Over the last 40 years, the United States has experienced an “epidemic” of incarceration, in which millions of Americans have spent days to years of their lives in jails or prisons. During this time, correctional medicine has undergone major changes.1,2 In 1976, the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed that failure to provide basic medical care to a prisoner violates the Eighth Amendment to the Constitution banning cruel and unusual punishment.3 Over the ensuing decades, additional litigation or threat of litigation has forced correctional institutions to provide a minimum community standard of healthcare to prisoners. In response, accreditation bodies such as the National Commission on Correctional Health Care have codified these minimum standards for prison and jail-based health systems to follow through voluntary accreditation. However, a minority of the 4,575 correctional institutions across the U.S. have volunteered to become accredited using these standards. As a result, litigation remains the mainstay of enforcing correctional healthcare standards,4 and correctional healthcare improvements have transpired piecemeal, typically with a focus only on reaching the minimum standards that have been established.

While meeting minimum standards is critical in protecting against Eighth Amendment violations, we argue that higher standards in correctional healthcare are capable of improving individual and public health while controlling overall costs. With 2.2 million Americans behind bars, and 10 million cycling through correctional systems each year,5 U.S. correctional healthcare has provided medical care to 1 in 30 living American adults, the majority of whom are from impoverished communities, where poor healthcare access is the norm.6–10 Since more than 95% of prisoners eventually return to the community, correctional healthcare has the opportunity, and the obligation, to transform care for persons and communities most in need.11 Moreover, given that incarcerated populations are disproportionately from traditionally underserved and/or disadvantaged backgrounds and have a high burden of disease, these goals also hold the promise of reducing health disparities.6,8,12

We delineate three areas—screening and treatment for hepatitis C, improved mental health care, including treatment for addiction disorders, and attention to geriatric care—that exemplify the critical need for proactive, evidence-based correctional healthcare that reaches beyond minimum standards and integrates prisoner healthcare into mainstream medicine in order to improve the health of individuals and communities.

HEPATITIS C

When the hepatitis C epidemic was first recognized in U.S. correctional facilities in the late 1990s, 12–35% of prisoners were already infected.13 Facing treatment options that were poorly tolerated, costly, and minimally effective, correctional medicine programs were quickly overwhelmed. As the epidemic spread and mortality rates increased, inmate litigation contributed to the establishment of minimum standards for hepatitis C screening and treatment.13–15

In the years since those initial guidelines were established, treatments have evolved. Short-course, easily tolerated, highly curative (albeit expensive) treatments have arrived.16,17 The availability of these new treatments is critical, as complications in long-term hepatitis C infection (liver failure, hepatocellular carcinoma, and mortality) are rising dramatically, and are expected to continue to rise.18 Since the prisoner population has a high burden of hepatitis C, and because most prisoners will eventually return to our communities, successful treatment options in the criminal justice system could have a tremendous impact on public health at large (Figs. 1, 2, 3, and 4).

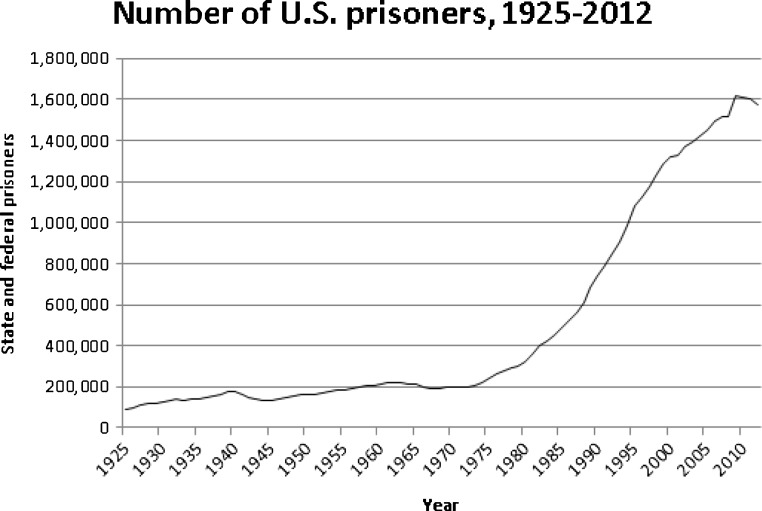

Figure 1.

Number of U.S. Prisoners, 1925–2012. Data source: U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics. Number of people incarcerated in U.S. prisons by year (does not include people in jails)

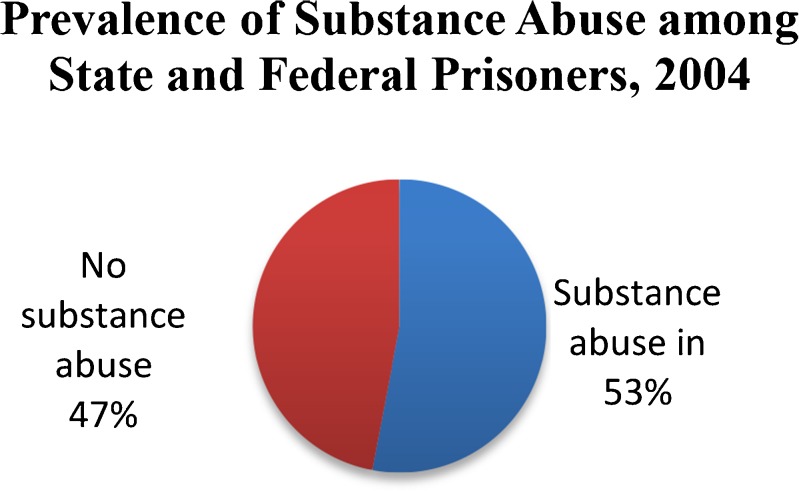

Figure 2.

Prevalence of Substance Abuse among State and Federal Prisoners, 2004.33 Data source: Mumola CKJ. Drug Use and Dependence, State and Federal Prisoners, 2004. Special Report. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics, U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs. Oct 2006. NCJ 213530.

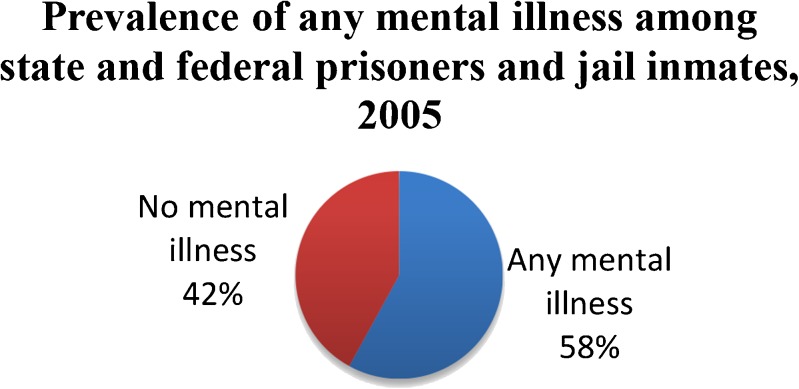

Figure 3.

Prevalence of Any Mental Illness among State and Federal Prisoners and Jail Inmates, 2005. Source: James DGL. Mental Health Problems of Prison and Jail Inmates. Special Report. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics, U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs. Sept 2006. NCJ 213600.

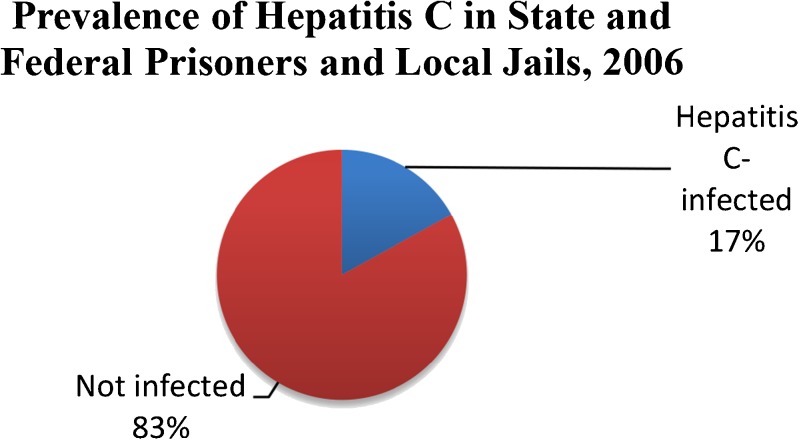

Figure 4.

Prevalence of Hepatitis C in State and Federal Prisoners and Jail Inmates, 2006. Data source: Varan AK, Mercer DW, Stein MS, Spaulding AC. Hepatitis C seroprevalence among prison inmates since 2001: still high but declining. Public Health Reports (Washington, DC : 1974). 2014;129(2):187–95.

Yet prisons and jails are not being mandated to provide this life-saving treatment. The prohibitive expense of treatment limits, and sometimes precludes, screening for and treating hepatitis C, both behind bars and in the community. Undoubtedly, this cost impediment to treatment will need to be addressed, perhaps through a state or federal carve-out funding mechanism that allows for bulk purchasing.17 Once this issue is addressed, since over 30% of all persons with hepatitis C are incarcerated at some point, correctional healthcare should be held to a standard that exceeds community standards,19 including surveillance and treatment for willing patients in order to stem the epidemic and to improve our public health, both inside and outside correctional institutions. With such a high density of infection, correctional medicine can set the standard for population-based hepatitis C treatment.

ADDICTION AND MENTAL HEALTH DISORDERS

Inadequate community treatment of addiction and mental health disorders often contributes to behaviors that lead to incarceration, suggesting that, in most cases, basic community standards for treatment of addiction disorders have already failed for prisoners. In prisons and jails, however, even minimum community standards are often not met.20 The prevalence of mental illness in prisons is roughly 50 %, compared to approximately 10 % in the community, and 28 % to 52 % of Americans with serious mental illness have been arrested at least once.20,21

Dual diagnosis of addiction and mental illness is common in prisoners. Over 70% of prisoners with mental illness report regular drug or alcohol use in the month prior to incarceration.21 Both conditions are clinically challenging, yet both are treatable. Incarceration provides a period of relative sobriety and structure, and thus an opportunity for therapeutic intervention. While more research into effective mental health and substance abuse interventions in correctional settings is needed, evidence supports the efficacy of therapeutic treatment during incarceration, as well as linkage and support for individuals transitioning back into the community.22–24

RESPONDING TO CHANGING DEMOGRAPHICS—GERIATRIC CARE

The number of older prisoners is growing rapidly, with many incarcerated under “mandatory minimums”, “three strikes,” and similar laws, serving long sentences with limited prospects of early parole.25 As a result, nearly 1 in 10 prisoners is 55 years of age or older, and an additional 3 in 10 are aged 40–55.26 Prisoners, on average, experience a higher burden of chronic disease and disability at younger ages than non-incarcerated populations.27 Absent a major shift in criminal justice policy, this aging demographic will continue to drive prison-based healthcare utilization and costs even higher.25,28

Conditions commonly associated with advancing age—multimorbidity, sensory impairment, disability, dementia, and end-of-life care—present unique challenges in the correctional environment, and can lead to worsening health, increased vulnerability to injury or victimization, and increased healthcare utilization and cost. As community-based efforts have shown, achieving a higher standard of geriatric care for older adults and quality palliative care that begins early in the course of a serious illness can both improve outcomes and lower costs.29

But adapting these standards to prisons requires recognition of the unique correctional environment. Many institutions are designed for younger inmates, and require complex physical tasks such as climbing onto top bunks and walking long distances for meals.28,30,31 Barriers to palliative care can include limited visitor policies, restricted opioid-prescribing practices, and mistrust between patients and clinicians. Moreover, compared to prisoners aged 18–44, those 55 years and older have twice the rate of accident-related mortality in prisons and are three times more likely to be victims of homicide.32 A new approach to geriatric care for incarcerated populations, one that moves beyond community standard care and acknowledges the unique correctional environment and the inherent risks posed to older adults, is needed in order to optimize function, improve safety, and minimize end-of-life suffering in this rapidly growing population.

CONCLUSIONS

Correctional healthcare systems have a significant but often overlooked impact on individuals and communities. Better healthcare during incarceration and a smooth transition back to community-based healthcare after release can engender lasting health benefits for former prisoners and communities.

Incorporating the highest standards of community healthcare into the correctional setting—and even exceeding those standards—is critical, and failure to accomplish this could lead to increased healthcare costs, both in correctional systems and within our communities. These include costs related to avoidable complications of hepatitis C, higher recidivism and acute care utilization due to undertreated mental health and addiction disorders, and higher healthcare costs and avoidable functional decline in a rapidly aging population. We propose three specific examples where aiming higher than minimum community standards in correctional healthcare could have a clinically significant effect on both individual and public health:

Aggressively diagnosing and treating patients with hepatitis C in the criminal justice system in order to stem the rapidly growing burden of disease and death. This will require additional resources and incentives, ideally similar to what the Ryan White Care Act has done to address the HIV epidemic.17

Increasing the emphasis on proven and effective medical and behavioral treatment for mental health and addiction disorders, including earlier intervention and diversion to more appropriate care settings, as well as better transitional services for those leaving correctional settings.

Introducing evidence-based geriatric and palliative care standards that are adapted to the correctional environment and are designed to minimize victimization and injury, improve trajectories of disability by addressing environmental risk factors, and reduce avoidable suffering for those with serious and life-limiting illness.

We live in an era of mass incarceration. Although public policies leading to this phenomenon have been neither endorsed nor recommended by the medical community, many have served as silent endorsers by failing to advocate for an integrated public health approach to correctional and community healthcare. A new, evidence-based, integrated approach to correctional healthcare that is consistent with the best interests of patients and sound public policy can improve public health and preserve public resources. The first step towards realizing this goal is identifying instances in which reaching beyond the community standard of care is needed to improve the health of our prisoners and our public. The second is medical community engagement with policymakers, advocates, and others to develop and implement systems to support these initiatives with built-in oversight. Failure to improve correctional healthcare puts a strain on community-based healthcare systems, adversely affects public health, and squanders the constitutionally mandated investments we have made in prisoner health.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Rich is supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (K24DA022112) and the National Institute on Allergy and Infectious Diseases (P30A142853). Dr. Williams is an employee of the Department of Veterans Affairs and is supported by the National Institute on Aging (K23AG033102), The Jacob & Valeria Langeloth Foundation, the UCSF Program for the Aging Century, and the UCSF Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center. Dr. Rich participated in a single meeting of the Gilead advisory board in 2012 and is a stockholder in Alkermes. Drs. Rich, Allen, and Williams have all offered expert testimony in cases (12 cumulatively) involving the health care of prisoners. The opinions expressed in this manuscript may not represent those of the supporting agencies.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. These funding sources had no role in the design, conduct, or analysis of the study or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rich JD, Wakeman SE, Dickman SL. Medicine and the epidemic of incarceration in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(22):2081–2083. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1102385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Health and Incarceration: A Workshop Summary: The National Academies Press; 2013. [PubMed]

- 3.Gamble Ev. Supreme Court of United States, 429 U.S. 97 Sess. 1976.

- 4.Rold WJ. Thirty Years After Estelle v. Gamble: A Legal Retrospective. J Correct Health Care. 2007;14(1):11–20. doi: 10.1177/1078345807309616. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spaulding AC, Seals RM, Page MJ, Brzozowski AK, Rhodes W, Hammett TM. HIV/AIDS among inmates of and releasees from US correctional facilities, 2006: declining share of epidemic but persistent public health opportunity. PLoS One. 2009;4(11):e7558. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carson EA, Golinelli, D. Prisoners in 2012 - Advance Counts. Bureau of Justice Statistics, U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs. July 2013. NCJ 242467.

- 7.Bonczar TP. Prevalence of Imprisonment in the U.S. Population, 1974–2001. Washington, D.C.: Bureau of Justice Statistics, U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs. August 2003. NCJ 197976.

- 8.Binswanger IA, Redmond N, Steiner JF, Hicks LS. Health disparities and the criminal justice system: an agenda for further research and action. J Urban Health Bull New York Acad Med. 2012;89(1):98–107. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9614-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Western B. Mass Imprisonment and Economic Inequality. Soc Res. 2007;74:509–532. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greifinger R. Public health behind Bars: from prisons to communities. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company; 2007.

- 11.Hughes T, Wilson, D.J. Reentry Trends in the United States. Bureau of Justice Statistics, U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs. 2004.

- 12.Dumont DM, Brockmann B, Dickman S, Alexander N, Rich JD. Public health and the epidemic of incarceration. Annu Rev Public Health. 2012;33:325–339. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031811-124614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weinbaum C, Lyerla R, Margolis HS. Prevention and control of infections with hepatitis viruses in correctional settings. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR Recomm Rep Morb Mortal Wkly Rep Recomm Rep/Center Dis Control. 2003;52(Rr-1):1–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gough E, Kempf MC, Graham L, et al. HIV and hepatitis B and C incidence rates in US correctional populations and high risk groups: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:777. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harzke AJ, Baillargeon JG, Kelley MF, Diamond PM, Goodman KJ, Paar DP. HCV-related mortality among male prison inmates in Texas, 1994–2003. Ann Epidemiol. 2009;19(8):582–589. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spaulding AS, Kim AY, Harzke AJ, et al. Impact of new therapeutics for hepatitis C virus infection in incarcerated populations. Top Antiviral Med. 2013;21(1):27–35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rich JD, Allen SA, Williams BA. Responding to hepatitis C through the criminal justice system. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(20):1871–1874. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1311941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghany MG, Strader DB, Thomas DL, Seeff LB. Diagnosis, management, and treatment of hepatitis C: an update. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md) 2009;49(4):1335–1374. doi: 10.1002/hep.22759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Varan AK, Mercer DW, Stein MS, Spaulding AC. Hepatitis C seroprevalence among prison inmates since 2001: still high but declining. Public Health Rep (Washington, DC 1974) 2014;129(2):187–195. doi: 10.1177/003335491412900213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fontanarosa J, Uhl S, Oyesanmi O, Schoelles KM. Interventions for Adult Offenders with Serious Mental Illness. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Center EIE-bP; 2013 AHRQ Publication No. 13-EHC107-EF. [PubMed]

- 21.James DGL. Mental Health Problems of Prison and Jail Inmates. Special Report. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics, U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs. Sept 2006. NCJ 213600.

- 22.Hills H, Siegfried C, Ickowitz A. Effective Prison Mental Health Services: Guidelines to Expand and Improve Treatment. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Corrections. May 2004. NIC Accession Number 018604.

- 23.Binswanger IA, Stern MF, Deyo RA, et al. Release from prison—a high risk of death for former inmates. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(2):157–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Wang EA, Wang Y, Krumholz HM. A high risk of hospitalization following release from correctional facilities in Medicare beneficiaries: a retrospective matched cohort study, 2002 to 2010. JAMA Int Med. 2013;173(17):1621–1628. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.9008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williams BA, Stern MF, Mellow J, Safer M, Greifinger RB. Aging in correctional custody: setting a policy agenda for older prisoner health care. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(8):1475–1481. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carson EA, Sabol, W.J. Prisoners in 2011. Bureau of Justice Statistics, U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs. 2012. NCJ 239808.

- 27.Binswanger IA, Krueger PM, Steiner JF. Prevalence of chronic medical conditions among jail and prison inmates in the USA compared with the general population. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2009;63(11):912–919. doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.090662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ahalt C, Trestman RL, Rich JD, Greifinger RB, Williams BA. Paying the price: the pressing need for quality, cost, and outcomes data to improve correctional health care for older prisoners. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(11):2013–2019. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morrison RS, Penrod JD, Cassel JB, et al. Cost savings associated with US hospital palliative care consultation programs. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(16):1783–1790. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.16.1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williams BA, Goodwin JS, Baillargeon J, Ahalt C, Walter LC. Addressing the aging crisis in U.S. criminal justice health care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(6):1150–1156. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03962.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Old Behind Bars: The Aging Prison Population in the United States. Human Rights Watch, 2012.

- 32.Noonan ME GS. Mortality in Local Jails and State Prisons, 2000–2011 - Statistical Tables. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics. 2013. NCJ 242186.

- 33.Mumola CKJ. Drug Use and Dependence, State and Federal Prisoners, 2004. Special Report. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics, U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs. Oct 2006. NCJ 213530.