Abstract

Pluripotent stem cells are unspecialized cells with unlimited self-renewal, and they can be triggered to differentiate into desired specialized cell types. These features provide the basis for an unlimited cell source for innovative cell therapies. Pluripotent cells also allow to study developmental pathways, and to employ them or their differentiated cell derivatives in pharmaceutical testing and biotechnological applications. Via blastocyst complementation, pluripotent cells are a favoured tool for the generation of genetically modified mice. The recently established technology to generate an induced pluripotency status by ectopic co-expression of the transcription factors Oct4, Sox2, Klf4 and c-Myc allows to extending these applications to farm animal species, for which the derivation of genuine embryonic stem cells was not successful so far. Most induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells are generated by retroviral or lentiviral transduction of reprogramming factors. Multiple viral integrations into the genome may cause insertional mutagenesis and may increase the risk of tumour formation. Non-integration methods have been reported to overcome the safety concerns associated with retro and lentiviral-derived iPS cells, such as transient expression of the reprogramming factors using episomal plasmids, and direct delivery of reprogramming mRNAs or proteins. In this review, we focus on the mechanisms of cellular reprogramming and current methods used to induce pluripotency. We also highlight problems associated with the generation of iPS cells. An increased understanding of the fundamental mechanisms underlying pluripotency and refining the methodology of iPS cell generation will have a profound impact on future development and application in regenerative medicine and reproductive biotechnology of farm animals.

Keywords: Reprogramming, Large animal models, Stemness, Chimera, Germline transmission, Induced pluripotent stem cells, Gene delivery

Core tip: The generation of an induced status of pluripotency in somatic cells by ectopic expression of core transcription factors allows to extending advanced genetic modifications and reproductive techniques to species, for which the derivation of genuine embryonic stem cells was not successful till now. The commonly employed viral gene transfer may be genotoxic and therefore non-viral methods for iPS cell derivation are intensively studied. In this review, we focus on the mechanisms of cellular reprogramming and current methods used to induce pluripotency.

INTRODUCTION

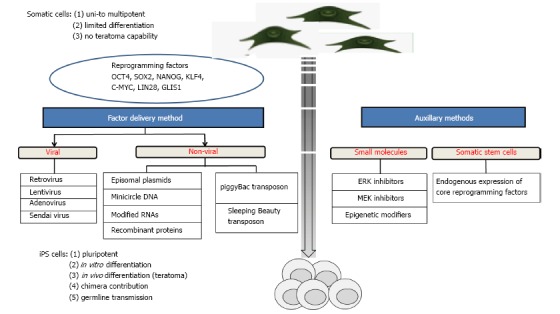

Induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells are defined as differentiated cells that have been experimentally reprogrammed to an embryonic stem (ES) cell-like state. The first generation of murine iPS cells was achieved[1] by retroviral transduction of four core reprogramming factors: Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc. Subsequently, human iPS cells were produced by viral transduction of adult fibroblasts[2,3]. Also a combination of Oct4, Sox2, Nanog and Lin28, was effective for the generation of human iPS cells[4]. An overview of reprogramming cells into iPS cells is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Methodological toolbox for generating induced pluripotent stem cells. iPS: Induced pluripotent stem.

Subsequently, the core reprogramming factors have been successfully used to derive pluripotent cells in various other species, including rhesus monkey[5], rat[6], pig[7], dog[8], cattle[9], horse[10], sheep[11], goat[12] and buffalo[13]. A summary of the generation of iPS cells from different species of livestock is enumerated in Table 1. Importantly, iPS cells could be isolated from several species, in which the isolation of authentic ES cells was not successful despite several attempts since many years[14,15]. In particular, for economically important species, such as farm animals, the availability of authentic iPS cells would have important consequences for reproductive biology and approaches for genetic modification. For agricultural purposes, iPS cells from farm animal species can serve as a valuable genetic engineering tool to boost the generation of livestock with advantageous genes that are important for economic, reproductive and disease resistant traits, or for the study of functional genomics in mammals.

Table 1.

Most advanced achievements in induced pluripotent stem cells from domestic animals

| Domestic species | Cell type | Transduction | Reprogramming factors | Culture medium |

Differentiation |

Chimera | Germline contribution | Ref. | |

| In vitro | In vivo | ||||||||

| Buffalo | Fetal fibroblasts | Retrovirus | OSKM | A | EBs | Teratoma | NA | NA | [13] |

| Cattle | Fetal fibroblasts | Retrovirus | OSKM, OSKMLN, OSKM | B | EBs | Teratoma | NA | NA | [9] |

| Fetal fibroblasts | Plasmid | OSKM | C | EBs | Teratoma | NA | NA | [53] | |

| Dog | Skin fibroblasts | Lentivirus | Human OKSM | J | EBs | Teratoma | NA | NA | [56] |

| Skin fibroblasts | Retrovirus | Mouse OKSM | K | EBs | Teratoma | NA | NA | [54] | |

| Goat | Fibroblasts | Inducible lentivirus | OSKM, SV40 large T and hTERT | A | EBs | Teratoma | NA | NA | [12] |

| Horse | Fetal fibroblasts | PiggyBac transposon | OSKM | E | EBs | Teratoma | NA | NA | [10] |

| Adult fibroblasts | Retrovirus | OSK | F | EBs | Teratoma | NA | NA | [61] | |

| Pig | Mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow | Lentivirus | OSNKLM | G | EBs | NA | Low grade | Two offspring | [26] |

| Fetal fibroblasts | Sleeping Beauty transposon | Mouse OSKM | I | Neuronal lineage | Teratoma | NA | NA | [91] | |

| Rabbit | Skin fibroblasts | Retrovirus | Human OKSM | I | EBs | Teratoma | NA | NA | [72] |

| Sheep | Fetal fibroblasts | Retrovirus | MKOS | D | EBs | Teratoma | Low grade | NA | [25] |

A: DMEM, ESC FBS, L-glutamine, NEAA, β-Me, bFGF, LIF and MEFs; B: DMEM, KSR, L-glutamine, NEAA, β-Me, bFGF and MEFs; C: DMEM/F12 + N2 and Neurobasal with B27, L-glutamine, hLIF, PD0325901, CHIR99021 and MEFs; D: KO-DMEM, SR, L-glutamine, NEAA, 2-Me, human bFGF and MEFs; E: DMEM, FBS, L-Glutamine, NEAA, β-Me, Sodium Pyruvate, LIF, bFGF, Doxycycline, CHIR99021, PD0325901, A83-01, Thiazovivin, B431542 and 1:1 MEFs and EFFs; F: α-MEM, FBS, deoxyribonucleosides, ribonucleoside, glutamax, NEAA, β-Me, ITS, human LIF, βFGF, EGF and MEFs; G: DMEM/F12, KSR, L-glutamine, NEAA, β-Me, FGF and MEFs; H: KO DMEM, KSR, glutamax-L, NEAA, 2-Me, pLIF, forskolin and collagen I; I: DMEM/F12, KSR, L-glutamine, NEAA, β-Me, bFGF and MEFs or gelatinized plates; J: KO DMEM, ESC FBS, bFGF, hLIF and MEFs; K: DMEM/F12, KSR, bFGF, hLIF, PD0325901, CHIR99021 and MEFs. DMEM: Dulbecco’s modified Eagle´s medium; LIF: Leukemia inhibitory factor; IGF1: Insulin-like growth factor 1; NEAA: Nonessential amino acids; FBS: Fetal bovine serum; KO: Knockout; MEM: Minimum essential medium; ITS: Insulin-transferring selenium; bFGF: Basic fibroblastic growth factor; DOX: Doxycycline; EB: Embryonic body; FCS: Fetal calf serum; hSCF: Human stem cell factor; KSR: Knockout serum replacement; MEFs: Mouse embryonic fibroblasts; OKSM: Oct-4, Klf4, Sox2, and c-Myc; OKSMLN: Oct-4, Klf4, Sox2, c-Myc, Lin28 and Nanog; VPA: Valproic acid; Me: Mercaptoethanol.

So far, iPS cells have been successfully produced from fibroblasts[16], pancreas cells[17], leukocytes[18], hepatocytes[19], keratinocytes[20], neural stem cells[21], cord blood cells[22], and other cell types. Together these data suggest that most cell types can be reprogrammed to a pluripotent state, and that the unidirectional lineage commitment can be experimentally overwritten. Certain cell types, such as neuronal progenitors, which exhibit basal expression of one or more of the core reprogramming factors, seem to be ideal for reprogramming[21].

Rodent iPS cells are almost identical to their ES cell counterparts, sharing typical hallmarks of pluripotency such as colony morphology, unlimited self-renewal, in vitro and in vivo differentiation potentials, and contribution to the germline[23,24]. Most iPS lines from farm animal species have not been tested in chimera complementation assays; however some preliminary reports suggest that chimeras and germline transmission can be achieved in sheep and pig[25,26]. iPS cells derived from rodents, humans, monkeys and farm animals share the features of high telomerase activity, expression of alkaline phosphatase, and expression of stemness genes, such as OCT4, SOX2, UTF1 and REX1. The epigenetic status of murine iPS cells has been analysed by bisulfite sequencing and chromatin immuno-precipitation DNA-Sequencing (ChIP-Seq)[27]. Thus the hallmarks for iPS cell characterisation can be enumerated as (1) unlimited self-renewal; (2) in vitro differentiation capacity; (3) in vivo differentiation capacity; (4) chimera contribution; and (5) subsequently germline transmission.

Apart from scientific and ethical hindrances, religious concerns restricted the derivation of human ES cells. To circumvent these concerns, alternative approaches to generate pluripotent cells have been assessed. The alternative approaches include culture of somatic cells with cell extracts isolated from ES cells[28] or oocytes[29], and fusion of somatic cell with pluripotent cell[30]. However, extremely low efficiencies, high technical difficulties and aberrant ploidies of the resulting cells[31,32] did reduce the enthusiasm for these attempts. At the moment, the derivation of iPS cells from human tissues seems to be the most promising alternative. Prior to clinical application of iPS-derivatives, cell survival, functional integration of the cellular transplant and safety of the cell products have to be assessed in informative animal models.

The progress in iPS cell development in farm animals lags behind those in rodents, but large mammalian models may be instrumental for pre-clinical tests of novel cell therapies (Table 2), enhanced pharmaceutical studies and regenerative studies, including the restoration of fertility.

Table 2.

Achievements with induced pluripotent stem cells from rodents, farm animals and humans

| Rodents | Farm animals | Human | |

| iPS cells | √√ | √√ | √√ |

| In vivo differentiation | √√ | √√ | √√ |

| In vitro differentiation | √√ | √√ | √√ |

| Chimera | √√ | √/- | Ethically not allowed |

| Germline transmission | √√ | √/- | Ethically not allowed |

| Follow up generations | √√ | -- | Ethically not allowed |

| Transplantation of iPS cell-derived cells | √√ | √/- | No clinical studies to date1 |

√√: Fully proven; √/-: Partially proven; --: Not achieved yet;

The first clinical study was recently initiated (http://www.riken.jp/en/pr/press/2013/20130730_1). iPS: Induced pluripotent stem.

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

Ontogenesis of an organism and cellular differentiation were thought to be a unidirectional process, where stem and progenitor cells progressively develop to terminally differentiated cells, for example neurons, muscle, and epithelial cells. During ontogenesis the nuclear DNA of most cell types is unchanged, but different epigenetic marks, such as DNA methylation and histon modifications, are set, and lock the cellular potency and cell lineage commitment. This is depicted by the “epigenetic landscape” proposed by Waddington[33].

Already in 1962, Gurdon[34] questioned this view by amphibian cloning; he transplanted nuclei from intestinal cells into irradiated oocytes and obtained vital tadpoles. More than three decades later, the successful cloning of a sheep (Dolly) by SCNT of a mammary epithelial cell to an enucleated oocyte, showed that even mammalian cells can be reprogrammed[35]. This success demonstrated that differentiated cells contain the genetic information to direct ontogenesis of an entire mammalian organisms, and that enucleated oocytes contain pivotal factors for reprogramming of differentiated cell nuclei. However, the identity of the oocyte reprogramming factors remained elusive.

The discoveries that ectopic expression of Antennapedia-a transcription factor was able and sufficient to induce leg structures in Drosophila[36], and that ectopic expression of the mammalian transcription factor MyoD1 converted fibroblasts into myocytes[37] led to the concept of ‘‘master genes’’. A master gene was defined as a key transcription factor that in a hierarchical manner regulates a cascade of critical genes, which in a concerted action induce the cell commitment.

DISCOVERY OF INDUCED PLURIPOTENCY

In 2006, Takahashi et al[1] proved that not a single master factor, but a a combination of four reprogramming factors, Oct4, Sox2, Klf4 and c-Myc, was sufficient to induce the pluripotent status in somatic mammalian cells. The resulting cells were called iPS cells[1]. This discovery offers new opportunities to study developmental biology, regenerative medicine, as well as reproductive biology and biotechnology of farm animals.

IPS cells from farm animals will likely serve as a bridging link between well developed rodent iPS and poorly characterised human iPS (Table 2), supporting the translation of innovative cell therapies from experimental studies to curative treatments. At the moment, human iPS cell application seems to be too risky because of basic lack of knowledge and ethical consideration which forbid certain tests such as chimera assays.

In contrast, research on iPS cells derived from farm animal species is not tainted with ethical concerns. Furthermore, the methodology for generation of iPS cells is relative simple and and is thought to be easily transferable to other mammalian species. Thus farm animal models may turn out to be ideally suited to determine required cell doses, to assess long-term performance, tumorigenicity, applications methods and fate of transplanted cells[38-41].

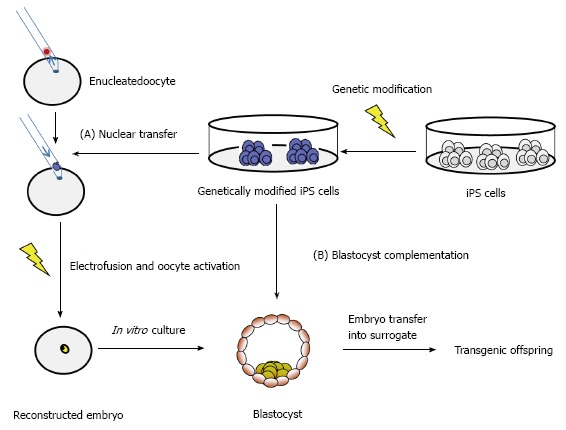

Recent advances in genetic engineering of farm animals allow the generation of precise genetic modifications[42-47], such as the production of immunodeficient pigs[48] which will be instrumental for further advances in preclinical testings of new cell therapies. A boost of recent publications describe iPS cells from buffalo[13], cattle[9,49-53], dog[8,54-56], goat[11,57], horse[10,58-62], pig[7,63-71], rabbit[72-74] and sheep[11,75,76]. The majority of these iPS cells from farm animals showed typical hallmarks of pluripotency, such as differentiation in vivo and teratoma formation. However, most farm animal iPS cultures were not assessed for chimera contribution so far. Preliminary results that porcine iPS cells can contribute to chimera formation in blastocyst complementation were provided recently[71]. Similarly, ovine iPS cells contributed moderately to chimeric lambs after injection into eight-cell stage embryos or blastocysts[25]. These experiments represent an important step in the understanding of mechanistic nature of pluripotency in farm animals. The iPS technology may become instrumental for advanced transgenesis in large mammals (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Application of induced pluripotent stem cells for advanced generation of transgenic animals. iPS: Induced pluripotent stem.

METHODS TO DERIVE IPS CELLS

In recent years, several methods have been established for iPS cell generation (Figure 1), employing the core reprogramming factors as genes, mRNAs or proteins, and auxillary chemical agents, which infer with the involved signalling pathways. Here, the main approaches for the generation of iPS cells are summarized.

Virally-induced iPS cells

There has been extensive amount of work carried out to obtain virally-derived iPS cells employing either retroviruses, lentiviruses, and non-integrating viruses. The first iPS cells have been generated through retroviral transduction of Oct4, Sox2, Klf4 and c-Myc[1]. Disarmed, optimized retro- or lentiviruses can infect mammalian cells with high efficiencies. The use of the pantropic vesicular stomatitis virus G protein (VSVG) was instrumental for viral transduction of a broad spectrum of receptive cells. Interestingly, unstimulated T cells, B cells and hematopoietic stem cells could not be efficiently transduced with the VSVG lentiviruses[77].

Retro- and lentiviruses integrate into the host genome allowing for high expression of the encoded cargo genes. The expression can be temporally confined by employing viral promoters, such as the 5’ long terminal repeat, which are usually silenced by epigenetic mechanisms. Disadvantages of the the viral approach include the limited cargo capacity of maximally 7 kb, the induction of immune responses and potential genotoxic effects. Retro- and lentiviral integrations do not happen randomly in the genome, but show a strong bias for promoter and exonic regions, which may result in dysregulation of endogenous genes. In a retrovirus-based clinical gene therapy of the X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency (X-SCID), two of the treated children independently developed T-cell lymphomas due to viral integration in the neighborhood of the LIM domain only 2 gene[78]. These data highlight the risks of viral-based therapies[78]. Somatic cells derived from retrovirally reprogrammed iPS cells are apparently inconspicious, provided that the c-Myc transgene is silenced[19,79]. Retroviral reprogramming may evoke an immunogenicity of iPS cells[80]. Human iPS cell-like cells can be formed through transduction with lentiviruses, which do not carry reprogramming factors. The “pseudo” iPS cells were induced by viral encoded microRNA expression[81].

Alternative to integrating retroviruses, non-integrating adenoviruses can be used for reprogramming[17,82]. Another non-integrating virus is represented by the Sendai virus system. Sendai viruses enable efficient production of iPS cells and later on elimination of the viral vector[83]. Though viral mediated gene transfer offers high efficiency in generation of iPS cells, they require specific safety conditions for their handling.

Non-virally-derived iPS cells

The generation of iPS cells without viral transduction is preferable for regenerative medicine. Non-viral methods of reprogramming include episomal vectors[84], minicircle DNAs[85], plasmid vectors[86], small molecules[87], mRNAs[88], recombinant proteins[89] and transposons like piggyBac[90] and Sleeping Beauty[91]. In comparison to viral systems, non-viral approaches such as transposons are able to carry large DNA cargo into the host cell, they are non-infectious and do not evoke immune responses.

Episomal vectors

Episomal vectors for reprogramming of somatic cells were recently described[84]. In this method, reprogramming of fibroblasts was carried out by transfecting with the episomal vector oriP/Epstein-Barr nuclear antigen-1. This vector was chosen because it can be removed after reprogramming by a drug selection method. The iPS cells generated through this method show similar morphology and expression patterns to ES cells. Further, they were able to form teratomas in immunocompromised mice. As there was no integration into the host genome, transgene free iPS cells may be selected through further sub-cloning. Despite these advantages, this method yields low reprogramming efficiency in human fibroblasts at about three to six iPS colonies per 106 input cells[84].

Minicircle vectors

Minicircle vectors are produced by the recombinatorial elimination of the bacterial backbone of the original plasmids. Minicircles containing the four reprogramming factors Oct4, Nanog, Lin28, and Sox2 in addition to an enhanced green fluorescent protein were used to obtain human iPS cells[85]. The group excised the bacterial backbone from the plasmid by taking advantage of the PhiC31-based intramolecular recombination system, which cleaves away the undesired bacterial plasmid backbones, leaving minicircle DNA to be purified containing the desired reprogramming factors[85]. It was claimed that minicircle DNA benefited from higher transfection efficiency compared to the parental plasmids. They also have longer ectopic expression, which is due to the lower activation of exogenous silencing mechanisms. Later, other groups reproduced the minicircle approach for reprogramming[92,93].

Small molecules

Nowadays, small molecules and chemicals are assessed to enhance reprogramming efficiency and iPS cell generation. The idea behind their use is to substitute core reprogramming factors with small molecules, which will serve to enhance the reprogramming. Shi et al[94] showed that neural progenitor cells, which endogenously express Sox2, were reprogrammed only by ectopic expression of Oct4 and Klf4. They also showed that this process was supported by the G9a histone methyltransferase inhibitor, BIX-01294 (BIX). Ichida et al[95] used small molecules (RepSox2) for replacing transcription factors (Sox2) by inhibiting transforming growth factor-β signalling. In this direction, Lee et al[96] used magnetic nanoparticle-based transfection method that employs biodegradable cationic polymer PEI-coated super paramagnetic nanoparticles for iPS cells generation. Recently, the L-channel calcium agonist, BayK8644, was assessed to improve generation of iPS cells[87] and it was claimed that BayK8644 does not directly cause epigenetic modifications as it works upstream in cell signalling pathways and can therefore avoid unwanted modifications. A more comprehensive list of small molecules involved in the iPS cells generation and their mechanism has been reviewed recently[97].

Transposon systems

The recent development of hyperactive transposase enzymes makes transposon systems an interesting alternative to viral based methods. The commonly employed Sleeping Beauty, piggyBac and Tol2 transposon systems are relatively simple organized, and the essential components can be separated on two plasmids. One plasmid carries the inverted terminal repeats (ITR) flanking the transgene, the other plasmid carries an expression cassette for the respective transposase enzyme. Upon co-transfer of both plasmids into a cell, the transposase becomes expressed and subsequently transposes the ITR-flanked transgene into the genome. Importantly, only the desired transgenes becomes integrated by a cut-and-paste mechanism, whereas the plasmid backbones are degraded. On a genomic scale transposon integrations appear to happen at random, without a bias for promoter and gene-containing regions. The integrated transposon can be removed seamlessly by supplying the transposase in trans[98], which makes the system more attractive and relevant in producing the safe and clean iPS cells. Up to six reprogramming factors have been connected by self-cleaving peptide sequences allowing for coexpression from a single cassette[91,99-103]. Individual proteins are then produced by the self-cleaving peptide[104-106].

Reprogramming with protein factors

The discussed transposon and episomal systems still require the introduction of cargo DNA into the cells[106]. Delivery of reprogramming factors as proteins is an obvious alternative. In 2009, transgene-free iPS cells were produced with proteins of reprogramming factors[107]. Therefor recombinant reprogramming proteins were produced as fusion proteins containing cell penetrating peptides. Repeated supplementation of the culture media of fibroblasts converted them to iPS cells. However, the protein-based reprogramming approach has not found widespread use, mainly due to relative low reprogramming efficiencies, and high costs for repeated treatments with protein factors.

mRNAs and microRNAs

The most recent trend in the field of non-viral iPS generation is reprogramming by using RNA molecules. Recently, modified mRNAs encoding reprogramming factors were employed to generate iPS cells with high efficiency[108]. Messenger RNAs are an ideal vehicle for reprogramming, because they do not bear the risk of integrational mutagenesis, they can be transduced to cells with high efficiency, and they can be combined in desired ratios of the individual factor encoding transcripts[108]. Disadvantages of mRNAs are the short half-life of -10 h, and that innate immune responses must be inhibited to allow for the full effects[109].

Recently, it was shown that micro RNAs (miR) expression is sufficient to induce pluripotency[110-112]. Two independent groups reported iPS cell generation by delivery of miR302, or miR200c, miR302, and miR369[113,114]. These miR-derived iPS cells were indistinguishable from conventionally generated iPS cells. MicroR reprogramming seems to have advantages for cellular reprogramming[114-116], for example it avoids the need of transducing proto-oncogenic transcription factors[117,118]. However, it needs to be assessed whether this approach will be successful in other species, since the underlying mechanisms are not well understood[119].

MOLECULAR FACTORS REGULATING REPROGRAMMING

The core factors for reprogramming are Oct4, Nanog, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc and Lin28. These genetic factors reprogram cells by regulating critical signalling pathways, epigenetic modifications and micro RNAs[114].

Reprogramming by core transcription factors

Oct4 is the best studied regulator of pluripotency. Oct4 expression is confined to early embryonic cells, germ line cells and cultured pluripotent stem cells, where it activates the gene transcription of stemness gene[120]. Oct4 protein cooperates with stemness factors such as Nanog and Sox2, but it also interacts with Polycomb group proteins[120], which are important repressors of transcription. Sox2 is a transcription factor that acts as coactivator of Oct4[121]. Binding of Oct4/Sox2 dimers to the promoter sequences of Oct4 and Nanog genes upregulate their transcription[122]. Nanog is a homeobox-containing transcription factor stabilizing the stemness network[122]. Klf4 is a zinc finger-containing transcription factor which regulates the expression of Oct4, Sox2 and Nanog[123-125]. Over-expression of Klf4 in ES cells increased the expression of Oct4 which further improve the self-renewal ability[126]. c-Myc enhances the efficiency and speed of reprogramming[127]. LIN28 promotes the expression of Oct4 at the posttranscriptional level by direct binding to its mRNA[128]. Recently, Glis1 has been identified as a substitute for c-Myc[129]. Glis1 transactivate the genes of Wnt ligands, Lin28a, Nanog, Mycn, Mycl1, and Foxa2[129].

The aspect of whether the species-specificity of reprogramming factors is relevant for proper reprogramming, is not well understood. In principle, the essential domains of the reprogramming factors are highly conserved between mammalian species, and several publications showed successful reprogramming with human and murine sequences in other species[5-13,130].

APPLICATIONS OF IPS CELLS

Modeling of human diseases and preclinical trials

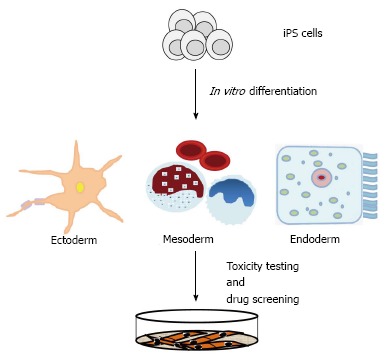

The potential applications of iPS cells will impact regenerative medicine, pharmaceutical industry, and animal biotechnology[131]. Human iPS cells could be utilized for curative treatments, to studying onset and disease progression in vitro, and to test potential therapeutic in high throughput screens[114,131,132]. The production of disease-specific iPS cells has found widespread use in recent years[133-136]. Disease-specific iPS cells provide a unique resource to obtain a molecular understanding of disease onset and progression[131,132]. Induced PS-derived differentiated cells will allow to carry out in vitro drug screening (Figure 3), and to test therapeutic interventions[131]. In mice, Fanconi anemia and sickle cell anemia have been successfully corrected by using iPS cells[131,133-136].

Figure 3.

IPS cell technology contributes to disease modelling and drug discovery. iPS: Induced pluripotent stem.

However with regard to potential curative treatments, the functionality, safety, and lack of tumorigenicity of iPS-derived cells have to be assessed in appropriate animal models bearing significant physiological and anatomical similarities to humans (Table 2). Hence, animal models could be contributed tremendously to a better understanding of disease mechanisms and therapeutic interventions. In addition, iPS cells from monkey[5], porcine[41,26], canine[8] and cattle[9] would be useful in animal biotechnology such as making precise genetic engineering for improved production traits and products[137,138].

Advanced transgenesis in large mammals

Transgenic farm animals can serve as excellent models of human diseases and during the past few years transgenic farm animals have gained renewed popularity. This is due to the availability of annotated genome depositories of the major domestic species and other organisms (for example: www.ensembl.org; or www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome), and due the introduction of active methods of transgenesis, which dramatically increased the success rates[42,43]. The repertoire of molecular tools now allows the precise modification of large mammalian genomes at rapid pace and has led to a recent boost in this area. The development of genuine iPS cells from domestic species will contribute to these advances and allow to perform desired genetic modifications via high throughput screens in vitro, and then use either SCNT[47] or blastocyst complementation for the generation of transgenic offspring (Figure 3). However at the moment most of the iPS cells cultures from different domestic species have not been tested for their capability to contribute to chimera formation, and only preliminary data are available[25,26]. Thus reinforced efforts to assess the potential of current livestock iPS cell lines for chimera contribution and germ cell differentiation are required. The majority of current livestock iPS cell lines are generated with retro- or lentiviral reprogramming approaches (Table 1), and the opportunities to assess alternative non-viral approaches are not widely assessed[10,56,106]. Also the potential of auxillary small molecular inhibitors of stemness signaling pathway is not exploited for livestock iPS cells. Potentially, high throughput screens to identify small molecules with species-specific activity are required. It is anticipated that these approaches will lead to livestock iPS cells, which will make a significant impact for future genetic modifications of these species.

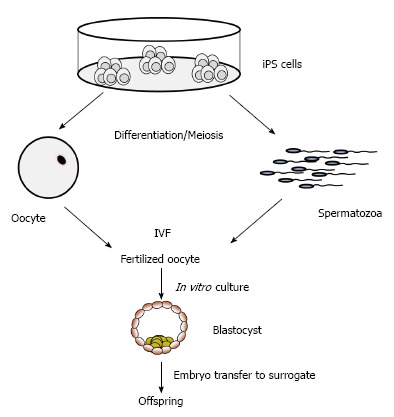

Preservation of genetic resources and endangered breeds

The iPS technology has the potential to preserve endangered animals and highly valuable genotypes in the near future[139]. Cryopreservation of cells and tissues is an important and useful approach for genetic preservation of valuable breeds and for conservation of endangered wild and domestic species. For highly endangered species, the derivation of iPS cells may become a method to prevent extinction. For example, iPS cells have been produced from endangered snow leopard[140], drill and white rhinoceros[139]. The iPS cells generated can be easily expanded for banking of genetic material, or used as donor cells for SCNT. Potentially, iPS cells from endangered species may be differentiated into mature oocytes and spermatozoa (Figure 4), which might be employed for in vitro embryo production[139,140]. The differentiation of livestock iPS cells to functional gametes in vitro have not been achieved yet, however the current pace in developing fine-tuned protocols for in vitro differentiation of desired cell types, and the progress in inducing meiosis support the notion that the generation of fully functional spermatozoa and oocytes may be feasible. The possibility to obtain fully functional spermatozoa and oocytes from iPS cells of domestic and wild species would has far reaching consequences for maintenance of endangered species, as well as for breeding and genomic selection programs of domestic species. Even potential applications for infertility treatments in humans may become feasible[141,142].

Figure 4.

Application of induced pluripotent stem cells for in vitro generation of gametes. iPS: Induced pluripotent stem; IVF: In vitro fertilization.

PROSPECTS OF FARM ANIMAL IPS CELLS IN PRECLINICAL STUDIES

The generation of iPS cells has opened new vista to understand pluripotency, disease onset and progression, and to develop regenerative medicine[132]. However, before the clinical application of iPS cell-derived therapies can be envisioned, the low efficiency and kinetics of iPS cell formation, the risks of insertional mutagenesis, reactivation of silenced ectopic transgenes and potential tumor formation have to be assessed and solved[131]. An important aspect is the biosafety of transplanted derivatives of iPS cells[132]. A number of reports showed that iPS cell lines could contain genetic mutations, copy number variations, and epigenetic mutations[132,143-145]. These aberrant changes may increase the tumorigenicity of iPS and iPS-derived cells. Retro- and lentiviruses are commonly used to introduce the reprogramming factors into differentiated cells, which can increase the immunogenicity[146].

Farm animals represent informative model organisms, which seem to be suitable to assess obstacles and risks in longitudinal pre-clinical studies[147]. In contrast to rodent models, they are more similar to humans with respect to life-span, physiology, metabolism and pathophysiology[148,149]. Large mammalian models will allow to determining required cell doses to obtain therapeutic effects, to follow the fate of transplanted cells and their functional integration in the host tissue[150]. Thus the research on pluripotent stem cells from farm animals will contribute to the development of innovative cells therapies for human patients.

Footnotes

P- Reviewer: Günter L, Sanal MG S- Editor: Gong XM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

Supported by CREST fellowship from Department of Biotechnology, Ministry of Science and Technology, Government of India (DK); International fellowship for PhD from ICAR (TRT), Government of India; International training in generation of iPS cells from NAIP, ICAR, Government of India (TA).

Conflict-of-interest: The authors declare there are no competing interests.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: July 17, 2014

First decision: August 14, 2014

Article in press: December 18, 2014

References

- 1.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Okita K, Ichisaka T, Yamanaka S. Generation of germline-competent induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2007;448:313–317. doi: 10.1038/nature05934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, Narita M, Ichisaka T, Tomoda K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131:861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu J, Vodyanik MA, Smuga-Otto K, Antosiewicz-Bourget J, Frane JL, Tian S, Nie J, Jonsdottir GA, Ruotti V, Stewart R, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science. 2007;318:1917–1920. doi: 10.1126/science.1151526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu H, Zhu F, Yong J, Zhang P, Hou P, Li H, Jiang W, Cai J, Liu M, Cui K, et al. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells from adult rhesus monkey fibroblasts. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:587–590. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liao J, Cui C, Chen S, Ren J, Chen J, Gao Y, Li H, Jia N, Cheng L, Xiao H, et al. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cell lines from adult rat cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:11–15. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Esteban MA, Xu J, Yang J, Peng M, Qin D, Li W, Jiang Z, Chen J, Deng K, Zhong M, et al. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cell lines from Tibetan miniature pig. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:17634–17640. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.008938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shimada H, Nakada A, Hashimoto Y, Shigeno K, Shionoya Y, Nakamura T. Generation of canine induced pluripotent stem cells by retroviral transduction and chemical inhibitors. Mol Reprod Dev. 2010;77:2. doi: 10.1002/mrd.21117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Han X, Han J, Ding F, Cao S, Lim SS, Dai Y, Zhang R, Zhang Y, Lim B, Li N. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells from bovine embryonic fibroblast cells. Cell Res. 2011;21:1509–1512. doi: 10.1038/cr.2011.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nagy K, Sung HK, Zhang P, Laflamme S, Vincent P, Agha-Mohammadi S, Woltjen K, Monetti C, Michael IP, Smith LC, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from equine fibroblasts. Stem Cell Rev. 2011;7:693–702. doi: 10.1007/s12015-011-9239-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bao L, He L, Chen J, Wu Z, Liao J, Rao L, Ren J, Li H, Zhu H, Qian L, et al. Reprogramming of ovine adult fibroblasts to pluripotency via drug-inducible expression of defined factors. Cell Res. 2011;21:600–608. doi: 10.1038/cr.2011.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ren J, Pak Y, He L, Qian L, Gu Y, Li H, Rao L, Liao J, Cui C, Xu X, et al. Generation of hircine-induced pluripotent stem cells by somatic cell reprogramming. Cell Res. 2011;21:849–853. doi: 10.1038/cr.2011.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deng Y, Liu Q, Luo C, Chen S, Li X, Wang C, Liu Z, Lei X, Zhang H, Sun H, et al. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells from buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) fetal fibroblasts with buffalo defined factors. Stem Cells Dev. 2012;21:2485–2494. doi: 10.1089/scd.2012.0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nowak-Imialek M, Kues W, Carnwath JW, Niemann H. Pluripotent stem cells and reprogrammed cells in farm animals. Microsc Microanal. 2011;17:474–497. doi: 10.1017/S1431927611000080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brevini TA, Pennarossa G, Gandolfi F. No shortcuts to pig embryonic stem cells. Theriogenology. 2010;74:544–550. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2010.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lowry WE, Richter L, Yachechko R, Pyle AD, Tchieu J, Sridharan R, Clark AT, Plath K. Generation of human induced pluripotent stem cells from dermal fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:2883–2888. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711983105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stadtfeld M, Brennand K, Hochedlinger K. Reprogramming of pancreatic beta cells into induced pluripotent stem cells. Curr Biol. 2008;18:890–894. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hanna J, Markoulaki S, Schorderet P, Carey BW, Beard C, Wernig M, Creyghton MP, Steine EJ, Cassady JP, Foreman R, et al. Direct reprogramming of terminally differentiated mature B lymphocytes to pluripotency. Cell. 2008;133:250–264. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aoi T, Yae K, Nakagawa M, Ichisaka T, Okita K, Takahashi K, Chiba T, Yamanaka S. Generation of pluripotent stem cells from adult mouse liver and stomach cells. Science. 2008;321:699–702. doi: 10.1126/science.1154884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aasen T, Raya A, Barrero MJ, Garreta E, Consiglio A, Gonzalez F, Vassena R, Bilić J, Pekarik V, Tiscornia G, et al. Efficient and rapid generation of induced pluripotent stem cells from human keratinocytes. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:1276–1284. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim JB, Greber B, Araúzo-Bravo MJ, Meyer J, Park KI, Zaehres H, Schöler HR. Direct reprogramming of human neural stem cells by OCT4. Nature. 2009;461:649–643. doi: 10.1038/nature08436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takenaka C, Nishishita N, Takada N, Jakt LM, Kawamata S. Effective generation of iPS cells from CD34+ cord blood cells by inhibition of p53. Exp Hematol. 2010;38:154–162. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Daley GQ, Lensch MW, Jaenisch R, Meissner A, Plath K, Yamanaka S. Broader implications of defining standards for the pluripotency of iPSCs. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:200–201; author reply 202. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ellis J, Bruneau BG, Keller G, Lemischka IR, Nagy A, Rossant J, Srivastava D, Zandstra PW, Stanford WL. Alternative induced pluripotent stem cell characterization criteria for in vitro applications. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:198–199; author reply 202. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sartori C, DiDomenico AI, Thomson AJ, Milne E, Lillico SG, Burdon TG, Whitelaw CB. Ovine-induced pluripotent stem cells can contribute to chimeric lambs. Cell Reprogram. 2012;14:8–19. doi: 10.1089/cell.2011.0050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.West FD, Uhl EW, Liu Y, Stowe H, Lu Y, Yu P, Gallegos-Cardenas A, Pratt SL, Stice SL. Brief report: chimeric pigs produced from induced pluripotent stem cells demonstrate germline transmission and no evidence of tumor formation in young pigs. Stem Cells. 2011;29:1640–1643. doi: 10.1002/stem.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pawlak M, Jaenisch R. De novo DNA methylation by Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b is dispensable for nuclear reprogramming of somatic cells to a pluripotent state. Genes Dev. 2011;25:1035–1040. doi: 10.1101/gad.2039011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu YN, Guan N, Wang ZD, Shan ZY, Shen JL, Zhang QH, Jin LH, Lei L. ES cell extract-induced expression of pluripotent factors in somatic cells. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 2009;292:1229–1234. doi: 10.1002/ar.20919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miyamoto K, Tsukiyama T, Yang Y, Li N, Minami N, Yamada M, Imai H. Cell-free extracts from mammalian oocytes partially induce nuclear reprogramming in somatic cells. Biol Reprod. 2009;80:935–943. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.073676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Silva J, Chambers I, Pollard S, Smith A. Nanog promotes transfer of pluripotency after cell fusion. Nature. 2006;441:997–1001. doi: 10.1038/nature04914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tada M, Takahama Y, Abe K, Nakatsuji N, Tada T. Nuclear reprogramming of somatic cells by in vitro hybridization with ES cells. Curr Biol. 2001;11:1553–1558. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00459-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ying QL, Nichols J, Evans EP, Smith AG. Changing potency by spontaneous fusion. Nature. 2002;416:545–548. doi: 10.1038/nature729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Waddington CH. The Strategy of the genes. A discussion of some aspects of theoretical biology. London: Allen and Unwin; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gurdon JB. The developmental capacity of nuclei taken from intestinal epithelium cells of feeding tadpoles. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1962;10:622–640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilmut I, Schnieke AE, McWhir J, Kind AJ, Campbell KH. Viable offspring derived from fetal and adult mammalian cells. Nature. 1997;385:810–813. doi: 10.1038/385810a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schneuwly S, Klemenz R, Gehring WJ. Redesigning the body plan of Drosophila by ectopic expression of the homoeotic gene Antennapedia. Nature. 1987;325:816–818. doi: 10.1038/325816a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Davis RL, Weintraub H, Lassar AB. Expression of a single transfected cDNA converts fibroblasts to myoblasts. Cell. 1987;51:987–1000. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90585-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kawamura M, Miyagawa S, Miki K, Saito A, Fukushima S, Higuchi T, Kawamura T, Kuratani T, Daimon T, Shimizu T, et al. Feasibility, safety, and therapeutic efficacy of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocyte sheets in a porcine ischemic cardiomyopathy model. Circulation. 2012;126:S29–S37. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.084343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kawamura M, Miyagawa S, Fukushima S, Saito A, Miki K, Ito E, Sougawa N, Kawamura T, Daimon T, Shimizu T, et al. Enhanced survival of transplanted human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes by the combination of cell sheets with the pedicled omental flap technique in a porcine heart. Circulation. 2013;128:S87–S94. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang F, Song G, Li X, Gu W, Shen Y, Chen M, Yang B, Qian L, Cao K. Transplantation of iPSc ameliorates neural remodeling and reduces ventricular arrhythmias in a post-infarcted swine model. J Cell Biochem. 2014;115:531–539. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mizukami Y, Abe T, Shibata H, Makimura Y, Fujishiro SH, Yanase K, Hishikawa S, Kobayashi E, Hanazono Y. MHC-matched induced pluripotent stem cells can attenuate cellular and humoral immune responses but are still susceptible to innate immunity in pigs. PLoS One. 2014;9:e98319. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Garrels W, Ivics Z, Kues WA. Precision genetic engineering in large mammals. Trends Biotechnol. 2012;30:386–393. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2012.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Le Provost F, Lillico S, Passet B, Young R, Whitelaw B, Vilotte JL. Zinc finger nuclease technology heralds a new era in mammalian transgenesis. Trends Biotechnol. 2010;28:134–141. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Matsushita H, Sano A, Wu H, Jiao JA, Kasinathan P, Sullivan EJ, Wang Z, Kuroiwa Y. Triple immunoglobulin gene knockout transchromosomic cattle: bovine lambda cluster deletion and its effect on fully human polyclonal antibody production. PLoS One. 2014;9:e90383. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yu Y, Wang Y, Tong Q, Liu X, Su F, Quan F, Guo Z, Zhang Y. A site-specific recombinase-based method to produce antibiotic selectable marker free transgenic cattle. PLoS One. 2013;8:e62457. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ivics Z, Garrels W, Mátés L, Yau TY, Bashir S, Zidek V, Landa V, Geurts A, Pravenec M, Rülicke T, et al. Germline transgenesis in pigs by cytoplasmic microinjection of Sleeping Beauty transposons. Nat Protoc. 2014;9:810–827. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2014.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fan N, Chen J, Shang Z, Dou H, Ji G, Zou Q, Wu L, He L, Wang F, Liu K, et al. Piglets cloned from induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Res. 2013;23:162–166. doi: 10.1038/cr.2012.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee K, Kwon DN, Ezashi T, Choi YJ, Park C, Ericsson AC, Brown AN, Samuel MS, Park KW, Walters EM, et al. Engraftment of human iPS cells and allogeneic porcine cells into pigs with inactivated RAG2 and accompanying severe combined immunodeficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:7260–7265. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1406376111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cao H, Yang P, Pu Y, Sun X, Yin H, Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Li Y, Liu Y, Fang F, et al. Characterization of bovine induced pluripotent stem cells by lentiviral transduction of reprogramming factor fusion proteins. Int J Biol Sci. 2012;8:498–511. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.3723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hu PF, Guan WJ, Li XC, Ma YH. Construction of recombinant proteins for reprogramming of endangered Luxi cattle fibroblast cells. Mol Biol Rep. 2012;39:7175–7182. doi: 10.1007/s11033-012-1549-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Malaver-Ortega LF, Sumer H, Liu J, Verma PJ. The state of the art for pluripotent stem cells derivation in domestic ungulates. Theriogenology. 2012;78:1749–1762. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2012.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sumer H, Liu J, Malaver-Ortega LF, Lim ML, Khodadadi K, Verma PJ. NANOG is a key factor for induction of pluripotency in bovine adult fibroblasts. J Anim Sci. 2011;89:2708–2716. doi: 10.2527/jas.2010-3666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huang B, Li T, Alonso-Gonzalez L, Gorre R, Keatley S, Green A, Turner P, Kallingappa PK, Verma V, Oback B. A virus-free poly-promoter vector induces pluripotency in quiescent bovine cells under chemically defined conditions of dual kinase inhibition. PLoS One. 2011;6:e24501. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Koh S, Thomas R, Tsai S, Bischoff S, Lim JH, Breen M, Olby NJ, Piedrahita JA. Growth requirements and chromosomal instability of induced pluripotent stem cells generated from adult canine fibroblasts. Stem Cells Dev. 2013;22:951–963. doi: 10.1089/scd.2012.0393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Whitworth DJ, Ovchinnikov DA, Wolvetang EJ. Generation and characterization of LIF-dependent canine induced pluripotent stem cells from adult dermal fibroblasts. Stem Cells Dev. 2012;21:2288–2297. doi: 10.1089/scd.2011.0608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Luo J, Suhr ST, Chang EA, Wang K, Ross PJ, Nelson LL, Venta PJ, Knott JG, Cibelli JB. Generation of leukemia inhibitory factor and basic fibroblast growth factor-dependent induced pluripotent stem cells from canine adult somatic cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2011;20:1669–1678. doi: 10.1089/scd.2011.0127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Song H, Li H, Huang M, Xu D, Gu C, Wang Z, Dong F, Wang F. Induced pluripotent stem cells from goat fibroblasts. Mol Reprod Dev. 2013;80:1009–1017. doi: 10.1002/mrd.22266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Donadeu FX. Equine induced pluripotent stem cells or how to turn skin cells into neurons: horse tissues a la carte? Equine Vet J. 2014;46:534–537. doi: 10.1111/evj.12300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hackett CH, Greve L, Novakofski KD, Fortier LA. Comparison of gene-specific DNA methylation patterns in equine induced pluripotent stem cell lines with cells derived from equine adult and fetal tissues. Stem Cells Dev. 2012;21:1803–1811. doi: 10.1089/scd.2011.0055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Breton A, Sharma R, Diaz AC, Parham AG, Graham A, Neil C, Whitelaw CB, Milne E, Donadeu FX. Derivation and characterization of induced pluripotent stem cells from equine fibroblasts. Stem Cells Dev. 2013;22:611–621. doi: 10.1089/scd.2012.0052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Whitworth DJ, Ovchinnikov DA, Sun J, Fortuna PR, Wolvetang EJ. Generation and characterization of leukemia inhibitory factor-dependent equine induced pluripotent stem cells from adult dermal fibroblasts. Stem Cells Dev. 2014;23:1515–1523. doi: 10.1089/scd.2013.0461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sharma R, Livesey MR, Wyllie DJ, Proudfoot C, Whitelaw CB, Hay DC, Donadeu FX. Generation of functional neurons from feeder-free, keratinocyte-derived equine induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2014;23:1524–1534. doi: 10.1089/scd.2013.0565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wu Z, Chen J, Ren J, Bao L, Liao J, Cui C, Rao L, Li H, Gu Y, Dai H, et al. Generation of pig induced pluripotent stem cells with a drug-inducible system. J Mol Cell Biol. 2009;1:46–54. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjp003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ruan W, Han J, Li P, Cao S, An Y, Lim B, Li N. A novel strategy to derive iPS cells from porcine fibroblasts. Sci China Life Sci. 2011;54:553–559. doi: 10.1007/s11427-011-4179-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ezashi T, Matsuyama H, Telugu BP, Roberts RM. Generation of colonies of induced trophoblast cells during standard reprogramming of porcine fibroblasts to induced pluripotent stem cells. Biol Reprod. 2011;85:779–787. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.111.092809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cheng D, Guo Y, Li Z, Liu Y, Gao X, Gao Y, Cheng X, Hu J, Wang H. Porcine induced pluripotent stem cells require LIF and maintain their developmental potential in early stage of embryos. PLoS One. 2012;7:e51778. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lahm H, Doppler S, Dreßen M, Werner A, Adamczyk K, Schrambke D, Brade T, Laugwitz KL, Deutsch MA, Schiemann M, et al. Live fluorescent RNA-based detection of pluripotency gene expression in embryonic and induced pluripotent cells of different species. Stem Cells. 2015;33:392–402. doi: 10.1002/stem.1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Liu K, Ji G, Mao J, Liu M, Wang L, Chen C, Liu L. Generation of porcine-induced pluripotent stem cells by using OCT4 and KLF4 porcine factors. Cell Reprogram. 2012;14:505–513. doi: 10.1089/cell.2012.0047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hall VJ, Kristensen M, Rasmussen MA, Ujhelly O, Dinnyés A, Hyttel P. Temporal repression of endogenous pluripotency genes during reprogramming of porcine induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Reprogram. 2012;14:204–216. doi: 10.1089/cell.2011.0089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ezashi T, Telugu BP, Alexenko AP, Sachdev S, Sinha S, Roberts RM. Derivation of induced pluripotent stem cells from pig somatic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:10993–10998. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905284106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.West FD, Terlouw SL, Kwon DJ, Mumaw JL, Dhara SK, Hasneen K, Dobrinsky JR, Stice SL. Porcine induced pluripotent stem cells produce chimeric offspring. Stem Cells Dev. 2010;19:1211–1220. doi: 10.1089/scd.2009.0458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Osteil P, Tapponnier Y, Markossian S, Godet M, Schmaltz-Panneau B, Jouneau L, Cabau C, Joly T, Blachère T, Gócza E, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cells derived from rabbits exhibit some characteristics of naïve pluripotency. Biol Open. 2013;2:613–628. doi: 10.1242/bio.20134242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tancos Z, Nemes C, Polgar Z, Gocza E, Daniel N, Stout TA, Maraghechi P, Pirity MK, Osteil P, Tapponnier Y, et al. Generation of rabbit pluripotent stem cell lines. Theriogenology. 2012;78:1774–1786. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2012.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Honda A, Hirose M, Hatori M, Matoba S, Miyoshi H, Inoue K, Ogura A. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells in rabbits: potential experimental models for human regenerative medicine. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:31362–31369. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.150540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Li Y, Cang M, Lee AS, Zhang K, Liu D. Reprogramming of sheep fibroblasts into pluripotency under a drug-inducible expression of mouse-derived defined factors. PLoS One. 2011;6:e15947. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Liu J, Balehosur D, Murray B, Kelly JM, Sumer H, Verma PJ. Generation and characterization of reprogrammed sheep induced pluripotent stem cells. Theriogenology. 2012;77:338–46.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Amirache F, Lévy C, Costa C, Mangeot PE, Torbett BE, Wang CX, Nègre D, Cosset FL, Verhoeyen E. Mystery solved: VSV-G-LVs do not allow efficient gene transfer into unstimulated T cells, B cells, and HSCs because they lack the LDL receptor. Blood. 2014;123:1422–1424. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-11-540641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hacein-Bey-Abina S, Von Kalle C, Schmidt M, McCormack MP, Wulffraat N, Leboulch P, Lim A, Osborne CS, Pawliuk R, Morillon E, et al. LMO2-associated clonal T cell proliferation in two patients after gene therapy for SCID-X1. Science. 2003;302:415–419. doi: 10.1126/science.1088547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nakagawa M, Koyanagi M, Tanabe K, Takahashi K, Ichisaka T, Aoi T, Okita K, Mochiduki Y, Takizawa N, Yamanaka S. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells without Myc from mouse and human fibroblasts. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:101–106. doi: 10.1038/nbt1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhao T, Zhang ZN, Rong Z, Xu Y. Immunogenicity of induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2011;474:212–215. doi: 10.1038/nature10135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kane NM, Nowrouzi A, Mukherjee S, Blundell MP, Greig JA, Lee WK, Houslay MD, Milligan G, Mountford JC, von Kalle C, et al. Lentivirus-mediated reprogramming of somatic cells in the absence of transgenic transcription factors. Mol Ther. 2010;18:2139–2145. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tashiro K, Inamura M, Kawabata K, Sakurai F, Yamanishi K, Hayakawa T, Mizuguchi H. Efficient adipocyte and osteoblast differentiation from mouse induced pluripotent stem cells by adenoviral transduction. Stem Cells. 2009;27:1802–1811. doi: 10.1002/stem.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Fusaki N, Ban H, Nishiyama A, Saeki K, Hasegawa M. Efficient induction of transgene-free human pluripotent stem cells using a vector based on Sendai virus, an RNA virus that does not integrate into the host genome. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B Phys Biol Sci. 2009;85:348–362. doi: 10.2183/pjab.85.348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yu J, Hu K, Smuga-Otto K, Tian S, Stewart R, Slukvin II, Thomson JA. Human induced pluripotent stem cells free of vector and transgene sequences. Science. 2009;324:797–801. doi: 10.1126/science.1172482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Jia F, Wilson KD, Sun N, Gupta DM, Huang M, Li Z, Panetta NJ, Chen ZY, Robbins RC, Kay MA, et al. A nonviral minicircle vector for deriving human iPS cells. Nat Methods. 2010;7:197–199. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Okita K, Hong H, Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Generation of mouse-induced pluripotent stem cells with plasmid vectors. Nat Protoc. 2010;5:418–428. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Desponts C, Ding S. Using small molecules to improve generation of induced pluripotent stem cells from somatic cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;636:207–218. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-691-7_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Warren L, Manos PD, Ahfeldt T, Loh YH, Li H, Lau F, Ebina W, Mandal PK, Smith ZD, Meissner A, et al. Highly efficient reprogramming to pluripotency and directed differentiation of human cells with synthetic modified mRNA. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:618–630. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kim D, Kim CH, Moon JI, Chung YG, Chang MY, Han BS, Ko S, Yang E, Cha KY, Lanza R, et al. Generation of human induced pluripotent stem cells by direct delivery of reprogramming proteins. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:472–476. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Woltjen K, Michael IP, Mohseni P, Desai R, Mileikovsky M, Hämäläinen R, Cowling R, Wang W, Liu P, Gertsenstein M, et al. piggyBac transposition reprograms fibroblasts to induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2009;458:766–770. doi: 10.1038/nature07863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kues WA, Herrmann D, Barg-Kues B, Haridoss S, Nowak-Imialek M, Buchholz T, Streeck M, Grebe A, Grabundzija I, Merkert S, et al. Derivation and characterization of sleeping beauty transposon-mediated porcine induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2013;22:124–135. doi: 10.1089/scd.2012.0382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Chabot S, Orio J, Schmeer M, Schleef M, Golzio M, Teissié J. Minicircle DNA electrotransfer for efficient tissue-targeted gene delivery. Gene Ther. 2013;20:62–68. doi: 10.1038/gt.2011.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Yoshida Y, Takahashi K, Okita K, Ichisaka T, Yamanaka S. Hypoxia enhances the generation of induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:237–241. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Shi Y, Do JT, Desponts C, Hahm HS, Schöler HR, Ding S. A combined chemical and genetic approach for the generation of induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:525–528. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ichida JK, Blanchard J, Lam K, Son EY, Chung JE, Egli D, Loh KM, Carter AC, Di Giorgio FP, Koszka K, et al. A small-molecule inhibitor of tgf-Beta signaling replaces sox2 in reprogramming by inducing nanog. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:491–503. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lee CH, Kim JH, Lee HJ, Jeon K, Lim H, Choi Hy, Lee ER, Park SH, Park JY, Hong S, et al. The generation of iPS cells using non-viral magnetic nanoparticle based transfection. Biomaterials. 2011;32:6683–6691. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.05.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Jung DW, Kim WH, Williams DR. Reprogram or reboot: small molecule approaches for the production of induced pluripotent stem cells and direct cell reprogramming. ACS Chem Biol. 2014;9:80–95. doi: 10.1021/cb400754f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Woltjen K, Hämäläinen R, Kibschull M, Mileikovsky M, Nagy A. Transgene-free production of pluripotent stem cells using piggyBac transposons. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;767:87–103. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-201-4_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Grabundzija I, Wang J, Sebe A, Erdei Z, Kajdi R, Devaraj A, Steinemann D, Szuhai K, Stein U, Cantz T, et al. Sleeping Beauty transposon-based system for cellular reprogramming and targeted gene insertion in induced pluripotent stem cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:1829–1847. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Davis RP, Nemes C, Varga E, Freund C, Kosmidis G, Gkatzis K, de Jong D, Szuhai K, Dinnyés A, Mummery CL. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells from human foetal fibroblasts using the Sleeping Beauty transposon gene delivery system. Differentiation. 2013;86:30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.diff.2013.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Mo X, Li N, Wu S. Generation and characterization of bat-induced pluripotent stem cells. Theriogenology. 2014;82:283–293. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2014.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Tsukiyama T, Kato-Itoh M, Nakauchi H, Ohinata Y. A comprehensive system for generation and evaluation of induced pluripotent stem cells using piggyBac transposition. PLoS One. 2014;9:e92973. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Talluri TR, Kumar D, Glage S, Garrels W, Ivics Z, Debowski K, Behr R, Kues WA. Non-viral reprogramming of fibroblasts into induced pluripotent stem cells by Sleeping Beauty and piggyBac transposons. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;450:581–587. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Szymczak AL, Workman CJ, Wang Y, Vignali KM, Dilioglou S, Vanin EF, Vignali DA. Correction of multi-gene deficiency in vivo using a single ‘self-cleaving’ 2A peptide-based retroviral vector. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:589–594. doi: 10.1038/nbt957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Yusa K, Rad R, Takeda J, Bradley A. Generation of transgene-free induced pluripotent mouse stem cells by the piggyBac transposon. Nat Methods. 2009;6:363–369. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kaji K, Norrby K, Paca A, Mileikovsky M, Mohseni P, Woltjen K. Virus-free induction of pluripotency and subsequent excision of reprogramming factors. Nature. 2009;458:771–775. doi: 10.1038/nature07864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Zhou H, Wu S, Joo JY, Zhu S, Han DW, Lin T, Trauger S, Bien G, Yao S, Zhu Y, et al. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells using recombinant proteins. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:381–384. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Plews JR, Li J, Jones M, Moore HD, Mason C, Andrews PW, Na J. Activation of pluripotency genes in human fibroblast cells by a novel mRNA based approach. PLoS One. 2010;5:e14397. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Yoshioka N, Gros E, Li HR, Kumar S, Deacon DC, Maron C, Muotri AR, Chi NC, Fu XD, Yu BD, et al. Efficient generation of human iPSCs by a synthetic self-replicative RNA. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;13:246–254. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Card DA, Hebbar PB, Li L, Trotter KW, Komatsu Y, Mishina Y, Archer TK. Oct4/Sox2-regulated miR-302 targets cyclin D1 in human embryonic stem cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:6426–6438. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00359-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Suh MR, Lee Y, Kim JY, Kim SK, Moon SH, Lee JY, Cha KY, Chung HM, Yoon HS, Moon SY, et al. Human embryonic stem cells express a unique set of microRNAs. Dev Biol. 2004;270:488–498. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Lin SL, Chang DC, Chang-Lin S, Lin CH, Wu DT, Chen DT, Ying SY. Mir-302 reprograms human skin cancer cells into a pluripotent ES-cell-like state. RNA. 2008;14:2115–2124. doi: 10.1261/rna.1162708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Anokye-Danso F, Trivedi CM, Juhr D, Gupta M, Cui Z, Tian Y, Zhang Y, Yang W, Gruber PJ, Epstein JA, et al. Highly efficient miRNA-mediated reprogramming of mouse and human somatic cells to pluripotency. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:376–388. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Miyoshi N, Ishii H, Nagano H, Haraguchi N, Dewi DL, Kano Y, Nishikawa S, Tanemura M, Mimori K, Tanaka F, et al. Reprogramming of mouse and human cells to pluripotency using mature microRNAs. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:633–638. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Gonçalves NN, Ambrósio CE, Piedrahita JA. Stem cells and regenerative medicine in domestic and companion animals: a multispecies perspective. Reprod Domest Anim. 2014;49 Suppl 4:2–10. doi: 10.1111/rda.12392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Worringer KA, Rand TA, Hayashi Y, Sami S, Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Narita M, Srivastava D, Yamanaka S. The let-7/LIN-41 pathway regulates reprogramming to human induced pluripotent stem cells by controlling expression of prodifferentiation genes. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;14:40–52. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Zhang Z, Xiang D, Heriyanto F, Gao Y, Qian Z, Wu WS. Dissecting the roles of miR-302/367 cluster in cellular reprogramming using TALE-based repressor and TALEN. Stem Cell Reports. 2013;1:218–225. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Ma K, Song G, An X, Fan A, Tan W, Tang B, Zhang X, Li Z. miRNAs promote generation of porcine-induced pluripotent stem cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2014;389:209–218. doi: 10.1007/s11010-013-1942-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Heng BC, Fussenegger M. Integration-free reprogramming of human somatic cells to induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) without viral vectors, recombinant DNA, and genetic modification. Methods Mol Biol. 2014;1151:75–94. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-0554-6_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Wang X, Dai J. Concise review: isoforms of OCT4 contribute to the confusing diversity in stem cell biology. Stem Cells. 2010;28:885–893. doi: 10.1002/stem.419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Chew JL, Loh YH, Zhang W, Chen X, Tam WL, Yeap LS, Li P, Ang YS, Lim B, Robson P, et al. Reciprocal transcriptional regulation of Pou5f1 and Sox2 via the Oct4/Sox2 complex in embryonic stem cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:6031–6046. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.14.6031-6046.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Masui S, Nakatake Y, Toyooka Y, Shimosato D, Yagi R, Takahashi K, Okochi H, Okuda A, Matoba R, Sharov AA, et al. Pluripotency governed by Sox2 via regulation of Oct3/4 expression in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:625–635. doi: 10.1038/ncb1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Chambers I, Colby D, Robertson M, Nichols J, Lee S, Tweedie S, Smith A. Functional expression cloning of Nanog, a pluripotency sustaining factor in embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2003;113:643–655. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00392-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Kim J, Chu J, Shen X, Wang J, Orkin SH. An extended transcriptional network for pluripotency of embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2008;132:1049–1061. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Niwa H, Ogawa K, Shimosato D, Adachi K. A parallel circuit of LIF signalling pathways maintains pluripotency of mouse ES cells. Nature. 2009;460:118–122. doi: 10.1038/nature08113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Li Y, McClintick J, Zhong L, Edenberg HJ, Yoder MC, Chan RJ. Murine embryonic stem cell differentiation is promoted by SOCS-3 and inhibited by the zinc finger transcription factor Klf4. Blood. 2005;105:635–637. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Nakagawa M, Takizawa N, Narita M, Ichisaka T, Yamanaka S. Promotion of direct reprogramming by transformation-deficient Myc. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:14152–14157. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009374107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Qiu C, Ma Y, Wang J, Peng S, Huang Y. Lin28-mediated post-transcriptional regulation of Oct4 expression in human embryonic stem cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:1240–1248. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Maekawa M, Yamaguchi K, Nakamura T, Shibukawa R, Kodanaka I, Ichisaka T, Kawamura Y, Mochizuki H, Goshima N, Yamanaka S. Direct reprogramming of somatic cells is promoted by maternal transcription factor Glis1. Nature. 2011;474:225–229. doi: 10.1038/nature10106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Rossello RA, Chen CC, Dai R, Howard JT, Hochschwender U, Jarvis ED. Mammalian genes induce partially reprogrammed pluripotent stem cells in non-mammalian vertebrate and invertebrate species. eLife. 2013;2:e00036. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Walia B, Satija N, Tripathi RP, Gangenahalli GU. Induced pluripotent stem cells: fundamentals and applications of the reprogramming process and its ramifications on regenerative medicine. Stem Cell Rev. 2012;8:100–115. doi: 10.1007/s12015-011-9279-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Wang P, Na J. Mechanism and methods to induce pluripotency. Protein Cell. 2011;2:792–799. doi: 10.1007/s13238-011-1107-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Raya A, Rodríguez-Pizà I, Guenechea G, Vassena R, Navarro S, Barrero MJ, Consiglio A, Castellà M, Río P, Sleep E, et al. Disease-corrected haematopoietic progenitors from Fanconi anaemia induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2009;460:53–59. doi: 10.1038/nature08129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Hanna J, Wernig M, Markoulaki S, Sun CW, Meissner A, Cassady JP, Beard C, Brambrink T, Wu LC, Townes TM, et al. Treatment of sickle cell anemia mouse model with iPS cells generated from autologous skin. Science. 2007;318:1920–1923. doi: 10.1126/science.1152092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Park IH, Arora N, Huo H, Maherali N, Ahfeldt T, Shimamura A, Lensch MW, Cowan C, Hochedlinger K, Daley GQ. Disease-specific induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell. 2008;134:877–886. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Soldner F, Hockemeyer D, Beard C, Gao Q, Bell GW, Cook EG, Hargus G, Blak A, Cooper O, Mitalipova M, et al. Parkinson’s disease patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells free of viral reprogramming factors. Cell. 2009;136:964–977. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Cebrian-Serrano A, Stout T, Dinnyes A. Veterinary applications of induced pluripotent stem cells: regenerative medicine and models for disease? Vet J. 2013;198:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2013.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Kues WA, Niemann H. Advances in farm animal transgenesis. Prev Vet Med. 2011;102:146–156. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2011.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Ben-Nun IF, Montague SC, Houck ML, Tran HT, Garitaonandia I, Leonardo TR, Wang YC, Charter SJ, Laurent LC, Ryder OA, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cells from highly endangered species. Nat Methods. 2011;8:829–831. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Verma R, Holland MK, Temple-Smith P, Verma PJ. Inducing pluripotency in somatic cells from the snow leopard (Panthera uncia), an endangered felid. Theriogenology. 2012;77:220–228, 228.e1-2. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2011.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Panula S, Medrano JV, Kee K, Bergström R, Nguyen HN, Byers B, Wilson KD, Wu JC, Simon C, Hovatta O, et al. Human germ cell differentiation from fetal- and adult-derived induced pluripotent stem cells. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:752–762. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Zhu Y, Hu HL, Li P, Yang S, Zhang W, Ding H, Tian RH, Ning Y, Zhang LL, Guo XZ, et al. Generation of male germ cells from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPS cells): an in vitro and in vivo study. Asian J Androl. 2012;14:574–579. doi: 10.1038/aja.2012.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Gore A, Li Z, Fung HL, Young JE, Agarwal S, Antosiewicz-Bourget J, Canto I, Giorgetti A, Israel MA, Kiskinis E, et al. Somatic coding mutations in human induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2011;471:63–67. doi: 10.1038/nature09805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Hussein SM, Batada NN, Vuoristo S, Ching RW, Autio R, Närvä E, Ng S, Sourour M, Hämäläinen R, Olsson C, et al. Copy number variation and selection during reprogramming to pluripotency. Nature. 2011;471:58–62. doi: 10.1038/nature09871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Lister R, Pelizzola M, Kida YS, Hawkins RD, Nery JR, Hon G, Antosiewicz-Bourget J, O’Malley R, Castanon R, Klugman S, et al. Hotspots of aberrant epigenomic reprogramming in human induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2011;471:68–73. doi: 10.1038/nature09798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Miura K, Okada Y, Aoi T, Okada A, Takahashi K, Okita K, Nakagawa M, Koyanagi M, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, et al. Variation in the safety of induced pluripotent stem cell lines. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:743–745. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Gün G, Kues WA. Current progress of genetically engineered pig models for biomedical research. BioResearch Open Access. 2014;3:255–264. doi: 10.1089/biores.2014.0039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Bassols A, Costa C, Eckersall PD, Osada J, Sabrià J, Tibau J. The pig as an animal model for human pathologies: A proteomics perspective. Proteomics Clin Appl. 2014;8:715–731. doi: 10.1002/prca.201300099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Kurome M, Geistlinger L, Kessler B, Zakhartchenko V, Klymiuk N, Wuensch A, Richter A, Baehr A, Kraehe K, Burkhardt K, et al. Factors influencing the efficiency of generating genetically engineered pigs by nuclear transfer: multi-factorial analysis of a large data set. BMC Biotechnol. 2013;13:43. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-13-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Duranthon V, Beaujean N, Brunner M, Odening KE, Santos AN, Kacskovics I, Hiripi L, Weinstein EJ, Bosze Z. On the emerging role of rabbit as human disease model and the instrumental role of novel transgenic tools. Transgenic Res. 2012;21:699–713. doi: 10.1007/s11248-012-9599-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]