Abstract

P-wave dispersion is a non invasive indicator of intra-atrial conduction heterogeneity producing substrate for reentry, which is a pathophysiological mechanism of atrial fibrillation. The relationship between P-wave dispersion (PD) and atrial fibrillation (AF) in Myotonic dystrophy type 1 (DM1) patients is still unclear. Atrial Preference Pacing (APP) is an efficient algorithm to prevent paroxysmal AF in patients implanted with dual-chamber pacemaker. Aim of our study was to evaluate the possible correlation between atrial preference pacing algorithm, P-wave dispersion and AF burden in DM1 patients with normal cardiac function underwent permanent dual-chamber pacemaker implantation.

We enrolled 50 patients with DM1 (age 50.3 ± 7.3; 11 F) underwent dual-chamber pacemaker implantation for various degree of atrioventricula block. The study population was randomized following 1 months stabilization period to APP algorithm features programmed OFF or ON. Patients were assessed every 3 months for the first year, and every 6 months thereafter up to 3 years. At each follow-up visit, we counted: the number of premature atrial beats, the number and the mean duration of AF episodes, AF burden and the percentage of atrial and ventricular pacing.

APP ON Group showed lower number of AF episodes (117 ± 25 vs. 143 ± 37; p = 0.03) and AF burden (3059 ± 275 vs. 9010 ± 630 min; p < 0.04) than APP OFF Group. Atrial premature beats count (44903 ± 30689 vs. 13720 ± 7717 beats; p = 0.005) and Pwave dispersion values (42,1 ± 11 ms vs. 29,1 ± 4,2 ms, p = 0,003) were decreased in APP ON Group. We found a significant positive correlation between PD and AF burden (R = 0,8, p = 0.007).

Atrial preference pacing algorithm, decreasing the number of atrial premature beats and the P-wave dispersion, reduces the onset and perpetuator factors of AF episodes and decreases the AF burden in DM1 patients underwent dual chamber pacemaker implantation for various degree of atrioventricular blocks and documented atrial fibrillation.

Key words: atrial fibrillation, Myotonic Dystrophy, atrial preference pacing

Introduction

Myotonic dystrophy type 1 (DM1), or Steinert disease, is a serious autosomal-dominant hereditary disease with an estimated incidence of 1 in 8,000 births. It is caused by an abnormal expansion of an unstable trinucleotide repeat in the three-prime untranslated region of DMPK gene on chromosome 19. The cardiac involvement is noticed in about 80% of cases, and it often precedes the skeletal muscle one (1-3). Heart failure (HF) often occurs late in the course of the disease as a consequence of cardiac myopathy due to progressive scar replacement (4-6). Arrhythmias and/or conduction defects are frequent, occurring in 50-65% of patients with DM1 (7). Heart block is the first and most clinically significant cardiac disease in this group of patients and it is related to fibrosis of the conduction system and fatty infiltration of the His bundle (8). Paroxysmal atrial arrhythmias (atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, atrial tachycardia) frequently occur in DM1 patients (9). P-wave dispersion is a non invasive indicator of intra-atrial conduction heterogeneity producing substrate for reentry, which is a pathophysiological mechanism of atrial fibrillation (10, 11). The role of Pwave dispersion (PD) as independent risk factor for atrial fibrillation (AF) development in DM1 patients is still unclear. Atrial Preference Pacing (APP) is an efficient algorithm to prevent paroxysmal AF in patients implanted with dual-chamber pacemaker and significantly reduces the atrial fibrillation episodes and burden (defined as the quantity of AF -minutes/day- retrieved from the device data logs) in DM1 patients (12-14). Aim of our study was to evaluate the possible correlation between atrial preference pacing algorithm, P-wave dispersion and AF burden in DM1 patients with conserved systolic and diastolic function underwent permanent dual-chamber pacemaker implantation.

Materials and methods

Patients selection

From a large cohort of 240 DM1 patients, referred to Cardiomyology and Medical Genetics, Department of Experimental Medicine of Second University of Naples, we enrolled 60 DM1 patients underwent to dual chamber pacemaker with atrial preference pacing (APP) algorithm for various grade of atrioventricular blocks and with documented atrial fibrillation detected by 12-lead surface electrocardiogram (ECG) or 24-h ECG Holter monitoring.

The diagnosis of Steinert disease, firstly based on family history and clinical evaluation, had been subsequently confirmed by genetic test in all patients, to evaluate the CTG triplet expansion. We excluded from the study all DM1 patients with patent foramen ovale, atrial septal aneurysm, severe mitral stenosis or regurgitation, coronary bypass or valvular heart surgery, sick sinus syndrome, or inducible ventricular tachycardia. Subjects with a history of hypertension (systolic and diastolic blood pressure > 140/90 mmHg), diabetes mellitus or impaired glucose tolerance, obesity, electrolyte imbalance, systolic and diastolic dysfunction, connective tissue disorders, hepatic, renal, thyroid diseases, and sleep disorders were excluded from the study. The study was conducted according to the declaration of Helsinki.

Study protocol

DM1 eligible patients underwent dual-chamber pacemaker implantation were randomized following 1 month stabilization period to APP algorithm features programmed OFF or ON. Pharmacological therapy was required to remain stable. Patients were assessed every 3 months for the first year, and every 6 months thereafter up to 3 years. At each follow-up visit the study population underwent medical history, physical examination, 12-lead surface ECG, 2D color Doppler echocardiogram and device interrogation. Patients interrupted the followup, before completing the 3 years, in the case of severely symptomatic AT/AF requiring major changes in therapy.

Pacemaker implantation and programming

All DM1 patients were implanted with a dualchamber PM system (Medtronic Adapta ADDR01, Medtronic Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA). The right ventricular lead (Medtronic 4074 CapSure Sense) was positioned in the apex, under fluoroscopic guidance; the bipolar atrial screw-in lead (Medtronic 5076 CapSure- Fix) was positioned in the right atrial appendage or on the right side of the inter-atrial septum in the region of Bachmann's bundle, according to optimal site, defined as the location with lowest pacing and highest sensing thresholds. To minimize confounding variables with different electrode materials and inter-electrode pacing, an identical model lead was used in all patients. Similarly, PMs with identical behaviour and telemetric capabilities were used to assure accuracy in comparing measurements among patients. To minimize atrial lead oversensing, the sensitivity configuration was bipolar. All devices were programmed in DDD mode with a lower rate of 60 bpm and an upper rate of 120 bpm. Mode switches were programmed for atrial rates > 200 bpm, persisting for more than 12 ventricular beats. Managed Ventricular Pacing algorithm (MVP, Medtronic Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA) was enable in order to promote the intrinsic conduction and reduce the possible influence of high percentage ventricular pacing on atrial fibrillation incidence. Atrial Preference Pacing (APP, Medtronic Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA) was enable according to the prospective programming compliance criteria. The devices used in this study were programmed to detect the episodes of atrial tachycardia, and to record summary and detailed data, atrial and ventricular electrograms (EGMs) included.

Electrocardiographic measurements

All subjects underwent a routine standard 12-lead surface ECG recorded at a paper speed of 50 mm/s and gain of 10 mm/mV in the supine position and were breathing freely but not allowed to speak during the ECG recording. To avoid diurnal variations, we generally took the ECG recordings at the same time (9:00- 10:00 a.m.). The analysis was performed by one investigator only without knowledge of subject's clinical status. ECGs were transferred to a personal computer by an optical scanner and then magnified 400 times by Adobe Photoshop software (Adobe Systems Inc., San Jose, CA, USA). P-wave duration measurement was manually performed with the use of computer software (Configurable Measurement System). Intraobserver coefficients of variation for P-wave variables were found to be less than 5% and not significant. In each electrocardiogram lead, the analysis included three consecutive heart cycles wherever possible. ECG with measurable P-wave in less than ten leads were excluded from analysis. The onset of P-wave was defined as the junction between the isoelectric line and the start of P-wave deflection; the offset of the P-wave was defined as the junction between the end of the Pwave deflection and the isoelectric line (15). If starting and endpoints were not clear, the derivations including these points were taken as excluding criteria from the study. Maximum and minimum P-wave durations were measured. Maximum P-wave duration was defined as the longest P-wave duration, and minimum P-wave duration was defined as the shortest P-wave duration. PD was defined as the difference between the maximum and minimum P-wave durations.

Echocardiography measurements

All echocardiographic examinations were performed using a standard ultrasound machine with a 3.5-MHz phased-array probe (M3S). All patients were examined in the left lateral and supine positions by precordial M-mode, 2-dimensional and Doppler echocardiography. One lead ECG was recorded continuously. Left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD), left ventricular end-systolic diameter (LVESD), interventricular septum thickness (IVST) and left ventricular posterior wall thickness (LVPWT) were measured from M-mode in the parasternal long-axis views according to the standards of the American Society of Echocardiography. Left ventricular mass (LVM) was calculated by using Devereux's formula, and was indexed for body surface area and height. Left atrium diameter (LAD) was measured during systole along the parasternal longaxis view from the 2-dimensional guided M-mode tracing; LA length was measured from the apical 4-chamber view during systole. The maximum LA volume (LAV) was calculated from apical 4- and 2-chamber zoomed views of the LA using the biplane method of disks. Ejection fraction was measured using a modified Simpson biplane method. Each representative value was obtained from the average of 3 measurements. Pulsed-wave Doppler examination was performed to obtain the following indices of LV diastolic function: peak mitral inflow velocities at early (E) and late (A) diastole and E/A ratio. Average values of these indices obtained from 5 consecutive cardiac cycles were used for analysis.

Device interrogation and data analysis

All DM1 patients underwent device interrogation to evaluate sensing/pacing parameters, leads impedance and battery voltage. The devices used in this study were programmed to detect the episodes of atrial tachycardia and to record summary and detailed data, atrial and ventricular electrograms (EGMs) included.

We counted:

the number of premature atrial beats;

the number and the mean duration of AF episodes occurred;

AF burden – defined as the quantity of AF (minutes/ day) retrieved from the device data logs;

the percentage of atrial and ventricular pacing in synchronous rhythm during the collection period.

Atrial tachycardia episodes, identified by regular atrial activity, were excluded from the analysis.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analysis was performed using Student's t-test for unpaired data. p values < 0.5 were considered to be statistically significant. Analyses were performed using the statistical package SPSS 11.0 software for Windows SPSS Inc. (Chicago, IL, USA). The relationships between PD and AF burden were evaluated by linear regression analysis.

Endpoints

Primary endpoints were the number, mean duration and burden of AF episodes and their correlation to PD between APP ON Group and APP OFF Group during 36-months follow-up. Secondary endpoints were the overall number of premature atrial beats and the percentage of atrial and ventricular pacing in synchronous rhythm during the observation period.

Results

Patients population

From the cohort of 60 DM1 patients, 10 patients were excluded due to: far-field ventricular sensing despite refractory periods reprogramming (three cases) after implantation; atrial undersensing (four cases) and persistent AF during follow-up (three cases). Finally, the study group included 50 patients with DM1 (age 50.3 ± 7.3; 11 F), who underwent dual-chamber PM implantation in our division for first-degree atrioventricular block with a pathological infra-Hissian conduction (18 patients), symptomatic type 1 (12 patients), and type 2 (20 patients) second-degree block.

The study population was randomized and treated according to the protocol. No statistically significant difference in the electrical parameters (P-wave amplitude, pacing threshold, and lead impedance) and medication intake was found at implantation between the patients with right atrial appendage (RAA) and Bachmann's bundle (BB) lead placement. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the study population.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population. LVEDD (left ventricular end diastolic diameter), LVESD (left ventricular end systolic diameter), IVST (interventricular septum thickness), LVPWT (left ventricle posterior wall thickness).

| Patients (n) | 50 |

| Age (years) | 50,3 ± 7,3 |

| Sex (M/F) | 39/11 |

| Atrioventricular block I grade | 18 |

| Atrioventricular block II grade type 1 | 12 |

| Atrioventricular block II grade type 2 | 20 |

| QRS duration (ms) | 93 ± 13 |

| LVEDD (mm) | 42,7 ± 9 |

| LVESD (mm) | 27,24 ± 2,8 |

| IVST (mm) | 9,7 ± 1,3 |

| LVPWT (mm) | 9,9 ± 1,5 |

| Ejection fraction (%) | 60,39 ± 4 |

| E wave (cm/s) | 82,3 ± 15,5 |

| A wave (cm/s) | 57,9 ± 9,5 |

| E/A ratio | 1,5 ± 0,5 |

Atrial preference pacing and atrial fibrillation

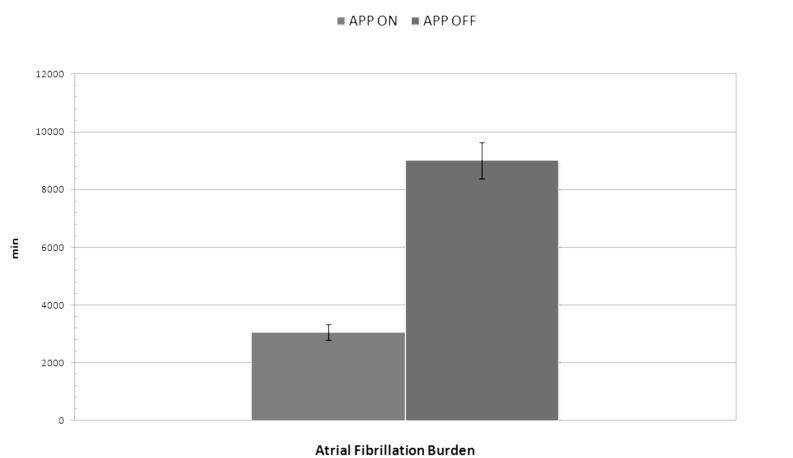

A statistically significant difference was found in the number of AF episodes between no treatment group (APP OFF) and active treatment (APP ON) group in DM1 population study during the follow-up period. The number of AF episodes in APP ON Group was lower than those registered in APP OFF Group (117 ± 25 vs. 143 ± 37; p = 0.03). No statistically significant difference was found in AF episodes mean duration between the two groups (47 ± 17 vs. 43 ± 13 min; p = 0.4). AF burden was lower in APP ON Group than in APP OFF Group (3059 ± 275 vs. 9010 ± 630 min; p < 0.04) (Fig. 1). In APP OFF group and APP ON group, the atrial pacing percentage were 0 and 98%, respectively, while the ventricular pacing percentage did not show statistically significant difference (27 vs. 29%; p = 0.2). Atrial premature beats count was significantly greater in APP OFF group than in APP ON group (44903 ± 30689 vs. 13720 ± 7717 beats; p = 0.005). There was no significant difference in the atrial pacing capture, sensing threshold, and atrial lead impedances at implant and at 36-month follow-up. Lead parameters remained stable over time and there were no lead-related complications. All data are shown in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Difference in atrial fibrillation burden between APP ON Group and APP OFF Group (3059 ± 275 vs. 9010 ± 630 min; p < 0.04).

Table 2.

Differences in the number of AF episodes, AF episodes mean duration, AF burden, atrial and ventricular pacing percentage, atrial premature beats and lead parameters between the two groups.

| APP ON Group | APP OFF Group | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| AF episodes numbers(n) | 117 ± 25 | 143 ± 37 | 0,03 |

| AF episodes mean duration (min) | 47 ± 17 | 43 ± 13 | 0,4 |

| AF burden (min) | 3059 ± 275 | 9010 ± 630 | 0,04 |

| Atrial pacing percentage (%) | 98 | 0 | |

| Ventricular pacing percentage (%) | 27 | 29 | 0,2 |

| Atrial premature beats | 13720 ± 7717 | 44903 ± 30689 | 0,005 |

| Atrial pacing threshold (V) | 0,7 ± 3 | 0,9 ± 2 | 0,6 |

| Atrial sensing threshold (mV) | 5 ± 3 | 7± 2 | 0,6 |

| Atrial lead impedance (ohm) | 582 ± 18 | 622 ± 12 | 0,7 |

| Ventricular pacing threshold (V) | 0,8 ± 3 | 0,6 ± 3 | 0,6 |

| Ventricular sensing threshold (mV) | 15 ± 5 | 17 ± 4 | 0,7 |

| Ventricular lead impedance (ohm) | 769 ± 45 | 889 ± 37 | 0,5 |

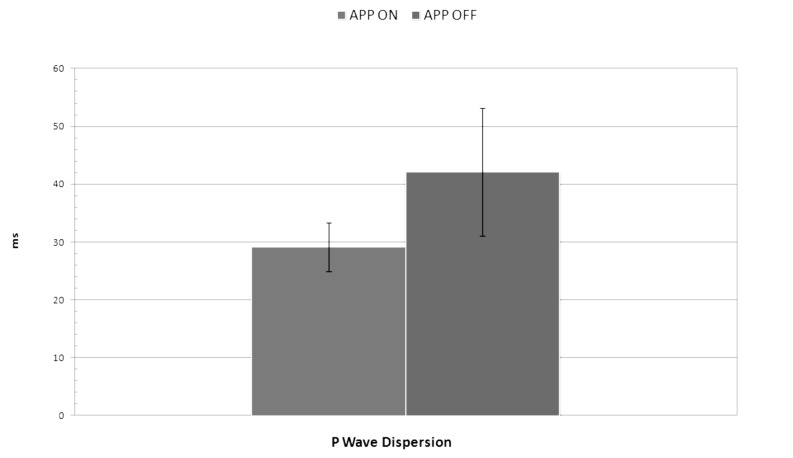

P-wave Duration and Dispersion

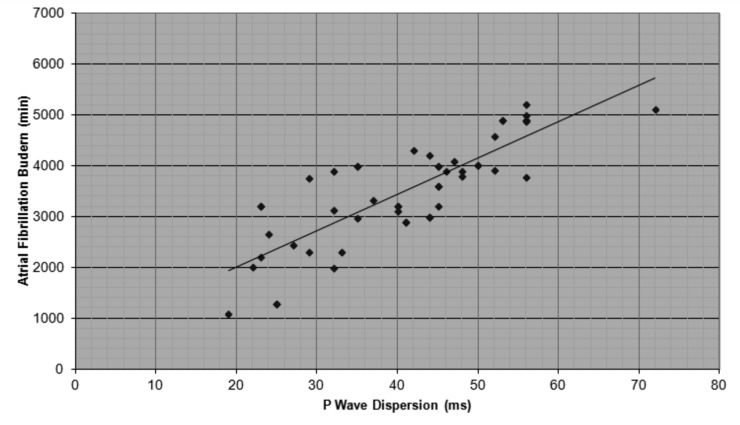

APP OFF Group showed increased maximum P-wave duration (109,4 ± 10,9 ms vs. 69,8 ± 8.2 ms, p = 0,03) and P-wave dispersion values (42,1 ± 11 ms vs. 29,1± 4,2 ms, p = 0,003), compared to APP ON group (Fig. 2). No statistically significant difference was found in heart rate (79,5 ± 6,3 bpm vs. 80,8 ± 5,4 bpm, p = 0,3) and minimum P-wave duration (73,7 ± 11.8 ms vs. 69,4 ± 8.1 ms, p = 0,4). All data are shown in Table 3. We found a significant positive correlation between PD and AF burden (R = 0,8, p = 0.007) (Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

Difference in P-wave dispersion between APP ON Group and APP OFF Group (29,1± 4,2 ms vs. 42,1 ± 11 ms, p = 0,003).

Table 3.

Differences in electrocardiographic findings between the two groups.

| APP ON Group | APP OFF Group | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heart rate (bpm) | 80,8 ± 5,4 | 79,5 ± 6,3 | 0,3 |

| Max P-wave duration (ms) | 69,8 ± 8,2 | 109,4 ± 10,9 | 0,03 |

| Min P-wave duration (ms) | 69,4 ± 8,1 | 73,7 ± 11,8 | 0,4 |

| P-wave dispersion (ms) | 29,1 ± 4,2 | 42,1 ± 11 | 0,003 |

Figure 3.

Correlation between P-wave dispersion and atrial fibrillation burden in DM1 patients (R = 0,8, p = 0.007).

Discussion

Non invasive electrocardiographic risk indexes

QTc dispersion (QTcD) and JTc dispersion (JTcD) have been proposed as non invasive methods to measure the heterogeneity of ventricular repolarization (16). Increased dispersion of ventricular repolarization is considered to provide an electrophysiological substrate for life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias in several clinical conditions such as dilated cardiomyopathy (17, 18), obesity (19, 20), congenital disease (21, 22), beta thalassemia major (23) and cardiomyopathies (1-4, 24- 26).

P-wave dispersion is a non invasive indicator of intra- atrial conduction heterogeneity producing substrate for reentry, which is a pathophysiological mechanism of atrial fibrillation. PD has been evaluated in some clinical conditions such as obesity (27), beta-thalassemia major (28, 29), Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy (30). In a recent study (31), we showed a statistically significant increase in PD and P max in DM1 patients with AF compared to DM1 patients with no arrhythmias, confirming that P-wave dispersion may be a simple electrocardiographic parameter for identify high risk atrial fibrillation in DM1 patients.

Heart Rate Variability (HRV) is a reliable index to asses sympathovagal balance, used to stratify arrhythmic risk in several clinical conditions (32-39) and cardiomyopathies (40-42). However previous studies on autonomic modulation of heart rate in DM1 patients have obtained conflicting results (43-45).

Pacing in DM1 Patients

We have previously shown that: a) AF episodes increase in DM1 patients with a high percentage of right ventricular pacing and a lower percentage of atrial stimulation (46); b) right atrial septal stimulation in the Bachmann's bundle region is a safe and feasible procedure (47), with less atrial pacing and sensing defects than the right atrial appendage stimulation (48), though it does not seem to provide significant benefits for prevention of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (49).

Atrial preference pacing algorithm may prevent the onset of atrial fibrillation through the following mechanisms: a) prevention of the relative bradycardia that triggers paroxysmal AF; b) prevention of the bradycardiainduced dispersion of refractoriness; c) suppression or reduction of premature atrial contractions that initiate the re-entry and predispose to AF; and d) preservation of atrio-ventricular synchrony, which may prevent switchinduced changes in atrial repolarization, predisposing to AF. According to our previous studies, the APP is an efficient algorithm for preventing AF episodes (50-52) and for reducing AT/AF burden in DM1 patients implanted with dual-chamber pacemaker.

Main findings

The current study investigated the effect of atrial preference pacing (APP) on AF burden in a three year follow-up period and the possible correlation between P-wave dispersion and AF burden, in myotonic dystrophy type 1 patients with conserved systolic and diastolic function who underwent dual chamber pacemaker implantation. Our data demonstrate that atrial preference pacing algorithm significantly reduces the number and the mean duration of AF episodes and AF burden and decreases the P-wave duration and dispersion in DM1 patients. Our results showed that P-wave dispersion is significantly higher in DM1 patients with increased AF burden. Therefore, we suggest that PD is an important factor affecting AF burden and that atrial preference pacing is responsible of AF burden reduction, through two mechanisms: reduction of premature atrial contractions and prevention of the bradycardia-induced dispersion of refractoriness.

Limitation of study

PD reflects only the intra-atrial conduction heterogeneity, but it not provides other atrial electrophysiological properties. Errors in PD measurement done with manual evaluation, may be a potential bias for observed conflicting results. However according to Dilaveris et al. (10), scanning and digitizing ECG signals from paper records using an optical scanner, is a feasible and accurate method for measuring P-wave duration.

Conclusions

Our study supports the hypothesis that the intra-atrial conduction heterogeneity, assessed by P-wave dispersion measurement, plays an important role in the AF initiation and perpetuation in DM1 patients with normal cardiac function. Atrial preference pacing algorithm, decreasing the number of atrial premature beats and the P-wave dispersion, reduces the onset of AF episodes and decreases the AF burden in DM1 patients underwent dual-chamber pacemaker implantation.

References

- 1.Russo V, Rago A, D'Andrea A, et al. Early onset "electrical" heart failure in myotonic dystrophy type 1 patient: the role of ICD biventricular pacing. Anadolu Kardiyol Derg. 2012;12:517–519. doi: 10.5152/akd.2012.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nigro G, Russo V, Rago A, et al. Regional and transmural dispersion of repolarisation in patients with Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy. Kardiol Pol. 2012;70:1154–1159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nigro G, Russo V, Ventriglia VM, et al. Early onset of cardiomyopathy and primary prevention of sudden death in X-linked Emery Dreifuss muscular dystrophy. Neuromuscul Disord. 2010;20:174–177. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Russo V, Rago A, Antonio Papa A. Cardiac resynchronization improves heart failure in one patient with Myotonic Dystrophy type 1. A case report. Acta Myol. 2012;31:154–155. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rotundo IL, Faraso S, Leonibus E, et al. Worsening of cardiomyopathy using deflazacort in an animal model rescued by gene therapy. PLoS One. 2011;6:e24729–e24729. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lancioni A, Rotundo IL, Kobayashi YM, et al. Combined deficiency of alpha and epsilon sarcoglycan disrupts the cardiac dystrophin complex. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:4644–4654. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nigro G, Papa AA, Politano L. The heart and cardiac pacing in Steinert disease. Acta Myol. 2012;31:110–116. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nguyen HH, Wolfe JT, III, Holmes DR, Jr, et al. Pathology of the cardiac conduction system in myotonic dystrophy: a study of 12 cases. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1988;11:662–671. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(88)91547-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Russo AD, Mangiola F, Della Bella P, et al. Risk of arrhythmias in myotonic dystrophy: trial design of the RAMYD study. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2009;10:51–58. doi: 10.2459/jcm.0b013e328319bd2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dilaveris P, Gialafos EJ, Sideris SK, et al. Simple electrocardiographic markers for the prediction of paroxysmal idiopathic atrial fibrillation. Am Heart J. 1998;135:733–738. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(98)70030-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Platonov PG, Carlson J, Ingemansson MP, et al. Detection of inter-atrial conduction defects with unfiltered signal-averaged P-wave ECG in patients with lone atrial fibrillation. Europace. 2000;2:32–41. doi: 10.1053/eupc.1999.0072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Russo V, Nigro G, Rago A, et al. Atrial fibrillation burden in Myotonic Dystrophy type 1 patients implanted with dual chamber pacemaker: the efficacy of the overdrive atrial algorithm at 2 year follow-up. Acta Myol. 2013;32:142–147. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Russo V, Rago A, Politano L, et al. The effect of atrial preference pacing on paroxysmal atrial fibrillation incidence in myotonic dystrophy type 1 patients: a prospective, randomized, single-bind cross-over study. Europace. 2012;14:486–489. doi: 10.1093/europace/eur373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nigro G, Russo V, Rago A, et al. Right atrial preference pacing algorithm in the prevention of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation in myotonic dystrophy type 1 patients: a long term follow-up study. Acta Myol. 2012;31:139–143. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Platonov PG, Carlson J, Ingemansson MP, et al. Detection of inter-atrial conduction defects with unfiltered signal-averaged P-wave ECG in patients with lone atrial fibrillation. Europace. 2000;2:32–41. doi: 10.1053/eupc.1999.0072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuo CS, Munakata K, Reddy CP, et al. Characteristics and possible mechanisms of ventricular arrhythmia dependent on the dispersion of action potential durations. Circulation. 1983;67:1356–1357. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.67.6.1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Santangelo L, Ammendola E, Russo V, et al. Influence of biventricular pacing on myocardial dispersion of repolarization in dilated cardiomyopathy patients. Europace. 2006;8:502–505. doi: 10.1093/europace/eul054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Santangelo L, Russo V, Ammendola E, et al. Biventricular pacing and heterogeneity of ventricular repolarization in heart failure patients. Heart Int. 2006;2:27–27. doi: 10.4081/hi.2006.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Russo V, Ammendola E, Crescenzo I, et al. Effect of weight loss following bariatric surgery on myocardial dispersion of repolarization in morbidly obese patients. Obes Surg. 2007;17:857–865. doi: 10.1007/s11695-007-9160-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nigro G, Russo V, Salvo G, et al. Increased heterogenity of ventricular repolarization in obese nonhypertensive children. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2010;33:1533–1539. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2010.02889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nigro G, Russo V, Rago A, et al. Heterogeneity of ventricular repolarization in newborns with severe aortic coarctation. Pediatr Cardiol. 2012;33:302–306. doi: 10.1007/s00246-011-0132-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nigro G, Russo V, Rago A, et al. The effect of aortic coarctation surgical repair on QTc and JTc dispersion in severe aortic coarctation newborns: a short-term follow-up study. Physiol Res. 2014;63:27–33. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.932491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Russo V, Rago A, Pannone B, et al. Dispersion of repolarization and beta-thalassemia major: the prognostic role of QT and JT dispersion for identifying the high-risk patients for sudden death. Eur J Haematol. 2011;86:324–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2011.01579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Russo V, Rago A, Politano L, et al. Increased dispersion of ventricular repolarization in Emery Dreifuss muscular dystrophy patients. Med Sci Monit. 2012;18:CR643–CR647. doi: 10.12659/MSM.883541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Russo V, Nigro G. ICD role in preventing sudden cardiac death in Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy with preserved myocardial function: 2013 ESC Guidelines on Cardiac Pacing and Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy. Europace. 2015;17:337–337. doi: 10.1093/europace/euu146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.D'Andrea A, Salerno G, Scarafile R, et al. Right ventricular myocardial function in patients with either idiopathic or ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy without clinical sign of right heart failure: effects of cardiac resynchronization therapy. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2009;32:1017–1029. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2009.02434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Russo V, Ammendola E, Crescenzo I, et al. Severe obesity and P-wave dispersion: the effect of surgically induced weight loss. Obes Surg. 2008;18:90–96. doi: 10.1007/s11695-007-9340-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Russo V, Rago A, Pannone B, et al. Early electrocardiographic evaluation of atrial fibrillation risk in beta-thalassemia major patients. Int J Hematol. 2011;93:446–451. doi: 10.1007/s12185-011-0801-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Russo V, Rago A, Pannone B, et al. Atrial fibrillation and beta thalassemia major: the predictive role of the 12-lead electrocardiogram analysis. Indian Pacing Electrophysiol J. 2014;14:121–132. doi: 10.1016/s0972-6292(16)30753-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Russo V, Rago A, Palladino A, et al. P-wave duration and dispersion in patients with Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy. J Investig Med. 2011;59:1151–1154. doi: 10.2310/JIM.0b013e31822cf97a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Russo V, Meo F, Rago A, et al. Paroxysmal atrial fibrillation in myotonic dystrophy type 1 patients: P-wave duration and dispersion analysis. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2015 (in press) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nigro G, Russo V, Chiara A, et al. Autonomic nervous system modulation before the onset of sustained atrioventricular nodal reentry tachycardia. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2010;15:49–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-474X.2009.00339.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Russo V, Crescenzo I, Ammendola E, et al. Sympathovagal balance analysis in idiopathic postural orthostatic tachycardia sindrome. Acta Biomedica Athenensis Parmensis. 2007;78:133–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Russo V, Nigro G, Calabrò R. Heart rate variability, obesity and bariatric induced weight loss: the importance of selection criteria. Metabolism. 2008;57:1622–1624. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Russo V, Nigro G, Chiara A, et al. The impact of selection criteria of obese patients on evaluation of heart rate variability following bariatric surgery weight loss. Letter to Editor. Obesi Surg. 2009;19:397–398. doi: 10.1007/s11695-008-9784-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Russo V, Crescenzo I, Ammendola I, et al. Sympathovagal balance analysis in idiopathic postural orthostatic tachycardia sindrome. Acta Biomedica Athenensis Parmensis. 2007;78:133–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nigro G, Russo V, Rago A, et al. The main determinant of hypotension in nitroglycerin tilt-induced vasovagal syncope. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2012;35:739–748. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2012.03388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Russo V, Rago A, Papa AA, et al. The effect of dual-chamber closed-loop stimulation on syncope recurrence in healthy patients with tilt-induced vasovagal cardioinhibitory syncope: a prospective, randomised, single-blind, crossover study. Heart. 2013;99:1609–1613. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2013-303878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Russo V, Crescenzo I, Ammendola E, et al. Heart rate variability analysis in postural orthostatic tachicardia syndrome: a case report. Heart Int. 2006;2:126–126. doi: 10.4081/hi.2006.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ammendola E, Russo V, Politano L, et al. Is heart rate variability (HRV) a valid parameter to predict sudden death in Becker muscular dystrophy patients? Heart. 2006;92:1686–1687. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.082909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ducceschi V, Nigro G, Sarubbi B, et al. Autonomic nervous system imbalance and left ventricular systolic dysfunction as potential candidates for arrhythmogenesis in Becker muscular dystrophy. Intern J Cardiol. 1997;59:275–279. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(97)02933-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Politano L, Palladino A, Nigro G, et al. Usefulness of heart rate variability as a predictor of sudden cardiac death in muscular dystrophies. Acta Myol. 2008;27:114–122. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Inoue K, Ogata H, Matsui M, et al. Assessment of autonomic function in myotonic dystrophy by spectral analysis of heart-rate variability. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1995;55:131–134. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(95)00040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hardin BA, Lowe MR, Bhakta D, et al. Heart rate variability declines with increasing age and CTG repeat length in patients with myotonic dystrophy type 1. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2003;8:227–232. doi: 10.1046/j.1542-474X.2003.08310.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leo R, Rodolico C, Gregorio C, et al. Cardiovascular autonomic control in myotonic dystrophy type 1: a correlative study with clinical and genetic data. Neuromuscul Disord. 2004;14:136–141. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2003.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Russo V, Rago A, Papa AA, et al. Does a high percentage of right ventricular pacing influence the incidence of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation in myotonic dystrophy type 1 patients? Kardiol Pol. 2013;71:1147–1153. doi: 10.5603/KP.2013.0295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nigro G, Russo V, Vergara P, et al. Optimal site for atrial lead implantation in myotonic dystrophy patients The role of Bachmann's Bundle stimulation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2008;31:1463–1466. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2008.01210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nigro G, Russo V, Politano L, et al. Right atrial appendage versus Bachmann's bundle stimulation: a two year comparative study of electrical parameters in myotonic dystrophy type 1 patients. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2009;32:1192–1197. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2009.02464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nigro G, Russo V, Politano L, et al. Does Bachmann's bundle pacing prevent atrial fibrillation in myotonic dystrophy type 1 patients? A 12 months follow-up study. Europace. 2010;12:1219–1223. doi: 10.1093/europace/euq170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Russo V, Rago A, Politano L, et al. The effect of atrial preference pacing on paroxysmal atrial fibrillation incidence in myotonic dystrophy type 1 patients: a prospective, randomized, single-bind cross over study. Europace. 2012;14:486–489. doi: 10.1093/europace/eur373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nigro G, Russo V, Rago A, et al. Right atrial preference pacing algorithm in the prevention of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation in myotonic dystrophy type 1 patients: a long term follow-up study. Acta Myol. 2012;31:139–143. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Russo V, Nigro G, Rago A, et al. Atrial fibrillation burden in Myotonic Dystrophy type 1 patients implanted with dual chamber pacemaker: the efficacy of the overdrive atrial algorithm at 2 year follow-up. Acta Myol. 2013;32:142–147. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]