Abstract

Aims/Hypothesis

Irisin is a novel, myocyte secreted, hormone that has been proposed to mediate the beneficial effects of exercise on metabolism. Irisin is expressed, at lower levels, in human brains and knock-down of the precursor of irisin, FNDC5, decreases neural differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells. No previous studies have evaluated whether irisin may directly regulate hippocampal neurogenesis in mouse hippocampal neuronal (HN) cells.

Methods

Hippocampal neurogenesis as well as irisin signaling were studied in vitro using mouse H19-7 HN cell lines.

Results

We observed that cell proliferation is regulated by irisin in a dose-dependent manner in mouse H19-7 HN cells. Specifically, physiological concentrations of irisin, 5 to 10 nM, had no effect on cell proliferation when compared to control. By contrast, pharmacological concentrations of irisin, 50 to 100 nM, increased cell proliferation when compared to control. Similar to these results regarding irisin’s effects on cell proliferation, we also observed that only pharmacological concentrations of irisin increased STAT3, but not AMPK and/or ERK, activation. Finally, we observed that irisin did not activate either microtubule-associated protein 2, a specific neurite outgrowth marker, or Synapsin, a specific synaptogenesis marker in mouse H19-7 HN cells.

Conclusions/Interpretations

Our data suggest that irisin, in pharmacological concentrations, increases cell proliferation in mouse H19-7 HN cells via STAT3, but not AMPK and/or ERK, signaling pathways. By contrast, neither physiological nor pharmacological concentrations of irisin alter markers of hippocampal neurogenesis in mouse H19-7 HN cell lines.

Keywords: irisin, signaling, hippocampal neurogenesis

Introduction

Muscle has recently been recognized as an endocrine organ that releases a variety of cytokines, termed myokines, which regulate several physiological and metabolic pathways to alter metabolism through communication and interaction with other tissues including fat, liver, and the pancreas (1–4). Irisin is a recently identified myokine that has been found to serve as a chemical messenger that generates key exercise-induced health benefits in animals and humans (5–7). Irisin is highly conserved across species and exercise increases circulating irisin concentrations in humans (5). Irisin has also been proposed to be a link between physical activity and energy/metabolic homeostasis, and to be involved in processes implicated in the homeostatic control of body weight (8). Since the structure of irisin, an endogenous circulating molecule that mediates some of the benefits of exercise and activates beige fat cells in rodents (9), is highly conserved among species (5), it is possible that similar effects may exist in humans. Thus, irisin, a novel myokine (8–11), could be a rational target for future therapeutic approaches aiming at disease states caused by inactivity and/or chronic caloric excess, such as obesity and diabetes (8–9).

Neurogenesis is regulated by physiological and pathological events and may be modulated by pharmacological manipulations at any of three primary stages: cell proliferation, differentiation, and survival (12–14). Neurogenesis in the hippocampus has been found to be negatively influenced by stress, and is suppressed in various animal models of depression (14). Conversely, new neuron generation in the hippocampus is stimulated by treatment with anti - depressants (15). Neurotrophins, growth factors, and cytokines have also been shown to be capable of modulating neurogenesis of the hippocampus (15–16).

We and others have recently demonstrated that irisin is expressed in human brain (17–18). It has also been shown that knock-down of the precursor of irisin, FNDC5, decreases neural differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells (18). However, no previous studies have evaluated whether irisin may directly regulate hippocampal neurogenesis in mouse hippocampal neuronal (HN) cells. In this study, we investigated the effect of irisin on cell proliferation and differentiation in the mouse H19-7 HN cells. We also characterized the possible signaling mechanisms by which irisin exerts its effects on hippocampal neurogenesis in the mouse H19-7 HN cells.

Methods

Materials

Human recombinant irisin was purchased from Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, INC. (Burlingame, CA, USA) and/or Aviscera Biosciences (Santa Clara, CA, USA). All primary and secondary antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotech (Santa Cruz, CA, USA).

Cell culture

Mouse H19-7 HN cell lines were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). The cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA) with 10% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum. All cells were incubated at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air, and sub-cultured beyond 80% confluency.

Proliferation assay

The Cell proliferation assay was performed using the MTT proliferation kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) as described by the supplier.

Western Blotting

The Western Blotting was performed as described previously (19). Measurement of signal intensity on nitrocellulose membranes after Western Blotting with various antibodies was performed using Image J processing and analysis software (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/, August 25th, 2011).

Statistical analysis

All signaling data were analyzed using Student’s t-test and/or one-way ANOVA followed by post-hoc tests (Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons). All analyses were performed using SPSS version 11.5 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and Stata version 11.1 (Stata Corp. College Station, TX).

Results

Regulation of cell proliferation by irisin in mouse H19-7 HN cell lines

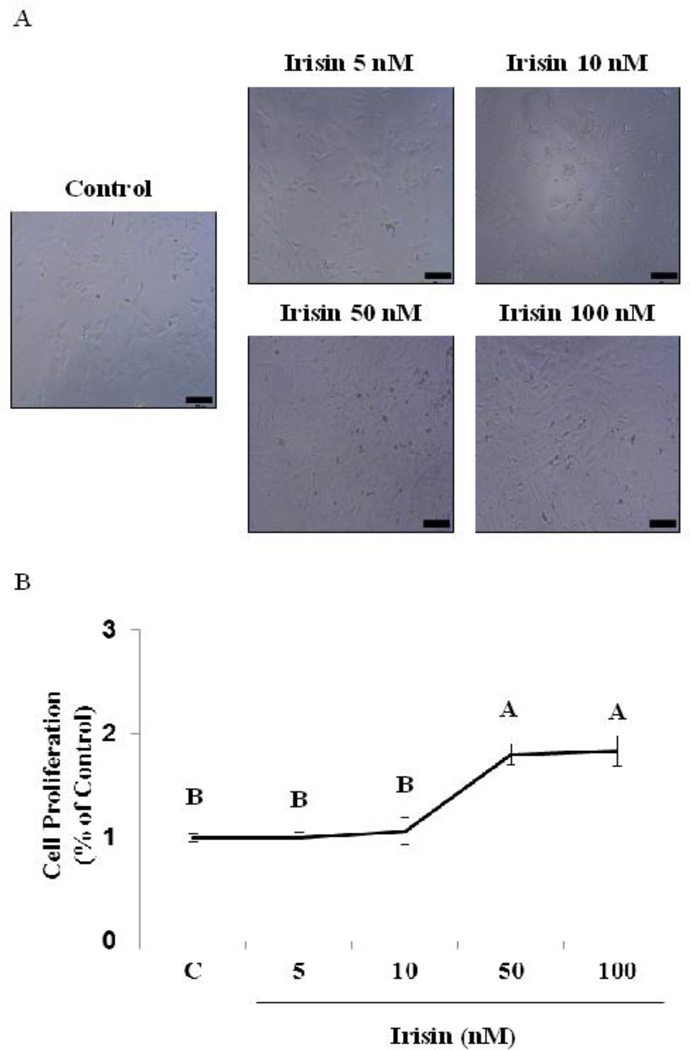

We observed using a phase contrast image that physiological concentrations of irisin, 5 to 10 nM, have no effect on cell proliferation when compared to control in mouse H19-7 HN cells (Fig. 1A). To confirm this, we performed a cell proliferation assay and observed that cell proliferation is not regulated by physiological concentrations of irisin (Fig. 1B). By contrast, we observed that treatment with irisin in pharmacological concentrations, 50 to 100 nM, increased cell proliferation by ~70–80 % when compared to control in mouse H19-7 HN cells (Fig. 1A and 1B).

Figure 1. Regulation of cell proliferation by irisin in mouse H19-7 HNcell lines.

The cells were cultured as described in detail in the “Methods”. (A) The cells were treated with irisin at indicated concentrations for 24 hr, and cells were then visualized by phase contrast image. Scale bar (200 nm, 10× magnification). (B) The cells were treated with irisin at indicated concentrations for 24 hr, and cell viability was then measured by MTT assay as described in detail in the “Methods” section. All data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by post-hoc test for multiple comparisons. Values are means (n=3) ± SD. Means with different letters are significantly different, p<0.05, whereas means with similar letters are not different from each other.

Regulation of STAT3, AMPK and ERK signaling pathway by irisin in mouse H19-7 HN cell lines

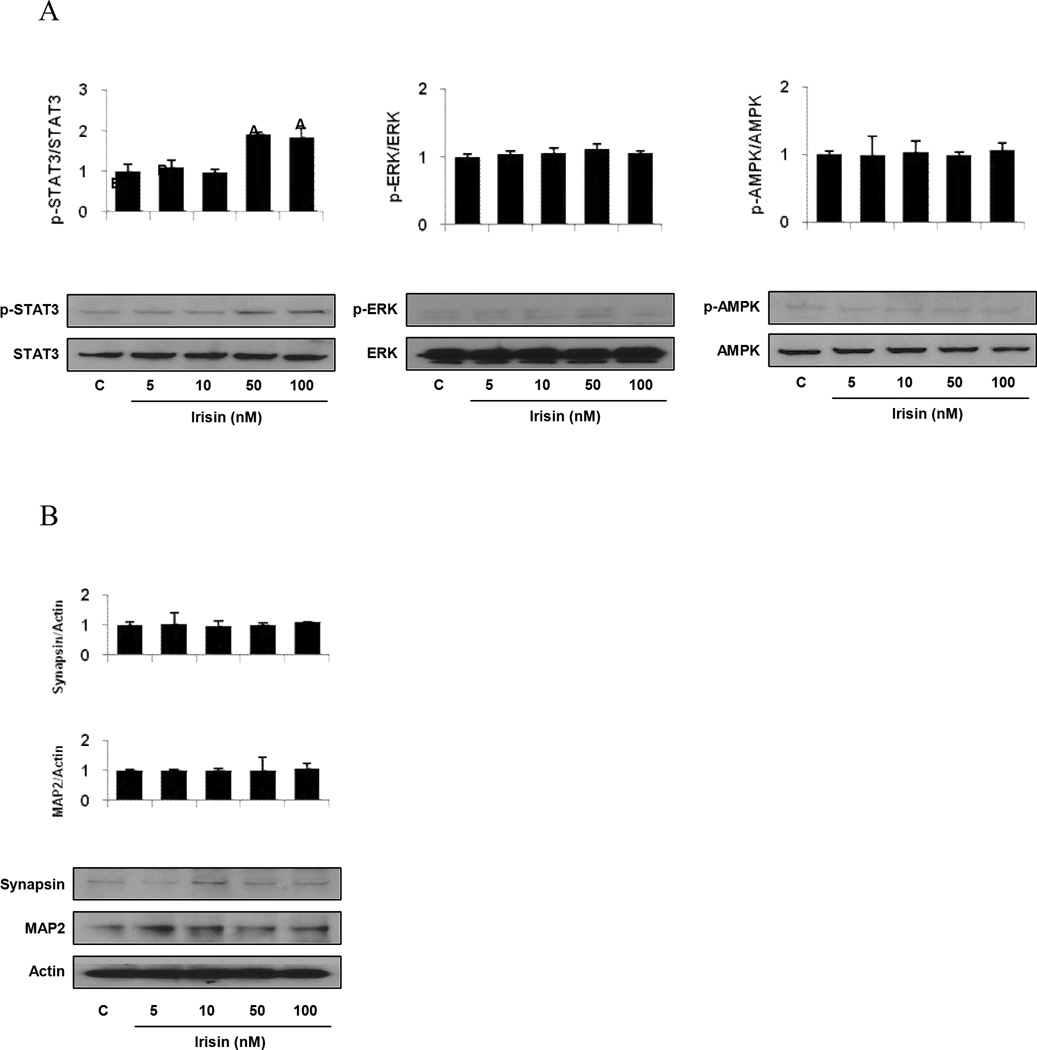

Similar to the above results regarding irisin’s effects on H19-7 HN cell proliferation, physiological concentrations of irisin, 5 to 10 nM, did not activate STAT3, AMPK, and/or ERK signaling when compared to control in mouse H19-7 HN cells (Fig. 2A). By contrast, treatment with irisin in pharmacological concentrations, 50 to 100 nM, increased STAT3, but not AMPK and/or ERK signaling pathway in H19-7 HN cells when compared to control (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2. Regulation of STAT3/AMPK/ ERK signaling and neuronal differentiation by irisin in mouse H19-7 HNcell lines.

The cells were cultured as described in detail in the “Methods”. (A) The cells were treated with irisin at indicated concentrations for 30 min, and Western Blotting was then performed as described in detail in the “Methods”. (B) The cells were treated with irisin at indicated concentrations for 5 days, and Western Blotting was then performed as described in detail in the “Methods”. All density values for each protein band of interest are expressed as a fold increase. All data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by post-hoc test for multiple comparisons. Values are means (n=3) ± SD. Means with different letters are significantly different, p<0.05, whereas means with similar letters are not different from each other.

Regulation of neurite outgrowth and synaptogenesis by irisin in mouse H19-7 HN cell lines

To determine whether irisin has a direct role in differentiation, cultured mouse H19-7 HN cell lines were incubated with irisin in a dose-dependent manner and MAP2, a specific neurite outgrowth marker; and Synapsin, a specific synaptogenesis marker, were measured. We observed that irisin has no dose-dependent effect on neurite outgrowth and synaptogenesis in H19-7 HN cells (Fig. 2B).

Discussion

The hippocampus plays an important role in brain function of both humans and other vertebrates (20–21) and is one of the first regions of the brain to suffer damage in the context of Alzheimer’s disease: memory problems and disorientation appear among the first symptoms (20–24). Also, it has been shown that decreased expression of FNDC5, the precursor of irisin, significantly reduces post-neural progenitor expression and reduces production of mature neuronal markers which modulated neuronal differentiation (18), which suggests that irisin may play an important role in neurogenic regulation. By contrast, the direct role of irisin in hippocampal neurogenesis has not yet been studied.

We have previously shown that STAT3/AMPK/ERK signaling is important for the maintenance of hippocampal development, which demonstrates that hippocampal neurogenesis, i.e., neurite outgrowth, and synaptogenesis are activated through STAT3/AMPK/ERK signaling pathways (19). Based on these findings, we explored whether irisin may activate STAT3/AMPK/ERK signaling in mouse HT19-7 HN cells. We observed that physiological concentrations of irisin have no effect on either cell proliferation or STAT3/AMPK/ERK signaling in mouse H19-7 HN cells. However, we did observe that pharmacological concentrations of irisin increase cell proliferation and STAT3 signaling, but not AMPK and/or ERK signaling. This suggests that pharmacological concentrations of irisin may increase cell proliferation primarily via the STAT3 signaling pathway in mouse H19-7 HN cells. Activation of STAT3 has been reported to be associated with stimulated hippocampal neurogenesis (25), and is required for the neurotrophic effects of ciliary neurotrophic factor and leukemia inhibitory factor on developing sensory neurons (26). Based on these prior reports, we proceeded to assess whether pharmacological concentrations of irisin may also increase neuronal development such as cell differentiation in mouse H19-7 HN cells. Similar to the above discussed results, we observed that physiological concentrations of irisin did not increase expression of either MAP2 or Synapsin in mouse H19-7 HN cells, which corroborates our data showing that irisin in physiological doses does not promote cell proliferation or affect STAT3/AMPK/ERK signaling in mouse H19-7 HN cells. Also, unlike our cell proliferation data, we observed that pharmacological concentrations of irisin have no effect on neuronal differentiation of mouse H19-7 HN cells.

Hashemi et al. has demonstrated that FNDC5 expression is required for the neural differentiation of mouse embryonic stem (ES) cells, suggesting the importance of FNDC5 in the generation and development of the nervous system (18). To date, it has not yet been elucidated whether FNDC5 and/or irisin itself may regulate mouse hippocampal neurogenesis. We demonstrate herein that pharmacological concentrations of irisin increase cell proliferation via STAT3, but not AMPK and/or ERK, signaling pathways, and have no effect on cell differentiation in mouse H19-7 HN cells. In addition to the signaling pathways activated by irisin demonstrated herein, there might be other yet to be reported signaling pathways activated by irisin and affecting proliferation, beyond STAT3, AMPK and/or ERK. This is the very first attempt to clarify the intracellular signaling pathways activated by irisin in mouse brain and/or hippocampal neurogenesis, and since there have been no prior studies on irisin signaling in brain cells, much more work focusing on CNS actions of irisin needs to be done in the future. Also, the irisin receptor has not yet been identified, and only very few papers have been published on the characterization and function of irisin in the brain. Hence, the discovery of the irisin receptor would be useful in determining whether irisin may act through the irisin receptor to affect mouse ES and/or hippocampal development.

Muscle-derived IL-6 causes alterations in excitatory and inhibitory synaptic formation and disrupts the balance of excitatory/inhibitory synaptic transmission (27–28). The shape, length and distributing pattern of dendritic spines are abnormally changed in response to IL-6 (27). IL-8 is also a muscle-secreted cytokine involved in angiogenesis, a process vital to tumor growth (29–30). IL-8 regulates migration of tumor-associated brain endothelial cells but not of normal brain endothelial cells (30). The mechanisms that directly link myokines with their apparent effects in the brain have not yet been elucidated. Hence, understanding the function and regulatory processes involved in cross-talk between myokines, including irisin, and the brain, especially hippocampus, needs to be studied further.

Both mental, such as skill learning, and physical training, such as aerobic exercise, enhance hippocampal neurogenesis (31). Also, both trainings increase cognitive performance, suggesting that a combination of mental and physical training is more beneficial for hippocampal development (31). Whether mental or physical training alone or in combination may increase irisin secretion and/or action in hippocampus has not yet been studied, and it is still unclear whether irisin may underlie the association between mental and/or physical training and hippocampal neurogenesis. Also, irisin signaling in the human hippocampus cannot be studied directly; techniques such as functional magnetic resonance imaging may be used in the future to study irisin’s actions in the human brain.

In conclusion, we present herein data showing that pharmacological concentrations of irisin promote H19-7 HN cell proliferation and activate STAT3 signaling, but do not affect neuronal differentiation in mouse H19-7 HN cells. Although we studied the signaling pathways that are considered to be primary targets of hippocampal cells, we did not look at all possible signaling pathways and therefore there might be other signalling pathways activated or de-activated by irisin in mouse hippocampal cells or other neural cells. Also, since the in vitro actions of irisin may differ between mice and humans, future work is needed to determine the regulation of irisin levels and its physiological effects on hippocampal neurogenesis such as learning and memory function in mice and humans.

Acknowledgements

The Mantzoros Laboratory was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases grants 58785, 79929 and 81913, and by Award Number 1I01CX000422-01A1 from the Clinical Science Research and Development Service of the VA Office of Research and Development.

Abbreviations

- AMPK

AMP-activated protein kinase

- ERK

Extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- HN

Hippocampal neuronal cells

- MAP2

Microtubule-associated protein 2

- STAT3

Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Duality of interest: The authors state that there is no duality of interest associated with this manuscript.

Contribution statement

HSM and CSM designed the study and analyzed and interpreted data. HSM, FD and CSM wrote, drafted and revised the article critically for important intellectual content. CSM conceived the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Pinto A, Di Raimondo DD, Tuttolomondo A, et al. Effects of physical exercise on inflammatory markers of atherosclerosis. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18:4326–4349. doi: 10.2174/138161212802481192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pederson BK, Febbrio MA. Muscles, exercise and obesity: skeletal muscle as a secretory organ. Nat Rev Endocrinology. 2012;8:457–465. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2012.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Febbraio MA, Hiscock N, Sacchetti M, et al. Interleukin-6 is a novel factor mediating glucose homeostasis during skeletal muscle contraction. Diabetes. 2004;53:1643–1648. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.7.1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsatsoulis A, Mantzaris MD, Bellou S, et al. Insulin resistance: An adaptive mechanism becomes maladaptive in the current environment - An evolutionary perspective. Metabolism. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2012.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bostrom P, Wu J, Jedrychowski MP, et al. A pgc1-alpha-dependent myokine that drives brown-fat-like development of white fat and thermogenesis. Nature. 2012;481:463–468. doi: 10.1038/nature10777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roberts MD, Bayless DS, Company JM, et al. Elevated skeletal muscle irisin precursor FNDC5 mRNA in obese OLETF rats. Metabolism. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2013.02.002. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Swick AG, Orena S, O’Connor A. Irisin Levels Correlate with Energy Expenditure in a Subgroup of Humans with Energy Expenditure Greater than Predicted by Fat Free Mass. Metabolism. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2013.02.012. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kelly DP. Medicine, Irisin, light my fire. Science. 2012;336:42–43. doi: 10.1126/science.1221688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu J, Boström P, Sparks LM, et al. Beige adipocytes are a distinct type of thermogenic fat cell in mouse and human. Cell. 2012;150:366–376. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Timmons JA, Baar K, Davidsen PK, et al. Is irisin a human exercise gene? Nature. 2012;488:E9–E10. doi: 10.1038/nature11364. [discussion E-1] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lecker SH, Zavin A, Cao P, et al. Expression of the irisin precursor FNDC5 in skeletal muscle correlates with aerobic exercise performance in patients with heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2012;5:812–818. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.112.969543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duman RS, Malberg J, Nakagawa S. Regulation of adult neurogenesis by psychotropic drugs and stress. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;299:401–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gould E, Tanapat P, McEwen BS, et al. Proliferation of granule cell precursors in the dentate gyrus of adult monkeys is diminished by stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:3168–3171. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McEwen BS. Stress and hippocampal plasticity. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1999;22:105–122. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.22.1.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duman RS, Nakagawa S, Malberg J. Regulation of adult neurogenesis by antidepressant treatment. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;25:836–844. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00358-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacobs BL. Adult brain neurogenesis and depression. Brain Behav Immun. 2002;16:602–609. doi: 10.1016/s0889-1591(02)00015-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huh JY, Panagiotou G, Mougios V, et al. FNDC5 and irisin in humans: I. Predictors of circulating concentrations in serum and plasma and II. mRNA expression and circulating concentrations in response to weight loss and exercise. Metabolism. 2012;61:1725–1738. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hashemi MS, Ghaedi K, Salamian A, et al. Fndc5 knockdown significantly decreased neural differentiation rate of mouse embryonic stem cells. Neuroscience. 2012;231C:296–304. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moon HS, Dincer F, Mantzoros CS. Amylin-induced downregulation of hippocampal neurogenesis is attenuated by leptin in a STAT3/AMPK/ERK-dependent manner in mice. Diabetologia. 2013;56:627–634. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2799-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.May PC, Boggs LN, Fuson KS. Neurotoxicity of human amylin in rat primary hippocampal cultures: similarity to Alzheimer's disease amyloid-beta neurotoxicity. J Neurochem. 1993;61:2330–2333. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb07480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anan F, Masaki T, Shimomura, et al. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein is associated with hippocampus volume in nondementia patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Metabolism. 2011;60:460–466. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee EB. Obesity, leptin, and Alzheimer's disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011;1243:15–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06274.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vanitallie TB. Preclinical sporadic Alzheimer's disease: target for personalized diagnosis and preventive intervention. Metabolism. 2013;62(Suppl 1):S30–S33. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2012.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wurtman RJ. Personalized medicine strategies for managing patients with parkinsonism and cognitive deficits. Metabolism. 2013;62(Suppl 1):S27–S29. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2012.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jung KH, Chu K, Lee ST, et al. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor stimulates neurogenesis via vascular endothelial growth factor with STAT activation. Brain Res. 2006:1073–1074. 190–201. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alonzi T, Middleton G, Wyatt S, et al. Role of STAT3 and PI 3-kinase/Akt in mediating the survival actions of cytokines on sensory neurons. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2001;18:270–282. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2001.1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wei H, Chadman KK, McCloskey DP, et al. Brain IL-6 elevation causes neuronal circuitry imbalances and mediates autism-like behaviors. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1822:831–842. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2012.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weiss TW, Arnesen H. Seljeflot I Components of the Interleukin-6 transsignalling system are associated with the metabolic syndrome, endothelial dysfunction and arterial stiffness. Metabolism. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2013.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Charalambous C, Pen LB, Su YS, et al. Interleukin-8 differentially regulates migration of tumor-associated and normal human brain endothelial cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:10347–10354. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dwyer J, Hebda JK, Le Guelte A, et al. Glioblastoma cell-secreted interleukin-8 induces brain endothelial cell permeability via CXCR2. PLoS One. 2012;7:e45562. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Curlik DM, Shors TJ. Training your brain: Do mental and physical (MAP) training enhance cognition through the process of neurogenesis in the hippocampus? Neuropharmacology. 2013;64:506–514. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]