Abstract

The initial innate immune response to ozone (O3) in the lung is orchestrated by structural cells, such as epithelial cells, and resident immune cells, such as airway macrophages (Macs). We developed an epithelial cell–Mac coculture model to investigate how epithelial cell–derived signals affect Mac response to O3. Macs from the bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) of healthy volunteers were cocultured with the human bronchial epithelial (16HBE) or alveolar (A549) epithelial cell lines. Cocultures, Mac monocultures, and epithelial cell monocultures were exposed to O3 or air, and Mac immunophenotype, phagocytosis, and cytotoxicity were assessed. Quantities of hyaluronic acid (HA) and IL-8 were compared across cultures and in BAL fluid from healthy volunteers exposed to O3 or air for in vivo confirmation. We show that Macs in coculture had increased markers of alternative activation, enhanced cytotoxicity, and reduced phagocytosis compared with Macs in monoculture that differed based on coculture with A549 or 16HBE. Production of HA by epithelial cell monocultures was not affected by O3, but quantities of HA in the in vitro coculture and BAL fluid from volunteers exposed in vivo were increased with O3 exposure, indicating that O3 exposure impairs Mac regulation of HA. Together, we show epithelial cell–Mac coculture models that have many similarities to the in vivo responses to O3, and demonstrate that epithelial cell–derived signals are important determinants of Mac immunophenotype and response to O3.

Keywords: ozone, macrophage, airway epithelial cell, coculture, hyaluronic acid

Clinical Relevance

The results shown here demonstrate that tissue microenvironment along the respiratory tract and interaction with epithelial cells influences macrophage phenotype and response to pollutant exposure. These findings suggest a central role for epithelial cells as orchestrators of immune responses in the lung that can influence immune cell function, and that may serve as future therapeutic targets to modulate respiratory immunity.

Inhalation of ozone (O3) causes immediate nociceptive decreases in lung function and increased airway inflammation that can exacerbate pre-existing diseases, such as asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (1). Despite regulations to reduce ambient O3, in 2008, approximately 36.2% of the U.S. population lived in counties that did not meet the National Ambient Air Quality 8-hour O3 standard (0.075 parts per million [ppm] averaged per 8 h) (2). Although the adverse health effects of O3 are well known, the cellular mechanisms by which O3 alters immune responses in the lung remain unclear.

The induction of airway inflammation after O3 exposure suggests an ongoing innate immune response in the lung. Because O3 is an oxidant gas, the innate immune response to O3 is not likely mediated by recognition through discreet receptors (3). Rather, O3 reacts with components of the airway lining fluid and cellular membrane, such as surfactants and phospholipids, generating reactive intermediates that damage the respiratory epithelium, inducing endogenous danger signals that initiate innate immune responses (1, 4, 5). For example, short fragments of hyaluronic acid (HA), an extracellular matrix glycosaminoglycan produced by airway epithelial cells, have been shown to serve as danger signals in the response to O3 (6, 7). HA fragments induce airway hyper-reactivity and activate inflammatory responses via pattern recognition receptors, such as CD44 (6). Quantities of HA are elevated in the airways of mice and subjects with atopy and asthma after in vivo O3 exposure (6, 8).

Airway macrophages (Macs) and epithelial cells are two of the most abundant cell types in the lower and conducting airways, and thus serve as crucial first responders to O3-induced airway damage (9). The airway epithelium acts as both a physical barrier against the inhaled environment and orchestrator of the innate immune response (10). Acute O3 exposure damages epithelial cells, leading to increased airway permeability, cell death, and the release of cytokines/chemokines and danger signals that can activate local immune cells, such as Macs (1, 11, 12). Airway Macs reside along the airway epithelium and act as key members of the innate immune system by clearing pathogens and debris via phagocytosis, and releasing cytokines and chemokines to regulate the inflammatory response (9, 13). Macs contribute to O3-induced lung injury, as Mac numbers increase after O3 exposure, and blocking Mac activity during O3 exposure in rats reduces airway inflammation (14). However, Macs also play a protective role in the response to O3 by clearing reactive intermediates and cellular debris, and releasing mediators that are antiinflammatory to initiate wound repair (4, 13). These yin-yang characteristics led to the classification of Macs as “classically activated,” proinflammatory, “alternatively activated,” or antiinflammatory/wound healing (13). Studies in rats suggest that inhalation of O3 is associated with accumulation of both classically and alternatively activated Macs in the lung (15).

The close proximity between airway epithelial cells and Macs suggests that they encounter inhaled stimuli simultaneously, and regulate the inflammatory response in tandem. In addition, the lung microenvironment has been shown to influence Mac phenotype and function (16). However, most in vitro studies investigating the cellular inflammatory response to O3 have used monoculture systems, which do not address the interaction between multiple cell types in the airway, and have limited applicability to in vivo situations (11, 12, 17–20). We developed coculture models of primary human airway Macs and human bronchial epithelial (16HBE14o−) or alveolar epithelial (A549) cells to test the hypothesis that signals from epithelial cells modify Mac phenotype and response to O3, and that the these responses differ depending on interaction with alveolar or bronchial epithelial cells.

Materials and Methods

Culture Preparations

16HBE14o− (16HBE) cells, an SV-40 transformed human bronchial epithelial cell line, were a gift from Dr. D. C. Gruenert (University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, CA). 1.5 × 105 16HBE were plated on fibronectin-coated (LHC Basal Medium [Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA], 0.01% BSA [Sigma, St. Louis, MO], 1% Vitrocol [Advanced Bio Matrix, San Diego, CA], and 1% human fibronectin [BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA]) 0.4-μm Transwells (Costar, Corning, NY), and grown submerged in minimal essential media with 10% FBS, 1% penicillin–streptomycin, and 1% l-glutamine (Life Technologies) until confluent for 6 days, and 1 day at air–liquid interface (ALI) before use. A total of 0.75 × 105 A549 cells, an adenocarcinoma cell line with alveolar type II–like characteristics, were plated on 0.4-μm Transwells and grown until confluent, as above, in Dulbecco’s modified Eagles’ medium with 10% FBS, 1% penicillin–streptomycin, and 1% l-glutamine (Life Technologies). Primary human airway Macs were obtained from bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) of healthy volunteers in collaboration with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) using a protocol approved by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Institutional Review Board (Chapel Hill, NC), as described previously (21). A total of 1.5 × 105 BAL cells were added to the apical side of 16HBE and A549 cells or grown alone on Transwells for monoculture controls. At the time of exposure, 5–10% of all cells (∼ 75,000 Macs) in the cocultures were Macs, similar to in vivo estimations (22, 23). Equal volumes of media were added to the apical side of epithelial cell monocultures. Macs were selected by adherence for 2 hours. Apical media containing nonadherent cells were removed and cultures were incubated 18 hours at ALI before exposure (see Figure E1 in the online supplement).

In Vitro O3 Exposure

Cultures at ALI were exposed to filtered air or 0.4 ppm O3 for 4 hours in exposure chambers operated by the U.S. EPA, as previously described (20, 24). The dose was selected for maximal innate immune response to O3 with minimal cytotoxicity, and has been used previously by our group (25). At 1 and 24 hours after exposure, apical sides of all cultures were washed with Hanks’ balanced salt solution (Life Technologies), and cells were collected for flow cytometry analysis or used for phagocytosis assays. See the online supplement for further details.

In Vivo Exposure of Healthy Volunteers to O3

See Table E2 for subject information. Written informed consent was provided by each participant. Healthy volunteers were randomly exposed to air and (in a separate exposure) 0.3 ppm O3 for 2 hours with exercise and a minimum 2-week separation between exposures in collaboration with the U.S. EPA using a protocol approved by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Institutional Review Board, as described previously (26). Bronchoscopy was performed 1 or 24 hours after exposure. Cell-free BAL fluid was stored at −80°C until analysis. See the online supplement for further details.

Statistical Analysis

Data obtained from mono- and cocultures using Macs from the same donor were considered matched pairs. Data shown are mean (± SEM). See figure legends and table footnotes for further statistical information, and the online supplement for additional methods.

Results

Characterization of the 16HBE–Mac Coculture Model

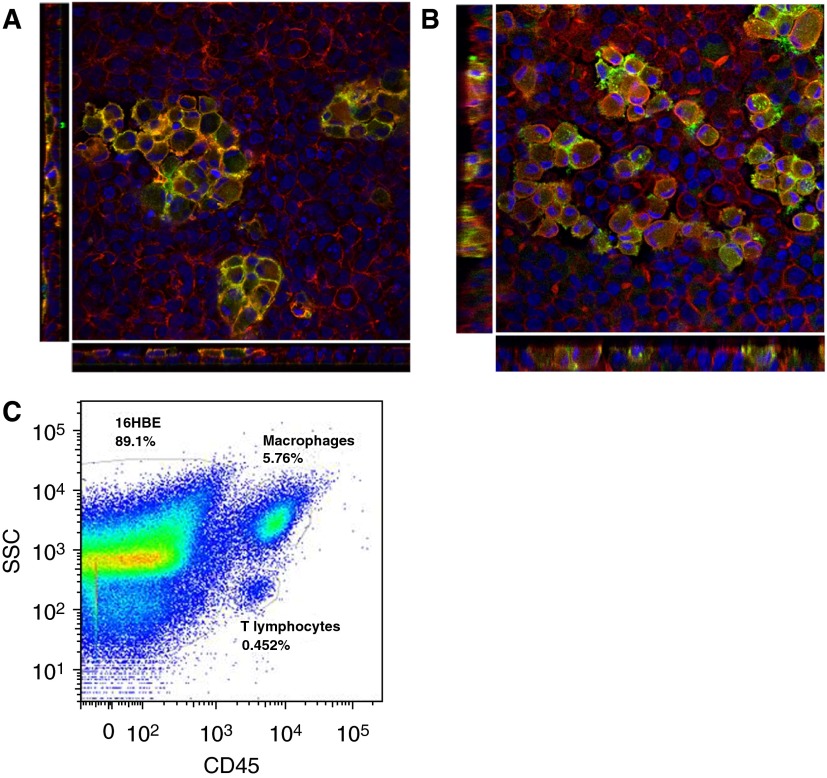

To examine the interaction between Macs and airway epithelial cells, we developed coculture models using primary airway Macs and 16HBE and A549 cell lines. BAL cells from healthy volunteers, which are comprised of over 80% Macs, up to 10% lymphocytes (largely T lymphocytes), and small populations of dendritic cells, neutrophils, basophils, and eosinophils (27, 28), were added to the apical side of the epithelial cells, and Macs were selected by adherence (Figure E1). Immunofluorescence analysis of the coculture indicated that the Macs became semiembedded within the 16HBE and A549 monolayers, suggesting close cell–cell interaction between Macs and epithelial cells (Figures 1A and 1B). Flow cytometric analysis of the cocultures using CD45 and forward scatter/side scatter properties to distinguish Macs from epithelial cells revealed that Macs composed, on average, 6.936% (16HBE cocultures) and 8.183% (A549 cocultures) of all cells in the coculture (Table 1 and Figure 1C). Further analysis revealed a population of CD3+ T lymphocytes in the cocultures (on average, 0.6975% [16HBE cocultures] and 1.032% [A549 cocultures] of all cells [Table 1]), and a very small population (<0.3% of all cells) of CD45+CD3−lineage-1 (Lin1)− human leukocyte antigen-DR (HLA-DR)+ cells that may be dendritic cells (Figure E2). We did not further characterize the T lymphocyte or dendritic cell populations, but, rather, focused our analysis on the effects of coculture with epithelial cells on Mac phenotype and response to O3.

Figure 1.

Characterization of the epithelial cell and airway macrophage (Mac) coculture model. En face and cross-sectional views of the (A) human bronchial epithelial (16HBE)–Mac and (B) alveolar (A549)–Mac cocultures were acquired by confocal microscopy. Macs were identified by positive CD14 expression (green). The cell cytoskeleton was labeled with rhodamine–phalloidin for F-actin (red). Cell nuclei were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (blue). Images were acquired with 63× zoom. Cross-sectional view of the cocultures shows the Macs semiembedded within the epithelial cell monolayers. (C) Representative flow cytometric analysis of the 16HBE coculture shows a large population of CD45+, high side scatter (SSC) Macs adhere to the epithelial cells, as well as a small population of CD45+, low SSC T lymphocytes.

Table 1.

Composition of the 16HBE and A549 Coculture Models

| Culture Type | %CD45+ Macs | %CD45+ Lymphocytes |

|---|---|---|

| 16HBE coculture | 6.936 ± 0.3383 (n = 16) | 0.6975 ± 0.1120 (n = 16) |

| A549 coculture | 8.183 ± 0.5622 (n = 6) | 1.032 ± 0.2252 (n = 6) |

Definition of abbreviations: 16HBE, human bronchial epithelial cell line; A549, alveolar epithelial cell line; Macs, macrophages.

Data are shown as mean ± SEM.

Coculture of Macs with Epithelial Cells Alters Macs Immunophenotype and Reduces Phagocytic Activity

To determine the effects of coculturing on baseline Mac immunophenotype and activity, we compared surface receptor expression and phagocytosis between air-exposed Macs in mono- versus coculture. We assessed expression of the following surface receptors: CD14, a pattern recognition receptor commonly used to identify Macs and implicated in the response to O3 (29); the costimulatory protein, CD80, a marker of classically activated Macs (30); and the Mac mannose receptor (CD206) and scavenger receptor A1 (SRA1), markers of alternatively active Macs (13, 31). We found that Macs cocultured with either A549 or 16HBE had enhanced CD14 and CD80 expression and decreased phagocytosis compared with Macs in monoculture (Tables E3 and E4). In addition, coculture of Macs with 16HBE increased SRA1 and CD206 expression relative to Macs cultured alone, an effect that was not observed in Macs cocultured with A549 (Table E3). We also compared the immunophenotype of fresh BAL Macs to Macs cultured ex vivo (Table E3). Fresh BAL Macs had higher expression of CD206 and SRA1 than Macs in all cultures. Macs cocultured with either 16HBE or A549 had significantly increased CD14 expression than BAL Macs, and only Macs cocultured with 16HBE had significantly increased CD80 expression compared with BAL Macs. Together, these results show that signals derived from epithelial cells can alter the immunophenotype and phagocytic function of Macs present in the BAL.

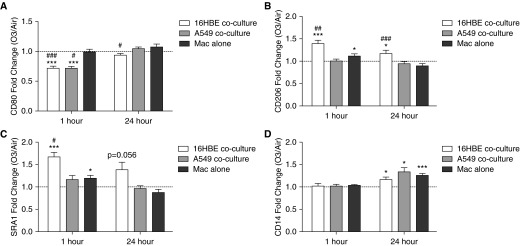

Coculture of Macs with Epithelial Cells Modifies Macs' Response to O3

We next assessed how coculture of Macs with epithelial cells modifies Mac immunophenotype and phagocytic activity in the context of O3 exposure. Mac CD14, CD80, SRA1, and CD206 expression was analyzed by flow cytometry 1 and 24 hours after exposure to air or O3. Macs cocultured with either 16HBE or A549 had decreased CD80 expression 1 hour after O3 exposure that remained slightly decreased 24 hours after exposure in Macs cocultured with16HBE, an effect that was not observed in Macs in monoculture (Figure 2A, Table E3, and Figure E3). Both Macs in monoculture and cocultured with 16HBE had significantly increased CD206 and SRA1 expression 1 hour after O3 exposure, but expression was significantly greater in Macs cocultured with 16HBE, and remained increased 24 hours after exposure (Figures 2B and 2C, Table E3, and Figure E3). Finally, we found similar increases in CD14 expression by Macs in all cultures 24 hours after exposure to O3 (Figure 2D, Table E3, and Figure E3).

Figure 2.

Coculture of Macs with epithelial cells modifies Mac immunophenotype in response to ozone (O3) exposure. Surface expression of (A) CD80, (B) CD206, (C) scavenger receptor A1 (SRA1), and (D) CD14 by Macs cocultured with 16HBE, A549, or grown on Transwells alone (Mac alone) was measured by flow cytometry 1 and 24 hours after exposure to 0.4 parts per million [ppm] O3 or air for 4 hours. Macs were distinguished from epithelial cells by positive CD45 staining. Data are shown as O3-exposed Mac mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) divided by air-exposed Mac MFI (fold change O3/air) ± SEM; n = 7–16 16HBE cocultures, n = 5 A549 cocultures, and n = 7–14 Macs alone. P values are as indicated or: *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, fold change greater than 1, one sample t test; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001, different from Macs alone, paired t test.

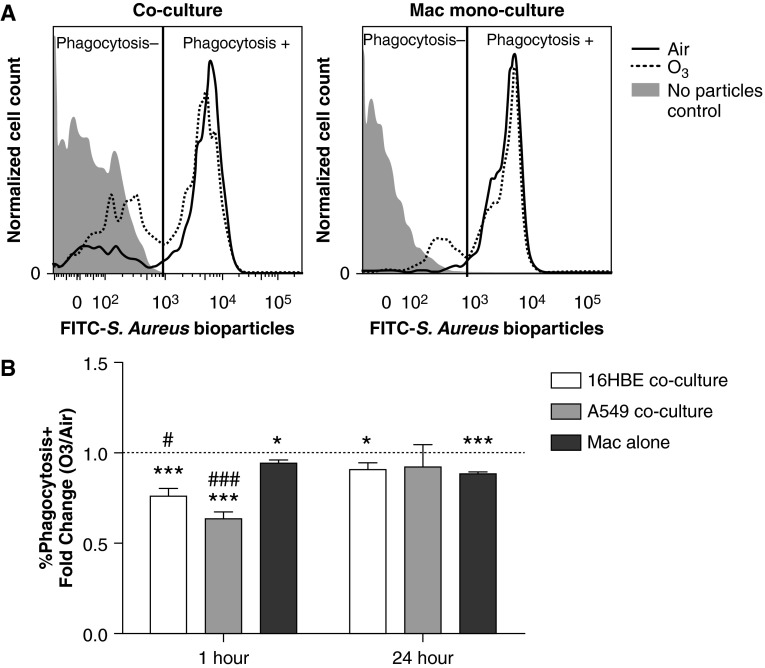

O3 exposure reduces Mac phagocytosis in vivo, which may contribute to enhanced susceptibility to infections after O3 exposure (21, 32, 33). Similarly, we found that exposure to O3 reduced phagocytosis of opsonized Staphylococcus aureus bioparticles by Macs in all cultures 1 hour after exposure, but that the reduction was greater in Macs cocultured with A549 or 16HBE compared with Macs in monoculture (Figure 3 and Table E4). The phagocytosis deficit was maintained by Macs in monoculture and Macs cocultured with 16HBE at 24 hours after exposure, but not in Macs cocultured with A549. Taken together, these results indicate that coculture of Macs with epithelial cells modifies Mac immunophenotype and phagocytosis in response to O3.

Figure 3.

Exposure to O3 reduces Mac phagocytosis of Staphylococcus aureus bioparticles. At 1 or 24 hours after exposure to 0.4 ppm O3 or air for 4 hours, Macs cocultured with 16HBE, A549, or grown on Transwells alone (Macs alone) were incubated with fluorescent S. aureus bioparticles for 1 hour and assessed for phagocytosis by flow cytometry. Macs were distinguished from epithelial cells by positive CD45 staining. (A) Representative histograms showing phagocytosis+ and phagocytosis− populations in a 16HBE–Mac coculture or Mac monoculture collected 24 hours after air or O3 exposure. (B) Data are expressed as percent of phagocytosis–positive O3-exposed Macs divided by percent of phagocytosis–positive air-exposed Macs (fold change O3/air) ± SEM; n = 8 16HBE cocultures, n = 4–5 A549 cocultures, and n = 6 Macs alone. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, fold change greater than 1, one sample t test; #P < 0.05, ###P < 0.001, different from Macs alone, unpaired t test. Data shown are mean (± SEM).

Coculture Modifies O3-Induced Cytotoxicity of Macs

Exposure to O3 damages both airway epithelial cells and Macs, leading to cell death and the release of danger signals that activate local immune cells (1, 12, 18). We investigated how coculturing Macs with epithelial cells modifies O3-induced cytotoxicity by propidium iodide (PI) staining, a marker of cell lysis. O3 significantly enhanced the percentage of PI-positive (PI+) Macs 1 hour after exposure in Macs cocultured with either A549 or 16HBE, but Macs in monoculture had only a trend for O3-induced cytotoxicity (Table 2). Conversely, epithelial cells were more resistant to O3-induced cytotoxicity, and only cocultured A549 had significantly increased PI+ staining that occurred 1 hour after O3 exposure (Table 3). Notably, O3 did not enhance cleaved caspase-3 in the cultures, suggesting that O3 exposure did not induce caspase-3–dependent apoptosis (Figure E4). Together, our results show that Mac susceptibility to O3-induced cytotoxicity is enhanced by coculturing with epithelial cells.

Table 2.

Summary of Macrophage Cytotoxicity

| Cell Culture Model | %PI+ Macs |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 h Air | 1 h O3 | 24 h Air | 24 h O3 | |

| 16HBE coculture | 15.47 ± 2.496 (n = 7)* | 49.83 ± 6.046 (n = 7)†,‡ | 11.54 ± 1.554 (n = 7)§ | 16.92 ± 2.510 (n = 7) |

| A549 coculture | 16.76 ± 2.515 (n = 5)* | 32.98 ± 5.741 (n = 5)†,§ | 16.88 ± 1.843 (n = 5)‡ | 26.6 ± 4.422 (n = 5)|| |

| Macs alone | 6.145 ± 0.7863 (n = 6) | 14.23 ± 4.125 (n = 6) | 7.297 ± 0.7934 (n = 6) | 16.05 ± 4.84 (n = 6) |

Definition of abbreviations: 16HBE, human bronchial epithelial cell line; A549, alveolar epithelial cell line; Macs, macrophages; O3, ozone; PI, propidium iodide.

Data shown as mean ± SEM.

P < 0.01 different from Macs, unpaired t test.

P < 0.01 different from air exposed, paired t test.

P < 0.001 different from Macs, unpaired t test.

P < 0.05 different from Macs, unpaired t test.

P < 0.05 different from air exposed, paired t test.

Table 3.

Summary of Epithelial Cell Cytotoxicity

| Cell Culture Model | %PI+ ECs |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 h Air | 1 h O3 | 24 h Air | 24 h O3 | |

| 16HBE coculture | 29.5 ± 6.324 (n = 7) | 31.57 ± 8.336 (n = 7) | 20.91 ± 1.265 (n = 7) | 21.59 ± 3.616 (n = 7) |

| 16HBE alone | 33.9 ± 7.135 (n = 4) | 39.7 ± 11.18 (n = 4) | 25.03 ± 4.435 (n = 4) | 28.9 ± 5.477 (n = 4) |

| A549 coculture | 23.66 ± 1.042 (n = 5) | 35.06 ± 0.9298 (n = 5)* | 34.9 ± 4.146 (n = 5) | 41.38 ± 7.472 (n = 5) |

| A549 alone | 27.03 ± 4.151 (n = 4) | 31.4 ± 4.747 (n = 4) | 23.73 ± 0.5543 (n = 4) | 30.95 ± 1.932 (n = 4) |

Definition of abbreviations: 16HBE, human bronchial epithelial cell line; A549, alveolar epithelial cell line; ECs, epithelial cells; O3, ozone; PI, propidium iodide.

Data shown as mean ± SEM.

P < 0.001 different from air exposed, paired t test.

Coculture of Macs with A549 Enhances O3-Induced IL-8 Production

The chemokine IL-8 is secreted by both Macs and airway epithelial cells, and recruits neutrophils to the site of O3-induced airway damage (1). We assessed how coculturing Macs with epithelial cells alters O3-induced IL-8 production. O3 significantly enhanced IL-8 production in all cultures 1 hour after exposure, and in A549 cocultures 24 hours after exposure (Figures 4A and 4B). Notably, the quantities of IL-8 at 24 hours after exposure were significantly greater in the A549 cocultures than Mac or A549 monocultures, suggesting that coculture of Macs with A549 synergistically enhances O3-induced IL-8 production.

Figure 4.

O3-induced IL-8 in cultures compared with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) from healthy volunteers exposed to O3 in vivo. Concentrations of IL-8 were measured in apical washes from (A) Macs alone, 16HBE cocultures, and 16HBE alone and (B) A549 cocultures and A549 alone collected 1 and 24 hours after exposure to 0.4 ppm O3 or air for 4 hours; n = 10–11 Macs alone, n = 16–17 16HBE cocultures, n = 15 16HBE alone, n = 6 A549 cocultures, and n = 5 A549 alone. (C) IL-8 was measured in BAL fluid from healthy volunteers exposed to 0.3 ppm O3 or air for 2 hours in vivo. BAL fluid was collected at 1 and 24 hours after exposure; n = 9–11. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, different from air, paired t test; #P < 0.05, different from Macs alone, paired t test; †P < 0.05, different from A549 alone, paired t test. Data shown are mean ± SEM.

O3 Modifies Mac Regulation of HA in Cocultures

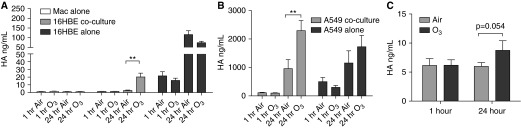

Elevated levels of the extracellular matrix protein, HA, in the lung contribute to airway hyperresponsiveness and inflammation after acute O3 exposure (6, 34). We found that, in air-exposed cultures, 16HBE and A549 constitutively produce HA, whereas HA was largely nondetectable in Mac monocultures (Figures 5A and 5B). When Macs were cocultured with 16HBE or A549, the concentration of HA in the cultures was starkly reduced, suggesting that Macs regulate the availability of HA in the cocultures. Exposure to O3 did not significantly alter production of HA by 16HBE or A549 in monoculture at 1 or 24 hours after exposure; however, we found significantly increased concentrations of HA in the 16HBE and A549 cocultures 24 hours after O3 exposure. Together, these results suggest that Macs regulate the availability of HA produced by epithelial cells, and that this regulation is altered by O3 exposure.

Figure 5.

O3 exposures increased hyaluronic acid (HA) in cocultures and BAL from healthy volunteers exposed in vivo. Concentrations of HA were measured in apical washes from (A) Macs alone, 16HBE cocultures, and 16HBE alone and (B) A549 cocultures and A549 alone collected 1 and 24 hours after exposure to 0.4 ppm O3 or air for 4 hours; n = 7 Macs alone, n = 9–10 16HBE cocultures, n = 8 16HBE alone, n = 6 A549 cocultures, and n = 5 A549 alone. (C) HA was measured in BAL fluid from healthy volunteers exposed to 0.3 ppm O3 or air for 2 hours in vivo. BAL fluid was collected at 1 and 24 hours after exposure; n = 9–11. P values are as indicated or **P < 0.01, different from air, paired t test. Data shown are mean ± SEM.

Exposure of Healthy Volunteers to O3 In Vivo Is Associated with Enhanced Levels of IL-8 and HA in the Airways

To test the in vivo relevance of the epithelial cell and Mac coculture models, we assessed levels of IL-8 and HA in BAL fluid from healthy volunteers collected 1 and 24 hours after exposure to 0.3 ppm O3 or air for 2 hours. Exposure to O3 significantly enhanced IL-8 levels in the BAL fluid both 1 and 24 hours after exposure (Figure 4C), whereas HA levels were increased in the BAL fluid only 24 hours after O3 exposure (Figure 5C). These results suggest that the 16HBE and A549 coculture models resemble the in vivo response to O3 in the airway.

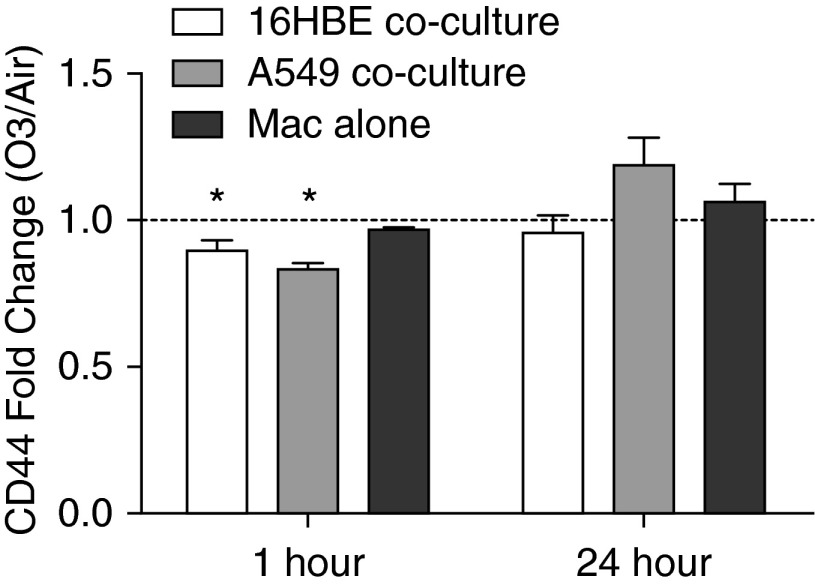

Exposure to O3 Reduces CD44 Expression by Macs in Coculture

Previous studies have shown that Macs clear HA via CD44-mediated endocytosis, and that CD44-deficient mice have increased HA accumulation in the airway after exposure to O3 (6, 35). We found that the increased HA in the cocultures was associated with reduced CD44 expression by Macs cocultured with either 16HBE or A549 1 hour after O3 exposure, an effect that was not observed in Mac monocultures (Figure 6 and Figure E3). These results suggest that signals from epithelial cells in response to O3 contribute to reduced CD44 expression by Macs, which, in turn, may impair Mac clearance of HA after exposure to O3.

Figure 6.

O3 exposure reduces expression of CD44 by Macs cocultured with 16HBE or A549. Surface expression of CD44 by Macs cocultured with 16HBE, A549, or grown on Transwells alone (Macs alone) was measured by flow cytometry 1 and 24 hours after exposure to 0.4 ppm O3 or air for 4 hours. Macs were distinguished from epithelial cells by positive CD45 staining. Data are shown as O3-exposed Mac MFI divided by air-exposed Mac MFI (fold change O3/air); n = 10 16HBE cocultures, n = 3 A549 cocultures, n = 4 Macs alone. *P < 0.05, fold change greater than 1, one-sample t test. Data shown are mean ± SEM.

Discussion

The adverse health effects of inhaled O3 are orchestrated by multiple cell types in the lung, including structural cells, such as airway epithelial cells, and resident immune cells, such as airway Macs. We investigated how the interaction between airway epithelial cells and Macs contributes to the innate immune response observed in humans exposed to O3, and compared how Mac response to O3 differs depending on coculturing with A549 versus 16HBE cells. Our results suggest that signals derived from epithelial cells modify Mac immunophenotype and response to O3, manifesting in lower phagocytosis and higher cytotoxicity, similar to in vivo observations (21, 36). Although Macs cocultured with either 16HBE or A549 had many similar responses, we found that coculturing with 16HBE induced a more alternative Mac phenotype after O3 exposure, whereas Mac–A549 cocultures had enhanced IL-8 production after O3 exposure. In both coculture models, production of the danger signal HA by epithelial cells in monoculture was not affected by O3 exposure, but availability of HA both in the in vitro coculture model and in BAL fluid from volunteers exposed in vivo was increased with O3 exposure, indicating that the effects of O3 on Mac phenotype and function manifest in impaired regulation of HA. Taken together, our results suggest that in vitro study of Mac response to O3 in isolation may mask important interactions with other cell types, such as airway epithelial cells, that influence the inflammatory response to O3.

Macs compose up to 95% of all cells in induced sputum, a technique that samples cells of the bronchial airways, and BAL fluid, demonstrating that large populations of Macs reside along both the alveolar and bronchial tissue and interact with local airway epithelial cells (27). Compared with other Macs in the body, airway Macs have a unique quiescent phenotype with relatively low phagocytic activity and cytokine production that prevents unnecessary inflammation in response to innocuous stimuli (37). Similarly, we show here that Macs cultured with either A549 or 16HBE have reduced baseline phagocytosis compared with Macs in monoculture (Table E4). Macs cocultured with 16HBE also had enhanced CD206 and SRA1 expression, markers of the antiinflammatory/alternatively activated phenotype (Table E3). Multiple Mac populations have been identified in the lung, including alveolar and interstitial Macs, and murine studies have shown that many Macs continue to be present in the lung even after multiple washings (9, 38, 39). Only adherent Macs in our coculture model were analyzed for the endpoints shown here, demonstrating less phagocytic function compared with Macs in monoculture (Figure 1 and Table E4). As interstitial Macs, which reside in the lung parenchyma and in direct contact with surrounding tissue, have lower phagocytic function than alveolar Macs, adherence to epithelial cells may shift Macs to a more interstitial-like phenotype compared with fresh BAL Macs (9, 38). Similar to those of previous studies, these results suggest that Mac interaction with epithelial cells promotes a quiescent state, and that Mac phenotype may differ depending on anatomical and spatial location in the lung (37, 38, 40).

Human exposure studies have shown that Mac immunophenotype and function is altered after exposure to O3, including defects in Mac phagocytosis and changes in surface marker expression, such as increased expression of CD14 and decreased expression of the costimulatory protein CD80 (21, 30, 36, 41). Using epithelial cell and primary Mac coculture models, we compared how coculture with alveolar versus bronchial epithelial cell lines alters Mac response to O3. Our results show that Macs cocultured with 16HBE or A549 had many similarities both at baseline and in response to O3, but had several important differences. In both coculture models, Macs cocultured with 16HBE or A549 had decreased phagocytosis and expression of CD80 and CD44 immediately after exposure, and increased CD14 expression 24 hours after exposure (Figures 2, 3, and 6). Macs in coculture with 16HBE, but not A549, had enhanced CD206 and SRA1 expression after O3 exposure, whereas Macs cocultured with A549, but not 16HBE, had a synergistic increase in IL-8 production after O3 exposure (Figures 2 and 4). These results demonstrate that interaction with bronchial epithelial cells induces a more alternatively activated phenotype, suggesting that tissue microenvironment along the respiratory tract may be a determinant of Mac immunophenotype and function in the context of pollutant exposure.

As indicated previously here, our results suggest that signals from epithelial cells promote an alternative Mac phenotype in response to O3, as shown by reduced phagocytosis, increased expression of CD206 and SRA1 (alternative activation markers), and decreased expression of CD80 (a classical activation marker) (Table E3 and Figures 2 and 3). Similarly, rodent studies have identified both classical and alternative Macs in the lung within 24 hours after exposure to O3, and found that suppression of classically activated Mac activity using gadolinium chloride was protective against O3-induced lung injury (14, 15). Although an alternatively activated state of Macs is necessary to resolve airway damage and control inflammation, it may also contribute to the enhanced susceptibility to respiratory infections that is associated with in vivo exposure to oxidant pollutants, such as O3 (32, 33, 42, 43). The reduced phagocytosis after O3 may be attributed to oxidation of surfactant protein A, an epithelial cell–derived component of the lung lining fluid and inducer of Mac phagocytosis, suggesting that oxidation of epithelial cell–derived mediators or epitopes by O3 may impair Mac phagocytosis (32). In addition, a recent murine study showed via live imaging that alveolar Macs remain immobile and attached to alveolar epithelial cells during S. aureus infection, suggesting that attachment of Macs to airway epithelial cells may also contribute to reduced Mac phagocytosis (39).

In the absence of secondary infections, exposure to O3 causes sterile inflammation that is mediated by the release of damage-associated signals, such as short fragments of HA (6, 44). Elevated HA has been observed in sputum from volunteers with allergic asthma exposed to O3 in vivo, and murine studies have shown that accumulation of HA in the airway after O3 exposure is associated with airway hyperresponsiveness (6, 8, 44). Clearance of HA fragments is necessary to limit inflammation and resolve tissue injury, and occurs in part by CD44-mediated HA endocytosis by cells such as Macs (7, 35). Our results indicate that 16HBE and A549 constitutively produce HA, and that coculture with Macs led to a stark reduction in HA availability (Figures 5A and 5B). Surprisingly, we did not observe an effect of O3 on HA production by 16HBE or A549; however, Mac-dependent regulation of 16HBE- or A549-derived HA was impaired by O3 exposure, leading to accumulation of HA in the cultures 24 hours after exposure. These data were confirmed in BAL fluid from healthy volunteers exposed in vivo, demonstrating elevated HA levels 24 hours after exposure to O3 (albeit not statistically significantly [P = 0.054]; Figure 5C). We hypothesize that the increased availability of HA in the airway after O3 exposure observed both in vivo and in vitro is not due to enhanced production by epithelial cells, but rather caused by a loss in Mac-dependent clearance, possibly related to reduced phagocytosis and CD44 expression after exposure to O3 (Figures 3 and 6).

In vitro coculture models present a controlled system to investigate the role of cell–cell interaction during immune cell activation. Although there are limitations to in vitro experimental systems, the coculture model shown here has many similarities to in vivo situations. In vivo O3 exposure has been associated with increased CD14 and CD80 expression and reduced phagocytosis by Macs, as shown in Figures 2 and 3 (21, 41). In addition, increased lactate dehydrogenase in BAL fluid is detected as early as 1 hour after in vivo O3 exposure, and initial reductions in Mac numbers in BAL fluid suggest early Mac cytotoxicity similar to findings here (Table 2) (21, 36). We also show similar increases in HA in the cocultures and BAL fluid of healthy volunteers 24 hours after exposure to O3 (Figure 5). A recent study showed that healthy volunteers exposed to 18O3-labeled gas in vivo had less 18O3 incorporation in bronchial biopsy samples than epithelial cells exposed to 18O3 in vitro at a similar dose, but that there were similar trends for IL-8 gene expression (24), suggesting that comparable effects are obtained by exposing epithelial cells in vivo and in vitro. We and others found significantly increased IL-8 in BAL fluid 1 and 24 hours after in vivo O3 exposure (41, 45), whereas O3-induced IL-8 production in the cultured cells occurred largely 1 hour after exposure (Figure 4), suggesting that infiltrating immune cells contribute to O3-induced IL-8, and likely other components of the innate immune response to O3. Similar to the heterogeneous population of immune cells interacting with epithelial cells in vivo, we also identified small populations of T lymphocytes and even smaller populations of dendritic cells in the cocultures, which may interact with and secrete mediators that alter epithelial cell or Mac phenotype in response to O3. Whether or not these cells affected overall mediator production in our coculture model was beyond the scope of the studies described here.

We found that treatment of Macs with conditioned media from air or O3 exposed epithelial cells had little effect on Mac immunophenotype, phagocytic activity, or viability (Table E5). Although it is possible that the conditioned media were too dilute or unstable mediators degraded rapidly, our data suggest that direct or local interactions between epithelial cells and Macs was largely necessary to affect Mac response to O3. These results are in agreement with previous airway epithelial cell–Mac coculture models that found that contact-dependent effects were necessary to potentiate inflammatory responses to particles or particulate matter (46–48). Future studies will be necessary to determine the specific receptor–ligand interactions that mediate the effects of coculture on Mac immunophenotype and response to O3.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates coculture models to study the interaction between respiratory epithelial cells and Macs in the response to O3 that have many similarities to in vivo findings, and indicates that interaction with epithelial cells is a determinant of Mac phenotype and response to O3. Our results add to the literature suggesting that monoculture systems do not fully reconstitute the biological response to pollutants, such as O3, and may mask the complex interaction between cell types that is required for these responses. Furthermore, these results suggest that epithelial cells not only serve as structural barriers against the inhaled environment, but also as orchestrators of immunity that influence immune cell phenotype and activity in the context of pollutant exposure. Improved understanding of the interaction between airway epithelial cells and immune cells, such as Macs, may reveal new therapeutic targets to modify immune cell function in the lung.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Environmental Public Health Division of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, specifically Dr. Andrew Ghio, Dr. Martha S. Carraway, Joleen Soukup, and Lisa Dailey for obtaining and processing the bronchoalveolar lavage samples. They also thank Dr. D. C. Gruenert for providing the 16HBE14o− cell line.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency through cooperative agreement CR83346301 with the Center for Environmental Medicine, Asthma, and Lung Biology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, but does not reflect the official views of the agency and has not been subjected to the agency’s required peer and policy review. No official endorsement should be inferred. This research was also funded by National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences grant R01ES013611. R.N.B. is supported in part by a grant to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill from Howard Hughes Medical Institute through the Med into Grad Initiative and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences T32ES007126 training grant.

Author Contributions: conception and design—R.N.B., L.M., and I.J.; sample preparation, processing, and acquisition of the data—R.N.B., K.E.D., and L.E.B.; analysis and interpretation—R.N.B. and I.J.; drafting and review of the manuscript for important intellectual content—R.N.B., L.M., I.J., and K.E.D.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2014-0035OC on July 23, 2014

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Hollingsworth JW, Kleeberger SR, Foster WM. Ozone and pulmonary innate immunity. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2007;4:240–246. doi: 10.1513/pats.200701-023AW. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Unhealthy air quality—United States, 2006–2009. 2011[updated 2011 Jan 14; accessed 2012 Dec 13]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/su6001a5.htm

- 3.Bauer RN, Diaz-Sanchez D, Jaspers I. Effects of air pollutants on innate immunity: the role of Toll-like receptors and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain–like receptors. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:14–24; quiz 25–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dahl M, Bauer AK, Arredouani M, Soininen R, Tryggvason K, Kleeberger SR, Kobzik L. Protection against inhaled oxidants through scavenging of oxidized lipids by macrophage receptors MARCO and SR-AI/II. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:757–764. doi: 10.1172/JCI29968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kirichenko A, Li L, Morandi MT, Holian A. 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal-protein adducts and apoptosis in murine lung cells after acute ozone exposure. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1996;141:416–424. doi: 10.1006/taap.1996.0307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garantziotis S, Li Z, Potts EN, Kimata K, Zhuo L, Morgan DL, Savani RC, Noble PW, Foster WM, Schwartz DA, et al. Hyaluronan mediates ozone-induced airway hyperresponsiveness in mice. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:11309–11317. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802400200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Research Misconduct Found]

- 7.Jiang D, Liang J, Fan J, Yu S, Chen S, Luo Y, Prestwich GD, Mascarenhas MM, Garg HG, Quinn DA, et al. Regulation of lung injury and repair by toll-like receptors and hyaluronan. Nat Med. 2005;11:1173–1179. doi: 10.1038/nm1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hernandez ML, Lay JC, Harris B, Esther CR, Jr, Brickey WJ, Bromberg PA, Diaz-Sanchez D, Devlin RB, Kleeberger SR, Alexis NE, et al. Atopic asthmatic subjects but not atopic subjects without asthma have enhanced inflammatory response to ozone. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:537–544.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.06.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lohmann-Matthes ML, Steinmuller C, Franke-Ullmann G. Pulmonary macrophages. Eur Respir J. 1994;7:1678–1689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Proud D, Leigh R. Epithelial cells and airway diseases. Immunol Rev. 2011;242:186–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leikauf GD, Simpson LG, Santrock J, Zhao Q, Abbinante-Nissen J, Zhou S, Driscoll KE. Airway epithelial cell responses to ozone injury. Environ Health Perspect. 1995;103:91–95. doi: 10.1289/ehp.95103s291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kosmider B, Loader JE, Murphy RC, Mason RJ. Apoptosis induced by ozone and oxysterols in human alveolar epithelial cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;48:1513–1524. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.02.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laskin DL, Sunil VR, Gardner CR, Laskin JD. Macrophages and tissue injury: agents of defense or destruction? Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2011;51:267–288. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.010909.105812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pendino KJ, Meidhof TM, Heck DE, Laskin JD, Laskin DL. Inhibition of macrophages with gadolinium chloride abrogates ozone-induced pulmonary injury and inflammatory mediator production. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1995;13:125–132. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.13.2.7542894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sunil VR, Patel-Vayas K, Shen J, Laskin JD, Laskin DL. Classical and alternative macrophage activation in the lung following ozone-induced oxidative stress. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2012;263:195–202. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2012.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guth AM, Janssen WJ, Bosio CM, Crouch EC, Henson PM, Dow SW. Lung environment determines unique phenotype of alveolar macrophages. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009;296:L936–L946. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.90625.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Becker S, Madden MC, Newman SL, Devlin RB, Koren HS. Modulation of human alveolar macrophage properties by ozone exposure in vitro. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1991;110:403–415. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(91)90042-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahmad S, Ahmad A, McConville G, Schneider BK, Allen CB, Manzer R, Mason RJ, White CW. Lung epithelial cells release ATP during ozone exposure: signaling for cell survival. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;39:213–226. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Devlin RB, McKinnon KP, Noah T, Becker S, Koren HS. Ozone-induced release of cytokines and fibronectin by alveolar macrophages and airway epithelial cells. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:L612–L619. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1994.266.6.L612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kesic MJ, Meyer M, Bauer R, Jaspers I. Exposure to ozone modulates human airway protease/antiprotease balance contributing to increased influenza A infection. PLoS One. 2012;7:e35108. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Devlin RB, McDonnell WF, Becker S, Madden MC, McGee MP, Perez R, Hatch G, House DE, Koren HS. Time-dependent changes of inflammatory mediators in the lungs of humans exposed to 0.4 ppm ozone for 2 hr: a comparison of mediators found in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid 1 and 18 hr after exposure. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1996;138:176–185. doi: 10.1006/taap.1996.0111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stone KC, Mercer RR, Gehr P, Stockstill B, Crapo JD. Allometric relationships of cell numbers and size in the mammalian lung. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1992;6:235–243. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb/6.2.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Power CK, Burke CM, Sreenan S, Hurson B, Poulter LW. T-cell and macrophage subsets in the bronchial wall of clinically healthy subjects. Eur Respir J. 1994;7:437–441. doi: 10.1183/09031936.94.07030437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hatch GE, Duncan KE, Diaz-Sanchez D, Schmitt MT, Ghio AJ, Carraway MS, McKee J, Dailey LA, Berntsen J, Devlin RB. Progress in assessing air pollutant risks from in vitro exposures: matching ozone dose and effect in human airway cells. Toxicol Sci. (In press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Muller L, Brighton LE, Jaspers I. Ozone exposed epithelial cells modify co-cultured natural killer cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2013;304:L332–L341. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00256.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim CS, Alexis NE, Rappold AG, Kehrl H, Hazucha MJ, Lay JC, Schmitt MT, Case M, Devlin RB, Peden DB, et al. Lung function and inflammatory responses in healthy young adults exposed to 0.06 ppm ozone for 6.6 hours. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:1215–1221. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201011-1813OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lay JC, Peden DB, Alexis NE. Flow cytometry of sputum: assessing inflammation and immune response elements in the bronchial airways. Inhal Toxicol. 2011;23:392–406. doi: 10.3109/08958378.2011.575568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harbeck RJ. Immunophenotyping of bronchoalveolar lavage lymphocytes. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1998;5:271–277. doi: 10.1128/cdli.5.3.271-277.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hernandez ML, Harris B, Lay JC, Bromberg PA, Diaz-Sanchez D, Devlin RB, Kleeberger SR, Alexis NE, Peden DB. Comparative airway inflammatory response of normal volunteers to ozone and lipopolysaccharide challenge. Inhal Toxicol. 2010;22:648–656. doi: 10.3109/08958371003610966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ambarus CA, Krausz S, van Eijk M, Hamann J, Radstake TR, Reedquist KA, Tak PP, Baeten DL. Systematic validation of specific phenotypic markers for in vitro polarized human macrophages. J Immunol Methods. 2012;375:196–206. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2011.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Canton J, Neculai D, Grinstein S. Scavenger receptors in homeostasis and immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:621–634. doi: 10.1038/nri3515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mikerov AN, Umstead TM, Gan X, Huang W, Guo X, Wang G, Phelps DS, Floros J. Impact of ozone exposure on the phagocytic activity of human surfactant protein A (SP-A) and SP-A variants. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;294:L121–L130. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00288.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karavitis J, Kovacs EJ. Macrophage phagocytosis: effects of environmental pollutants, alcohol, cigarette smoke, and other external factors. J Leukoc Biol. 2011;90:1065–1078. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0311114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garantziotis S, Li Z, Potts EN, Lindsey JY, Stober VP, Polosukhin VV, Blackwell TS, Schwartz DA, Foster WM, Hollingsworth JW. TLR4 is necessary for hyaluronan-mediated airway hyperresponsiveness after ozone inhalation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:666–675. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200903-0381OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Research Misconduct Found]

- 35.Culty M, Nguyen HA, Underhill CB. The hyaluronan receptor (CD44) participates in the uptake and degradation of hyaluronan. J Cell Biol. 1992;116:1055–1062. doi: 10.1083/jcb.116.4.1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Devlin RB, McDonnell WF, Mann R, Becker S, House DE, Schreinemachers D, Koren HS. Exposure of humans to ambient levels of ozone for 6.6 hours causes cellular and biochemical changes in the lung. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1991;4:72–81. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb/4.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hussell T, Bell TJ. Alveolar macrophages: plasticity in a tissue-specific context. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14:81–93. doi: 10.1038/nri3600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bedoret D, Wallemacq H, Marichal T, Desmet C, Quesada Calvo F, Henry E, et al. Lung interstitial macrophages alter dendritic cell functions to prevent airway allergy in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:3723–3738. doi: 10.1172/JCI39717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Westphalen K, Gusarova GA, Islam MN, Subramanian M, Cohen TS, Prince AS, Bhattacharya J. Sessile alveolar macrophages communicate with alveolar epithelium to modulate immunity. Nature. 2014;506:503–506. doi: 10.1038/nature12902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Holt PG. Down-regulation of immune responses in the lower respiratory tract: the role of alveolar macrophages. Clin Exp Immunol. 1986;63:261–270. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alexis NE, Lay JC, Hazucha M, Harris B, Hernandez ML, Bromberg PA, Kehrl H, Diaz-Sanchez D, Kim C, Devlin RB, et al. Low-level ozone exposure induces airways inflammation and modifies cell surface phenotypes in healthy humans. Inhal Toxicol. 2010;22:593–600. doi: 10.3109/08958371003596587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mikerov AN, Gan X, Umstead TM, Miller L, Chinchilli VM, Phelps DS, Floros J. Sex differences in the impact of ozone on survival and alveolar macrophage function of mice after Klebsiella pneumoniae infection. Respir Res. 2008;9:24. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-9-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gilmour MI, Selgrade MK. A comparison of the pulmonary defenses against streptococcal infection in rats and mice following O3 exposure: differences in disease susceptibility and neutrophil recruitment. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1993;123:211–218. doi: 10.1006/taap.1993.1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li Z, Potts-Kant EN, Garantziotis S, Foster WM, Hollingsworth JW. Hyaluronan signaling during ozone-induced lung injury requires TLR4, MyD88, and TIRAP. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27137. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Research Misconduct Found]

- 45.Jörres RA, Holz O, Zachgo W, Timm P, Koschyk S, Müller B, Grimminger F, Seeger W, Kelly FJ, Dunster C, et al. The effect of repeated ozone exposures on inflammatory markers in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and mucosal biopsies. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:1855–1861. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.6.9908102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fujii T, Hayashi S, Hogg JC, Mukae H, Suwa T, Goto Y, Vincent R, van Eeden SF. Interaction of alveolar macrophages and airway epithelial cells following exposure to particulate matter produces mediators that stimulate the bone marrow. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2002;27:34–41. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.27.1.4787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tao F, Kobzik L. Lung macrophage–epithelial cell interactions amplify particle-mediated cytokine release. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2002;26:499–505. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.26.4.4749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Manzer R, Dinarello CA, McConville G, Mason RJ. Ozone exposure of macrophages induces an alveolar epithelial chemokine response through IL-1α. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2008;38:318–323. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2007-0250OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]