Abstract

Objective

To determine the profile and determinants of successful aging in a developing country, characterized by low life-expectancy where successful agers may represent a unique group.

Design

The Ibadan Study of Aging is a community-based cohort study.

Setting

Eight contiguous states in the Yoruba-speaking region of Nigeria.

Participants

A multistage clustered sampling of households was used to select a representative sample of elderly persons (N=2149), aged 65 years and over at baseline. Nine hundred and thirty were successfully followed up for an average of 64 months between August 2003 and December 2009.

Measurements

Lifestyle and behavioural factors were assessed at baseline. Successful aging, defined using three indices (absence of chronic health conditions, functional independence, and satisfaction with life), was assessed at follow-up.

Results

Between 16% and 75% of respondents met at least one of the three indices of successful aging, while 7.5% met all three. Correlations between the three indices were small, ranging from 0.08 to 0.15. Also, different features predicted their outcomes, suggesting that they represent relatively independent trajectories of aging. While functional independence was predicted by baseline vigorous physical activity, life satisfaction was more likely among those who had rated their overall health as good. More males than females met all three indices. For this outcome, males were more likely never to have smoked (Adjusted Odds ratio, aOR, 4.7, 95% CI 1.55 – 14.46), and to report, at baseline, having contacts with friends (aOR 4.2, 95% CI 1.0 – 18.76) and participating in community activities (OR 16.0, 95% CI 1.23 – 204.40). Among females, there was a non-linear trend for younger age at baseline to predict this outcome.

Conclusions

Modifiable social and lifestyle factors predict successful aging in this population suggesting that health promotion targeting behavior change may lead to tangible benefits for health and wellbeing in old age.

Keywords: Successful aging, Community based cohort, Functional independence, Life satisfaction

INTRODUCTION

Worldwide, the growing population of the elderly and the challenges posed by this growth1 are, in part, giving rise to interest in the study of factors that may help to increase the quality and years of healthy aging2. The concept of successful aging, in which the elderly persons continue to enjoy good social, physical and psychological wellbeing3, derives from this interest. The growth of the elderly population is particularly striking in the developing world. Of the current population of persons aged 60 years and over in the world, about 64% reside in developing countries 4. The projection that these countries will account for 700 million of the expected 1 billion elderly persons in 2020 is a further indication of this dramatic growth5.

In spite of the demographic transition occurring in developing countries, much of what is currently known about successful aging has been derived from studies conducted in high income countries6-9. However, the profile and determinants of health outcomes in the elderly may be different in low- and middle-income countries, such as those in sub-Saharan Africa, from those in developed high-income countries. In Nigeria, for example, life expectancy is currently about 50 years for men and 52 years for women, which is at least two decades less than in Western Europe and North America10. In such a setting, it is plausible to suspect that persons who survive to the age of 65 or older constitute a uniquely resilient subgroup and may have features which differentiate them from older populations in high-income countries. In short, aging successfully in low- and middle-income countries may follow a peculiar trajectory from what has been described elsewhere. In this regard, we have earlier noted the paradox that, even though healthy life expectancy at birth in Nigeria, for example, is 50 years for men and 52 years for women, men and women who live until the age of 60 years can expect another 9 and 10 years of healthy life, respectively11.

There is no consensus on which model of successful aging is most valid to capture the complexity of the concept12. While several studies have used objective health outcomes such as absence of chronic health conditions or absence of functional role impairment13, there is also a growing acknowledgment that the subjective report of wellbeing by elderly persons is a valid index of aging outcome14, 15. In this report, we explore successful aging in a cohort of community-dwelling elderly persons from the perspectives of chronic health conditions, functional role independence, and self-report of wellbeing.

METHODS

Sample

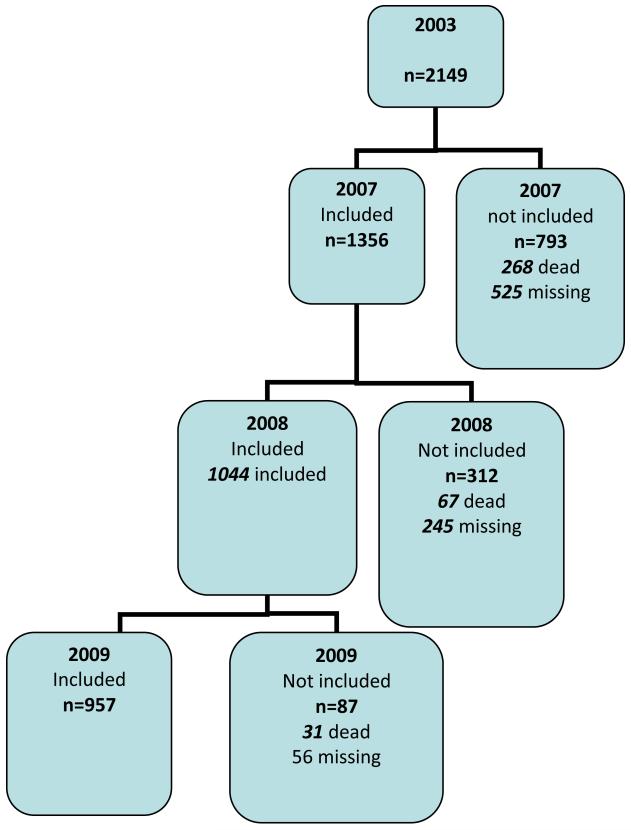

The Ibadan Study of Aging (ISA) is a longitudinal community study of the profile and determinants of healthy aging. A full description of the baseline methodology has been provided elsewhere11, 16, 17. Baseline assessments were conducted between August 2003 and November 2004 on 2149 subjects, aged 65 years and over, selected through a process of clustered multi-stage random sampling of households in the Yoruba-speaking south-west and north-central parts of Nigeria. This cohort was followed up annually between 2007 and 2009. Of the 2149 with complete assessment at baseline, 957 were successfully followed-up in 2009, approximately five years later. Figure 1 shows the yield at each wave of the study. The present report is based on 930 respondents on whom full data was obtained at follow-up.

Figure 1. Flow chart of the Ibadan Study of Aging.

Assessments of models of successful ageing at follow-up (2009)

Chronic health conditions

Physical conditions

Three blood pressure measurements were taken, in the right arm, at five minute intervals, with the subjects seated. Hypertension, based on the average of the three readings, is defined as systolic equal to or greater than 140mmHg or diastolic equal or greater than 90mmHg. We assessed, by self-report, whether respondents had arthritis, diabetes, heart disease and asthma in the previous 12 months using a symptom-based checklist, method of proven reliability and validity18, 19.

Neuropsychiatric conditions were assessed as previously described11, 17, 20

Depression was assessed with the World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) version three (CIDI.3), a fully structured diagnostic interview21. Dementia was assessed using previously validated tools, the 10- Word Delayed Recall Test and the Clinician Home-based Interview to assess Function (CHIF), followed by a review of all available information, including those of functional status obtained during interviews with subjects and relatives by a psychiatrist. Both major depression and dementia were diagnosed according to the criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition22.

Functional limitation

As described elsewhere, all respondents were assessed for functional limitations in six activities of daily living and seven instrumental activities of daily living16, 23, 24. Each of the activities in the two domains was rated: (1) can do without difficulty; (2) can do with some difficulty; (3) can do only with assistance; (4) unable to do activity. In defining successful aging using this model, for full functional independence, a respondent had to be rated either (1) or (2) on each of the activities. The rating of functional limitation achieved good to excellent test-retest reliability, with a κ range of 0.65–1.0 on all the items.

Life Satisfaction

We examined respondents’ own evaluation of their lives, using reported life satisfaction as the index. We used the Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS), a 5-item questionnaire that assesses overall satisfaction with life, rather than with specific domains of life25, 26. (e.g. “In most ways my life is close to my ideal”; “The conditions of my life are excellent”).

Responses are on a 7 item Likert scales, ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree, and with mid-point of neither agree or disagree. For the purpose of the exploration of successful aging, herein reported, all three agree statements are collapsed into one response category, “agree”, while all other responses are classified as “disagree”. In this cohort, SWLS showed a good internal reliability (Cronbach’s alpha 0.81) and high stability from one annual wave to another (r = 0.25; p< 0.001)

Assessment of predictors at baseline (2003/2004)

Physical activity

Respondent’s physical activity was assessed with the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ), a widely used tool with demonstrated cross-cultural validity27. The questionnaire measures physical activity across all domains of leisure-time, work, transportation, and household tasks. We used the summary indicator to categorize the respondents into three levels of physical activity: “low” [physically inactive], “moderate” and “vigorous” levels of physical activity. These categories were based on standard scoring criteria (http://www.ipaq.ki.se).

Social engagement

Two items 1) participation in household activities; and 2) participation in community activities were assessed, adapted from the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule, version 2 (WHO-DAS II)28. The relevant items asked “During the last 30 days, how much did you join in family activities, such as: eating together, talking with family members, visiting family members, working together?” and “During the last 30 days, how much did you join in community activities, such as: festivities, religious activities, talking with community members, working together?” Answers are rated as 1) Not at all, 2) A little bit, 3) Quite a bit, and 4) A lot. For this report, responses to each of the items are dichotomized as “Not at all” versus all others.

Social network was assessed with items from the Composite International Diagnostic Interview29. The relevant items enquire about the frequency of respondent’s contact with family members who do not live with the respondent and frequency of contact with friends. In this report, we have dichotomized the responses to no contacts at all versus contacts varying from less than once per month to daily.

Self-report of overall health was made using a 5-point scale: excellent, good, fair or poor. We dichotomize the ratings as excellent/very good/good versus fair/ poor.

Lifestyle

Respondents were asked about use of alcohol and tobacco. For each of the substances, responses were dichotomized as ever use versus never use.

Economic status was assessed by taking an inventory of household and personal items30. Respondents’ economic status is categorized by relating each respondent’s total possessions to the median number of possessions of the entire sample. Thus, economic status is rated low if its ratio to the median is 0.5 or less, low-average if the ratio is 0.5 – 1.0, high-average if it is 1.0 – 2.0, and high if it is over 2.0.

Residence was classified as rural (less than 12,000 households), semi-urban (12,000 – 20,000 households) and urban (greater than 20,000 households).

The Yoruba versions of all the instruments used in the present survey were derived using standard protocols of iterative back translation conducted by panels of bilingual experts. The ISA was approved by the University of Ibadan/University College Hospital, Ibadan Joint Ethical Review Board

Analysis

To account for the stratified multistage sampling procedure and the associated clustering, weights were derived and applied to all the rates reported.

Successful aging is defined in three independent ways: 1) absence of chronic health condition; 2) complete functional independence; and 3) self-reported satisfaction with life. Absence of chronic health conditions was defined as having none of the assessed physical or neuropsychiatric disorders. For full functional independence, respondents were required to have complete independence in the performance of both ADL and IADL. Persons who met our definition of successful aging using the dimension of life satisfaction were those who were rated “agreed” on each of the five items of the SWLS.

We examined the proportions meeting each definition of successful aging as well as those meeting all three definitions. The relationships between the three definitions were examined using tetracholic correlations.

A series of bivariate and multivariable logistic regression analyses were conducted to explore the predictors of successful aging, using each of the three definitions, separately for males and females. Similar analysis was conducted for persons meeting all three definitions. The results are presented in the form of odds ratios, with 95% confidence intervals. All analyses were conducted using the STATA statistical package31.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the cohort at baseline. At follow-up, the mean age of the sample was 79.0 years (s.e. 0.26). Females were significantly older than males: 79.7 (s.e. 0.37) versus 78.1 (s.e. 0.36); p < 0.01). We observed that persons in the oldest age group and those in the lowest economic groups were less likely to be followed up. No other features significantly differentiated those who were successfully followed-up from those who were not.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Sample at Baseline

| N = 930 | % |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Male | 61.1 |

| Female | 38.9 |

|

| |

| Age | |

| 80+ | 12.4 |

| 75-79 | 18.4 |

| 70-74 | 32.8 |

| 65-69 | 36.4 |

|

| |

| Education, years | |

| 13+ | 7.7 |

| 7-12 | 13.6 |

| 1-6 | 26.2 |

| 0 | 52.5 |

|

| |

| Residence | |

| Urban | 23.9 |

| Semi-urban | 42.2 |

| Rural | 33.9 |

|

| |

| Economic status | |

| Low | 19.2 |

| Low-average | 34.7 |

| High-average | 30.1 |

| Highest | 16.0 |

|

| |

| Ever smoked | |

| Yes | 44.6 |

| No | 55.4 |

|

| |

| Ever drank | |

| Yes | 22,6 |

| No | 77.4 |

|

| |

| Physical activity | |

| Low | 27.5 |

| Moderate | 50.6 |

| Vigorous | 21.9 |

|

| |

| Self-reported health | |

| Fair/Poor | 5.2 |

| Good/Excellent | 94.8 |

|

| |

| Contact with family | |

| No | 0.3 |

| Yes | 99.7 |

|

| |

| Contact with friends | |

| No | 7.6 |

| Yes | 92.4 |

|

| |

| Participation in household activities | |

| No | 8.6 |

| Yes | 91.4 |

|

| |

| Participation in community activities | |

| No | 7.7 |

| Yes | 92.3 |

Proportions of successful agers

Between 16% and 75% of respondents met at least one of the three indices of successful aging (Table 2). Fifty-five persons (7.5%) met all three definitions, of successful aging (31% of them females and 69% males). Males had a higher proportion of successful agers than females overall and on each index; however this was only significant for functional independence.

Table2.

Weighted Proportions (s.e.weighted) meeting each model of successful ageing

| Males (n=454) | Females (n=476) | Total (n=930) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No chronic health condition | 19.1 (2.13) | 12.5 (2.30) | 16.5 (1.61) |

| Functional independence* | 80.4 (2.46) | 64.5 (2.65) | 74.2 (1.58) |

| Life satisfaction | 42.9 (3.34) | 40.1 (3.17) | 41.8 (2.0) |

| Success Agers | 8.4 (1.08) | 6.0 (1.71) | 7.5 (0.93) |

p<0.01, comparing males with females.

The correlations between the three indices of successful aging were very modest, even though statistically significant. The correlation between absence of chronic health condition and functional independence was the highest but even here it was a mere 0.15 (p< 0.001), while that for life satisfaction and absence of chronic health condition was 0.08 (p< 0.05). (Not shown on table)

Baseline predictors of successful ageing: absence of chronic health condition (Table 3)

Table 3.

Predictors of the different indices of successful aging

| Absence of Chronic Health Conditions | Functional Independence | Self-Reported Satisfaction with Life | |

|---|---|---|---|

| OR(95% CI) p-value | OR(95% CI) p-value | OR(95% CI) p-value | |

| Age | |||

| 80+ | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 75-79 | 2.2(0.89-5.50) 0.084 | 0.7(0.41-1.05) 0.074 | 0.8(0.44-1.51) 0.514 |

| 70-74 | 1.6(0.71-3.71) 0.236 | 1.8(1.04-3.13) 0.038+ | 0.9(0.57-1.46) 0.694 |

| 65-69 | 2.3(1.09-4.97) 0.030* | 3.0(1.89-4.92) 0.000+ | 1.0(0.63-1.74) 0.846 |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Male | 1.7(0.09-2.76) 0.055* | 2.0(1.29-3.04) 0.003+ | 1.1(0.71-1.73) 0.636 |

| Education (years) | |||

| 13+ | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 7-12 | 1.5(0.43-5.17) 0.508 | 2.9(1.20-6.94) 0.020+ | 1.4(0.65-3.16) 0.361 |

| 1-6 | 1.7(0.60-4.79) 0.312 | 2.8(1.27-6.10) 0.013+ | 1.7(0.93-3.16) 0.081 |

| 0 | 1.3(0.42-4.11) 0.619 | 3.2(1.61-6.28) 0.002+ | 1.5(0.86-2.72) 0.141 |

| Residence | |||

| Urban | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Semi-urban | 1.1(0.63-1.93) 0.699 | 1.2(0.73-1.95) 0.468 | 1.2(0.81-1.67) 0.407 |

| Rural | 1.2(0.65-2.30) 0.515 | 1.5(1.03-2.24) 0.035+ | 0.8(0.53-1.18) 0.245 |

| Economic status | |||

| Highest | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| High-average | 1.1(0.57-2.10) 0.792 | 0.9(0.42-2.13) 0.889 | 0.4(0.24-0.57) 0.000* |

| Low-average | 0.9(0.42-1.96) 0.804 | 1.3(0.54-3.01) 0.573 | 0.5(0.30-0.71) 0.001* |

| Low | 0.8(0.51-1.40) 0.504 | 1.3(0.56-3.17) 0.499 | 0.4(0.21-0.68) 0.002* |

| Ever smoked | |||

| Yes | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| No | 1.2(0.65-2.27) 0.525 | 0.9(0.56-1.32) 0.487 | 1.2(0.93-1.67) 0.129 |

| Ever drank | |||

| Yes | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| No | 0.8(0.52-1.28) 0.364 | 0.8(0.53-1.22) 0.291 | 1.1(0.86-1.44) 0.411 |

| Physical activity | |||

| Low | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Moderate | 1.0(0.49-2.04) 0.995 | 1.7(1.08-2.80) 0.024+ | 0.7(0.49-1.15) 0.178 |

| Vigorous | 1.2(0.57-3.32) 0.686 | 5.4(2.42-11.9) 0.000+ | 0.8(0.41-1.37) 0.337 |

| Self-reported health | |||

| Fair/Poor | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Good/Excellent | 1.9(0.33-11.18) 0.450 | 1.8(0.86-3.84) 0.113 | 3.0(1.20-7.15) 0.017* |

| Contact with family | |||

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | - | 4.2(0.85-20.5) 0.076 | - |

| Contact with friends | |||

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 1.6(0.61-4.41) 0.309 | 1.4(0.73-2.65) 0.298 | 1.7(0.98-3.06) 0.059 |

| Participation in household activities | |||

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 0.9(0.43-1.79) 0.725 | 1.1(0.56-2.18) 0.771 | 1.0(0.55-1.93) 0.924 |

| Participation in community activities | |||

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 0.8(0.32-1.87) 0.562 | 0.9(0.53-1.52) 0.689 | 1.6(0.76-3.36) 0.208 |

p < 0.05; all comparisons controlled for functional disability at baseline

p <0.05; all comparisons controlled for age, sex and functional disability at baseline

In this model of successful aging, there was no difference by gender but individuals in the younger age groups (65-69 years) were more likely to have aged successfully.

Baseline predictors of successful aging: functional independence (Table 3)

In bivariate analyses that adjusted for baseline functional status, decreasing age at baseline and male gender predicted functional independence at follow-up. Also, low levels of formal education, and rural residence predicted successful ageing in this model. A significant linear relationship was observed between levels of reported physical activity at baseline and the likelihood of full functional independence at follow-up. When examined separately for each sex, the relationship was particularly striking among females in whom, compared to persons in the low activity group, those in the vigorous activity group had almost a 10-fold likelihood to be aging successfully (not shown in the table). Contacts with family showed a strong but non-significant trend to predict successful aging..

We next conducted multiple regression analyses, adjusting for the effects of all the variables that were significantly associated with functional independence on bivariate analysis (results not shown but available on request). In males, the analysis adjusted for age, years of education, lifetime use of alcohol and physical activity. Significant predictors of successful aging using this model were absence of formal education (OR 5.03, 95% CI: 1.07 – 23.76); 1 – 6 years of education (OR 4.28, 95% CI: 2.18 – 31.18); moderate physical activity (OR 3.60, 95% CI: 1.70 – 7.66) and vigorous physical activity (OR 8.11, 95% CI: 2.31 – 28.43). In females, the analysis adjusted for age and level of physical activity. The only feature that continued to predict functional independence at follow-up was vigorous physical activity at baseline (OR 9.00, 95% CI: 2.33 – 34.79).

Baseline predictors of successful aging: self-rated life satisfaction (Table 3)

Compared to persons in the highest economic category, those in the other categories had a reduced likelihood to rate themselves as being satisfied with their lives. Successful aging, using this definition, was 3 times more likely among those who had reported their overall health as excellent or good and 2 times more likely among those who had reported having frequent contacts with friends at baseline

Baseline predictors of successful aging

Fifty-five persons (7.5%) met all the three definitions of successful aging used in this paper, 31% females and 69% males. Table 4 shows the predictors of this outcome in the entire group. In view of the large difference in the proportions of females and males with this outcome, we further explored this outcome in each of the sexes. In multivariate analysis in which all significant features on bivariate analysis were adjusted for, predictors of this outcome in males were never having smoked (OR 4.7, 95% CI 1.55 – 14.46), having contacts with friends (OR 4.2, 95% CI 1.0 – 18.76) and community participation (OR 16.0, 95% CI 1.23 – 204.40). Among females, predictors were being aged 76-79 years (OR 10.9, 95% CI 1.47 – 81.09) or 65 – 69 years (OR 8.9, 95% CI 1.36 –57.62) at baseline.

Table 4.

Predictors of Successful Aging

| Age | OR(95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| 80+ | 1 | |

| 75-79 | 2.9(0.83-10.16) | 0.093 |

| 70-74 | 2.1(0.61-9.67) | 0.231 |

| 65-69 | 4.4(1.65-11.89) | 0.004* |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 1 | |

| Male | 1.4(0.71-2.88) | 0.311 |

| Education (years) | ||

| 13+ | 1 | |

| 7-12 | 1.2(0.20-7.68) | 0.818 |

| 1-6 | 1.1(0.19-5.92) | 0.951 |

| 0 | 1.2(0.22-6.11) | 0.846 |

| Residence | ||

| Urban | 1 | |

| Semi-urban | 1.4(0.67-2.70) | 0.382 |

| Rural | 0.8(0.36-1.72) | 0.527 |

| Economic status | ||

| Highest | 1 | |

| High-average | 0.6(0.29-1.37) | 0.238 |

| Low-average | 0.4(0.21-0.92) | 0.030* |

| Low | 0.4(0.21-0.75) | 0.006* |

| Ever smoked | ||

| Yes | 1 | |

| No | 1.6(0.71-3.46) | 0.254 |

| Ever drank | ||

| Yes | 1 | |

| No | 1.0(0.51-2.10) | 0.924 |

| Physical activity | ||

| Low | 1 | |

| Moderate | 1.0(0.35-2.61) | 0.935 |

| Vigorous | 1.0(0.40-3.21) | 0.802 |

| Self-reported health | ||

| Fair/Poor | 1 | |

| Good/Excellent | 1.1(0.10-11.30) | 0.946 |

| Contact with family | ||

| No | 1 | |

| Yes | - | |

| Contact with friends | ||

| No | 1 | |

| Yes | 15.7(3.69-66.51) | 0.001* |

| Participation in household activities | ||

| No | 1 | |

| Yes | 0.8(0.23-2.88) | 0.741 |

| Participation in community activities | ||

| No | 1 | |

| Yes | 45.3(5.89-348.89) | 0.001* |

p < 0.05; all comparisons controlled for functional disability at baseline

DISCUSSION

We explore, for the first time to our knowledge, the profile and predictors of successful aging, defined using multiple dimensions, in a population of elderly persons residing in a sub-Saharan African community. Our cohort, composed of persons aged 65 years and over at baseline, is unique not only because of a paucity of studies focussed on its health but because it is derived from a population where life expectancy is just about 50 years. The factors that determine successful aging in this population may therefore be of particular relevance to our understanding of social and environmental factors that select people out for healthy aging outcomes even in circumstances that may presumably be hostile to longevity.

Before considering the findings reported in this paper further, several caveats are in order. First, we have examined predictors of successful aging in persons who were aged 65 years and over at baseline. While it is possible that lifestyle factors that we examined may reflect lifelong ways of doing things among these elderly persons, it is also likely that distal factors operating earlier in life, and not examined in this study, may be important in determining aging outcomes. Second, we have studied predictors among elderly persons who remained alive through the follow-up period and have not included decedents. Thus, our findings relate to healthy aging among those who were living and did not include factors that may have been associated with this outcome among those who had died. Third, in view of the fact that most of the outcome and antecedent factors were based on self-report rather than objective investigations, the likelihood of reporting bias cannot be excluded. However, this is obviated by the fact that the information on the antecedent or predictor factors were obtained several years before that on outcomes.

Unlike most previous studies, we used three domains or models of successful aging, rather than a composite definition, following the observation that domains are more often agreed on than any particular combination. In doing this, we sought to address the dilemma often confronted by researchers in this area: are objective measures necessarily more valid than subjective reports of elderly persons?15, 32, 33 Our observation that the relationship between the three models is modest supports the approach we took. Thus, a striking observation is that the definition of successful aging used was critical in determining the proportion of elderly of persons who could be described as successful agers. Thus, while functional independence produced the highest proportions of successful agers (74%), absence of chronic health condition produced the least (17%). Subjective perception of aging, as assessed by self-reported life satisfaction, classified about 42% as aging successfully. Only 7.5% of the cohort met all the three definitions. In a review of 28 studies, Depp and Jeste observed that the reported proportion of successful agers ranged from 0.4% - 95% with one of the most important sources of variability being the definitions used6. For example, in a study by von Faber et al where successful aging was defined as having optimal overall functioning (measured in three domains: physical, social and psychocognitive functioning) and subjective well-being, only 10% of their sample could be classified as successfully aged9.

The findings of the exploration of predictors of successful aging lend themselves to several interesting interpretations. First, the three models of successful aging examined in this paper represent the outcomes of different life trajectories. Thus, even though there were similarities in the predictive factors, there were also important differences. For example, while we could not identify predictors for absence of chronic health condition, several factors were associated with functional independence. Perhaps, more distal factors, rather than the proximal ones we examined, were predictive of absence of chronic health conditions. Second, broadly similar factors were important for both males and females, albeit to different degrees. These factors included availability of supportive social network, self-reported overall health and physical activity. However, additional factors in males included abstinence from alcohol, never smoking, rural residence and economic status. Third, predictors of successful aging were essentially modifiable factors. Among the most salient were social and lifestyle factors such as availability of social network, not smoking and engagement in physical activity. These factors have been noted in some previous studies 6, 12, 34-36.

The findings of this study show that, depending on the model used, between 7.5% and 75% of community-dwelling elderly persons in this developing country, with low life expectancy, could be classified as successful agers. Successful aging is predicted by modifiable factors such as physical exercise and availability of supportive social network. The findings emphasize the potential value of health promotion in older people that targets behaviour and that may lead to demonstrable benefits in health and overall wellbeing.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Sponsor’s Role: The sponsors played no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review or approval of the manuscript.

The Ibadan Study of Aging was funded by the Wellcome Trust.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: We declare that there are no potential conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Oye Gureje, Department of Psychiatry, College of Medicine, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria.

Bibilola D. Oladeji, Department of Psychiatry, College of Medicine, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria

Taiwo Abiona, Department of Community Medicine, College of Medicine, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria.

Somnath Chatterji, Department of Health Statistics and Informatics, World Health Organization (WHO), Switzerland, Geneva.

REFERENCES

- 1.Christensen K, Doblhammer G, Rau R, Vaupel JW. Ageing populations: the challenges ahead. Lancet. 2009;374:1196–1208. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61460-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guralnik J, Kaplan GK. Predictors of healthy aging: prospective evidence from the Alameda Country Study. American Journal of Public Health. 1989;79:703–708. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.6.703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rowe JW, Kahn RL. Human aging: usual and successful. Science. 1987;237:143–149. doi: 10.1126/science.3299702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Velkoff VA, Kowal PR. In: Population Aging in Sub-Saharan Africa:Demographic Dimensions 2006. U.S. Census Bureau, editor. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 2007. Vol Current Population Reports, P95/07-1. [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization Health futures. 1999 http://www.who.int/hpr/expo. Accessed.

- 6.Depp CA, Jeste DV. Definitions and predictors of successful aging: a comprehensive review of larger quantitative studies. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14:6–20. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000192501.03069.bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castro-Lionard K, Thomas-Anterion C, Crawford-Achour E, Rouch I, Trombert-Paviot B, Barthelemy JC, Laurent B, Roche F, Gonthier R. Can maintaining cognitive function at 65 years old predict successful ageing 6 years later? the PROOF study. Age Ageing. 2011;40(2):259–265. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afq174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Knight T, Ricciardelli LA. Successful aging: perceptions of adults aged between 70 and 101 years. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 2003;56:223–245. doi: 10.2190/CG1A-4Y73-WEW8-44QY. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.von Faber M, Bootsma–van der Wiel A, van Exel E, Gusekloo J, Lagaay AM, van Dongen E, KD L, van der Geest S, Westerndorp RGJ. Successful aging in the oldest old: Who can be characterized as successfully aged? Archives of Internal Medicine. 2001;161(22):2694–2700. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.22.2694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. [Accessed Accessed Dec 15th 2008];Country Statistics. 2008 www.unicef.org/infobycountry/niger_statistics Updated Last Updated Date.

- 11.Gureje O, Kola L, Afolabi E. Epidemiology of major depressive disorder in the Ibadan Study of Ageing. Lancet. 2007;370:957–964. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61446-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strawbridge WJ, Cohen RD, Shema SJ, Kaplan GA. Successful aging: predictors and associated activities. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;144:135–141. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Depp CA, Jeste DV. Definitions and predictors of successful aging: a comprehensive review of larger quantitative studies. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14:6–20. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000192501.03069.bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Montross LP, Depp C, Daly J, Reichstadt J, Golshan S, Moore D, Sitzer D, Jeste DV. Correlates of self-rated successful aging among community-dwelling older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14:43–51. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000192489.43179.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strawbridge WJ, Wallhagen MI, Cohen RD. Successful aging and well-being: self-rated compared with Rowe and Kahn. Gerontologist. 2002;42:727–733. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.6.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gureje O, Ogunniyi A, Kola L, Afolabi E. Functional disability among elderly Nigerians: results from the Ibadan Study of Ageing. The Journal of the American Geriatric Society. 2006;54(11):1874–1789. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00944.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gureje O, Oladeji B, Abiona T. Incidence and risk factors for late-life depression in the Ibadan Study of Ageing. Psychological Medicine. 2011:1–10. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710002643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edwards WS, Winn DM, Kurlantzick V, et al. Vital and Health Statistics: Evaluation of National Health Interview Survey Diagnostic Reporting. Maryland, USA: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vilagut G, Saunders K, Alonso J. Survey methods for studying mental-physical omorbidity. In: Von Korff M, SK M, Gureje O, editors. Global perspectives on mental and physical comorbidities in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. Cambridge University Press; United Kingdom: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gureje O, Ogunniyi A, Kola L, Abiona T. Incidence of and risk factors for dementia in the Ibadan Study of Ageing. Journal of American Geriatric Society. 2011;59(5):869–874. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03374.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kessler RC, Ustun TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13(2):93–121. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Psychiatric Association . DSM-IV: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW. Studies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. Journal of American Medical Association. 1963;185:914–919. doi: 10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nagi SZ. An epidemiology of disability among adults in the United States. Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly, Health and Society. 1976;54:439–467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment49. 1985;49:71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Diener E, Suh E, Oishi S. Recent findings on subjective well-being. Indian Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1997;24:25–41. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Craig CL, et al. The International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ): A comprehensive reliability and validity study in twelve countries. Med Sci Sports ExercCraig. 2003;35:1381–1395. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.World Health Organization . WHO-Disability Assessment Schedule II. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kessler RC, Ustun TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13:93–121. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ferguson BD, Tandon A, Gakidou E, Murray CJL. Estimating permanent income using indicator variables. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 31.StataCorp . Stata Statistical Software, version 7,.0 for windows. Stata, College Station; Texas: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Montross LP, Depp C, Daly J, Reichstadt J, Golshan S, Moore D, Sitzer D, Jeste DV. Correlates of self-rated successful aging among community-dwelling older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14:43–51. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000192489.43179.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Phelan EA, Anderson LA, LaCroix AZ, Larson EB. Older adults’ views of “successful aging”--how do they compare with researchers’ definitions? Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2004;53(2):211–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peel NM, McClure RJ, Bartlett HP. Behavioral determinants of healthy aging. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2005;28(3):298–304. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Achour EC, Barthelemy JC, Lionard KC, Trombert B, Lacour JR, Thomas-Anterion C, Gonthier R, Garet M, Roch F. Level of physical activity at the age of 65 predicts successful aging seven years later: the PROOF study. Rejuvenation Res. 2011;14(2):215–221. doi: 10.1089/rej.2010.1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parslow RA, Lewis VJ, Nay R. Successful aging: development and testing of a multidimensional model using data from a large sample of older Australians. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2011;59:2077–2083. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03665.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]