Abstract

Patient-reported outcomes (PRO) are questionnaire measures of patients’ symptoms, functioning, and health-related quality of life. They are designed to provide important clinical information that generally cannot be captured with objective medical testing. In 2004, the National Institutes of Health launched a research initiative to improve the clinical research enterprise by developing state-of-the-art PROs. The NIH Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement System (PROMIS) and Assessment Center are the products of that initiative. Adult, pediatric, and parent-proxy item banks have been developed by using contemporary psychometric methods, yielding rapid, accurate measurements. PROMIS currently provides tools for assessing physical, mental, and social health using short-form and computer-adaptive testing methods. The PROMIS tools are being adopted for use in clinical trials and translational research. They are also being introduced in clinical medicine to assess a broad range of disease outcomes. Recent legislative developments in the United States support greater efforts to include patients’ reports of health experience in order to evaluate treatment outcomes, engage in shared decision-making, and prioritize the focus of treatment. PROs have garnered increased attention by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for evaluating drugs and medical devices. Recent calls for comparative effectiveness research favor inclusion of PROs. PROs could also potentially improve quality of care and disease outcomes, provide patient-centered assessment for comparative effectiveness research, and enable a common metric for tracking outcomes across providers and medical systems.

Keywords: informatics, comparative effectiveness, patient involvement

Introduction

Over a decade ago, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) recognized shortcomings in the quality of the Patient-Reported Outcomes (PRO) available for outcome measures in clinical trials.1 Existing “legacy” measures had undergone development without the advantages of contemporary psychometric advances. As a result, NIH included in its Roadmap grant program a major initiative called the Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement Information System (PROMIS). PROMIS aims to “reengineer the clinical research enterprise” by creating generic health measures with improved reliability, validity, and precision relative to existing instruments that are premised on classical test theory.2,3 The NIH PROMIS research program (2004- present) has funded over a dozen research sites across the country to engage in fundamental psychometric item bank and scale development. This paper outlines the thinking behind the PROMIS initiative and the psychometric advances applied to the initiative. It also addresses contemporary health care policy mandates relating to PROs as well as opportunities for novel use of PROs beyond outcomes in clinical trials. The goal of this paper is to acquaint the reader with PROMIS and PRO measurement issues and to demonstrate how recent developments have the potential to modernize measurement in clinical trials, facilitate comparative effectiveness research (CER), and improve clinical care.

Patient-Reported Outcomes

PROs are health experiences and evaluations that are assessed by patient report, such as symptoms, assessments of functioning, well-being, health perceptions, and satisfaction with care. Measurement of PROs may be conducted by interview or, more often, by questionnaire on paper, computer, or automated telephone delivery. Clinical research has used PRO measurements for decades, often focusing on a limited set of health concepts4–6 and typically using disease-specific scales for a particular disease, such as arthritis or asthma. Historically, PRO measures have been of variable psychometric quality (measurement characteristics of test), providing limited ability to measure accurately the upper and lower ends of the trait and inadequate content coverage of the measured domain. Inconsistency across studies in the use of scales has led to data silos, that is, the inability to exchange information across systems, posing important challenges for synthesis of results across studies, impeding meta-analyses and comparisons of treatment effectiveness.7

The PROMIS Approach to Scale Development

The item banking approach is the cornerstone of the PROMIS method of PRO development. It begins with defining a domain of interest—i.e., a health attribute that a patient can report, such as pain, physical functioning, anxiety, or social isolation. A systematic series of steps then identifies items that comprehensively measure the domain.8 From PROMIS’s outset, the involvement of patients and content experts has been extensive and has been harnessed to explicate content within domains.9,10 Once a pool of items is created using these qualitative methods, large field tests are conducted and item response theory (IRT) approaches are applied to calibrate the item bank, thereby creating a scoring system to norm responses to the general U.S. population.11 These steps have facilitated significant advances in the content validity and evaluation of coverage of the full range of health experience across the domain (see www.nihpromis.org and the SCIENCE tab for detailed information on PROMIS development procedures). Many legacy instruments suffered from shortcomings in sensitivity at the low and/or high ends of the scale, thus providing limited accuracy for the healthiest and the most affected respondents.12 PROMIS items, however, have undergone rigorous testing for evidence of differences by respondent characteristic (e.g., sex, age, education).13 Final item banks have been calibrated to general U.S. adult and child population norms by using the t-score metric (mean = 50, standard deviation = 10).14 The PROMIS initiative has extended this work with a focus on validation studies across several disease groups and settings. Results to date demonstrate that the PROMIS measures function as well as or better than legacy measures, as demonstrated by improved reliability and evidence of increased sensitivity to clinical change.15

PROMIS uses a domain-specific rather than disease-specific measurement approach.2 Domains are clinically coherent and empirically unidimensional health attributes. The domain-specific approach is based on the perspective that health attributes are not unique to a specific disease, although disorders may have characteristic profiles within domains. The creation of item banks that are not disease-specific permits the comparison of measurements across diseases. Such an approach allows an investigator to determine, for example, the impact of a new medication on fatigue for patients with chronic fatigue syndrome, multiple sclerosis, and cancer. Moreover, it allows for pragmatic research with patients with several diseases, measuring outcomes for domains regardless of specific disease contribution. Pragmatic research is particularly important for CER that examines the relative positive and adverse effects of different treatments for a condition, permitting determination of whether effects vary by patient and disease characteristics.16

A particularly exciting product of the PROMIS IRT approach has been the application of computer-adaptive tests (CAT). Given that each item’s psychometric characteristics are known, computer assessment software can iteratively deliver a brief and targeted sequence of items to an individual based on his or her previous item responses.17 The typical PROMIS CAT involves four to eight items--a minute or two of questions--for a domain. To make CAT administration accessible to clinical researchers, the PROMIS initiative helped develop Assessment Center, a free, online tool that enables the creation of study-specific, secure web sites for administering PROMIS and other PRO short forms and CATs18 (see http://www.nihpromis.org/software/assessmentcenter). Via the Internet, Assessment Center permits accurate assessment of PROs with low patient burden in medical offices, research clinics, and elsewhere. A user manual; online video tutorials on PROMIS, CAT, and Assessment Center; FAQs, and a live customer support help desk are available to support the use of Assessment Center. In addition, a schedule of in-person training workshops is posted on the Assessment Center website (www.assessmentcenter.net).

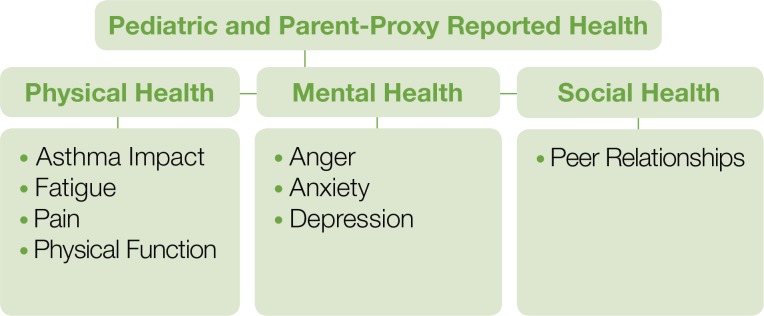

The list of available PROMIS measures continues to expand and includes adult, pediatric, and parent-proxy scales (https://www.assessmentcenter.net/documents/InstrumentLibrary.pdf). In Figures 1 and 2, we display current PROMIS domains for adults and children/adolescents. Several of the domains include subdomains (e.g., pain intensity, pain interference, pain behavior, pain quality).

Figure 1.

PROMIS Adult Domains Available as of 2013

Figure 2.

PROMIS Pediatric (8 to 17 years old) and Parent-Proxy Report (5 to 17 years old) Domains Available as of 2013

With few exceptions, the domains are also available in Spanish; other language translations are in various stages of completion (http://www.nihpromis.org/measures/translations). Ongoing work is dramatically expanding the pediatric measure set to include item banks for pain, stress, positive psychological functioning, and family belonging. Adult item banks for gastrointestinal symptoms and self-efficacy for management of chronic conditions are also under development.

PROMIS researchers are pursuing several avenues of research. The most active area of investigation is clinical validation of existing measures to evaluate their responsiveness to clinical change across a wide range of conditions. With PROMIS measures designed to provide precise measurement across the full range of the health domain, it is possible that ongoing and planned research will show substantial advantages of PROMIS viz-a-viz existing legacy measures. Pediatric measurement is another area of investigation that has received substantial attention and investment. Over the next several years, research will be done to statistically link pediatric and adult measures of the same concept (e.g., anxiety or physical functioning) to provide a single scale that accounts for the pediatric-adult transition, thereby enabling life-course research. Perhaps the most rapidly growing set of research questions relates to the incorporation of PROs into clinical practice, performance assessment, and comparative effectiveness research.

Comparative Effectiveness Research

The 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act set the stage for several important developments for improving both the evidence base and the delivery of medical care in the United States. One such development is increased support for implementation of the electronic health record (EHR). Another development is the mandate that clinical care and clinical research incorporate the patient’s perspective. The mandate followed the 2009 guidance issued by the FDA on necessary criteria for using PROs to support claims for medical product labeling.19 Although not new concepts,20–22 these developments are converging to create a strong interest in patient-monitoring tools in clinical care.

In 2009, Congress appropriated $1.1 billion to prioritize comparative effectiveness research, requiring the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, National Institutes of Health, and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to share the funds in support of CER. The impetus was the recognition that medical providers and patients have little empirical information available to evaluate the comparative benefits of different treatments to inform clinical decisions. Scant data on treatment efficacy, side effects and adverse events for different subgroups of patients (e.g., sex, race, age, medical comorbidities) has further hampered informed decisions.23 Moreover, from a national economic perspective, the nation’s high medical care expenditures, compared with other industrialized countries’ significantly lower expenditures, point to the need to examine the effectiveness of health policy approaches in the United States.24,25 Commentary has suggested the need for dedicated resources and new approaches in research and clinical settings to generate comparative effectiveness data.26

New Roles for PROs

One of the shifts that is taking place with the increased focus on CER and greater inclusion of patients in the dialogue is interest in expanding the scope of clinical outcomes evaluated in trials. For example, while health providers may focus primarily on biological outcomes such as laboratory tests and imaging results, patients are asserting the importance of additional outcomes such as fatigue, sleep quality, ability to engage in valued activities, and depression.27 These health experiences may be measured accurately through patient self-reports, which, alongside biological clinical data, offer opportunities for understanding treatment effects that extend beyond conventional clinical research activity. Assuming that PRO measures are calibrated to a common metric, data may be aggregated across practitioners and clinical sites to enable repurposing of the EHR and PRO data for CER.

Potential of PROs for Improving Clinical Care

Recent developments in health care policy have called for greater engagement of patients in health care, shared decision-making, and patient-centered care.21,22,28,29 Such a policy focus is particularly relevant for chronic diseases where sustained and active patient involvement in daily disease management is a cornerstone of successful care.30,31 PROs may play several roles in clinical care of the patient. They can provide clinical information for medical decision-making. They can identify patients’ areas of concern that should be addressed during a visit but that the provider might not recognize. When completed in advance, PROs can contribute information for pre-planning of visits by the patient care team. They can assist clinicians in monitoring patient status longitudinally, providing an important source of information about treatment response. Moreover, monitoring of patient status on PROs can occur without in-office evaluations, perhaps extending visit intervals in the absence of complications or leading to earlier visits and interventions as indicated.

PROs that measure valued outcomes create an opportunity to clarify patients’ priorities and to prompt expanded and effective discussions about patient preferences for disease management.32,33 Nonetheless, the PRO literature has identified logistical and technical barriers to implementation, such as respondent burden, time constraints, and lack of standardized and individualized assessments.34,35 Practical issues have complicated PRO collection, such as rushed assessments in the waiting room or lack of time during the medical visit.36,37 The PROMIS measures address some of these issues by providing PRO measures that are psychometrically sound, brief (four to eight items/domains), accurate, and available via multiple modes of administration.

Another application is the use of PROs to monitor health over time across a patient population within an electronic record keeping system. There has been increasing interest in utilization of PROs as performance measures (http://www.qualityforum.org/Projects/n-r/Patient-Reported_Outcomes/Patient-Reported_Outcomes.aspx#t=2&s=&p=2%7C). Assessments of PROs can contribute to health care systems’ examination of the system-wide effectiveness of care by considering factors such as ranges and averages of patient outcomes. Systematic PRO collection can also create opportunities for understanding outcomes associated with individual providers.

Despite these advances, there is little evidence to guide the effective integration of PROs into day-to-day patient care. In fact, published research to date is largely disappointing in that PRO administration has mostly yielded increases in chart notations of PRO scores and associated diagnoses with little or no impact on patient care and outcomes.35,38–40 This seemingly meager utility in clinical care has been attributed to a lack of understanding of the factors required to make PRO information comprehensible and useful to health providers and patients.33,34,41,42 Nonetheless, integration of PROs into EHRs is rapidly approaching a tipping point.

PROs in EHR Patient Portals

EHR vendors are starting to recognize the importance of PROs for clinical practice, performance improvement, and research. For example, with its software release in fall 2012, Epic, a leading EHR developer, provided its customers with a novel PRO application (details available in Epic 2012 release notes). Epic developers have made available a library of PRO measures to end-users, who can select from the included instruments or add their own PROs. PROMIS short forms for physical functioning, pain interference, global health, sleep disturbance, fatigue, depression, anxiety, and ability to participate in social roles and activities are being made available for adults. For pediatric patients, PROMIS self-report and parent proxy-report measures are included for mobility, upper-extremity functioning, pain interference, fatigue, depressive symptoms, anxiety, peer relationships, and asthma impact.

Local Epic user groups can program the software to instruct clinical users to define an “event” to direct the administration and reporting of their patients’ PROs. An “event” can be an upcoming healthcare service such as an office visit or surgery, hospitalization, acute illness, a change in health status, or a pre-defined interval, e.g., every 4 months for patients with chronic disease. For example, an orthopedic surgeon and a patient conclude that a knee replacement is the best option. The surgery date can be treated as the “event.” PROMIS measures of physical functioning, pain, and ability to participate in social roles and activities can be scheduled for completion one week pre-operatively, one week post-operatively, and three months post-operatively. Once launched, the application sends the patient an email asking him or her to complete the PROs at the designated times relative to the surgery. The patient accesses the patient portal of the EHR to complete the assessment. These data are scored and stored in the EHR database, and can be retrieved by the surgeon in tabular or graphical form just as laboratory data are currently displayed.

PROMIS instruments are poised for integration into clinical practice by incorporating common data element standards and definitions, including Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes (LOINC) and Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine-Clinical Terms (SNOMED CT). Furthermore, PROMIS instruments that are captured within Assessment Center can use Health Level Seven (HL7) messaging, the most widely used standard for exchanging health care data within and between health care organizations.

Systematic and uniform assessment of PROs in a structured data-capture system will enable the use of patient self-reports for CER—whether for N-of-1 trials aggregated to make inferences across a population or for more traditional CER designs. The ability to conduct CER with observational data is strengthened when PRO and clinical data are married in the same patient record, with data displayed in a clear and interpretable format to separate visit-to-visit variation from meaningful change. The technological potential is likely to continue advancing with the generation of creative solutions for integrating the broad and multisource facets of patient data.43

Examples of Clinical Sites Using PROMIS PROs

As the potential for benefit is recognized, there increasing instances of PROs being incorporated into clinical care. Several medical centers that have prioritized the improvement of health outcomes have introduced PROs into clinical settings. Cleveland Clinic, Northwestern University, University of Washington, and Cincinnati Children’s Hospital are examples of institutions that have systematically integrated PROs, including PROMIS, into clinical settings. At Cleveland Clinic Neurological Institute patients are scheduled to arrive 20 minutes before their appointment to complete health status measures including PROMIS that are integrated into the electronic health record.44 At the Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center of Northwestern University, PROMIS CATs are used in an initiative to screen for distress and other outcomes as well as conduct a needs assessment in gynecologic oncology patients. Patients have the opportunity to complete the measures before their visit via the patient portal of the EHR. Scores that exceed an established threshold or requests for services generate messages within the EHR for the appropriate clinical care team member, e.g., a social worker. The Lurie Center’s project addresses an accreditation standard set by the American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer for routine screening of distress.45 PRO measures also have been integrated into clinic visits at University of Washington outpatient HIV Clinic by allotting time prior to the visit for assessment. As a result, PRO measures have drawn provider attention to depressive symptoms, poor medication adherence, and at-risk behaviors.46 In pediatric care, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center is using PROs in 12 subspecialty clinics, with more widespread rollout planned to clinics system-wide. The initiative will satisfy several goals. It will serve the clinical needs of subspecialty clinics by, for example, using the PROMIS pain interference measure in the rheumatology clinic. Over time, it will also monitor the health of the medical center’s population as a whole by assessing general health-related quality of life (personal communication with Evaline Alessandrini, MD, James M. Anderson Center for Health Systems Excellence, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, March 2013).

The State of PRO Integration Science

While these initiatives are exciting, it remains to be seen whether integration of PROs into the clinical encounter will yield better patient outcomes than the more traditional exchange of information between patient and provider. There is some evidence, however, from a research setting that PROMIS items can be used to associate change in treatment directly to outcome, thus helping to identify the most effective treatment.

Using individual patients as the unit of measure, Kaplan and colleagues used PROMIS items to associate change in treatment for inflammatory bowel disease with outcomes.47 Using mobile and web-based data collection of PROMIS and other measures, they generated a graphical display of PRO data with statistical process control charts to determine when changes in medical therapy were reflected in meaningful changes in PROs. They used the data to identify the most effective treatment for a given patient in order to deliver personalized care. Crosby and colleagues are using PROMIS measures to assess the impact on health outcomes of a self-management program for adolescents with sickle cell disease. The program uses the EHR patient portal. It conducts PRO assessment and provides patients with resources for general disease-related information, access to their own laboratory data, and self-management tips. It also enables patients to provide health updates (weekly) via emails to their health care team. Included among outcome measures are PROMIS pain interference and fatigue scores [personal communication, Lori Crosby, Psy.D., Behavioral Medicine and Clinical Psychology, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, March 2013].

Some studies have used randomized, controlled designs to compare outcomes when PROs are and are not integrated into care. When we look at this research, the majority of trials only engaged the patient on a single occasion for assessment.36,48 This inhibits provider monitoring of patients’ evolving health status and assumes that clinical decision-making can be based on a single evaluation.39,49,50 A review showed that 50 percent of single-feedback PRO trials (n = 14) demonstrated a significant increase only in chart notations and diagnoses, with no evidence of treatment plan changes. Only 2 of 11 studies found a significant impact on referrals and additional consultations.35 Potentially, the benefits of PROs can be enhanced if their implementation mirrors the process of clinical decision-making that occurs in chronic disease care, that is, longitudinally.48 One of the most common barriers to successful PRO integration is providers’ failure to value the PRO information for the management of their patients. Patient PRO reports need to be presented in a clinically relevant format with clear interpretive guidelines, and they must add value to the clinical encounter, be cost-effective, and should not impede the clinical workflow.32,33 Prior studies have presented PRO information to clinicians in various ways; however, provider preferences for particular formats of PRO delivery and their ease of interpretation have not been examined.41 In fact, EHR implementation is advancing ahead of systematic evaluation of usability by patients and providers.51 Qualitative investigations are needed to characterize the needs of health care providers to facilitate PRO integration,52 along with systematic clinical trials that study the efficacy of PRO integration.

Summary

PROs have rapidly increased in significance as the national dialogue on health policy has focused more on comparative effectiveness research, incorporating the patient perspective into medical decision-making and evaluating broader treatment outcomes. The NIH PROMIS initiative provides state-of-the art item banks for adult, pediatric, and parent-proxy measurement of physical, mental, and social health domains. The measures may be administered rapidly as short forms or computer-adaptive tests. PROMIS tools are being adopted in clinical trials, comparative effectiveness research, and also in clinical care by hospitals and electronic health record vendors. Use of PROs offers the potential to broaden the focus of clinical encounters to include additional health experiences of importance to the patient and to provide a means for monitoring patient status and treatment outcomes longitudinally through patient portals in the EHR. Today’s focus on quality of patient care and clinical outcomes will undoubtedly incorporate PROs into evaluations of system-wide and individual provider treatment outcomes. Systematic studies that investigate the best methods for using PROs in clinical care and for evaluating their impact on patient outcomes are now needed.

Acknowledgments

PROMIS® was funded with cooperative agreements from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Common Fund Initiative (Northwestern University, PI: David Cella, PhD, U54AR057951, U01AR052177; Northwestern University, PI: Richard C Gershon, PhD, U54AR057943; American Institutes for Research, PI: Susan (San) D Keller, PhD, U54AR057926; State University of New York, Stony Brook, PIs: Joan E Broderick, PhD, and Arthur A Stone, PhD, U01AR057948, U01AR052170; University of Washington, Seattle, PIs: Heidi M Crane, MD, MPH, Paul K Crane, MD, MPH, and Donald L Patrick, PhD, U01AR057954; University of Washington, Seattle, PI: Dagmar Amtmann, PhD, U01AR052171; University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, PI: Darren A DeWalt, MD, MPH, U01AR052181; Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, PI: Christopher B Forrest, MD, PhD, U01AR057956; Stanford University, PI: James F Fries, MD, U01AR052158; Boston University, PIs: Stephen M Haley, PhD, and David Scott Tulsky, PhD (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor), U01AR057929; University of California, Los Angeles, PIs: Dinesh Khanna, MD (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor) and Brennan Spiegel, MD, MSHS, U01AR057936; University of Pittsburgh, PI: Paul A Pilkonis, PhD, U01AR052155; Georgetown University, PIs: Carol M Moinpour, PhD, (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle) and Arnold L Potosky, PhD, U01AR057971; Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, PI: Esi M Morgan DeWitt, MD, MSCE, U01AR057940; University of Maryland, Baltimore, PI: Lisa M Shulman, MD, U01AR057967; and Duke University, PI: Kevin P Weinfurt, PhD, U01AR052186) NIH Science Officers on this proMect included Deborah Ader, PhD, Vanessa Ameen, MD, Susan C]aMkowski, PhD, Basil Eldadah, MD, PhD, Lawrence Fine, MD, DrPH, Lawrence Fox, MD, PhD, Lynne Haverkos, MD, MPH, Thomas Hilton, PhD, Laura Lee Johnson, PhD, Michael Kozak, PhD, Peter Lyster, PhD, Donald Mattison, MD, Claudia Moy, PhD, Louis Quatrano, PhD, Bryce Reeve, PhD, William Riley, PhD, Peter Scheidt, MD, Ashley Wilder Smith, PhD, MPH, Susana Ser-rate-Sztein, MD, William Phillip Tonkins, DrPH, Ellen Werner, PhD, Tisha Wiley, PhD, and James Witter, MD, PhD. The contents of this paper do not necessarily represent an endorsement by the U. S. government or PROMIS. See www.nihpromis.org for additional information on the PROMIS® initiative. The authors are grateful to William Riley, PhD, and Kevin Weinfurt, PhD, for their helpful reviews of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Disciplines

Health Services Research

References

- 1.Cella D, Yount S, Rothrock N, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS): progress of an NIH Roadmap cooperative group during its first two years. Med Care. 2007;45(5 Suppl 1):S3–S11. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000258615.42478.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Magasi S, Ryan G, Revicki D, et al. Content validity of patient-reported outcome measures: perspectives from a PROMIS meeting. Qual Life Res. 2012;21(5):739–746. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-9990-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fries JF, Bruce B, Cella D. The promise of PROMIS: using item response theory to improve assessment of patient-reported outcomes. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2005;23(5 Suppl 39):S53–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Litcher-Kelly L, Martino S, Broderick J, Stone A. A systematic review of measures used to assess chronic pain in randomized clinical trails and controlled trials. Journal of Pain. 2007;8(12):906–913. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rahimi K, Malhotra A, Banning AP, Jenkinson C. Outcome selection and role of patient reported outcomes in contemporary cardiovascular trials: systematic review. Bmj. 2010;341:c5707. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c5707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hewlett S, Carr M, Ryan S, et al. Outcomes generated by patients with rheumatoid arthritis: how important are they? Musculoskeletal Care. 2005;3(3):131–142. doi: 10.1002/msc.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Griffith L, van den Heuvel E, Fortier I, et al. Harmonization of cognitive measures in individual participant data and aggregate data meta-analysis. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2013. AHRQ Publication 13-EHC040-EF. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeWalt DA, Rothrock N, Yount S, Stone AA. Evaluation of item candidates: the PROMIS qualitative item review. Medical Care. May. 2007;45(5 Suppl 1):S12–21. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000254567.79743.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amtmann D, Cook KF, Johnson KL, Cella D. The PROMIS initiative: involvement of rehabilitation stakeholders in development and examples of applications in rehabilitation research. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92(10 Suppl):S12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2011.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Riley WT, Rothrock N, Bruce B, et al. Patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) domain names and definitions revisions: further evaluation of content validity in IRT-derived item banks. Qual Life Res. 2010;19(9):1311–1321. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9694-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reeve BB, Hays RD, Bjorner JB, et al. Psychometric evaluation and calibration of health-related quality of life item banks: plans for the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Med Care. 2007;45(5 Suppl 1):S22–31. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000250483.85507.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fries JF, Cella D, Rose M, Krishnan E, Bruce B. Progress in assessing physical function in arthritis: PROMIS short forms and computerized adaptive testing. J Rheumatol. 2009;36(9):2061–2066. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.090358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Teresi JA, Ocepek-Welikson K, Kleinman M, et al. Analysis of differential item functioning in the depression item bank from the Patient Reported Outcome Measurement Information System (PROMIS): An item response theory approach. Psychol Sci Q. 2009;51(2):148–180. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rothrock NE, Hays RD, Spritzer K, Yount SE, Riley W, Cella D. Relative to the general US population, chronic diseases are associated with poorer health-related quality of life as measured by the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(11):1195–1204. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fries JF, Krishnan E, Rose M, Lingala B, Bruce B. Improved responsiveness and reduced sample size requirements of PROMIS physical function scales with item response theory. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13(5):R147. doi: 10.1186/ar3461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Conway PH, Clancy C. Comparative-effectiveness research--implications of the Federal Coordinating Council’s report. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(4):328–330. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0905631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choi SW, Reise SP, Pilkonis PA, Hays RD, Cella D. Efficiency of static and computer adaptive short forms compared to full-length measures of depressive symptoms. Qual Life Res. 2010;19(1):125–136. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9560-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gershon RC, Rothrock N, Hanrahan R, Bass M, Cella D. The use of PROMIS and assessment center to deliver patient-reported outcome measures in clinical research. J Appl Meas. 2010;11(3):304–314. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services FaDA Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: Use in Medical Product Development to Support Labeling Claims. Guidance for Industry. 2010 doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-79. Accessed September 2, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ellwood P. Shattuck lecture - outcomes management. A technology of patient experience. New England Journal of Medicine. 1998;318:1549–1556. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198806093182327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stewart M. Towards a global definition of patient centred care. Bmj. 2001;322(7284):444–445. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7284.444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Higginson IJ, Carr AJ. Measuring quality of life: Using quality of life measures in the clinical setting. Bmj. 2001;322(7297):1297–1300. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7297.1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Institute of Medicine Initial National Priorities for Comparative Effectiveness Research. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anderson GF, Frogner BK, Johns RA, Reinhardt UE. Health care spending and use of information technology in OECD countries. Health Aff (Millwood) 2006;25(3):819–831. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.3.819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mushlin AI, Ghomrawi H. Health care reform and the need for comparative-effectiveness research. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(3):e6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0912651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tunis SR, Benner J, McClellan M. Comparative effectiveness research: Policy context, methods development and research infrastructure. Stat Med. 2010;29(19):1963–1976. doi: 10.1002/sim.3818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kirwan JR, Hewlett SE, Heiberg T, et al. Incorporating the patient perspective into outcome assessment in rheumatoid arthritis--progress at OMERACT 7. J Rheumatol. 2005;32(11):2250–2256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roter D. The enduring and evolving nature of the patient-physician relationship. Patient Educ Couns. 2000;39(1):5–15. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(99)00086-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Epstein RM, Fiscella K, Lesser CS, Stange KC. Why the nation needs a policy push on patient-centered health care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29(8):1489–1495. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Michie S, Miles J, Weinman J. Patient-centredness in chronic illness: what is it and does it matter? Patient Educ Couns. 2003;51(3):197–206. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(02)00194-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iversen MD, Hammond A, Betteridge N. Self-management of rheumatic diseases: state of the art and future perspectives. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(6):955–963. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.129270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lohr KN, Zebrack BJ. Using patient-reported outcomes in clinical practice: challenges and opportunities. Qual Life Res. 2009;18(1):99–107. doi: 10.1007/s11136-008-9413-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fung CH, Hays RD. Prospects and challenges in using patient-reported outcomes in clinical practice. Qual Life Res. 2008;17(10):1297–1302. doi: 10.1007/s11136-008-9379-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Osoba D. Translating the science of patient-reported outcomes assessment into clinical practice. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2007;(37):5–11. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgm002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Valderas JM, Kotzeva A, Espallargues M, et al. The impact of measuring patient-reported outcomes in clinical practice: a systematic review of the literature. Qual Life Res. 2008;17(2):179–193. doi: 10.1007/s11136-007-9295-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Greenhalgh J. The applications of PROs in clinical practice: what are they, do they work, and why? Qual Life Res. 2009;18(1):115–123. doi: 10.1007/s11136-008-9430-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rose M, Bezjak A. Logistics of Collecting Patient-Reported Outcomes (PROS) in Clinical Practice: An Overview and Practical Examples. Quality of Life Research. 2009;19(1):125–136. doi: 10.1007/s11136-008-9436-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Espallargues M, Valderas JM, Alonso J. Provision of feedback on perceived health status to health care professionals: a systematic review of its impact. Med Care. 2000;38(2):175–186. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200002000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Snyder CF, Aaronson NK. Use of patient-reported outcomes in clinical practice. Lancet. 2009;374(9687):369–370. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61400-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kazis LE, Callahan LF, Meenan RF, Pincus T. Health status reports in the care of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Epidemiol. 1990;43(11):1243–1253. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(90)90025-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Greenhalgh J, Long AF, Flynn R. The use of patient reported outcome measures in routine clinical practice: lack of impact or lack of theory? Soc Sci Med. 2005;60(4):833–843. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Snyder C, Brundage M. Integrating patient-reported outcomes in healthcare policy, research and practice. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2010;10(4):351–353. doi: 10.1586/erp.10.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.El Fadly A, Rance B, Lucas N, et al. Integrating clinical research with the Healthcare Enterprise: from the RE-USE project to the EHR4CR platform. J Biomed Inform. 2011;44(Suppl 1):S94–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Katzan I, Speck M, Dopler C, et al. The Knowledge Program: an innovative, comprehensive electronic data capture system and warehouse. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2011;2011:683–692. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wagner LI, Spiegel D, Pearman T. Using the science of psychosocial care to implement the new american college of surgeons commission on cancer distress screening standard. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11(2):214–221. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2013.0028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fredericksen R, Crane P, Tufano J, et al. Integrating a web-based, patient-administered assessment into primary care for HIV-infected adults. Journal of AIDS and HIV Research. 2012;4(2):47–55. doi: 10.5897/jahr11.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kaplan HC, Adler J, Saeed SA, Aylward B, Margolis PA. Case Studies of N-of-1 Trials: Using Quality Improvement Science to Improve Patient Symptoms. Academy for Healthcare Improvement: Advancing the Methods for Healthcare Quality Improvement Research; Arlington, VA: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Marshall S, Haywood K, Fitzpatrick R. Impact of patient-reported outcome measures on routine practice: a structured review. J Eval Clin Pract. 2006;12(5):559–568. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2006.00650.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lelie A. Decision-making in nephrology: shared decision making? Patient Educ Couns. 2000;39(1):81–89. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(99)00093-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gravel K, Legare F, Graham ID. Barriers and facilitators to implementing shared decision-making in clinical practice: a systematic review of health professionals’ perceptions. Implement Sci. 2006;1:16. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-1-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Edwards PJ, Moloney KP, Jacko JA, Sainfo F. Evaluating usability of a commercial electronic health record: A case study. Int. J. Human-Computer Studies. 2008;66:718–728. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Snyder CF, Jensen RE, Geller G, Carducci MA, Wu AW. Relevant content for a patient-reported outcomes questionnaire for use in oncology clinical practice: Putting doctors and patients on the same page. Qual Life Res. 2010;19(7):1045–1055. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9655-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]