Abstract

Currently, the clinical use of sweat as biofluid is limited. The collection of sweat and its analysis for determining ethanol, drugs, ions, and metals have been encompassed in this review article to assess the merits of sweat compared to other biofluids, for example, blood or urine. Moreover, sweat comprises various biomarkers of different diseases including cystic fibrosis and diabetes. Additionally, the normalization of sampled volume of sweat is also necessary for getting efficient and useful results.

1. Introduction

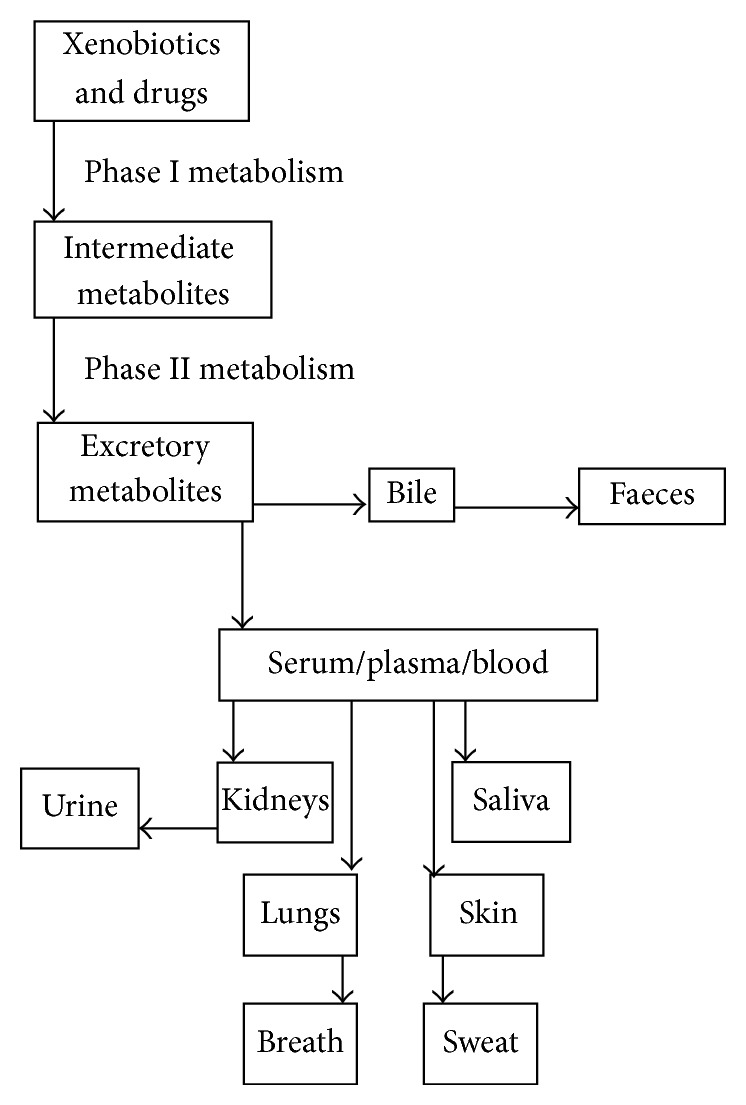

Similar to the sebaceous glands or hair follicles, sweat glands are epidermal appendages that are normally distributed over the whole body, excluding the nipples, lips, and external genital organs. Sweat glands are involved in perspiration and act as excretory organ like kidney and lungs for drugs and their metabolites, as shown in Figure 1. On the basis of morphology or secretory mechanism, there are two types of sweat glands, that is, eccrine and apocrine glands. Sweat glands allow the secretion of sweat through or without pinching off of outer cell parts [1]. Sweat is normally a transparent biofluid with low tonicity and slightly acidic nature with mean pH 6.3, that is, more acidic than blood [2]. Thus, basic drugs preferably accumulate in sweat than blood, based on pH partition theory [3]. The transport of water insoluble drugs between blood and other biofluids depends on the pH of the other biofluids and the drug's pKa which are helpful in theoretical computation of the biofluid-to-plasma concentration ratio of drug using Henderson-Hasselbalch equation [3, 4]. The concentration gradient between plasma and sweat provides driving force for passive diffusion of the free fraction of drug from plasma to sweat through lipid bilayer [3–5]. The main content of sweat is water (~99%) [2]. Besides, small amounts of the following substances are also present: nitrogenous compounds such as amino acids and urea [6]; metal and nonmetal ions such as potassium, sodium, and chloride ions [3]; metabolites including lactate and pyruvate; and xenobiotics such as drug molecules [2]. In disease state, sweat may contain different ingredients as biomarkers of the particular disease [2, 3, 6]. Blood, urine, saliva, and sweat are the biofluids, which are used for clinical analyses such as pharmacokinetics study. Due to the presence of very nominal impurities, the sample preparation of sweat is very easy as compared with other biofluids. In addition, sweat samples are less prone to adulterations; thus such samples can be stored for long periods [7]. Unlike other biofluids, sweat possesses excellent features including its noninvasive sampling. Owing to this characteristic, sweat analysis is considered as a rapid and easy process in comparison to other biofluids, especially blood. Blood sampling is an invasive procedure; that is, it needs surgery. Patients, who require frequent analysis, are therefore at higher risk of infection. In addition, blood samples are further processed for plasma protein removal. In addition, the preparation of sweat sample is easier than that of urine. This merit of sweat as biofluid is particularly important in doping control where results are urgently needed [8, 9]. Beside these advantages, clinical use of sweat samples is presently limited due to high costs [10], time-consuming sampling, infectivity hazards, and the need of volume normalization [11]. In addition, the rigorous attention should be paid to the analysis of metabolic products present in sweat [12].

Figure 1.

Routes of excretion of various products after liver metabolism.

Due to increased interest in the clinical use of sweat, various approaches for sweat sampling and analysis have been documented. Thus, the objective for preparing this review article involved the summarization of various apparatus and techniques used for sampling of sweat and its analysis. Furthermore, the applications of sweat in clinical settings have also been discussed.

2. Sweat as Biofluid

2.1. Induction of Perspiration

Apart from sampling and analysis, the induction of perspiration is a distinct phenomenon unlike other biofluids, which are rather directly collected. The physiological factors which enhance perspiration for getting certain volume of sweat include exercise and stress, while reduced perspiration is observed in cold [1]. For receiving sweat volume adequate for subsequent analysis, there are many factors which induce perspiration for sampling objective; these factors include environmental factors (such as temperature and relative humidity), body regulatory systems (hormonal and sympathetic nervous system), diet, and certain sweat inducing chemical compound such as pilocarpine. Together with a low intensity electrical current (~3.0 mA) applied for approximately five minutes, pilocarpine is applied on small area of leg or arm for induction of sweating [37].

2.2. Sampling of Sweat

An ideal sampler is the one that is user-friendly and harmless to skin and quickly collects the sweat in sufficient volumes. Various versions of sweat samplers have been designed and used for sweat sampling. The simplest sampling technique involved the use of an occlusive patch consisting of 2-3 layers of filter paper or gauze. However, this approach was time-consuming and difficult to adopt owing to large size of patch. Moreover, these patches were nonadjustable to skin [38]. The variation in sample pH and irritation to skin were other drawbacks of this method [18]. To avoid skin irritation, nonocclusive device was prepared using Whatman filter paper patch fixed on surgical dressing film lined with an adhesive layer for adjusting to arm skin. This patch was safer to the underneath skin because of selective transfer of water, oxygen, and carbon dioxide through this semipermeable film, which hindered penetration of nonvolatile substances [38]. Since these patches allowed evaporation of water from concentrated sweat leaving sweat components such as chlorides, the entire volume of secreted sweat was not known. Resultantly, from the collected samples, the results for cystic fibrosis (CF) test were not authentic. Later on, the problem of water evaporation was solved by using air- and water-tight, sweat collection bag connected with adhesive rubber. This advanced device was capable of retaining the whole volume of secreted sweat [39]. Moreover, the design of this device was further modified by connecting it with glass rollers, pipettes, and holders to make it suitable for collection of sweat secreted in limited volumes [40].

For efficient analysis, the sweat samplers are usually associated with the analytical instruments [41]. Macroduct and Megaduct are the most frequently used commercial samplers, available in different volumes (15 μL–0.5 mL). Macroduct and Megaduct are used for collection of smaller (15 μL) and larger (0.5 mL) volumes of sweat, respectively. Both tools contain a concave disk and a spiral plastic tube for sweat collection [42]. Another modern sweat-sampling device is microstrip impregnated with a dye pH indicator that is a smart-phone application for in situ colorimetric testing [43].

2.3. Sample Preparation for Analysis

Generally, sweat is directly analyzed; however, sweat samples can further be processed if lipid or protein moieties are detected in sweat. After sample collection, various procedures, including liquid-liquid extraction and solid-phase extraction, for the preparation of samples are used. Liquid-liquid extraction involves the use of analyte-specific solvents (e.g., aqueous phosphate buffer and organic solvents, e.g., methanol and acetonitrile) [37]. Solid-phase extraction involves the use of cartridges that internally consists of copolymers [8]. Sometimes the drugs, xenobiotics, and electrolytes are adequately discriminatory at the detector, and then their derivatization is also carried out during sample preparation for appropriate detection or separation [44].

2.4. Analysis of Sweat

The quality of sweat analysis depends on the efficiency of sample collection and the accuracy and sensitivity of analytical methods [2–5, 9, 42]. Currently, different analytical approaches have been used for the analysis of unmetabolized drugs in sweat; however further focus of researchers is needed for studying drug metabolites present in sweat normalized with its volume. Most of the sweat analyzers work on the principle of potentiometry, colorimetery, conductivity, or osmolarity [43].

On coupling with mass spectrometers (MS), capillary electrophoresis and chromatographic approaches such as liquid-chromatography (LC) and gas-chromatography (GC) are valuable for high-resolution separation of drugs or complex metabolites in sweat. For drug analysis in sweat, the most frequently used equipment is GC-MS coupled with electron impact ionization [7–9, 12, 37, 44–46]. Moreover, LC-MS/MS coupled with electrospray ionization has also been successfully used [37, 47] to determine drug concentration in sweat. In this context, immunoassay approaches including radioimmune analysis and ELISA are also being employed [8, 12, 37, 45]. Table 1 describes some approaches for separation and detection-determination of drugs of abuse in sweat [8, 10, 13–19].

Table 1.

Some approaches for separation and detection-determination of drugs of abuse in sweat.

| Number | Analytical approach | Examples of some analyzed drugs | Limit of quantification (ng per patch) |

References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | GC-MS (electron ionization) | Cocaine, codeine, 6-acetylcodeine, morphine, 6-acetylmorphine, and heroin | 5–10 | [8] |

| 2 | GC-MS (electron ionization) | Cocaine, codeine, 6-acetylcodeine, morphine, 6-acetylmorphine, and heroin | 5 | [13] |

| GC-MS (electron ionization) | Methadone | 50 | [14] | |

| 3 | GC-MS (electron ionization) | Cocaine, codeine, 6-acetylcodeine, morphine, and heroin | 50 | [15] |

| 4 | GC-MS (electron ionization) | Codeine, morphine, and 6-acetylmorphine | 2.5 | [16] |

| 5 | GC-MS (electron ionization) | Cocaine and heroin | Not mentioned | [17] |

| 6 | GC-MS (electron ionization) | Cocaine, codeine, morphine, and 6-acetylmorphine | 2.5 | [18] |

| 7 | ELISA and GC-MS (electron ionization) | Codeine, morphine, 6-acetylmorphine, and heroin | 3–5 | [10] |

| 8 | LC-MS-MS (electrospray ionization) | Fentanyl | 0.09 | [19] |

To analyze sweat, the analytical instrument is selected in accordance with the nature of target analyte(s) such as sodium or chloride ions [48]. For single moiety analysis, some of the most frequently used dedicated analyzers are the potentiometric Orion skin ion selective electrode (ISE) for chloride (Orion Research, Cambridge, MA), or the colorimetric Scandipharm CF Indicator System chloride patch (Scandipharm, Birmingham, AL), the Wescor Sweat-Chek conductivity analyzer (Wescor, Logan, UT), and sweat osmolarity analyzer (Nikon Research, Cambridge, ML) [49].

Due to variable volumes of sweat samples, the normalization of sweat volume is also necessary for getting authentic results [6]. For normalizing the sweat volume, Appenzeller and coauthors introduced the concept of internal standard by using and determining the level of sodium and potassium using capillary zone electrophoresis linked with diode array detector set at 214 nm [39]. However, a study has suggested that sodium ion concentration is more suitable for using in the normalization of sampled volume of sweat than potassium ion concentration [50]. However, the concept of normalization of sampled volume of sweat has not yet been applied for the diagnosis of CF.

3. Applications of Sweat Analysis

3.1. Diagnosis of Diseases

Since last three decades, much attention has been paid towards application of sweat in disease diagnosis. The best example of a disease diagnosed through sweat analysis is cystic fibrosis (CF). This disease originates from genetic transformations in CFTR proteins (cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulating proteins) in the sweat gland. The CFTR proteins are, normally, responsible for the transport of sodium and chloride (transportNa-Cl) in epithelial secreting cells. The genetic modification of CFTR causes the change in transportNa-Cl resulting in formation of sticky mucus in various organs such as lung, intestine, and other organs. This condition leads to serious repeated infections of the pancreas affected organs. Moreover, male infertility and dehydration are also observed in CF patients. The sweat analysis for sodium/chloride ratio (sodium and chloride contents) can, therefore, be useful in diagnosing CF. In particular, chloride level is disturbed in CF due to mutation in CFTR, and thus sweat chloride can be referred to as the biomarker for CF diagnosis [51, 52]. On the basis of this biomarker, there are two types of CF, that is, typical and atypical CF. With a minimum of one phenotype appearance, chloride contents ≥ 60 mmol per liter of sweat indicate typical (real positive) CF while atypical CF is manifested with chloride concentration in borderline range of 30–60 mmol per liter of sweat. The normal (and borderline) concentrations of chloride in sweat are <30 mmol/L (30–59 mmol/L) and <40 mmol/L (40–59 mmol/L) in infants and elders [51]. Moreover, sweat potassium as another biomarker is the focus of current research for early diagnosis of CF that assists in treatment efforts for the diseased person; however clinical application of this new biomarker is still under investigation [53].

On the basis of sweat analysis, diabetic biomarkers have also been reported such as the average change in sweat rates [54], composition of human sweat [40], and correlation between sweat glucose and blood glucose. The later approach produces promising results provided sweat gains no glucose from environment [55]. This diagnostic technique involves the analysis of foot sweat using a simple, reproducible indicator test [56] on the basis of color change of a patch from blue (due to the presence of anhydrous cobalt-II-chloride) to pink at 10 min on adding 6 water molecules.

Jurado Gámez et al. have proposed sweat-based diagnostic assay for lung cancer by discriminating between metabolomics of healthy and diseased subjects. In this promising approach, sweat is diluted with 0.1% formic acid followed by the injection of sample into LC-TOF/MS which necessitates only 10 μL of sweat [57].

Genomics and proteomics have played a key role for searching sweat biomarkers such as dermcidin (DCD). Sweat contains DCD, a peptide containing 47-amino acids, which possesses antimicrobial activity against different pathogens in high salt concentrations and over an extensive pH range resembling to the human sweat. For this reason, sweat is considered to be crucial for human skin microflora [58]. Moreover, DCD and the receptors for DCD are present and overexpressed on the cell surface of invasive breast carcinomas and their lymph node metastases and neurons of the brain. These findings reveal that DCD is involved in tumorigenesis by promoting cell growth and survival in breast carcinomas [59]. Another prognostic biomarker is prolactin inducible protein (PIP) which is expressed in many exocrine tissues including sweat glands and is overexpressed in metastatic breast and prostate cancer [60]. In addition, prognostic biomarkers have also been investigated in a study performed on eccrine sweat in healthy and schizophrenic patients. The eccrine sweat contains plenty of various proteins and peptides unlikely to that of serum showing that eccrine sweat may produce distinctive disease-linked biomolecules [6].

3.2. Assessment of Drugs and Ethanol in Sweat

Currently, sweat analysis for drug contents is accomplished through two approaches, that is, early and late testing. First methodology involves the immunochromatographic testing for qualitative detection of recently used drugs (within 24 h) involving sweat sample collected at single time point for identifying the individuals who are under the effect of drugs. Second methodology involves the patch technology for qualitative detection of previously used drugs (within 168 h) involving sweat sample collected at single time point for the follow-up of drug users under treatment to substantiate abstinence [3, 61, 62].

Together with urine, sweat is an ideal sample for doping control. The volume of sweat perspired by the whole human body in one day is 300–700 mL. This biofluid contains a small but quantifiable percent of a drug [63] excreted through transcellular and paracellular pathways in skin [11, 64]. The reported drugs excreted through sweat in a quantifiable fraction are the opiates, buprenorphine, amphetamines, gamma hydroxybutyrates, cocaine, and cannabinoids [9, 65]. In addition, ethanol contents in sweat as a function of time have also been successfully analyzed after ingesting ethanol [51].

3.3. Assessment of Metals, Ions, and Salts in Sweat

Xenometabolomics is a branch of science that deals with the study of essential metals and xenometals in the organism contaminated through either ingestion of food or absorption through skin by occupational exposures [66]. After getting into body, some metals are converted to their xenometabolites (cations or salts) followed by their solubilization in sweat. In addition to excretion of metals as their free metals, ions, or simple salts, excretion of some metals occurs in the form of their complexes. For example, lead complexed with high molecular weight compounds excretes through sweat [25]. The excreted sweat concentrations of some metals (e.g., cadmium and lead) or their cations, salts, or complexes are sometimes comparable to those of urine; thus sweat can be used as a biofluid alternate of urine, particularly in some kidney disease [29, 34]. Table 2 elaborates the studies of metal excretion in sweat conducted in different countries. It can therefore be stated that perspiration is a potential route for the excretion of toxic metals from the body.

Table 2.

Studies of metal excretion in sweat.

| Number | Metals | Country of study subjects | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mercury | Canada | Genuis et al., 2011 [20] |

| 2 | USA | Robinson and Skelly, 1983 [21] | |

| 3 | USA | Sunderman 1978 [22] | |

| 4 | USA | Lovejoy et al., 1973 [23] | |

|

| |||

| 5 | Cadmium | Australia | Stauber and Florence, 1988 [24] |

| 6 | Australia | Stauber and Florence, 1987 [25] | |

| 7 | USA | Robinson and Weiss, 1980 [26] | |

| 8 | USA | Cohn and Emmett, 1978 [27] | |

| 9 | Canada | Genuis et al., 2011 [20] | |

| 10 | UK | Omokhodion and Howard, 1994 [28] | |

|

| |||

| 11 | Arsenic | Canada | Genuis et al., 2011 [20] |

| 12 | Bangladesh | Yousuf et al., 2011 [29] | |

|

| |||

| 13 | Lead | Australia | Lilley et al., 1988 [30] |

| 14 | Australia | Stauber and Florence, 1988 [24] | |

| 15 | Australia | Stauber and Florence, 1987 [25] | |

| 16 | Canada | Genuis et al., 2011 [20] | |

| 17 | UK | Omokhodion and Crockford, 1991 [31] | |

| 18 | UK | Omokhodion and Crockford, 1991 [32] | |

| 19 | USA | Cohn and Emmett, 1978 [27] | |

| 20 | USA | Hohnadel et al., 1973 [33] | |

| 21 | Tropics | Omokhodion and Howard, 1991 [34] | |

| 22 | Russia | Parpaleĭ et al., 1991 [35] | |

| 23 | Germany | Haber et al., 1985 [36] | |

3.4. Assessment of Volatile Organic Compounds in Sweat

Large number of different compounds has been recognized in human sweat, out of which >500 compounds are volatile in nature [67]. Because of heterogeneous distribution of various sweat glands in skin, the profiles of volatile organic compounds (VOC) are different in different body regions, which also affect the odor of an individual [68, 69]. Moreover, VOC from personal care products and sweat may also interfere with each other during sweat analysis [70, 71]. In addition, compounds which are volatile at body temperature are directly collected, while the other substances are obtained through volatilization of collected sweat.

4. Conclusion

Based on sweat analysis, advancements in the genomics and proteomics have enormously contributed to the field of metabolomics and the systems biology. The metabolisms of the macromolecules in sweat glands produce lower molecular weight metabolites, such as the conversion of proteins to peptides or amino acids. Since, metabolomics deals with measurements of both precursor and metabolites, sweat can be used as a biofluid, in addition to blood and urine, to explore biomarkers for various diseases. Subsequently, these discoveries help in exploring effective therapeutic moieties. Since sweat consists of various biomarkers, these biomarkers have played an excellent role in diagnosis of cancer, diabetes, schizophrenia, and cystic fibrosis. Conclusively, sweat can be used as a promising biofluid for disease diagnosis and drug analysis.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Wilke K., Martin A., Terstegen L., Biel S. S. A short history of sweat gland biology. International Journal of Cosmetic Science. 2007;29(3):169–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-2494.2007.00387.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sato K., Kang W. H., Saga K., Sato K. T. Biology of sweat glands and their disorders. I. Normal sweat gland function. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1989;20(4):537–563. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(89)70063-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caplan Y. H., Goldberger B. A. Alternative specimens for workplace drug testing. Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 2001;25(5):396–399. doi: 10.1093/jat/25.5.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de la Torre R., Farré M., Navarro M., Pacifici R., Zuccaro P., Pichini S. Clinical pharmacokinetics of amfetamine and related substances: monitoring in conventional and non-conventional matrices. Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 2004;43(3):157–185. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200443030-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pichini S., Altieri I., Zuccaro P., Pacifici R. Drug monitoring in non-conventional biologic fluids and matrices. Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 1996;30(3):211–228. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199630030-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raiszadeh M. M., Ross M. M., Russo P. S., et al. Proteomic analysis of eccrine sweat: implications for the discovery of schizophrenia biomarker proteins. Journal of Proteome Research. 2012;11(4):2127–2139. doi: 10.1021/pr2007957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kintz P., Tracqui A., Mangin P., Edel Y. Sweat testing in opioid users with a sweat patch. Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 1996;20(6):393–397. doi: 10.1093/jat/20.6.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brunet B. R., Barnes A. J., Scheidweiler K. B., Mura P., Huestis M. A. Development and validation of a solid-phase extraction gas chromatography-mass spectrometry method for the simultaneous quantification of methadone, heroin, cocaine and metabolites in sweat. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry. 2008;392(1-2):115–127. doi: 10.1007/s00216-008-2228-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gallardo E., Queiroz J. A. The role of alternative specimens in toxicological analysis. Biomedical Chromatography. 2008;22(8):795–821. doi: 10.1002/bmc.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huestis M. A., Cone E. J., Wong C. J., Umbricht A., Preston K. L. Monitoring opiate use in substance abuse treatment patients with sweat and urine drug testing. Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 2000;24(7):509–521. doi: 10.1093/jat/24.7.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mena-Bravo A., Luque de Castro M. D. Sweat: a sample with limited present applications and promising future in metabolomics. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis. 2014;90:139–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2013.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huestis M. A., Scheidweiler K. B., Saito T., et al. Excretion of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol in sweat. Forensic Science International. 2008;174(2-3):173–177. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brunet B. R., Barnes A. J., Choo R. E., Mura P., Jones H. E., Huestis M. A. Monitoring pregnant women's illicit opiate and cocaine use with sweat testing. Therapeutic Drug Monitoring. 2010;32(1):40–49. doi: 10.1097/FTD.0b013e3181c13aaf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fucci N., de Giovanni N. Methadone in hair and sweat from patients in long-term maintenance therapy. Therapeutic Drug Monitoring. 2007;29(4):452–454. doi: 10.1097/ftd.0b013e31811f1bbe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fucci N., De Giovanni N., Scarlata S. Sweat testing in addicts under methadone treatment: an Italian experience. Forensic Science International. 2008;174(2-3):107–110. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2007.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwilke E. W., Barnes A. J., Kacinko S. L., Cone E. J., Moolchan E. T., Huestis M. A. Opioid disposition in human sweat after controlled oral codeine administration. Clinical Chemistry. 2006;52(8):1539–1545. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.067983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kidwell D. A., Smith F. P. Susceptibility of PharmChek drugs of abuse patch to environmental contamination. Forensic Science International. 2001;116(2-3):89–106. doi: 10.1016/s0379-0738(00)00353-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huestis M. A., Oyler J. M., Cone E. J., Wstadik A. T., Schoendorfer D., Joseph R. E., Jr. Sweat testing for cocaine, codeine and metabolites by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Journal of Chromatography B: Biomedical Sciences and Applications. 1999;733(1-2):247–264. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(99)00246-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schneider S., Ait-m-bark Z., Schummer C., et al. Determination of fentanyl in sweat and hair of a patient using transdermal patches. Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 2008;32(3):260–264. doi: 10.1093/jat/32.3.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Genuis S. J., Birkholz D., Rodushkin I., Beesoon S. Blood, urine, and sweat (BUS) study: monitoring and elimination of bioaccumulated toxic elements. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology. 2011;61(2):344–357. doi: 10.1007/s00244-010-9611-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robinson J. W., Skelly E. M. The direct determination of mercury in sweat. Spectroscopy Letters. 1983;16(2):133–150. doi: 10.1080/00387018308062329. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sunderman F. W. Clinical response to therapeutic agents in poisoning from mercury vapor. Annals of Clinical and Laboratory Science. 1978;8(4):259–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lovejoy H. B., Bell Z. G., Jr., Vizena T. R. Mercury exposure evaluations and their correlation with urine mercury excretions. 4. Elimination of mercury by sweating. Journal of Occupational Medicine. 1973;15(7):590–591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stauber J. L., Florence T. M. A comparative study of copper, lead, cadmium and zinc in human sweat and blood. Science of the Total Environment. 1988;74:235–247. doi: 10.1016/0048-9697(88)90140-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stauber J. L., Florence T. M. The determination of trace metals in sweat by anodic stripping voltammetry. Science of the Total Environment. 1987;60:263–271. doi: 10.1016/0048-9697(87)90420-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robinson J. W., Weiss S. The direct determination of cadmium in hair using carbon bed atomic absorption spectroscopy. Daily rate of loss of cadmium in hair, urine and sweat. Journal of Environmental Science and Health, Part A Environmental Science and Engineering. 1980;15(6):663–697. doi: 10.1080/10934528009374956. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohn J. R., Emmett E. A. The excretion of trace metals in human sweat. Annals of Clinical and Laboratory Science. 1978;8(4):270–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Omokhodion F. O., Howard J. M. Trace elements in the sweat of acclimatized persons. Clinica Chimica Acta. 1994;231(1):23–28. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(94)90250-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yousuf A. K. M., Misbahuddin M., Rahman M. S. Secretion of arsenic, cholesterol, vitamin E, and zinc from the site of arsenical melanosis and leucomelanosis in skin. Clinical Toxicology. 2011;49(5):374–378. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2011.577747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lilley S. G., Florence T. M., Stauber J. L. The use of sweat to monitor lead absorption through the skin. Science of the Total Environment. 1988;76(2-3):267–278. doi: 10.1016/0048-9697(88)90112-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Omokhodion F. O., Crockford G. W. Sweat lead levels in persons with high blood lead levels: experimental elevation of blood lead by ingestion of lead chloride. Science of the Total Environment. 1991;108(3):235–242. doi: 10.1016/0048-9697(91)90360-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Omokhodion F. O., Crockford G. W. Lead in sweat and its relationship to salivary and urinary levels in normal healthy subjects. Science of the Total Environment. 1991;103(2-3):113–122. doi: 10.1016/0048-9697(91)90137-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hohnadel D. C., Sunderman F. W., Jr., Nechay M. W., McNeely M. D. Atomic absorption spectrometry of nickel, copper, zinc, and lead in sweat collected from healthy subjects during sauna bathing. Clinical Chemistry. 1973;19(11):1288–1292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Omokhodion F. O., Howard J. M. Sweat lead levels in persons with high blood lead levels: lead in sweat of lead workers in the tropics. Science of the Total Environment. 1991;103(2-3):123–128. doi: 10.1016/0048-9697(91)90138-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parpaleĭ I. A., Prokof'eva L. G., Obertas V. G. The use of the sauna for disease prevention in the workers of enterprises with chemical and physical occupational hazards. Vracebnoe delo Kiev. 1991;(5):93–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haber P., Ring F., Jahn O., Meisinger V. Influence of intensive and extensive aerobic circulatory stress on blood lead levels. Zentralblatt fur Arbeitsmedizin, Arbeitsschutz, Prophylaxe und Ergonomie. 1985;35(10):303–306. (Ger). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barroso M., Gallardo E., Vieira D. N., Queiroz J. A., López-Rivadulla M. Bioanalytical procedures and recent developments in the determination of opiates/opioids in human biological samples. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry. 2011;400(6):1665–1690. doi: 10.1007/s00216-011-4888-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kintz P., Samy N. Unconventional samples and alternative matrices. In: Bogusz M. J., editor. Handbook of Analytical Separations. Vol. 2. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier Science; 2000. pp. 459–488. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Appenzeller B. M. R., Schummer C., Rodrigues S. B., Wennig R. Determination of the volume of sweat accumulated in a sweat-patch using sodium and potassium as internal reference. Journal of Chromatography B. 2007;852(1-2):333–337. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2007.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kutyshenko V. P., Molchanov M., Beskaravayny P., Uversky V. N., Timchenko M. A. Analyzing and mapping sweat metabolomics by high-resolution NMR spectroscopy. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028824.e28824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rowe S. M., Accurso F., Clancy J. P. Detection of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator activity in early-phase clinical trials. Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society. 2007;4(4):387–398. doi: 10.1513/pats.200703-043br. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ely M. R., Ely B. R., Chinevere T. D., Lacher C. P., Lukaski H. C., Cheuvront S. N. Evaluation of the Megaduct sweat collector for mineral analysis. Physiological Measurement. 2012;33(3):385–394. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/33/3/385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oncescu V., O'Dell D., Erickson D. Smartphone based health accessory for colorimetric detection of biomarkers in sweat and saliva. Lab on a Chip. 2013;13(16):3232–3238. doi: 10.1039/c3lc50431j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Staub C. Chromatographic procedures for determination of cannabinoids in biological samples, with special attention to blood and alternative matrices like hair, saliva, sweat and meconium. Journal of Chromatography B: Biomedical Sciences and Applications. 1999;733(1-2):119–126. doi: 10.1016/S0378-4347(99)00249-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pichini S. Distribution of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) in non conventional matrices and its applications in clinical toxicology [Thesis] Autonomous University of Barcelona; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Uemura N., Nath R. P., Harkey M. R., Henderson G. L., Mendelson J., Jones R. T. Cocaine levels in sweat collection patches vary by location of patch placement and decline over time. Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 2004;28(4):253–259. doi: 10.1093/jat/28.4.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gallardo E., Barroso M., Queiroz J. A. LC-MS: a powerful tool in workplace drug testing. Drug Testing and Analysis. 2009;1(3):109–115. doi: 10.1002/dta.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Segura J., Ventura R., Jurado C. Derivatization procedures for gas chromatographic-mass spectrometric determination of xenobiotics in biological samples, with special attention to drugs of abuse and doping agents. Journal of Chromatography B: Biomedical Applications. 1998;713(1):61–90. doi: 10.1016/S0378-4347(98)00089-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Legrys V. A. Sweat testing for the diagnosis of cystic fibrosis: practical considerations. Journal of Pediatrics. 1996;129(6):892–897. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(96)70034-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Myint K. T., Aoshima K., Tanaka S., Nakamura T., Oda Y. Quantitative profiling of polar cationic metabolites in human cerebrospinal fluid by reversed-phase nanoliquid chromatography/mass spectrometry. Analytical Chemistry. 2009;81(3):1121–1129. doi: 10.1021/ac802259r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barrio Gómez De Agüero M. I., García Hernández G., Gartner S., et al. Protocol for the diagnosis and follow up of patients with cystic fibrosis. Anales de Pediatria. 2009;71(3):250–264. doi: 10.1016/j.anpedi.2009.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Beauchamp M., Lands L. C. Sweat-testing: a review of current technical requirements. Pediatric Pulmonology. 2005;39(6):507–511. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Reddy M. M., Quinton P. M. Cytosolic potassium controls CFTR deactivation in human sweat duct. The American Journal of Physiology—Cell Physiology. 2006;291(1):C122–C129. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00134.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moyer J., Wilson D., Finkelshtein I., Wong B., Potts R. Correlation between sweat glucose and blood glucose in subjects with diabetes. Diabetes Technology and Therapeutics. 2012;14(5):398–402. doi: 10.1089/dia.2011.0262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Papanas N., Boulton A. J. M., Malik R. A., et al. A simple new non-invasive sweat indicator test for the diagnosis of diabetic neuropathy. Diabetic Medicine. 2013;30(5):525–534. doi: 10.1111/dme.12000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sikirzhytski V., Sikirzhytskaya A., Lednev I. K. Multidimensional Raman spectroscopic signature of sweat and its potential application to forensic body fluid identification. Analytica Chimica Acta. 2012;718:78–83. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2011.12.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jurado Gámez B., Salvatierra Velázquez A., Calderón Santiago M., Priego Capote F., Luque de Castro M. D. Patent Método de clasificación, diagnóstico y seguimiento de individuos con riesgo de padecer cáncer de pulmón mediante el análisis de sudor. P201331228, 13/P/S049, August 2013.

- 58.Porter D., Weremowicz S., Chin K., et al. A neural survival factor is a candidate oncogene in breast cancer. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100(19):10931–10936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1932980100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hassan M. I., Waheed A., Yadav S., Singh T. P., Ahmad F. Prolactin inducible protein in cancer, fertility and immunoregulation: structure, function and its clinical implications. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 2009;66(3):447–459. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8463-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Colpitts T., Russell E. L., Frost S., Ramirez J., Singh B., Russell J. C. Patent: method and marker combinations for screening for predisposition to lung cancer. Pub. No. US 2012/0071334 A1, 2012.

- 61.Pichini S., Navarro M., Pacifici R., et al. Usefulness of sweat testing for the detection of MDMA after a single-dose administration. Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 2003;27(5):294–303. doi: 10.1093/jat/27.5.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Samyn N., de Boeck G., Verstraete A. G. The use of oral fluid and sweat wipes for the detection of drugs of abuse in drivers. Journal of Forensic Sciences. 2002;47(6):1380–1387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.de la Torre R., Pichini S. Usefulness of sweat testing for the detection of cannabis smoke. Clinical Chemistry. 2004;50(11):1961–1962. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2004.040758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lozano J., García-Algar O., Vall O., De La Torre R., Scaravelli G., Pichini S. Biological matrices for the evaluation of in utero exposure to drugs of abuse. Therapeutic Drug Monitoring. 2007;29(6):711–734. doi: 10.1097/FTD.0b013e31815c14ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Samyn N., van Haeren C. On-site testing of saliva and sweat with drugwipe and determination of concentrations of drugs of abuse in saliva, plasma and urine of suspected users. International Journal of Legal Medicine. 2000;113(3):150–154. doi: 10.1007/s004140050287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bhattacharjee P., Chatterjee D., Singh K. K., Giri A. K. Systems biology approaches to evaluate arsenic toxicity and carcinogenicity: an overview. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health. 2013;216(5):574–586. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2012.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Buszewski B., Ligor T., Rudnicka J., Jezierski T., Walczak M., Wenda-Piesik A. Analysis of cancer biomarkers in exhaled breath and comparison with sensory indications by dog. In: Amann A., Smith D., editors. Volatile Biomarkers: Non-Invasive Diagnosis in Physiology and Medicine. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2013. pp. 177–192. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wallace P. Individual discrimination of humans by odor. Physiology & Behavior. 1977;19(4):577–579. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(77)90238-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kuukasjärvi S., Eriksson C. J. P., Koskela E., Mappes T., Nissinen K., Rantala M. J. Attractiveness of women's body odors over the menstrual cycle: the role of oral contraceptives and receiver sex. Behavioral Ecology. 2004;15(4):579–584. doi: 10.1093/beheco/arh050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gallagher M., Wysocki C. J., Leyden J. J., Spielman A. I., Sun X., Preti G. Analyses of volatile organic compounds from human skin. British Journal of Dermatology. 2008;159(4):780–791. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08748.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kuhn F., Natsch A. Body odour of monozygotic human twins: a common pattern of odorant carboxylic acids released by a bacterial aminoacylase from axilla secretions contributing to an inherited body odour type. Journal of the Royal Society Interface. 2009;6(33):377–392. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2008.0223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]