Abstract

Background

Taenia solium metacestodes/cysts obtained from pig carcasses constitute a primary source for diagnostic tools used for the detection of human cysticercosis. Data on T. solium cyst preparation in Africa is still scarce but required to establish independent reference laboratories.

Objectives

The aim of the present study is a) to present the likely yield of T. solium cyst material by the use of two different preparation methods in the field and b) to investigate its suitability for immunodiagnosis of human cysticercosis.

Methods

In Zambia, Uganda and Tanzania 670 pigs were screened for T. solium infection. Cysts were prepared by ‘shaking method’ and ‘washing method’. Generated crude antigens were applied in a standard western blot assay.

Results

46 out of 670 pigs (6.9%) were found positive for T. solium (Zambia: 12/367, 3.3%; Uganda: 11/217, 5.1%; Tanzania 23/86, 26.7%). Mean values of 77.7 ml whole cysts, 61.8 ml scolices/membranes and 10.9 ml cyst fluid were obtained per pig. Suitability of collected material for the use as crude antigen and molecular diagnostic techniques was demonstrated.

Conclusion

This study clearly shows that T. solium cyst preparation in African settings by simple field methods constitutes an effective way to obtain high quality material as source for diagnostic tools and research purposes.

Keywords: Taenia solium, cysticercosis, neurocysticercosis, antigen, immunoblot

Introduction

Taenia (T.) solium (pork tapeworm) represents an important yet neglected zoonotic parasite in many resource-poor countries worldwide.1,2 Humans harbour adult tapeworms as definitive hosts in the gut, whereas pigs harbour T. solium cysticerci as intermediate hosts in muscles, brain, and other organs. In the case of direct ingestion of T. solium eggs (faecal-oral transmission), humans may become accidental intermediate hosts and develop cysticercosis/neurocysticercosis (NCC). NCC represents the most common helminthic infection of the human central nervous system and has been recognised as a major cause of secondary epilepsy in endemic areas.3,4 In sub-Saharan Africa, it is estimated that between 1.9 and 6.16 million people suffer from NCC (symptomatic and asymptomatic).4 Community-based prevalence studies have demonstrated a wide range of sero-prevalences of human cysticercosis from 6–45% based on various diagnostic techniques.5–9 Moreover in southern African countries T. solium is widely distributed in free-ranging pig populations. Previous reports have indicated a prevalence of porcine cysticercosis in endemic districts between 8.2% and 46.7%.10–13 Human and animal disease together cause societal burden and significant economic loss which amounted in the Eastern Cape Province in South Africa to 19–34 million US$ for the year 2004.14

Since T. solium cysticercosis/NCC represents an emerging public health problem in many parts of the world, massive efforts are being made to improve prevention, diagnosis and treatment in humans and swine.14 For the diagnose of T. solium cysticercosis in humans several serological tests (immunoblot, especially enzyme-linked immunoelectrodiffusion transfer blot [EITB]; antibody-enzyme linked immunosorbent assay [ELISA], antigen-ELISA) are used to confirm clinical and radiological findings.4,5,15,16

Most of the antibody-detecting tests are based on antigen preparations (crude extracts and glycoprotein fractions) from T. solium metacestodes (whole cysts, cyst fluid and scolices/cyst membranes) extracted from pig carcasses.16 Thus far, it has mainly been cysticerci from Latin America and Asia which have been in widespread use. T. solium material from different sub-Saharan countries is rarely available and published methodological procedures for T. solium cyst collection is generally scarce.

In sub-Saharan Africa detailed data on prevalence of human cysticercosis are still lacking in many endemic areas, as are commonly available diagnostic facilities.1 In some African countries, reference laboratories and related research facilities have been newly established within the past years,4,5,17 but most of them are still dependent on antigens provided by European and American institutions, and are not yet ready to undertake routine testing outside their research activities. However, within the African continent shipment of routine samples to distant reference laboratories is not practicable due to high costs and required continuous cooling chain. Consequently, an evaluation of simple and affordable procedures for T. solium cyst collection in rural settings is urgently required. This will facilitate a wider use of routine diagnostic testing within African countries and will enable further large-scale epidemiological studies to be conducted by local authorities/ministries for advanced disease mapping. Moreover, T. solium metacestodes from different geographic regions are also of increasing interest with respect to specific research activities concerning the pork tapeworm (e.g. genotyping, proteomics, diagnostic and therapeutic research). 18,19

Therefore, the aim of the present study was to evaluate T. solium cyst preparation procedures under field conditions in African countries, and to present detailed descriptions of applied methods and yield of obtainable T. solium material. The data provided in this study constitutes an important resource for immunodiagnostic antigen production to be used in new national reference laboratories and research into the impact of T. solium from different African regions.

Material and methods

Ethical statement

Ethical approval for this study (‘Neurocysticercosis in sub-Saharan Africa’) was obtained from the Zambian Biomedical Research Ethics, Lusaka, (Ref.No.: 006-08-08), in Tanzania from the Directorate of Research and Publications, MUHAS, Dar es Salaam (Ref.No.: MU/RP/AEC/Vol.Xii/86) and in Uganda from the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (UNCST), Kampala, (Ref.No.: HS 543). This study was carried out by professional veterinarians adhering to the Zambian, Tanzanian and Ugandan regulations and guidelines on animal husbandry.

Study area and screening of free-ranging pig populations

Fieldwork was carried out from September 2009 through July 2010 in selected districts of Zambia (Gwembe, Katete and Mongu), Uganda (Moyo, Adjumani, Kitgum and Gulu) and Tanzania (Mbulu, Mbozi and Kongwa), during dry seasons. All study sites were characterised by increasing pig rearing, poor infrastructure and a lack of appropriate sanitation facilities and slaughter slabs. Local authorities were informed about all activities in advance and safety trainings were conducted for participating helpers.

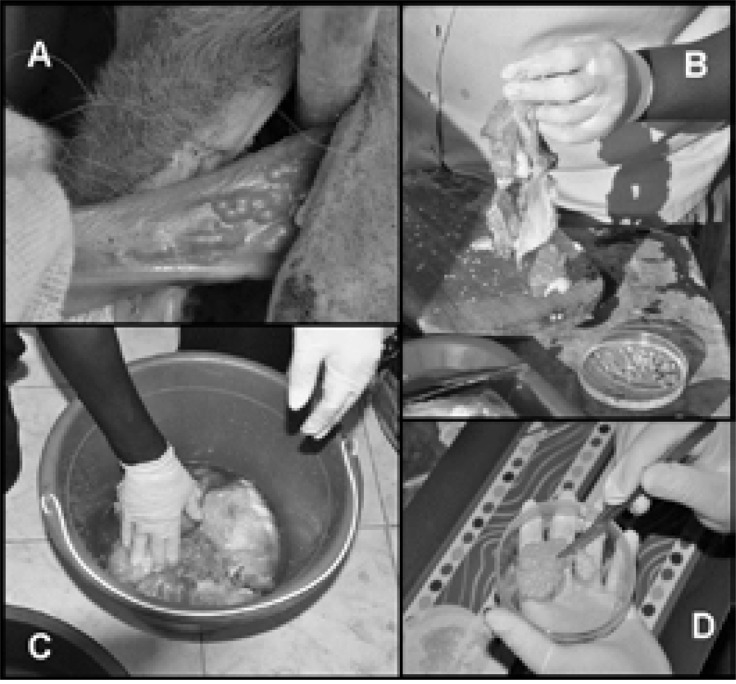

Within the chosen districts we focused on free-ranging pig populations with a high prevalence of porcine cysticercosis, as reported by district veterinarians or described in earlier studies, and used convenience sampling. 10,12 Pigs were caught by local village volunteers, laid on one side and briefly held down. Veterinarians then examined eyelids and performed a lingual inspection by inserting a wooden stick vertically into the mouth and pulling out the tongue with a cotton cloth.10,20 A pig was considered T. solium positive if cysts were visible under the eye lid or/and on the sublingual area of the tongue (Figure 1A). A high intensity of infection was defined as the appearance of more than 15 visible cysts, and visibly enlarged masseters and triceps brachii muscles. Highly-infected pigs more than 6 months of age were selected and purchased from their owners. In the absence of laboratory facilities and nearby slaughter slabs, remote locations were chosen for slaughter and cyst preparation, in order to observe hygienic standards within the possibilities of local circumstances. Selected pigs were slaughtered by local slaughter men under veterinary supervision. All procedures focused on maximizing animal welfare: Rough handling of pigs during examination and transport was strictly avoided. Wooden sticks and cotton cloths were used during tongue examination. Pigs had access to water all the time.

Figure 1.

T. solium metacestode preparation methods.

A, Tongue of T. solium positive pig; B, Shaking method; C, Soaking method; D, Preparation of cyst fluid.

Taenia solium metacestode preparation (‘shaking method’ and ‘soaking method’)

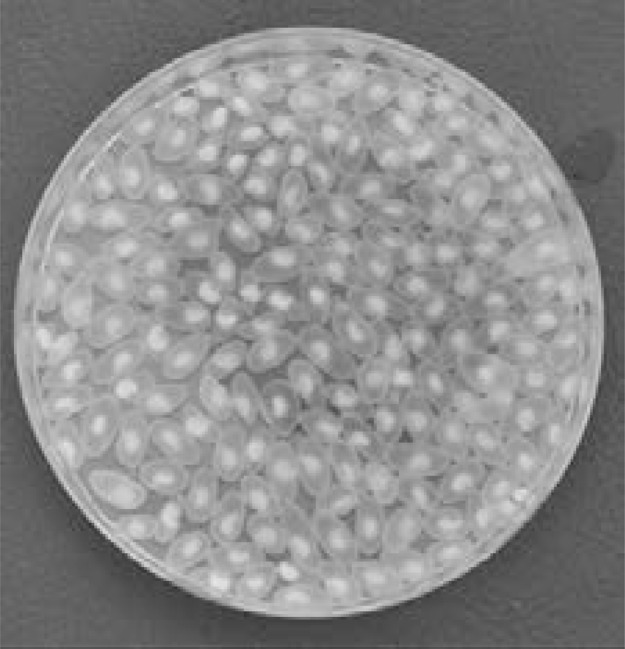

After slaughter, pieces of skeletal muscle were immediately removed and transferred to a tray. The standard procedure was referred to as the ‘shaking method’. Pieces of pork containing the cysts were shaken vigorously by hand until cysticerci fell out (Figure 1B). Three types of T. solium material were collected to be used for different diagnostic and research purposes: whole cysticerci (scolex surrounded by cyst fluid and intact cyst membrane), loose scolices/cyst membranes and cyst fluid. Firstly, whole cysticerci and scolices/cyst membranes were collected separately from the tray with a forceps and placed in different petri dishes containing phosphate buffered saline (PBS; Merck, Germany; Figure 2). Secondly, residual PBS was removed by drying the cysts on a filter paper (Whatman, GE Healthcare, UK) prior to them being transferred into falcon tubes. For fluid extraction, whole cysticerci were cut several times with a scalpel blade in a petri dish. The petri dish was slightly inclined until the fluid ran down on one side (Figure 1D). Subsequently, the fluid was aspirated by a disposable sterile Pasteur pipette (VWR, Germany) and stored in a 50 ml falcon tube.

Figure 2.

T. solium metacestodes in situ.

Whole T. solium metacestodes in PBS after preparation from pig carcass.

In some cases standard procedure was not practicable due to extreme dehydration of the carcass. Pieces of pork had to be soaked in a tub containing 1–2 litres of PBS for up to 15 minutes (referred to as the ‘soaking method'), before being cut into smaller pieces. Soaking and cutting had to be repeated three to five times. Supernatant and muscle tissue were subsequently removed with a cup (Figure 1C). T. solium material remained as sediment and was placed on a tray for sorting. Further processing followed the procedure described as the standard method above.

The volumes of all obtained materials were measured by graduated tubes and were immediately stored on ice packs in cooling boxes for transportation to the next laboratory, where long-term storage was conducted at −20°C. Residual pig carcasses were burnt after the cyst collection, or disposed of pits, if available, to avoid contaminating the environment with cysts from infected pork.

Species confirmation of extracted cyst material

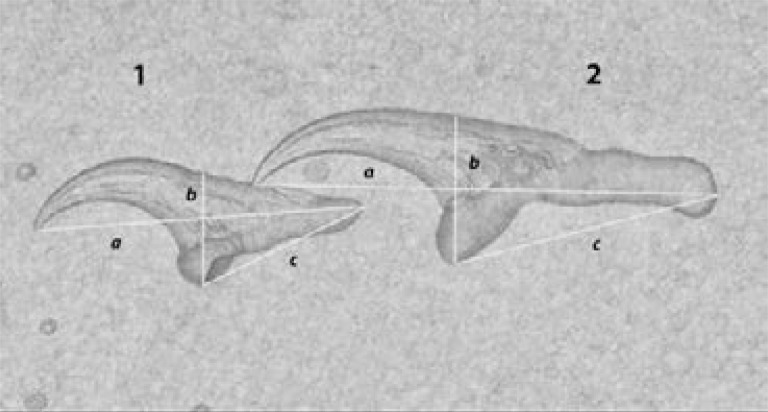

All T. solium material was shipped on dry ice by courier to the Department of Infectious Diseases and Tropical Medicine (DITM), University Hospital, Ludwig-Maximilians University, Munich, and was subjected to confirmatory microscopy and molecular tests for species identification. Three scolices were randomly selected from each pig carcass (total n = 33) and the presence of T. solium-specific hooks was confirmed by microscopic analysis, a technique also suitable to be conducted on site in sub-Saharan Africa (Figure 3).11

Figure 3.

Rostellar hooks of T. solium.

Native microscopy and measuring of rostellar hooks of T. solium.

1: a: 128 µm, b: 47,5 µm, c: 62,5 µm; 2: a: 185 µm, b: 70µm, c: 97,5µm.

DNA was extracted using Quick Gene Tissue Kits (FujiFilm, Tokyo, Japan) according to the manufacturer's protocoll. Polymerase chain reaction of two mitochondrial genes (Cox1- and Cytb-genes) was performed, followed by sequence analysis of the respective genes.21 Amplicons were subsequently sequenced and aligned with reference genes retrieved from GenBank (PubMed, NCBI; Cox1-gene, accession no.: AB066493, FN 995658; Cytb-gene, accession no.: AB066578, AB066575). Specific T. solium primer sets were chosen for full-length amplification of Cox1 (1620bp) and Cytb (1068bp) as described in Nakao et al. (2009).21

Quality control of T. solium material and data analysis

To investigate the suitability of the collected material for immunodiagnosis, crude antigen was generated from T. solium scolices from Zambia, Uganda and Tanzania following the protocol of Gottstein et al. (1986),22 with minor modifications and with addition of a protease inhibitor (cOmplete; Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Immunoblot strips were produced by running each antigen batch on a Tris-Tricine-PAGE gel (4% and 16.5%) following the slightly modified protocol of Schägger et al. (1987).23 For quality assurance and comparison of immunogenicity of the obtained antigen batches from different regions strips were produced by the use of a 0.2 µm Protran nitrocellulose membrane (Wathman; GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK). Subsequently, strips were incubated with 46 confirmed African and 2 European NCC positive and 46 negative sera (25 µl serum per strip) (Figure 4). For the investigation of relevant cross reactions strips from each antigen batch were incubated with three Echinococcus granulosus positive sera.

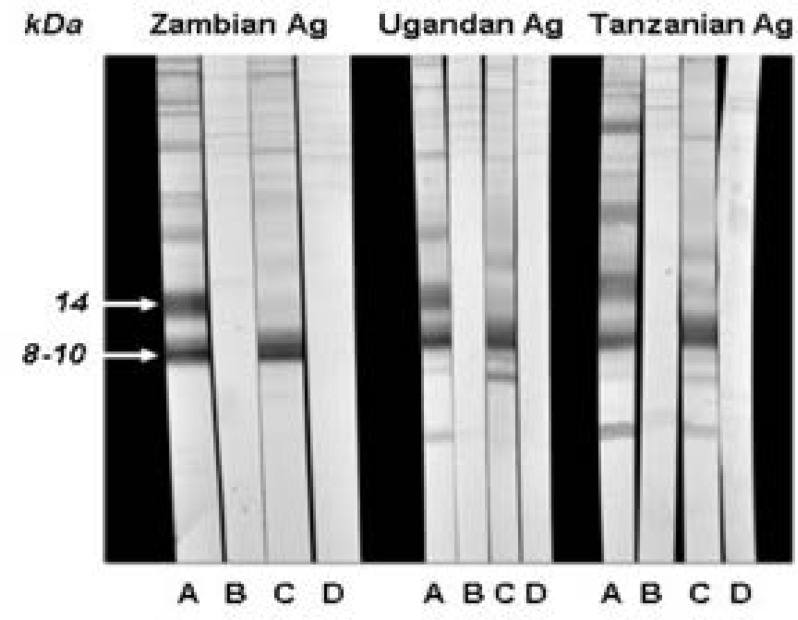

Figure 4.

T. solium crude antigens from different origins.

SDS-PAGE analysis of crude antigen preparations from Zambia, Uganda and Tanzania performed with different sera samples from patients with and without confirmed neurocysticercosis (NCC): African NCC positive serum (A), African NCC negative serum (B), European NCC positive serum (C), European NCC negative serum (D).

Statistical analyses of data on the obtained volumes of T. solium material were performed using Windows Excel 2003 (Microsoft Cooperation, Redmond, USA).

Results

In this study, a total of 670 pigs (Zambia n = 367, Uganda n = 217, Tanzania n = 86) were tested for T. solium infection by lingual examination, as shown in Table 1. Altogether, 46 pigs out of 670 (6.9%) were found positive (Zambia: 12/367, 3.3%; Uganda: 11/217, 5.1%; Tanzania 23/86, 26.7%). Out of the 46 positive pigs finally 16 were selected for cyst preparation (Zambia: 9/12, 2.5%; Uganda: 4/11, 1.8%; Tanzania 3/23, 3.5%) on the basis of high infection intensity.

Table 1.

Results of lingual examinations and T. solium metacestode preparation.

| Zambia | Uganda | Tanzania | TOTAL | |

| Collection period | Nov/Dec 2009 | Feb 2010 | July 2011 | Nov 2009 – July 2011 |

| Preparation method | Shaking | Shaking and soaking |

Shaking | - |

| No. of pigs examined | 367 | 217 | 86 | 670 |

|

T. solium positive pigs (total) |

12 (3.3%) | 11 (5.1%) | 23 (26.7%) | 46 (6.9%) |

| T. solium positive pigs | Gwembe 7/63 | Moyo 1/103 | Mbulu 5/47 | - |

| by lingual examination | Katete 4/98 | Adjumani 2/8 | Mbozi 7/23 | |

| Pigs selected | 9 | 4 | 3 | 16 |

| Whole cysticerci (ml) | 230 (25.5*) | 426 (106.5*) | 587 (195.7*) | 1243 (77.7*) |

| Scolices/cyst membranes (ml) | 286 (31.8*) | 340 (85*) | 363 (121*) | 989 (61.8*) |

| Cyst fluid (ml) | 79 (8.8*) | 85 (21.3*) | 11 (3.7*)** | 175 (10.9*) |

Mean volume (ml) per slaughtered pig.

As our general focus was on collection of whole T. solium metacestodes the total volume of cyst fluid was less in Tanzania.

Out of all collected material, whole T. solium cysticerci represented the largest total amounts (Zambia: 230 ml; Uganda 426 ml; Tanzania: 587 ml) obtained in this study, together with scolices/cyst membranes (Zambia: 286 ml; Uganda: 340 ml; Tanzania: 363 ml), followed by cyst fluid (Zambia: 79 ml; Uganda: 85 ml; Tanzania: 11 ml). The overall mean values of materials collected were 77.7 ml whole cysticerci, 61.8 ml scolices/cyst membranes and 10.9 ml cyst fluid per pig.

The introduction of local authorities to the upcoming activities, safety trainings and selection of infected pigs, lingual examinations and cyst preparation required 4 to 6 days total in each district.

T. solium-specific hooks were identified by microscopy from each selected scolex (n = 33) and repeated sequence analysis confirmed all 33 samples as T. solium. All in-house immunoblot strips generated with Zambian, Ugandan and Tanzanian antigen showed clear diagnostic patterns after incubation with 48 positive reference sera from people suffering from NCC (confirmed by computed tomography and LLGP-EITB in a previous study). The strongest diagnostic bands were found in the 8–10 kDa area, where one or two clear bands appeared in all positive serum panels (Figure 4, C). One additional major band at 14 kDa (Figure 4, A) was shown in 6 out of 48 cases. No specific diagnostic band appeared when strips were incubated with NCC negative (Figure 4, B and D) and Echinococcus granulosus positive sera.

Discussion

The objective of the present study was to evaluate T. solium cyst preparation procedures under field conditions in African countries and to present detailed descriptions of the respective methods and the prospective yield of obtainable T. solium material. Suitability of collected material for immunodiagnosis was proven in a sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) assay by presence of diagnostic banding patterns as previously described,22,24–27 when incubated with confirmed neurocysticercosis serum panels. Obtained low kDa bands in the immunoblot testing are well known and have been described as diagnostic bands in several previous publications.22,24–27 The single additional band at 14 kDa, which was shown in 6 out of 48 cases, has been also described as diagnostic band before.27

This study has several limitations: The percentage of positive tested pigs has to be interpreted carefully and cannot be used as prevalence rates: In our study, pigs were tested by convenience sampling in previous known endemic areas. We chose this sampling method and no cross-sectional design in order to simulate realistic conditions for upcoming African laboratories. Moreover, regarding the comparison of yields of T. solium material obtained by the two different preparation methods we can only state that there was no relevant difference between the two methods based on personal observations. At the time of preparation the focus was on processing all samples as fast as possible into the cooling chain to keep the quality of material for the upcoming antigen production. Therefore no time was available to perform accurate quantification of the obtained material separated by method. Another limitation was that antigens were only evaluated by the use of a standard protocol for T. solium immunoblot strip production and by the use of reference sera obtained from people with confirmed neurocysticercosis. Due to limited funds no directly comparison with the currently accepted gold standard - the LLGP-EITB from the Centres of Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta - was performed.15,22

In our study districts, the collection of T. solium cysts in slaughter slabs was not efficient. We experienced that in rural areas required highly-infected pigs were not purchased by pig traders, therefore rarely reached official slaughter slabs. On the contrary, Dorny at al. (2004) described that in more urban areas screening in slaughter houses can be a reasonable approach to identify positive pigs.28

Lingual examination represents a traditional method commonly used by pig traders to detect cysticercosis in living pigs.29 Although its sensitivity is moderate and many free-ranging pigs have to be screened30, we nevertheless consider lingual examination to be a useful, cost-effective method for identifying highly-infected pigs for T. solium cyst preparation in comparison to the alternative bloodletting and serological confirmation. The number of pigs that have to be tested in order to identify an appropriate animal is not only dependent on the local prevalence of porcine cysticercosis, but also on the availability of detailed information on endemic villages from district veterinarians and local authorities, who are indispensable for a focussed and selective identification process. In addition, the number of pigs that need to be tested depends on the season. Owners are more willing to sell a pig at the end of the rainy season and beginning of the dry season, since the dry season often results in loss of weight of adult pigs.

For lingual examination a commonly observed technique is to puncture the tongue with a metal hook to pull it out. This method should be strictly rejected with respect to animal welfare, and therefore all staff involved in T. solium cyst preparation processes should be previously trained in appropriate pig handling. Only wooden sticks or pig snares are recommended to be used during the screening process. Throughout the present study, trained veterinarians performed all lingual examinations and strictly supervised all handling of living pigs.

Concerning the T. solium metacestode preparation process itself, the standard procedure (‘shaking method’) turned out to be feasible in all the selected study areas in Zambia and Tanzania. In Uganda, however, in 3 out of 4 preparations the standard procedure had to be replaced with the ‘soaking method’. In these instances, pork appeared dried up directly after slaughter, which hampered the acquisition of T. solium material by shaking. However the present study illustrated that both methods described (‘shaking method’ and ‘soaking method’) are easy to perform under field conditions. The final decision on which method is most appropriate can only be made after slaughter, as this choice depends on the hydration status of the pork. Therefore, it is recommended that all equipment required for both methods is available on site during each preparation process. The necessary equipment is widely available and inexpensive, making these techniques extremely useful for local laboratories. Continuous cooling chain and addition of proteinase inhibitors during the cyst preparation process constitute important components to ensure preservation of antigenetic proteins. In the present study inhibitors were not added before the antigen preparation step due to a lack of local availability during the study period. But it would be recommended to be already added to the PBS at the beginning of the cyst preparation process.

Overall, an important finding of the present study was that, when using the described methods, even a single positive, highly infected pig can provide large amounts of T. solium material for antigen production and research purposes (whole cysts: 78 ml; scolices/cyst membranes: 62 ml; cyst fluid: 11 ml). Basic T. solium antigen production procedures, as described by Gottstein et al. (1986)22, provide 40–60 ml purified crude antigen from 2 ml T. solium scolices as source of material. One SDSPAGE gel requires 200–230 µl of described antigen suspension, 10 µl is needed to coat a 96 well ELISA plate, and only one T. solium scolex is required for PCR and sequence analysis. Due to project requirements antigen production and laboratory testing had to be performed at DITM, Germany, in the present study, but can easily be performed in an African laboratory if required equipment (ultrasonicator, centrifuge) and liquid nitrogene is available.

It should be also stated that in this study, the main focus was on collection of whole T. solium cysts, because subsequent molecular analyses had to be performed from scolices obtained from intact cysts.22 Therefore, amounts of loose scolices/cyst membranes and cyst fluid were not maximized in the preparation processes. If a T. solium cyst collection were to focus on cyst fluid or scolices and cyst membranes only, the obtained amounts would almost certainly exceed those collected in this investigation.

As an easy and cheap technique for species identification, microscopy was included in this study also applicable under field conditions in Africa, as well as crude antigen production by following a basic protocol.22 Sophisticated methods (e.g. lentin-lectin glycoprotein production for EITB strips) are too costly for local reference laboratories in sub-Saharan Africa. Although suitability of collected material for the use as crude antigen was clearly demonstrated, further investigations on the impact of antigens from different African regions and its implication for diagnosis are required.

Conclusion

Overall, the present study demonstrates that the above described cyst preparation methods in combination with screening of free-ranging pig populations in endemic rural areas of sub-Saharan Africa are a quick and efficient way to obtain abundant T. solium material as source for immunodiagnostic tests and for research purposes. Data presented in this study provide essential information for establishment of reference laboratories examining porcine and human cysticercosis in sub-Saharan Africa.

Acknowledgements

To the extraordinary support of the technical staff of DITM (Kerstin Helfrich, Erna Fleischmann and Carolin Mengele), Marcus Beissner, Florian Battke (SCIENTIA GmbH — Life Science Services, Munich, Germany) and staff of all African partner laboratories. The authors are also grateful to the district veterinarians and local volunteers of all study districts for their support in the field.

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the projects: VS, ASW and GB. Performed the field survey and laboratory testing: VS, CSS, EOA, CS, GM, SA, CK. Contributed reagents and materials: CSS, EO, WM, CK, TL, GB. Analysed the data: VS. Wrote the paper: VS. Reviewed the paper: CSS, EOA, CS, GM, SA, EO, WM, CK, TL, ASW and GB.

Financial support

This study was funded by the DFG (German Research Foundation) within the research grant (BR3752/1-1) ‘Neurocysticercosis in sub-Saharan Africa’. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.World Helath Organization, author. First WHO report on neglected tropical dieases: working to overcome the global impact of neglected tropical dieases [Electronic version] 2010. http://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/2010report/en/index.html Last acessed September 2013.

- 2.Geerts S, Zoli A, Willingham AL, Brandt J, Dorny P, Preux PM. Taenia solium cysticercosis in Africa: an under-recognised problem. NATO Science Series I Life and Behavioural Sciences. 2002;341:13–23. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Montano SM, Villaran MV, Ylquimiche L, et al. Neurocysticercosis: association between seizures, serology, and brain CT in rural Peru. Neurology. 2005;65:229–233. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000168828.83461.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Winkler AS. Neurocysticercosis in sub-Saharan Africa: a review of prevalence, clinical characteristics, diagnosis, and management. Pathog Glob Health. 2012;106:261–274. doi: 10.1179/2047773212Y.0000000047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Winkler AS, Willingham AL, 3rd, Sikasunge CS, Schmutzhard E. Epilepsy and neurocysticercosis in sub-Saharan Africa. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2009;121:3–12. doi: 10.1007/s00508-009-1242-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vilhena M, Santos M, Torgal J. Seroprevalence of human cysticercosis in Maputo, Mozambique. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;61:59–62. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.61.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanobana K, Praet N, Kabwe C, et al. High prevalence of Taenia solium cysticerosis in a village community of Bas-Congo, Democratic Republic of Congo. Int J Parasitol. 2011;41:1015–1018. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mwape KE, Phiri IK, Praet N, et al. Taenia solium infections in a rural area of Eastern Zambia-a community based study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6:1594. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mwanjali G, Kihamia C, Kakoko DV, et al. Prevalence and risk factors associated with human Taenia solium infections in Mbozi district, Mbeya region, Tanzania. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7:2102. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sikasunge CS, Phiri IK, Phiri AM, Siziya S, Dorny P, Willingham AL., 3rd Prevalence of Taenia solium porcine cysticercosis in the Eastern, Southern and Western provinces of Zambia. Vet J. 2008;176:240–244. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2007.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boa ME, Bøgh HO, Kassuku AA, Nansen P. The Prevalence of Taenia Solium Metacestodes in pigs in Northern Tanzania. J Helminthol. 1995;69:270. doi: 10.1017/s0022149x00013997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ngowi HA, Kassuku AA, Maeda GEM, Boa ME, Carabin H, Willingham AL., 3rd Risk factors for the prevalence of porcine cysticercosis in Mbulu District, Tanzania. Vet Parasitol. 2004;120:275–283. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2004.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Waiswa C, Fèvre EM, Nsadha Z, Sikasunge CS, Willingham AL. Porcine Cysticercosis in Southeast Uganda: Seroprevalence in Kamuli and Kaliro Districts. J Parasitol Res. 2009;2009:375493. doi: 10.1155/2009/375493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carabin H, Krecek RC, Cowan LD, et al. Estimation of the cost of Taenia solium cysticercosis in Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Trop Med Int Health. 2006;11:906–916. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2006.01627.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsang VC, Brand JA, Boyer AE. An enzyme-linked immunoelectrotransfer blot assay and glycoprotein antigens for diagnosing human cysticercosis (Taenia solium) J Infect Dis. 1989;159:50–59. doi: 10.1093/infdis/159.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deckers N, Dorny P. Immunodiagnosis of Taenia solium taeniosis/cysticercosis. Trends Parasitol. 2010;26:137–144. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Phiri IK, Ngowi H, Afonso S, et al. The emergence of Taenia solium cysticercosis in Eastern and Southern Africa as a serious agricultural problem and public health risk. Act Trop. 2003;87:13–23. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(03)00051-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee EG, Kim SH, Bae YA, et al. A hydrophobic ligand-binding protein of the Taenia solium metacestode mediates uptake of the host lipid: Implication for the maintenance of parasitic cellular homeostasis. Proteomics. 2007;7:4016–4030. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200700332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sciutto E, Martinez JJ, Huerta M, et al. Familial clustering of Taenia solium cysticercosis in the rural pigs of Mexico: hints of genetic determinants in innate and acquired resistance to infection. Vet Parasitol. 2003;116:223–229. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2003.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mutua FK, Randolph TF, Arimi SM, et al. Palpable lingual cysts, a possible indicator of porcine cysticercosis, in Teso District, Western Kenya. J Swine Health Prod. 2007;15:206–212. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakao M, Okamoto M, Sako Y, Yamasaki H, Nakaya K, Ito A. A phylogenetic hypothesis for the distribution of two genotypes of the pig tapeworm Taenia solium worldwide. Parasitology. 2002;124:657–662. doi: 10.1017/s0031182002001725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gottstein B, Tsang VCW, Schantz PM. Demonstration of species-specific and cross-reactive components of Taenia solium Metacestode antigens. Am J Trop Medicine Hyg. 1986;35:308–313. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1986.35.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schägger H, Jagow G. Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins in the range from 1 to 100 kDa. Analytical Biochemistry. 1987;166:368–379. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90587-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hancock K, Khan A, Williams FB, et al. Characterization of the 8-kilodalton antigens of Taenia solium metacestodes and evaluation of their use in an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for serodiagnosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:2577–2586. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.6.2577-2586.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ferrer E, Sanchez J, Milano A, et al. Diagnostic epitope variability within Taenia solium 8 kDa antigen family: implications for cysticercosis immunodetection. Exp Parasitol. 2012;130:78–85. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2011.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang HJ, Chung JY, Yun D, et al. Immunoblot analysis of a 10 kDa antigen in cyst fluid of Taenia solium metacestodes. Parasite Immunol. 1998;20:483–488. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3024.1998.00179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Assana E, Kanobana K, Tume CB, et al. Isolation of a 14 kDa antigen from Taenia solium cyst fluid by HPLC and its evaluation in enzyme linked immunosorbent assay for diagnosis of porcine cysticercosis. Res Vet Sci. 2007;82:370–376. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dorny P, Phiri IK, Vercruysse J, et al. A Bayesian approach for estimating values for prevalence and diagnostic test characteristics of porcine cysticercosis. Int J Parasitol. 2004;34:569–576. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2003.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sato MO, Yamasaki H, Sako Y, et al. Evaluation of tongue inspection and serology for diagnosis of Taenia solium cysticercosis in swine: usefulness of ELISA using purified glycoproteins and recombinant antigen. Vet Parasitol. 2003;111:309–322. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4017(02)00383-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]