Abstract

Background

Patients undergoing treatment for malignant gliomas (MGs) can encounter medical costs beyond what their insurance covers. The magnitude and type of costs experienced by patients are unknown. The purpose of this study was to have patients or their families report on the medical costs incurred during the patients MG treatment.

Methods

Patients with MG were eligible if they were within 6 months of diagnosis or tumor recurrence. Patients had to be ≥18 years of age, fluent in English, and not aphasic. Weekly logbooks were issued to patients for recording associated costs for ∼6 months or until tumor progression. “Out-of-pocket” (OOP) costs included medical and nonmedical expenses that were not reimbursed by insurance. Direct medical costs included hospital and physician bills. Direct nonmedical costs included transportation, parking, and other related items. Indirect medical costs included lost wages. Costs were analyzed to provide mean and medians with range of expenses.

Results

Forty-three patients provided cost data for a median of 12 weeks. There were 25 men and 18 women with a median age of 57 years (range, 24y–73y); 79% were married, and 49% reported annual income >$75 000. Health insurance coverage was preferred provider organizations for 58% of patients, and median deductible was $1 500. Median monthly OOP cost was $1 342 (mean, $2 451; range, $333.41–$17 267.16). The highest OOP median costs were medication copayments ($710; range, $0–13 611.20), transportation ($327; range, $0–$1 927), and hospital bill copayments ($403; range, $0–$4 000). Median lost wages were $7 500, and median lost days of work were 12.8.

Conclusions

OOP costs for MG patients can be significant and comprise direct and indirect costs across several areas. Informing patients about expected costs could limit additional duress and allow financial support systems to be implemented.

Keywords: financial burden, glioma, medical costs

A national survey from researchers at the Harvard School of Public Health found that 25% of families of cancer patients used up all or most of their savings for cancer treatment.1 In this same study, 22% and 46% of insured and uninsured patients, respectively, depleted most, if not all, of their savings. Furthermore, 11% of uninsured patients were no longer able to afford basic necessities such as food, heat, or housing after paying for their cancer treatments. The Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) cancer registry followed 231 799 adults with newly diagnosed primary cancers from 1995–2009 for a mean of 4.3 years. During this follow up, at least 4 805 (2.1%) patients filed for bankruptcy within a median of 2.5 years from diagnosis.2 The high cost of cancer treatment in the United States in general results in financial hardship, even if the patient has coverage by a public or private health insurance carrier.1,3–5 The diagnosis of malignant glioma (MG), a disease with a high short-term mortality rate, results in a range of financial obligations related to medical care that are not generally covered by private health insurance programs, the Medicare and Medicaid programs, or the Veterans Administration. Because of the focus on treatment and palliation as well as the poor short-term prognosis, no prior study has evaluated the financial impact encountered by patients with malignant gliomas.

Historically, “high financial burden” has been described as out-of-pocket (OOP) costs >20% of total income.4 By this definition, high burden was seen in 13.4% of cancer patients compared with 9.7% of patients with other chronic conditions.4 One study looking at the financial burden of health care assessed OOP costs by defining 2classes: total financial burden and health care services burden. For the group diagnosed with cancer, 11.4% had a health care financial burden exceeding 20% of the family income.6 Three studies done in the United States have calculated OOP medical costs for persons with breast and prostate cancer; however there is no data on OOP medical costs associated with MG.1,7,8 The impact of these costs can affect more than just the patient's or caregiver's quality of life; it could potentially affect treatment planning from both the patient and physician perspective. OOP spending often influences treatment decisions for patients as well as patient compliance.9

A few studies have measured direct and indirect costs for cancer patients. Extensive copayments and/or deductibles, travel costs, loss of income, and home care can cause remarkably high OOP expenditures.10 According to reports from the American Cancer Society, 66% of total costs associated with general cancer treatment are nonmedical and are not covered by basic insurance policies.11 These costs can increase the emotional stress beyond what patients and their families are already dealing with.

To our knowledge, no study has reported on the financial burden experienced by patients with MG and their families as well as the subsequent impact on patient and family quality of life. The purpose of this pilot study was to report on medical expenditures experienced by patients with MG.

Methods

The study protocol and procedures were developed and extensively validated in the Northwestern University Out Of Pocket Cancer Cost Project.12 Participants were recruited between August 07, 2008, and May 10, 2012, from the Neuro-Oncology Clinic at Northwestern University's Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center. Prior to study registration, all patients and caregivers signed IRB-approved consent documents. Participants had to have a grade III or IV malignant glioma within 6 months of diagnosis or relapse, to assure that most of them would be on active treatment during the time of this study. Participants had to be ≥18 years of age, have a Karnofsky Performance Score ≥60, a life expectancy of at least 4 months, be fluent in English, and not have an aphasia. Caregivers needed to be fluent in English. After consenting for the trial, participants met with the study coordinator and were given weekly logbooks to track OOP costs by the patient or caregiver. Data for logbooks were collected for a period of up to 6 months or disease progression. Both direct medical expenses and direct nonmedical expenses were measured. Demographic data collected at the initial visit included age, sex, and lost wages or time off from work. Participants and caregivers were financially compensated with a gift card for their cooperation with the study.

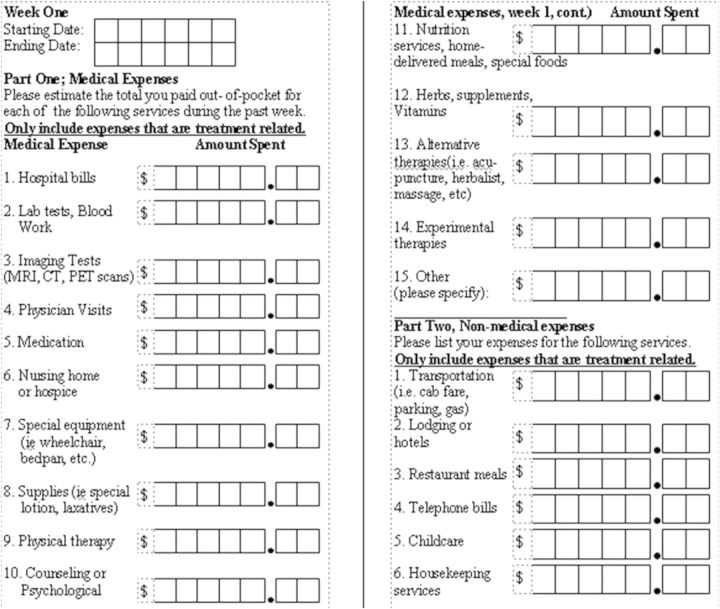

The logbooks were divided into weekly segments and subdivided into direct medical and nonmedical costs to keep each participant's information organized. Weekly spreadsheets, which were viewed as a single page, had a series of 21 cost categories for the participant or caregiver to enter their respective costs (Figure 1). These cost categories included items such as transportation, medical equipment, hospital bills, and medications (Figure 1). Data were collected from participants or family members every 4–8 weeks when they were seen in clinic (but prior to seeing the physician). Data were then entered onto a database but were not analyzed until the trial was completed. Our coordinator worked with participants and families to optimize data collection and answer any questions that arose.

Figure 1.

Cost categories included in logbooks.

After completion of logbooks, the primary outcome measures were median and mean OOP costs per participant based on the collected direct medical and nonmedical costs. For this study, OOP costs were organized into 3 categories: (i) direct medical costs (eg, hospital stays, physician visits, laboratory testing, and medications); (ii) direct nonmedical costs (eg, transportation, parking, cost of meals); and (iii) indirect costs (eg, lost wages or time from work).

Data Analysis

Means, standard deviations, medians, and sums as well as percentages of costs >0 were reported for individual expenses and total cost for the entire study population. Lastly, means, standard deviations, medians, and sums for individual and total costs were reported by income groups of <$75 000 or ≥$75 000 (this cut off was the median income in our patient cohort).

Results

Although 65 patients signed consent forms, only 43 (67% response rate) completed at least one entry in the logbook with demographics outlined in Table 1. (The other patients were generally not interested in completing the logbooks or were too ill to do so.) Of the 43 participants, 23 were male, and 33 (79%) were married with a median age of 57 years (range, 24y–73y). The most common tumor location was frontal lobe (37%). Education levels included high school (28%), technical (7%), associate degree (2%), bachelor degree (37%), graduate degree (21%), and 2 unknown. Insurance coverage was also recorded with 25 (58%) participants having a preferred provider organization (PPO), 10 (23%) having Medicare/Medicaid (23%), 3 (7%) having a health maintenance organization (HMO), 3 (7%) having a private carrier, and 2 (5%) who were uninsured (5%). The median deductible was $1 500 (range, $0–$6 000) for the 27 participants who answered this question. When asked about level of insurance coverage, 27 of 31 participants noted they had adequate coverage (5 of whom had only major medical coverage); 2 participants noted they did not have adequate coverage, and 2 did not reply.

Table 1.

Demographics

| Number | Percent of Total | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 43 | 100% |

| Male/female | 23/20 | 53%/47% |

| Married/single | 33/10 | 77%/23% |

| Median age (range) | 53y (24y–73y) | |

| Newly diagnosed/recurrent | 35/8 | 81/19% |

| Location of tumor | ||

| Frontal lobe | 16 | |

| Parietal lobe | 7 | |

| Temporal lobe | 7 | |

| Parietal-temporal lobe | 3 | |

| Occipital lobe | 3 | |

| More than 2 lobes | 5 | |

| Thalamus | 1 | |

| Temporal-occipital | 1 | |

| Income bracket | ||

| <$75 000 | 21 | 49% |

| >$75 000 | 22 | 51% |

Of the total 43 participants (Table 2), 13 (30%) were employed (30%), 12 (29%) were on a leave of absence, 11 (25%) were retired, and 7 (16%) were unemployed. Income level was ≥$75 000 for 22 (51%) participants and <$75 000 for 21 (49%) participants. Of the 22 participants with an income <$75 000, 3 (14%) had a recurrent MG, and 5 (23%) with an income ≥$75 000 had a recurrent MG. The median income in our patients was 75 000, which we used as a salary cutoff. Employment status at the time of enrollment for the cohort ≥$75 000 was 9 (41%) participants employed, 3 (13.6%) unemployed, 6 (27.2%) on leave of absence, and 4 (18.1%) retired. In the cohort with an income status of < $75 000 at the time of enrollment, 4 (19%) were employed, 4 (19%) were unemployed, 6 (28.5%) were on leave of absence, and 7 (33.3%) were retired.

Table 2.

Demographics based on income

| Demographics | ≥$75 000 | <$75 000 | All Patients |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 22 (51%) | 21(49%) | 43 (100%) |

| Sex (male) | 11 (50%) | 14 (66%) | 25 (58%) |

| Median age (range) | 53.3y (34y–71y) | 52.4y (24y–73y) | 53 (24y–73y) |

| Marital status (married) | 19 (86%) | 15 (71%) | 34 (79%) |

| Employment status | |||

| Employed | 9 (41%) | 4 (19%) | 13 (30.2%) |

| Unemployed | 3 (13.6%) | 4 (19%) | 7 (16.2%) |

| Leave of absence | 6 (27.2%) | 6 (58.5%) | 12 (28%) |

| Retired | 4 (18.1%) | 7 (33.3%) | 11 (25.5%) |

Of the 43 participants who had analyzable data, 36 completed a logbook for one month, 33 completed logbooks for 2 and 3 months, 27 completed logbooks for 4 months, 26 completed logbooks for 5 months, 18 completed log books for 6 months, and 13 completed logbooks for >6 months.

The mean and median monthly total OOP costs for participants with malignant glioma was $2 450 and $1 341, respectively, and represented costs for the 21 cost categories encompassing both direct medical and nonmedical care (Tables 3). Monthly median costs comprised both direct medical costs ($1 509; range, $0–$17 224.12) and nonmedical direct costs ($999; range, $0–$5 094) including transportation, childcare, and cost of meals. The 3 greatest cost categories each month included medication copayments (median, $176; mean, $710; range, $0.00–$13 611.20), transportation (median, $160; mean, $327; range, $0–$1 927), and hospital bills (median, $109; mean, $403; range,$0–$4 000). These 3 highest cost categories comprised ∼50% of the monthly average cost irrespective of the median income. The lowest mean monthly costs were noted in experimental therapies (median, $0; mean, $0.25; range, $0–$10.93), hospice/nursing home (median, $0; mean, $5; range, $0–$156.80), and phone bills (median,$0; mean, $13; range, $0–$175), which imply no expenses in these realms. Participants were asked about lost wages and days of work lost for the period prior to enrollment. For those who responded, the median lost wages were $7,500 (range, $0.00–$13 875), and median lost days of work were 12.8 (range, 0–33.3). We collected lost wage data on the participants while they were on the study. The ≥$75 000 group had a higher lost income (median, $11 000; mean, $14 677; range, $0–52 000) compared with the <$75 000 group (median, $3 500; mean, $4 024; range, $0–$9 000) over a 3-month period. Monthly charges varied for hospital bills, physician visits, supplies, transportation, visits, and total cost (all P <.0001), special equipment (P = .002), and supplements (P = .006). We assessed OOP costs longitudinally for the 21 categories, and special equipment was the only expense (P <.01) that increased over time. We assessed total costs expended for participants in the first 3 months of treatment to likely include radiation (mean, $679.64; range, $0–$9 980.00) compared with the second 3 months on study (mean, $285.12; range, $0–$8 300), which showed a significant difference in total expenditures (P = .00002).

Table 3.

Mean (with range) and median monthly direct medical and nonmedical costs per category

| Variable | n | Mean (range) | Median | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct cost | ||||

| Medication | 43 | $710.45 ($0–$13 611.20) | $176.61 | 2088.96 |

| Hospital bills | 43 | $402.56 ($0–$4 000.00) | $109.68 | 831.63 |

| Physician visits | 43 | $253.83 (0$–$4 000.00) | $56.25 | 654.09 |

| Supplies | 43 | $78.54 ($0–$560.00) | $15.89 | 118.3 |

| Supplements | 43 | $82.61 ($0–$1 413.33) | $7.08 | 223.74 |

| Other | 43 | $165.07 ($0–$28.00) | $0 | 469.41 |

| Alternative therapies | 43 | $62.84 ($0–$2 022.86) | $0 | 308.54 |

| Imaging | 43 | $87.05 ($0–$2 470.08) | $0 | 376.39 |

| Physical therapy | 43 | $53.51 ($0–$1 290.36) | $0 | 204.55 |

| Lab | 43 | $20.81 ($0–$450.05) | $0 | 71.35 |

| Special equipment | 43 | $15.12 ($0–$200.00) | $0 | 36.01 |

| Nutrition | 43 | $12.4 ($0–$192.00) | $0 | 36.51 |

| Hospice/Nursing Home | 43 | $4.83 ($0–$156.80) | $0 | 25.05 |

| Experimental therapies | 43 | $0.25 ($0–$10.93) | $0 | 1.67 |

| Indirect cost | ||||

| Transportation | 43 | $327.29 ($0–$1 920.00) | $160 | 438.48 |

| Meals | 43 | $131.7 ($0–$980.00) | $74.62 | 189.86 |

| Housekeeping | 43 | $64.76 ($0–$1 028.00) | $0 | 210.51 |

| Childcare | 43 | $41.33 ($0–$795.00) | $0 | 143.52 |

| Counseling | 43 | $31.63 ($0–$718.75) | $0 | 118.43 |

| Hotels | 43 | $20.34 ($0–$256.25) | $0 | 53.63 |

| Phone | 43 | $12.54 ($0–$175.00) | $0 | 36.26 |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation

We also asked about expenses for alternative medications or treatments at enrollment. The median expenses reported were $18 (range, $0–$3 000), with the highest expense being for acupuncture/massage ($3 300), and the most common expenditures being for vitamins, acupuncture/massage, and green tea (Table 4).

Table 4.

Alternative Medicines or healing approaches

| Alternative practice | Number of Patients | Total Cost |

|---|---|---|

| Vitamins | 23 | $3 019.00 |

| Green tea | 8 | $6 9.50 |

| Acupuncture/massage | 7 | $3 300.00 |

| Faith/prayer | 4 | $0.00 |

| Alternative practitioner | 4 | $3 230.00 |

| Yoga | 3 | $50.00 |

| Support group | 2 | $0.00 |

Discussion

This study is one of the first to analyze OOP costs for participants with MGs. The median and mean overall monthly OOP costs were $1 341 and $2 451, respectively (range, $333.41–$17 267.16) per participant and were comparable irrespective of total income level. Expenses did decrease after the first 3 months of data collection, which suggested that expenses were lower post radiation because of less travel-related and medication costs; however, this reduction could also be due to participant attrition. The 21 categorical costs in our study documented that the greatest OOP expenses were for direct medical expenses. The 3 largest direct medical expenses were medication costs, hospital bills, and clinician copayments. Nonmedical direct costs were sizable, with the highest cost categories being transportation, cost of special equipment, childcare, and meals. The cost of special equipment was the only expense that increased significantly over time. The travel costs for the participants included in this study, and in other studies, were unexpectedly high. Travel expenses were likely due to the location of our tertiary care institution, the high gasoline costs to drive there, and the price for parking. Medication costs were high for all participants; however, those participants whose income was ≥$75 000 had higher medication costs than those who earned <$75 000 per year. This may have been due to the assistance programs for medications available to those in lower income brackets. Hospice/nursing home costs were essentially zero (based on the 3 participants who completed this question), but most of our participants were newly diagnosed and were not in need of nursing home care or candidates for hospice; in addition, most insurance plans have hospice benefits. Of note, data collection stopped once participants entered hospice. Costs may have also been low due to how the participants interpreted the questions about costs related that domain. The main difference seen between participants who made ≥$75 000.00 was employment status at the time of diagnosis; there were twice as many participants employed in the higher income level compared with those in the lower income level.

A limited number of studies have reported direct medical costs for MG therapy; however, these studies did not include OOP costs. Their results vary depending on the country of analysis. One retrospective study, done in the United States for the years 1998–2000, found that the mean total monthly cost for participants with a brain cancer diagnosis was $6 364.13 A Canadian study looked at the total overall cost for patients with glioblastoma multiforme from diagnosis to death between 1996–1998 and found the average overall cost to be Can$22 447 (US $22 036). In comparison, a European study published in 2004 showed the monthly of cost of recurrent glioma ranged from €2 450–€3 342 (US$3 236–US$4 414).14 None of these studies addressed nondirect medical costs such as transportation, child care, or special equipment.

Using similar categories as in our study, a prior evaluation done in the early 2000s found that mean monthly OOP expenses for lymphoma and breast cancer patients at our institution were $1 888 and $1 455, respectively.15 The higher costs for MG patients may be due to impaired neurological function, leading to the need for physical or occupational therapy and durable equipment as well the cost for accessing specialized neuro-oncologic care. Changing insurance coverage that places a higher demand on patients could also be an important factor, especially when oral chemotherapies are used. Cost differences may also be due to the treatment modalities and/or chemotherapies used in the different diseases. One study from Canada, done from 2001–2003, showed the average income loss for a household to be Can$4 978 (US$4 887) per cancer episode.16 Within the United States, no studies have looked at income loss for patients with cancer, and there are no data on lost income for MG patients. It would be expected that income loss for patients with MG would be higher than other cancers because of the impact of the disease and its treatments on their neurological and cognitive function that may prevent them from returning to work in any capacity. Data on days of work missed and income lost for each participant in our study were self-reported and collected with the initial survey; therefore, the true meaning is unclear. Nevertheless, it does provide some insight into the impact of MG on work. Collecting data over time, when the impact on work performance is likely greater, would be important for understanding the financial losses inherent to having a MG.

Despite the importance of the data, our study has several limitations. Firstly, this was a small study evaluating one geographic area in the United States, where most of our patients have insurance, and may not reflect the costs that patients experience throughout the country in metropolitan, suburban, or rural areas. Additionally, all OOP costs in this study were self-reported by the participants and their caregivers, which could have led to responder bias because they may have generalized the costs if the itemized records were not appropriately maintained. Also, the degree of data collection was variable and may not be completely accurate due to the time required by participants and families to complete logbooks while under the stress of coping with a MG and the effects of treatment on general well-being. Also, some participants may not have been able to clearly distinguish the categories used in the logbook. Some of our data were captured only at enrollment and not over time, which could have yielded other relevant data. In addition, some of the cost data are based on a small number of responders and did not capture copays separately from maximum OOU expenses and coinsurance. Finally, like most questionnaire-based trials, we had attrition in the number of logbooks completed, especially after month 5. The attrition of data over time affects our ability to accurately assess longitudinal expenses and limits the interpretability of our data on a monthly basis, with more generalizable data in the earlier time points than later, when less data are obtained. Nevertheless, approximately 75% of participants provided 3 months of data and 60% provided 4 and 5 months of data, which provides some information about expenses.

There is considerable cost accrued for each MG patient and their family following diagnosis. While our study has limitations, it does provide some insight into the types of expenses incurred by patients who are not covered by insurance. It is important that health care practitioners be aware of the financial burden on patients and their families and work with them to minimize costs by using evidence-based treatment approaches. They should also attempt to minimize medical costs in all areas (eg, generic medications). This can help limit financial stressors for patients during an already trying time and optimize health care expenses on a broader level. Larger scale analyses are needed to target OOP costs across multiple institutions and across larger demographic areas. The cost for insured versus uninsured patients should also be compared to understand the financial burden for all patients, as broader coverage for cancer patients may be needed. Ultimately, a larger analysis would also help with understanding the full impact of cost on quality of life for patients and their families. In the setting of changing domestic health care policy in the United States, the impact of cost on medical decision-making will likely become more relevant, and understanding these costs will allow better adaptation into a new health care paradigm and an evidence-based treatment plan that should improve cost effectiveness.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the American Brain Tumor Association.

D.I.J. is now at Yale School of Public Health, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven CT 06510; S.A.G. is now at Cadence Health-Central DuPage Hospital, Warrenville, IL 60555.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

References

- 1.USA Today/Kaiser Family Foundation/Harvard School of Public Health National Survey of Households Affected by Cancer. 2006. http://kff.org/health-costs/poll-finding/usa-todaykaiser-family-foundationharvard-school-of-public-2/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Macready N. The climbing costs of cancer care. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(19):1433–1435. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elkin EB, Bach PB. Cancer's next frontier: addressing high and increasing costs. JAMA. 2010;303(11):1086–1087. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernard DS, Farr SL, Fang Z. National estimates of out-of-pocket health care expenditure burdens among nonelderly adults with cancer: 2001 to 2008. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(20):2821–2826. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.0522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ward E, Halpern M, Schrag N, et al. Association of insurance with cancer care utilization and outcomes. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58(1):9–31. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Banthin JS, Bernard DM. Changes in financial burdens for health care: national estimates for the population younger than 65 years, 1996 to 2003. JAMA. 2006;296(22):2712–2719. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.22.2712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jayadevappa R, Schwartz JS, Chhatre S, et al. The burden of out-of-pocket and indirect costs of prostate cancer. Prostate. 2010;70(11):1255–1264. doi: 10.1002/pros.21161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brooks J, Wilson K, Amir Z. Additional financial costs borne by cancer patients: A narrative review. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2011;15(4):302–310. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neumann PJ, Palmer JA, Nadler E, et al. Cancer therapy costs influence treatment: a national survey of oncologists. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29(1):196–202. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guidry JJ, Aday LA, Zhang D, et al. Cost considerations as potential barriers to cancer treatment. Cancer Pract. 1998;6(3):182–187. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.1998.006003182.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tatro DA. The next sales boom: critical illness insurance protection. Broker World. 1998;6:80–88. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Calhoun EA, Bennett CL. Evaluating the total costs of cancer. The Northwestern University Costs of Cancer Program. Oncology (Williston Park) 2003;17(1):109–114. discussion 119–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang S, Long SR, Kutikova L, et al. Estimating the cost of cancer: results on the basis of claims data analyses for cancer patients diagnosed with seven types of cancer during 1999 to 2000. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(17):3524–3530. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.10.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wasserfallen JB, Ostermann S, Leyvraz S, et al. Cost of temozolomide therapy and global care for recurrent malignant gliomas followed until death. Neuro Oncol. 2005;7(2):189–195. doi: 10.1215/S1152851704000687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oatis W, Nonzee N, Markossian T, et al. Interpreting out-of-pocket expenditures for cancer patients: The importance of considering baseline household income information. J Clin Oncol. 2009 ASCO Annual Meeting Proceedings (Post-Meeting Edition). Vol 27, No 15S (May 20 Supplement), 2009: 6541. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Longo CJ, Deber R, Fitch M, et al. An examination of cancer patients' monthly ‘out-of-pocket’ costs in Ontario, Canada. Eur J Cancer Care. 2007;16(6):500–507. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2007.00783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]