Abstract

Background

Though the use of simulators in operative dentistry is not new, the teaching and learning practices that take place during clinical sessions in skills laboratories are rarely reported. This study was designed to determine the current practices relating to teaching and learning of dental clinical skills in southern Nigeria.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted among the final year dental students in southern Nigeria using anonymous structured questionnaire as instrument for data collection. The questionnaire items included statements relating to existing teaching and learning practices. A five-point Likert scale response option was provided and descriptive summary statistics was computed.

Results

There were 56 (34.8%) females and 105 (65.2%) males. Most of the students (41.0%) agreed that the theoretical concept behind clinical skills is taught prior to clinical sessions and most agreed that the objectives of each clinical session are stated and that the procedures are usually demonstrated. Most of the respondents (39.8%) agreed that feedback was sometimes embarrassing and given at the end of clinical sessions (76.6%). Equipment breakdown was a major challenge to learning.

Conclusion

Dental education in the skills labs within the region appeared standard. However, feedback should be continuous and constructive. Equipment breakdown was the major constraint to learning.

Keywords: Simulators, Dentistry, Clinical skills laboratories, Dentistry, Simulators

Introduction

In clinical operative dental practice, one of the most important skills a dentist must have is the ability to prepare and restore damaged tooth tissue resulting from caries or non-carious lesion, trauma, etc. Knowledge of the concept of tooth preparation and restoration and the dexterity to carry out the procedure are basic requirements for successful restorative dental treatment1,2. It is imperative that dental students acquire appreciable degree of competence in the area of hand piece and dental materials manipulation, patient and mouth mirror positioning, cross infection control as well as restorative dental procedure prior to exposure to real life clinical practice3. Failure to achieve this may lead to irreversible tooth morbidity and unnecessary tooth mortality. Iatrogenic tooth damage is a common finding in some aspects of restorative dental interventions4,5,6.

Therefore, concerns over patient safety have led to a decrease in the popularity of the practice whereby students practice new skills on patient2,7. This has led to an increasing use of simulators in health care education programmes. These may be related to the intense concerns for patients' safety by stakeholders, technological advancements and the realization that the clinical setting is not an ideal environment for learning new clinical skills. In a simulated clinical setting for example, novice dental students can operate on mannequin/phantom heads equipped with jaws and synthetic teeth as well as tooth drilling apparatus to learn and master technical skills required for tooth restoration prior to treating patients thereby transforming them into practicing professionals. The transformation process is designed to help students learn how to collect data, interpret and synthesize findings, evaluate critically the effect of actions taken, perform procedures skillfully, and relate to patients in an ethical and caring manner2,5,8,9.

Effective clinical teaching requires not just clinical skills on the part of the instructors but also, knowledge of general principles of teaching and learning10. Teaching and learning practices that enables a novice dental student to transform to an independent and professional oral health care provider has been described as an important central business of dental educators11. Medicine and Nursing are said to have a literature rich in discussion on student learning in clinical practice, but in Dentistry that literature is almost non-existent5. Jensen et al. (2008)12 reported further that instructional techniques and personal experiences with the use of dental clinical skills laboratories were rarely documented.

At the moment, the teaching and learning practices that currently take place in Nigeria between dental students and their instructors during practical sessions in clinical skills laboratory has not been reported. The aim of the current study was to determine the current practices in teaching and learning dental operative clinical skills in Southern Nigeria dental schools' clinical skills laboratories and to identify the challenges to effective learning experience in dental schools' clinical skills laboratories.

Materials and method

This was a cross-sectional study involving final year dental students in Southern Nigeria dental schools. The southern part of Nigeria is relatively more developed socio-culturally than the northern region and all the dental schools in Nigeria but one are located in the region. The dental schools in this region are strategically located in the cities of Ife (Obafemi Awolowo University), Benin (University of Benin), Lagos (University of Lagos) and Ibadan (University of Ibadan). Others are Enugu (University of Nigeria) and Port Harcourt (University of Port Harcourt).

All the final year dental students in the six dental schools located in the region were enrolled. Students who were not available at the time of the study, who declined participation and those who failed to respond after two or three reminders were excluded from the study. An anonymous structured questionnaire (Appendix A) was employed as the instrument for data collection. The questionnaire items were developed following a focus group discussion among the final year dental students of University of Port Harcourt. The focus group discussion was to explore the students' ideas, perceptions and experiences as regards teaching and learning of clinical skills in simulator learning environment. The areas covered included: existing teaching and learning practices in dental skills laboratory, the challenges and issues relating to transferability of skills from skills laboratory to real clinical practice. During the discussion, all participants were given the opportunity to discuss freely about teaching and learning methods, challenges and personal experiences in simulator skills laboratories. The interviews was recorded on audio tape (with group permission) and later transcribed for analysis.

A five-point Likert scale response options was provided as follows: Strongly Agree=5; Agree=4; Undecided=3; Disagree=2; Strongly Disagree=1. The instrument was pretested among the nine final year students of University of Port Harcourt for clarity and understanding of concept after content/logical validity evidence had been done by two consultant dentists who have had formal training in biomedical education. However, validity coefficient was not calculated. The questionnaires were administered in UNN and UNIPORT by one of the authors and by contact persons not participating in the study in other schools. Each questionnaire has a brief summary of what the study was all about. Before the commencement of the study, ethical clearance was obtained from University of Port Harcourt College Research Ethics Committee.

Statistical analysis

The data was entered into a micro computer and analyzed using SPSS for Windows version 16.0, (SPSS Inc Chicago Illinois, USA). Descriptive statistics was performed on all the questionnaire items.

Results

One hundred and eighty two questionnaires were administered out of which 161 were properly filled and returned to the investigator giving a response rate of 88.5%. Highest number of respondents was recorded from Universities of Benin and Ife. Thirty- six respondents (22.4%) participated from each of these Universities (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socio demographic characteristics of the students

Age range= 21–38years

Mean age= 25.73years

(SD±2.484)

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 105 | 65.2 |

| Female | 56 | 34.8 |

| Address | ||

| Benin | 36 | 22.4 |

| Enugu | 21 | 21 |

| Ibadan | 32 | 19.9 |

| Ife | 36 | 22.4 |

| Lagos | 27 | 16.8 |

| Port Harcourt | 9 | 5.6 |

| Total | 161 | 100.0 |

The least number of respondents came from university of Port Harcourt where there were only nine (5.6%) respondents. Out of the 161 respondents, there were 56 (34.8%) females and 105 (65.2%) males. The age range of the respondents was 21–38 years and the mean was 25.73 years (SD±2.484).

When the statements about operative clinical session were analyzed, most of the respondents (44.7%) strongly agreed that the theoretical concept behind the clinical practice on simulator is usually taught in the class room (lecture) before the practical session begins and this was closely followed by those who simply agreed with the statement (41.0%). Seventy-five respondents (46.6%) agreed that the instructor normally states the objectives of each clinical training session while 53 (32.9%) strongly agreed that the objectives were normally stated. Most of the respondents (43.5%) strongly disagreed with the insinuation that the clinical session is usually preceded by video demonstration and this is followed by those who disagreed (25.5%). The distribution of the participants' responses as regards the statements on whether the instructor normally demonstrates the clinical session to the whole class and sub groups followed the same pattern respectively. Most of the respondents in both cases agreed that the instructor normally demonstrates the procedure before the clinical session.

Ninety respondents (55.9%) agreed that the instructor normally describes the steps involved in each clinical session. Only 27.3% strongly agreed with this assertion. The views of the respondents as regards whether the instructor always ensures that each student knows exactly what to do before the clinical session begins appeared concentrated between disagree and agree points. Twice the number of respondents (16) who strongly agreed that the instructor always ensured that each student know exactly what to do before the clinical session begins disagreed with this assertion and about half (32) the number of those who agreed with this assertion (59) disagreed with it. The number of respondents (75) that agreed that the instructor gave feedback at the end of the clinical session was more than those who agreed that the instructor gave continuous feedback (60) and the number of respondents who were undecided regarding whether the instructor provides continuous feedback was more than those who were undecided regarding whether the respondents provides feedback at the end of clinical session. The result on whether the instructor encourages peer review (review by fellow students) showed that most of the respondents agreed (37.9%) with this assertion. However, the proportion of those who were undecided (23.6%) was very close to the proportion of those who disagreed (21.7%).

Sixty-four respondents agreed that the instructor feedback was sometimes discouraging and this was followed by those who were undecided (48). The number of respondents who disagreed (50) with the assertion that the instructor gives each student enough attention was slightly higher than the number of those who agreed (48). Most of the respondents (46.6%) strongly agreed that frequent equipment/instrument breakdown is a major challenge in the learning process on simulators and this was closely followed (31.7%) by those who agreed with this statement. The number of respondents who were undecided and who disagreed with the assertion that technicians responded promptly to call for assistance when equipment broke down during clinical session was the same (41). However, most of the respondents agreed with the insinuation that technicians did respond promptly to call for assistance during clinical assertion.

Most of the respondents (46.6%) agreed that student performance is usually graded during practice session and in the distant second position were those who strongly agreed with this position. The proportions of respondents who disagreed with and who were undecided as regard the grading of students' performance during clinical session were the same (16.1%) and very close to the proportion (18.6%) of those who strongly agreed with this assertion. Only 18.6% of the respondents strongly agreed that the skills acquired on simulator were easily transferable to clinical practice whereas 40.4% participants representing the highest agreed that the skills were easily transferable. About one-third of the respondents were at most undecided about transferability of skills from clinical skills centre.

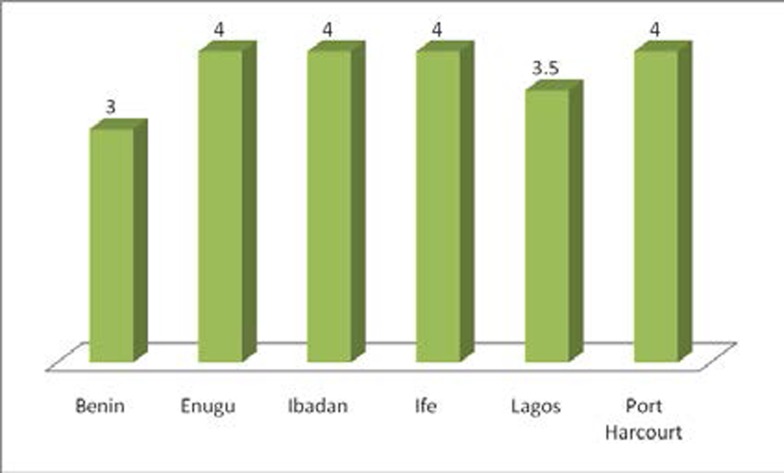

Apart from the respondents from the Universities of Benin and Lagos who had a median score of 3 (undecided) and 3.5(approximately 4) respectively (fig 1), all others recorded a median score of 4 (agree). This suggests that most of the respondents agreed that the skill acquired on simulator was easily transferable to real life clinical practice irrespective of the training institution.

Figure 1.

Distribution of the median scores in skills transferability vs. university of respondents.

Discussion

Current and projected approaches to dental education have created a wide interest in clinical simulation, and recently there has been a considerable expansion in number and complexity of simulators applicable in the field of dental education13. This study presents an overview of teaching and learning methods, challenges and personal experiences in Southern Nigeria dental schools' simulator laboratories. The age distribution of the students involved in this study was similar to that reported by Burch et al. (2011)14 and Ehizele et al. (2011)15. However, smaller number of females was involved in the current study compared to the previous studies. The relatively newer dental schools in the region: Port Harcourt and Enugu had limited capacity and expectedly had smaller number of respondents.

Regarding whether the theoretical background behind the clinical skills, is usually taught or not in the classroom before the practical session, our result shows that most of the students strongly agreed that the theoretical concept behind the clinical practice on simulator is usually taught in the class room (lecture) before the practical session begins. This corroborates the previous report by Gerzina et al. (2005)11 where the students also agreed that there was a clear link between learning of theoretical knowledge and clinical skills in their training. Also, most of the respondents in Rees and Joly's (1998) study16 agreed that learning in clinical skills centre gave more insight into understanding of theoretical concepts and it enables them to integrate basic medical and clinical sciences together. Clinical skills are expected to be integrated into the students' curriculum such that students learn practical skills in conjunction with the theoretical concept17.

Most of the respondents agreed that the instructor normally states the objectives of each clinical training session. At the beginning of clinical sessions in a simulator learning environment, it is a standard requirement to state clearly what the student should know or can practice exactly at the end of each session18. In the study by Gerzina et al. (2005)11 both staff and students agreed that when clinical objectives for clinical sessions are provided, students are better prepared for independent dental clinical dentistry. Peeraer et al. (2007)19 also reported that clinical skills session should be designed to support the intended learning outcomes. Most of the respondents in the Gerzina et al.'s (2005) study11 agreed that stating the clinical objectives for clinical sessions would support student preparation for their independent practice of clinical dentistry. This view was buttressed by Omer et al. (2010)18 who stated that provision of handout or study guide in which the objectives and details of techniques involved in the different clinical skills procedures are clearly stated will encourage sell-directed learning.

When the views of the respondents on whether the clinical sessions are usually preceded by video demonstration or not were analyzed, few of the respondents answered in the affirmative. Learning in clinical skills laboratories in our environment therefore appears deficient in this regard. A previous publication suggests that competence in practical skills and understanding of underlying theoretical concepts can be acquired through observation of video recordings17. Videotapes and CD ROM can also be used to learn (and provide feedback) communication skills such as, dealing with aggressive patients, taking a sexual or alcohol history or delivering bad news17. Maginnis and Crozon (2010)20 were of the view that audio-visual aid like video recording is a unique educational strategy that could assist students to relate theory to practice. Gamut of web-based clinical demonstrations exist that could be utilized to advantage while introducing clinical techniques to learners.

Fugill (2005)5 reported that demonstration is a significant factor in learning psychomotor skills and it should be a common feature of dental student clinical practice. Our result shows that most of the respondents agreed that the instructor normally demonstrates the clinical session to the whole class and a few more respondents also agreed that the instructors do demonstrate the clinical session to subgroups. This is in accordance with standard practice. This finding was at variance with that of Fugill (2005)5 where majority of their respondents indicated that procedures were not often demonstrated by their instructors. Omer et al. (2010)18 stated that it is the responsibility of the instructor to demonstrate the skills on the simulator or using the students themselves. George and Doto (2001)21 reported that learners may not know what the correct task looks like if they have not paid attention to the demonstration, or if there was too much time between when the demonstration took place and his/her attempt to perform the task. Fugill, (2005)5 advised that clinical teachers should be encouraged to make demonstration a regular practice where students are learning new procedures, even though it does take significant time.

Our result on description of the steps involved in performing a clinical skill showed that most of the respondents agreed that the instructor normally describes the steps involved in each clinical session and a smaller number indicated that the instructor always ensures that each student knows exactly what to do before the clinical session begins. One technique that has been used successfully applied overtime in the teaching of psychomotor skills is the five-step method. This method is based on psychomotor teaching principles: conceptualization (the learner is made to understand why the skill is needed and how it is used in the delivery of care); Visualization (the preceptor demonstrates the skill exactly as it should be done without talking through the procedure); verbalization (the preceptor then repeats the procedure but takes time to describe in detail each step in the process. The student is further made to talk through the skill); practice (the students perform the skill) and correction/ reinforcement-feedback and coaching is provided21. It appears the learners were being taught using this approach.

As regard provision of feedback to students by clinical instructor, we observed that more students indicated that clinical instructor gave feedback at the end of the clinical session rather than making it continuous. This finding supports that of Peeraer et al. (2007)19 to the extent that extensive feedback is usually given as reported for the students of the medical faculty, University of Antwerp (UA). In the study by Fugill, (2005)5 33% of the respondents indicated that no feedback was provided by their instructor during clinical supervision while 15% indicated that insufficient feedback was provided. Feedback helps learner to maximize their potential and professional development at different stages of training, raise their awareness of strengths and areas for improvement, and identify actions to be taken to improve performance (McKimm, 2009)22. For feedback to be effective, it should take place at the time of the activity or as soon as possible after so that those involved can remember events accurately and not at the end of the procedure as is often the case in our study (McKimm, 2009)22.

The number of respondents that at least agreed that the instructor encourages peer review (review by fellow students) in our study was less than half of the study sample. Martin et al. (2010)23 reported that peer assessment of psychomotor skills could be an important part of the learning process and a tool to supplement instructor assessment. In their study on peers' ability to assess psychomotor skills, even though students could not detect all errors, they assessed their peers with an average of 96% accuracy.

Most of the respondents agreed that the instructor's feedback is sometimes discouraging and embarrassing. It appears the operative dental instructors in Nigeria need to adjust in this regard. Fugill (2005)5 reported that feedback perceived to be incorrect by the student, or negative feedback which is personality or ability related, may affect self-efficacy and motivation. Similarly, McKimm (2009)22 reported that feedback may need to be given privately wherever possible, especially more negative feedback. Negative feedback should be specific and non-judgmental possibly offering suggestion (McKimm, 2009)22. Clinical instructor should be aware that sometimes feedback is not received positively by learners however constructive it is framed and fear of upsetting the trainee or damaging the trainee-doctor relationship is a well recognized barrier to giving effective feedback22,24. McKimm (2009)22 therefore, advised clinical instructor to be sensitive to the impact of their feedback message. A previous report suggests that students are motivated and inspired by teachers who display compassion and demonstrate genuine interest in them as people and in their futures as dentists25.

In addition, our result shows that most of the respondents disagreed that the instructor gives every student enough attention. The reason why this is so, is not clear at the moment. It could however be multi factorial: over admission, failed attempt to employ self-directed learning and non-commitment on the part of the clinical teachers. Arranging practice sessions for students in the clinical skills laboratory however, had been described as time consuming and most difficult26. Inability of clinical teachers to give enough attention to every student could be fallout of the arbitrary over admission noted in most Nigerian University in the recent past making it impracticable to adequately supervise the students as expected. It has been stated that in a centre where the ratio of students to faculty is relatively high, making sure all students understand each lesson and have completed the required training can be problematic19. Bligh (1995)5 reported that over half of their respondents felt that there were too many students in the unit at any one time while 40% would like more staff available to help them during the sessions. Clinical instructors should remember that skills laboratory enables students to learn at their pace5, they should therefore be patient with the slow learners.

Furthermore, most of the students strongly agreed that equipment breakdown is a major challenge in the learning process on simulator. This corroborates the finding of Widyandana et al., 20106 where the need to repair or replace non-functional mannequins was regarded as one the challenges to effective learning in clinical skills learning environment. Widyandana et al. (2010)6 explained that for developing countries, manikins that poorly resemble the human body and those that are worn out may negatively affect the effectiveness of training in the skills laboratory. Clinical instructors and biomedical administrators must endeavour to include maintenance as part of purchase contract when acquisition of this sensitive and expensive equipment is being contemplated. All equipment should be in good working condition at all times. Periodic inspection, cleaning, maintenance of equipment should be done. An equipment log book should be maintained for all major equipment. Laboratories should maintain necessary instructions for operation and maintenance of equipment in the form of standard operating procedures (SOPs). Maintenance contracts including warranty cards, telephone numbers of staff to be contacted in case of equipment malfunction should be kept safely27. When equipment breakdown occurs during clinical session, however, most of the respondents agreed that the technicians respond promptly to call for assistance. It is believed that this reaction will lessen the stress and frustration brought about by interruptions of practical sessions

Regarding grading of performance during clinical sessions, most of the respondents agreed that this is usually done. It has been reported that skills training as well as skills assessment yielded higher clinical skills competence19. Curtis et al. (2007)28 stated that rating student performance in preclinical and clinical courses can be helpful in monitoring students' progress. Evaluation of students' performance with each patient and/or each procedure by the supervising instructor reveals the students' daily grade. This is a strategic evidence to monitor learners' progress. Most of the students in a previous study agreed that continuous clinical assessment supports the development of the ability of students to provide independent clinical patient dental care11.

At the end of a clinical session, before revealing grades or scores, instructors might consider asking their students for a self-assessment. Encouraging students to reflect on the criteria for excellence and to compare their own performance with that standard promotes learning as much or more than any grade25. The result on transferability of skills showed that most of the respondents agreed that the skills they acquired on simulators was easily transferable to real clinical practice. Davies et al. (2009)29 likewise stated that simulated general dental practice centre was highly rated by past dental students in terms of the overall learning experience received and its relevance to later vocational training.

The findings relating to teaching and learning interactions in this study were based on self- reported and subjective views of a cross-section of students. However, unlike the findings of Widyandana et al. (2010)6 that were based on comments and experience of students from only one school, the current report was derived from comments and experiences of students from all the dental schools in the southern part of Nigeria and is therefore less likely to be affected by local peculiarities.

Conclusion

The teaching and learning interaction that takes place between dental students and their teachers in clinical skills laboratory in the southern part of Nigeria essentially conforms to expected standard practices, but there are certain areas of concern. Feedback administration appeared inappropriate and it also appears that sufficient attention is not being given to all the learners. Video demonstration is virtually non-existent and frequent equipment breakdown constituted barriers to effective learning. We suggest that clinical instructors should be exposed to continuous training in biomedical education, more residency positions should be created for restorative dentistry and faculty appointment should be made more lucrative and flexible to enable more clinical experts get involved in dental education.

Table 2.

Students' views and learning experiences in dental operative clinical skills laboratory N=261

| Characteristics | Strongly Agree(%) |

Agree (%) |

Response Undecided (%) |

Disagree (%) |

Strongly Disagree (%) |

|

| 1 | Theoretical concept behind the clinical practice on simulator is usually taught in the class room (lecture) before the practical session begins |

72(44.7) | 66(41.0) | 12(7.5) | 8(5.0) | 3 (1.9) |

| 2 | The instructor normally states the objectives of each clinical training session |

53(32.9) | 75(46.6) | 19(11.8) | 13(8.1) | 1(0.6) |

| 3 | The clinical session is usually preceded by video demonstration |

7(4.3) | 14(8.7) | 29(18.0) | 41(25.5) | 70(43.5) |

| 4 | The instructor normally demonstrates the clinical session to the whole class |

44(27.3) | 72(44.7) | 17(10.6) | 16(9.9) | 12(7.5) |

| 5 | The instructor normally demonstrates the clinical session to sub groups |

33(21.1) | 76(47.2) | 20(12.4) | 22(13.7) | 9(5.6) |

| 6 | The instructor normally describes the steps involve in each clinical session |

44(27.3) | 90(55.9) | 18(11.2) | 9(5.6) | - |

| 7 | The instructor always ensures that each student knows exactly what to do before the clinical session begins |

16(9.9) | 59(36.6) | 43(26.7) | 32(19.9) | 11(6.8) |

| 8 | The instructor provides continuous feedback to the students |

18(11.2) | 60(37.3) | 50(31.1) | 26(16.1) | 7(4.3) |

| 9 | The instructor provides feedback to the students at the end of the clinical session |

15(9.3) | 75(76.6) | 37(23.0) | 29(18.0) | 5(3.1) |

| 10 | The instructor encourages peer review (review by fellow students) |

16(9.9) | 61(37.9) | 38(23.6) | 35(21.7) | 11(6.8) |

| 11 | The instructor's feedback is sometimes discouraging and embarrassing |

19(9.3) | 64(39.8) | 48(29.8) | 25(15.5) | 9(5.6) |

| 12 | The instructor gives every student enough attention |

15(9.3) | 48(29.8) | 26(16.1) | 50(31.1) | 22(13.7) |

| 13 | Frequent equipment/instrument breakdown is a major challenge in the learning process on simulators |

75(46.6) | 51(31.7) | 12(7.5) | 10(6.2) | 13(8.1) |

| 14 | Technicians respond promptly to call for assistance |

11(6.8) | 48(29.8) | 41(25.5) | 41(25.5) | 20(12.4) |

| 15 | Student performance is usually graded during practice session |

30(18.6) | 75(46.6) | 26(16.1) | 26(16.1) | 4(2.5) |

| 16 | The skills you acquired on simulators was easily transferable to real clinical practice |

30(18.6) | 65(40.4) | 31(19.3) | 23(14.3) | 12(7.5) |

References

- 1.Edwina AM, Bernard GN, Watson Timothy FW. Pickard's Manual of Operative Dentistry. 8 ed. New York: Oxford University Press Inc.; 2003. pp. 1–209. [Google Scholar]

- 2.LeBlanc VR, Urbankova A, Hadavi F, Lichtenthal RM. A Preliminary Study in Using Virtual Reality to Train Dental Students. J Dent Educ. 2004;68:378–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clancy JS, Lindquist TJ, Palik JF, Lynn A, Johnson LA. A Comparison of Student Performance in a Simulation Clinic and a Traditional Laboratory Environment: Three-Year Results. J Dent Educ. 2002;66:1331–1337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Medeiros VA, Seddon RP. Iatrogenic damage to approximal surfaces in contact with Class II restorations. J Dent. 2000;28:103–110. doi: 10.1016/s0300-5712(99)00061-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fugill M. Teaching and learning in dental student clinical practice. Euro J Dent Educ. 2005;9:131–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0579.2005.00378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Widyandana D, Majoor G, Scherpbier A. Transfer of Medical Students' Clinical Skills Learned in a Clinical Laboratory to the Care of Real Patients in the Clinical Setting: The Challenges and Suggestions of Students in a Developing Country. Education for Health. 2010;23 Retrieved July 19, 2012. http://www.educationforhealth.net/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wanzel KR, Ward M, Reznick RK. Teaching the surgical craft: from selection to certification. Current Problems in Surgery. 2002;39:573–660. doi: 10.1067/mog.2002.123481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walsh LJ, Chai L, Farah C, Ngo H, Eves G. Use of Simulated Learning Environments in Dentistry and Oral Health Curricula. Health Workforce Australia. 2010 HWARFQ/2010/17. Retrieved July 19, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaufmann CR. Computers in surgical education and the operating room. Ann Chir Gynaecol. 2001;90:141–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Irby DM. What clinical teachers in Medicine need to know. Acad Med. 1994;69:333–342. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199405000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gerzina TM, McLean T, Fairley J. Dental Clinical Teaching: Perceptions of Students and Teachers. J Dent Educ. 2005;69:1377–1384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jensen AR, Wright AS, McIntyre LK, Levy AE, Foy HM, Anastakis DJ, Pellegrini CA, Horvath KD. Laboratory-Based Instruction for Skin Closure and Bowel Anastomosis for Surgical Residents. Arch Surg. 2008;143:852–859. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.143.9.852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suvinen TI, Messer LB, Franco E. Clinical simulation in teaching preclinical dentistry. Euro J Dent Educ. 1998;21:25–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0579.1998.tb00032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burch VC, McKinley D, van Wyk J, Kiguli-Walube S, Cameron D, Cilliers FJ, Longombe AO, Mkony C, Okoromah C, Otieno-Nyunya B, Morahan PS. Career intentions of medical students trained in six sub-Saharan African countries. Education for Health. 2011;24:1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ehizele AO, Azodo CC, Ezeja EB, Ehigiator O. Nigerian dental students' compliance with the 4AS approach to tobacco cessation. J Prev Med Hyg. 2011;52:12–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rees L, Jolly B. Medical education into the next century. In: Rees L, Jolly B, editors. Medical Education in the Millennium. Oxford (UK): Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bligh J. The clinical skills unit. Postgraduate Medical Journal. 1995;71:730–732. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.71.842.730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Omer R, Amir AA, Ahmed AM. An experience in early introduction of clinical teaching in a clinical skills laboratory. Sudanese Journal of Public Health. 2010;5 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peeraer G, Scherpbier AJ, Remmen R, De winter BY, Hendrickx K, van Petegem P, Weyler J, Bossaert L. Clinical Skills Training in a Skills Lab Compared with Skills Training in Internships: Comparison of Skills Development Curricula. Education for Health. 2007;20 Retrieved July 19, 2012. http://www.educationforhealth.net/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maginnis C, Crozon L. Transfer of learning to the nursing clinical practice setting. The Internatioal electronic journal of rural and remote health research, education, practice and Policy. 2010 Retrieved July 19, 2012. http://www.rrh.org.au. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.George JH, Doto FX. A Simple Five-step Method for Teaching Clinical Skills. Fam Med. 2001;33:577–578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKimm J. Giving effective feedback. Brit J Hosp Med. 2009;70:158–161. doi: 10.12968/hmed.2009.70.3.40570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martin N, Fairclough A, Smith M, Ellis L. Factors influencing the quality of undergraduate clinical restorative dentistry in the UK and ROI: the views of heads of units. Brit Dent J. 2010;208:527–531. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2010.498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hesketh EA, Laidlaw JM. Developing the teaching instinct: Feedback. Med Teach. 2002;24:245–248. doi: 10.1080/014215902201409911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chapnick L, Chapnick A. Clinical teaching in the undergraduate clinic-more difficult than it looks. J Can Dent Assoc. 2010;76:a64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ahmed AM. Role of clinical skills centres in maintaining and promoting clinical teaching. Sudanese Journal of Public Health. 2008;3:97–103. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Indian Council of Medical Research, author. Guidelines for good laboratory practices. 2008. Retrieved March 15, 2012. icmr.nic.in/guidelines/GCLP.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Curtis DA, Lind SL, Brear S, Frederick C, Finzen FC. The Correlation of Student Performance in Preclinical and Clinical Prosthodontic Assessments. J Dent Educ. 2007;20:365–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davies BR, Leung AN, Dunne SM. Perceptions of a simulated general dental practice facility - reported experiences from past students at the Maurice Wohl General Dental Practice Centre 2001–2008. Brit Dent J. 2009;207:371–376. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2009.902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]