Abstract

Sepsis-associated acute kidney injury (SA-AKI) is linked to high morbidity and mortality. Thus far singular approaches to target specific pathways known to contribute to the pathogenesis of SA-AKI have failed. Because of the complexity of the pathogenesis of SA-AKI, a reassessment necessitates integrative approaches to therapeutics of SA-AKI that include general supportive therapies such as the use of vasopressors, fluids, antimicrobial and target specific and time dependent therapeutics. There has been recent progress in our understanding of the pathogenesis and treatment of SA-AKI including temporal nature of pro- and anti-inflammatory processes. In this review, we will discuss the clinical and experimental basis of emerging therapeutic approaches that focus on targeting early proinflammatory and late anti-inflammatory processes as well as therapeutics that may enhance cellular survival and recovery. Lastly we include ongoing clinical trials in sepsis.

Keywords: Inflammation, cytokines, therapeutics, septic shock

Introduction

Sepsis is one of the most common causes of acute kidney injury (AKI) accounting for nearly 50% of cases of AKI in the intensive care unit (ICU)1,2 and is the leading cause of death in the ICU3. There are about 200,000 annual deaths attributable to sepsis in the US4. There is a bi-directional relationship between sepsis and AKI with an increased incidence of sepsis even in patients who develop AKI due to non-septic etiologies5. Standard treatment approaches such as parenteral antibiotic therapy, fluid resuscitation, and administration of vasopressor agents have not been effective in significantly reducing the incidence of SA-AKI or its associated mortality2. Further, emergence of antibiotic-resistant microbes as well as the increased complexity of patients (additive comorbidities, advanced age and immunocompromised status) adds other dimensions to the problem and emphasizes the need to understand and devise novel therapeutic approaches to prevent and treat SA-AKI.

Traditional paradigm of sepsis-associated organ dysfunction and AKI has focused largely on specific cytokines and their modulation to improve outcomes in sepsis. Evidence from several studies published over the last two decades indicates that this singular approach is unlikely be effective to improve outcomes. For example, clinical trials focused on antagonizing single inflammatory cytokines including: anti-endotoxin (LPS, lipopolysaccharide), anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-1β and Toll-Like receptor (TLR) 4 inhibits have been unsuccessful6–8.

Based on pre-clinical and human studies, there has been significant recent progress in our understanding of novel pathways that are involved in the pathogenesis of SA-AKI. In this review, we will discuss preclinical studies that have a strong pathophysiological basis as well as recent ongoing clinical trials in sepsis and AKI. In particular understanding time-dependent processes and multiple targets suggests that successful outcomes may depend on an integrated approach to the treatment of sepsis (Table 1). Lastly, therapeutic targets such as TNF, IL-1β, TLRs etc have been described in recent reviews4,9 and will not be discussed here.

Table 1.

Therapeutic Targets in Septic AKI

Attenuating Early Inflammatory Response

|

Activating Late Immunity

|

Cellular Targets

|

Molecular mechanisms of recovery

|

Overview of Inflammation

The inflammatory response to sepsis and trauma remains controversial 10. Lewis Thomas was responsible for a paradigm shift by changing the focus from pathogens to the pathological dysregulated host response that serves as the basis for the clinical expression of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome11 and sepsis. The host responds to danger associated molecular patterns (DAMPS) or pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPS) such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS), flagellin, double-stranded RNA, and CpG DNA12 which are ligands for pattern recognition receptors, such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs), NOD-like receptors (NLRs) and RIG-I-like receptors (RLRs)13,14 that activate innate immunity. Early deaths are due typically to a hyper-inflammatory ‘cytokine storm’ response with clinical features such as fever, circulatory collapse, acidosis and hypercatabolism. The initial degree of inflammatory response depends on a number of factors that include pathogen virulence and bacterial load and the patient’s baseline comorbid conditions and genetic background15.

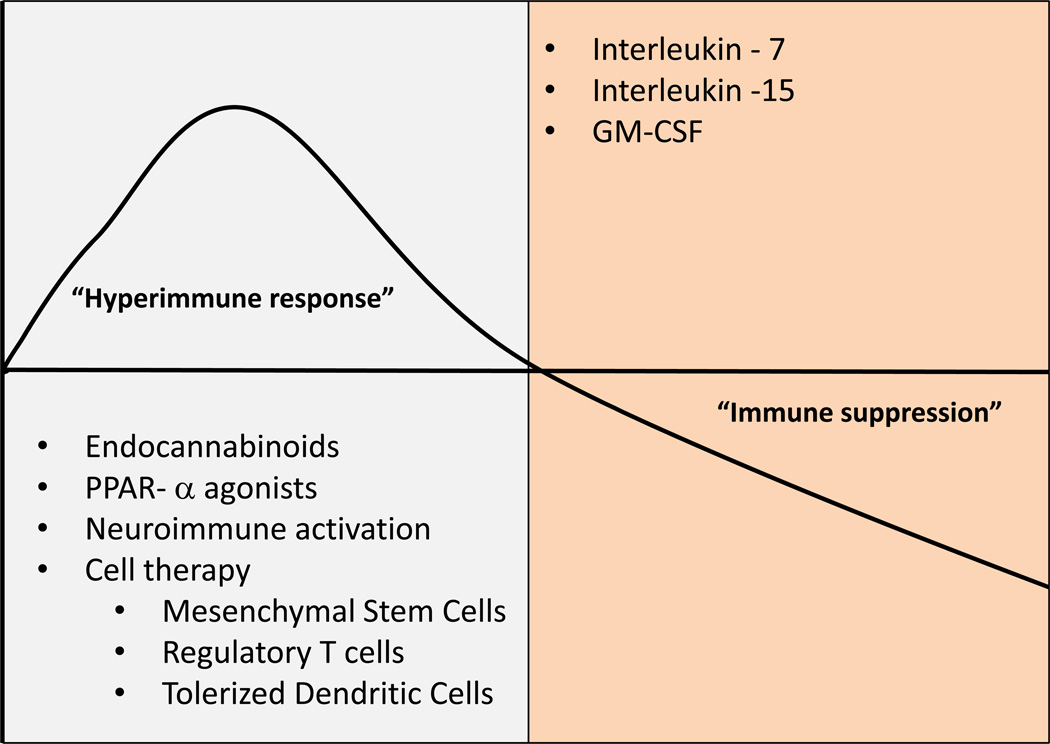

Late deaths may be due to pronounced immunosuppression and T cell exhaustion10,16. Patients who died of sepsis in the ICU when compared to control patients who were declared brain dead or had emergent splenectomy due to trauma, had splenocytes that had significant reductions in secretion of TNF, interferon gamma (INF-γ), IL-6, IL-1016. There was also reduced CD28 expression, a costimulatory molecule that activates T cells, increased PD-1 expression, a molecule that negatively regulates T cell activation and T cell proliferation, increased CTLA-4 expression, a receptor that down regulates the immune response and lastly reduced IL-7Ra16. Thus, therapeutic approaches should consider temporal changes in immune responsiveness; suppression of early inflammation and enhancing late immunity (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Immune responsiveness following sepsis.

The host response to sepsis and septic shock is an early dysregualted immune response that is mediate via activation of innate immunity followed by a state of immunosuppression. Therapeutics should consider the temporal profile of the immune status. Early blockade of proinflammatory pathways should be followed by late activation of immunity.

Targeting Early Inflammation

Alkaline phosphatase

Recent studies by Pickers et al. have suggested a novel approach targeting inflammation in SA-AKI17,18. In their preclinical and clinical studies, these authors have used systemic alkaline phosphatase administration as an anti-inflammatory strategy to demonstrate protection in SA-AKI. Alkaline phosphatase is thought to neutralize bacterial endotoxin through direct dephosphorylation of endotoxin. Furthermore, alkaline phosphatase catalyzes the conversion of the danger molecule, adenosine triphosphate (ATP), into adenosine, a potent anti-inflammatory factor. Activation of adenosine 2a receptors have potent antiinflammatory effects19,20 and synthetic analogs block AKI21,22 and improve survival in sepsis23. In a recent phase IIa studies, administration of recombinant alkaline phosphatase resulted in reduced inflammation and decreased SA-AKI although there were no changes in mortality17,18. If these provocative findings can be confirmed in large-scale clinical trials, it will provide a new strategy to prevent and treat SA-AKI.

Endocannabinoid Receptors (cannabinoid 2 (CB2))

The endocannabinoid system represents a unique target for the treatment of sepsis. This system is an endogenous signaling system that modulates a variety of functions including the immune system. The two most important receptors are G-protein coupled receptors, cannabinoid 1 (CB1) and cannabinoid 2 (CB2), are linked to Gi, which inhibit adenylyl cyclase and intracellular cAMP accumulation24. Whereas CB1 receptors are expressed primarily in the central nervous system24, CB2 receptors are expressed on leukocytes and regulate the immune system25–27. CB2 receptor activation attenuates leukocyte endothelial cell interaction and recruitment of leukocytes and reduces proinflammatory mediators28–31. Using cecal ligation puncture (CLP) model of sepsis, CB2 receptor deficient mice had increased mortality, lung injury, and neutrophil recruitment at the site of infection32. A highly selective CB2 receptor agonist, N-(piperidin-1-yl)-1-(2,4-dichlorophenyl)-1,4-dihydro-6-methylindeno[1,2-c]pyrazole-3-carboxamide (GP1a) (Ki values for this compound are 0.037 and 363 nM for the CB2R and CB1R, respectively) reduced inflammation, bacterial colony count and improved survival time32. In humans, administration of lipopolysaccharide leads to an increase in endogenous cannabinoid, anandamide33 suggesting a potential role for CB2 receptor agonists for the treatment of sepsis.

PPAR alpha agonists

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha (PPARα), a member of the nuclear receptor superfamily of ligand-dependent transcription factors related to retinoid, steroid, and thyroid hormone receptors34. Fibrates are ligands for PPARα receptors and have been shown to have anti-inflammatory properties. They have known effects on classically activated macrophages to block AP1 and NKF-Kβ signaling35,36 and inhibit proinflammatory molecules including IFN-γ and IL-17 37,38. In animal models of AKI, fibrates protect from cisplatin induced AKI39 by preventing proximal tubule cell death40. In SA-AKI, fibrates have been shown to ameliorate bacterial sepsis induced by Salmonella tymphimurium by promoting neutrophil recruitment via CXCR 241. LPS induced down regulation of CXCR2 was blocked increasing neutrophil influx, decrease bacterial count and improved survival. Thus enhancing bacterial clearance while potentially preserving proximal tubule survival might be good combination for SA-AKI.

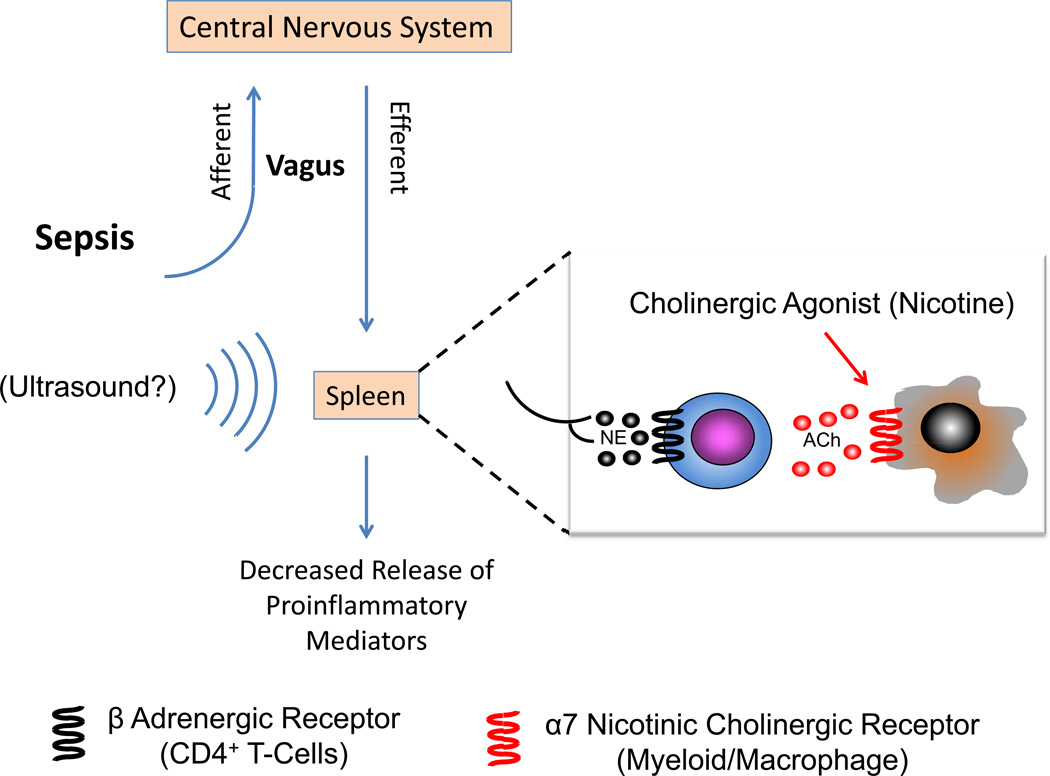

Neuro-Immune Activation-the Cholinergic Antiinflammatory Pathway

The nervous system controls inflammatory responses through a reflex circuit in which afferent signals sense inflammation and efferent signals quell inflammation42,43 (Figure 2). This anti-inflammatory pathway referred to as the cholinergic antiinflammatory pathway (CAP) has recently been described44. Afferent and efferent signals are transmitted by the vagus nerve in response to DAMPS or PAMPS. Activation of the splenic nerve stimulates the production of acetylcholine by a splenic CD4+ subset within the white pulp via β-adrenergic receptors activation. Acetylcholine then traverses into the red pulp and activates alpha-7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (α7nAChRs) expressed on splenic myeloid/macrophages. Binding of acetylcholine to α7nAChRs on nearby myeloid/macrophages cells results in suppressed splenic, and in turn, systemic cytokine (proinflammatory cytokines such as TNFα, IL1β, High Mobility Group Box 1 (HMGB1) levels during inflammation (both sepsis and other inflammatory diseases). Experimental studies demonstrate that stimulation of the vagus nerve attenuates cytokine release in sepsis, IRI and other states of inflammation and nicotine, an α7nAChRs agonist, reduces mortality in sepsis45,46. The current methods used to directly stimulate the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway are limited to administration of nonspecific cholinergic agonists or surgical methods to stimulate the vagus nerve47. Recently, a modified ultrasound regimen activated the CAP and protected kidneys from IRI48 (Figure 2). In this study, anesthetized mice were exposed to an ultrasound (US) protocol 24 hrs prior to renal ischemia. After 24 hrs of reperfusion, US-treated mice had marked attenuation of plasma creatinine, inflammation and preserved morphology compared to sham US-treated mice. This marked protective effect was observed even when mice were exposed to the same US regimen 48 hours prior to ischemia. There was marked reduction in interstitial fibrosis, which suggests that this treatment may retard progression of AKI to CKD/ESRD. Renal protection against IRI depended on splenic CD4+ T cells and α7nAchR-expressing cells. Splenectomy abrogated the protective effect of US against AKI. These results strongly support the concept that CAP is important in attenuating AKI and that a simple modified nonpharmacologic, noninvasive, ultrasound-based method may reduce AKI. Preliminary results suggest that this US regimen may protect from sepsis-associated AKI (unpublished observations, Gigliotti and Okusa, 2014).

Figure 2. Cholinergic Anti-inflammatory Reflex.

The cholinergic antiinflammatory reflex regulating immunity is initiated by DAMPs and PAMPS that active the afferent signaling pathway of the vagus nerve to the nucleus tractus solatarius. Neural signals are sent to the hypothalamus and brainstem and efferent signals emanate from the ambiguous and dorsal motor nucleus and travel down the vagus nerve (for a review see156). Activation of the adrenergic splenic nerve results in the release of norepinephrine, which binds to adrenergic receptors on nearby CD4+ T-cells. This stimulates the production of acetylcholine that binds to α7nAChRs on splenic myeloid cells (macrophages) and results in suppression of the synthesis and release of proinflammatory mediators such as TNF, IL-1, IL-18, HMGB1, chemokines and other cytokines. Nicotine, an a7nAChR agonist, mimics the effect of Ach. A simple US regimen is thought to activate the splenic cholinergic reflex and attenuate kidney IRI48. US – ultrasound, NE - norepinephrine, ACh – acetylcholine.

Soluble Thrombomodulin

Healthy endothelial cells maintain regional microcirculation and prevent thrombosis through thrombomodulin-protein C system 49. Endothelial dysfunction from AKI or sepsis, leads to microvascular flow changes and tissue hypoperfusion, tissue hypoxia and inflammation 50. Thrombomodulin (TM) is a 557 amino acid glycoprotein expressed broadly on surface of endothelial cells exert thromboresistance resulting in anticoagulation49. On the cell surface, thrombin-mediated cleavage of protein C requires TM as a co-factor generating activated protein C (APC). APC is an important modulator of coagulation and inflammation associated with sepsis by inactivating factor Va and VIIIa, thereby promoting fibrinolysis and inhibiting thrombosis. In clinical studies of sepsis the use of APC was associated with a significant increase in bleeding risk 51. Soluble TM may exert local effects to activate protein C and prevent regional coagulation events without systemic effects. Recent studies have demonstrated that sTM was effective in preventing and treating establish AKI, an effect associated with reduced leukostasis and endothelial cell permeability52. The mechanism of protection was independent of the generation of APC, as a sTM variant, unable to activate rat PC, was effective as wild-type sTM in preserving renal function. Although the data suggest that the protective effect is independent of its anticoagulant effect, sTM may exert is effect by several means. sTM may have anti-inflammatory effects; studies using N-terminal lectin-like domain of TM, which lacks anticoagulant function, block leukocyte adhesion to endothelial cells53. In addition sTM may have cytoprotective and antiinflammatory effects through activating endothelial cell protein C receptor/protease activated receptor (EPCR/PAR) signaling. Lastly sTM inactivates C3a or C5a and blocks inflammation49. Thus additional studies are necessary to delineate the mechanism of action of sTM while clinical studies are ongoing to demonstrate its efficacy in sepsis (Table 2).

Table 2.

Selected trials of therapeutics for sepsis

| Trial Name | Identifier and Status |

Description |

|---|---|---|

| Phase 3 Safety and Efficacy Study of ART-123 in Subjects With Severe Sepsis and Coagulopathy |

NCT01598831 Recruiting |

Recombinant thrombomodulin (ART-123) was found to be a safe intervention in critically ill patients with sepsis and suspected disseminated intravascular coagulation. A phase 2b study provided evidence suggestive of efficacy supporting further development of this drug in sepsis-associated coagulopathy including disseminated intravascular coagulation132 |

| Safety and Efficacy of Talactoferrin Alfa in Patients With Severe Sepsis (OASIS) |

NCT01273779 Suspended |

Talactoferrin alfa, a recombinant form of human lactoferrin, has anti-infective and anti-inflammatory properties and plays an important role in maintaining gastrointestinal mucosal barrier integrity. In experimental animal models, administration of talactoferrin reduces translocation of bacteria from the gut into the systemic circulation and mortality from sepsis131. However, the phase II/III trial was halted due to higher 28-day mortality rate in the talactoferrin group. |

| A Study to Compare the Efficacy and Safety of 2 Dosing Regimens of IV Infusions of AZD9773 (CytoFab™) With Placebo in Adult Patients With Severe Sepsis and/or Septic Shock |

NCT01145560 Completed |

The polyclonal ovine anti-TNF Fab fragments (CytoFab) has the ability to neutralize tumor necrosis factor and decrease the TNF-dependent production of interleukin-6 (IL-6) and interleukin-8 (IL-8)134. In a preliminary study CytoFab reduced TNF-α and IL-6 levels and increased the number of ventilator-free and intensive care unit (ICU)-free days at day 28134 |

| Evaluation of Safety, PK and Immunomodulatory Effects of AB103 in Necrotizing Soft Tissue Infections Patients |

NCT01417780 Active, not yet recruiting (May 2014) |

AB103 is a novel synthetic CD28 mimetic octapeptide that selectively inhibits the direct binding of superantigen exotoxins to the CD28 costimulatory receptor on T-helper lymphocytes. Preclinical studies demonstrated that AB103 and related superantigen mimetic peptides are associated with improved survival in animal models of toxic shock and sepsis. A preliminary trial in patients with necrotizing soft-tissue infections showed improvements in illness severity score and overall safety of the agent 130 |

| Effects of Alkaline Phosphatase on Renal Function in Septic Patients |

NCT00457613 Completed |

Alkaline phosphatase is able to reduce inflammation through dephosphorylation and thereby detoxification of endotoxin (lipopolysaccharide), which is an important mediator of sepsis. Second, adenosine triphosphate, released during cellular stress caused by inflammation and hypoxia, has detrimental effects but can be converted by alkaline phosphatase into adenosine with anti-inflammatory and tissue-protective effects. Phase 2a clinical trials have demonstrated benefit in reducing sepsis-associated AKI17. |

| In Vivo Effects of C1-esterase inhibitor on the Innate Immune Response During Human Endotoxemia - VECTOR II |

NCT01766414 Not yet opened (May 2014) |

C1-esterase inhibitor, an endogenous acute-phase protein, regulates various inflammatory and anti-inflammatory pathways, including the kallikrein-kinin system and leukocyte activity. A preliminary study assessed the influence of high-dose C1-esterase inhibitor administration on systemic inflammatory response and survival in patients with sepsis and demonstrated that high-dose C1-esterase inhibitor infusion down-regulated the systemic inflammatory response and was associated with improved survival rates in sepsis patients133. |

| The effects of interferon-gamma on sepsis-induced immunoparalysis |

NCT01649921 Recruiting |

A decrease in monocyte function can be seen in sepsis and may predispose patients to infections. Interferon (IFN)-gamma can restore monocytic function 135. The primary aim of this study is to assess the effects of adjunctive therapy with IFN-gamma on immune function in patients with septic shock in a placebo-controlled manner. Moreover, the investigators want to evaluate new markers that could be used to identify patients with immunoparalysis, and to monitor the patient's immunological response to IFN-gamma. |

| Does GM-CSF Restore Neutrophil Phagocytosis in Critical Illness? (GMCSF) |

NCT01653665 Recruiting |

GM-CSF has been studied for use in sepsis in several small trials with conflicting results10. The putative role for GM-CSF in sepsis is to restore the ability of neutrophils to ingest and kill bacteria. Future larger scale clinical trials are needed. |

| Impact of Low Dose Unfractionated Heparin Treatment on Inflammation in Sepsis |

NCT02135770 Recruiting |

Heparin compounds have anti-inflammatory and anti-thrombotic effects that may be beneficial for the treatment of sepsis. Two prior trials have demonstrated conflicting results138,140. This study enrolls up to 100 patients to assess the effects of unfractionated heparin on inflammatory markers as well as mortality and improvement in APACHE II score. |

| Statin Therapy in the Treatment of Sepsis |

NCT00676897 Recruiting |

Statins have anti-inflammatory properties including the ability to suppress endotoxin-induced up-regulation of TLR-2 and TLR-4. Small studies have yielded conflicting results and this study is a small randomized, double-blind trial assessing the outcome of time to shock reversal as well as IL-6 levels. |

| Role of ‘Pentoxifylline and or IgM Enriched Intravenous Immunoglobulin in the Treatment of Neonatal Sepsis |

NCT01006499 Status unknown |

Pentoxifylline inhibits neutrophil adhesion and activation and modulates cytokine production in response to endotoxin. An early study142 demonstrated benefit in illness severity scores but no improvement in mortality. This study aims to assess pentoxifylline effects in neonates with sepsis with or without IgM enriched immunoglobulin. |

| Esmolol Effects on Heart and Inflammation in Septic Shock (ESMOSEPSIS) Pilot Phase II Study: Hemodynamic Tolerance and Anti-inflammatory Effects of Esmolol During the Treatment of Septic Shock (THANE) |

NCT02068287 Recruiting NCT02120404 Not yet open |

Beta-adrenergic system over-activity is common in sepsis and may contribute to poor outcomes. An early study demonstrated benefits of esmolol on hemodynamic parameters in septic patients143. These studies assess the hemodynamic effects of esmolol as well as changes in microcirculation and cytokine profiles in patients with sepsis. |

| Dexmedetomidine for Sepsis in ICU Randomized Evaluation Trial (DESIRE) The Effect of Dexmedetomidine on Microcirculation in Severe Sepsis Safety Study of Dexmedetomidine in Septic Patients |

NCT01760967 Recruiting NCT02109965 Not yet open NCT01976754 Recruiting |

Dexmedetomidine (DEX) is a selective agonist of the α2-adrenergic receptors that suppresses inflammatory mediators in animal models of sepsis144. These trials are testing the hypothesis that DEX may improve clinical outcomes and have organ protective effects in patients with sepsis. |

| Acetaminophen for the Reduction of Oxidative Injury in Severe Sepsis (ACROSS) |

NCT01739361 Completed |

Cell-free hemoglobin is present in the plasma of patients with sepsis and is associated with poor outcomes145. Acetaminophen may have a protective effect by inhibiting hemoprotein-mediated lipid peroxidation. This study aims to assess systemic markers of oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation in septic patients and the effects of acetaminophen on these compounds. |

| Selenium Replacement and Serum Selenium Level in Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock Patients (SEREAL) |

NCT01601938 Not yet Recruiting |

Patients with sepsis have been found to have low selenium levels146. In some studies, high-dose selenium has shown benefit146,147. This study will be performed to determine whether selenium replacement reduces 28-day mortality of severe sepsis and septic shock patients, and to investigate whether selenium replacement contributes differently to the mortalityl reduction of the patients according to their initial serum selenium level. |

| Citrulline in Severe Sepsis |

NCT01474863 Recruiting |

Low levels of citrulline are associated with an increased risk of acute respiratory distress syndrome and this may be due to citrulline overconsumption due to nitric acid production148. This is a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 study to evaluate biochemical, clinical, and safety effects of 2 doses of intravenous L-citrulline compared to placebo in patients with severe sepsis at risk for or with acute lung injury. The hypothesis is that intravenous L-citrulline will decreased the development or progression of acute lung injury in patients with severe sepsis compared to placebo. |

| Rapid Administration of Carnitine in sEpsis (RACE) |

NCT01665092 Recruiting |

Exogenous L-carnitine administration enhances glucose and lactate oxidation, attenuates fatty acid toxicity, and improves cardiac mechanical efficiency149. The overall goal of this proposal is to investigate L-carnitine as a novel adjunctive treatment of septic shock. The primary hypothesis is: Early adjunctive L-carnitine administration in vasopressor dependent septic shock will significantly reduce cumulative organ failure at 48 hours with an associated decrease in 28-day mortality suggesting the need for further phase III study |

| Zinc Therapy in Critical Illness The Impact of Zinc Supplementation on Innate Immunity and Patient Safety in Sepsis |

NCT01162109 Recruiting NCT02130388 |

Zinc is essential for normal immune function, oxidative stress response, and wound healing. Zinc deficiency leads to loss of innate and adaptive immunity and increased susceptibility to infections. There is strong biologic rationale to suggest that the zinc deficiency seen in nearly all sepsis patients may contribute to the development of sepsis syndrome and to the "immunoparalysis" common in sepsis patients118,147. This study has three specific aims, 1) to perform a phase I dose-finding study of intravenous zinc in mechanically ventilated patients with severe sepsis; 2) to define the pharmacokinetic of intravenous zinc in mechanically ventilated patients with severe sepsis compared to healthy controls; and 3) to investigate the impact of zinc on inflammation, immunity, and oxidant defense in patients with severe sepsis. This study will determine if zinc supplementation is safe to use in patients with severe sepsis or septic shock. This study will also gather preliminary information to evaluate the impact that zinc has on the immune system |

| ADjunctive coRticosteroid trEatment iN criticAlly ilL Patients With Septic Shock (ADRENAL) Efficacy of Hydrocortisone in Treatment of Severe Sepsis/Septic Shock Patients With Acute Lung Injury/Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) |

NCT01448109 Recruiting NCT01284452 Recruiting |

Corticosteroids (hydrocortisone) are sometimes administered to patients with sepsis.150,151. Previous research has suggested that the use of low dose steroid may have short-term benefits in improving the circulation. However, there is no agreement about whether treatment with or without low dose steroids improves the overall recovery and survival in patients with septic shock. This is a large study in 3800 patients who will be randomized to receive either hydrocortisone 200mg or placebo daily for 7 days as a continuous intravenous infusion while in intensive care. The patient will be followed for 90 days. This study will investigate whether hydrocortisone can effectively prevent disease progression and death in severe sepsis/septic shock patients who also have acute lung injury, or acute respiratory distress syndrome |

| Efficacy of Melatonin in Patients With Severe Sepsis or Septic Shock |

NCT01858909 Not yet Recruiting |

Melatonin's protective action against sepsis is suggested to be due to its antioxidant, immunomodulating and inhibitory actions against the production and activation of pro-inflammatory mediators152. However, melatonin has not been studied in human sepsis. This placebo-controlled trial will evaluate the survival to 28 days as well as other outcomes measures and biochemical and cytokine profiles. |

| Cholecalciferol Supplementation for Sepsis in the ICU (CSI) |

NCT01896544 Recruiting |

Vitamin D has been identified as a key regulator of the immune system153. Little is known about the effects of vitamin D supplementation in patients with severe infections. This study will investigate whether high doses of cholecalciferol (vitamin D3) can improve vitamin D status and boost certain aspects of the immune system in patients with sepsis. |

| Thiamine as a Metabolic Resuscitator in Septic Shock |

NCT01070810 Recruiting |

Thiamine deficiency is common is patients with sepsis and is associated with an increase in mortality. The goal of this study is determine whether the use of thiamine in patients with septic shock will result in attenuation of lactic acidosis and a more rapid reversal of shock. |

| Vitamin C Infusion for Treatment in Sepsis Induced Acute Lung Injury (CITRIS-ALI) |

NCT02106975 Not yet open (May 2014) |

Characteristics of severe sepsis include ascorbate (reduced vitamin C) depletion and parenteral administration of ascorbate decreases hypotension, edema, multiorgan failure, and death in animal models of sepsis155. Goal of this study is to determine if vitamin C can attenuate lung injury, organ failure and inflammation in sepsis. |

Cell-Based Therapies

Severe sepsis is characterized by multiorgan dysfunction in critically ill patients leading to septic shock a condition that is complicated by hypotension unresponsive to fluid resuscitation and vasopressors. In these instances there is marked dysregulation of the immune response as a result of cytokine, chemokine, complement activation products and intracellular alarmins10,54–56. The myriad number of cytokines that contribute to the dysregulated state of sepsis necessitates combining multiple targets in treating sepsis55,57. Cell-based therapy may lead to the broad ability to block the innate immune response by targeting multiple sites. Stem cells are unspecialized or undifferentiated precursor cells that have the capacity for self-renewal and can differentiate into different cell types58. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCS) are the best studied. These cells are generated in bone marrow and can differentiate into osteocytes, chondrocytes and adipocytes and their use in therapeutics takes advantage of their pluripotency, hypo-immunogenicity, easy accessibility from bone marrow and rapid ex vivo expansion. When MSCs were infused they have been shown to protect and enhance recovery in cisplatin, glycerol and IRI59–63. In solid organ transplantation, preclinical studies demonstrate a potent effect of MSCs factors that contribute to transplant tolerance. Based upon these findings preclinical studies are underway and may be effective in reducing the risk of acute rejection64,65.

Although they have the capacity for transdifferentiation, the observation thus far is that the number of differentiated stem cells that contribute to tissue protection/repair are low and the tissue protective effects are most likely due to paracrine mechanisms including growth factors, cytokines that modulate mitogenesis, apoptosis, inflammation and vasculogenesis and angiogenesis62,66–69. MSCs have been shown to enhance proliferation of endogenous tubule epithelial cells through soluble factors63. Recently microvesicles derived from MSCs have been shown to shuttle mRNA to injured cells to enhance survival70. In experimental sepsis, MSCs reduce inflammation and AKI71,72.

Other forms of cell-based therapies may be useful in sepsis, primarily to quell the early proinflammatory state. Regulatory CD4+CD25+ T cells (Tregs) suppress inflammatory conditions including AKI73 through cell to cell contact and cytokine independent mechanisms (see review by74. When T regulatory cells are stimulated in vivo in a cecal ligation puncture model of sepsis and administered to mice in prevention or therapeutic mode they have been shown to improve survival and bacterial clearance75.

Dendritic cells (DCs) are a heterogeneous bone-marrow derived antigen presenting cells. They have distinct maturation and activation states and have the potential to induce immunity or tolerance76,77. Tolerogenic DCs have the capacity to present antigen to antigen specific T cells but are unable to adequately provide costimulatory signals that lead to T cell activation and proliferation. Tolerogenic DCs are potentially useful in graft versus host disease, autoimmune disease, and transplant tolerance78. Recently DCs were tolerized by adenosine 2a agonist treatment that attenuated kidney IRI22. Generating tolerized DCs can be achieved through treatment with growth factors and cytokines (TGFβ, IL-10, VEGF), genetic engineering (sphingosine 1-phosphate 3 deficiency, NF-κB oligonucleotides), pharmacological agents (calcineurin inhibitors, adenosine 2a agonists)22,78,79. Its use in attenuating the dysregulated cytokine response during sepsis has not yet been tested.

Targeting Late Immune Suppression

The importance of temporal nature of sepsis has important implications regarding therapeutic intervention. The concept that hyperimmune response characterizes early sepsis necessitates early anti-inflammatory approaches. However, late in the course of sepsis the marked immunosuppressive state requires requires interventions that stimulate the immune response such as IL-7, PD-1/PD-1 antibodies and other immunoadjuvants.

Interleukin - 7

IL-7 is critical for T cell development and function and its effects are mediated by heterodimeric IL-7Rs which are expressed on human T cells, central memory T cells and T regulatory cells80. In sepsis models, IL-7 enhances immunity by: increasing expression of cell adhesion molecules facilitating leukocyte trafficking to sites of infection, increasing T cell activation and proliferation, preventing T cell apoptosis and T cell depletion and restoring T cell IFN-γ production81,82. In humans, ex vivo treatment of human lymphocytes increases cell proliferation, IFN-γ production, Bcl-2 induction and T cell diversity, factors that enhance immune response to pathogens83–85.

PD-1/PD-1L antibodies

In sepsis, there is an increase in inhibitory program cell death 1 (PD-1 and its ligand (PD-L1) that could contribute to immune suppression in late sepsis through T cell exhaustion3,86. When blood from septic and non septic patients were assess by flow cytometry, septic patients had a higher percentage of CD4-, CD8-PD-1 expression and monocyte-PDL-1 expression. This was associated with a decrease in lymphocyte IFN-γ and IL-2 expression. Anti-PD1 and anti-PD1L antibody increased IFN-γ, IL-2 production and decreased lymphocyte apoptosis86. In animal models of sepsis, PD-L1 deficient mice87) or using anti-PD-188 or anti-PD-L1 blocking antibody improves survival. In cancer, T cell exhaustion appears to contribute to the immunosuppressed state, thus given the efficacy and safety profile of anti-PD-1 and anti-PD1L in cancer clinical trials89,90 and preclinical efficacy in sepsis, these results suggest the potential use in anti-PD1 and anti-PD1L antibody in clinical trials to augment immune responsiveness in sepsis.

Other immunoadjuvants

Interleukin 15, an immunoadjuvant molecule similar to IL-7, has important effects on natural killer cell (NK) cell development, survival and function, as well as NK cell cytotoxicity91. In sepsis, IL-15 decreases apoptosis of immune cells similar to IL-792. Granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) has been shown to enhance immune function in septic patients. Neutrophils are the primary host defense against infection and during sepsis neutrophil function appears to be defective93–95. In clinical studies of sepsis, GM-CSF restores monocyte function96,97 and shortens time of mechanical ventilation and hospital ICU stay96. Thus these studies support the need for additional human studies in septic patients.

Cell survival: Oxidative stress, mitochondria and anti-oxidant strategies

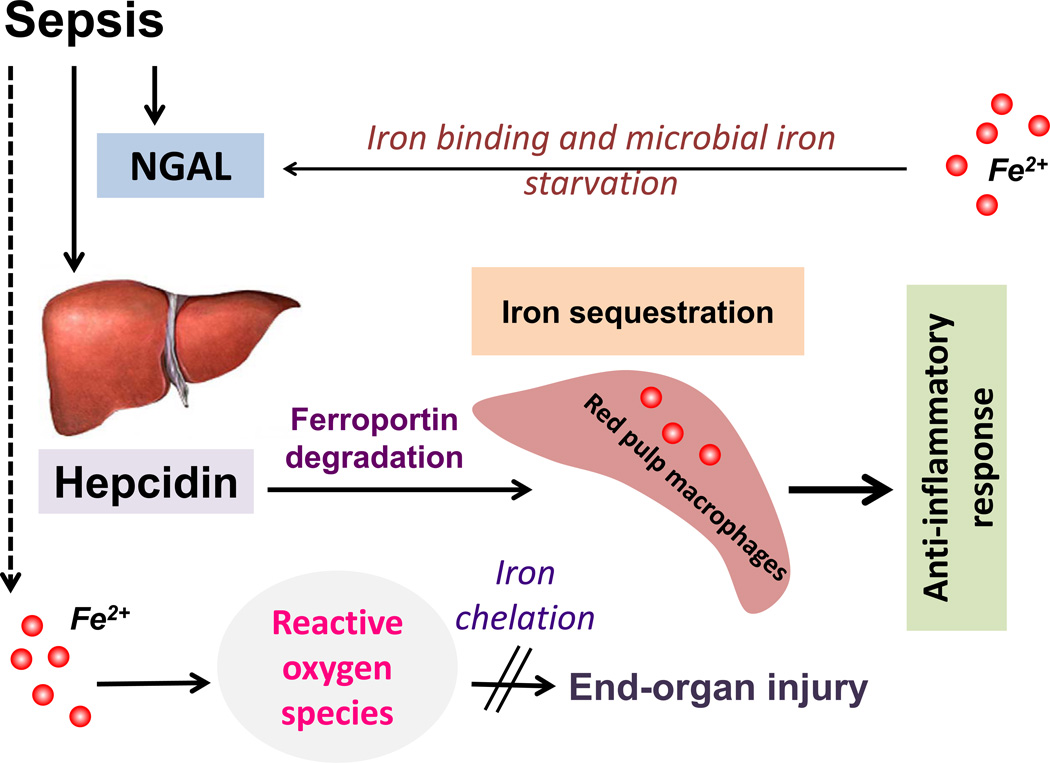

Iron

Iron contributes to host intracellular and extracellular and as well as microbial function during sepsis (Figure 3). While catalytic (also referred to as labile) iron is injurious to cells through its ability to undergo redox cycle and induce oxidative radicals98, various physiologic intracellular processes such as mitochondrial function, cell cycle and deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) repair are iron-dependent99. Similarly, microbes secrete molecules called siderophores to capture iron for their growth and survival. Iron starvation of the microbe is a sentinel strategy adopted by the body to counter infection and sepsis100. Cells synthesize iron-sequestrating proteins such as neutrophil gelatinase-associated protein (NGAL) to outcompete microbial response. Iron sequestration is also achieved through the release of hepcidin, an antimicrobial peptide released from the liver. Hepcidin downregulates iron export protein, ferroportin, to induce reticuloendothelial iron sequestration101. Macrophages act as a safe reservoir to store iron in its non-toxic in ferritin. In murine infection models such as in malarial infection, hepcidin overexpression is effective in limiting the progression of infection102,103. Further, hepcidin treatment and subsequent macrophage iron sequestration has been shown to inhibit lipopolysaccharide (LPS)- and sepsis-induced pro-inflammatory response104. However, it is unknown if hepcidin treatment would induce protection against sepsis-induced kidney injury. Also, there is only limited data on using iron chelation to treat sepsis or its complications105. Iron chelation with desferrioxamine induced protection against sepsis-associated mortality and this was associated with paradoxical upregulation of the pro-apoptotic factor, Bax106.

Figure 3. Iron homeostasis and sepsis.

Microbes secrete siderophores to capture iron required for their growth and survival. Hosts secrete NGAL to mediate antimicrobial response through iron starvation. Sepsis-associated inflammatory response induces release of antimicrobial peptide, hepcidin, from the liver. Hepcidin downregulates ferroportin to induce reticuloendothelial iron sequestration, which in turn leads to decreased availability of extracellular iron for microbial growth. Iron sequestration in macrophages also results in attenuated pro-inflammatory response to endotoxemia and sepsis. Dysregulated iron homeostasis would result in oxidative stress and worse sepsis-associated end organ injury. Iron chelation might be of therapeutic benefit in decreasing oxidative stress induced damage. NGAL, Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin.

Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)

Progression of sepsis results in cellular oxygen deprivation constitutes the end-result of sepsis. In response to hypoxia, HIF is induced. Further, HIF is upregulated through pathways involving the key immune response regulator nuclear factor-kappaB (NF-κB)107. Of the various isoforms, HIF-1α activation induces the release of pro-angiogenic VEGF and vasoconstrictors like endothelin-1. Further, LPS induces HIF-1α by inhibiting prolyl hydroxylase (PHD) expression. HIF-1α promotes production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and is a key mediator of the host response to sepsis108. It was recently demonstrated that PHD3 rather than PHD1 inhibition more specifically worsened sepsis-associated innate immune responses and outcome, in a HIF-1α- and NF-κB-dependent manner. Anti-cancer drug, 2-methoxyestradiol, known to inhibit HIF-1α- and NF-κB, was recently shown to protective in a murine sepsis model. 2-methoxyestradiol therapy prevented sepsis-associated mortality and complications including AKI109.

HIF-2α activation results in the release of erythropoietin, which in addition to its known ability to induce erythropoiesis is also a cytoprotective molecule. Very little is known on the effect of modulating HIF-2α in sepsis.

Heme oxygenase

Heme proteins, universally present in cellular compartments of different organ systems, perform vital functions such as oxygen transport and mitochondrial electron transport. With cell injury, as heme proteins are released from the cells, heme dissociates with ease from the globin moiety. Free heme is cytotoxic and inducible heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) and constitutive heme oxygenase-2 (HO-2) degrades free heme into cytoprotective molecules including bilirubin and carbon monoxide (CO). This reaction, further, results in the generation of free iron, and induction of cytoprotective ferritin110. Genetic deficiency of HO-1 results in more severe AKI after rhabdomyolysis, ischemia or endotoxemia. Chemical (heme arginate) or genetic induction of HO-1 protects against kidney injury. Reduction in renal injury mediated through HO-1 is thought to involve three complementary mechanisms: 1) reduction in the endogenous heme; 2) generation of cytoprectants (bilirubin, CO and ferritin) and 3) modulation of iron homeostasis111,112. Macrophage HO-1 is likely to play a critical protective function in AKI as heme arginate, known to induce HO-1 in macrophages in vitro and in vivo, mitigated age-dependent sensitivity to AKI. Similarly, macrophages with adenoviral overexpression of HO-1 also protected against ischemic kidney injury and HO-1 overexpression improved the anti-inflammatory and phagocytic function of macrophages113. HO-1 might also be protective in AKI through its suppressive effects on tubuloglomerular feedback. Recently, mitochondria-specific expression of HO-1 was shown to be protective in ischemic AKI114. In murine endotoxemia model, inhibition of HO-1 with zinc protoporphyrin resulted in a paradoxical protective response with improved systemic hemodynamics, increased renal blood flow and better glomerular filtration rate 115. This apparent paradox is attributed to the prevention of CO-mediated vasodilatation by HO-1 inhibition. In another study, it was shown that while HO-1 deficiency was associated with better systemic hemodynamics, it resulted in worse LPS-induced mortality116.

Mitochondrial ROS

Recent studies by Holthoff et al., indicate that SA-AKI is associated with reduction in renal blood flow (RBF), which is characterized by compromised circulation in the capillaries adjacent to the tubules that demonstrate increased inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and nitrosative oxidative stress117. Furthermore, in a cecal ligation picture model of sepsis, selective inhibition of iNOS prevented tubular oxidative stress and reversal of microcirculatory abnormalities. Although further work needs to be done to understand the link between tubular epithelial oxidative stress and microcirculatory dysfunction, therapeutic importance is supported by the observation that use of resveratrol, a scavenger of peroxynitrite and superoxide, is protective against SA-AKI. Resveratrol treatment diminished tubular oxidative stress, improved microcirculatory flow, prevented sepsis-associated kidney pathology and improved survival117. There are other redox-based compounds such as lactoferrin, selenium, pentoxyfylline and edaravone that have shown benefit in pre-clinical models118.

Mitochondrial biogenesis

Tran et al have confirmed sepsis-associated reduction in RBF in their recent study119. However, in their study, tissue oxygenation remained intact despite reduced RBF as kidney oxygen consumption was diminished. The authors demonstrated impaired mitochondrial function with reduced expression of PPAR-γ coactivator-1α (PGC-1α), a regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis, in SA-AKI. There was a marked functional to structural dissociation as tubular cells with severe mitochondrial dysfunction demonstrated little demonstrable pathology. Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) reduced PGC-1α and oxygen consumption and overexpression of PGC-1α corrected the mitochondrial defect. Of note, resveratrol is also known to induce mitochondrial biogenesis120.

Collectively, these studies stress the central importance of targeting iron and heme homeostasis and optimizing kidney mitochondrial function in preventing and treating SA-AKI.

Molecular mechanisms of recovery

While multiple cellular pathways get activated during organ repair and recovery after sepsis, mitochondrial biogenesis, autophagy induction and resumption of cell cycle play vital roles. Here, we will review the role of cell cycle and autophagy in sepsis recovery.

Cell cycle

Induction of cell cycle arrest in G1 phase is a key mechanism for cell death and AKI in sepsis. In fact, urine levels of insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 7 (IGFBP7) and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-2 (TIMP-2), both inducers of G1 cell cycle arrest, were identified as powerful biomarkers of SA-AKI121. In murine models of sepsis, G1 cell cycle arrest was shown to play a role in the initiation of sepsis-associated AKI and cell cycle progression through phosphorylation of retinoblastoma gene was shown to involved in the recovery of AKI122.

Autophagy

Successful cellular recovery requires cleaning up internal and external cellular debris. Autophagy is a process whereby damaged internal organelles such as mitochondria are processed by lysosomal autophagy apparatus to facilitate cell survival. While uncontrolled autophagy itself might contribute to organ dysfunction, a successful and limited autophagy response triggers an antiinflammatory response and tissue repair. Inhibition of autophagy in sepsis leads to accumulation mitochondrial DNA and NALP3 inflammasome activation123. Mice deficient in autophagy (LC3B deficient mice) were more susceptible to LPS-induced mortality123. LC3 overexpression was shown to improve survival and reduce lung injury through increased autophagosome clearance124. In murine models of sepsis, induction of autophagy with either temsirolimus, a target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor or AICAR, an adenosine monophosphate kinase (AMPK) inhibitor, protected against the development of sepsis-associated AKI125. More recently, low doses of anthracycline, a cancer chemotherapy drug, were shown offer robust protection against sepsis by triggering DNA damage-mediated protective response and autophagy102.

Ongoing clinical trials in sepsis

Similar to the experience with finding effective therapeutics for acute kidney injury (AKI), the treatment of sepsis has been limited to therapy of the underlying inciting factors with no pharmaceuticals or other strategies found to be effective in all patients. In fact, initially promising therapies such as drotrecogin alfa (a recombinant form of human activated protein C) have now been withdrawn from the market after failing to demonstrate a survival benefit in a follow-up clinical trial subsequent to the initial registration study126 (http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm277114.htm). This does not mean that the search for effective therapeutics has ceased and a search of www.clinicaltrials.gov in May 2014, listed 1328 studies in sepsis of which 560 were open and 343 involved an active intervention to improve outcomes.

Many of these therapeutic strategies attempt to modulate the body’s innate immune response during sepsis (Table 2 is a partial list of these trials). An example of a promising but failed attempt at developing therapeutics in this area was drugs targeting toll-like receptors (TLRs). These are pattern-recognition receptors on the surface of immune cells that recognize highly conserved molecules, such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or peptidoglycans on the surface of microbes. This recognition leads to widespread activation of the immune response, which may be excessive and contribute to poor outcomes127. Thus, targeting TLRs would seem an attractive strategy to mitigate the excessive inflammatory response associated with sepsis. Unfortunately, a recent notable failure with this approach was with the drug eritoran (synthetic lipid A antagonist that blocks lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from binding at the cell surface MD2-TLR4 receptor), which had demonstrated promising preclinical data128. In a large, multicenter randomized trial (ACCESS trial), eritoran failed to show any benefit in 28-day mortality over placebo 6. Other strategies that aim to modify the immune response and are in various stages of development include: drugs targeting bacterial superantigens (AB103) 129,130, immunomodulatory proteins (talactoferrin)131 http://agennix.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=205%3Aagennix-ag-halts-phase-iiiii-oasis-trial-in-severe-sepsis&catid=23%3Apress-releases-2012&Itemid=56&lang=en (accessed May 18, 2014), and anticoagulant pathways (ART-123)132, as well as blocking complement activation (C1-esterase inhibitor)133, and inhibiting inflammatory cytokines (CytoFab against tumor necrosis alpha)134. Trials for these agents are in various stages (Table 2).

Another novel approach has been based upon the finding that late sepsis-related deaths appear to be often associated with evidence of immune suppression and dysfunction10,135. Thus, those patients that survive the initial pro-inflammatory stage may enter an anti-inflammatory phase with variable degrees of “immunoparalysis.” To counter this phase, immune enhancement or immunoadjuvant strategies are being studied. Agents that are being studied include: interferon (IFN)-gamma 136, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF)3, interleukin (IL)-783, IL-15 92, anti-PD (programmed cell death receptor)-1 88 and anti-BTLA (B and T lymphocyte attenuator)137. An important aspect of these immunoadjuvant therapies may be that biomarkers to identify the immune suppressed stage of sepsis will have to be incorporated into treatment algorithms135. This ensures that these agents will not further enhance the pro-inflammatory stages of sepsis and are targeted to specific defects in immune function.

There are a host of other compounds that are being actively studied for the treatment of sepsis with details in Table 2. These include: heparin138,139, statins140,141, pentoxifylline142, beta-blockade143, dexmedetomidine144, acetaminophen145, selenium146,147, L-citrulline148, L-carnitine149, zinc118, hydrocortisone150,151, melatonin152, vitamin D153, thiamine154, and vitamin C155. Several of these trials test the concept as to whether pharmaconutrients given in large doses can improve outcomes in sepsis through anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory mechanisms147.

Of note, many of the ongoing studies are small or pilot trials that are likely underpowered to determine clinical efficacy while some trials aim to explore outcomes with drugs that have had contradictory results in prior trials (such as with corticosteroids and heparin). Given the increased understanding of the mechanisms involved in sepsis it is likely that there will be continued growth in clinical trials to determine efficacy of these targeted approaches.

Conclusions

The successful treatment of SA-AKI necessitates an integrative therapeutic approach that takes into consideration the temporal nature of systemic immune response and local kidney specific factors. Single therapies are unlikely to be effective and nearly all have failed in the past. Thus timely intervention of general measures such as antibiotics, fluids, and vasopressors are required. In addition attenuating the profound proinflammatory response as well as the activating late immune suppressive response may complement these general measures. Lastly interventions to enhance cell survival and enhance cellular recovery provide the best opportunity for improving outcomes in SA-AKI.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by NIH grants DK085259, DK062324, DK093841 and Ivy Biomedical Innovation Fund. The authors are grateful for the scientific contributions by Drs. Li Li (Department of Pathology, University of Virginia) and Amandeep Bajwa, Gilbert Kinsey and Diane Rosin as well as technical assistance from Liping Huang and Hong Ye (Division of Nephrology and Center for Immunity, Inflammation and Regenerative Medicine, University of Virginia).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Uchino S, Kellum JA, Bellomo R, Doig GS, Morimatsu H, Morgera S, et al. Acute renal failure in critically ill patients: a multinational, multicenter study. JAMA. 2005;294:813–818. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.7.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angus DC, van der Poll T. Severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:840–851. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1208623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hutchins NA, Unsinger J, Hotchkiss RS, Ayala A. The new normal: immunomodulatory agents against sepsis immune suppression. Trends Mol Med. 2014;20:224–233. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zarjou A, Agarwal A. Sepsis and acute kidney injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22:999–1006. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010050484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matejovic M, Chvojka J, Radej J, Ledvinova L, Karvunidis T, Krouzecky A, et al. Sepsis and acute kidney injury are bidirectional. Contrib Nephrol. 2011;174:78–88. doi: 10.1159/000329239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Opal SM, Laterre PF, Francois B, LaRosa SP, Angus DC, Mira JP, et al. Effect of eritoran, an antagonist of MD2-TLR4, on mortality in patients with severe sepsis: the ACCESS randomized trial. JAMA. 2013;309:1154–1162. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.2194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Osuchowski MF, Welch K, Siddiqui J, Remick DG. Circulating cytokine/inhibitor profiles reshape the understanding of the SIRS/CARS continuum in sepsis and predict mortality. J Immunol. 2006;177:1967–1974. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.3.1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abraham E, Glauser MP, Butler T, Garbino J, Gelmont D, Laterre PF, et al. p55 Tumor necrosis factor receptor fusion protein in the treatment of patients with severe sepsis and septic shock. A randomized controlled multicenter trial. Ro 45-2081 Study Group. JAMA. 1997;277:1531–1538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matsuda A, Jacob A, Wu R, Aziz M, Yang WL, Matsutani T, et al. Novel therapeutic targets for sepsis: regulation of exaggerated inflammatory responses. J Nippon Med Sch. 2012;79:4–18. doi: 10.1272/jnms.79.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hotchkiss R, Monneret G, Payen D. Sepsis-induced immunosuppression: from cellular dysfunctions to immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:862–874. doi: 10.1038/nri3552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thomas L. Germs. N Engl J Med. 1972:287. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197209142871109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosin DL, Okusa MD. Dangers within: DAMP responses to damage and cell death in kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22:416–425. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010040430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uematsu S, Akira S. Toll-like receptors and innate immunity. J Mol Med (Berl) 2006;84:712–725. doi: 10.1007/s00109-006-0084-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Creagh EM, O’Neill LA. TLRs, NLRs and RLRs: a trinity of pathogen sensors that co-operate in innate immunity. Trends Immunol. 2006;27:352–357. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hotchkiss RS, Karl IE. The pathophysiology and treatment of sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:138–150. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra021333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boomer JS, To K, Chang KC, Takasu O, Osborne DF, Walton AH, et al. Immunosuppression in patients who die of sepsis and multiple organ failure. JAMA. 2011;306:2594–2605. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peters E, Heemskerk S, Masereeuw R, Pickkers P. Alkaline phosphatase: a possible treatment for sepsis-associated acute kidney injury in critically ill patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;63:1038–1048. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pickkers P, Heemskerk S, Schouten J, Laterre PF, Vincent JL, Beishuizen A, et al. Alkaline phosphatase for treatment of sepsis-induced acute kidney injury: a prospective randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Crit Care. 2012;16:R14. doi: 10.1186/cc11159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li L, Okusa MD. Blocking the Immune respone in ischemic acute kidney injury: the role of adenosine 2A agonists. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol. 2006;2:432–444. doi: 10.1038/ncpneph0238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sullivan GW, Linden J. Role of A2A Adenosine Receptors in Inflammation. Drug Dev Res. 1998;45:103–112. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Day Y-J, Huang L, McDuffie MJ, Rosin DL, Ye H, Chen JF, et al. Renal protection from ischemia mediated by A2A adenosine receptors on bone marrow-derived cells. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:883–891. doi: 10.1172/JCI15483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li L, Huang L, Ye H, Song SP, Bajwa A, Lee SJ, et al. Dendritic cells tolerized with adenosine A(2)AR agonist attenuate acute kidney injury. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:3931–3942. doi: 10.1172/JCI63170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sullivan GW, Fang G, Linden J, Scheld WM. A2A adenosine receptor activation improves survival in mouse models of endotoxemia and sepsis. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:1897–1904. doi: 10.1086/386311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schatz AR, Lee M, Condie RB, Pulaski JT, Kaminski NE. Cannabinoid receptors CB1 and CB2: a characterization of expression and adenylate cyclase modulation within the immune system. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1997;142:278–287. doi: 10.1006/taap.1996.8034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Munro S, Thomas KL, Abu-Shaar M. Molecular characterization of a peripheral receptor for cannabinoids. Nature. 1993;365:61–65. doi: 10.1038/365061a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pacher P, Mechoulam R. Is lipid signaling through cannabinoid 2 receptors part of a protective system? Prog Lipid Res. 2011;50:193–211. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klein TW, Newton C, Friedman H. Cannabinoid receptors and the cytokine network. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1998;437:215–222. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-5347-2_24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sardinha J, Kelly ME, Zhou J, Lehmann C. Experimental cannabinoid 2 receptor-mediated immune modulation in sepsis. M Mediators Inflamm. 2014;2014:978678. doi: 10.1155/2014/978678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rajesh M, Mukhopadhyay P, Batkai S, Hasko G, Liaudet L, Huffman JW, et al. CB2-receptor stimulation attenuates TNF-alpha-induced human endothelial cell activation, transendothelial migration of monocytes, and monocyte-endothelial adhesion. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H2210–H2218. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00688.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klein TW. Cannabinoid-based drugs as anti-inflammatory therapeutics. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:400–411. doi: 10.1038/nri1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ramirez SH, Hasko J, Skuba A, Fan S, Dykstra H, McCormick R, et al. Activation of cannabinoid receptor 2 attenuates leukocyte-endothelial cell interactions and blood-brain barrier dysfunction under inflammatory conditions. J Neurosci. 2012;32:4004–4016. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4628-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tschop J, Kasten KR, Nogueiras R, Goetzman HS, Cave CM, England LG, et al. The cannabinoid receptor 2 is critical for the host response to sepsis. J Immunol. 2009;183:499–505. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Varga K, Wagner JA, Bridgen DT, Kunos G. Platelet- and macrophage-derived endogenous cannabinoids are involved in endotoxin-induced hypotension. FASEB J. 1998;12:1035–1044. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.12.11.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang K, Wan YJ. Nuclear receptors and inflammatory diseases. Exp Biol Med. 2008;233:496–506. doi: 10.3181/0708-MR-231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Neve BP, Corseaux D, Chinetti G, Zawadzki C, Fruchart JC, Duriez P, et al. PPARalpha agonists inhibit tissue factor expression in human monocytes and macrophages. Circulation. 2001;103:207–212. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.2.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rigamonti E, Chinetti-Gbaguidi G, Staels B. Regulation of macrophage functions by PPARalpha, PPAR-gamma, and LXRs in mice and men. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:1050–1059. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.158998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee JW, Bajwa PJ, Carson MJ, Jeske DR, Cong Y, Elson CO, et al. Fenofibrate represses interleukin-17 and interferon-gamma expression and improves colitis in interleukin-10-deficient mice. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:108–123. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marx N, Kehrle B, Kohlhammer K, Grub M, Koenig W, Hombach V, et al. PPAR activators as antiinflammatory mediators in human T lymphocytes: implications for atherosclerosis and transplantation-associated arteriosclerosis. Circ Res. 2002;90:703–710. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000014225.20727.8f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li S, Gokden N, Okusa MD, Bhatt R, Portilla D. Anti-inflammatory effect of fibrate protects from cisplatin-induced ARF. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005;289:F469–F480. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00038.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nagothu KK, Bhatt R, Kaushal GP, Portilla D. Fibrate prevents cisplatin-induced proximal tubule cell death. Kidney Int. 2005;68:2680–2693. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tancevski I, Nairz M, Duwensee K, Auer K, Schroll A, Heim C, et al. Fibrates ameliorate the course of bacterial sepsis by promoting neutrophil recruitment via CXCR2. EMBO Mol Med. 2014;6:810–820. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201303415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Straub RH. Complexity of the bi-directional neuroimmune junction in the spleen. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2004;25:640–646. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Andersson U, Tracey KJ. Reflex principles of immunological homeostasis. Annu Rev Immunol. 2012;30:313–335. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rosas-Ballina M, Olofsson PS, Ochani M, Valdes-Ferrer SI, Levine YA, Reardon C, et al. Acetylcholine-synthesizing T cells relay neural signals in a vagus nerve circuit. Science. 2011;334:98–101. doi: 10.1126/science.1209985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim TH, Kim SJ, Lee SM. Stimulation of the alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor protects against sepsis by inhibiting Toll-like receptor via phosphoinositide 3-kinase activation. J Infect Dis. 2014;209:1668–1677. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chatterjee PK, Yeboah MM, Dowling O, Xue X, Powell SR, Al-Abed Y, et al. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonists attenuate septic acute kidney injury in mice by suppressing inflammation and proteasome activity. PLoS One. 2012;7:e35361. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bonaz B, Picq C, Sinniger V, Mayol JF, Clarencon D. Vagus nerve stimulation: from epilepsy to the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013;25:208–221. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gigliotti JC, Huang L, Ye H, Bajwa A, Chattrabhuti K, Lee S, et al. Ultrasound prevents renal ischemia-reperfusion injury by stimulating the splenic cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24:1451–1460. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013010084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Martin FA, Murphy RP, Cummins PM. Thrombomodulin and the vascular endothelium: insights into functional, regulatory, and therapeutic aspects. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2013;304:H1585–H1597. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00096.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sutton TA, Fisher CJ, Molitoris BA. Microvascular endothelial injury and dysfunction during ischemic acute renal failure. Kidney Int. 2002;62:1539–1549. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bernard GR, Vincent JL, Laterre PF, LaRosa SP, Dhainaut JF, Lopez-Rodriguez A, et al. Efficacy and safety of recombinant human activated protein C for severe sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:699–709. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103083441001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sharfuddin AA, Sandoval RM, Berg DT, McDougal GE, Campos SB, Phillips CL, et al. Soluble thrombomodulin protects ischemic kidneys. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:524–534. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008060593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Conway EM, Van de Wouwer M, Pollefeyt S, Jurk K, Van Aken H, De Vriese A, et al. The lectin-like domain of thrombomodulin confers protection from neutrophil-mediated tissue damage by suppressing adhesion molecule expression via nuclear factor kappaB and mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways. J Exp Med. 2002;196:565–577. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Andreux PA, Houtkooper RH, Auwerx J. Pharmacological approaches to restore mitochondrial function. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12:465–483. doi: 10.1038/nrd4023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Opal SM, Huber CE. Bench-to-bedside review: Toll-like receptors and their role in septic shock. Crit Care. 2002;6:125–136. doi: 10.1186/cc1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang H, Yang H, Czura CJ, Sama AE, Tracey KJ. HMGB1 as a late mediator of lethal systemic inflammation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:1768–1773. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.10.2106117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vincent JL. Management of sepsis in the critically ill patient: key aspects. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2006;7:2037–2045. doi: 10.1517/14656566.7.15.2037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McCulloch EA, Till JE. Perspectives on the properties of stem cells. Nat Med. 2005;11:1026–1028. doi: 10.1038/nm1005-1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Morigi M, Introna M, Imberti B, Corna D, Abbate M, Rota C, et al. Human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells accelerate recovery of acute renal injury and prolong survival in mice. Stem Cells. 2008;26:2075–2082. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Herrera MB, Bussolati B, Bruno S, Fonsato V, Romanazzi GM, Camussi G. Mesenchymal stem cells contribute to the renal repair of acute tubular epithelial injury. Int J Mol Med. 2004;14:1035–1041. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Herrera MB, Bussolati B, Bruno S, Morando L, Mauriello-Romanazzi G, Sanavio F, et al. Exogenous mesenchymal stem cells localize to the kidney by means of CD44 following acute tubular injury. Kidney Int. 2007;72:430–441. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Togel F, Hu Z, Weiss K, Isaac J, Lange C, Westenfelder C. Administered mesenchymal stem cells protect against ischemic acute renal failure through differentiation-independent mechanisms. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005;289:F31–F42. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00007.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bi B, Schmitt R, Israilova M, Nishio H, Cantley LG. Stromal cells protect against acute tubular injury via an endocrine effect. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:2486–2496. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007020140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Alagesan S, Griffin MD. Autologous and allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells in organ transplantation: what do we know about their safety and efficacy? Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2014;19:65–72. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0000000000000043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Perico N, Casiraghi F, Introna M, Gotti E, Todeschini M, Cavinato RA, et al. Autologous mesenchymal stromal cells and kidney transplantation: a pilot study of safety and clinical feasibility. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:412–422. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04950610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gnecchi M, Zhang Z, Ni A, Dzau VJ. Paracrine mechanisms in adult stem cell signaling and therapy. Circ Res. 2008;103:1204–1219. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.176826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Phinney DG, Prockop DJ. Concise review: mesenchymal stem/multipotent stromal cells: the state of transdifferentiation and modes of tissue repair--current views. Stem cells. 2007;25:2896–2902. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Togel F, Zhang P, Hu Z, Westenfelder C. VEGF is a mediator of the renoprotective effects of multipotent marrow stromal cells in acute kidney injury. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13:2109–2114. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00641.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Togel F, Weiss K, Yang Y, Hu Z, Zhang P, Westenfelder C. Vasculotropic, paracrine actions of infused mesenchymal stem cells are important to the recovery from acute kidney injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007 doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00339.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bruno S, Grange C, Deregibus MC, Calogero RA, Saviozzi S, Collino F, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived microvesicles protect against acute tubular injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:1053–1067. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008070798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Luo CJ, Zhang FJ, Zhang L, Geng YQ, Li QG, Hong Q, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells ameliorate sepsis-associated acute kidney injury in mice. Shock. 2014;41:123–129. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pedrazza L, Lunardelli A, Luft C, Cruz CU, de Mesquita FC, Bitencourt S, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells decrease splenocytes apoptosis in a sepsis experimental model. Inflamm Res. 2014 Jun 3; doi: 10.1007/s00011-014-0745-1. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kinsey GR, Sharma R, Huang L, Li L, Vergis AL, Ye H, et al. Regulatory T Cells Suppress Innate Immunity in Kidney Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:1744–1753. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008111160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kinsey GR, Okusa MD. Expanding role of T cells in acute kidney injury. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2014;23:9–16. doi: 10.1097/01.mnh.0000436695.29173.de. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Heuer JG, Zhang T, Zhao J, Ding C, Cramer M, Justen KL, et al. Adoptive transfer of in vitro-stimulated CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells increases bacterial clearance and improves survival in polymicrobial sepsis. J Immunol. 2005;174:7141–7146. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.11.7141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Steinman RM, Hawiger D, Nussenzweig MC. Tolerogenic dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:685–711. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Banchereau J, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature. 1998;392:245–252. doi: 10.1038/32588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Morelli AE, Thomson AW. Tolerogenic dendritic cells and the quest for transplant tolerance. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:610–621. doi: 10.1038/nri2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bajwa A, Huang L, Ye H, Dondeti K, Song S, Rosin DL, et al. Dendritic cell sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor-3 regulates Th1-Th2 polarity in kidney ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Immunol. 2012;189:2584–2596. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mackall CL, Fry TJ, Gress RE. Harnessing the biology of IL-7 for therapeutic application. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:330–342. doi: 10.1038/nri2970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Unsinger J, McGlynn M, Kasten KR, Hoekzema AS, Watanabe E, Muenzer JT, et al. IL-7 promotes T cell viability, trafficking, and functionality and improves survival in sepsis. J Immunol. 2010;184:3768–3779. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Li WQ, Guszczynski T, Hixon JA, Durum SK. Interleukin-7 regulates Bim proapoptotic activity in peripheral T-cell survival. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:590–600. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01006-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Venet F, Foray AP, Villars-Mechin A, Malcus C, Poitevin-Later F, Lepape A, et al. IL-7 restores lymphocyte functions in septic patients. J Immunol. 2012;189:5073–5081. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Morre M, Beq S. Interleukin-7 and immune reconstitution in cancer patients: a new paradigm for dramatically increasing overall survival. Target Oncol. 2012;7:55–68. doi: 10.1007/s11523-012-0210-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sportes C, Hakim FT, Memon SA, Zhang H, Chua KS, Brown MR, et al. Administration of rhIL-7 in humans increases in vivo TCR repertoire diversity by preferential expansion of naive T cell subsets. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1701–1714. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chang K, Svabek C, Vazquez-Guillamet C, Sato B, Rasche D, Wilson S, et al. Targeting the programmed cell death 1: programmed cell death ligand 1 pathway reverses T cell exhaustion in patients with sepsis. Crit Care. 2014;18:R3. doi: 10.1186/cc13176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Huang X, Chen Y, Chung CS, Yuan Z, Monaghan SF, Wang F, et al. Identification of B7-H1 as a novel mediator of the innate immune/proinflammatory response as well as a possible myeloid cell prognostic biomarker in sepsis. J Immunol. 2014;192:1091–1099. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Brahmamdam P, Inoue S, Unsinger J, Chang KC, McDunn JE, Hotchkiss RS. Delayed administration of anti-PD-1 antibody reverses immune dysfunction and improves survival during sepsis. J Leukoc Biol. 2010;88:233–240. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0110037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, Gettinger SN, Smith DC, McDermott DF, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2443–2454. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Brahmer JR, Tykodi SS, Chow LQ, Hwu WJ, Topalian SL, Hwu P, et al. Safety and activity of anti-PD-L1 antibody in patients with advanced cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2455–2465. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lu J, Giuntoli RL, 2nd, Omiya R, Kobayashi H, Kennedy R, Celis E. Interleukin 15 promotes antigen-independent in vitro expansion and long-term survival of antitumor cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:3877–3884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Inoue S, Unsinger J, Davis CG, Muenzer JT, Ferguson TA, Chang K, et al. IL-15 prevents apoptosis, reverses innate and adaptive immune dysfunction, and improves survival in sepsis. J Immunol. 2010;184:1401–1409. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Alves-Filho JC, Spiller F, Cunha FQ. Neutrophil paralysis in sepsis. Shock. 2010;34(Suppl 1):15–21. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181e7e61b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kovach MA, Standiford TJ. The function of neutrophils in sepsis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2012;25:321–327. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e3283528c9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Cummings CJ, Martin TR, Frevert CW, Quan JM, Wong VA, Mongovin SM, et al. Expression and function of the chemokine receptors CXCR1 and CXCR2 in sepsis. J Immunol. 1999;162:2341–2346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Meisel C, Schefold JC, Pschowski R, Baumann T, Hetzger K, Gregor J, et al. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor to reverse sepsis-associated immunosuppression: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled multicenter trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:640–648. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200903-0363OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hall MW, Knatz NL, Vetterly C, Tomarello S, Wewers MD, Volk HD, et al. Immunoparalysis and nosocomial infection in children with multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. Intensive Care Med. 2011;37:525–532. doi: 10.1007/s00134-010-2088-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Gutteridge JM, Halliwell B. Iron toxicity and oxygen radicals. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 1989;2:195–256. doi: 10.1016/s0950-3536(89)80017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Saletta F, Suryo Rahmanto Y, Siafakas AR, Richardson DR. Cellular iron depletion and the mechanisms involved in the iron-dependent regulation of the growth arrest and DNA damage family of genes. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:35396–35406. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.273060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ganz T. Iron in innate immunity: starve the invaders. Curr Opin Immunol. 2009;21:63–67. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Drakesmith H, Prentice AM. Hepcidin and the iron-infection axis. Science. 2012;338:768–772. doi: 10.1126/science.1224577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Figueiredo N, Chora A, Raquel H, Pejanovic N, Pereira P, Hartleben B, et al. Anthracyclines induce DNA damage response-mediated protection against severe sepsis. Immunity. 2013;39:874–884. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.08.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Portugal S, Carret C, Recker M, Armitage AE, Goncalves LA, Epiphanio S, et al. Host-mediated regulation of superinfection in malaria. Nat Med. 2011;17:732–737. doi: 10.1038/nm.2368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.De Domenico I, Zhang TY, Koening CL, Branch RW, London N, Lo E, et al. Hepcidin mediates transcriptional changes that modulate acute cytokine-induced inflammatory responses in mice. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:2395–2405. doi: 10.1172/JCI42011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Thuma PE, Mabeza GF, Biemba G, Bhat GJ, McLaren CE, Moyo VM, et al. Effect of iron chelation therapy on mortality in Zambian children with cerebral malaria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1998;92:214–218. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(98)90753-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Messaris E, Antonakis PT, Memos N, Chatzigianni E, Leandros E, Konstadoulakis MM. Deferoxamine administration in septic animals: improved survival and altered apoptotic gene expression. Int Immunopharmacol. 2004;4:455–459. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2004.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Nizet V, Johnson RS. Interdependence of hypoxic and innate immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:609–617. doi: 10.1038/nri2607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]