Abstract

Loss of polarity correlates with progression of epithelial cancers, but how plasma membrane misorganization drives oncogenic transcriptional events remains unclear. The polarity regulators of the Drosophila Scribble (Scrib) module are potent tumor suppressors and provide a model for mechanistic investigation. RNA profiling of Scrib mutant tumors reveals multiple signatures of neoplasia, including altered metabolism and dedifferentiation. Prominent among these is upregulation of cytokine-like Unpaired (Upd) ligands, which drive tumor overgrowth. We identified a polarity-responsive enhancer in upd3, which is activated in a coincident manner by both JNK-dependent Fos and aPKC-mediated Yki transcription. This enhancer, and Scrib mutant overgrowth in general, are also sensitive to activity of the Polycomb Group (PcG), suggesting that PcG attenuation upon polarity loss potentiates select targets for activation by JNK and Yki. Our results link epithelial organization to signaling and epigenetic regulators that control tissue repair programs, and provide insight into why epithelial polarity is tumor-suppressive.

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7554/eLife.03189.001

Research organism: D. melanogaster

eLife digest

The cavities and organs within our body are lined with epithelial cells, which connect to each other to form continuous barriers. These cells have a highly polarized structure in which different components are found at the top and bottom of cells. In the fruit fly and most other animals, three genes known as the Scribble module control the polarity of epithelial cells. If these genes are faulty, the cells lose their polarity, break the epithelial barrier, and grow rapidly to form a tumor. Most malignant tumors that form from epithelial cells have lost normal cell polarity, so understanding how the organization and growth of epithelial cells are linked is a critical question.

It is not clear how the loss of cell polarity can drive tumor formation. Here, Bunker et al. used a technique called RNA sequencing to study the expression of genes in tumor cells that have mutations in the Scribble module. Hundreds of genes in the tumor cells had different levels of expression from the levels seen in normal fly cells. One of these is a gene called upd3, which was expressed much more highly in tumor cells than in normal cells. This gene activates a signaling pathway—called the JAK/STAT pathway—that promotes cell growth and division in many animals. Bunker et al. found that experimentally lowering the activity of the JAK/STAT pathway reduced the growth of the tumor cells that had lost normal polarity.

Further experiments show that disrupting the layer of epithelial cells activates two other signaling pathways that work together to switch on the upd3 gene when cell polarity is lost. Proteins belonging to the Polycomb Group also control the expression of upd3 and other genes involved in cell growth by altering how genetic material is packaged in cells.

The similarities between this response and the response to tissue damage suggest that the loss of polarity drives tumor formation through an unstoppable wound-healing reaction. Therefore, Bunker et al.'s findings link the formation of epithelial tumors to the signaling pathways that control the repair of damaged tissues.

Introduction

The diagnosis of carcinomas–malignant tumors of epithelial origin—has long involved evaluating tissue architecture. Pronounced disorganization of biopsied epithelia is well-established to correlate with tumor malignancy and lethality. However, whether there exists a causative relationship between epithelial organization and tumor progression, as well as what the underlying mechanism might be, has been mysterious. Recent years have shed important light on the former question, identifying contexts where altered activity of proteins that regulate epithelial cell polarity can promote oncogenic phenotypes. For instance, the apical determinant atypical protein kinase C (aPKC) is amplified and over-expressed in multiple cancers (Huang and Muthuswamy, 2010; Parker et al., 2014), while basolateral regulators are altered in several tumor types and degraded by viral oncoproteins (Huang and Muthuswamy, 2010; Elsum et al., 2012); cancer stem cell activity may also be promoted by transition from an epithelial state (Martin-Belmonte and Perez-Moreno, 2011; Scheel and Weinberg, 2012). Mouse models continue to support key roles for polarity regulators in cancer progression (Pearson et al., 2011; Muthuswamy and Xue, 2012; Elsum et al., 2014; Feigin et al., 2014), but the mechanisms linking epithelial organization to tissue homeostasis, as well as the cellular targets that promote oncogenic growth upon polarity loss, remain unclear.

Early evidence for causative links emerged from Drosophila, where mutations in single polarity-regulating genes can induce dramatic tumorous growths. These polarity regulators–scribble (scrib), discs-large (dlg), and lethal giant larvae (lgl)- cooperatively distinguish the basolateral domain from the apical by antagonizing aPKC activity (St Johnston and Ahringer, 2010; Tepass, 2012). This conserved ‘Scrib module’ functions in both vertebrates and invertebrates, not only in epithelia but also other polarized cell types. Conservation of these and other core polarity regulators allows Drosophila to be used as a model to study the coupling between epithelial architecture and growth control.

When Scrib module function is lost from fly epithelia, mutant cells round up and become multilayered. In the imaginal discs, epithelial organs which normally have a precise intrinsic size-control mechanism, mutant tissue continuously proliferates to more than five times the WT cell number before it kills the animal. Small portions of the tumorous mass, when transplanted into adults, continue to grow uncontrollably and kill the host; such allografts can be repeated indefinitely. This disorganized, lethal and transplantable growth has been termed ‘neoplastic’, and includes several additional features (Gateff and Schneiderman, 1969; Bilder, 2004). Neoplastic fly tissue is prone to dissemination and degrades basement membrane; in cooperation with oncogenic Ras it can migrate away from its primary site and invade other organs (Pagliarini and Xu, 2003). It is compromised in its differentiation potential, and cannot form adult structures (Gateff and Schneiderman, 1969). It can be recognized by the host innate immune system, whose cellular activities impede its growth (Pastor-Pareja et al., 2008; Cordero et al., 2010). Finally, it produces long-range signals that induce detrimental responses in fly hosts, including cachexia-like tissue wasting (Figueroa-Clarevega and Bilder, 2015). This suite of phenotypes, which echo those found in mammalian malignancies, suggest that elucidating mechanisms linking epithelial organization to tumor suppression in flies may provide novel insight into human cancer as well.

What are the genes that induce the multiple aspects of the neoplastic phenotype, and how does loss of a single polarity regulator at the plasma membrane lead to their nuclear misregulation? Here we define the global transcriptional changes associated with tumorigenic epithelial disorganization. By focusing on a single polarity-regulated enhancer of a gene involved in overgrowth, we then untangle signaling, transcription factor, and epigenetic activities that mediate activation upon polarity loss. Our results suggest that epithelia monitor their integrity via a coincidence detection mechanism, and respond to its loss by activating a damage-responsive gene expression program that cannot be turned off in mispolarized tumors.

Results

Polarity disruption drives oncogenic transcriptional changes

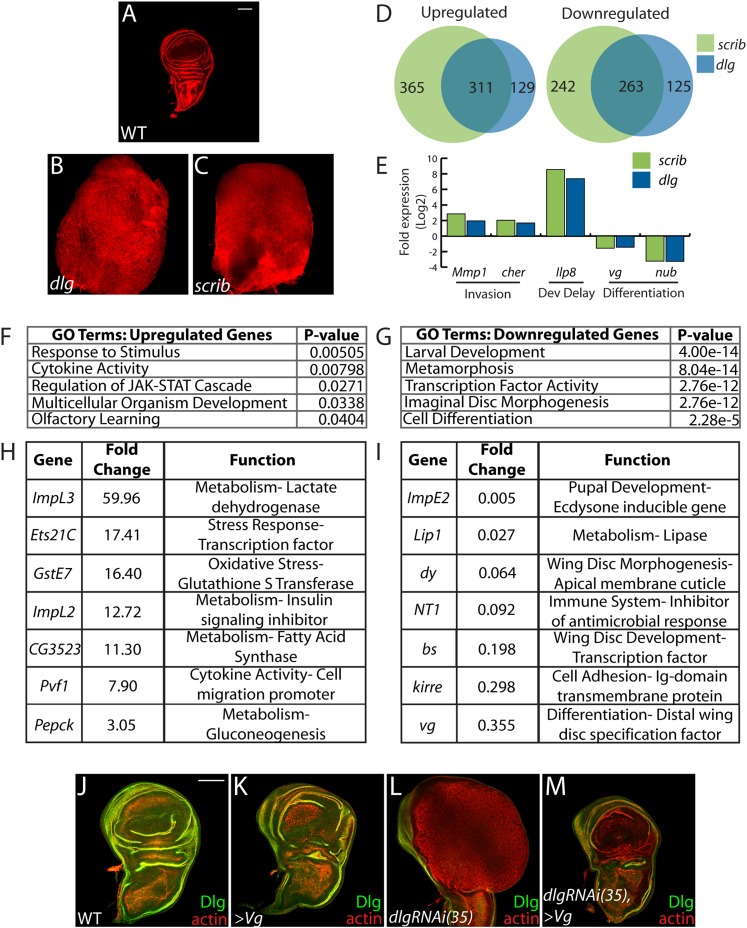

The many malignant-like phenotypes observed upon loss of a single polarity regulator must be driven by altered gene expression. To identify such genes, we carried out RNA-Seq analysis of WT and mutant wing imaginal discs. We focused on changes common to neoplasm by sequencing cDNA libraries generated from both scrib and dlg tumors, which phenocopy each other (Figure 1A–C) (Bilder et al., 2000). Analysis revealed 574 genes misregulated at least twofold in both mutant tissues (FDR <5%), with 311 and 263 up- and downregulated respectively (Figure 1D and Suplementary files 1–2). Differentially expressed genes include several previously identified neoplastic effectors, such as the pro-invasion factors Matrix metalloprotease 1 (Mmp1) and cheerio (cher) as well as the pupation regulator insulin-like peptide 8 (Ilp8) (Uhlirova and Bohmann, 2006; Colombani et al., 2012; Garelli et al., 2012; Külshammer and Uhlirova, 2013) (Figure 1E). qRT-PCR analysis of these and other genes shows close agreement with RNA-Seq data (R2 = 0.8844). The transcriptome dataset therefore accurately captures the expression profile of neoplastic tissues, and contains genes that promote tumorigenesis upon polarity loss.

Figure 1. Transcriptome analysis of neoplastic tumors.

(A–C) F-actin staining reveals dramatic overgrowth and architecture defects of neoplastic dlg and scrib wing discs relative to WT. (D) Overlap of genes upregulated (left) or downregulated (right) in scrib and dlg tissues. (E) Genes previously implicated in neoplastic characteristics are differentially expressed. (F and G) Functional categories enriched in the upregulated and downregulated genes include markers of stress response and JAK/STAT pathway activation, and de-differentiation respectively. Selected overexpressed (H) and underexpressed (I) genes are shown. (J–M) Overexpression of Vg suppresses dlgRNAi-driven overgrowth and architecture defects. Dlg staining (green) demonstrates survival of Dlg-depleted wing cells. Scale bars: 100 μm.

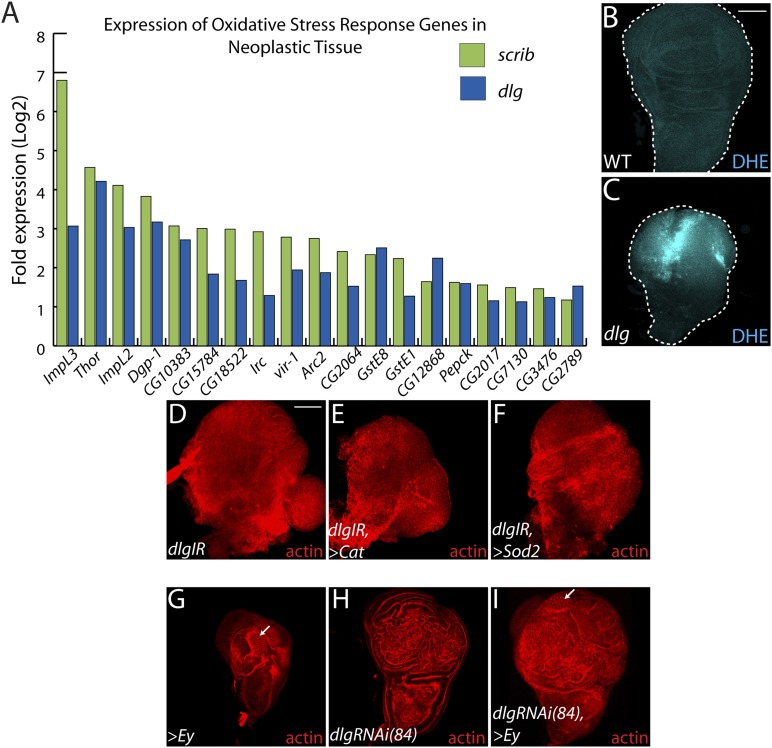

Figure 1—figure supplement 1. Decreasing oxidative stress or reexpressing eyelesss does not suppress neoplasia.

Amongst upregulated genes, Gene Ontology (GO) highlights factors involved in Response to Stimulus (Figure 1F,H). Several in this category are immune-related factors, and may be due to the recruitment of hemocytes to neoplastic tumors (Lebestky et al., 2000; Pastor-Pareja et al., 2008; Cordero et al., 2010). Others, including Glutathione S transferase E1 (GstE1) and the chaperone CG7130, are regulated by oxidative stress, and overall 19 polarity-sensitive targets are also elevated in hyperoxic conditions (Figure 1—figure supplement 1A) (Landis et al., 2004). Dihydroethidium (DHE), a fluorescent probe for superoxide anions, readily demonstrated elevation upon depletion of dlg (Figure 1—figure supplement 1B–C). Co-overexpression of Catalase, Superoxide dismutase 2, or rat Glutathione Peroxidase 1, which suppress other Drosophila ROS dependent phenotypes (Owusu-Ansah and Banerjee, 2009; Ohsawa et al., 2012; Lim et al., 2014) failed to alter the neoplastic phenotype induced by dlg knockdown (Figure 1—figure supplement 1D–F), although we were unable to detect a consistent reduction of DHE in these contexts. Several metabolic regulators are also misexpressed in polarity-deficient tissues, including Drosophila Lactate Dehydrogenase (ImpL3), which contributes to a Warburg-like metabolic shift in human tumors (Cairns et al., 2011); however, ImpL3 knockdown also did not obviously alter neoplastic growth (data not shown).

Primary GO categories among downregulated genes likely reflect the failure of neoplastic tumors to differentiate (Figure 1E,G,I). We investigated the functional role by ectopically expressing fate-specifying transcription factors in dlg-depleted tissue. Strikingly, co-expression of vestigial (vg), a distal wing pouch selector that is downregulated in mutant discs, suppressed overgrowth and architecture defects (Figure 1J–M). Though vg overexpression eliminates polarity-deficient clones through apoptosis (Khan et al., 2013), we recovered an intact wing pouch consisting of dlgRNAi/vg co-expressing cells (Figure 1M). We also tested ectopic expression of an eye-specifying transcription factor in wing and eye tissue. eyeless was incapable of suppressing dlg knockdown in either context, but was also incapable of inducing broad photoreceptor differentiation in WT or dlg-depleted tissue (Figure 1—figure supplement 1G–I, data not shown). Together, these data suggest that restoring expression of differentiation-promoting transcription factors can, in some contexts, block neoplastic transformation.

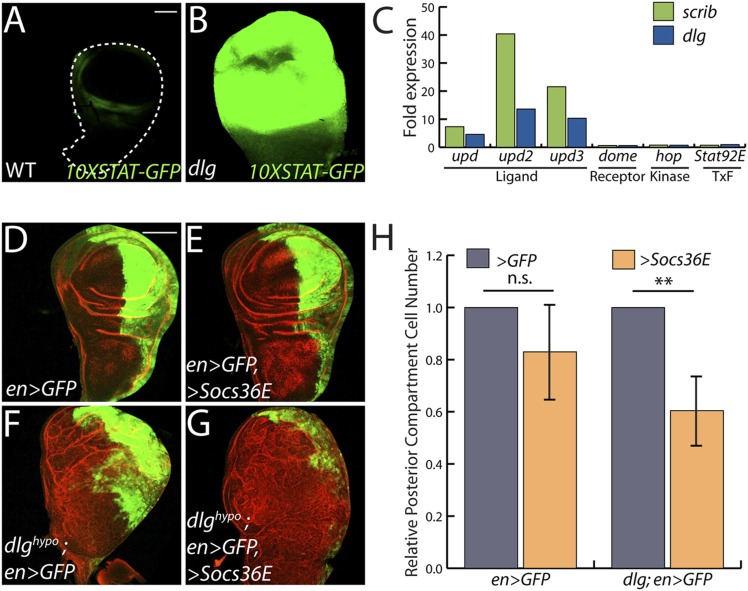

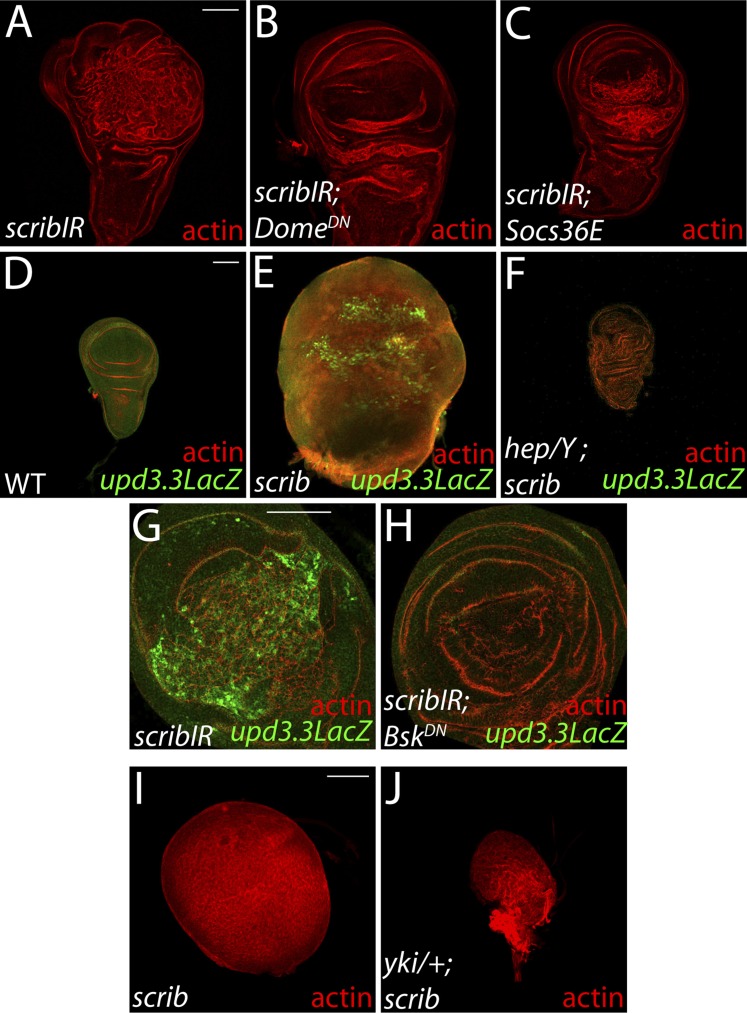

JAK-STAT ligand transcription promotes neoplastic overgrowth

The only cell signaling pathway among the top GO categories is the JAK/STAT cascade. Upregulated genes include STAT targets such as chinmo and Socs36E, and a JAK/STAT activity reporter is strongly expressed in dlg and scrib discs (Figure 2A–B) (Wu et al., 2010). Remarkably, each of the three unpaired (upd) genes, which encode the ligands for the JAK/STAT pathway, were transcriptionally elevated between ∼3- and ∼50-fold, while genes encoding other signal transduction components were unaltered (Figure 2C). To assess a functional role, we used engrailed-GAL4 to express Socs36E, a negative regulator of JAK/STAT intracellular signaling (Callus and Mathey-Prevot, 2002), in the posterior compartment of wing discs carrying a hypomorphic allele of dlg, and then counted cell numbers on a cell sorter. Strikingly, Socs36E decreased proliferation of dlghypo cells by 40%, while having no significant effect on growth or viability of WT discs (Figure 2D–H). Expression of Socs36E or a dominant-negative form of the JAK-STAT receptor Domeless (DomeDN) also suppressed the growth of scrib-depleted discs (Figure 4—figure supplement 3A–C). We therefore conclude that in imaginal discs, as in RasV12-expressing clones (Wu et al., 2010), the Scrib module regulates JAK-STAT ligand expression to suppress tissue overgrowth.

Figure 2. JAK/STAT activation drives overgrowth upon polarity loss.

(A and B) A JAK/STAT pathway reporter (green) is highly elevated throughout dlg as compared to WT discs, indicating strong pathway activation. (C) The ligand-encoding upd genes, but not other JAK/STAT pathway components, are transcriptionally upregulated in neoplastic tissues. (D–G) Reduction of JAK/STAT pathway activity via SOCS36E overexpression has no significant effect on WT growth, but suppresses overgrowth of dlghypo tissue. Actin (red) highlights cell outlines, while GFP (green) marks the engrailed-expressing domain. FACS-based quantification is shown in H (**p < 0.001). Scale bars: 100 μm.

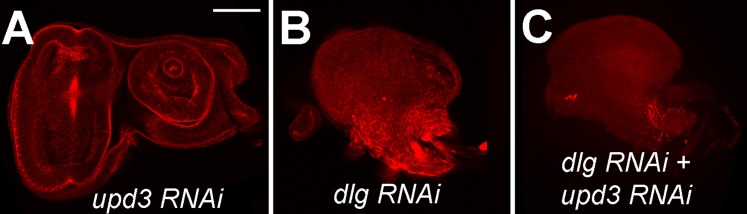

Figure 2—figure supplement 1. upd3 knockdown is not sufficient to prevent neoplastic tumors.

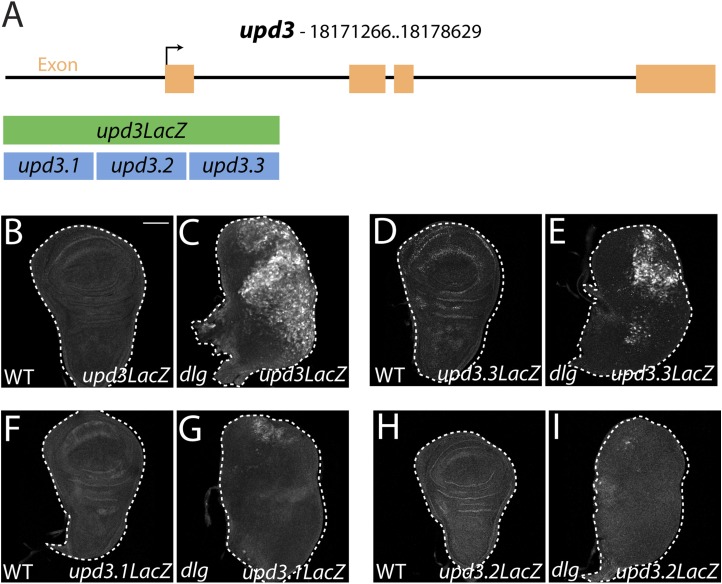

Isolation of a polarity-responsive enhancer in upd3

To elucidate links between polarity and transcriptional control of growth, we focused on a single mitogenic gene: upd3. We cloned 3 kilobases (kb) of genomic DNA surrounding the upd3 ATG into a lacZ reporter (‘upd3lacZ’) and found that this reporter was not expressed in WT discs. However, like the overlapping upd3 > GFP reporter, it was distinctly upregulated in neoplastic discs (Figure 3A–C) (Pastor-Pareja et al., 2008). We then identified a minimal polarity-responsive region within this enhancer, using fragments previously analyzed in the adult gut (Jiang et al., 2011). Although reporters including upd3.1LacZ, which is activated by perturbations in the gut epithelium, remain silent, a 1-kb element within the first intron (upd3.3LacZ) was expressed in a patchy manner throughout dlg discs (Figure 3D–I). Expression of upd3.3lacZ, like that of upd3lacZ, was in cells of the disc proper, not in the peripodium or hemocytes (Figure 3—figure supplement 1A–B); this patchy expression resembled that seen with several other upregulated neoplastic effectors, (Figure 4B′, Figure 3—figure supplement 1C–H). Upd3.3LacZ was similarly activated in scrib discs, demonstrating that this enhancer is generally responsive to disruption of epithelial polarity (Figure 4—figure supplement 3E) and identifying a polarity-sensitive cis-regulatory region.

Figure 3. Identification of a polarity-responsive enhancer in upd3.

(A) Schematic of upd3 reporter constructs in relation to the corresponding genomic region. (B and C) 3 kb upd3LacZ is not expressed in WT, but is upregulated in dlg discs. (D and E) upd3.3LacZ sub-fragment is also silent in WT, but is upregulated in dlg like upd3LacZ. (F–I) Other sub-fragments are not significantly expressed in either WT or dlg. Scale bar: 100 μm.

Figure 3—figure supplement 1. Imaginal expression of polarity-responsive target genes in neoplasia.

Figure 3—figure supplement 2. Conserved AP-1 and Sd binding sites in genes upregulated in neoplasia.

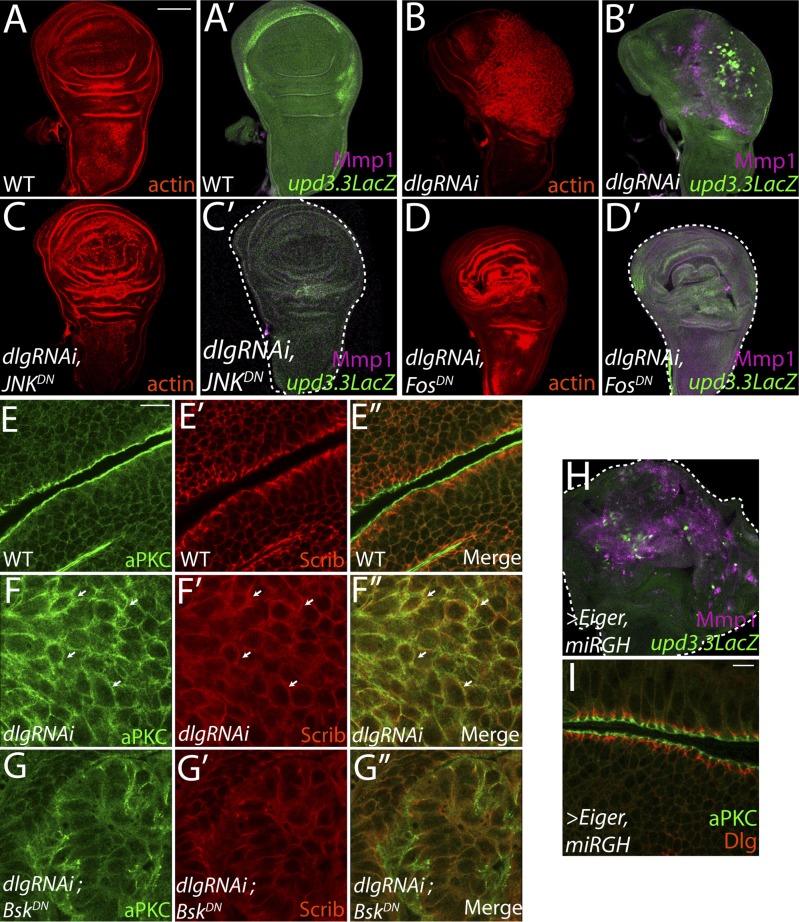

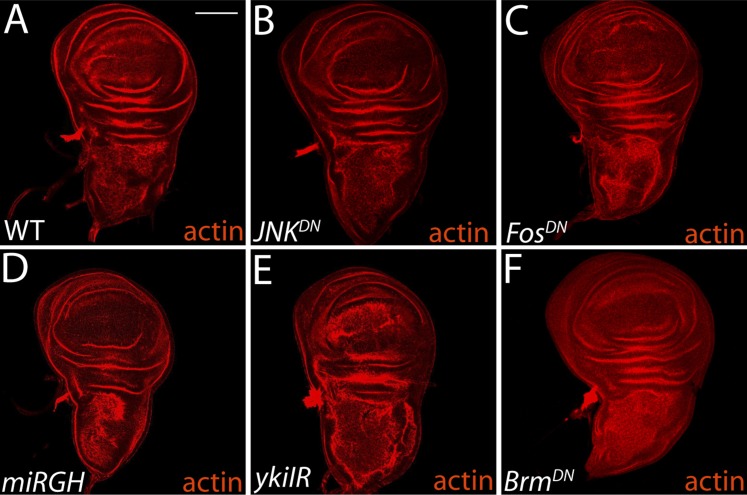

Figure 4. JNK-Dependent transcription is necessary for overgrowth and upd3.3 activation upon polarity loss.

WT wing discs (A) do not express either the JNK target Mmp1 or upd3.3LacZ (A′). Expression of dlgRNAi promotes overgrowth and disorganization (B), as well as Mmp1 and upd3.3LacZ upregulation (B′). Inhibiting AP-1 transcription with either JNKDN or FosDN restores normal disc size and architecture (C and D), and abrogates Mmp1 and upd3.3LacZ expression (C′ and D′). WT discs segregate apical aPKC and basolateral Scrib (E). dlgRNAi expression leads to apical domain expansion and co-localization of aPKC and Scrib (F, arrowheads). Co-expressing JNKDN and dlgRNAi restores the separation of aPKC and Scrib (G). Activation of JNK is sufficient, when apoptosis is blocked with miRGH, to drive upd3.3LacZ, Mmp1 and overgrowth but not to alter polarity (H and I). Scale bars: A–D, H: 100 μm, E–G, I: 10 μm.

Figure 4—figure supplement 1. Inhibitor constructs do not significantly affect WT tissue growth and viability.

Figure 4—figure supplement 2. Quantification of upd3.3LacZ staining.

Figure 4—figure supplement 3. Neoplasia induced by scrib loss is also dependent on JAK-STAT, JNK, and Yki pathway activity.

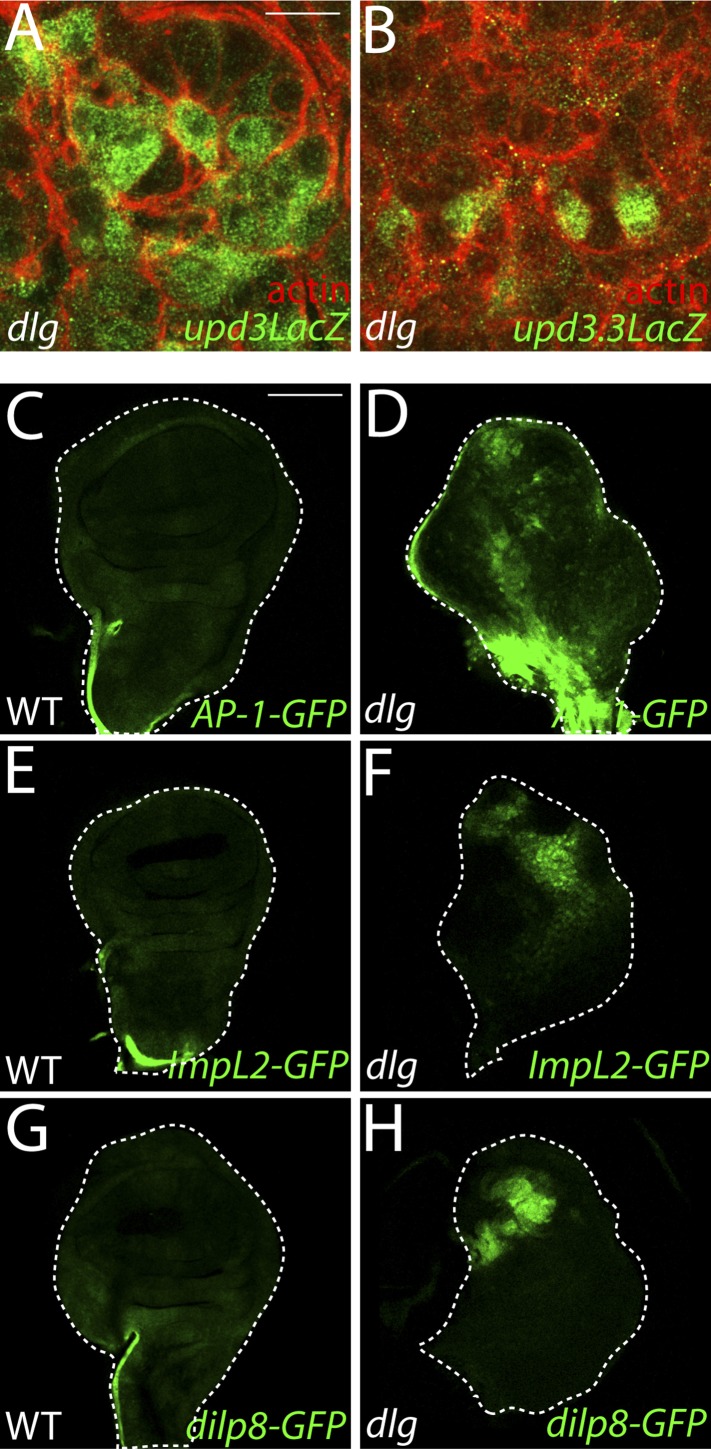

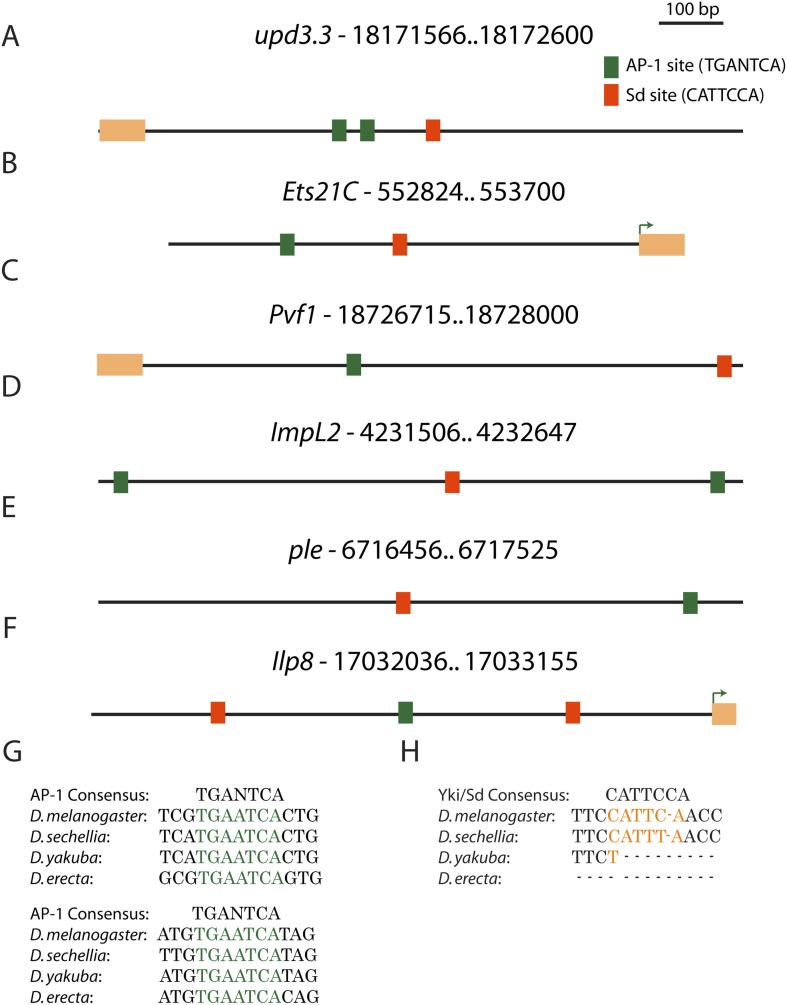

JNK-mediated transcription drives upd3.3 expression upon polarity loss

We next sought to identify molecular pathways linking epithelial polarity to upd3 expression. Motif scanning of the upd3.3 enhancer detected two evolutionarily-conserved binding sites for AP-1, the Jun kinase (JNK) pathway transcription factor (Figure 3—figure supplement 2A,G). We tested whether JNK signaling is required for upd3.3LacZ activation. Expression of a dominant-negative form of Drosophila JNK (Flybase: Basket), (JNKDN) has been shown to block neoplastic overgrowth, as well as polarity and architecture defects (Figure 4A–C,E–G; Figure 4—figure supplement 1A–B) (Robinson and Moberg, 2011; Sun and Irvine, 2011). Notably, JNKDN also completely abrogated dlgRNAi-induced upd3.3LacZ expression (Figure 4B′,C′; Figure 4—figure supplement 2A), as well as that induced by scribRNAi (Figure 4—figure supplement 3G–H). Mutation of the JNK kinase, hemipterous (hep) also prevented upd3.3LacZ levels in scrib tissue (Figure 4—figure supplement 3D–F), confirming that canonical JNK signaling acts downstream of polarity disruption to regulate upd3.

The mechanism by which JNK promotes neoplasia is unclear. Phosphorylation of Ajuba LIM protein (Jub) has been proposed to be key (Sun and Irvine, 2013); however, the presence of AP-1 binding sites within upd3.3 suggests a direct transcription-mediated mechanism. To test the latter mechanism, we assayed discs co-expressing dlgRNAi and fosDN, which prevents activity of the AP-1 transcription factor (Ciapponi et al., 2001). Strikingly, fosDN fully phenocopied the effects of JNKDN: it prevented both upd3.3LacZ expression and dlgRNAi-mediated neoplasia (Figure 4D; Figure 4—figure supplement 1C; Figure 4—figure supplement 2A). Taken together, these experiments demonstrate that maintenance of epithelial polarity prevents transcription of oncogenic JNK-dependent target genes.

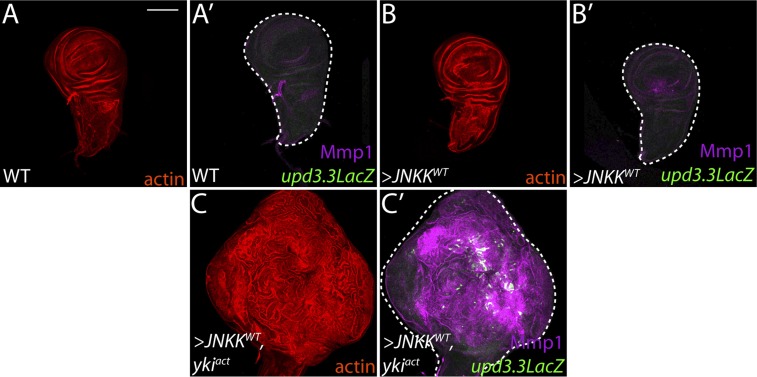

Given that elevated JNK signaling is necessary for upd3.3LacZ expression and neoplastic overgrowth, is it sufficient? Ectopic JNK activity in WT tissue leads to apoptosis (Igaki et al., 2002), so we co-expressed the JNK-activating ligand Eiger with a microRNA targeting the pro-apoptotic genes reaper, grim, and head involution defective (miRGH) to block both cell death and caspase activation (Siegrist et al., 2010). In this context, JNK activation alone induced upd3.3LacZ (Figure 4H; Figure 4—figure supplement 1D; Figure 4—figure supplement 2C) and increased tissue size (Pérez-Garijo et al., 2009). However, upd3.3LacZ induction was low compared to the canonical JNK target Mmp1, while dlg knockdown activated both comparably (Figure 4B′,H). Further, apical and basolateral proteins remained properly localized, indicating that JNK activation alone does not disrupt polarity (Figure 4I) (Sun and Irvine, 2011). Therefore, JNK signaling is sufficient for partial upd3.3 activation and overgrowth, but it is unable to induce full neoplasia.

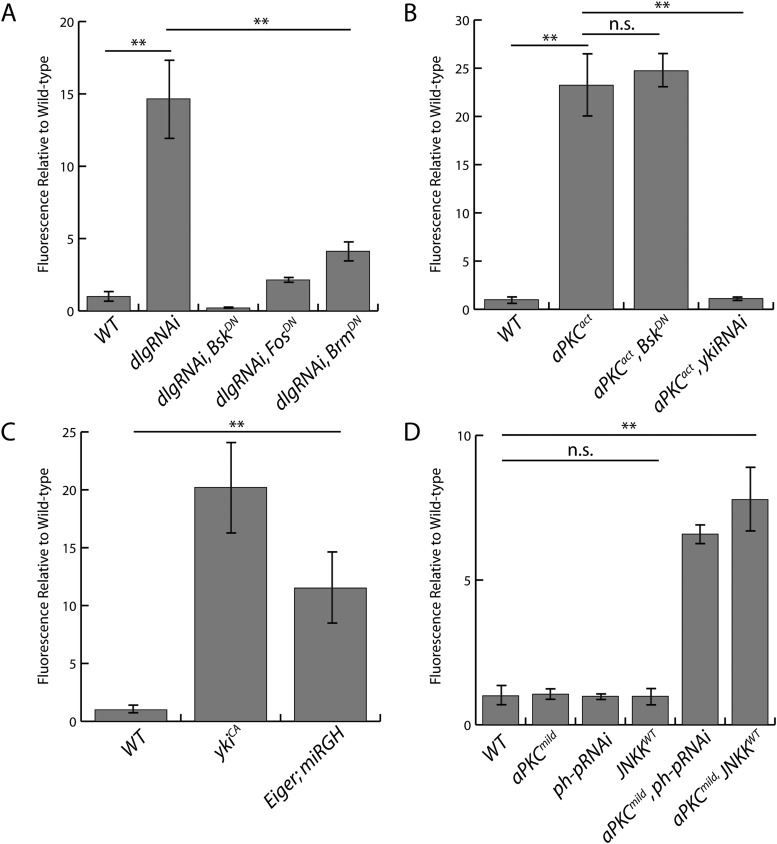

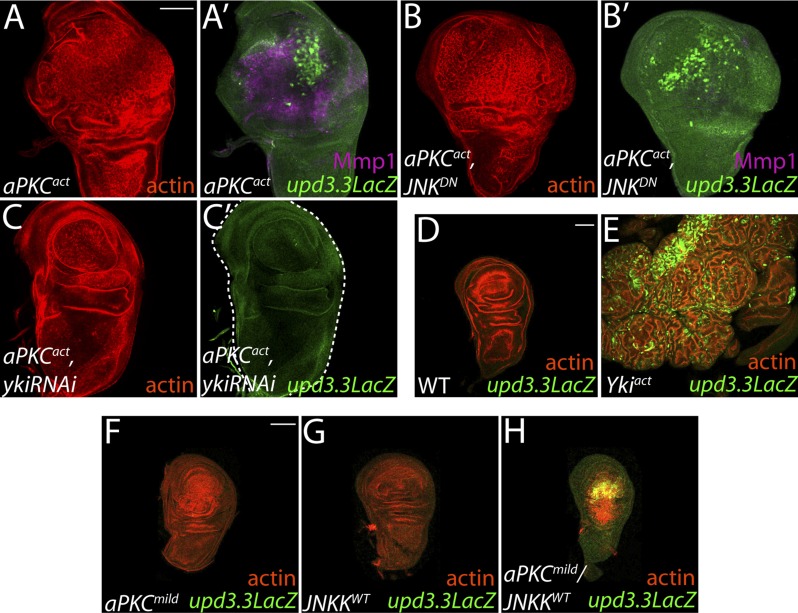

aPKC can regulate polarity-responsive transcription, independently of JNK

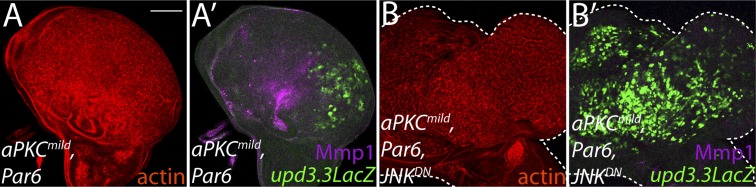

The inability of JNK activation to fully recapitulate dlg loss suggests that polarity regulators modulate additional factors to prevent upd3.3 transcription and neoplasm. One candidate is aPKC, which is strongly mislocalized upon loss of Scrib module function but not JNK activation (Figure 4F,I) (Bilder and Perrimon, 2000). We expressed a constitutively active form (aPKCact) that can drive neoplasia and found that it was sufficient to potently trigger upd3.3LacZ transcription (Figure 5A; Figure 4—figure supplement 2B). aPKCact can also activate JNK targets (Figure 5A′), raising the possibility that aPKC regulates upd3 through JNK. However, inhibiting JNK did not prevent aPKCact-mediated upd3.3LacZ activation or overgrowth, while it was effective at preventing expression of Mmp1 (Figure 5B; Figure 4—figure supplement 2B). Similar results were seen when membrane-bound WT aPKC (aPKCmild) was co-expressed with its partner Par-6, demonstrating that the results are not transgene-specific (Figure 5—figure supplement 1) and thus showing that aPKC is capable of stimulating tumorigenic transcription independently of JNK.

Figure 5. aPKC activity drives upd3.3LacZ activation in a yki-dependent manner.

(A) Expression of constitutively active aPKC (aPKCact) induces upd3.3LacZ and Mmp1 upregulation and neoplasia. (B) Expressing JNKDN suppresses Mmp1, but does not prevent aPKCact-mediated upd3.3LacZ activation or overgrowth. (C) Knockdown of yki blocks upd3.3LacZ and overgrowth upon ectopic aPKC activity, while constitutively active Yki drives upd3.3LacZ expression and tissue overgrowth relative to WT (D and E). Expression of a mildly-active form of aPKC (F) or JNK (G) alone cannot activate upd3.3, but together are sufficient for expression (H). Scale bars: 100 μm.

Figure 5—figure supplement 1. Ectopic aPKC activity drives upd3.3LacZ in a JNK-independent manner.

Figure 5—figure supplement 2. Scrib module and wts mutant expression profiles display limited overlap.

Figure 5—figure supplement 3. Co-activation of JNK and Yki are not sufficient to drive neoplasia.

aPKC activates polarity-responsive enhancers via Yki

To determine how aPKC activity at the cell cortex regulates transcriptional targets, we returned to our analysis of upd3.3 sequences. The enhancer contains a partially evolutionarily conserved binding site for Scalloped (Sd), a DNA-binding protein that recruits activated Yorkie (Yki) to target genes (Figure 3—figure supplement 2A,H) (Wu et al., 2008). Intriguingly, conserved Sd and AP-1 binding sites are also found together in ∼1 kb regulatory regions of other upregulated genes (Figure 3—figure supplement 2B–F). To determine if Yki acts downstream of aPKC, we assessed discs co-expressing aPKCact and a moderate strength RNAi against yki (ykiRNAi). While yki knockdown under these conditions had a minimal effect on WT growth, it completely abrogated ectopic aPKC-driven upd3.3LacZ upregulation (Figure 5C; Figure 4—figure supplement 1E; Figure 4—figure supplement 2B). Similarly, depletion of yki suppressed the overgrowth of scrib tissue (Figure 4—figure supplement 3I–J). We then analyzed discs overexpressing constitutively active Yki (Ykiact), which display massive overgrowth without affecting epithelial polarity (Dong et al., 2007; Oh and Irvine, 2008). Upd3.3LacZ expression was highly elevated in Ykiact-expressing tissues (Figure 5D–E; Figure 4—figure supplement 2C), indicating that Yki can also be sufficient to activate the polarity-responsive enhancer.

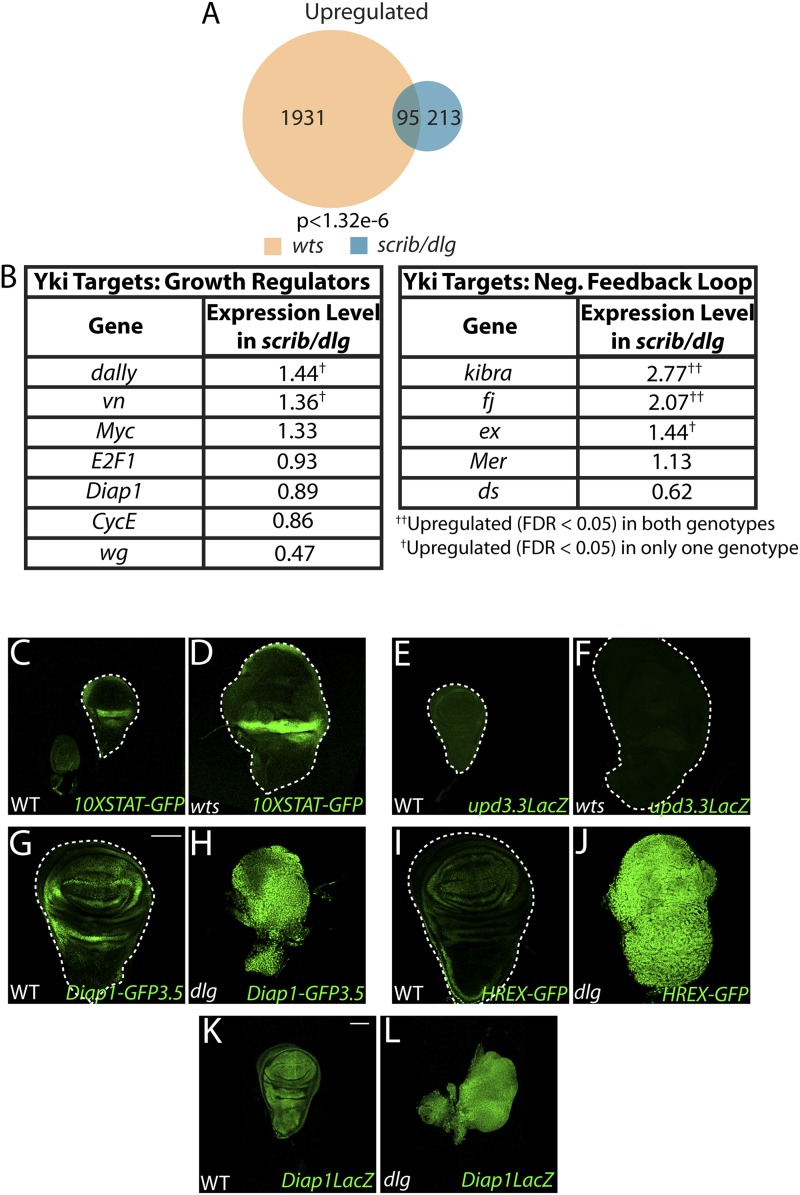

Coincident activation of upd3.3 by aPKC and JNK

Though hyperactivation of either JNK or Yki through overexpression of activated proteins can drive upd3.3 transcription, we found that only the highest levels of signaling could do so. For instance, neither upd3.3lacZ nor JAK/STAT signaling was active in hyperproliferating hippo (hpo) pathway mutant tumors (Figure 5—figure supplement 2C–F). Moreover, overexpression of either WT JNK kinase, or a membrane-targeted form of WT aPKC (aPKCmild), activated Mmp1 but does not cause substantial overgrowth; neither activates upd3.3lacZ (Figures 5F–G, 7J, Figure 5—figure supplement 3B). Since loss of polarity activates aPKC and JNK signaling in parallel, we tested whether the two pathways converge upon the enhancer. Strikingly, coexpression of JNK kinase and aPKCmild induced upd3.3lacZ upregulation (Figure 5H; Figure 4—figure supplement 2D), along with moderate overgrowth and polarity defects. These data support a model in which upd3.3 works as a ‘coincidence detector’, responding to simultaneous aPKC-mediated Yki activation and JNK-dependent Fos activation upon polarity loss.

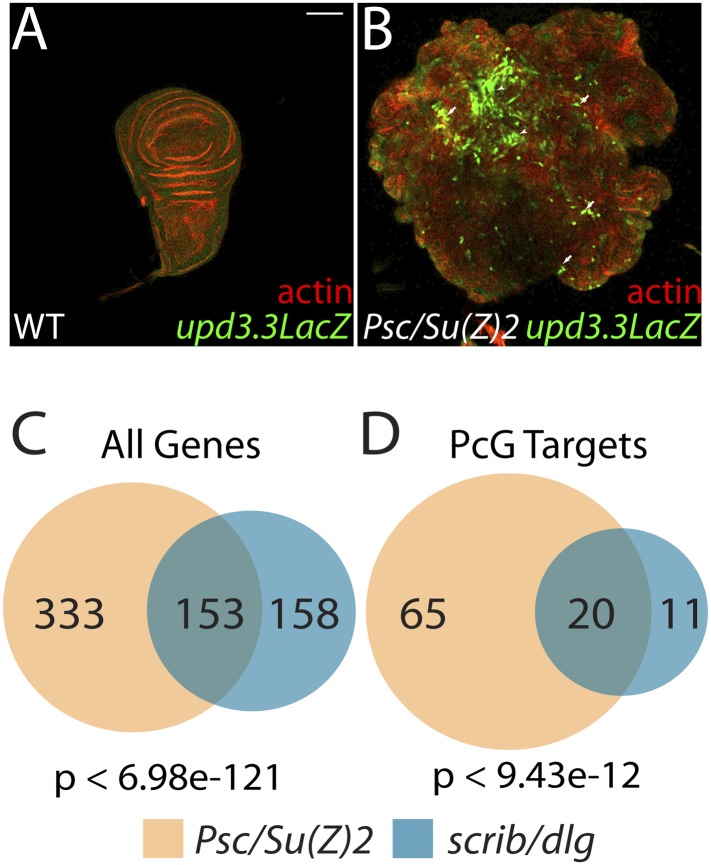

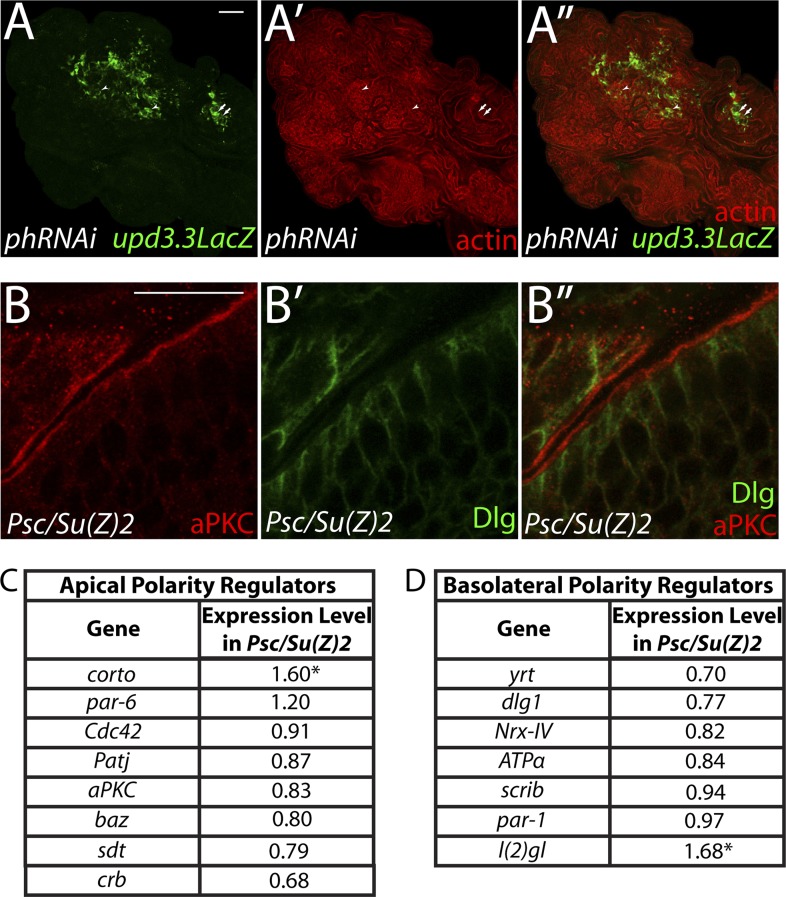

Epigenetic regulation of polarity-responsive targets

The above results suggest that transcription from enhancers like upd3.3 is kept in check when either JNK or Yki are activated at physiological rather than manipulated experimental levels. We therefore investigated additional regulators of upd transcription. Our previous work identified the upd genes as targets of direct repression by the Polycomb Group (PcG), and showed that mutations in PcG can result in tumorous growth (Classen et al., 2009). These data suggest the hypothesis that epithelial polarity also acts through PcG to influence mitogenic gene expression. To test this hypothesis, we first asked whether PcG regulates the polarity-responsive enhancer. Imaginal discs mutant for the paralogous PcGs Psc and Su(z)2 show dramatic overgrowth, in which apicobasal polarity is often intact (Classen et al., 2009). Strikingly, they also upregulated upd3.3LacZ, but not other upd3LacZ subfragments (Figure 6B and data not shown). This response is identical to that observed in polarity-deficient tissues.

Figure 6. The Scrib module and PcGs regulate common targets.

(A and B) Loss of the paralogous PcGs Psc and Su(z)2 leads to activation of upd3.3lacZ, along with dramatic overgrowth and architecture defects. Activation is observed in areas of epithelial (arrows) and disrupted (arrowheads) organization. Comparison of all genes (C) and direct PcG targets (D) upregulated in Psc/Su(z)2 and Scrib module mutant tissues reveals statistically significant overlaps. Scale bar: 100 μm.

Figure 6—figure supplement 1. PcG depletion does not cause widespread loss of polarity.

The common response of upd3 to polarity regulators and PcG could be a unique case, or alternatively could reflect a larger role for PcG in polarity-sensitive growth control. To determine if the Scrib module and PcGs co-regulate additional loci, we carried out a global transcriptional analysis of PcG mutant wing disc tumors (Supplementary file 3). Comparison of Scrib module and PcG mutant RNA-Seq datasets revealed that nearly half of the genes upregulated upon polarity loss are also upregulated in PcG mutant tissues, a highly significant enrichment (p < 6.98e-121, Figure 6C). This degree of similarity does not reflect a general overgrowth signature, as comparison with the transcriptome of warts tumors (Oh et al., 2013) gives a much less substantial overlap (Figure 5—figure supplement 2A). Further analysis of Scrib module transcriptomes revealed that nearly 25% of direct Pc-bound targets (Kwong et al., 2008) that are upregulated upon PcG loss are also upregulated in polarity-deficient tissues (Figure 6D). This strong enrichment supports a model whereby the Scrib module and PcG act in concert at certain common downstream genes.

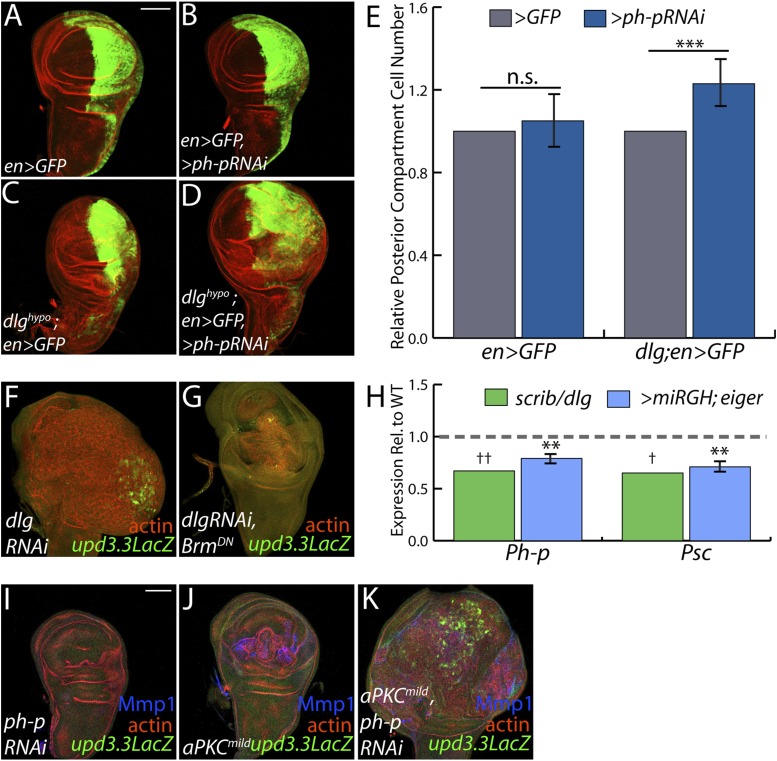

Polarity regulates PcG component transcription to modulate mitogenic gene expression

The above data are consistent with a scenario whereby polarity loss weakens PcG-mediated repression of select targets that promote tumorigenesis. An alternate possibility is that PcG mutant tissue itself is polarity-defective; however, it often maintains polarized organization including areas that upregulate upd3.3lacZ, it does not show transcriptional changes of polarity regulators, and unlike neoplastic tissue it is not suppressed by aPKC inhibition ([Classen et al., 2009], Figure 6—figure supplement 1, data not shown). To assess the functional significance of PcG in neoplastic tissues, we used the genetic interaction assay of Figure 2. Knockdown of the PcG gene polyhomeotic-proximal (ph-p) alone has no effect on growth of WT discs, due to the presence of its paralog polyhomeotic-distal (ph-d). However, when ph-p is knocked down in hypomorphic dlg discs, it significantly increased growth and cell proliferation (Figure 7A–E). Similar results were observed upon knockdown of a second PcG component, Su(Z)2 (data not shown). If reduced PcG function contributes to overgrowth upon polarity loss, then preventing target derepression should suppress neoplastic growth. We inhibited Brahma (Brm), which suppresses PcG-mediated homeotic transformation and often opposes PcG activity at target genes (Tamkun et al., 1992). Expression of dominant-negative Brm reduced both the growth of dlgRNAi-expressing tissue and upd3.3LacZ expression (Figure 7F–G, Figure 4—figure supplement 2A). An analogous experiment with scrib RNAi could not be performed due to synthetic lethality with the Brm-DN transgene. These data support a role for epithelial polarity in promoting PcG-mediated repression of mitogenic target genes to suppress tumorigenesis.

Figure 7. PcGs cooperate with Scrib module proteins to regulate growth.

(A–D) Knockdown of ph-p has little effect on WT growth but increases the growth of dlghypo tissue. Quantification is in E (***p < 0.0001). (F–G) BrmDN expression in dlgRNAi tissue decreases both upd3.3LacZ activation and overgrowth. (H) PcG components ph-p and Psc are downregulated in scrib and dlg mutant tissue (average in green), similar to levels observed upon JNK activation (blue). (**p < 0.005 ✝FDR < 0.05 in one genotype; ✝✝FDR < 0.05 in both genotypes) (I–K) Knockdown of ph-p or expression of a moderately active form of aPKC (aPKCmild) does not induce upd3.3LacZ, and aPKCmild induces only slight overgrowth. However, co-expression of these transgenes leads to strong overgrowth and upd3.3LacZ expression. Scale bar: 100 μm.

The above analyses suggest diminished PcG activity in Scrib module mutant tissues, but do not point to a molecular mechanism. Intriguingly, using a wounding paradigm, Lee et al. found that JNK signaling can partially downregulate PcG expression, facilitating dedifferentiation and regeneration (Lee et al., 2005). Because JNK is activated upon polarity loss, we evaluated PcG transcript levels in Scrib module mutant tissues. Expression of the core PcG components ph-p and Psc is reduced in neoplastic tumors to an extent similar to that seen upon strong JNK activation (Figure 7H), suggesting that JNK signaling upon polarity loss compromises PcG function.

Finally, we tested whether compromised PcG function would promote polarity-responsive enhancer activation under moderate signaling conditions. Mild activation of aPKC drove polarity alterations and a limited degree of neoplasia, along with mild JNK signaling that can activate Mmp1; at these levels, both kinases together were incapable of activating upd3.3 (Figure 7J). However, upon knockdown of ph-p, which does not activate JNK, mild aPKC signaling not only drove robust overgrowth but also upd3.3LacZ upregulation (Figure 7I–K, Figure 4—figure supplement 2D). From these data, we conclude that epithelial polarity normally suppresses neoplasia through PcG in cooperation with JNK and aPKC/Yki pathways.

Discussion

Studies in vertebrate and invertebrate tissues have revealed intimate links between epithelial organization and the control of tumorous characteristics such as cell proliferation, differentiation, and motility. Here, we analyze both global RNA expression and a single polarity-responsive enhancer to delineate the signaling, transcriptional and epigenetic pathways linking epithelial organization to these diverse phenotypes. In polarity-deficient tissues, the simultaneous initiation of Fos-dependent transcription, aPKC-mediated Yki activation, and loss of PcG target repression leads to induction of a broad group of oncogenic factors, including the mitogenic JAK/STAT ligands. Our work provides insight into the logic, as well as the molecular mechanisms, by which polarity maintenance acts as a tumor-suppressive feature.

Linking polarity to growth control

Our data build on those of others showing that JNK, aPKC and Yki are key players in fly neoplasia (Leong et al., 2009; Grzeschik et al., 2010; Robinson et al., 2010; Zhu et al., 2010; Doggett et al., 2011; Sun and Irvine, 2011; Verghese et al., 2012). By focusing on a single enhancer element of a gene involved in tumorous growth, we clarify the role of implicated regulating kinases and define how proliferation can be triggered by each pathway. Inhibition of Fos can suppress upd3 upregulation and neoplasia, indicating that this transcription factor itself is the major target of JNK in this context. Yet a polarity-sensitive enhancer is not fully activated by JNK alone, even when apoptosis is blocked. aPKC is an additional regulator of this enhancer, and as previously suggested (Doggett et al., 2011), can activate Yki independent of, rather than through, JNK. Inhibiting either the JNK or Hpo pathways, including depletion of the downstream transcription factors, prevents expression of the polarity-sensitive enhancer; our analysis predicts that mutating transcription factor binding sites would give the same effect. Knockdown of upd3 alone in neoplastic tumors does not prevent overgrowth (Figure 2—figure supplement 1); upd1 and upd2 are also regulated by JNK, Yki, and PcG (Pastor-Pareja et al., 2008; Classen et al., 2009; Jiang et al., 2009; Staley and Irvine, 2010; Wu et al., 2010) and may act through analogous enhancers to cooperatively drive tumor formation.

Loss of polarity thus induces two separate signaling pathways. An unknown mechanism triggers JNK to induce Fos-dependent transcription, while at the same time mispolarization of aPKC drives Yki-dependent transcription. Under mild signaling conditions, both pathways are required simultaneously to trigger enhancer expression or overgrowth, while inhibition of either is sufficient to suppress neoplasia. We suggest that polarity-responsive enhancers like upd3.3 work as ‘coincidence detectors’ that during normal physiology require inputs from both JNK/Fos and aPKC/Yki. In this way, neither stress nor developmental growth signals alone run the risk of triggering malignant transformation. However, upon severe tissue damage that disrupts the epithelium, both stress and polarity signals are initiated to effect repair pathways (see below).

Our results also emphasize the unexpectedly central role of transcription in mediating cell polarity loss. Inhibition of Fos can revert not only growth defects but also polarity defects of neoplastic tumors. This surprising result suggests that polarity regulation by the Scribble module involves not only antagonistic interactions with the Par module at the cell cortex, but also an important transcriptional component that may be regulated similarly to the mitogenic upd3 enhancer studied here. Nevertheless, activation of JNK, Yki, or both together is insufficient to elicit polarity defects (Figure 5—figure supplement 3), while aPKC activation alone is. Thus, aPKC must have additional effectors through which it regulates transformation; further analysis of the neoplastic transcriptome will shed light on this.

Yki in neoplastic and hyperplastic growth

Yki is clearly a major regulator of neoplastic transformation, providing a link between the primary Drosophila TSG pathways (Grzeschik et al., 2010; Robinson et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2012; Verghese et al., 2012). However, our transcriptional data highlight a major puzzle. Many Hpo pathway targets, including direct growth regulators such as cycE, diap1, and Myc, are expressed at near-normal levels in Scrib module mutants, and comparison of Scrib module and Hpo mutant transcriptomes reveals limited overlap (Figure 5—figure supplement 2A–B). If Yki is activated in both types of tumorous tissue, why do they behave so differently? Our data help to rule out several models for altered Yki target selection. It is unlikely to be driven by simultaneous activation of JNK upon polarity loss, since co-activation of Yki and JNK does not recapitulate neoplastic growth phenotypes (Figure 5—figure supplement 3). It is also unlikely to be explained by a model in which Yki activation through aPKC differs from Yki activation through canonical Hpo pathway regulators, since a transgenic 3.5 kb diap1 fragment is strongly upregulated in neoplastic tissue, paralleling upregulation of a minimal Yki-responsive element (Figure 5—figure supplement 2G–J). Interestingly, an enhancer trap inserted at the same 3.5 kb sequence in the endogenous diap1 locus (Zhang et al., 2008) is only slightly upregulated by comparison (Figure 5—figure supplement 2K–L), hinting that the native chromatin environment at certain Yki targets might influence target response.

Polarity and epigenetic regulation

Our data point to PcG as a new player in the transcriptional response to polarity loss. Three pieces of evidence support a close relationship between the Scrib module and PcGs: (1) their related mutant phenotypes, (2) the extensive and highly significant overlap of their mutant gene expression profiles, and (3) the sensitivity of Scrib module mutant overgrowth to changes in PcG activity. However, since canonical PcG targets including Hox genes are not upregulated in neoplastic tissues (Supplementary files 1–2), and overall Histone H3K27me3 levels are not altered (data not shown), the data rule out a global inactivation of PcG. Instead, they suggest that decreased PcG-mediated repression ‘primes’ select targets for activation by polarity-responsive effector pathways. Mild activation of either JNK or aPKC alone is insufficient to stimulate enhancers such as upd3.3. However, at these targets, reduced PcG activity upon Scrib module loss synergizes with JNK and aPKC signaling, perhaps by providing a permissive chromatin environment for Fos- and Yki-stimulated transcription. More generally, the link to epigenetic regulators that control many targets provides a mechanism by which loss of a single polarity regulator can induce the widespread transcriptional changes that drive the multifaceted neoplastic phenotype.

Tumor characteristics revealed by the neoplastic transcriptome

Our primary analysis focuses on overgrowth, but the transcriptome identifies further features of human cancer found in neoplastic Drosophila cells. In addition to oxidative stress, fly homologs of metabolic genes that fuel human cancer growth are elevated, including fatty acid synthase (FASN) which facilitates de novo lipogenesis, and LDH which promotes aerobic glycolysis in the Warburg effect (Cairns et al., 2011; Baenke et al., 2013; Gorrini et al., 2013). However, glycolytic enzyme transcription in fly neoplastic tumors remains relatively unchanged, suggesting that metabolic changes may be more complex. Dedifferentiation is considered another key feature of human tumor malignancy (Friedmann-Morvinski and Verma, 2014), and the major signature evident from genes downregulated in neoplastic tissues reflects a failure to differentiate. Khan et al. recently reported that forcing differentiation can cause elimination of neoplastic clones (Khan et al., 2013); by contrast, our experiments show that restoring expression of the wing-fate regulator Vg suppresses tumorous overgrowth without inducing cell death. Thus, promoting tissue differentiation may be a tumor suppressive function of epithelial organization.

Why might loss of polarity drive this particular constellation of events that result in tumorous overgrowth? Our global analysis reveals that apicobasal polarity disruption elicits responses with striking parallels to those seen in epithelial wounds in both Drosophila and humans (Schäfer and Werner, 2008; Lee and Miura, 2014). These parallels, which are both thematic and extend to regulation of specific genes, include activation of stress signaling, reactive oxygen species production, upregulation of matrix remodeling enzymes, de-differentiation, recruitment of immune cells, and transcription of growth-promoting cytokines that stimulate cell proliferation. Intriguingly, several upregulated neoplastic effectors that contain conserved AP-1 and Sd binding sites are also upregulated during wound-healing (Pastor-Pareja et al., 2008; Wu et al., 2009; Garelli et al., 2012; Patterson et al., 2013) (Figure 3—figure supplement 2). An attractive model is that linking transcriptional control of such targets to polarity regulators, via polarity-regulated aPKC, cell architecture-regulated Yki and stress-regulated JNK activity on both downstream transcription factors and PcG epigenetic regulators, allows the tissue to connect disturbances in its integrity to the activation of broad gene expression programs that promote repair. Following tissue damage, restoration of tissue architecture and integrity would abrogate wound-response signals. In contrast, in polarity-deficient tissues, architecture can never be restored, and these pro-growth, de-differentiation cues remain active, leading to the formation of malignant tumors that kill the organism. Our data linking apicobasal polarity to neoplastic gene expression thus suggest an evolutionarily ancient genesis for cancers as ‘wounds that never heal’ (Dvorak, 1986).

Materials and methods

Drosophila genetics

The following alleles were used in this study: white [1118] (WT), dlg [40-2], dlg [hf321] (dlghypo) scrib [1], hep [r75] (JNKK), Psc/Su(Z)2 [XL26] (Li et al., 2010), ykiB5. The following additional strains were used: engrailed GAL4, UAS-GFP, ms1096 GAL4, eyFLP; act>>GAL4, UAS-GFP, 10XStat92E-GFP, upd3.1LacZ, upd3.2LacZ, and upd3.3LacZ (Jiang et al., 2011), thj5c8 (Ryoo et al., 2002), diap1-GFP3.5 (Zhang et al., 2008), HREX-GFP (Wu et al., 2008), UAS-Socs36E, UAS-Dome∆cyt (UAS-DomeDN), UAS-BskK53R (UAS-JNKDN), UAS-fospanAla (UAS-FosDN), UAS-miRNAreapergrimhid (UAS-miRGH) (Siegrist et al., 2010), UAS-GFP, UAS-hippo, UAS-eiger, UAS-aPKCΔN (UAS-aPKCact), UAS-ykiS168A (UAS-ykiact), UAS-BrmK804R (UAS-brmDN), UAS-aPKCCAAX (UAS-aPKCmild), UAS-Sod2, UAS-Catalase, UAS-Ey, UAS-vg, and UAS-hepWT (UAS-JNKKWT), AP-1-GFP, ImpL2-GFP, dilp8-GFP, EcadRNAi. UAS-aPKCCAAX UAS-Par6 was a kind gift from T Harris. UAS-dlgRNAi (39035), UAS-dlgRNAi (34854) were obtained from the Bloomington Stock Center; UAS-yki RNAi (104523), UAS-ph-p RNAi (10679), UAS-ph RNAi (50028), and UAS-Su(Z)2 RNAi (100096) were obtained from the Vienna Drosophila RNAi Center. Unless otherwise noted, all transgenes were driven in the wing pouch by ms1096-GAL4. WT controls were outcrosses to w. Crosses were reared at 25°C, except for the crosses to assess upd3.3LacZ expression in scribIR and scribIR;BskDN tissue, which were raised at 29°C.

Immunofluorescence and microscopy

Imaginal discs were fixed and stained (Bilder et al., 2000) with TRITC-phalloidin (Sigma-Adrich, St. Louis, MO) and primary antibodies against the following antigens: β-gal (Abcam, San Francisco, CA), Mmp1, Dlg, Scrib (all from Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, Iowa City, IA) and aPKC (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). DAPI (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) was used to visualize nuclei. Secondary antibodies were from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). DHE staining was performed on live tissue as previously described (Owusu-Ansah et al., 2008). Mutant and WT discs were stained in the same tube and imaged under identical confocal settings. Images are single cross-sections obtained on either a Leica TCS or a Zeiss LSM 700 and processed with Adobe Photoshop CS2 12.0.1. Bgal staining was quantified as the percentage of pixels above background and normalized to WT levels.

mRNA purification, sequencing, and data analysis

At least 50 wing imaginal discs were dissected from white1118, scrib1, and dlg40-2/Y larvae for each biological replicate, and at least two biological replicates were sequenced per genotype. Psc/Su(Z)2 [XL26] FRT42 and control isogenized FRT42 wing discs were generated using UbxFLP; cell-lethal as described (Newsome et al., 2000). Control tissue was isolated 5–6 days after egg lay (AEL), while tumorous discs was isolated 7–8 days AEL to account for the developmental delay of tumor-bearing larvae. Poly-A transcripts were purified via two rounds of extraction using the MicroPolyAPurist kit (Ambion, Austin, TX). mRNA was subsequently prepared for sequencing (Dalton et al., 2013).

Libraries were sequenced by 50-bp single-end reads on either the GAIIX Genome Analyzer or HighSeq2000 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA). Reads were aligned to the Drosophila melanogaster reference genome (version 5.43) using TopHat run under default parameters (Langmead et al., 2009). The number of reads from each replicate falling on each exon was counted using HTSeq (Anders et al., 2015) in the UNION mode, and the differential expression levels across all of samples were calculated using DESeq (Anders and Huber, 2010). Normalized value for gene expression is reported in a single ‘reads per kilobase gene length per million total reads’ (RPKM) value for each gene. Supplementary file 4 contains the sequencing and mapping statistics for each replicate, and Supplementary file 5 contains the number of differentially expressed genes for each genotype.

For binding profile comparison, genes associated with Pc binding (peak_hit, peak_near, gray_hit, gray_near) in thoracic imaginal discs (Kwong et al., 2008) were defined as PcG targets. Genes upregulated at least twofold and having an RPKM value of at least 10.0 in wts mutant tissue were used to assess the overlap of the Scrib module and Hippo pathway mutant transcriptome profiles (Oh et al., 2013). p-values for significance of overlap of transcriptome profiles was found using hypergeometric probability. Gene Ontology analysis was performed using GoStat (Beissbarth and Speed, 2004).

qRT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from at least 20 wing discs co-expressing eiger and miRGH with ms1096 GAL4, along with outcrossed controls, using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), and cDNA was generated from 500 μg of RNA using Superscript II Reverse Transcriptase (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using SYBR GreenER qPCR SuperMix (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) on a StepOnePlus ABI Machine (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Relative gene expression levels were quantified using the ΔΔCT method, after normalization to three endogenous control genes (GAPDH, CG12703, Cp1). Average fold expression of at least four biological replicates is shown. Primer sequences are listed in Supplementary file 6.

Cloning upd3LacZ

Genomic DNA was isolated from adult flies using standard procedures. The upd3 fragment was amplified using Phusion High Fidelity Polymerase (NEB) and the following primers: 5′-GGTGGTACCTCGTACAATGGTTTAAAAATAGCTCGGCCAA-3′ and 5′-GGAAGGCCTCTCCTACACATCGAGCAGCATGGTCAACGAA-3′. The 3-kb fragment was ligated into a pH-Pelican-attB vector and sequence was confirmed. Transformation into the attP2 landing site was performed by BestGene, Inc (Chino Hills, CA).

Fluorescence activated cell Sorting analysis

At least 10 wing discs were dissected and disassociated as described (de la Cruz and Edgar, 2008). Cells were counted using an EPICS XL flow cytometer (Beckman–Coulter, Brea, CA). GFP+ and GFP− gates were generated based on a white1118 negative control sample. To calculate Relative Posterior Compartment Size, the number of GFP+ cells was divided by the total number of live cells and normalized to control discs. A two-tailed Student's t-test was used to calculate the p-values based on at least three biological replicates for each genotype.

Acknowledgements

We thank Huaqi Jiang, Herve Agaisse, Tony Harris, Dirk Bohmann, Richard Mann, and Carl Thummel for sending reagents, and Jason Tennessen for helpful discussions. We particularly thank Justin Dalton and Michelle Arbeitman for RNA-Seq advice. BDB received support from the University of California Cancer Research Coordinating Committee. AKC was a Jane Coffins Child Fellow. This work was supported by a Burroughs Wellcome Fund Career Development award and by NIH RO1 GM090150 to DB.

Funding Statement

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Funding Information

This paper was supported by the following grants:

Burroughs Wellcome Fund (BWF) to David Bilder.

Jane Coffin Childs Memorial Fund for Medical Research Postdoctoral Fellowship to Anne K Classen.

National Institutes of Health (NIH) RO1 GM090150 to David Bilder.

University of California, Davis Cancer Research Coordinating Committee - Graduate student fellowship to Brandon D Bunker.

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that no competing interests exist.

Author contributions

BDB, Conception and design, Acquisition of data, Analysis and interpretation of data, Drafting or revising the article.

TTN, Performed analysis of RNA-Seq data.

RMB, Acquisition of data, Analysis and interpretation of data, Drafting or revising the article.

AKC, Assisted RNA-Seq and RT-PCR experiments.

DB, Conception and design, Analysis and interpretation of data, Drafting or revising the article.

Additional files

Transcriptome Analysis of scrib Tissue. Differential expression analysis of scrib versus white RNA-Seq data by DESeq. Each column contains the following information: Flybase ID- Flybase Gene Identifier; Gene Name- Name of each gene; baseMean_allconditions- Average normalized read count for that gene, across all samples, baseMean_white- Normalized read count for that gene in white tissue; baseMean_scribble- Normalized read count for that gene in scrib tissue; foldChange- Change of the gene in scribble, relative to white tissue; foldChangelog2- Logarithm to base 2 of the fold change; pval- p-value for the statistical significance of the fold change; padj- p-value adjusted for multiple testing with the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure, which controls for false discovery rate (FDR).

Transcriptome Analysis of dlg Tissue. Differential expression analysis of dlg versus white RNA-Seq data by DESeq. Each column contains the following information: Flybase ID- Flybase Gene Identifier; Gene Name- Name of each gene; baseMean_allconditions- Average normalized read count for that gene, across all samples, baseMean_white- Normalized read count for that gene in white tissue; baseMean_discslarge- Normalized read count for that gene in dlg tissue; foldChange- Change of the gene in dlg, relative to white tissue; foldChangelog2- Logarithm to base 2 of the fold change; pval- p-value for the statistical significance of the fold change; padj- p-value adjusted for multiple testing with the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure, which controls for false discovery rate (FDR).

Transcriptome Analysis of Psc/Su(Z)2 Tissue. Differential expression analysis of scrib versus white RNA-Seq data by DESeq. Each column contains the following information: Flybase ID- Flybase Gene Identifier; Gene Name- Name of each gene; baseMean_allconditions- Average normalized read count for that gene, across all samples, baseMean_iso- Normalized read count for that gene in iso42 tissue; baseMean_PscSuZ2- Normalized read count for that gene in Psc/Su(Z)2 tissue; foldChange- Change of the gene in scribble, relative to white tissue; foldChangelog2- Logarithm to base 2 of the fold change; pval- p-value for the statistical significance of the fold change; padj- p-value adjusted for multiple testing with the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure, which controls for false discovery rate (FDR).

RNA-Seq alignment statistics. Table of combined number of 50-bp single-end sequencing reads for each sequencing replicate. Reads were considered ‘non-aligned’ if they had >2 mismatches relative to the reference genome, and ‘low complexity’ reads had multiple matches within the genome, reflecting sequencing reads from repeated DNA elements. Percentages listed refer to the number of reads for each category relative to the total number of reads.

Contains the number of differentially expressed genes for each genotype.

Contains the primer sequences used for quantitative PCR in Figure 7.

References

- Anders S, Huber W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biology. 2010;11:R106. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-10-r106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anders S, Pyl PT, Huber W. HTSeq–A Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:166–169. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baenke F, Peck B, Miess H, Schulze A. Hooked on fat: the role of lipid synthesis in cancer metabolism and tumour development. Disease Models & Mechanisms. 2013;6:1353–1363. doi: 10.1242/dmm.011338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beissbarth T, Speed TP. GOstat: find statistically overrepresented Gene Ontologies within a group of genes. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:1464–1465. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilder D. Epithelial polarity and proliferation control: links from the Drosophila neoplastic tumor suppressors. Genes & Development. 2004;18:1909–1925. doi: 10.1101/gad.1211604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilder D, Li M, Perrimon N. Cooperative regulation of cell polarity and growth by Drosophila tumor suppressors. Science. 2000;289:113–116. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5476.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilder D, Perrimon N. Localization of apical epithelial determinants by the basolateral PDZ protein Scribble. Nature. 2000;403:676–680. doi: 10.1038/35001108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns RA, Harris IS, Mak TW. Regulation of cancer cell metabolism. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2011;11:85–95. doi: 10.1038/nrc2981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callus BA, Mathey-Prevot B. SOCS36E, a novel Drosophila SOCS protein, suppresses JAK/STAT and EGF-R signalling in the imaginal wing disc. Oncogene. 2002;21:4812–4821. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CL, Schroeder MC, Kango-Singh M, Tao C, Halder G. Tumor suppression by cell competition through regulation of the Hippo pathway. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of USA. 2012;109:484–489. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113882109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciapponi L, Jackson DB, Mlodzik M, Bohmann D. Drosophila Fos mediates ERK and JNK signals via distinct phosphorylation sites. Genes & Development. 2001;15:1540–1553. doi: 10.1101/gad.886301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Classen AK, Bunker BD, Harvey KF, Vaccari T, Bilder D. A tumor suppressor activity of Drosophila Polycomb genes mediated by JAK-STAT signaling. Nature Genetics. 2009;41:1150–1155. doi: 10.1038/ng.445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombani J, Andersen DS, Léopold P. Secreted peptide Dilp8 coordinates Drosophila tissue growth with developmental timing. Science. 2012;336:582–585. doi: 10.1126/science.1216689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordero JB, Macagno JP, Stefanatos RK, Strathdee KE, Cagan RL, Vidal M. Oncogenic Ras Diverts a host TNF tumor suppressor activity into tumor Promoter. Developmental Cell. 2010;18:999–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton JE, Fear JM, Knott S, Baker BS, McIntyre LM, Arbeitman MN. Male-specific Fruitless isoforms have different regulatory roles conferred by distinct zinc finger DNA binding domains. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:659. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Cruz AF, Edgar BA. Flow cytometric analysis of Drosophila cells. Methods in Molecular Biology. 2008;420:373–389. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-583-1_24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doggett K, Grusche FA, Richardson HE, Brumby AM. Loss of the Drosophila cell polarity regulator Scribbled promotes epithelial tissue overgrowth and cooperation with oncogenic Ras-Raf through impaired Hippo pathway signaling. BMC Developmental Biology. 2011;11:57. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-11-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong J, Feldmann G, Huang J, Wu S, Zhang N, Comerford SA, Gayyed MF, Anders RA, Maitra A, Pan D. Elucidation of a universal size-control mechanism in Drosophila and mammals. Cell. 2007;130:1120–1133. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak HF. Tumors: wounds that do not heal: similarities between tumor stroma generation and wound healing. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1986;315:1650–1659. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198612253152606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsum I, Yates L, Humbert PO, Richardson HE. The Scribble-Dlg-Lgl polarity module in development and cancer: from flies to man. Essays in Biochemistry. 2012;53:141–168. doi: 10.1042/bse0530141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsum IA, Yates LL, Pearson HB, Phesse TJ, Long F, O'Donoghue R, Ernst M, Cullinane C, Humbert PO. Scrib heterozygosity predisposes to lung cancer and cooperates with KRas hyperactivation to accelerate lung cancer progression in vivo. Oncogene. 2014;33:5523–5533. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feigin ME, Akshinthala SD, Araki K, Rosenberg AZ, Muthuswamy LB, Martin B, Lehmann BD, Berman HK, Pietenpol JA, Cardiff RD, Muthuswamy SK. Mislocalization of the cell polarity protein scribble promotes mammary tumorigenesis and is associated with basal breast cancer. Cancer Research. 2014;74:3180–3194. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-3415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa-Clarevega A, Bilder D. Malignant Drosophila tumors interrupt insulin signaling to induce cachexia-like wasting. Developmental Cell. 2015;33 doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.03.001. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann-Morvinski D, Verma IM. Dedifferentiation and reprogramming: origins of cancer stem cells. EMBO Reports. 2014;15:244–253. doi: 10.1002/embr.201338254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garelli A, Gontijo AM, Miguela V, Caparros E, Dominguez M. Imaginal discs secrete insulin-like peptide 8 to mediate plasticity of growth and maturation. Science. 2012;336:579–582. doi: 10.1126/science.1216735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gateff E, Schneiderman HA. Neoplasms in mutant and cultured wild-tupe tissues of Drosophila. National Cancer Institute Monograph. 1969;31:365–397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorrini C, Harris IS, Mak TW. Modulation of oxidative stress as an anticancer strategy. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2013;12:931–947. doi: 10.1038/nrd4002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grzeschik NA, Parsons LM, Allott ML, Harvey KF, Richardson HE. Lgl, aPKC, and Crumbs regulate the Salvador/Warts/Hippo pathway through two distinct mechanisms. Current Biology. 2010;20:573–581. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.01.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L, Muthuswamy SK. Polarity protein alterations in carcinoma: a focus on emerging roles for polarity regulators. Current Opinion in Genetics & Development. 2010;20:41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igaki T, Kanda H, Yamamoto-Goto Y, Kanuka H, Kuranaga E, Aigaki T, Miura M. Eiger, a TNF superfamily ligand that triggers the Drosophila JNK pathway. The EMBO Journal. 2002;21:3009–3018. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, Grenley MO, Bravo M-J, Blumhagen RZ, Edgar BA. EGFR/Ras/MAPK signaling mediates adult midgut epithelial homeostasis and regeneration in Drosophila. Stem Cell. 2011;8:84–95. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, Patel PH, Kohlmaier A, Grenley MO, McEwen DG, Edgar BA. Cytokine/Jak/Stat signaling mediates regeneration and homeostasis in the Drosophila midgut. Cell. 2009;137:1343–1355. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan SJ, Bajpai A, Alam MA, Gupta RP, Harsh S, Pandey RK, Goel-Bhattacharya S, Nigam A, Mishra A, Sinha P. Epithelial neoplasia in Drosophila entails switch to primitive cell states. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of USA. 2013;110:E2163–E2172. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1212513110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Külshammer E, Uhlirova M. The actin cross-linker Filamin/Cheerio mediates tumor malignancy downstream of JNK signaling. Journal of Cell Science. 2013;126:927–938. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwong C, Adryan B, Bell I, Meadows L, Russell S, Manak JR, White R. Stability and dynamics of polycomb target sites in Drosophila development. PLOS Genetics. 2008;4:e1000178. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landis GN, Abdueva D, Skvortsov D, Yang J, Rabin BE, Carrick J, Tavaré S, Tower J. Similar gene expression patterns characterize aging and oxidative stress in Drosophila melanogaster. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of USA. 2004;101:7663–7668. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307605101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biology. 2009;10:R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebestky T, Chang T, Hartenstein V, Banerjee U. Specification of Drosophila hematopoietic lineage by conserved transcription factors. Science. 2000;288:146–149. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5463.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee N, Maurange C, Ringrose L, Paro R. Suppression of Polycomb group proteins by JNK signalling induces transdetermination in Drosophila imaginal discs. Nature. 2005;438:234–237. doi: 10.1038/nature04120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee WJ, Miura M. Mechanisms of systemic wound response in Drosophila. Current Topics in Developmental Biology. 2014;108:153–183. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-391498-9.00001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leong GR, Goulding KR, Amin N, Richardson HE, Brumby AM. Scribble mutants promote aPKC and JNK-dependent epithelial neoplasia independently of Crumbs. BMC Biology. 2009;7:62. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-7-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Han Y, Xi R. Polycomb group genes Psc and Su(z)2 restrict follicle stem cell self-renewal and extrusion by controlling canonical and noncanonical Wnt signaling. Genes & Development. 2010;24:933–946. doi: 10.1101/gad.1901510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim H-Y, Wang W, Chen J, Ocorr K, Bodmer R. ROS regulate cardiac function via a distinct paracrine mechanism. Cell Reports. 2014;7:35–44. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.02.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Belmonte F, Perez-Moreno M. Epithelial cell polarity, stem cells and cancer. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2011;12:23–38. doi: 10.1038/nrc3169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthuswamy SK, Xue B. Cell polarity as a regulator of cancer cell behavior plasticity. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology. 2012;28:599–625. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-092910-154244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newsome TP, Asling B, Dickson BJ. Analysis of Drosophila photoreceptor axon guidance in eye-specific mosaics. Development. 2000;127:851–860. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.4.851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh H, Irvine KD. In vivo regulation of yorkie phosphorylation and localization. Development. 2008;135:1081–1088. doi: 10.1242/dev.015255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh H, Slattery M, Ma L, Crofts A, White KP, Mann RS, Irvine KD. Genome-wide association of yorkie with chromatin and chromatin-remodeling Complexes. Cell Reports. 2013;3:309–318. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohsawa S, Sato Y, Enomoto M, Nakamura M, Betsumiya A, Igaki T. Mitochondrial defect drives non-autonomous tumour progression through Hippo signalling in Drosophila. Nature. 2012;490:547–551. doi: 10.1038/nature11452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owusu-Ansah E, Banerjee U. Reactive oxygen species prime Drosophila haematopoietic progenitors for differentiation. Nature. 2009;461:537–541. doi: 10.1038/nature08313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owusu-Ansah E, Yavari A, Banerjee U. A protocol for in vivo detection of reactive oxygen species. Nature Protocol Exchange 2008 [Google Scholar]

- Pagliarini RA, Xu T. A genetic screen in Drosophila for metastatic behavior. Science. 2003;302:1227–1231. doi: 10.1126/science.1088474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker PJ, Justilien V, Riou P, Linch M, Fields AP. Atypical protein kinase Cι as a human oncogene and therapeutic target. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2014;88:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2013.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastor-Pareja JC, Wu M, Xu T. An innate immune response of blood cells to tumors and tissue damage in Drosophila. Disease Models & Mechanisms. 2008;1:144–154. doi: 10.1242/dmm.000950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson RA, Juarez MT, Hermann A, Sasik R, Hardiman G, McGinnis W. Serine proteolytic pathway activation reveals an expanded ensemble of wound response genes in Drosophila. PLOS ONE. 2013;8:e61773. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson HB, Perez-Mancera PA, Dow LE, Ryan A, Tennstedt P, Bogani D, Elsum I, Greenfield A, Tuveson DA, Simon R, Humbert PO. SCRIB expression is deregulated in human prostate cancer, and its deficiency in mice promotes prostate neoplasia. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2011;121:4257–4267. doi: 10.1172/JCI58509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Garijo A, Shlevkov E, Morata G. The role of Dpp and Wg in compensatory proliferation and in the formation of hyperplastic overgrowths caused by apoptotic cells in the Drosophila wing disc. Development. 2009;136:1169–1177. doi: 10.1242/dev.034017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson BS, Huang J, Hong Y, Moberg KH. Crumbs regulates Salvador/Warts/Hippo signaling in Drosophila via the FERM-domain protein expanded. Current Biology. 2010;20:582–590. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson BS, Moberg KH. Drosophila endocytic neoplastic tumor suppressor genes regulate Sav/Wts/Hpo signaling and the c-Jun N-terminal kinase pathway. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:4110–4118. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.23.18243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryoo HD, Bergmann A, Gonen H, Ciechanover A, Steller H. Regulation of Drosophila IAP1 degradation and apoptosis by reaper and ubcD1. Nature Cell Biology. 2002;4:432–438. doi: 10.1038/ncb795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schäfer M, Werner S. Cancer as an overhealing wound: an old hypothesis revisited. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2008;9:628–638. doi: 10.1038/nrm2455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheel C, Weinberg RA. Cancer stem cells and epithelial–mesenchymal transition: concepts and molecular links. Seminars in Cancer Biology. 2012;22:396–403. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegrist SE, Haque NS, Chen C-H, Hay BA, Hariharan IK. Inactivation of both foxo and reaper promotes long-Term adult neurogenesis in Drosophila. Current Biology. 2010;20:643–648. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.01.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St Johnston D, Ahringer J. Cell polarity in eggs and epithelia: parallels and diversity. Cell. 2010;141:757–774. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staley BK, Irvine KD. Warts and Yorkie mediate intestinal regeneration by influencing stem cell proliferation. Current Biology. 2010;20:1580–1587. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.07.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun G, Irvine KD. Regulation of Hippo signaling by Jun kinase signaling during compensatory cell proliferation and regeneration, and in neoplastic tumors. Developmental Biology. 2011;350:139–151. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.11.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun G, Irvine KD. Ajuba family proteins link JNK to Hippo signaling. Science Signaling. 2013;6:ra81. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamkun JW, Deuring R, Scott MP, Kissinger M, Pattatucci AM, Kaufman TC, Kennison JA. Brahma: a regulator of Drosophila homeotic genes structurally related to the yeast transcriptional activator SNF2/SWI2. Cell. 1992;68:561–572. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90191-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tepass U. The apical polarity protein network in Drosophila epithelial cells: regulation of polarity, Junctions, Morphogenesis, cell growth, and survival. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology. 2012;28:655–685. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-092910-154033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlirova M, Bohmann D. JNK-and Fos-regulated Mmp1 expression cooperates with Ras to induce invasive tumors in Drosophila. The EMBO Journal. 2006;25:5294–5304. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verghese S, Waghmare I, Kwon H, Hanes K, Kango-Singh M. Scribble acts in the Drosophila fat-hippo pathway to regulate warts activity. PLOS ONE. 2012;7:e47173. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S, Liu Y, Zheng Y, Dong J, Pan D. The TEAD/TEF family protein scalloped mediates transcriptional output of the hippo growth-regulatory pathway. Developmental Cell. 2008;14:388–398. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu M, Pastor-Pareja JC, Xu T. Interaction between RasV12 and scribbled clones induces tumour growth and invasion. Nature. 2010;463:545–548. doi: 10.1038/nature08702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Brock AR, Wang Y, Fujitani K, Ueda R, Galko MJ. A blood-borne PDGF/VEGF-like ligand initiates wound-induced epidermal cell migration in Drosophila larvae. Current Biology. 2009;19:1473–1477. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Ren F, Zhang Q, Chen Y, Wang B, Jiang J. The TEAD/TEF family of transcription factor scalloped mediates hippo signaling in organ size control. Developmental Cell. 2008;14:377–387. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu M, Xin T, Weng S, Gao Y, Zhang Y, Li Q, Li M. Activation of JNK signaling links lgl mutations to disruption of the cell polarity and epithelial organization in Drosophila imaginal discs. Cell Research. 2010;20:242–245. doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Transcriptome Analysis of scrib Tissue. Differential expression analysis of scrib versus white RNA-Seq data by DESeq. Each column contains the following information: Flybase ID- Flybase Gene Identifier; Gene Name- Name of each gene; baseMean_allconditions- Average normalized read count for that gene, across all samples, baseMean_white- Normalized read count for that gene in white tissue; baseMean_scribble- Normalized read count for that gene in scrib tissue; foldChange- Change of the gene in scribble, relative to white tissue; foldChangelog2- Logarithm to base 2 of the fold change; pval- p-value for the statistical significance of the fold change; padj- p-value adjusted for multiple testing with the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure, which controls for false discovery rate (FDR).

Transcriptome Analysis of dlg Tissue. Differential expression analysis of dlg versus white RNA-Seq data by DESeq. Each column contains the following information: Flybase ID- Flybase Gene Identifier; Gene Name- Name of each gene; baseMean_allconditions- Average normalized read count for that gene, across all samples, baseMean_white- Normalized read count for that gene in white tissue; baseMean_discslarge- Normalized read count for that gene in dlg tissue; foldChange- Change of the gene in dlg, relative to white tissue; foldChangelog2- Logarithm to base 2 of the fold change; pval- p-value for the statistical significance of the fold change; padj- p-value adjusted for multiple testing with the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure, which controls for false discovery rate (FDR).

Transcriptome Analysis of Psc/Su(Z)2 Tissue. Differential expression analysis of scrib versus white RNA-Seq data by DESeq. Each column contains the following information: Flybase ID- Flybase Gene Identifier; Gene Name- Name of each gene; baseMean_allconditions- Average normalized read count for that gene, across all samples, baseMean_iso- Normalized read count for that gene in iso42 tissue; baseMean_PscSuZ2- Normalized read count for that gene in Psc/Su(Z)2 tissue; foldChange- Change of the gene in scribble, relative to white tissue; foldChangelog2- Logarithm to base 2 of the fold change; pval- p-value for the statistical significance of the fold change; padj- p-value adjusted for multiple testing with the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure, which controls for false discovery rate (FDR).

RNA-Seq alignment statistics. Table of combined number of 50-bp single-end sequencing reads for each sequencing replicate. Reads were considered ‘non-aligned’ if they had >2 mismatches relative to the reference genome, and ‘low complexity’ reads had multiple matches within the genome, reflecting sequencing reads from repeated DNA elements. Percentages listed refer to the number of reads for each category relative to the total number of reads.

Contains the number of differentially expressed genes for each genotype.

Contains the primer sequences used for quantitative PCR in Figure 7.