Abstract

Background

This study aimed to determine the number of people living with HIV receiving antiretroviral therapy (ART) between 2006 and 2013 in Germany by using the available numbers of antiretroviral drug prescriptions and treatment data from the ClinSurv HIV cohort (CSH).

Methods

The CSH is a multi-centre, open, long-term observational cohort study with an average number of 10.400 patients in the study period 2006–2013. ART has been documented on average for 86% of those CSH patients and medication history is well documented in the CSH.

The antiretroviral prescription data (APD) are reported by billing centres for pharmacies covering >99% of nationwide pharmacy sales of all individuals with statutory health insurance (SHI) in Germany (~85%). Exactly one thiacytidine-containing medication (TCM) with either emtricitabine or lamivudine is present in all antiretroviral fixed-dose combinations (FDCs). Thus, each daily dose of TCM documented in the APD is presumed to be representative of one person per day receiving ART. The proportion of non-TCM regimen days in the CSH was used to determine the corresponding number of individuals in the APD.

Results

The proportion of CSH patients receiving TCMs increased continuously over time (from 85% to 93%; 2006–2013). In contrast, treatment interruptions declined remarkably (from 11% to 2%; 2006–2013). The total number of HIV-infected people with ART experience in Germany increased from 31,500 (95% CI 31,000-32,000) individuals to 54,000 (95% CI 53,000-55,500) over the observation period (including 16.3% without SHI and persons who had interrupted ART). An average increase of approximately 2,900 persons receiving ART was observed annually in Germany.

Conclusions

A substantial increase in the number of people receiving ART was observed from 2006 to 2013 in Germany.

Currently, the majority (93%) of antiretroviral regimens in the CSH included TCMs with ongoing use of FDCs. Based on these results, the future number of people receiving ART could be estimated by exclusively using TCM prescriptions, assuming that treatment guidelines will not change with respect to TCM use in ART regimens.

Keywords: HIV treatment, Composition of ART regimen, Antiretroviral drug classes, Health market research

Background

Combined antiretroviral therapy (ART) as a standard of care has dramatically reduced mortality and morbidity and has led to an enormous increase in quality of life among people infected with HIV [1,2]. In most patients who receive ART, progression to AIDS or death is increasingly rare [3-5], and their life expectancies have significantly improved [6-8]. However, ART is a complex and lifelong therapy that must be well monitored, coordinated and tracked. Although ART is still not available for a large number of people in need, especially in developing countries [9], the number of people living with HIV who are receiving treatment is increasing worldwide [9]. In industrialised countries, a large number of people living with HIV are under treatment [10]. As HIV has become a chronic disease, an increasing number of people must be treated for decades, making it an important economic and public health issue to gain information on this group. Information on the current number of people living with HIV receiving ART in Germany is scarce owing to a lack of data, and access to personal-level drug prescription data is forbidden because of data protection.

HIV treatment in Germany is characterized by a decentralised structure. Medical care is mainly provided by specialized outpatient centres and office-based HIV specialists, and unlike in many countries people can consult a doctor of their own choice at any time and anywhere in the country. Furthermore, health care in Germany is compulsory for all German citizens and legal residents and is mostly provided by statutory health insurance (SHI) or private health insurance (PHI) [11-13]. SHI occupies a central position in the German health care system. Approximately 85% of German residents are covered by SHI, and nearly 60% of the total health expenditures are borne by SHI [12]. SHI reimburses pharmacies for the prescriptions of those who are covered via specialised pharmacy billing centres. Therefore, the prescription details are electronically recorded. The recording and use of these data are regulated by the social security law (§300 SGB V). Data from health services research such as electronically recorded pharmacy data are being increasingly used for research in Germany. Nevertheless, public health studies using data representing nearly all persons covered by SHI are scarce.

The prescription data include all antiretroviral drugs, regardless of whether they are for permanent or short-term therapies, e.g., post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP). No individual information and, therefore no indications, are available. In contrast, the prospective multi-centre observational German ClinSurv HIV cohort (CSH) ongoing since 1999 is the largest available nationwide source of people infected with HIV and collects detailed information on the initiation, composition and discontinuation of individuals’ daily ART from their participating centres [14].

Since the approval of the first antiretroviral agent, at least in the industrialised world, more than 30 antiretroviral pharmaceuticals, either single-drug formulations or fixed-dose combinations, are available for the treatment of HIV infection [15]. Nucleoside/nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) are still the main components of antiretroviral drug combinations [16] and are recommended as an element of any first-line antiretroviral regimen by therapy guidelines [17-19]. Currently, a combination of three antiretroviral drug classes consisting of two NRTIs and a third agent, either a protease inhibitor (PI) or a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) or an integrase inhibitor (INI), is recommended for first-line therapy [17,18]. During the last decade, it has been recommended that all first-line NRTI combinations contain an element of a thiacytidine medication (TCM), either lamivudine (3TC) or emtricitabine (FTC) [17,19,20]. The two medications are interchangeable, but because of their high antiretroviral similarity with no additional effects, concomitant use should be avoided [17]. NRTI-free regimen such as PI monotherapy are not recommended because of inferior antiviral potency [17,18,21-23]. Because standard ART consists of a combination of at least three antiretroviral drugs given in a multitude of combination regimens, it is impossible to estimate the number of people receiving ART prescriptions based on all single drugs [24]. However, virtually all ART regimens prescribed in different studies in a setting of daily clinical practice contain exactly one TCM [25-33]. Thus, each daily TCM documented in the APD may be assumed to be representative of one person per day treated with ART. It was hypothesised that the ART regimens and treatment interruptions recorded in the CSH were representative of people living with HIV under antiretroviral treatment in Germany and that the prescriptions covered by SHI were comparable with those that were not.

This study used available prescription data sources from both pharmacy billing centres and the CSH to determine the number of people living with HIV currently receiving ART, the number of HIV-infected people with ART experience, and the differences in those numbers over time between 2006 and 2013.

Methods

Data sources used for analysis

ART prescription data (APD)

ART prescription data were provided by Insight Health™ for the years 2006–2013. The data were collected on a monthly basis from billing centres that processed all reimbursed prescriptions from pharmacies based on the date of redemption at the counter. The provider claimed a coverage of >99% within the SHI prescription market. The recorded numbers of prescribed standard units (i.e., numbers of tablets) of each antiretroviral drug were used for this study.

Defined daily doses (DDDs) were determined as recommended in the treatment guidelines [17]. The number of prescribed DDDs was calculated for TCMs depending on the doses of standard units. According to our approach, a DDD that included a TCM represented one person-day, assuming that one person was treated with TCM continuously every day for a quarter, as is recommended by treatment guidelines. In the case of the prescription of a 150 mg dose of lamivudine, 2 tablets were equivalent to one DDD.

The German ClinSurv HIV cohort (CSH)

The Clinical Surveillance of HIV Disease is a nationwide multi-centre, open, long-term observational cohort study for the clinical surveillance of HIV in Germany. The CSH was initiated in 1999 as collaboration between major HIV treatment centres and the Robert Koch Institute (RKI) which serves as the coordinating institution. Anonymised data on patient demographics, detailed information on antiretroviral treatment, laboratory parameters and clinical events are collected biannually in a standardised format. The study design is described in detail elsewhere [14]. In the study period 2006–2013, an average number of 10.400 patients were observed and consecutively monitored at 15 clinical centres in various, predominantly urban areas in Germany. Antiretroviral treatment history, including any interruptions in treatment, is documented in detail in the CSH [14,24]. Treatment duration is calculated individually according to the beginning and end dates of each antiretroviral drug treatment. All ART documentation is assessed manually. Quality control algorithms are applied, and in the case of inconsistencies, the centres are requested to submit the revised data to the RKI [14].

The Robert Koch Institute is the German national public health institute, therefore the Federal Commissioner for Data Protection is the responsible entity for studies which are conducted by the Robert Koch Institute. Information on HIV infection collected in ClinSurv corresponds to the data reported to the RKI according to legal requirements implemented by the national Protection against Infection act (IfSG) of 2001. All patient data collected in ClinSurv are generated during routine care. The German Federal Commissioner for Data Protection therefore waived the need for ethical approval for the ClinSurv study. No written informed consent is required from patients.

The overall person-days observed from persons receiving any antiretroviral treatment between 2006 and 2013 in the CSH were analysed and categorised into three groups: medications that contained approved drugs, medications that contained at least one non-approved drug, and interrupted therapy. In the first group, we distinguished between regimens that did include a TCM and those without TCM. The numbers of all of these groups were calculated quarterly. Treatment interruption was defined as any observation time between therapy initiation and latest observed event with documented treatment discontinuation.

For the analysis of ART regimen in the CSH we separated mainly used regimens and minor regimens. Mainly used regimens were either defined as ART regimen containing two or three NRTIs and another drug class (NNRTIs, PIs, INIs) or two or three NRTIs exclusively. Minor regimens were those including more than three NRTIs and NRTI-free regimen.

Combination of data sources

Determining the number of people living with HIV receiving ART

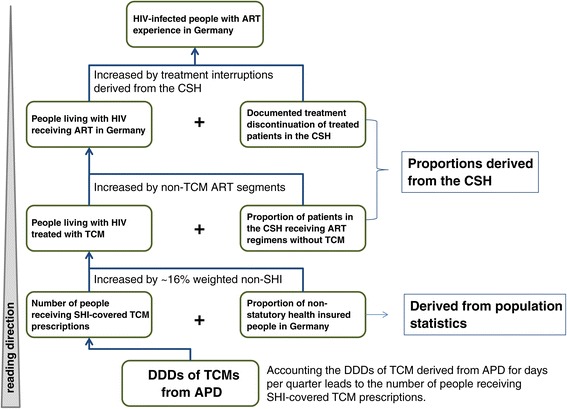

The number of prescribed DDDs of TCMs derived from ART prescription data was used to determine the number of people living with HIV receiving quarterly SHI-covered TCM containing ART in Germany. The proportion of persons covered by SHI was calculated for each federal state based on the number of persons with SHI and the population number of the respective state. To account for patients without SHI (including those privately insured, uninsured, or receiving free medical care) whose prescriptions were not covered in the APD, the number of patients was raised in average by a weighted factor of 16.3% [34]. By adding the numbers of person-days of non-TCM ART segments derived from the CSH, we determined the total number of people living with HIV receiving quarterly ART in Germany. In addition, considering the proportion of person-days with treatment interruption seen in the CSH yielded the number of patients in Germany with ART experience. For an overview of the investigated data sources, see Figures 1 and 2.

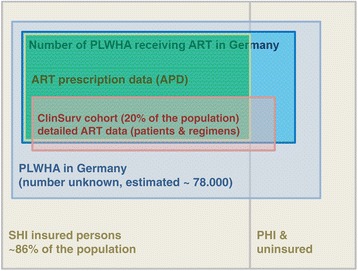

Figure 1.

Schematic overview of subpopulations and available data sources in Germany. Approximately 85% of the population in Germany is covered by statutory health insurance (SHI), most of the remainder are covered by private health insurance (PHI) and a small proportion are uninsured (exact number unknown). For persons covered by the SHI, antiretroviral prescriptions are recorded and reported through antiretroviral prescription data (APD). The German ClinSurv HIV cohort (CSH) contains detailed ART history data on approximately 20% of people living with HIV in Germany receiving ART, both those who are covered by SHI and those who are not. This schematic is not to scale.

Figure 2.

Process diagram of used data sources and calculation steps proceeded.

The estimated number of HIV-infected persons with ART experience was smoothed using a negative binomial regression with quadratic time trend in the period of 2006 to 2013. The statistical errors of these numbers were assumed to be independent. The independent variables considered in the negative binomial regression were the time - measured in quarters since the first quarter in year 2006 - and the square of this time. The latter variable allowed us to adjust for a slowing down of the exponentially increasing trend in the recent years.

Results

ClinSurv HIV cohort (CSH)

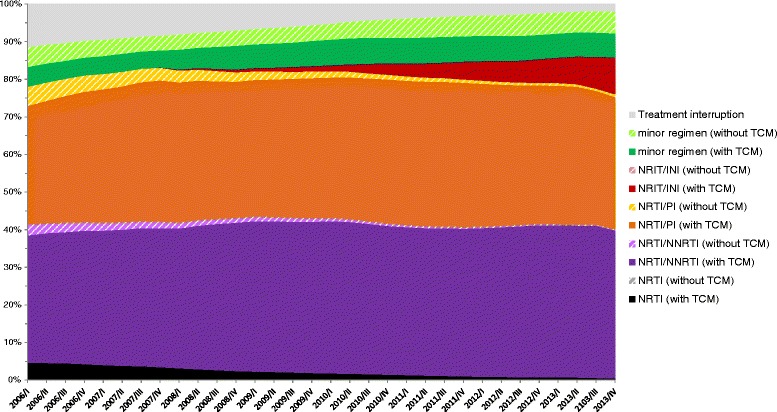

The proportion of person-days with TCM-containing regimens reported in the CSH increased continuously over the study period, from 85% in 2006/I to 93% in 2013/IV. In contrast, the proportion of person-days with any observed treatment interruption declined from 11% in 2006/I to 2% in 2013/IV. The proportion of person-days with an antiretroviral regimen that contained non-approved drugs decreased from 6% in 2006/I to 2% in 2013/IV (Table 1).

Table 1.

The German ClinSurv HIV cohort in the study period 2006–2013

| Year/quarter | Patients under observation | Patients under ART time | Observation time | Time under ART or interruption | ART status unknown | Art naive | ART regimens with approved drugs exclusively | ART regimens containing non-approved drugs | Treatment interruptions | ART experienced | TCMs in the CSH | Proportion of interruptions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Days | |||||||||||

| 2006/I | 8717 | 6986 | 753553 | 613673 | 8211 | 131728 | 516827 | 29909 | 66937 | 81.4% | 84.5% | 10.9% |

| 2006/II | 8856 | 7104 | 773115 | 630625 | 7907 | 134629 | 533732 | 32431 | 64462 | 81.6% | 85.3% | 10.2% |

| 2006/III | 9002 | 7214 | 792169 | 646716 | 7742 | 137766 | 547485 | 36102 | 63129 | 81.6% | 86.2% | 9.8% |

| 2006/IV | 9075 | 7281 | 803312 | 655415 | 7530 | 140415 | 558719 | 36453 | 60243 | 81.6% | 87.0% | 9.2% |

| 2007/I | 9267 | 7434 | 798257 | 652832 | 7219 | 138281 | 560733 | 33462 | 58637 | 81.8% | 87.7% | 9.0% |

| 2007/II | 9407 | 7552 | 820040 | 671081 | 7345 | 141682 | 579930 | 33382 | 57769 | 81.8% | 88.4% | 8.6% |

| 2007/III | 9564 | 7689 | 844690 | 690514 | 7304 | 146945 | 595635 | 38313 | 56566 | 81.7% | 89.1% | 8.2% |

| 2007/IV | 9683 | 7828 | 855138 | 704369 | 6948 | 143877 | 609239 | 39403 | 55727 | 82.4% | 89.5% | 7.9% |

| 2008/I | 9758 | 7937 | 853480 | 705518 | 6344 | 141676 | 619880 | 31297 | 54341 | 82.7% | 89.8% | 7.7% |

| 2008/II | 9903 | 8069 | 863850 | 716324 | 5985 | 141595 | 632750 | 31325 | 52249 | 82.9% | 90.4% | 7.3% |

| 2008/III | 10031 | 8206 | 884551 | 737289 | 5895 | 141423 | 656479 | 28383 | 52427 | 83.4% | 90.7% | 7.1% |

| 2008/IV | 10124 | 8340 | 896771 | 752357 | 5982 | 138495 | 678973 | 22195 | 51189 | 83.9% | 91.0% | 6.8% |

| 2009/I | 10222 | 8484 | 886182 | 747140 | 5303 | 133792 | 677700 | 21820 | 47620 | 84.3% | 91.3% | 6.4% |

| 2009/II | 10384 | 8624 | 910943 | 769502 | 4859 | 136659 | 700526 | 21972 | 47004 | 84.5% | 91.6% | 6.1% |

| 2009/III | 10569 | 8814 | 934456 | 791390 | 4779 | 138362 | 722970 | 22322 | 46098 | 84.7% | 91.8% | 5.8% |

| 2009/IV | 10697 | 8989 | 946177 | 808947 | 4660 | 132635 | 742278 | 22853 | 43816 | 85.5% | 92.0% | 5.4% |

| 2010/I | 10799 | 9140 | 936276 | 805104 | 4473 | 126765 | 741693 | 22313 | 41098 | 86.0% | 92.3% | 5.1% |

| 2010/II | 10956 | 9290 | 958828 | 827947 | 4376 | 126573 | 768583 | 21791 | 37573 | 86.3% | 92.4% | 4.5% |

| 2010/III | 11123 | 9468 | 980925 | 849665 | 4289 | 127041 | 792663 | 21195 | 35807 | 86.6% | 92.4% | 4.2% |

| 2010/IV | 11171 | 9617 | 989771 | 865271 | 3898 | 120674 | 808229 | 22985 | 34057 | 87.4% | 92.3% | 3.9% |

| 2011/I | 11258 | 9761 | 974608 | 859468 | 3418 | 111790 | 803378 | 24123 | 31967 | 88.2% | 92.3% | 3.7% |

| 2011/II | 11333 | 9870 | 994656 | 880602 | 3347 | 110776 | 824465 | 25470 | 30667 | 88.5% | 92.3% | 3.5% |

| 2011/III | 11467 | 10030 | 1013429 | 901100 | 3305 | 109118 | 845603 | 26049 | 29448 | 88.9% | 92.4% | 3.3% |

| 2011/IV | 11480 | 10089 | 1021398 | 910156 | 3063 | 108245 | 857736 | 24301 | 28119 | 89.1% | 92.5% | 3.1% |

| 2012/I | 11588 | 10196 | 1014121 | 906295 | 3068 | 104831 | 858296 | 21730 | 26269 | 89.4% | 92.6% | 2.9% |

| 2012/II | 11612 | 10261 | 1019125 | 914177 | 2916 | 102114 | 867192 | 20862 | 26123 | 89.7% | 92.6% | 2.9% |

| 2012/III | 11651 | 10338 | 1032814 | 929619 | 2661 | 100626 | 883234 | 21460 | 24925 | 90.0% | 92.4% | 2.7% |

| 2012/IV | 11574 | 10334 | 1023954 | 925347 | 2423 | 96245 | 882817 | 20421 | 22109 | 90.4% | 92.5% | 2.4% |

| 2013/I | 11428 | 10229 | 980141 | 890397 | 2109 | 87707 | 852262 | 18571 | 19564 | 90.8% | 92.7% | 2.2% |

| 2013/II | 11092 | 9978 | 960764 | 876969 | 1508 | 82345 | 843148 | 16594 | 17227 | 91.3% | 92.8% | 2.0% |

| 2103/III | 10760 | 9725 | 879002 | 804520 | 1199 | 73313 | 775500 | 14296 | 14724 | 91.5% | 92.7% | 1.8% |

| 2013/IV | 8358 | 7610 | 363973 | 331301 | 621 | 31848 | 317585 | 7227 | 6489 | 91.0% | 92.5% | 2.0% |

Determined patient numbers, observation time and proportions of treated patients as well as TCM use and treatment interruptions in the ClinSurv HIV cohort.

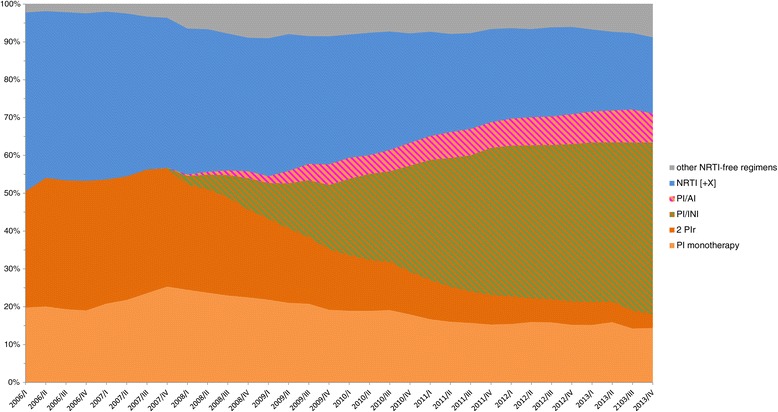

The exact composition of ART regimens of the CSH is shown in Figure 3. The proportion of non-TCM regimen among NRTI/NNRTI and NRTI/PI dramatically decreased over the study period. Non-TCM regimens were most frequently observed among minor regimen which was the only group with a slight increase of only 1% over the study period. The differentiated analyses of the group minor regimens without TCM showed that over the study period, the proportion of any non-TCM-NRTI containing regimen (TCM-NRTI [+X]) as well as the proportion of regimens consisting of two PIs or PI monotherapy decreased, whereas the dual combinations PI/AI, PI/II and other NRTI-free regimens increased continuously from 2007 to 2013 (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Composition of ART regimens of patients in the ClinSurv HIV cohort.

Figure 4.

Composition of minor non-TCM containing ART regimens of patients in the ClinSurv HIV cohort.

Antiretroviral prescription data (APD)

The number of TCM-containing prescriptions increased from 1,778,070 prescribed DDDs in 2006/I to 3,838,620 prescribed DDDs in 2013/IV.

Taking into account the number of days per quarter led to the number of patients receiving SHI covered TCM containing ART. We observed a systematic seasonal variation, with a disproportionately high number of prescriptions in the last quarter of each year. The number of patients receiving SHI covered TCM-containing ART increased from 19,756 persons in 2006/I to 41,724 persons in 2013/IV. The proportion of persons covered by SHI was different in the respective federal states and ranged from approximately 80% to 90%. The weighted proportion of persons covered by SHI used for the calculation was on average 83.7% over the study period (Table 2).

Table 2.

German population, SHI coverage and calculated weighted SHI-coverage factor

| Year/quarter | German population | Number of people in SHI | SHI-coverage nationwide | Weighted SHI-coverage factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006/I | 82314906 | 70013157 | 85.1% | 83.2% |

| 2007/I | 82217837 | 70022112 | 85.2% | 83.5% |

| 2008/I | 82002356 | 69952132 | 85.3% | 83.4% |

| 2009/I | 81802257 | 69719142 | 85.2% | 84.1% |

| 2010/I | 81751602 | 69473638 | 85.0% | 84.3% |

| 2011/I | 81843743 | 69311329 | 84.7% | 83.3% |

| 2012/I | 81843743* | 69398840 | 84.8% | 83.9% |

| 2013/I | 81843743* | 69521912 | 84.9% | 84.0% |

*updated data for 2012 and 2013 not available yet.

Determining the number of people living with HIV receiving ART

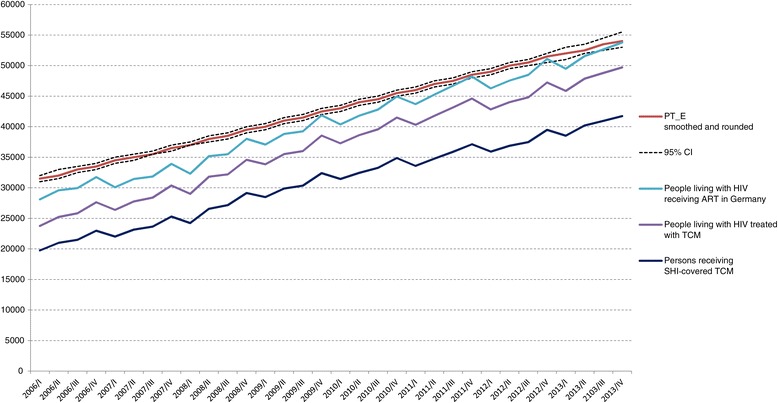

After accounting for patients without SHI by adding 16.3% to the patient numbers derived from APD, the numbers of people living with HIV receiving TCM-containing ART in Germany were 23,751 in 2006/I and increased to 49,719 in 2013/IV. By compensating for regimens not containing TCMs, the number of all people living with HIV receiving ART was estimated at 28,101 in 2006/I and increased continuously to 53,776 in 2013/V. Taking into account those who had interrupted therapy led to the total number of HIV-infected people with ART experience in Germany. Due to the observed seasonal variation, we smoothed the trend by using a negative binomial regression with quadratic time trend. The total number of all HIV-infected people with ART experience in Germany increased from 31,500 (95% CI 31,000-32,000) in the first quarter of 2006 to 54,000 (95% CI 53,000-55,500) individuals by the end of 2013 (Table 3 and Figure 5). The average difference between the number of patients in Germany who had initiated ART and those who had left observation because of emigration or death was estimated to be an average of 2,900 persons per year.

Table 3.

Step by step calculated data underlying the estimation of the number of people living with HIV receiving ART in Germany, 2006 to 2013

| Year/quarter | Days per quarter | DDDs of TCM from APD | Persons receiving SHI-covered TCM | Weighted SHI-coverage factor | People living with HIV treated with TCM | TCMs in the CSH | People living with HIV receiving ART in Germany | Proportion of interruptions in the CSH | HIV-infected people with ART experience in Germany (PT_E) | PT_E statistically smoothed | 95% CI | 95% CI | PT_E smoothed and rounded N (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006/I | 90 | 1778070 | 19756 | 83.2% | 23751 | 84.5% | 28101 | 10.9% | 31547 | 31505 | 30796 | 32229 | 31500 (31000-32000) |

| 2006/II | 91 | 1910070 | 20990 | 83.2% | 25222 | 85.3% | 29586 | 10.2% | 32953 | 32198 | 31559 | 32848 | 32000 (31500-33000) |

| 2006/III | 92 | 1975770 | 21476 | 83.1% | 25824 | 86.2% | 29960 | 9.8% | 33203 | 32896 | 32321 | 33480 | 33000 (32500-33500) |

| 2006/IV | 92 | 2114310 | 22982 | 83.1% | 27641 | 87.0% | 31757 | 9.2% | 34971 | 33600 | 33082 | 34125 | 33500 (33000-34000) |

| 2007/I | 90 | 1982490 | 22028 | 83.5% | 26385 | 87.7% | 30092 | 9.0% | 33064 | 34310 | 33838 | 34787 | 34500 (34000-35000) |

| 2007/II | 91 | 2106480 | 23148 | 83.3% | 27776 | 88.4% | 31434 | 8.6% | 34396 | 35024 | 34588 | 35465 | 35000 (34500-35500) |

| 2007/III | 92 | 2174850 | 23640 | 83.3% | 28383 | 89.1% | 31844 | 8.2% | 34687 | 35743 | 35330 | 36159 | 35500 (35500-36000) |

| 2007/IV | 92 | 2326950 | 25293 | 83.3% | 30377 | 89.5% | 33926 | 7.9% | 36841 | 36467 | 36066 | 36872 | 36500 (36000-37000) |

| 2008/I | 91 | 2204460 | 24225 | 83.4% | 29023 | 89.8% | 32312 | 7.7% | 35009 | 37195 | 36794 | 37600 | 37000 (37000-37500) |

| 2008/II | 91 | 2418270 | 26574 | 83.5% | 31814 | 90.4% | 35196 | 7.3% | 37964 | 37926 | 37516 | 38339 | 38000 (37500-38500) |

| 2008/III | 92 | 2498580 | 27158 | 84.3% | 32211 | 90.7% | 35508 | 7.1% | 38226 | 38661 | 38237 | 39089 | 38500 (38000-39000) |

| 2008/IV | 92 | 2680710 | 29138 | 84.2% | 34578 | 91.0% | 38009 | 6.8% | 40781 | 39399 | 38957 | 39845 | 39500 (39000-40000) |

| 2009/I | 90 | 2562540 | 28473 | 84.1% | 33844 | 91.3% | 37072 | 6.4% | 39595 | 40139 | 39678 | 40604 | 40000 (39500-40500) |

| 2009/II | 91 | 2719650 | 29886 | 84.1% | 35529 | 91.6% | 38809 | 6.1% | 41336 | 40882 | 40403 | 41366 | 41000 (40500-41500) |

| 2009/III | 92 | 2792580 | 30354 | 84.3% | 36015 | 91.8% | 39239 | 5.8% | 41667 | 41627 | 41132 | 42127 | 41500 (41000-42000) |

| 2009/IV | 92 | 2980560 | 32397 | 84.0% | 38544 | 92.0% | 41876 | 5.4% | 44274 | 42374 | 41866 | 42887 | 42500 (42000-43000) |

| 2010/I | 90 | 2829630 | 31440 | 84.3% | 37290 | 92.3% | 40385 | 5.1% | 42556 | 43121 | 42605 | 43643 | 43000 (42500-43500) |

| 2010/II | 91 | 2952420 | 32444 | 84.0% | 38619 | 92.4% | 41794 | 4.5% | 43783 | 43869 | 43348 | 44396 | 44000 (43500-44500) |

| 2010/III | 92 | 3060450 | 33266 | 84.1% | 39564 | 92.4% | 42800 | 4.2% | 44681 | 44618 | 44096 | 45146 | 44500 (44000-45000) |

| 2010/IV | 92 | 3208470 | 34875 | 84.0% | 41494 | 92.3% | 44947 | 3.9% | 46790 | 45367 | 44847 | 45892 | 45500 (45000-46000) |

| 2011/I | 90 | 3021690 | 33574 | 83.3% | 40316 | 92.3% | 43696 | 3.7% | 45388 | 46115 | 45599 | 46636 | 46000 (45500-46500) |

| 2011/II | 91 | 3162900 | 34757 | 83.2% | 41771 | 92.3% | 45256 | 3.5% | 46888 | 46862 | 46349 | 47379 | 47000 (46500-47500) |

| 2011/III | 92 | 3301830 | 35889 | 83.2% | 43160 | 92.4% | 46721 | 3.3% | 48301 | 47607 | 47095 | 48124 | 47500 (47000-48000) |

| 2011/IV | 92 | 3414960 | 37119 | 83.2% | 44619 | 92.5% | 48217 | 3.1% | 49756 | 48351 | 47832 | 48874 | 48500 (48000-49000) |

| 2012/I | 91 | 3268320 | 35916 | 83.9% | 42827 | 92.6% | 46271 | 2.9% | 47652 | 49092 | 48555 | 49634 | 49000 (48500-49500) |

| 2012/II | 91 | 3356700 | 36887 | 83.8% | 44007 | 92.6% | 47543 | 2.9% | 48944 | 49831 | 49260 | 50407 | 50000 (49500-50500) |

| 2012/III | 92 | 3447960 | 37478 | 83.6% | 44816 | 92.4% | 48483 | 2.7% | 49819 | 50566 | 49942 | 51197 | 50500 (50000-51000) |

| 2012/IV | 92 | 3632040 | 39479 | 83.6% | 47240 | 92.5% | 51089 | 2.4% | 52344 | 51298 | 50599 | 52006 | 51500 (50500-52000) |

| 2013/I | 90 | 3467760 | 38531 | 84.0% | 45861 | 92.7% | 49478 | 2.2% | 50591 | 52026 | 51230 | 52834 | 52000 (51000-53000) |

| 2013/II | 91 | 3657690 | 40194 | 84.0% | 47861 | 92.8% | 51555 | 2.0% | 52585 | 52748 | 51834 | 53677 | 52500 (52000-53500) |

| 2103/III | 92 | 3768660 | 40964 | 84.0% | 48791 | 92.7% | 52657 | 1.8% | 53639 | 53466 | 52413 | 54539 | 53500 (52500-54500) |

| 2013/IV | 92 | 3838620 | 41724 | 83.9% | 49719 | 92.5% | 53776 | 2.0% | 54849 | 54178 | 52967 | 55416 | 54000 (53000-55500) |

Figure 5.

SHI-covered TCM prescriptions and estimated numbers of HIV infected people with ART experience in Germany, 2006 to 2013. Step by step estimation of the number of HIV-infected people with ART experience shown as smoothed and rounded numbers, exact numbers are shown in Table 3.

Discussion

We estimated the number of people living with HIV who received ART based on SHI prescription data and on ART history data from the CSH. An underlying assumption was that the ART regimens and treatment interruptions recorded in the CSH would similarly apply to HIV-infected people outside of the cohort and that the prescription numbers in the APD would be comparable with all people living with HIV in Germany.

In the 2006–2013 observation period, substantial increases were observed for the number of people living with HIV receiving ART and for the number of HIV-infected people with ART experience in Germany. Concomitantly, the use of regimens that included TCMs increased continuously, whereas treatment interruptions in the CSH decreased remarkably.

In an earlier estimation approach by Kollan et al., the calculation was based on the daily drug dosages of all substances. In our opinion, the new approach of calculating the number of individuals based mainly on unambiguous drugs (TCMs in this study) offers a simple and appropriate method that could be further adapted for other investigations.

At the beginning of the observation period, the percentage of CSH regimens that did not include TCMs was 15%, and it decreased by half over time.

In Germany and other industrialised countries with a large number of available antiretroviral drugs, the share of TCMs would need to be taken into account when using this approach to estimate the number of people living with HIV under antiretroviral treatment. However, in countries with fewer antiretroviral drug options, the number of people living with HIV receiving ART could potentially be calculated exclusively using the number of delivered TCMs, which would be a reliable and simple estimation method. Assuming that the proportion of TCM use in Germany will continue to increase, this approach could become even more effective for calculating German estimates.

The total number of all HIV-infected people with ART experience in Germany was estimated to be 31,500 in the first quarter of 2006 and increased continuously to 54,000 individuals by the end of 2013. According to our estimation, the observed study population of the CSH represents more than 20% of all treated patients in Germany. In the CSH all patients who are seen in the centres are automatically included into the cohort without the need for written informed consent. The CSH is therefore the least biased source available and is the largest nationwide cohort of HIV-positive patients. Nonetheless, the CSH in this study is only used to determine the corresponding proportion of non-TCM and treatment interruptions. In our opinion, the demographics do not affect the TCM proportion of those with access to ART. In order to verify this approach with regard to more uncommon ART regimens and first-line subsequent regimens we analysed the composition of regimens of the CSH patients. As shown, the vast majority of ART regimens in the CSH are main regimens which include two or three NRTIs and another drug class such as NNRTIs, PIs, INIs (Figure 3). This applies for first-line therapies as well as for following regimens considering we pooled all data of CSH patients together for the analysis of ART regimens, and therefore regimens after first-line therapy naturally had a greater impact. Non-TCM regimens were most frequently observed within the group minor regimen which was also the only group with a slight increase of only 1% over the study period. Until 2010, within the minor regimen group double or mono PIs and non-TCM-NRTI containing regimens were most frequently observed, and from 2010 to the end of the observation period NRTI-sparing regimens, e.g. PI/AI and PI/INI continuously increased. If the prescribing patterns regarding regimens without TCMs would change in the future then this would have to be considered for our approach. However, this is not the case for the described study period.

It is interesting to note the considerable decline in CSH treatment interruptions. This reflects recent findings showing that there are more risks than benefits from so-called drug holidays [35-37]. In current HIV treatment guidelines, structured treatment interruptions are no longer recommended and are only considered individually under special circumstances [38]. However, currently between 2% of interruption time is apparently an inevitable fact.

In the APD data, we observed a systematic seasonal effect, with the fewest prescriptions at the beginning of each year and the most by the end of the year. We speculate that this effect may be caused by differing patient demand driven by practical considerations with regard to the beginning of the new year (i.e., Christmas holidays, closing of medical offices) and/or prescription co-payments whose reimbursements depend on the annual amounts of all individual co-payments within a calendar year.

Our approach may lead to an overestimation of the number of people receiving continuous ART by patients receiving only short-term ART. This might be relevant in case of discontinuation of therapy early in a quarter or when patients received a PEP.

When a person discontinued therapy before the medication was consumed, we counted that person as someone who was treated, but this person would not get prescriptions in the next quarter, and the overestimation would have been offset in the next billing period.

Representative data regarding the number of PEP prescriptions are rare. Studies regarding PEP are often performed in certain populations with limited significance for the general public. To account for the overestimation resulting from PEP prescriptions, we attempted to determine the number of PEP prescriptions using available studies and sources. We assumed that most PEP prescriptions would come from physicians who were authorised for the special care of patients with HIV/AIDS according to the HIV/AIDS Quality Assurance Agreement (§ 135 para 2 SGB V). According to our findings, the number of PEP prescriptions was estimated to be approximately 2400–2800 per year in Germany [39,40]. Considering that 12 PEP prescriptions are necessary to result in one patient treated per year, an overestimation of approximately 200 to 233 patients in total could have occurred. In terms of the total number of approximately 54,000 people living with HIV receiving ART in Germany, the resulting overestimation would be comparatively small.

On average, the increase in the number of people living with HIV receiving ART was approximately 2,900 persons per year in Germany. This increase should not be confused with the number of persons who initiated therapy, but rather represents the difference between people who initiated ART and those who discontinued treatment because of emigration or death. Thus, the true number of persons who began treatment is probably higher than the observed difference.

The proportion of people covered by PHI differed among the federal states. Those federal states with higher PHI coverage, e.g. City-States, tend to be those with a higher number of prescriptions. We therefore used a weighted SHI-coverage factor based on the data for each federal state and applied it to the antiretroviral prescription data in order to improve the estimates. Using the nationwide SHI-coverage factor would underestimate the total number by 1.6% (N = 650 persons).

With this study, we provide a nationwide estimate and a useful tool for calculating the number of people living with HIV who received ART, those with ART experience and the increase in ART usage between 2006 and 2013 in Germany using the available number of prescriptions and surveillance data from the CSH.

This approach can be useful to estimate the number of people living with HIV and those receiving ART in other countries. Additionally, the described methodology could potentially be used and adapted for other investigations or medications in the future.

Limitations

The described approach has some limitations. One limitation is an overestimation resulting from the cases that were discussed above. Of those cases, the number of PEP prescriptions is the most uncertain, which could be the main limitation.

Overall, our aim was to estimate the number of treated patients among all persons with access to ART. We do not aim to, and therefore do not, estimate the number of non-treated patients among all people infected with HIV in Germany.

Lamivudine is approved for the treatment of hepatitis B with a dose of 100 mg once daily for persons not infected with HIV. The use of lamivudine with approval for HIV therapy (150 mg and 300 mg) in the treatment of hepatitis B of HIV-negative individuals attributable to economic considerations cannot be excluded. However, the off-label use of HIV-labelled lamivudine would require an alternative dosing regimen by administration on alternating days and/or by dividing the pills, which we consider impractical in reality.

A limitation with regard to applying this approach in the future is that if TCM prescribing patterns, such as the currently discussed dual NRTI-sparing therapies, or other treatment practices significantly change, the impact of a second source (in our case, the CSH) on the estimate would be greater.

Conclusions

This report describes the first comprehensive approach to estimating the number of people living with HIV who receive ART. The study provides a possible approach for determining the number of people receiving specialised HIV medical care in Germany. This method allows for contrasting the numbers of people living with HIV receiving ART derived from different sources or estimation approaches. This approach can be useful to estimate the number of people living with HIV and those receiving ART in other countries. The described methodology could be used and adapted for different investigations or medications in the future. Non-TCM regimens and CSH treatment interruptions declined notably. Assuming that this trend will continue in the future, the number of people living with HIV receiving ART could be estimated exclusively using TCM-containing prescriptions. In other settings with fewer available antiretroviral drugs, the estimation would be even more robust.

It is also of interest to note trends in antiretroviral therapy with regard to NRTI-free regimens. In this context, the relevance of data from cohort studies remains very high for observing and assessing such developments.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the patients who joined the ClinSurv HIV cohort and to all collaborative treatment centres. The authors would like to thank Viviane Bremer for her helpful and constructive comments on the manuscript. We are grateful to Katie Ann Jacques for her critical feedback and advice on this article.

Footnotes

Daniel Schmidt and Christian Kollan contributed equally to this work.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

DS contributed to the conception of the study and interpretation of the data, performed the data analysis and statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. CK was responsible for the study design, devised the estimation approach, performed the data analysis and interpretation of the data, was responsible for database management and helped to draft the manuscript. MH performed the negative binomial regression with quadratic time trend. OH was responsible for the design and implementation of the CSH and supported the overall analysis approach and the writing of the manuscript. BB supported the management and coordination of the study, served as the CSH study coordinator, contributed to improving data quality and coverage and helped to draft the manuscript. AK managed the data collection. MS, H-JS, AP, GF, FB, JB, JvL, JR, SE, B-EJ, H-AH, CF contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools and data. All authors participated in the critical discussion of the results, and all read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

Daniel Schmidt and Christian Kollan are joint first authors.

Contributor Information

Daniel Schmidt, Email: SchmidtD@rki.de.

Christian Kollan, Email: KollanC@rki.de.

Matthias Stoll, Email: Stoll.Matthias@mh-hannover.de.

Hans-Jürgen Stellbrink, Email: stellbrink@ich-hamburg.de.

Andreas Plettenberg, Email: Plettenberg@ifi-infektiologie.de.

Gerd Fätkenheuer, Email: g.faetkenheuer@uni-koeln.de.

Frank Bergmann, Email: Frank.bergmann@charite.de.

Johannes R Bogner, Email: Johannes.Bogner@med.uni-muenchen.de.

Jan van Lunzen, Email: v.lunzen@uke.uni-hamburg.de.

Jürgen Rockstroh, Email: rockstroh@uni-bonn.de.

Stefan Esser, Email: Stefan.Esser@uk-essen.de.

Björn-Erik Ole Jensen, Email: bjoern-erikole.jensen@med.uni-duesseldorf.de.

Heinz-August Horst, Email: h.horst@med2.uni-kiel.de.

Carlos Fritzsche, Email: Carlos.Fritzsche@med.Uni-Rostock.de.

Andrea Kühne, Email: KuehneA@rki.de.

Matthias an der Heiden, Email: AnderHeidenM@rki.de.

Osamah Hamouda, Email: HamoudaO@rki.de.

Barbara Bartmeyer, Email: Gunsenheimer-BartmeyerB@rki.de.

References

- 1.Walensky RP, Paltiel AD, Losina E, Mercincavage LM, Schackman BR, Sax PE, et al. The survival benefits of AIDS treatment in the United States. J Infect Dis. 2006;194(1):11–9. doi: 10.1086/505147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palella FJ, Jr, Delaney KM, Moorman AC, Loveless MO, Fuhrer J, Satten GA, et al. Declining morbidity and mortality among patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(13):853–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199803263381301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Ledergerber B, Tilling K, Weber R, Sendi P, et al. Long-term effectiveness of potent antiretroviral therapy in preventing AIDS and death: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2005;366(9483):378–84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67022-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mocroft A, Ledergerber B, Katlama C, Kirk O, Reiss P, Monforte A, et al. Decline in the AIDS and death rates in the EuroSIDA study: an observational study. Lancet. 2003;362(9377):22–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13802-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wong KH, Chan KCW, Lee SS. Delayed progression to death and to AIDS in a Hong Kong cohort of patients with advanced HIV type 1 disease during the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39(6):853–60. doi: 10.1086/423183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hogg R, Lima V, Sterne J, Grabar S, Battegay M, Bonarek M, et al. Life expectancy of individuals on combination antiretroviral therapy in high-income countries: a collaborative analysis of 14 cohort studies. Lancet. 2008;372(9635):293–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61113-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson LF, Mossong J, Dorrington RE, Schomaker M, Hoffmann CJ, Keiser O, et al. Life expectancies of South african adults starting antiretroviral treatment: collaborative analysis of cohort studies. PLoS Med. 2013;10(4):e1001418. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.May M, Gompels M, Sabin C. Life expectancy of HIV-1-positive individuals approaches normal conditional on response to antiretroviral therapy: UK Collaborative HIV Cohort Study. J Int AIDS Soc. 2012;15(6 (Suppl 4)).

- 9.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). Global report: UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic 2013. UNAIDS; WHO; 2013.

- 10.Brown AE, Nardone A, Delpech VC. WHO ‘Treatment as Prevention’ guidelines are unlikely to decrease HIV transmission in the UK unless undiagnosed HIV infections are reduced. AIDS. 2014;28(2):281–3. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bundesärztekammer. The healthcare system in Germany. [Web Page] Bundesärztekammer. 2013 [updated 30.07.2013; cited 2013 September]. Available from: http://www.bundesaerztekammer.de/page.asp?his=4.3571.

- 12.Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung (bpb). Bismarcks Erbe: Besonderheiten und prägende Merkmale des deutschen Gesundheitswesens [Web Page]. Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung (bpb). 2012 [cited 2013 10. September]. Available from: http://www.bpb.de/politik/innenpolitik/gesundheitspolitik/72553/deutsche-besonderheiten?p=all.

- 13.Busse R, Blümel M. Health systems in transition. Germany Health Syst Rev. 2014;16(2):1–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bätzing-Feigenbaum J, Kollan C, Kühne A, Matysiak-Klose D, Gunsenheimer-Bartmeyer B, Hamouda O. Cohort profile: the German ClinSurv HIV project–a multicentre open clinical cohort study supplementing national HIV surveillance. HIV Medicine. 2011;12(5):269–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2010.00879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Broder S. The development of antiretroviral therapy and its impact on the HIV-1/AIDS pandemic. Antivir Res. 2010;85(1):1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cihlar T, Ray AS. Nucleoside and nucleotide HIV reverse transcriptase inhibitors: 25 years after zidovudine. Antivir Res. 2010;85(1):39–58. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2009.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deutsche AIDS-Gesellschaft (DAIG). Deutsch-Österreichische Leitlinien zur antiretroviralen Therapie der HIV-Infektion. Guideline. 2014; Version 1.0 from 13.5.2014.

- 18.Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults Adolescents. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. Dep Health Hum Serv. 2013:1–267.

- 19.Zolopa AR. The evolution of HIV treatment guidelines: current state-of-the-art of ART. Antivir Res. 2010;85(1):241–4. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2009.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hirnschall G, Harries AD, Easterbrook PJ, Doherty MC, Ball A. The next generation of the World Health Organization’s global antiretroviral guidance. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16(1):18757. doi: 10.7448/IAS.16.1.18757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gulick RM, Ribaudo HJ, Shikuma CM, Lustgarten S, Squires KE, Meyer WA, III, et al. Triple-nucleoside regimens versus efavirenz-containing regimens for the initial treatment of HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(18):1850–61. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bierman WF, van Agtmael MA, Nijhuis M, Danner SA, Boucher CA. HIV monotherapy with ritonavir-boosted protease inhibitors: a systematic review. AIDS. 2009;23(3):279–91. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32831c54e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Delfraissy J-F, Flandre P, Delaugerre C, Ghosn J, Horban A, Girard P-M, et al. Lopinavir/ritonavir monotherapy or plus zidovudine and lamivudine in antiretroviral-naive HIV-infected patients. AIDS. 2008;22(3):385–93. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f3f16d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stoll M, Kollan C, Bergmann F, Bogner J, Faetkenheuer G, Fritzsche C, et al. Calculation of direct antiretroviral treatment costs and potential cost savings by using generics in the German HIV ClinSurv cohort. PLoS One. 2011;6(9):e23946. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McKinnell JA, Willig JH, Westfall AO, Nevin C, Allison JJ, Raper JL, et al. Antiretroviral prescribing patterns in treatment-naive patients in the United States. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2010;24(2):79–85. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Willig JH, Abroms S, Westfall AO, Routman J, Adusumilli S, Varshney M, et al. Increased regimen durability in the era of once daily fixed-dose combination antiretroviral therapy. AIDS (London, England) 2008;22(15):1951. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32830efd79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wandeler G, Keiser O, Hirschel B, Günthard HF, Bernasconi E, Battegay M, et al. A Comparison of initial antiretroviral therapy in the Swiss HIV Cohort Study and the recommendations of the International AIDS Society-USA. PLoS One. 2011;6(12):e27903. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keiser O, Orrell C, Egger M, Wood R, Brinkhof MW, Furrer H, et al. Public-health and individual approaches to antiretroviral therapy: township South Africa and Switzerland compared. PLoS Med. 2008;5(7):e148. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suárez-García I, Sobrino-Vegas P, Tejada A, Viciana P, Ribas M, Iribarren J, et al. Compliance with national guidelines for HIV treatment and its association with mortality and treatment outcome: a study in a Spanish cohort. HIV Medicine. 2014;15(2):86–97. doi: 10.1111/hiv.12078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hughes B. Tapping into combination pills for HIV. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:439–40. doi: 10.1038/nrd2917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gogl S, Jöchl M, Kitchen M, Sarcletti M, Zangerle R. HIV/AIDS in Austria 2010 - 17th Report of the Austrian HIV cohort study. AGES Report. Vienna: 2010.

- 32.Gisinger M, Gogl S, Kitchen M, Sarcletti M, Sturm G, Zangerle R. HIV/AIDS in Austria 2013 - 23th Report of the Austrian HIV cohort study. AGES Report. Vienna: 2013.

- 33.Tweya H, Ben-Smith A, Kalulu M, Jahn A, Ng W, Mkandawire E, et al. Timing of antiretroviral therapy and regimen for HIV-infected patients with tuberculosis: the effect of revised HIV guidelines in Malawi. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):183. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.The Information System of the Federal Health Monitoring. Number of members and jointly insured family members of the statutory health insurance on July 1st of the rspective year (KM 6). Classification: years, germany, age, sex, type of statutory health insurance, group of persons insured 2014. [Web Page]. Available from: http://www.gbe-bund.de/.

- 35.El-Sadr W, Neaton J. Episodic CD4 guided use of antiretroviral therapy is inferior to continuous therapy: Results of the SMART study. Program and abstracts of the 13th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections. February 5–8, 2006; Denver, Colorado. Abstract 106LB.

- 36.Siegel L, El-Sadr W. New Perspectives in HIV Treatment Interruption: The SMART Study. The PRN Notebook. 2006;11(2).

- 37.Gadd C. CROI: CD4-guided treatment interruptions unsafe, SMART study concludes. NAM Publications aidsmap. 2006. Available from: http://www.aidsmap.com/page/1422937/.

- 38.Carter M, Hughson G. Treatment breaks. NAM Publications aidsmap; 2012. Available from: http://www.aidsmap.com/Treatment-breaks/page/1044580/.

- 39.Langer PC, Drewes J. Zur Bedeutung der Postexpositionsprophylaxe (PEP) in der HIV-Prävention. Schriftenreihe des Arbeitsbereichs Prävention und psychosoziale Gesundheitsforschung Nr. 01/P09. 2009.

- 40.Herida M, Larsen C, Lot F, Laporte A, Desenclos J-C, Hamers FF. Cost-effectiveness of HIV post-exposure prophylaxis in France. AIDS. 2006;20(13):1753–61. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000242822.74624.5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]