Abstract

Surgical site infections (SSIs) result in patient morbidity and increased costs. The purpose of this study was to determine reasons underlying SSI to enable interventions addressing identified factors. Combining data from the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Project with medical record extraction, we evaluated 365 patients who underwent colon resection from January 2009 to December 2012 at a single institution. Of the 365 patients, 84 (23%) developed SSI. On univariate analysis, significant risk factors included disseminated cancer, ileostomy, patient temperature less than 36°C for greater than 60 minutes, and higher glucose level. The median number of cases per surgeon was 36, and a case volume below the median was associated with a higher risk of SSI. On multivariate analysis, significant risks associated with SSI included disseminated cancer (odds ratio [OR], 4.31; P < .001); surgery performed by a surgeon with less than 36 cases (OR, 2.19; P = .008); higher glucose level (OR, 1.06; P =.017); and transfusion of five units or more of blood (OR, 3.26; P =.029). In this study we found both modifiable and unmodifiable factors associated with increased SSI. Identifying modifiable risk factors enables targeting specific areas to improve the quality of care and patient outcomes.

Surgical site infections (SSIs) lead to tremendous morbidities in patients and increased costs for hospitals. Infection rates after colorectal surgery have been noted to be as high as 30 per cent.1 Several initiatives have aimed to reduce the risk of SSIs.2–4 Factors such as choice of perioperative antibiotics have been shown to be important in reducing SSIs.5 Other factors such as normothermia have been shown to have an inverse relationship to SSIs.6 In this single-institution evaluation of SSI, 22 percent of readmissions were the result of SSIs. Based on data from the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP), which compares infection rates at similar hospitals, this institution was a high outlier in SSIs after colectomy when compared with peer institutions. The exact reasons for this higher rate are unclear. The goal of this study was to investigate the factors associated with developing a SSI. If these factors are identified and modifiable, then they can be potentially altered to decrease SSI rates after colon re-section and improve patient outcomes.

The primary hypotheses were that certain factors contributed to higher risk of developing a SSI: males; body mass index (BMI), above normal; diabetes; low albumin; higher Charlson comorbidity score7; low hematocrit; having received a transfusion; or the presence of a colostomy or ileostomy at the beginning or end of the operation. We also hypothesized that hypothermia (patients who had body temperatures less than 36°C during the operation, continued at less than 36°C for longer than 60 minutes, or whose temperature was less than 36°C at the end of the case) increased the risk of developing a wound infection, and patients whose abdomen was prepped with something other than Chloraprep were at increased risk of developing a wound infection; and if they did not receive appropriate antibiotics or appropriate redosing, they were also at increased risk of developing a SSI. An additional hypothesis was that smokers, people with higher than American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Class 3, and people on steroids have an increased risk of a wound infection, and that diabetics and patients with glucose values over 200 mg/dL are also at increased risk of SSI.

Methods

Patient Cohort

A retrospective cohort study of 365 patients who underwent a partial or total colon resection without proctectomy was conducted at a single institution using the American College of Surgeons NSQIP data representing January 2009 to December 2012. These data included 13 unique Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) descriptions: eight open and five laparoscopic procedure types. The primary outcome was developing a SSI by NSQIP criteria. NSQIP criteria are an infection that occurs within 30 days after the operation of the skin and subcutaneous tissue and at least one of the following: purulent drainage, organisms isolated from an aseptically obtained culture of fluid or tissue, and at least one the following: pain or tenderness, localized swelling, redness, or heat or an incision that was deliberately opened, unless the culture is negative, or diagnosed by the surgeon as having a SSI.

Procedural Details

The variables obtained from the NSQIP database included: SSI status (yes/no), age, gender, race, ASA class, smoking status, diabetes, presence of disseminated cancer, transfusion of at least 5 units of packed red blood cells within 72 hours perioperatively, steroid use, BMI, CPT, hematocrit, albumin, creatinine, and surgeon volume. Additional information for each patient was obtained through medical chart extraction. These variables were: ileostomy or colostomy presence at the beginning and/or end of the case, appropriate redosing antibiotics intraoperatively, appropriate use of preoperative antibiotics that include gastrointestinal micro-organism coverage, type of surgical preparation used on the abdomen, intraoperative body temperatures less than 36°C, length of time the patient was less than 36°C, temperature at the end of the case, the lowest postanesthesia care unit temperature recorded, Charlson comorbidity score, and glucose measurements within 48 hours postoperatively. The purpose of this data collection and analysis was to determine risk factors for SSI at one institution and target areas for improvement and risk prevention or reduction.

Statistical Analysis

The summary statistics were calculated for continuous variables and frequency table was used for categorical variables. The univariate association with wound infection was carried out by χ2 test for categorical covariates and analysis of variance for continuous covariates. The unadjusted association with wound infection was also tested by univariate logistic regression to obtain an odds ratio. Logistic regression model was used to build multivariable model by backward elimination with stay criteria of P < 0.2. Receiver operating characteristic analysis was used to identify the optimal cut point for some continuous predictors to wound infection. The analysis was conducted using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R 1.1 (http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=optimalcutpoints). Tables and figures were made using Microsoft Excel (Redmond, WA) and GraphPad Prism 4 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA). Significant level was set at 0.05.

Results

Of 365 patients in the study population, 84 (23%) developed a SSI. Tables 1 and 2 summarize patient characteristics and demographics for the patients in the study.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Variable | n = 365 | Percent | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wound infection | No | 281 | 77 |

| Yes | 84 | 23 | |

| Gender | Male | 190 | 52.1 |

| Race | Asian | 6 | 1.6 |

| Black | 89 | 24.4 | |

| Unknown | 9 | 2.5 | |

| White | 261 | 71.5 | |

| ASA class | 1 | 2 | 0.5 |

| 2 | 126 | 34.6 | |

| 3 | 200 | 54.9 | |

| 4 | 33 | 9.1 | |

| 5 | 3 | 0.8 | |

| Smoker | Yes | 58 | 15.9 |

| Diabetes | No | 320 | 87.7 |

| Noninsulin-dependent | 25 | 6.8 | |

| Insulin-dependent | 20 | 5.5 | |

| Disseminated cancer | Yes | 36 | 9.9 |

| Transfusion (5 units) | Yes | 21 | 5.8 |

| Steroid use | Yes | 43 | 11.8 |

| Ileostomy_end | Yes | 41 | 11.2 |

| Colostomy_end | Yes | 35 | 9.6 |

| Ileostomy_beginning | Yes | 8 | 2.2 |

| Colostomy_beginning | Yes | 5 | 1.4 |

| Antibiotic redosing | Yes | 352 | 98.6 |

| Appropriate antibiotic coverage | Yes | 329 | 90.1 |

| Surgical preparation (Chloraprep) | Yes | 298 | 81.6 |

| Surgeon volume (median 36) | ≤36 | 184 | 50.4 |

| Temperature < 36°C for ≤ 60 minutes | Yes | 198 | 56.6 |

| Laparoscopy | Yes | 127 | 34.8 |

| Highest glucose (48 hours) | ≤200 | 290 | 80.1 |

ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists.

Table 2.

Patient Characteristics

| Mean | Median | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 56.8 | 57 | 19–92 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.5 | 26 | 13.7–53.3 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 35.2 | 35.8 | 15.2–18.9 |

| Glucose within 48 hours (mg/dL) | 166 | 153 | 75–163 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.43 | 3.5 | 1.3–1.8 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.01 | 0.89 | 0.4–8.67 |

| Charlson comorbidity score | 4.72 | 5 | 1 to 11 |

| Surgeon volume (no. of cases) | 45.1 | 36 | 1 to 95 |

| Lowest body temperature (°C) | 35.6 | 35.6 | 33.9–37.8 |

| Temperature at end of case (°C) | 36.6 | 36.6 | 35.0–39.7 |

| Lowest PACU temperature (°C) | 36.4 | 36.4 | 35.5–37.7 |

BMI, body mass index; PACU, postanesthesia care unit.

In the univariate logistic regression analysis, the following variables were statistically significant with P < 0.05 (Fig. 1): disseminated cancer, ileostomy presence at the beginning of the case, surgeon volume, patient body temperature below 36°C for greater than 60 minutes, length of time patient temperature below 36°C, and highest glucose within 48 hours. In this study, a patient with disseminated cancer had a 3.99 increased odds of developing a SSI and the presence of an ileostomy at the beginning of the case conferred a 5.86 increased odds of developing a SSI. If the surgery was performed by a surgeon with less than 36 colectomies, the odds of developing a SSI increased by 1.72. For every 10 minutes the patient's temperature was less than 36°C, the odds of developing a SSI increased 1.03, but if the hypothermia lasted less than 60 minutes, the odds decreased by 44 per cent. When the highest glucose was examined as a continuous variable, for every 10-mg/dL increase in glucose, the odds of developing a SSI increased by 1.06.

Fig. 1.

Univariate regression analysis. Univariate regression analysis with odds ratio and 95 per cent confidence interval denoted by the lines. The scale is logarithmic. Only P values < 0.05 are shown. Dotted line shows X = 1.

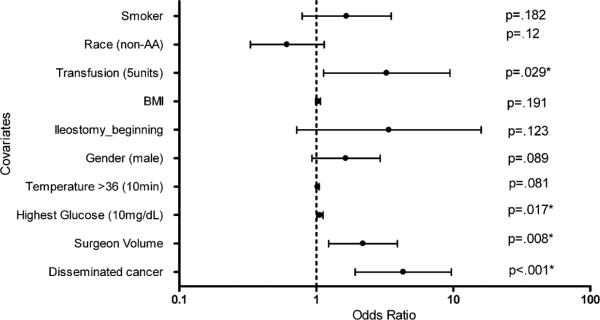

In the multivariate logistic regression model, the following variables were statistically significant with P < 0.05 (Fig. 2): disseminated cancer, surgeon volume, highest glucose within 48 hours, and whether the patient had a transfusion of at least five units of packed red cells. A patient with disseminated cancer had a 4.31 increased odds of developing a SSI. A surgeon with less than 36 cases increased the odds of the patient developing a SSI by 2.19. When the highest glucose within 48 hours was examined as a continuous variable, for every 10-mg/dL increase in glucose, the patient had an additional 6 per cent increase chance of developing a SSI.

Fig. 2.

Multivariate regression model. Multivariate regression analysis with odds ratio and 95 per cent confidence interval denoted by the lines. The scale is logarithmic. Dotted line shows X = 1. All P values are shown and asterisk shows P < 0.05.

Discussion

In this study we looked at several factors and patient characteristics obtained from the American College of Surgeons NSQIP combined with medical chart extraction to develop a predictive model for SSIs. Both modifiable and unmodifiable factors were found to be associated with SSI. When adjusted for the other covariates, independent risk factors associated with developing a SSI included disseminated cancer, a surgeon with less than the median number of cases (36 cases), transfusion requirement of five units or greater packed red cells, and higher glucose levels within 48 hours of surgery.

Studies have indicated that the type of preoperative antibiotics given is an important risk factor in SSI8; however, this was not the case in our study population. A possible explanation is that there were 29 different antibiotic combinations used and thus diluted the possible effects of antibiotic type. Updated recommendations published in 2011 advice intraoperative redosing based on renal function to control surgical site infections.9 This variable was not statistically significant in this study, likely because 98.6 per cent of patients were redosed with antibiotics in the operating room. In some studies, normothermia has been found to have an inverse relationship with SSI.6 Our data suggest this is true in our patient population: for every 10 minutes longer a patient's body temperature was less than 36°C, he or she had an additional two per cent increase chance of developing an SSI. This was significant in our univariate regression analysis but did not hold statistical significance in our multivariate model. Confounding variables are likely contributing to this effect.

Hyperglycemia is associated with SSIs in diabetics.10 This study found that, independent of diabetic status, for every 10-mg/dL increase, patients have an additional six per cent increase chance of developing an SSI. Perioperative blood transfusions are associated with SSIs.11, 12 Our study results were consistent with this association from previous reports, and in our multivariate model, transfusion of five units or greater of packed red blood cell was associated with a 3.26 increased odds of developing an SSI. This may be the result of the immunosuppressive effects of blood transfusion or because it is a marker of disease severity. A recent study found inflammatory bowel disease to be associated with increased SSI;13 we found disseminated cancer to be highly associated with developing an SSI (odds ratio, 4.3). Advanced tumor stage has been found to be an independent risk factor for infectious complications,14 although we did not specifically look at tumor stage in our study.

There are conflicting data on the use of bowel preparation and the use of oral antibiotics with bowel preparation; however, recent studies have supported the use of oral antibiotics when using a bowel preparation. Unfortunately, our medical records were limited in this retrospective study and we were unable to accurately decipher which patients had been bowel prepped or the type of bowel preparation used. Future studies should encompass this variable.

Surgeon volume was found to be inversely related to SSI rate in our study. The exact reasons for this are unclear. Perhaps less experienced surgeons took longer to perform the surgery or do not have a “standard” way of doing the operation and thus introduce more variability. Future studies should further investigate the reasons for the importance of surgeon volume as it relates to SSI.

This study was limited by its retrospective, non-randomized, and single-institution study design. In an attempt to overcome some of the limitations of a database study, a medical chart review was conducted as an adjunct to the NSQIP database information. This study was further limited by the information in the medical record. Temperature and glucose measurements were not done at standard intervals for all patients. This limited the type of analysis and conclusions we could make. Additionally, there were 23 surgeons and 29 different antibiotic combinations used during the 3-year study period. This decreased the ability to make reliable conclusions about the data. Because preoperative antibiotic choice has been shown to be an important factor in preventing SSI, standardizing antibiotic choices at our institution will be an important step. Future endeavors include implementing standardized protocols for clinical practice and standardized protocols for recordkeeping so better analysis can be done and ideally patients can be randomized to a control and experimental group.

The aim of this study was to determine the risk factors associated with SSI with the future goal of addressing these factors to decrease the institutional SSI rate after colon resection and improve patient outcomes. We found both modifiable and unmodifiable factors associated with SSI. Disseminated cancer was strongly associated with developing an SSI. Modifiable factors included surgeon volume, peri-operative transfusion, and glucose control. These findings will guide our future steps in implementing standardized protocols for transfusion indications, temperature monitoring, and glucose monitoring and control. These protocols will need to be developed by a core group of experienced surgeons who perform the majority of colon resections in this patient population. Drawing from the evidence base that exists, along with expert opinion and group consensus, we will establish new guidelines to be followed to reduce SSI at this institution and compare findings with other NSQIP institutions.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the hard work and input by the Wound Infection Group (WIG) and the NSQIP team, which has made this study possible.

Research reported in this publication was supported in part by the Biostatistics and Bioinformatics of Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University and the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute under award number P30CA138292. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Presented at the Annual Scientific Meeting and Postgraduate Course Program, Southeastern Surgical Congress, Savannah, GA, February 22–25, 2014.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bull A, Wilson J, Worth LJ, et al. A bundle of care to reduce colorectal surgical infections: an Australian experience. J Hosp Infect. 2011;78:297–301. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2011.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berenguer CM, Ochsner MG, Jr., Lord SA, et al. Improving surgical site infections: using National Surgical Quality Improvement Program data to institute Surgical Care Improvement Project protocols in improving surgical outcomes. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210:737–743. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith RL, Bohl JK, McElearney ST, et al. Wound infection after elective colorectal resection. Ann Surg. 2004;239:599–605. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000124292.21605.99. discussion 605–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wick EC, Hobson DB, Bennett JL, et al. Implementation of a surgical comprehensive unit-based safety program to reduce surgical site infections. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;215:193–200. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hendren SK, Morris AM. Evaluating patients undergoing colorectal surgery to estimate and minimize morbidity and mortality. Surg Clin North Am. 2013;93:1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2012.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kurz A, Sessler DI, Lenhardt R. Perioperative normothermia to reduce the incidence of surgical-wound infection and shorten hospitalization. Study of Wound Infection and Temperature Group. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1209–15. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199605093341901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–83. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hendren S, Fritze D, Banerjee M, et al. Antibiotic choice is independently associated with risk of surgical site infection after colectomy: a population-based cohort study. Ann Surg. 2013;257:469–75. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31826c4009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alexander JW, Solomkin JS, Edwards MJ. Updated recommendations for control of surgical site infections. Ann Surg. 2011;253:1082–93. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31821175f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McConnell YJ, Johnson PM, Porter GA. Surgical site infections following colorectal surgery in patients with diabetes: association with postoperative hyperglycemia. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:508–15. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0734-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tang R, Chen HH, Wang YL, et al. Risk factors for surgical site infection after elective resection of the colon and rectum: a single-center prospective study of 2,809 consecutive patients. Ann Surg. 2001;234:181–9. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200108000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Halabi WJ, Jafari MD, Nguyen VQ, et al. Blood transfusions in colorectal cancer surgery: incidence, outcomes, and predictive factors: an American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program analysis. Am J Surg. 2013;206:1024–32. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2013.10.001. discussion 1032–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drosdeck J, Harzman A, Suzo A, et al. Multivariate analysis of risk factors for surgical site infection after laparoscopic colorectal surgery. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:4574–80. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-3126-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bot J, Piessen G, Robb WB, et al. Advanced tumor stage is an independent risk factor of postoperative infectious complications after colorectal surgery: arguments from a case-matched series. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:568–76. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e318282e790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]