Abstract

Historically, the central nervous system (CNS) has been considered to be an immunologically privileged site within the body (Bailey et al., 2006; Galea et al. 2007; Engelhardt, 2008; Prendergast and Anderton, 2009). By definition, immunologically privileged sites, to include the brain, cornea, testis, and pregnant uterus, have a reduced/delayed ability to reject foreign tissue grafts compared to conventional sites within the body, such as skin (Streilein, 2003; Bailey et al., 2006; Carson et al., 2006; Mrass and Weninger, 2006; Kaplan and Niederkorn, 2007). In addition and conversely, tissue grafts prepared from immunologically privileged sites have increased survival, compared to tissue grafts prepared from conventional sites, when implanted at conventional sites (Streilein, 2003). The imune privilege of the CNS has been shown to be confined to the parenchyma, whereas the immune reactivity of the meninges and the ventricles, containing the choroid plexus, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and the circumventricular organs, is similar to conventionalsites (Carson et al., 2006; Engelhardt, 2006; Galea et al., 2007). This confinement of the imm une privilege to the parenchyma has also been demonstrated for experimental influenza virus infection in which confinement of the infection to the brain parenchyma did not result in efficient immune system priming whereas infection of the CSF elicited a virus-specific immune response comparable to that of intranasal infection (Stevenson et al. 1997). An important functional aspect of immune privilege is that damage due to the immune response and inflammation is limited within sensitive organs containing cell types that regenerate poorly, such as neurons within the brain (Mrass and Weninger, 2006; Galea et al.. 2007; Kaplan and Niederkorn, 2007).

Immune privilege is applicable to both innate immune function within the CNS, discussed in Chapter 9, and adaptive immune function within the CNS, which willbe discussed here in relation to viral infection. Originally immune privilege of the brain was thought to be absolute and was attributed wholly to the blood-brain barrier (BBB) (Galea et al., 2007; Engelhardt, 2008; Prendergast and Anderton, 2009). These views of immune privilege have changed over time as evidence of immune function within the CNS has been demonstrated: The CNS is capable of mounting an effective immune response, although the response is unique compared to conventional sites (Bailey et al., 2006; Engelhardt, 2006, 2008). Currently, immune privilege is understood to be the regulation of immunologic components into and within the CNS rather than the complete absence of them due to the BBB (Carson et al., 2006; Galea et al., 2007).

Immune privilege of the CNS may be maintained through the coordinated efforts of multiple mechanisms. One of these mechanisms is the BBB, which is a complex anatomical structure that functions immunologically to limit the movement of inunune cells into the CNS (Bailey et al., 2006; Carson et al., 2006). At the capillary level the blood is separated from the parenchyma by vascular endothelial cellst pericytes, and the glia limitans, made up of astrocytic endfeet (Carson et al., 2006; Bechmann et al., 2007). At the pre- and postcapillary level, the vascular endothelial cell layer is separated from the glia limitans by pericytes, the media, made up of smooth-muscle cells, and the Virchow-Robin space, in which perivascular macrophages, other perivasculnr cells, and T cells occur (Carson et al., 2006; Bechmann et al.. 2007). At the capmary level regulation of rhe permeability of the BBR may be through the organization of the intercellular tight junctions between the brain's capillary endothelial cells and the interactions between tight junctions and signaling molecules (Pachter et al., 2003). At the pre- and postcapillary level, regulation of the permeability of the BBB may be at the level of the glia limitans (Bechmann et al., 2007). Studjes have shown that penetration of the glia limitans by T cells requires the presence of macrophages within the perivascular space as a lack of macrophages results in T-cell accumulation within the Virchow-Robin space (Bechmann et al., 2007). The BBB and other mechanisms involved in maintaining immune privilege, including restricted immune surveillance, the lack of lymphatic vessels, low expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules, and the intrinsic immunosuppressive properties of the CNS, will be discussed further below in the context of adaptive immune responses to viral infection of the CNS. Importantly, the integrity of the BBB and immune privilege arc not preserved in an inflamed CNS, such as is the case in viral encephalitis (Pachter et al., 2003; Galea et al., 2007; Prendergast and Anderton, 2009).

VIRAL INFECTION

Viral pathogenesis in general is discussed in Chapters 7 and 8, and for specific viruses in Chapters 11 through 33; however, viral pathogenesis will be discussed briefly here. The route of infection of a host varies with the virus and can be via mucosal membranes of the respiratory tract, gastrointestinal tract, urogenital tract or the conjunctiva of the eye or by breaching the skin (arthropod injection, animal bite, or needle-stick) (Nathanson and Murphy, 2007). Viral entry into the host via any of these routes induces a systemic immune response, one side-effect of which is an increase in immune surveillance of the CNS (discussed in detail below) even in the absence of CNS infection (Griffin, 2003).

Once inside the host, viruses can spread from the initial site of infection to the CNS via either the hematogenous route (viremia) or via the peripheral nervous system and the two modes of spread are not mutually exclusive (Nathanson and Murphy, 2007). Viruses can circulate in the blood either associated with cells (monocytes, B cells, T cells) or free in the plasma, or both, depending on the virus. Dissemination of viruses from the blood to the CNS can be via infected T cells or monocyte which traffic into the CNS, via infection of the brain's capillary endothelial cells with viral replicat ion within the e cells, via transport of virus across the brain's capillary endothelial cells (transcytosis) without viral replication within these cells, via induction of proinflammatory cytokincs (innate immunity) that increase the permeability of the BBB, or via the CSF. Viruses that spread via the peripheralncnous system do so within the dendrites and axons of the nerve fibers, and virus replicates in either the cytoplasm or the nucleus of the neurons (Nathanson and Murphy, 2007). Transport of the virus is from neuron to neuron via the synapses (Griffin, 2003). No matter the route of viral entry into the CNS, rapid, tightly controlled immune responses are required to contain the viral infection within the CNS while, at the same time, limiting tissue damage (Savarin and Bergmann, 2008).

ADAPTIVE IMMUNE RESPONSE: GENERAL

The adaptive immune response is an antigen-specific immune response that takes days to weeks to develop (Nathanson and Ahmed, 2007; Nathanson and Biron, 2007). The initiating event in the induction of the adaptive inunune response is the activation of naïve T cells through antigen presentation (Pachter et al., 2003; Galea et al., 2007). Dendritic cells (DCs), which are professional antigen-presenting cells (APCs), or macrophages and B cells can endocytose viral material, intracellularly process this material, and present smaller peptide fragments as antigens bound within the cleft of MHC class II molecules on the surface of APCs to naïve CD4+ T cells (Carson et al, 2006). Antigen processed and presented in this way is processed via the exogenous pathway and results in antigens in the range of 10-30 amino acids in size (Babbitt et al., 1985; Nathanson and Ahmed 2007). Any virus-infected cell that expresses MHC class I molecules on its surface can serve as an APC and present antigen and activate naïve CDS+ T cells (Carson et al., 2006). Antigen processed and presented in this way is processed via the endogenous pathway and results in antigens in the range of 9-11 amino acids in size (Bjorkman et al., 1987a, b; Nathanson and Ahmed, 2007). The structure of the MHC class I and II molecules has been described in detail elsewhere (Mcfarland and Mcfarlin, 1989). The peptide antigen bound to the MHC molecule is recognized by a T-ccll receptor (TCR) on the surface of the naive T cell (Pachter et al., 2003; Carson et al., 2006). Individual T cells express TCRs specific for individual peptide antigens (Haskins et al., 1983; Mcintyre and Allison, 1983; Meuer et al., 1983a, b; Nathanson and Ahmed, 2007). Activated APCs must also express costimulatory molecules in conjunction with the MHC molecules for effectivc activation of T cells to occur (Pachter et al., 2003; Carson et al., 2006). Examples of costimulatory molecules include B7.1 (CD80) and 87.2 (CD86), both of which internet with CD28 on T cell, and CD40, which interacts with CD40 ligand on T cells (Becker, 2006; Carson et al., 2006). Activated T cells proliferate, differentiate, and produce cytokines (Fig. 10. 1) (Carson et al., 2006).

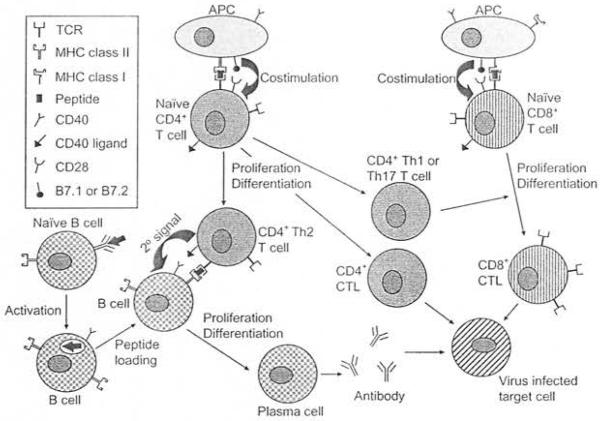

Fig. 10.1.

The adaptive immune response. Antigen-presenting cells (APCs) present antigen bound to the major bistocompatibility complex (MHC) class II or class I molecules to activate naïve CD4 + or CD8 + T cells, respectively, through both recognition of the bound antigen by the T-cell receptor (TCR) and costimulation. Activated CD4+T cells proliferate and differentiate into either CD4+ T-helper2 (Th2) cells which promote proliferation and differentiation of CD8+ B cells, CD4+ T-helper1 (Th1) or T-helper 17 (Thl 7) cells, which promote proliferation and differentiation of CD8 + T cells, or CD4 +cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL), effector cells capable of lysing virus-infected cells. Activated CD8 + T cells proliferate and differentiate into CD8+ CTL, also capable of lysing virus-infected cells. Naïve B cells are activated following interaction of surface antibody with antigen. Activated B cells can function as APCs and can proliferate and differentiate into plasma cells following interaction with CD4+ Th2 cells. Individual plasma cells secrete antibody specific for the same individual viral antigen that was recognized by the naive B cell.

Activated CD4+ T cells function as helper cells to naive B cells and CD8+ T cells, promoting proliferation of these cells in response to antigen (Nathanson and Ahmed, 2007). CD4+ T-helper 1 (Thl) cells help drive the clonal expansion of activated CD8+ T cells through secretion of the cytokines interferon (IFN)-y and interleukin (IL)-2 (Mosmann et al., 1986). CD4+ T-helper 2 (Th2) cells help drive the clonal expansion of B cells through secretion of the cytokfoes IL-4, IL-5, and IL-21 (Mosmann et al., 1986). CD4+ T-helper 17 (Th17) cells are a more recently discovered subset of CD4+ T cells that secrete IL-17 and help drive the clonal expansion of activated CD8 + T cells (Aggarwal et al., 2003; Happel et al., 2003). In addition to the secreted cytokines, CD4+ T-helper cells also express surface molecules able to interact with molecules on the surface of B cells and CD8+ Tcells that are responding to antigen, thus supplying a non-specific secondary signal for clonal expansion of B cells and CD8+ T cells (Fig. 10.1). The secondary signal for CD4+ Th2 cells interacting ,with B cells is the interaction of CD40 on B cells with CD40 ligand on CD4+ Th2 cells (Lederman et al., 1992; Noelle et al. 1992; Nathanson and Ahmed. 2007). Jn contrast to their hdper function human CD4+ T cells have also been shown to be directly cytotoxic, lysing infected cells (Fig. 10. 1) through the actions of perforin, which produces pores in the plasma membrane of the infected cell, and granzymes, serine esterases that enter the infected cell through the perforin pore and trigger apoptosis (Appay et al., 2002). In humans, these CD4+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) are present in low numbers in the serum under normal healthy conditions and expand under conditions of chronic viral infection (Appay et al., 2002). When the host is able to clear virus, a population of virus-specific CD4+ memory T cells is maintained for an indefinite period of time (Fig. 10.2) (Nanan et al., 2000; Naniche et al., 2004; Nathanson and Ahmed, 2007).

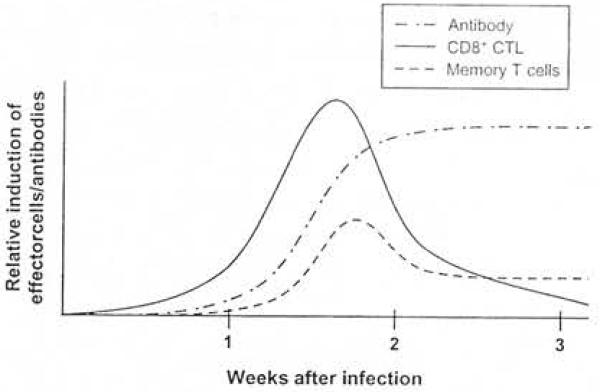

Fig. 10.2.

A generalized timeline of the adaptive immune response to primary infection with a virus that is nonnally cleared from the host. Virus-specific COS+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) appear within I week, peak at 2-3 weeks, and are undetectable by 3-6 weeks after infection. Antibodies of the immunoglobulin (lg) M class appear within 1 week and are undetectable by 3 months after infection, while antibodies of the lgG class appear around 2-4 weeks, peak at 3-6 months after infection, and thereafter slowJy wane. Populations of virus-specific CD4+ and CD8 + memory T cells persist for the lifetime of the host.

Activated CD8 + T cel1s, which have interacted with antigen-MHC class I on APCs and CD4+ Thi or Thl7 cells, function as effector cells of the cellular immune response following proliferation and differentiation (Nathanson and Ahmed 2007). These effector cells, termed CD8+ CTL arc also able to tyse infected cells (Fig. 10.1) via perforin and granzymes (Podack and Konigsberg, 1984; Podack et al., 1985; Masson et al., 1986). CDS + CTLs also secrete cytokines, such as IFNy, I L-2 and tumornt:crosis factor (TNF)-a, that runction either to initiate apoptosis or to attract additional inflammatory cells to the area containing viral material. The secretion of cytokines from CD8+ CTI.s can also result in the clearance of intracellular viral RNA and proteins from infected cells without lysiS of the cells via a not well-understood mechanism (Tishon et al., 1993; Nathanson and Ahmed, 2007). In most cases, recognition of infected cells by CD8+ CTLs is an antigen-MHC class I-dependent process (Kang and McGavern, 2009). The relative contribution to viral clearance made by the two effector functions of CD8+ CTLs, cytolysis via perform and cytokine secretion, varies from virus to virus (Nathanson and Ahmed, 2007). Effector CD8+ CTLs are not maintained at high levels within the host after viral clearance, but a residual population of virusspecific CD8 + memory T cells persist s for the lifetime of the host (Fig. 10.2) (Nanan et al. 2000; Naniche et al., 2004; Nathanson and Ahmed, 2007).

Regulatory T cells (fregs) are a subset of T cells capable of suppressing immune responses through the secretion of negative regulatory (anti-inflammatory) cytokines, such as IL-10 and transforming growth factor-β (Mrass and Weninger, 2006; Trandem et al., 2010). The suppression of immune responses can occur at sites of inflammation (the brain) or, more prominently, in draining lymph nodes (cervical lymph nodes), and suppression includes decreasing effector T-cell proliferation, DC activation, and proinflammatory cytokine/chemokine production (Trandem ct al., 2010). Tregs are characterized by the surface expression of C4+ CD25 + and intracellular expression of forkhead box P3. Tregs may play a very important role in preventing immunopathology, po sibly by diminishing the infiltration of effector T cells into the CNS (Trandem et al. 2010). In a study examining herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection of the CNS, it was found that increasing the numbers of Tregs in the periphery and brain caused a decrease in the number of virus-specific CD8+ T cells in the brain and an accumulation of virus-specific CD8+ T cells in the draining lymph nodes and spleen, suggesting that Tregs limited the migration of the effector cells from the secondary lymphoid organs to the CNS (Sheridan and Beck, 2009). However , the actions of Tregs may also affect viral clearance, resulting in viral persistence (Frandem et al., 2010).

γδ T cells are a subset of T cells with unique features (Wang et al., 2003). They are limited in TCR diversity and are not MHC-restricted. They can be found in lymphoid tissue, peripheral blood, and epithelial and mucosa) sites. γδ T cells can also produce either Th 1- or 11-type cytokines and have been suggested to play an early effector function role in antiviral immune responses, possibly through the production of IfN-y (Wang et al., 2003).

Natural killer T (NKT) cells are a subset of T cells that are CD id-restricted and share some surface molecules with NK cells, a component of the innate immune system (Grubor-Bauk et al., 2003, 2008; Tsunoda et al., 2008). CDI molecules are MHC class I-like molecules that have the ability to bind and present lipid and glycolipid as antigen. NKT cells express either a restricted TCR consisting of a single invariant ex chain paired with either a single invariant P chain in humans or with any of three invariant β-chains in mice (type I) or a more diverse TCR (type II). Upon activation, NKT cells produce cytokines, to include IFN-y and IL-4. Animal studies with neurotropic viruses have suggested that NKT ceJis (both type I and II), like ro T cells, play an early effector function role in antiviral immune responses, possibly acting as a link between innate and adaptive immunity (Grubor-Bauk et al., 2003, 2008; Tsunoda ct al., 2008).

Naive B cells express, on their surface, antibod y specific for an individual antigen (Nathanson and Ahmed 2007). The structure, ciasses, functions, and genetic rearrangement of antibod ies have been described in detail elsewhere (Sadiq et al., 1989). Interaction of the surface ant ibody on naive B cells with antigen activates the 8 cells (Unanue, 1971; Hammcrling et al., 1973; Nathanson and Ahmed, 2007). Activated B cells can function as APCs and can prolifcrate and differentiate into plasma cells following interaction with CD4+ Th2 cells. Individual plasma cells secrete antibody specific for the same individual antigen that was recognized by the naïve B cell (Fig. 10. 1) (Makela, 1970; Walters and Wigzell, 1970). Antibody molecules. the effector molecules of the humoral immune reponse, recognize proteins, carbohydrates, or nucleic acids as antigens. The proteins, carbihydrates, or nucleic acids as antigens. The antigenic portions of proteins can be recongnized either in a linear or a conformational arrangement on native, not processed, proteins(Fujinami et al., 19830. Antiviral anti-bodies use several different mechanisms for defense of the host. First, antibodies can render the virus noninfectious by binding to and neutralizing the virus either by preventing attachment of the virus to receptors on permissive host cells or by interfering with viral entry into the permissive host cells and uncoatmg (Wetz, 1993). Second, viral antigen-antibody complexes can activate complement, a component of the innate inunune-system, which in turn can coat the virus with epsonin, in process termed opsonization, the increasm the efficiency of phagocytosis of the vols (Jahrling et al., 1983; Boackle et al., 1998). Finally, through interaction of the Feportion of the antiviral antibody with a receptor on NK cells, the antiviral antibody can initiate a cytolytic attack by the NK cells on virus-infected cells bearing the viral antigen to which the antiviral antibody is specific, a process termed antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytolysis (ADCC) (Okabe et al., 1983). The production of virus-specific antibody is maintained at a considerable level following clearance of the virus from the host, most likely due to the presence of long-lived plasma cells in the bone marrow and the presence of memory B cells (Slifka et al., 1995, 1998; Nathanson and Ahmed, 2007). The continued production of virus-specific antibody maintains serum antibody levels which provide protective immunity aoainst reinfection (Tschen et al., 2006). In response to reflection, memory B cells rapidly expand and differentiate into virus-specific antibody-producing plasma cells (Tschen et al., 2006).

The end result of activation of the adaptive immune response is the production of cells (cellular immune response) and antibodies (humoral immune response) specific for antigenic determinants expressed by the invading pathogen (Nathanson and Ahmed, 2007). Vir us infection simultaneously induces both cellular and humoral immune responses, the balance of which is determined by the proportion of Th I and 11 cells taking part in the immune response. During primary viral infection, the antibody response, which is most effective against free virus, develops more slowly than the CTL response, which is most effective against virus-infected cells. In general, the CTL respo nse plays a more important role in controlling and clearing virus during pr ima y viral infection, while the antibody response plays a more importan t role in protecting against viral reinfection due to a very rapid recall response following re-expo sure to antigen (Lukacher et al., 1984; Zinkernagel et al., 1996; Kuroda et al., 1999; Lawrence et al. 2005). Approximately 109 different specificities can be encoded by the cells and antibodies due ta the rearrangement of genetic determinants that occurs during maturation of T cells, in the thymus, and B cells, in the bone marrow, resulting in the expression of of individual TCRs and antibodies with specificities for individual antigens (Nathanson and Ahmed, 2007).

ADAPTIVE IMMUNE RESPONSE: OUTSIDE THE CNS

Outside ofthe CNS, activation of the naive Tce11s occurs in T-cell zones of drain ing lymph nodes and in the spleen following transport of antigen from the immune-challenged site to and tluough the draining lymph nodes and to the spleen (Galea et al., 2007; Nathanson and Biron, 2007). The antigen can be transported either in DCs (cellular route) or as soluble antigens in the fluid phase (fluid route) (Galea et al., 2007). In general, for a virus that is normally cleared from a host within weeks to months, virus-specific CD8+ CTLs appear within 1 week, peak at 2-3 weeks, and are undetectable by 3-6 weeks after infection (Fig. 10.2) (Nathanson and Ahmed, 2007). Once activated, T cells within the CNS can detect CNS antigens as readily as activated T cells can detect antig ens in other tissues (Carson et al., 2006).

Activation of naive B cells occurs in regional lymph nodes, following encounter with antigen, after which B cells undergo cJonal expansion within extrafollicular foci and germinal centers (Tschen et al., 2006). Germinal center B cells undergo affinity maturation and differentiate into plasma cells and memory B cells (Tscben et al., 2006). Antibodies are then produced and secreted by plasma cells present in the bone marrow, lymph nodes, spleen, and mucosa-associated lymphoid ti ssues (MALT) (Nathanson and Ahmed, 2007). Plasma cells in the bone marrow, lymph nodes, and spleen secrete the immunoglobulin (lg) G, IgM and IgA classes of antibodies into the serum, while plasma cells in the MALT secrete the TgG and lgA classes of antibodies into the mucosal fluids. Different classes of antibodies respond differently to viral infection, but in general lgM appears in the serum within 1-2 weeks and is undetectable by 3 months after infection, whereas IgG appears in the serum at around 2-4 week s, peaks at 3-6 months after infection, and thereafter slowly wanes and can persist at low levels for the lifetime of the host (Fig. 10.2) (Nathanson and Ahmed 2007).

ADAPTIVE IMMUNE RESPONSE: INSIDE THE CNS

Immune surveillance of the CNS parcnchyma occurs under normal physiologic condition s and involves a minimal number of immune cells crossing a normal BBB (Mrass and Weninger, 2006; Pedemoote et al. 2006; Engelhardt, 2008; Prendergast and Anderton. 2009). DCs a re not presen t in the normal bra in parenchyma under physiologic cond itions; however, DCs are detectable within affected bra in parenchyma durin g in flammat ion . T cells enter the CNS parenchyma under non-inflammatory cond itions to perform immune surveillance, though the numbers are low compared to other tissues (Pedemonte et al., 2006). The T cells that perform this function are thought to be central memory T cells, memory T cells that primarily migrate through the secondary lymphoid organs as opposed to effector memory T cells that primarily migrate through the periphery (Mrass and Weninger, 2006; Pedemonte et al., 2006). CD8 + CTI..s are very low or absent from the normal brain parenchyma under physiologic conditions, but they can be rapidly recruited to an infected brain (Pedemonte et al., 2006). Activated B cells, on the other hand, have been shown to traffic across the normal BBB and, upon contact with antigen under non-inflammatory conditions, can be retained within the CNS, can di fferentiate into plasma cells, and can synthesize intrathecal antibody, thus suggesting that immune privilege involves regu lat ion of T-cell responses but not antibody responses within the CNS (Knopf et al., 1998). T and B cells that have gained entry into the CNS paren chyma during the course of normal immune surveillance can leave through the cribriform plate which gives access to the nasal mucosa and the cervical ' lymph nodes (Goldmann et al., 2006).

Inside the normal CNS, transport of ant igen from the parencbyma to the secondary lymph organs, the cervical lymph nodes in this case, is restricted, but not completely blocked, due to a lack of a traditional lymphatic system within the CNS (Bailey et al., 2006; Carson et al., 2006; Galea et al., 2007). Despite the lack of a traditional lymphatic system, 14-47% of antigen injected into the CNS transits to the cervical lymph nodes (Cserr and Knopf, 1992; Cserr et al., 1992). Soluble antigens in the interstitial fluid phase can transit out of the CNS via the cribriform plate and into the nasal mucosa and thus into the cervical lymph nodes (Harling-Berg et al., 1989; Bailey et al., 2006; Carson et al, 2006; Pedemonte et al., 2006; Galea et al., 2007; Kang and McGavern, 2009). The soluble antigens can also be taken up by DCs present in areas of the CNS, such as the meninges and CSF, that are outside of the region of immune privilege and be transported to the cervical lymph nodes (Carson et al ., 2006; Pedemonte et al. 2006, Galea et al., 2007). This transport of antigen from the CNS to the cervica l lymph nodes, no matter the exact mechanism, was clearly demonstrated based on the resultant activation of B cells and product ion of antigen-speci fic antibodies wit hin the cervical lym ph nodes (Harling-Berg et al., 1989). A lternately, ant igen can transit out of the CNS via the arachn o id villi to the blood and thus reach the spleen (Harling-Berg et al., 1989; Gordon et al., 1992).

The only resident cells within the CNS parenchyma that can funct ion to any great extent as APCs are microglial cel ls, which represent 10-20% of the bra in parenchyma (Hickey and Kimura, 1988; Pedemonte et al., 2006; Steel et al., 2009). DCs, though not present under steady-state conditions, can be recruited into the inflamed CNS parenchyma from the periphery, most likely through the interactions of chemokine ligands and receptors (Pedemonte et al ., 2006). Peripheral DCs have been shown to play an important role in both the accumulation of clonally expanded CDS + virus-specific T cells within the CNS and in viral clearance from the CNS during viral encephalitis (Steel et al., 2009). It is somewhat controversial as to whether APCs bearing antigen can m igrate out of the CNS parenchyma to the cervical lymph nodes. While some groups describe a lack of cell-mediated antigen drainage to the cervical lymph nodes from the brain parenchyma (Galea et al., 2007), other groups note its presence, at least in the case of injected bone marrow-derived DCs (Carson et al., 1999; Karman et al., 2004a, b; Kang and McGavern, 2009). In one case where cell-mediated antigen drainage to the cervical lymph nodes has been noted, migration of DCs from the CNS parenchyma to the cervical lymph nodes induced act ivated T cells to preferentially home to and accumulate in the CNS (Karman et al ., 2004b). It remains unknown as to whether microglia can migrate out of the CNS parenchyma and present antigen within the cervical lymph nodes (Karman et al., 2004b). APCs retained within the CNS parenchyma most likely play an important role in the continued stimulation of activated T cells within the CNS (Kang and McGavern, 2009).

Priming/immune activation and clonal expansion of virus-specific effector cells of the adaptive immune response following acute viral infection of the CNS primarily occur in the periphery (Marten et al., 2003). The cervical lymph nodes and spleen have been implicated as playing a role based on examination of the kinetics of expansion and traffick ing of both virus-specific CD8+ CTLs (Marten et a l., 2003) and virus-specific ant ibody-secreting cells (Tschea et al., 2002) following CNS infection . Others have noted the formation of ectopic or tertiary lymphoid follicle-like stru ctures, containing 8 cells. T cells, plasma cells, and follicular DCs, within the meninges, but not the parenchyma, of the CNS, under conditions of chronic neuro inf1ammation, which may function to a limited extent as a location within the CNS where A PCs can activate T or 8 cells (Serafini et al.. 2004; Pedemontc et al., 2006; Galea et al., 2007; Engelhardt, 2008). Any role for ectopic lymphoid follicle-like stru ctu res in viral infection of the CNS has yet to be determined.

Getting into the CNS

Factors that influence the movement, from the periphery, across the BBB and into the CNS parenchyma, of effector cells of tbe adapt ive immune response are many and varied (Pachter ct al., 2003; Savarin and Bergmann, 2008; Prendergast and Anderton, 2009). Upregulation of cell adhesion molecules, to include seJectins, integrins and their ligands, increased activity of matrix metalloproteinases (.MM Ps) and increased expression of chemokines and proin flammatory cytokines an contribute to this movement (Pachter et al., 2003; Savarin and Bergmann, 2008; Prendergast and Anderton, 2009). This movement of effector cells of the adaptive immune response into the CNS is termed diapedesis (Banks and Erickson, 2010) and is antigen-independent (Pachter et al., 2003; Savarin and Bergmann, 2008).

Discrete steps involving specific interactions between molecules on the surface of the effector cells of the adaptive immune response and molecules on the surface of the vascular endothelial cells describe the movement of effector cells from the periphery into the CNS parenchyma (Pachter et al., 2003; Engelhardt, 2006, 2008; Pedemonte et al., 2006; Prendergast and Anderton 2009). These steps are termed tet hering, integri.n activation firm adhesion, and transmigration/diapedesis Fig. 10.3) (Engelhardt, 2006, 2008; Mrass and Weninger 2006; Prendergast and Anderton, 2009). The initial tethering step involves the interaction between P-selectin glycoprotein Jigand1 on effector cells and P-selectin on va scular endothelial cells (Pachter et al., 2003; Pedemonte et al., 2006; Prendergast and Anderton, 2009). This low-affinity contact resuJts in the effector cells rolling a long the endothelial cell surface (Fig. 10.3) (Engelhardt, 2006; Prendergast and Anderton, 2009).

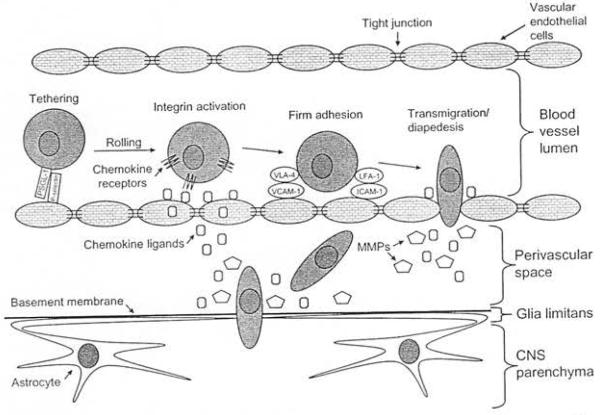

Fig. 10.3.

Steps and factors involved in the movement of effector cells of the adaptive immune response from the periphery, across the blood-brain barrier, and into the parenchyma of the cenlral nervous system (CNS). Effector ce11s undergo tethe ring as a result of interactions between P-selectin glycoprotc in ligandI (PSGL-1) on effector cells and P-selectin on vascular endothelial cells which in tum causes the effector cells to rol l. Chemokine receptors on the romng effector ce lls bind to chemok ine ligands on the vascular endothelial cells , wh ich results in integrin ac ti vat ion on the su rface of effector cells. Leukocyte function-associated antigen-I (LFA-1 )/intercel lular adhesion molecule-I (lCAM-1) interactions and very late antigen-4 (VLA-4)/vascular cell adhesi on molecule-I (VCAM-1) interactions serve to firmly adhere act ivated T cells to the vascular endothelial cells. The cells now arrest, fhuten, and transrn igrate/diapedes across the endotheliu m and into the perivascular space. Chemokincs and mat rix metalloproteinases (MMPs) fu nct ion to help the effector cells to cross the basement membrane of the glia limitans, thus gaining entry to the CNS parenchyma.

The next step involves cbemokines (chemotactic cytokines) (Pachter et al., 2003; Engelhardt, 2006; Pedemonte et al., 2006; Prendergast and Anderton, 2009). The chemokine system includes both ligands, of which there are a large number classified as C, CC, CXC, or CX3C chemokines, and receptors, which number fewer and are promiscuous G-protein-coupled receptors (Cardona et al., 2008; Miller et al., 2008; Ransohoff, 2009). Chemokjne receptors on the rolling effector cells bind to chemokine ligands on the vascu lar endothelial cells (Fig. 10.3) (Pachter et al., 2003; Engelhardt, 2006; Pedemonte et al., 2006; Prendergast and Anderton, 2009). The chemokine ligands can either be directly produced by the vascular endothelial cells or the vascular endothelial cells may translocate extracellular chemokine ligands released by neighboring cells, such as astrocytes (Mrass and Wen inger, 2006). Regardless of the source of the chemokine ligands, this interaction between chemokine ligands and receptors results in the activation of integrins on the surface of effector cells (Engelhardt, 2006; Pedemonte et al., 2006; Prendergast and Anderton, 2009).

The activation of integrins results in a conformational change from a low-affinity to a high-affinity state, thus facilitating the interaction of these integrins with adhesion molecules, which is the next step in the movement of effector cells into the CNS parenchyma (Pachter et al., 2003; Engelhardt, 2006; Pedemonte et al., 2006; Prendergast and Anderton, 2009). Very late antigen-4 (VLA-4) and leukocyte function-associated antigen-I (LFA-1) are integrin molecules expressed by activated T cells that are required for migration of T cells across the BBB (Carson et al., 2006). Vascular cell adhesion molecule-I (VCAM-1) and intercellular adhesion molecule-l (ICAM-1) are expressed on vascular endothelial cells and are required for migration of T cells across the BBB (Carson et al., 2006). LFA-1/ICAM-l interactions, under physiologic and inflammatory conditions, and VLA-4NCAM-l interactions, under inflammatory conditions, serve to firmly adhere activated T cells to the vascular endothelial cells (Fig. 10.3) (Pachter et al., 2003; Pedemonte et al., · 2006; Prendergast and Anderton, 2009). M igration of B cells across the BBB requires interactions between LFA-l/ICAM-1 and VLA-4/fibronectin (Alter et al., 2003). The cells now arrest, flatten, and migrate across the endothelium (Fig. 10.3) (Pedemonte et al, 2006; Prendergast and Anderton, 2009). Chemokines are thought to play an important role again at this point as the effector cells find and transmigrate through the tight junctions of the endothelium and enter the perivascular space (Prendergast and Anderton, 2009). In contrast to this paracellular migration through the tight junctions, effector cells may also cross through the cytoplasm of the endothelial cells, termed transcellular migration (Engelhardt, 2006).

The one remaining barrier to the entry of effector cells into the CNS parenchyma is the basement membrane, of the glia limitans, composed of extracellular matrix proteins (Prendergast and Anderton, 2009). Both chemokines and MMPs are required at this stage to allow access to the CNS parencbyma (Fig. 10.3) (Prendergast and Anderton, 2009). MMPs function as endopeptidases that degrade the extracellular mat rix proteins (Bailey et al., 2006) and are expressed by both normal human T and B cells (Alter et al., 2003).

Multiple factors affect the integrity of the BBB and the ext ent to which the BBB is pert urbed by these factors can depend on the type, site, and stage of infection (Savarin and Bergmann 2008). In addition to MMPs, such as MMP-9, produced in large part by neutrophils of the innate immune response, other factors also facilitate T-ccll entry by contributing to the loss of BBB integrity (Zhou et al., 2003; Savarin and Bergmann, 2008). IL-17 has been suggested to play a role in increasing the penneability of the BBB, therefore CD4 + Th17 cells may help effector cells of the adaptive immune response get from the periphery into the CNS (Kang and McGavem, 2009). Inflammatory cytokines such as I L-17 and IL-6 are known to increase BBB permeability, possibly by affecting the integrity of the tight junctions (Prendergast and Anderton, 2009). In addition, as described below for West Nile virus infection, TNF-<X increases the permeability of the BBB (Wang et al., 2004; Nathanson and Murphy, 2007; Savarin and Bergmann, 2008; Prendergast and Anderton, 2009). The mechanism of action of the secreted TNF-a may be through the induction of apoptosis in vascular endothelial cells (Wang et al., 2004; Bailey et al., 2006). Viruses may also be able to directly infect and lysc vascular endothelial cells, thus increasing the permeability of the BBB (Bailey et al., 2006).

During acute viral infection in the CNS, numerous chemokines, expressed by CNS-resident cells, function to recruit virus-specific adaptive effector cells (Savarin and Bergmann, 2008). CNS-resident cells, primarily astrocytes, produce multiple chemokine ligands which interact with their cognate chemokine receptors expressed by activated CD4 + and/or CD8 + T cells or B cells (Alter et al., 2003; Columba-Cabezas et al., 2003; Chavarria and Alcocer-Varela, 2004; Lane et al., 2006; Savarin and Bergmann, 2008). For example, the chemokine receptor CXCR3, which interacts with the CXCLIO chemokine ligand, is expressed by both CD4 + and CD8 + T cells (Lane et al . , 2006; Savarin and Bergmann, 2008). Alternatively, although not extensively examined in viral infection, the chemokinc receptor CCR7, expressed by B cells, interacts with the CCL21 and CCL19 chemokine ligands, expressed by BBB endothelium, microglia, and astrocytes, under conditions of chronic neuroinflammation in an animal model (Columba-Cabezas et al., 2003; Chavarria and AlcocerVarela, 2004), whereas the chemokine receptors CCR2, CXCR l, and CXCR2 are expressed on normal human B cells and play a role in immune surveillance of the non-inflamed CNS (Alter et al., 2003).

Once in the CNS

Immune cells that gain entry to the parenchyma of the CNS are then subject to regulat ion by resident CNS cells. Interstitial movement of the virus-specific adaptive effector cells through the parenchyma, to reach their target, most likely follows chemotactic gradients establlShed by resident CNS cells (astrocytcs, microglia) (Mrass and Weninger, 2006). The interaction of Fas ligand (FasL), expressed on multiple cell types within the CNS (astrocytes, microglia, oligodendrocytes, vascular endothelial cells), and Fas, expressed on the immune cells, may induce the immune cells to undergo apoptosis (Bailey et al , 2006; Galea et al., 2007; Kaplan and Niederkorn, 2007). Microglia also express the molecule B7 homolog I which downregulates the activation of T cells through an inhibitory interaction as opposed to costimulatory interaction (Magnus et al., 2005; Pedemonte et al., 2006; Galea et al., 2007). Cell-cell conflict between neurons and T cells during CNS inflammation can result in the conversion of act ivated CD4+ cells to Tregs that suppress CNS inflammation (Liu et al., 2006). An immunosuppressive environment genby resident CNS cells within the CNS contributes immune privilege of the CNS and to protection from damage due to infection, the immune response to infection and inflammation.

The retention and antiviral function of CNS-T cells depend on the MHC-restricted presentation of viral antigen by infected cells (Pachter et al., 2003; Galea et al., 2007; Savarin and Bergmann 2008;, Within the CNS the level of expression of MHC is low (Joly et al., 1991; Kimura and Griffin 2000, Zhou et al., 2003; Bailey et al., 2006; Galea al., 2007). During most vira1 infections of the CNS, class II molecules are not detectable on astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, or neurons, but are inducible on ylicroglial cells (Savarin and Bergmann, 2008). ThereCD4+ T cells function mainly in a helper capacity within the CNS, as opposed to having any direct antiviral (Savarin and Bergmann, 2008). Cells of the CNS that can upregulate the expression of MHC class I and .are therefore potential infected targets for CD8 + CTLs include astrocytes, neurons (Kang and McGavern, 2009), and microglial cells (Steel et al., 2009). Therefore, CD8+ CTLs function as the primary mediators of the adaptive immune response in reducing viral replication within the CNS (Savarin and Bergmann, 2008). The mechanisms used by the CD8 + CTLs to control viral replication differ by the cell type infected: perforin-dependent cytolysis is used for infected microglia and astrocytes, Fas/FasL-induced apoptosis is used for tnfected neurons, whereas IFN-y is used for infected ol igodendrocytes (Parra et al., 1999; Medana et al., 2000; Lane et al ., 2006). However, viral clea rance from neurons may be dom inated by non-cytolytic mechanisms mediated by antibody and cytokines, especially IFN-y (Tishon et al., 1993; Patterson et al., 2002; Binder and Griffin, 2003; Griffin, 2003; Burdeinick-Kerr and Griffin, 2005). Whether or not these resident CNS cells become infected in the first place depends on the tropism of the virus.

Plasma cell production of virus-specific antibodies is independent of both MH C-restricted presentat ion of viral antigen by infected cells (Savarin and Bergmann, 2008) and T-cell regulat ion (Tschen et al., 2006). Plasma cells present in the CNS typically secrete the lgG and lgA classes of antibodies (Griffm, 2003). The physica l presence of plasma cells within the parenchyma of the CNS is not required for antibodies to reach their targets (Galea et al., 2007). Intrathecal antibodies, produced by plasma cells present in the CSF, can di ffuse into the parenchyma (Galea et al., 2007). Evidence of intrathecal antibody synthesis includes the occurrence of oligoclonal antibody bands, with measles virus-restricted specificities, in the CSF of patients with subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE) following measles virus infection (discussed further below) and the detection of an increased CSF to serum antibody ratio following experimental viral encephalitis (Tschen et al., 2006). In an experimental model of acute viral encepbalomyelitis followed by viral persistence, it was found that virus-specific plasma cells within the CSF peaked at I week after control of the infectious virus and were maintained throughout the chronic infection. Therefore, plasma cells appeared to be recruited to, and preferentially retained with in, the CSF during and after control of acute viral infections of the CNS.

The recruitment and retention of virus-specific plasma cells within the CSF were proposed to depend on the chemokine ligands CXCL9 and CXCL10, the chemokine receptor CXCR3 and BAF, the B-cell activation factor from the 1NF family which is a B-cell survival factor (Waldschmidt and Noelle, 2001; Defrance et al., 2002; Melchers, 2003). So, although virus-specific antibody may not contribute to the control of the virus during acute infection of the CNS, virus-specific antibody produced locally in the CSF is required for control of viral persistence within the CNS. In addition to the CSF, other regions to which plasma cells may be recru ited and maintained during viral infection of the CNS include the meninges, perivascular areas, and the brain parenchyma itself (Tschen et al., 2006).

VIRAL CLEARANCE VERSUS VIRAL PERSISTENCE

Viral infections within the CNS, and the virus-induced immune response to such in fections, commonly result in viral encephalitis and men ingoencepha litis (Binder and Griffin, 2003). Damage can occur to the infected areas of the CNS and the function of the CNS can be affected . The entire process can lead to symptoms such as headache, altered cognatmn, paralysis, coma, and death. Factors that affect the ability to clear virus from the CNS include the genetic background and age of the host, the strain of the virus, and the type of cell infected. One mechanism for viral clearance within the CNS is non-cytolytic and is mediated by a combination of virus-specific T cells, both CD4 + and CD8 + T cells, and antibodies, all effectors of the adaptive immune response (Binder and Griffin, 2003). Varus-specific T cells, both CD4+ and CD8 + T cells, play the primary role in viral clearance of non-cytopathic viruses, with support from antibodies, whereas virus-specific antibodies play the primary role in viral clearance of cytopathic viruses, with support from T cells (Kagi and Hengartner, 1996; Zinkernagel et al., 1996; Ramakrishna et al., 2003). As cells of the CNS are not easily replaced, non-cytolytic clearance mechanisms reduce the overall damage to the infected areas of the CNS (Tishon et al., 1993; Patterson et al., 2002; Griffin, 2003; Burdeinick-Kerr and Griffin, 2005).

However, non-cytolytic clearance mechanisms may not provide complete clearance of the virus, thus allowing virus to persist (Griffin, 2003). Also, many viruses are known to employ various strategies to evade imune detection and clearance and establish viral persistence. Mechanisms by which viruses persist include imune tolerance, where virus-specific hnmunity is lacking and viruses can persist at high titers, and latency, where viral genome persists but infectious virus is not produced (Nathanson and Gonzalez-Scarano, 2007). In an experimental persistent viral infection, functional inactivation of virus-specific CD4+ and CD8 + T cells, shown as an inability to produce IFN-y, TNF-a, and IL-2 in response to viral antigens, was caused by increased production of IL-10 by APCs (myeloid and lymphoid DCs, but not plasmacytoid DCs) (Brooks et al., 2006, 2008b). In addition to and separate from IL-10, increased production of programmed death (PD)-l, on virus-specific CD8 + T cells, and its ligand (PD-LI), on APCs, also resulted in functional inactivation of virus-specific T cells and viral persistence (Brooks et al., 2008a). In addition, viruses with high mutation rates (RNA viruses) may be able to overcome immune control of viral infection and persist through ant igenic variation (Davenport et al., 2007). Finally, many of the unique fcatures of the CNS that contribute to the in1mune privilege of the CNS, low MHC expression, for example, also contribute to the establishment of viral persistence, in this case where minimal levels of infectious virus may be continuously produced (Ramakrishna et al., 2003; Nathanson and Gonzalez-Scarano, 2007).

Viruses that can infect the CNS include both DNA and RNA viruses (Binder and Griffin, 2003; Griffin, 2003). DNA viruses can replicate within the host cell nucleus, either episomally or integrated into the host DNA, and thereby demonstrate tru e latency in which no infectious virus is detectable (Binder and Griffin, 2003; Griffin, 2003). Both DNA and RNA viruses can persis within the CNS with long-term production of detectable infectious virus or viral DNA or RNA (Binder and Griffin, 2003). The most critical mechanisms for controlling viral persistence within the CNS, and preventing reactivation of latent virus or viral recrudescence, may be the local production of neu tralizing antibodies, which in general target surface glycoproteins and external capsid proteins exposed on the virion surface, followed and supported by antibodies that inhibit cell-cell fusion and thereby limit viral spread (Ramakrishna et al., 2003). This antibody-mediated control of viral persistence is independent of both ADCC and complement (Ramakrishna et al., 2002, 2003). Viral persistence may be maintained in the CNS through viral infection of certain cell types, which serve as a viral reservoir, from which the neutralizing/fusion-inhibiting antibodies are unable to clear the virus (Ramakrishna et al., 2003). It is particularly difficult to eliminate a virus completely from the CNS once the virus has established a persistent infection there and the virus may persist in the CNS long after sterilizing immunity has been achieved in the periphery (Lauterbach et al., 2007). Persistent viral infections may be asymptomatic or more often are associated with chronic progressive illness (de la Torre et al., 1996; Nathanson and Gonzalez-Scarano, 2007). One mechanism that may be employed by the host to eliminate persistently infecting viruses completely from the CNS is the diversification of the adaptive immune repertoire (Lauterbach et al., 2007).

ADAPTIVE IMMUNE RESPONSE TO SPECIFIC NEUROTROPIC VIRUSES

Viruses that infect the CNS include those that cause an acute disease followed either by clearance of the virus or death of the host (West Nile virus, Venezuelan, Western and Eastern equine encephalitis viruses, rabies virus, in flucnza virus, lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus poliovirus), those that pcrsisl within the CNS (measles virus, mumps virus, rubella virus) and those that remain latent, either outside of or within the CNS and can reactivate and cause CNS disease (retro-viruses herpesviruses, JC virus). Each of these viruses will be discussed individually below together with the adaptive immune response to each of these viruses which in turn plays a ro1e in determining the outcome of viral infection (death, clearance, persistence, latency). West Nile virus, of the family Flaviviridae which will be discussed in detail in Chapter 20, is an enveloped, single-stranded, posit ive-sense RNA virus (Glass et al., 2005; Diamond et al. , 2009). West Nile virus is a cytopathic virus that is transmitted by mosquitobite (arthropod injection) (Nathanson and Ahmed, 2007; Klein and Diamond, 2008; Diamond et al. 2009). Transient virem ia is followed by entry of the virus into the CNS, between days 4 and 5, where neurons are infected and acute encephalitis results (Nathanson and Ahmed, 2007; Mehlbop and Diamond, 2008; Diamond et al., 2009). Rare fatalities occur in the elderly and immunocomprom ised as a consequence of encephalitis (Wang and Fikrig, 2004; Klein and Diamond, 2008). Entry of West Nile vi rus into the CNS fol1owing peripheral infection appears involve activation of Toll-Hke receptor 3, a component of the innate immune system that recognizes double-stranded RNA, leading to an increase in circulating TNF-α which in turn increases the permeability of the BBB and, thus, virus entry (Wang et al., 2004; and Murphy, 2007; Savarin and Bergmann, 2008). Antibodies have been shown to play an important role in resolving the viremia, and therefore limiting the dissemination of virus into the CNS, whereas C8+ are critical for viral clearance from infected tissues (Wang and Fikrig, 2004; Nathanson and Ahmed, 2007; Klein and Diamond, 2008). Early generation of virus-specific neutralizing antibody of the IgM class is crucial for control of West Nile virus infection and limit ing entry of West Nile virus into the CNS (Mehlhop and Diamond, 2008). CDS + T cells contribute to clearance of West Nile virus from neurons in the CNS (Wang and Fikrig, 2004; Shrestha et al., 2006; Klein and Diamond, 2008), and, at least in the case of a highly virulent lineage I New York West Nile virus strain, this clearance is through a perforin-dependent ant igen-M HC class I-restricted mechanism (Shrestha et al. , 2006). CD4 + T cells provide support for bot h antibody responses and virusspecific CD8 + T-cell responses during West Nile virus infection (Diamond et al., 2009). yo T cells, and their product ion of JFN-y early during in fect ion, have also been shown to be crit ical for viral control and host survival following West Nile virus infect ion (Wang et al., 2003; Wang and Fikrig, 2004; Klein and Diamond , 2008). Recru itment of West Nile virus-specific effector T cells to the CNS, and s u bsequen t viral clearance of the CNS, has been shown to be dependent on interact ions between CXCL 10-CXCR3 and CCL5-CCR5 and on the expression of CXCUO by i n fected neurons (Glass et al., 2005; Klein et al. 2005; Klein and Diamond , 2008; Savarin and Bergman n, 2008). In this case, both effectors of the adaptive immune response, antibodies and CD8+ CTLs, play a role in viral cleara nce and protection from West Nile virus infection (Nathanson and Ahmed, 2007; Klein and Diamond, 2008). Most importantly, virus-specific CD8 + CTLs in the CNS do not induce, and may diminish, immunopathology in the context of cytopathic West Nile virus infection of the CNS (Klein and Diamond, 2008) .

Venezuelan, Western, and Eastern equine encephalitis viruses

Venezuelan, Western, and Eastern equine encephalitis viruses (Chapter 19) are alphaviruses, of the family Togaviridae, and arc enveloped, non-segmented, single-stranded positive-sense RNA viruses (Paessler et al., 2006; Griffin, 2007). Alphavimses are naturally transmitted by mosquito bite (Griffin, 2007). However, Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus is also highly infectious via the aerosol route (Zacks and Faessler, 2010). The method of entry of alphaviruses into the CNS remains unclear (Griffin, 2007). Once in the CNS, alphaviruses infect neurons (Ramakrishna et al.; 2002). Neurologic symptoms in humans and equines may range from a mild febrile illness to severe encephalitis resulting in death (Zacks and Paessler, 2010). The development of severe encephalitis appears to be dependent on neuronal cell death due to both the replication of virus to high t iters within the brain and the host's neuroinflammatory response to the virus (Paessler et al., 2006, 2007). Studies with murine models of Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus infection have shown that, although antibodies are protective against lethal meningoencephalitis when the virus is transmitted via the periphery (insect bite), in contrast, virus-specific CD4 + T cells, but not CD8 + nor yo T cells, are important for protection from lethal mcningoencepbalitis when the virus is transmitted intranasally (aerosol route) (Paessler et al., 2007; Yun et al., 2009).

Rabies virus

Rabies virus, of the family Rhabdoviridae, discussed in Chapter 29, is an enveloped negative-strand RNA virus (Binder and Griffin, 2003). Rabies virus is highly neurotropic. Antibody-producing B cells are critical for control of virus replication and are used in prophylaxis after rabies virus exposure (Binder and Griffin, 2003). Viral spread to and within the CNS is controlled by means of serum-neutralizing ant ibodies and antibodies function to control replication of the virus within neurons tluough mechanisms other than neutralization of virus infectivity and with help from T cells and certain cytokines (Hooper et al., 2002; Binder and Griffin, 2003). When prompt administration of prophylactic neutralizing antibodies does not occur, a lethal neurologic disease develops, ind icating that the immune response to natural rabies virus infection is ineffective in preventing disease (Roy et al., 2007). The critical factor leading to this ineffective immune response was determined, experimentally for a rabies virus strain associated with silver-haired bats, to be a deficit in adaptive imm u ne effector cell accumulation within the CNS due to a virally-induced reduction in BBB permeability (Roy et al., 2007).

Influenza virus

Influenza virus, of the family Orthomyxoviridae, which will be discussed in detail in Chapter 30, is an enveloped segmented single-stranded negative-sense RNA virus (Palese and Shaw, 2007). Influenza virus is a common respiratory virus (Stevenson et al., 1997). Certain strains of influenza virus (HINI) are neurovirulent, can infect ependymal cells and neurons within the brain parenchyma, and can cause encephalitis which leads to death within 6-8 days (Hawke et al., 1998). Experimenta lly, death can be avoided and recovery from viral encephalitis can occur in animals subjected to earlier imunization with intranasal influenza (H3N2). This immunization results in the generation of virus-specific CD8 + memory CTLs that are able to protect against the neurovirulent H INI influenza virus. In addition, activated virus-specific CDS + CTU can be found within the brain parenchyma long after HINI influenza virus has been cleared following viral encephalitis in H3N2-immunized animals. This local persistence of activated CD8 + CTLs m ay be an efficient mechanism to prevent viral recrudescence within the brain parenchyma (Hawke et al., 1998).

Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus

Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus, of the family Arenaviridae, discussed in Chapter 33, is an enveloped RNA virus, consist ing of two single-stranded RNA segments that have a bidirectional coding strategy (ambisense) (Romanowski and Bishop, 1985; Romanowski et al., 1985). This virus is a non-cytopathic virus that in fects, but does not kill, a variety of cell types within the meninges, cpendyma, and choroid plexus of the CNS (Oldstone et al., 1982; Parra et al., 1999; McGavern et al., 2002; Binder and Griffin, 2003; Kang and McGavern, 2008, 2009). Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus-specific CDS + effector T cells, expressing CCR2, CCR5, and CXCR3, are recruited to the infected CNS and infiltrate into the CNS parenchyma through the actions of CCL2, CCLS, CXCL9, CXCL IO, and CXCLI 1 (Thomsen, 2009). However, instead of funct ioning in viral clearance and protection from disease, lymphocyt ic choriomeningitis virus-specific CDS + CTLs of the adapt ive immune response are requ ired for t11e development of pathology: vi rus-induced acute meningitis that results in fatal convulsive seizures (McGavern et al., 2002; Kang and McGavern, 2008, 2009). The virus-specific CD8 + CTLs lyt ically attack virus-in fected cells of the CNS, through the use of perforin (Kägi et al., 1995), and, more importantly, secrete chemokines that attract monocytes and neutrophils (innate immune effector cells) to the infected meninges which, in turn, cause BBB breakdown and the development of fatal seizures (McGavern et al., 2002 Kang and McGavern, 2009). Death occurs within 6-S days (McGavem et al., 2002; Kang and McGavem1 2008).

Under conditions of immunosuppression, this virus can establish a persistent infection with involvement of neurons (fishon et al., 1993; Binder and Griffin, 2003; Kang and McGavem, 2008). Regulation of this persistent infection depends on antibodies, CD4+ T cells, and cytokines (Ramakrishna et al., 2002). AdditionaJly, congenital infection with lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus resu lts in T-cell anergy to the virus and the development of a persistent infection with involvement of most of the host's organs (Jamieson et al., 1991). This congenitally acquired chronic infection can be cured through the adoptive transfer of virus-specific CD8+ T cells. It was shown that the adoptively . transferred virus-specific CD8 + T cells eliminated vrs from the thymus, thus allowing for the restoration of the host T-cell repertoire and protection against viral spread and reinfection (Jamieson et al., 1991). Through the use of an experimental model of chronic lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus infection, virus-specific CDS + T cells from chronically infected animals were shown to be dysfunctional, in comparison to virus-specific effector and memory CD8+ T cells, due to T-cell exhaustion, which was distinct from T-cell anergy (Wherry et al., 2007). The exhausted CD8 + T cells overexpressed cell surface in11ibitory receptors, downregulated TCR and cytokine signaling, had changes affecting chemotaxis, migration, adhesion and transcription factors, and had metabolic and bioenergetic deficiencies. Therefore, CDS + T-cell exhaustion resulted from both active suppression and passive defects in signaling and metabol ism (Wherry et al., 2007).

Poliovirus

Poliovirus, of the family Picornaviridae, is a non-enveloped single-stranded positive-sense RNA virus . (Racaniello, 2007). Poliovirus is an cnterovirtls (Chapter 18) spread from person to person by the oral route (Nathanson, 2008; Griffin, 2010). In rare instances, poliovirns spreads to the CNS .and infects motor neurons, thus causing acute flaccid paralysis (Nathanson, 2008; Griffin, 2010). Approximately 10% of these paralytic cases result in death (Roush and Murphy, 2007). Poliovirus can spread to the CNS via either the blood or through the neural route, with the stra.m of virus dictating the dominant route of spread the host (Nathanson, 2008). Following poliovirus infection or vaccination, neutralizing antibodies arise which play a role in viral clearance, can be detected (or years, and may provide lifelong protection 2008). Vaccination with the inactivated vaccine (injected, referred to as IPV) prevents viral spread to the CNS, through induction of antiviral serufo antibodies, but may allow viral infection of the intestinal tract, whereas vaccination with the live attenuated vaccine (oral poliovirus vaccine, referred to as OPV) protects against wild-type viral infection of the intestinal tract, through induction of mucosal immunity weJl as antiviral serum antibodies, and thus prevents person-to-person spread of the virus (Nathanson, 2008; Griffin, 2010). However, poliovirus remains an irnportarit cause of neurologic disease as the three live attenuated, vaccine strains of poliovirus can recombine their geonmes and revert to virulence (Griffin, 2010). In addipoliovirus is currently endemic in four countries, Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, and Nigeria, and in two these countries, Afghanistan and Pakistan, political and conflict remain as the most significant barrier to achieving poliovirus eradication via vaccina-(Mohamed et al., 2009). Although poliovirus is usually cleared by the adaptive immune response, under conditions of antibody deficiency in humans this virus capable of establishing a persistent infection, as demonstrated by continued fecal shedding of virus (Martín, 2006; Nathanson, 2008).

Measles virus

Measles virus (Chapter 27) is a Morbillivirus, of the family Paramyxoviridae, and is an enveloped singlestranded negat ive-sense RNA virus (Nathanson and Gonzalez-Scarano, 2007). Measles virus is spread by the respiratory route (Nathanson and Gonzalez-Scarano, 2007). One neurologic complication of measles virus infection, thought to be related to dysregu lation of the cellular immune responses, as it can occur in the absence of viral replication in the CNS, is post infect ious encephalomyelitis, which develops wit hin weeks of infection (Johnson et al., 1983 1984; Hirsch et al., 1984; Johnson, 1987). However, measles virus can infect and persist in neurons (Parra et al ., 1999; Ramakrishna et al., 2002). In immunocompetent individuals a CD4 + T-cell popu la tion mediates elimination of measles virus from neurons, possibly through secretion of IFN-γ (Parra et al., 1999; Schneider-Schaulies et al., 2003). Failure of the inunune response to eliminate measles virus-infected cells completely from the CNS can result in viral persistence (Schneider-Schaulies et al., 1999).

Measles virus is capable of persisting in neurons as a defective variant that spreads from neuron to neuron directly, without passage through the extracellular enviromnent (Schneider-Schaulies et al., 1999, 2003; Lawrence et al., 2000; Nathanson and Gonzalez-Scarano, 2007). In this way the virus avoids detection and elim ination by circu lating high titers of measles virus-specific neutralizing antibody. The persistence of measles virus in the CNS can result in a progressive fatal encephalitis called SSPE developing in immunocompetent individuals several months to years after infection and recovery from acute measles virus infection (Schneider-Schaulies et al., 1999, 2003; Nathanson and Gonzalez-Scarano, 2007). As such, SSPE is primarily a disease of childhood and young adulthood (Gilden, 1983; Wolinsky, 1990).

As described above, oligoclonal IgG antibody bands, with measles virus-restricted specificities, are characteristically found in the serum and CSF of patients with SSPE (Mehta et al., 1994; Burgoon et al., 2006; Tschen et al., 2006). These oligoclonal bands are a hyperimune response to measles virus antigens, which, despite their neutralizing activity, are unable to control the viral infection (Mehta et al., 1994). This inability of measles virusspecific antibodies to control measles virus infection in SSPE patients may result from antibody-induced antigenic modulation by the virus (Fujinami and Oldstone, 1980, 1983; Fujinami et al., 1984). The expression of some measles virus antigens within and on the surface of measles virus-infected cells is altered upon binding of measles virus-specific antibodies such that the synthesis, assembly, and maturation of the virions are altered. In this way the measles virus-infected cells may avoid detection and Iysis and measles virus may persist. Thus, in the case of measles virus, the antibody arm of the adaptive immune response to the virus may play a role in the initiat ion of viral persistence (Fujinami and Oldstone, 1980, 1983; Fujinami et al., 1984).

Rubella virus

Rubella virus (Chapter 28), of the family Togaviridae, is an enveloped single-stranded positive-sense RNA virus (Frey, 1997; Nath, 2003). Rubella virus is spread by the respiratory route. Primary infect ion most often causes a benign illness, but rarely neurologic involvement occurs (Nath, 2003). Progressive rubella panencephalitis (PRP) is, like SSPE, a fa tal disease of childhood that can deve1op long after both typical childhood rubella and congenital rubella syndrome (CRS) as a result of rubella virus persistence (Berg, 1977; Townsend et al., 1982; Wolinsky, 1990). CRS refers to any combination of defects known to resu lt from rubella virus infection during gestation and panencephalitis is one of several lateonset manifestations of CRS (Webster, 1998). Demyelination is a characteristic of PRP and may be mediated by the antibody arm of the adaptive immune response as oligoclonal IgG antibody bands, with specificities restricted to the structural proteins of rubella virus, are a characteristic of PRP and there has been shown to be molecular mimicry between the structural proteins of rubella virus and the proteolipid protein of myelin (Townsend et al., 1982; Wolinsky et al., 1982; Wolinsky, 1990). However, unlike SSPE, the presence of rubella virus within the brain has not been defmitively demonstrated (Townsend et al., 1982; Frey, 1997). Therefore, rubella virus may persist outside of the CNS, causing an adaptive inunune response to the virus which in turn causes immunopathology within the CNS, ultimately resulting in PRP (Frey, 1997).

Mumps virus

Mumps virus (Chapter 28), also of the family Paramyxoviridae, is an enveloped single-stranded negative-sense RNA virus (Rubin and Carbone, 2003; Hviid et al., 2008). Mumps virus is spread by the respiratory route. Primary infection with mumps virus causes an illness more benign than measles; however aseptic meningitis and encephalitis are common complications. Although CNS infection with mumps virus is common, deaths and long-term morbidity are rare (Hviid et al., 2008). Virusspecific ant ibodies have been shown to play an important role in restricting both viremia and salivary secretion of the mumps virus (Overman, 1958; Chiba et al., 1973). Mumps viral infection of choroidal and ependymal epithelial cells allows for viral spread throughout the brain parenchyma (Wolinsky et al., 1976). In rare instances, mumps virus is thought to persist in the CNS either following recovery from acute mumps virus encephalitis or during the course of chronic progressive mumps virus encephalitis as mumps virus-specific antibodies have been found to persist in the CSF in both cases (Julkunen et al., 1985; Haginoya et al. 1995).

Retroviruses

Human immunodeficiency virus type I (HIV-I) (Chapter 23) and human T-lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV1) (Chapter 24) are of the family Retroviridae and are enveloped single-stranded RNA viruses (Goff, 2007). Retroviruses are transmitted through sexual contact and contam inated blood products and from mother to infant (Grant et al., 2002). Retroviruses replicate by reverse transcribing the viral RNA genome into a double-stranded DNA form that integrates into the host chromosomal DNA (Satou and Matsuoka, 2010). Both of these retroviruses main ly infect CD4 + T cells, causing dysregu lation of the host adaptive immune response (Satou and Matsuoka, 2010).

HIV-1

Entry of HTV-1 into the CNS occurs early after init ial infection and is through trafficking of HIVI-in fected monocytes/macrophages (Ellis, 2010). The characteristic neurocognitive disorder during this acute infection is a meningoencephalitis that is self-limiting through the actions of the innate and adaptive immune responses, resulting in the clearance of HIVI-infected macrophages/microglia by HIV-1-specific CTLs (Poluektova et al., 2004). This acute meningitis occurs at the time of seroconversion in relat ively immunocompctent individuals (Hollander and Stringari, 1987). CSF pleocytosis accompanies this early ncurocognitive disorder (McArthur et al., 1989) or may be present in asymptomatic HIV-1-infected individuals (Spudich et al., 2005; Marra et al., 2007). Pleocytosis, a marker of CNS inflammation, is defined as the appearance of leukocytes in the CSF to a level exceeding 5 cells/mm3 (Smith et al., 2009) and has been found to be highly correlated to CSF HI V-1 infection (Spudich et al., 2005; Marra et al., 2007). Within the CNS HIV-1 infection is maintained by infection of macropbages/microglia and neurons are damaged through indirect mechanisms which result in damage to synapses and dendrites without major neuronal loss (Ellis, 2010). HIV-1 is a lentivirus and lenthwses encode proteins that can su ppress the expression of MHC class I molecules, thereby allowing virus-infected cells to avoid detection by virus-specific CD8 + CTLs and allowing the virus to persist for an extended period (Nathanson and Gonzalez-Scarano, 2007). HI V-I may also escape immune surveillance through the presence of HI V-I-specific CTLs deficient in perforin content (Nathanson and Gonzalez-Scarano, 2007). HIV-1 also causes immunosuppression through gradual depletion of CD4 + T cells (Ellis, 2010). Ncurocognitive disorders can also arise a fter prolonged viral persistence and inununosuppression in the form of a subacute and progressive neurodegeneration, called HfV-1-associated dementia (Navia et al., 1986a, b; Poluektova et al., 2004). HIV-I-associated dement ia is an important cause of CNS disease worldwide (Griffin, 2010).

HTLV-1

Despite its presence in CD4 + T cells, HTLV-1 does not cause overt immunosuppression (Asquith and Bangham, 2008). Instead HTLV-1 preferentia lly induces the proliferation of in fected CD4 + T cells (Satou and Matsuoka, 2010). HTLVJ-infected CD4 + T cells can be eliminated by virus-specific CD8+ CTLs; however, these CD8+ CTls can be both infected with HTLV-l and regulated by HTLYl-in fected CD4 + Tregs (Satou and Matsuoka, 2010). A virus-speci fic IgM antibody response is also detectable in a percentage of HTLY-1-infected subjects (Asquith and Bangham, 2008), but 'JTLY-1 can also infect antibody-producing B cells (Grant et al., 2002). Overa ll, the virus-induced proliferation of infected cells is able to overcome the leveJ of the adaptive immune response. The ability of this virus to replicate faster than it can be killed is the mechanism by which HTLV-J can persist indefinitely within the Jnrected host (Asquith and Bangham, 2008). One potential pathologic outcome of persistent HTLV-1 infection without CNS involvement is adult T-cell leukemia (Furukawa et al., 2006; Jeang, 2010). HTLV-1 viral persistence within CD4 + T cells and migration of these infected activated CD4+ effector T cells into the CNS can cause the chronic inflammatory disease HTLV-1-associated myelopathy/tropic spastic paraparesis most likely through the hyperproduction IFN-γ (Kubota et al., 1994; Satou and Matsuoka, 2010). In HAM/TSP patients there is a correlation between the amount of HTLV-1 proviral DNA and the proportion of CD4+ T cells in spinal cord Lesions et al., 1994). In addition to migration of a HTLV-1-infected cells into the CNS, HTLV-1 can enter the CNS via infection of the brain's capillary endothelial cells or via transport of virus across the brain's capillary endothelial cells (transcytosis) (Grant et al., 2002). Cytokine dysregulation, HTLV-1-specific antibodies, HTLV-1-specific CD8+ CTL infiltration of the CNS, and hYPerst imulation of the adaptive immune response PY HTLY-1-in fected APCs are also all thought to play critical roles in the pathogenesis of HAM!TSP (Grant et al., 2002). For example, in HAM/TSP patients the amount of HlLV-1 proviral DNA directly correlated with the frequency of virus-specific IFN-y-producing CD8 + effector T cells and inversely correlated with CD8 + memory T cells, suggesting that continuous virus-stimulated differentiation of memory T cells into effector cells plays a role in pathogenesis (Kubota et al., 2000). HTLV-1 may also infect astrocytes and microglfaJ cells within the CNS (Grant et al., 2002).

Herpesviruses

Herpesviruses, of the family Herpesviridae, discussed in Chapter 11, are enveloped double-stranded DNA viruses (Roizman et al., 2007). Spread of herpesviruses is usually via saliva and, less commonly, via sexual contact (Conrady et al., 2010). In fect ion is usually asymptomatic or simply the development of a cold sore; however in rare instances serious CNS disease can occur (Conrady et aJ., 2010). HSV infects and persists in neurons (Parra et al., 1999; Ramakrishna et al., 2002). HSY includes two serotypes: HSY-I and HSV-2 (Nathanson and Gonzalez-Scarano, 2007). HSV-1 is the primary causative agent of H SY encephalitis (Sheridan and Beck, 2009). Encepha lit is can also be caused by other herpesviruses, to include cytomegalovirus (Chapter 14) (Nathanson and Gonzalez-Scarano, 2007) and variceUa-zoster virus (Chapter 12) (Gilden et al., 1988; Amlie-Lefond et al., 1995; Kleinschmidt-DeMasters et al., 1996). HSY persists through the establishment of latent infection in sensory neurons and neurons located within the CNS (Nathanson and Gonzalez-Scarano, 2007; Baringer, 2008). In humans, latent HSV-1 has been detected in the three cranial nerve ganglia: the trigeminal ganglia, the geniculate ganglia, and the vestibular ganglia (TI1eil et al., 200 1). HSV-1 latency in trigeminal ganglia is accompanied by CD8+ T-cell infiltration of the ganglia (Theil et al., 2003; Hüfner et al., 2006). The CD8+ T cells are cJonally expanded, suggestive of an antigen-driven adaptive immune response, and have features of an activated memory effector phenotype (Derfuss et al., 2007, 2009). Although there is no neuronal destruction, there is a chronic immune response within these immune-privileged ganglia which appears to play a role in maintaining viral latency and has an influence on viral reactivation (Theil et al., 2003). HSV may remain latent for the life of the host and periodic reactivations may or may not occur (Nathanson and Gonzalez-Scarano, 2007). Reactivation of latent HSY within the CNS can result in encepbaUtis which may be fatal or which may be resolved by the host immune responses (Nathanson and Gonzalez-Scarano, 2007). Infiltration of virus-specific CDS + IFN-y + T cells is crucial to the resolution of CNS HSV1 infections (Sheridan and Beck, 2009). During CNS HSV-1 infections, CD8+ T cells are primed and expanded in the draining lymph nodest followed by recruitment and expansion in the spleen, before accumulation in the brain. IFN-y is important for clearing the infection and inhibiting apoptotic neuronal cell death. Although these T cells function to control the viral replication, they are also partially responsible for the neuropathogenesis associated with HSV encephalitis. The onset and extent of encepha litic symptoms correlate with the tim ing of T-cell infiltration into the brain (Sheridan and Beck, 2009).

JC virus

JC virus, of the family Polyomaviridae, discussed in Chapter 17, is a non-enveloped double-stranded circu lar DNA viru (Imperiale and Major, 2007). Primary infection, probably via an oral route, is usua lly asymptomat ic in imm unocompetent individuals (Koralnik, 2002). JC virus persists within the kidneys and lymphoid organs of healthy ind ividuals. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), a slowly progressive demyelinating disease of the CNS and a fatal illness, is caused by reactivation of JC virus in immunosuppressed hosts due to the loss of protective cellular immunosurveiUance (Koralnik, 2002; Nathanson and Gonzalez-Scarano, 2007). Intrathecal synthesis of JC virus-specific IgG antibodies is unable to prevent or control the development of PML. PML develops and progresses as a result of a reduction in the numbers of CD4 + T cells, a reduction in the CD4+ T-cell proliferative response, a reduction in the production of IFN-y by CD4+ T cells, and a reduction in the numbers of JC virus-speci fic CTLs (Koralnik, 2002). PML developed in a couple of patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) who were on the drug natalizumab (Tysabri), a humanized IgG4 monoclonal antibody against the cx4 subunit of the Vl.A-4 integrin, as part of a clinical trial to test this drug in combination with IFN-α for the treatment of relapsing-remitt ing MS (Kleinschmidt-DeMasters and Tyler, 2005; Langer-Gould et al., 2005; Tan and Koralnik, 2010). Sale of natalizumab was suspended from February 2005 through June 2006. Following its reintroduction, 28 confirmed cases of PML, eight of which were fatal, were found out of approximately 65 000 MS patients treated with natalizumab alone, not in combination with other drugs, between July 2006 and November 2009 (Clifford et al., 2010). lmmunosuppression of the T-cell-mediated immune response, but not of the already developed humoral inunune response, by the drug treatments resulted in reactivation of JC virus in the brain, demonstrating that the T-cell-mediated immune response is essential for conta inment of the persistent infection (White et al., 1992; Koralnik:, 2004; Lacey and Zhou, 2007). The use of this and other monoclonal antibodies for the treatment of other autoimmune diseases has also resulted in the development of PML (Tan and Koralnik, 2010). One case of PML occu rred when natalizumab was used in the treatment of Crohn's disease, one case of PML occurred when rituximab, a chimeric IgG1 monoclonal antibody against CD20 + B cells, was used in the treatment of lupus, and three cases of PML occurred when efalizumab, a humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody against the o-subunit of LFA-1, was used in the treatment of psor iasis (Tan and Koralnik, 2010).

CONCLUSION