Abstract

We focused on the application of antidepressants in schizophrenia treatment in this review. Augmentation of antidepressants with antipsychotics is a common clinical practice to treat resistant symptoms in schizophrenia, including depressive symptoms, negative symptoms, comorbid obsessive–compulsive symptoms, and other psychotic manifestations. However, recent systematic review of the clinical effects of antidepressants is lacking. In this review, we have selected and summarized current literature on the use of antidepressants in patients with schizophrenia; the patterns of use and effectiveness, as well as risks and drug–drug interactions of this clinical practice are discussed in detail, with particular emphasis on the treatment of depressive symptoms in schizophrenia.

Keywords: depressive symptoms, drug-drug interaction, antipsychotics

Introduction

Depression is common in schizophrenia.1–4 The prevalence of depressive symptoms in patients with schizophrenia varies from 10% to 75% in different studies;5–8 the average is estimated to be about 25%.1,9 The variation is probably caused by the heterogeneity and differences in study subjects, diagnosis criteria, research methods, phases of psychosis, medication intervals, and other factors. However, most of the psychiatrists consider depression as a common problem throughout the course of schizophrenia;10 several studies showed about 60% of patients with schizophrenia meet Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, third edition, criteria for major or minor depression.11,12 Depressive symptoms are found most frequently during an acute psychotic episode,13 whereas post-psychotic depression, where depressive symptoms start off after an acute psychotic episode, were reported to occur in an average of 25% of treated schizophrenic patients.14 The first psychotic break is often associated with a higher prevalence of depression occurrence. Almost half of the first-episode schizophrenic patients show clinical symptoms of major depression (SMD) according to diagnostic criteria Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D), and in relapsed chronic schizophrenic group, there are about one third of patients showing SMD.7,15 For those schizophrenic patients who do not have major depression episodes, at least two thirds of them show mild depressive symptoms, and over 30% of them have minor depressive mood or feelings.16 Depressive symptoms are more common in patients with active psychosis. In an early comparison study, clinically significant depression among patients with schizophrenia, as defined by a Hamilton Depression score of 17 or greater, was diagnosed in a higher proportion of the inpatient group (10%) than of the outpatients (4.5%), while the prevalence of mild-to-moderate depression, as defined by a Hamilton Depression score of between 10 and 17, was unexpectedly diagnosed in similar proportions of the inpatient group (42%) and of the outpatient group (47%).17 As an extreme unfavorable outcome, depression increases the risk of suicide, the rate of which in schizophrenic patients is reported to be approximately 10%.16,18,19

Some of the depressive symptoms can be found 5–10 years prior to the first psychotic episode; they occur frequently during the course of deterioration into psychosis. Häfner et al20 have shown a prevalence of 81% in schizophrenic patients who had depressive mood prior to their first psychotic break. More recent studies that have systematically examined the underlying factors and early signs of schizophrenia also suggested that mild depressive symptoms are strongly associated with the onset of schizophrenia.21,22 In the course of schizophrenia, hallucinations, as one of the manifestations of psychosis, can be particularly troublesome and may lead to depression or even suicide. Auditory hallucinations in patients with schizophrenia can be very distressing and possibly encourage and reinforce depressive symptoms.23 Depression has also been characterized as a response to the severity of psychotic problems or subjective awareness of the condition itself.24,25 In post-psychotic phase, depression in schizophrenia has also been noticed and the prevalence has been reported from 25% up to 40%. While in post-psychotic cases, depression has not been proven to be a precursor to the onset of the next relapse, or to be related to the prepsychotic depression; the post-psychotic depression seems independent of positive symptoms as well as negative symptoms.26,27

Depressive symptoms are often more frequent and severe in schizophrenic patients, compared to normal subjects.10,16 Vice versa, patients with persistent depressive symptoms during the chronic phase of schizophrenia have a higher risk for relapses in comparison with nondepressed subjects.28 Depression is significantly related to a decrease in everyday functioning in patients with schizophrenia,29 and it is known to increase the risk of suicide in patients with schizophrenia.16,18,19

The diagnosis of depression in schizophrenia can be quite complex. As described by Zisook et al10 the most prevalent symptoms of depression include psychological (eg, lowered mood, depressed appearance, and anxiety), cognitive (eg, guilt, hopelessness, lowered self-esteem, and loss of insight), somatic (eg, sleep, appetite disturbance, reduction of energy, and somatic anxiety), psychomotor (eg, retardation and agitation), and functional (reduced activities and concentration).30 The diagnosis involves not only identifying those symptoms of depression but also distinguishing them from negative symptoms and stress disorders, such as cognitive impairment, social withdrawal, and affective flattening.31,32 Situational disappointment is another difficult case to be recognized from depression. The way to differentiate depression from these depression-like symptoms is to carefully observe the patients for a certain period of time and/or to apply psychosocial interventions; the real depressive symptoms would be more persistent, showing a prominent low mood, sense of guilt, and even suicidal thoughts.8

There is clinical confusion regarding whether depressive symptoms are core to the psychosis of schizophrenia, or side effects induced by antipsychotics. It is known that antipsychotics are dopamine antagonits, and dopamine plays an important role in the “reward” pathway, which is largely involved in experiences of “pleasure”. Blocking dopaminergic activities might lead to dysphoria and depression-like symptoms, such as akinesia, Parkinsonism, akathisia, cognitive despair, and negative symptoms (which can be easily misinterpreted as depressive symptoms). Although the clinical data has not shown differences between patients treated with antipsychotics and those randomized to placebo in terms of adverse effects, it is still suggested to rule out Parkinsonian symptoms or dysphoria that could be induced by inappropriate psychotic medication first, before prescribing antidepressants to patients with schizophrenia.7,9,33 Substance abuse and alcoholism can also cause depression;34 depressed patients should therefore always have a thorough medical evaluation.

Among all the depression assessment instruments, Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia (CDSS), designed specifically for the patients with schizophrenia, can most accurately identify depression in the case when there are natural negative symptoms or side effects of antipsychotics confounding the occurrence of depression.35 CDSS is therefore recommended as the preferred assessment scale.2 Whereas the HAM-D – the most commonly used rating scale to assess depression – was initially developed for use in depressive disorders, HAM-D may not discriminate depressive symptoms from negative and extrapyramidal symptoms. Systematic comparison studies have shown that HAM-D accounts more for the positive and negative symptom domains than CDSS in schizophrenia.36,37 Other instruments to measure depressive symptoms used in schizophrenic patients include Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale – Depression subscale, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale – Depression subscale, Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale, and Raskin Depression Rating Scale (RDRS). A recent review of the available depression assessment instruments also recommends CDSS for depressive symptoms in patients with schizophrenia, since CDSS measures nearly no symptoms other than depressive symptoms, and the criteria in the measurement do not overlap with negative and extrapyramidal symptoms.38 In addition, CDSS has been translated into different languages and evaluated in different regions and areas,39–44 which would be helpful for its further adaptation.

Treatments for depression in schizophrenia mainly focus on addressing the underlying factors of depressive symptoms, including medications and psychosocial treatments. There are guidelines for treating depressive symptoms in schizophrenia in different countries of the world with similar principles.45–47 Generally, first of all, underlying problems such as medications’ side effects or substance abuse should be carefully identified. Medications can be adjusted to the differential diagnosis, such as antipsychotic dose reduction or substitution of an atypical antipsychotic for antipsychotic-induced depression, or a supplemental (anticholinergic) anti Parkinsonian agent for akinesia. If the depressive symptoms are intrinsic to acute psychotic episode, an appropriate antipsychotic medication (maybe atypical antipsychotics) that resolves the symptoms of psychosis could facilitate the depression by itself, with no need for antidepressants. In the case of acute schizoaffective disorder, combination of an antipsychotic and an antidepressant or lithium or with electroconvulsive therapy (in case of life-threatening symptoms) could be helpful; in stable chronic psychotic phase, when anti Parkinsonian agents do not have any therapeutic effect, persistent depression may respond to antidepressant augmentation of antipsychotics.9,48 However, since the studies of antidepressant augmentation are hard to be standardized, the reported results from different randomized controlled clinical trials are quite confusing or even conflicting.49,50

At the same time as pharmacological treatment, supportive psychotherapy, family involvement, and social support should be considered for persistent depressive symptoms and for medication maintenance.9,48 Psychoeducation is the most frequently used psychotherapeutic approach followed by family interventions; psychoeducation it mostly provides education about the disorder, symptoms that patients may experience, and the importance of staying on medication.15 Reviews of psychoeducational treatments in schizophrenia and depression suggested that psychoeducational interventions are effective in improving the clinical course, treatment adherence, and psychosocial functioning.51,52 Another therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), became more recommended in 2002. CBT focuses on thinking and behavior; it helps patients to manage their symptoms overall. Despite the fact that no significant advantage has been found for CBT as compared to other psychotherapies, it may help reduce the severity of depressive symptoms and reduce the risk of relapse in the long term.53,54

In this review, we are particularly interested in the role of antidepressants in treating depressive symptoms in schizophrenia. The patterns of use, effectiveness, adverse effects and drug–drug interactions of antidepressants will be further discussed in detail.

Patterns of antidepressant usage in schizophrenia treatment

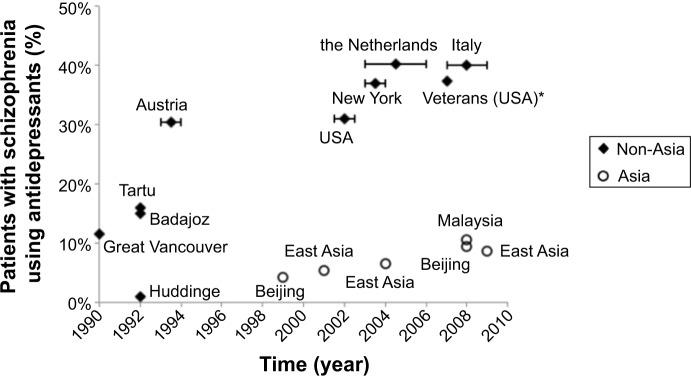

Prescribing antidepressant to patients with schizophrenia is not uncommon. The reported rates of antidepressant prescription to schizophrenic patients vary greatly under different circumstances, and in different geographic regions. In Table 1, we have summarized the studies of antidepressant description from different regions and areas of the world. Only two of these studies have further investigated the effect of antidepressants on the depressive symptoms; the results suggested that concomitant use of antidepressants is not completely successful,55,56 and no side effect was reported or a concern in these studies.

Table 1.

Patterns of antidepressant prescription in schizophrenia treatment

| Study year | Region | Sample size | Female (%) | Age (years) | Antidepressants | Patients using antidepressant (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Asia | |||||||

| 2007–2009 | Italy | 892a | 58.0 | 55±17 | SSRI 55%; TCA 2.8% | 40b | 62 |

| 2007 | USA (Veterans)* | 2,412 | 7.6 | 54 | SSRI/SNRI 84.5%; TCA 22.9% | 37.4 | 63 |

| 2003–2006 | the Netherlands | 214 | 43.0 | 38.7±11.7 | na | 40.2 | 56 |

| 2003–2004 | New York, USA | 456 | 35 | 43±11.7 | SSRI; TCA; others | 37 | 65 |

| 2001–2003 | USA | 1,380 | 30 | 40±11 | na | 31% total | 55 |

| 1993/1994 | Austria | 177 | 59.2 | 48.4 | na | 30.4 | 128 |

| 1992 | Badajoz, Spain | 100 | 50 | 37.8±12.5 | na | 15 | 129 |

| Huddinge, Sweden | 87 | 46 | 37.1±10.2 | na | 1 | ||

| Tartu, Estonia | 100 | 50 | 38.8±12.6 | Mainly amitriptyline | 16 | ||

| 1990 | Greater Vancouver, Canada | 1,421 | na | 44.7±14.0 | Mostly TCA | 11.60 | 67 |

| Asia | |||||||

| 2009 | People’s Republic of China, Hong Kong, Japan, Korea, Singapore, Taiwan, India, Malaysia, and Thailand | 2,226 | 39.4 | 43.0±13.7 | Mainly SSRI >55.9% | 8.70 | 66 |

| 2008 | Malaysia | 200 | 34 | 35.0±1.1 | na | 10.5 | 130 |

| 2008 | Beijing, Republic of China | 518 | 46.5 | 42.0±15.8 | na | 9.5 | 131 |

| 2004 | People’s Republic of China, Hong Kong, Japan, Korea, Singapore, and Taiwan | 2,136 | 42.7 | 43.1±14.2 | Mainly SSRI >50.3%; trazodone >27.3% | 6.5 | 66 |

| 2001 | People’s Republic of China, Hong Kong, Japan, Korea, Singapore, and Taiwan | 2,399 | 44.1 | 43.6±13.5 | Mainly SSRI >43% | 5.3 | 66 |

| 1999 | Beijing, People’s Republic of China | 605 | 44.5 | 41.2±12.8 | na | 4.30 | 131 |

Notes:

564 taking antipsychotics; 295 schizophrenic patients.

Presented in 564 patients taking antipsychotics.

This data was taken from US Veterans only, and not the general population of the US.

Abbreviations: SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; TCA, tricyclic antidepressant; SNRI, serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors; na, not applicable.

It is not surprising to find that the rate of antidepressant prescriptions for patients with schizophrenia has risen over time. In Western countries, it was about 15% in the 1990s and has increased to 40% in the last decade. In 1998, a schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT), which was funded by the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research and the National Institute of Mental Health funded in the USA, has developed a set of recommendations for the treatment of schizophrenia based on existing scientific evidence.57 In 2004, a second edition was published that gave more detailed recommendations for the use of antidepressants to treat major depression in schizophrenia, including the usage in acute or stable phases of illness, the usage in elderly patients, and precautions against the risks of drug–drug interactions with antipsychotics.58 This guideline has been followed by a large number of psychiatrists; 48.3% of inpatients met at least one of the comorbid depression criteria, and of them, 33.8% were prescribed an antidepressant; among the outpatients, 42.8% met the depression criteria, and 45.7% of them were prescribed an antidepressant.59,60 This probably resulted in the increased rate of prescribing antidepressants in most Western countries. However, in the update in 2009 Schizophrenia PORT, the recommendations for the use of antidepressants to treat major depression in schizophrenia were dropped, due to the lack of sufficient evidence to support the efficiency of antidepressants on depressive symptoms in patients with schizophrenia.61

In the early reports, tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) were the most often used antidepressants; however, in the recent studies, the most prescribed antidepressants were newer generation, serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (Table 1). Antidepressants are generally used as concomitant medication with antipsychotics in patients with schizophrenia. The combination of a second-generation or atypical antipsychotic agent with an SSRI has been reported the most popular choice among psychiatrists worldwide.15 Their prescription dose is almost always within the limits indicated by the technical sheets but consistently above those indicated by the daily-defined doses.62 During the therapy, some patients would have the dose of their antidepressants changed, such as citalopram was frequently up-titrated; the medication might not be fully efficacious on the depressive symptoms in these cases.62 It is generally agreed in the USA that the antidepressant medication requires 4±2 weeks to show its clinical benefits, and once initiated, it should be continued for 6–12 months if the patients respond well.15 The ineffectiveness of antidepressant treatment has also been noted in other studies;55,56 compared to the patients without adjunctive treatment, the patients using antidepressants did not always show a better chance in remitting from their depressive symptoms.

Among the patients with schizophrenia, those who are 1) diagnosed with depression,55 2) having resistant negative symptoms,63 3) female,55,62 and 4) treated with second-generation antipsychotics62,64 are more likely to receive antidepressants. Cost of medication and insurance coverage of psychological disorders also influence the rate of prescription for adjunctive antidepressants. A couple of studies showed that racial difference is also associated with the proportion of antidepressant prescription; black population use less frequently prescribed antidepressants; it may reflect economic factors, less engagement in the mental health system, or undertreatment.55,65 A similar situation is found in patients with a record of homelessness.63

Very interestingly, we found that the use of antidepressants in concomitant treatment for schizophrenia in Asian countries is generally much lower than that in Western countries. Despite an increase in antidepressant use over time in the rest of the world, the average rate of prescription of antidepressants among patients with schizophrenia was still barely >10% (Table 1, Figure 1). As shown by Xiang et al66 patients with schizophrenia in Singapore received the highest rate of adjunctive antidepressant medication, which was 22.0% in 2009. The low rate of antidepressant use in Asia may be due in part to the concern for worsening positive symptoms. The patterns of antidepressants prescription in Asia also revealed an association between younger age and increased antidepressant usage. It might be explained by the belief that the risk of adverse effects of psychotropic drugs increases with age.67

Figure 1.

Patterns of antidepressant prescription in schizophrenia treatment.

Note: *This data was taken from US Veterans only, and not the general population of the US.

Benefits and risks of antidepressants for patients with schizophrenia

For clinical applications of antidepressants, the core question is whether the benefits associated with the medications outweigh their health risks in treating depressive symptoms in patients with schizophrenia.

Effectiveness on depression in patients with schizophrenia

In order to provide a global overview of the effects of antidepressants on the depressive symptoms in patients with schizophrenia, a thorough search was conducted on PubMed of articles published before January 2014. The terms “antidepressants” or “antidepressive agents” were combined with “schizophrenia” or “schizoaffective disorders” and “combination” or “augmentation” or “add-on” or “addition”, as well as “double blind” and “placebo controlled”. Results from 18 different double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials of adjunctive antidepressants were selected in this review (Table 2). All of these trials have measured depression as a primary or secondary outcome with standard clinical scales, including HAM-D, RDRS, CDSS, and Beck Depression Inventory, which had to be completed by patients. The other related information about these trials was also clearly presented. In these trials, the patients with schizophrenia were mostly at a chronic but stable phase of psychosis; they showed various states of post-psychotic depression according to the measures. Most clinical trials choose to target post-psychotic depression because 1) the depressive symptoms presented in acute phase of psychosis could be associated with antipsychotic-induced dysphoria, akinesia, negative symptoms, or disappointment reactions, which are possibly ameliorated once the dose of antipsychotics is correctly reduced or anti Parkinsonian and/or anticholinergic medication is used;9 and 2) adjunctive antidepressants could produce significant beneficial effects for patients not associated with acute psychotic illness.68 Some of the patients in trials were taking anticholinergic or anti Parkinsonian medications to reduce the side effects of antipsychotics.

Table 2.

Double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials of antidepressants for treating depressive symptoms in patients with schizophrenia

| Antidepressants | Type of antidepressant | Antipsychotics | Duration | Size | Female (%) | Age (years) | Depression | Effect on depression | Effect on negative symptoms and other effects | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amitriptyline | TCA | FGA | 4 months | 35 | na | na | na | Significant improvement, superior to placebo | na | 70 |

| Amitriptyline, desipramine | TCA | FGA | 4 weeks | 58 | na | na | HAM-D>I7 | No significant difference compared to placebo | na | 86 |

| Imipramine | TCA | FGA | 4 weeks | 52 | 32.7 | 38 | HAM-D 3/4 or anergic 3/4 | No significant difference compared to placebo | na | 132 |

| Impiramine | TCA | FGA | 6 weeks | na | na | na | Post-psychotic | Significant improvement, superior to placebo | AD showed a better global improvement and no significant effect on psychosis or side effects | 133 |

| Fluvoxamine | SSRI | FGA | 6 weeks | 30 | 37 | 41.5 | HAM-D 7.7±4.9 | Depressive features showed significant improvement with time but no significant difference between active and placebo | na | 134 |

| Fluvoxamine | SSRI | FGA | 8 weeks | 32 | 28.10 | 36.6 | HAM-D 12.4±8.6 | No significant difference compared to placebo | na | 135 |

| Fluvoxamine | SSRI | na | 12 weeks | 34 | na | na | na | Slight but significant improvement, superior to placebo | AD showed significant improvement in negative symptoms. Side effects were more common in AD group | 136 |

| Fluoxetine | SSRI | SGA | 8 weeks | 33 | na | na | na | No significant difference compared to placebo | No significant differences in positive, negative, depressive, or obsessive–compulsive symptoms | |

| Sertraline | SSRI | FGA | 8 weeks | 26 | 38.50 | 38 | BPRS ≥3 and BDI ≥ 15 | Significant improvement in the anxiety/depression, superior to placebo | No significant effect on negative or positive symptoms. Sertraline was well tolerated | 88 |

| Sertraline | SSRI | SGA 58.3% | 6 weeks | 48 | 63.50% | 37.8 | CDSS 14.0±1.28; HAM-D 20.6 | Both groups showed improvement in depression, but no significant difference compared to placebo | na | 87 |

| Citalopram | SSRI | SGA ~90% | 12 weeks | 198 | 21.80 | 52.4 | HAM-D ≥8 | Significant improvement, superior to placebo | Significant improvement in negative symptoms, superior to placebo. No differences in positive symptoms, general medical health or other side effects | 72 |

| Escitalopram | SSRI | SGA 79% | 10 weeks | 38 | 28 | 37.2 | HAM-D 6.6±4.9 | No significant difference compared to placebo | No significant difference compared to placebo | 137 |

| Trazodone | SARI | FGA | 6 weeks | 60 | 43.30 | 43 | HAM-D > 18 | Significant improvement, superior to placebo | AD was well tolerated, minimal side effects | 138 |

| Bupropion | Atypical | FGA | 10 weeks | 38 | 36.80 | 41 | HAM-D > 18 | No significant difference compared to placebo | 139 | |

| Mirtazapine | NaSSA | FGA | 6 weeks | 39 | na | 18–65 | CDSS 4.58±5.08 | Significant improvement, superior to placebo | The changes in the CDSS correlated positively with those in the PANSS negative, positive, and total (sub) scales in AD group | 89 |

| Mirtazapine | NaSSA | SGA | 6 weeks | 40 | 15 | 36.8 | HAM-D 12.28±6.31; CDSS 5.44±4.49 | No significant difference compared to placebo | No significant difference compared to placebo | 140 |

| Viloxazine | NRI | FGA | 4 weeks | 28 | na | 19–53 | HAM-D > 18 | No significant difference compared to placebo | na | 141 |

| Reboxetine | NRI | FGA | 6 weeks | 30 | 6.70 | 32.4 | Endpoint HAM-D 6.93±4.16 | No significant difference compared to placebo | No overall difference between the two groups | 142 |

Note: The gray shading highlights those that did not indicate any positive result.

Abbreviations: TCA, tricyclic antidepressant; FGA, first generation antipsychotics; HAM-D, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; AD, antidepressant; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; SGA, second generation antipsychotics; BPRS, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; CDSS, Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia; SARI, serotonin antagonist and reuptake inhibitor; NaSSA, noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressant; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; NRI, norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor; na, not applicable.

As early as 1978, Siris et al found that the combination of antidepressants, such as TCAs, and antipsychotics improved the symptoms of clinical depression in some patients with schizophrenia.69 This finding was confirmed by another double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial.70 Siris et al have also shown that maintenance adjunctive antidepressant therapy for depressed patients with schizophrenia could help to avoid a relapse of depression and protect patients from worsening psychosis.71

Other antidepressants such as serotonin antagonist and reuptake inhibitor (SARI) and SSRIs could significantly improve depressive symptoms too, and with less adverse effects than TCAs. A systematic study of citalopram augmentation72 in schizophrenia treatment has shown a significant effect by improving depressive and negative symptoms. In meta-analysis of the efficiency of antidepressants, in treating schizophrenia, it has been shown that the use of antidepressants as an add-on therapy to antipsychotics moderately yet significantly improved the negative symptoms in chronic schizophrenic patients;73–75 the same effect was also observed for an acute exacerbation of schizophrenia.76 The results favored in particular newer antidepressants, including SSRI (fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, citalopram), SARI (trazodone), and serotonin 5-HT2C antagonist (ritanserin).

Another most commonly prescribed antidepressant, bupropion, serves as a non-TCA and is fundamentally different from SSRIs. From a pharmacological standpoint, bupropion primarily acts as a mild reuptake inhibitor of dopamine and norepinephrine, as well as a nicotinic acetylcholine receptor antagonist; however, its mechanisms of action are not fully understood.77,78 Bupropion has been shown to be an effective antidepressant and to be well tolerated,79 even compared to SSRIs.80,81 A recent systematic review of the use of bupropion in schizophrenia has suggested its favorable effectiveness in alleviating depressive symptoms.82

Noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressants (NaSSAs), such as mirtazapine and mianserin, are classified as tetracyclic antidepressants based on their chemical structures. Because of their specific antagonism of certain serotonin receptors, which reduces many side effects associated with SSRIs, NaSSAs can be well tolerated. A very recent meta-analysis of NaSSAs augmentation therapy in schizophrenia treatment has also suggested their beneficial effects on akathisia and extrapyramidal symptoms.83 But there was little evidence to support any significant effect of NaSSAs on the depressive symptoms in schizophrenia.83

Finally, norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (NRIs), such as reboxetine, have been recently developed. The clinical investigations of NRIs lead to a better understanding of the role of noradrenergic system in different aspects of depression. The use of reboxetine has been shown to be an effective approach to alleviate depressive symptoms;84 however, compared to other serotoninergic antidepressants, reboxetine is much less efficacious.85 From the collected trials, effectiveness of antidepressants on depressive symptoms is rather mixed; seven out of 18 studies demonstrated a significant effect of antidepressants in patients with schizophrenia, while the others did not indicate any positive result (marked with shading in Table 2). Even the same compounds in different trials have produced different results (Table 2). Apart from varying quality in the literature, the conflicting data could be due to methodological problems, small study sample size, different antipsychotics used by the patients or insufficient doses, and/or duration of antidepressant treatment. For example, amitriptyline was found to be effective for patients with chronic psychosis after 4 months of treatment,70 but did not show significant therapeutic advantage after 4 weeks.86 In the case of sertraline, different rating scales of depression were applied in the two cited studies.87,88 Slightly longer treatment might also favor the effectiveness of antidepressant. Use of different classes of antipsychotics might also influence the outcome; the augmentation with mirtazapine to first-generation or typical antipsychotics unexpectedly demonstrated better effectiveness on depressive symptoms, as well as positive and negative symptoms compared to the combination with second-generation antipsychotics.89 This comparison definitely needs to be further investigated in well-designed clinical trials. Due to the heterogeneity of these trials, they were not included in the meta-analysis. As a reference, a similar conflict of the effect of antidepressants was found in a meta-analysis carried out by Whitehead et al in 2002;90 the analysis has shown that using antidepressants was slightly beneficial for people with depression and schizophrenia, supported with conditionally significant evidence. In conclusion, 1) there is an urgent need for well-designed, conducted, and described clinical research on the use of antidepressants in schizophrenia; and 2) from the existing data and analysis, augmentation of psychotics with antidepressants may have a moderate chance to improve post-psychotic depressive symptoms in schizophrenic patients.

Here we have to keep in mind that there are some studies that showed no significant difference in depression rating scales between antidepressant and placebo groups,7,86,91 although an ineffective result of antidepressants was possibly due to a significant placebo effect (50%) and small patient sample size of trials.87 The studies also demonstrated that administration of antidepressants produced little effect on negative symptoms, such as low energy levels and social withdrawal. In clinical practice, there is a good chance that “depressed” patients with schizophrenia will respond poorly to antidepressant augmentation.

Comorbid obsessive–compulsive symptoms treatment

Comorbid obsessive–compulsive symptoms (OCS) occur in about 25% of schizophrenic patients,92,93 which is much higher than the prevalence rate for obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) in the general population (2%–3%). Despite many advantages – excellent antipsychotic effects – in treating resistant schizophrenia, second-generation antipsychotics, such as clozapine, are believed to be implicated in the de novo emergence of OCS in patients with schizophrenia.94,95 Both onset and severity of OCS are closely correlated with clozapine treatment.96,97 It was strongly suggested that the serotoninergic antagonism of second-generation antipsychotics, which results in an imbalance between serotoninergic and dopaminergic system, contributes to this side effect;98 alteration or dysfunction of glutamatergic and dopaminergic neurotransmission might also be involved.99,100 Patients with comorbid OCS in schizophrenia are generally suffering from more neurocognitive impairment, more severe psychosis, and treatment resistance.101,102

Pharmacological interventions seem recommendable to improve comorbid OCS.103 Beneficial effects with antidepressants augmentation have been reported, including TCA clomipramine104 and newer generation antidepressants SSRIs, such as fluvoxamine.105 Note that there were few case studies showing an insignificant effect of antidepressant augmentation.106 CBT was also reported useful.107,108 Further research with larger sample sizes and well-designed controlled clinical trials would be helpful to verify the improvement effect with antidepressants and behavioral therapy for treating comorbid OCS in schizophrenia.

Adverse effects

Many side effects of TCAs are related to their anticholinergic properties, such as constipation, urinary retention, delirium, and cognitive dysfunction; these are relatively common and can happen more frequently among older patients. Other side effects include antihistaminergic effects such as sedation, and antiadrenergic effects such as postural hypotension. TCAs could also worsen the sedative and anticholinergic side effects of antipsychotics, although they might be helpful for extrapyramidal symptoms. Overdose of TCAs can be fatal; it is a serious problem in the pediatric population due to their inherent toxicity.

In comparison, serotonin reuptake inhibitors, the antidepressants often used in combination with antipsychotic to treat depression in schizophrenia, have less effect on cholinergic, histaminergic, and adrenergic systems. They are better tolerated and relatively safe even in overdose situations. Serotonin reuptake inhibitors are associated with reductions in impulsivity, irritability, aggression, paranoia, and other behavioral disturbances.109,110 The most common complaints of these newer antidepressants, in particular fluvoxamine, are nausea, changes in appetite, and sexual dysfunction.111 The combination of SSRI with atypical antipsychotics is generally safer than the combination of TCAs with typical antipsychotics.

Augmenting antipsychotics with antidepressants is suspected to aggravate the psychotic symptoms, like delusions and hallucinations,86,91 through increasing blood concentration of antipsychotics induced by competitive metabolism inhibition, which will be further discussed in the next section. Concomitant treatment can also increase risk of arrhythmias. Additionally, side-effect profiles shared by both antipsychotic and antidepressant agents, such as weight gain and sedation, could be potentially additive.63 However, from the results of clinical trials, the chance of these unwanted effects is low, in particular in patients who are at a stable chronic phase of illness.112 In any case, more attention should be paid when antipsychotics, clozapine in particular, are augmented with antidepressants.113 Another possible adverse side effect of the combination is the anticholinergic activity; the increased concentration of TCAs can lead to increases in risk or severity of anticholinergic side effects, such as blurred vision, dry mouth, constipation, or urinary retention.

Drug interaction with antipsychotics

As with all adjunctive medications, one of the biggest concerns regarding antidepressants in clinical practice is drug interactions. For patients with schizophrenia, an antidepressant is always combined with an antipsychotic. Antidepressants are extensively metabolized in the liver through oxidative reactions; the combination could produce competitive metabolism inhibition. It has been shown that using a TCA at the same time as an antipsychotic could result in increases in the blood level of both medications,112 because of competitive inhibition of hepatic microsomal oxidative enzymes:114,115 a pharmacokinetic interaction could increase plasma antidepressant levels in patients by up to 70%,116 while antipsychotic concentrations in plasma might rise up to 50% when a TCA is added.117 SSRI and other newer generations of antidepressants could also lead to adverse pharmacological interactions with clozapine or haloperidol, which are probably mediated through competitive inhibition of the hepatic oxidative enzymes – cytochrome P (CYP)-450 system.118,119

CYP-450 enzymes are widely involved in the metabolism of psychotropic drugs, including antidepressants and antipsychotics. CYP enzymes are classified into different families and isozymes. When the co-administered antidepressant shares the same isozyme with the antipsychotic in an augmentation therapy, the competitive inhibition of CYP enzyme(s) would induce an increase in blood level of antipsychotic, and of antidepressant sometimes as well. As shown in Table 3, pharmacokinetic interactions between antidepressants and antipsychotics are listed, including the isozymes that are competitively inhibited in the interactions.120

Table 3.

Pharmacokinetic interactions between antidepressants and antipsychotics, and the CYP-450 isozymes involved

| Haloperidol | Pimozide | Clozapine | Risperidone | Olanzapine | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCAs | TCAs↑ | TCAs↑ | na | na | na |

| CYP2D6 | CYP2D6, CYP3A4 | ||||

| Fluoxetine | AP↑ | AP↑ 40%–70% | Active AP↑ 75% | na | |

| CYP2D6 | CYP1A2, CYP2D6, CYP2C19, CYP3A4 | CYP2D6, CYP3A4 | CYP2D6 | ||

| Paroxetine | na | na | AP↑ 20%–40% | Active AP↑↑ 45% | na |

| CYP2D6 | CYP2D6 | ||||

| Fluvoxamine | ↑ 1.8–4.2-fold | na | AP↑ 5–10-fold | AP↑ 10%–20% | AP↑ 2-fold |

| CYP1A2, CYP3A4 | CYP1A2, CYP2C19, CYP3A4 | CYP2D6, CYP3A4 | CYP1A2 | ||

| Sertraline | AP↑ | AP↑ | na | AP↑ | na |

| CYP2D6 | CYP3A4, CYP1A2 | CYP2D6 | |||

| Citalopram/escitalopram | na | AP↑ | na | na | na |

| Nefazodone | CYP3A4 |

Note:↑, increase.

Abbreviations: TCA, tricyclic antidepressant; CYP, cytochrome P; AP, antipsychotics; na, not applicable.

Different antidepressants show considerably different potency to inhibit CYP enzymes. Fluoxetine reacts predominantly with CYP2D6, and also other isozymes, including CYP2C9, CYP2C19, and CYP3A4. Fluoxetine and its metabolite norfluoxetine have important inhibitory effects on CYP enzymes. Due to their long elimination half-life, a couple of days in general, the inhibition effect on CYP enzymes can persist for up to 6 weeks after discontinuation of the antidepressant.121 Fluvoxamine interacts with several CYP enzymes non-selectively; it has a potential for significant clinical interaction with other drugs.122 Sertraline and citalopram are relatively moderate to weak inhibitors of the CYP enzymes, including CYP2D6.123,124 With respect to drug interactions, citalopram is considered as the safest SSRI to use in augmentation therapy.

Interestingly, Bertilsson et al have suggested that various plasma concentrations of antidepressants and antipsychotics from different patients given the same dose are the result of the interindividual differences in the activity of CYP enzymes.125,126 The lower activity of CYP enzymes manifested among the Asian population could be one of the explanations for their lower tolerance to antidepressants. This knowledge could be useful in the prediction of clinically significant drug-drug interactions in personalized medicine.

In clinical practice, both antipsychotics and antidepressants in combination therapy should be adjusted into a safer yet efficient dose; preferably, setting a standard range of their blood levels could be helpful.

Conclusion

Symptoms of depression are common in schizophrenia; they can occur at any phase. Besides having low mood, patients suffering from depression report declines in their physical health, as well as the quality of their lives; about 10% of the schizophrenic patients commit suicide. It is recommended to treat patients with schizophrenia and depressive symptoms firstly with an optimal dose of second generation antipsychotics and a supplemental anti Parkinsonian agent; if significant depressive symptoms persist after optimization, antidepressants, preferably SSRIs, are recommended.9,58 However, there is no simple answer to the question whether antidepressants could overall be beneficial in treating patients with schizophrenia. To our knowledge, the effectiveness of adjunctive antidepressants on the depressive symptoms in patients with schizophrenia varies considerably. This variation is possibly associated with divergent states of psychotic illness and depression, various psychotropic medications and substance use/abuse, different properties of antidepressants themselves, individual variance in the activity of drug metabolism enzymes, and utilization of psychosocial interventions.127 Further, there is a substantial risk of worsening psychosis and other symptoms by adding antidepressants into treatment.

Good clinical practice should carefully evaluate the individual diagnosis and medication/psychotherapy. Appropriate use of antidepressants could improve depressive symptoms in patients with schizophrenia, but extra caution should be given in terms of adverse effects.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Buckley PF, Miller BJ, Lehrer DS, Castle DJ. Psychiatric comorbidities and schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35:383–402. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hausmann A, Fleischhacker WW. Differential diagnosis of depressed mood in patients with schizophrenia: a diagnostic algorithm based on a review. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2002;106:83–96. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.02120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Möller H-J. Drug treatment of depressive symptoms in schizophrenia. Clin Schizophr Relat Psychoses. 2008;1:328–340. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siris SG, Bench C. Depression and Schizophrenia. In: Hirsch SR, Weinberger DR, editors. Schizophrenia. Oxford: Blackwell Science Ltd; 2007. pp. 142–167. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freudenreich O, Tranulis C, Cather C, Henderson DC, Evins AE, Goff DC. Depressive symptoms in schizophrenia outpatients – prevalence and clinical correlates. Clin Schizophr Relat Psychoses. 2008;2:127–135. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hirsch SR, Jolley AG, Barnes TRE, et al. Dysphoric and depressive symptoms in chronic schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 1989;2:259–264. doi: 10.1016/0920-9964(89)90002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson DA. Studies of depressive symptoms in schizophrenia: I. The prevalence of depression and its possible causes. Br J Psychiatry. 1981;139:89–101. doi: 10.1192/bjp.139.2.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siris SG. Diagnosis of secondary depression in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1991;17:75–98. doi: 10.1093/schbul/17.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siris SG. Treating ‘depression’ in patients with schizophrenia. Curr Psychiatr. 2012;11:35. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zisook S, Nyer M, Kasckow J, Golshan S, Lehman D, Montross L. Depressive symptom patterns in patients with chronic schizophrenia and subsyndromal depression. Schizophr Res. 2006;86:226–233. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.03.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:8. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martin RL, Cloninger CR, Guze SB, Clayton PJ. Frequency and differential diagnosis of depressive syndromes in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 1985;46:9–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koreen AR, Siris SG, Chakos M, Alvir J, Mayerhoff D, Lieberman J. Depression in first-episode schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:1643–1643. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.11.1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGlashan TH, Carpenter WT., Jr Postpsychotic depression in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1976;33(2):231–239. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1976.01770020065011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Siris SG, Addington D, Azorin J-M, Falloon IRH, Gerlach J, Hirsch SR. Depression in schizophrenia: recognition and management in the USA. Schizophr Res. 2001;47:185–197. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(00)00135-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zisook S, McAdams LA, Kuck J, et al. Depressive symptoms in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1736–1743. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.11.1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Markou P. Depression in schizophrenia: a descriptive study. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1996;30:354–357. doi: 10.3109/00048679609064999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nordentoft M, Mortensen PB, Pedersen CB. Absolute risk of suicide after first hospital contact in mental disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:1058–1064. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Palmer BA, Pankratz VS, Bostwick JM. The lifetime risk of suicide in schizophrenia: a reexamination. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:247–253. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.3.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Häfner H, Löffler W, Maurer K, Hambrecht M, Heiden W. Depression, negative symptoms, social stagnation and social decline in the early course of schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1999;100:105–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1999.tb10831.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bechdolf A, Schultze-Lutter F, Klosterkötter J. Self-experienced vulnerability, prodromal symptoms and coping strategies preceding schizophrenic and depressive relapses. Eur Psychiatry. 2002;17:384–393. doi: 10.1016/s0924-9338(02)00698-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iyer SN, Boekestyn L, Cassidy CM, King S, Joober R, Malla AK. Signs and symptoms in the pre-psychotic phase: description and implications for diagnostic trajectories. Psychol Med. 2008;38(8):1147–1156. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708003152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lung F-W, Shu B-C, Chen P-F. Personality and emotional response in schizophrenics with persistent auditory hallucination. Eur Psychiatry. 2009;24:470–475. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Birchwood M, Iqbal Z, Upthegrove R. Psychological pathways to depression in schizophrenia. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;255:202–212. doi: 10.1007/s00406-005-0588-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scholes B, Martin CR. Measuring depression in schizophrenia with questionnaires. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2013;20:17–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2012.01877.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Birchwood M, Iqbal Z, Chadwick P, Trower P. Cognitive approach to depression and suicidal thinking in psychosis. 1. Ontogeny of post-psychotic depression. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:516–521. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.6.516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jeczmien P, Levkovitz Y, Weizman A, Carmel Z. Post-psychotic depression in schizophrenia. Isr Med Assoc J. 2001;3:589–592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Birchwood M, Mason R, MacMillan F, Healy J. Depression, demoralization and control over psychotic illness: a comparison of depressed and non-depressed patients with a chronic psychosis. Psychol Med. 1993;23:387–387. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700028488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jin H, Zisook S, Palmer BW, Patterson TL, Heaton RK, Jeste DV. Association of depressive symptoms with worse functioning in schizophrenia: a study in older outpatients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62:797–803. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v62n1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.WHO . The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barnes TR, McPhillips MA. How to distinguish between the neuroleptic-induced deficit syndrome, depression and disease-related negative symptoms in schizophrenia. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1995;10(suppl 3):115–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kasckow JW, Zisook S. Co-occurring depressive symptoms in the older patient with schizophrenia. Drugs Aging. 2008;25:631–647. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200825080-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harrow M, Yonan CA, Sands JR, Marengo J. Depression in schizophrenia: are neuroleptics, akinesia, or anhedonia involved? Schizophr Bull. 1994;20:327. doi: 10.1093/schbul/20.2.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Palomo T, Archer T, Kostrzewa RM, Beninger RJ. Comorbidity of substance abuse with other psychiatric disorders. Neurotox Res. 2007;12:17–27. doi: 10.1007/BF03033898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Addington D, Addington J, Maticka-Tyndale E. Specificity of the Calgary Depression Scale for schizophrenics. Schizophr Res. 1994;11:239–244. doi: 10.1016/0920-9964(94)90017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schennach R, Obermeier M, Seemüller F, et al. Evaluating depressive symptoms in schizophrenia: a psychometric comparison of the Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia and the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. Psychopathology. 2012;45(5):276–285. doi: 10.1159/000336729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Addington D, Addington J, Atkinson M. A psychometric comparison of the Calgary depression scale for schizophrenia and the Hamilton depression rating scale. Schizophr Res. 1996;19(2–3):205–212. doi: 10.1016/0920-9964(95)00070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lako IM, Bruggeman R, Knegtering H, et al. A systematic review of instruments to measure depressive symptoms in patients with schizophrenia. J Affect Disord. 2012;140(1):38–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bernard D, Lancon C, Auquier P, Reine G, Addington D. Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia: a study of the validity of a French-language version in a population of schizophrenic patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1998;97(1):36–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1998.tb09960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kontaxakis VP, Havaki-Kontaxaki BJ, Margariti MM, et al. The Greek version of the calgary depression scale for schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2000;94(2):163–171. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(00)00137-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sarró S, Dueñas RM, Ramírez N, et al. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Spanish version of the Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2004;68(2–3):349–356. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(02)00490-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suttajit S, Srisurapanont M, Pilakanta S, Charnsil C, Suttajit S. Reliability and validity of the Thai version of the Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2013;9:113–118. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S40292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xiao W, Liu H, Zhang H, et al. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2009;43(6):548–553. doi: 10.1080/00048670902873672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bressan RA, Chaves AC, Shirakawa I, de Mari J. Validity study of the Brazilian version of the Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 1998;32(1):41–49. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(98)00029-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.American Psychiatric Association . American Psychiatric Association Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of Psychiatric Disorders: Compendium 2006. Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists Clinical Practice Guidelines Team for the Treatment of Schizophrenia and Related Disorders Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of schizophrenia and related disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2005;39(1–2):1–30. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2005.01516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) National Clinical Practice Guideline for Schizophrenia. United Kingdom: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bartels SJ, Drake RE. Depression in schizophrenia: current guidelines to treatment. Psychiatr Q. 1989;60:337–357. doi: 10.1007/BF01064357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Micallef J, Fakra E, Blin O. Intérêt des antidépresseurs chez le patient schizophrène présentant un syndrome dépressif. L’Encéphale. 2006;32:263–269. doi: 10.1016/s0013-7006(06)76153-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Whitehead C, Moss S, Cardno A, Lewis G. Antidepressants for the treatment of depression in people with schizophrenia: a systematic review. Psychol Med. 2003;33:589–599. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703007645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McFarlane WR, Dixon L, Lukens E, Lucksted A. Family psychoeducation and schizophrenia: a review of the literature. J Marital Fam Ther. 2003;29(2):223–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2003.tb01202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tursi MF, Baes C, Camacho FR, Tofoli SM, Juruena MF. Effectiveness of psychoeducation for depression: a systematic review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2013;47(11):1019–1031. doi: 10.1177/0004867413491154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jones C, Hacker D, Cormac I, Meaden A, Irving CB. Cognitive behaviour therapy versus other psychosocial treatments for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;4:Cd008712. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008712.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sarin F, Wallin L, Widerlov B. Cognitive behavior therapy for schizophrenia: a meta-analytical review of randomized controlled trials. Nord J Psychiatry. 2011;65(3):162–174. doi: 10.3109/08039488.2011.577188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chakos M, Glick I, Miller A, et al. Special section on CATIE baseline data: baseline use of concomitant psychotropic medications to treat schizophrenia in the CATIE trial. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57:1094–1101. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.8.1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lako IM, Taxis K, Bruggeman R, et al. The course of depressive symptoms and prescribing patterns of antidepressants in schizophrenia in a one-year follow-up study. Eur Psychiatry. 2012;27:240–244. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2010.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM. Translating research into practice: the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) treatment recommendations. Schizophr Bull. 1998;24:1–10. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lehman AF, Lieberman JA, Dixon LB, et al. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Buchanan RW, Kreyenbuhl J, Zito JM, Lehman A. Relationship of the Use of Adjunctive Pharmacological Agents to Symptoms and Level of Function in Schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1035–1043. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.6.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM. Patterns of usual care for schizophrenia: Initial results from the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) Client Survey. Schizophr Bull. 1998;24:11–20. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Buchanan RW, Kreyenbuhl J, Kelly DL, et al. Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) The 2009 schizophrenia PORT psychopharmacological treatment recommendations and summary statements. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36:71–93. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bianchi S, Bianchini E, Scanavacca P. Use of antipsychotic and antidepressant within the Psychiatric Disease Centre, Regional Health Service of Ferrara. BMC Clin Pharmacol. 2011;11:21. doi: 10.1186/1472-6904-11-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Himelhoch S, Slade E, Kreyenbuhl J, Medoff D, Brown C, Dixon L. Antidepressant prescribing patterns among VA patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2012;136:32–35. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Acquaviva E, Gasquet I, Falissard B. Psychotropic combination in schizophrenia. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;61:855–861. doi: 10.1007/s00228-005-0034-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mallinger JB, Lamberti SJ. Racial differences in the use of adjunctive psychotropic medications for patients with schizophrenia. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2007;10:15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Xiang YT, Ungvari GS, Wang CY, et al. Adjunctive antidepressant prescriptions for hospitalized patients with schizophrenia in Asia (2001–2009) Asia Pac Psychiatry. 2013;5(2):E81–E87. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-5872.2012.00231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lam RW, Peters R, Sladen-Dew N, Altman S. A community-based clinic survey of antidepressant use in persons with schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatry. 1998;43:513–516. doi: 10.1177/070674379804300511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Levinson DF, Umapathy C, Musthaq M. Treatment of schizoaffective disorder and schizophrenia with mood symptoms. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1138–1148. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.8.1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Siris SG, Van Kammen DP, Docherty JP. Use of antidepressant drugs in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1978;35:1368. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1978.01770350094009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Prusoff BA, Williams DH, Weissman MM, Astrachan BM. Treatment of secondary depression in schizophrenia: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of amitriptyline added to perphenazine. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1979;36:569. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1979.01780050079010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Siris SG, Bermanzohn PC, Mason SE, Shuwall MA. Maintenance imipramine therapy for secondary depression in schizophrenia: a controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:109. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950020033003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zisook S, Kasckow JW, Golshan S, et al. Citalopram augmentation for subsyndromal symptoms of depression in middle-aged and older outpatients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70:562. doi: 10.4088/jcp.08m04261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rummel C, Kissling W, Leucht S. Antidepressants as add-on treatment to antipsychotics for people with schizophrenia and pronounced negative symptoms: A systematic review of randomized trials. Schizophr Res. 2005;80:85–97. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sepehry AA, Potvin S, Elie R, Stip E. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) add-on therapy for the negative symptoms of schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:604–610. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Singh SP, Singh V, Kar N, Chan K. Efficacy of antidepressants in treating the negative symptoms of chronic schizophrenia: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;197:174–179. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.067710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chaichan W. Olanzapine plus fluvoxamine and olanzapine alone for the treatment of an acute exacerbation of schizophrenia. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004;58(4):364–368. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2004.01269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Arias HR. Is the inhibition of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors by bupropion involved in its clinical actions? Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;41(11):2098–2108. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ferris RM, Cooper BR, Maxwell RA. Studies of bupropion’s mechanism of antidepressant activity. J Clin Psychiatry. 1983;44(5 pt 2):74–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Saiz Ruiz J, Gibert J, Gutierrez Fraile M, et al. Bupropion: efficacy and safety in the treatment of depression. Actas Esp Psiquiatr. 2011;39(suppl 1):1–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Nieuwstraten CE, Dolovich LR. Bupropion versus selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors for treatment of depression. Ann Pharmacother. 2001;35(12):1608–1613. doi: 10.1345/aph.1A099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Grunebaum MF, Keilp JG, Ellis SP, et al. SSRI versus bupropion effects on symptom clusters in suicidal depression: post hoc analysis of a randomized clinical trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(9):872–879. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12m08000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Englisch S, Morgen K, Meyer-Lindenberg A, Zink M. Risks and benefits of bupropion treatment in schizophrenia: a systematic review of the current literature. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2013;36(6):203–215. doi: 10.1097/WNF.0b013e3182a8ea04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kishi T, Iwata N. Meta-analysis of noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressant use in schizophrenia. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;17(2):343–354. doi: 10.1017/S1461145713000667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Scates AC, Doraiswamy PM. Reboxetine: a selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor for the treatment of depression. Ann Pharmacother. 2000;34(11):1302–1312. doi: 10.1345/aph.19335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 12 new-generation antidepressants: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;373(9665):746–758. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60046-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kramer MS, Vogel WH, DiJohnson C, et al. Antidepressants in ‘depressed’ schizophrenic inpatients. A controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46:922–928. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810100064012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Addington D, Addington J, Patten S, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled comparison of the efficacy of sertraline as treatment for a major depressive episode in patients with remitted schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2002;22:20–25. doi: 10.1097/00004714-200202000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mulholland C, Lynch G, Cooper SJ, King DJ. 65–139 – A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of sertraline for depressive symptoms in stable, chronic schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 1997;42:188S. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Terevnikov V, Stenberg JH, Tiihonen J, et al. Add-on mirtazapine improves depressive symptoms in schizophrenia: a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled study with an open-label extension phase. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2011;26:188–193. doi: 10.1002/hup.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Whitehead C, Moss S, Cardno A, Lewis G. Antidepressants for people with both schizophrenia and depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002:CD002305. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Goff DC, Amico E, Sarid-Segal O, Midha KK, Hubbard JW. A placebo-controlled trial of fluoxetine added to neuroleptic in patients with schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology. 1995;117:417–423. doi: 10.1007/BF02246213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Devi S, Rao NP, Badamath S, Chandrashekhar CR, Janardhan Reddy YC. Prevalence and clinical correlates of obsessive-compulsive disorder in schizophrenia. Compr Psychiatry. 2015;56:141–148. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2014.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Poyurovsky M, Weizman A, Weizman R. Obsessive-compulsive disorder in schizophrenia: clinical characteristics and treatment. CNS Drugs. 2004;18(14):989–1010. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200418140-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Schirmbeck F, Zink M. Comorbid obsessive-compulsive symptoms in schizophrenia: contributions of pharmacological and genetic factors. Front Pharmacol. 2013;4:99. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2013.00099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Fonseka TM, Richter MA, Muller DJ. Second generation antipsychotic-induced obsessive-compulsive symptoms in schizophrenia: a review of the experimental literature. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2014;16(11):510. doi: 10.1007/s11920-014-0510-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Schirmbeck F, Esslinger C, Rausch F, Englisch S, Meyer-Lindenberg A, Zink M. Antiserotonergic antipsychotics are associated with obsessive-compulsive symptoms in schizophrenia. Psychol Med. 2011;41(11):2361–2373. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711000419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Schirmbeck F, Rausch F, Englisch S, et al. Differential effects of antipsychotic agents on obsessive-compulsive symptoms in schizophrenia: a longitudinal study. J Psychopharmacol. 2013;27(4):349–357. doi: 10.1177/0269881112463470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kim SW, Shin IS, Kim JM, et al. The 5-HT2 receptor profiles of antipsychotics in the pathogenesis of obsessive-compulsive symptoms in schizophrenia. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2009;32(4):224–226. doi: 10.1097/WNF.0b013e318184fafd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Venkatasubramanian G, Rao NP, Behere RV. Neuroanatomical, neurochemical, and neurodevelopmental basis of obsessive-compulsive symptoms in schizophrenia. Indian J Psychol Med. 2009;31(1):3–10. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.53308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kwon JS, Joo YH, Nam HJ, et al. Association of the glutamate transporter gene SLC1A1 with atypical antipsychotics-induced obsessive-compulsive symptoms. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(11):1233–1241. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ucok A, Kivrak Tihan A, Karadayi G, Tukel R. Obsessive compulsive symptoms are related to lower quality of life in patients with Schizophrenia. International journal of psychiatry in clinical practice. 2014;18(4):243–247. doi: 10.3109/13651501.2014.943243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lysaker PH, Bryson GJ, Marks KA, Greig TC, Bell MD. Association of obsessions and compulsions in schizophrenia with neurocognition and negative symptoms. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2002;14(4):449–453. doi: 10.1176/jnp.14.4.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Schirmbeck F, Zink M. Obsessive-compulsive syndromes in schizophrenia: a case for polypharmacy? In: Ritsner MS, editor. Polypharmacy in Psychiatry Practice. II. Netherlands: Springer; 2013. pp. 233–261. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Biondi M, Fedele L, Arcangeli T, Pancheri P. Development of obsessive-compulsive symptoms during clozapine treatment in schizophrenia and its positive response to clomipramine. Psychother Psychosom. 1999;68(2):111–112. doi: 10.1159/000012321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Poyurovsky M, Hermesh H, Weizman A. Fluvoxamine treatment in clozapine-induced obsessive-compulsive symptoms in schizophrenic patients. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1996;19(4):305–313. doi: 10.1097/00002826-199619040-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Buchanan RW, Kirkpatrick B, Bryant N, Ball P, Breier A. Fluoxetine augmentation of clozapine treatment in patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153(12):1625–1627. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.12.1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Schirmbeck F, Zink M. Cognitive behavioural therapy for obsessive-compulsive symptoms in schizophrenia. Cogn Behav Ther. 2013;6:e7. [Google Scholar]

- 108.MacCabe JH, Marks IM, Murray RM. Behavior therapy attenuates clozapine-induced obsessions and compulsions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(12):1179–1180. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v63n1214b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Butler T, Schofield PW, Greenberg D, et al. Reducing impulsivity in repeat violent offenders: an open label trial of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2010;44:1137–1143. doi: 10.3109/00048674.2010.525216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Pollock BG, Mulsant BH, Rosen J, et al. Comparison of citalopram, perphenazine, and placebo for the acute treatment of psychosis and behavioral disturbances in hospitalized, demented patients. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:460–465. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.3.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Science JMECfCDaC . Second-Generation Antidepressants for Treating Adult Depression: An UpdateComparative Effectiveness Review Summary Guides for Clinicians. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Plasky P. Antidepressant usage in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1991;17:649. doi: 10.1093/schbul/17.4.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Centorrino F, Baldessarini RJ, Frankenburg FR, Kando J, Volpicelli SA, Flood JG. Serum levels of clozapine and norclozapine in patients treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:820–822. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.6.820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Cook PE, Dermer SW, Cardamone J. Imipramine-flupenthixol decanoate interaction. Can J Psychiatry. 1986;31(3):235–237. doi: 10.1177/070674378603100310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Gram LF, Christiansen J, Overø KF. Pharmacokinetic interaction between neuroleptics and tricyclic antidepressants in the rat. Acta Pharmacol Toxicol. 1974;35:223–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1974.tb00742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Linnoila M, George LK, Guthrie S. Interaction between antidepressants and perphenazine in psychiatric patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1982;139(10):1329–1331. doi: 10.1176/ajp.139.10.1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Loga S, Curry S, Lader M. Interaction of chlorpromazine and nortriptyline in patients with schizophrenia. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1981;6:454–462. doi: 10.2165/00003088-198106060-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Daniel DG, Randolph C, Jaskiw G, et al. Coadministration of fluvoxamine increases serum: concentrations of haloperidol. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1994;14:340–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Nemeroff CB, DeVane CL, Pollock BG. Newer antidepressants and the cytochrome P450 system. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:311–320. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.3.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Rothschild AJ. The Evidence-Based Guide to Antidepressant Medications. Arlington: American Psychiatric Publication; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 121.Wernicke JF. Safety and side effect profile of fluoxetine. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2004;3:495–504. doi: 10.1517/14740338.3.5.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.van Harten J. Overview of the pharmacokinetics of fluvoxamine. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1995;29(suppl 1):1–9. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199500291-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Brøsen K, Naranjo CA. Review of pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic interaction studies with citalopram. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2001;11:275–283. doi: 10.1016/s0924-977x(01)00101-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Preskorn SH, Shah R, Neff M, Golbeck AL, Choi J. The potential for clinically significant drug-drug interactions involving the CYP 2D6 system: effects with fluoxetine and paroxetine versus sertraline. J Psychiatr Pract. 2007;13:5–12. doi: 10.1097/00131746-200701000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Bertilsson L. Metabolism of antidepressant and neuroleptic drugs by cytochrome P450s: clinical and interethnic aspects. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2007;82:606–609. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Bertilsson L, Dahl M-L, Dalén P, Al-Shurbaji A. Molecular genetics of CYP2D6: clinical relevance with focus on psychotropic drugs. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;53:111–122. doi: 10.1046/j.0306-5251.2001.01548.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.De Silva MJ, Cooper S, Li HL, Lund C, Patel V. Effect of psychosocial interventions on social functioning in depression and schizophrenia: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;202:253–260. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.118018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Rittmannsberger H, Meise U, Schauflinger K, Horvath E, Donat H, Hinterhuber H. Polypharmacy in psychiatric treatment. Patterns of psychotropic drug use in Austrian psychiatric clinics. Eur Psychiatry. 1999;14:33–40. doi: 10.1016/s0924-9338(99)80713-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Kiivet RA, Llerena A, Dahl ML, et al. Patterns of drug treatment of schizophrenic patients in Estonia, Spain and Sweden. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1995;40:467–476. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1995.tb05791.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Ponto T, Ismail NI, Abdul Majeed AB, Marmaya NH, Zakaria ZA. A prospective study on the pattern of medication use for schizophrenia in the outpatient pharmacy department, Hospital Tengku Ampuan Rahimah, Selangor, Malaysia. Methods Find Exp Clin Pharmacol. 2010;32:427–432. doi: 10.1358/mf.2010.32.6.1477907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.An FR, Xiang YT, Wang CY, et al. Change of psychotropic drug prescription for schizophrenia in a psychiatric institution in Beijing, China between 1999 and 2008. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;48:270–274. doi: 10.5414/cpp48270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Becker RE. Implications of the efficacy of thiothixene and a chlorpromazine-imipramine combination for depression in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1983;140:208–211. doi: 10.1176/ajp.140.2.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Siris SG, Morgan V, Fagerstrom R, Rifkin A, Cooper TB. Adjunctive imipramine in the treatment of postpsychotic depression. A controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1987;44:533–539. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800180043008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Silver H, Nassar A. Fluvoxamine improves negative symptoms in treated chronic schizophrenia: an add-on double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Biol Psychiatry. 1992;31:698–704. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(92)90279-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Arango C, Kirkpatrick B, Buchanan RW. Fluoxetine as an adjunct to conventional antipsychotic treatment of schizophrenia patients with residual symptoms. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2000;188:50–53. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200001000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Spina E, De Domenico P, Ruello C, et al. Adjunctive fluoxetine in the treatment of negative symptoms in chronic schizophrenic patients. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1994;9:281–285. doi: 10.1097/00004850-199400940-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Iancu I, Tschernihovsky E, Bodner E, Piconne AS, Lowengrub K. Escitalopram in the treatment of negative symptoms in patients with chronic schizophrenia: A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Psychiatry Res. 2010;179:19–23. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Singh AN, Saxena B, Nelson HL. A controlled clinical study of trazodone in chronic schizophrenic patients with pronounced depressive symptomatology. Curr Ther Res. 1978;23:485–501. [Google Scholar]

- 139.Dufresne RL, Kass DJ, Becker RE. Bupropion and thiothixene versus placebo and thiothixene in the treatment of depression in schizophrenia. Drug Dev Res. 1988;12:259–266. [Google Scholar]

- 140.Berk M, Gama CS, Sundram S, et al. Mirtazapine add-on therapy in the treatment of schizophrenia with atypical antipsychotics: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2009;24:233–238. doi: 10.1002/hup.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Kurland AA, Nagaraju A. Viloxazine and the depressed schizophrenic – methodological issues. J Clin Pharmacol. 1981;21:37–41. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1981.tb01730.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Schutz G, Berk M. Reboxetine add on therapy to haloperidol in the treatment of schizophrenia: A preliminary double-blind randomized placebo-controlled study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001;16:275–278. doi: 10.1097/00004850-200109000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]