Abstract

Background

The health seeking behaviour of a community determines how they use health services. Utilisation of health facilities can be influenced by the cost of services, distance to health facilities, cultural beliefs, level of education and health facility inadequacies such as stock-out of drugs.

Objectives

To assess the health seeking practices and challenges in utilising health facilities in a rural community in Wakiso district, Uganda.

Methods

The study was a cross sectional survey that used a structured questionnaire to collect quantitative data among 234 participants. The sample size was obtained using the formula by Leslie Kish.

Results

While 89% of the participants were aware that mobile clinics existed in their community, only 28% had received such services in the past month. The majority of participants (84%) did not know whether community health workers existed in their community. The participants' health seeking behaviour the last time they were sick was associated with age (p = 0.028) and occupation (p = 0.009). The most significant challenges in utilising health services were regular stock-out of drugs, high cost of services and long distance to health facilities.

Conclusions

There is potential to increase access to health care in rural areas by increasing the frequency of mobile clinic services and strengthening the community health worker strategy.

Keywords: Health seeking behaviour, Rural community, Health facilities, Challenges, Uganda

Introduction

The health seeking behaviour of a community determines how health services are used and in turn the health outcomes of populations1. Factors that determine health behaviour may be physical, socio-economic, cultural or political2. Indeed, the utilisation of a health care system may depend on educational levels, economic factors, cultural beliefs and practices. Other factors include environmental conditions, socio-demographic factors, knowledge about the facilities, gender issues, political environment, and the health care system itself3,4.

A key determinant for health seeking behaviour is the organisation of the health care system1. In many health systems, particularly in developing countries such as Uganda, illiteracy, poverty, under funding of the health sector, inadequate water and poor sanitation facilities have a big impact on health indicators. In addition, cost of services, limited knowledge on illness and wellbeing, and cultural prescriptions are a barrier to the provision of health services5. These challenges, which are significant in Uganda's health system, affect the health seeking practices of communities.

Several factors can determine the choice of health care providers that patients use. These include factors associated with the potential providers (such as quality of service and area of expertise) and those that relate to the patients themselves (such as age, education levels, gender, and economic status)6. Such factors can affect access to health care even when services do exist in a community. Despite the availability of many service providers in Uganda, the poor, being financially constrained, normally have limited choice and often use public services many of which are offered free of charge7. Indeed, there is a significant difference in access to various health care providers between the rich and poor8,9. Although self-care and use of traditional healers is categorized under health care, these are often discouraged by health practitioners, with the emphasis on encouraging people to opt for conventional channels with medically trained personnel10.

The poor and other vulnerable groups such as the elderly, who are mainly concentrated in rural areas in Uganda, are the most affected by health system challenges7. Indeed, health facility coverage is greater in urban areas and there is less choice of health service provision in villages. Yet these vulnerable groups are known to be the most at need of these services. The non-use of health facilities leads to undesirable health behaviour such as patients using traditional remedies or no treatment at all which has led to increase in mortality even for easily manageable conditions11.

The Government of Uganda under the Ministry of Health has increased the number of health facilities throughout the country in recent years. However, there are still disparities between urban and rural areas, as well as by geographic location therefore certain communities have more access to health services than others. The lack of public facilities in some communities, which are predominantly used by the poor, is likely to affect the health seeking practices of the population. This problem of inequity in health facility distribution affects the health seeking practices of several communities hence hindering health services utilisation.

Most studies on health seeking behaviour in Uganda have been disease specific particularly on malaria12,13,14. Therefore, limited knowledge is available on general health seeking practices of communities including problems faced in pursuit of health services. The purpose of the study was to assess the health seeking practices and challenges in utilising health facilities in a rural community in Wakiso district, Uganda.

Methods

Study design

The study was a cross-sectional survey. Data was collected between April and May 2010 using a structured questionnaire that was administered by 2 research assistants. The questionnaire was developed in reference to existing tools that had been used in related studies15,16,17,18 and had sections on awareness on health facilities in the area, health seeking practices, problems faced while seeking health services and demographic information of participants.

Study area

The study was conducted in Katabi sub-county, Wakiso district located in the central region of Uganda. The sub-county has 5 parishes and is predominantly a rural community which had a projected population for 2010 of 80,00019. The population is engaged in various economic and social activities such as fishing, crop farming, animal husbandry, petty trading, stone quarrying, brick making and sand mining. The other section of the population is employed in schools, hospitals, factories, recreation centers, and hotels19.

Sample size and sampling technique

A sample size of 234 participants obtained using the formula by Kish and Leslie (1965) for cross-sectional studies was used20. A 95% level of confidence, 81.3% proportion of utilization of health services (obtained from the National Household Survey of 2003) and a 5% level of precision were used in the sample size calculation. Multistage and simple random sampling techniques were used to obtain the participants of the study. The various stages of sampling in the sub-county were parishes, villages and households. Random sampling was used to select 1 parish from the 5 in the subcounty; and 1 village from the 6 in the selected parish. Once the village was obtained, the list of households in the village was used to obtain the households that were involved in the study using a table of random numbers.

From the households selected, only one member per household, preferably the household head, was allowed to participate in the study. In situations where the household head was not available or unwilling to take part, any other adult present was included. Preference for inclusion in the study was given to the older family members such as the spouse of the household head or oldest child. This was considered since the health seeking behaviour of older members of a family is more likely to influence that of other members because of their authority and experience.

Data analysis

Data was analysed using EpiInfo version 3.5.1 and SPSS version 17.0. Analysis involved the generation of frequency distributions from univariate analysis and cross-tabulation of certain variables looking for any associations during bivariate analysis. A p-value of 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical considerations

Approval to conduct the research was obtained from the Makerere University School of Public Health Higher Degrees, Research and Ethics Committee. The study was also registered and cleared by the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology. The local leaders of the study area were duly informed about the study and permission obtained from them before collecting data. Written informed consent was obtained from participants before taking part in the study.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of participants

Farming (34%) and business (36%) were the main occupations of the participants.

The majority of participants (67%) had completed secondary education while only 6% had reached university / tertiary institutions. Regarding the average household monthly income of the participants, 49% earned between 50– 250 US dollars while 48% earned less than 50 US dollars (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of the participants

| Variable | Frequency (N = 234) | Percentage (%) |

| Age | ||

| 18–25 | 38 | 16.2 |

| 26–35 | 150 | 64.1 |

| 36–50 | 45 | 19.2 |

| > 50 | 1 | 0.4 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 112 | 47.9 |

| Female | 122 | 52.1 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Married | 31 | 13.2 |

| Single | 32 | 13.7 |

| Divorced | 16 | 6.8 |

| Widowed | 5 | 2.1 |

| Cohabiting | 150 | 64.1 |

| Occupation | ||

| Farmer | 80 | 34.2 |

| Business | 83 | 35.5 |

| Housewife | 33 | 14.1 |

| Fisherman | 14 | 6.0 |

| Others | 24 | 10.3 |

| Highest level of education | ||

| Primary | 65 | 27.8 |

| Secondary | 156 | 66.7 |

| Tertiary / University | 13 | 5.6 |

| Average household monthly income | ||

| < 50 US dollars | 113 | 48.3 |

| Between 50 – 250 US dollars | 115 | 49.1 |

| Between 250 – 500 US dollars | 5 | 2.1 |

| Don't know | 1 | 0.4 |

Awareness on health facilities

The participants were highly knowledgeable about the health facilities that existed in their community. This included those aware about health centres (100%), clinics (100%) and pharmacies / drug shops (91%). The health centres were government facilities ranging from health centre IIs (the lowest public facility in Uganda) to health centre IVs excluding hospitals. Clinics, pharmacies and drug shops were privately owned facilities.

The majority of participants (89%) were aware that mobile clinic services existed in their community. They reported that these clinics offered: immunization services (88%), laboratory testing (87%), medical consultation (86%) and health education (78%). However, only 28% had received such outreach services in the past 1 month while 52% had received them in the past 6 months.

The majority of participants (84%) did not know whether Community Health Workers (CHWs) existed in their community while 12% mentioned that they were non-existent. Among the 4% of participants who said CHWs existed, the services they mentioned were offered included health education (56%), referral of patients to health facilities (56%) and drug distribution (33%). Only 22% did not know the services offered by CHWs.

Health seeking behaviour

Most of the participants (92%) did not have a regular medical worker to care for their health or to consult. Among those who did not have a regular medical worker, 76% said it was because they used any health worker they found.

When asked what they had ever used when sick, responses given were: health facilities (99%), pharmacies/ drug shops (94%), self treatment with local herbs (81%) and traditional healers (30%). Regarding what they had done the last time they were sick, the majority (65%) had gone to a health facility for treatment while 24% went to a pharmacy or drug shop for medication. Only 2% admitted to having sought treatment from a traditional healer. The participants' health seeking behaviour the last time they were sick showed statistical significance with only age (p = 0.028) and occupation (p = 0.009) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Participants' health seeking behaviour the last time they were sick

| Used | Used | Used | Self | Did | χ2 | P | |

| health | pharmacy | traditional | treatment | nothing | value | value | |

| facility | / drug | healer | with local | at all | |||

| shop | herbs | ||||||

| Gender | 2.129 | 2.129 | 0.780 | ||||

| Male | 75 | 24 | 3 | 9 | 1 | ||

| Female | 77 | 31 | 2 | 12 | 0 | ||

| Age | 24.168 | 0.028 | |||||

| 18 – 25 | 22 | 15 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

| 26 – 35 | 106 | 28 | 4 | 12 | 0 | ||

| 36 – 50 | 23 | 12 | 1 | 8 | 1 | ||

| > 50 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Highest level | 10.018 | 0.242 | |||||

| of education | |||||||

| attained | |||||||

| Primary | 35 | 22 | 3 | 5 | 0 | ||

| Secondary | 107 | 31 | 2 | 15 | 1 | ||

| Tertiary / | 10 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

| University | |||||||

| Average | 19.683 | 0.213 | |||||

| household | |||||||

| monthly | |||||||

| income | |||||||

| < 50 US | 68 | 29 | 2 | 14 | 0 | ||

| dollars | |||||||

| Between 50 – | 80 | 25 | 3 | 6 | 1 | ||

| 250 US | |||||||

| dollars | |||||||

| Between 250 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

| – 500 US | |||||||

| dollars | |||||||

| Don't know | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Occupation | 27.380 | 0.009 | |||||

| Farmer | 47 | 25 | 0 | 8 | 0 | ||

| Business | 63 | 13 | 0 | 6 | 1 | ||

| Housewife | 20 | 6 | 2 | 5 | 0 | ||

| Fisherman | 9 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Others | 13 | 9 | 1 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Distance to | 12.949 | 0.774 | |||||

| nearest | |||||||

| health | |||||||

| facility | |||||||

| Less than ¼ a | 27 | 6 | 1 | 4 | 0 | ||

| kilometer | |||||||

| Between ¼ | 64 | 25 | 3 | 6 | 1 | ||

| and ½ of a |

Almost all the participants (99%) had used a health facility that was outside their village. Among this category, 91% had done so because the particular health facility offered services not offered by those in their area, while 78% said it was because the facility offered free or cheaper services. Most of the health facilities visited outside the participants' village were public (91%) while 64% were private. The majority of participants (73%) had visited a medical practitioner between 1 to 2 times in the past 12 months for their personal needs, while 15% had done so 3 to 4 times. The frequency of visiting a medical practitioner during the last 12 months was statistically significant with only average household monthly income (p = 0.038) (Table 3)

Table 3.

The number of times participants visited a medical practitioner for their personal medical needs during the last 12 months

| Not at all | 1 to 2 | 3 to 4 | 5 to 10 | χ2 | P | |

| times | times | times | value | value | ||

| Gender | 3.074 | 0.389 | ||||

| Male | 7 | 87 | 15 | 3 | ||

| Female | 11 | 83 | 21 | 7 | ||

| Age | 10.335 | 0.401 | ||||

| 18 – 25 | 4 | 23 | 7 | 4 | ||

| 26 – 35 | 12 | 110 | 22 | 6 | ||

| 36 – 50 | 2 | 36 | 7 | 0 | ||

| > 50 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Highest level of | 7.078 | 0.257 | ||||

| education | ||||||

| attained | ||||||

| Primary | 4 | 50 | 9 | 2 | ||

| Secondary | 11 | 111 | 27 | 7 | ||

| Tertiary / | 3 | 9 | 0 | 1 | ||

| university | ||||||

| Average | 17.101 | 0.038 | ||||

| household | ||||||

| monthly income | ||||||

| < 50 US dollars | 7 | 92 | 13 | 1 | ||

| Between 50 – 250 | 10 | 73 | 23 | 9 | ||

| US dollars | ||||||

| Between 250 – 500 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | ||

| US dollars | ||||||

| Don't know | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Occupation | 15.572 | 0.108 | ||||

| Farmer | 7 | 62 | 11 | 0 | ||

| Business | 4 | 58 | 16 | 5 | ||

| Housewife | 2 | 22 | 5 | 4 | ||

| Fisherman | 1 | 10 | 2 | 1 | ||

| Others | 4 | 18 | 2 | 0 | ||

| Distance from | 19.105 | 0.081 | ||||

| nearest health | ||||||

| facility | ||||||

| Less than ¼ a | 2 | 23 | 8 | 5 | ||

| kilometer | ||||||

| Between ¼ and ½ | 6 | 68 | 20 | 5 | ||

| of a kilometer | ||||||

| Between ½ and ¾ | 3 | 36 | 4 | 0 | ||

| of a kilometer | ||||||

| Between ¾ and 1 | 6 | 38 | 4 | 0 | ||

| kilometer | ||||||

| More than a | 1 | 5 | 0 | 0 | ||

| kilometer |

Challenges of using health facilities

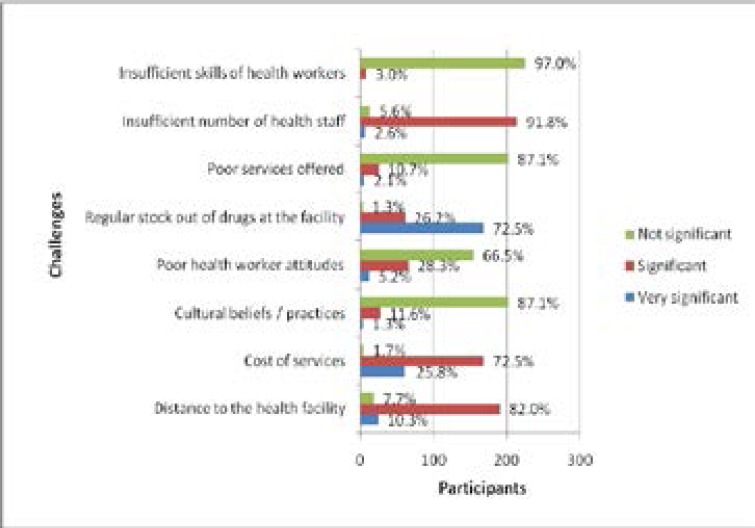

Nearly all of the participants (99.6%) had ever experienced a challenge while accessing health facilities. The most outstanding challenges faced were regular stockout of drugs, high cost of services and long distance to health facilities (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Challenges of accessing health facilities

The nearest health facilities to the participants' homes were clinics (68%), health centres (21%), and pharmacies / drug shops (11%). The distance of these nearest facilities from the participants' homes is shown in Table 4. No hospital existed in the community.

Table 4.

Distance of nearest health facilities from homes

| Distance | Frequency (N = 234) | Percentage (%) |

| Less than ¼ a kilometer | 38 | 16.2 |

| Between ¼ and ½ of a | 99 | 42.3 |

| kilometer | ||

| Between ½ and ¾ of a | 43 | 18.4 |

| kilometer | ||

| Between ¾ and 1 kilometer | 48 | 20.5 |

| More than a kilometer | 6 | 2.6 |

While sick, the majority of participants (75%) used commercial motorcycles to travel to health facilities while 18% walked. The rest used either bicycles (5%) or vehicles (2%).

Discussion

The participants were generally low earners based on their average monthly household income. This clearly relates to the high poverty levels in Uganda particularly in rural communities. Such low income levels can affect uptake and utilisation of health services particularly in communities with no public health facilities where services are supposed to be offered for free following abolition of user fees in 200121.

Mobile clinic services are crucial in supplementing services offered at health facilities especially in communities where these are few hence necessitating to travel long distances to seek medical attention (among other challenges). These services are known to be very beneficial to disadvantaged populations such as the poor (including those without health insurance), and where no services are provided22,23.

With a range of services offered at these mobile clinics including immunization, laboratory testing, medical consultation and health education as established by this study, the population would immensely benefit from them.

Although the Ministry of Health (Uganda) recommends mobile clinic services for hard to reach areas and disadvantaged groups24.

Use of CHWs in health service delivery is a strategy used in Uganda and other countries that serves as a community's initial point of contact for health. These CHWs are volunteers who carry out community mobilization, drug distribution, health education, and referral of patients to health facilities. Although CHWs are known to increase access to health care and facilitate appropriate use of health resources25, several studies have indicated high attrition rates amongst them26,27,28.

The major challenges facing CHWs include inadequate , lack of community support, inadequate refresher training, unclear roles and expectations, inadequate supervision, and inappropriate selection of workers26. Although each village in Uganda is recommended to have on average 5 CHWs in form of village health team members29, their numbers are often inadequate as they cover large geographic areas with inadequate means of transport30. Indeed, with the majority of participants in this study unaware of the existence of CHWs in their community, the strategy was not being fully utilised hence the need for strengthening. Having a regular health practitioner enhances health services utilisation and outcomes as it promotes continuity of care31,32.

When a patient visits the same medical worker whenever they are sick, it enables the health practitioner to monitor the health of the patient over time as opposed to visiting a different one during every sickness episode. Indeed, studies have shown that patients with some form of constant care have better access to services than those without a regular source of care33,34. However, rural inhabitants are more likely to lack a regular source of care than those in urban areas mainly because of local resource inaccessibility35. Indeed, the majority of participants in this study did not have regular medical workers for their health needs.

The use of traditional healers was low as established in other studies36,37. However, the use of traditional healers may have been under reported as it is at times associated with stigma36 hence those using them may not openly declare so. Other studies have shown that a biomedical provider is more likely to be consulted when one has a condition with multiple symptoms and occurring for a long time38,39. Patients who seek health care frequently report better health than those who do so less frequently28,40. However, multiple factors are known to influence patient-health worker encounters such as the complexity of the condition, level of patient concern and trust between patient and health worker41. Although the frequency of seeking health care increased with income levels which compares with other studies42,43, some evidence suggests that the poor (and other vulnerable groups) visited health centres more frequently44,45 due to higher burden of disease7. In addition, certain age groups such as children and the elderly46 are known to be vulnerable to illnesses hence have regular visits for medical attention.

The problem of regular stock out of drugs has been known in the Ugandan health system for a long time. The reasons for its occurrence include the long procurement process (bureaucracy) for drugs from the main government suppliers (National Medical Stores - NMS), monopoly of NMS, inadequate funding for essential drugs, lack of skills in medicine forecasting, poor selection and quantification of medicines, poor records management and lack of prioritization47. The continued absence of essential drugs especially at public health facilities has a negative impact on health services utilisation as people shun health facilities because of the usual trend of no drugs. This is likely to lead to unfavourable behaviours such as self medication or use of traditional healers.

High cost of services and long distances to health facilities were the other main challenges established. Other studies conducted elsewhere have also indicated that cost is often a barrier to seeking health services especially among the poor48,49. Due to abolition of user fees at public health facilities, rural communities use them frequently7. However, due to the limited number of public facilities particularly in rural areas, inhabitants are necessitated to use private health care providers at a cost.

The rich may also opt for private facilities because of their higher ability to pay for services50. Long distance that patients need to travel to get health services is a precursor to use of such services. This has been shown in several studies that distance to health facilities affects health services utilisation51,52. The problem of distance to health facilities is aggravated by the high poverty levels in rural communities which affects expenditure on transport. Some patients including those that are disabled or pregnant may not attempt long distances to seek health care without adequate means of transport. Although constructing more health facilities in the country could be a long term strategy to address this problem, providing more frequent mobile clinic services would greatly benefit the rural population.

These use of commercial motorcycles have become a popular means of transport in recent times in Uganda and other countries in the developing world53,54. Indeed, they play an important role in the transport industry for the local economies. In the health sector, motorcycles have been seen to be important especially in emergency situations where a quick response is needed55.

The main limitation of this study is that the findings are limited in terms of generalization and impact since it was a case study conducted in one rural community. There may also have been recall bias when responding to some of the questions asked. Nevertheless, the data provides useful information on the health seeking behaviour and challenges in utilising health facilities in rural communities in Uganda which can inform stakeholders in the health sector in Uganda and other low income countries.

Conclusion

There is potential for stakeholders in health service provision to increase access to health care by increasing the frequency of mobile clinic services and strengthening the community health worker strategy particularly in communities with limited access to health facilities such as in rural areas. In addition, there is need for concerned authorities such as ministries of health to address the health systems challenges such as stock-out of drugs at health facilities which have for long affected health service delivery in Uganda.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the financial support provided by Makerere University School of Public Health, in particular the Dean's office and the Department of Health Policy, Planning and Management. We are grateful to the research assistants Godfrey Walusimbi and Frederick Nteza, the chairman of Bbendegere village Samuel Mpanga and all study participants for having made a contribution towards this work. We also thank Wilson Nsubuga for his statistical advice during data analysis.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

The main author (DM) developed the research design, prepared data collection, supervised research assistants during data collection, carried out analysis and drafted the manuscript. PB, CB and MBM assisted with the research design and offered critical comments in the reviewing and writing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Shaikh BT, Hatcher J. Health seeking behaviour and health service utilization in Pakistan: challenging the policy makers. J Public Health (oxf) 2005;1:49–54. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdh207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kroeger A. Anthropological and socio-medical health care research in developing countries. Soc Sci Med. 1983;17:147–161. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(83)90248-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ogunlesi TA, Olanrewaju DM. Socio-demographic Factors and Appropriate Health Care-seeking Behavior for Childhood Illnesses. J Trop Pediatr. 2010;56(6):379–385. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmq009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Katung PY. Socio-economic factors responsible for poor utilization of primary health care services in rural community in Nigeria. Niger J Med. 2001;10:28–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hunte P, Sultana F. Health seeking behaviour and the meaning of medication in Balochistan, Pakistan. Soc Sci Med. 1992;34(12):1385–1397. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90147-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thuan NT, Lofgren C, Lindholm L, Chuc NT. Choice of healthcare provider following reform in Vietnam. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:162. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kiwanuka S, Ekirapa E, Peterson S, Okui O, Rahman MH, Peters D, et al. Access to and utilization of health services for the poor in Uganda: a systematic review of available evidence. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2008;102(11):1067–1074. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nabyonga J, Desmet M, Karamagi H, Kadama PY, Omaswa FG, Walker O. Abolition of cost-sharing is pro-poor: evidence from Uganda. Health Policy Plan. 2005;20(2):100–108. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czi012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yip WC, Wang H, Liu Y. Determinants of patient choice of medical provider: a case study in rural China. Health Policy Plan. 1998;13(3):311–322. doi: 10.1093/heapol/13.3.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahmed S, Adams A, Chowdhury M, Bhuiya A. Gender, socio-economic development and health seeking behaviour in Bangladesh. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51(3):361–371. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00461-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kyomuhendo GB. Low use of rural maternity services in Uganda: impact of women's status, traditional beliefs and limited resources. Reprod Health Matters. 2003;11(21):16–26. doi: 10.1016/s0968-8080(03)02176-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nabyonga Orem J, Mugisha F, Okui AP, Musango L, Kirigia JM. Health care seeking patterns and determinants of out-of-pocket expenditure for malaria for the children under-five in Uganda. Malar J. 2013;12:175. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-12-175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ndyomugyenyi R, Magnussen P, Clarke S. Malaria treatment-seeking behaviour and drug prescription practices in an area of low transmission in Uganda: implications for prevention and control. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2007;101(3):209–215. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amuge B, Wabwire-Mangen F, Puta C, Pariyo GW, Bakyaita N, Staedke S, et al. Health-seeking behavior for malaria among child and adult headed households in Rakai district, Uganda. Afr Health Sci. 2004;4(2):119–124. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sule SS, Ijadunola KT, Onayade AA, Fatusi AO, Soetan RO, Connell FA. Utilization of primary health care facilities: lessons from a rural community in southwest Nigeria. Niger J Med. 2008;17(1):98–106. doi: 10.4314/njm.v17i1.37366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Newbold KB. Health care use and the Canadian immigrant population. Int J Health Serv. 2009;39(3):545–565. doi: 10.2190/HS.39.3.g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pristas I, Bilic M, Pristas I, Voncina L, Krcmar N, Polasek O, et al. Health Care Needs, Utilization and Barriers in Croatia -Regional and Urban-Rural Differences. Coll Antropol. 2009;33 Suppl 1:121–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Byrd TL, Law JG. Cross-border utilization of health care services by United States residents living near the Mexican border. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2009;26(2):95–100. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49892009000800001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Katabi sub-county Local Council, author. Three year development plan 2009/2010–2011/2012. Uganda: Wakiso district; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kish L. Survey sampling. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu K, Evans DB, Kadama P, Nabyonga J, Ogwang PO, Aguilar AM. The elimination of user fees in Uganda: impact on utilization and catastrophic health expenditures. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(4):866–876. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oriol NE, Cote PJ, Vavasis AP, Bennet J, Delorenzo D, Blanc P, et al. Calculating the return on investment of mobile healthcare. BMC Med. 2009;7:27. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-7-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paris N, Porter-O'Grady T. Health on wheels. Health Prog. 1994;75(9):34–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ministry of Health, Uganda, author. Health Sector Strategic Plan III 2010/11 – 2014/152010. Kampala, Uganda: [Google Scholar]

- 25.Witmer A, Seifer SD, Finocchio L, Leslie J, O'Neil EH. Community health workers: integral members of the health care work force. Am J Public Health. 1995;85(8 Pt 1):1055–1058. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.8_pt_1.1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rahman SM, Ali NA, Jennings L, Seraji MH, Mannan I, Shah R, et al. Factors affecting recruitment and retention of community health workers in a newborn care intervention in Bangladesh. Hum Resour Health. 2010;8(1):12. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-8-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khan SH, Chowdhury AM, Karim F, Barua MK. Training and retaining Shasthyo Shebika: reasons for turnover of community health workers in Bangladesh. Health Care Superv. 1998;17(1):37–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gray HH, Ciroma J. Reducing attrition among village health workers in rural Nigeria. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences. 1988;22:39–43. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ministry of Health, Uganda, author. Village Health Team Strategy and Operational Guidelines. Kampala, Uganda: Health Education and Promotion Division; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kalyango JN, Rutebemberwa E, Alfven T, Ssali S, Peterson S, Karamagi C. Performance of community health workers under integrated community case management of childhood illnesses in eastern Uganda. Malar J. 2012;11:282. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-11-282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mainous AG, 3rd, Baker R, Love MM, Gray DP, Gill JM. Continuity of care and trust in one's physician: evidence from primary care in the United States and the United Kingdom. Fam Med. 2001;33(1):22–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Starfied B. Primary Care: concept, evaluation, and policy. New York: Oxford University Press, Inc; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lambrew JM, DeFriese GH, Carey TS, Ricketts TC, Biddle AK. The effects of having a regular doctor on access to primary care. Med Care. 1996;34(2):138–151. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199602000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu KT. Usual source of care in preventive service use: a regular doctor versus a regular site. Health Serv Res. 2002;37(6):1509–1529. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.10524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hayward RA, Bernard AM, Freeman HE, Corey CR. Regular source of ambulatory care and access to health services. Am J Public Health. 1991;81(4):434–438. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.4.434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pariyo GW, Ekirapa-Kiracho E, Okui O, Rahman MH, Peterson S, Bishai DM, et al. Changes in utilization of health services among poor and rural residents in Uganda:are reforms benefitting the poor? Int J Equity Health. 2009;8:39. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-8-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Odaga J. Health inequality in Uganda - the role of financial and non-financial barriers. Health Policy and Development. 2004;2(3):192–208. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sadiq H, Muynck AD. Health care seeking behavior of pulmonary tuberculosis patients visiting Rawalpindi. J Pak Med Assoc. 2001;51(1):10–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Islam A, Aman F. Role of traditional birth attendants in improving reproductive health: lessons from the Family Health Project, Sidh. J Pak Med Assoc. 2001;51(6):218–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Little P, Somerville J, Williamson I, Warner G, Moore M, Wiles R, et al. Psychosocial, lifestyle, and health status variables in predicting high attendance among adults. Br J Gen Pract. 2001;51:987–994. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Neal RD, Heywood PL, Morley S. ‘I always seem to be there’—a qualitative study of frequent attenders. Br J Gen Pract. 2000;50(458):716–723. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yu B, Meng Q, Collins C, et al. How does the New Cooperative Medical Scheme influence health service utilization? A study in two provinces in rural China. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10(1):116. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bennett KJ, Powell MP, Probst JC. Relative financial burden of health care expenditures. Soc Work Public Health. 2010;25(1):6–16. doi: 10.1080/19371910802672007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Trani JF, Bakhshi P, Noor AA, Lopez D, Mashkoor A. Poverty, vulnerability, and provision of healthcare in Afghanistan. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(11):1745–1755. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nguyen P, Bich HanhD, Lavergne MR, Mai T, Nguyen Q, Phillips JF, et al. The effect of a poverty reduction policy and service quality standards on commune-level primary health care utilization in Thai Nguyen Province, Vietnam. Health Policy Plan. 2010;25(4):262–271. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czp064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aday LA. Health status of vulnerable populations. Annu Rev Public Health. 1994;15:487–509. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.15.050194.002415. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ministry of Health, Uganda, author. Annual health sector performance report 2006/7. Kampala, Uganda: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Amone J, Asio S, Cattaneo A, Kweyatulira AK, Macaluso A, Maciocco G, et al. User fees in private non-for-profit hospitals in Uganda: a survey and intervention for equity. Int J Equity Health. 2005;4(1):6. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-4-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Odaga J. Health inequality in Uganda - the role of financial and non-financial barriers. Health Policy and Development. 2004;2(3):192–208. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nabyonga Orem J, Mugisha F, Okui AP, Musango L, Kirigia JM. Health care seeking patterns and determinants of out-of-pocket expenditure for malaria for the children under-five in Uganda. Malar J. 2013;12:175. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-12-175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fatimi Z, Avan I. Demographic, Socio-economic and Environmental determinants of utilization of antenatal care in rural setting of Sindh, Pakistan. J Pak Med Assoc. 2002;52:1849–1869. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kiguli J, Ekirapa-Kiracho E, Okui O, Mutebi A, Macgregor H, Pariyo GW. Increasing access to quality health care for the poor: Community perceptions on quality care in Uganda. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2009;3:77–85. doi: 10.2147/ppa.s4091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Alti-Muazu M, Aliyu AA. Prevalence of psycho-active substance use among commercial motorcyclists and its health and social consequences in Zaria, Nigeria. Ann Afr Med. 2008;7(2):67–71. doi: 10.4103/1596-3519.55678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kisaalita WS, Kibalama JS. Delivery of urban transport in developing countries: the case for the motorcycle taxi service (boda-boda) operators of Kampala. Development Southern Africa. 2007;24(2):345–357. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nakstad AR, Bjelland B, Sandberg M. Medical emergency motorcycle—is it useful in a Scandinavian Emergency Medical Service? Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2009;17(1):9. doi: 10.1186/1757-7241-17-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]