Abstract

Objectives

While medication treatment is necessary for the successful management of bipolar disorder (BD), non-adherence rates are up to 60%. Although medication attitudes are believed to be relevant to adherence behavior, few studies have investigated the trajectories of adherence change. This study evaluated attitudinal correlates of adherence conversion in 86 poorly adherent individuals with BD.

Methods

This secondary analysis pooled data from two uncontrolled prospective trials of Customized Adherence Enhancement (CAE), a psychosocial intervention delivered over 4-6 weeks. Poor adherence was defined as missing at least 20% of prescribed BD medication based on the self-reported Tablets Routine Questionnaire (TRQ). The sample was dichotomized into Converters who achieved good adherence (N=44) and Non-Converters who remained poorly adherent (N=21). Converters vs. Non-Converters were compared on adherence, attitudes, and symptoms at baseline, 6 weeks and 3 months.

Results

At baseline, Converters and Non-Converters were similar demographically and clinically, but Converters were less non-adherent (32% doses missed) than Non-Converters (59% missed). At 6 weeks, Converters had better attitudes than Non-Converters. At 3 months, Converters maintained improvements, but group differences were less pronounced due to some improvement in Non-Converters. Converters had better adherence at 3 months and trajectories differed for the groups on attitudes. Symptoms gradually improved for both Converters and Non-Converters.

Conclusions

Over two-thirds of poorly adherent BD patients who received CAE converted to good adherence. Improved medication attitudes may be a driver of improved adherence behavior and ultimately reduced BD symptoms.

Keywords: medication adherence, adherence attitudes, bipolar disorder, converters

1. Introduction

Psychotropic medications are a cornerstone of treatment for individuals with bipolar disorder (BD). However, between 20% and 60% (depending in part on how non-adherence is defined) of people with BD do not take prescribed medication (1,3,4), leading to serious negative outcomes including higher rates of relapse, hospitalization, incarceration, suicide, functional deficits, and homelessness (5-7).

Predictors of medication non-adherence in BD include denial of illness severity, cognitive impairments that make remembering to take medication difficult, patient concerns about short and long-term medication side effects and lack of sufficient information about BD, disorganized home environments, lack of social support, and treatment access problems (6, 8-11). To the best of our knowledge, no studies have prospectively assessed whether interventions specifically targeting adherence can modify medication attitudes in poorly-adherent patients with BD.

Customized Adherence Enhancement (CAE) is a novel blended behavioral approach to improve BD medication adherence. Early results with CAE have been promising (12, 13) and show both adherence and BD symptom improvement. It should be noted that these results were based on studies which did not include a control group, limiting the ability to draw conclusions about the specific effects of the intervention versus natural recovery or nonspecific factors. Furthermore, the patterns of attitude and adherence behavior change were not analyzed and have yet to be understood from the literature. This secondary analysis, pooled from two uncontrolled prospective CAE studies, evaluated attitudinal correlates of adherence behavior change in poorly-adherent BD patients. It was hypothesized that patients who achieved good adherence with CAE (“Converters” who missed less than 20% of prescribed BD medication) would have improved medication attitudes and that these changes would be maintained at the 3-month follow-up. Conversely, patients who did not respond to CAE (“Non-Converters” who continued to miss ≥ 20% of prescribed medication) would not have attitude changes following CAE, and both poor attitudes and poor adherence would remain at 3-month follow-up.

2. Materials and Methods

Data from two prospective, uncontrolled trials of CAE with non-adherent patients with a primary diagnosis of BD were analyzed. CAE is a module-based psychosocial intervention which is flexibly administered to address the specific reasons that a person with BD might be non-adherent with prescribed medications. The modules are assigned based on responses to identified questions from the Attitudes toward Mood Stabilizers Questionnaire (AMSQ) (14) and the Rating of Medication Influences Scale (ROMI) (15) screen. There is a low threshold for module assignment in order to capture all participants with potential need. There are 4 available modules in CAE including: 1) Psychoeducation, 2) Substance Abuse, 3) Medication Routines, and 4) Communication with Providers. CAE modules were derived from principles of existing evidence-based approaches for patients with BD including Patient-Centered Health Beliefs (16), Collaborative Care and the Life Goals Program by Bauer and colleagues (37, 38, 39), Motivational Interviewing (36), and Interpersonal and Social Rhythm Therapy by Frank and colleagues (17).

The Psychoeducation module approaches BD as a biological disorder that can be managed by appropriate medication treatments in conjunction with non-somatic coping strategies. This 3-unit module covers: 1) basic information about BD, its neurobiological underpinnings, and information on mania and depression; 2) a focus on medication management, identifying the purpose of medication, reviewing good and bad effects of medication, and 3) the development of a personal symptom profile for episodes of depression and mania as well as early warning signs of impending relapse.

The Substance Abuse Module is a 2-unit module which focuses on the effects of substance abuse on BD in general and on adherence to medication specifically. Individuals were encouraged to access personal motivation to change their substance use, making it more likely that they would be adherent to their medication regimen.

Communication with Providers is a 2-unit module which actively examines and explores the key components of treatment planning including expectations for medication response and feared/experienced medication side effects. Key critical issues include understanding the differential burden of medication-related effects and how these effects might be prioritized for discussion with a clinician. The module also provides information on commonly utilized psychotropic agents.

Medication Routines is a 2-unit module which assists individuals to modify treatment regimens as appropriate and facilitates discussion with providers. The module emphasizes the use of prompts/reminders and self-monitoring/self-regulation to maximize and maintain adherence. A key activity in this module is a review of medication-taking patterns, including examination of when, where, and how medications are taken and problem-solves regarding identified challenges/barriers. Assigned modules were administered during four in-person sessions with either the clinical psychologist who authored this paper or one of two interventionists trained and supervised by that psychologist. The sessions were spaced about one week apart for an average duration of approximately 45 minutes (additional information regarding module assignment and the intervention itself can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author).

2.1 Pooled Studies

The pooled data were derived from two nearly identical CAE intervention studies which are described in greater detail elsewhere (12, 13). The first study involved 43 poorly adherent patients with BD prescribed a mood stabilizer and/or an atypical antipsychotic and receiving treatment from a community mental health center. The second study involved 43 poorly-adherent BD patients prescribed an atypical antipsychotic and receiving treatment from centers affiliated with an academic medical center. Participants were either self or clinician-referred. Diagnoses of participants in both studies were provided by patient self-report and confirmed by the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) (18) administered by trained raters. The MINI has extensive research on its psychometric properties including good inter-rater and test-retest reliability (18).

Among the 96 individuals screened for Cohort 1, 44 met inclusion criteria and 43 were enrolled. Of the 91 individuals screened for Cohort 2, 65 met inclusion criteria and 43 were enrolled. Both samples had the same diagnosis, completed identical measures, and underwent the same treatment (CAE). Based on a chi-square analysis, there was no difference in percentage of Converters (35.4% and 32.3%) versus Non-Converters (21.5% and 10.8%) between the first and second study, respectively (x2=1.2(df=1), p=.27). As such, the data from the two studies were pooled.

2.2 Procedures

Non-adherence was defined as missing at least 20% of prescribed BD maintenance medication treatments according to the self-reported Tablets Routine Questionnaire (TRQ) for either the past week or month (19-22). The cutoff of 20% was chosen based on the expert consensus guidelines on adherence in patients with serious mental illness (6). Data were gathered for both past week and past month TRQ. Past week TRQ was utilized given that recall for the past week is likely to be more reliable. Past month TRQ was utilized to capture individuals who may have been adherent in the past week but not for a longer period of time. There are a subset of individuals who are able to maintain adherence for a week or two, but are not consistent over a longer period of time. In addition to the TRQ, inclusion criteria were diagnosis of Bipolar Disorder for at least a two year duration.

Exclusion criteria were inability to complete assessments or imminent suicidal ideation. The study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board and are in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975. All participants provided informed, voluntary, written consent procedures prior to enrollment.

2.3 Specific measures

2.3.1 Tablets Routine Questionnaire (TRQ)

Adherence was assessed using the TRQ (14, 23), a self-report measure which identifies partial and full adherence in the past 7 and past 30 days. While all patients were classified based on the same definitions of adherence, past week and past month TRQs were both analyzed in efforts to incorporate those who may be adherent for a week’s time but are unable to consistently take medication over longer periods. The TRQ has a statistically significant association with past non-adherence, non-adherence in the past month, and non-adherence in the past week, and has been shown to correlate highly with lithium levels (14). An average adherence rating was calculated for individuals taking more than one oral maintenance medication for BD. While there are different alternatives for measuring adherence including measuring the primary BD medication only, we chose to measure the average adherence for all BD maintenance medications given that there may be differential adherence to the various medications. Consistent with BD treatment guidelines (24), we counted lithium, anticonvulsants and antipsychotic medications as BD maintenance drugs.

2.3.2 Attitudes toward Mood Stabilizers Questionnaire (AMSQ)

The AMSQ is a modification of the Lithium Attitudes Questionnaire (25) which evaluates an individual’s attitudes towards mood-stabilizing medication or psychiatric medication in general (14). The AMSQ is a self-report questionnaire with a yes-no format comprised of 19 items. Higher scores represent more negative attitudes. Test-retest reliability for the 19 items ranges from 57.6 % to 96.6%.

2.3 BD Symptoms

Symptoms were measured with the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS)(26, 27), the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D)(28) and the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS)(29, 30).

2.4 Data Analyses

Participants were assessed at baseline, 6 weeks (immediately following CAE treatment) and at 3-month follow-up. In order to validate the self-reported adherence data, two-tailed Pearson correlations were run between past week TRQ and BPRS, YMRS, and HAM-D at baseline, 6 weeks, and 3 months. The sample was dichotomized at 6 weeks based on TRQ scores into those who converted into good adherence (Converters), defined as missing less than 20% of BD medications on either past week or past month TRQ, and those who remained poorly adherent (Non-Converters), defined as missing ≥ 20% of BD medications. Converters and Non-Converters were compared on demographic and clinical variables using Independent sample t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square for categorical variables at baseline. To understand the trajectories of adherence attitudes, behavior, and psychiatric symptoms among Converter and Non-Converter groups, longitudinal linear mixed models were run with AR(1) covariance structure, subject-level random intercepts, with time and converter status as factor variables and baseline past week TRQ as a control variable. Effect sizes were calculated using Cohen’s d. The data were analyzed using SPSS, Version 21.

3. Results

Table 1 shows sample demographic and clinical characteristics. The majority of the sample was female, African American and unmarried with a Bipolar I diagnosis (83.7%). The average number of BD maintenance medications was 1.51 ± .8 with a median of 1 and a range of 3. Baseline TRQ scores were 40% days of missed doses in the past week and 43% in the past month. By 6 weeks, approximately two-thirds of the sample (n=44; 68%) converted to good adherence. All two-tailed Pearson correlations between self-reported past week TRQ and the symptom measures (BPRS, YMRS, HAM-D) were significant at baseline, 6 weeks, and 3 months with r values ranging from .231 (p=.039) to .569 (p=.0001) such that higher non-adherence correlated with more psychiatric symptoms.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of 86 poorly adherent patients with bipolar disorder

| Patient Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Age in years Mean (SD) | 40.8(11.4) |

| Female N (%) | 58(67.4) |

| Race N (%) | |

| White | 32(37.2) |

| Black | 53(61.6) |

| Hispanic ethnicity N (%) | 3(3.5) |

| Education in years Mean (SD) | 12.9(2.7) |

| Marital Status N (%) | |

| Single, never married | 41(47.7) |

| Married | 18(20.9) |

| Separated/Divorced/Widowed | 27(31.4) |

| *Diagnoses N(%) | |

| Bipolar I | 72(87.8) |

| Bipolar II | 10(12.2) |

| Alcohol Abuse in the past 12 months | 6(7.0) |

| Alcohol Dependence in the past 12 months | 16(18.6) |

| Substance Abuse in the past 12 months | 7(8.1) |

| Substance Dependence in the past 12 months | 18(20.9) |

| Age at onset of illness in years | |

| Mean (SD) (Median) | 26.9(12.2) (26) |

| TRQa at baseline Mean (SD) | |

| Past Week | 40.2(31.6) |

| Past Month | 42.8(28.1) |

| BPRSb at baseline Mean (SD) | 37.42(11.9) |

| YMRScat baseline Mean (SD) | 12.1(6.9) |

| HAM-Dd at baseline Mean (SD) | 15.0(6.9) |

Diagnoses determined by the MINI International Neuropsychitric Interview

TRQ = Tablets Routine Questionnaire, % of pills missed in the past week or month as noted

BPRS = Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale

YMRS = Young Mania Rating Scale

HAM-D = Hamilton Depression Rating Scale

Converters (N=44) and Non-Converters (N=21) did not have significant differences in demographic variables including age, age of onset of BD, years of education, sex, ethnicity, or marital status at baseline. Likewise, the two groups did not have significant differences on symptom severity or medication attitudes at baseline. The groups did differ on the TRQ for the past week (t(63)=−3.47, p=.001) with Converters having better adherence rates than Non-Converters . The difference between groups was not statistically significant for past month TRQ.

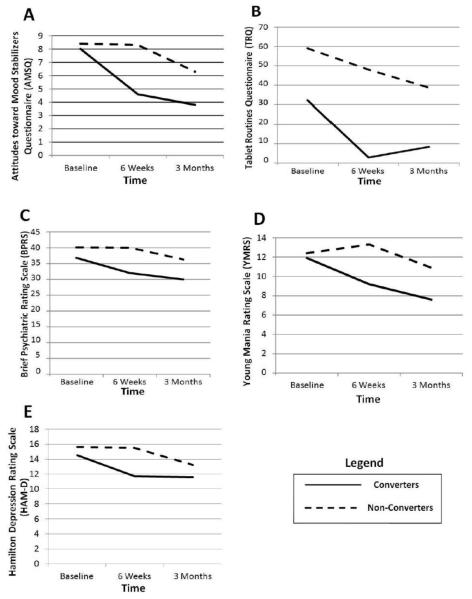

Results from the longitudinal linear mixed models show a significant time by converter status interaction for the AMSQ [F(2,82.5) =5.67, p = .005] indicating that trajectories for AMSQ scores differed by converter status. Figure 1, Graph A shows improved medication attitudes as measured by the AMSQ for Converters at 6 weeks which was maintained at 3 months. Non-Converters did not display improvement at 6 weeks but began to show some attitudinal improvement after 3 months. Effect sizes for AMSQ from baseline to 6 weeks were .81 for Converters and .01 for Non-Converters and from baseline to 3 months were 1.22 for Converters and .57 for Non-Converters.

Figure 1.

Graphs of Converters and Non-Converters on attitudinal measures, drug adherence, and clinical measures.

Figure 1, Graph B shows that Converter past week TRQ scores improved at 6 weeks and were maintained at 3 months. Non-Converters had a gradual improvement in past week TRQ from baseline to 3 months but only reached 40% non-adherence.

The time by converter status interaction was not found to be significant for BPRS [F(2,84.1) =1.58, p = .213], after for controlling for baseline past week TRQ, indicating that trajectories for BPRS scores did not differ by converter status. There was a main effect for time [F(2,84.1) =4.35, p = .016] but not for converter status [F(1,63.2) =1.66, p = .202]. Figure 1, Graph C shows that Converters improved on BPRS at 6 weeks and the improvement was maintained at 3 months. In contrast, Non-Converters did not evidence improvement at 6 weeks but showed some improvement at 3 months. Effect sizes for BPRS from baseline to 6 weeks were .45 for Converters and .0002 for Non-Converters and from baseline to 3 months were .63 for Converters and .30 for Non-Converters.

The time by converter status interaction was not found to be significant for YMRS [F(2,85.4) =2.08, p = .13] after controlling for baseline past week TRQ. Neither the main effects for time [F(2,85.4) =2.70, p = .073] or converter status [F(1,61.83) =1.04, p = .313] were significant. The YMRS trajectories are plotted in Figure 1, Graph D. Effect sizes for YMRS from baseline to 6 weeks were .42 for Converters and .13 for Non-Converters and from baseline to 3 months were .67 for Converters and .20 for Non-Converters.

Finally, the time by converter status interaction was not found to be significant for HAMD [F(2,92.7) =1.46, p = .237] after controlling for past week TRQ. There was a main effect for time [F(2,92.71) =3.34, p = .040] but not for converter status [F(1,61.91) =.279, p = .60]. The YMRS trajectories are plotted in Figure 1, Graph E. Effect sizes for HAM-D from baseline to 6 weeks were .40 for Converters and .01 for Non-Converters and from baseline to 3 months were .41 for Converters and .31 for Non-Converters.

4. Discussion

This longitudinal analysis of a prospective uncontrolled 6-week adherence-focused psychosocial intervention found improved adherence attitudes as well as adherence behaviors in the majority of poorly-adherent patients with BD. While there were no baseline differences in medication attitudes between those who eventually converted to good adherence and those who remained poorly adherent after the 6-week intervention was completed, Converters had better medication attitudes than Non-Converters following treatment, even after controlling for baseline adherence. At 3-month follow-up, Converters still had significantly better adherence, and scored better on the overall AMSQ score. However, differences between the groups were less pronounced due to improvement in the Non-Converters group. The fact that positive medication attitudes were maintained among Converters at 3-month follow-up supports the notion that improved attitudes were a driver of behavior change that translated into better adherence. Furthermore, improved adherence is a possible pathway for symptom improvement

The significant time by converter status interaction for AMSQ, is of particular interest in that it provides evidence for different trajectories for Converters and Non-Converters on medication attitudes. While the Converters responded to the intervention with regard to adherence and medication attitudes following treatment and maintained that improvement at follow-up, the Non-Converters’ attitudes did not change following treatment but did begin to improve at follow-up in conjunction with a gradual yet still sub-target improvement in adherence.

The fact that Non-Converters had some, albeit modest, improvement in adherence behavior and attitudes at 3-month follow-up needs further exploration. One possible explanation is that the Non-Converters responded to the CAE intervention although not enough to bring them into the Converter category, perhaps due to a delay in attitude change. This explanation is consistent with Strauss et al.’s description of a moratorium to explain the non-linear course of psychiatric illness. During such moratoriums, which may occur following exacerbations in symptoms, little change occurs (31). During the moratorium information can still be processed, but attitude and behavior change are expressed only later. Perhaps if our follow-up period had been longer, we may have seen continued improvement in the Non-Converter group. Another explanation for the modest and late effect in the Non-Converters is some benefit from variables other than the CAE intervention, such as participation in a research study and/or attention of study staff. Alternatively, it is possible that our relatively short study was affected by fluctuations in adherence attitudes and behavior that often occur naturally in individuals with BD (17), perhaps in response to varying levels of insight into illness as suggested by Depp et al. (32).

Another important question is whether Converters and Non-Converters differed in any way, prior to the onset of treatment. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics in our sample were similar, but non-adherence was more severe for Non-Converters at baseline. The finding of an inverse relationship between the baseline severity of non-adherence and response to adherence enhancement intervention is of potential clinical relevance. Perhaps extremely non-adherent individuals need a different intervention, such as one that is more targeted or that lasts longer than 6 weeks. Possibilities for such an intervention include a stronger emphasis on motivational interviewing, additional booster sessions, or supplemental phone calls. We are not aware of studies that have specifically examined best practices for various degrees of medication non-adherence in BD, and this is an important area for further study if care approaches are to be best matched to the needs of patients with BD. Another possible explanation is that the baseline difference in adherence plays a larger explanatory role in that it leads to symptom improvement which ultimately drives attitude and adherence improvement. In order to compare these various models statistically, it is recommended that future studies utilize a larger sample size and a control group.

Consistent with the National Institute of Health’s growing emphasis on understanding mechanisms of change (33), our results suggest that medication attitudes are an important, and perhaps necessary, precursor in changing medication-taking behavior. With the emerging importance of the Affordable Care Act (34, 35), organizations and groups that provide care to people with BD are looking for best practices to deliver health care services efficiently.

Limitations of the study include a relatively short-term follow-up, uncontrolled design, a relatively small sample size, and limited assessment of attitudinal and other patient-related factors. In order to determine whether both improved adherence and medication attitudes are maintained long-term, future studies should look at longer term follow-up periods, finer-grained assessment of adherence attitudes including data obtained by qualitative methods, and a control group to determine the specific effects of the intervention versus natural recovery or nonspecific factors which may have accounted for the outcome. Furthermore, adherence was measured using self-reported TRQ which may inflate adherence rates. It is generally recommended that multimodal assessment strategies be used for adherence assessment. As such, future studies should include other methods of adherence enhancement such as pill counts or electronic monitoring in addition to self-report.

An adherence-focused intervention that addresses patient-specific reasons for poor adherence can improve patient attitudes towards BD medications. While the results of this adherence-enhancement intervention study support the theory that adherence attitudes may drive adherence behavior, the direction of the relationship between adherence attitudes and behaviors needs to be further explored in longer-term controlled studies.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this secondary analysis suggests similar medication attitude and adherence trajectories for Converters and Non-Converters with the Converters showing greater and earlier improvement than Non-Converters. Specifically, Converters responded to the intervention with regard to adherence and medication attitudes following treatment and maintained that improvement at follow-up. In contrast, Non-Converters’ attitudes and psychiatric symptoms did not change following treatment but did begin to improve at follow-up in conjunction with a gradual improvement in adherence, although the level did not reach the 80% or more standard of adherence. Furthermore, the findings indicate that there is an inverse relationship between the baseline degree of non-adherence and response to an adherence enhancement intervention, which suggests that the most non-adherent individuals may benefit from a more intense intervention. Finally, our data suggest that by targeting medication attitudes, medication adherence can be potentially improved.

Table 2.

Adherence attitudes, adherence behaviors and bipolar symptoms among poorly adherent individuals with bipolar disorder who converted to good adherence (Converters) compared to those who continued to be poorly adherent (Non-converters) at baseline, 6-week (post-treatment) and 3-month follow-up

| Measures | Baseline | 6 weeks | 3 months | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Converters (n=44) |

Non-Converters (n=41) |

Converters (n=44) |

Non- Converters (n=21) |

Converters (n=43) |

Non- Converters (n=20) |

|

|

|

||||||

| AMSQa Total Mean (SD) |

8.0 (4.6) | 8.4(3.1) | 4.6(3.6) | 8.3(4.0) | 3.8(3.8) | 6.3(4.1) |

| BPRSb Total mean(SD) |

36.8(10.9) | 40.1(14.7) | 32.0(10.1) | 40.0(11.4) | 30.0(10. 8) |

36.3(10.6) |

| YMRSc Total mean(SD) |

11.9(6.6) | 12.4(7.2) | 9.2(6.3) | 13.3(7.2) | 7.6(6.4) | 10.9(7.6) |

| HAM-Dd Total mean(SD) |

14.5(6.7) | 15.6(8.2) | 11.7(7.4) | 15.5(8.2) | 11.6(7.3) | 13.2(7.1) |

| Past Week TRQe Total mean(SD) |

32.2(27.44) | 59.0(32.6) | 2.9(5.6) | 48.0(31.9) | 8.4(22.9) | 38.7(36. 8) |

| Past Month TRQ Total mean(SD) |

39.1(26.6) | 52.8(29.3) | 3.4(5.9) | 40.2(28.9) | 7.1(13.5) | 32.8(33.9) |

Attitudes toward Mood Stabilizers Questionnaire

Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale: 25-32 mildly ill, 33-35 moderately ill, 36-50 markedly ill, 51-70 severely ill

Young Mania Rating Scale: ≤12 remission, ≥14 manic

Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression: 0-7 none, 8-13 mild, 14-18 moderate, 19-22 severe, ≥23 very severe

Tablets Routine Questionnaire

Acknowledgments

Disclosures This work was supported by the following grants and foundations: NIMH (R34MH078967) and AstraZeneca. Jennifer Levin receives partial salary support from Ortho-McNeil Janssen. Martha Sajatovic receives partial salary support from the following research grants: Pfizer, Merck, and Ortho-McNeil Janssen. In addition she has been a consultant for Bracket Corporation, Prophase, Otsuka, Pfizer, Amgen, and has received royalties from Springer Press, Johns Hopkins University Press, Oxford Press, UpToDate, and Lexicomp.

The original two studies were supported by the following grants and foundations: NIMH (R34MH078967) and AstraZeneca.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Sajatovic M, Valenstein M, Blow F, Ganoczy D, Ignacio R. Treatment adherence with lithium and anticonvulsant medications among patients with bipolar disorder. Psychiatric services. 2007 Jun;58(6):855–63. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.6.855. PubMed PMID: 17535948. Epub 2007/05/31. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Psychiatric Association Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder (Revision) American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159(4) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lingam R, Scott J. Treatment non-adherence in affective disorders. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2002 Mar;105(3):164–72. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.1r084.x. PubMed PMID: 11939969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scott J, Pope M. Nonadherence with mood stabilizers: prevalence and predictors. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 2002 May;63(5):384–90. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v63n0502. PubMed PMID: 12019661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Busby KK, Sajatovic M. REVIEW: Patient, treatment, and systems-level factors in bipolar disorder nonadherence: A summary of the literature. CNS neuroscience & therapeutics. 2010 Oct;16(5):308–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2010.00191.x. PubMed PMID: 21050421. Epub 2010/11/06. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Velligan DI, Weiden PJ, Sajatovic M, Scott J, Carpenter D, Ross R, et al. The expert consensus guideline series: adherence problems in patients with serious and persistent mental illness. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 2009;70(Suppl 4):1–46. quiz 7-8. PubMed PMID: 19686636. Epub 2009/08/25. eng. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Folsom DP, Hawthorne W, Lindamer L, Gilmer T, Bailey A, Golshan S, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for homelessness and utilization of mental health services among 10,340 patients with serious mental illness in a large public mental health system. The American journal of psychiatry. 2005 Feb;162(2):370–6. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.2.370. PubMed PMID: 15677603. Epub 2005/01/29. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clatworthy J, Bowskill R, Rank T, Parham R, Horne R. Adherence to medication in bipolar disorder: a qualitative study exploring the role of patients’ beliefs about the condition and its treatment. Bipolar disorders. 2007 Sep;9(6):656–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00434.x. PubMed PMID: 17845282. Epub 2007/09/12. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hou R, Cleak V, Peveler R. Do treatment and illness beliefs influence adherence to medication in patients with bipolar affective disorder? A preliminary cross-sectional study. European psychiatry : the journal of the Association of European Psychiatrists. 2010 May;25(4):216–9. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2009.09.003. PubMed PMID: 20005683. Epub 2009/12/17. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sajatovic M, Ignacio RV, West JA, Cassidy KA, Safavi R, Kilbourne AM, et al. Predictors of nonadherence among individuals with bipolar disorder receiving treatment in a community mental health clinic. Comprehensive psychiatry. 2009 Mar-Apr;50(2):100–7. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2008.06.008. PubMed PMID: 19216885. Pubmed Central PMCID: 2746444. Epub 2009/02/17. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sajatovic M, Levin J, Fuentes-Casiano E, Cassidy KA, Tatsuoka C, Jenkins JH. Illness experience and reasons for nonadherence among individuals with bipolar disorder who are poorly adherent with medication. Comprehensive psychiatry. 2011 May-Jun;52(3):280–7. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2010.07.002. PubMed PMID: 21497222. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3140848. Epub 2011/04/19. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sajatovic M, Levin J, Tatsuoka C, Micula-Gondek W, Fuentes-Casiano E, Bialko CS, et al. Six-month outcomes of customized adherence enhancement (CAE) therapy in bipolar disorder. Bipolar disorders. 2012 May;14(3):291–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2012.01010.x. PubMed PMID: 22548902. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3342843. Epub 2012/05/03. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sajatovic M, Levin J, Tatsuoka C, Micula-Gondek W, Williams TD, Bialko CS, et al. Customized adherence enhancement for individuals with bipolar disorder receiving antipsychotic therapy. Psychiatric services. 2012 Feb 1;63(2):176–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100133. PubMed PMID: 22302337. Epub 2012/02/04. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scott J, Pope M. Self-reported adherence to treatment with mood stabilizers, plasma levels, and psychiatric hospitalization. The American journal of psychiatry. 2002 Nov;159(11):1927–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.11.1927. PubMed PMID: 12411230. Epub 2002/11/02. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weiden P, Rapkin B, Mott T, Zygmunt A, Goldman D, Horvitz-Lennon M, et al. Rating of medication influences (ROMI) scale in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia bulletin. 1994;20(2):297–310. doi: 10.1093/schbul/20.2.297. PubMed PMID: 7916162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scott J. Using Health Belief Models to understand the efficacy-effectiveness gap for mood stabilizer treatments. Neuropsychobiology. 2002;46(Suppl 1):13–5. doi: 10.1159/000068022. PubMed PMID: 12571427. Epub 2003/02/07. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Basco MR, Smith J. Faulty Decision-Making: Impact on Treatment Adherence in Bipolar Disorder. Prim Psychiatr. 2009;16(8):53–8. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl 20):22–33. quiz 4-57. PubMed PMID: 9881538. Epub 1999/01/09. eng. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adams J, Scott J. Predicting medication adherence in severe mental disorders. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2000 Feb;101(2):119–24. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.90061.x. PubMed PMID: 10706011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lew KH, Chang EY, Rajagopalan K, Knoth RL. The effect of medication adherence on health care utilization in bipolar disorder. Managed care interface. 2006 Sep;19(9):41–6. PubMed PMID: 17017312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Valenstein M, Blow FC, Copeland LA, McCarthy JF, Zeber JE, Gillon L, et al. Poor antipsychotic adherence among patients with schizophrenia: medication and patient factors. Schizophrenia bulletin. 2004;30(2):255–64. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007076. PubMed PMID: 15279044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vieta E. Improving treatment adherence in bipolar disorder through psychoeducation. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 2005;66(Suppl 1):24–9. PubMed PMID: 15693749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peet M, Harvey NS. Lithium maintenance: 1. A standard education programme for patients. The British journal of psychiatry : the journal of mental science. 1991 Feb;158:197–200. doi: 10.1192/bjp.158.2.197. PubMed PMID: 1707323. Epub 1991/02/01. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Association AP . American Psychiatric Association Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of Psychiatric Disorders: Compendium 2006. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harvey NS. The development and descriptive use of the Lithium Attitudes Questionnaire. Journal of affective disorders. 1991 Aug;22(4):211–9. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(91)90067-3. PubMed PMID: 1939930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Overall JA, Gorham DR. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychological Reports. 1962;10:799–812. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leucht S, Engel RR, Davis JM, Kissling W, Meyer Zur Capellen K, Schmauss M, et al. Equipercentile linking of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale and the Clinical Global Impression Scale in a catchment area. European neuropsychopharmacology : the journal of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012 Jul;22(7):501–5. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2011.11.007. PubMed PMID: 22386773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 1960 Feb;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. PubMed PMID: 14399272. Pubmed Central PMCID: 495331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Young RC, Biggs JT, Zeigler VE, Meyer DA. A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. The British journal of psychiatry Supplement. 1978;133:429–35. doi: 10.1192/bjp.133.5.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Masand PS, Eudicone J, Pikalov A, McQuade RD, Marcus RN, Vester-Blokland E, et al. Criteria for defining symptomatic and sustained remission in bipolar I disorder: a post-hoc analysis of a 26-week aripiprazole study (study CN138-010) Psychopharmacology bulletin. 2008;41(2):12–23. PubMed PMID: 18668014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Strauss JS, Hafez H, Lieberman P, Harding CM. The course of psychiatric disorder, III: Longitudinal principles. The American journal of psychiatry. 1985 Mar;142(3):289–96. doi: 10.1176/ajp.142.3.289. PubMed PMID: 3970264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Depp CA, Harmell AL, Savla GN, Mausbach BT, Jeste DV, Palmer BW. A prospective study of the trajectories of clinical insight, affective symptoms, and cognitive ability in bipolar disorder. Journal of affective disorders. 2014 Jan;152-154:250–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.09.020. PubMed PMID: 24200153. Pubmed Central PMCID: 4011138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Insel TR. Director’s Blog: A New Approach to Clinical Trials 2014. Available from: http://www.nimh.nih.gov/about/director/2014/a-new-approach-to-clinical-trials.shtml.

- 34.Rosenbaum S, Teitelbaum J, Hayes K. The essential health benefits provisions of the Affordable Care Act: implications for people with disabilities. Issue brief. 2011 Mar;3:1–16. PubMed PMID: 21452594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosenbaum S. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act: implications for public health policy and practice. Public health reports (Washington, DC : 1974) 2011 Jan-Feb;126(1):130–5. doi: 10.1177/003335491112600118. PubMed PMID: 21337939. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3001814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller WR, Rose GS. Toward a theory of motivational interviewing. The American psychologist. 2009;64(6):527–37. doi: 10.1037/a0016830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bauer MS. Structured Group Psychotherapy for Bipolar Disorder: The Life Goals Program. 2nd ed Springer Publications; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bauer MS. Supporting collaborative practice management: The Life Goals Program. In: Johnson SL, Leahy R, editors. Psychological Treatment of Bipolar Disorder. Guilford Press; New York: 2004. pp. 203–25. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bauer MS, McBride L, Williford WO, Glick H, Kinosian B, Altshuler L, et al. Collaborative care for bipolar disorder: part I. Intervention and implementation in a randomized effectiveness trial. Psychiatric services. 2006;57(7):927–36. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.7.927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]