Abstract

Background

Diarrhoea diseases are among the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in under-five-children (U-5C) in Nigeria. Inadequate safe water, sanitation, and hygiene account for the disease burden. Cases of diarrhoea still occur in high proportion in the study area despite government-oriented interventions.

Objective

To determine the hygiene and sanitation risk factors predisposing U-5C to diarrhoea in Ibadan, Nigeria.

Methods

Two hundred and twenty pairs of children, matched on age, were recruited as cases and controls over a period of 5 months in Ibadan. Questionnaire and observation checklist were used to obtain information on hygiene practices from caregivers/mothers and sanitation conditions in the households of 30% of the consenting mothers/caregivers. Data were analysed using descriptive and inferential statistics.

Results

Caregivers/mothers' mean ages were 31.3 ±7.5 (cases) and 30.6 ±6.0(controls) years. The risk of diarrhoea was significantly higher among children whose mothers did not wash hands with soap before food preparation (OR=3.0, p<0.05), before feeding their children (OR=3.0, p<0.05) and after leaving the toilet (OR=4.7, p<0.05). Factors significantly associated with diarrhoea were: poor water handling (OR=2.0,CI=1.2–3.5), presence of clogged drainage near the house (OR=2.1,CI=1.2–3.7) and breeding places for flies (OR=2.7,CI=1.6–4.7). The mean risk score among cases and controls from the sanitary inspection of drinking water sources were 5.4 ± 2.2 and 3.2 ± 1.9 (p<0.05) and household storage containers were 2.4 ± 1.8 and 1.2 ± 0.7 (p<0.05) respectively

Conclusion

Hygiene and sanitation conditions within households were risk factors for diarrhoea. This study revealed the feasibility of developing and implementing an adequate model to establish intervention priorities in sanitation in Ibadan, Nigeria.

Keywords: Diarrhoea, Drinking water, Hygiene Risk Factors, Sanitation, Under five children

Introduction

Diarrhoeal diseases are among the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in young children in developing countries1. Each year, an estimated 2.5 billion cases of diarrhoea occur among children under five years of age, and estimates suggest that overall incidence has remained relatively stable over the past two decades. Africa and Asia account for over half the cases of childhood diarrhoea which is ranked as the fourth leading cause of mortality among under five children in Nigeria 2. Every single day, Nigeria loses about 2,300 under-five year olds and this makes the country the second largest contributor to the under.five mortality rate in the world. Preventable or treatable infectious diseases such as malaria, pneumonia, diarrhoea, measles and HIV/AIDS account for more than 70 per cent of the estimated one million under-five deaths in Nigeria3.

The incidence of diarrhoeal diseases varies greatly with the seasons and a child's age. The youngest children are most vulnerable with incidence been highest in the first two years of life though declines as the child grow older1. The infection is endemic and outbreaks are not unusual in Nigeria. In the last quarter of 2009, it was speculated that more than 260 people died of cholera, the acute form of diarrhoea, in four Northern states 4. The 2010 outbreak of cholera and gastroenteritis in some regions of Nigeria: Jigawa, bauchi, Gombe, Yobe, Borno, Adamawa, Taraba, FCT, Cross River, Kaduna, Osun and Rivers brought to the forefront the vulnerability of poor communities and most especially children to the infection5.

Lack of safe water, basic sanitation and hygiene may account for as much as 88% of the disease burden due to diarrhoea6. Sanitation provision in Ibadan (Nigeria's largest city and capital of Oyo State in the southwest of the country) is grossly deficient, as in most cities in sub-Saharan Africa. Most people do not have access to a hygienic toilet; large amounts of faecal waste are discharged into the environment without adequate treatment; this is likely to have major impacts on infectious disease burden and quality of life7. This case control study was therefore designed to determine the hygiene and sanitation risk factors for diarrhoea among Under five Children (U-5C in Ibadan).

Methods

Study area

Ibadan, the capital of Oyo state Nigeria was selected as the study area because of its varied socio-economic condition and access to health care facilities by the residents. Ibadan is the largest city in West Africa and second largest in Africa covering an area of 240km2. The city is located on longitude 3°5′E and latitude 7°20′N 8. It is situated 125.5Km inland from Lagos, and is a prominent transit point between the coastal region and the areas to the north. The city ranges in elevation from 150m in the valley area, to 275m above sea level on the major north-south ridge which crosses the central part of the city. It has a population of about 3.8million according to 2006 estimates9. The health system in Nigeria is structured along three levels of care: primary, secondary and tertiary. The system is run concurrently such that all the three levels of government - local, state and federal, even though they hold primary responsibility for only one level of the system each, can exceed it and provide services at any of the other two levels of care10. All these levels are available in the study area and the facilities selected for this study are secondary and tertiary centres.

Study Design

This prospective case-control study was carried out in Otunba Tunwase children emergency ward of University College Hospital and Oni Memorial Children's Hospital in Ibadan. 220 children with diarrhoea (cases) and 220 children with malaria and respiratory tract infections (controls) were consecutively recruited over a period of 5 months. Cases of diarrhoea were defined as children under the age of 5 with history of passage of loose bowel stool three or more times within 24 hours while controls were children of the same age with other disease condition except diarrhoea (malaria and respiratory tract infections) presenting in the same health facility.

Sample size determination

The sample size for the study was calculated based on the following assumptions:

P0 = 0.572 which is the proportion of the exposure factor (unsafe drinking water) among the controls (from proportion of controls using safe drinking water source (0.428) in Nigeria. (National Population Commission (NPC) [Nigeria] and ORC Macro, 2004).

OR = 1.7 which is the Odds ratio of diarrhoea among those not using safe drinking water source, (given that there is 42% reduction in diarrhoea morbidity with safe drinking water source. (EHP, UNICEF/WES, USAID, World Bank/WSP, WSSCC, 2004).

Using these assumptions and probability of type 1 error and type 2 error taken as 1.68 and 0.84 respectively, the sample size was calculated to be 200 each for cases and controls. Allowing a 10% non-respondent rate gives a total of 440 for both cases and controls.

Study population

The study population comprised children under-five years of age who presented with signs and symptoms of diarrhoeal disease in the two selected health facilities. A similar number of ‘controls’ were randomly selected from children with diseases which are of similar severity to diarrhoea and which are unrelated to the exposure of interest. These were children less than five years with malaria and Acute Respiratory Infection (ARI).

Eligibility criteria for study participants

Inclusion criteria (cases) were: children above one month but less than 5 years of age with permanent residence in Ibadan, who had three or more loose and watery stools within a 24 hour-period in the past one month including the day of visit to the clinic and whose parents are ready to allow home visit if need be.

Exclusion criteria (cases) were: children with non-infectious diarrhoea with mal-absorption disorder such as celiac disease, lactose intolerance, fructose mal-absorption, short bowel syndrome secondary to surgery/resection of bowel (as diagnosed by their physician) and potential refusal of home visit.

Inclusion criteria (controls) were: children above one month but less than 5 years of age with permanent residence in Ibadan and children who consulted the participating hospitals for non-diarrhoeal complaints in keeping with diagnosis of malaria and acute respiratory infection and whose parents are ready to allow home visit if need be.

Exclusion Criteria (controls) were: children with complaint of diarrhoea in the past one month; children belonging to the same household as the case.

Case selection: Children in the group of one month to 59 months diagnosed by the physician on duty, to have diarrhoea (passage of loose and watery stools at least three times in a 24 hour-period with or without abdominal pain, fever and vomiting) in the past one month including the day of visit to the clinic were selected consecutively over a period of 5 months as cases until a sample size of 220 was achieved.

Control selection: Controls included in the study were children in the group of one month to 59 months of age who visited or were admitted at the participating hospitals for non-diarrhoeal diseases specifically malaria and acute respiratory infection during the study period. In order to avoid any gross imbalance in the case distribution, the controls were stratum matched with cases according to age group in months (1–6, 7–12, 13–18, 19–24, 25–30 etc.)

Method and instrument for data collection

A semi-structured questionnaire developed by the research team was administered to mothers/caregivers of recruited cases and controls with the aid of trained research assistants. A pilot test was done at Adeoyo maternity hospital, Yemetu Ibadan after which the final version of the protocol was defined. After receiving their informed consent, a pre-tested, semi-structured questionnaire was administered to mothers/caregivers of recruited cases and controls to elicit information on: socio-demographic characteristics and hygiene practices of mothers/caregivers; child's baseline characteristics; and environmental/sanitation factors in the households. The Hygiene practices were scored between 0 and 3 depending on the type of variable. The hygiene practice score was categorized into unhealthy practice for score below 50th percentile and healthy practice for score within and above 50th percentile. A 10-item observation checklist developed by the research team was used to assess hygiene practices and sanitation conditions in the households of 30% of the consenting mothers/caregivers (66 each) within 24hrs of recruitment. Each visit lasted for 3–4 hours during which an inventory of behaviours, hygiene practices and condition of sanitary facilities (such as water supply, human and solid waste disposal etc.) was recorded.

Data analysis

The results obtained were analysed using t-test, chi-square and logistic regression. Measures of association were expressed as odds ratios (ORs) for disease with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for categorical variables.

Results

Caregivers/mothers' mean ages for cases and controls were 31.3 ±7.5 and 30.6 ±6.0 years respectively. More cases (66.4%) than controls (59.5%) did not exclusively breastfeed their children in the first six months of life. Results showed that there were significant associations between diarrhoea incidence among U-5C and: low birth weight (OR=1.67, p=0.018); fathers' education (OR=0.50, p=0.02); parents being married (OR=0.58, p=0.007); low household monthly income (OR=2.11, p=0.000) and increased household size (OR=11.5, p=0.000).

Table 1 shows the socio-demographic characteristics of caregivers / mothers for the cases and controls. All these were similar in both except for the educational and marital status, household income and size where there were significant differences.

Table 1.

Relationship between socio-demographic characteristics of caregivers/mothers and diarrhoea disease occurrence among under five children.

| Demographic Characteristics |

Cases (n = 220) |

Controls (n = 220) |

OR (95% CI) | P-value |

| Age in years | ||||

| ≤30 | 123 (55.9%) | 133 (60.5%) | 0.83 (0.57–1.21) | 0.334 |

| ≥30 | 97 (44.1%) | 87 (39.5%) | ||

| Gender of caregiver | ||||

| Female | 212 (96.4%) | 218 (99.1%) | 0.24 (0.05–1.15) | 0.055 |

| Male | 8 (3.6%) | 2 (0.9%) | ||

|

Relationship with child |

||||

| Mother | 196 (89.1%) | 207 (94.1%) | 0.51 (0.25–1.04) | 0.059 |

| aOther Caregivers | 24 (10.9%) | 13 (5.9%) | ||

| Mother's | ||||

| Educational Status | ||||

| At least Secondary | 163 (74.1%) | 179 (81.4%) | 0.66 (0.42–1.03) | 0.067 |

| bOthers | 57 (25.9%) | 41 (18.6%) | ||

| Father's Educational | ||||

| Status | ||||

| At least Secondary | 185 (84.1%) | 201 (91.4%) | 0.50 (0.28–0.90) | 0.020* |

| bOthers | 35 (15.9%) | 19 (8.6%) | ||

| Marital Status | ||||

| Married | 129 (58.6%) | 156 (70.9%) | 0.58(0.39–0.86) | 0.007* |

| cOthers | 91 (41.4%) | 64 (29.1%) | ||

| Household income | ||||

| (Naira/Month) | ||||

| Low income (<20000) | 102 (46.4%) | 64 (29.1%) | 2.11 (1.42–3.12) | 0.000* |

| ≥2000 | 118 (53.6%) | 156 (70.9%) | ||

| Household size | ||||

| ≥7 | 21 (9.5%) | 2 (0.9%) | 11.50 (2.67–49.68) | 0.000* |

| <7 | 199 (90.5%) | 218 (99.1%) |

father, aunt, grandmother,

no formal education, primary, not complete secondary,

Single, divorced, separated or widowed,

=p<0.05

Table 2 shows the relationship between cases / controls and baseline factors. All were similar except for birth weight where there were significant differences.

Table 2:

Relationship between diarrhoeal disease and child baseline factors

| Child's Characteristics |

Cases (n = 220) |

Controls (n = 220) |

OR (95% CI) | p-value |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 113 (51.4%) | 102 (46.4%) | 1.09(0.75–1.59) | 0.633 |

| Female | 107 (48.6%) | 118 (53.6%) | ||

| Birth Weight(kg) | ||||

| < 2.5 | 70 (31.8%) | 48 (21.8%) | 1.67(1.09–2.57) | 0.018* |

| ≥ 2.5 | 150 (68.2%) | 172 (78.2%) | ||

| Child Exclusively | ||||

| Breastfed | ||||

| Yes | 74 (33.6%) | 89 (40.5%) | 0.75(0.51–1.10) | 0.139 |

| No | 146 (66.4%) | 131 (59.5%) | ||

| Birth order | ||||

| 5th and above | 9 (4.1%) | 3 (1.4%) | 3.09 (0.82–11.55) | 0.079 |

| 1st – 4th | 211 (95.9%) | 217 (98.6%) | ||

|

Immunization status |

||||

| Complete | 105 (47.7%) | 103 (46.8%) | 1.04 (0.71–1.51) | 0.849 |

| Others** | 115 (53.2%) | 117 (53.2%) |

=p<0.05

= Not immunized or incomplete

Table 3 shows the relationship between level of hygiene practice of caregivers/ mothers and diarrhoeal incidence. The results show that the mean hygiene scores are 24.57±4.0326.70±3.26 for cases and controls respectively. There was lower risk of diarrhoea among children having mothers with healthy hygiene practices (OR=0.414, p<0.05).

Table 3.

Relationship between level of hygiene practice of caregivers/ mothers and diarrhoeal incidence

| Level of hygiene practice on childhood diarrhoea. |

Cases (n = 220) |

Controls (n = 220) |

OR (95% CI) |

T | P-value |

| Healthy (≥26) | 100 (45.5%) | 147 (66.8%) | |||

| Unhealthy (<26) | 120 (54.5%) | 73 (33.2%) | |||

| Mean | 24.57±4.03 | 26.70±3.26 | 0.414 | −6.088 | 0.000* |

| Min | 12 | 15 | (0.281–0.609) | ||

| Max | 32 | 33 |

=p<0.05

The association between hand-washing practices of caregivers/mothers and diarrhoeal disease incidence is shown in Table 4. The risk of diarrhoea was significantly higher among children whose mothers did not wash hands with soap before food preparation (OR=3.002, p<0.05), before feeding their children (OR=3.011, p<0.05) and after leaving the toilet (OR=4.667, p<0.05).

Table 4.

Relationship between hand-washing practices of caregivers/mothers and diarrhoeal disease incidence

| Item | Case n= 220 |

Control n= 220 |

OR (95% CI) | P-value |

| Hand-washing before preparing food. | ||||

| Always | 91 (41.4%) | 126 (57.3%) | 0.526 | 0.001* |

| Others** | 129 (58.6%) | 94 (42.7%) | (0.360–0.768) | |

| Hand-washing before food preparation. | ||||

| Water only | 146 (69.5%) | 95 (43.2%) | 3.002 | |

| Soap and water | 64 (30.5%) | 125 (56.8%) | (2.018–4.464) | 0.000* |

| Hand-washing before feeding the child | ||||

| Always | 120 (54.5%) | 139 (63.2%) | 0.699 | |

| Others** | 100 (45.5%) | 81 (36.8%) | (0.478–1.024) | 0.066 |

| Hand-washing before feeding the child | ||||

| Water only | 171 (78.8%) | 121 (55.3%) | 3.011 | |

| Soap and water | 46 (21.2%) | 98 (44.7%) | (1.977–4.585) | 0.000* |

| Hand-washing after defecation | ||||

| Always | 173 (78.6%) | 192 (87.3%) | 0.537 | 0.016* |

| Others** | 47 (21.4%) | 28 (12.7%) | (0.322–0.895) | |

| Hand-washing materials | ||||

| Water only | 80 (36.4%) | 24 (10.9%) | 4.667 | 0.000* |

| Soap and water | 140 (63.6%) | 196 (89.1%) | (2.816–7.733) |

=p<0.05

= Often, Sometimes and Never

Table 5 shows the response of mothers to household water treatment, safe storage and handling. Even though there was reduced risk of diarrhoea among children whose caregivers/mothers used jars with covers for storing drinking water, analysis showed an increased risk of diarrhoea among children whose caregivers/mothers collected drinking water from the storage by dipping in any container (OR=3.2, p=0.000). The situation was the same for those: sharing toilet with other households (OR=2.1, p=0.001); using paper for cleaning after defecation (OR=2.0, p=0.411); had dirt (OR=3.5, p=0.011) or foul smell (OR=2.4, p=0.001) around their toilets. However, there was a reduced risk of diarrhoea among children whose caregiver/mothers had adequate water for toilet use (OR=0.287, p=0.011) (Table 4).

Table 5.

Relationship between reported water treatment options, storage, and handling and diarrhoeal disease incidence.

| Variables | Case n=220 |

Control n=220 |

OR (95% CI) | Df | P-value |

| Treatment drinking water | |||||

| Yes | 68 (30.9%) | 90 (40.9%) | 0.646 (0.436–0.957) | ||

| No | 152 (69.1%) | 130 (59.1%) | 1 | 0.029* | |

| Treatment options | |||||

| Boiling | |||||

| Yes | 14 (6.4%) | 17 (7.7%) | 0.812 (0.390–1.690) | 1 | 0.576 |

| No | 206 (93.6%) | 203 (92.3%) | |||

| Filtration | |||||

| Yes | 19 (8.6%) | 23 (10.5%) | 0.810 (0.428–1.533) | 1 | 0.516 |

| No | 201 (91.4%) | 197 (89.5%) | |||

| Use of water guard | |||||

| Yes | 18 (8.2%) | 26 (11.8%) | 0.665 (0.353–1.251) | 1 | 0.204 |

| No | 202 (91.8%) | 194 (88.2%) | |||

| Chlorination | |||||

| Yes | 20 (9.1%) | 26 (11.8%) | 0.746 (0.403–1.381) | 1 | 0.350 |

| No | 200 (90.1%) | 194 (88.2%) | |||

| Decantation | |||||

| Yes | 10 (4.5%) | 20 (9.1%) | 0.476 (0.218–1.042) | 1 | 0.059 |

| No | 210 (95.5%) | 200 (90.1%) | |||

|

Storage/container for drinking purpose |

|||||

| Jar with cover | 37 (17.9%) | 56 (28.6%) | 0.592 (0.372–0.943) | 4 | 0.027* |

| Big plastic container | 79 (38.2%) | 83 (42.3%) | (1) | ||

| Small plastic container | 80 (38.6%) | 52 (26.5%) | |||

| Metal tank | 7 (3.4%) | 4 (1.9%) | |||

| Clay pot | 4 (1.9%) | 1 (0.5%) | |||

|

Material for collecting drinking water from storage |

|||||

| Cup with handle | 84 (40.6%) | 128 (65.3%) | |||

| Use of tap | 12 (5.8%) | 3 (1.5%) | |||

| By pouring | 35 (16.9%) | 34 (17.3%) | |||

| Dipping in any container | 76 (36.7%) | 31 (15.5%) | 3.218 (2.010–5.151) | 3 | 0.000* |

=p<0.05

The results (Table 7) also showed that there was increased risk of diarrhoea among children whose caregivers/mothers used community dumping method (OR=1.7, p=0.011) as against those using government waste management outfit (OR=0.63, p=0.022). Also, there was increased risk of diarrhoea among children with clogged drainage near or around their house (Table 6). There was also a statistical association between diarrhoea among U5-C and presence of breeding places for flies/insects (OR=3.7, p=0.000) and having animals near/around the house (OR=1.7, p=0.005).

Table 7.

Relationship between reported solid waste disposal method of caregivers/mothers and diarrhoeal disease incidence.

| Method of solid waste disposal | Cases N=220 |

Controls N=220 |

OR | P-value |

| Community dumping | ||||

| Yes | 74 (33.6%) | 50 (22.7%) | 1.723 (1.131– | |

| No | 146 (66.4%) | 170 (77.3%) | 2.627) | 0.011* |

| Burning | ||||

| Yes | 86 (39.1%) | 80 (36.4%) | 1.123 (0.764– | 0.555 |

| No | 134 (60.9%) | 140 (63.6%) | 1.652) | |

| Pit | ||||

| Yes | 6 (2.7%) | 1 (0.5%) | 6.140 (0.733– | 0.057 |

| No | 214 (97.3%) | 219 (99.5%) | 51.430) | |

| Collected by garbage truck | ||||

| Yes | 66 (30%) | 89 (40.5%) | 0.631 (0.425– | 0.022* |

| No | 154 (70%) | 131 (59.5%) | 0.936) | |

| Throw into nearby river | ||||

| Yes | 10 (4.5%) | 15 (6.8%) | 0.651 (0.286– | 0.303 |

| No | 210 (95.5%) | 205 (93.2%) | 1.482) |

=p<0.05

Table 6.

Relationship between reported excreta disposal method of caregivers/mothers and diarrhoeal disease incidence among under five children.

| Human waste disposal | Cases N=200 |

Controls N=220 |

OR (95% CI) | df | P-value |

| Latrine available in the house | |||||

| Yes | 205 (93.2%) | 211 (95.9%) | |||

| No | 15 (6.8%) | 9 (4.1%) | 0.583 (0.250–1.362) | 1 | 0.208 |

| Latrine type | |||||

| Pit | 78 (38%) | 61 (28.9%) | 1.432 (0.956–2.145) | 3 | 0.081 |

| Aqua privy | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (0.5%) | (1) | ||

| Pour flush | 23 (11.2%) | 17 (8.1%) | |||

| Water closet | 103 (62.6%) | 132 (62.6%) | |||

|

Latrine for more than one household |

|||||

| Yes | 166(81%) | 70 (33.2%) | 2.113 (1.345–3.319) | 1 | 0.001* |

| No | 39 (19%) | 141 (66.8%) | |||

| Latrine condition | |||||

| Adequate ventilation | |||||

| Yes | 188 (91.7%) | 200 (94.8%) | 0.608 (0.278–1.332) | 1 | 0.210 |

| No | 17 (8.3%) | 11 (5.2%) | |||

| Adequate water | |||||

| Yes | 189 (92.2%) | 206 (97.6%) | 0.287 (0.103–0.798) | 1 | 0.011* |

| No | 16 (7.8%) | 5 (2.4%) | |||

| Dirt around | |||||

| Yes | 16 (7.8%) | 5 (2.4) | 3.488 (1.253–9.705) | 1 | 0.011* |

| No | 189 (92.2%) | 206 (97.6%) | |||

| Faeces on the floor | |||||

| Yes | 7 (3.4%) | 0 (0%) | 0.966 | 1 | 0.007* |

| No | 198 (96.6%) | 211 (100%) | (No) | ||

| Wet floor | |||||

| Yes | 31 (15.1%) | 20 (9.5%) | 1.701 (0.935–3.096) | 1 | 0.079 |

| No | 174 (84.9%) | 191 (90.5%) | |||

| Foul smell | |||||

| Yes | 45 (22%) | 22 (10.4%) | 2.416 (1.392–4.195) | 1 | 0.001* |

| No | 160 (78%) | 189 (89.6%) | |||

| Clean surrounding | |||||

| Yes | 172 (83.9%) | 187 (88.6%) | 0.669 (0.380–1.177) | 1 | 0.161 |

| No | 33 (16.1%) | 24 (11.4%) |

=p<0.05

Discussion

This study identified six important risk factors (among others) that could predispose U5-C to the incidence of diarrhoea. The factors include: poor drinking water handling; lack of hand-washing with soap after defecation and before food preparation; clogged drainage around or near the house; breeding places for flies/insects near the house; and total hygiene practice level.

Poor handling of drinking water was significantly associated with increased risk of childhood diarrhoea. Oloruntoba and Sridhar11 concluded in one of their studies in Ibadan that bacteriological quality of drinking water significantly deteriorated at the household level after collection and storage as a result of poor handling. Trevett at al.,12 reiterated that there are multiple points between drinking water collection and use sequence where pollution could occur. Also, Jagal et al13 identified unhygienic domestic water handling practices as possible sources of household drinking water contamination. Jinadu et al14 in a study carried out in Ondo state of Nigeria revealed that poor storage of drinking water was significantly associated with the high incidence of childhood diarrhoea. Knight et al15 also stated that regardless of where or how the water is collected, storage in vessels with wide openings such as pots or buckets easily allow contamination with faeces through introduction of cups, dippers, or hands.

Simple hygiene behaviours, especially hand-washing with soap, have been suggested to reduce the occurrence of water-washed infections. The outcome of this study about the association between inadequate hand-washing with ‘water and soap’ and incidence of diarrhoea disease among U5-C is in line with various studies16 – 18 concluded that hand-washing practice of mothers before food preparation was associated with a lower risk of diarrhoea among children. Also, a case-control study by Nguyen19 demonstrated that the incidence of diarrhoea among children was significantly higher in families where mothers less often washed their hands before feeding their children. Takanashi et al20 also demonstrated that the risk of diarrhoea was higher among children whose mothers do not always wash their hands with soap before feeding (Adjusted OR=1.38, CI=0.34–5.61). Also, a study on maternal hand-washing behaviour in relation to disposal of faeces and feeding of children by Omotade et al.,21 revealed that handwashing behaviours after cleaning a child who just defecated and after disposal of faeces were observed only in 29.3% episodes, while hand-washing before feeding the child occurred in 12.4% of observations.

This study also revealed that availability of water for anal and hand cleaning after using the toilet, presence of dirt and faeces on toilet floors, and foul smell around the toilet were important factors predisposing children to diarrhoea. Knight et al15 reported in a case-control study carried out in rural Malaysia that having no latrine in the house was not associated with diarrhoea, (OR=1.7, p>0.05) while unavailability of water for washing the anus and hand in those houses which had latrine was significantly associated with diarrhoea (OR=2.8, p<0.05). The result of sanitary inspection of toilet within selected households corroborated this. Most toilets smelled due to the fact that these facilities were not always flushed or washed immediately after use; thus attracting houseflies and suggesting poor hygiene practices. The presence of these flies and faecal matter on the toilet floor are potential risk factors for diarrhoea and other faecal-oral disease transmission. Ekanem et al22 also reported that presence of faeces around households in Iwaya community, Lagos, Nigeria was associated with significant increase in diarrhoeal incidence.

During the study, it was also discovered that some households kept their waste bins in the house while others kept theirs in the perimeter of the houses. Most waste bins were not covered and therefore attract houseflies. The poor waste handling methods exposes children to risk of contamination of food by flies. This might have been responsible for the increase in incidence of diarrhoea U5-C selected for the study as it is an important aspect of faecal-oral route of disease transmission. Similar to this finding, Ekanem et al22 reported in a study carried out in Iwaya community of Lagos state that indiscriminate disposal of solid waste was associated with significant increase in diarrhoeal incidence.

The environmental sanitation in the selected household was very poor. Forty one per cent of cases as against 18% of controls had clogged drainages around or near the house. The percentage of cases with breeding places for flies/insect near the house and domestic animals near/around the house was also higher for cases than controls. All these showed lack of adequate environmental sanitation which could trigger transmission of faeco-oral diseases such as diarrhoea. This study is in line with the finding of Huangprasert et al23 that housefly breeding places, housefly control and its aggravating conditions such as wastewater drainage and cattle excreta in the perimeter of the house were most influential factors associated with diarrhoea. Heller et al24 also reported a significant association between presence of vectors in the house and incidence of diarrhoea. Knight et al15 also reported presence of animals inside the house to be significantly associated with diarrhoea.

Limitations

The fact that severity of the dependent variable diarrhoea was not accessed in this study coupled with selection of 30% of the participants for home visit to observe the environmental sanitation conditions of households are potential limitations of this study. The latter might have resulted in an underestimation of the established risk. Also, following recruitment it was possible that participants might have gone home to tidy up their environment. However this was circumvented to some extent by visiting participants homes within 24 hours of recruitment and not given definite period for visitation.

Conclusion

The study revealed poor drinking water handling and storage within household, hand-washing without soap before food preparation and after defecation are major risk factors for diarrhoea among children less than five years. Inadequate sanitation factors such as presence of clogged drainage near/around the house and breeding places for flies/insects near the house increase the risk of diarrhoea among children less than five years. In all, hygiene practice among the mothers/caregivers of children with diarrhoea was poor. The study concludes that improvement in hygiene; water handling practices and sanitation within households are important factors in the elimination of diarrhoea.

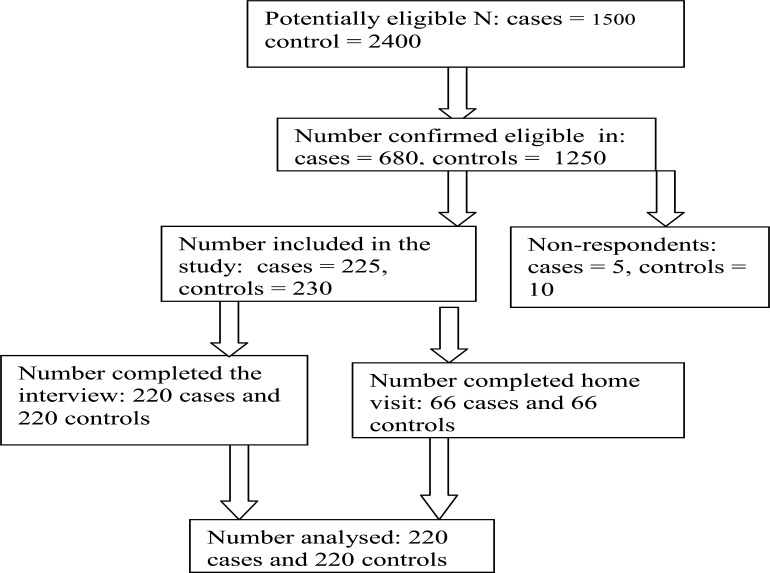

Figure 1.

Study Participants

Table 8.

Relationship between diarrhoeal incidence and reported wastewater disposal method and housing sanitation of caregivers/mothers.

| Variables | Cases N=220 |

Controls N=220 |

OR | P-value |

| Wastewater disposal | ||||

| Wastewater is managed by use of | ||||

| Hygienic (Drainage, Soak away pit) | 179 (81.4%) | 196 (89.1%) | ||

| Unhygienic (others) | 41 (18.6%) | 24 (10.9%) | 0.535 (0.311–0.920) | 0.022* |

|

Clogged drainage around or near the house |

||||

| Yes | 91 (41.4%) | 40 (18.2%) | 3.174 (2.054–4.905) | 0.000* |

| No | 129 (58.6%) | 180 (81.8%) | ||

| Housing sanitation | ||||

|

Breeding places for flies/insects near the house |

||||

| Present/dirty | 106 (48.2%) | 44 (20%) | 3.719 (2.436–5.679) | 0.000* |

| Absent/clean | 114 (51.8%) | 176 (80%) | ||

|

Domestic animals near/around the house |

||||

| Present | 114 (51.8%) | 85 (38.6%) | 1.708 (1.169–2.495) | 0.005* |

| Absent | 106 (48.2%) | 135 (61.4%) |

=p<0.05

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to appreciate all mothers/caregivers who participated in the study for their co-operation during data collection. Special thanks also to members of staff of the Otunba Tunwase Children Emergency Ward of University College Hospital, and Oni Memorial Children's Hospital in Ibadan who were on duty during the period of the study and ensured that it was a success.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure

The authors declare that there was no conflict of interest during this study

References

- 1.Boschi-Pinto C, Velebit L, Shibuya K. Estimating child mortality due to diarrhoea in developing countries. Bulletin of WHO. 2008;86(9):710–717. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.050054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO, author. Reducing mortality from major childhood killer diseases. Mortality Country Fact Sheet. 2006. https://apps.who.int/chd/publications/imci/fs_180.htm.

- 3.UNICEF Nigeria, author. The children-Maternal and child health. http://www.unicef.org/nigeria/children1926.html.

- 4.Igomu T. cholera epidemic: far from being over. NBF News. www.nigerianbestforum.com/blog/?p=60321.

- 5.Gyoh SK. Cholera epidemics in Nigeria: an indictment of the shameful neglect of government. Africa Health. 2011;33(1):5. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Environmental Health Project, author. Lesson Learnt. [Oct. 2012]. PNA-CY112. www.ehproject.org.

- 7.Hutton G, Haller L, Bartram J. Global costbenefit analysis of water supply and sanitation interventions. J Water Health. 2007;5(4):481–502. doi: 10.2166/wh.2007.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Filani MO. Ibadan Region. Re-Charles Publications in conjunction with Connell Publications Ibadan; 1994. 271 pp. [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Population Commission (NPC) and ICF Macro, author. Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2008. Abuja: National Population Commission and ICF Macro; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Asuzu MC. The necessity for health systems reform in Nigeria. Journal of community medicine and primary health care. 2004 Jun;16(1):1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 11.‘Author’. Sridhar MKC. Bacteriological quality of drinking water from source to household in Ibadan, Nigeria. African Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences. 2007;36(2):169–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trevett AF, Carter RC, Tyrrel SF. Water quality deterioration: A study of household drinking water quality in rural Honduras. International Journal of Environmental Health Research. 2004;14(4):273–283. doi: 10.1080/09603120410001725612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jagals P, Jagals C, Bokako TC. The Effect of Container-biofilm on the microbiological quality of water used from plastic household containers. Journal of Water and Health. 2003;1(3):101–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jinadu MK, Olusi SO, Agun JI, Fabiyi AK. Childhood diarrhoea in rural Nigeria: studies on prevalence, mortality and socio-environmental factors. Journal of Diarrhoeal Disease Research. 1991;9(4):323–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knight SM, Toodayan W, Caique WC, Kyin W, Barnesa A, Desmachelier P. Risk factors for the transmission of diarrhoea in children: a case control study in Malaysia. Int J Epidemiology. 1992;21:812–818. doi: 10.1093/ije/21.4.812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gorter AC, Sandiford P, Pauw J, Morales P, Perez RM, Alberts H. Hygiene behaviour in rural Nicaragua in relation to diarrhoea. International Journal of Epidemiology. 1998;27:1090–1100. doi: 10.1093/ije/27.6.1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alam N, Wojtyniak B, Henry FJ, Rahaman MM. Mothers' personal and domestic hygiene and diarrhoea incidence in young children in rural Bangladesh. International Journal of Epidemiology. 1989;18:242–247. doi: 10.1093/ije/18.1.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alam N, Wai L. Importance of age in evaluating effects of maternal and domestic hygiene practices on diarrhoea in rural Bangladeshi children. Journal of Diarrhoeal Diseases Research. 1991;9:104–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nguyen TV, Van PL, Huy CL, Gia KN, Weintraub A. Etiology and epidemiology of diarrhea in children in Hanoi, Vietnam. Int J Infect Dis. 2006;10:298–308. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takanashi K, Chonan Y, Quyen DT, Khan NC, Poudel KC, Jimba M. Survey of food-hygiene practices at home and childhood diarrhoea in Hanoi, Viet Nam. Journal of Health Population Nutrition. 2009;27(5):602–611. doi: 10.3329/jhpn.v27i5.3636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Omotade OO, Kayode CM, Adeyemo AA, Oladepo O. Observations on hand-washing practices of mothers and environmental conditions in Ona-Ara Local government Area of Oyo state, Nigeria. J Diarrhoeal Dis Res. 1995;3(4):224–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ekanem EE, Akitoye CO, Adedeji OT. Food hygiene behaviour and childhood diarrhoea in Lagos, Nigeria: A case-control study. J Diarrhoeal Disease. 1991;9(3):219–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huangprasert S. Potential factors influencing the diarrhoeal disease incidence. Bangkok: Department of Environmental Health Science, Faculty of Public Health, Mahidol University; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heller L, Colosimo EA, Carlos Mauricio de Figueiredo A. Environmental sanitation conditions and health impact: A case-control Scudy. Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical. 2003;36(1):41–50. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822003000100007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]