Abstract

BACKGROUND

Care management has become a widespread strategy for improving chronic illness care. However, primary care provider (PCP) participation in programs has been poor. Because the success of care management relies on provider engagement, understanding provider perspectives is necessary.

OBJECTIVE

Our goal was to identify care management functions most valuable to PCPs in hypertension treatment.

DESIGN

Six focus groups were conducted to discuss current challenges in hypertension care and identify specific functions of care management that would improve care.

PARTICIPANTS

The study included 39 PCPs (participation rate: 83 %) representing six clinics, two of which care for large African American populations and four that are in underserved locations, in the greater Baltimore metropolitan area.

APPROACH

This was a qualitative analysis of focus groups, using grounded theory and iterative coding.

KEY RESULTS

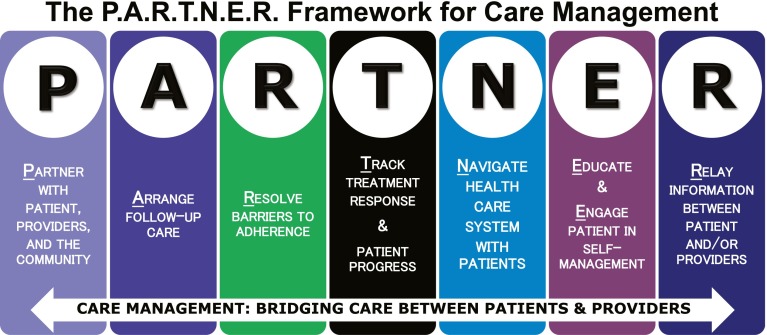

Providers desired achieving blood pressure control more rapidly. Collaborating with care managers who obtain ongoing patient data would allow treatment plans to be tailored to the changing life conditions of patients. The P.A.R.T.N.E.R. framework summarizes the care management functions that providers reported were necessary for effective collaboration: Partner with patients, providers, and the community; Arrange follow-up care; Resolve barriers to adherence; Track treatment response and progress; Navigate the health care system with patients; Educate patients & Engage patients in self-management; Relay information between patients and/or provider(s).

CONCLUSIONS

The P.A.R.T.N.E.R. framework is the first to offer a checklist of care management functions that may promote successful collaboration with PCPs. Future research should examine the validity of this framework in various settings and for diverse patient populations affected by chronic diseases.

KEY WORDS: care management, chronic disease, implementation research, primary care, qualitative research

INTRODUCTION

Despite the availability of effective therapy, control of chronic diseases remains poor in the U.S., particularly amongst disadvantaged groups.1–5 Successful treatment is threatened by a fragmented health care system and inadequate chronic disease care infrastructure.6,7 For example, though patients benefit from frequent follow-up, education about illness, coaching to support self-management, and access to community-based resources, physicians in primary care lack the time, tools, and resources to provide patients all these services.7–9 Thus, the Institute of Medicine has urged redesign of chronic illness care delivery in primary care.10

A widespread strategy for improving chronic illness treatment,11–17 care management involves non-physician care managers working with patients between physician encounters to improve clinical care, enhance care coordination,13–15 and reduce health care utilization.18

Because the success of care management relies on both patient and provider engagement with care managers, understanding these perspectives is necessary for gaining buy-in.19 Most patients report valuing care managers who help with behavior modification, by monitoring disease activity and treatment effect; coordinating follow-up care; and modifying treatment under the guidance of doctors.20,21 One study, using semi-structured interviews, reported physician perceptions of the role(s) care managers played; roles identified included patient follow-up, management of difficult patients, care coordination, and patient education.22 Literature is also available about provider satisfaction with and motivations for working with care management and provider preferences for care manager qualities.20–23 To our knowledge, however, provider perspectives on specific functions that should be designed into care management programs have not been examined; providers may have unique perspectives on the care patients should receive, but are unable to deliver on their own.

We conducted this study to describe primary care provider (PCP) perspectives on care management functions essential to collaboration in hypertension care. As a common chronic condition that has become the focus of many regulatory agencies assessing the quality of primary care, hypertension is a timely topic.24,25

METHODS

Setting & Participants

Johns Hopkins Community Physicians (JHCP) is an integrated network of 17 primary care practices throughout Maryland with a managed care infrastructure and staff-model practice, serving 130,000 patients and having a shared electronic medical record system. The six study sites, serving 64,000 patients, are located in Baltimore County and Baltimore City. These sites were chosen to include two practices with large African American patient populations (21.2 % and 75.8 % African American) and four practices in medically underserved areas. The proportion of patients with uncontrolled (≥ 140/90 mmHg) hypertension based on the most recent blood pressure at the start of the study at these sites ranged from 31 % to 51 % for African Americans, and 24 % to 44 % for Whites.26

All 47 PCPs serving the six clinics were invited to focus groups through letters. No incentives were provided for participation.

Data Collection

Participant demographics were collected by voluntary survey and publically available records. Focus group data in this study were part of a larger study, Project ReD CHiP (Reducing Disparities and Controlling Hypertension in Primary Care) at the Johns Hopkins Center to Eliminate Cardiovascular Health Disparities; this is a pragmatic trial, still underway, to control hypertension and reduce related disparities.26 We report on the six focus groups that were conducted to help inform the design of the care management arm of Project ReD CHiP: one focus group was conducted at a provider retreat (n = 15 providers), and five were conducted at intervention clinics (median = six providers, range four to 11). Providers who participated at the retreat were eligible to participate again at their respective clinic (n = 11 providers). One clinic site did not have its own focus group; two of the six providers from this site participated at the provider retreat focus group. A total of 39 providers participated in at least one of the six focus groups. Providers were told of the general care management strategy that would be used in ReD CHiP (i.e., adult hypertensive patients with uncontrolled blood pressure would be invited to attend office-based sessions with trained care managers who would work with providers to educate patients about hypertension, and encourage adherence to medications, following the DASH diet, and increasing physical activity).27 Providers were informed that further specifications would be determined based on focus group data.

The focus group at the provider retreat covered a broad array of topics related to current hypertension care and its challenges, the possible usefulness of care management, and potential challenges to care management in primary care practice. Preliminary themes from the provider retreat focus group suggested that the success of care management would depend heavily on the specific functions it provided; thus, the research team agreed it was necessary to pursue further providers’ perspectives on the functions providers would find desirable. The five clinic-based focus groups were held to capture these views.

Questions and discussion prompts for the focus groups (Appendix 1) were drafted by the research team, modified primarily for clarity of language after pilot testing with board-certified internists on the ReD CHiP community advisory board, and reviewed for relevance and clarity by multiple stakeholders serving on the board until consensus was reached. Focus groups were moderated by a single member of the research team (CA), a PhD epidemiologist with an MPH in Health Behavior and Education and experience in developing focus group questions and conducting focus groups. No prior relationship existed between the moderator and participants. Mean focus group time was 53 min (range: 46–59). Focus groups were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim.

This study was approved by the Johns Hopkins University Institutional Review Board.

ANALYSIS

Data were analyzed iteratively using a grounded theory approach, a method of qualitative analysis that generates hypotheses and theories from data, rather than the more traditional approach of generating hypotheses and then collecting data to test them.28,29 Analysis began with reviewing transcripts line-by-line to derive initial labels to code provider comments about care management. To move towards identifying the core activities of care management desired by providers, codes reflecting similar content were then grouped into broader concepts and/or categories; this facilitated hypothesis generation. The final step focused on theoretical development—that is, describing the relationships between the core concepts and categories that emerged from the data. The result of this final stage was a grounded theory regarding the essential functions for care management, built from the core categories of activities described by providers in our focus groups. This analytic method required a constant comparative approach, wherein interpretations and findings at every stage were compared with existing findings as they surfaced from data analysis.30

Specifically, two public health researchers (AA and JH) independently reviewed the provider retreat focus group and the first two clinic-based focus groups to generate initial codes; these were reviewed for consensus by the research team before coding the remainder of the transcripts. Theoretical saturation, the point at which no additional major themes emerged, occurred after coding the provider retreat and three clinic-based focus groups.31 The research team then examined all coded transcripts to develop consensus regarding the core categories of care management activities that had emerged from the coded data, and then based on these core activities, the team hypothesized the functions of care management providers found most valuable. A code book describing these essential functions and the scope of core activities was developed, and two physician scientists (TH and LC) iteratively recoded all six transcripts with new coding categories, systemically discussing and refining the coding scheme; inter-rater agreement on core activities and essential functions (kappa = 0.92) was high. Investigators AA and JH reviewed recoded transcripts to ensure validity and consistency as well; ambiguity in coding was resolved in discussions between AA, JH, TH, and LC.

NVivo software was used for data management and analysis, including calculation of kappa statistic.

RESULTS

Characteristics of Study Participants

Table 1 describes characteristics of the 39 participants. Most PCPs were physicians (83 %). There was racial diversity: 23 % African American and 21 % Asian. The average number of years since completing residency was 17. Sixty-four percent practiced in an underserved site. The eight non-participating providers were not statistically significantly different from participants.

Table 1.

Description of Focus Group Participants

| Provider Profile n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Provider Type | |

| Medical Doctor | 32 (82 %) |

| Nurse Practitioner | 6 (15 %) |

| Physician Assistant | 1 (3 %) |

| Female | 27 (69 %) |

| Race | |

| White | 20 (51 %) |

| African American | 9 (23 %) |

| Asian | 8 (21 %) |

| Other | 2 (5 %) |

| Specialty | |

| Internal Medicine | 31 (80 %) |

| Family Medicine | 6 (15 %) |

| Other | 2 (5 %) |

| Average Years of Practice (range)* | 17 (6–36) |

| Underserved Site | 24 (62 %) |

*unavailable for five providers

Focus Group Findings

Illustrative quotes for the following findings are provided in Text Box 1.

Text Box 1. Illustrative Quotations from Provider Focus Groups

| Current Status of Hypertension Care in Primary Care |

| • “[Patients are on] five pills. Weight is 300 and blood pressure is 170/80. Creatinine is going up… We have to do something about it. It’s a crisis.” |

| • “I don’t want to end the visit…so much needs to be done [but] three [patients] are waiting.” |

| • “You discuss the essential things: medication changes, side effect and safety monitoring, referrals to specialist, monitoring of complications. But hypertension…is chronic…You can’t solve it in a visit…The care manager can help expand on what [providers] initiate…and support the patient.” |

| • “Education, coordination…motivational interviewing…[can be done] by care managers as well as—maybe better than—me.” |

| • “So much is brought to a visit…Maybe the care manager actually takes some of these things off of your plate.” |

| • “We don’t have the time.” |

| • “I try to tailor treatment…[but] more time [is needed] to get all the [patient] background. We need help personalizing [care] to diverse patients.” |

| • “Some [patients] no matter how much I ask them…they cannot do it on their own.” |

| • “In the inner city… what happens when [patients] leave…none of us can really envision…” |

| • “I can talk about avoiding sodium…But taking extra time to explain what [to] look for on a label. It's just very time consuming.” |

| • “Patients may not know how to handle it themselves.” |

| • “If [patients] are not coming back for…months, you don’t know if things are working.” |

| Essential Functions for Care Management in Hypertension Care |

| Partner with patients, providers, and the community |

| • “…the interpersonal skills… to establish a relationship with whoever the patient is.” |

| • “Be there when [patients] have crises…so they don’t stop taking care of themselves.” |

| • “[The staff]…need to identify with care managers as well.” |

| • “Care managers who understand the community [is] the way to succeed.” |

| Arrange follow-up care |

| • “Some patients…don't understand the need to keep appointments to recheck blood pressure…this is crucial.” |

| • “Help coordinate…what [providers] are doing.” |

| • “Don’t let patients fall of the radar…until their blood pressure, diet, weight, meds are under control…” |

| Resolve barriers to adherence |

| • “Get reliable responses to questions…[about] adherence to the diuretic…or DASH diet.” |

| • “Need good…med reconciliation” |

| • “Are there things occuring at home so [patients] can’t buy medicine? Things that [care managers] could spend more time on.” |

| • “Help [patients]…problem solve…like when they’re eating out and the food is all fried…patients may not know how to deal with it.” |

| Track treatment response and progress |

| • “Collecting data so [providers] know what’s going on…if things are working.” |

| • “Monitor [patients] between visits to get a sense of what direction patients are going.” |

| • “Make sure [patients] stay on track.” |

| Navigate the health care system with patients |

| • “When patients are discharged [from the hospital] or see doctors that don’t know them, their meds get all messed up. Patients suffer. They need help.” |

| • “Navigate the [healthcare] environment so [patients] make it to the specialist and get insurance, transportation, or other services.” |

| Educate patients |

| • “We need help reinforcing…what [hypertension] does, why the meds, the life changes.” |

| • “Give…information…and advice… so that patients get it, and aren’t confused and ignore it.” |

| Engage patients in self-management |

| • “Find out the patient's goal and…through motivational interviewing…direct them.” |

| • “Provide…coaching…so they can begin solving their problems.” |

| • “So patients know when to check their [blood pressure]…what do or even when to get help when it is low or high.” |

| Relay information between the patient and/or provider(s) |

| • “A feedback loop will be key…so [providers] know about [patient] changes before it’s too late.” |

| • “Circle back with the patient…so they don’t get lost about what to do.” |

| Potential Challenges for a Care Management Model of Hypertension Care |

| • “…It’s hard to get the patients here even for regular [provider] visits.” |

| • “Home visit[s], someone to look in cupboards and see what’s [the] kitchen like, would be [useful]. |

| • “…We [may] fragment care too much…When you've got [patients] seeing this person, that person, and the other person, then they don’t get to know anybody and they don't really think that anybody cares.” |

Current Status of Hypertension Care in Primary Care

Providers discussed motivations for care management and their views on its purpose in relation to their roles. They identified their clinic visits with patients as an indispensable part of hypertension care—a time for providers to make critical decisions about next steps in treatment, including medication changes, monitoring for complications, checking for side medication effects, and making referrals. Providers voiced that more time and resources were needed to personalize treatment, educate patients, and teach self-management, all of which are essential for effective chronic disease control. However, particularly for disadvantaged populations, providers felt it was very challenging to do so on their own, due to: other competing patient needs; short encounter times and high patient volumes; inadequate availability to schedule frequent follow-up with patients; and the challenges of patients’ socioeconomic circumstances, poor health literacy, and limited engagement in self-care. Providers identified functions they believed that trained care managers could deliver at least as effectively as providers; these functions are described next. Providers anticipated collaborating with care managers, who could obtain ongoing collateral patient data, allowing iterative tailoring of care plans to the changing life conditions of patients in order to achieve blood pressure control more rapidly.

Essential Functions for Care Management in Collaborative Hypertension Care

The “P.A.R.T.N.E.R. Framework for Care Management,” elaborated in Table 2, captures provider perspectives on essential functions for the care management of hypertension that emerged from the data: partner with the patient, providers, and the community; arrange follow-up care; resolve barriers to adherence; track treatment response and progress; navigate the health care system with the patients; educate patients & engage the patients in self-management; relay information between the patient and/or provider(s). The “scope of core activities” lists tasks satisfying each function of the P.A.R.T.N.E.R. framework. Providers specified some activities as more important in disadvantaged patient populations (marked with asterisks in Table 2). The representative quotes selected in Text Box 1 for the P.A.R.T.N.E.R. framework illustrate how each function and activity in the framework was derived from focus group data.

Table 2.

The P.A.R.T.N.E.R Framework for Care Management

| Essential Functions for Care Managers | Scope of Core Activities Pertaining to Essential Function | |

|---|---|---|

| P | Partner with patients, providers, and the community | - Build working relationships with providers - Gain the trust of the patient* - Provide the patient psychosocial support* - Determine unique circumstances of the patient’s community* |

| A | Arrange follow-up care | - Obtain patient buy-in for timely follow-up care - Coordinate follow-up care with providers - Ensure frequent monitoring to achieve rapid disease control |

| R | Resolve barriers to adherence | - Determine patient adherence to the treatment plan - Elicit barriers (social, physical, psychological, economic) to adherence - Develop solutions together with the patient to overcome barriers* |

| T | Track treatment response and progress | - Gather interval symptomatic and diagnostic data - Evaluate the effectiveness of the current treatment plan - Assist the patient in sustaining control once the goal is reached |

| N | Navigate the health care system with patients | - Support the patient during transitions in care - Aid the patient in accessing needed clinical and social services* |

| E | Educate patients | - Assess the patient’s knowledge and attitudes towards illness - Provide health education appropriate for the patient’s health literacy level and culture* |

| Engage patients in self-management | - Empower the patient to take responsibility in disease management* - Coach the patient in problem-solving skills around disease control* |

|

| R | Relay information between patients and/or provider(s) | - Keep providers appraised of critical updates in the patient’s care - Ensure the patient understands changes in plan suggested by providers |

*May be particularly important in care of disadvantaged populations

Expected Challenges for a Care Management Model of Hypertension Care

Providers voiced concern that if the incorporation of care management increased provider workload, its success would be endangered, as the unsustainable burden on providers was a primary reason for collaborating with care managers. Providers were additionally concerned about the possibility of worsened fragmentation in patient care by the introduction of additional team members. Some providers argued that office-based care management would be more effective if coupled with home-based outreach.

DISCUSSION

Despite considerable investment in care management programs nationwide, data on the factors that make it successful are needed. For example, provider perspectives on the functions that should be incorporated into the design of care management programs could help ensure effective collaboration between PCPs and care managers.

In our study, providers called for more robust efforts to support patients in hypertension care—and, more globally, chronic disease care. While providers attempted to deliver comprehensive hypertension care during clinic visits, they felt challenged primarily by patient and systems factors. They identified functions that they are usually unable to deliver, but believed trained care managers could deliver effectively: to partner with the patient, providers, and the community; arrange follow-up care; resolve barriers to adherence; track treatment response and progress; navigate the health care system with the patients; educate patients and engage the patients in self-management; and relay information between the patient and/or provider(s)—functions that we summarized in the P.A.R.T.N.E.R. framework (Fig. 1). Providers described how collaborating with care managers who perform P.A.R.T.N.E.R. functions would allow for increased patient-centered care and more rapid blood pressure control.

Figure 1.

“P.A.R.T.N.E.R. Framework for Care Management”: a checklist of functions for care mangers.

We believe the P.A.R.T.N.E.R. framework is a novel and important addition to the chronic disease and care management literature. First, there is no prior research describing provider views on the effective organization of outpatient chronic disease care when working with care managers. Our framework provides guidance for the design of care management programs, by describing those services that providers believe they are unable to effectively deliver, but are necessary for patient care. Although providers welcome support from care managers, the inadequate design of care management programs has often resulted in poor participation by physicians.15,32–35 As care management is most effective when patients’ usual care providers work closely with care managers,15 engaging providers is essential. The P.A.R.T.N.E.R. framework summarizes care manager functions that providers desire.

Second, by asking providers how care managers can assist in achieving more rapid disease control, the P.A.R.T.N.E.R. framework advances existing models of chronic disease care management by describing how it can be integrated into clinical workflow. One existing model provides guidance at the health systems level without the granularity to apply to clinical practice.36 Another model has been developed primarily to categorize measurement tools for care coordination and care management, rather than to address clinical care.37 A third model describes specific functions for care management, but has been developed for the pediatric patient population.38 A frequently cited model for chronic disease care activities does not specifically address which activities would be appropriate for care managers.39 And unlike other team-based care models, the P.A.R.T.N.E.R. framework is distinct in specifying provider wishes for care managers to assess treatment response, track disease progress, and address management of patients beyond transitions in care.40,41 Further, our framework is the first to use analyses from primary data to inform its development.

Third, this framework provides a checklist of functions for adult chronic disease care management that can be used to guide the measurement and evaluation of care management initiatives. Indeed, most studies have lacked description of the specific functions performed by care managers and the distribution of effort devoted to each activity, making the comparison and replication of programs difficult.13,15,36 Further, while there is sufficient data to suggest care management effectiveness is greater when it is lengthy, high in patient contact, and includes face-to-face interactions, there is little knowledge about which core functions should be part of care management.15 These shortcomings are related to the absence of a framework for categorizing the care manager functions that are relevant to the clinical environment in which these studies occur.13,15,36,42

There are limitations to our findings. This framework captures only the views of PCPs from six clinics in Baltimore. Further, participating providers were all part of a single network, and their preferences may have been shaped by the network’s culture, including the availability of specialists, social workers, and clinical pharmacists that enable collaborative care. Yet, our providers have many years of experience and come from sites that care for underserved and African American populations, where blood pressure control is most difficult. We are confident, therefore, that selected providers were able to envision a wider range of roles for care managers than if we had recruited providers serving only healthier populations. Although we queried providers about an office-based program, providers commented on various methods of care management, including home visits and social media. To our surprise, providers did not discuss patient advocacy, a topic that has been reported to be important in patient groups.43

There are strengths and limitations related to using grounded theory. It provides a systematic and rigorous approach for rich analysis that can be used to develop data-driven theories. However, data analysis and interpretation is still subject to researcher-induced bias.44 For example, the two physician scientists may have brought their experiences as PCPs to the coding process. Review of data and analysis by the multidisciplinary research team may have guarded against this. Still, P.A.R.T.N.E.R. functions incorporate many activities viewed as important by other groups.20,21 For example, patients desire easy access to care; assistance with behavior modification and care coordination; effective communication with their care team; culturally relevant treatment; and a patient-centered, rather than disease-centered, approach.20,21,45–47

Finally, while future research should examine the validity of our framework in various settings and the effectiveness of P.A.R.T.N.E.R. functions on patient outcomes, several of the functions identified by providers have been reported elsewhere to improve hypertension control and chronic illness care and outcomes.48–51

Despite these limitations, the current work suggests that providers believe care management is an acceptable model for addressing the challenges of delivering chronic illness care in the primary care setting. Provider adoption of care management, however, depends on the particular functions performed by care managers. The P.A.R.T.N.E.R. framework is the first to offer guidance on the organization of clinical activities between providers and care managers from the provider perspective. Use of this framework may assist with designing care management programs capable of overcoming barriers to provider engagement, thereby increasing the opportunity of this delivery model to improve patient care.

Acknowledegments

This work is supported by grants from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (P50HL0105187, K24HL083113, and 5T32HL007180-38), and by the Johns Hopkins Center to Eliminate Cardiovascular Health Disparities.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare they do not have a conflict of interest.

Appendix

Appendix 1: Focus Group Questions

Focus Group Questions used at Provider Retreat (n = 1 retreat)

Q1: Who in your organization is providing assistance to hypertensive patients with increasing adherence to medication regimen, increasing patient exercise, and promoting and adopting a DASH-sodium dietary pattern?

Q2: What do you see as some benefits and drawbacks in using these current approaches, in terms of their effectiveness?

[Description of proposed care management program provided]

Q3: How do you think patients will respond to this care management program?

Q4: In what specific ways can the care manager be beneficial to providers?

Q5. Which patients do you think would fully benefit from this type of care management program?

Q6: How can the care management team be used most effectively?

Q7: In what ways can the care management team interact with you to make sure patients meet blood pressure goals?

Q8: What barriers do you foresee with regard to the success of this intervention?

Q9: Can you think of better ways than care management to help patients with hypertension manage their blood pressure medications and make health-related lifestyle changes? If yes, what are they?

Focus Group Questions used at Clinic Sites (n = 5 clinics)

In an earlier focus group, providers said that patients should be able to identify with their Care Manager. For example, that they should come from the same community and have successfully managed to do the things that we are asking patients to do (such as eating a low-sodium diet and losing weight).

Q1: What other characteristics and skills should the Care Manager have?

Q2: Which of these are critical and which are less important?

REFERENCES

- 1.Burt VL, Cutler JA, Higgins M, Horan MJ, Labarthe D, Whelton P, et al. Trends in the prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in the adult US population. Data from the health examination surveys, 1960 to 1991. Hypertension. 1995;26(1):60–69. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.26.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The sixth report of the Joint National Committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157(21):2413–46. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Clark CM, Fradkin JE, Hiss RG, Lorenz RA, Vinicor F, Warren-Boulton E. Promoting early diagnosis and treatment of type 2 diabetes: the National Diabetes Education Program. J Am Med Assoc. 2000;284(3):363–365. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.3.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klag MJ, Whelton PK, Randall BL, Neaton JD, Brancati FL, Stamler J. End-stage renal disease in African-American and white men. 16-year MRFIT findings. J Am Med Assoc. 1997;277(16):1293–1298. doi: 10.1001/jama.1997.03540400043029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Unequal Treatment:Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care (with CD). Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson ARUhwneopri, editors: The National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed]

- 6.Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. http://www.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=10027. The National Academies Press; 2001. [PubMed]

- 7.Ostbye T, Yarnall KS, Krause KM, Pollak KI, Gradison M, Michener JL. Is there time for management of patients with chronic diseases in primary care? Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(3):209–214. doi: 10.1370/afm.310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corser W, Dontje K. Self-management perspectives of heavily comorbid primary care adults. Prof Case Manag. 2011;16(1):6–15. doi: 10.1097/NCM.0b013e3181f508d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berry-Millett R, Bodenheimer TS. Care management of patients with complex health care needs. The Synthesis project. Research synthesis report. 2009 (19). [PubMed]

- 10.Living Well with Chronic Illness: A Call for Public Health Action <http://www.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=13272>. The National Academies Press; 2012.

- 11.Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation. Comprehensive Primary Care Initiative. http://www.innovations.cms.gov/initiatives/Comprehensive-Primary-Care-Initiative/index.html. Accessed November 19 2014.

- 12.Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Innovation Models. http://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/index.html - views=models. Accessed November 19 2014.

- 13.McDonald KM, Sundaram V, Bravata DM, Lewis R, Lin N, Kraft SA, et al. Closing the Quality Gap: A Critical Analysis of Quality Improvement Strategies (Vol. 7: Care Coordination). Rockville (MD) 2007. [PubMed]

- 14.Wagner EH. The role of patient care teams in chronic disease management. BMJ. 2000;320(7234):569–572. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7234.569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Effectiveness of Outpatient Case Management for Adults With Medical Illness and Complex Care Needs. Comparative Effectiveness Review Summary Guides for Clinicians. Rockville (MD) 2007.

- 16.National Prioritites Partnership . National priorities and goals: aligning our efforts to transform America's healthcare. Washington, DC: National Quality Forum; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bodenheimer T, Wang MC, Rundall TG, Shortell SM, Gillies RR, Oswald N, et al. What are the facilitators and barriers in physician organizations' use of care management processes? Jt Comm J Qual Saf. 2004;30(9):505–514. doi: 10.1016/s1549-3741(04)30059-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.The High Concentration of U.S. Health Care Expenditures. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Research in Action. 2009 (Issue 19).

- 19.Pham HH, O'Malley AS, Bach PB, Saiontz-Martinez C, Schrag D. Primary care physicians' links to other physicians through Medicare patients: the scope of care coordination. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(4):236–242. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-4-200902170-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dejesus RS, Vickers KS, Stroebel RJ, Cha SS. Primary care patient and provider preferences for diabetes care managers. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2010;4:181–186. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S8342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dejesus RS, Vickers KS, Howell LA, Stroebel RJ. Qualities of care managers in chronic disease management: patients and providers' expectations. Prim Care Diabetes. 2012;6(3):235–239. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilcox AB, Dorr DA, Burns L, Jones S, Poll J, Bunker C. Physician perspectives of nurse care management located in primary care clinics. Care Manag J. 2007;8(2):58–63. doi: 10.1891/152109807780845573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ercan-Fang N, Gujral K, Greer N, Ishani A. Providers' perspective on diabetes case management: a descriptive study. Am J Manage Care. 2013;19(1):29–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Quality measures and performance standards. http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/sharedsavingsprogram/Quality_Measures_Standards.html. Accessed November 19 2014.

- 25.NCQA. HEDIS and Quality Measurement: HEDIS 2014. http://www.ncqa.org/HEDISQualityMeasurement/HEDISMeasures/HEDIS2014.aspx. Accessed November 19 2014.

- 26.Cooper LA, Boulware LE, Miller ER, 3rd, Golden SH, Carson KA, Noronha G, et al. Creating a transdisciplinary research center to reduce cardiovascular health disparities in Baltimore, Maryland: lessons learned. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(11):e26–e38. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cooper LA, Marsteller JA, Noronha GJ, Flynn SJ, Carson KA, Boonyasai RT, et al. A multi-level system quality improvement intervention to reduce racial disparities in hypertension care and control: study protocol. Implement Sci : IS. 2013;8:60. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Charmaz K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA.: Sage Publications; 2006.

- 29.The Coding Process and Its Challenges. The SAGE Handbook of Grounded Theory. SAGE Publications Ltd. London, England: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- 30.Glaser BG. The constant comparative method of qualitative analysis. Soc Probl. 1965;12(4):436–445. doi: 10.2307/798843. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Giacomini MK, Cook DJ. Users' guides to the medical literature: XXIII. Qualitative research in health care B. What are the results and how do they help me care for my patients? Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. J Am Med Assoc. 2000;284(4):478–482. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.4.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schoen C, Osborn R, Doty MM, Squires D, Peugh J, Applebaum S. A survey of primary care physicians in eleven countries, 2009: perspectives on care, costs, and experiences. Health Aff. 2009;28(6):w1171–w1183. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.6.w1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Waters TM, Budetti PP, Reynolds KS, Gillies RR, Zuckerman HS, Alexander JA, et al. Factors associated with physician involvement in care management. Med Care. 2001;39(7 Suppl 1):I79–I91. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200107001-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nutting PA, Miller WL, Crabtree BF, Jaen CR, Stewart EE, Stange KC. Initial lessons from the first national demonstration project on practice transformation to a patient-centered medical home. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(3):254–260. doi: 10.1370/afm.1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rittenhouse DR, Shortell SM. The patient-centered medical home: will it stand the test of health reform? J Am Med Assoc. 2009;301(19):2038–2040. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Craig C ED, Whittington J. Care coordination model: better care at lower cost for people with multiple health and social needs. IHI innovation series white paper. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. 2011.

- 37.McDonald KM, Schultz E, Albin L, et al. Care Coordination Atlas Version 3. AHRQ Publication No. 11-0023-EF. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Antonelli RC, McAllister J, Popp J. Making care coordination a critical component of the pediatric healthcare system: a multidisciplinary framework. New York: The Commonwealth Fund; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wagner EH, Austin BT, Davis C, Hindmarsh M, Schaefer J, Bonomi A. Improving chronic illness care: translating evidence into action. Health Aff. 2001;20(6):64–78. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.6.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bennett HD, Coleman EA, Parry C, Bodenheimer T, Chen EH. Health coaching for patients with chronic illness. Fam Pract Manag. 2010;17(5):24–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parry C, Coleman EA, Smith JD, Frank J, Kramer AM. The care transitions intervention: a patient-centered approach to ensuring effective transfers between sites of geriatric care. Home Health Care Serv Q. 2003;22(3):1–17. doi: 10.1300/J027v22n03_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McDonald KM, Schultz E, Albin L, et al. Care Coordination Atlas Version 3 (Prepared by Stanford University under subcontract to Battelle on Contract No. 290040020). AHRQ Publication No. 110023EF. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hudon C, Fortin M, Haggerty J, Loignon C, Lambert M, Poitras ME. Patient-centered care in chronic disease management: a thematic analysis of the literature in family medicine. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;88(2):170–176. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Re F. Paradigms, praxis, problems, and promise: grounded theory in counseling psychology research. J Couns Psychol. 2005;52(2):156–166. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.52.2.156. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Doty MM, Fryer AK, Audet AM. The role of care coordinators in improving care coordination: the patient's perspective. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(7):587–588. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cooper HC, Booth K, Gill G. Patients' perspectives on diabetes health care education. Health Educ Res. 2003;18(2):191–206. doi: 10.1093/her/18.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Holman H, Lorig K. Patients as partners in managing chronic disease. Partnership is a prerequisite for effective and efficient health care. BMJ. 2000;320(7234):526–527. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7234.526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fleming B, Silver A, Ocepek-Welikson K, Keller D. The relationship between organizational systems and clinical quality in diabetes care. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10(12):934–944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Si D, Bailie R, Connors C, Dowden M, Stewart A, Robinson G, et al. Assessing health centre systems for guiding improvement in diabetes care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2005;5:56. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-5-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sperl-Hillen JM, Solberg LI, Hroscikoski MC, Crain AL, Engebretson KI, O'Connor PJ. Do all components of the chronic care model contribute equally to quality improvement? Jt Comm J Qual Saf. 2004;30(6):303–309. doi: 10.1016/s1549-3741(04)30034-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ouwens M, Wollersheim H, Hermens R, Hulscher M, Grol R. Integrated care programmes for chronically ill patients: a review of systematic reviews. Int J Qual Health Care : J Int Soc Qual Health Care / ISQua. 2005;17(2):141–146. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzi016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]