Abstract

Background:

In October 2013, the Public Health Informatics Institute (PHII) and Institute for Alternative Futures (IAF) convened a multidisciplinary group of experts to evaluate forces shaping public health informatics (PHI) in the United States, with the aim of identifying upcoming challenges and opportunities. The PHI workshop was funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation as part of its larger strategic planning process for public health and primary care.

Workshop Context:

During the two-day workshop, nine experts from the public and private sectors analyzed and discussed the implications of four scenarios regarding the United States economy, health care system, information technology (IT) sector, and their potential impacts on public health in the next 10 years, by 2023. Workshop participants considered the potential role of the public health sector in addressing population health challenges in each scenario, and then identified specific informatics goals and strategies needed for the sector to succeed in this role.

Recommendations and Conclusion:

Participants developed recommendations for the public health informatics field and for public health overall in the coming decade. These included the need to rely more heavily on intersectoral collaborations across public and private sectors, to improve data infrastructure and workforce capacity at all levels of the public health enterprise, to expand the evidence base regarding effectiveness of informatics-based public health initiatives, and to communicate strategically with elected officials and other key stakeholders regarding the potential for informatics-based solutions to have an impact on population health.

Keywords: public health informatics, information infrastructure, collaborative approaches, aspirational futures approach

Introduction

Background

Public health informatics (PHI) has been described as the field that optimizes the use of information to improve individual health, health care, public health practice, biomedical and health services research, and health policy.1,2 PHI operates at the intersection of public health and computer science. It relies on information technology (IT) systems to help address the core functions of public health as defined by the Institute of Medicine: assessment of population health, policy development, and assurance of the availability of high-quality public health services.3 It is thus related to but distinct from biomedical and clinical informatics, which seek to improve the health of individuals within the health care system.

The information infrastructure for public health comprises information and communication technologies (ICT), including hardware, software, services, and devices; a skilled workforce to access, develop, implement, and use them; and organizations that create and enforce standards and policies, including those aimed at improving population health.4 In part because of the year-to-year and categorical nature of public health funding, PHI infrastructure is significantly underdeveloped and currently contributes mostly to the operational rather than to the strategic function of public health.5

The Institute of Medicine (IOM)6 suggests that “a new generation of intersectoral partnerships” is needed to help public health achieve its mission.7 From an informatics perspective, public health, public and private health care systems, insurers, employers, and city government agencies could be doing much more to share data and collaborate in other ways to achieve population health goals, improve efficiency of service delivery, manage costs, promote health equity, and reduce health disparities.

This two-day workshop in 2013, Public Health Informatics 2023, was funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation as part of its larger strategic planning process for public health and primary care. Nine invited experts from different public and private settings analyzed and discussed the implications of four scenarios for the United States economy, health care system, and IT sector, and their potential impacts on public health in the next 10 years (by 2023). Their discussions provided an unusual opportunity to reflect on ways to drive and support improvements in population health by optimizing information and communication systems, with the larger goal of improving the flow of information along the continuum between public health practice, policy, and research. Recommendations generated by the workshop were intended to stimulate discussions and promote action by public and private sector stakeholders, including public health officials, health care system leaders, and key members in the broader fields of public health and clinical informatics. Ideally, these actions will lead to increased investments in PHI, increased access to existing and new forms of data, implementation of best practices and standards, and expanded interagency collaborations to reduce the economic and social burdens resulting from poor health at the population level.

Workshop Context

Public Health and Health Care Systems

In contrast to health care delivery systems, which provide care and treatment for individuals, public health systems seek to advance the health of geospatially defined populations over time in a variety of settings; to focus more on disease prevention and health protection than on treatment; and to develop and apply evidence-based preventive interventions that reduce disease, injury or disability.8 Public health operates substantially within a governmental rather than a private context, even though nongovernmental entities deliver limited public health services for circumscribed subpopulations such as low-income communities or employees.

In contrast to public health, private health plans or health care delivery institutions might define a population as all individuals who are enrolled in a plan or receive health care services at a particular site, or might define subpopulations among those who are enrolled (e.g., children with asthma or adults with congestive heart failure). In order to manage the health of these defined populations, however defined, health care system organizations might also segment or group their members according to levels of social support, access to transportation, health and technology literacy, and other factors that will influence an individual’s access to care and response to care plans. These factors might be aggregated to facilitate the efficient and effective allocation of resources,9 such as by identifying older adults who will need assistance at home after being discharged from inpatient or long-term care to help them avoid a preventable readmission.

It has been long recognized that population health outcomes are influenced by multiple determinants outside of health care, including social, economic, educational, environmental, and other influences.10 In recent years, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) has created controversy about how populations are to be defined in the context of population health, and has raised questions about how traditional core functions of public health will be affected by new risk-bearing delivery models such as Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) and the presence of other new private-sector players providing prevention and monitoring programs.

Currently, integrated delivery systems using electronic health data may or may not include data collected by the local public health agency, such as childhood immunization records or registries of flu or pneumonia shots. And health care delivery systems rarely share clinical data that is not mandated by law with public health entities for tracking, planning, and research.

Public Health Informatics (PHI)

The health information ecosystem is evolving unevenly. Progress has been rapid in the health care delivery system and slow in public health, increasing the disparity in informatics capabilities.11 For example, most of the projected $2.7 billion growth in health IT spending by state and local governments between 2012 and 2017 will focus on improving systems for means-testing benefits programs; combating fraud, waste, and abuse; and health insurance exchange and quality programs, not on building infrastructure.12 In contrast, health IT spending by providers, payers, and physician groups is projected to grow $5.3 billion over the same period.13

Strategic investments resulting from the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act of 2009, and particularly the meaningful use program, have sought to strengthen the health information infrastructure for the health care delivery system to reduce costs and improve health outcomes of patients. Financial incentives for meaningful use of health IT have rapidly accelerated the adoption of electronic health records (EHRs) for clinical purposes.

In sharp contrast to this IT funding for health care system performance, investment equivalents of HITECH under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) have not been made to strengthen the public health informatics infrastructure, and only limited advances have been made to leverage the health care delivery system informatics investments for public health use. Information systems in public health agencies (PHAs) have largely been built and maintained by disease- or subgroup-specific programs driven by categorical funding streams (e.g., HIV and AIDS, asthma, immunizations, maternal, and child health programs). Most have been standalone systems that are not standardized or interoperable,14 meaning that information cannot be easily exchanged across systems without some kind of prior data use agreement.

Using part of the post-9/11 and post-Katrina funds from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), many public health departments developed modest information-sharing capabilities to promote biosurveillance and emergency preparedness and response. For example, many adjoining counties have developed mutual assistance agreements to share assets and resources for emergency response. However, the local or regional governance structures emerging from these resource-sharing arrangements have not, for the most part, been generalized to ongoing health data exchange and informatics expertise.

More recently, resources have been made available to increase such data sharing, including the formation of Health Information Exchanges (HIEs). The HIE toolkit (https://www.google.com/?gws_rd=ssl#q=HIMSS+and+NACCHO+HIE+toolkit) released in 2014 by the National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO) and the Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society (HIMSS) provides practical guidance to local health departments about how to receive and analyze electronic health data to improve surveillance and disease response. Similarly, the Electronic Data Methods (EDM) Forum Governance Toolkit has several guidance documents on stake-holder engagement and the evolution of data sharing in communities.15 Additionally, a case study on how the Beacon Communities initiated and managed HIE is particularly instructive.16

Currently, only a few local health agencies have data use agreements with health care plans that allow them to access and aggregate the EHR data for health planning or surveillance purposes. Denver Health, New York City Health Department’s Primary Care Information Project, and the Seattle & King County Public Health Department have, for example, developed strategic data sharing agreements among health care and public health systems, and have the appropriate capacity for data analytics aimed at informing population health surveillance and policy evaluation. However, most local health agencies do not have such arrangements and are limited by infrastructure, budget, staffing shortages, and lack of skills to work with large data sets.

In the larger economic and social environment, PHAs in the United States are seen by elected officials as health crisis response and regulatory agencies that inspect restaurants, manage outbreaks, provide safety net services for uninsured and low-income individuals, and engage in campaigns or make policies to change personal health behavior. Rarely do elected officials consider PHAs when discussing innovations in health IT. Specifically, the role of informatics in informing population health surveillance, public health preparedness and emergency response, or strategic monitoring of health care quality across delivery systems is still largely unknown outside the public health system.

Workforce

For much of the health and public health workforce, informatics is not viewed as an independent profession, but rather as “cross-training” between a content domain (such as public health or medicine) and an application of information sciences.17 As a field, PHI is virtually unknown to the general public and the majority of public policymakers. Even within informatics, other content domains, particularly medicine, nursing, biomedicine, and translational research, overshadow PHI.

Formal education and training programs in informatics follow the core competencies in PHI (http://www.cdc.gov/informaticscompetencies/) developed over a decade ago through a highly collaborative process. However, because informatics is a newly emerging area of practice, the majority of practicing informaticians have not had standardized, formal education in informatics and have gained their competencies in other ways, including certification programs and on-the-job training.

Workforce forecasts have estimated that an additional 250,000 public health workers will be needed in the public health sector by 2020 to maintain current public health capacity,18 which has been significantly downsized due to budget reductions, especially since the 2009 United States economic recession.19 While forecasts for certain types of public health employees exist, forecasts for informatics-trained employees have not been developed. PHAs have had particular trouble recruiting and retaining skilled informaticians—especially those with a background in biostatistics or epidemiology—to help with surveillance, reporting, and other data aggregation requirements, due to shortages of trained health IT professionals and higher salaries in the private health care delivery system.20

The Aspirational Futures Approach

Why Scenarios?

Scenarios are a powerful method for systematically addressing an uncertain future. Scenarios are parallel stories describing different ways in which the future might unfold. Under circumstances where there are many uncertainties and complexities, scenarios can help define plausible alternative paths by clarifying underlying assumptions, considering systems that surround and influence a field or topic, identifying drivers of change, and helping to think about potential outcomes in a larger space of possibilities. People who work through a group process with scenarios tend to find more creative options by reevaluating assumptions and considering emerging issues than those who plan based only on the past and present.

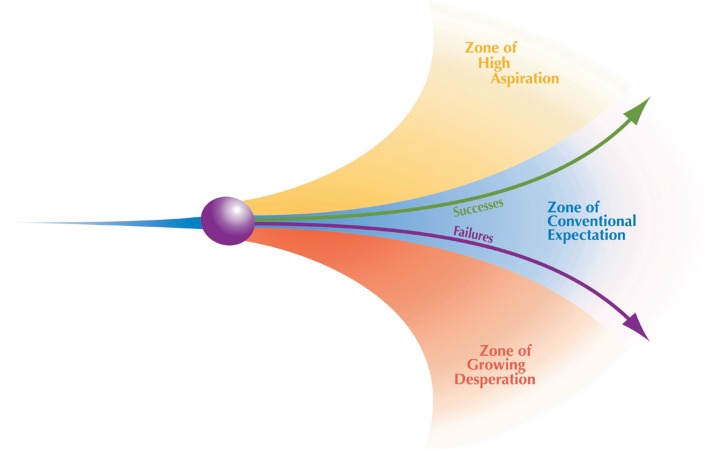

Over the past three decades, the Institute for Alternative Futures (IAF) has developed an “Aspirational Futures” approach in which scenarios are developed for three zones (Figure 1):

A “zone of conventional expectation” reflecting the extrapolation of known trends, the expectable future if these trends continue (Scenario 1: Information for Health Action);

A “zone of growing desperation,” which presents a set of plausible challenges that an organization or field may face, a challenging future (Scenario 2: Write-Only Misinformatics); and

A “zone of high aspiration” in which a critical mass of stake-holders pursues visionary strategies and achieves surprising success (Scenario 3: Pearl Harbor for Public Health and Scenario 4: Everybody Is an Informatician). Two scenarios are developed in this zone in order to offer two alternative pathways to highly preferable or visionary futures.

Figure 1.

IAF’s Aspirational Futures Technique

In developing the PHI scenarios, IAF and Public Health Informatics Institute (PHII) staff identified drivers of change at three levels:

-

Macro Environment Level

National economic and political forces;

New and emerging diseases, syndemics, and extreme weather events;

Social and demographic trends; and

Public investments in infrastructure.

-

Health Care and Public Health Level (the larger industry or sector in which PHI operates)

The role of the health care system in improving population health;

New competitors for PHI functions, such as ACOs and citizen scientists; and

Increased level of automation of restaurant and other inspections.

-

PHI Level, which was the specific focus of the workshop

Multiple sources of data, including EHRs;

Capacity for big data analytics for surveillance, planning, and other core functions;

Evidence of effectiveness of public health interventions through measuring health outcomes;

Public perceptions of PHAs and general understanding of informatics;

Workforce development issues; and

Governance issues, including mutual assistance agreements.

At each of the three levels, expectable (status quo), challenging, and surprisingly successful alternative forecasts for each of the drivers of change were developed. Scenario dimensions are presented in Appendix A.

The Process

After the scenarios were presented to workshop participants, they rated how probable and preferable each scenario was (Table 1). The workshop participants were instructed to select a value for the likelihood for each scenario, but the percentages across scenarios did not need to total 100 percent. The median value for the likelihood is displayed in Table 1. Similarly, participants identified the “the preferability” of each scenario (from 0 to 100), and the results are shown in the right-hand side of the table. Table 1 reflects the median value to assure the measure was not skewed by outliers, although the median and mean values were very similar.

Table 1.

Participants’ Ratings of the Likelihood and Preferability of the Four Scenarios

| Likelihood (%) | Preferability (%) | |

|---|---|---|

|

Scenario 1: Information for Health Action (Status quo continues, expectable) |

55% | 37.5% |

|

Scenario 2: Write-Only Misinformatics (Challenging) |

30% | 0% |

|

Scenario 3: Pearl Harbor for Public Health (Aspirational and successful crisis response) |

40% | 80% |

|

Scenario 4: Everybody Is an Informatician (Aspirational and successful) |

50% | 82.5% |

Overall, participants rated Scenario 1 (Information for Health Action) more likely to play out, as it closely resembles the current state of PHI, but they thought the optimistic scenarios were not implausible. The group expressed a slight preference for Scenario 4 (Everybody Is an Informatician) over Scenario 3 (Pearl Harbor for Public Health). The difference in preferences for Scenarios 3 and 4 reflects a difference in opinions about how much the field can transform itself without a major crisis—such as Katrina or Sandy superstorm events, Ebola virus outbreaks, or pandemics— to drive change.

Through a series of small- and full-group discussions, participants discussed the four scenarios and the issues they raised. In the course of discussions, participants considered issues raised by a scenario, as well as recommendations. These recommendations included strategies and concrete actions that should be taken over the 10 years after the 2013 workshop by public health practitioners, government, private funders, and others to advance the health of populations by anticipating challenges and leveraging PHI strengths in innovative ways.

In the full-group discussions, participants identified common themes for PHI as well as “robust” recommendations that appeared in two or more scenarios. These were synthesized into a set of key recommendations. These recommendations were further distilled and synthesized by the authors.

Major Themes Emerging from the Scenario Discussions

The participants expressed a sense of urgency about developing a coordinated strategy to connect “siloes” or pockets of information that need to be aggregated to help inform the larger public health enterprise. Their approach to the recommendations grew from the following shared assumptions or themes.

Theme 1. Public health has unique strengths as a trusted information broker and neutral convener that will serve the public interest

Participants agreed that PHAs will be critical players in providing vision and leadership to convene stakeholders and support collaborative action at national, state, and local levels, including through the use of PHI. They also recognized that an important role for private sector organizations is to advance population health. With the ACA strongly emphasizing health care delivery system reform to achieve population health, PHAs can provide resources and expertise to help aggregate and analyze information from across public health, human services, education, and other public sector systems and to help foster collaboration across different and sometimes competing systems. Participants also recognized that PHA leadership will need to modify some traditional practices of mandated data collection and government ownership to embrace more collaborative data integration strategies. As a trusted information broker and neutral convener, PHAs are already helping to identify overlaps, gaps, and inconsistencies across data sources in many locations,21 including Denver, Indianapolis, New York City, San Diego, Seattle, and in other Beacon Communities.22,23

Theme 2. There will be tremendous variation in the ways PHAs respond to the informatics challenges of the post-ACA environment

Local PHAs will use a variety of strategies and tactics to develop new partnerships with other public agencies and the private sector. The variability in approaches across the country is a key reason why informatics standards are so important. Generally, participants agreed that innovation is more likely to come from local PHAs than from state and federal agencies because local PHAs are closest to the populations they serve and are most aware of immediate public health and health care needs. Some participants felt that certain forms of innovation were more likely to come from local health departments (local PHAs) in urban areas where mayors are leading transformation for economic development and sustainability, where health care delivery system membership is more complex, and where health disparities affect the largest number of people. Others made the case that rural PHAs will also innovate out of necessity—having fewer resources and needing to retain employment opportunities for their scarce workforce—while having first-hand knowledge of local needs.

Some participants noted that the use of IT may have the potential to further exacerbate health disparities because of the lack of access to technology among many individuals in low-income, underserved communities. However, others pointed out the evidence that mobile phones have helped improve outreach and surveillance in global health projects and United States-based initiatives with lower income populations, such as Project Health-Design, and that mobile technologies show promise in reducing disparities in access to health information.26

Theme 3. Public health practice will require better measures, a stronger evidence base, and strategic communications about its demonstrated ability to have an impact on population health

The deliberate practice of employing evidence-based public health began to evolve about 10 years ago, at the same time as discussions evolved about evidence-based medicine, nursing, and related health professions. Its key components include making decisions based on the best available evidence, using data and information systems systematically, engaging communities in decision-making, and disseminating lessons learned.24 More recently, the term “learning health system” has been used to refer to a continuous improvement and innovation process in health and health care.25 Both terms emphasize demonstrating the effectiveness of health care services and public health activities at achieving population health improvements and communicating these successes to policymakers and funders to build awareness about where future investments are needed. Public health practitioners in general and PHI proponents in particular have struggled to define and communicate the value they provide, and they need to do more to frame initiatives in the context of returns on investments to critical stakeholders. However, the common goal is for diverse stakeholders to “connect and harmonize” their efforts to use health data to improve quality and health outcomes at reduced costs.26

Theme 4. Current informatics workforce shortages are large, and approaches to address this are inadequate

Since developing its core competencies more than a decade ago, the PHI field has been striving for professional distinction, recognition, and parity of visibility and funding with other areas of informatics, including clinical and biomedical research informatics. Some practitioners are concerned that if public health does not provide appropriate value added services in using new data sources and new analytics opportunities under the ACA, health care providers and other data holders will engage private sector information companies to provide the analyses and will bypass sharing the data with local public health authorities. The shortages of public health informaticians in the current workforce together with the failure of most public health schools to adopt informatics as a universal public health core competency make this more likely. Two of the workshop scenarios addressed the entry of citizen scientists and other nontraditional workers to help meet the informatics shortfall, which may become a reality in an increasing number of jurisdictions.

Recommendations

These recommendations focus on the specific role of informatics in advancing evidence-based public health practice through stake-holder engagement, infrastructure development, data sharing, development of new data sources, dissemination of best practices, and workforce development. They reinforce themes and concepts in key public health guidance documents, particularly the Public

Health Accreditation Board’s Standards and Measures document (www.phaboard.org) and the capabilities covered in the Public Health Information Network (PHIN) strategic plan (http://www.cdc.gov/phin/). These recommendations can also aid in filling information gaps in population health measures and for Public Health Systems and Services Research (PHSSR).

Activate stakeholder engagement and expand data sharing with traditional and new partners to improve population health.

As a generally trusted information broker and neutral convener, PHAs must reach out to and convene a variety of public and private sector partners to develop a unified approach to community information sharing.

Local PHAs should convene and engage with local health care providers, other local government agencies, and community leaders to build consensus on high-priority health problems and to assess the extent to which these problems are rooted in social determinants of health in their specific communities. Partners could include public agencies—such as Medicaid, social services, criminal- and juvenile justice, transportation, housing, urban planning, and economic development agencies—major health systems, community-based clinics, private-sector employers, and local business leaders; and religious and other community leaders. Local PHAs should employ community-based participatory research principles and governance best practices to engage key leaders in participating organizations from the outset. This approach is more likely to foster trust and ownership for all partners by recognizing the value of different perspectives in the new collaborations. And, local PHAs should identify the data-sharing and data-dissemination champions across sectors to help promote stakeholder engagement.

State and local health agencies should seek funding from the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Integration (CMMI) State Innovation Model (SIM) grants to create multisectoral public private partnerships for addressing community priorities in social determinants of health. Foundations (e.g., Betty and Gordon Moore Foundation, California Healthcare Foundation, The California Endowment, The Commonwealth Fund, deBeaumont Foundation, Gates Foundation, Kresge Foundation, The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, W. T. Kellogg Foundation) should fund convening activities that help participants learn the value of new partnerships; identify promising practices that can serve as PHI models; and assess the quality, usability and curation of data across different sectors for analysis.

Develop new, standards-based and interoperable data infrastructure that is accessible and meets the needs of community-based partners.

New standards for core community health data sets should be developed where needed, and community members should be involved in measures development. From the outset of collaborations, participants should plan for data sharing and develop mechanisms for collective interpretation of findings from different data sources. The Public Health Accreditation Board should create a new accreditation standard for a recommended list of well-defined, standard format data sets. Downloadable web-based queries should be made available (unless prohibited by law). This will help to establish consensus on standards for data and data sets to meet neighborhood needs.

Public health leadership organizations such as ASTHO, CSTE, JPHIT, and NACCHO, should collaborate to promote the use, adaption, and, when necessary, design and development of new open-source data aggregation tools and advanced analytics services to help understand data patterns. The public health practice and academic research communities should work together to identify the data sources they need to build evidence of the effectiveness of interventions. They should organize an effort to collect information across sectors, beginning with public sector agencies, and standardize data structures so data can be easily aggregated and reused for other purposes. Engaged organizations could include the American Public Health Association (APHA), Association of Schools and Programs of Public Health (ASSPH), Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (ASTHO), Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE), National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO), the Society for Epidemiological Research, and Trust for America’s Health.

PHI experts and data curators should develop best practices to combine clinical and individual data in HIPAA compliant ways, including the “omics” (epigenomics, metabolomics, “ZIPcodeomics,” etc.). Engaged organizations could include the American Medical Informatics Association (AMIA), Joint Public Health Informatics Taskforce (JPHIT), National Association of Public Health Information Technology (NAPHIT), and the Public Health Data Standards Consortium. Data curators could be identified through EDM Forum, the Health Data Consortium (HDC), and the California Healthcare Foundation Free the Data Initiative.

Make existing data more readily available to local partners, as a core responsibility of public health practice.

In 2010, HHS launched the Health Data Initiative (https://healthdata.gov/blog/health-data-initiative-strategy-execution-plan-released-and-ready-feedback) to encourage consumers, providers, local leaders, employers, researchers and others to discover innovative uses for public data. More than 1,000 data sets have been released since that time, but they vary in usability and often require information intermediaries to help access and interpret them.

PHAs should collaborate with academic and nonprofit organizations to create public use data sets and query-able websites that can be accessed by other stakeholders, such as other PHAs, provider organizations, insurers, academic institutions, community groups, and individuals. In the interim before these are available, data curators in PHAs should post clear instructions on how to formally request information in the context of a memorandum of understanding or data use agreement and toolkits for creating web-based queries should be developed.

Emerging leaders in the field of scalable analytic services should license open source analytics tools to stakeholders participating in collaborative data sharing and analysis for their use with their own data sources. Costs for the software infrastructure and architecture could be allocated across a consortium of members based on usage of infrastructure components and agreements for merging local datasets.

Industry (e.g., Google, IBM, Microsoft) and nonprofit partners (e.g., Community Commons, County Health Rankings and Roadmaps) should develop consumer-friendly data visualization approaches to help local PHAs and community members set and track progress toward local goals such as noncommunicable disease control efforts, health equity improvement, or increased community resilience.

Develop a prototype neighborhood health record to capture precise, timely, specific, and relevant measures of health and to track health risks and disparities at the community level.

Better information at the neighborhood level can provide neighborhood baselines and an opportunity for community leaders and members to monitor the impact of local initiatives and determine best practices. Neighborhood health records can be one way to stimulate initiatives targeting social determinants and to contribute to the development of an evidence base to monitor their impact.

The Community Preventive Services Task Force should coordinate with public health leaders to develop a framework for conceptualizing social determinants of health that will guide development of metrics for the neighborhood health record. Foundations should establish immediate formative investments to rapidly pilot test and evaluate different models of a neighborhood health record to determine effective approaches. Local PHAs and community partners should test and validate the neighborhood health record prototype in communities already engaged with local political leaders in community health enhancement efforts. And, neighborhood health record initiatives should initiate benchmarking (with appropriate confidentiality and security safeguards and validated reporting metrics) to provide the feedback that allows community-based programs to improve the effectiveness of their programs and embrace public reporting.27

Gather, curate, disseminate, and provide sustainable funding to maintain an evidence base of best practices in PHI.

There is no current library or repository of promising evidence-generating informatics practices, and new tools tend to be disseminated in limited and disparate venues. The Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (ASTHO), Council of State and Territorial

Epidemiologists (CSTE), NACCHO, and the Joint Public Health Informatics Taskforce should develop initiatives that do more to inform, disseminate, and support implementation of toolkits and resources for data integration, analysis, and visualization. All public health partners should promote the use of existing open source analytics tools. Current open data repositories, such as the EDM Forum 8 (www.edm-forum.org) should be expanded for the purpose of sharing information on what works in informatics.

The editorial policies for Methods sections of Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Review (MMWR) and other journals should be amended to require that informatics methods and aspects of the articles be clearly described, as a way to help increase awareness and knowledge of informatics principles, methods, and tools.

Promote innovative approaches to workforce development in PHI.

Training of the current workforce is essential to assure a national cadre of public health workers who are skilled in analytics and visualization of data, as well as skills to communicate the knowledge derived from those data. But there are substantial informatics workforce shortages and unmet needs now, and new people need to be recruited into the rapidly evolving field.

Federal partners should expand training opportunities such as the CDC Public Health Informatics and National Library of Medicine Informatics training programs. This should include significantly expanding a national informatics corps with common competencies available to large cities and states to assist with PHI data analysis, visualization, and communication. Public health schools and the Association of Schools and Programs of Public Health should require an introductory informatics class for all degree programs and should develop informatics certificate programs for the current workforce. State and local PHAs should train individuals who live in and are familiar with the community to work as community health data workers, creating a bridge between public health and hard-to-reach populations.

All partnering institutions should use “low cost” IT tools (such as cell phones, text messaging) to assure capacity for a broad variety of skill levels to participate in data reporting.

Summary and Next Steps

Through a creative scenarios-based process, workshop participants developed a set of recommendations aimed at guiding public health stakeholders toward an aspirational vision of expanded and multi-institutional analytic collaboration on near- and long-term determinants of health using informatics-based approaches. Six recommendations were identified and targeted toward state and local PHAs, federal public health partners, other government agencies, health care delivery organizations, health plans, private industry, and nonprofit organizations.

In this workshop, the use of four plausible future scenarios provided the participants with the ability to explore a range of impacts, choices, and decisions and enabled the identification of key leverage points for which actionable recommendations were targeted. Key points for public health transformation identified by our group included the following:

Serving as convener of partners and facilitator of data sharing. A need for the duties of PHAs to shift to achieve either of the aspirational and successful scenarios, in which PHAs would increasingly serve as the convener of partners and would facilitate the sharing of data from multiple sources. To serve as this trusted and neutral resource, PHAs will need to possess a strong base of informatics capacity and be willing to work with other agencies and organizations as full partners. This transformative role and set of competencies for public health were emphasized by the Institute of Medicine29 in its 2002 report on the future of the public’s health in the twenty-first century.

Promoting the value of PHI to advance evidence-based public health. Promoting awareness among public health leaders of the value of using PHI to advance evidence-based public health practice, especially in the context of new partnerships, is needed.

Increasing advocacy and communication on behalf of PHI. The importance of increased advocacy and strategic communications, and of expanding resources for that purpose, should be recognized.

These recommendations align with components identified by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as being necessary for effective public health program implementation. However, they place a stronger emphasis on PHAs embracing multi-institutional partnerships with mutual benefits and promoting the role of PHAs in providing informatics expertise to these partnerships. Efforts to develop the workforce and expand such partnerships should measure the value of investments in terms of both costs and population health outcome improvements. This will broaden the evidence base and promote further investments.

Scenario planning is often viewed as a valuable tool to help broaden stakeholder thinking regarding complex challenges, especially in the face of uncertainty. This process for articulating strategic recommendations has both limitations and strengths.30 Generally, scenarios that succeed in elucidating insights into key decisions to be made are those that are designed to be plausible, that challenge conventional wisdom about the future, and that are sufficiently differentiated from each other. The scenarios and approach used for this process meet these criteria.

Our group process of “stepping into” the scenarios, considering the implications and recommendations, comparing the scenario results, and focusing on key themes and recommendations, involved subjective aggregation and synthesis. Given that the scenarios already focus on and simplify future possibilities, and given the time limitations of the workshop, there is a risk of oversimplifying complex and dynamic situations. While the workshop participants brought deep understanding and knowledge of the field, another group of experts might have framed the issues in a different way.

Still, using scenarios has proven useful in transforming other sectors. We offer these recommendations in the hope that they will bring awareness and attention to some compelling issues facing the field and lead to new collaborations to help address them.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the multidisciplinary group of experts who participated at the two-day workshop in October 2013, hosted by the Public Health Informatics Institute (PHII) and Institute for Alternative Futures (IAF) to evaluate forces shaping public health informatics in the United States, with the aim of identifying upcoming challenges and opportunities.

Appendix A: Public Health Informatics 2023 Summaries and Comparative Matrix

The discussion of the future of public health informatics (PHI) and the development of the above recommendations used four scenarios to consider the range of likely, challenging and visionary possibilities. This Appendix presents summaries of the scenarios used in this project along with a matrix comparing key elements across the scenarios. A more complete version of the scenarios is available at www.phii.org.

Public Health Informatics 2023 Scenarios

Scenario 1: Information for Health Action

“Zone of Conventional Expectation”

Over the years up to 2023, constrained economic circumstances— in conjunction with health departments’ role in prevention and supporting national security—drive up the demand for a more strategic public health. While PHAs (both state- and local health departments) continue to do “what others cannot or will not do” to enhance the opportunities for all to be healthy, most shift away from the delivery of clinical health care services and enhance their assessment, protection, and prevention efforts. Yet challenges with funding, resources, data quality, and actionable analytics in the face of rising chronic disease and climate change have an impact on the full promise of public health and PHI. By 2023, the aggregate health of the nation has improved only marginally.

Scenario 2: Write-Only Misinformatics

“Zone of Growing Desperation”

In 2023, informatics in public health is in a dire state. Severe economic decline has led to drastic cuts in federal, state, and local funding for public health and PHI. The Second Great Depression has hindered the nation from implementing crucial elements of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, including effective uptake and use of EHRs and other health IT. Many PHAs (which include both state- and local health departments), have failed to keep up with advances in information systems, and still use outdated methods of collecting and analyzing data that do not meet demands for real-time information. An internal culture of ownership over data (the adage that data is spelled “TURF”) prevents many PHAs from sharing data externally and internally. This prevents PHAs from partnering with the private sector, which has more advanced informatics capacities and greater collections of health data. Many local health departments (LHDs) and some state health departments have been unable to expand or obtain the necessary informatics skill set shifts within their workforce. By 2023, many PHAs have become largely irrelevant when it comes to population health information, due to public distrust, restrictions in cloud computing services, a fast-shrinking workforce of public health informaticians, silos within PHAs, lack of funding, and lack of interoperability among surveillance and other information systems.

Scenario 3: Pearl Harbor for Public Health

“Zone of High Aspiration”

Public health and PHI quickly evolved into a federated enterprise over the decade thanks to a series of crises that public health helped prepare for and respond to. The “Pearl Harbor for Public Health,” a pandemic that got wildly out of control, set up public health to lead more effectively in future pandemics. Beyond the emergencies, as the availability of personal biomonitoring, medical, environmental risk, and population health information grew exponentially, public health continued to evolve away from providing personal health care services to having a major role in the aggregation and analysis of population health data and setting health policy. As more information was routinely gathered and analyzed by health care providers, citizen science groups, and marketing companies, PHAs (which include both state- and local health departments) provided advice on analysis and provided leadership in collaboratively addressing the social determinants of health.

Scenario 4: Everybody Is an Informatician

“Zone of High Aspiration”

In 2023, public health focuses on prevention of unhealthy conditions and creation of optimal health conditions, ranging across factors such as the social determinants of health, genomics, epigenetics, disease, predisease, nutrition, health care, behavior, and the ever-changing built and natural environments. PHAs (both state- and local health departments), and public health informaticians have proven almost too effective for their own good. Health care reform proved highly successful, as the United States economy gradually recovered from the recession period of the mid- and late 2010s. However, budget deficits required financial accountability and cost-effectiveness. While ACOs sought to reduce costs and improve outcomes of health care throughout the 2010s, PHAs in the late 2010s were required to implement an evidence- and experience-based minimum package of services and capabilities that included advocacy, partnership formation, and communication. To this end, PHAs worked with various community organizations and agencies to help people understand, access, and use the information that was gathered by individuals, citizen science, private organizations, and governmental groups. In 2023, PHI is no longer just within the realm of health departments. Accreditation standards require that PHAs demonstrate significant capacity in informatics and that they have informatics plans based on a national set of standards, yet private actors, consumers, and even schoolchildren have begun to use public health information to improve health. Public health information use has become a widespread societal capacity and is enabling some communities to pursue the revolutionary concept of “universal public health.”

Table A1.

Scenario Matrix: A Side-by-Side Comparison of the Scenarios across Multiple Dimensions

| Scenario Dimensions | Scenario 1: Information for Health Action | Scenario 2: Write-Only Misinformatics | Scenario 3: Pearl Harbor for Public Health | Scenario 4: Everybody Is an Informatician |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economy & fiscal conditions | Slow economic recovery, mild recession in late 2010s | Severe economic decline, “Second Great Depression” | Steady economic growth; slowed by first pandemic, followed by recovery | Gradual economic recovery |

| Infections & environmental challenges | New and reemerging disease, more extreme weather events | Recurring disease outbreaks, including an avian flu epidemic and extreme weather events | Two pandemics, along with other disease outbreaks and extreme weather events | Increasing frequency of climate-related events and disease outbreaks |

| Public Health and Health Care | ||||

| Role of health care in improving population health | Provide referrals and funding to community organizations for population health activities | Community health centers and some large health systems work on population health, but few work with public health agencies (PHAs) | Largest health care providers and Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) integrate data and fund PHAs for population health activities | Largest health care providers and ACOs integrate data to and fund PHAs for population health activities |

| Competitors for public health informatics (PHI) functions | Health care provider organizations and the private sector do big data analytics (for PHAs, and in competition with them) Inspections are automated, with results reported to PHAs and local consumer ratings groups |

Citizen science groups and private companies take over some surveillance, monitoring, data collection, and big data analysis with varying degrees of effectiveness | The federated public health enterprise leads in PHI functions but collaborates with private sector for community mapping and advanced analytics Inspections are automated, with results reported to PHAs and local consumer ratings groups |

Automation and the private sector take over many tasks in assessment, analytics, inspection, and regulation Health department surveillance and reporting sometimes replaced by self-surveillance, commercial surveillance, and citizen-science and individual self-reporting |

| Public Health Informatics (PHI) | ||||

| Electronic Health Records (EHRs) | Widespread use of EHRs Vary in access, and interoperability for PHA use Generally focus on clinical history; with incomplete ability for PHAs to identify syndemic patterns among diseases & risk factors |

EHRs are in use in most health care systems, but vary in access and ease of use; limited interoperability standards Generally focus on clinical history; with incomplete ability for PHAs to identify syndemic patterns among diseases & risk factors |

Nearly universal uptake of EHRs Highly interoperable, easy for PHAs to access and use Include personal health and health care history, medical conclusions, biomonitoring, and SDH-related history; allow syndemic pattern analysis |

Nearly universal uptake of EHRs Highly interoperable, easy for PHAs to access and use Include personal health and health care history, medical conclusions, biomonitoring, and SDH-related history; allow syndemic pattern analysis |

| Big data analytics | Provision of increasingly personalized recommendations that take into account state and local public health and SDH | PHAs cannot analyze much of the data; when they can, it is done in a siloed manner Data sharing fragmentation across jurisdictions continues |

PHAs access information from a wider array of sources “Doc Watson for Public Health” expert systems and other tools |

PHAs track, evaluate, and compare prevention methods Health departments provide “community health dashboards” |

| Evidence of public health interventions | Public health recognized as essential to national security, and able to effectively reduce prevalence of chronic diseases | Poor informatics capabilities, and mishandling of data; evidence available only among better-off communities | Public health seen as cost-effective in aiding populations to combat health and environmental threats and to contribute to economic growth | PHAs use their capabilities and expertise to successfully improve and coordinate local prevention and emergency response efforts |

| The goals or benefits of PHI—what outcomes, contributions, or value has PHI provided by 2023 | Enable robust population health assessments Help overcome traditional barriers to moving health and health care data across organizational and jurisdictional borders |

Collect and monitor regulatory data | Help establish national and regional public health networked enterprises Improve emergency response to pandemics |

Offer tracking, evaluation, and comparison of prevention efforts to improve behavior, emergency response, and address the social determinants of health Help communities move towards “universal public health” |

| Health outcomes | Communicable disease rates begin to decrease significantly in several regions, but disparities continue; chronic disease continues to increase, particularly in low income populations | Communicable diseases rise, including avian and other flu outbreaks; chronic disease increases; health disparities increase significantly | Noticeably improved outcomes, especially for preventable conditions; disparities are narrowing for some health indicators | Improvements in several indicators; disparities decrease |

| Mutual assistance agreements | Most PHAs share some type of services through “mutual assistance” agreements | Limited mutual assistance agreements for pooling resources and services | Highly effective agreements in place regarding public health labs for disaster response and community health | Highly effective agreements regarding public health labs as part of sustainability plans |

| Public perceptions of PHAs | Have greater public awareness and some trust for handling personal data; recognized for their roles in national security and emergency preparedness | Are less visible to the public, and thought of as ineffective and undeserving of funding; some state and local departments are not trusted to hold or analyze personal health records | Are highly respected; trusted for holding personal data and doing secondary analysis; everyone knows what public health practitioners do | Are respected for coordinating prevention efforts and emergency preparedness; trusted with data; and praised for their efforts at empowering personal analysis |

| Public health informaticians | Increasing demand, often hired away from PHAs for higher salaries Receive training from private entities and the public sector Collaborate across the public and private sectors to prevent disease, reduce costs, and optimize data use |

Workforce in PHAs downsized; some informatics specialists remain, but there are better opportunities elsewhere, outside the PHA | High demand for public health informaticians Are readily employed and have completed excellent training programs Collaborate across the public and private sectors to address population health |

No longer a distinct workforce, informatics widely taken up by other public health professionals and general public Informatics training integrated into other disciplines Citizens trained in basic informatics, consult about techniques or questions, or work with private entities |

Footnotes

Disciplines

Health Information Technology | Health Services Research

Expert Committee Members

Karen Bell, MD, MMS

Chair

Certification Commission for Health Information Technology

Teresa Cutts, PhD

Professor, Division of Public Health Sciences

Wake Forest University

Margo Edmunds, PhD

Vice President, Evidence Generation and Translation

AcademyHealth

Dave Fleming, MD

Director and Health Officer

Seattle & King County Health Department

Dennis Israelski, MD

Clinical Professor of Medicine (Affiliate)

Division of Infectious Diseases and Geographic Medicine, Stanford University

Marty LaVenture, MPH, PhD

Director, Office of Health Information Technology

Director, Center for Health Informatics and e-Health

Minnesota Department of Health

Office of Health Information Technology

John Mattison, MD

Assistant Medical Director, Chief Medical Information Officer

Kaiser Permanente, Southern California

Martin Sepulveda, MD

Vice President of Integrated Health Services

IBM T.J. Watson Research Center

Lorna Thorpe, MPH, PhD

Professor and Program Director, Epidemiology and Biostatistics (EPI)

CUNY School of Public Health, Hunter College

Institute for Alternative Futures Staff

Clem Bezold, PhD

Founder and Chairman

Trevor Thompson

Futurist

Public Health Informatics Institute Staff

David A. Ross, ScD

Director

Ellen Wild, MPH

Deputy Director

Bill Brand, MPH

Director, Public Health Informatics Science

Anita Renahan-White, MDiv, MPH

Sr. Informatics Analyst

Debra Bara, MA

Director, Practice Support

Vivian Singletary, MBA

Director, Requirements Laboratory

Jessica Cook

Communications Manager

Terry Marie Hastings, MA

Communications Consultant

References

- 1.Hersh WR. A Stimulus to Define Informatics and Health Information Technology. BMC Medical Informatics Decision Making. 2009:9–24. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-9-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Savel TG, Foldy S. The Role of Public Health Informatics in Enhancing Public Health Surveillance. MMWR. 2012 Jul;61(03):20–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute of Medicine. The Future of Public Health. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dixon BE, Grannis SJ. In: Public Health Informatics and Information Systems. Magnuson JA, Fu PC Jr, editors. London: Springer-Verlag; 2014. pp. 69–88. Chapter 5, Public health informatics infrastructure. [Google Scholar]

- 5.The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Using public health information in the e-Health Decade: articulating strategies for public health informatics. Summary, Program Results Brief [Internet]. [cited 2014 July 5]. Available from: http://www.rwjf.org/en/research-publications/find-rwjf-research/2014/06/using-public-health-information-in-the-e-health-decade.html.

- 6.Institute of Medicine. The Future of the Public’s Health In The 21st Century. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kindig DA. What Is The Difference Between Population Health And Public Health? [Internet]. Available from: http://www.improvingpopulationhealth.org/blog/what-is-the-difference-between-population-health-and-public-health.html.

- 8.Magnuson JA, O’Carroll PW. In: Public Health Informatics and Information Systems. Magnuson JA, Fu PC Jr, editors. London: Springer-Verlag; 2014. pp. 47–66. Introduction to public health informatics. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The Triple Aim: Care, Health, and Cost. Health Affairs. 2008;27(3):759–69. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Institute of Medicine. The Future of the Public’s Health In The 21st Century. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Magnuson JA, O’Carroll PW. Chapter 1, Introduction to Public Health Informatics. In: Magnuson JA, Fu PC Jr, editors. Public Health Informatics and Information Systems. 2nd Edition. London: Springer-Verlag; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Health Care and Social Services Market 2012–2017. GovWin-IQ from Deltek. 2012. http://iq.govwin.com/corp/downloads/Deltek-IR-HC-SS-2012-SUMMARY.pdf.

- 13.Perna G. Healthcare Informatics. Report: Health IT Spending to Exceed $69 billion over six-year period. June 22, 2012. http://www.healthcare-informatics.com/news-item/report-health-it-spending-exceed-69-billion-over-six-year-period.

- 14.Edmunds M. Chapter 4, Governmental and Legislative Context of Informatics. In: Magnuson JA, Fu PC Jr, editors. Public Health Informatics and Information Systems. 2nd Edition. London: Springer-Verlag; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Forum EDM. Informatics Tools and Approaches To Facilitate the Use of Electronic Data for CER, PCOR, and QI: Resources Developed by the PROSPECT, DRN, and Enhanced Registry Projects [Internet] 2013. Issue Briefs and Reports. Paper 11. Available from: http://repository.academyhealth.org/edm_briefs/11.

- 16.McCarthy DB, Propp K, Cohen A, Sabharwal R, Schachter AA, Rein AL. Learning from Health Information Exchange Technical Architecture and Implementation in Seven Beacon Communities. eGEMs. 2014;2(1):6. doi: 10.13063/2327-9214.1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Friedman C. What informatics is and isn’t. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2013;20(2):224–6. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2012-001206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Drebohl PA, Roush SW, Stover BH, Koo D. Public health surveillance workforce of the future. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2012 Jul 27;61(03):25–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Association of County & City Health Officials. Local Health Department Job Losses and Program Cuts: Findings from the 2013 Profile Study. [Internet]. [cited 2014 Aug 12]. Available from http://www.naccho.org/topics/infrastructure/lhdbudget/upload/Survey-Findings-Brief-8-13-13-3.pdf.

- 20.Drebohl PA, Roush SW, Stover BH, Koo D. Public health surveillance workforce of the future. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2012 Jul 27;61(03):25–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Erickson D, Andrews N. Partnerships Among Community Development, Public Health, and Health Care Could Improve the Well-being of Low-income People. Health Affairs. 2011;30(11):2056–63. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCarthy DB, Propp K, Cohen A, Sabharwal R, Schachter AA, Rein AL. Learning from Health Information Exchange Technical Architecture and Implementation in Seven Beacon Communities. eGEMs. 2014;2(1):6. doi: 10.13063/2327-9214.1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Allen C, DesJardins TR, Heider A, Lyman A, McWilliams L, et al. Data Governance and Data Sharing Agreements for Community-Wide Health Information Exchange: Lessons from the Beacon Communities. [Internet]. [cited 2014 Aug 3]. Available from: http://repository.academyhealth.org/egems/vol2/iss1/5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Brownson RC, Fielding JE, Maylahn CM. Evidence-based public health: a fundamental concept for public health practice. Annual Review of Public Health. 2009;30:175–201. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.031308.100134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Institute of Medicine. The Learning Health System Series. [Internet]. [cited 2014 July 12]. Available from: http://iom.edu/∼/media/Files/Activity%20Files/Quality/VSRT/Core%20Documents/LearningHealthSystem.pdf.

- 26.Rubin JC, Friedman CP. Weaving together a health improvement tapestry: Learning health system brings together Health IT data stakeholders to share knowledge and improve health [Internet] [cited 2014 July 11]. Available from: http://library.ahima.org/xpedio/groups/public/documents/ahima/bok1_050661.hcsp?dDocName=bok1_050661. [PubMed]

- 27.Heider Arvela R, Maloney Nancy, Satchidanand Nikhil, Allen Geoff, Mueller Raymond, Gangloff Steven, Singh Ranjit. “Developing a Community-Wide Electronic Health Record Disease Registry in Primary Care Practices: Lessons Learned from the Western New York Beacon Community,”. eGEMs (Generating Evidence & Methods to improve patient outcomes) 2014;2(3) doi: 10.13063/2327-9214.1089. Article 7. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.13063/2327-9214.1089 Available at: http://repository.academyhealth.org/egems/vol2/iss3/7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Forum EDM. Informatics Tools and Approaches To Facilitate the Use of Electronic Data for CER, PCOR, and QI: Resources Developed by the PROSPECT, DRN, and Enhanced Registry Projects [Internet] 2013. Issue Briefs and Reports. Paper 11. Available from: http://repository.academyhealth.org/edm_briefs/11.

- 29.Institute of Medicine. For the public’s health: the role of measurement in action and accountability. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mietzner D, Reger G. Advantages and disadvantages of scenario approaches for strategic foresight. International Journal of Technology Intelligence and Planning. 2005;1(2):220–39. [Google Scholar]