Abstract

A bedside toxicology consult service may improve clinical care, facilitate patient clearance and disposition, and result in potential cost savings for poisoning exposures. Despite this, there is scant data regarding economic feasibility for such a service. Previously published information suggests low hourly reimbursement at approximately $26.00/h at the bedside for toxicology consultations. A bedside toxicology consultant service was initiated in 2011. Coverage was available 24 h a day for 50 out of 52 weeks. Bedside rounding on toxicology consult patients was available 6/7 days per week. The practice is associated with >800 bed teaching institution in a large upstate NY region with elements of urban and suburban practice. Demographic and billing data was collected for all patients consulted upon from July 1, 2011 to June 31, 2012. In charges of $514,941 were generated during the period of data collection. Monthly average was $42,912. Net reimbursement of charges was 29 % of overall charges at $147,792. In terms of total encounters, net collection rate in which something was reimbursed or “paid” against charges for that encounter was 82.6 % of all encounters at 999/1,210. Average encounter time for inpatients, including critical care, was 1.05 h, and the average time spent for outpatients was 1.18 h. Reimbursement rates appear higher than previously reported. Revenue generated from reimbursement from toxicology consultation can result in recouping a substantial portion of a toxicologist’s salary or potentially fund fellowship positions and salaries or toxicology division infrastructure.

Keywords: Toxicology, Billing, Charges, Reimbursement, Compensation

Background

Poisoning characteristics have changed in the 30-year history that the American Association of Poison Control Centers (AAPCC) has published an annual report. Whereas children have previously represented over two thirds of poisoning cases, the mix is now evenly split between children under 6 years and adolescents, teens, and adults as calls related to drug abuse have climbed [1]. Intentional self-poisoning rates have doubled during this 30-year period [2]. There are now over 350,000 exposure calls related to suicide attempts and drug and alcohol abuse annually [1; 2]. Cases have also become more complex with a higher percentage of exposure calls resulting in hospitalization than in previous years [2]. While physicians, in particular those who are emergency medicine trained, have a wide body of toxicological knowledge [3], there has been a demonstrated benefit for the use and availability of dedicated medical toxicology consultants and poison control centers in the treatment of poisonings [4–7]. This relates to improvements in patient care and cost savings driven by decreases in overall length of stay and decreases in overall hospital charges, particularly for the most medically complex and sickest of the poisoned patients [4–9]. Improvements in the management of poisonings as well as facilitation of clearance in less toxic patients are some of the factors driving these reductions in stay and cost savings [6].

There are several things that influence the complexity of care in poisoned patients including increasing complexity of general medical comorbidities, an aging population and potential interaction, and adverse effects from multiple prescription and non-prescription medications taken at the same time. Add to this the recent and dramatic increases in rates of prescription, over-the-counter and illicit drug abuse, rising rates of heroin availability and abuse, and the changing availability and types of novel and designer drug products such as synthetic cannabinoids, cathinones or “bath salts” and other natural or designer psychoactive substances, and it becomes clear that there is a need for the availability and expertise of fellowship-trained and board-certified medical toxicologists within health care. These issues have contributed to the development of ACGME accredited, specialized medical toxicology training and fellowship programs [3]. Despite the enhanced training and notable necessity, very little research or reporting has been conducted in the literature that describes the financial positioning of a toxicology service within health-care organizations [10]. Those that have provided some insight into this have predominantly focused on clinical care rather than actual financial feasibility [11]. In fact, many medical toxicologists are noted to work only part time within medical toxicology [3] and this may be partially due to financial and reimbursement concerns within the medical financial climate. Patient care notwithstanding, the current economic climate of medicine creates a series of concerns regarding the financial viability of any medical service within an organization, including consultant toxicology services. Considerable further research needs to be conducted in order to document the economic viability of a bedside consultant medical toxicology service.

Although the specifics of economic and financial viability of any enterprise can be measured in multiple ways and by multiple methods, the basic premise of financial success can be simplified into consideration of two basic components: revenue generation and costs/cost containment. Both components are simple in broad concept: Revenue generation includes monetary payments received for goods or services rendered. Costs are those financial resources expended in the course of providing the goods or services in question. Cost containment is the process of reducing the financial expenditures required to provide goods and services by any number of methods.

There is considerable agreement about the definitions of these concepts, but it is also widely recognized that defining and collecting data and accurately measuring variables associated with them is far more difficult [12]. As an example within health care, hospital charges which are typically easy to capture, are usually greater than the actual reimbursement received for health care and hospital services which is usually measured in rolling fashion and far more difficult to measure in real time. Reimbursements in turn are typically discrepant from the actual costs [12]. Competition within local, regional, and state health-care systems makes true costs for any organization or region very difficult to assess given that much of this information and various specific contracts are closely held and sensitive to each facility and organization. Furthermore, the payments for a given region may vary widely and may be heavily influenced by a variety of different factors that may be difficult to categorize, including payer mix, hospital billing contracts, and physician-specific factors [13]. Additionally, there is potentially a great deal of overlap between professional fees provided to physicians themselves and “facilities” fees paid to the organizations and institutions that they operate within, which can make true and accurate economic analysis elusive. Lastly, there are opportunity costs and opportunity cost savings that can be difficult to capture, such as the true economic savings of a reduction in length of patient stay or early clearance from a busy emergency department or intensive care unit.

Regardless of the difficulties with accurate analysis, we must continually strive to understand and describe the economic climate and variables within health care as they pertain to revenue, reimbursements, and costs. Given the benefit to patient care of toxicology and medical toxicology services, coupled with the paucity of published literature describing the economics of consultant toxicology [10], we seek to describe our economic experience with a medical toxicology consultant service in a large urban academic tertiary care center.

Methods

This was a descriptive study that was conducted after IRB approval. A bedside toxicology consultant service was initiated on January 1st of 2011. The service was provided by a single board-certified toxicologist employed by the hospital, with coverage available 24 h a day by phone with bedside availability during daytime hours unless emergent consultation overnight was requested. This service was available for approximately 50 out of 52 weeks, with 46 of those with on-site availability as well as telephone contact, and four of those with availability only by telephone. Bedside rounding on toxicology consult patients was available 6/7 days per week. The practice had been established on January 1, 2011 which was the day after the formal closing of the on-site poison center (The Ruth Lawrence Poison & Drug Information Center) and is associated with >800 bed teaching hospital in a large upstate NY region with elements of both urban and suburban practice. Demographic and billing data were collected, mainly for quality assurance purposes, for all patients who were consulted upon by the service for the period of time from July 1, 2011 to June 31, 2012—the institutional fiscal year. This data included Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) and Evaluation and Management (E&M) code associated information. Information regarding the individual consultation encounter times was recorded in the consult notes during clinical care and used to assign the appropriate CPT codes. Time and complexity-based encounters were used for billing, and the overall encounter times were calculated from this data. Additional data including demographic information, average charges, net revenue, total consult numbers, and payer breakdown was recorded. These are analyzed and described here.

Results

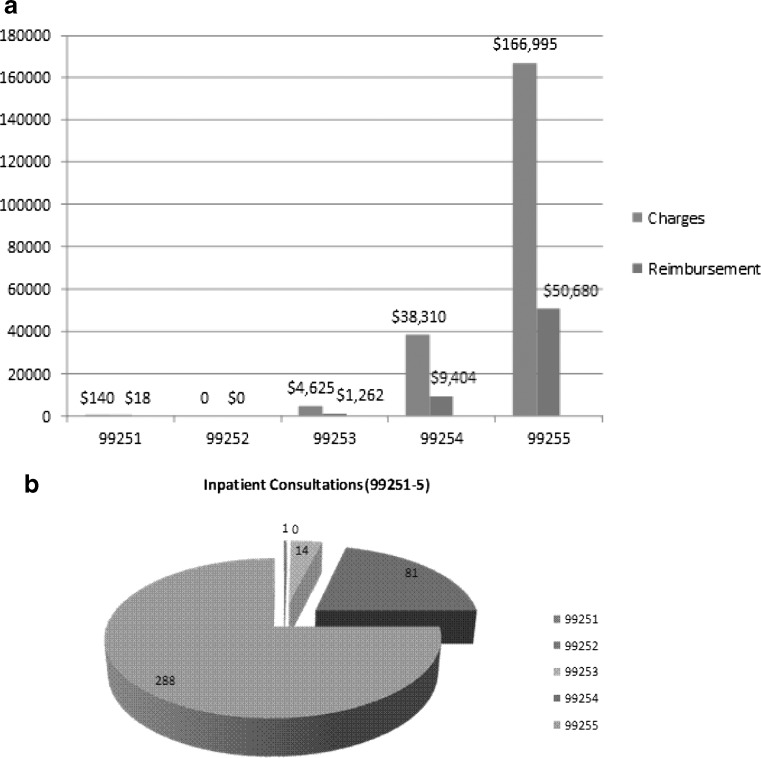

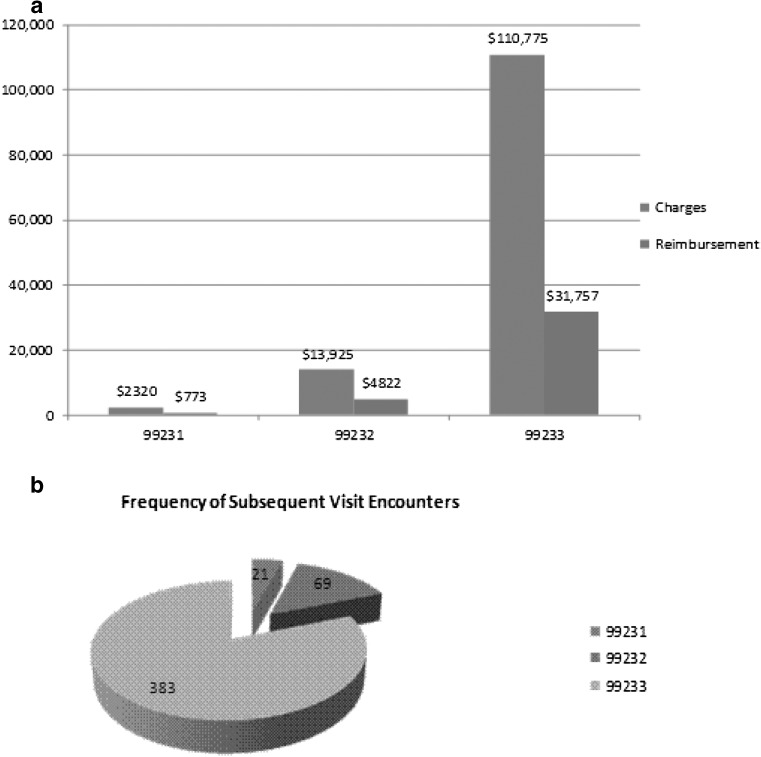

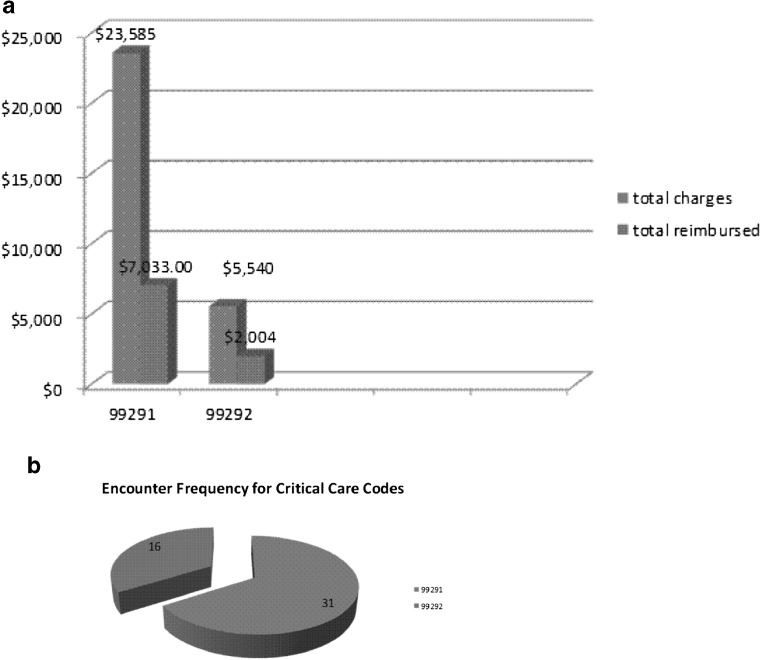

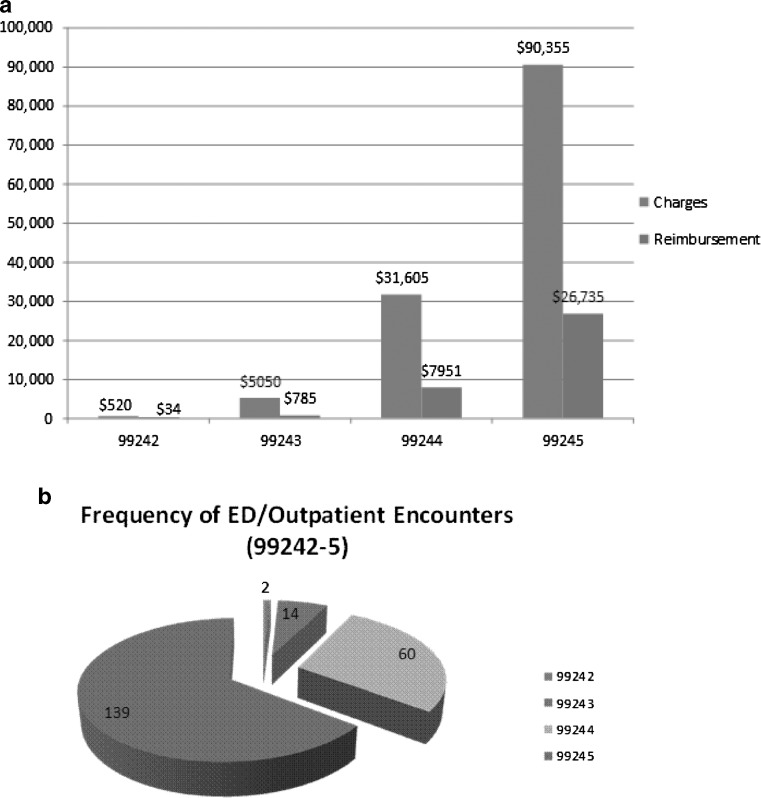

There were 1,210 total bedside encounters, with an average of 101 encounters per month. Figure 1 shows the monthly rates of consultation by encounter type for the 2011–2012 fiscal year. Figure 1 includes initial encounters, subsequent visits, critical care, and “other” types of encounters. On average, there were 80 inpatient consults and 18 outpatient emergency department (ED) consults per month. Critical care consults averaged four per month out of the 80 inpatient encounter/month total. Total consultations included 384 inpatient [E&M code 9925(1–5)], 215 outpatient [E&M 9924(1–5)], 473 subsequent visits [E&M code 9923(1–5)], 47 critical care [E&M code 9929(1–2)], and 50 other (E&M code 99356 for prolonged services). A total of 41 additional encounters (representing services that occurred less than five times each during the year) were not included in the data analysis. Figures 2a, 3a, 4a, and 5a include the overall charges and reimbursement by specific encounter type for inpatient, outpatient, subsequent visit, and critical care consultation types. Figures 2b, 3b, 4b, and 5b provide the consultation frequency by level of complexity for the inpatient, outpatient, subsequent visit, and critical care encounters. There were 579 male and 631 female patients. The average age was 33 years of age (range <1–90).

Fig. 1.

Encounter types and frequency by month

Fig. 2.

a Initial inpatient (H&P) encounter (CPT 99251–5) charges and reimbursement; b frequency of inpatient H&P (99251–5) encounters

Fig. 3.

a Subsequent inpatient visit (99231–3) charge and reimbursement. b Frequency of subsequent visit encounters (99231–3)

Fig. 4.

a Critical care encounter (CPT 99291 and 99292) charges and reimbursement. b Frequency of critical care encounters (99291–2)

Fig. 5.

a Emergency department “outpatient” encounter (99242–5) charges and reimbursement. b Frequency of emergency department and outpatient encounters (99242–5)

The top 5 inpatient diagnoses by frequency were coma (232), tachycardia NOS (146), poisoning from an aromatic analgesic (142), suicide attempt (analgesic) (118), and suicide attempt (psychotropic agents) (108). The top 5 outpatient (non-clinic ED/outpatient) diagnosis included other alterations of consciousness (35), suicide attempt (psychotropic agent) (29), tachycardia NOS (29), poisoning (benzodiazepines) (20), and suicide attempt (analgesics) (18). Most of the inpatient, outpatient, and critical care encounters carried multiple diagnosis codes. Tables 1 and 2 contain the top 10 ICD-9 diagnosis codes for inpatient and outpatient encounters, respectively. CPT codes are a set of medical codes maintained by the American Medical Association (AMA) that describe medical, surgical, or diagnostic services and allow for communication and uniformity related to medical services and procedures among physicians, coders, accreditation groups, and payers. Table 3 gives a brief description of each CPT code. Table 4 gives the basic payer mix by percentage for the total patient population seen. For inpatient consults, 59 % of patients had private third party insurance with the remaining 41 % being either Medicaid, Medicare, or self-pay. For outpatient consults, 72 % were covered by third party insurance with the remaining 28 % insured by Medicaid, Medicare, or self-pay. Table 5 provides a comparison of per case allowance using an example of private insurance (Excellus—a regional Blue Cross/Blue Shield provider) Medicaid and the average without Medicaid for some of the most common CPT codes.

Table 1.

Top 10 inpatient diagnoses by frequency

| ICD-9 | Description | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| 780.01 | Coma | 232 |

| 785.0 | Tachycardia NOS | 146 |

| 965.4 | Poisoning—arom analgesics NEC | 142 |

| E950.0 | Suicide analgesics | 118 |

| E950.3 | Suicide—psychotropic agent | 108 |

| E950.4 | Suicide—drug/med NEC | 92 |

| 518.81 | Acute respiratory failure | 83 |

| 781.0 | Abnl involuntary movement | 78 |

| 333.99 | Extrapyramidal dis NEC | 74 |

| 780.39 | Convulsions | 71 |

Table 2.

Top 10 outpatient diagnoses by frequency

| ICD-9 | Description | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| 780.09 | Other alteration of consciousness | 35 |

| E950.3 | Suicide—psychotropic agent | 29 |

| 785.0 | Tachycardia NOS | 29 |

| 969.4 | Poison—benzodiazepine | 20 |

| E950.0 | Suicide—analgesics | 18 |

| 780.01 | Coma | 18 |

| 969.3 | Poison—antipsychotic NEC | 16 |

| 965.09 | Poisoning—opiates NEC | 16 |

| E950.4 | Suicide—drug/med NEC | 15 |

| 780.1 | Hallucinations | 14 |

Table 3.

CPT codes and basic description

| CPT code outpatient | Description | CPT code inpatient | Description | CPT code crit. care | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 99241 | Office visit new/prior patient | 99251 | Inpt. consult new/prior pt. | 99291 | Crit. care—30–74 min |

| Problem focused—15 min | Problem focused—20 min | ||||

| 99242 | Office visit new/prior patient | 99252 | Inpt. consult new/prior pt. | 99292 | Crit. Care—each add. 30 min |

| Expanded problem list 30 min | Expanded problem focused-40 min | ||||

| 99243 | Office visit new/prior patient | 99253 | Inpt. consult new/prior pt. | ||

| Detailed history/exam 40 min | Detailed history/exam-55 min | ||||

| 99244 | Office visit new/prior patient | 99254 | Inpt. consult new/prior pt. | ||

| Detailed history/exam 60 min | Detailed history/exam—80 min | ||||

| 99245 | Office visit new/prior patient | 99255 | Inpt. consult new/prior pt. | ||

| Complete history/exam 80 min | Complete history/exam 110 min | ||||

| 99211 | Office visit prior patient—5 min | 99231 | Inpt. f/u care—15 min | ||

| 99212 | Office visit prior patient—10 min | 99232 | Inpt. f/u care—25 min | ||

| 99213 | Office visit prior patient—15 min | 99233 | Inpt. f/u care—35 min | ||

| 99214 | Office visit prior patient—25 min | ||||

| 99215 | Office visit prior patient—40 min | ||||

| 99354 | Prolong office svc 1 h | ||||

| 99355 | Prolong office. svc add. 1/2 h |

Table 4.

Payer Mix

| Insurance/payer type | FY 2011–2012 |

|---|---|

| Inpatient | Inpatient mix by % |

| Aetna | 1.78 |

| Blue Choice | 23.97 |

| Blue Shield | 18.16 |

| Commercial Ins. | 5.46 |

| Medicaid | 14.56 |

| Medicare | 8.86 |

| MVP | 9.38 |

| Self/patient | 15.51 |

| WC/MVA | 0.33 |

| Other | 1.99 |

| Outpatient | Outpatient mix by % |

| Aetna | 1.88 |

| Blue Choice | 27.15 |

| Blue Shield | 20.56 |

| Commercials Ins. | 5.95 |

| Medicaid | 11.48 |

| Medicare | 5.89 |

| MVP | 13.85 |

| Self/patient | 10.92 |

| WC/MVA | 2.32 |

| Other | 0.00 |

| Total | 100 |

Table 5.

CPT code breakdown of per case allowances (Excellus is a private insurer and regional BC/BS provider)

| CPT code | Description | Charges | Excellus allowed | Medicaid | Average without Medicaid |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 99245 | Outpatient (ED) level 5 (85 min) | 640.00 | 376.48 | 66.52 | 247.86 |

| 99255 | Inpatient level 5 (105 min) | 580.00 | 280.89 | 79.55 | 246.87 |

| 99231 | Inpatient f/u level 1 (15 min) | 115.00 | 56.00 | 14.57 | 51.62 |

| 99233 | Inpatient f/u level 3 (35 min) | 295.00 | 146.06 | 37.28 | 126.82 |

| 99291 | Critical care (each additional 30–74 min) | 780.00 | 319.18 | 83.83 | 277.84 |

| 99292 | Critical care (each additional 30 min) | 350.00 | 159.70 | NA | 139.16 |

| 99356 | Prolonged Service inpatient (first hour) | 260.00 | 127.22 | 33.56 | 138.41 |

There was $514,941 in overall charges generated through toxicology consultations in the time period of data collection (inpatient. $378,885; ED/outpatient, $129,140; other, $6,916). Monthly charge average was $42,912 (inpatient, $29,147; outpatient, $10,762). Figure 6 shows the monthly charges and reimbursement throughout the fiscal year 2011–2012. Net reimbursement of total charges was 29 % of overall charges at $147,792 [inpatient $112,076 (30 % of inpatient charges) and ED/outpatient $35,716 (28 % outpatient charges)]. Stated in terms of the total number of encounters, net collection rate in which something was reimbursed or “paid” against charges for that encounter was 82.6 % of all encounters at 999/1,210 (see Tables 6, 7, and 8 for grouped average charges and reimbursement per CPT code, per patient, and per hour results). The average time spent for inpatient encounters, including critical care, was 1.05 h per encounter, and the average time spent for outpatient encounters was 1.18 h per encounter. Other than Fig. 6, tables and totals do not include charges for procedures, medication administration, or other certain other infrequently used billable codes not included in the main body of the table (the 41 encounters not included in this analysis).

Fig. 6.

Overall charges and reimbursement by month including all procedures and the 41 encounter types/services that had been excluded from calculated rates

Table 6.

Major Inpt. CPT codes, times, and reimbursement averages and totals excluding critical care

| CPT | Total count | Total time spent for CPT in hours | Avg. charge/pt. in $ | Avg. reimb/pt. in $ | Ttl charges for CPT in $ | Ttl reimb. For CPT in $ | Chg/h per CPT | Reimb/h per CPT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 99251 | 1 | 0.3 | $140 | $18.77 | $140.00 | $18.77 | $466.6/h | $62.6/h |

| 99252 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 99253 | 14 | 12.8 | $330.36 | $90.12 | $4,625.00 | $1,261.70 | $361.3/h | $98.6/h |

| 99254 | 81 | 108 | $472.96 | $116.10 | $38,310.00 | $9,404.46 | $354.7/h | $87.1/h |

| 99255 | 288 | 528 | $579.84 | $175.97 | $166,995.00 | $50,679.53 | $316.3/h | $95.9/h |

| 99356 | 50 | 50 | $253.40 | $86.47 | $12,670.00 | $4,323.34 | $253.4/h | $86.5/h |

| 99231 | 21 | 5.25 | $147.27 | $36.80 | $2,320.00 | $772.88 | $441.9/h | $147.2/h |

| 99232 | 69 | 28.75 | $201.81 | $69.89 | $13,925.00 | $4,822.30 | $484.3/h | $167.7/h |

| 99233 | 383 | 223 | $289.23 | $82.92 | $110,775.00 | $31,757.00 | $496.7/h | $142.4/h |

| TTL | 907 | 956.1 | ||||||

| Avg. chg. and reimb./pt for all inpt. CPTs | Avg. chg. $385.62 per patient—all inpts | Avg. reimb. $113.6 per patient—all inpts | ||||||

| TTL chg. and reimb. for all CPTs | $349,760 | $103,040 | ||||||

| Avg. chg. and reimb./h for all CPTs | Avg. chrgs. $365.8/h—all inpt. CPTs | Avg. reimb. $107.8/h—all inpt. CPTs |

Table 7.

Major output, CPT codes, times, and reimbursement averages and totals excluding critical care

| CPT | Total count | Total time spent for CPT in hours | Avg. charge/pt. in $ | Avg. reimb/pt. in $ | Ttl charges for CPT in $ | Ttl reimb. for CPT in $ | Chg/h per CPT | Reimb./h per CPT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 99241 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 99242 | 2 | 1 | $260 | $17.15 | $520.00 | $34.30 | $520.0/h | $34.3/h |

| 99243 | 14 | 9.3 | $360.71 | $56.07 | $5,050.00 | $784.99 | $543.0/h | $84.4/h |

| 99244 | 60 | 60 | $526.75 | $132.51 | $31,605.00 | $7950.78 | $526.8/h | $132.5/h |

| 99245 | 139 | 185.3 | $650.04 | $192.34 | $90,355.00 | $26,735.09 | $487.6/h | $144.3/h |

| 99213 | 2 | .5 | $197.50 | $30.84 | $395.00 | $61.67 | $790.0/h | $123.3/h |

| 99215 | 1 | .67 | $405.00 | $105.52 | $405.00 | $105.52 | $604.5/h | $157.5/h |

| 99354 | 3 | 3 | $270.00 | $14.51 | $810.00 | $43.52 | $270.0/h | $14.6/h |

| TTL | 221 | 259.77 | ||||||

| Avg. chg. and reimb. /pt for all output CPTs | Avg. chrgs. $584.34 per patient—all output | Avg. reimb. $161.6 per patient—all output | ||||||

| TTL chg. and reimb. for all CPTs | $129,140 | $35,716 | ||||||

| Avg. chg. and reimb./h for all CPTs | Avg. chrg. $497.13/h—all output CPTs | Avg reimb. $137.49/h—all output CPTs |

Table 8.

Major critical care CPT codes, times, and reimbursement averages and totals

| CPT | Total count | Total time spent for CPT in hours | Avg. charge/pt. in $ | Avg. reimb./pt. in $ | Ttl charges for CPT in $ | Ttl reimb. For CPT in $ | Chg/h per CPT | Reimb./h per CPT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 99291 | 31 | 38 | $760.81 | $226.86 | $23,585.00 | $7,032.55 | $620.1/h | $185.1/h |

| 99292 | 16 | 16 | $346.25 | $125.25 | $5540.00 | $2,003.94 | $346.3/h | $125.2/h |

| TTL | 47 | 54 | ||||||

| Avg. chg. and reimb./pt for all output CPTs | Avg. chrgs $619.69 per CC pt | Avg. reimb. 192.26 per CC pt. | ||||||

| TTL chg. and reimb. for all CPTs | $29,125.00 | $9036.00 | Avg. chrg. $539.35/h—all CC pts. | Avg reimb. $167.33/h—all CC pts. |

Discussion

Medical toxicology evaluations have been reported to be extremely time-consuming with a mean time of 2.6 h for inpatient encounters and outpatient consults requiring up to 3.5 h [10]. Our average consult times, however, do not show the same time consumption with the average consult time of an inpatient consult requiring approximately 1.05 h per encounter. Average outpatient consult times for our service were slightly higher 1.18 h per encounter. Previous published data on toxicology reimbursement has also suggested very low levels for professional charges and reimbursement in toxicology consultations with an overall average charge and collection rate of $66.00 and $26.19 per hour, respectively, reported by Leikin using a mean evaluation time of 3 h per consultation [10].

Given our current payer mix, charge, and reimbursement amounts, as an average across all inpatient visits, we experienced a per patient average of $385.62 in charges and $113.6 per patient of reimbursed charges for inpatient consults. Averaged over all inpatient visits, on a per hour scale, our average inpatient charges were $365.8 per hour and $107.8 per hour respectively. The highest inpatient charge per patient for a given CPT code, excluding critical care time, was the 99255 code at $579.84 per patient with a reimbursed amount of $175.97 per patient, which was also the highest reimbursed amount per patient per inpatient CPT code.

However, when examined in terms of charges and reimbursement per hour by individual CPT code, the highest inpatient hourly charges were derived by the 99233CPT code (follow-up level 3 inpatient visit up to 35 min) at $496.7 per hour which only received a reimbursement of $142.4 per hour. The highest reimbursed amount, however, was the 99232 (follow-up level 2 inpatient visit up between 15 and 25 min) which was charged at $484.3 per hour—slightly less than the 99233 CPT—but reimbursed at $167.7 per hour, $25.00 more than the 10-min longer encounter.

In terms of outpatient visits, most of the “outpatient” toxicology encounters that occurred during this first fiscal year did not represent clinic patients, but rather, patients seen by the medical toxicology consultant attending in the emergency department and ultimately discharged from the ED or seen by the medical toxicology consultant prior to an “admit” order was entered by the emergency department attending physician. These outpatient definitions for billing purposes (99241–5) are thus based on timing of consultation rather than refer to traditional outpatient clinic practice (99211–5). In terms of charges and reimbursement for outpatient visits, for all outpatient CPT codes, our average charge per patient was $584.34 with an average per patient reimbursement of $161.6 per patient. Averaged over all outpatient codes, our average per hour charge was $497.13 with an average reimbursed amount of $137.49 per hour. Calculated individually by CPT code, the highest charges per patient were generated by the 99245 code (level 5 outpatient office consult up to 80 min) at $650.04 per patient which also resulted in the highest per patient reimbursement at $192.34 per patient.

In a similar fashion to the inpatient visits, on an hourly level, the highest outpatient per hour charge for a given outpatient CPT was the 99213 code (follow-up level 3 office visit up to 15 min) at $790 per hour, but this code was fourth in reimbursement hour to the 99215 (level 5 follow-up office consult up to 40 min) which generated $34.2 per hour more in reimbursed fees, but was charged out at $185.00 less. These actual clinic encounters (9921–5) represented a very small part of the toxicology consult service activity during the first fiscal year of service compared to other outpatient encounters and to overall toxicology encounters.

While other studies have found that the sickest patients received the lowest total reimbursement rate [10], we found that aggregate total average reimbursable amounts ranged from $107.8 per hour in the inpatient setting to $137.49 per hour for outpatient consults and $167.33 per hour for critical care-related consults, although rates varied dramatically by specific payer type including private, Medicaid, third party payer, and self-pay (see Table 5). Per patient, critical care consults allowed for the greatest total allowable reimbursement at $226.86 per 74 min consult followed by ED outpatient consults with a total allowable reimbursement at $192.34 per 80-min consult. This also held true for group averages with ICU consults resulting in the highest average reimbursement per patient at $192.26 and with ED and outpatient consults averaging $161.60 per patient. We note that the 99291 and 99245 codes (the two highest per patient reimbursement levels) had a per hour allowable reimbursement which was also better for the sick critical care consults at $185.1 per hour than the outpatient consults which were reimbursed at a rate of $144.25 per hour. The second highest per hour reimbursement was the 99232 CPT code at $167.7 per hour second to the ICU 99291 code.

The Society of Academic Emergency Medicine and Association of Academic Chairs in Emergency Medicine recently reported a mean academic Emergency Physician salary of $237,884 for 2009–2010 (mean ranging from $232,819 to $246,853 depending upon geographic region within the USA), and toxicology fellowship training was among the factors associated with a higher salary [14]. First year faculty in this survey had mean salaries of $204,833. Our total reimbursement numbers for medical toxicology-related professional fees bedside consultation alone suggest that if the average first year medical toxicologist salary was $204,833/year, our first year of medical toxicology practice professional fees alone would have covered approximately 76 % of a board-certified medical toxicologist’s salary. Furthermore, these figures do not represent the full context of the responsibilities or potential reimbursement or other income and benefit to the hospital or academic center that a board-certified medical toxicologist could bring including fees generated by addiction counseling, smoking cessation counseling, facilities fees, and revenue from consulting, honoraria, or poison center Medical Direction or coverage, nor do these figures take the protected FTE time into consideration for teaching and lecturing toxicology curricula, research revenue, medical toxicology fellowship or residency activities, or other academic and professional activities and responsibilities.

Our data also suggests that although reimbursement can be maximized on a per patient basis, there is an impact to the degree of time spent on each consultation. Our results support that time efficiency in a given consult encounter may be the most financially beneficial, but this clearly has to be weighed against the impact that may exist on patient care and needs to be further examined within each particular geographical and payer mix environment. Additionally, information that would allow for benchmarking and comparison to other fellowship-trained physicians with similar practice types (e.g., infectious disease) is needed.

Limitations

Charges and reimbursement were limited to a single academic center in Upstate New York and might not be applicable to all types of toxicology practice environments. Despite this, our payer mix was thought to be average in terms of reimbursement rates and insurance coverage with nearly 30 % of our population mix either Medicare, Medicaid, or self-pay. Certainly, some clinical settings would include a higher portion of self-pay or subsidized Medicaid/Medicare patients which would negatively influence reimbursement rates; however, other practices might see higher returns. Another potential limitation is regarding generalizability related to service volume and whether other hospitals and other institutions would be able to provide a similar type of volume. Over 1,200 encounters including initial and subsequent and procedures were billed under a single medical toxicologist during the first year toxicology consults were offered at our institution. Having had a Poison Control Center previously onsite certainly created awareness of and interest in toxicology as a distinct medical specialty, and when the Poison Center closed, a concerted effort was undertaken to present and describe the availability and types of services that the Medical Toxicology bedside consult service offered. In order to create this awareness, the medical toxicologist met directly with the various admitting services including internal medicine, critical care, pediatric, and psychiatry. The consult service also served as the replacement educational experience for toxicology in the medical student, resident, and fellow curriculum after the Poison Center closed. During the first year, it was up and running nearly 100 different rotators from emergency medicine, medicine, pediatrics, and other residencies as well as several fellows (pediatric EM, adolescent medicine, and critical care), and pharmacy and medical students spent time on the consult service. The emergency medicine interns and PG3s each spent 2 weeks on the service. This created a lot of visibility and awareness that the consult service was available. Types of consultations included not only accidental and purposeful self-poisonings but also withdrawal management, medication management, clearance consults, interpretation and guidance regarding drug testing, and counseling. The toxicology service also performed procedures including antidote administration (e.g., naloxone) as well as buprenorphine induction for opioid withdrawal and phenobarbital administration for alcohol withdrawal. Generalizability regarding billing and reimbursement to other services and institutions will depend upon not only patient volume but also the types of services offered, whether procedures are performed and the frequency of consultation and follow-up visit. Also, only certain types of encounters were included in this analysis. We excluded procedures, medication administration, counseling codes (tobacco, alcohol, and drug dependence counseling), clinic work (which was subsequently established after the first fiscal year was concluded), prolonged service, and telephone consultation codes from the main body of the analysis. While this data would have resulted in higher total charges and reimbursement, the specific impact on the ratio of charge to reimbursement rate is unclear. Thus, our actual overall charges and reimbursement amounts, based only on adding the non-included other encounters or procedures, were somewhat higher (approximately $10,000 higher) than what we actually reported. The effect on charge/reimbursement rates for these different codes on hourly charge/reimbursement rates is unknown.

Another area of potential limitation is the conservative use of critical care codes by our consultation service. Compared to other practices, the overall rate of critical care consultations was notably very low, accounting for less than 5 % of overall encounters. While the critical care encounter codes were very infrequently denied by our payers, they were potentially under-utilized as billing encounters. Many of the diagnosis used in the toxicology encounters support critical care (e.g., acidosis, respiratory failure, coma, encephalopathy, various types of poisoning, etc.). With more frequent application of the critical care codes, which were reimbursed at higher than most other initial consult codes, more revenue would be expected. Additionally, we have not taken into account the opportunity cost savings of reduced length of stay and fewer inpatient hospitalizations that may have been created by the actions and recommendations of the bedside medical toxicologist. Finally, this data represents the first fiscal year of the toxicology consultation service at our institution. Improvements and evolution in consultation and practice as well as in coding, billing, and in reimbursement would be anticipated.

Conclusions

Our data suggest that reimbursement rates for bedside toxicology practice are much higher than previously reported. Furthermore, revenue generated from professional charge reimbursement from bedside toxicology consultation can result in recouping a substantial portion of a medical toxicologist’s salary or the revenue could potentially fund fellowship positions and salaries or toxicology division infrastructure or simply allow buy down for greater portions of toxicology practice for those medical toxicologists interested in expanding the amount of toxicology time their professional activities encompass.

Acknowledgments

Portions of Dr. Wiegand’s time were made possible by salary support he received from the Department of Defense for research involving “Warning Signs for Suicide Attempters” (Award Number W81XWH-10-2-0178) and he has received an honorarium for work with buprenorphine patch (Butrans®) for research and manuscript preparation involving Research Abuse Diversion and Addiction Related Surveillance (RADARS®) projects from Purdue Pharmaceuticals.

Conflicts of interest

No other author, to the best of their knowledge, has any declarations of conflicts of interest based on ICJME guidelines

References

- 1.Mowry JB, Spyker DA, Cantilena LR, Jr, Bailey JE, et al. 2012 Annual report of the American Association Of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 30th annual report. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2013;51:949–1229. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2013.863906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simone KE. Thirty U.S. poison center reports later: greater demand, more difficult problems. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2014;52:91–92. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2013.878949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wax PM, Donovan JW. Fellowship training in medical toxicology: characteristics, perceptions, and career impact. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 2000;38:637–642. doi: 10.1081/CLT-100102013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bunn TL, Slavova S, Spiller HA, Colvin J, et al. The effect of poison control center consultation on accidental poisoning inpatient hospitalizations with preexisting medical conditions. J Toxic Environ Health A. 2008;71:283–288. doi: 10.1080/15287390701738459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee V, Kerr JF, Braitberg G, Louis WJ, et al. Impact of a toxicology service on a metropolitan teaching hospital. Emerg Med (Fremantle) 2001;13:37–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2026.2001.00175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedman LS, Krajewski A, Vannoy E, Allegretti A, et al. The association between U.S. poison center assistance and length of stay and hospital charges. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2014;52:198–206. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2014.892125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Offerman SR. The clinical management of acetaminophen poisoning in a community hospital system: factors associated with hospital length of stay. J Med Toxicol: Off J Am. Coll of Med Toxicol. 2011;7:4–11. doi: 10.1007/s13181-010-0115-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vassilev ZP, Marcus SM. The impact of a poison control center on the length of hospital stay for patients with poisoning. J Toxic Environ Health A. 2007;70:107–110. doi: 10.1080/15287390600755042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burda T, Leikin JB, Fischbein C, Woods K, et al. Emergency department use of flumazenil prior to poison center consultation. Vet Hum Toxicol. 1997;39:245–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leikin JB, Vogel S, Samo D, Stevens P, et al. Reimbursement profile of a private toxicology practice. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2006;44:261–265. doi: 10.1080/15563650600584402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clark RF, Williams SR, Nordt SP, Pearigen PD, et al. Resource-use analysis of a medical toxicology consultation service. Ann Emerg Med. 1998;31:705–709. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0644(98)70228-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Finkler SA. The distinction between cost and charges. Ann Intern Med. 1982;96:102–109. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-96-1-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fisher ES, Bynum JP, Skinner JS. Slowing the growth of health care costs—lessons from regional variation. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:849–852. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0809794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Watts SH, Promes SB, Hockberger R. The society for academic emergency medicine and association of academic chairs in emergency medicine 2009–2010 emergency medicine faculty salary and benefits survey. Acad Emerg Med. 2012;19:852–860. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2012.01400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]