kiefer F, Urbanek P, Wagner EF. Generation of completely embryonic stem cell-derived mutant mice using tetraploid blastocyst injection. Mech Dev. 1997;62:137–145. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(97)00655-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ZY, Chen Z. Acute promyelocytic leukemia: from highly fatal to highly curable. Blood. 2008;111:2505–2515. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-102798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson DG, Bailes JA, McMahon AP. Expression of the proto-oncogene int-1 is restricted to specific neural cells in the developing mouse embryo. Cell. 1987;50:79–88. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90664-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson BG, Roberts CW. SWI/SNF nucleosome remodellers and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:481–492. doi: 10.1038/nrc3068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu M, Jung L, Cooper AB, Fleet C, Chen L, Breault L, Clark K, Cai Z, Vincent S, Bottega S, Shen Q, Richardson A, Bosenburg M, Naber SP, DePinho RA, Kuperwasser C, Robinson MO. Dissecting genetic requirements of human breast tumorigenesis in a tissue transgenic model of human breast cancer in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:7022–7027. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811785106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yachida S, Jones S, Bozic I, Antal T, Leary R, Fu B, Kamiyama M, Hruban RH, Eshleman JR, Nowak MA, Velculescu VE, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA. Distant metastasis occurs late during the genetic evolution of pancreatic cancer. Nature. 2010;467:1114–1117. doi: 10.1038/nature09515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Cruz FD, Terry M, Remotti F, Matushansky I. Terminal differentiation and loss of tumorigenicity of human cancers via pluripotency-based reprogramming. Oncogene. 2013;32:2249–2260. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.237. 2260 e2241–2221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]