Abstract

Background

Heart disease is a disabling condition and necessary surgical intervention is often lacking in many developing countries. Training of the superspecialties abroad is largely limited to observation with little or no opportunity for hands on experience. An approach in which open heart surgeries are conducted locally by visiting teams enabling skills transfer to the local team and helps build to build capacity has been adopted at the Uganda Heart Institute (UHI).

Objectives

We reviewed the progress of open heart surgery at the UHI and evaluated the postoperative outcomes and challenges faced in conducting open heart surgery in a developing country.

Methods

Medical records of patients undergoing open heart surgery at the UHI from October 2007 to June 2012 were reviewed.

Results

A total of 124 patients underwent open heart surgery during the study period. The commonest conditions were: venticular septal defects (VSDs) 34.7% (43/124), Atrial septal defects (ASDs) 34.7% (43/124) and tetralogy of fallot (TOF) in 10.5% (13/124). Non governmental organizations (NGOs) funded 96.8% (120/124) of the operations, and in only 4 patients (3.2%) families paid for the surgeries. There was increasing complexity in cases operated upon from predominantly ASDs and VSDs at the beginning to more complex cases like TOFs and TAPVR. The local team independently operated 19 patients (15.3%). Postoperative morbidity was low with arrhythmias, left ventricular dysfunction and re-operations being the commonest seen. Post operative sepsis occurred in only 2 cases (1.6%). The overall mortality rate was 3.2 %

Conclusion

Open heart surgery though expensive is feasible in a developing country. With increased direct funding from governments and local charities to support open heart surgeries, more cardiac patients access surgical treatment locally.

Keywords: Open heart surgery, Uganda Heart Institute

Background

Heart disease is a disabling condition. Performing open heart surgery for congenital heart disease in resource limited countries is a major developmental challenge1 and in several sub Saharan countries this is often unavailable. As a result children in developing countries continue to have a significantly higher incidence and prevalence of serious congenital heart disease, partly due to lack of early corrective surgery2. Lack of facilities for pediatric cardiac surgery results in a large number of potentially preventable death and suffering3.The main options available to children with potentially correctable congenital heart defects include either referral abroad or having foreign surgeons come for short visits to operate on them1. Only few families can afford the referral expenses abroad, yet most charities that sponsor referrals abroad commonly take on those with good prognosis.

Increasingly, a few nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) prefer to sponsor operations of children in their countries of origin where facilities allow. This is not only cheaper but it also helps develop local skills to carry on the surgeries on their own. Eventually developing a specialized cardiac treatment centre in a resource limited setting through such skills transfer programs would be ideal 1. An approach in which open heart surgeries are conducted locally by visiting teams alongside skills transfer to build local capacity has been adopted at the Uganda Heart Institute (UHI) since 2007.

The UHI is the national referral centre for treatment of cardiovascular diseases based at the Mulago Hospital complex. Closed heart surgeries like patient ductus arteniosus (PDA) ligation and pericardiectomy have been routinely performed at the UHI since 1997. Open heart surgery at the UHI began in 2007 with support from visiting teams comprising cardiologists, a cardiac surgeon, perfusionists, cardiac intensive care unit (ICU) nurses, cardiac anesthesiologists, fellows, biomedical personnel, and other staff from sponsoring NGOs. During these open heart surgery camps, the visiting teams carry a number of sundries for use in the operations. Preoperative surgical conferences were held, and the different cadres of visiting health personnel would work with their Ugandan counterparts enabling appropriate skills transfer.

Methods

The objective of the study was to evaluate the progress of open heart surgery at the UHI, to describe the post-operative outcomes and challenges faced in conducting these surgeries. This was a retrospective chart review where medical records of all patients undergoing open heart surgery for either congenital or acquired heart disease at the UHI from October 2007 to June 2012 were included. Those undergoing closed heart surgeries were excluded. Data including age, sex, cardiac diagnosis, type of operation, postoperative complications and ICU and hospital stay and funding source for the surgeries was collected on a structured questionnaire and analysed using SPSS. Data on other challenges faced in conducting the open heart surgeries was obtained from interviews with members of the UHI heart team. Categorical data is presented as frequencies and percentages and quantitative variables are expressed as means with standard deviation. The UHI research ethics committee gave approval to conduct this study.

Results

A total of 124 patients underwent open heart surgery during the study period. Of these, 66 (53.2%) were male. Indications for surgery varied depending on the specific pathologies. Patients with congestive heart failure, large atrial septal defects (ASDs) or VSD (ventricular septal defects), those with severe valvular lesions, or those where surgery is the definitive therapy were operated.

The mean age of the patients was 9.39 years (SD9.76), with age range from 3 months to 52 years. The vast majority of patients were children (age less than 18 years), making up 93.5% (116/124) of the patients (see table 1).

Table 1.

Distribution of different cardiac pathologies operated on by age groups

| Age group | Numbers of patients with Congenital Heart disease |

Numbers of patients with Acquired Heart Disease |

Total | ||||||

| ASD | VSD | TOF | AS | OTHERS | RHD | EMF | Others | ||

| Less than 1 year |

0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2# | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 1–4 years | 10 | 27 | 8 | 2 | 2## | 0 | 0 | 0 | 49 |

| 5–11 years | 13 | 8 | 5 | 1 | 3* | 1 | 0 | 0 | 31 |

| 12–18 years | 9 | 6 | 0 | 3 | 3** | 0 | 2 | 1*** | 24 |

| Above 18 years | 11 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2### | 2 | 0 | 0 | 18 |

| Totals | 43 | 43 | 13 | 7 | 12 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 124 |

The oldest patient with a VSD operated was a 34 year old male with large perimembranous VSD partly occluded by the tricuspid valve presenting with heart failure. A 12 year old girl with RHD having severe aortic regurgitation underwent a Ross procedure.

# Only surgeries in infancy included Re-implantation of an anomalous right pulmonary artery (RPA) arising from the ascending aorta back to the main pulmonary artery (MPA) and severe pulmonary hypertension and a 9 month old who underwent bidirectional Glenn for tricuspid atresia.##; These included an 18 month old girl with a large aortopulmonary window with failure to thrive and congestive heart failure, and a 2 year old girl with supracardiac Total anomalous pulmonary venous connection.###; A 20 year old with partial atrio venticular (AV) Canal defect *included a 5 year old who underwent a bidirectional Glenn for Tricuspid atresia, a 10 year old with Noonan's syndrome who underwent surgical valvuloplasty for severe pulmonary stenosis with dysplastic valves, and a 5 year old with Large PDA and severe left pulmonary artery (LPA) stenosis who underwent LPA plasty and PDA ligation,** A 17 year old with dysplastic pulmonary valves and two patients year old with partial AV canal defect *** and A 19 year old with an atrial myxoma.

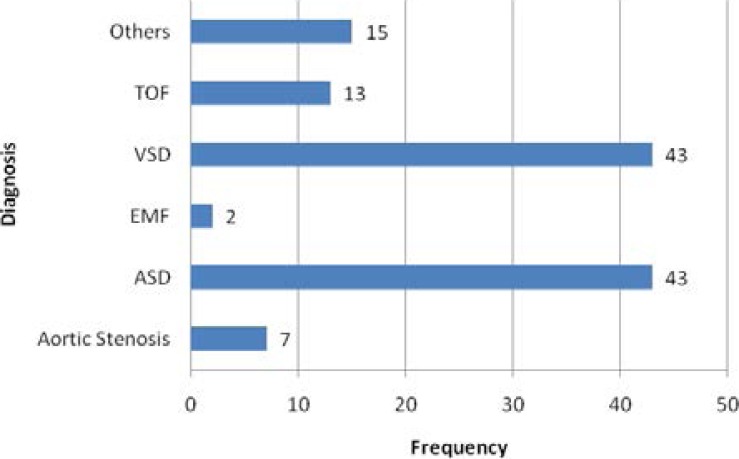

Only 2 children were operated before their first birthday ( a 3 month old patient with anomalous right pulmonary artery arising from the aorta who underwent and a 9 month old with tricuspid atresia who underwent a bidirectional Glenn procedure) , with the age group 1–4 years making the majority followed by those aged 5–11 years (see table 1). Most patients with VSDs were operated between 1–4 years of age; all Tetralogy of Fallot patients were between 1–11 years and with all patients with ASDs nearly equally distributed in the other age groups after infancy. Congenital heart disease surgeries made up 96% (119/124) of the procedures. The commonest conditions were ventricular septal defects (VSD) in 34.7% (44/124), atrial septal defects (ASDs) in 34.7% (43/124) and TOF in 10.5% (13/124), see figure 1.

Figure 1.

Types of congenital heart defects operated at the Uganda Heart institute. Other operations included Valve replacement surgery in 3 patients with RHD, Bidirectional Glenn for tricuspid atresia in two children, TAPVR repair, Aortopulmonary window repair, Pulmonary valve stenosis, Atrioventricular canal defects. Patients with aortic stenosis were those with subaortic membrane resection only.

Acquired heart diseases operated included 3 patients with rheumatic heart disease, 2 patients with endomyocardial fibrosis (EMF) and an adolescent with atrial myxoma. The youngest patient with acquired heart disease was a 12 year old with rheumatic severe aortic regurgitation who underwent a Ross procedure. There was increasing complexity in cases operated from predominantly ASDs and VSDs at the beginning to more complex cases like TOFs and Total anomalous pulmonary venous drainage from 2010. Foreign charities funded 82.3% (102/124) of the operations, and only 4 patients (3.2%) paid for their surgeries. A local NGO funded the rest.

The local team independently operated 19 patients (15.3%). The local team started independently operating ASDs in 2009 and then moved on to the VSDs. The vast majority of patients independently operated by the local team were secundum ASDs (13/19), followed by perimembranous VSDs (4/19) and severe valvular pulmonary stenosis.

The challenges faced by the UHI occurred mainly in areas of staffing and procurement. The UHI at the time of the study had three resident consultant cardiothoracic surgeons with two in training abroad, two consultant pediatric cardiologists and two cardiac anesthesiologists. There was no cardiac intensivist. Staffing levels across all levels of health professionals is still low. Procurement of surgical supplies and sundries was a major challenge that hindered the number of cases performed locally. The mechanical ventilators at the UHI can only be used in older children weighing more than 10kg.

Postoperative morbidity was low with arrhythmias in 13(10.6%) patients being the commonest complication, followed by left ventricular dysfunction and re-interventions occurring in 6 (4.8%) patients each (see table 2).

Table 2.

Showing postoperative complications.

| Post operative complications | Number/124 (%) |

| Need for re-intervention | 6(4.9) |

| Postoperative arrhythmias* | 13(10.6) |

| Left Ventricular Dysfunction | 6(4.9) |

| Pericardial Effusion | 6(4.9) |

| Postoperative Bleeding | 4(3.3) |

| Sildernafil use for pulmonary hypertension |

3(2.4) |

| 30-Day mortality | 4(3.3) |

Note *These excluded sinus tachycardia. Arrhythmias seen included atrial fibrillation, Junctional tachycardia,complete AV block. One patient went on to have a permanent pacemaker inserted. 3 patients needed a temporary pacemaker; two had amiodarone to control their arrhythmias. Most patients with pericardial effusions had small effusions except a patient with EMF who had a moderate pericardial effusion that was drained.

Re-inteverntions included re-exploration due to excessive hemorrhage from chest drains in 4 patients (a ten year old patient having Noonan's syndrome with severe valvular pulmonary stenosis, a 17 year old with EMF, a three year old patient with Large VSD and Large PDA, and a 15 year old with subaortic stenosis ), retrosternal abscess evacuation in a 12 year old girl with subpumonic VSD and a 4 year old with malaligned VSD with complete heart block who underwent permanent pacemaker (VVI) implantation.

Post operative sepsis (defined as wound sepsis or intrathoracic abscess or pyrexia persisting for more than 48 hours postoperatively with leukocytosis or pyrexia with continuation of antibiotics after chest tube drain removal) occurred in only 2 cases (1.6%). These included the patient with retrosternal abscess and an 8 year old with perimembranous VSD who had sternotomy site sepsis.

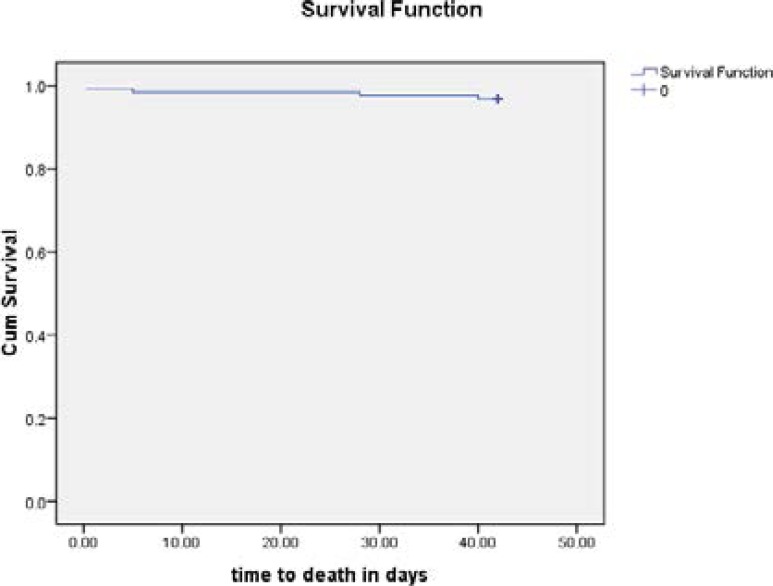

The overall mortality was 3.2 %( 4/124). The earliest post operative death was six hours after the initial surgery, with the latest being 40 days after the surgery (see figure 2).

Figure 2.

Kaplan - Meier survival analysis showing the time to death among study patients.

Those who died included two adolescent patients with EMF having multiorgan failure, a 2 year old child with a VSD and a large PDA, and a 15 year old patient with a large Inlet VSD with severe pulmonary hypertension who developed severe left ventricular dysfunction.

All were operated with the help of visiting teams. Three of the four who died were above 14 years. All of those who died had at least one post operative complication. One of the EMF patients was a 17 year old girl with biventricular EMF having severe tricuspid regurgitation and uncontrolled right heart failure who underwent excision of fibrotic RV endocardium , with tricuspid annuloplasty and bidirectional Glenn procedure. She developed low cardiac output with hypotension immediately after surgery that required inotropic support. Eight hours after surgery she had excessive chest tube bleeding that required re-exploration where bleeders were identified and ligated. She received fresh frozen plasma and vitamin K. She remained ventilator dependent from initial surgery. Three days later she developed hepatic dysfunction with elevation of liver enzymes, worsening jaundice and had continued hypotension with pressor support, with atrial flutter and became unconscious. On the fifth post operative day she developed renal dysfunction, and died on the 5th post operative day from multiorgan failure.

The other EMF patient was a 15 year old boy with Right Ventricular EMF having severe Tricuspid regurgitation. He underwent resection of fibrotic RV endocardium, tricuspid annuloplasty and bidirectional Glenn. He required inotropic support for three days after surgery, and was weaned off the ventilator in 3 days. He spent 5 days in the ICU and was transferred to the main ward. A week later he developed marked respiratory distress, with large bilateral pleural effusions and moderate pericardial effusion that was drained. He was readmitted to the ICU and required mechanical respiratory. He subsequently developed hepatic dysfunction, recurrent pleural effusions, coma, remained on pressor support to maintain cardiac output and developed renal dysfunction. He died on day postoperative day 42 from multiple organ failure.

The two year old with a large perimembranous VSD and large PDA underwent VSD closure and PDA ligation due to poor weight gain and congestive heart failure despite optimal medical therapy. Two hours postoperative the patient developed increased bleeding from chest drainage and bleeding from the sternotomy wounds that necessitated re-operation.

It was found that accidentally the descending aorta was ligated instead of the large PDA that was of identical size. End to end anastomosis of the descending aorta was done. The child died from acute kidney failure 6 hours from initial operation. The 15 year old with a large inlet VSD with cleft mitral valve (with moderate regurgitation) had surgery due to severe pulmonary hypertension that was deemed reversible clinically. Postoperatively he developed moderate LV systolic dysfunction that improved on inotropic support for 48 hours, and was given sildernafil for severe pulmonary hypertension. He spent 5 days in the ICU and was subsequently discharged from hospital after two weeks. Four weeks after initial surgery he was readmitted with symptoms of worsening congestive heart failure. His repeat echo showed severe left ventricular dysfunction and he died from ventricular tachycardia.

Discussion

The experience at the Uganda heart institute shows that open heart surgery is feasible in the setting of a developing country. Most of our patients are operated beyond the age of one year. Currently our pediatric open heart surgery service is severely constrained in meeting the needs of neonates and infants. This situation is common in sub-Saharan countries4. In a study of 51 patients undergoing open heart surgery at Lagos State University Teaching hospital, the mean age was 29±15.6years5.

With appropriate care, up to 85% of children diagnosed with congenital heart disease can reach adulthood6. A great obstacle to the provision of appropriate pediatric cardiac services remains a lack of appropriately trained medical personnel4 and funding for the surgeries.

Major public health issues such as the HIV/AIDS pandemic, coupled with a myriad of tropical diseases like TB and malaria ravage resource limited countries. This makes congenital or acquired cardiovascular diseases less of a priority in government resource allocation7. As such direct government spending towards corrective heart surgery is often lacking or severely limited. To compound the problem further, the prohibitive cost of open heart surgery is virtually out of reach of the vast majority of families in developing countries who have children with heart disease. This was clearly demonstrated in the present study where only 4 patients were able to afford surgery out of pocket. As a result, many patients with surgically correctable heart disease are left with no option but to continue medial therapy and suffer recurrent complications needing outpatient care and hospital admissions. This is the main reason for the low number of patients operated independently by the local team.

This trend of events in the long term amount to higher costs compared to the cost of a single staged corrective surgical repair4. The open heart surgery operations in many developing countries still rely considerably on funding from foreign organizations, as seen in this study and elsewhere5.

The scarcity of a in-country funding sources, unavailability of some specialized sundries within developing countries along with staffing constraints still limit the number of patients in need of open heart surgery that could be operated locally by the resident open heart surgery teams.

Increasing patient volumes in cardiac surgery is essential in boosting confidence of operating teams and refining critical skills that would enhance the development of centers for cardiac surgery and help to improve outcomes8. Access to needed cardiac surgery can be increased if locally based private foundations directly contribute to costs of open heart surgery program7 together with greater direct government funding. This would help minimize the increased morbidity and mortality associated with older age at operation as was seen in this study. Another possible source for direct funding cardiac surgery programs directly engaging locally based corporate entities and civil society in charity funding9.

The mortality rates of 3.3% observed here in the present study are comparable to those seen elsewhere with cardiac centres and other database that are reported to range from 1.8–6.1%10–13. Edwin et al reported mortality rates of 3% among patients with congenital heart disease undergoing open heart surgery, with a reduction in mortality with increase in the volumes of patients operated8. The low postoperative morbidity encountered in this study could be attributable to rigorous patient selection. Late presentation to hospital and less than optimal preoperative evaluation may be a major contributor to postoperative mortality in resource poor settings7. Currently we do not have a pediatric intensivist. Pediatric cardiac intensive care services that specialize in the care of cardiac patients needing postoperative management is an essential part of paediatric cardiac services and contributes significantly to outcomes6. However the patients operated at the UHI were significantly older, there were no neonatal surgeries, and involved significantly less complex congenital heart disease which could have contributed to lower rates of complications. Neonatal surgeries or surgeries for very complex congenital heart disease are associated with higher rates of postoperative morbidity and mortality10–11,13.

The visiting teams also had cardiac intensivists that could have helped reduce the mortality in the present study. Starting with relatively less complex- low risk congenital heart disease surgery with rigorous preoperative assessment is essential to prevent high morbidity and mortality in starting open heart surgery programs in a developing country. The low rate for sepsis seen here compared to other centers in sub Saharan Africa5 could be attributable to rigorous sepsis control measures and the local practice of keeping on antibiotics longer till all chest drains are removed (typically day 2 postoperative), absence s of non emergent open heart surgery (OHS) cases as many patients are prepared electively.

Sample size was attained by enrolling all patients who underwent OHS during the period. We recognize that this study may not be powered enough to draw specific conclusions, but serves to describe experiences at the UHI during the study period.

Conclusion

The experience at the UHI has shown that conducting open heart surgery operations at local sites positively impacts on the ability of local cardiac teams to have hands on training, exposes most local health cadres to quality skills and builds their confidence. This approach has enabled the cardiac team at the UHI to start performing more open heart surgeries of increasing complexity independently. Lack of direct funding for open heart surgery programs is a major obstacle limiting the number of children that can be operated by local teams as only very few families can pay for the costs of the surgeries. Governments and local charities should direct funding to support treatment of more children with heart disease locally as opposed to referral abroad to increase access to the service.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the immense contributions of Dr Craig Sable and the teams from Children's National Medical Centre, Gift of Life International, Riley Children's Hospital, Samaritans Purse, the crown prince of Saudi Arabia, Chain of Hope, the University of North Carolina, the Ministry of Health, Government of Uganda, Rotary clubs of Uganda, Hwan Sung Medical Foundation and the various visiting health professionals that have contributed immensely to the development of open heart surgery at the Uganda Heart institute.

References

- 1.A G Stolf Noedir. Congenital heart surgery in a developing country: a few men for a great challenge. Circulation. 2007;116:1874–1875. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.738021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Global efforts for improving paediatric heart health. Report by the children's heart link. Available at : http:www.childrens heartlink.org.

- 3.Magdi H Yaccoub. Establishing pediatric cardiovascular services in the developing world: a wake up call. Circulation. 2007;116:1876–1878. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.726265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoosen EGM, Cilliers AM, Hugo-Hamman CT, Brown SC, Harrisberg JR, Takawira FF, Govendragelo G, Lawrenson J, Hewitson J. Optimal paediatric cardiac services in South Africa-what do we need? Statement of the paediatric cardiac society of south Africa. SA Heart. 2012;7(1):10–16. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Falase Bode, Sanusi Michael, Majekodunmi Adetinuwe, Animasahun Barakat, Ajose Ifeoluwa, Idowu Ariyo, Oke Adewale. Open heart surgery in Nigeria; a work in progress. Journal of Cardiothoracic Surgery. 2013;8:6. doi: 10.1186/1749-8090-8-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Warnes CA, Liberthson R, Danielson GK, et al. Task Force 1. The changing profile of congenital heart disease in adult life. J AM Coll Cardiol. 2001;37(5):1170–1175. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01272-4. Task Force 1 The changing profile of congenital heart disease in adult life. J AM Coll Cardiol. 2001;37(5):1170–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okafor Ugochukwu, Azike Jerome. An audit of intensive care unit admission in a pediatric cardiothoracic population in Enugu, Nigeria. Pan African Medical Journal. 2010;6:10. doi: 10.4314/pamj.v6i1.69077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edwin F, Tettey M, Aniteye E, Sereboe L, Tamatey M, Entsua-Mensah K, Kotei D B-GK. The development of cardiac surgery in West Africa-the case of Ghana. Pan Afr Med J. 2011;9:15. doi: 10.4314/pamj.v9i1.71190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christine Awuor Yuko-Jowi. African experiences of humanitarian cardiovascular medicine: a Kenyan perspective. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2012;2(3):231–239. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2223-3652.2012.07.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rakhi Balachandran, Nair Suresh G, Gopalraj Sunil S, Vaidyanathan Balu, Kumar R Krishna. Dedicated pediatric cardiac intensive care unit in a developing country: Does it improve the outcome? Ann Pediatr Cardiol. 2011;4(2):122–126. doi: 10.4103/0974-2069.84648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chodchanok Vijarnsorn, Laohaprasitiporn Duangmanee, Durongpisitkul Kritvikrom, et al. Surveillance of Pediatric Cardiac Surgical Outcome Using Risk Stratifications at a Tertiary Care Center in Thailand. Cardiology Research and Practice. 2011:9. doi: 10.4061/2011/254321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Welke K F, Diggs B S, Karamlou T, Ungerleider R M. Comparison of pediatric cardiac surgical mortality ratesfrom national administrative data to contemporary clinical standards. Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2009;87(1):216–223. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rohde S L, Matebele M, Pohlner P, Radford D, Wall D, Fraser JF. Excellent cardiac surgical outcomes in paediatric indigenous patients, but follow-up difficulties. Heart Lung and Circulation. 2010;19(9):517–522. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]