CD4+ T cell STAT3 Y705 activation and subsequent Th17 tissue invasion correlates with acute GVHD after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation.

Keywords: Treg, RORγT, mTOR

Abstract

Th17 cells contribute to severe GVHD in murine bone marrow transplantation. Targeted deletion of the RORγt transcription factor or blockade of the JAK2-STAT3 axis suppresses IL-17 production and alloreactivity by Th17 cells. Here, we show that pSTAT3 Y705 is increased significantly in CD4+ T cells among human recipients of allogeneic HCT before the onset of Grade II–IV acute GVHD. Examination of target-organ tissues at the time of GVHD diagnosis indicates that the amount of RORγt + Th17 cells is significantly higher in severe GVHD. Greater accumulation of tissue-resident Th17 cells also correlates with the use of MTX- compared with Rapa-based GVHD prophylaxis, as well as a poor therapeutic response to glucocorticoids. RORγt is optimally suppressed by concurrent neutralization of TORC1 with Rapa and inhibition of STAT3 activation with S3I-201, supporting that mTOR- and STAT3-dependent pathways converge upon RORγt gene expression. Rapa-resistant T cell proliferation can be totally inhibited by STAT3 blockade during initial allosensitization. We conclude that STAT3 signaling and resultant Th17 tissue accumulation are closely associated with acute GVHD onset, severity, and treatment outcome. Future studies are needed to validate the association of STAT3 activity in acute GVHD. Novel GVHD prevention strategies that incorporate dual STAT3 and mTOR inhibition merit investigation.

Introduction

GVHD and its therapy contribute to significant morbidity and mortality after allogeneic HCT. Systemic glucocorticoids and calcineurin inhibitors provide broad, nonselective immunosuppression. This limits the graft-versus-leukemia potential of the transplant and creates considerable risk for serious, life-threatening infections.

STAT3 activation is critically involved in the regulation of alloreactivity [1, 2]. pSTAT3 on Y705 induces its dimerization, which is required for nuclear translocation and binding its target gene promoters [3], such as RORγt. The STAT3-RORγt pathway is instrumental for pathogenic Th17 differentiation [4–6]. We recently demonstrated that direct, downstream inhibition of STAT3 significantly reduces Th17 alloresponses, while expanding potent inducible Tregs [2]. pSTAT3 on Y705 induces transcription of RORγt, IL-17, IL-21, and CCR6, which are required by developing Th17 cells, whereas STAT5 has opposing effects on those processes [4–6].

Th17 cells are relevant to the pathophysiology of GVHD and significantly contribute to disease severity. Titrated add-back of donor Th17 cells results in early onset, dose-dependent worsening of acute GVHD in murine bone marrow transplantation [7]. In GVHD models restricted to CD4+ effectors, molecular deletion of donor IL-17 or RORC/RORγt reduces the onset and lethality of alloreactivity [8, 9]. However, the combined elimination of RORγt and T-bet (required for Th1 differentiation) is necessary to optimize control over GVHD mediated by whole donor T cells [10]. Additionally, others have implicated Th17 cells in the development of glucocorticoid-resistant, autoimmune diseases of the GI tract [11].

Therefore, we hypothesized that STAT3 activation and subsequent Th17 tissue invasion may be associated with the onset and severity of acute GVHD among allogeneic HCT recipients. Here, we show that STAT3 activation of CD4+ T cells is increased in allogeneic HCT recipients who eventually develop acute GVHD. pSTAT3 of Y705 is detectable early post-transplant, even when the clinical syndrome is not yet recognized. We show that Th17 cells significantly accumulate within the target-organ tissues of those diagnosed with severe acute GVHD. We identify the STAT3-RORγt axis as an evaluable indicator of acute GVHD onset and therapy response to corticosteroids.

Independent of STAT3, the mTOR pathway also facilitates Th17 development via phosphorylation of serine residues on the S6 ribosomal protein [12, 13]. We previously demonstrated the superiority of Rapa over MTX-based immune suppression in preventing grade II–IV acute GVHD in a randomized clinical trial [14]. A multicenter, Phase III trial also showed that Rapa-based prophylaxis was associated with a reduction in severe Grade III–IV acute GVHD compared with MTX [15]. We now show that mTOR blockade with Rapa reduces the burden of tissue-resident Th17 and that Rapa resistance among alloresponders may be overcome with selective inhibition of STAT3. Finally, we demonstrate that combined inhibition of STAT3 and mTOR activation in human DC-allostimulated T cells optimizes immune suppression and maximally reduces RORγt expression. The latter finding is distinct from murine systems, where the disruption of mTOR impairs Th17 differentiation by blocking the nuclear translocation of the RORC gene (encodes for RORγt) as opposed to preventing its transcription [12].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

pSTAT3 among allogeneic HCT recipients

Patients over 18 years of age (n = 18) receiving an allogeneic peripheral blood or bone marrow HCT had a single peripheral blood sample collected day +21 after HCT. Eligibility for the STAT3 activation study (MCC 16925) was not restricted by primary malignancy, transplantation indication, conditioning regimen, or GVHD prophylaxis regimen. All enrolled patients demonstrated an absolute neutrophil count >500 at the time of peripheral blood collection. Patients were consented in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Recipients of umbilical cord blood grafts were not eligible as a result of concern for associated lymphopenia at day +21. Patients demonstrating any proven or potential signs (nausea, diarrhea, rash, and/or hyperbilirubinemia) or diagnosis of acute GVHD at or before day +21 were excluded from the investigation. Additionally, patients receiving systemic glucocorticoids were deemed ineligible. pSTAT3 was measured by flow cytometry at day +21 (±2 days) from allograft infusion, as described below. T cell pSTAT3 was also measured in samples from healthy volunteers (n = 5; OneBlood, St. Petersburg, FL, USA). Descriptive data were collected, including transplantation date, patient age, gender, primary disease, graft source (relation, gender, and age), GVHD prophylaxis regimen, and conditioning intensity. The patients were followed prospectively for GVHD symptoms, onset, and severity until day +100. The acute GVHD grade was verified by chart review and recorded according to consensus criteria [16]. Assignment of acute GVHD grade was based on clinical manifestations as standard, and patients were categorized as GVHD Grade 0–I or Grade II–IV. As a result of confounding etiologies of nausea and/or anorexia during the post-transplant period, data from patients with upper-GI symptoms alone (i.e., no skin, liver, or lower-GI GVHD) were analyzed within the Grade 0–I group. In a secondary analysis, we included such cases in the Grade II–IV acute GVHD group.

mAb and flow cytometry

Fluorochrome-conjugated mouse anti-human mAb included anti-CD3, -CD4, -CD126, -pSTAT3 Y705 and -phosphorylated S6 ribosomal protein ser235/236 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA; eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA). Live events were acquired on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (FlowJo software, version 7.6.4; TreeStar, Ashland, OR, USA). The pSTAT3 and phosphorylated S6 gates were defined by an isotype control.

Measurement of pSTAT3

At 21 days following allograft infusion, a total of 30 ml heparinized peripheral blood was collected from asymptomatic patients. PBMCs were freshly isolated from patient and healthy volunteer blood (OneBlood) by gradient density over Ficoll-Paque PLUS (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA). To amplify STAT3 phosphoprotein detection, 1–3 × 106 PBMCs were pulsed or not with 4000 IU/ml IL-6 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) for 15 min in 1 ml serum-free RPMI (Corning Cellgro, Manassas, VA, USA) at 37°C [1, 2, 17]. The PBMCs were then treated directly with CytoFix (BD Biosciences), prewarmed to 37°C for 10 min. Following a wash with PBS, the PBMCs were permeabilized with ice-cold methanol (90% vol/vol) for at least 20 min at −20°C. The cells were stained for expression of CD3, CD4, and pSTAT3 Y705. The absolute numbers of STAT3+ CD4 and CD8 T cells were calculated by multiplying the fraction of each phosphorylated T cell subset among the patients’ absolute lymphocyte count on the day of blood draw.

Measurement of IL-6Rα

PBMCs were isolated from donor leukocyte concentrates of healthy volunteers (OneBlood). T cells were purified by use of nylon wool column elution and then stimulated with cytokine-matured autologous or allogeneic moDCs (DC:T cell ratio of 1:30) for 3 days, as described previously (Florida Blood Services, St. Petersburg, FL, USA) [1, 2, 17]. Resting T cells were included as a baseline control. CD4+ T cell surface expression of IL-6Rα (CD126) was evaluated by flow cytometry.

GVHD tissue IHC

Tissue samples were obtained upon diagnosis of GVHD from patients randomized to Rapa/TAC or MTXMTX/TAC in a GVHD prevention trial (NCT00803010) [14]. Subjects with acute GVHD, who had a diagnostic biopsy performed, were identified for this analysis. Biopsy was not mandated on protocol for GVHD diagnosis, and thus, included GVHD biopsy samples reflect usual clinical practice. IHC was performed to evaluate the phenotype of tissue-resident CD4+ T cells. Clinical acute GVHD severity was scored per standard criteria [16].

Pathologic GVHD grading was performed according to standard criteria by a pathologist blinded to the administered GVHD prophylaxis regimen. Biopsies were preserved in neutral-buffered formalin and processed in a usual manner. On the H&E-stained tissue sections, the portion of interest on each biopsy was outlined by the pathologist for incorporation into a TMA. Cylindrical punches were removed from paraffin-embedded tissue blocks to create a TMA, which was used to improve experimental uniformity and ensure highly parallel analysis.

Slides were stained by use of a Ventana Discovery XT automated system (Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, AZ, USA), per the manufacturer’s recommendations, with proprietary reagents. Antibodies to RORγ (rabbit, 1:300; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), T-bet (mouse, 1:25; BD Biosciences), FoxP3 (mouse, 1:25; Abcam), and CD4 (rabbit, 1:25; Cell Marque, Rocklin, CA, USA) were used for IHC. In brief, 4 µm sections were transferred to positively charged slides. The slides were deparaffinized on the automated system with EZ Prep solution (Ventana Medical Systems). Heat-induced antigen retrieval was performed in Cell Conditioning 1 (Ventana Medical Systems) for FoxP3 and T-bet and in RiboCC (Ventana Medical Systems) for CD4 and RORγ. The samples were then incubated with the selected antibodies by use of Dako antibody diluent (Carpenteria, CA, USA), followed by Ventana UltraMap anti-mouse or -rabbit secondary antibody. The Ventana ChromoMap kit detection system was used, and the slides were counterstained with hematoxylin. The slides were then dehydrated and coverslipped per normal laboratory protocol.

For the double stains, after-deparaffinization, heat-induced antigen retrieval was performed with Cell Conditioning 1. The samples were incubated first with the CD3 or IL-17 antibody, and then, the OmniMap anti-rabbit secondary antibody was applied. First, antibody detection used the Ventana ChromoMap kit. Then, the slides were subsequently incubated with RORγ antibody (1:200), followed by the UltraMap anti-rabbit multimer (Ventana Medical Systems) and the Alk Phos chromagen (Ventana Medical Systems). Finally, the slides were counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated, and coverslipped per normal laboratory protocol.

Stained slides were scanned by use of ScanScope XT (Aperio Technologies, Vista, CA, USA) with a 200×/0.75 NA objective lens at a rate of 3 min/slide via Basler Tri-linear array. Positivity for each marker was quantitatively scored by use of the TMA module of the TissueStudio version 3.0 software platform from Definiens (Munich, Germany) for each TMA core (0.6 mm diameter or 1.13 mm2 area). Staining intensity thresholds were held constant throughout the study. In a subset of 10 randomly selected TMA cores, contiguous sections (4 μm thickness) were stained with CD4 and RORγ for coregistration analysis. The negative pen tool was used on each core to segment manually the regions, which would not be scored, including the epithelium (Supplemental Fig. 1). RORγ was used to identify Th17, T-bet for Th1, and FoxP3 for Treg. A subset of cores were double stained for 1) RORγ and CD3 (n = 24) or 2) RORγ and IL-17 (n = 16) to confirm low background inclusion of ILC3 from our tissue analysis (CD3-negative, RORγ, or IL-17-positive) [18–21]. The double-stained cores were scanned by use of Aperio Technologies ScanScope XT with a 200×/0.8 NA objective lens with a 2× doubler (0.265 µm/pixel) at a rate of 10 min/slide via Basler Tri-linear array detection. The whole slide image (.svs) was loaded in ImageScope (Aperio Technologies), and the epithelium was excluded from the scoring. The resultant image was imported into Tissue Studio v3.0 (Definiens) and segmented as described above. Within the specific region of interest indicated by the study pathologist (E.M.S.), individual cells were identified by use of hematoxylin thresholding (0.2) and an IHC threshold for both red (0.85) and brown (0.35) staining. The typical nucleus size was set to be 60 µm2, and the cells were grown (cell simulation at 2 µm) in every direction. A nucleus size of 60 µm2 was used to exclude IL-17+ mast cells from the double-stained cores [22, 23]. Cells were binned into 4 categories based on the IHC stain intensity: negative, red-only-positive (CD3 or IL-17, respectively), brown-only (RORγ)-positive, or double-stained for both red and brown stain.

Akt-mTOR-S6 versus IL-6-STAT3 signaling among random donor T cells

T cells were serum starved in RPMI, treated with DMSO diluent control, Rapa 100 ng/ml (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), or STAT3i S3I-201 50 µM (H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center, Drug Discovery Core, Tampa, FL, USA) for 4 h. For the STAT3 experiments, the T cells were first DC allostimulated (DC:T cell ratio of 1:30) for 3 days to optimize surface expression of IL-6Rα and STAT3 signaling among healthy volunteers. The T cells were then cytokine pulsed for 15 min with IL-2 (R&D Systems) to activate the Akt-mTOR-S6 pathway or IL-6 to stimulate pSTAT3. The cells were then fixed and permeabilized as described and then stained for CD3, CD4 (STAT3 experiments), pSTAT3 Y705, and phosphorylated S6.

RORγt expression by RT-PCR

To optimize the detection of RORγt expression, CD4+ T cells were isolated by magnetic bead-negative selection (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA, USA). The human CD4+ T cells were then stimulated with cytokine-matured, allogeneic moDCs (DC:T cell ratio of 1:30) for 5 days, as described previously (Florida Blood Services) [1, 2, 17]. The allogeneic cocultures were treated with DMSO, Rapa 10 ng/ml, or S3I-201 5 or 50 μM, or both inhibitors at low doses were added once on day 0. The media were supplemented with IL-6 (105 IU/ml), TGF-β(4 ng/ml; R&D Systems), and anti-IFN-γmAb (10 μg/ml; eBioscience) to promote RORγt polarization. After the 5-day culture, the T cells were harvested. Total RNA was extracted by use of Trizol (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. cDNA was synthesized by use of the SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System (Life Technologies). RT-PCR was carried out on an ABI 7900 instrument (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and performed as described by Ratajewski et al. [24] with some modification by use of SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Life Technologies) as follows: 10 min at 95°C and then 45 cycles each at 95°C for 15 s, 59°C for 45 s, and 72°C for 10 s. The following primers were used: RORγt forward 5′- CTGCTGAGAAGGACAGGGAG -3′ and reverse 5′- AGTTCTGCTGACGGGTGC -3′; GAPDH forward 5′- ACCACAGTCCATGCCATCAC -3′ and reverse 5′- TCCACCACCCTGTTGCTGTA -3′. PCR product purity was assessed by dissociation curves. The differences in gene expression were calculated by 2ΔΔ comparative threshold in triplicate. Data were normalized to GAPDH expression.

alloMLR

Primary alloMLR

Bulk donor T cells were allostimulated with cytokine-matured, allogeneic moDCs at a DC:T cell ratio of 1:30, as described previously (Florida Blood Services) [1, 2, 17]. Rapa (10 ng/ml), with or without S3I-201 (500 nM–50 μM), or DMSO diluent control, was added once only on day 0. Lower doses of each drug were used in these experiments to mimic expected physiologic concentrations [25, 26] and to better detect potential synergistic activity with the combination of Rapa and S3I-201. After 5 days of culture at 37°C, T cell proliferation was measured by a colorimetric assay, per the manufacturer’s instructions {CellTiter 96 AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay (3-[4,5,dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-5-[3-carboxymethoxy-phenyl]-2-[4-sulfophenyl]-2H-tetrazolium); Promega, Madison, WI, USA} [1, 2, 17]. Absorbance/OD was analyzed at 490 nm.

Secondary alloMLR

T cells were first DC allostimulated (DC:T cell ratio of 1:30) for 5 days with no vehicle or drugs added. Following priming, the T cells were then rested and recultured with fresh, first-party moDCs (DC:T cell ratio of 1:30). DMSO, Rapa (10 ng/ml), S3I-201 (5 or 50 μM), or Rapa (10 ng/ml) with S3I-201 (5 μ m) was added once on day 0 of the secondary alloMLR. After 3 days, T cell proliferation was measured by a colorimetric assay, as described (Promega). T cells alone and PHA-stimulated T cells served as negative and positive controls, respectively, for the primary and secondary alloMLRs.

Statistical analysis

Statistical differences in patient characteristics were determined by Fisher exact test for proportions. ROC curves evaluated the sensitivity and specificity of pSTAT3 with regard to acute GVHD onset. A cut-point of 48% pSTAT3 among the CD4+ T cells was selected to distinguish those at risk to develop Grade II–IV acute GVHD by day +100 to maximize the area under the ROC curve. The cumulative incidence rate of Grade II–IV acute GVHD was estimated among those with <48% and ≥48% CD4+ pSTAT3, where death and relapse were considered competing risks. The Gray method was used to evaluate the difference in incidence rates between the 2 groups [27]. GVHD IHC data are presented as absolute numbers for each and ratio of each to total CD4+ cells. For comparisons of matched data sets, the paired t-test was used. For comparisons of independent data sets, the unpaired Student's t-test or Mann-Whitney test was used, based on Gaussian distribution. ANOVA was used for group comparisons. The log transformation was taken to meet the assumptions for ANOVA. Logistic regression analysis was used to study the association between lymphocyte subset numbers and response to primary GVHD systemic glucocorticoid therapy. The statistical analysis was conducted by use of SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and Prism software, version 5.04 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Statistical significance was defined by P < 0.05.

RESULTS

pSTAT3 identifies those patients at risk for acute GVHD

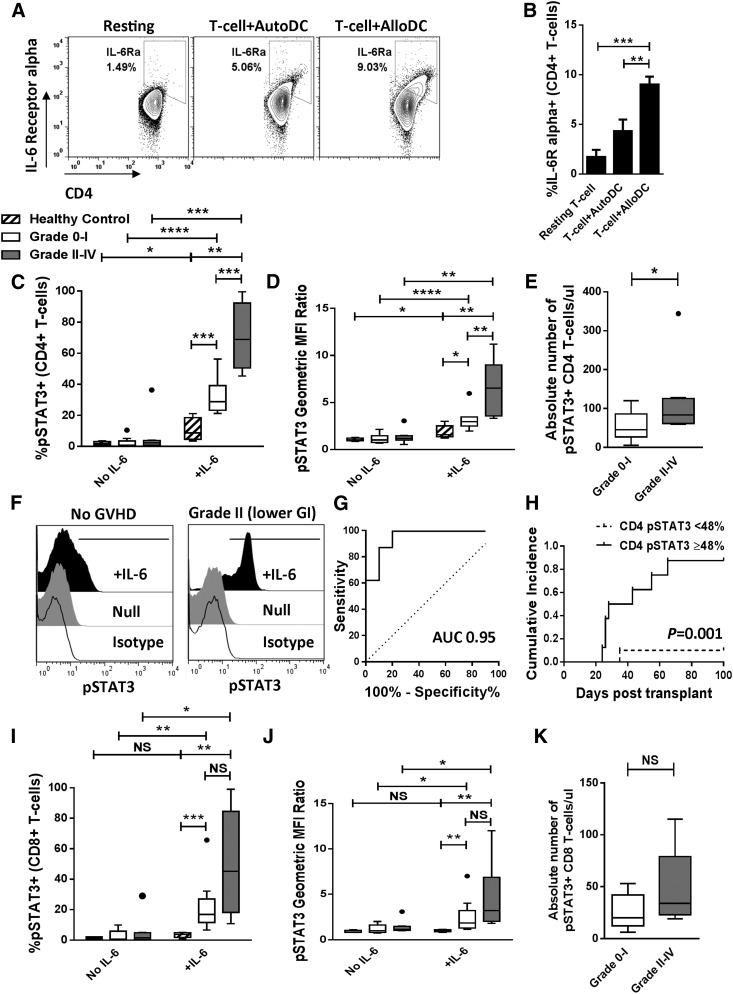

We found that DC allostimulation significantly increases the surface expression of the IL-6Rα subunit on healthy donor CD4+ T cells compared with resting state or autologous DC stimulation (Fig. 1A and B). To study this observation functionally in the setting of allogeneic HCT, we measured IL-6-induced pSTAT3 in T cells from patients before the onset of acute GVHD. A total of 18 patients consented to pSTAT3 Y705 quantification on day +21 (±2 days) and subsequent monitoring for GVHD onset until day +100 at the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center. None of the enrolled patients demonstrated any signs of acute GVHD at the time of the day +21 peripheral blood collection. Patient characteristics, clinical variables, and outcomes are summarized in Table 1. The median time of Grade II–IV acute GVHD onset was 36 (24–65) days. All cases of acute GVHD occurred before day +100, even when the monitoring period was extended to day +180 to capture potential incidences of late acute GVHD.

Figure 1. CD4+ T cell pSTAT3 identifies those at risk for acute GVHD.

(A and B) Representative contour plots and bar graph (means from 3 independent experiments) depict CD4+ T cell surface expression of IL-6Rα in response to resting state, 3-day autologous (AutoDC), or 3-day allogeneic (AlloDC) stimulation. (C–E) Box and whisker plots demonstrate pSTAT3 (percent, geometric MFI ratio, and absolute number) among CD4+ T cells at day +21 following allogeneic HCT, based on development of Grade II–IV acute GVHD by day +100 (Grade 0–I, n = 10; Grade II–IV, n = 8). Healthy volunteer data are included as a reference control (n = 5). (F) Representative histograms show CD4+ T cell pSTAT3 at day +21 in a patient that never acquired GVHD and a patient that later developed Grade II lower-GI acute GVHD at day +43. (G) ROC curves depict the sensitivity and specificity of day +21 percent STAT3 activation among CD4+ T cells (AUC 0.95) as a test to identify those at risk to develop acute GVHD. (H) Cumulative incidence of acute GVHD stratified by degree of CD4+ T cell pSTAT3 at day +21 postallogeneic HCT. Gray method was used to evaluate the difference in incidence rates between the 2 groups. (I–K) Box and whisker plots demonstrate pSTAT3 (percent, geometric MFI ratio, and absolute number) among CD8+ T cells at day +21 following allogeneic HCT, based on development of Grade II–IV acute GVHD by day +100. NS, Not significant; *P < 0.05, **P = 0.001—0.01, ***P = 0.0001–0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics and outcomes of patients where pSTAT3 was measured on day +21

| Characteristic | GVHD Grade 0–I (n = 10) | GVHD Grade II–IV (n = 8) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 57.6 (37–70) | 51.7 (33–70) | NS |

| Gender | 4 Female, 6 male | 3 Female, 5 male | NS |

| Primary disease | NS | ||

| Acute myelogenous leukemia | 7 | 0 | |

| Myelodysplasia | 2 | 1 | |

| Myeloproliferative neoplasm | 0 | 1 | |

| Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | 1 | 2 | |

| Chronic myelogenous leukemia | 0 | 1 | |

| Chronic lymphocytic leukemia | 0 | 0 | |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 0 | 2 | |

| Multiple myeloma | 0 | 1 | |

| Conditioning | NS | ||

| Myeloablative | 7 | 3 | |

| Reduced intensity | 3 | 5 | |

| GVHD prophylaxis | NS | ||

| Rapa/TAC | 8 | 5 | |

| MTX/TAC | 1 | 2 | |

| Mycophenolate mofetil/TAC | 1 | 1 | |

| Graft source | N/A | ||

| Peripheral blood stem cells | 10 | 8 | |

| Marrow | 0 | 0 | |

| Donor relation | NS | ||

| HLA-matched related | 2 | 4 | |

| HLA-matched unrelated | 8 | 4 | |

| Female donor → male recipient | 2 | 1 | |

| Acute GVHD Grade II–IV | N/A | N/A | |

| II | 6a | ||

| III | 1b | ||

| IV | 1c |

NS, Not significant; NA, not applicable.

Four patients with Stage 1 lower GI acute GVHD; 2 patients with Stage 3 skin acute GVHD.

One patient with Stage 4 lower GI acute GVHD.

One patient with Stage 4 skin acute GVHD.

Patients that developed Grade II–IV acute GVHD (n = 8) by day +100 demonstrated a significant increase in pSTAT3 Y705 among CD4+ T cells pulsed with IL-6 compared with healthy volunteers (n = 5) or patients with Grade 0–I acute GVHD (n = 10; Fig. 1C and D). Following IL-6 stimulation, the percentage of pSTAT3+ CD4+ T cells, relative intracellular pSTAT3 density (pSTAT3 geometric MFI ratio normalized to isotype-negative control autofluorescence), and absolute number of IL-6-responsive pSTAT3+ CD4+ T cells was increased significantly in patients who eventually developed acute GVHD (Fig. 1C–F). The absolute number of total CD4+ T cells was similar between both groups of patients (Supplemental Fig. 2A). The amount of STAT3 activation did not directly correlate with the grade-wise severity or rapidity of GVHD onset during the 100 days following allogeneic HCT.

ROC curves were generated to test the ability of CD4+ T cell pSTAT3 Y705 to discriminate between those with and without Grade II–IV acute GVHD by day +100. The AUC for percent STAT3 activation among CD4+ T cells was 0.95 (Fig. 1G), and 0.87 for the pSTAT3 geometric MFI ratio. A cut-off point of 48% pSTAT3 Y705 among CD4+ T cells demonstrated a test sensitivity of 87.5% and specificity of 90% with a likelihood ratio of 8.75. Although patients with nausea and/or anorexia alone were analyzed within the Grade 0–I group to minimize confounding etiologies, a secondary analysis demonstrated similar results when these patients were considered to have Grade II upper-GI GVHD (CD4+ percent pSTAT3+, P = 0.02 with AUC of 0.84; pSTAT3 geometric MFI ratio, P = 0.01 with AUC of 0.84).

With the use of the selected cut-off point of 48% STAT3 activation among CD4+ T cells, the cumulative incidence of Grade II–IV acute GVHD was estimated for patients with percent pSTAT3+ Y705 values <48% and ≥48%. This approach significantly stratified those at risk to develop Grade II–IV acute GVHD, based on the enhanced degree of STAT3 activation at day +21 before clinical recognition of alloreactivity (Fig. 1H). The degree of pSTAT3 among CD8+ T cells was similar between those with or without GVHD, although both patient groups showed greater STAT3 activity than the healthy volunteers (Fig. 1I and J). The absolute number of IL-6-responsive pSTAT3+ CD8+ T cells and total CD8+ T cells was not statistically different between those with or without acute GVHD (Fig. 1K and Supplemental Fig. 2B).

The amount of tissue-resident Th17 correlates with GVHD severity, Rapa GVHD prophylaxis, and glucocorticoid response

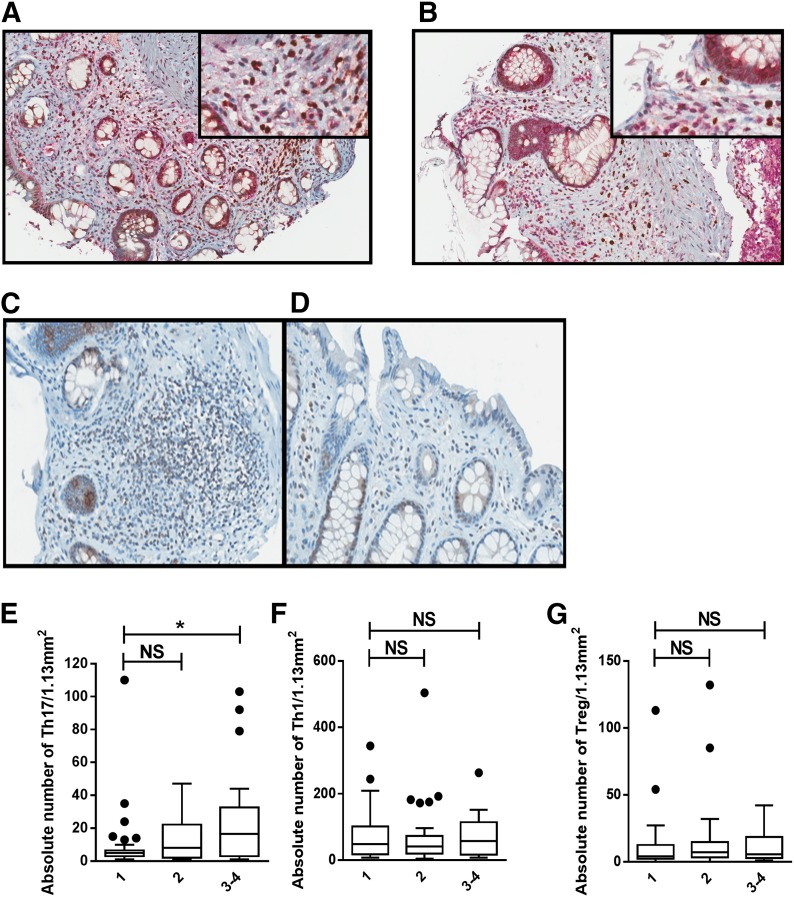

Based on the observed increase in CD4+ T cell pSTAT3 before acute GVHD onset, we went on to investigate whether this led to subsequent Th17 cell-tissue invasion of acute GVHD target organs. A total of 48 patients contributed 110 GVHD biopsies to the analysis. These samples were obtained from patients randomized to Rapa (n = 25) or MTX (n = 23) in a GVHD prevention trial (NCT00803010) [14]. Acute GVHD organ biopsy sites, as well as clinical and pathologic grade are represented in Table 2. GVHD diagnostic biopsies were not required by protocol, and all available biopsies were included in this analysis. Whereas the total Rapa-treated study population had a reduction in Grade II–IV acute GVHD [14], the clinical grade distribution presented reflects that of biopsied patients. A comparison of GVHD-affected patients, according to biopsy status, is presented in Supplemental Table 1. Time from GVHD biopsy to topical (P = 0.17) or systemic glucocorticoid (P = 0.55) therapy did not differ between Rapa- and MTX-treated patients. RORγ and CD4 coregistration analysis demonstrated that the majority of RORγ+ cells was dual positive for CD4 (median 98%, range 89–99.6%). There was a low background of ILC3 cells in a subset of patients (n = 24) who had cores dually stained for CD3 and RORγ. ILC3 (CD3-negative, RORγ+) only comprised an average of 6.3% of total RORγ+ cells (Fig. 2A). We also observed a high degree of RORγ/IL-17 coexpression among the dual-stained cores (Fig. 2B). Thus, Th17 was subsequently defined by RORγ positivity. Th17 increased (median values, Grade 1: 5; Grade 2: 8; Grade 3: 20.5) with pathologic grade. ANOVA adjusted for the GVHD organ site demonstrated that Th17 (P = 0.033) was significantly associated with pathologic grade (Fig. 2C–E). No other cell subsets were associated with pathologic grade (Fig. 2F and G).

TABLE 2.

GVHD organ involvement, pathologic, and clinical grade

| Sample | Rapa (%) | MTX (%) | Total (%) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pathologic grade | ||||

| 1 | 23 (38.3) | 15 (31.9) | 38 (35.5) | NS |

| 2 | 26 (43.3) | 21 (44.7) | 47 (43.9) | |

| 3 | 11 (18.3) | 9 (19.1) | 20 (18.7) | |

| 4 | 0 (0) | 2 (4.3) | 2 (1.9) | |

| Total | 60 (56.1) | 47 (43.9) | 107 (100) | |

| Biopsy organ site | ||||

| Gastric antrum | 15 (23.8) | 12 (25.5) | 27 (24.5) | NS |

| Duodenum | 18 (28.6) | 12 (25.5) | 30 (27.3) | |

| Rectum | 19 (30.2) | 15 (31.9) | 34 (30.9) | |

| Liver | 1 (1.6) | 2 (4.3) | 3 (2.7) | |

| Skin | 10 (15.9) | 6 (12.8) | 16 (14.5) | |

| Total | 63 (57.3) | 47 (42.7) | 110 (100.0) | |

| Clinical gradea | ||||

| 1 | 9 (36) | 0 (0) | 9 (19) | <0.001 |

| 2 | 11 (44) | 21 (91) | 32 (67) | |

| 3 | 4 (16) | 2 (9) | 6 (13) | |

| 4 | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | |

| Total | 25 (52) | 23 (48) | 48 (100) |

Rapa, Rapa/TAC GVHD prophylaxis group; MTX, MTX/TAC GVHD prophylaxis group.

Clinical-grade distribution reflects that of the represented biopsies, not the grade distribution of the total parent study population. Biopsies were not mandated per protocol and thus, were obtained per treating clinicians’ judgment. Clinical-grade distribution presented for patient-level data (number of patients for each overall clinical grade), whereas pathologic grade and biopsy site represent individual biopsy-level data. Overall grade distribution across study groups (Rapa vs. MTX) compared by use of Fisher exact test. Separate comparison of Grade 1/2 versus 3/4 showed no significant difference (P = 0.42).

Figure 2. Tissue-resident Th17 cells are associated with severity of GVHD pathologic grade.

(A) Coexpression of CD3 (red) and RORγ (brown) is shown in a representative biopsy image, confirming the exclusion of ILC3 (CD3-negative, RORγ+; original magnification, ×200; inset, ×400). (B) Coexpression of IL-17 (red) and RORγ (brown) is shown in a representative biopsy image (original magnification, ×200; inset, ×400). (C) Increased RORγ+ lymphocytes in a rectal biopsy from a patient with pathologic Grade 3 GVHD. (D) Fewer RORγ+ lymphocytes in a rectal biopsy from a patient with pathologic Grade 1 GVHD (RORγ, ×400). Box and whisker plots show absolute number of tissue-resident Th17 (E), Th1 (F), and Treg (G) by pathologic GVHD grade (Grade 1, n = 33; Grade 2, n = 30; Grade 3–4, n = 18). *P < 0.05.

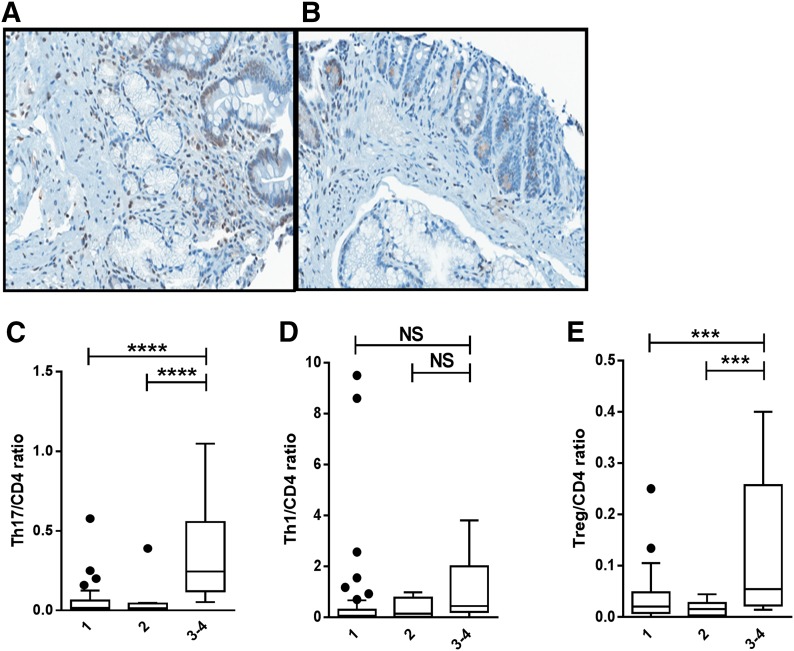

An analysis of GI clinical stage, with an ANOVA adjusted for GI organ involvement, demonstrated that the Th17/CD4 and Treg/CD4 ratios increased with greater GI organ stage (Fig. 3A-C and E). Th1 tissue deposition was not associated with GI GVHD stage (Fig. 3D). There were too few biopsies of skin and liver for organ-specific analysis.

Figure 3. The target-organ Th17/CD4+ and Treg/CD4+ T cell ratios are increased in clinical Stage 3 or 4 GI GVHD.

(A) Increased RORγ+ lymphocytes in a duodenal biopsy from a patient with clinical Stage 3 acute GVHD. (B) Fewer RORγ+ lymphocytes in a duodenal biopsy from a patient with clinical Stage 1 acute GVHD (RORγ, ×400). Box and whisker plots show ratio of tissue-resident Th17/CD4+ (C), Th1/CD4+ (D), and Treg/CD4+ (E) T cells by GI GVHD clinical stage (Stage 1, n = 66; Stage 2, n = 10; Stage 3–4, n = 6). ***P = 0.0001–0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

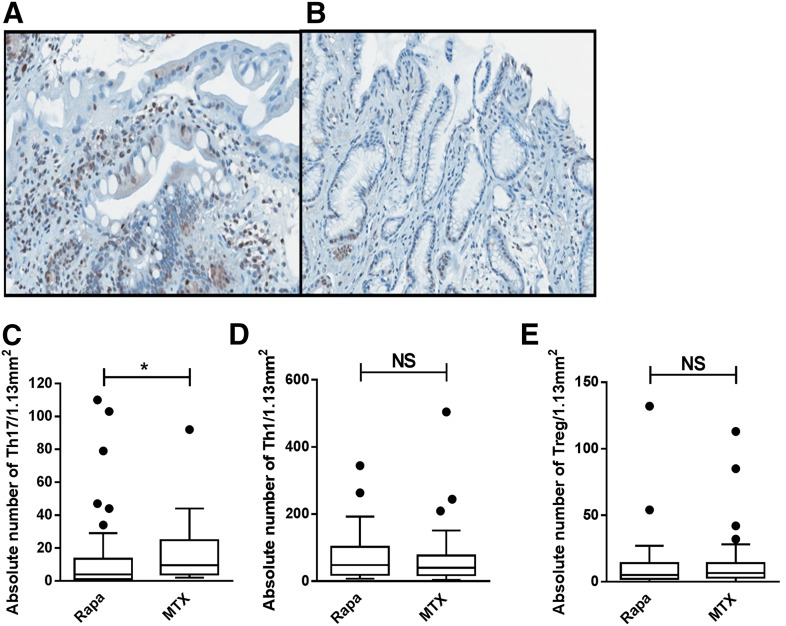

Rapa-treated patients had significantly lower Th17 cells than those treated with MTX (Fig. 4A–C). Adjusted for clinical and pathologic grade, Rapa remained significantly associated with lower Th17 (P = 0.04). Other lymphocyte subsets did not differ between Rapa and MTX treatment (Fig. 4D and E).

Figure 4. Target-organ Th17 cells are reduced among those receiving Rapa GVHD prophylaxis.

(A) Increased RORγ+ lymphocytes in the duodenal lamina propria from a patient receiving MTX. (B) Fewer RORγ+ lymphocytes in the duodenal lamina propria of a patient receiving Rapa. Both patients were diagnosed with pathologic Grade 2 GVHD (RORγ, ×400). Box and whisker plots show absolute number of tissue-resident Th17 (C), Th1 (D), and Treg (E) by use of Rapa or MTX GVHD prophylaxis (Rapa, n = 45; MTX, n = 37). Line depicts median. *P < 0.05.

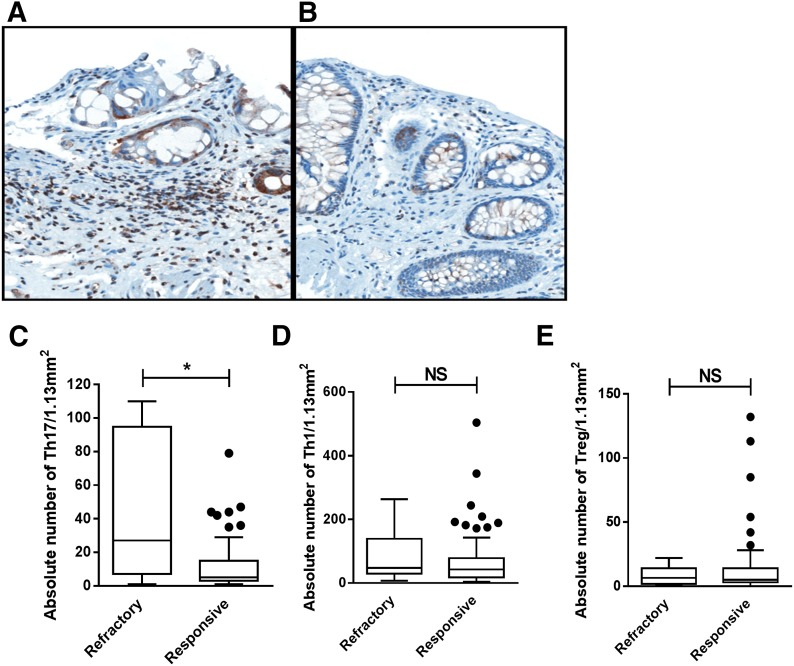

Refractoriness to standard, initial acute GVHD therapy (≥1 mg/kg/day prednisone or equivalent) was defined as lack of complete or partial response by 28 days of therapy, as this is a validated predictor of subsequent nonrelapse mortality [28]. Those with refractory acute GVHD had a significantly increased number of Th17 present in affected tissues compared with responsive (median 27 vs. 5; Fig. 5A–C). Logistic regression analysis demonstrated that tissue Th17 was significantly associated with glucocorticoid refractoriness (OR 6.6, 95% CI 1.6–27, P = 0.008), as was overall clinical GVHD grade (Grade 3–4 vs. 2: OR 6.3, 95% CI 1.7–23.0, P = 0.01). Th17 was also significantly associated with refractoriness in a subgroup analysis limited to GI involvement. Other lymphocyte subsets were not associated with glucocorticoid refractoriness (Fig. 5D and E).

Figure 5. Tissue-resident Th17 cells are increased in the target organs of those with steroid-refractory acute GVHD.

(A) Increased RORγ+ lymphocytes in the lamina propria from a rectal biopsy. Patient was diagnosed with pathologic Grade 3 GVHD and was refractory to steroid therapy. (B) Fewer RORγ+ lymphocytes in the lamina propria on rectal biopsy. Patient was diagnosed with pathologic Grade 2 GVHD in the rectum and was responsive to steroid therapy (RORγ, ×400). Box and whisker plots show absolute number of tissue-resident Th17 (C), Th1 (D), and Treg (E) by response to corticosteroid therapy (refractory, n = 10; responsive, n = 71). Line depicts median. *P < 0.05.

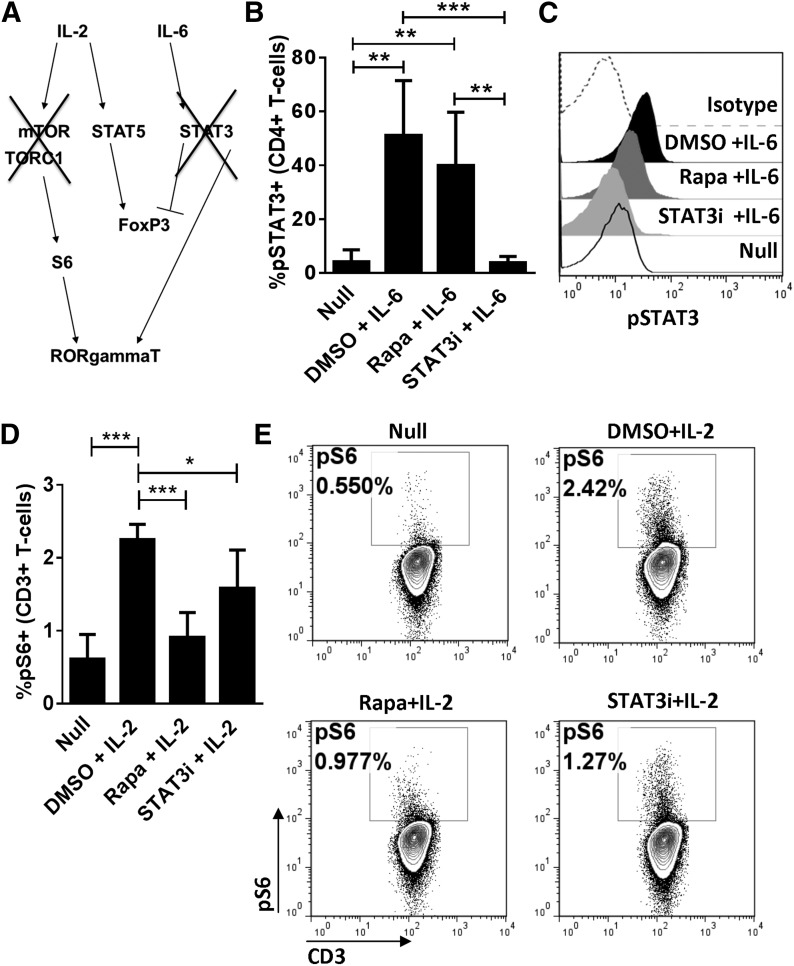

Differential effects of S3I-201 and Rapa on mTOR and STAT3 signaling

Whereas Rapa-based immune suppression is associated with a reduction in tissue-resident Th17 during acute GVHD, it incompletely protects HCT recipients from alloreactivity [14]. Rapa inhibits the pSTAT3 Ser727 motif but does not affect the Y705 motif that is important for RORγt transcription [12, 29]. In contrast, S3I-201 predominantly inhibits the pSTAT3 Y705 motif and much less the Ser727 motif [12, 25, 29]. Therefore, we investigated the differential effects of Rapa and S3I-201 on the Akt-mTOR-S6 and STAT3 signaling pathways (Fig. 6A). In agreement with our previously published work [2], S3I-201 significantly decreased IL-6-mediated pSTAT3 of Y705 in cytokine-pulsed T cells from healthy random donors (Fig. 6B and C). As expected, mTOR inhibition with Rapa demonstrated little effect on pSTAT3 Y705 (Fig. 6B and C) but significantly decreased mTOR-dependent S6 signaling in IL-2-stimulated T cells (Fig. 6D and E). S3I-201 modestly reduced S6 activation (Fig. 6D and E). These data demonstrate that STAT3 inhibition does not completely suppress mTOR activation, and mTOR inhibition does not suppress pSTAT3. This suggests that suppression of both pathways is required to inhibit RORγt expression.

Figure 6. Differential effects of S3I-201 and Rapa on mTOR and STAT3 Y705 signaling.

(A) Signaling schema of mTOR and STAT3 Y705 pathways that converge upon RORγt. Human T cells were DC allostimulated for 3 days to optimize STAT3 signaling. T cells were harvested and serum starved in the presence of DMSO, Rapa 100 ng/ml, or STAT3i (S3I-201), 50 μM for 4 h and then pulsed with IL-2 or IL-6 to induce S6 ribosomal protein phosphorylation or pSTAT3 Y705, respectively. (B) The means ± sd from 5 independent experiments show that Rapa has a negligible effect on pSTAT3 Y705 (the residue associated with RORγt expression), although Y705 is susceptible to STAT3i. (C) Representative histograms show the effect of mTOR and STAT3 blockade on STAT3 activation. (D) The means ± sd from 5 independent experiments demonstrate that Rapa significantly suppresses S6 [phosphorylated S6 (pS6)], whereas STAT3i imparts partial inhibition. (E) Representative contour plots show the impact of mTOR and STAT3 blockade on S6 signaling. *P < 0.05, **P = 0.001–0.01, ***P = 0.0001–0.001.

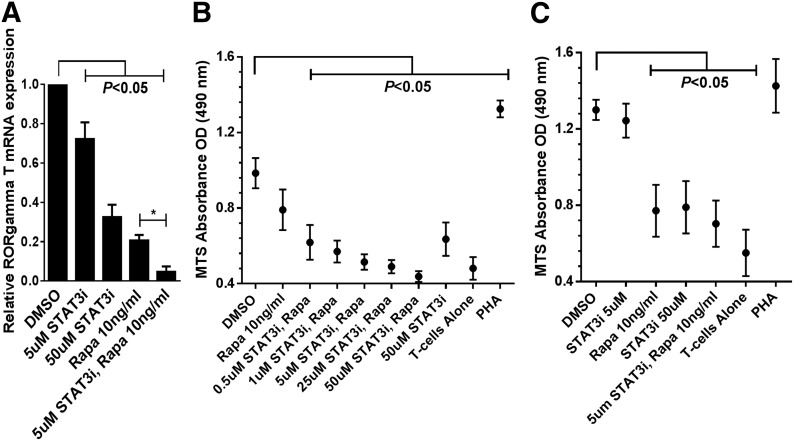

Dual STAT3/mTOR inhibition exerts enhanced control over RORγt expression and alloreactivity

To investigate the effect of dual STAT3 and mTOR inhibition on RORγt expression, moDC-allostimulated CD4+ T cells were exposed to DMSO, S3I-201, Rapa, or both inhibitors. STAT3 and mTOR inhibition independently demonstrated significant suppression of RORγt compared with DMSO diluent control (Fig. 7A). Moreover, the combination of clinically relevant concentrations of Rapa (10 ng/ml) and S3I-201 (5 μM) achieved superior inhibition of RORγt compared with Rapa or S3I-201 alone (Fig. 7A).

Figure 7. Dual STAT3/mTOR inhibition exerts enhanced control over RORγt and alloreactivity.

(A) Purified CD4+ T cells were stimulated with allogeneic moDCs for 5 days with DMSO, Rapa (10 ng/ml), STAT3i (5 or 50 μM), or both inhibitors. Media were supplemented with IL-6, TGF-β, and anti-IFN-γ mAb to enhance RORγt detection. Bar graph depicts the triplicate means ± sem from 3 independent experiments evaluating the relative RORγt expression in response to mTOR, STAT3, or dual-pathway blockade. (B) Five day alloMLRs (DC:T cell ratio 1:30) treated with a fixed dose of Rapa (10 ng/ml), with or without varying concentrations of STAT3i (500 nM–50 μM), or DMSO diluent control, with all drugs added once on day 0. T cell proliferation was measured by a colorimetric assay. Graph shows the triplicate means ± sem of the OD (analyzed at 490 nm) from 4 independent experiments. (C) Untreated primary, 5 day alloMLR, followed by 3 day restimulation with first-party allogeneic moDCs in the presence of Rapa (10 ng/ml). with or without STAT3i (5 or 50 μM), or DMSO diluent control, with all drugs added once on day 0. T cell proliferation was measured by a colorimetric assay. Graph shows the triplicate means ± sem of the OD (490 nm) from 3 independent experiments. *P < 0.05.

Primary, 5 day alloMLRs (moDC:T cell ratio of 1:30) were treated with a low, fixed dose of Rapa (10 ng/ml) combined with varying concentrations of S3I-201 (500 nM–50 μM). This approach was taken to best approximate physiologic drug levels [25, 26] and to optimize detection of any enhanced efficacy by dual STAT3/mTOR inhibition. S3I-201 (50 μM) significantly reduced allostimulated T cell proliferation, as described previously [2]. Additionally, our prior work demonstrated that concentrations of S3I-201 below 50 μM had no effect on alloreactive T cell proliferation as a single agent [2]. Rapa alone modestly affected the alloresponse (P = 0.06; Fig. 7B). However, significant control over the alloresponse was achieved when S3I-201 was added to Rapa, even at nanomolar concentrations of the STAT3i (Fig. 7B). Either Rapa (10 ng/ml) or S3I-201 (50 μM) alone significantly suppressed T cell proliferation when added to primed T cells during rechallenge with fresh, original allogeneic moDCs. Unlike T cells responding to primary allostimulation, enhanced immune suppression was not observed when Rapa (10 ng/ml) and S3I-201 (5 μM were added to the secondary alloMLR (Fig. 7C).

DISCUSSION

This investigation proposes that STAT3 pathway activation and Th17 tissue invasion are clinically relevant to the pathogenesis of human acute GVHD. DC allostimulation significantly increases the surface expression of the IL-6Rα subunit. In a cohort of asymptomatic, allogeneic HCT recipients, we showed that pSTAT3 Y705 in circulating CD4+ T cells is increased significantly by IL-6 in patients who later develop Grade II–IV acute GVHD by day +100. Additionally, T cell STAT3 activation is increased by IL-6 among all HCT patient groups compared with healthy volunteers.

STAT3 signaling is critical for RORγt expression and consequent Th17 polarization. Accordingly, at the time of acute GVHD diagnosis, we observed a marked abundance of Th17 cells within the tissues of biopsied target organs. We were careful to exclude the epithelium from all tissue analyses to avoid RORγ staining from non-Th17 cells. Moreover, we confirmed that ILC3 cells (CD3-negative, RORγ+ and/or IL-17-positive) comprised a minimal population (6.3%) within the biopsy field of interest by use of the described double-staining procedure, as they similarly express CD4, RORγ, and IL-17 [18–21]. Given that diagnostic tissues were acquired in the setting of a randomized trial, comparing Rapa with MTX for GVHD prevention [14], we were able to demonstrate that mTOR inhibition significantly reduced the amount of Th17 cells in the involved target organs.

Among the cohort of patients studied at day +21 after allogeneic transplant in this pilot investigation, the degree of pSTAT3 induced by IL-6 was linked to the eventual onset of acute GVHD. A cut point of 48% pSTAT3 within the CD4+ T cells significantly stratifies those at greatest risk of acquiring acute GVHD. For those with <48% STAT3 activation, only 10% of patients developed this post-transplantation complication. Moreover, all of the observed patients with >48% pSTAT3 developed Grade II–IV acute GVHD by day +100. Of note, the amount of phosphoprotein expression did not correlate directly with specific grade-wise assignment, rapidity of disease onset, or specific organ involvement of the observed GVHD. Recently, others have also shown that T cell STAT3 activity is increased significantly in patients with SLE [30]. Taken together, these observations made in acute GVHD and SLE identify STAT3 activation on T cells as an important factor in human immune-mediated disease.

Rapa inhibition of mTOR signaling was associated with a reduction in Th17 burden at the time of GVHD diagnosis. In mice, mTOR activation is linked to RORγt transcript migration by way of downstream phosphorylation of S6 ribosomal protein [12]. Interestingly, mTOR inhibition in mice does not affect expression of RORγt by the RORC gene [12]. Additionally, Rapa is unable to control STAT3-mediated expression of RORγt [29]. Whereas Rapa does suppress the Ser727 residue of STAT3, it fails to impede signaling via the Y705 motif [29]. Phosphorylation of Y705 is required for Th17 differentiation [29]. Our data in humans did show partial inhibition of S6 phosphorylation by S3I-201. Selective inhibitors of upstream JAK2 have demonstrated this effect as well [31, 32], suggesting that STAT3 may play a modest role in S6 signaling. Moreover, we demonstrate that the most efficient means to prevent RORγt expression in human T cells is achieved through combined inhibition of mTOR and STAT3 activation.

We observed superior control over alloreactive T cells when low physiologic concentrations of Rapa and S3I-201 were combined in primary alloMLRs (>95% inhibition with Rapa 10 ng/ml plus S3I-201 5 μM compared with DMSO; Fig. 7B). Whereas single-agent Rapa (10 ng/ml) or S3I-201 (50 μM) partially inhibited the proliferation of primed T cells in secondary alloMLRs (69% and 67% inhibition compared with DMSO, respectively; Fig. 7C), enhanced suppression was not achieved with concurrent pathway blockade in this setting. This suggests that STAT3 inhibition overcomes Rapa resistance during the initial T cell:moDC encounter. Conversely, alternative activation mechanisms may drive the primed alloresponse despite the inhibition of STAT3 and/or mTOR signaling. Others have shown that phosphatase and tensin homolog is reduced in DC-primed, memory T cells, which could potentially worsen Rapa resistance during the secondary response [33].

The hypothesis that Th17 contributes to acute GVHD is supported by the significant increase in STAT3 activation among CD4+ T cells in patients who go on to develop acute GVHD, and the amount of Th17 cells was significantly associated with pathologic grade, clinical stage of GI GVHD, and poor response to upfront glucocorticoids. These findings indicate a potential association between STAT3 activation before GVHD onset and the resultant deposition of Th17 cells among the involved GVHD target organs. Others have reported a lack of an association between Th17 tissue deposition and acute GVHD onset [34, 35]. These divergent findings may be explained by our current use of RORγt as a selective marker to identify Th17 within the target tissues. Conversely, others stained acute GVHD biopsy samples for the IL-17 cytokine [34, 35], as opposed to the more specific transcription factor responsible for Th17 differentiation. In agreement with existing published work, we demonstrate that tissue-resident Tregs are present in the GI mucosa at the time of acute GVHD onset [36]. Moreover, we show that the ratio of Treg/CD4 T cells is increased in higher clinical stages of acute GVHD.

As opposed to typical, broad immune suppression, our prior work demonstrated that selective STAT3 inhibition significantly expanded Tregs, while preserving nonalloreactive effector T cell function. Rapa promotes Treg potency and growth while suppressing conventional T cells [26, 37, 38]. A natural translation of these findings includes GVHD prevention clinical trials, which incorporate dual mTOR and STAT3 inhibition. At present, STAT3 may be targeted at multiple signaling levels with available pharmacologic agents. This includes relevant cytokine inhibition (such as IL-6 or IL-23) [39, 40], upstream JAK2 blockade [1], or direct suppression of STAT3 activation [2]. One approach is adding ustekinumab [41], a mAb targeting the p40 cytokines to Rapa. The p40 cytokines include IL-12 and IL-23, where the latter uses a STAT3-dependent signaling mechanism [39, 42, 43]. Whereas ustekinumab is U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved for the treatment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis [41], we have previously reported a case where it demonstrated efficacy in treating refractory GVHD [40]. Whereas our current investigation did not correlate tissue-resident Th1 cells with acute GVHD severity or clinical outcome, this work does not eliminate a potential therapeutic benefit in targeting alloreactive Th1 cells, which may participate in the development of acute GVHD more systemically as opposed to acting directly within the biopsied target organs or at time-points earlier than we assessed in this study. Such clinical considerations deserve further research, given that others have identified Th1-related signals early in the development of human acute GVHD [44].

Our present work highlights several innovative concepts in transplant medicine. First, we propose that that STAT3 activity and up-regulation of RORγt occur early in the post-transplant course. pSTAT3 Y705 may identify patients at risk to develop acute GVHD before clinical recognition of the syndrome. Second, we show that Th17, identified by RORγt staining, is abundant in the target organs of those diagnosed with severe acute GVHD. Moreover, this burden of Th17 cells is associated with a poor, upfront response to standard glucocorticoid therapy. Lastly, we show that concurrent blockade of mTOR and STAT3 efficiently optimizes control over RORγt expression in human T cells. Future investigations will focus on validating the association of STAT3 activation in acute GVHD risk by use of a large, independent cohort of patients. Moreover, the targeting of the STAT3 and mTOR pathways may abort acute GVHD progression by avoiding Th17 polarization and minimizing the risk of a steroid-refractory disease.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported, in part, by American Cancer Society Grants MRSG-11-149-01-LIB (to J.P.); U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant K08 HL11654701A1 (to B.C.B.); the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation/Bristol-Myers Squibb New Investigator Award (to B.C.B), and by NIH National Cancer Institute Grants R01 CA132197 (to C.A.) and NIH National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant R01 HL114994 (to C.A.).

Glossary

- alloMLR

allogeneic MLR

- AUC

area under the curve

- CI

confidence interval

- DC

dendritic cell

- FoxP3

forkhead box P3

- GI

gastrointestinal

- GVHD

graft-versus-host disease

- HCT

hematopoietic cell transplantation

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- ILC3

type 3 innate lymphoid cell

- MFI

mean fluorescence intensity

- moDC

monocyte-derived dendritic cell

- mTOR

mammalian target of rapamycin

- MTX

methotrexate

- NA

numerical aperture

- OD

optical density

- OR

odds ratio

- PSTAT3

phosphorylated STAT3

- Rapa

rapamycin

- ROC

receiver operator characteristic

- RORγt/C

retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptor γt/C

- SLE

systemic lupus erythematosus

- STAT3i

STAT3 inhibitor

- TAC

tacrolimus

- TMA

tissue microarray

- TORC1

mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1

- Treg

regulatory T cell

Footnotes

The online version of this paper, found at www.jleukbio.org, includes supplemental information.

AUTHORSHIP

B.C.B. designed the overall study, performed experiments, analyzed and interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript. E.M.S., A.V., and M.C.L. assisted with the design, analysis, and interpretation of data for select experiments. F.B. assisted with the performance of selected experiments. H.R.L. synthesized the S3I-201. B.Y. and J.K. provided statistical design and analysis of the data. J.P. and C.A. designed the overall study, supervised the performance of experiments, and oversaw data analysis and interpretation. S.M.S. provided data interpretation for cell signaling experiments. E.M.S., J.K., H.R.L., S.M.S., and C.A. edited the manuscript. J.P. cowrote and edited the manuscript.

DISCLOSURES

The authors have no competing financial interests to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Betts B. C., Abdel-Wahab O., Curran S. A., St Angelo E. T., Koppikar P., Heller G., Levine R. L., Young J. W. (2011) Janus kinase-2 inhibition induces durable tolerance to alloantigen by human dendritic cell-stimulated T cells yet preserves immunity to recall antigen. Blood 118, 5330–5339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Betts B. C., Veerapathran A., Pidala J., Yu X. Z., Anasetti C. (2014) STAT5 polarization promotes iTregs and suppresses human T-cell alloresponses while preserving CTL capacity. J. Leukoc. Biol. 95, 205–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Park O. K., Schaefer L. K., Wang W., Schaefer T. S. (2000) Dimer stability as a determinant of differential DNA binding activity of Stat3 isoforms. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 32244–32249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laurence A., Amarnath S., Mariotti J., Kim Y. C., Foley J., Eckhaus M., O’Shea J. J., Fowler D. H. (2012) STAT3 transcription factor promotes instability of nTreg cells and limits generation of iTreg cells during acute murine graft-versus-host disease. Immunity 37, 209–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laurence A., Tato C. M., Davidson T. S., Kanno Y., Chen Z., Yao Z., Blank R. B., Meylan F., Siegel R., Hennighausen L., Shevach E. M., O’shea J. J. (2007) Interleukin-2 signaling via STAT5 constrains T helper 17 cell generation. Immunity 26, 371–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Littman D. R., Rudensky A. Y. (2010) Th17 and regulatory T cells in mediating and restraining inflammation. Cell 140, 845–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iclozan C., Yu Y., Liu C., Liang Y., Yi T., Anasetti C., Yu X. Z. (2010) T Helper17 cells are sufficient but not necessary to induce acute graft-versus-host disease. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 16, 170–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fulton L. M., Carlson M. J., Coghill J. M., Ott L. E., West M. L., Panoskaltsis-Mortari A., Littman D. R., Blazar B. R., Serody J. S. (2012) Attenuation of acute graft-versus-host disease in the absence of the transcription factor RORγt. J. Immunol. 189, 1765–1772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kappel L. W., Goldberg G. L., King C. G., Suh D. Y., Smith O. M., Ligh C., Holland A. M., Grubin J., Mark N. M., Liu C., Iwakura Y., Heller G., van den Brink M. R. (2009) IL-17 contributes to CD4-mediated graft-versus-host disease. Blood 113, 945–952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu Y., Wang D., Liu C., Kaosaard K., Semple K., Anasetti C., Yu X. Z. (2011) Prevention of GVHD while sparing GVL effect by targeting Th1 and Th17 transcription factor T-bet and RORγt in mice. Blood 118, 5011–5020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramesh R., Kozhaya L., McKevitt K., Djuretic I. M., Carlson T. J., Quintero M. A., McCauley J. L., Abreu M. T., Unutmaz D., Sundrud M. S. (2014) Pro-inflammatory human Th17 cells selectively express P-glycoprotein and are refractory to glucocorticoids. J. Exp. Med. 211, 89–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kurebayashi Y., Nagai S., Ikejiri A., Ohtani M., Ichiyama K., Baba Y., Yamada T., Egami S., Hoshii T., Hirao A., Matsuda S., Koyasu S. (2012) PI3K-Akt-mTORC1-S6K1/2 axis controls Th17 differentiation by regulating Gfi1 expression and nuclear translocation of RORγ. Cell Reports 1, 360–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Donia M., Mangano K., Amoroso A., Mazzarino M. C., Imbesi R., Castrogiovanni P., Coco M., Meroni P., Nicoletti F. (2009) Treatment with rapamycin ameliorates clinical and histological signs of protracted relapsing experimental allergic encephalomyelitis in Dark Agouti rats and induces expansion of peripheral CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. J. Autoimmun. 33, 135–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pidala J., Kim J., Jim H., Kharfan-Dabaja M. A., Nishihori T., Fernandez H. F., Tomblyn M., Perez L., Perkins J., Xu M., Janssen W. E., Veerapathran A., Betts B. C., Locke F. L., Ayala E., Field T., Ochoa L., Alsina M., Anasetti C. (2012) A randomized phase II study to evaluate tacrolimus in combination with sirolimus or methotrexate after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Haematologica 97, 1882–1889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cutler C., Logan B., Nakamura R., Johnston L., Choi S., Porter D., Hogan W. J., Pasquini M., MacMillan M. L., Hsu J. W., Waller E. K., Grupp S., McCarthy P., Wu J., Hu Z. H., Carter S. L., Horowitz M. M., Antin J. H. (2014) Tacrolimus/sirolimus vs tacrolimus/methotrexate as GVHD prophylaxis after matched, related donor allogeneic HCT. Blood 124, 1372–1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Przepiorka D., Weisdorf D., Martin P., Klingemann H. G., Beatty P., Hows J., Thomas E. D. (1995) 1994 Consensus Conference on Acute GVHD Grading. Bone Marrow Transplant. 15, 825–828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Betts B. C., St Angelo E. T., Kennedy M., Young J. W. (2011) Anti-IL6-receptor-alpha (tocilizumab) does not inhibit human monocyte-derived dendritic cell maturation or alloreactive T-cell responses. Blood 118, 5340–5343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim H. Y., Lee H. J., Chang Y. J., Pichavant M., Shore S. A., Fitzgerald K. A., Iwakura Y., Israel E., Bolger K., Faul J., DeKruyff R. H., Umetsu D. T. (2014) Interleukin-17-producing innate lymphoid cells and the NLRP3 inflammasome facilitate obesity-associated airway hyperreactivity. Nat. Med. 20, 54–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geiger T. L., Abt M. C., Gasteiger G., Firth M. A., O’Connor M. H., Geary C. D., O’Sullivan T. E., van den Brink M. R., Pamer E. G., Hanash A. M., Sun J. C. (2014) Nfil3 is crucial for development of innate lymphoid cells and host protection against intestinal pathogens. J. Exp. Med. 211, 1723–1731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Longman R. S., Diehl G. E., Victorio D. A., Huh J. R., Galan C., Miraldi E. R., Swaminath A., Bonneau R., Scherl E. J., Littman D. R. (2014) CX₃CR1⁺ mononuclear phagocytes support colitis-associated innate lymphoid cell production of IL-22. J. Exp. Med. 211, 1571–1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Munneke J. M., Björklund A. T., Mjösberg J. M., Garming-Legert K., Bernink J. H., Blom B., Huisman C., van Oers M. H., Spits H., Malmberg K. J., Hazenberg M. D. (2014) Activated innate lymphoid cells are associated with a reduced susceptibility to graft-versus-host disease. Blood 124, 812–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin A. M., Rubin C. J., Khandpur R., Wang J. Y., Riblett M., Yalavarthi S., Villanueva E. C., Shah P., Kaplan M. J., Bruce A. T. (2011) Mast cells and neutrophils release IL-17 through extracellular trap formation in psoriasis. J. Immunol. 187, 490–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keijsers R. R., Hendriks A. G., van Erp P. E., van Cranenbroek B., van de Kerkhof P. C., Koenen H. J., Joosten I. (2014) In vivo induction of cutaneous inflammation results in the accumulation of extracellular trap-forming neutrophils expressing RORγt and IL-17. J. Invest. Dermatol. 134, 1276–1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ratajewski M., Walczak-Drzewiecka A., Salkowska A., Dastych J. (2012) Upstream stimulating factors regulate the expression of RORγT in human lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 189, 3034–3042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Siddiquee K., Zhang S., Guida W. C., Blaskovich M. A., Greedy B., Lawrence H. R., Yip M. L., Jove R., McLaughlin M. M., Lawrence N. J., Sebti S. M., Turkson J. (2007) Selective chemical probe inhibitor of Stat3, identified through structure-based virtual screening, induces antitumor activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 7391–7396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zeiser R., Leveson-Gower D. B., Zambricki E. A., Kambham N., Beilhack A., Loh J., Hou J. Z., Negrin R. S. (2008) Differential impact of mammalian target of rapamycin inhibition on CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells compared with conventional CD4+ T cells. Blood 111, 453–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fine J. P., Gray R. J. (1999) A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 94, 496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levine J. E., Logan B., Wu J., Alousi A. M., Ho V., Bolaños-Meade J., Weisdorf D.; Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network (2010) Graft-versus-host disease treatment: predictors of survival. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 16, 1693–1699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ueda A., Zhou L., Stein P. L. (2012) Fyn promotes Th17 differentiation by regulating the kinetics of RORγt and Foxp3 expression. J. Immunol. 188, 5247–5256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hedrich C. M., Rauen T., Apostolidis S. A., Grammatikos A. P., Rodriguez Rodriguez N., Ioannidis C., Kyttaris V. C., Crispin J. C., Tsokos G. C. (2014) Stat3 promotes IL-10 expression in lupus T cells through trans-activation and chromatin remodeling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 13457–13462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zeng Z. Z., Yellaturu C. R., Neeli I., Rao G. N. (2002) 5(S)-Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid stimulates DNA synthesis in human microvascular endothelial cells via activation of Jak/STAT and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling, leading to induction of expression of basic fibroblast growth factor 2. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 41213–41219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Couto J. P., Almeida A., Daly L., Sobrinho-Simões M., Bromberg J. F., Soares P. (2012) AZD1480 blocks growth and tumorigenesis of RET-activated thyroid cancer cell lines. PLoS ONE 7, e46869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lozza L., Rivino L., Guarda G., Jarrossay D., Rinaldi A., Bertoni F., Sallusto F., Lanzavecchia A., Geginat J. (2008) The strength of T cell stimulation determines IL-7 responsiveness, secondary expansion, and lineage commitment of primed human CD4+IL-7Rhi T cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 38, 30–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Broady R., Yu J., Chow V., Tantiworawit A., Kang C., Berg K., Martinka M., Ghoreishi M., Dutz J., Levings M. K. (2010) Cutaneous GVHD is associated with the expansion of tissue-localized Th1 and not Th17 cells. Blood 116, 5748–5751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ratajczak P., Janin A., Peffault de Latour R., Leboeuf C., Desveaux A., Keyvanfar K., Robin M., Clave E., Douay C., Quinquenel A., Pichereau C., Bertheau P., Mary J. Y., Socié G. (2010) Th17/Treg ratio in human graft-versus-host disease. Blood 116, 1165–1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lord J. D., Hackman R. C., Gooley T. A., Wood B. L., Moklebust A. C., Hockenbery D. M., Steinbach G., Ziegler S. F., McDonald G. B. (2011) Blood and gastric FOXP3+ T cells are not decreased in human gastric graft-versus-host disease. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 17, 486–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Veerapathran A., Pidala J., Beato F., Betts B. C., Kim J., Turner J. G., Hellerstein M. K., Yu X., Janssen W., Anasetti C. (2013) Human regulatory T cells against minor histocompatibility antigens: ex vivo expansion for prevention of graft-versus-host disease. Blood 122, 2251–2261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Veerapathran A., Pidala J., Beato F., Yu X. Z., Anasetti C. (2011) Ex vivo expansion of human Tregs specific for alloantigens presented directly or indirectly. Blood 118, 5671–5680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Das R., Komorowski R., Hessner M. J., Subramanian H., Huettner C. S., Cua D., Drobyski W. R. (2010) Blockade of interleukin-23 signaling results in targeted protection of the colon and allows for separation of graft-versus-host and graft-versus-leukemia responses. Blood 115, 5249–5258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pidala J., Perez L., Beato F., Anasetti C. (2012) Ustekinumab demonstrates activity in glucocorticoid-refractory acute GVHD. Bone Marrow Transplant. 47, 747–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Griffiths C. E., Strober B. E., van de Kerkhof P., Ho V., Fidelus-Gort R., Yeilding N., Guzzo C., Xia Y., Zhou B., Li S., Dooley L. T., Goldstein N. H., Menter A.; ACCEPT Study Group (2010) Comparison of ustekinumab and etanercept for moderate-to-severe psoriasis. N. Engl. J. Med. 362, 118–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Toichi E., Torres G., McCormick T. S., Chang T., Mascelli M. A., Kauffman C. L., Aria N., Gottlieb A. B., Everitt D. E., Frederick B., Pendley C. E., Cooper K. D. (2006) An anti-IL-12p40 antibody down-regulates type 1 cytokines, chemokines, and IL-12/IL-23 in psoriasis. J. Immunol. 177, 4917–4926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tonel G., Conrad C., Laggner U., Di Meglio P., Grys K., McClanahan T. K., Blumenschein W. M., Qin J. Z., Xin H., Oldham E., Kastelein R., Nickoloff B. J., Nestle F. O. (2010) Cutting edge: a critical functional role for IL-23 in psoriasis. J. Immunol. 185, 5688–5691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Paczesny S., Krijanovski O. I., Braun T. M., Choi S. W., Clouthier S. G., Kuick R., Misek D. E., Cooke K. R., Kitko C. L., Weyand A., Bickley D., Jones D., Whitfield J., Reddy P., Levine J. E., Hanash S. M., Ferrara J. L. (2009) A biomarker panel for acute graft-versus-host disease. Blood 113, 273–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.